Abstract

The multisystem effects of SARS-CoV-2 encompass the thyroid gland as well. Emerging evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 can act as a trigger for subacute thyroiditis (SAT). We conducted a systematic literature search using PubMed/Medline and Google Scholar to identify cases of subacute thyroiditis associated with COVID-19 and evaluated patient-level demographics, major clinical features, laboratory findings and outcomes. In the 21 cases that we reviewed, the mean age of patients was 40.0 ± 11.3 years with a greater female preponderance (71.4%). Mean number days between the start of COVID-19 illness and the appearance of SAT symptoms were 25.2 ± 10.1. Five patients were confirmed to have ongoing COVID-19, whereas the infection had resolved in 16 patients before onset of SAT symptoms. Fever and neck pain were the most common presenting complaints (81%). Ninety-four percent of patients reported some type of hyperthyroid symptoms, while the labs in all 21 patients (100%) confirmed this with low TSH and high T3 or T4. Inflammatory markers were elevated in all cases that reported ESR and CRP. All 21 cases (100%) had ultrasound findings suggestive of SAT. Steroids and anti-inflammatory drugs were the mainstay of treatment, and all patients reported resolution of symptoms; however, 5 patients (23.8%) were reported to have a hypothyroid illness on follow-up. Large-scale studies are needed for a better understanding of the underlying pathogenic mechanisms, but current evidence suggests that clinicians need to recognize the possibility of SAT both in ongoing and resolved COVID-19 infection to optimize patient care.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Subacute thyroiditis, De Quervain’s thyroiditis, Viral thyroiditis

Introduction

Subacute thyroiditis (also called as De Quervain’s thyroiditis, viral thyroiditis, subacute granulomatous thyroiditis, or giant cell thyroiditis) is a self-limiting inflammatory disorder of the thyroid gland which usually follows or coexists with a viral infection [1]. The etiology of SAT has been linked to viral infections such as mumps, measles, rubella, coxsackie, and adenovirus, either through direct viral toxicity or inflammatory response against the virus [2, 3]. It generally presents in women with neck or jaw pain, tender thyroid gland, and systemic signs/symptoms [2]. As of February 3, 2021, WHO on its official website has reported more than 103 million documented cases of COVID-19 while the death toll is above 2.2 million. Efforts are being made to identify the endocrinological effects of COVID-19, and abnormalities of hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis have been reported [4]. The interplay between thyroid hormones and immune system along with the direct cytotoxic effect of the virus is proposed to play a role in these abnormalities, including subacute thyroiditis [4]. The increasing evidence of SAT during or after the COVID-19 infection has been reported in various published cases [5–17], which highlights the concern that physicians ought to consider COVID-19 (ongoing or previous) as an etiological factor/trigger in patients presenting with subacute thyroiditis. This is especially important amidst the ongoing pandemic or even in the future as physicians encounter SARS-CoV-2. All these factors, coupled with lack of a published systematic review on this topic, encouraged us to undertake this write-up.

Methods

Search Strategy

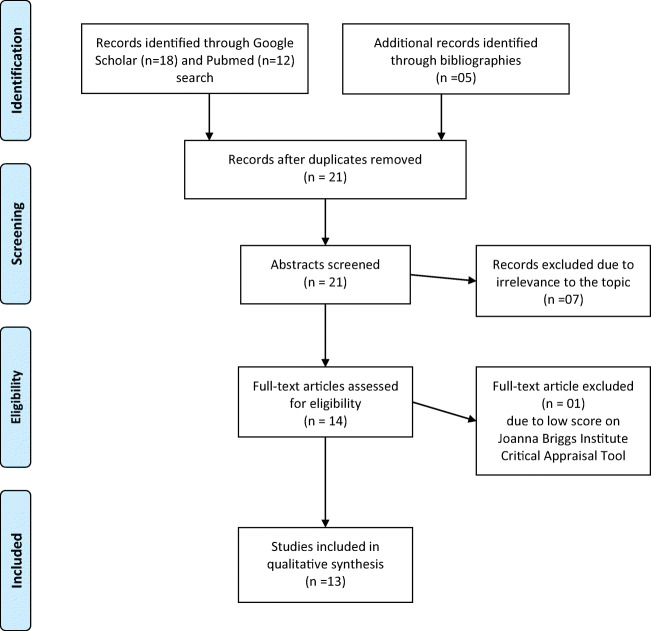

Online databases including PubMed/Medline and Google Scholar were searched for articles published until February 3, 2021. Search strategy followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines by using keywords like the following: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Subacute Thyroiditis, De Quervain’s Thyroiditis, and Viral Thyroiditis. All studies, regardless of time, language, and country of publication, and all types of research articles were scrutinized. The bibliographies of individual case reports and case series were also scrutinized to find any relevant cases. The final available references were downloaded into an EndNote library. The complete strategy is outlined in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Study Selection

The relevant published articles on this topic were mainly case reports and case series. Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tool [18] was employed by two authors independently to assess the quality of all case reports and case series. Both the authors engaged in discourse to reach one consensus score for each article. One case report was translated from Portuguese into English via Google Translator, but it was excluded due to a poor score on Critical Appraisal. All the other case reports and case series included in the final analysis were in English language. Data were curated and organized in the form of two tables each for case reports and case series. One table focused on patient demographics, clinical features, treatment(s), and follow-up/outcome. The other table focused on lab investigations and imaging results. Continuous variables were presented as means ± standard deviations, and categorical variables were presented as absolute values and percentages. Microsoft Excel was used for data extraction and statistical analysis for this study.

