Abstract

Rotator cuff related disorders (RCRD) are common. Exercise-based rehabilitation can improve outcomes, yet uncertainty exists regarding the characteristics of these exercises. This scoping review paper summarises the key characteristics of the exercise-based rehabilitation of rotator cuff related disorders (RCRD). An iterative search process was used to capture the breadth of current evidence and a narrative summary of the data was produced. 57 papers were included. Disagreement around terminology, diagnostic standards, and outcome measures limits the comparison of the data. Rehabilitation should utilise a biopsychosocial approach, be person-centred and foster self-efficacy. Biomedically framed beliefs can create barriers to rehabilitation. Pain drivers in RCRSD are unclear, as is the influence of pain during exercise on outcomes. Expectations and preferences around pain levels should be discussed to allow the co-creation of a programme that is tolerated and therefore engaged with. The optimal parameters of exercise-based rehabilitation remain unclear; however, programmes should be individualised and progressive, with a minimum duration of 12 weeks. Supervised or home-based exercises are equally effective. Following rotator cuff repair, rehabilitation should be milestone-driven and individualised; communication across the MDT is essential. For individuals with massive rotator cuff tears, the anterior deltoid programme is a useful starting point and should be supplemented by functional rehabilitation, exercises to optimise any remaining cuff and the rest of the kinetic chain. In conclusion, exercise-based rehabilitation improves outcomes for individuals with a range of RCRD. The optimal parameters of these exercises remain unclear. Variation exists across current physiotherapy practice and post-operative rehabilitation protocols, reflecting the wide-ranging spectrum of individuals presenting with RCRD. Clinicians should use their communication and rehabilitation expertise to plan an exercise-based program in conjunction with the individual with RCRSD, which is regularly reviewed and adjusted.

Keywords: Physical therapy, Rehabilitation, Rotator cuff disorder, Rotator cuff tear, Current concepts

1. Introduction

Rotator cuff related disorders (RCRD) are common, 40% of individuals report symptoms persisting longer than 12 months,1 including significant pain, disturbed sleep, and a loss of function.2 RCRD includes a spectrum of conditions such as tendinopathy, subacromial bursitis and acute and chronic tears.

Whilst several adjunct treatments exist, the value of education and exercise as the first line in the rehabilitation of RCRD is widely accepted.3, 4, 5, 6 Yet the characteristics of this rehabilitation and the subgroups of individuals most likely to benefit are unclear. Disagreement around terminology, pathoetiology, diagnostic standards, and outcome measures leads to a lack of comparable data.7 Uncertainty exists regarding the management of RCRD, the evidence base is extensive, yet several questions remain unanswered.

This scoping review paper aims to identify key characteristics of exercise-based rehabilitation of RCRD. A range of quantitative and qualitative sources will be summarised to provide an overview of the current concepts for all members of the multi-disciplinary team (MDT).

2. Methodology

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was used as a basis for this review.8 The Cochrane, Cinahl, and Medline databases were searched with the support of a Trust librarian.

To ensure the breadth and range of current evidence for RCRD were covered whilst maintaining a focus on exercise-based rehabilitation an iterative process was used (Table 1), combining search terms in each concept using Boolean operator OR. Concepts one to four were then each combined with concept five using AND.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

| Concept one: rotator cuff related shoulder pain | Concept two: rotator cuff tears | Concept three: massive cuff tears | Concept four: principles of rehabilitation | Concept five: exercise-based rehabilitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rotator cuff Shoulder pain Subacromial impingement Subacromial bursitis Painful arc syndrome Rotator cuff tendinopathy |

Rotator cuff Partial thickness tear Full thickness tear Degenerative tear Traumatic tear |

Massive rotator cuff tear Irreparable rotator cuff tear Shoulder Pseudo-paralysis |

Rotator cuff Rehabilitation physiotherapy physical therapy Person-centred Shared decision making. Language Education Expectations Communication |

Physiotherapy Physical therapy Rehabilitation Exercise Eccentric Isometric Heavy resistance Non-surgical Conservative |

Reference list mining and citation searches were undertaken by hand. The first and final searches were undertaken on 30th July 2020 and 30th November 2020.

The titles and when required, abstracts from the search results were screened by one author against set inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). For pragmatic reasons, the search was limited to papers published between 2016 and 2020 and in English with full text available. To maintain high methodological standards, systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials were included. Qualitative designs were included to reflect the breadth of the current evidence base. All other study designs were excluded. Papers used to inform the background to the paper, or those deemed seminal were all included.

