Abstract

Financial technology (fintech) is a growing industry in Indonesia, supported by advances in the technological infrastructure. At the end of 2019, the Financial Services Authority (OJK), the financial authority in Indonesia, recorded 164 registered and licensed fintech (P2P lending) companies. However, since early 2018, the Investment Alert Task Force (SWI) and the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology have blocked 1,350 illegal fintech platforms. Illegal fintech lending practices have mechanisms beyond the responsibility and authority of the OJK, including the risk of collection and distribution of personal data. The essence of this study is to discuss the landscape of fintech P2P lending in Indonesia from Indonesian Online News data, explore cases of fintech p2p lending in Indonesia, and understand the rules and policies. Qualitative research with a case study approach and Focus Group Discussion techniques were used to obtain data from 4 stakeholders in the Fintech P2P Lending Industry in Indonesia. VOS Viewer software is used to build keywords from Indonesian Online News collections, NVIVO 12 qualitative software is used to assist data analysis. The research found the keyword clusters most frequently discussed in the Indonesian Online News collection and five case themes such as public awareness about P2P lending (user understanding), data leakage, and restriction of data access, including personal data protection, personal data fraud, illegal fintech lending, and Product marketing ethics.

Keywords: Financial technology, Fintech, P2P lending, Focus Group Discussion, Indonesia

Financial technology; Fintech; P2P lending; Focus group discussion; Indonesia.

1. Introduction

Digital transformation has made an impact on the financial sector (Zavolokina et al., 2016). Technology in the financial sector, commonly known as financial technology (fintech), is now attracting the attention of researchers not only in the fields of economics and business but in the field of computer science, especially information systems (Gai et al., 2018). Fintech has been competing with traditional financial services, offering customer-centric services and using internet technology to make access easier (Gomber et al., 2017). Currently, fintech business models address funding, payments, wealth management, capital markets, and insurance services (Lee and Shin, 2018). The online lending platform (OLP) fintech industry is growing rapidly, especially in Indonesia (OJK, 2019b). Indonesia is a country with a very high development of the fintech industry (after China) because fintech originated to facilitate more loans to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) across the archipelago (Davis et al., 2017). Although Indonesia has several challenges, such as geography and infrastructure development, regulators have faced additional problems such as moral hazard, platform viability, and borrower eligibility (Suryono et al., 2019b).

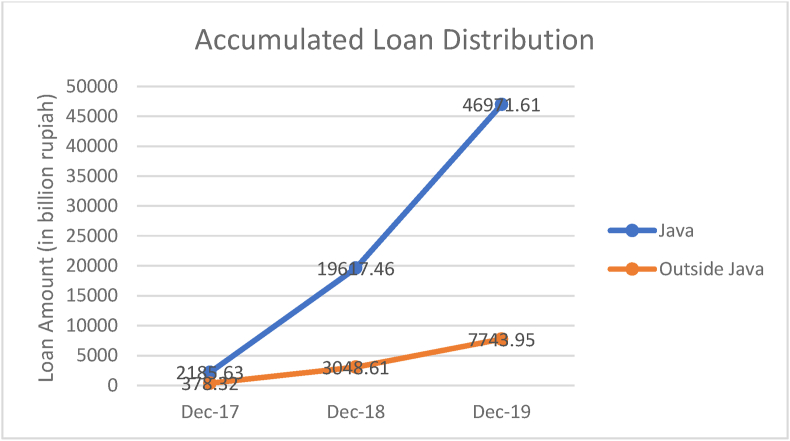

Online lending, or peer to peer (P2P) lending, is a practice of funding unrelated individuals (‘partners’) without going through commercial banks. P2P lending is carried out online through various loan platforms and self-developed credit checking tools for P2P lending companies (Wang et al., 2015). At the end of 2019, the Financial Services Authority (OJK), the financial authority in Indonesia, recorded 164 registered and licensed fintech (P2P lending) companies. However, since early 2018 until now, the Investment Alert Task Force (SWI) and Kemenkominfo (the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, also known as the Ministry of ICT) have blocked 1,350 illegal fintech platforms (OJK, 2019a). Nearly ten times as many fintech platforms attempt to operate outside regulations as operate legally in Indonesia. OJK is an independent institution tasked with regulating and supervising financial services, including fintech practices (OJK, 2016). Based on the OJK report, the accumulated amount of fintech loans in Indonesia in December 2019 reached 54.72 trillion rupiah and increased by 166.51% (OJK, 2019b) (see Figure 1). In September 2019, the number of lender accounts had reached 558,766 entities, an increase of 169.28% from 2017 (OJK, 2019b). According to Pohan et al., this growth occurred because users of Indonesian P2P lending applications appreciated the speed of requests approved as an alternative to traditional funding (Pohan et al., 2019). However, Suryono et al. explained in their systematic literature review that there are six core problems in P2P lending, namely information asymmetry, determination of borrower credit scores, moral hazard, investment decisions, platform feasibility and immature regulations and policies for the protection of personal data (Suryono et al., 2019b). For this reason, each stakeholder (OJK, SWI, Kemenkominfo, and Fintech Association) is expected to immediately agree to the fintech lending industry code of ethics (Pryanka, 2018). P2P lending practices in Indonesia are regulated in the law on Fintech Lending Operators under the Financial Services Authority Regulation (POJK) 77/POJK.01/2016 (OJK, 2016). Based on these rules, registered and licensed fintech practices must meet several criteria such as regulations in supervision, interest and fines, compliance with regulations, billing processes, joining an association, loan conditions, customer complaint services available, and restrictions on access to personal data (OJK, 2018b).

Figure 1.

The accumulated amount of fintech lending in Indonesia (OJK, 2019b).

In the financial services industry, especially regarding digital transformation in this sector, it is necessary to make adjustments to regulations and policies because of the fast pace of technological innovation that cannot leave behind these regulations (Suryono et al., 2020). Even though it has been written in a statutory law or government decree, stakeholders such as the Financial Services Authority, the Investment Alert Task Force, the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology must manage and provide space for sector growth. Unfortunately, the number of illegal p2p lending fintech continues to grow. Therefore, the government's role in providing education to the public is urgently needed to reduce shadow banking risk (Barberis and Arner, 2016).

This research is qualitative research with a case study approach and a Focus Group Discussion technique to obtain data from 4 stakeholders in the Fintech P2P Lending Industry in Indonesia. VOS Viewer software is used to build keywords from Indonesian Online News collections, NVIVO 12 qualitative software is used to assist data analysis.

2. Literature review

Peer-to-peer (P2P) lending is a field of study in various financial technology researches, but studies on this topic are developing. P2P Lending is a new business model that brings together borrowers and lenders on a single platform (Suryono et al., 2020). P2P Lending is operated digitally through a platform with demand requests which the investment committee evaluates before the investment is made (Pişkin and Kuş, 2019). As a two-sided e-commerce phenomenon, P2P Lending has received attention in risk control. Includes the ability to accurately assess and screen borrowers in controlling credit risk (Liu et al., 2019b). Various methods are used to determine credit risks, such as using data mining (Cai and Zhang, 2020), extraction of textual features from the borrower's description (Zhang et al., 2020), and Big Data based on neural networks (Guo, 2020). Other studies have been conducted to avoid prediction errors in the P2P Lending business. Fu et al. (2020) proposes a two-step method that uses deep learning neural networks. Extracting keywords from investor comments and then using a two-way short-term memory-based model (BiLSTM) to predict platform default risk.

In addition to focusing on credit risk control, there are several business processes in P2P Lending, such as the borrower registration process, the credit risk assessment process, the disbursement process, the collection process, the refund or payment process, and the investment process by lenders (Suryono et al., 2019b). Interestingly, current research focuses not only on credit risk assessment but also on how investors, in this case, lenders, evaluate borrowers by including demographic characteristics (Chen et al., 2020). Using more than 178,000 loan lists in China, Ding et al. (2019) found that lenders consider the borrower's reputation as the primary signal in P2P lending transaction decisions. Recently, there has been researching investigate that political and financial forces play an essential role in determining the failure of P2P lending platforms. Platform failure occurs because it ends up going bankrupt or the platform owner runs off with investors' money (He and Li, 2021).