Results

Our search identified 30 articles; 9 were excluded due to duplication, and 7 articles on COVID-19 were excluded because they did not address subacute thyroiditis and 1 was excluded because it scored low on Critical Appraisal. Finally, 13 articles—11 case reports and 2 case series [5–17]—were included in the final analysis. Since 10 patients were described in the two case series, individual data from 21 total patients is described here, in the form of 2 tables each for case reports (Tables 1 and 3) and case series (Tables 2 and 4). The mean age of patients was 40.0 ± 11.3 years (range 18–69 years). Out of the 21 patients, 15 were females (71.4%) and 6 were males (28.6%). Most cases were reported in Italy (n = 7; 33.3%) and Iran (n = 6; 28.6%), 2 in the USA (9.5%) and Turkey (9.5%) each. One case (4.8%) each was reported in Singapore, Mexico, the Philippines, and India. Out of the 21, 9 reported a contact/travel history (42.9%), 4 reported no contact history, whereas the remaining studies did not mention whether or not exposure had occurred. Only 2 reports mentioned a comorbidity, with one patient having long-standing diabetes, and 1 having asthma. One patient had a family history of thyroid disease, whereas 2 patients had a goiter long before the onset of any symptoms.

Table 1.

Demographics, clinical presentation, course, and outcome of COVID-19-associated subacute thyroiditis (review of case reports)

| Author, year | Reported country | Age (years), sex (M/F) | Personal/family history of thyroid or non-thyroid disease | Travel/contact history | Presenting complaints | COVID-19 infection status | Time from COVID-19 illness to SAT symptoms (days) | Relevant clinical course (if any) | Hyperthyroid symptoms | Examination | SAT treatment | Follow-up | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asfuroglu Kalkan, 2020 | Turkey | 41 F | None | None | Fever and neck pain | Ongoing, asymptomatic | - | None | - | Tender thyroid and left TMJ on palpation, erythematous pharyngitis, lungs clear on auscultation | Hydroxychloroquine and Prednisone | - | Improved |

| Mattar, 2020 | Singapore | 34 M | Positive family history of thyroid disease | None | Fever, dry cough, headache, and anosmia | Ongoing, symptomatic | ~ 9 | On the 9th day of illness, developed neck pain and tachycardia | Tachycardia | Diffuse asymmetric goiter, tender thyroid, enlarged cervical nodes, lungs clear on auscultation | Prednisone and beta-blocker | 2 days: symptom improvement10 weeks: complete recovery with normal TFTs | Recovered |

| Campos-Barrera, 2020 | Mexico | 37 F | None | - | Severe neck pain radiating to right jaw/ear, fatigue | Past/resolved | ~ 30 | 1 month ago developed odynophagia and anosmia, resolved completely on treatment | - | Moderately enlarged tender thyroid gland and neck adenopathies | - | 1 month: asymptomatic, but lab tests were still relevant for anemia, thrombocytopenia, high ESR, and low TSH | Asymptomatic |

| Ippolito, 2020 | Italy | 69 F | Long-standing non-toxic nodular goiter with a dominant benign nodule in the right lobe | - | Mild fever, cough, and dyspnea | Ongoing, symptomatic | ~ 5 | 5 days after the diagnosis of COVID-19, she developed hyperthyroid symptoms with no neck pain, but patient was on pain killers | Insomnia, palpitations, agitation | - | Methimazole and steroids |

Thyrotoxicosis worsened with methimazole initially 10 days: all labs and symptoms improved with steroids |

Recovered |

| Khatri, 2020 | USA | 41 F | SVT treated with ablation, anxiety, depression, anemia, surgically corrected scoliosis, and GERD | - | Odynophagia, worsening pain and swelling of anterior neck | Past/Resolved | ~ 30 | 4 weeks prior, experienced several days of fever, cough, and coryza, tested positive for SAR-COV-2, resolved with treatment after 5 days | 6-kg unintentional weight loss, fatigue, alopecia, heat intolerance, irritability, headaches, bilateral hand tremors, and palpitations | Tender thyroid, lungs exam normal | Ibuprofen and prednisone |

1 week: improved TFTs on 1 week follow-up 45 days: complete resolution |

Recovered |

| Maris, 2020 | Philippines | 47 F | Asthma | - | Anterior neck pains, radiating to the right submandibular region | Ongoing, asymptomatic | - | Left-sided anterior neck pains and swelling 7 weeks ago, resolved by Mefenamic acid and recurred 2 weeks before presentation | None | Right thyroid lobe and isthmus diffusely enlarged and tender | Mefenamic acid, shifted to celecoxib due to epigastric pains. Oral hydroxychloroquine and intravenous ceftriaxone |

Day 10 of admission: COVID-19 negative, discharged 1 month of admission: full resolution of symptoms 8 weeks after admission: sluggishness, hair thinning Repeat TFTs showed overt hypothyroidism, started on levothyroxine |

Hypothyroid |

| Guven, 2020 | Turkey | 49 M | None | None, none | Sore throat, swallowing difficulty, and high fever | Past/resolved | ~ 10 | 10 days prior, admitted due to cough and shortness of breath, tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, symptoms improved with treatment and discharged few days later | - | Swollen and tender neck on palpation; tonsils hyperemic | Methylprednisolone | 1 week: asymptomatic. | Recovered |

| Chong, 2020 | USA | 37 M | - | - | Anterior neck pain, fatigue, and chills | Past/resolved | ~ 30 | 1 month prior developed flu-like illness involving productive cough, fever, chills, and dyspnea, was self-quarantined at home, symptoms resolved after a week of supportive care | Palpitation, heat intolerance, anorexia, and unintentional weight loss | Non-enlarged thyroid gland diffusely tender to palpation, postural tremors, brisk reflexes, palmar warmth and erythema | Oral aspirin for his neck pain together with propranolol |