Table 2.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Patient: adults with a clinical or radiological diagnosis of rotator cuff related shoulder pain of any duration. | Patient: adults with other shoulder diagnoses including but not limited to instability, frozen shoulder or arthritis. |

| Intervention: exercise-based rehabilitation. | Intervention: non-exercise-based treatments including but not limited to surgery, medications, injections, taping, electrotherapy or manual therapy. |

| Comparator: usual care, sham, or no treatment group. | Comparator: studies with only one arm that is eligible. |

| Outcome: any clinical or patient reported outcome measures. | Outcome: biomechanical or muscle activity outcome measures. |

3. Results

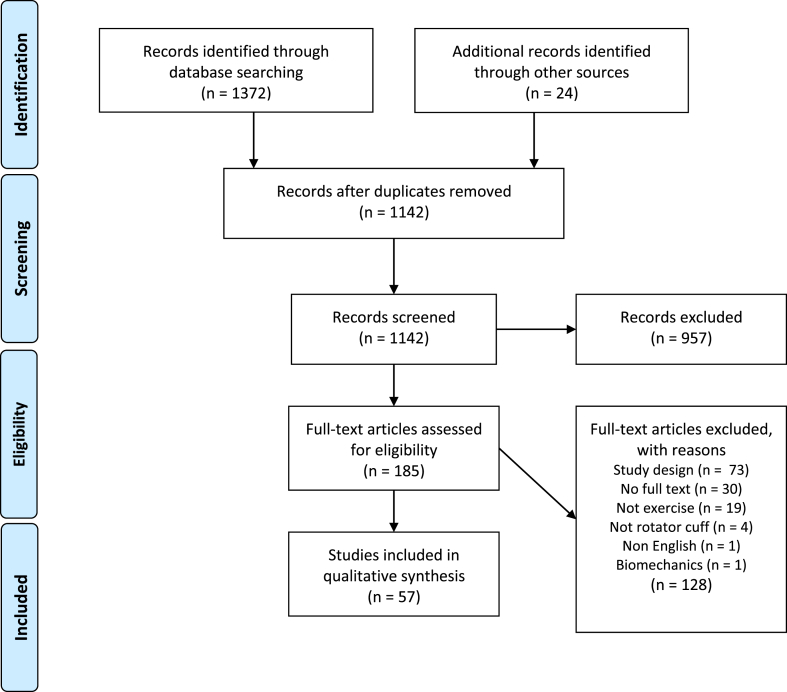

The Prisma diagram for the search is shown in Fig. 1, 57 papers were included. Full-text papers were assigned for review by a single author to extract data including study design, study population, number of participants (or studies for systematic reviews), interventions, outcome measures, and results. Study design and level of evidence were used to describe the quality of the evidence. Due to the scoping nature of the review, a formal analysis of methodological quality or risk of bias was not performed. A narrative summary of the data was produced.

Fig. 1.

Prisma diagram.

4. Key concepts in the rehabilitation of RCRD

4.1. A biopsychosocial approach

Co-morbidities associated with increased risk of shoulder pain such as high BMI or metabolic disorders should be screened for9 and the individual’s ‘physiological age’ considered. Lifestyle factors associated with the risk of such disorders including diet, smoking, and low activity levels should be discussed. Rehabilitation professionals are uniquely placed to support patients in health-related behaviour change and a symptomatic shoulder should be considered a potential driver for such changes. A biopsychosocial assessment is considered good practice for individuals with persistent rotator cuff related shoulder pain and should consider how the individual’s pain beliefs, coping strategies, or social context could contribute to their symptoms.10,11 Central nervous system involvement and sensitisation should also be considered in individuals with persistent shoulder pain including widespread hyperalgesia, pain disproportionate to structural findings, or altered pain pressure or cold thresholds.12

4.2. General principles of high quality RCRD rehabilitation

The uncertainty regarding optimal management of RCRD should be explained to the individual in terms that they can understand and without bias from the clinician.

General principles of tendinopathy management are useful in the rehabilitation of RCRD; education, controlled unloading, reloading, and prevention of recurrence.13 Considering the spectrum of clinical presentations of RCRD care should be individualised and person-centred.14 Rehabilitation should foster self-efficacy, hence active rather than passive modalities are favoured. If individuals fail to respond as expected, a shared decision-making approach should be used regarding ongoing management.