P2P markets first emerged in developed countries with more efficient financial sectors, mature credit core systems, and more effective law enforcement than emerging markets (Jiang et al., 2018). In Indonesia, the solution to meet people's needs for financial services is to use P2P Lending services. The presence of Fintech lending is a result of decreased public trust in the formal financial system (Abubakar and Handayani, 2018). Credit for the banking industry can only be undisturbed if banks are too selective in channeling credit (only to reduce Non-Performing Loans) (Siek and Sutanto, 2019). The global financial crisis followed by an authorization response that tightened the regulatory regime for financial institutions resulted in gaps in financing (Syamil et al., 2020). In Indonesia, Fintech can be divided into Fintech 2.0, namely the development of Fintech by the financial services industry, including banking, capital markets, and the non-bank financial industry. Meanwhile, Fintech 3.0 is a Fintech developed by startup companies (Yunus, 2019).

Before 2016, Indonesia did not yet have a law regulating Fintech activities, so it was feared that it could harm the public due to potential problems (Suryono et al., 2019b). For this reason, in early 2016, OJK has regulated P2P Lending in OJK regulation number 77. The Financial Services Authority has also begun to establish a Fintech Lending Directorate to build a licensing system in this sector. For example, Amartha P2P Lending is one of the platforms that has obtained OJK permission. Lenders can provide loans starting from IDR 3 million (222 USD) to women entrepreneurs in rural areas, anytime, anywhere, and make a profit (Saputra et al., 2019).

On the other hand, the initial hope for the emergence of the P2P Lending platform was to provide funding for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). There are alternative payment schemes in the form of sharia-based loans and profit-sharing plans (Hudaefi, 2020). The loan process, loan costs, interest, loan amount, and loan flexibility affect SMEs to get loan funds (Rosavina et al., 2019). However, gaps exist where the research results by Kohardinata et al. (2020) show that P2P lending growth in Indonesia does not significantly affect bank credit growth. This happens because the platform enters the competition through a less attractive market to the public. After all, it is still in the process of developing product and service quality (Kohardinata et al., 2020). Several adoption models emerged and saw that the perceived benefits were an important and significant factor affecting adoption. Adoption is also influenced by feature innovation, application functionality, and creating a user-friendly platform (Kurniawan, 2019). Variables Performance Expectancy, Social Influence, and Effort Expectancy can influence behavioral intention using a P2P lending platform (Wang et al., 2019). Apart from being viewed from the adoption side, the fintech lending model has begun to develop into funding in various aspects of daily life, such as tourism travel and another long and short-term financing (Suryono et al., 2019a). To that end, measurements of the System Usability Scale (SUS), User Interface Satisfaction Questionnaires (QUIS), and Retrospective Think Aloud (RTA) of the p2p lending application have been measured (Nugraha et al., 2019).

Along with the benefits obtained from the practice of Fintech, it was recorded that 1330 people reported to the Legal Aid Institute (LBH) because 89 P2P lending applications were suspected of violating the law and human rights (Hidayat et al., 2020). User data is often misused by the loan service company (Irawan, 2020). The ineffectiveness of implementing the p2p lending regulation, especially in Indonesia, is influenced by substance norms that have not regulated the amount of interest and the collection mechanism (Njatrijani and Prananda, 2020).

Let's look at the development of p2p lending in several countries. Platforms such as Zopa (from the UK), Prosper.com and LendingClub (from the US), PPDai (from China) are the fastest-growing p2p lending platforms (Herrero-Lopez, 2009) (Yang, 2014) (Gomber et al., 2017). US banks report LendingClub has more than $ 50 billion (Jagtiani and Lemieux, 2018). Meanwhile, Prosper.com attracted more than 1 million members and facilitated more than 32 thousand loans totaling more than $ 193 million. On the other hand, PPDai has attracted 500 thousand members and is the largest platform in China (Chen et al., 2014). However, China's p2p lending market has complaints about unreliable individual credit information. Borrowers tend to take advantage of credibility to seek bigger loans rather than lower borrowing costs (Feng et al., 2015). On the other hand, Yunus (2019) argued that Singapore's p2p lending platform is more transparent than Indonesia. For this reason, it is necessary to have a portfolio of funding techniques and practices as well as risk mitigation that supports financial flows (Usanti et al., 2020).

3. Methodology

We conducted preliminary research to capture the early phenomena. We conducted two text mining experiments to see users' sentiment of the P2P Lending platform in Indonesia. First, from the google playstore review data, we conducted a sentiment analysis of the p2p lending platform (Pohan et al., 2019). Taking five sample applications and testing with text classification techniques, we found four out of five applications had negative sentiment. Most of the negative reviews commented on the slow transfer or approval of funds, collecting debt, and the difficulty of registering. In the second experiment, we looked at the sentiment on Indonesian Online News on the topic of P2P lending (Suryono and Budi, 2019). From 1100 news articles, we found that the number of articles with positive values was more than those with negative values. Technically, this is possible because the news article has gone through the editing process. Several text classification algorithms and feature extraction were also carried out in this experiment to determine the classifier model's best accuracy.

Furthermore, we tried to utilize raw data from P2P lending news articles from national online news portals such as Tribunnews.com, Detik.com, Okezone.com, Sindonews.com, Kompas.com, Liputan6.com, Merdeka.com, Cnnindonesia.com, Tempo.co, and Business. com. The reason for choosing this portal is that it is the most visited news site (based on the Alexa index). The portal has been registered with Dewanpers (the body that oversees the Journalistic Code of Ethics in Indonesia). We process the text data using the VOS Viewer tool to perform content analysis. The goal is to get keywords and as a starting point for understanding P2P lending from various perspectives. This is also a process of observing the issues to be raised.

During one year of field observations, this research used a qualitative approach to capture the landscape of fintech practices in Indonesia. Qualitative research techniques can be more suitable for asking what the Fintech P2P Lending issue in Indonesia is and how stakeholders address it. The qualitative research procedures usually begin with a literature review, purposive sampling, data collection, and results analysis. The data collection design in this study is a Focus Group Discussion (FGD), hoping that it can provide convenience for openness and sharing of experiences. In simple terms, this systematic and directed discussion will discuss:

-

1.

Issues, cases, and problems of the P2P lending platform in Indonesia.

-

2.

Roles and responsibilities.

-

3.

The supervision process that has been carried out.

We chose a single case study approach to question current phenomena that researchers are exploring in real life. Respondents in this study were selected purposively based on regulators or official supervisors of the P2P Lending industry. Focus Group Discussion was conducted online through the teleconference application in September 2020. Focus Group Discussion participants included Deputy Director of Fintech Regulation, Licensing and Supervision of the Financial Services Authority (OJK), Head of the Subdirectorate of Electronic Certification Organizing Control of the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, Chair of the Investment Alert Task Force (SWI), Deputy Chair of the Fintech Association in Indonesia (AFPI), and Senior Lecturers as academic representatives. We chose these sources because each source has experience in regulating and understanding the landscape of the Fintech P2P lending industry in Indonesia.

The NVIVO 12 qualitative analysis software was used to facilitate FGD analysis. FGD recorded data were transcribed to a pdf extension before the examination. Unlike the interview process, the FGD aims to obtain conclusions and agreement on a specific problem or case. Therefore, this choice can be justified for the research just because our focus is on the issue, role, and supervision process in Indonesia.

In practice, we have obtained ethical approval through research lab committee in faculty. This research project also contributes to the Financial Services Authority (Directorate of Fintech Regulation, Licensing and Supervision), the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (Sub-Directorate of Electronic Certification Operations Control), the Investment Alert Task Force (SWI), and the Fintech Association in Indonesia (AFPI).