1 week: symptoms improved 3 weeks later: hypothyroidism, oral levothyroxine started. Oral aspirin and propranolol discontinued Few weeks later: improvement in his symptoms. Repeat TFTs showed slightly elevated TSH, but normal fT4 and total T3. Oral levothyroxine continued for 6 weeks. |

Hypothyroid |

| Brancatella, 2020 | Italy | 18 F | None | COVID-19-positive father contact | Sudden fever, fatigue, palpitations, and anterior neck pain radiating to the jaw | Past/resolved | ~ 16 | Tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 2 days after contact, developed rhinorrhea and cough, recovered completely in 4 days without treatment | Fatigue, palpitations | Thyroid gland slightly tender and enlarged | Prednisone |

2 days: neck pain and fever disappeared within ~ 2 weeks: asymptomatic with normal labs |

Recovered |

| Ruggeri, 2020 | Italy | 43 F | None | - | Pain and tenderness in the anterior cervical region, fatigue, tremors, and palpitations | Past/ resolved | ~ 42 | Developed fever, rhinorrhea, painful swallowing, cough, hoarseness and conjunctivitis after which she tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, recovered rapidly without treatment but a low-grade fever persisted | Tremors, anxiety, fatigue, and palpitations | Mild tremors of the extremities, diffuse goiter, enlarged and tender cervical and submandibular lymph nodes | Prednisone |

2 weeks: improvement in labs and symptoms 4 weeks: asymptomatic, with labs normalized |

Recovered |

| Chakraborty, 2020 | India | 58 M | Diabetic for the last 10 years, on regular oral antihyperglycemics | None, none | Pain in his throat accompanied by a low-grade fever | Ongoing | - | None | Tachycardia, increased stool frequency | Tender swelling with firm consistency in the lower part of the front of neck, with well-defined margins, resembling a diffusely enlarged thyroid | Analgesics, favipiravir, azithromycin along with zinc tablets and vitamin C capsules; oral prednisolone and propranolol |

Initial recovery, followed by hypothyroidism Started on oral levothyroxine supplementation with periodic monitoring of TFTs |

Hypothyroid |

M male, F female, SAT subacute thyroiditis, SVT supraventricular tachycardia, GERD gastroesophageal reflux disease, TMJ temporomandibular joint, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, TFTs thyroid function tests, FT4 free T4, (-) data not reported

Table 3.

Diagnostics and laboratory investigations of COVID-19-associated subacute thyroiditis (review of case reports)

| Author, year | COVID-19 diagnosis | Chest X-ray/CT chest | Thyroid ultrasound/imaging | ESR (mm/h) | CRP (mg/L) | Baseline lab values | TFTs | Thyroid antibodies (TgAb, TPOAb, and TRAb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asfuroglu Kalkan, 2020 | RT-PCR | Normal | Relative diffuse decrease of vascularity and heterogeneous parenchyma | 134 | 101 | WBCs elevated |

TSH (low) FT3 (high) FT4 (high) |

Negative |

| Mattar, 2020 | RT-PCR | Normal | Enlarged thyroid gland with heterogeneous echotexture | - | 11.3 | Normal except mildly elevated WBC count after tachycardia onset |

TSH (low) FT4 (high) FT3 (high) |

Negative |

| Campos-Barrera, 2020 | RT-PCR | - | Thyroid iodine scan showed no radioactive iodine uptake | 72 | 66 | Anemia (Hb10.4 g/dL), normal platelet and WBCs |

TSH undetectable FT4 (high) |

Negative |

| Ippolito, 2020 | RT-PCR | Bilateral ground-glass areas | Enlarged hypoechoic thyroid with decreased vascularity on U/S, no uptake on radioiodine scan | - | - | - |

TSH (low) FT4 (high) FT3 (high) |

Negative |

| Khatri, 2020 | RT-PCR | Normal | Heterogeneous thyroid gland with bilateral patchy ill-defined hypoechoic areas | 107 | 36.4 | Anemia (Hb 9.1 g/dL), normal platelet and WBCs | TSH (low) | TPOAb + |

| Maris, 2020 | RT-PCR | Right lower lobe pneumonia | Slightly enlarged right thyroid lobe, with ill-defined hypoechogenicity and normal vascularity in both lobes | - | 50.9 |

TSH (low) FT4 (normal) Total T3 (normal) |

Negative | |

| Guven, 2020 | RT-PCR | The right lung, upper lobe and lower lobe, superior segment reticulonodular density increases, ground glass opacities | Parenchyma is characterized by heterogeneous, patchy infiltrations, and hypoechoic areas observed in both thyroid lobes | 80 | 76.9 | Elevated WBCs, high neutrophils, low Hb |

TSH (low) FT4 (high) FT3 (normal) |

Negative |

| Chong, 2020 | RT-PCR | - | Diffusely heterogeneous echotexture | 31 | 14 | Normal |

TSH (low) FT4 (high) Total T3 (high) |

Negative |

| Brancatella, 2020 | RT-PCR | - | Multiple diffuse hypoechoic areas | 90 | 101 | WBCs mildly elevated |

TSH (low) FT4 (high) FT3(high) Tg: detected (low level) |

TgAb + |

| Ruggeri, 2020 | IgM and IgG SARS-CoV-2 | Normal | Diffusely enlarged and hypoechogenic thyroid gland; thyroid scintigraphy showed markedly reduced 99mTc-perthecnetate uptake in the gland | - | - | - |

