Abstract

Purpose

To determine if quantitative features extracted from pretherapy fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT estimate prognosis in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective study, PET/CT images and outcomes were curated from 154 patients with locally advanced cervical cancer, who underwent chemoradiotherapy from two institutions between March 2008 and June 2016, separated into independent training (n = 78; mean age, 51 years ± 13 [standard deviation]) and testing (n = 76; mean age, 50 years ± 10) cohorts. Radiomic features were extracted from PET, CT, and habitat (subregions with different metabolic characteristics) images that were derived by fusing PET and CT images. Parsimonious sets of these features were identified by the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator analysis and used to generate predictive radiomics signatures for progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) estimation. Prognostic validation of the radiomic signatures as independent prognostic markers was performed using multivariable Cox regression, which was expressed as nomograms, together with other clinical risk factors.

Results

The radiomics nomograms constructed with T stage, lymph node status, and radiomics signatures resulted in significantly better performance for the estimation of PFS (Harrell concordance index [C-index], 0.85 for training and 0.82 for test) and OS (C-index, 0.86 for training and 0.82 for test) compared with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system (C-index for PFS, 0.70 for training [P = .001] and 0.70 for test [P = .002]; C-index for OS, 0.73 for training [P < .001] and 0.70 for test [P < .001]), respectively.

Conclusion

Prognostic models were generated and validated from quantitative analysis of 18F-FDG PET/CT habitat images and clinical data, and may have the potential to identify the patients who need more aggressive treatment in clinical practice, pending further validation with larger prospective cohorts.

Supplemental material is available for this article.

© RSNA, 2020

Summary

Nomogram models consisting of radiomic signatures and lymph node status obtained from pretreatment PET/CT images and T stage have the potential to identify patients in whom standard chemotherapy is more likely to fail and who may need more aggressive treatment in clinical practice.

Key Points

■ The incorporation of habitat features into radiomics signatures significantly improved the performance of individualized progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) estimation.

■ The radiomics signatures are significant prognostic markers for prediction of PFS and OS at baseline in patients with advanced cervical cancer, independent of clinical characteristics.

■ The radiomics signatures demonstrated significant added value to clinical risk factors (lymph node status and T stage) for individualized prediction of PFS and OS through the comparison between radiomics and clinical nomograms.

Introduction

Cervical cancer remains one of the most common cancers of the female reproductive system and ranks as the third deadliest cancer among women worldwide (1–3). According to the latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (4), chemoradiotherapy remains the standard therapeutic approach for patients with locally advanced cervical cancer (ie, those with stage IIB-IVA according to the new 2018 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO] staging system [5]). However, tailored treatment for individual patients has not been developed to accommodate the large variations in clinical outcomes in patients with the same stage and receiving similar treatment (6,7). Therefore, a better stratification method based on pretreatment prognosis is required to define groups for whom standard therapy is likely to fail and who should be in specific cohorts for future clinical research, such as combination of chemoradiotherapy and target drug or immunotherapy (8).

Fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT, which could provide both metabolic and anatomic information at the same time, is usually integrated to stage cervical cancer (9) and is a preferred imaging method in FIGO stage of greater than or equal to IB1 according to NCCN guidelines (4,9), given its promising ability in detecting lymph node (LN) status (5). Therefore, numerous studies use PET/CT images for prognosis evaluation and have shown its superior sensitivity and specificity in the evaluation of cervical cancer.

Recent developments of radiomics, a method that converts images to large-scale mineable data, have shown the potential added value in discriminatory and prognostic evaluation of cervical cancer (10–12), compared with some commonly used semiquantitative parameters from patient 18F-FDG PET/CT scans, such as maximum standard uptake value (SUVmax), metabolic tumor volume, and total lesion glycolysis (13–15). However, most of the current PET/CT radiomics studies extracted image-derived features independently from PET and CT images, or used radiologist-defined semiquantitative semantic descriptors to characterize PET and CT fusion images for outcome prediction (16–19), and most of the radiomics descriptors generally classify tumors as a whole and seldom accommodate extraction of features from different subregions, called habitats, with different metabolic characteristics (20,21). Some prior studies have observed that different habitats respond differentially to therapy or drive progression (22–24), but habitats have not yet been defined by differential metabolic profiles from PET/CT images. Therefore, we hypothesized that radiomics analysis on features from different habitats defined by fusing PET and CT images could outperform conventional radiomic profiles in prognosis evaluation of cervical cancer.

In this study, we aimed to develop radiomics signatures based on the fused PET/CT habitat radiomic features to predict the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with locally advanced squamous cell cervical cancer treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy and to evaluate their incremental value to the new 2018 FIGO staging system.

Materials and Methods

Patients Overview

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of South Florida and the Cancer Institute and Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CIH); the need for informed consent was waived.

