Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive decline, robust microgliosis, neuroinflammation, and neuronal loss. Genome-wide association studies recently highlighted a prominent role for microglia in late-onset AD (LOAD). Specifically, inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase (INPP5D), also known as SHIP1, is selectively expressed in brain microglia and has been reported to be associated with LOAD. Although INPP5D is likely a crucial player in AD pathophysiology, its role in disease onset and progression remains unclear.

We performed differential gene expression analysis to investigate INPP5D expression in AD and its association with plaque density and microglial markers using transcriptomic (RNA-Seq) data from the Accelerating Medicines Partnership for Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) cohort. We also performed quantitative real-time PCR, immunoblotting, and immunofluorescence assays to assess INPP5D expression in the 5xFAD amyloid mouse model.

Differential gene expression analysis found that INPP5D expression was upregulated in LOAD and positively correlated with amyloid plaque density. In addition, in 5xFAD mice, Inpp5d expression increased as the disease progressed, and selectively in plaque-associated microglia. Increased Inpp5d expression levels in 5xFAD mice were abolished entirely by depleting microglia with the colony-stimulating factor receptor-1 antagonist PLX5622.

Our findings show that INPP5D expression increases as AD progresses, predominantly in plaque-associated microglia. Importantly, we provide the first evidence that increased INPP5D expression might be a risk factor in AD, highlighting INPP5D as a potential therapeutic target. Moreover, we have shown that the 5xFAD mouse model is appropriate for studying INPP5D in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Microglia, INPP5D, AD risk, Plaque

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, with pathogenesis arising from perturbed β-amyloid (Aβ) homeostasis in the brain (Lee & Landreth, 2010). The mechanisms underlying the development of the most common form of AD, late-onset AD (LOAD), are still unknown. Microglia, the primary immune cells in the brain play a crucial role in AD pathogenesis (Mandrekar-Colucci & Landreth, 2010). Recent large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) reported that many genetic loci associated with LOAD risk are related to inflammatory pathways, suggesting that microglia are involved in modulating AD pathogenesis (Karch & Goate, 2015; Lambert et al., 2013). Among the microglia-related genetic factors in LOAD, INPP5D (phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate 5-phosphatase 1) was associated with LOAD (Jing et al., 2016; Lambert et al., 2013) and CSF t-tau/Aβ1–42 ratio (Yao et al., 2019). INPP5D encodes inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase which participates in regulation of microglial gene expression (Viernes, Choi, Kerr & Chisholm, 2014). Specifically, INPP5D inhibits signal transduction initiated by activation of immune cell surface receptors, including Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), Fc gamma receptor (FcγR) and Dectin-1 (Peng, Malhotra, Torchia, Kerr, Coggeshall & Humphrey, 2010). The conversion of PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(3,4)P2 is catalyzed by INPP5D following its translocation from the cytosol to the cytoplasmic membrane. The loss of PI(3,4,5)P3 prevents the activation of the immune cell surface receptors (Rohrschneider, Fuller, Wolf, Liu & Lucas, 2000). Interestingly, genetic variants of TREM2, FcγR, and Dectin-1 are also associated with increased AD risk (Krasemann et al., 2017; Sims et al., 2017; Tsai et al., 2020) and are potentially involved in regulating INPP5D activity. Inhibiting INPP5D promotes microglial proliferation, phagocytosis, and increases lysosomal compartment size (Pedicone et al., 2020). Although INPP5D has been shown to play an important role in microglial function, its role in AD remains unclear.

Here, we report that INPP5D is upregulated in AD, and elevated INPP5D expression levels are associated with microglial markers and amyloid plaque density. Furthermore, in the 5xFAD mouse model, we found a disease-progression-dependent increase in INPP5D expression in plaque-associated microglia. Our results suggest that INPP5D plays a role in microglia phenotypes in AD and is a potential target for microglia-focused AD therapies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Human data sets

RNA-Seq data were obtained from the AMP-AD Consortium, including participants of the Mayo Clinic Brain Bank cohort, the Mount Sinai Medical Center Brain Bank (MSBB) cohort, and the Religious Orders Study and Memory and Aging Project (ROSMAP) cohort (Table 1). Sample collection, postmortem sample descriptions, tissue and RNA preparation, library preparation and sequencing, and sample quality controls were described in detail in previous papers (Allen et al., 2016; De Jager et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018)

Table 1.