TSH (low) FT3 (high) FT4(high) Tg (high), |

Negative |

| Chakraborty, 2020 | RT-PCR | - | Diffuse bilateral enlargement of thyroid with hypoechogenicity and increased vascularity on color Doppler and a solitary nodule in each lobe; poor and patchy radiotracer uptake on radionuclide thyroid scan with technetium-99m | 110 | 16.6 | Normal |

TSH (low) Serum T3 (high) Serum T4 (high) |

Negative |

ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP C-reactive protein, WBCs white blood cells, TFTs thyroid function tests, Tg thyroglobulin, FT3 free T3, FT4 free T4, TgAb thyroglobulin autoantibodies, TPOAb thyroid peroxidase antibody, TRAb TSH receptor antibody, (-) data not reported

Table 2.

Demographics, clinical presentation, course, and outcome of COVID-19-associated subacute thyroiditis (review of case series)

| Author, year; reported country | Patient number | Age (years), sex (M/F) | Personal/family history of thyroid or non-thyroid disease | Travel/contact history | Presenting complaints | COVID-19 infection status | Time from COVID-19 illness to SAT symptoms (days) | Relevant clinical course (if any) | Hyperthyroid symptoms | Examination | SAT treatment | Follow-up | Ooutcome |

| Sohrabpour, 2020; Iran | 1 | 26 F | - | History of travel to high-prevalence coronavirus area | Fever, fatigue, palpitations, and anterior neck pain | Past/resolved | ~ 30 | 1 month prior, developed self-limited dry cough lasting for 1 week | Fatigue, palpitations | Tender and slightly enlarged thyroid gland. | Prednisolone | After 1 week, the symptoms disappeared, and after 1 month thyroid function tests were normal. | Recovered |

| 2 | 37 F | - | Nurse at COVID-19 center; family member hospitalized for COVID-19 pneumonia within 2 weeks | Fever, fatigue, palpitations, and anterior neck pain | Past/resolved | ~ 30 | 1 month ago, developed myalgia lasting for a few days | Fatigue, palpitations | Tender and slightly enlarged thyroid gland | Prednisolone | After 1 week, the symptoms disappeared and after 1 month thyroid function tests were normal | Recovered | |

| 3 | 35 M | - | History of travel to high-prevalence coronavirus area | Fever, fatigue, palpitations, and anterior neck pain | Past/resolved | ~ 30 | None | Fatigue, palpitations | Tender and slightly enlarged thyroid gland | prednisolone |

1 week: asymptomatic 1 month: TFTs were normal |

Recovered | |

| 4 | 41 F | - | Family member hospitalized for COVID-19 pneumonia within 2 weeks | Fever, fatigue, palpitations, and anterior neck pain | Past/resolved | ~ 30 | 1 month ago, developed low-grade fever and mild myalgia lasting for a few days | Fatigue, palpitations | Tender and slightly enlarged thyroid gland | Prednisolone |

1 week: asymptomatic 1 month: TFTs were normal |

Recovered | |

| 5 | 52 M | - | History of travel to high-prevalence coronavirus area and family member hospitalized for COVID-19 pneumonia within last 2 weeks | Fever, fatigue, palpitations, and anterior neck pain | Past/resolved | ~ 30 | 1 month ago, developed low-grade fever, dry cough, and mild myalgia lasting for a few days | Fatigue, palpitations | Tender and slightly enlarged thyroid gland | Prednisolone |

1 week: asymptomatic 1 month: TFTs were normal |

Recovered | |

| 6 | 34 F | - | Nurse at COVID-19 center | Fever, fatigue, palpitations, and anterior neck pain | Past/resolved | ~ 30 | None | Fatigue, palpitations | Tender and slightly enlarged thyroid gland | Prednisolone |

1 week: asymptomatic 1 month: TFTs were normal. |

Recovered | |

| Brancatella, 2020; Italy | 1 | 38 F | None | - | Neck pain, fever, palpitations, asthenia, anorexia | Past/resolved | ~ 16 | Tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 16 days ago because of suggestive symptoms, recovered and tested negative few days later | Palpitations | - | Prednisone | 8 days after SAT presentation: atrial Fibrillation treated with cardioversion ~ 1.5-month follow-up: asymptomatic with normal TFTs | Recovered |

| 2 | 29 F | None | Contact with 2 COVID-19-positive individuals | Neck pain, fever, palpitations, asthenia, sweating | Past/resolved | ~ 30 | Quarantined post-contact, showed mild rhinorrheathat resolved within a few days | Palpitations | - | Prednisone and propranolol | 2 weeks: asymptomatic, inflammatory markers were in the normal range, whereas TFTs consistent with subclinical hypothyroidism | Hypothyroid | |

| 3 | 29 F | Small, nontoxic diffuse goiter | - | Neck pain, palpitations, sweating | Past/resolved | ~ 36 | History of mild COVID-19 symptoms ~ 1 month ago | Palpitations, tachycardia | - | Ibuprofen | 2 weeks: asymptomatic, inflammatory markers were in the normal range, whereas TFTs consistent with subclinical hypothyroidism, started on levothyroxine | Hypothyroid | |

| 4 | 46 F | None | Husband had been hospitalized for COVID-19 | Neck pain, fever, palpitations, asthenia, insomnia, anxiety, weight loss | Past/resolved | ~ 20 | Tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 post-contact, developed symptoms of mild COVID-19 that lasted about 2 weeks, however swab remained positive | Palpitations, weight loss, insomnia, anxiety | - | Prednisone | 2 weeks: asymptomatic | Recovered |

M male, F female, SAT subacute thyroiditis, TFTs thyroid function tests, (-) data not reported

Table 4.

