Abstract

Introduction

Pressure injury (PI) is a potentially serious condition that is often a consequence of other medical illnesses. It remains a challenge for the clinicians and the researcher to fully understand and develop a technique for comprehending pathogenicity, prevention and treatment. Several animal models have been created to understand the multifaceted cellular and biochemical processes of PI. There are numerous known intrinsic and extrinsic factors influencing the recovery of PI. Some of the important factors are friction, spinal cord injury, diabetes, nutrition, aging, infection, medication, obesity and vascular diseases. The dearth of optimal, pre-clinical animal models capable of mimicking the human PI remains a major challenge for its cure. An ideal animal model must endeavour the reproducibility, clinical significance, and most importantly effective translation into clinical use.

Methods

In this current systematic review, a methodological literature review was conducted on the PRISMA guidelines. PubMed/Medline, Research Scholar and Science Direct databases were searched. We conferred the animal models like mice, rats, pigs and dogs used in the PI experiments between January 1980 to January 2021. Typically, methods like Ischemia-reperfusion (IR), monoplegia pressure sore and mechanical non-invasive have been discussed. These were used to generate pressure injuries in small and large animal models.

Results and conclusion

Different animal models (mouse, rat, pig, dog) were evaluated based on ease of handling, availability for research, their size, skin type and the technical skills required. Studies suggest that mice and rats are the best-suited animals as their skin healing by contraction resembles the skin healing in humans. In most of the studies with mice and rats, the time taken for the recovery was between 1 and 3 weeks. Further, various techniques discussed in the current systematics review, supports the statement that the Ischemia-reperfusion (IR) method is the most suited method to study pressure injury. It is a controlled method that can develop different stages of PI and does not require any specialized setup for the application.

Keywords: Pressure injury (PI), Animal model, Rat model, Mouse model, Spinal cord injury (SCI), Systematic review, Pig model

1. Introduction

Pressure injury (PI) is the ulcer of the skin and the connected tissues caused by prolonged pressure, friction and shear on the skin.1 PI is also named as bedsore, pressure ulcer, pressure sore and decubitus ulcer. The most common sites of PI are the underlying regions of skin that cover the bony area like heels, shoulder blades, skin behind knees, ankles, hips and the coccyx. There are mainly four stages of PI (Table 1) of which Stage-I shows the sign of discoloration and change in the temperature and it can be easily managed by just relieving the pressure from the affected area. Skin is intact in Stage I, whereas in Stage IV the injury extends into the muscle and the bone causing severe pain and infection. Surgery is often recommended for this stage. In elderly patients and patients with spinal cord injury (SCI), pressure injury is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality.2,3

Table 1.

Stages of Pressure injury.

| PI stages | Description |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin type | Tissue damage | Treatment | Days of recovery | |

| 1. | Intact | No damage | Treated by removing the pressure | 3 days |

| 2. | Superficial/par tial skin loss | Epidermis and dermis loss | Treated by removing the pressure with a proper bandage | 3 days to 3 weeks |

| 3. | Full-thickness skin loss | Necrosis of subcutaneous tissue | Antibiotic therapy, removal of dead tissue, surgery may be required. | 1–4 months |

| 4. | Full-thickness skin loss | Exposure of muscle and bone | Surgery required | 3 months to 2 years |

Pressure injury persists as a major health challenge affecting approximately 3 million adults.4 More than 60,000 people die every year from complications with PI.5 Patients with PI have nearly 4.5 times higher risk of death as compared to the patients without PI.6 Moreover, secondary complications like wound-related bacteraemia could increase the mortality risk by up to 55%.5,7, 8, 9 Besides morbidity and mortality, socioeconomic factors impact a patient’s health status. It was estimated that the average cost per stay (mean stay = 13 days) for the PI patients is nearly $37,80,0.10 It is of utmost importance to understand the post-injury complications and during-treatment complications of PI. To address this, animal models are considered to be the best option.