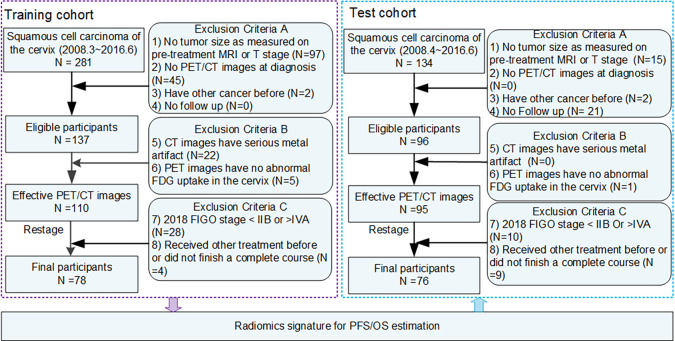

There were 281 and 134 patients with histologically proven squamous cell cervical cancer who underwent PET/CT imaging and were treated with chemoradiotherapy between March 2008 and June 2016, who were first curated from H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute (HLM) in the United States and CIH in China, respectively. The baseline patient demographics (age), tumor characteristics (tumor differentiation grade, tumor size as measured at pretreatment MRI, and T stage), treatment types (details provided in Appendix E1 [supplement]), and survival outcomes (PFS and OS) were obtained from the medical records. The detailed sequential exclusion criteria included the following: (a) no tumor size as measured at pretreatment MRI or T stage, (b) no PET/CT images at diagnosis before treatment, (c) a previous history of other cancer, (d) no follow-up information, (e) CT images with serious metal artifact due to metallic objects (eg, belly-button ring or intrauterine device), and (f) no abnormal 18F-FDG uptake in the cervix. A total of 110 patients from HLM and 95 patients from CIH remained. For these patients, the presence of LN and/or metastatic disease was further obtained from the PET/CT images by experienced radiologists (Y.L. and Y.T., with 23 and 10 years of experience, respectively) who were blind to the clinical outcomes. Using the tumor size and the presence of lymph nodes and/or metastatic disease in the baseline PET/CT images, patients were restaged using the FIGO 2018 system. Finally, only patients with stage IIB-IVA and complete course of chemoradiotherapy (at least 5 weeks) were included in this retrospective study. A total of 154 patients, 78 from HLM and 76 from CIH, were included in this study and were used as the training and independent test dataset, respectively. Detailed information is provided in Figure 1. Among all the participants, 27 of them were used to developed a semiautomatic segmentation method to delineate the cervical tumor (25), and 30 of them were used in a preliminary study to investigate the association between textural features and clinical stage (26).

Figure 1:

Diagram of study participant enrollment. The training cohort including 78 patients was used to train the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) prediction model, which was externally validated with the 76 patients collected from another institute. FDG = fluorodeoxyglucose, FIGO = International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

PFS and OS were chosen as two separate end points of the study, which were defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to progression or death, respectively. Patients alive (or free of progression) or lost to follow-up were censored at the time of last confirmed contact.

PET/CT Imaging

All patients underwent PET/CT imaging before the start of treatment, and details are provided in Appendix E2 (supplement). To ensure the training data and the test data have the same resolution of 1 3 1 3 1 mm3, bilinear interpolation or downsampling was performed. Subsequently, PET images were converted into SUV units by normalizing the activity concentration to the dosage of 18F-FDG injected and the patient body weight after decay correction.

Habitat Generation and Image Feature Extraction

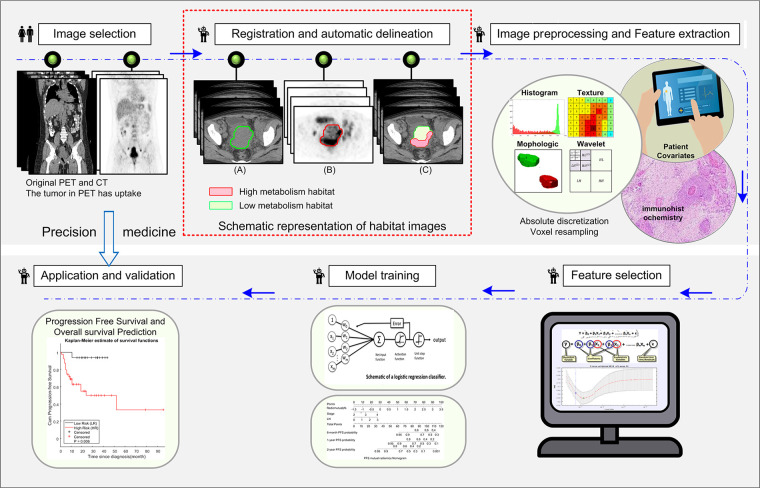

The workflow for radiomics analysis is shown in Figure 2. After registration using the open-source software ITK-SNAP (http://www.itksnap.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php) (27), the primary cervical tumors were semiautomatically segmented with an improved level-set method based on the gradient fields of PET and CT images (25) by a nuclear radiologist (Y.L., with 23 years of experience) who was blind to the clinical data. Details are shown in Appendix E3 and Figure E1 (supplement). On each tumor-restricted PET image, Otsu thresholding (28) was performed to automatically maximize interclass variance. Using the obtained threshold, the corresponding tumor of PET images was divided into high and low metabolic (SUV) regions (Figure 2, red box), representing distinct habitats. The masks of these two habitats were then mapped to the coregistered CT images, and two CT subregions were subsequently obtained. Therefore, four subregions of PET and CT images including PEThigh, PETlow, CThigh, and CTlow were included. Consequently, 1508 quantitative features (29) (364 whole-tumor PET features, 364 whole-tumor CT features, and 780 habitat imaging–based features) were extracted and normalized by transforming the data with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 (z scores), which are detailed in Appendices E4–E6 (supplement). For a subset of 50 patients, the entire feature extraction pipeline was repeated by Y.T. (10 years of experience in abdominal imaging) who was blind to the clinical data. This set was used to validate the reproducibility of the quantitative features.

Figure 2:

The radiomics workflow includes image selection, registration and automatic delineation, imaging preprocessing and feature extraction, feature selection, model training, and model application and validation. The part in the red square illustrates the habitat images obtained from PET images using Otsu method.

Feature Selection and Construction of the Radiomics Signature

The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression method (30) was used to select the most useful predictive features with nonzero coefficients and generate the radiomics signatures through a linear combination weighted by the corresponding coefficients. To improve the stability, the dimensions of the input data were reduced first according to the internal stability and predictive ability of the features, which is shown in Appendix E7 (supplement). The penalty parameter (l) in LASSO was selected using 10-fold cross validation by minimum mean cross-validated error. To investigate the added value of the habitat features, two different radiomics signatures were obtained with PET plus CT features (named as r-PFS and r-OS), and PET plus CT plus habitat features (named as rHab-PFS and rHab-OS).