Demographic information of the participants included in this human dataset

| Brain region |

Temporal Cortex |

Parahippocampal Gyrus |

Superior Temporal Gyrus |

Inferior Frontal Gyrus |

Frontal Pole |

Cerebellum |

Dosolateral Prefrontal Cortex |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue cohort | (Mayo) | (MSBB) | (MSBB) | (MSBB) | (MSBB) | (Mayo) | (ROSMAP) | |||||||||||

| Diagnosis | CN | LOAD | CN | MCI | LOAD | CN | MCI | LOAD | CN | MCI | LOAD | CN | MCI | LOAD | CN | AD | CN | Probable AD |

| No. of participants | 71 | 80 | 16 | 14 | 78 | 21 | 18 | 98 | 18 | 16 | 102 | 22 | 20 | 111 | 72 | 79 | 86 | 155 |

| Sex (Female/Male) | 35/36 | 49/31 | 11/5 | 7/7 | 53/25 | 16/5 | 11/7 | 65/33 | 12/6 | 7/9 | 69/33 | 16/6 | 11/9 | 75/36 | 35/37 | 47/32 | 47/39 | 109/46 |

| Mean age at death (SD), years | 82.7 (8.5) | 82.6 (7.7) | 83.5 (8.9) | 80.6 (10.8) | 85.5 (6.1) | 83.8 (8.1) | 82.1 (10.4) | 84.5 (6.7) | 83.2 (8.6) | 80.8 (10.5) | 85.4 (6.0) | 83.1 (7.7) | 83.2 (9.8) | 85.4 (5.9) | 82.3 (8.3) | 82.5 (7.7) | 83.4 (5.9) | 88.2 (3.1) |

| APOE genotype (e4+/c4−) | 62/9 | 38/42 | 14/2 | 9/5 | 57/21 | 17/4 | 12/6 | 65/33 | 16/2 | 8/8 | 72/30 | 19/3 | 13/7 | 70/41 | 62/10 | 38/41 | 77/9 | 91/64 |

CN cognitively normal, AD Alzheimer’s disease, MCI mild cognitive impairment, APOE ε4+/− carriers and non-carriers of the APOE ε4 allele, SD standard deviation

In the Mayo Clinic RNA-Seq dataset (Allen et al., 2016), the RNA-Seq-based whole transcriptome data were generated from human samples of 151 temporal cortex (TCX) (71 cognitively normal older adult controls (CN) and 80 LOAD) and 151 cerebella (CER) (72 CN and 79 LOAD). LOAD participants met the neuropathological criteria for AD (Braak score ≥4.0), and cognitively normal participants had no neurodegenerative diagnosis (Braak score ≤ 3.0).

In the MSBB dataset (Wang et al., 2018), data were generated from human samples from CN, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and LOAD participants’ parahippocampal gyrus (PHG) and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), superior temporal gyrus (STG) and frontal pole (FP). The clinical dementia rating scale (CDR) was used to assess dementia and cognitive status (Morris, 1993). LOAD was defined as those with CDR scores ≥ 1 and Braak scores ≥4.0, CN was defined as those with CDR scores =0 and Braak scores <3.0, MCI as those with CDR scores=0.5 and Braak scores <3.0, and LOAD as those with CDR scores ≥ 1 and Braak scores ≥4.0. CN participants had no significant memory concerns. This study included 108 participants (16 CN, 14 MCI, and 78 LOAD) for PHG, 137 participants (21 CN, 18 MCI, and 98 LOAD) for STG, 136 participants (18 CN, 16 MCI, and 102 LOAD) for IFG, and 153 participants (22 CN, 20 MCI, and 111 LOAD) for FP.

In the ROSMAP dataset (Bennett, Buchman, Boyle, Barnes, Wilson & Schneider, 2018), we used the clinical consensus diagnosis of cognitive status at the time of death (cogdx) from all available clinical data to define diagnosis groups (CN: cogdx=1; probable AD: cogdx=4), and the RNA-Seq data were generated from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortices of 241 participants (86 CN and 155 probable AD).

2.2. Animal models

Wild-type (WT) and 5xFAD mice were maintained on the C57BL/6J background (JAX MMRRC Stock# 034848) for IHC and qPCR studies. Two-, four-, six-, eight-, and twelve-month-old mice were used. In the PLX5622 study, we used WT and 5xFAD mice maintained on the mixed C57BL/6J and SJL background [B6SJL-Tg (APPSwFlLon, PSEN1*M146L*L286V) 6799Vas, Stock #34840-JAX]) (Fig. 3e and 3f). The 5XFAD transgenic mice overexpress five FAD mutations: the APP (695) transgene contains the Swedish (K670N, M671L), Florida (I716V), and London (V717I) mutations and the PSEN1 transgene contains the M146L and L286V FAD mutations. Up to five mice were housed per cage with SaniChip bedding and LabDiet® 5K52/5K67 (6% fat) feed. The colony room was kept on a 12:12 hr. light/dark schedule with the lights on from 7:00 am to 7:00 pm daily. They were bred and housed in specific-pathogen-free conditions. Both male and female mice were used. The numbers of male and female mice were equally distributed, and the results of individual values were shown in the scatter plot.