Animals are an important part of clinical research, animal models help to understand the etiology and the pathophysiology of diseases. Moreover, it also expedites the development of the new treatment modality. The biggest advantage of using an animal model like a fuzzy rat and mouse is, they are inexpensive, easily available and easy to handle. The use of large animals provides a larger surface area for numerous injuries. Animals such as dogs add to the advantage of having soft-tissue anatomy and a physiology similar to that of humans. Mice and rats have higher hair density which does not reflect the true construction of human skin. Due to the limitation of the skin thickness, only partial-thickness studies were possible and full-thickness pressure injury studies cannot be done. Moreover, their immune and inflammatory responses are significantly different from humans post-injury. The studies performed on dogs11 and pigs12, 13, 14, 15, 16 are expensive and require skilled veterinarians and experts due to which it becomes non-practical for most of the research facilities. Furthermore, the dermis of older and larger animals become considerably thicker than humans. These animals also lack eccrine sweat glands which are present in humans all over the body.

It is a question of debate that which animal model can best mimic the PI model for humans. Through this systematic review we are trying to answer this question by exploring the best possible techniques and the animal model used for the PI study. Many studies suggest that in mammals, like mouse models, wound development and wound healing is similar to humans and it facilitates the understanding of PI causal factors and its healing progress. There are multiple methods to generate PI in animals, which provide us different approaches to understand the problem and to develop therapeutic and pharmacological alternatives to accelerate the healing process.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

The current systematic review compiled and discussed the methods used for generating pressure injury in animals and a list of small and large animal models used for the PI study between January 1980 to January 2021.

2. Method used for systematic review

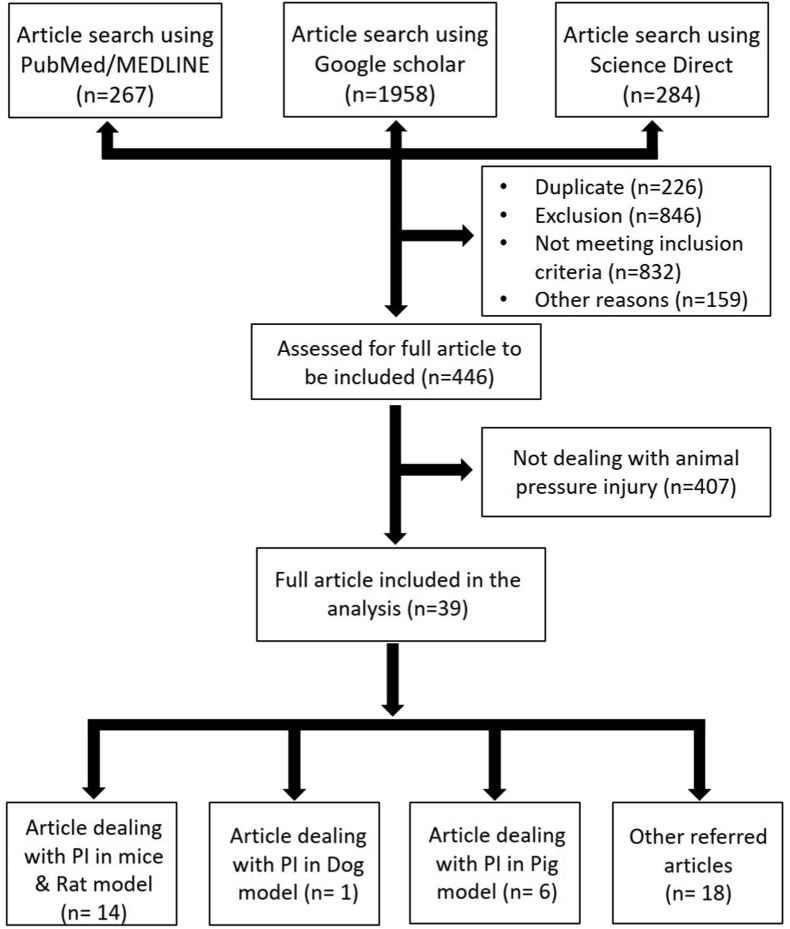

In the current systematic review, PRISMA 2009 guidelines were followed23 (flowchart 1). The PubMed/Medline, Google Scholar and Science Direct search tools were used to seek the research articles related to “pressure ulcer” and “animal model for pressure ulcer”. The term used for the article search was ["pressure ulcer" AND "animal model"]. The selected publication ranges from January 1980–January 2021 because development of animal models started after 1980 and the first model was published in the year 1984.