Statistical Analysis

The Wilcoxon signed rank test and Fisher exact test were used for numerical and categorical variables, respectively, to assess the differences of clinical factors in the two institutions. To determine the association of the radiomics expression patterns with clinical characteristics, x2 test was used. The interclass correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the reproducibility of the feature extraction pipeline. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank test was performed on the high-risk and low-risk patient subgroups classified according to the optimal cutoffs identified by X-tile software (31) (Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn, http://x-tile.software.informer.com/) with the minimum P value on the training dataset. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models (backward step-down selection with Akaike information criterion as the stopping rule) (32), which were presented as radiomics nomograms, were used to assess the prognostic significance of radiomics signatures and other clinical characteristics (SUVmax, metabolic tumor volume, volume, age, grade, T stage, LN status, and 2018 FIGO stage). To quantify the discrimination performance, Harrell concordance index (C-index) was measured; meanwhile, calibration curves were generated to compare the predicted survival with the actual survival qualitatively (33).

Besides the clinically used 2018 FIGO staging system, another prediction model, constructed with only clinical characteristics, was also investigated using multivariable Cox analysis and compared with the radiomics nomogram model. In case of unavailable clinical information, a radiologic nomogram that only included the PET/CT image-based radiomics signature and LN status was used. The comparison of the different models was performed by evaluating the difference of the C-indexes using z test. Furthermore, net reclassification improvement (NRI) was also calculated to measure the improvement in 6-month, 1-year, 2-year, 4-year, and 5-year PFS and OS prediction yielded by radiomics signatures when added to clinical variables in multivariable Cox models. P value of less than .05 was regarded as significant, and statistical analyses were performed in R 3.5.1 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria) and MATLAB R2016b (Mathworks, Natick, Mass).

Results

Clinical Characteristics

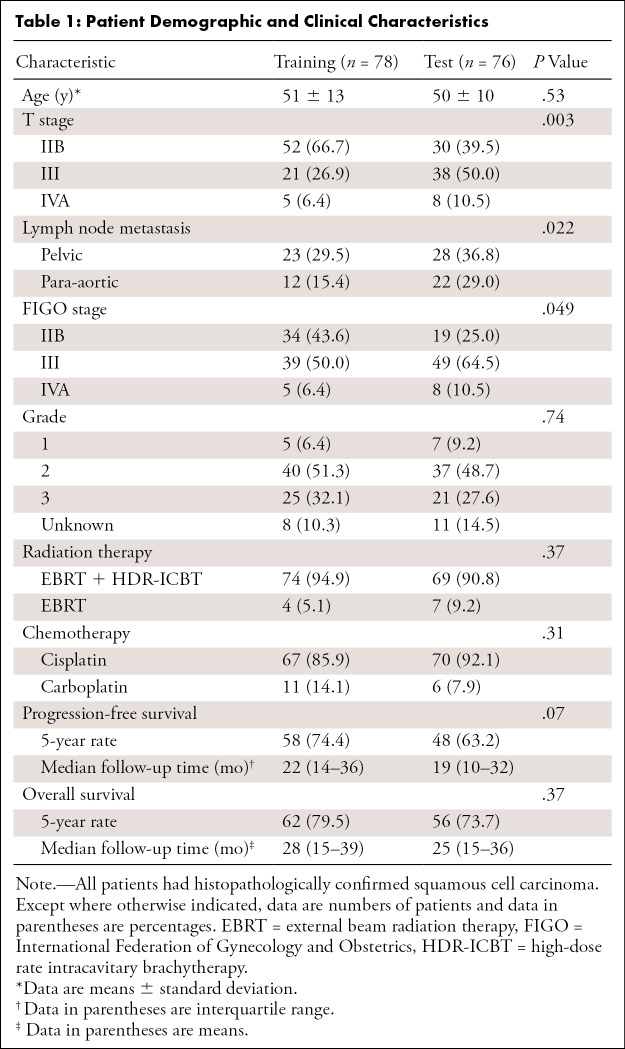

Among the 78 training patients from HLM, the mean age was 51 years ± 13 (standard deviation), with median PFS and OS of 22 and 28 months, respectively. For the 76 test patients from Institute CIH, the mean age was 50 years 6 10, with median PFS and OS of 19 and 25 months, respectively (Table 1). However, due to the discrepancy in prevalence rates of early screening between developed and developing countries, the T stage (P = .003) and LN status (P = .022) of the two cohorts were significantly different. Most training patients were diagnosed as stage II, while patients diagnosed as stage III accounted for the largest proportion in the test cohort. However, this could be adjusted for by regarding the T stage and LN status as important variables in the subsequent analysis.