4.3. Communication and education in RCRD

Open questioning and active listening should be used to ensure that the individual’s specific ideas, concerns, and questions regarding their symptoms are explored.15

Rehabilitation requires self-efficacy, motivation, and compliance; hence early education is essential to ensure individuals are engaged in the process.16 The information provided to the individual must be appropriate for their level of health literacy and delivered with consideration of the individuals learning preferences.17, 18, 19

5. Rotator cuff related shoulder pain (RCRSP) rehabilitation

The optimal rehabilitation for RCRSP is unclear, reflecting the often complex and varied presentation of the individuals with the condition. Exercise and education are recognised as core components of the rehabilitation of RCRSP by expert consensus,20,21 yet wide variation in practice exists.22,23

5.1. Managing expectations

The pain drivers in RCRSD remain uncertain,24 yet biomedically framed beliefs are prevalent in individuals with RCRD25 and can create barriers to rehabilitation.16 Hence, as with most non-traumatic musculoskeletal conditions, if suspicion of serious pathology is low initial diagnostic imaging is discouraged26 and clinicians should be aware of the power of their language when discussing diagnoses.27

Pain is frequently a significant factor for these individuals and can reduce tolerance of exercise-based interventions.28 The influence of pain during exercise on outcomes is unclear, with improvements seen in both painful and pain-free groups.29 It is generally accepted that pain may increase slightly during exercise but should remain tolerable and settle quickly.30 Hence expectations and preferences around pain level should be discussed with the individual and a rehabilitation programme agreed which is tolerated and therefore engaged with. Clinicians should consider that this may result in an exercise prescription which initially aims to build self-efficacy and participation rather than induce physiological changes. Clinicians should regularly re-assess, review, and adjust the programme as the individual with RCRSP makes progress.

5.2. Exercise parameters

In the mid to long-term, higher dose or progressive and resisted exercises may provide greater improvement in pain and function in comparison to placebo, no treatment, lower dose, or non-resisted exercise.31,32 Supervised and home exercise programmes appear equally effective in improving pain and function at around 12 weeks in this patient group.,33,34

The optimal number of repetitions and sets for exercise-based rehabilitation is uncertain, more repetitions and sets may improve outcomes compared to fewer. A minimum duration of twelve weeks exercise-based rehabilitation is thought to be needed to see clinically significant improvements.35 It is acknowledged in the evidence base that studies investigating exercise-based interventions must fully report doses to allow comparison of results.36

Several randomised controlled trials have compared specific exercise parameters such as inclusion of stretches,37 varying load,38, 39, 40 varying type of exercise,41, 42, 43 and the addition of novel exercises.44, 45, 46 Improvements in short term outcomes for each exercise-based intervention are common. However sample sizes are small and lack of significant difference between groups supports the uncertainty around the optimal variables for exercise-based rehabilitation.

5.3. Type of loading programme

The RCRSD literature reflects the uncertainty across wider tendinopathy research regarding types of loading. Varied responses between individuals with RCRSD to isometric loading47 and a small, non-clinically significant improvement in pain after a twelve-week eccentric loading programme48, 49, 50, 51 are reported.

5.4. Scapular focused exercises

Scapular focused exercises may improve pain and function in RCRSP in the short term.52 Findings should be interpreted with caution due to small sample sizes and significant heterogeneity of intervention and outcome measures.53, 54, 55

6. Rehabilitation of partial thickness (PTT) and full thickness (FTT) rotator cuff tears

6.1. Managing expectations

Non-traumatic rotator cuff tendon tears are part of the continuum of RCRD tendon pathology.56 Tears are defined as structural failure of one or more of the rotator cuff tendons. Full thickness tears extend to the entire depth of the tendon, whilst partial thickness tears do not.57

Comparing surgical and non-surgical management of individuals with rotator cuff tears is beyond the scope of this review. However, clinicians should be aware of risk factors associated with poor outcomes following non-operative treatment, including low expectations of physiotherapy treatment.58 Hence individuals with symptomatic rotator cuff tears should be supported to understand their diagnosis and prognosis; that improvements in symptoms can occur despite structural changes to the tendons. Uncertainty around the natural history and progression of symptomatic rotator cuff tears to becoming irreparable and resulting in permanent loss of function, further complicates the issue and a multi-disciplinary approach to decision making is advocated. Younger, more active patients should be adequately counselled regarding this uncertainty.59