3.1. Justification of choosing Indonesia

In the development process, Indonesia has the challenge to develop a financial system and financial services innovatively. This innovation also affects the growth of SMEs in Indonesia. SMEs have difficulties in financing venture capital. SMEs face problems in lending capital funds due to distance problems, collateral requirements, and the need for a formal bank account. For this reason, Fintech has begun to develop in Indonesia to help overcome this problem (Davis et al., 2017). Indeed, inequality is a crucial problem in Indonesia's infrastructure development because of the 52 million digital infrastructure users, most of whom are on the island of Java, around 18 million users (Iman, 2018).

The development of Fintech P2P lending in Indonesia is quite fast. Before the Financial Services Authority claimed to be the regulator that comprehensively regulates technology-based lending and borrowing service transactions, P2P lending platforms began to emerge in 2016 (Rosavina et al., 2019). OJK noted that there were 153 P2P Lending platforms as of November 2020. With total assets of Rp. 3.57 trillion (up 18.85% from year to year) (OJK, 2020b). However, along with P2P Lending platforms' growth registered with the OJK, the Investment Alert Task Force has also found thousands of illegal platforms that have emerged from year to year (Suryono et al., 2020). For this reason, the Indonesian state was chosen to investigate this phenomenon to implement Fintech P2P lending practices following applicable policy rules and under the supervision of regulators.

4. Findings and discussion

In this section, we describe our findings in two ways. First, the content analysis results on online news text data in Indonesia aims to identify keywords that often appear and classify meaningful statements. Second, we analyzed the P2P lending problems presented in the Focus Group Discussion and grouped them into five major themes discussed in the discussion section. Furthermore, in the discussion section, we capture the agreement's results to identify P2P lending problems in Indonesia.

4.1. Findings

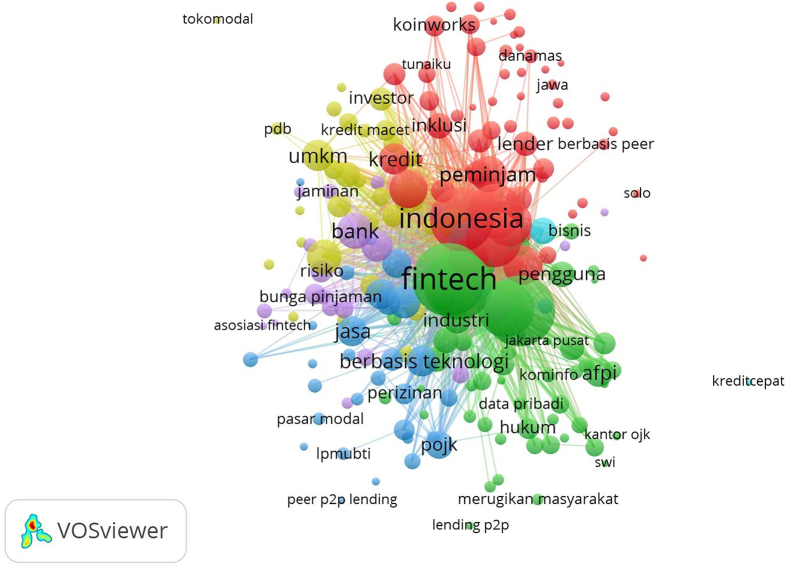

We perform content analysis with the VOS Viewer tool. We used data preprocessing to clean the text data from 1100 online news articles obtained. After that, we processed the data with VOS Viewer. We divided 55,499 terms into 733 clusters to meet the threshold. We used the clustering method to determine the closeness or relationship between data and form themes. The association technique was also used to draw relationships between variables such as those found in data warehouses. Figure 2 displays the pattern of processed data.

Figure 2.

The patterns of online news content analysis.

After obtaining the content analysis pattern, we looked at the results of the item clustering and picked the appropriate keywords for discussion. The VOS Viewer application automatically divides keywords into five clusters. Table 1 displays the keyword analysis results. After obtaining keywords, we classify important keywords into five domains.

Table 1.

Content analysis results.

| Clusters | Keywords | Meaningful Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Indonesia, Pinjaman, p2p, lending, p2p lending, perusahaan, teknologi, peminjam, kredit, pemberi pinjaman, inklusi, online, lender, cepat, peer lending, modalku, borrower, koinworks, loan, amartha, investree, Syariah, ukm, perusahaan financial technology, tekfin, danamas, pulau jawa, akseleran, fintech Indonesia, penyaluran pinjaman, bali, bandung, pt investree radhika jaya, berbasis peer, pt amartha mikro fintek, mitra, jawa, jumlah pinjaman, uangteman, danain, Surabaya, calon peminjam, semarang, dompet kilat, perkembangan teknologi, jawa barat, jabodetabek, tunaiku, industri financial technology, rupiahplus, solo, akulaku, crowdo, finmas, kredivo, nilai pinjaman, medan, perusahaan terdaftar, kreditcepat (Indonesia, loan, p2p, lending, p2p lending, company, technology, borrower, credit, lender, inclusion, online, lender, fast, peer lending, modalku, borrower, koinworks, loan, amartha, investree, sharia, ukm, company financial technology, fintech, danamas, java island, akseleran, Indonesian fintech, loan distribution, bali, bandung, pt investree radhika jaya, peer-based, pt amartha micro fintek, partners, java, loan amount, friends, funds, Surabaya, prospective borrowers, semarang, flash wallet, technology development, west java, jabodetabek, tunaiku, financial technology industry, rupiahplus, solo, akulaku, crowdo, finmas, credivo, loan value, medan, registered company, credit fast) | Platform: Modalku, KoinWorks, Amartha, Investree, Danamas, UangTeman, Danain, Dompet Kilat, Tunaiku, RupiahPlus, Akulaku, Crowdo, Finmas, KreditCepat |

| 2 | Fintech, Ojk, Jakarta, otoritas jasa keuangan, afpi, industry, pengguna, fintech p2p lending, nasabah, pinjaman online, transaksi, konsuman, fintech lending, asosiasi fintech pendanaan bersama Indonesia, hukum, satgas waspada investasi, bank Indonesia, izin, tidak terdaftar, berizin, regulator, lembaga bantuan hukum, telah terdaftar, kementerian komunikasi dan informatika, bisnis, reporter, pengawasan, transparasi, masalah, kominfo, lending yang terdaftar, fintech pendanaan bersama Indonesia, fintech p2p, layanan pinjam meminjam, data pribadi, asosiasi, merugikan masyarakat, pengaduan, aduan, fintech pinjaman, denda, jakarta selatan, fintech yang terdaftar, kantor ojk, customer, kemenkominfo, bila, kemkominfo, tentang inovasi keuangan digital, jakarta pusat, lending p2p, perusahaan fintech p2p lending, direktur pengaturan perizinan dan pengawasan fintech otoritas jasa keuangan, swi (Fintech, Ojk, Jakarta, financial services authority, afpi, industry, users, fintech p2p lending, customers, online loans, transactions, consumer, fintech lending, Indonesian joint funding fintech association, law, investment alert task force, Indonesian bank, permits, no registered, licensed, regulator, legal aid agency, registered, ministry of communication and information technology, business, reporter, supervision, transparency, issue, communication and information technology, registered lending, Indonesian joint funding fintech, p2p fintech, lending and borrowing services, personal data, association, detrimental to the public, complaints, complaints, fintech loans, fines, south jakarta, registered fintech, ojk offices, customers, ministry of communication and information technology, if, kemkominfo, about digital financial innovation, central jakarta, p2p lending, p2p lending fintech company, director of licensing arrangements and the financial services authority's fintech oversight, swi) | Stakeholders: OJK, Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (Financial Services Authority), SWI, Satgas Waspada Investasi (Investment Alert Task Force), Bank Indonesia, Lembaga Bantuan Hukum (Legal aid), KEMENKOMINFO, kementerian komunikasi dan informatika (Ministry of Communication and Informatics), Fintech Association (AFPI, AFSI, AFTECH), and Costumer. Issues: License, not registered, monitoring, transparency, detrimental to society, complaint, late charge, regulation. |