Table 1:

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Feature Selection and Construction of the Radiomics Signature

The patterns of the extracted features were first investigated with unsupervised hierarchical clustering applied to both training and test datasets, shown in Figure E2a (supplement), which suggested that the training and test datasets expressed similar radiomics patterns. According to the x2 test, T stage (P = .045) and PFS (P = .015) were associated with the three clusters generated on the training cohort. T stage (P = .013), LN status (P = .032), PFS (P = .023), and OS (P = .034) were associated with the clusters on the test cohort. In more detail, clusters II and III were associated with higher stage (stages III and IV) and most recurrences and deaths. After dimensionality reduction according to each feature’s internal stability and predictive ability, three PET features, five CT features, and seven habitat features were fed into the LASSO method for PFS estimation; and three PET features, four CT features, and five habitat features were fed into the LASSO method for OS estimation. Finally, the features selected for the radiomics signatures are presented along with their calculation formulas in Appendix E8 (supplement), and the generated radiomics signatures were found significantly associated with T stage (training, P < .001; test, P < .001) and LN status (training, P < .001; test, P < .001) (Figure E2b [supplement]). Two detailed radiomics signatures of two patients at the same stage are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3:

Examples of detailed radiomics signatures. A, B, are the CT, PET, and fusion images of two patients at the same stage but with bad prognosis (progression-free survival [PFS] of 5 months, overall survival [OS] of 11 months, and stage IIIB) and good prognosis (PFS of 32 months, OS of 32 months, and stage IIIB), respectively. The red contours in the fusion images indicate the high metabolic habitat, while the rest of the region in the blue contour is the low metabolic habitat. The cutoffs (49.79, 16108, 48.88, 11021, 0.18, −0.19, −0.03, and −0.25) are obtained using X-tile software on the training dataset. The larger the radiomics signatures (r-PFS, r-OS, rHab-PFS, and rHab-OS), the higher the risk of progression or death. CMDvariance = difference variance feature calculated from co-occurrence matrix, LRHGE = long run high gray-level emphasis calculated from run-length matrix, r-OS = radiomic signature for OS obtained with PET plus CT features, r-PFS = radiomic signature for PFS obtained with PET plus CT features, rHab-OS = radiomic signature for OS obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features, rHab-PFS = radiomic signature for PFS obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features.

Prognostic Value of the Radiomics Signature

Univariable Cox regression analysis showed that the two radiomics signatures (r-PFS and r-OS, as well as rHab-PFS and rHab-OS) were significantly associated with PFS and OS in both training (PFS, P < .001; OS, P < .001) and test (PFS, P < .001; OS, P < .001) cohorts (Tables E1 and E2 [supplement]). The radiomics signatures that included habitat features, rHab-PFS and rHab-OS, achieved significantly higher C-indexes of 0.78 and 0.76 for PFS estimation and 0.83 and 0.78 for OS estimation in the training and test cohorts, respectively, compared with r-PFS and r-OS with C-indexes of 0.72 and 0.68 for PFS estimation (P = .004, z test) and 0.79 and 0.72 for OS estimation (P = .048, z test).

For the complete overread study, high interclass correlation coefficient of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.78, 0.94; P < .001) and 0.86 (95% CI: 0.76, 0.92; P < .001) were obtained for rHab-PFS and rHab-OS, respectively, which demonstrated the reproducibility of the feature extraction pipeline. Further, there were no significant differences between the two institutions for either signature (Figure E3 [supplement]), indicating the stability of the radiomics signatures. Hence, rHab-PFS and rHab-OS were used for the subsequent analyses.

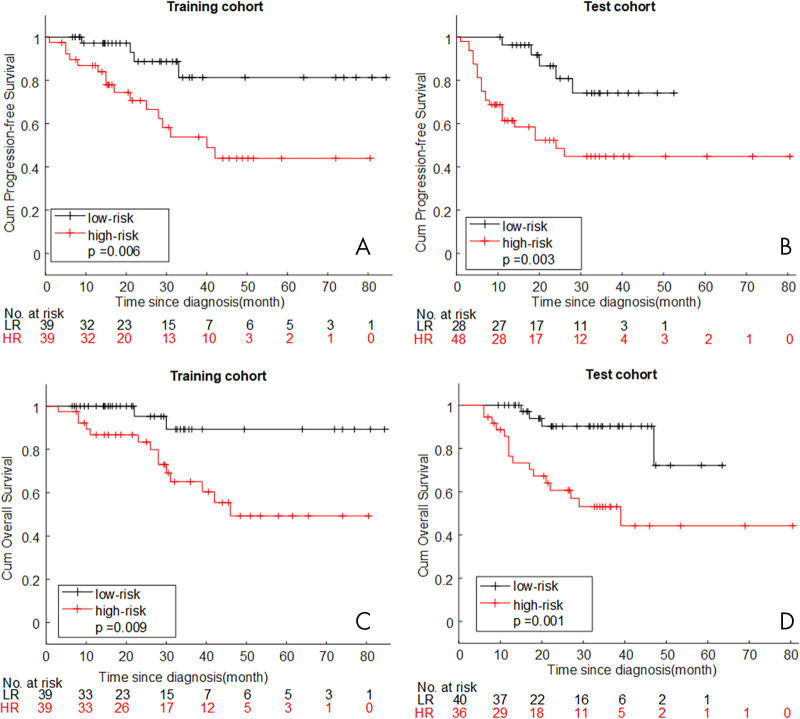

Through Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank test, patients with lower rHab-PFS (< −0.03) or rHab-OS (< −0.25) had significantly longer PFS and OS in the training (P = .006 for PFS and P = .009 for OS) and test (P = .003 for PFS and P = .001 for OS) cohorts, shown in Figure 4. Given that rHab-PFS and rHab-OS were significantly associated with T stage (P < .001, P < .001, respectively) and LN status (P < .001, P < .001, respectively), a stratified Kaplan-Meier analysis of patients with locally advanced cervical cancer with different T stage and LN status was performed. The results are presented in Figure E4 (supplement) and demonstrate that the radiomics signature remained a statistically significant prognostic predictor, especially in the later stage and LN metastatic subgroup of both cohorts.

Figure 4:

A, B, Kaplan-Meier curves for progression-free survival according to rHab-PFS. C, D, Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival according to rHab-OS. HR = high radiomics signature, LR = low radiomics signature, rHab-OS = radiomic signature for overall survival obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features, rHab-PFS = radiomic signature for progression-free survival obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features.

