Abstract

Background & Aims

Fulminant hepatitis (FH) is a clinical syndrome characterized by sudden and severe liver dysfunction. Dot1L, a histone methyltransferase, is implicated in various physiologic and pathologic processes, including transcription regulation and leukemia. However, the role of Dot1L in regulating inflammatory responses during FH remains elusive.

Methods

Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes)-primed, lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-induced FH was established in C57BL/6 mice and was treated with the Dot1L inhibitor EPZ-5676. Myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) were depleted by anti-Gr-1 antibody to evaluate their therapeutic roles in Dot1L treatment of FH. Moreover, peripheral blood of patients suffered with FH and healthy controls was collected to determine the expression profile of Dot1L-SOCS1-iNOS axis in their MDSCs.

Results

Here we identified that EPZ-5676, pharmacological inhibitor of Dot1L, attenuated the liver injury of mice subjected to FH. Dot1L inhibition led to decreased T helper 1 cell response and expansion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) during FH. Interestingly, Dot1L inhibition didn’t directly target T cells, but dramatically enhanced the immunosuppressive function of MDSCs. Mechanistically, Dot1L inhibition epigenetically suppressed SOCS1 expression, thus inducing inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression in a STAT1-dependent manner. Moreover, in human samples, the levels of Dot1L and SOCS1 expression were upregulated in MDSCs, accompanied by decreased expression of iNOS in patients with FH, compared with healthy controls.

Conclusions

Altogether, our findings established Dot1L as a critical regulator of MDSC immunosuppressive function for the first time, and highlighted the therapeutic potential of Dot1L inhibitor for FH treatment.

Keywords: Fulminant Hepatitis, Histone Methyltransferase Dot1L, Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase, Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells

Abbreviations used in this paper: BM, bone marrow; CFSE, carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; COX2, cyclooxygenase-2; Dot1L, disruptor of telomeric silencing-1-like; DC, dendritic cell; FH, fulminant hepatitis; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; H3K79, histone 3 lysine 79; HBV, hepatitis B virus; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressive cell; MNC, mononuclear cell; NO, nitric oxide; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SOCS1, suppressor of cytokine signaling 1; STAT1, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1; Th1, T helper 1; Treg, regulatory T cell; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β

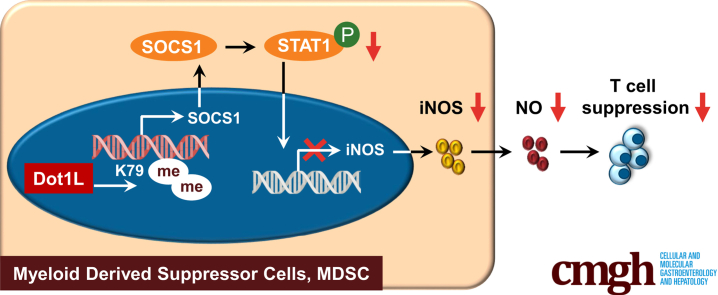

Graphical abstract

Summary.

EPZ-5676, inhibitor of Dot1L, is a potential strategy for fulminant hepatitis treatment. Dot1L inhibition dramatically enhanced the immunosuppressive function of myeloid derived suppressor cells. Mechanistically, Dot1L inhibition epigenetically suppressed SOCS1 expression, inducing inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in a STAT1-dependent manner.

Fulminate hepatitis (FH), characterized by severe hepatocellular dysfunction followed by hepatic coagulopathy or encephalopathy, is a potentially fatal clinical syndrome, which develops secondary to infection, side effects of drugs, toxins, alcohol abuse, or metabolic syndrome.1,2 The mechanisms leading to such profound hepatic damage are not fully understood, but circumstantial evidence suggests that poorly controlled inflammatory responses play a major role in the pathogenesis of FH. Abundant immune cells infiltrate into the liver and produce a large number of pro-inflammatory cytokines thus inducing apoptosis and necrosis of hepatocytes.3,4 Although many pharmacological approaches have been proposed to recover liver function, liver transplantation is still the current gold standard of care. However, use of liver transplantation is limited by transplantation-related problems, such as lack of donors, risk of rejection, and side effects of immunosuppressive drugs.5

Liver immune homeostasis is controlled by epigenetic histone modifications including histone methylation and acetylation.6 Aberrant histone modifications comprise an important mechanism in pathogenesis of liver diseases.7,8 Thus, interfering with the function of histone regulators may be a beneficial approach to the development of novel therapeutic strategies. Disruptor of telomeric silencing-1-like (Dot1L), a major histone methyltransferase, catalyzes mono-, di-, and trimethylation on histone 3 lysine 79 (H3K79), which is often associated with gene transcriptional activation.9 Dot1L has several known functions in immunity. First, Dot1L is required for the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells and lineage-specific progenitors in homeostatic conditions.10 Second, as a highly conservative protein in different species, Dot1L is widely expressed in various kinds of immune cells of mice and humans.11 Third, both innate and adaptive immune responses are modulated by Dot1L via promoting interleukin (IL)-6 and interferon (IFN)-β expression from macrophages,12 regulating low-avidity T cell responses and controlling the activation threshold in human T cells.13 However, the roles of Dot1L and H3K79 methylation mediated by Dot1L in the pathogenesis of FH and the underlying immunoregulatory mechanism remain elusive.

Tolerogenic regulators play important roles in maintaining immune tolerance in liver and restraining inflammation-induced liver injury. One of the main regulators is myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), a heterogeneous population of myeloid cells derived from bone marrow (BM), which exert immunosuppressive effects on both innate and adaptive immune responses to foster immune tolerance.14 MDSCs have been implicated to link with T cell dysfunction in chronically hepatitis B virus (HBV) infected patients.15 In mouse models of liver injury, MDSCs also exhibited immunosuppressive function through impairing proliferation and proinflammatory cytokine secretion of liver-infiltrating T cells, thus protecting against hepatic inflammation and hepatocyte dysfunction.16, 17, 18 Recently, several groups reported that histone methylation might regulate the generation of MDSCs from hematopoietic progenitor cells.19,20 However, whether Dot1L is effective in regulating the immunosuppressive function of MDSCs and the underlying mechanism is still poorly understood.

In this study, using Propionibacterium acnes–primed, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced FH in mice, we found that interference with Dot1L activity using pharmacological inhibitor attenuated the severity of liver injury and mortality of FH in mice. The protective role of Dot1L inhibition was attributed to increased inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression of MDSCs, which inhibited T helper 1 (Th1) cell response and induced regulatory T cell (Treg) expansion. The molecular and genetic evidence further demonstrated that Dot1L served as a positive regulator of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1), which in turn inhibited the signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) signaling pathway and restrained the expression of iNOS in MDSCs. Therefore, our study suggests Dot1L as a potential therapeutic target for acute liver injury and associated diseases.

Results

Inhibition of Dot1L Alleviates Mouse Mortality and Severity of P. acnes–Induced Liver Injury

To determine the role of Dot1L during FH pathogenesis, EPZ-5676, an inhibitor of Dot1L, or vehicle was injected intraperitoneally after P. acnes priming. For the vehicle-treated group, all mice died within 20 hours after LPS injection. In contrast, EPZ-5676–treated mice significantly improved the survival rate of FH, and all mice survived more than 48 hours (Figure 1A).

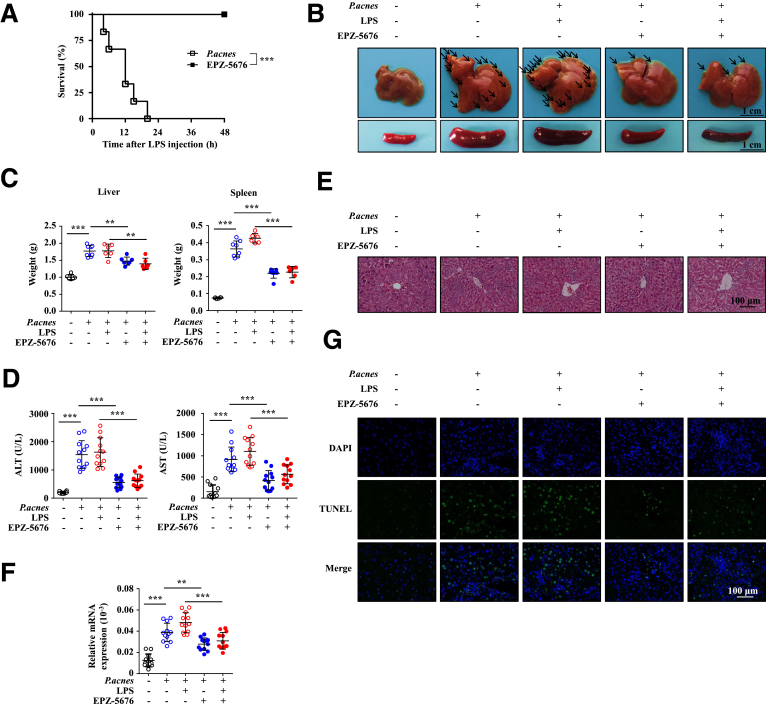

Figure 1.