| 3 | keuangan, perusahaan fintech, jasa, berbasis teknologi, layanan, pojk, lembaga, regulasi, perizinan, tentang layanan pinjam meminjam uang berbasis teknologi informasi, sistem, peraturan ojk, industri fintech, manajeman, peraturan otoritas jasa keuangan, perlindungan konsuman, financial technology fintech, debitur, layanan jasa, industri jasa, lpmubti, payment, pasar modal, pinjam meminjam uang, terorisme, sistem pembayaran, perusahaan pembiayaan, sektor layanan pinjam meminjam uang berbasis teknologi, penjaminan, sistem keuangan, peer p2p lending (finance, fintech companies, services, technology-based, services, pojk, institutions, regulation, licensing, information technology-based lending and borrowing services, systems, ojk regulations, fintech industry, management, financial services authority regulations, consumer protection, financial technology fintech, debtors, services, service industry, lpmubti, payment, capital markets, lending and borrowing, terrorism, payment systems, finance companies, technology-based lending and borrowing services sector, underwriting, financial system, peer p2p lending) | Definitions: information technology-based lending and borrowing services Regulations and Policies: POJK and Consumer Protection Issues: terrorism, service, funding, payment system |

| 4 | perbankan, dana, umkm, investasi, pembiayaan, berkembang, investor, produk, pasar, ekonomi, mudah, sektor, usaha mikro, dunia, agunan, pemerintah, china, gagal bayar, singapura, malaysia, kredit macet, internet, saham, pdb, perusahaan rintisan, amerika serikat, mudah dan cepat, lebih cepat, startup fintech, tokomodal (banking, fund, umm, investment, financing, developing, investor, product, market, economy, easy, sector, microbusiness, world, collateral, government, china, default, Singapore, malaysia, bad credit, internet, stocks, pdb, startup, united states, fast and easy, faster, fintech startup, tokomodal) | Issues: failed to pay, bad credit, collateral, easy to use, faster |

| 5 | bank, bunga, uang, risiko, aftech, pinjam meminjam, pembayaran, asosiasi fintech indonesia, perusahaan teknologi, pinjam, jaminan, bunga pinjaman, rentenir, finance, jangka, wimboh santoso, bunganya, bunga tinggi, economics, ktp, asosiasi fintech, artificial intelligence, day loan, sdm (bank, interest, money, risk, aftech, lending and borrowing, payment, indonesian fintech association, technology company, borrow, guarantee, loan interest, loan shark, finance, term, wimboh santoso, interest, high interest rate, economics, ktp, fintech association, artificial intelligence, day loan, sdm) | Issues: loan interest, loan shark, personal identification, artificial intelligence |

The results of the content analysis show that:

-

1.

Definition: P2P lending is an information technology-based lending service.

-

2.

Stakeholders: the Financial Services Authority is the regulator that makes policies, the Investment Alert Task Force (Handling of Alleged Unlawful Actions regarding Community Fund Collection and Investment Management) in the Ministry of ICT regulates the implementation of electronic systems and transactions (has the right to block illegal websites and applications), and the Indonesian Joint Funding Fintech Association (AFPI), which is the official association of information technology-based lending and borrowing service providers in Indonesia.

-

3.

Regulations and policies: POJK Number 77/POJK.01/2016 concerning P2P Lending, Government Regulation (PP) Number 71 of 2019 concerning Implementation of Electronic Systems and Transactions, Minister of ICT Regulation Number 20 of 2016 regarding Personal Data Protection in Electronic Systems.

-

4.

Platform: Modalku, KoinWorks, Amartha, Investree, Danamas, UangTeman, Danain, Dompet Kilat, Tunaiku, RupiahPlus, Akulaku, Crowdo, Finmas, KreditCepat. The report of Registered and Licensed Fintech Lending Operators at OJK contains a list of legal platforms.1

-

5.

Issues: problems (terrorism, failed to pay, bad credit, collateral, loan interest, loan shark, personal identification) and advantages (easy to use, faster, service, funding, payment system, artificial intelligence).

4.1.1. Focus group discussion results

Data collection methods in information systems research are very diverse. Focus group discussion (FGD) is one of the most frequently used data collection methods in a qualitative approach, especially Information systems research. Information systems research includes multidisciplinary research that explores problems in social conditions and cannot be separated from technology, processes, and people, including behavior.

The FGD participants in this study were the Head of the Investment Alert Task Force, the Director of Fintech Licensing and Supervision Arrangements (Financial Services Authority), the Head of the Sub-Directorate for Electronic Certification Organizers Control (Ministry of ICT), the Deputy Chairperson of the AFPI and several academics.

Based on the results of the FGD, we found problems, cases and problems with the P2P lending platform in Indonesia. We divided the discussion into five major themes, including:

-

1.

Public awareness about P2P lending (user understanding)

-

2.

Data leakage and restriction of data access, including personal data protection

-

3.

Personal data fraud

-

4.

Illegal fintech lending

-

5.

Product marketing ethics

4.2. Discussions

The following is the result of a discussion about P2P lending issues in Indonesia.

4.2.1. Public awareness about P2P lending

P2P lending is an innovation that helps the majority of the poor, who are often unbanked and unbankable. The definition of unbankable is a group of people who do not have access to conventional banking products due to constraints on information, qualifications, or the absence of bank facilities in their environment. However, this condition also affects people's understanding of the P2P lending platform. Borrowers are not wise about borrowing and may borrow on many platforms without considering the ability to pay. The borrower does not pay attention to the terms and conditions when processing loans. On the other hand, lenders don't understand the consequences (credit risk), so they blame the P2P loan platform. In addition, the level of app usage by users is not clearly measured due to the diversity of sites or application designs.

4.2.2. Data leakage and restriction of data access, including personal data protection

Protection of personal data is part of personal rights (privacy rights). Personal data is data about a person collected through either electronic or non-electronic systems. Government Regulation Number 71 of 2019 has been found regarding the protection of personal data in the operation of electronic systems and transactions. The regulation explains that the use of information relating to a person's personal data via social media must obtain the consent of the person concerned. These rights include the right to enjoy a private life, free from interference, the right to communicate, and the right to access information.

4.2.3. Personal data fraud

P2P lending platforms claim to connect investors with borrowers via the internet, allowing lenders to generate income while offering credit to many people who cannot obtain bank loans. However, due to increasingly sophisticated technology, these platforms have triggered moral hazards. Some people use other people's data to make loans on P2P lending platforms. Something similar happened in China; the Chinese government is increasing supervision and drafting new measures and regulations for the online lending sector.

Currently, the P2P lending association in Indonesia guarantees the protection of lender funds focusing on fraud risk and credit risk. Lenders expect to feel safe and comfortable. A software program performs the loan feasibility analysis. The platform organizer collaborates with a data provider institution (Fintech Data Center by AFPI).

4.2.4. Illegal fintech lending

The Investment Alert Task Force (SWI) discovered 126 illegal peer-to-peer lending (illegal fintech) entities, 32 investment entities and 50 pawn companies operating without a license by the end of September 2020. More than 2,500 sites and platforms have been blocked by the Investment Alert Task Force (SWI). This task force is a collaboration between the Financial Services Authority (OJK), the Ministry of Trade, the Ministry of ICT, the Ministry of Cooperatives and SMEs, the Attorney General's Office, the Indonesian National police, and the Capital Investment Coordinating Board. Loans from illegal fintech lenders always charge high interest rates. However, the loan period is short and requires access to all contact data on a cell phone, which is used to intimidate the borrower when collecting. All findings of the task force have been submitted to the Ministry of ICT so they can block access on the internet sites and mobile apps of the illegal entities.

4.2.5. Product marketing ethics

The AFPI explained that offering online loans via short message service (SMS) is a practice of illegal platforms that are not registered with the OJK. Victims affected by illegal loans are usually people who do not have strong financial literacy. In addition, the pandemic changed the behavior of people who are trying to start using digital technology in their transaction activities. Good financial literacy will greatly help reduce losses and community anxiety about the rampant offers of illegal loans via SMS. Financial awareness is already happening in Indonesia. The public is advised to avoid prohibited P2P lending services offered through dubious media, such as SMS, direct message (DM) on social media, and other personal means of personal communication and unofficial internet sites.