Compared with clinical risk factor (T stage), image-read factors (LN status), and FIGO staging system, which were significantly associated with PFS and OS in univariable Cox regression analysis (Tables E1 and E2 [supplement]), rHab-PFS and rHab-OS achieved highest C-indexes in PFS and OS estimation, respectively, in both training and test cohorts.

Importance of the Radiomics Signature in Individual PFS and OS Estimation

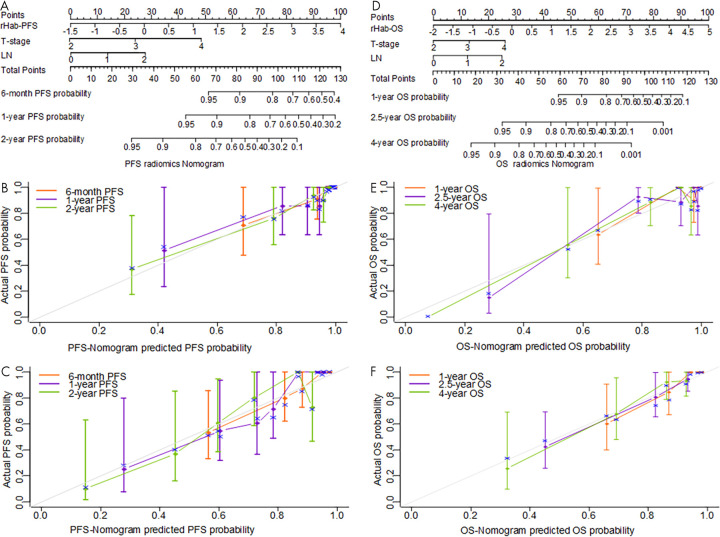

According to the univariable Cox regression analysis of the clinical characteristics (Tables E1 and E2 [supplement]), metabolic tumor volume (PFS: training: P = .059, test: P = .065; OS: training: P = .003, test: P = .086), volume (PFS: training: P = .043, test: P = .072; OS: training: P = .003, test: P = .079), T stage (PFS: training: P < .001, test: P = .001; OS: training: P < .001, test: P = .003), LN status (PFS: training: P < .001, test: P < .001; OS: training: P < .001, test: P = .004), and 2018 FIGO stage (PFS: training: P = .004, test: P < .001; OS: training: P = .006, test: P = .014) were all significantly associated with PFS and OS in both the training and test cohorts (Tables E1 and E2 [supplement]), whereas SUVmax, age, and grade were not. The further multivariable Cox regression analyses identified rHab-PFS, rHab-OS, T stage, and LN status as independent risk factors to predict PFS and OS (details shown in Table E3 [supplement]). These independent risk factors can be combined to construct radiomics nomograms as shown in Figure 5, A and D for PFS and OS prediction, respectively. As a comparison, clinical multivariable Cox regression models that included T stage and LN status were also trained as shown in Table E5 (supplement).

Figure 5:

A–C, Constructed radiomics nomogram used to estimate the risk of cancer progression along with the assessment of the model calibration and the corresponding calibration curves on the training and test cohorts. D–F, The constructed radiomics nomogram used to estimate the risk of cancer death along with the assessment of the model calibration and the corresponding calibration curves on the training and test cohorts. LN = lymph node, OS = overall survival, PFS = progression-free survival, rHab-OS = radiomic signature for overall survival obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features, rHab-PFS = radiomic signature for progression-free survival obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features.