Inhibition of Dot1L alleviates mouse mortality and severity of P. acnes–induced liver injury. Mice were injected with P. acnes suspended in 200 μL of PBS. Vehicle or EPZ–5676 (35 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally on days 0, 2, 4, and 6, then 1 μg of LPS in 100 μL of PBS was injected on day 7 to induce FH. (A) Cumulative survival rates of mice were analyzed (n = 6–8 mice per group). (B, C) Livers and spleens were isolated and photographed. (B) Representative images from 1 experiment were shown. (C) Weight of livers and spleens from 6 to 8 mice per group was measured. (D) Serum from naïve, vehicle-treated, or EPZ-5676–treated mice was collected on day 7 after P. acnes priming. Serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured (n = 12 mice per group). (E) Liver tissues were sectioned for histological examination. (F) messenger RNA (mRNA) level of Fas ligand in livers was measured (n = 12 mice per group). (G) Frozen sections of livers were used for TUNEL staining. Results are representative of 3–5 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. Significant differences were analyzed by (A) log-rank test, (C, D, F) 1-way analysis of variance, and expressed as ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

Liver injury of this model occurs in 2 phases: the early priming and the late elicitation phases. During the priming phase, P. acnes injection resulted in granuloma formation, whereas massive hepatocellular damage induced by LPS injection occurred during the elicitation phase.21 We found that the EPZ-5676–treated mice had markedly reduced granulomas in liver and significantly reduced weight of liver and spleen, compared with control mice, whether injected with LPS or not after P. acnes priming (Figure 1B and C). Consistently, there were dramatic reduction of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, which are hallmarks of hepatitis-induced liver failure, in the serum of EPZ-5676–treated mice (Figure 1D). In addition, histological analysis showed that livers isolated from mice treated with EPZ-5676 displayed smaller nodules and much less infiltration of lymphocytes (Figure 1E). We also found that administration of EPZ-5676 could significantly reduce the Fas ligand expression (Figure 1F) and the level of TUNEL+ (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling positive) cells (Figure 1G), indicating a lower level of hepatocyte apoptosis in liver. Taken together, these data collectively suggested that EPZ-5676 treatment effectively attenuated the severity of bacteria-induced liver injury and improved the survival rate of FH.

Dot1L Inhibition Reduces Activation and Proliferation of CD4+ T Cells

It is known that CD4+ T cell–mediated inflammation plays an important role in P. acnes–induced liver injury.21, 22, 23 Mononuclear cells (MNCs) accumulated significantly in the liver and spleen of P. acnes-primed control mice (Figure 2A), and both the percentage and absolute number of CD4+ T cells increased dramatically in the liver and spleen (Figure 2B and C). By contrast, infiltration of MNCs and CD4+ T cells decreased significantly both in the liver and spleen of EPZ-5676–treated mice (Figure 2A–C). To detect the proliferation of CD4+ T cells, we injected BrdU (5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine), a synthetic nucleoside that could be incorporated into newly synthesized DNA to monitor the cell proliferation, into EPZ-5676–treated or P. acnes-primed control mice. The flow cytometric analysis revealed that EPZ-5676 treatment decreased the frequencies of BrdU+ CD4+ T cells in the liver and spleen after P. acnes priming (Figure 2D), suggesting that Dot1L inhibition may regulate the proliferation of CD4+ T cells in vivo. In addition, EPZ-5676–treated mice showed decreased CD44hiCD62Llo CD4+ T cells, and increased CD62LhiCD44lo CD4+ T cells (Figure 2E), suggesting that Dot1L inhibition suppressed CD4+ T cell activation in vivo. We also found reduced expression of chemokine receptors, such as CXCR3 and CCR7 on CD4+ T cells (Figure 3A and B) and their respective chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CCL21 in the liver of EPZ-5676–treated mice (Figure 3C). These results indicated that Dot1L inhibition also suppressed the chemotaxis of pathogenic CD4+ T cells into the liver.

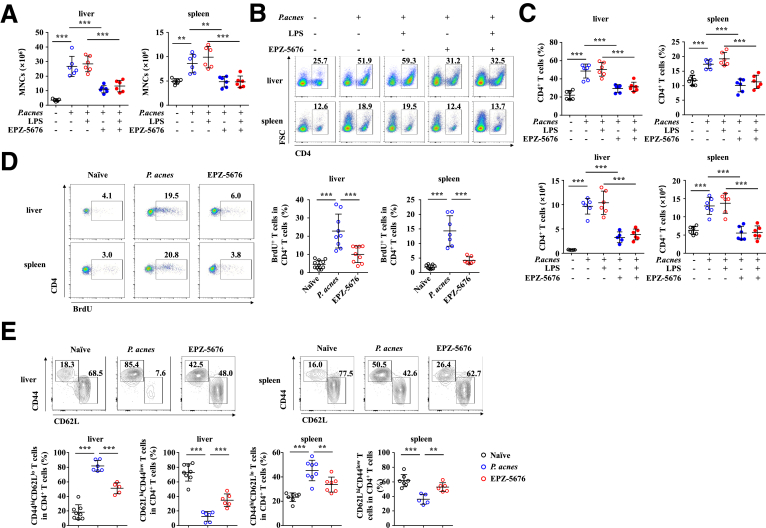

Figure 2.

Dot1L inhibition reduces activation and proliferation of CD4+ T cells. Mice were injected with P. acnes. Vehicle or EPZ-5676 (35 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 after P. acnes injection. The splenic or hepatic MNCs were isolated at day 7 after P. acnes priming. (A) Absolute numbers of total MNCs and (B, C) percentages and absolute numbers of CD4+ T cells in these tissues were determined by flow cytometry (n = 6 mice per group). (D) Frequencies of proliferating BrdU+ CD4+ T cells in livers and spleens were analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 7–9 mice per group). (E) Frequencies of CD44hiCD62Llo CD4+ T cells and CD62LhiCD44lo CD4+ T cells in livers and spleens were analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 5–8 mice per group). Results are representative of 3–5 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. Significant differences were analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance, and expressed as ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

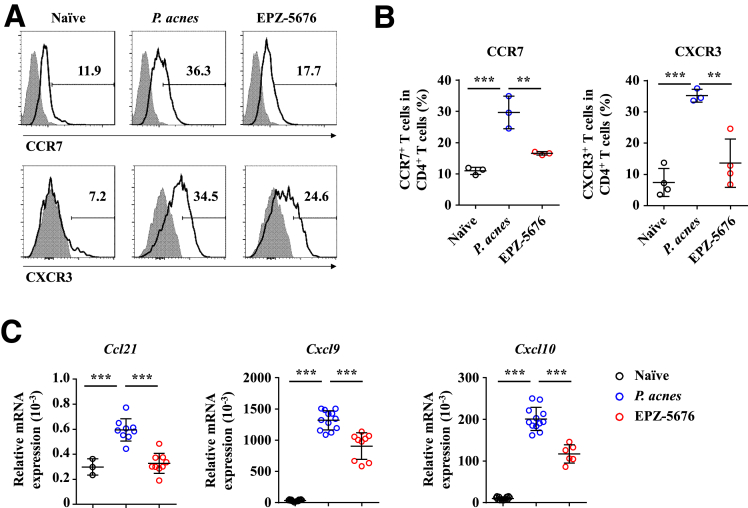

Figure 3.

Dot1L inhibition reduces migration of CD4+ T cells in the liver. Mice were injected with P. acnes. Vehicle or EPZ-5676 (35 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 after P. acnes injection. The splenic or hepatic MNCs were isolated at day 7 after P. acnes priming. (A, B) Levels of CXCR3 and CCR7 on CD4+ T cells derived from livers were analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 3–5 mice per group). (C) mRNA levels of chemokines in livers were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. Significant differences were analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance, and expressed as: ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

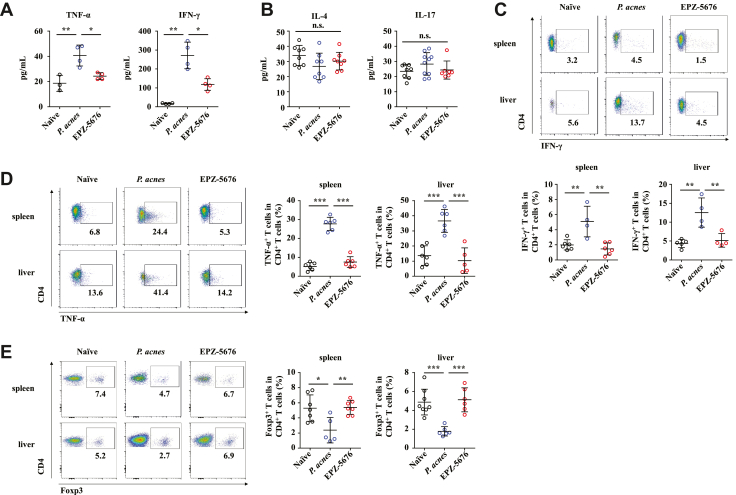

Dot1L Inhibition Suppresses Th1 Cells While Promotes Tregs in the Liver But Not in In Vitro Culture

We previously identified Th1 cells as major pathogenic contributor of P. acnes–induced liver injury.24 Thus, serum levels of Th1 cytokines IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), Th2 cytokine IL-4, and Th17 cytokine IL-17 were determined. EPZ-5676 treatment reduced levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ significantly (Figure 4A) but had no effect on IL-4 or IL-17 production (Figure 4B). Intracellular staining of IFN-γ and TNF-α further confirmed the reduction of IFN-γ– (Figure 4C) and TNF-α–positive cells (Figure 4D) after EPZ-5676 treatment within CD4+ T cells. By contrast, administration of EPZ-5676 significantly increased CD4+ Foxp3+ Tregs as compared with the vehicle treatment (Figure 4E). These data demonstrated that Dot1L inhibition suppressed Th1 cells but promoted Tregs in the liver.

Figure 4.