5. The relationship between the findings and P2P lending practices

5.1. Definitions of fintech P2P lending

Based on a literature study, we try to draw a conclusion about the terminology of fintech P2P lending. Fintech-type P2P lending is a practice of lending and borrowing funds without a bank institution as an intermediary (Yunus, 2019). P2P lending is an online loan platform that links lenders and individual borrowers and offers microcredit (Suryono et al., 2019a). This innovation is a solution that helps micro, small and medium enterprises gain access to capital (Abubakar and Handayani, 2018). According to the OJK regulatory documents, an Online Loan Platform is a financial service provider connected to an internet network where the platform brings together lenders and loan recipients through an electronic system (OJK, 2016). So, P2P lending is a technology that combines the internet and financial services for lending and borrowing (Suryono et al., 2019b).

5.2. Stakeholders (Indonesia context)

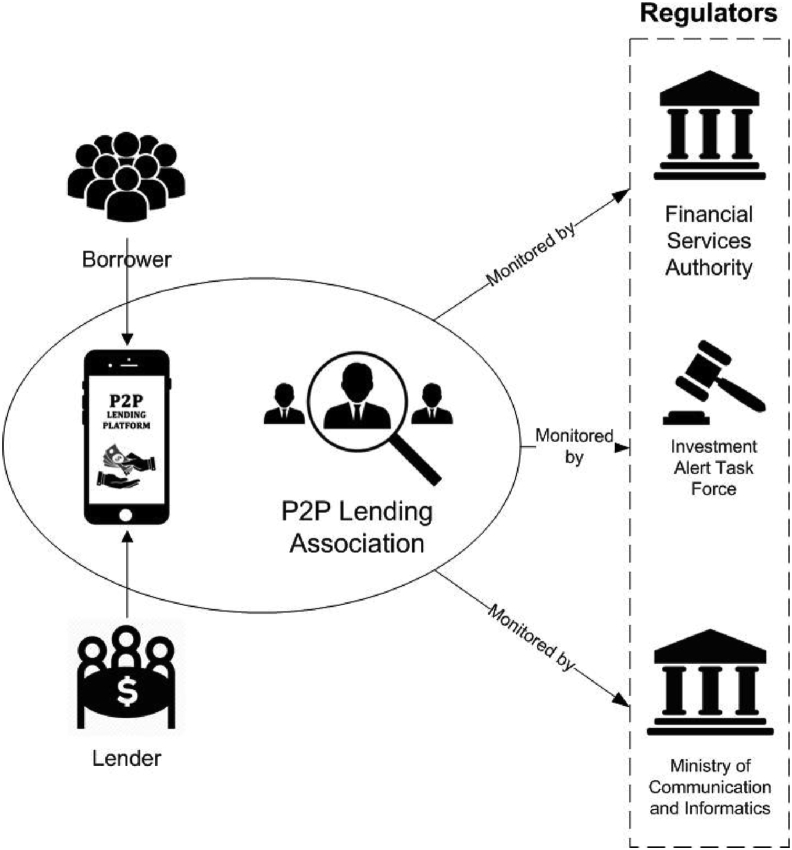

We try to portray a rich picture of the fintech P2P lending platform in Indonesia. Figure 3 describes the players in this industry.

Figure 3.

Stakeholders of fintech P2P lending in Indonesia.

Stakeholder roles are described in detail as follows: The AFPI, as a peer-to-peer lending focus association, has created a consumer protection framework which consists of a code of conduct, ethics committee and consumer complaint line, all of which are AFPI's tools in carrying out their role as a self-regulating organization.

Next is the Financial Services Authority, commonly known as OJK2. OJK was formed based on Law Number 21 of 2011, which functions to organize an integrated regulatory and supervisory system for all activities in the financial services sector. OJK has a Fintech Regulatory, Research and Development Directorate that particularly focuses on funding and investment. OJK's efforts to protect consumers are carried out through the P2PL industry regulation, P2PL industrial supervision, community education activities, and resolution of consumer complaints. In this case, the OJK has developed a regulatory sandbox (a testing mechanism to assess the reliability of business processes, business models, financial instruments and governance of providers) (Duff, 2017). Regulatory sandboxes, or RegLabs, are containers for small-scale testing of newly monitored fintech products and models (Dias, 2017).

More than fifteen financial service authorities around the world have their own RegLab concepts. Canada's Ontario Securities Commission has adopted an approach that offers hands-on testing before obtaining a financial services license. Australia provided an opportunity for the companies in the financial services industry to start a practice for up to one year without a license, under monitored progress. In Indonesia, the Financial Services Authority requires platforms to register and allows up to one year to apply for a full license. In Singapore, the sandbox process was carried out as a step to obtain clear guidance regarding fintech infrastructure and operational guidance. Thailand's SEC launched a “vertical” regulatory sandbox as an investment advisory and financial services and e-commerce platform (Duff, 2017) (Cope et al., 2018). Finally, the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) also monitors the temporary process to observe the administration of the fintech platform's business activities (Huang, 2018).

Different from other countries, Indonesia has its own regulator to take action against illegal fintech. The Investment Alert Task Force (SWI), which consists of several stakeholders, was formed based on the Decree of the OJK Commissioner Number: 01/KDK.01/2016 dated January 1, 2016. The Investment Alert Task Force is the result of the cooperation of several related agencies, which include regulators (Financial Services Authority, Ministry of Trade, the Coordinating Board, Investment, Ministry of Cooperatives and Small and Medium Enterprises of the Republic of Indonesia, Ministry of ICT) and law enforcement (including the Attorney General's Office and the Indonesian National police). SWI has two tasks, preventing and dealing with suspected illegal acts in the field of raising investment funds (Davis et al., 2017).

Finally, the Ministry of ICT is concerned with P2P lending. In accordance with Law Number 39 of 2008 concerning State Ministries, the Ministry of ICT is an apparatus of the government of the Republic of Indonesia which carries out affairs whose scope is regulated in the 1945 Law, namely information and communication. For fintech P2P lending, this ministry supervises compliance with Government Regulation Number 71 of 2019 concerning the Implementation of Electronic Systems. This law states that all platforms must comply with these regulations in the electronic system registration process, including electronic transactions. This ministry issued ministerial regulation number 20 of 2016 regarding the protection of personal data. If the P2P lending platform does not comply with the regulations, then the Ministry of ICT has the right to block the platform.

5.3. Regulations and policies in Indonesia

This section discusses the laws governing the implementation of fintech P2P lending in Indonesia (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of policies, laws and regulations in Indonesia.

| Document | Explanation |

|---|---|

| POJK Number 77 of 2016 concerning P2P Lending (OJK, 2016) | The Operator provides, manages, and operates ICT-Based lending and Borrowing Services, whose funds come from investors (lenders). Organizers are required to register their platform to obtain a license from the OJK. |

| Indonesian Government Regulation Number 71 of 2019 concerning Implementation of Electronic Systems and Transactions (Ministry of Communication and Informatics, 2019) | Electronic System Operator having a portal, website or application in the network through the internet has the obligation to register its platform. Electronic System Operators shall be conducted before Electronic Systems begin to be used by Electronic System Users. |

| Minister of ICT Regulation Number 20 of 2016 concerning Personal Data Protection in Electronic Systems (Ministry of Communication and Informatics, 2016) | Personal Data Protection is protection against the collection, processing, analysis, storage, display, announcement, transmission, dissemination and destruction of Personal Data. |

The Financial Services Authority has regulated the risk prevention of high-interest rates and the risk of default and improper collection methods. For this reason, the POJK regulation Number 77/POJK.07/2016 has written the rules regarding the platform requirements as an operator. Starting from the registration process and assist with the new platform, known as a regulatory sandbox. The OJK has regulated the risk prevention of P2P Lending in some provisions contained in the POJK P2P Lending. Including in the provisions of Article 29 namely, the Administrator must apply the basic principles of user protection, including transparency, fair treatment, reliability, data confidentiality, simple user dispute resolution, fast, and the cost is affordable. In the provisions of Article 26, Providers are required to maintain the confidentiality and integrity of user data. Also, Article 38 states that Providers are required to have standard operating procedures in serving users in electronic documents. Elucidation to Article 38 states that what is meant by “standard operating procedures,” among others, is related to the submission and resolution of complaints.