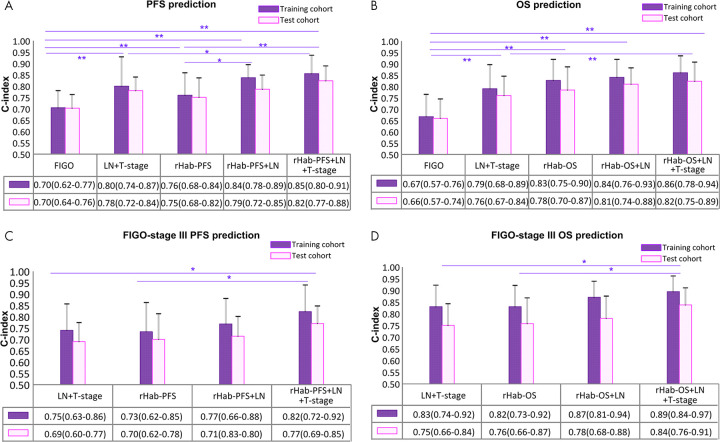

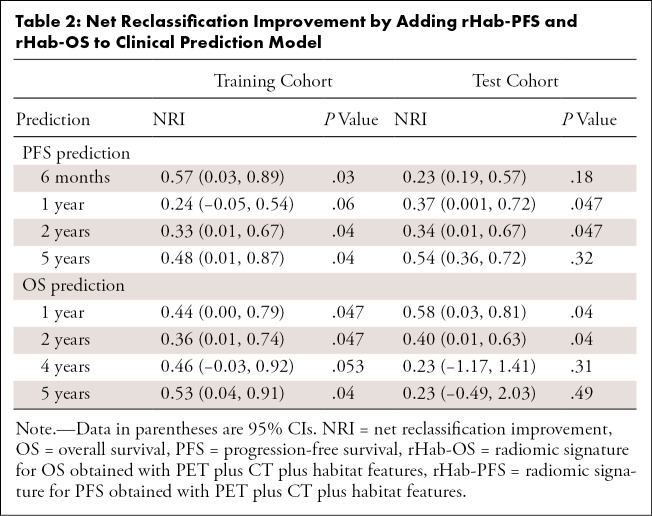

For PFS estimation, the PFS radiomics nomogram achieved significantly better discrimination performance with C-indexes of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.80, 0.91) and 0.82 (95% CI: 0.77, 0.88) in the training and test cohort, respectively, compared with single rHab-PFS (training, 0.76 [P = .016]; test, 0.75 [P = .021]), FIGO staging system (training, 0.70 [P = .001]; test, 0.70 [P = .002]), and clinical prediction model (training, 0.80 [P = .084]; test, 0.78 [P = .031]). Details are shown in Figure 6, A. Further, the inclusion of the radiomic signature in the clinical prediction model yielded significant NRIs (shown in Table 2) at 1-year and 2-year time point for the training and test cohort, respectively. At the 6-month and 5-year time point, although the NRIs were only significant in the training cohort, the addition of the radiomic signature still reclassifies patients more appropriately (NRI > risk 0) in the test cohort. Therefore, the radiomics nomogram model showed improved classification accuracy for PFS outcomes at different time points.

Figure 6:

The performance and the comparison of different models. A, B, Performance of the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) estimation of the whole training cohort and test cohort. C, D, Performance of the PFS and OS estimation of the subgroup of the patients with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage III. * = P < .05, ** = P < .01, C-index = Harrell concordance index, LN = lymph node, rHab-PFS = radiomic signature for PFS obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features, rHab-OS = radiomic signature for OS obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features.

Table 2:

Net Reclassification Improvement by Adding rHab-PFS and rHab-OS to Clinical Prediction Model

For OS estimation, the radiomics nomogram achieved significantly better discrimination performance with C-indexes of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.78, 0.94) and 0.82 (95% CI: 0.75, 0.89) in the training and test cohort, respectively, compared with single rHab-OS (training, 0.83 [P = .16]; test, 0.78 [P = .36]), FIGO staging system (training, 0.67 [P < .001]; test, 0.66 [P < .001]), and clinical prediction model (training, 0.79 [P = .049]; test, 0.76 [P = .05]). Details are shown in Figure 6, B. Further, the inclusion of the radiomic signature in the clinical prediction model could generate significant NRI obtained at 1-year, 2-year, 4-year, and 5-year time points in the training cohort, significant NRI at 1-year and 2-year time point, and high but not significant NRI at 4-year and 5-year time points in the test cohort, which further indicated the improved classification accuracy for OS outcomes. Similar results were observed in the FIGO stage III patients (Fig 6, C and D). Therefore, the radiomics signatures play an important role in PFS and OS estimation compared with commonly used 2018 FIGO staging system and clinical characteristics.

Qualitatively, from the calibration curves for the probability of progression and death at different time points on the training and test cohorts (Fig 5, B, C, E, and F), good agreements between the nomogram prediction and actual observation were observed. In cases where clinical information (T stage) was unavailable, two radiologic nomograms (Table E4 [supplement]) were trained based only on image-based factors (radiomics signatures and LN status), and achieved the C-indexes of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.78, 0.89) and 0.79 (95% CI: 0.72, 0.85) for PFS estimation and 0.84 (95% CI: 0.76, 0.93) and 0.81 (95% CI: 0.74, 0.88) for OS estimation in the training and test cohorts, respectively (Fig 6, A and B). Compared with the radiomics nomogram, the performance was a little decreased but not significantly. However, these models still significantly outperformed FIGO in the training (P = .004 for PFS, P < .001 for OS) and test (P = .027 for PFS, P = .002 for OS) cohorts.

Discussion

In this study, we developed and validated radiomics signatures from PET, CT, and habitat images for prognosis estimation of patients with locally advanced cervical cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy, which could stratify patients into low risk and high risk with significant differences in their PFS and OS. The combination of the radiomics signatures, T stage, and LN status into nomograms showed significantly better prognostic value than the FIGO staging system, which can further facilitate individualized PFS and OS estimation prior to initiation of chemoradiotherapy. Even without the clinical information, the alternative image-based radiologic nomograms could still achieve good PFS and OS prediction.

A number of PET/CT radiomics studies have proposed signatures for recurrence prediction and prognosis estimation in cervical cancer (11,12,34). However, these studies have extracted image-derived features independently from PET or CT images, which we have proven is inferior to fused information. To date, fused information from PET and CT images has only been explored for some subjective and qualitative descriptors (16–19). In this study, creating a habitat mask by projecting PET data onto the CT images allowed us to extract the interactive information from images of both modalities, which better distinguished the patients with different prognoses but showing similar PET (long run high gray-level emphasis calculated from run-length matrix) or CT (difference variance feature calculated from co-occurrence matrix) features. Quantitatively, compared with the PET plus CT radiomics signature, the inclusion of habitat features significantly improved the overall C-index from 0.68 to 0.76 (P = .004) for PFS and 0.74 to 0.80 (P = .048) for OS.

A biologic explanation for the better performance of the habitat-extracted features might come from the formulas for rHab-PFS and rHab-OS. The main selected habitat feature was a combination of a high metabolic PET region feature and low metabolic CT region feature, which suggested the high metabolic habitat of the tumor in PET images, usually reflecting the metabolism of the active tumor cells, was highly correlated with progression and death. Although possibly due in part to partial volume effects, it is notable that part of the low metabolic CT region was usually located in the boundary of the tumor, suggesting that heterogeneity of the tumor boundary, possibly caused by inflammation, in CT images is also important for the prognosis evaluation. Previous studies have shown that higher entropy at the edge of lung cancers contributed to a poorer prognosis (35).