Flowchart:1.

PRISMA flow diagram used for the systematic review.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) unique ID term used for search were ("Pressure Ulcer/analysis"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/diagnosis"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/epidemiology"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/etiology"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/mortality"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/nursing"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/pathology"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/physiology"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/prevention and control"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/statistics and numerical data"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/surgery"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/therapy"[Mesh] OR "Pressure Ulcer/veterinary"[Mesh]).

3. Inclusion exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria include animal studies related to pressure injury AND pressure ulcer AND pressure sore AND decubitus ulcer. The original studies were included from January 1980 to January 2021. The exclusion criteria for the article were studies not directly related to the pressure injury in the animal model, case reports on humans, articles related to the wound generation other than pressure ulcer, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, clinical trials, randomized controlled trials, books and documents. Other reasons for the elimination of articles include medical blogs and personal opinions.

4. Results and discussion

A total of 2509 publications with full text were found using the search tool. From which 276 articles were found in PubMed, 1958 articles in Google Scholar and 284 articles were obtained in Science Direct. After removing duplicate articles, 39 articles published in the English language satisfying the eligibility criteria and the original articles listed in the databases were included. The primary focus of the review was to discuss the techniques used to develop the experimental animal models for pressure injury.

5. Methodology and instrumentation used for induction of pressure injury

5.1. Ischemia-reperfusion cycle model

Ischemia-reperfusion (IR) is a pathological condition described by an insufficient supply of blood to an organ (Ischemia) causing tissue hypoxia. This is further restored by oxygen supply and reoxygenation which is believed to be associated with inflammatory response.24 IR can be created by two methods:

5.1.1. Magnetic plate

In this type of IR pressure injury model magnetic force is applied to the skin of the mice. Typically, two round ceramic magnetic plates of 2.4 gm having a diameter of 12 mm and thickness of 5.0 mm was applied (Fig. 1a). The two-magnets generate 1000 G magnetic force and lead to 50 mm Hg compressive pressure. Usually, to generate the initial pressure injury formation, three cycles of Ischemia-reperfusion cycles were applied. One cycle consisted of 12 h of Ischemia (magnetic placement) followed by 12 h of reperfusion (release or rest). During the cycle, animals were neither anesthetized nor treated. They were kept free and allowed to take food and water.17,25, 26, 27

Fig. 1.

The collection of images acquired from the original articles shows the various modes of pressure injuries created in the animal model. a. An illustration of the Ischemia pressure injury model using magnetic plates in mice.25b. use of a compression device in mice.18c. schematic diagram of the device used to generate a monoplegia pressure sore model in pig.14d. a pressure sensing system utilized for Ischemia-reperfusion model in pig.30e. pictorial representation of the generation of non-invasive pressure injury model in the rat.29

5.1.2. Compression device

This method uses a modified pressure device. The device was 7 mm × 5 mm in dimension (Fig. 1b) which delivered pressure of 150 mm Hg. Three cycles of 8 h clamping (i.e. compression) and 16 h of no clamping (release) was applied to generate the PI.18

5.2. Monoplegia pressure injury model

As shown in Fig. 1c, the pressure applicator consisted of a cancellous screw (6.5 mm diameter), a plastic disk or indenter disk (3 cm), a spring and a locking collar. To generate the PI, the pressure applicator was placed in the greater trochanter of the animal having muscle atrophy. The screw was percutaneously inserted into the cortex of the proximal femoral shaft. The spring compression produced a pressure of 800 mm Hg on tightening the locking collar. The pressure was applied for 48 h which was enough to generate the full-thickness skin breakdown28 (Fig. 1c).