The Indonesian government has made various efforts to educate the public about digital literacy and financial literacy through social media such as Twitter, Facebook, or other platforms. The government clearly explains that illegal P2P Lending generally imposes very high interest, fines, and other fees not even written in the loan agreement. It is an illegal platform because it does not register as electronic system administrators as written in government regulation Number 71 of 2019. Besides, illegal platforms will request excessive access to personal data. Thus, through the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, the Indonesian government has also issued a regulation on the Minister of ICT Regulation Number 20 of 2016, which contains Personal Data Protection in Electronic Systems. Even though it is in the Ministerial Regulation stage (it has not become a Law), the Indonesian government hopes that this control can minimize illegal P2P Lending operations. In article 11, electronic systems used to store personal data must have interoperability and compatibility capabilities and use legal software. Personal data can only be processed and analyzed according to the electronic system operator's needs based on the agreement.

Legal (licensed) P2P Lending must provide consumer complaint services. This provision is also regulated in POJK Number 18/POJK.07/2018 to guide consumers regarding the consumer complaint service mechanism and its resolution (OJK, 2018a). Indeed, the government emphasizes that Illegal P2P Lending does not have consumer complaint services. In Indonesia, OJK and the Fintech Association only handle licensed platforms but do not handle consumer complaints about Illegal Fintech lending. For this reason, the government formed an Investment Alert Task Force (SWI). The establishment of this Investment Alert Task Force is in anticipation of the Illegal platform. It is supervising illegal Fintech lending and all forms of investment such as buying property, securities (deposits, stocks, bonds, mutual funds), precious metals, jewelry, or other forms. The problem is that the public or investors often only pay attention to the return rate offered (return) but forget and pay less attention to the potential risks that might be faced if choosing a form of investment.

In practice, the policies carried out by the government are following the expected goals. The government is obliged to regulate financial service practices to avoid money laundering and Ponzi schemes (fake investment mode). Therefore, the government's decision to require all platforms to be registered is the best decision to monitor and supervise these platforms. It is hoped that the assistance and supervision provided by the OJK and the Association to the P2P Lending platform can provide signs for following these rules and policies. On the other hand, the government's efforts and the fintech association in delivering education to the public was the right decision. In this case, the study and formulation of government regulations must be balanced with the speed of technological change and digital transformation. It would be better if the formulation of government regulations/policies could involve practitioners to avoid harming each other. In conclusion, a synergy between stakeholders (collaboration), law, supervision, and data protection can reduce the risk of illegal P2P platform practices.

5.4. List of platform P2P lending in Indonesia

The OJK found that until July 2020, the amount of loan disbursement was Rp. 116.97 trillion, an increase of 134.91% year on year. As of August 14, 2020, the total number of fintech peer-to-peer lending or fintech lending operators registered and licensed with the OJK was 157 companies. There are 124 registered platforms and 33 licensed platforms. Of the total 157 platforms, 146 are conventional platforms, and 11 are sharia platforms. There is one fintech lending operator whose certificate of registration has been canceled, namely PT Assetku Mitra Bangsa (Assetkita) (OJK, 2020a). A list of platform names can be seen in the bibliography.

5.5. Issues of platform P2P lending in Indonesia

The results of our literature review, content analysis, and stakeholder interviews identified several issues that are divided into themes such as public awareness about P2P lending (user understanding), data leakage and restriction of data access, including personal data protection, personal data fraud, illegal fintech lending, and product marketing ethics.

Several studies discuss the adoption of fintech P2P lending regarding user awareness and understanding. In Korea, P2P platform companies are a fast-growing fintech sector. However, most mobile applications for the platform in Korea have not been evaluated by users as the industry is a startup. User acceptance of mobile P2P loans is influenced by perceptions of usability, ease of use and user satisfaction (Lee, 2017). Trust in fintech services affects users' attitudes towards adoption (Hu et al., 2019). Another study adopts regulatory focus theory (RFT) as a comprehensive theory to explain the factors that motivate consumers to adopt fintech in China by investigating the cost and benefit aspects (Chang et al., 2016). Aspects that influence the fintech transaction process in Brazil are trust, personal innovation, perceived utility, ease of use and social influence; constructs such as privacy, stigma, and transaction distance also influence transaction processing (Contreras Pinochet et al., 2019).

The Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) informs rules about how to handle data and minimize privacy risks that center on people's understanding of their own data (van den Broek and van Veenstra, 2018). The protection of consumer data in fintech P2P lending mostly depends on the exchange of data between its consumers (Anugerah and Indriani, 2018). Important questions that need to be explored are procedures for protecting customers' borrower data and sanctioning a platform (Hidayat et al., 2020). In Article 26 paragraph (1) of Law 19/2016 on Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE), personal rights include enjoying a private life (free from interference), the right to communicate with others, and the right to access information. Previous studies have proposed a financial service provider location-based service (LBS) framework, including a discussion of user privacy (Li et al., 2019a, b).

A further issue is that operators of online peer-to-peer lending platforms can decide which information to display in a loan request, potentially influencing the investment behavior of lenders (Prystav, 2016). Ideally, the credit scoring process in P2P lending will minimize information asymmetry (Pokorná and Sponer, 2016). As a signal for borrowers' creditworthiness, social capital plays an important role in influencing risk perceptions and building initial trust (Chen et al., 2015). Factors to be considered include the value of information and how it should be further utilized by the platform to maintain a return on investment (Jones and Jones, 2016). For this reason, the process of analyzing information to determine borrower eligibility should involve artificial intelligence. The platform can use big data to analyze the borrower's social media and obtain creditworthiness information from social media and e-commerce usage history data (Liu et al., 2019a). This happens because the P2P lending industry cannot access the credit score of prospective borrowers via official channels such as banks (Ma et al., 2018).

The important issue in this discussion is illegal fintech P2P lending. The platform is illegal if it did not receive permission from the authorities for either platform registration or implementation (Suryono et al., 2019b). Supervision by OJK is needed for comprehensive regulatory reasons (Abubakar and Handayani, 2018). The emergence of financial technology made it easier to raise funds from large groups of people, including P2P lending and crowdfunding. For this reason, China provides an explanation of the regulation of illegal fundraising (Liu et al., 2018). Our research suggests how to build a system for analyzing social media or online news to identify issues and trends about fintech practice (Suryono and Budi, 2019) (Pohan et al., 2019) (Pengnate and Riggins, 2020).

It is important to understand how a platform or a company carries out marketing strategies and that those marketing strategies must follow applicable rules. African fintech companies are adapting their marketing strategy for successful market expansion into new African countries (Hammerschlag et al., 2020). Illegal fintechs use any form of social media to offer their products. Illegal fintech players carry out their business activities without permission. Many of their products and services do not follow applicable regulations, especially those related to data security and consumer protection. We recommend that people be aware and check before making online loan transactions (Leong et al., 2017).

6. Conclusion and recommendation

Based on the results of literature reviews, content analysis, and focus group discussions, this research contributes to identifying issues of fintech practice in Indonesia. Describing systematically in a major discussion theme to find gaps in P2P lending research, such as user understanding, user data privacy and consumer protection, minimizing fraud, increasing surveillance of illegal P2P lending (including strengthening regulations and the role of associations).

Further research could propose a supervisory standard for technology and regulation. Currently, several studies to see the analytical sentiment of P2P products have been carried out by previous researchers (Suryono and Budi, 2019) (Pohan et al., 2019) (Pengnate and Riggins, 2020). It is better if the social media data can be processed by the OJK, SWI and the Ministry of ICT when determining policies and supervision in creating consumer protection. Big data and social media analytics can capture phenomena and analyze problems or trends in society, such as product reviews (Anastasia and Budi, 2017) (Li et al., 2019a) (Vidya et al., 2015), politics (Yue et al., 2019) (Yatim et al., 2017), or hate speech (Okky Ibrohim et al., 2019) (Ibrohim and Budi, 2018). Big data also makes it easier for the government to review reports and coverage in identifying problematic P2P lending fintech platforms. Of course, a monitoring system based on user complaints can be used by various parties following the conditions of P2P lending practices and existing regulators.