Diagnostics and laboratory investigations of COVID-19-associated subacute thyroiditis (review of case series)

| Author, year | Patient no. | COVID-19 Dx | Chest X-ray/CT chest | Thyroid ultrasound/imaging | ESR (mm/h) | CRP (mg/L) | Baseline lab values | TFTs | Thyroid antibodies (TgAb, TPOAb, and TRAb) |

| Sohrabpour, 2020 | 1 | IgM and IgG SARS-COV-2 | Normal | Bilateral hypoechoic areas in thyroid gland | 70 | 28 | WBCs elevated | TSH (low)FT3(high)FT4 (normal) | - |

| 2 | IgM and IgG SARS-COV-2 | Normal | Bilateral hypoechoic areas in thyroid gland | 56 | 38 | WBCs elevated | TSH (low)FT3 (high)FT4 (high) | - | |

| 3 | IgM and IgG SARS-COV-2 | Normal | Bilateral hypoechoic areas in thyroid gland | 45 | 18 | WBCs normal | TSH (low)FT3 (high)FT4 (high) | - | |

| 4 | IgM and IgG SARS-COV-2 | Normal | Bilateral hypoechoic areas in thyroid gland | 83 | 43 | WBCs elevated | TSH (low)FT3 (high)FT4 (high) | - | |

| 5 | IgM and IgG SARS-COV-2 | Normal | Bilateral hypoechoic areas in thyroid gland | 76 | 51 | WBCs elevated | TSH (low)FT3 (high)FT4 (high) | - | |

| 6 | IgM and IgG SARS-COV-2 | Normal | Bilateral hypoechoic areas in thyroid gland | 39 | 23 | WBCs elevated | TSH (low)FT3 (high)FT4 (normal) | - | |

| Brancatella , 2020 | 1 | RT-PCR | - | Neck ultrasound: increased thyroid volume (20 mL) with bilateral diffuse hypoechoic areas and absent vascularization at color Doppler ultrasonography | 74 | 11.2 | - | TSH (low)FT3 (high)FT4 (high)Tg: detectable | Negative |

| 2 | IgG SARS-CoV-2 | - | Neck ultrasound: increased thyroid volume (22 mL) with bilateral diffuse hypoechoic areas and absent vascularization at color Doppler ultrasonography. Thyroid scintiscan: absent uptake | 110 | 7.9 | - | TSH (low)FT3(high)FT4 (high)Tg: detectable | Negative | |

| 3 | IgM SARS-CoV-2 (borderline) | - | Neck ultrasound: increased thyroid volume (25 mL) with bilateral diffuse hypoechoic areas | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 4 | RT-PCR | - | Neck ultrasound: increased thyroid volume (18 mL) with bilateral diffuse hypoechoic areas and absent to mild vascularization at color Doppler ultrasonography | - | 8 | - | TSH (low)FT3 (high)FT4 (high) | Negative |

ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP C-reactive protein, WBCs white blood cells, TFTs thyroid function tests, Tg thyroglobulin, FT3 free T3, FT4 free T4, TgAb thyroglobulin autoantibodies, TPOAb thyroid peroxidase antibody, TRAb TSH receptor antibody, (-) data not reported

Mean days between the start of COVID-19 illness and the appearance of SAT symptoms were 25.2 ± 10.1 (minimum 5 days and maximum 42 days). Five patients had ongoing COVID-19, whereas the infection had resolved in 16 patients before onset of SAT symptoms. COVID-19 diagnosis was made by RT-PCR swabs in 12 patients (57.1%), whereas in 9 cases (42.9%) with no current symptoms, no previous RT-PCR, or a negative current RT-PCR, a past COVID-19 illness was confirmed by the presence of IgG/IgM against SAR-COV2 in the patients’ blood. Out of the 13 people who had a chest X-ray/CT chest at presentation for SAT, only 3 showed abnormalities (21.3%).

Fever and neck pain were the most common presenting complaints with each being present in 17 out of 21 patients (81%). Other complaints included fatigue, palpitations, odynophagia, sweating, and throat pain. Out of the 16 reports that mentioned neck examination, a tender thyroid was found in all 16 patients (100%). Out of the 21 patients, 17 mentioned (94.4%) the presence of hyperthyroid symptoms like fatigue and palpitations, 1 mentioned absence of such symptoms, and 3 reports did not mention anything in this regard. Out of the 21, 15 cases reported ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) values which were high in all 15 patients (100%), with a mean of 78.5 ± 28.8 mm/h. Eighteen cases reported CRP (C-reactive protein) values, and it was elevated in all 18 (100%), with an average 39.0 ± 30.3 mg/L. Deranged TFTs (thyroid function tests) were seen in all patients, with each case having low TSH, and either high T3 or high T4 or both. Serum thyroglobulin was detectable in only 3 patients. Antithyroid antibodies were only reported positive in 2 patients, one being TPO-Ab (thyroid peroxidase antibody) and the other one being TgAb (thyroglobulin antibodies). All 21 cases (100%) had abnormal thyroid ultrasounds suggestive of SAT.