When examining other features that contributed to the signatures, CT features also played a more important role for both PFS and OS estimation than the PET-derived features. Notably, CT is seldom used clinically for cervical cancer diagnosis, as cervical cancers generally show poor CT contrast. However, our quantitative results indicate that CT can be conducive to predict outcome of cervical cancer to chemoradiotherapy, indicating that radiomics analysis could identify subtle and relevant CT features. More generally, the features used in rHab-PFS and rHab-OS demonstrate that a larger, more heterogeneous, and more eccentric tumor corresponds to a much worse prognosis.

It is also notable that the training and test cohorts were from different hospitals in different countries with distinct image acquisition and reconstruction platforms. Nonetheless, using the models derived by training cohort, we successfully and significantly showed their utility on the independent testing cohort. This indicates that the derived radiomics model is robust and transportable. Furthermore, for prediction of OS, the Wilcoxon test between two institutions (P = .70) and the similar distribution shown in box plot suggest there was no significant difference between the different cohorts, which was consistent with Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showing similar OS (P = .37). For PFS, the box plot and Wilcoxon test showed the test cohort had quasi-significant higher rHab-PFS (P = .065), indicating that the test cohort has a larger risk of recurrence, which is also consistent with the result of the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showing the training cohort had quasi-significant longer PFS (P = .07). Therefore, the two radiomics signatures calculated from different institutions are robust, which indicates the potential of data-parallel distributed training.

The present study also possessed some limitations. The main limitation was the limited number of patients and inclusion of a large number of features. This was mitigated by validating the radiomics signatures on an external cohort with different acquisition protocols, and we are curating more data for future validation.

In conclusion, two effective and stable radiomics signatures combining PET, CT, and habitat features were identified and may serve as predictive prognostic markers of chemoradiotherapy for patients with locally advanced cervical cancer. Furthermore, the radiomics nomograms incorporating radiomics signatures, T stage, and LN status may have the potential to identify the patients who need more aggressive treatment in clinical practice, pending further validation with larger prospective cohorts.

APPENDIX

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES

W.M. and Y.L. contributed equally to this work.

Supported by U.S. Public Health Service research grants U01 CA143062 and R01 CA190105 (principal investigator R.J.G.).

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: W.M. disclosed no relevant relationships. Y.L. disclosed no relevant relationships. L.O.H. disclosed no relevant relationships. Y.T. disclosed no relevant relationships. Y.B. Activities related to the present article: disclosed grant to author’s institution from the NIH as funding received related to the study. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. R.W. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed money paid to author from Merck, Tesaro/GSK, Abbvie, Clovis Oncology, Astra Zeneca, Genentech, Legend Biotech, Mersana, J&J/Janssen, and Regeneron for advisory or scientific boards and personal fees; disclosed grants/grants pending to author’s institution and personal fees from Merck and Precision Therapeutics for investigator trials; disclosed money paid to author from Tesaro/GSK, Clovis Oncology, and Genentech as payment for lectures, including service on speakers bureaus; disclosed money paid to author from Research to Practice as payment for development of educational presentations; disclosed money paid to author from Ovation for stock/stock options; disclosed money paid to author for travel from Marker Therapeutics; disclosed money paid to author from Tesara/GSK for DSMB. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. N.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. J.T. disclosed no relevant relationships. R.J.G. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed money paid to author’s institution from HealthMyne for nonremunerated board membership and nonremunerated consultancy; disclosed money paid to author from HealthMyne for Series A and Founders’ stock/stock options; author is on board of advisors for HealthMyne; disclosed money paid to author’s institution from HealthMyne for in-kind support of developmental software. Other relationships: disclosed patent issued (USPTO 9,940,709) for Systems and Methods for Diagnosing Tumors in a Subject by Performing a Quantitative Analysis of Texture-based Features of a Tumor Object in a Radiological Image.

Abbreviations:

- C-index

- Harrell concordance index

- CIH

- Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences

- FDG

- fluorodeoxyglucose

- FIGO

- International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- HLM

- H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute

- LASSO

- least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- LN

- lymph node

- NCCN

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- NRI

- net reclassification improvement

- OS

- overall survival

- PFS

- progression-free survival

- rHab-OS

- radiomic signature for OS obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features

- rHab-PFS

- radiomic signature for PFS obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features