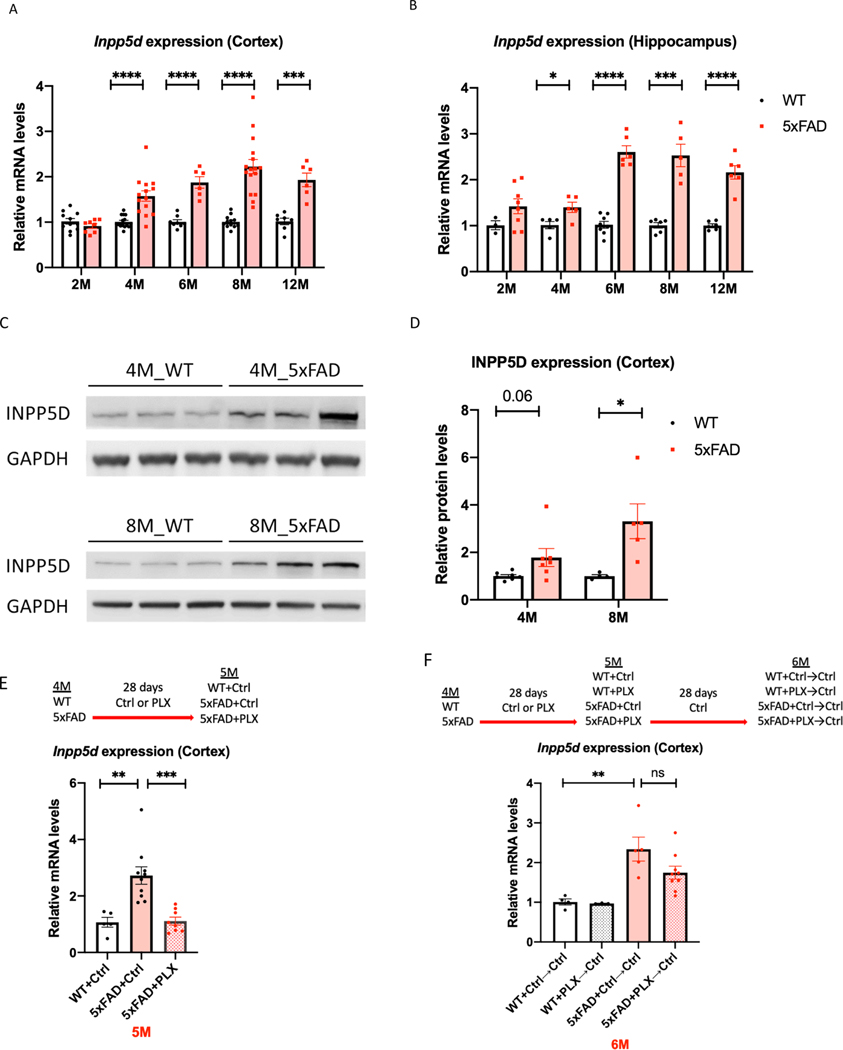

Figure 3. Inpp5d levels are increased in 5xFAD mice.

Gene and protein levels of Inpp5d were assessed in cortical and hippocampal lysates from 5xFAD mice. Gene expression levels of Inpp5d were significantly increased in both cortex (A) and hippocampus (B) at 4, 6, 8, and 12 months of age (n=6–15 mice). There were significant changes in Inpp5d protein levels in the cortex at 8 months of age and an increased trend in the cortex at 4 months of age (n=4–7; C and D). Increased Inpp5d levels were abolished with PLX5622 treatment (E), and restored after switching PLX diet to normal diet (F) (n=3–10). *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001, ns not significant.

2.3. PLX5622 animal treatment

At four months of age, either normal rodent diet or PLX5622-containing chow was administered to 5XFAD mice for 28 days. An additional cohort of four-month-old mice was treated with PLX5622 or control diet for 28 days, then discontinued from PLX5622 feed and fed a normal rodent diet for an additional 28 days. At six months of age, this cohort of mice was euthanized. Plexxikon Inc. provided PLX5622 formulated in AIN-7 diet at 1200 mg/kg (Casali, MacPherson, Reed-Geaghan & Landreth, 2020).