5.3. Non-invasive pressure injury model in spinal cord of injured mice

The non-invasive method of pressure injury was studied along with the spinal cord injury (SCI) in the rat model by AK Ahmed. In this method, a mid-thoracic (T7-T9) left hemi section was surgically performed on the Sprague-Dawley rat. After seven days of SCI, animals received pressure of varying degrees on the posterior thigh area because of which different stages of pressure injury was generated (Fig. 1e). As documented by the group, 250 mm Hg pressure generated injury of stage I, however, an increase in the pressure up to 500 mm Hg, 750 mm Hg, 1000 mm Hg for 8 h generated the PI of stage II, III, IV respectively.29

5.4. Pressure sensing system

This system is used for the measurement of tissue pressure. Typically, the system consists of a Pressure tank, High resistance capillary potted in epoxy, Transducer, Sending needle, Amplifier, Voltmeter and Chart recorder. In the pressurized tank when the compressed nitrogen is passed, it allows the deionized water to pass from the fluid reservoir having the pressure of 6 lb/in2 to the high-resistance capillary. Water passes through the flexible plastic tubing with a packed sensor (18 cm) and a needle (0.08 cm stainless steel tubing). The sensing system is standardized to generate 0–300 mm Hg pressure using a mercury manometer. The measured pressure is converted to a DC voltage that can be monitored on a digital voltmeter and further recorded on a Gould 220 strip chart recorder30 (Fig. 1d).

In pressure injury research, the trend of animal models use has evolved from a simple ear clip or magnetic beads to a sophisticated computer control system, where the amount of pressure exerted on the animal could be controlled by electronic devices and precise monitoring is achieved. It is of utmost importance to note that experiments on animals related to pressure injury must be performed according to the guidelines of the institutional animal ethical committees. The health and comfort of the animals should be appropriate and, in all conditions, veterinary care should be provided when necessary.31 Most of the studies included in the review has approval of the animal ethics committee of their respective institute except two studies. The study conducted by Hyodo et al.14 and Swaim et al.11 did not report any ethical approval in their study. But they have followed the general principle of laboratory animal care as reported by them.

Some of the basic features of animals like skin type, ease of handling, availability of animal, technical skill, ease of ethical clearance, time required for performing the experiment and the mechanism of healing which are required for defining the suitability of the animal model are described in Table 2. The study of creating a suitable pressure injury model takes us back to 1993 where Swaim SF et al. developed a large animal model using early dermal pressure lesions in Greyhound dogs.11 Later in 1995, Hyodo A. et al. investigated the monoplegia pressure sore model in Hanford minipigs by applying 800 mm Hg pressure for 48 h twice after hind limb damage. They observed uniform natural injury healing and achieved the maximum healing after 20 days.14 Further, cyclic Ischemia-reperfusion model was created in Yorkshire pigs in the year 2000. Houwing R. et al. used a computer-controlled pressure generator and applied pressure of 0–400 N for 2 h. They studied the role of Ischemia and reperfusion in necrosis of the tissues developed by pressure injury.13 Eun-Bin Park in 2021 performed impedance tests and used skin electrical signals to analyse the effects of pressure ulcer-induced areas created by forceps (constant pressure of 140 mmHg). Further, photo biomodulation therapy was used to evaluate the treatment’s effectiveness.32 Many small animal models like mice and rats33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 of different strains were used to investigate other methods of pressure injury generation like compression device,18,39 mechanical non-invasive29 and laminectomy.19 These models have also been studied on various transgenic animals representing specific conditions like diabetes, aging and immunodeficiency. Table 3 summarizes the usage of various types of pressure injury in animal models and the summary of their animal experiment. Each of these transgenic animal models were used to answer a very specific study objective. Further, we could not find any specific study using non-human primates as animal models. It might be due to stringent ethical guidelines and the difficulty in getting ethical approval for use of non-human primates as animal models.

Table 2.

Features of animals used in pressure injury modelling. signs indicate √√√ = Easy, √√ = Moderate, √ = Difficult.

| S.No. | Features | Mouse | Rat | Pig | Dog |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Handling | √√√ | √√√ | √ | √ |

| 2. | Time | √√√ | √√√ | √ | √√ |

| 3. | Availability | √√√ | √√√ | √ | √ |

| 4. | Technical skill required | √√√ | √√√ | √ | √ |

| 5. | Ethical clearance | √√√ | √√√ | √ | √ |

| 6. | Frequently used model | √√√ | √√√ | √√ | √ |

| 7. | Skin type | Loose | Loose | Tight | Tight |

| 8. | Primary healing mechanism | Contraction | Contraction | Re-epithelization, granulation, and contraction | Re-epithelization, granulation, and Contraction |

Table 3.