Twenty case reports discussed the medications of their patients; 18 out of these were administered steroids while others were given hydroxychloroquine, ibuprofen, methimazole, or only oral aspirin. Four of these were also given beta-blockers for controlling hyperthyroid symptoms. All patients recovered a few days after treatment; however, 5 patients were reported to have developed hypothyroid features/TFTs on follow-up after resolution of SAT symptoms.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of subacute thyroiditis (SAT) in COVID-19 patients. The term thyroiditis literally means thyroid inflammation. Most thyroidologists classify thyroiditis into (a) infectious thyroiditis (includes all forms of infection, except viral); (b) subacute thyroiditis; (c) autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Grave’s disease); and (d) Riedel’s thyroiditis [3]. Among all types of thyroiditis, subacute thyroiditis has been most strongly linked to viral infections in the literature [3]. The viral particles presumed to be of influenza or mumps were first demonstrated in the follicular epithelium of a patient suffering from subacute thyroiditis [19], and multiple viruses have been implicated as a trigger for subacute thyroiditis since then. Some of them include mumps, measles, rubella, influenza, coxsackie, adenovirus, varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis E, and HIV [2, 3, 20]. In most patients, a typical viral prodrome of malaise, myalgias and fatigue is also seen clinically. [21] A variety of case reports and case series have emerged over the last year suggesting that COVID-19 virus may also act as a possible trigger for SAT, either during the infection or after its resolution. While large-scale clinical data needs to be reviewed before making strong comments, the recurring and consistent evidence from the recognition of this virus to date suggests that COVID-19 may be another virus that merits the list of viral culprits in subacute thyroiditis.

SAT typically presents as pain localized to the anterior of the neck that may radiate up to the jaw or ear on either side, low-grade fever, fatigue, and mild thyrotoxic/hyperthyroid symptoms [2, 22–26]. Tenderness on palpation and enlarged size of the gland are some of the cardinal signs. Laboratory findings suggest hyperthyroid etiology (suppressed TSH, low free T4, and poor or no thyroid uptake), and thyroid ultrasound shows characteristic findings of poorly defined hypoechoic areas with a heterogeneous echo pattern [27–29]. Inflammatory markers like ESR and CRP are typically elevated. The disease may have a triphasic clinical course of hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and return to normal thyroid function. The hypothyroid phase, however, may last for months until the patient becomes euthyroid [24–26]. Most of the cases we reviewed presented with findings consistent with the above mentioned clinical features and investigations. Majority of the patients presented with complaints of anterior neck pain and fever, while some patients also presented with generalized fatigue, sore throat, cough, and odynophagia. In a total sample of 21, 16 patients (76%) gave a positive history of a previous COVID-19 infection confirmed either by a previous RT-PCR or a positive antibody test (IgM/IgG). The remaining 24% developed SAT during ongoing COVID-19 infection; however, two patients [5, 12] had an asymptomatic infection which was only confirmed via RT-PCR after they presented with SAT features.

It is believed that SARS-CoV-2 can affect the thyroid function in multiple ways. The three reported effects of the virus are (a) thyrotoxicosis (either subacute/painful thyroiditis or painless/atypical thyroiditis); (b) hypothyroidism (central or primary); and (c) nonthyroidal illness syndrome (previously known as euthyroid sick syndrome) [4]. This suggests that the effects of the virus on thyroid gland are highly variable and it is difficult to predict the abnormalities in thyroid function tests (TFTs). However, when studying the complication of subacute thyroiditis in COVID-19 alone, a strikingly similar pattern in terms of presentation, TFTs and outcome is observed.

Cytokine storm syndrome—a term used to describe the detrimental effects of hypercytokinemia on human cells—has been well described in the literature as the cause of thyroid problems [30]. While it is well documented that this storm is the cause of nonthyroidal illness syndrome seen in COVID-19 patients, at present there is little evidence to suggest the direct thyroid cytotoxic effect of cytokines, at least in humans [30, 31]. Immune-mediated post-viral inflammatory reaction, involving both the adaptive and innate immune systems, has also been described in the literature as a cause of thyroid problems [32, 33]. This mechanism might be responsible for the post-infection SAT observed in the majority of patients described here too.

Among the many possible mechanisms, direct viral damage remains the most reliable evidence to date. The molecular interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with ACE-2 and TMPRSS2 receptor is required for entry into the human cells [34–36] and recent work by Rotondi et al. and Lazartigues et al. demonstrated the presence of ACE-2 and TMPRSS2 mRNA in thyroid cells [37, 38]. This receptor-virus interaction is similar to previously described viruses of the same family, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV [39, 40]. The abundance of these receptors in thyroid [41] compared to other tissues (small intestine, heart, adipose) potentially explains the subacute thyroiditis associated with SARS-CoV-2, hence strengthening the documented mechanism of direct viral injury in SAT. Moreover, the structural proximity of the virus-laden superior airway to the thyroid gland may play some role as well [42]. This mechanism—direct follicular cell damage leading to spillage of thyroid hormones into plasma—probably explains the predominant thyrotoxic clinical picture (palpitations, tachycardia, insomnia, anxiety, etc.) in more than ¾ and thyroid function tests suggesting hyperthyroid etiology in 100% of the cases. It has also been hypothesized that drugs used in COVID-19, especially glucocorticoids and low molecular weight heparin, may also damage the gland and affect thyroid function [43]. While this mechanism might play a role in thyroid abnormalities, there is not enough evidence to support it in our review because not all patients described here received steroids and heparin for COVID-19 infection.

In the cases we reviewed, more than ¾ patients (76%) patients were females as is seen in most cases of subacute thyroiditis. The female preponderance also highlights the autoimmune etiology of SAT that is well documented in the literature [2, 44, 45]. It is important to realize that patients can either present with pre-dominant COVID-19 features (headache, anosmia, upper respiratory symptoms) or pre-dominant SAT features (given above). After a careful review of the literature, the authors reiterate that anterior neck pain must carefully be assessed through a good history and examination so that it is not conflated with upper respiratory symptoms.