2.4. Statistical analysis

In the human study, differential expression analysis was performed using limma software (Ritchie et al., 2015) to investigate the diagnosis group difference of INPP5D between CN, MCI, and AD. Age, sex, and APOE ε4 carrier status were used as covariates. To investigate the association between INPP5D expression levels and amyloid plaque density (number of plaques/mm2) (Beckmann et al., 2020; Haroutunian et al., 1998; Readhead et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018) or expression levels of microglia-specific markers (AIF1 and TMEM119), we used a generalized linear regression model with INPP5D expression levels as a dependent variable and plaque density or microglia-specific markers along with age, sex, and APOE ε4 carrier status as explanatory variables. The regression was performed with the “glm” function from the stats package in R (version 3.6.1).

In the mouse study, GraphPad Prism (Version 8.4.3) was used to perform the statistical analyses. Differential expression analysis of both gene and protein levels between WT and 5xFAD mice was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test. The statistical comparisons between mice with and without PLX5622 treatments were performed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s posthoc test. Graphs represent the mean and standard error of the mean.

2.5. RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Mice were anesthetized with Avertin and perfused with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cortical and hippocampal regions from the hemisphere were micro-dissected and stored at −80°C. Frozen brain tissue was homogenized in buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH=7.4), 250 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM EDTA, RNase-free water, and stored in an equal volume of RNA-Bee (Amsbio, CS-104B) at −80°C until RNA extraction. RNA was isolated by chloroform extraction and purified with the Purelink RNA Mini Kit (Life Technologies #12183020) with an on-column DNAse Purelink Lit (Life Technologies #12183025). 500 ng RNA was converted to cDNA with the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems #4388950), and qPCR was performed on a StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies). Relative gene expression was determined with the 2-ΔΔCTmethod and assessed relative to Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1). Inpp5d primer: Taqman Gene Expression Assay (Inpp5d: Mm00494987_m1 from the Life Technologies). Student’s t-test was performed for qPCR assays, comparing WT with 5xFAD animals.

2.6. Immunofluorescence

Brains were fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C. Following overnight fixation, brains were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose at 4°C and embedded. Brains were processed on a microtome as 30 μm free-floating sections. For immunostaining, at least three matched brain sections were used. Free-floating sections were washed and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton in PBS (PBST), followed by antigen retrieval using 1x Reveal Decloaker (Biocare Medical) at 85°C for 10 mins. Sections were blocked in 5% normal donkey serum in PBST for 1 hr. at room temperature (RT). The following primary antibodies were incubated in 5% normal donkey serum in PBST overnight at 4°C: IBA1 (Novus Biologicals #NB100–1028 in goat, 1:1000); 6E10 (BioLegend #803001 in mouse, 1:1000; AB_2564653); and SHIP1/INPP5D (Cell Signaling Technology (CST) #4C8, 1:500, Rabbit mAb provided by CST in collaboration with Dr. Richard W. Cho). Sections were washed and visualized using respective species-specific AlexaFluor fluorescent antibodies (diluted 1:1000 in 5% normal donkey serum in PBST for 1 hr. at RT). Sections were counterstained and mounted onto slides. For X-34 staining (Sigma, #SML1954), sections were dried at RT, rehydrated in PBST, and stained for ten mins at RT. Sections were then washed five times in double-distilled water and washed again in PBST for five mins. Images were acquired on a fluorescent microscope with similar exposure and gains across stains and animals. Images were merged using ImageJ (NIH).

2.7. Immunoblotting

Tissue was extracted and processed as described above, then centrifuged. Protein concentration was measured with a BCA kit (Thermo Scientific). 50 μg of protein per sample was denatured by heating samples for 10 mins at 95°C, loaded into 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies) and run at 100 V for 90 mins. The following primer antibodies were used: SHIP1/INPP5D (CST #4C8 1:500, Rabbit mAb) and GAPDH (Santa Cruz #sc-32233). Each sample was normalized to GAPDH, and the graphs represent the values normalized to the mean of the WT mice group at each time point.