List of current methods and the type of animals used for the generation of pressure injury model.

| S.No. | Animal model | Strain | Method of PI generation | Year | Summary | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Dog | Greyhound dog | Early dermal pressure lesions with interrupted epidermal continuity | 1993 | Dermal pressure lesion was induced using a short-limb walking cast on one pelvic limb of the dog. The severity of the lesion was managed by the amount of padding and the duration of cast placed on the limb. The severity of the lesion was determined by histopathologic changes, physiological characterization, and dermal thromboxane B2 concentration. |

11 |

| 2. | Pig | Hanford minipigs | Monoplegia pressure sore model | 1995 | The hindlimb was damaged or denervated by bisecting the unilateral nerve roots L1 through S2. Then 800 mmHg pressure was applied on day 5–14 over the trochanteric area for 48 h.

|

14 |

| 3. | Pig | Yorkshire pigs | Ischemia-reperfusion | 2000 | A computer-controlled pneumatic applicator was used to generate a pressure of 0–400 N for up to 2 h in the trochanteric region in pigs. Pre-treatment with 500 mg Vitamin E per day was supplied with the food.

|

13 |

| 4. | Mice | BALB/c | Ischemia-reperfusion cycle model | 2004 | 12 h ischemia-reperfusion cycle (50 mmHg pressure) was employed to create a PI.

|

25 |

| 5. | Mice | SKH1- hr and NOD-LtSz-scid/scid/J (NOD/SCID) | Ischemia magnetic pressure model | 2011 | Localized ischemia was induced by a magnetic force equivalent to 562.2 mm Hg. PI was also induced in diabetes mice (stimulated by streptozotocin) and X-ray irradiated mice. The treatment of PI was achieved by transplantation of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in NOD-LtSz- scid/scid/J (NOD/SCID) mice.

|

17 |

| 6. | Mice | NOD.CB17-Prkdscid/NCrHsd | Compression device model | 2014 | PI was created using a compression device. A pressure of 150 mmHg was applied for 8 h for three-cycle. Further, Human skin was grafted.

|

18 |

| 7. | Mice | C57BL/6 db/db mice (BKS. CG-M+/+Lepr<db>/J | Ischemia-reperfusion cycle model | 2015 | To improve HIF-1α activity, a transdermal drug delivery system was developed to deliver deferoxamine. The diabetic pressure wound model was created by Ischemia-reperfusion.

|

20 |

|

||||||

| 8. | Mice | C57BL/6 | Ischemia-reperfusion cycle model | 2015 | Mice were subjected to a 2 or 3 ischemia-reperfusion cycle. The efficacy of adipose-derived stromal/stem cells of mice origin was checked. Dose-dependent recovery of pressure injury was achieved after adipose- derived stromal/stem cell administration. |

22 |

| 9. | Rat | Sprague-Dawley | Non-invasive model | 2016 | A mid-thoracic left hemisphere (T7-T9) was performed to create SCI. followed by applying a varying degree of pressure on the left posterior thigh region.

|

37 |

| 10. | Mice | Balb/c | Laminectomy & Pressure injury | 2019 | Mice were subjected to laminectomy and complete transaction of (T9-T10 vertebrae) of the spinal cord. Pressure injury was created near the ischemic area with the help of magnet.

|

19 |

| 11. | Mice | C57BL/6 Aging induced by d-galactose (100 mg/kg) injection |

Ischemia-reperfusion | 2019 | PI created on the back of d-galactose-induced aging mice followed by the application of exosomes from a human embryonic stem cell (ESC-Exos).

|

36 |

| 12 | Mice | OKD48 | Ischemia-reperfusion | 2020 | Accessed the effects of administration of Dimethyl fumarate on pressure injury development after cutaneous ischemia-reperfusion cycle.

|

37 |

| 13 | Rat | Sprague Dawley rats (diabetes induced by streptozotocin) | Ischemia magnetic pressure model | 2020 | Pressure injury was created using two magnets (250G magnetic force) in diabetic Sprague Dawley rats. Non-diabetic pressure injury, diabetic pressure injury, and excisional wound was compared

|

38 |

| 14 | Rats | Sprague Dawley rats | Compression device model | 2021 | A pressure of 140 mmHg was applied for 3 h on the back of rats to induce stage-II of pressure injury.