Keeping in view the above discussion, we believe it is important for clinicians to assess for SAT when encountering patients with ongoing or previous COVID-19. It is also imperative to assess for an underlying asymptomatic infection via RT-PCR if a patient presents with features suggestive of SAT. A proper follow-up of COVID-19 might also be needed because most cases have been reported in those with a recent or previous infection. It must also be noted that treatment outcomes in all the 21 cases were excellent with steroids and anti-inflammatory drugs, reiterating the need for timely diagnosis of this clinical entity.

The authors would like to acknowledge some limitations while drawing inferences in this review. Firstly, the sample size is small because of lack of published literature on the topic. Secondly, the lack of control group and individual-centered data limits the generalizability of results. Lastly, there is a tendency towards publication bias as clinically challenging cases are more likely to be reported and published.

Conclusion

Direct viral injury and post-viral inflammatory reaction may contribute to subacute thyroiditis seen during or after COVID-19 infection. The mechanism of direct viral injury is well supported by the presence of ACE-2 and TMPRSS2 mRNA in thyroid cells, while post-viral inflammatory reaction has been documented previously as the cause in many other viral infections associated with subacute thyroiditis. COVID-19-associated SAT is likely to present with the classic clinical features of fever and neck pain, hyperthyroid TFTs (low TSH, high free T4), and suggestive ultrasound findings. The recognition of this clinical entity is important for physicians to consider because prompt treatment is likely to lead to complete resolution; however, the possibility of a hypothyroid phase after SAT treatment should not be ignored. A proper follow-up after COVID-19 resolution is necessary because cases of SAT have been reported months after the infection.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ Contributions

Muhammad Aemaz Ur Rehman: Conceptualization, literature search, critical appraisal, drafting the manuscript, proofreading, and revising the final version.

Hareem Farooq: Generating and filling tables in Microsoft Excel, analyzing results using Excel, drafting the manuscript, proofreading, and revising the final version.

Muhammad Mohsin Ali: Refining the article design, critical revision and supervision of the work, critical appraisal, proofreading, and revising the final version.

Muhammad Ebaad Ur Rehman: Collecting data according to PRISMA and designing PRISMA flowchart, revising the work critically, proofreading, and revising the final version.

Qudsia Anwar Dar: Refining the article design, critical revision of the work, and proofreading the final manuscript.

Awab Hussain: Refining article design, critical revision of the work, final approval of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Covid-19

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Muhammad Aemaz Ur Rehman, Email: aemaz100@gmail.com.

Hareem Farooq, Email: hareemfarooq29@gmail.com.

Muhammad Mohsin Ali, Email: mohsinali@kemu.edu.pk.

Muhammad Ebaad Ur Rehman, Email: ebaadcr7@outlook.com.

Qudsia Anwar Dar, Email: qudsiaabbas@gmail.com.

Awab Hussain, Email: awabhussain12@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Hennessey Jv. Subacute thyroiditis. Endotext [Internet]. 2018.

- 2.Shrestha RT, Hennessey J. Acute and Subacute, and Riedel’s Thyroiditis. 2015 Dec 8. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Grossman A, Hershman JM, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, McGee EA, McLachlan R, Morley JE, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Singer F, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000–. PMID: 25905408.

- 3.Desailloud R, Hober D. Viruses and thyroiditis: an update. Virol J. 2009;6(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scappaticcio L, Pitoia F, Esposito K, Piccardo A, Trimboli P. Impact of COVID-19 on the thyroid gland: an update. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 2020 Nov 25:1-3.10.1007/s11154-020-09615-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Asfuroglu Kalkan E, Ates I. A case of subacute thyroiditis associated with Covid-19 infection. J Endocrinol Investig. 2020;43:1173–1174. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01316-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brancatella A, Ricci D, Cappellani D, Viola N, Sgrò D, Santini F, Latrofa F. Is subacute thyroiditis an underestimated manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection? Insights from a case series. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2020;105(10):e3742–e37e6. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campos-Barrera E, Alvarez-Cisneros T, Davalos-Fuentes M. Subacute thyroiditis associated with COVID-19. Case reports in endocrinology. 2020;2020:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2020/8891539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakraborty U, Ghosh S, Chandra A, Ray AK. Subacute thyroiditis as a presenting manifestation of COVID-19: a report of an exceedingly rare clinical entity. BMJ Case Reports CP. 2020;13(12):e239953. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-239953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guven M. Subacute thyroiditis in the course of coronavirus disease 2019: A Case Report. Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2020;10(3-4):110–112. doi: 10.14740/jem678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ippolito S, Dentali F, Tanda M. SARS-CoV-2: a potential trigger for subacute thyroiditis? Insights from a case report. J Endocrinol Investig. 2020;43:1171–1172. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01312-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khatri A, Charlap E, Kim A. Subacute thyroiditis from COVID-19 infection: a case report and review of literature. European Thyroid Journal. 2020;9(6):309–13.10.1159/000511872. doi: 10.1159/000511872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maris J, Florencio MQV, Joven MH. Subacute thyroiditis in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019. AACE clinical case reports. 2020;6(6):e361–e3e4. doi: 10.4158/ACCR-2020-0524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattar SAM, Koh SJQ, Chandran SR, Cherng BPZ. Subacute thyroiditis associated with COVID-19. BMJ Case Reports CP. 2020;13(8):e237336. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-237336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruggeri RM, Campennì A, Siracusa M, Frazzetto G, Gullo D. Subacute thyroiditis in a patient infected with SARS-COV-2: an endocrine complication linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hormones. 2020;20:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s42000-020-00230-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chong WH, Shkolnik B, Saha B, Beegle S. Subacute thyroiditis in the setting of coronavirus disease 2019. Am J Med Sci. 2020;361:400–402. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2020.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brancatella A, Ricci D, Viola N, Sgrò D, Santini F, Latrofa F. Subacute thyroiditis after SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(7):2367–2370. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sohrabpour S, Heidari F, Karimi E, Ansari R, Tajdini A, Heidari F. Subacute thyroiditis in COVID-19 patients. Eur Thyroid J. 2020;9(6):322–4.10.1159/000511707. doi: 10.1159/000511707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Lisy K, Qureshi R, Mattis P, Mu P. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. 10.46658/JBIMES-20-08