3. Results

3.1. INPP5D expression levels are increased in AD.

INPP5D is a member of the inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase (INPP5) family and possesses a set of core domains, including an N-terminal SH2 domain (amino acids 5–101), Pleckstrin homology-related (PH-R) domain (amino acids 292–401), lipid phosphatase region (amino acids 401–866) with C2 domain (amino acids 725–863), and C-terminal proline-rich region (amino acids 920–1148) with two SH3 domains (amino acids 969–974 and 1040–1051) (Fig. 1A). Differential expression analysis was performed using RNA-Seq data from seven brain regions from the AMP-AD cohort. Expression levels of INPP5D were increased in the temporal cortex (logFC=0.35, p=1.12E-02; Fig. 1B), parahippocampal gyrus (logFC=0.54, p=7.17E-03; Fig. 1C), and inferior frontal gyrus (logFC=0.44, p=2.33E-03; Fig. 1D) of LOAD patients with age and sex as covariates (Table 2). Interestingly, INPP5D expression was also found to be increased in the inferior frontal gyrus of LOAD patients compared with MCI subjects (logFC=0.45, p=6.76E-03; Fig. 1D). Results were similar when APOE ε4 carrier status was used as an additional covariate. INPP5D remained overexpressed in the temporal cortex (logFC=0.34, p=2.75E-02), parahippocampal gyrus (logFC=0.53, p=1.08E-02), and inferior frontal gyrus (logFC=0.42, p=4.35E-03) of LOAD patients. However, we did not find any differences between the diagnosis groups in the cerebellum, frontal pole, superior temporal gyrus, or dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Table 2). To examine whether INPP5D was associated with microglia, we analyzed the association between INPP5D and microglia-specific marker genes (AIF1 and TMEM119). AIF1 and TMEM119 were significantly associated with INPP5D expression levels in the parahippocampal gyrus (AIF1: β=0.4386, p=4.10E-07; TMEM119: β=0.7647, p=<2E-16), inferior frontal gyrus (AIF1: β=0.2862, p=6.36E-08; TMEM119: β=0.6109, p=<2E-16), frontal pole (AIF1: β=0.2179, p=4.53E-04; TMEM119 β=0.5062, p=4.00E-15), and superior temporal gyrus (AIF1: β=0.3013, p=5.36E-07; TMEM119: β=0.6914, p=<2E-16) (Table 3).

Figure 1. Relative quantification of INPP5D expression in the studied participants.

(A) Domain architecture of INPP5D drawn to scale. Gene expression of INPP5D is showed as logCPM values in (B) Temporal cortex (TCX)-Mayo, (C) Parahippocampal gyrus (PHG)-MSBB, (D) Inferior frontal gyrus (IFG)-MSBB, (E) Cerebellum (CER)-Mayo, (F) Frontal pole (FP)-MSBB, (G) Superior temporal gyrus (STG)-MSBB, (H) Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)-ROSMAP. SH2 Src Homology 2 domain, SH3 SRC Homology 3 domain, C2 C2 domain.

Table 2.

INPP5D expression levels were increased in LOAD

| Brain Regions | Tempora l Cortex | Parahippocampal Gyrus | Inferior Frontal Gyrus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate: Age and Sex | |||||||

| Contrast | CN vs. LOAD | CN vs. MCI | MCI vs. LOAD | CN vs. LOAD | CN vs. MCI | MCI vs. LOAD | CN vs. LOAD |

| logFC (FC) | 0.349 (1.274) | 0.012 (1.008) | 0.565 (1.479) | 0.536 (1.449) | −0.01 (0.993) | 0.445 (1.361) | 0.437 (1.353) |

| p-value | 1.12E−02 | 9.99E−01 | 7.56E−02 | 7.17E−03 | 1.00E+00 | 6.76E−03 | 2.33E−03 |

| Covariate: Age, Sex, and APOE ε4 status | |||||||

| Contrast | CN vs. LOAD | CN vs. MCI | MCI vs. LOAD | CN vs. LOAD | CN vs. MCI | MCI vs. LOAD | CN vs. LOAD |

| logFC (FC) | 0.341 (1.266) | −0.034 (0.976) | 0.572 (1.486) | 0.528 (1.441) | −0.055 (0.962) | 0.465 (1.380) | 0.422 (1.339) |

| p-value | 2.75E−02 | 1.00E+00 | 1.00E−01 | 1.08E−02 | 1.00E+00 | 8.00E−03 | 4.35E−03 |

| Brain Regio ns | Cerebellum | Frontal Pole | Superior Temporal Gyrus | Dosolateral Prefrontal Cortex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate: Age and Sex | ||||||||

| Contrast | CN vs. LOAD | CN vs. MCI | MCI vs. LOAD | CN vs. LOAD | CN vs. MCI | MCI vs. LOAD | CN vs. LOAD | CN vs.Probable AD |