Dot1L inhibition suppresses Th1 cells while promotes Tregs in the liver. Mice were injected with P. acnes. Vehicle or EPZ-5676 (35 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 after P. acnes injection. The peripheral blood, livers or spleens were isolated at day 7 after P. acnes priming. (A, B) Levels of serum IFN-γ, TNF-α (n = 3–4 mice per group), IL-4, and IL-17 (n = 8 mice per group) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Inflammatory cytokines (C) IFN-γ and (D) TNF-α production was assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry (n = 4–6 mice per group). (E) Percentages of Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 5–8 mice per group). Results are representative of 3–5 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. Significant differences were analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance, and expressed as ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, n.s., not significant.

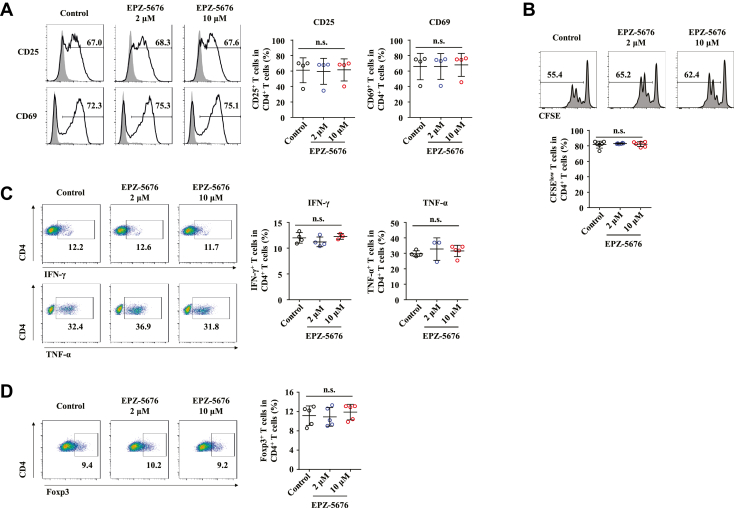

To further explore whether EPZ-5676 treatment impaired CD4+ T cell response during FH pathogenesis through a direct or indirect way. We tested the effect of EPZ-5676 on CD4+ T cells in in vitro culture. However, Dot1L inhibition was dispensable for the in vitro CD4+ T cell activation, proliferation and production of Th1 cytokines, as characterized by comparable CD25 and CD69 expression (Figure 5A), proliferation rate (Figure 5B), IFN-γ, and TNF-α production (Figure 5C) of EPZ-5676 or vehicle-treated T cells upon the stimulation of anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies. Moreover, percentage of CD4+ Foxp3+ Tregs were also comparable between EPZ-5676 and vehicle-treated T cells (Figure 5D). Collectively, these results suggested that Dot1L inhibition restricted the CD4+ T cell response through an indirect mechanism during FH pathogenesis.

Figure 5.

CD4+ T cell response is not inhibited by Dot1L inhibition in vitro. CD4+ T cells from the spleens and lymph nodes of C57BL/6 mice labeled with CFSE were cultured in the presence of plate-coated anti-CD3 antibody (5 μg/mL) and soluble anti-CD28 antibody (2 μg/mL) and treated with DMSO (control) or EPZ-5676 (2 μM or 10 μM). (A) Levels of CD25 and CD69 on CD4+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry at day 1. Gray shading and solid line indicate immunofluorescence intensity of cells for the control and test antibodies, respectively. (B) Frequencies of the proliferating (CFSE–) CD4+ T cells were measured by flow cytometry at day 3. (C) Inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α production was assessed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry at day 5. (D) Percentages of Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry at day 5. Results are representative of 3–5 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. Significant differences were analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance. n.s., not significant.

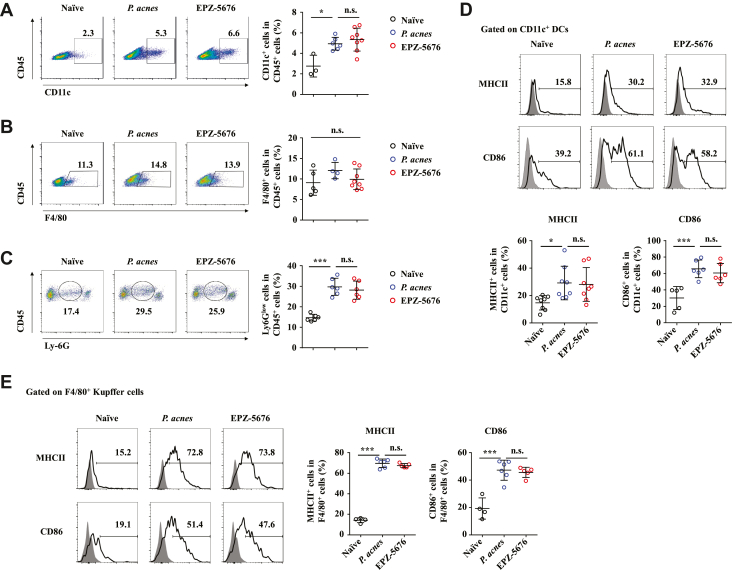

Inhibition of Dot1L Increases Immune Suppressive Ability of MDSCs

To figure out which type of cells in vivo were directly targeted by EPZ-5676 to protect against FH-induced liver failure, we examined the infiltration status of non–T cells in the liver and spleen. The results revealed EPZ-5676 treatment and P. acnes–primed control mice had similar frequencies of CD11c+ dendritic cells (DCs) (Figure 6A), F4/80+ Kupffer cells (Figure 6B), and neutrophils (Figure 6C) in the liver. Next, we investigated whether EPZ-5676 treatment could influence the activation and function of DCs and Kupffer cells. EPZ-5676 treatment did not affect the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II and costimulatory molecules CD86 in both CD11c+ DCs (Figure 6D) and F4/80+ Kupffer cells (Figure 6E). These data demonstrated that EPZ-5676 did not affect infiltration and activation of DCs, Kupffer cells, and neutrophils during FH pathogenesis.

Figure 6.

Accumulation and activation of DCs, Kupffer cells and neutrophils in liver are not affected by Dot1L inhibition. Mice were injected with P. acnes. Vehicle or EPZ-5676 (35 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 after P. acnes injection. The splenic or hepatic MNCs were isolated at day 7 after P. acnes priming. (A–C) Frequencies of (A) CD11c+, (B) F4/80+, and (C) Ly-6Glow cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 3–8 mice per group). (D, E) Levels of major histocompatibility complex class II and CD86 on CD11c+ DCs (n = 8 mice per group) or F4/80+ Kupffer cells (n = 4–6 mice per group) of livers were analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are representative of 3–5 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. Significant differences were analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance, and expressed as ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001. n.s., not significant.

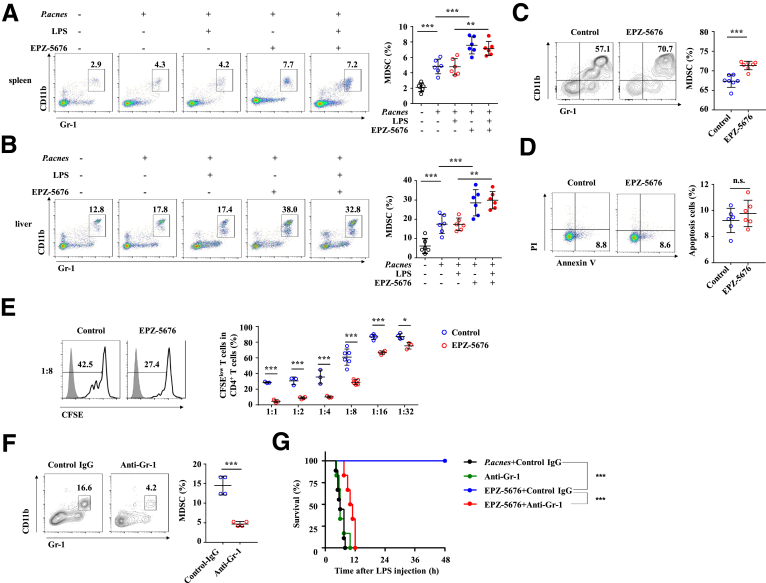

However, EPZ-5676 treatment notably increased the frequencies of CD11b+ Gr-1+ MDSCs in the spleen (Figure 7A) and liver (Figure 7B) at day 7, whether injected with LPS or not after P. acnes priming. Notably, 5 μM EPZ-5676 significantly enhanced the induction of MDSCs from BM cells (Figure 7C), without apparently affecting their apoptosis (Figure 7D). In addition, in vitro proliferation assay revealed that EPZ-5676–pretreated MDSCs exhibited enhanced ability to suppress T cell proliferation compared with control MDSCs, after co-cultured with CD4+ T cells that stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies (Figure 7E).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of Dot1L increases immune suppressive ability of MDSCs. Mice were injected with P. acnes. Vehicle or EPZ-5676 (35 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 after P. acnes injection. Frequencies of Gr-1+ CD11b+ MDSCs in the (A) spleens and (B) livers were analyzed by flow cytometry at day 7 after P. acnes priming (n = 6 mice per group). (C, D) Bone marrow cells of C57BL/6 mice were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF (10 ng/mL) and IL-6 (10 ng/mL) to induce MDSCs differentiation in vitro, and treated by vehicle (control) or EPZ-5676 (5 μM) for 4 days. (C) Percentage of MDSCs was analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) Percentage of apoptosis (annexin V+ PI–) cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. (E) BM cells of C57BL/6 mice were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-6 to induce MDSCs differentiation in vitro and were pretreated by vehicle (control) or EPZ-5676 (5 μM). Four days later, Gr-1+ cells were purified by MACS sorting and co-cultured with CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells activated by anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 3 days at indicated ratios. CD4+ T cells were stained for proliferation analysis by flow cytometry at the end of co-culture. Data are presented representative histograms at ratio of 1:8 and bar graph. Results are representative of 4–6 independent experiments. (F) Mice were treated with anti-Gr-1 (200 μg/mouse) or control antibody intraperitoneally. Frequencies of Gr-1+ CD11b+ MDSCs in the livers were analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 4 mice per group). (G) Cumulative survival rates of control and EPZ-5676–treated mice that injected with anti-Gr-1 antibody (200 μg/mouse, 4 times) to deplete MDSCs or control antibody in vivo, and then subjected to P. acnes/LPS-induced FH (n = 6 mice per group). Results are representative of 3–5 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. Significant differences were analyzed by (A, B) 1-way analysis of variance, (C, D, F) Mann-Whitney U test, (E) 2-way analysis of variance, or (G) log-rank test, and expressed as ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. n.s., not significant.