- 19.Satoh M. Virus-like particles in the follicular epithelium of the thyroid from a patient with subacute thyroiditis (DE QUERVAIN) Pathol Int. 1975;25(4):499–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1975.tb00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prummel MF, Strieder T, Wiersinga WM. The environment and autoimmune thyroid diseases. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150(5):605–618. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1500605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishihara E, Ohye H, Amino N, Takata K, Arishima T, Kudo T, Ito M, Kubota S, Fukata S, Miyauchi A. Clinical characteristics of 852 patients with subacute thyroiditis before treatment. Intern Med. 2008;47(8):725–729. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volpé R. 7 Subacute (de Quervain’s) thyroiditis. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;8(1):81–95. doi: 10.1016/S0300-595X(79)80011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walfish PG. Thyroiditis. Curr Ther Endocrinol Metab. 1997;6:117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Intenzo CM, Park CH, Kim SM, Capuzzi DM, Cohen SN, Green PA. Clinical, laboratory, and scintigraphic manifestations of subacute and chronic thyroiditis. Clin Nucl Med. 1993;18(4):302–306. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singer PA. Thyroiditis: acute, subacute, and chronic. Med Clin N Am. 1991;75(1):61–77. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alfadda AA, Sallam RM, Elawad GE, AlDhukair H, Alyahya MM. Subacute thyroiditis: clinical presentation and long term outcome. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014. 10.1155/2014/794943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Ruchala M, Szczepanek-Parulska E, Zybek A, Moczko J, Czarnywojtek A, Kaminski G, Sowinski J. The role of sonoelastography in acute, subacute and chronic thyroiditis: a novel application of the method. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166(3):425–432. doi: 10.1530/eje-11-0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frates MC, Marqusee E, Benson CB, Alexander EK. Subacute granulomatous (de Quervain) thyroiditis: grayscale and color Doppler sonographic characteristics. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32(3):505–511. doi: 10.7863/jum.2013.32.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park SY, Kim EK, Kim MJ, Kim BM, Oh KK, Hong SW, Park CS. Ultrasonographic characteristics of subacute granulomatous thyroiditis. Korean J Radiol. 2006;7(4):229. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2006.7.4.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Croce L, Gangemi D, Ancona G, Liboà F, Bendotti G, Minelli L, Chiovato L. The cytokine storm and thyroid hormone changes in COVID-19. J Endocrinol Investig. 2021;9:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01506-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang W, Su X, Ding Y, Fan W, Zhou W, Su J, et al. Thyroid function abnormalities in COVID-19 patients. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11. 10.3389/fendo.2020.623792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Wei L, Sun S, Xu C-h, Zhang J, Xu Y, Zhu H, et al. Pathology of the thyroid in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Hum Pathol. 2007;38(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang Y, Liu J, Zhang D, Xu Z, Ji J, Wen C. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: the current evidence and treatment strategies. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1708. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Q, Zhang Y, Wu L, Niu S, Song C, Zhang Z, et al. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181(4):894–904. e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–80. e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, Gao H, Guo F, Guan B, Huan Y, Yang P, Zhang Y, Deng W, Bao L. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus–induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005;11(8):875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rotondi M, Coperchini F, Ricci G, Denegri M, Croce L, Ngnitejeu S, et al. Detection of SARS-COV-2 receptor ACE-2 mRNA in thyroid cells: a clue for COVID-19-related subacute thyroiditis. Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2020:1-6.10.1007/s40618-020-01436-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Lazartigues E, Qadir MMF, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Endocrine significance of SARS-CoV-2’s reliance on ACE2. Endocrinology. 2020;161(9):bqaa108. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqaa108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, Sui J, Wong SK, Berne MA, Somasundaran M, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Greenough TC, Choe H. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426(6965):450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner AJ, Tipnis SR, Guy JL, Rice GI, Hooper NM. ACEH/ACE2 is a novel mammalian metallocarboxypeptidase and a homologue of angiotensin-converting enzyme insensitive to ACE inhibitors. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80(4):346–353. doi: 10.1139/y02-021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li M-Y, Li L, Zhang Y, Wang X-S. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infectious diseases of poverty. 2020;9:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00662-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bellastella G, Maiorino MI, Esposito K. Endocrine complications of COVID-19: what happens to the thyroid and adrenal glands? J Endocrinol Investig. 2020;43:1169–1170. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen W, Tian Y, Li Z, Zhu J, Wei T, Lei J. Potential interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and thyroid: a review. Endocrinology. 2021. 10.1210/endocr/bqab004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Lazarus JH. Silent thyroiditis and subacute thyroiditis. Werner and Ingbar's The Thyroid-A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 1996:577-91.

- 45.Bindra A, Braunstein GD. Thyroiditis. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(10):1769–1776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.