6.2. Rehabilitation of non-operatively managed tears

A lack of agreement around definitions and diagnostics means considerable overlap exists in the literature. Several studies of exercise-based rehabilitation for RCRSP include individuals with PTT within their samples.31,32,34,36,37,40, 41, 42, 43, 44,47 Individuals with symptomatic non-traumatic PTT or FTT can be successfully managed using the same principles as RCRSP, education, and an individualised, progressive exercise prescription.59, 60, 61, 62 Individuals failing to show any improvement following 12 weeks rehabilitation should be referred on for further imaging and a specialist opinion.57 Beliefs and expectations should be explored as part of the rehabilitation process. In individuals with persistently symptomatic FTT a strong preference in favour of surgical management has been reported.63

6.3. Rehabilitation of post-operative rotator cuff repairs

Expert consensus regarding post-operative rehabilitation is limited by a lack of high-quality studies64 and wide variation currently exists between individual surgeon’s post-operative protocols.65

Concerns regarding the failure of surgical repairs drive the debate around protection and immobilisation versus early mobilisation and controlled load, preventing stiffness and further deconditioning of the soft tissues. Slings are used to protect the healing tissues but reported side effects including impaired gait and increased risk of falls and patient frustration due to delayed function and return to work.66,67 A delay in the post-operative range of movement is argued to cause stiffness, weakness and be detrimental to the healing tendon structure. Descriptions of the individual’s experience or perceptions of post-operative rehabilitation suggest a preference for early mobilisation.68

In the current literature there is a trend toward support for minimal sling use and controlled early mobilisation to improve outcomes following rotator cuff repair, with no impact on failure rates.64,69, 70, 71, 72 However, comparative studies frequently exclude individuals with larger repairs and concerns around higher re-tear rates in this population necessitates further work to clarify the risks and benefits of early mobilisation in this subgroup.69,73,74

Currently, exercise-based rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair is often governed by time-dependent protocols. There is increasing support however that rehabilitation should be milestone-driven, individualised and consider the size and type of surgical repair, tissue quality, tendon healing, and patient characteristics.60 In the absence of high quality RCT results, communication across the MDT is essential and allows Upper Limb Units safely implement accelerated post-operative rehabilitation protocols where clinically appropriate.

Once guidance and reassurance have been provided to individuals following rotator cuff repair, self-administered and supervised home exercises appear equally effective with unsupervised rehabilitation having lower health-care-associated costs,75,76 In the absence of evidence based prognostic indicators and acknowledging the importance of individualised care, clinician’s expertise must be utilised to identify individuals likely to benefit from increased support post-operatively.

7. Rehabilitation of massive rotator cuff tears (MRCTs)

MRCTs involve full-thickness tears of two or more tendons or tears measuring more than 5 cm.77 MRCTs are commonly surgically irreparable or are present in individuals with significant co-morbidities and hence surgical risk.

As with other classifications of a cuff tear, MRCTs can exist asymptomatically supporting the theory that individuals can compensate for a loss of cuff function. The Torbay anterior deltoid exercise programme is well established in the rehabilitation of MRCTs and when combined with functional rehabilitation can improve functional outcomes.78

The premise of recruiting the anterior deltoid is to optimise the coupling forces around the shoulder and allow glenohumeral joint elevation without the upward sheering of the humeral head.79 This effect may be enhanced if some active external rotation is preserved and an intact subscapularis tendon appears predictive of better outcomes. The involvement of 3 or more tendons is predictive of poorer outcomes.77,78

The evidence base for exercise-based rehabilitation for MRCT is limited. Readers should be reminded that no level I studies were identified by this search and significant heterogeneity of the published research limits comparison or meta-analysis of treatment outcomes.80 Clinically, the decision to proceed with non-operative management should be a collective one involving the individual, the surgeon, and the therapist and considering the individual’s expectations, functional aims, and tear characteristics.

The available evidence plus expert opinion does support the role of exercised based rehabilitation in this patient group.78, 79, 80, 81 Rehabilitation has also been shown to be cost-effective.82 The clinical significance of improvement in outcomes following rehabilitation and individual’s perceptions of the process remain unclear. Measures of general and emotional health can remain unchanged despite exercise-based rehabilitation following MRCT suggesting not all upper limb function is recovered.78 Further work is needed to explore factors predictive of outcome following exercise-based rehabilitation for MRCT such as functional demand, the severity of symptoms, presence of glenohumeral joint osteoarthritis, tear size and retraction, amount of fatty infiltration, and muscle atrophy.

Experience dictates that the rehabilitation programme should be person-focused, considering the individual’s goals, functional requirements, and expectations. The anterior deltoid programme is a useful starting point for the exercise-based rehabilitation of MRCT. This should be supplemented by optimisation of any remaining cuff and the rest of the kinetic chain plus functional rehabilitation. Regular re-assessment is essential to support and progress the individual over the several month rehabilitation process.