We next examined whether the depletion of liver recruitment of MDSCs impaired the alleviation of FH in EPZ-5676–treated mice. To this end, we specifically deleted the MDSCs by injection of anti-Gr-1 neutralizing antibody (Figure 7F) and challenged mice with P. acnes/LPS to induce FH. As expected, in vivo MDSC depletion largely abolished the difference of the survival rate between EPZ-5676–treated and P. acnes–primed control mice (Figure 7G). These results collectively established Dot1L inhibition as a critical mediator of MDSC suppressive function to protect inflammation-induced liver injury during FH pathogenesis.

Inhibition of Dot1L Enhances Suppressive Function of MDSCs by Increasing iNOS Expression Through STAT1 Signaling

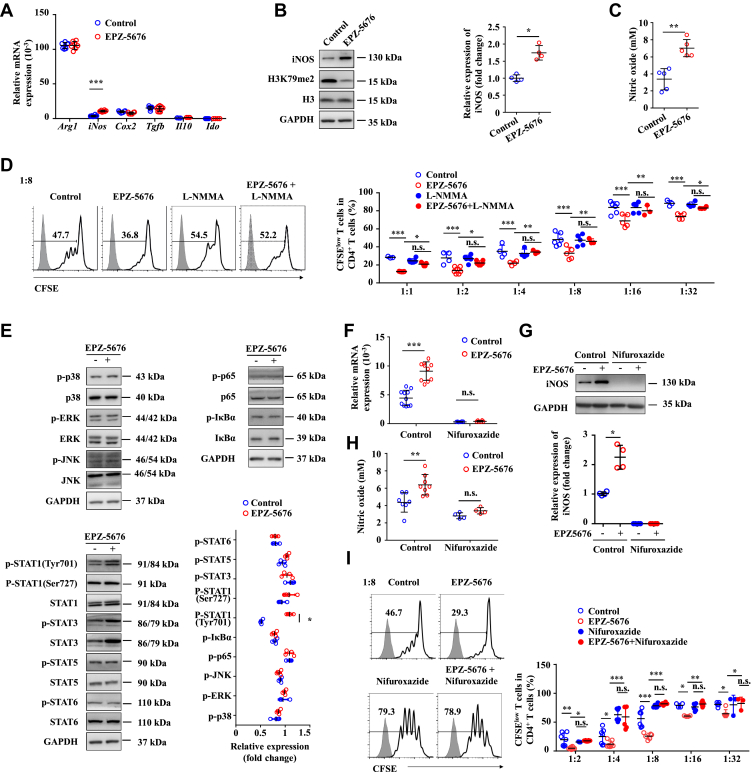

We next investigated the mechanisms by which Dot1L regulated the immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs. Several immunosuppressive factors, such as IDO (indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase), iNOS, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), Arg1 (arginase 1), and IL-10 are known to suppress T cell response by MDSCs.25 Among these suppressive factors, the expression of iNOS was the most strongly induced in the MDSCs treated by EPZ-5676 (Figure 8A). By contrast, the expression levels of IDO, COX2, TGF-β, Arg1, and IL-10 were not significantly changed by the Dot1L inhibition (Figure 8A). Western blot assay confirmed that the expression level of iNOS was increased in the EPZ-5676–treated MDSCs (Figure 8B). Accordingly, the concentration of NO in EPZ-5676–treated MDSC supernatant fraction significantly increased (Figure 8C). Furthermore, a functional study showed that L-NMMA, a specific inhibitor of iNOS activity, reversed the enhanced suppressive effects of EPZ-5676–treated MDSCs on T cell proliferation (Figure 8D). These data indicated that inhibition of Dot1L enhanced the immunosuppressive capacity of MDSCs mainly through upregulating iNOS expression.

Figure 8.

Inhibition of Dot1L enhances suppressive function of MDSCs by increasing iNOS expression through STAT1 signaling. BM cells of C57BL/6 mice were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-6 to induce MDSC differentiation in vitro, and were treated by vehicle (control) or EPZ-5676 (5 μM) for 4 days, then the mRNA, protein, and supernatant were collected. (A) mRNA expression levels of indicated genes, were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. (B) Protein expression level of iNOS was measured by immunoblotting. (C) The concentration of NO in cultural supernatant was detected by Griess reagent. (D) Control or EPZ-5676–treated MDSCs were also treated with L-NMMA (10 μM) and purified MDSCs were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells activated by anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 3 days at indicated ratios. CD4+ T cells were stained for proliferation analysis by flow cytometry at the end of co-culture. Data are presented representative histograms at ratio of 1:8 and as bar graph. (E) The expression levels of indicated protein were measure by immunoblotting. (F–H) Control or EPZ-5676–treated MDSCs were also treated with nifuroxazide (10 μM). Expression of iNOS was measured by (F) quantitative-real time PCR and (G) immunoblotting. (H) The concentration of NO in cultural supernatant was detected by Griess reagent. (I) Purified MDSCs were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells activated by anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 3 days at indicated ratios. CD4+ T cells were stained for proliferation analysis by flow cytometry at the end of co-culture. Data are presented representative histograms at ratio of 1:8 and bar graph. Results are representative of 3–5 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. Significant differences were analyzed by (A, D-I) 2-way analysis of variance, (B, C) Mann–Whitney U test, and expressed as ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001., n.s., not significant.

We further investigated the effect of Dot1L inhibition on the signal pathways involved in iNOS expression through detection of the phosphorylation status of MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), nuclear factor κB, and the STAT signaling pathway. No substantial difference was noted in the phosphorylation of ERK, JNK, p38, p65, and IκBα between EPZ-5676–treated MDSCs and control cells (Figure 8E). Hence, Dot1L exerted no effect on the activation of the MAPK and nuclear factor-κB pathways in the MDSCs. These results promote us to investigate the role of STAT signaling pathway in these cells. No differences in phosphorylation of STAT1 at Ser727 (p-STAT1-Ser727) and other members in STAT signaling pathway were observed between EPZ-5676–treated MDSCs and control cells. However, Dot1L inhibition considerably increased the phosphorylation of STAT1 levels at Tyr701 (p-STAT1-Tyr701) in the EPZ-5676–treated MDSCs (Figure 8E). Functionally, treatment with the STAT1 inhibitor nifuroxazide reversed the increased iNOS expression (Figure 8F and G) and NO production in EPZ-5676–treated MDSCs (Figure 8H). As a result, the enhanced suppressive effects on T cell proliferation by EPZ-5676–treated MDSCs were abolished upon the treatment of nifuroxazide (Figure 8I). Collectively, these data suggested that Dot1L inhibition induced the iNOS expression in MDSCs by activating STAT1 signaling pathway.

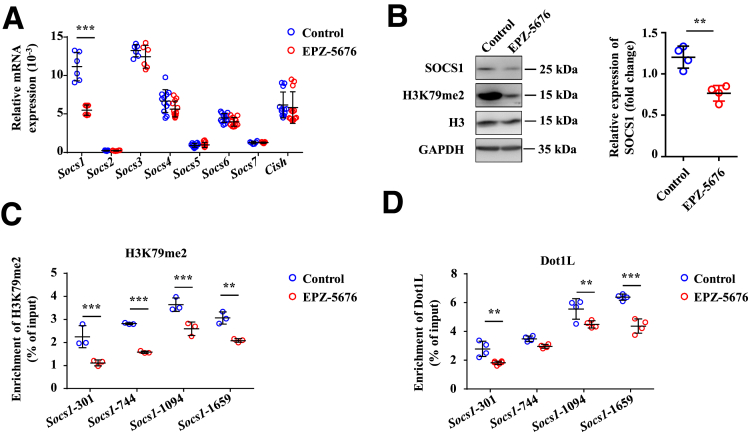

Dot1L Epigenetically Controls SOCS1 Expression in MDSCs

To further dissect the mechanistic role of Dot1L in regulating activation of STAT1 signaling, expression of SOCSs, negative regulation factors of STAT1 signaling pathway, which contain 8 subsets, was determined.26,27 We detected RNA expression of SOCSs in the EPZ-5676–treated and control MDSCs and found that SOCS1 was the most downregulated one in MDSCs treated with EPZ-5676 (Figure 9A and B). We next investigated the mechanisms by which Dot1L regulates SOCS1. In most cases, Dot1L regulates gene expression by adding positive marker H3K79me2 at gene promoters,9 and thus we hypothesize that Dot1L may directly regulate SOCS1 through epigenetic modification. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay indicated strong enrichment of H3K79me2 in the promoter regions (–2000 bp to transcription start site) of SOCS1 in control MDSCs (Figure 9C), whereas Dot1L inhibition significantly reduced the H3K79me2 levels at the promoters of SOCS1 (Figure 9C). In the control samples, Dot1L bound to the same promoter regions of SOCS1, and Dot1L inhibition significantly reduced the binding (Figure 9D). Collectively, these results established SOCS1 as a direct target that was fine-tuned by Dot1L-mediated H3K79me2 in MDSCs.