| logFC (FC) | 0.153 (1.111) | −0.149 (0.901) | 0.200 (1.148) | 0.093 (1.066) | −0.012 (0.991) | 0.319 (1.247) | 0.289 (1.221) | 0.176 (1.129) |

| p-value | 2.15E−01 | 9.85E−01 | 4.80E−01 | 8.65E−01 | 1.00E+00 | 2.09E−01 | 1.78E−01 | 5.76E−02 |

| Covariate: Age, Sex, and APOE ε4 status | ||||||||

| Contrast | CN vs. LOAD | CN vs. MCI | MCI vs. LOAD | CN vs. LOAD | CN vs. MCI | MCI vs. LOAD | CN vs. LOAD | CN vs.Probable AD |

| logFC (FC) | 0.208 (1.155) | −0.180 (0.882) | 0.200 (1.148) | 0.068 (1.048) | −0.020 (0.986) | 0 0.282 (1.215) | 0.221 (1.165) | 0.170 (1.125) |

| p-value | 1.23E−01 | 9.53E−01 | 5.13E−01 | 9.25E−01 | 1.00E+00 | 2.89E−01 | 3.26E−01 | 9.46E−02 |

Table 2 shows the p-values for the gene expression analyses performed with limma using RNA-Seq data from the AMP-AD Consortium.

CN cognitively normal, AD Alzheimer’s disease, MCI mild cognitive impairment, logFC log fold-change, FC fold-change. The logFC values denoted as log2FC in limma.

Table 3.

INPP5D expression levels are associated with amyloid plaque density and microglia-specific markers

| Brain Regions (MSBB) | Parahippocamp al Gyrus | Inferior Frontal Gyrus | Frontal Pole | Superior Temporal Gyrus | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p value | β | SE | p value | β | SE | p value | β | SE | p value | |

| Plaque | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.02 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.95 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.22 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.06 |

| Mean Density | 212 | 070 | E-03 | 163 | 052 | E-03 | 151 | 059 | E-02 | 220 | 062 | E-04 |

| AIF1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 4.10 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 6.36 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 4.53 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 5.36 |

| 386 | 811 | E-07 | 862 | 499 | E-08 | 179 | 607 | E-04 | 013 | 572 | E-07 | |

| TMEM119 | 0.7 | 0.0 | <2E-16 | 0.6 | 0.0 | <2E-16 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | <2E-16 |

| 647 | 527 | 109 | 446 | 062 | 578 | E-15 | 914 | 496 | ||||

Table 3 shows the β coefficient (β), standard error (SE), and p-value for the association analysis between INPP5D expression levels and amyloid plaque density or expression levels of microglia-specific markers AIF1 and TMEM119 by general linear models.

3.2. INPP5D expression levels are associated with amyloid plaque density in the human brain.

We investigated the association between INPP5D expression levels and mean amyloid plaque densities in four brain regions (Table 3). Expression levels of INPP5D were associated with amyloid plaques in the parahippocampal gyrus (β=0.0212, p=3.02E-03; Fig. 2A), inferior frontal gyrus (β=0.0163, p=1.95E-03; Fig. 2B), frontal pole (β=0.0151, p=1.22E-02; Fig. 2C), and superior temporal gyrus (β=0.0220, p=5.05E-04; Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Association of INPP5D expression with amyloid plaque mean density.

The scatter plots show the positive association between INPP5D expression and plaque mean density in (A) parahippocampal gyrus, (B) inferior frontal gyrus, (C) frontal pole, and (D) superior temporal gyrus from the MSBB cohort.

3.3. INPP5D expression levels are increased in an amyloid pathology mouse model

We recapitulated our findings from the human data in the amyloidogenic mouse model, 5xFAD. We observed increased Inpp5d mRNA levels in 5xFAD mice throughout disease progression compared with WT controls in the brain cortex (Fig. 3A) and hippocampus (Fig. 3B) of four-, six-, eight-, and twelve-month-old mice (4-months: 1.57-fold in the cortex, 1.40-fold in the hippocampus; 6-months: 1.86-fold in the cortex, 2.61-fold in the hippocampus; 8-months: 2.23-fold in the cortex and 2.53-fold in the hippocampus; and 12-months: 1.93-fold in the cortex and 2.16-fold in the hippocampus). Similarly, INPP5D protein levels were increased in the cortex of 5xFAD mice at four and eight months of age (1.79 and 3.31-fold, respectively; p=0.06) (Fig. 3C and 3D). To assess Inpp5d induction was dependent on microglia, we depleted microglia in four-month-old 5xFAD mice by treating the animals with the colony-stimulating factor receptor-1 antagonist PLX5622 (PLX) for 28 days (Casali, MacPherson, Reed-Geaghan & Landreth, 2020). PLX treatment completely abolished the increase of Inpp5d in 5xFAD mice (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, expression levels of Inpp5d were restored after switching from the PLX diet to a normal diet for 28 further days (Fig. 3F).