|

32 |

6. Conclusion

All the animal models, either big or small, are an asset for the research community. Each animal model has its significance and limitations according to the experimental objectives. In the current systematic review, we found that among all the animal models used for PI, mice and rats are recognized as suitable models because of their small size, availability, skin type, handling and ease of doing experiments which increases the understanding of the pathophysiology of the injury caused by pressure. However, in the future, advanced studies need to be done in higher animal models like non-human primates which are believed to be the closest ancestor of humans with major physiological and genome similarity.

Author’s contributions

AK, PSN, HSC conceptualized the review. AK and PSN reviewed the literature. AK and PSN wrote the manuscript. HSC reviewed the manuscript and gave the critical inputs. All the authors read the manuscript and agreed on the content.

Consent for publication

Not required.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful to Indian Spinal Injuries Centre, New Delhi for providing us with the resources and facility to carry out this review. We are thankful to Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for project grant no. 2019-3358.

References

- 1.Stojadinovic O., Minkiewicz J., Sawaya A. Deep tissue injury in development of pressure ulcers: a decrease of inflammasome activation and changes in human skin morphology in response to aging and mechanical load. Egles C., editor. PloS One. 2013;8(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamberlain J.D., Meier S., Mader L., Von Groote P.M., Brinkhof M.W.G. E-mail systematic review mortality and longevity after a spinal cord injury: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;44:182–198. doi: 10.1159/000382079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agrawal K., Chauhan N. Pressure ulcers: back to the basics. Indian J Plast Surg. 2012;45(2):244–254. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.101287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The prevalence of dermal ulcers among persons in the U.S. who have died - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2787653/ [PubMed]

- 5.Desforges J.F., Allman R.M. Pressure ulcers among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(13):850–853. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903303201307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Staas W.E., Cioschi H.M. Pressure sores - a multifaceted approach to prevention and treatment. West J Med. 1991;154(5):539–544. /pmc/articles/PMC1002824/?report=abstract. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allman R.M., Walker J.M., Hart M.K., Laprade C.A., Noel L.B., Smith G.R. Air-fluidized beds or conventional therapy for pressure sores. A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(5):641–647. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-5-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pressure ulcers: etiology and prevention - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3554149/ [PubMed]