8. Conclusion

Exercise-based rehabilitation improves outcomes for individuals with a range of RCRD. The optimal parameters of these exercises remain unclear. Variation exists across current physiotherapy practice and post-operative rehabilitation protocols, reflecting the wide-ranging spectrum of individuals presenting with RCRD.

Exercise-based rehabilitation for RCRSP should be person-centred and promote self-efficacy. Beliefs and expectations should be explored, expertise in communication skills is essential here. Individualised education should be provided to address any potential barriers, such as a strongly biomedically based understanding of RCRSP. Clinicians should use their rehabilitation expertise to plan an exercise-based program in conjunction with the individual with RCRSD, which is regularly reviewed and adjusted. Those who fail to improve following 12 weeks of exercised-based rehabilitation should have access to shared decision-making regarding their ongoing management, with input from across the MDT as required.

Limitations of this work reflect the broad scope of the review and challenges within the evidence base. Disagreement around definitions, diagnosis, and classification of RCRSD persist and heterogeneity of studies reduces opportunities to compare results. Direct comparison of the effectiveness of exercise-based rehabilitation to other treatments is problematic. Hence the rapidly expanding evidence base is shifting to include a wider range of study designs, providing insight into the experience of an individual with RCRSD and of those clinicians involved in their care.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Van der Windt D.A., Koes B.W., Boeke A.J., Devillé W., De Jong B.A., Bouter L.M. Shoulder disorders in general practice: prognostic indicators of outcome. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46:519–523. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minns Lowe C.J., Moser J., Barker K. Living with a symptomatic rotator cuff tear ‘bad days, bad nights’: a qualitative study. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2014;15(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shoulder Pain. National Institute for health and care Excellence. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/shoulder-pain/. Revised April 2017. Accessed November 2020.