Figure 9.

Dot1L epigenetically controls SOCS1 expression in MDSCs. BM cells of C57BL/6 mice were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-6 to induce MDSC differentiation in vitro, and were treated by vehicle (control) or EPZ-5676 (5 μM) for 4 days, then the mRNA, protein, and supernatant were collected. (A) mRNA expression levels of indicated genes were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. (B) Protein expression level of SOCS1 was measured by immunoblotting. Enrichment of (C) H3K79me2 and (D) Dot1L at the promoter of SOCS1 was analyzed by ChIP-qPCR. Results are representative of 3–5 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. (A–D) Significant differences were analyzed by 2-way analysis of variance and expressed as ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, n.s., not significant.

Dot1L Expression Is Upregulated in Patients With Fulminant Hepatitis

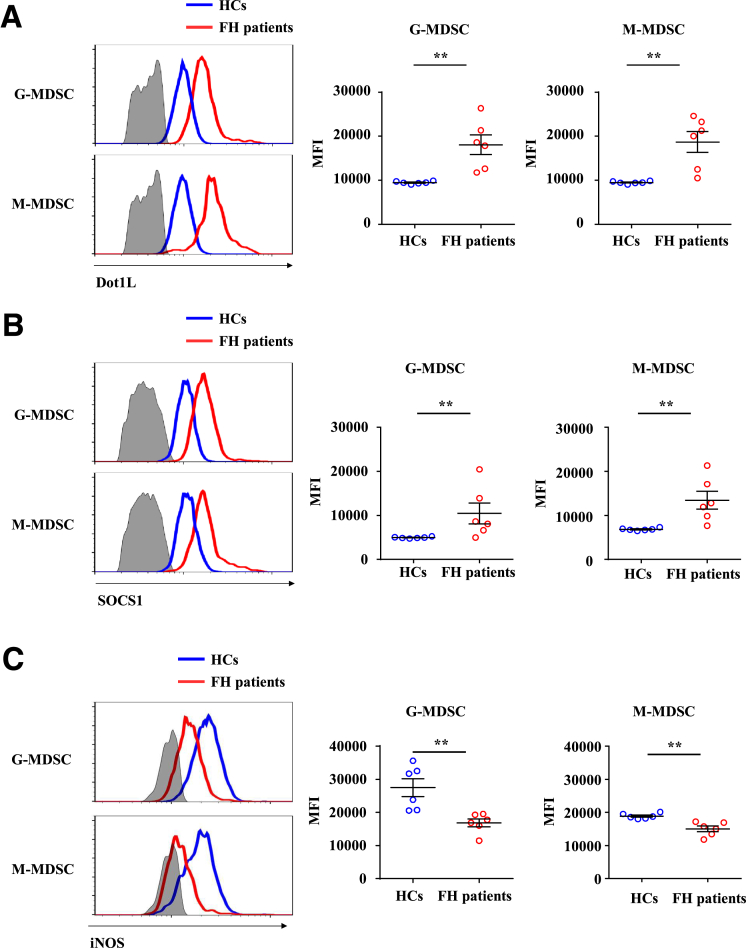

To evaluate whether the Dot1L-SOCS1-iNOS axis in MDSCs contributes to FH progression, we analyzed Dot1L, SOCS1, and iNOS expression in MDSCs of peripheral blood between patients with FH and healthy control subjects. Owing to lack of appropriate markers for the whole population of MDSCs in human, we detected the expression of Dot1L, SOCS1 and iNOS in granulocytic MDSCs and monocytic MDSCs separately. Consistent with the results in the mouse model of FH, Dot1L (Figure 10A) and SOCS1 (Figure 10B) were upregulated in both granulocytic MDSCs and monocytic MDSCs, accompanied by decreased expression of iNOS (Figure 10C) in peripheral blood of patients with FH compared with healthy control subjects. Altogether, these data showed that the Dot1L-SOCS1-iNOS axis might contribute to the progression of FH.

Figure 10.

Dot1L expression is upregulated in patients with fulminant hepatitis. Peripheral blood of patients with FH and healthy control subjects was collected and treated with red blood cell lysis buffer. Expression of (A) Dot1L, (B) SOCS1, and (C) iNOS in monocytic MDSCs (gated on Lin–HLA-DR–CD14+ cells) and granulocytic MDSCs (gated on CD11b+CD15+CD14–CD33+/loCD66b+ cells) were measured by flow cytometry. Lin contains CD3, CD19, CD20, and CD56. Results are representative of 3–5 independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. (A–C) Significant differences were analyzed by Mann–Whitney U test and expressed as ∗∗P < .01.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that inhibition of Dot1L effectively attenuates the severity of inflammation-induced liver injury and increases survival rate of mice subjected to P. acnes plus LPS-induced FH. In terms of mechanism, Dot1L inhibition enhances immunosuppressive function of MDSCs through increasing the production of iNOS in a STAT1-dependent manner. Moreover, Dot1L inhibition downregulates H3K79me2 level at the promoters of SOCS1, which is responsible for the activation of STAT1 signaling pathway in MDSCs. These MDSCs inhibit Th1 cells and induce Tregs, resulting in amelioration of FH.

Recent conceptual advances support an important role of MDSCs as a key inhibition factor of FH.17,18 However, important knowledge gaps remain as to how epigenetic modifications regulate suppressive function of MDSCs to influence the inflammatory-induced liver injury process. In this context, the current study provides several advances: (1) Dot1L inhibition enhances immunosuppressive function of MDSCs through increasing the production of iNOS; (2) Dot1L induces transcription of SOCS1 by mediating H3K79me2 at its promoters, leading to repression of STAT1-dependent iNOS expression; (3) pharmacologic inhibition of Dot1L protects animals against inflammatory liver injury, while MDSC depletion impairs therapeutic effect of Dot1L inhibition on FH. Although our studies corroborate prior concepts related to amelioration of inflammatory liver injury by MDSCs, the primary significance of these studies lies in the paradigm that epigenetic regulators restrain the suppressive function of MDSCs in inflammatory disease. These changes promote pathogenic CD4+ T cells activation and progression of liver injury. In turn, interventions targeting these newly discovered pathways may have the capability to prevent, delay, or reverse the inflammatory response that drive FH.

FH is a life-threatening disease and liver transplantation is the only definitive treatment for the acute liver injury. However, the obvious limitations of transplantation, such as shortage of donor, immune rejection, and side effect of immunosuppressive drugs, etc., suggested an urgency to develop novel therapeutic strategies.1,5,28 Recently, histone methylation has been considered to be involved in the regulation of liver injury.29,30 For example, EZH2, which catalyzes H3K27me3, contributed to the pathogenesis of liver failure through triggering TNF and other indispensable proinflammatory cytokines.30 We found that inhibition of Dot1L, a H3K79 methyltransferase, ameliorated liver injury, and improved survival rate of FH in mice through inhibiting activation, proliferation, and cytokine production of CD4+ T cells in vivo. However, we demonstrated that Dot1L inhibitor did not affect T cell responses when administrated in in vitro culture. Earlier study suggested that Dot1L inhibition prevented allogeneic T cell responses and attenuated the development of graft-vs-host disease, while retaining potent antitumor activity in adoptive immunotherapy models.13 However, Dot1L inhibition selectively ameliorated low-avidity T cell responses but not high-avidity T cell responses mediated by the T cell receptor.13 Thus, Dot1L inhibition restricted the CD4+ T cell response through an indirect mechanism during FH pathogenesis.

MDSCs are critical to maintain the immunosuppressive niche in inflamed liver during the pathogenesis of various kinds of human hepatitis and related mouse models, and increased infiltration of MDSCs effectively attenuates the liver inflammation and protects inflammation-induced acute liver failure.17,18,31,32 Although our study showed that mice with P. acnes–induced liver injury contained more CD11b+ Gr-1+ MDSCs than naive mice, it is not surprising. Because, it has been reported that inflammation is required for induction of MDSCs, and Th1 cells induce the accumulation of MSDCs in the liver by production of IFN-γ.33,34 Most of these studies focused on the mechanism of MDSC generation from HSPCs or recruitment of MDSCs into the liver during liver injury.17,18 Our study also found increased percentage of MDSCs in the liver, spleen, and peripheral blood. Thus, Dot1L inhibition attenuated both hepatic and peripheral inflammation in the P. acnes–induced acute liver injury. Considering the known function of Dot1L on hematopoiesis, by maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells and lineage-specific progenitors in homeostatic conditions,10 we also tested the development of MDSCs upon Dot1L inhibition. We proved that EPZ-5676 promoted BM cells to differentiate into MDSCs in vitro without affecting their apoptosis. However, the molecular mechanism through which driving the immunosuppressive function of MDSCs in the inflamed liver remains elusive.

MDSCs have been shown to exert their immunoregulatory effects through expression of immune suppressive factors such as arginase (encoded by Arg1), iNOS, and COX2, and an increase in the secretion of TGF-β and IL-10.25 Among those immune suppressive factors, only iNOS expression was significantly increased with decreased level of H3K79me2 upon Dot1L inhibitor treatment, which resulted in increased production of NO in the surrounding of MDSCs, leading to T cell cycle arrest and proliferation inhibition.35 In addition, NO depletion via L-NMMA reversed the enhanced immunosuppression in Dot1L-inhibited MDSCs. These results suggested that Dot1L negatively regulated the expression of iNOS by H3K79me2. Moreover, we showed that this process was mediated by activation of STAT1 signaling pathway. STAT1 is the major transcription factor activated by IFN-γ signaling in the tumor microenvironment, the upregulation of iNOS expression in MDSCs involved a STAT1-dependent mechanism. Indeed, MDSCs from STAT1–/– mice failed to upregulate iNOS expression and therefore did not inhibit T cell responses.36 Consistently, our study demonstrated that the activation level of STAT1 was significantly increased upon Dot1L inhibition in MDSCs, while after inhibition of STAT1 signaling using specific inhibitor-Nifuroxazide, the increased expression of iNOS and NO production resulted from intervening Dot1L-mediated H3K79me2 was abolished. These results suggested that Dot1L inhibition mediated immunosuppressive function of MDSCs through induction of iNOS expression in a STAT1 signaling–dependent manner.