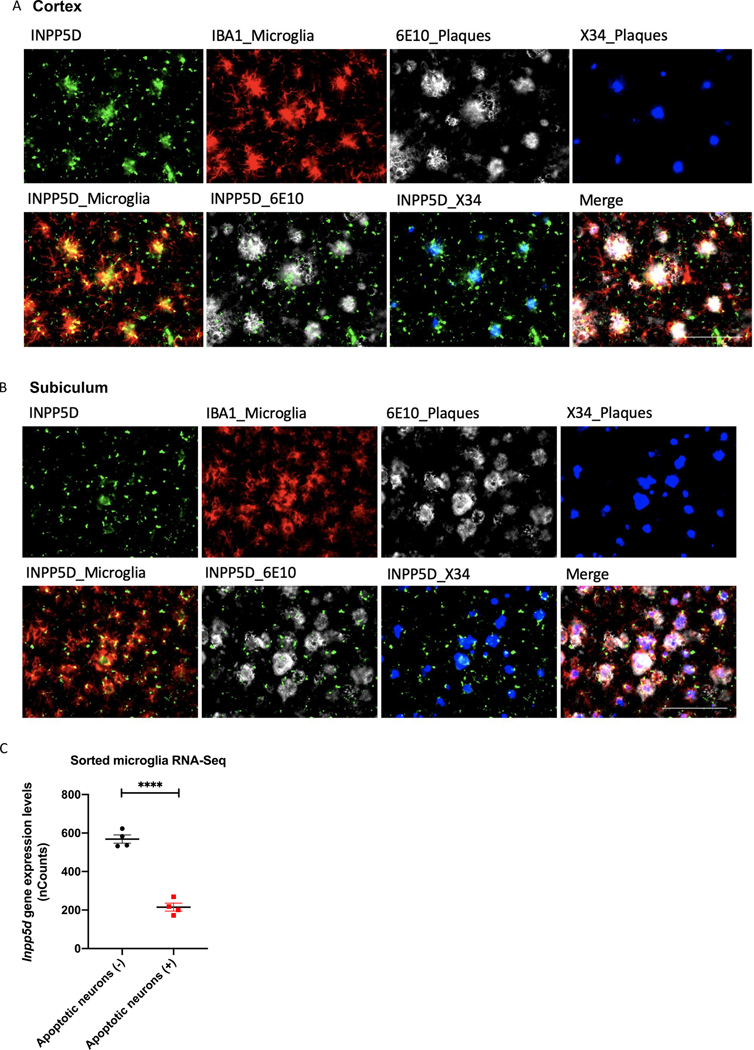

3.4. INPP5D expression levels are increased in plaque-associated microglia

Immunohistochemistry of 5xFAD mice brain slices at eight months old revealed that Inpp5d was mainly expressed in plaque-associated microglia (Fig. 4). INPP5D- and IBA1 (AIF1)-positive microglia cluster around 6E10-positive or X-34-positive plaques in the cortex (Fig. 4A) and subiculum (Fig. 4B). We did not detect any INPP5D expression in WT control mice (data not shown). Furthermore, analysis of transcriptomic data of sorted microglia from WT mouse cortices injected with labeled apoptotic neurons (Krasemann et al., 2017) has shown a reduction of Inpp5d expression levels in phagocytic microglia compared with non-phagocytic microglia (Fig. 4C). The result is in agreement with the previous report that INPP5D inhibition promotes microglial phagocytosis (Pedicone et al., 2020).

Figure 4. INPP5D expression levels were increased in plaque-associated microglia.

INPP5D was mainly expressed in plaque-associated microglia. INPP5D- and IBA1 (AIF1)-positive microglia cluster around 6E10-positive or X-34-positive plaques in both cortex (A) and subiculum (B) of 8-month-old mice. Analysis of transcriptomic data of sorted microglia from murine brains injected with apoptotic neurons (Krasemann et al) revealed a decreased Inpp5d expression in phagocytic microglia compared to non-phagocytic microglia (C). Scale bar, 100 μm. ****p<0.0001