- 4.Pieters L., Lewis J., Kuppens K. An update of systematic reviews examining the effectiveness of conservative physical therapy interventions for subacromial shoulder pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020;50(3):131–141. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2020.8498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page M.J., Green S., McBain B. Manual therapy and exercise for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haik M.N., Alburquerque-Sendín F., Moreira R.F., Pires E.D., Camargo P.R. Effectiveness of physical therapy treatment of clearly defined subacromial pain: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Sep 1;50(18):1124–1134. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis J. Rotator cuff related shoulder pain: assessment, management and uncertainties. Man Ther. 2016;23:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burne G., Mansfield M., Gaida J.E., Lewis J.S. Is there an association between metabolic syndrome and rotator cuff-related shoulder pain? A systematic review. BMJ Open SEM. 2019;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000544. e000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coronado R.A., Seitz A.L., Pelote E., Archer K.R., Jain N.B. Are psychosocial factors associated with patient-reported outcome measures in patients with rotator cuff tears? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476(4):810–829. doi: 10.1007/s11999.0000000000000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mallows A., Debenham J., Walker T., Littlewood C. Association of psychological variables and outcome in tendinopathy: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(9):743–748. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plinsinga M.L., Brink M.S., Vicenzino B., Van Wilgen C.P. Evidence of nervous system sensitization in commonly presenting and persistent painful tendinopathies: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45(11):864–875. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2015.5895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davenport T.E., Kulig K., Matharu Y., Blanco C.E. The EdUReP model for nonsurgical management of tendinopathy. Phys Ther. 2005;85(10):1093–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin I., Wiles L., Waller R. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:79–86. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthys J., Elwyn G., Van Nuland M. Patients’ ideas, concerns, and expectations (ICE) in general practice: impact on prescribing. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(558):29–36. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X394833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White J., McAuliffe S., Jepson M. ‘There is a very distinct need for education’ among people with rotator cuff tendinopathy: an exploration of health professionals’ attitudes. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020;45 doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2019.102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cridland K., Pritchard S., Rathi S., Malliaras P. ‘He explains it in a way that I have confidence he knows what he is doing’: a qualitative study of patients’ experiences and perspectives of rotator-cuff-related shoulder pain education. Muscoskel Care. 2020 doi: 10.1002/msc.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meehan K., Wassinger C., Roy J.S., Sole G. Seven key themes in physical therapy advice for patients living with subacromial shoulder pain: a scoping review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020 Jun;50(6) doi: 10.2519/jospt.2020.9152. https://www.jospt.org/doi/10.2519/jospt.2020.9152 285-a12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillespie M.A., Mącznik A., Wassinger C.A., Sole G. Rotator cuff-related pain: patients’ understanding and experiences. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2017 Aug 1;30:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Littlewood C., Bateman M., Connor C. Physiotherapists’ recommendations for examination and treatment of rotator cuff related shoulder pain: a consensus exercise. Physiother Pract Res. 2019;40(2):87–94. doi: 10.3233/PPR-190129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eubank B.H., Mohtadi N.G., Lafave M.R. Using the modified Delphi method to establish clinical consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with rotator cuff pathology. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016 Dec;16(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0165-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bury J., Littlewood C. Rotator cuff disorders: a survey of current (2016) UK physiotherapy practice. Shoulder Elbow. 2018;10(1):52–61. doi: 10.1177/1758573217717103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanratty C.E., Kerr D.P., Wilson I.M. Physical therapists’ perceptions and use of exercise in the management of subacromial shoulder impingement syndrome: focus Group Study. Phys Ther. 2016 Sep 1;96(9):1354–1363. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20150427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Littlewood C., Malliaras P., Bateman M., Stace R., May S., Walters S. The central nervous system–an additional consideration in ‘rotator cuff tendinopathy’ and a potential basis for understanding response to loaded therapeutic exercise. Man Ther. 2013;18(6):468–472. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuff A., Littlewood C. Subacromial impingement syndrome – what does this mean to and for the patient? A qualitative study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018;33:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin I., Wiles L., Waller R. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:79–86. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart M., Loftus S. Sticks and stones: the impact of language in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(7):519–522. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2018.0610. https://www.jospt.org/doi/10.2519/jospt.2018.0610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandford F.M., Sanders T.A., Lewis J.S. Exploring experiences, barriers, and enablers to home-and class-based exercise in rotator cuff tendinopathy: a qualitative study. J Hand Ther. 2017;30(2):193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vallés-Carrascosa E., Gallego-Izquierdo T., Jiménez-Rejano J.J. Pain, motion and function comparison of two exercise protocols for the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers in patients with subacromial syndrome. J Hand Ther. 2018;31(2):227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2017.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Littlewood C., Bateman M., Brown K. A self-managed single exercise programme versus usual physiotherapy treatment for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a randomised controlled trial (the SELF study) Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(7):686–696. doi: 10.1177/0269215515593784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malliaras P., Johnston R., Street G., C. The efficacy of higher versus lower dose exercise in rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Arch Phys Med. 2020;101(10):1822–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naunton J., Street G., Littlewood C., Haines T., Malliaras P. Effectiveness of progressive and resisted and non-progressive or non-resisted exercise in rotator cuff related shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(9):1198–1216. doi: 10.1177/0269215520934147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutiérrez-Espinoza H., Araya-Quintanilla F., Cereceda-Muriel C., Álvarez-Bueno C., Martínez-Vizcaíno V., Cavero-Redondo I. Effect of supervised physiotherapy versus home exercise program in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2020;41:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2019.