Furthermore, there needs to be a comparison of Indonesia's arrangements with other countries. Does the influence of technology, culture, and economic systems influence the rules of Fintech practice. This is an opportunity for further research.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Ryan Randy Suryono, Indra Budi and Betty Purwandari: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research was funded by HIBAH Publikasi Terindeks Internasional (PUTI) Doktor, Universitas Indonesia, grant number NKB-3224/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2020.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Abubakar L., Handayani T. Financial technology: legal challenges for Indonesia financial sector. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018;175(1) [Google Scholar]

- Anastasia S., Budi I. 2016 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science and Information Systems, ICACSIS 2016. 2017. Twitter sentiment analysis of online transportation service providers; pp. 359–365. [Google Scholar]

- Anugerah D.P., Indriani M. Data protection in financial technology services: Indonesian legal perspective. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018;175(1) [Google Scholar]

- Barberis J., Arner D.W. 2016. FinTech in China: from Shadow Banking to P2P Lending. New Economic Windows; pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cai S., Zhang J. Exploration of credit risk of P2P platform based on data mining technology. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2020;372:112718. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y., Wong S.F., Lee H., Jeong S.P. Proceedings of the 18th Annual International Conference on Electronic Commerce E-Commerce in Smart Connected World - ICEC ’16. 2016. What motivates Chinese consumers to adopt FinTech services; pp. 1–3. 17-19-Augu. [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Lai F., Lin Z. A trust model for online peer-to-peer lending: a lender’s perspective. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2014;15(4):239–254. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Dongyu, Lou H., Van Slyke C. Toward an understanding of online lending intentions: evidence from a survey in China. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015;36:317–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Gu Y., Liu Q., Tse Y. How do lenders evaluate borrowers in peer-to-peer lending in China? Int. Rev. Econ. Finance. 2020;69:651–662. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras Pinochet L.H., Diogo G.T., Lopes E.L., Herrero E., Bueno R.L.P. Propensity of contracting loans services from FinTech’s in Brazil. Int. J. Bank Market. 2019;37(5):1190–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Cope D., Bauder Y., Cope L. Australian Centre for Financial Studies. 2018. International competition policy and regulation of financial services – lessons for Australian fintech. [Google Scholar]

- Davis K., Maddock R., Foo M. Catching up with Indonesia’s fintech industry. Law Finan. Market Rev. 2017;11(1):33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dias D. Toronto Centre; 2017. FinTech, RegTech and SupTech: what They Mean for Financial Supervision.http://res.torontocentre.org/guidedocs/FinTech RegTech and SupTech-What They Mean for Financial Supervision.pdf (August). Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ding J., Huang J., Li Y., Meng M. Is there an effective reputation mechanism in peer-to-peer lending? Evidence from China. Finance Res. Lett. 2019;30:208–215. [Google Scholar]

- Duff S. The Aspen Institute - Financial Security Program. 2017. Modernizing digital financial regulation - the envolving role of reglabs in the regulatory stack. [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Fan X., Yoon Y. Lenders and borrowers’ strategies in online peer-to-peer lending market: an empirical analysis of ppdai.com. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2015;16(3):242–260. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84940037183&partnerID=40&md5=8ebb72dfef7ce0b860ad20f3621c2aff Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Fu X., Ouyang T., Chen J., Luo X. Listening to the investors: a novel framework for online lending default prediction using deep learning neural networks. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020;57(4):102236. [Google Scholar]

- Gai K., Qiu M., Sun X. A survey on FinTech. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2018;103:262–273. [Google Scholar]

- Gomber P., Koch J.A., Siering M. Digital Finance and FinTech: current research and future research directions. J. Bus. Econ. 2017;87(5):537–580. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. Credit risk assessment of P2P lending platform towards big data based on BP neural network. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2020;71:102730. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschlag Z., Bick G., Luiz J.M. The internationalization of African fintech firms: marketing strategies for successful intra-Africa expansion. Int. Market. Rev. 2020;37(2):299–317. [Google Scholar]

- He Q., Li X. The failure of Chinese peer-to-peer lending platforms: finance and politics. J. Corp. Finance. 2021;66 [Google Scholar]

- Herrero-Lopez S. Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Social Network Mining and Analysis, SNA-KDD ’09. 2009. Social interactions in P2P lending. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayat A.S., Alam F.S., Helmi M.I. Consumer protection on peer to peer lending financial technology in Indonesia. Int. J. Scient. Technol. Res. 2020;9(1):4069–4072. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85078944359&partnerID=40&md5=52b81faedbf240d6cedf27671f974b97 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Ding S., Li S., Chen L., Yang S. Adoption intention of fintech services for bank users: an empirical examination with an extended technology acceptance model. Symmetry. 2019;11(3) [Google Scholar]

- Huang R.H. Online P2P lending and regulatory responses in China: opportunities and challenges. Eur. Bus. Organ Law Rev. 2018;19(1):63–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hudaefi F.A. How does Islamic fintech promote the SDGs? Qualitative evidence from Indonesia. Qual. Res. Finan. Mark. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Ibrohim M.O., Budi I. A dataset and preliminaries study for abusive language detection in Indonesian social media. Proc. Comp. Sci. 2018;135:222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Iman N. Assessing the dynamics of fintech in Indonesia. Invest. Manag. Financ. Innovat. 2018;15(4):296–303. [Google Scholar]

- Irawan I. The role of Indonesian government in protecting borrowers’ data of p2p fintech lending platform. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2020;29:641–647. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85083572804&partnerID=40&md5=3e347dbc6ac0ecdc51f3e248f1a94700 (6 Special Issue) Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Jagtiani J., Lemieux C. Do fintech lenders penetrate areas that are underserved by traditional banks? J. Econ. Bus. 2018;100:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J. Mname, Liao L. Mname, Wang Z. Mname, Zhang X. Mname. Government affiliation and fintech industry: the peer-to-peer lending platforms in China. SSRN Elec. J. 2018;62:87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jones J., Jones J. 2016. How Microfinance Can Close Asymmetrical Information on Peer-To-Peer Platforms. [Google Scholar]

- Kohardinata C., Soewarno N., Tjahjadi B. Indonesian peer to peer lending (P2P) at entrant’s disruptive trajectory. Bus. Theor. Pract. 2020;21(1):104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawan R. Proceedings of 2019 International Conference on Information Management and Technology, ICIMTech 2019. 2019. Examination of the factors contributing to financial technology adoption in Indonesia using technology acceptance model: case study of peer to peer lending service platform; pp. 432–437. [Google Scholar]