- SUV

- standard uptake value

References

- 1.Tefera B, Kerbo AA, Gonfa DB, Haile MT. Knowledge of Cervical Cancer and Its Associated Factors among Reproductive Age Women at Robe and Goba Towns, Bale zone, Southeast Ethiopia. Glob J Med Res 2016;16(1):24-31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuire S. World Cancer Report 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO Press, 2015. Adv Nutr; 2016;7(2):418–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koh WJ, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, et al. Cervical Cancer, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019;17(1):64–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatla N, Berek JS, Cuello Fredes M, et al. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;145(1):129–135 [Published correction appears in Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;147(2):279–280.]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuo K, Machida H, Mandelbaum RS, Konishi I, Mikami M. Validation of the 2018 FIGO cervical cancer staging system. Gynecol Oncol 2019;152(1):87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright JD, Matsuo K, Huang Y, et al. Prognostic Performance of the 2018 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Cervical Cancer Staging Guidelines. Obstet Gynecol 2019;134(1):49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollebecque A, Meyer T, Moore KN, et al. An open-label, multicohort, phase I/II study of nivolumab in patients with virus-associated tumors (CheckMate 358): Efficacy and safety in recurrent or metastatic (R/M) cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancers. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(15_suppl):5504. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mirpour S, Mhlanga JC, Logeswaran P, Russo G, Mercier G, Subramaniam RM. The role of PET/CT in the management of cervical cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;201(2):W192–W205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aerts HJ, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RT, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun 2014;5(1):4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucia F, Desseroit M, Miranda O, et al. PO-0721: Prediction of local recurrence using pretreatment 18FDG PET/CT radiomics features in cervical cancer. Radiother Oncol 2017;123:S378. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucia F, Visvikis D, Desseroit MC, et al. Prediction of outcome using pretreatment 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI radiomics in locally advanced cervical cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2018;45(5):768–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onal C, Reyhan M, Parlak C, Guler OC, Oymak E. Prognostic value of pretreatment 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in patients with cervical cancer treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2013;23(6):1104–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai C, Yen T, Ma S, Tsai C, Ng K, Chang T. SUV in pelvic lymph node is a significant prognostic factor in previously untreated squamous carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J Clin Oncol 2006;24(18_suppl):5051. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crivellaro C, Signorelli M, Guerra L, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT can predict nodal metastases but not recurrence in early stage uterine cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2012;127(1):131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukunaga H, Sekimoto M, Ikeda M, et al. Fusion image of positron emission tomography and computed tomography for the diagnosis of local recurrence of rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12(7):561–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamoto Y, Senda M, Okada T, et al. Software-based fusion of PET and CT images for suspected recurrent lung cancer. Mol Imaging Biol 2008;10(3):147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaarschmidt BM, Heusch P, Buchbender C, et al. Locoregional tumour evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck area: a comparison between MRI, PET/CT and integrated PET/MRI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2016;43(1):92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bar-Shalom R, Yefremov N, Guralnik L, et al. Clinical performance of PET/CT in evaluation of cancer: additional value for diagnostic imaging and patient management. J Nucl Med 2003;44(8):1200–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatenby RA, Grove O, Gillies RJ. Quantitative imaging in cancer evolution and ecology. Radiology 2013;269(1):8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chicklore S, Goh V, Siddique M, Roy A, Marsden PK, Cook GJ. Quantifying tumour heterogeneity in 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging by texture analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2013;40(1):133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farhidzadeh H, Chaudhury B, Zhou M, et al. Prediction of Treatment Outcome in Soft Tissue Sarcoma Based on Radiologically Defined Habitats. In: Hadjiiski LM, Tourassi GD, eds. Proceedings of SPIE: medical imaging 2015—computer-aided diagnosis. Vol 9414. Bellingham, Wash: International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2015; 94141U. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang YC, Ackerstaff E, Tschudi Y, et al. Delineation of Tumor Habitats based on Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MRI. Sci Rep 2017;7(1):9746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Napel S, Mu W, Jardim-Perassi BV, Aerts HJWL, Gillies RJ. Quantitative imaging of cancer in the postgenomic era: Radio(geno)mics, deep learning, and habitats. Cancer 2018;124(24):4633–4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mu W, Chen Z, Shen W, et al. A Segmentation Algorithm for Quantitative Analysis of Heterogeneous Tumors of the Cervix With 18F-FDG PET/CT. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2015;62(10):2465–2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mu W, Chen Z, Liang Y, et al. Staging of cervical cancer based on tumor heterogeneity characterized by texture features on (18)F-FDG PET images. Phys Med Biol 2015;60(13):5123–5139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yushkevich PA, Gerig G. ITK-SNAP: an intractive medical image segmentation tool to meet the need for expert-guided segmentation of complex medical images. IEEE pulse 2017;8(4):54-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otsu N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern B Cybern 1979;9(1):62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zwanenburg A, Vallières M, Abdalah MA, et al. The image biomarker standardization initiative: standardized quantitative radiomics for high-throughput image-based phenotyping. Radiology 2020;295(2):328-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedman J, Hastie T, Simon N, Tibshirani R. Package glmnet: Lasso and elastic-net regularized generalized linear models ver 4.0. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmnet/glmnet.pdf. Posted June 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, Rimm DL. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10(21):7252–7259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang YQ, Liang CH, He L, et al. Development and validation of a radiomics nomogram for preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(18):2157–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grossmann P, Stringfield O, El-Hachem N, et al. Defining the biological basis of radiomic phenotypes in lung cancer. eLife 2017;6:e23421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reuzé S, Orlhac F, Chargari C, et al. Prediction of cervical cancer recurrence using textural features extracted from 18F-FDG PET images acquired with different scanners. Oncotarget 2017;8(26):43169–43179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grove O, Berglund AE, Schabath MB, et al. Quantitative computed tomographic descriptors associate tumor shape complexity and intratumor heterogeneity with prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. PLoS One 2015;10(3):e0118261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

![Examples of detailed radiomics signatures. A, B, are the CT, PET, and fusion images of two patients at the same stage but with bad prognosis (progression-free survival [PFS] of 5 months, overall survival [OS] of 11 months, and stage IIIB) and good prognosis (PFS of 32 months, OS of 32 months, and stage IIIB), respectively. The red contours in the fusion images indicate the high metabolic habitat, while the rest of the region in the blue contour is the low metabolic habitat. The cutoffs (49.79, 16108, 48.88, 11021, 0.18, −0.19, −0.03, and −0.25) are obtained using X-tile software on the training dataset. The larger the radiomics signatures (r-PFS, r-OS, rHab-PFS, and rHab-OS), the higher the risk of progression or death. CMDvariance = difference variance feature calculated from co-occurrence matrix, LRHGE = long run high gray-level emphasis calculated from run-length matrix, r-OS = radiomic signature for OS obtained with PET plus CT features, r-PFS = radiomic signature for PFS obtained with PET plus CT features, rHab-OS = radiomic signature for OS obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features, rHab-PFS = radiomic signature for PFS obtained with PET plus CT plus habitat features.](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/7da9/8082355/29086ca97d7c/ryai.2020190218.fig3.jpg)