Dot1L functions cover various physiologic and pathologic processes, including transcription regulation, cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, embryonic hematopoiesis, cardiac function, and leukemia.9,10 All these are dependent on its H3K79 methyltransferase activity. Genome-wide analysis indicates a tight connection between H3K79 methylation and gene transcription activity. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae and flies, Dot1L and H3K79me2 are both found at the promoters of transcriptionally active genes.37,38 H3K79me2 modifications also exist in many promoters of transcriptionally active genes in mammalian cells.39 Dot1L-mediated H3K79me2/3 modifications appear around transcription start site regions of the Il6 and Ifnb1 promoters, resulting increased IL-6 and IFN-β production.12 Similarly, in our study, we have shown that Dot1L-mediated H3K79me2 directly targets SOCS1 for its transcriptional activation. It is known that SOCS1 is an inhibitor of STAT1 signaling pathway, which explains increased iNOS expression in MDSCs and inhibited T cell responses in FH upon Dot1L inhibition. As no report has shown that Dot1L contains a specific DNA-binding domain, Dot1L may specifically target specific promoters via other binding proteins. AF9 acts as a bridge protein to recruit Dot1L to transcriptionally active genes decorated with H3K9ac and helps maintain the open chromatin state.40 AF10 recognizes unmodified H3K27, but not methylated H3K27, and recruits Dot1L to specific genomic regions.41 Thus, other proteins or noncoding RNAs may be involved in the selective recruitment of Dot1L to the SOCS1 promoter in MDSCs, which needs to be further explored.

EPZ-5676 (pinometostat) used in this study, a first-in-class small-molecule inhibitor of Dot1L, completed phase I clinical trials for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory acute leukemia bearing a rearrangement of the MLL gene (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01684150 and https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02141828). These studies suggested that administration of EPZ-5676 was generally safe, and have modest therapeutic activity in treatment of adult acute leukemia.42 Currently, EPZ-5676 has been further tested in phase Ib/II trial studies for combination therapies in leukemia with azacitidine or standard chemotherapy (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03701295 and https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03724084). Thus, EPZ-5676 might be a clinically relevant approach to modulate the acute liver injury.

In conclusion, we showed that Dot1L inhibitor EPZ-5676 has profound inhibitory effects on inflammatory responses and that it ultimately improves survival in mice undergoing P. acnes plus LPS-induced FH. Furthermore, we demonstrated that Dot1L-mediated H3K79me2 directly targeted and promoted the expression of SOCS1. Dot1L inhibition–induced downregulation of SOCS1 mediates activation of STAT1 signaling pathway, leading to increased production of iNOS in MDSCs, which inhibited Th1 cell response and induced Tregs expansion. These results indicate that targeting Dot1L using EPZ-5676 may represent a novel and clinically relevant approach to treat this devastating liver disease.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Mice

EPZ-5676 (Cat. No. S7062), L-NMMA (Cat. No. S2877), and nifuroxazide (Cat. No. S4182) were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX). For in vivo experiments, EPZ-5676 was dissolved in 2% DMSO + 30% PEG 300 + 5% Tween 80 + ddH2O as recommended by Selleckchem. Antibodies against iNOS (Cat. No. 13120), H3K79me2 (Cat. No. 5427), H3 (Cat. No. 4499), GAPDH (Cat. No. 2118), p-p38 (Cat. No. 4511), p38 (Cat. No. 8690), p-ERK (Cat. No. 4370), ERK (Cat. No. 4695), p-JNK (Cat. No. 4668), JNK (Cat. No. 9252), p-p65 (Cat. No. 3033), p65 (Cat. No. 8242), p-IκBα (Cat. No. 2859), IκBα (Cat. No. 4812), p-STAT1 (Tyr701) (Cat. No. 9167), p-STAT1 (Ser727) (Cat. No. 8826), STAT1 (Cat. No. 9172), p-STAT3 (Tyr705) (Cat. No. 9145), STAT3 (Cat. No. 9132), p-STAT5 (Tyr694) (Cat. No. 9359), STAT5 (Cat. No. 25656), p-STAT6 (Tyr641) (Cat. No. 9361), and STAT6 (Cat. No. 9362) were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). P. acnes (Cat. No. 11827) was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA), and LPS (Cat. No. L2630) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in the vivarium of Shanghai Institute of Nutrition and Health, Chinese Academy of Sciences. All animal experiments were performed according to the guide of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences and complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Processing of Human Blood Samples

Peripheral blood samples of HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure patients (n = 6) and healthy control subjects (n = 6) were collected from Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. Characterization was based on Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver criteria.43 Among these HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure patients, 2 of them suffered HBV for more than 30 years, 1 for 23 years, 2 for 10 years, and 1 for 5 years. And 4 out of 6 patients were cirrhotic. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained from the patients using red blood cell lysis buffer.

Induction of Liver Injury

Female C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks old) were primed intravenously with 1 mg of heat-killed P. acnes suspended in 200 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For survival analysis, mice were injected intravenously with 1 μg of LPS on day 7 after P. acnes priming. For the indicated experiments, EPZ-5676 was administrated at a dose of 35 mg/kg intraperitoneally on days 0, 2, 4, and 6. Liver specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin-embedded. Deparaffinized sections (5–10 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Liver MNCs were purified by a Percoll gradient while spleen MDSCs were purified by a Ficoll gradient. In some experiments, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 200 μg anti-Gr-1 antibody (Cat. No. BE0075; Bio X Cell, Lebanon, NH) 4 times to deplete MDSCs in vivo.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from tissues or cells at indicated time points, and was subsequently extracted with TRIzol (Cat. No. 15596018; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and reverse-transcribed in to complementary DNA using the reverse transcription kit (Cat. No. 2690C; Takara Bio, Kyoto, Japan). The levels of messenger RNA were measured by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with SYBR Green reagent (Cat. No. 4913914001; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) on a QuantStudio 7 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The expression of individual genes was normalized to the messenger RNA level of β-actin. The gene-specific PCR primers (all for mouse genes) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Primers

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| β-actin forward | 5′-TGTCCACCTTCCAGCAGATGT-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-AGCTCAGTAACAGT-CCGCCTAGA-3′ |

| FasL forward | 5′-GTTTTTCCCTGTCCATCTTGTG-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-TCTTCTTTAGAGGGGTCAGTGG-3′ |

| Arg1 forward | 5′-ATTATCGGAGCGCCTTTCTC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-ACAGACCGTGGGTTCTTCAC-3′ |

| iNos forward | 5′-TGGAGCGAGTTGTGGATTGT-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-GGGTCGTAATGTCCAGGAAGTA-3′ |

| Cox2 forward | 5′-AACCCAGGGGATCGAGTGT-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-CGCAGCTCAGTGTTTGGGAT-3′ |

| Tgfb forward | 5′-CTCCCGTGGCTTCTAGTGC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-GCCTTAGTTTGGACAGGATCTG-3′ |

| Il10 forward | 5′-GCTGCTTTGCCTACCTCTCC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-TCGAGTGACAAACACGACTGC-3′ |

| Ido forward | 5′-GCTTTGCTCTACCACATCCA-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-CAGGCGCTGTAACCTGTGT-3′ |

| Socs1 forward | 5′-CTGCGGCTTCTATTGGGGAC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-AAAAGGCAGTCGAAGGTCTCG-3′ |

| Socs2 forward | 5′-GTGGGGAACTCGTCCTATCTG-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-GTCACAGTGTAATGATGTGCCA-3′ |

| Socs3 forward | 5′-ATGGTCACCCACAGCAAGTTT-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-TCCAGTAGAATCCGCTCTCCT-3′ |

| Socs4 forward | 5′-CGGAGTCGAAGTGCTGACAG-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-ACTCAATGGACGAACAGCTAAG-3′ |

| Socs5 forward | 5′-GAGGGAGGAAGCCGTAATGAG-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-CGGCACAGTTTTGGTTCCG-3′ |

| Socs6 forward | 5′-AAGCAAAGACGAAACTGAGTTCA-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-CGCTGCCAATGTCACAACTG-3′ |

| Socs7 forward | 5′-TCAGTCGCCTGTTTCGCAC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-GTTTCCTCCCCGTATCCAGC-3′ |

| Cish forward | 5′-ATGGTCCTTTGCGTACAGGG-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-GGAATGCCCCAGTGGGTAAG-3′ |

| Socs1-301 forward | 5′-CCAAGTCCTAAGCACCCCAG-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-TAACTTGGTTTCGCCTCGCA-3′ |

| Scos1-744 forward | 5′-TGCTTGCTGGAGTCTTGACC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-GCACTCTTACTACGTGGGCA-3′ |

| Socs1-1094 forward | 5′-GCACCAATAAGCCTGCCAAG-3′ |

| reverse | 5′- CCCCAAACTGTGCTTCCAG-3′ |

| Socs1-1659 forward | 5′-ACCACGTTTTGCATCCAAGC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-ATAGCTGCTTCCTGACCCAC-3′ |

| Ccl21 forward | 5′-CCCATCCCGGCAATCCTGTT-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-CTTTCTTTCCAGACTTAGAGGTTCCCC-3′ |

| Cxcl9 forward | 5′-TACAAATCCCTCAAAGACCTCAAACAG-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-ATCTTCTTTTCCCATTCTTTCATCAGC-3′ |

| Cxcl10 forward | 5′-CCAAGTGCTGCCGTCATTTTC-3′ |

| reverse | 5′-GGCTCGCAGGGATGATTTCAA-3′ |

PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

TUNEL Assay

Collected liver tissues were routinely embedded into optimal cutting temperature and then were stored at –80°C. For TUNEL assay, apoptotic cells were detected using a TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit (Alexa Fluor 488, Cat. No. 40307ES60; YEASEN Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow Cytometry