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granviken F., Vasseljen O. Home exercises and supervised exercises are similarly effective for people with subacromial impingement: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2015 Jul 1;61(3):135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Littlewood C., Malliaras P., Chance-Larsen K. Therapeutic exercise for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review of contextual factors and prescription parameters. Int J Rehabil Res. 2015 Jun 1;38(2):95–106. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shire A.R., Stæhr T.A., Overby J.B., Dahl M.B., Jacobsen J.S., Christiansen D.H. Specific or general exercise strategy for subacromial impingement syndrome–does it matter? A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2017 Dec;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1518-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gutiérrez-Espinoza H., Araya-Quintanilla F., Gutiérrez-Monclus R. Does pectoralis minor stretching provide additional benefit over an exercise program in participants with subacromial pain syndrome? A randomized controlled trial. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2019 Dec 1;44:102052. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2019.102052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ingwersen K.G., Jensen S.L., Sørensen L. Three months of progressive high-load versus traditional low-load strength training among patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy: primary results from the double-blind randomized controlled RoCTEx trial. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2017 Aug 23;5(8) doi: 10.1177/2325967117723292. 2325967117723292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Littlewood C., Bateman M., Brown K. A self-managed single exercise programme versus usual physiotherapy treatment for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a randomised controlled trial (the SELF study) Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(7):686–696. doi: 10.1177/0269215515593784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dupuis F., Barrett E., Dubé M.O., McCreesh K.M., Lewis J.S., Roy J.S. Cryotherapy or gradual reloading exercises in acute presentations of rotator cuff tendinopathy: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open Sport & Exerc Med. 2018 Dec 1;4(1) doi: 10.1177/2325967117723292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heron S.R., Woby S.R., Thompson D.P. Comparison of three types of exercise in the treatment of rotator cuff tendinopathy/shoulder impingement syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Physiotherapy. 2017 Jun 1;103(2):167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hallgren H.C., Holmgren T., Öberg B., Johansson K., Adolfsson L.E. A specific exercise strategy reduced the need for surgery in subacromial pain patients. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Oct 1;48(19):1431–1436. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mulligan E.P., Huang M., Dickson T., Khazzam M. The effect of axioscapular and rotator cuff exercise training sequence in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: a randomized crossover trial. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016 Feb;11(1):94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boudreau N., Gaudreault N., Roy J.S., Bédard S., Balg F. The addition of glenohumeral adductor coactivation to a rotator cuff exercise program for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019 Mar;49(3):126–135. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2019.8240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Babaei-Mobarakeh M., Letafatkar A., Barati A.H., Khosrokiani Z. Effects of eight-week “gyroscopic device” mediated resistance training exercise on participants with impingement syndrome or tennis elbow. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2018 Oct 1;22(4):1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schedler S., Brueckner D., Hagen M., Muehlbauer T. Effects of a traditional versus an alternative strengthening exercise program on shoulder pain, function and physical performance in individuals with subacromial shoulder pain: a randomized controlled trial. Sports. 2020 Apr;8(4):48. doi: 10.3390/sports8040048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clifford C., Challoumas D., Paul L., Syme G., Millar N.L. Effectiveness of isometric exercise in the management of tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2020;6(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000760. e000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larsson R., Bernhardsson S., Nordeman L. Effects of eccentric exercise in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2019;20(1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2796-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dejaco B., Habets B., van Loon C., van Grinsven S., van Cingel R. Eccentric versus conventional exercise therapy in patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy: a randomized, single blinded, clinical trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017 Jul;25(7):2051–2059. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blume C., Wang-Price S., Trudelle-Jackson E., Ortiz A. Comparison of eccentric and concentric exercise interventions in adults with subacromial impingement syndrome. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015 Aug;10(4):441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chaconas E.J., Kolber M.J., Hanney W.J., Daugherty M.L., Wilson S.H., Sheets C. Shoulder external rotator eccentric training versus general shoulder exercise for subacromial pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Dec;12(7):1121. doi: 10.26603/ijspt20171121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ravichandran H., Janakiraman B., Gelaw A.Y., Fisseha B., Sundaram S., Sharma H.R. Effect of scapular stabilization exercise program in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review. J Exerc Rehabil. 2020;16(3):216. doi: 10.12965/jer.2040256.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saito H., Harrold M.E., Cavalheri V., McKenna L. Scapular focused interventions to improve shoulder pain and function in adults with subacromial pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiother Theor Pract. 2018 Sep 2;34(9):653–670. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1423656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bury J., West M., Chamorro-Moriana G., Littlewood C. Effectiveness of scapula-focused approaches in patients with rotator cuff related shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Man Ther. 2016 Sep 1;25:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2016.05.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pekyavas N.O., Ergun N. Comparison of virtual reality exergaming and home exercise programs in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome and scapular dyskinesis: short term effect. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turcica. 2017 May 1;51(3):238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.aott.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lewis J.S. Rotator cuff tendinopathy: a model for the continuum of pathology and related management. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:918–923. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.054817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kulkarni R., Gibson J., Brownson P. Subacromial shoulder pain. Shoulder Elbow. 2015;7(2):135–143. doi: 10.1177/1758573215576456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dunn W.R., Kuhn J.E., Sanders R., An Q., Baumgarten K.M., Bishop J.Y. Neer Award: predictors of failure of nonoperative treatment of chronic, symptomatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2013;25(8):1303–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.04.030. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeanfavre M., Husted S., Leff G. Exercise therapy in the non-operative treatment of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018;13(3):335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Longo U.G., Ambrogioni L.R., Berton A., Candela V., Carnevale A., Schena E. Physical therapy and precision rehabilitation in shoulder rotator cuff disease. Int Orthop. 2020;44(5):893–903. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04511-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Türkmen E., Akbaba Y.A., Altun S. Effectiveness of video-based rehabilitation program on pain, functionality, and quality of life in the treatment of rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. J Hand Ther. 2020 Jul 1;33(3):288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gialanella B., Comini L., Gaiani M., Olivares A., Scalvini S. Conservative treatment of rotator cuff tear in older patients: a role for the cycloergometer? A randomized study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2018 May 18;54(6):900–910. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.18.05038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lowe C.J.M., Moser J., Barker K.L. Why participants in the United Kingdom Rotator Cuff Tear (UKUFF) trial did not remain in their allocated treatment arm: a qualitative study. Physiotherapy. 2018;104(2):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jung C., Tepohl L., Tholen R. Rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair. Obere Extremität. 2018;13(1):45–61. doi: 10.1007/s11678-018-0448-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coda R.G., Cheema S.G., Hermanns C.A. A review of online rehabilitation protocols designated for rotator cuff repairs. Arthroscopy, sports medicine, and rehabilitation. 2020 May 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Sonoda Y., Nishioka T., Nakajima R., Imai S., Vigers P., Kawasaki T. Use of a shoulder abduction brace after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a study on gait performance and falls. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2018;42(2):136–143. doi: 10.1177/0309364617695882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sheps D.M., Bouliane M., Styles-Tripp F., Beaupre L.A., Saraswat M.K., Luciak-Corea C. Early mobilisation following mini-open rotator cuff repair: a randomised control trial. Bone Jt J. 2015;97(9):1257–1263. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B9.35250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stephens G., Littlewood C., Foster N.E., Dikomitis L. Rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair: a nested qualitative study exploring the perceptions and experiences of participants in a randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2020 Dec 27 doi: 10.1177/0269215520984025. 0269215520984025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sheps D.M., Silveira A., Beaupre L., Styles-Tripp F., Balyk R., Lalani A. Early active motion versus sling immobilization after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(3):749–760. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.10.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tirefort J., Schwitzguebel A.J., Collin P., Nowak A., Plomb-Holmes C., Lädermann A. Postoperative mobilization after superior rotator cuff repair: sling versus No-sling. A randomized controlled trial: sling versus no-sling after RCR. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(5_suppl 3) doi: 10.1177/2325967119S00211. 2325967119S00211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mazuquin B.F., Wright A.C., Russell S., Monga P., Selfe J., Richards J. Effectiveness of early compared with conservative rehabilitation for patients having rotator cuff repair surgery: an overview of systematic reviews. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(2):111–121. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-095963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baumgarten K.M., Osborn R., Schweinle W.E., Jr., Zens M.J., Helsper E.A. Are pulley exercises initiated 6 weeks after rotator cuff repair a safe and effective rehabilitative treatment? A randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2016 Jul;44(7):1844–1851. doi: 10.1177/0363546516640763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mazzocca A.D., Arciero R.A., Shea K.P., Apostolakos J.M., Solovyova O., Gomlinski G. The effect of early range of motion on quality of life, clinical outcome, and repair integrity after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2017;33(6):1138–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Houck D.A., Kraeutler M.J., Schuette H.B., McCarty E.C., Bravman J.T. Early versus delayed motion after rotator cuff repair: a systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(12):2911–2915. doi: 10.1177/0363546517692543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Longo U.G., Berton A., Risi Ambrogioni L. Cost-effectiveness of supervised versus unsupervised rehabilitation for rotator-cuff repair: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020 Jan;17(8):2852. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Karppi P., Ryösä A., Kukkonen J., Kauko T., Äärimaa V. Effectiveness of supervised physiotherapy after arthroscopic rotator cuff reconstruction: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(9):1765–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kovacevic D., Suriani R.J., Jr., Grawe B.M. Management of irreparable massive rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis of patient-reported outcomes, reoperation rates, and treatment response. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(12):2459–2475. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ainsworth R. Physiotherapy rehabilitation in patients with massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. Muscoskel Care. 2006;4(3):140–151. doi: 10.1002/msc.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Narvani A.A., Imam M.A., Godenèche A. Degenerative rotator cuff tear, repair or not repair? A review of current evidence. Ann R Coll. 2020;102(4):248–255. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2019.0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kooistra B., Gurnani N., Weening A., van den Bekerom M., van Deurzen D. Low level of evidence for all treatment modalities for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(12):4038–4048. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05710-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Javed M., Robertson A., Evans R. Current concepts in the management of irreparable rotator cuff tears. Br J Hosp Med. 2017;78(1):27–30. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2017.78.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kang J.R., Sin A.T., Cheung E.V. Treatment of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Orthopedics. 2017;40(1):e65–e76. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20160926-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]