- Lee I., Shin Y.J. Fintech: ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Bus. Horiz. 2018;61(1):35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Evaluation of mobile application in user’s perspective: case of P2P lending apps in FinTech industry. KSII Trans. Internet Info. Syst. 2017;11(2):1105–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Leong C., Tan B., Xiao X., Tan F.T.C., Sun Y. Nurturing a FinTech ecosystem: the case of a youth microloan startup in China. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017;37(2):92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Wu C., Mai F. The effect of online reviews on product sales: a joint sentiment-topic analysis. Inf. Manag. 2019;56(2):172–184. [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Li W., Wen Q.Y., Chen J., Yin W., Liang K. An efficient blind filter: location privacy protection and the access control in FinTech. Future Generat. Comput. Syst. 2019;100:797–810. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. yong, Chiou L.J., Li C., Chung, Ye X.W. Analysis of Beijing Tianjin Hebei regional credit system from the perspective of big data credit reporting. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2019;59:300–308. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Qiao H., Wang S., Li Y. Platform competition in peer-to-peer lending considering risk control ability. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019;274(1):280–290. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Huang F., Yeung H. The regulation of illegal fundraising in China. Asia Pac. Law Rev. 2018;26(1):77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Zhao X., Zhou Z., Liu Y. A new aspect on P2P online lending default prediction using meta-level phone usage data in China. Decis. Support Syst. 2018;111(May):60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Communication and Informatics . 2016. Regulation of the Minister of Communication and Information Technology of the Republic of Indonesia Number 20 of 2016 Concerning Protection of Personal Data in Electronic Systems. JDIH KOMINFO RI.https://jdih.kominfo.go.id/produk_hukum/view/id/553/t/peraturan+menteri+komunikasi+dan+informatika+nomor+20+tahun+2016+tanggal+1+desember+2016 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Communication and Informatics . Republic of Indonesia Government Regulation Number 71 of 2019 Concerning Implementation of Electronic Systems and Transactions. JDIH BPK RI; 2019. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Njatrijani R., Prananda R.R. Risk and performance in technology service platform of online peer-to-peer (P2P) mode. Int. J. Scient. Technol. Res. 2020;9(3):5404–5406. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85083771113&partnerID=40&md5=0ce1dc02d280bc17024c90663f98a920 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Nugraha A.P., Rolando, Puspasari M.A., Syaifullah D.H. Usability evaluation for user Interface redesign of financial technology application. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019;505(1) [Google Scholar]

- OJK . Vol. 77. OJK 1; 2016. Financial Services Authority Regulation Number 77 of 2016 Concerning Information Technology-Based Lending and Borrowing Services. [Google Scholar]

- OJK . OJK; 2018. Financial Services Authority Regulation on Consumer Complaint Services in the Financial Services Sector.https://www.ojk.go.id/id/regulasi/Documents/Pages/Layanan-Pengaduan-Konsumen-di-Sektor-Jasa-Keuangan/POJK18-2018%281%29.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- OJK . Otoritas Jasa Keuangan; 2018. Perbandingan Fintech Lending Ilegal Dan Terdaftar/Berizin.https://www.ojk.go.id/id/kanal/iknb/data-dan-statistik/direktori/fintech/Pages/FAQ-Kategori-Umum.aspx Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- OJK . Otoritas Jasa Keuangan; 2019. FAQ: kategori umum (fintech)https://www.ojk.go.id/id/kanal/iknb/data-dan-statistik/direktori/fintech/Pages/FAQ-Kategori-Umum.aspx Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- OJK . Otoritas Jasa Keuangan; 2019. Perkembangan fintech lending (pendanaan gotong royong online) [Google Scholar]

- OJK . OJK; 2020. List of Registered and Licensed Fintech Lending at OJK.https://www.ojk.go.id/id/kanal/iknb/financial-technology/Pages/-Penyelenggara-Fintech-Terdaftar-dan-Berizin-di-OJK-per-14-Agustus-2020.aspx Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- OJK . 2020. Perkembangan Fintech Lending November 2020; pp. 1–11. (November) [Google Scholar]

- Okky Ibrohim M., Sazany E., Budi I. Identify abusive and offensive language in Indonesian twitter using deep learning approach. J. Phys. Conf. 2019;1196(1) [Google Scholar]

- Pengnate S., Riggins F.J. The role of emotion in P2P microfinance funding: a sentiment analysis approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020;54 [Google Scholar]

- Pişkin M., Kuş M.C. Islamic online P2P lending platform. Proc. Comp. Sci. 2019;158:415–419. [Google Scholar]

- Pohan N.W.A., Budi I., Suryono R.R. Sriwijaya International Conference International Conference of Information Technology and its Applications, 172(Siconian 2019) 2019. Borrower sentiment on P2P lending in Indonesia based on google playstore reviews; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pokorná M., Sponer M. Social lending and its risks. Proc. Social Behav. Sci. 2016;220:330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Pryanka A. 2018. Ini Tiga Acuan Dalam Kode Etik Industri Fintech Lending.https://www.republika.co.id/berita/ekonomi/keuangan/18/08/23/pdwmum370-ini-tiga-acuan-dalam-kode-etik-industri-fintech-lending Retrieved from Republika.co.id website. [Google Scholar]

- Prystav F. Personal information in peer-to-peer loan applications: is less more? J. Behav. Exp. Finan. 2016;9:6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rosavina M., Rahadi R.A., Kitri M.L., Nuraeni S., Mayangsari L. P2P lending adoption by SMEs in Indonesia. Qual. Res. Finan. Mark. 2019;11(2):260–279. [Google Scholar]

- Saputra A.D., Burnia I.J., Shihab M.R., Anggraini R.S.A., Purnomo P.H., Azzahro F. Proceedings of 2019 International Conference on Information Management and Technology, ICIMTech 2019. 2019. Empowering women through peer to peer lending: case study of Amartha.com; pp. 618–622. (August) [Google Scholar]

- Siek M., Sutanto A. Proceedings of 2019 International Conference on Information Management and Technology, ICIMTech 2019. 2019. Impact analysis of fintech on banking industry; pp. 356–361. [Google Scholar]

- Suryono R.R., Budi I. Sriwijaya International Conference International Conference of Information Technology and Its Applications, 172(Siconian 2019) 2019. P2P lending sentiment analysis in Indonesian online news; pp. 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Suryono R.R., Budi I., Purwandari B. Challenges and trends of financial technology (Fintech): a systematic literature review. Information. 2020;11(12):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Suryono R.R., Marlina E., Purwaningsih M., Sensuse D.I., Sutoyo M.A.H. Proceedings - 2019 International Conference on Computer Science, Information Technology, and Electrical Engineering, ICOMITEE 2019. 129–133. 2019. Challenges in P2P lending development: collaboration with tourism commerce. [Google Scholar]

- Suryono R.R., Purwandari B., Budi I. Peer to peer (P2P) lending problems and potential solutions: a systematic literature review. Proc. Comp. Sci. 2019;161:204–214. [Google Scholar]

- Syamil A., Heriyati P., Devi A., Hermawan M.S. Understanding peer-to-peer lending mechanism in Indonesia: a study of drivers and motivation. ICIC Exp. Lett. Part B: Applications. 2020;11(3):267–277. [Google Scholar]

- Usanti T.P., Silvia F., Setiawati A.P. Dispute settlement method for lending in supply chain financial technology in Indonesia. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2020;9(3):435–443. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85087757090&partnerID=40&md5=b76461559885aa5c67d451153dea720e Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- van den Broek T., van Veenstra A.F. Governance of big data collaborations: how to balance regulatory compliance and disruptive innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2018;129:330–338. (November 2016) [Google Scholar]

- Vidya N.A., Fanany M.I., Budi I. Twitter sentiment to analyze net brand reputation of mobile phone providers. Proc. Comp. Sci. 2015;72:519–526. [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Richad, Octavius Ong Y.B. Analysis the use of P2P lending mobile applications in Indonesia. J. Phys. Conf. 2019;1367(1) [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.G., Xu H., Ma J. Financing the Underfinanced: Online Lending in China. 2015. Financing the underfinanced: online lending in China. [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. The role of photographs in online peer-to-peer lending behavior. SBP (Soc. Behav. Pers.): Int. J. 2014;42(3):445–452. [Google Scholar]

- Yatim M.A.F., Wardhana Y., Kamal A., Soroinda A.A.R., Rachim F., Wonggo M.I. 2016 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science and Information Systems, ICACSIS 2016. 2017. A corpus-based lexicon building in Indonesian political context through Indonesian online news media; pp. 347–352. [Google Scholar]

- Yue L., Chen W., Li X., Zuo W., Yin M. A survey of sentiment analysis in social media. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2019;60(2):617–663. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus U. A comparison peer to peer lending platforms in Singapore and Indonesia. J. Phys. Conf. 2019;1235(1) [Google Scholar]

- Zavolokina L., Dolata M., Schwabe G. Thirty Seventh International Conference on Information Systems. Vol. 2. 2016. FinTech - what’s in a name? pp. 469–490. (4) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Wang C., Zhang Y., Wang J. Credit risk evaluation model with textual features from loan descriptions for P2P lending. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020;42(May):100989. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.