The collected immune cell suspensions from liver or spleen were stained with the indicated antibodies and were subjected to flow cytometry analyses using CytoFLEX LX (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). For the intracellular staining of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and Foxp3, the cells were fixed and permeabilized by fixation and permeabilization buffer (Cat. No. 00-5523; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) before staining. Specific monoclonal antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ), BioLegend (San Diego, CA), or Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA): CD4 (GK1.5), BrdU (3D4), CD44 (IM7), CD62L (MEL-14), TNF-α (MP6-XT22), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), and Foxp3 (MF-14), CD25 (PC61), CD69 (H1.2F3), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), CD11b (M1/70), CCR7 (4B12), CXCR3 (CXCR3-173), CD11c (N418), F4/80 (BM8), major histocompatibility complex class II (M5/114.15.2), CD86 (GL-1), CD14 (M5E2), CD15 (W6D3), CD11b (ICRF44), CD33 (P67.6), CD66b (G10F5), and HLA-DR (L243). And we used combination of CD3 (HIT3a), CD19 (4G7), CD20 (2H7), and CD56 (5.1H11) as Lin cocktail.

In Vivo BrdU Incorporation

Seven days after P. acnes priming, 1-mg BrdU (Cat. No. 559619, BD Pharmingen) in 100-μL PBS was intraperitoneally injected into EPZ-5676 or Vehicle-treated mice. The mice were euthanized 12 h after the BrdU administration, and the immune cell suspensions from livers or spleens were prepared for flow cytometric analysis.

Induction of MDSCs In Vitro

Murine MDSCs were generated in vitro from the BM of C57BL/6 mice. BM was flushed, and red blood cells were lysed with red blood cell lysis buffer. To obtain MDSCs, the remaining cells were cultured with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (40 ng/mL, Cat. No. AF-315-03-20; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and IL-6 (40 ng/mL, Cat. No. AF-216-16-10, PeproTech). Four days later, MDSCs were purified by immunomagnetic separation using biotinylated anti-Gr-1 antibodies (Cat. No. 130-120-829; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and streptavidin-conjugated MicroBeads (Cat. No. 130-048-101; Miltenyi Biotec) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Cell purity was confirmed by flow cytometric analysis (purity >95%). For differentiation assays, BM cells were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF (10 ng/mL) and IL-6 (10 ng/mL).

T Cell Proliferation Assay

CD4+ T cells isolated from spleen and lymph nodes were purified by immunomagnetic separation (Cat. No. 130-042-401; Miltenyi Biotec) and were labeled with 5-μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Cat. No. C34554; Thermo Fisher Scientific). CD4+ T cells were cultured in 96-well-plate in the presence of plate-coated anti-CD3 antibody (5 μg/mL, Cat. No. 16-0031-86; eBioscience) and soluble anti-CD28 antibody (2 μg/mL, Cat. No. 16-0281-86; eBioscience). In some experiment, CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with MDSCs of different treatments at the indicated ratios for 72 hours. The cell proliferation was then determined by flow cytometry.

Immunoblotting

Cells were harvested and lysed in the RIPA lysis buffer (Cat. No. P0013C; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Cat. No. 539131; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for 30 minutes on ice. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 30 minutes. Protein concentration of the supernatant fraction was determined by the Bradford assay (Cat. No. 23246; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein samples were diluted in 4× sodium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer (Cat. No. 9173, TaKaRa) and heated at 95°C for 5 minutes and fractionated in a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, separated proteins were transferred onto PVDF membrane (Cat. No. IPVH00010; Millipore, Burlington, MA) and incubated for 1 hour in 5% bovine serum albumin in PBS at room temperature. The blotting membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, extensively washed in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (Cat. No. 7074S; Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 hour at room temperature, and washed again. The blotting membranes were detected with chemiluminescent reagents (Cat. No. WBAVDCH01; Millipore).

Griess Assay

Fifty-microliter culture supernatant fraction of different treated MDSCs and standards were added to a flat bottomed 96-well-plate, and then 50 μL of Griess reagent A and 50 μL of Griess reagent B (Cat. No. G4410; Sigma-Aldrich) were added sequentially. Read the absorbance at 540 nm after incubation for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature, and calculated NO concentrations.

ChIP Assay

Chromatin of MDSCs (1 × 107) was prepared using EZ-ChIP Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit (Cat. No. 17-371; Millipore) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated using anti-Dot1L, anti-H3K79me2 or respective IgGs. ChIP-enriched and input DNA were extracted by PCR Cleanup Kit (Cat. No. AP-PCR-500G; Axygen, Union City, CA) and analyzed by quantitative PCR, with the inputs as the internal control. Primers for ChIP assay were provided in Table 1. Regions of SOCS1 promoter used for ChIP assay were ranged from –2000 bp to transcription start site. This region was averagely divided into 4 parts to cover the promoter area by 1 set of primers per 500 bp.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

All data was showed as mean ± SD and performed at least 3 independent experiments. Significant differences were evaluated using Mann–Whitney U test, except that multiple treatment groups were compared within individual experiments by analysis of variance test. Log-rank test was used for survival analysis. Significance was expressed as ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001.

Acknowledgments

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Wanlin Yang (Formal analysis: Lead; Investigation: Lead; Methodology: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead)

Hongshuang Yu (Formal analysis: Lead; Investigation: Lead; Methodology: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead)

Jiefang Huang (Methodology: Supporting)

Xiang Miao (Methodology: Supporting)

Qiwei Wang (Methodology: Supporting)

Yanan Wang (Funding acquisition: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting)

Yiji Cheng (Funding acquisition: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting)

Shan He (Funding acquisition: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting)

Fang Zhao (Funding acquisition: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting)

Lijun Meng (Funding acquisition: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Project administration: Supporting)

Bei Wang (Investigation: Supporting)

Fengtao Qian (Methodology: Supporting)

Xiaohui Ren (Methodology: Supporting)

Min Jin (Formal analysis: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting)

Yuting Gu (Funding acquisition: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

Yanyun Zhang (Funding acquisition: Lead; Supervision: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

Wei Cai (Funding acquisition: Supporting; Supervision: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81900565, 81800518, 82000567, 81670540, 81700656, 81873447, 81700172, 81700171, 81700170, and 81470867) and the Program of Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (19ZR1430900 and 20ZR1433500).

Contributor Information

Yuting Gu, Email: guyutingxm@126.com.

Yanyun Zhang, Email: yyzhang@sibs.ac.cn.