- 9.Peromet M., Labbe M., Yourassowsky E., Schoutens E. Anaerobic bacteria isolated from decubitus ulcers. Infection. 1973;1(4):205–207. doi: 10.1007/BF01639650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allison Russo C., Elixhauser A. 2003. HCUP Statistical Brief #3: Hospitalizations Related to Pressure Sores.http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/ 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swaim S.F., Bradley D.M., Vaughn D.M., Powers R.D., Hoffman C.E. The greyhound dog as a model for studying pressure ulcers. Decubitis. 1993;6(2):32–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein B., Sanders J. Skin response to repetitive mechanical stress: a new experimental model in pig. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(3):265–272. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houwing R., Overgoor M., Kon M., Jansen G., van Asbeck B.S., Haalboom J.R. Pressure-induced skin lesions in pigs: reperfusion injury and the effects of vitamin E. J Wound Care. 2000;9(1):36–40. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2000.9.1.25939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyodo A., Reger S.I., Negami S., Kambic H., Reyes E.B.E. 13 Evaluation_of_a_Pressure_Sore_Model_Using.25.pdf. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(2):421–428. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199508000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundin B.M., Hussein M.A., Glasofer S. The role of allopurinol and deferoxamine in preventing pressure ulcers in pigs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(4):1408–1421. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200004040-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokate J.Y., Leland K.J., Held A.M. vol. 76. 1995. (Temperature-Modulated Pressure Ulcers: A Porcine Model). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De La Garza-Rodea A.S., Knaän-Shanzer S., Van Bekkum D.W. Pressure ulcers: description of a new model and use of mesenchymal stem cells for repair. Dermatology. 2011;223(3):266–284. doi: 10.1159/000334628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maldonado A.A., Cristóbal L., Martín-López J., Mallén M., García-Honduvilla N., Buján J. A novel model of human skin pressure ulcers in mice. PloS One. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S., Tan Y., Yarmush M.L., Dash B.C., Hsia H.C., Berthiaume F. Mouse model of pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury. JoVE. 2019;2019(145):1–7. doi: 10.3791/58188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duscher D., Neofytou E., Wong V.W. Transdermal deferoxamine prevents pressure-induced diabetic ulcers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(1):94–99. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413445112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hariri A., Chen F., Moore C., Jokerst J.V. Noninvasive staging of pressure ulcers using photoacoustic imaging. Wound Repair Regen. 2019;27(5):488–496. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strong A.L., Bowles A.C., MacCrimmon C.P. Characterization of a murine pressure ulcer model to assess efficacy of adipose-derived stromal cells. Plast Reconstr Surg - Glob Open. 2015;3(3):1–9. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chugh S.S., Reinier K., Teodorescu C. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: clinical and research. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;3(1):3235–3244. doi: 10.1038/nm.2507.Ischemia. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stadler I., Zhang R.Y., Oskoui P., Whittaker M.S., Lanzafame R.J. Development of a simple, noninvasive, clinically relevant model of pressure ulcers in the mouse. J Invest Surg. 2004;17(4):221–227. doi: 10.1080/08941930490472046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reid R.R., Sull A.C., Mogford J.E., Roy N., Mustoe T.A. A novel murine model of cyclical cutaneous ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2004;116(1):172–180. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4804(03)00227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wassermann E., van Griensven M., Gstaltner K., Oehlinger W., Schrei K., Redl H. A chronic pressure ulcer model in the nude mouse. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17(4):480–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evaluation of a pressure sore model using monoplegic Pigs : plastic and reconstructive surgery. https://journals.lww.com/plasreconsurg/abstract/1995/08000/evaluation_of_a_pressure_sore_model_using.25.aspx [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Ahmed A.K., Goodwin C.R., Sarabia-Estrada R. A non-invasive method to produce pressure ulcers of varying severity in a spinal cord-injured rat model. Spinal Cord. 2016;54(12):1096–1104. doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Khanh M. M.Sc, Madsen Berit L.B.A., Barth Phillip W. PhD. 14An_In_Depth_Look_at_Pressure_Sores_Using.1.pdf. Plast Reconstr Surg. Published online. 1984:745–754. Dec 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Retnam L., Chatikavanij P., Kunjara P. Laws, regulations, guidelines and standards for animal care and use for scientific purposes in the countries of Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and India. ILAR J. 2016;57(3):312–323. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilw038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park E Bin, Heo J.C., Kim C., Kim B., Yoon K., Lee J.H. Development of a patch-type sensor for skin using laser irradiation based on tissue impedance for diagnosis and treatment of pressure ulcer. IEEE Access. 2021;9:6277–6285. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3048242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peirce S.M., Skalak T.C., Rodeheaver G.T. Ischemia-reperfusion injury in chronic pressure ulcer formation: a skin model in the rat. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8(1):68–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.2000.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bosboom E.M.H. Deformation as a trigger for pressure sore related muscle damage. 2001. https://research.tue.nl/en/publications/deformation-as-a-trigger-for-pressure-sore-related-muscle-damage-3 Published online.

- 35.Histopathology of pressure ulcers as a result of sequential computer-controlled pressure sessions in a fuzzy rat model - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7889250/ [PubMed]

- 36.Chen B., Sun Y., Zhang J. Human embryonic stem cell-derived exosomes promote pressure ulcer healing in aged mice by rejuvenating senescent endothelial cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1253-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inoue Y., Uchiyama A., Sekiguchi A. Protective effect of dimethyl fumarate for the development of pressure ulcers after cutaneous ischemia-reperfusion injury. Wound Repair Regen. 2020;28(5):600–608. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sami D.G., Abdellatif A. Histological and clinical evaluation of wound healing in pressure ulcers: a novel animal model. J Wound Care. 2020;29(11):632–641. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2020.29.11.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stekelenburg A., Oomens C., Bader D. Press Ulcer Res Curr Futur Perspect; 2005. Compression-induced Tissue Damage: Animal Models; pp. 187–204. Published online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]