Wei Cai, Email: carieyc@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Bernal W., Wendon J. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2525–2534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stravitz R.T., Lee W.M. Acute liver failure. Lancet. 2019;394:869–881. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31894-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antoniades C.G., Berry P.A., Wendon J.A., Vergani D. The importance of immune dysfunction in determining outcome in acute liver failure. J Heptaol. 2008;49:845–861. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Possamai L.A., Thursz M.R., Wendon J.A., Antoniades C.G. Modulation of monocyte/macrophage function: a therapeutic strategy in the treatment of acute liver failure. J Heptaol. 2014;61:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stravitz R.T., Kramer D.J. Management of acute liver failure. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:542–553. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campisano S., La Colla A., Echarte S.M., Chisari A.N. Interplay between early-life malnutrition, epigenetic modulation of the immune function and liver diseases. Nutr Res Rev. 2019;32:128–145. doi: 10.1017/S0954422418000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann D.A. Epigenetics in liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;60:1418–1425. doi: 10.1002/hep.27131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy T., Mann D.A. Epigenetics in liver disease: from biology to therapeutics. Gut. 2016;65:1895–1905. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLean C.M., Karemaker I.D., van Leeuwen F. The emerging roles of DOT1L in leukemia and normal development. Leukemia. 2014;28:2131–2138. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jo S.Y., Granowicz E.M., Maillard I., Thomas D., Hess J.L. Requirement for Dot1l in murine postnatal hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis by MLL translocation. Blood. 2011;117:4759–4768. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen A.T., Zhang Y. The diverse functions of Dot1 and H3K79 methylation. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1345–1358. doi: 10.1101/gad.2057811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X., Liu X., Zhang Y., Huai W., Zhou Q., Xu S., Chen X., Li N., Cao X. Methyltransferase Dot1l preferentially promotes innate IL-6 and IFN-β production by mediating H3K79me2/3 methylation in macrophages. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:76–84. doi: 10.1038/s41423-018-0170-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kagoya Y., Nakatsugawa M., Saso K., Guo T., Anczurowski M., Wang C.-H., Butler M.O., Arrowsmith C.H., Hirano N. DOT1L inhibition attenuates graft-versus-host disease by allogeneic T cells in adoptive immunotherapy models. Nat Commun. 2018;9 doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04262-0. 1915–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veglia F., Perego M., Gabrilovich D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:108–119. doi: 10.1038/s41590-017-0022-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pal S., Nandi M., Dey D., Chakraborty B.C., Shil A., Ghosh S., Banerjee S., Santra A., Ahammed S.K.M., Chowdhury A., Datta S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells induce regulatory T cells in chronically HBV infected patients with high levels of hepatitis B surface antigen and persist after antiviral therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:1346–1359. doi: 10.1111/apt.15226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diao W., Jin F., Wang B., Zhang C.-Y., Chen J., Zen K., Li L. The protective role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in concanavalin A-induced hepatic injury. Protein Cell. 2014;5:714–724. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0069-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarra M., Cupi M.L., Bernardini R., Ronchetti G., Monteleone I., Ranalli M., Franzè E., Rizzo A., Colantoni A., Caprioli F., Maggioni M., Gambacurta A., Mattei M., Macdonald T.T., Pallone F., Monteleone G. IL-25 prevents and cures fulminant hepatitis in mice through a myeloid-derived suppressor cell-dependent mechanism. Hepatology. 2013;58:1436–1450. doi: 10.1002/hep.26446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J., Pei S., Wang Y., Liu J., Qian Y., Huang M., Zhang Y., Xiao Y. Tpl2 Protects against fulminant hepatitis through mobilization of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Front Immunol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01980. 1980–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou J., Huang S., Wang Z., Huang J., Xu L., Tang X., Wan Y.Y., Li Q.-J., Symonds A.L.J., Long H., Zhu B. Targeting EZH2 histone methyltransferase activity alleviates experimental intestinal inflammation. Nat Commun. 2019;10 doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10176-2. 2427–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang S., Wang Z., Zhou J., Huang J., Zhou L., Luo J., Wan Y.Y., Long H., Zhu B. EZH2 inhibitor GSK126 suppresses antitumor immunity by driving production of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2019;79:2009–2020. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuji H., Mukaida N., Harada A., Kaneko S., Matsushita E., Nakanuma Y., Tsutsui H., Okamura H., Nakanishi K., Tagawa Y., Iwakura Y., Kobayashi K., Matsushima K. Alleviation of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute liver injury in Propionibacterium acnes-primed IFN-gamma-deficient mice by a concomitant reduction of TNF-alpha, IL-12, and IL-18 production. J Immunol. 1999;162:1049–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka Y., Takahashi A., Kobayashi K., Arai I., Higuchi S., Otomo S., Watanabe K., Habu S., Nishimura T. Establishment of a T cell-dependent nude mouse liver injury model induced by Propionibacterium acnes and LPS. J Immunol Methods. 1995;182:21–28. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okazaki T., Ozaki S., Nagaoka T., Kozuki M., Sumita S., Tanaka M., Osakada F., Kishimura M., Kakutani T., Nakao K. Antigen-specific T(h)1 cells as direct effectors of Propionibacterium acnes-primed lipopolysaccharide-induced hepatic injury. Int Immunol. 2001;13:607–613. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoneyama H., Harada A., Imai T., Baba M., Yoshie O., Zhang Y., Higashi H., Murai M., Asakura H., Matsushima K. Pivotal role of TARC, a CC chemokine, in bacteria-induced fulminant hepatic failure in mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1933–1941. doi: 10.1172/JCI4619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gabrilovich D.I., Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durham G.A., Williams J.J.L., Nasim M.T., Palmer T.M. Targeting SOCS proteins to control JAK-STAT signalling in disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019;40:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander W.S., Hilton D.J. The role of suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins in regulation of the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:503–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.091003.090312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dutkowski P., Oberkofler C.E., Béchir M., Müllhaupt B., Geier A., Raptis D.A., Clavien P.-A. The model for end-stage liver disease allocation system for liver transplantation saves lives, but increases morbidity and cost: a prospective outcome analysis. Liver Transplant. 2011;17:674–684. doi: 10.1002/lt.22228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y., Xue W., Zhang W. Histone methyltransferase G9a protects against acute liver injury through GSTP1. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:1243–1258. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0412-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou T., Sun Y., Li M., Ding Y., Yin R., Li Z., Xie Q., Bao S., Cai W. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2-catalysed H3K27 trimethylation plays a key role in acute-on-chronic liver failure via TNF-mediated pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:590. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0670-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernsmeier C., Triantafyllou E., Brenig R., Lebosse F.J., Singanayagam A., Patel V.C., Pop O.T., Khamri W., Nathwani R., Tidswell R., Weston C.J., Adams D.H., Thursz M.R., Wendon J.A., Antoniades C.G. CD14(+) CD15(-) HLA-DR(-) myeloid-derived suppressor cells impair antimicrobial responses in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gut. 2018;67:1155–1167. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang A., Zhang B., Yan W., Wang B., Wei H., Zhang F., Wu L., Fan K., Guo Y. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells regulate immune response in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection through PD-1-induced IL-10. J Immunol. 2014;193:5461–5469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cripps J.G., Wang J., Maria A., Blumenthal I., Gorham J.D. Type 1 T helper cells induce the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the inflamed Tgfb1 knockout mouse liver. Hepatology. 2010;52:1350–1359. doi: 10.1002/hep.23841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bunt S.K., Sinha P., Clements V.K., Leips J., Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Inflammation induces myeloid-derived suppressor cells that facilitate tumor progression. J Immunol. 2006;176:284–290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez P.C., Quiceno D.G., Ochoa A.C. L-arginine availability regulates T-lymphocyte cell-cycle progression. Blood. 2007;109:1568–1573. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-031856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kusmartsev S., Nagaraj S., Gabrilovich D.I. Tumor-associated CD8+ T cell tolerance induced by bone marrow-derived immature myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:4583–4592. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schübeler D., MacAlpine D.M., Scalzo D., Wirbelauer C., Kooperberg C., van Leeuwen F., Gottschling D.E., O’Neill L.P., Turner B.M., Delrow J., Bell S.P., Groudine M. The histone modification pattern of active genes revealed through genome-wide chromatin analysis of a higher eukaryote. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1263–1271. doi: 10.1101/gad.1198204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pokholok D.K., Harbison C.T., Levine S., Cole M., Hannett N.M., Lee T.I., Bell G.W., Walker K., Rolfe P.A., Herbolsheimer E., Zeitlinger J., Lewitter F., Gifford D.K., Young R.A. Genome-wide map of nucleosome acetylation and methylation in yeast. Cell. 2005;122:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vakoc C.R., Sachdeva M.M., Wang H., Blobel G.A. Profile of histone lysine methylation across transcribed mammalian chromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9185–9195. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01529-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y., Wen H., Xi Y., Tanaka K., Wang H., Peng D., Ren Y., Jin Q., Dent S.Y.R., Li W., Li H., Shi X. AF9 YEATS domain links histone acetylation to DOT1L-mediated H3K79 methylation. Cell. 2014;159:558–571. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen S., Yang Z., Wilkinson A.W., Deshpande A.J., Sidoli S., Krajewski K., Strahl B.D., Garcia B.A., Armstrong S.A., Patel D.J., Gozani O. The PZP domain of AF10 senses unmodified H3K27 to regulate DOT1L-mediated methylation of H3K79. Mol Cell. 2015;60:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stein E.M., Garcia-Manero G., Rizzieri D.A., Tibes R., Berdeja J.G., Savona M.R., Jongen-Lavrenic M., Altman J.K., Thomson B., Blakemore S.J., Daigle S.R., Waters N.J., Suttle A.B., Clawson A., Pollock R., Krivtsov A., Armstrong S.A., DiMartino J., Hedrick E., Löwenberg B., Tallman M.S. The DOT1L inhibitor pinometostat reduces H3K79 methylation and has modest clinical activity in adult acute leukemia. Blood. 2018;131:2661–2669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-12-818948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarin S.K., Choudhury A., Sharma M.K., Maiwall R., Al Mahtab M., Rahman S., Saigal S., Saraf N., Soin A.S., Devarbhavi H., Kim D.J., Dhiman R.K., Duseja A., Taneja S., Eapen C.E., Goel A., Ning Q., Chen T., Ma K., Duan Z., Yu C., Treeprasertsuk S., Hamid S.S., Butt A.S., Jafri W., Shukla A., Saraswat V., Tan S.S., Sood A., Midha V., Goyal O., Ghazinyan H., Arora A., Hu J., Sahu M., Rao P.N., Lee G.H., Lim S.G., Lesmana L.A., Lesmana C.R., Shah S., Prasad V.G.M., Payawal D.A., Abbas Z., Dokmeci A.K., Sollano J.D., Carpio G., Shresta A., Lau G.K., Fazal Karim M., Shiha G., Gani R., Kalista K.F., Yuen M.F., Alam S., Khanna R., Sood V., Lal B.B., Pamecha V., Jindal A., Rajan V., Arora V., Yokosuka O., Niriella M.A., Li H., Qi X., Tanaka A., Mochida S., Chaudhuri D.R., Gane E., Win K.M., Chen W.T., Rela M., Kapoor D., Rastogi A., Kale P., Rastogi A., Sharma C.B., Bajpai M., Singh V., Premkumar M., Maharashi S., Olithselvan A., Philips C.A., Srivastava A., Yachha S.K., Wani Z.A., Thapa B.R., Saraya A., Shalimar, Kumar A., Wadhawan M., Gupta S., Madan K., Sakhuja P., Vij V., Sharma B.C., Garg H., Garg V., Kalal C., Anand L., Vyas T., Mathur R.P., Kumar G., Jain P., Pasupuleti S.S.R., Chawla Y.K., Chowdhury A., Alam S., Song D.S., Yang J.M., Yoon E.L. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL): an update. Hepatol Int. 2019;13:353–390. doi: 10.1007/s12072-019-09946-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]