4. Discussion

Although genetic variants in INPP5D have been associated with LOAD risk (Farfel, Yu, Buchman, Schneider, De Jager & Bennett, 2016; Jing et al., 2016; Lambert et al., 2009; Yao et al., 2019), the role of INPP5D in AD remains unclear. We identified that INPP5D expression levels are increased in the brain of LOAD patients. Furthermore, expression levels of INPP5D positively correlate with brain amyloid plaque density and AIF1 and TMEM119 (microglial marker gene) expression (Hopperton, Mohammad, Trepanier, Giuliano & Bazinet, 2018; Kaiser & Feng, 2019; Satoh et al., 2016). We performed experiments with mice at different ages relevant to the different microglial states and disease progression. We observed similar findings in the 5xFAD amyloidogenic model, which exhibited an increase in gene and protein expression levels of Inpp5d with disease progression, predominately in plaque-associated microglia, suggesting induction of Inpp5d in plaque-proximal microglia. Similarly, a recent study reported that Inpp5d is strongly correlated with amyloid plaque deposition in the APPPS1 mouse model (Radde et al., 2006; Salih et al., 2019). These findings are consistent with the observation of microgliosis in both AD and its mouse models.

INPP5D inhibition has been associated with promoting microglial lysosome function and increased phagocytic activity (Pedicone et al., 2020). Our analysis of transcriptomic data of sorted microglia from murine brains injected with apoptotic neurons generated by Krasemann et al. showed that Inpp5d expression levels were decreased in phagocytic microglia compared to non-phagocytic (Krasemann et al., 2017). These findings support the hypothesis that an increase in INPP5D expression in AD is a part of an endogenous homeostatic microglial response to negatively control their own activity. However, this “brake” might be excessive in AD, as reflected in our findings that INPP5D expression is elevated in LOAD. INPP5D overexpression might result in microglia with deficient phagocytic capacity, resulting in increased Aβ deposition and neurodegeneration. Thus, the pharmacological targeting of INPP5D might be a novel therapeutic strategy to shift microglia towards a beneficial phenotype in AD. We believe that future studies in genetic mouse models are necessary to further clarify the role of INPP5D in microglial function and AD progression. We have now generated a mouse model in which the INPP5D gene has been inactivated and have crossed these mice with the 5xFAD amyloidogenic murine model of AD. We believe our findings from this mouse model will help determine the role of INPP5D in microglial state and disease progression.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that INPP5D plays a crucial role in AD pathophysiology and is a potential therapeutic target. INPP5D expression is upregulated in LOAD and positively correlated with amyloid plaque density. Inpp5d expression increases in the microglia of 5xFAD mice as AD progresses, predominately in plaque-associated microglia. Future studies investigating the effect of INPP5D loss-of-function on microglial phenotypes and AD progression may allow for the development of microglial-targeted AD therapies.

Highlights.

INPP5D was positively associated with amyloid plaque density in the human brain.

In the 5xFAD mouse model, Inpp5d increased in a disease-progression-dependent manner

Inpp5d was selectively expressed in plaque-associated microglia.

The increased Inpp5d expression levels were attenuated following microglia depletion.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Richard W. Cho at Cell Signaling Technology for providing SHIP1/INPP5D Rabbit mAb. We thank Louise Pay for critical comments on the manuscript. We thank Victoria von Saucken, Cynthia M. Ingraham, Deborah D. Baker, Christopher D. Lloyd, Stephanie J. Bissel, Shweta S. Puntambekar, Guixiang Xu, Roxanne Y. Williams, and Teaya N. Thomas for their help with taking care of the mice, genotyping, and helpful discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by NIA grant RF1 AG051495 (B.T.L and G.E.L), NIA grant RF1 AG050597 (G.E.L), NIA grant U54 AG054345 (B.T.L et al.), NIA grant K01 AG054753 (A.L.O), NIA grant R03 AG063250 (K.N), and NIH grant NLM R01 LM012535 (K.N)

List of abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- LOAD

late-onset AD

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- INPP5D

phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate 5-phosphatase 1

- PI(3,4,5)P3

phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate

- PI(3,4)P2

phosphatidylinositol (3,4)-bisphosphate

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- β

β coefficient

- WT

wild-type

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- APOE ε4

apolipoprotein ε4 allele

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- Seq

sequencing

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- qPCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- logFC

log fold-change

Footnotes

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animals used in the study were housed in the Stark Neurosciences Research Institute Laboratory Animal Resource Center at Indiana University School of Medicine and all experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Consent for publication

All participants were properly consented for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen M, Carrasquillo MM, Funk C, Heavner BD, Zou F, Younkin CS, et al. (2016). Human whole genome genotype and transcriptome data for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Sci Data 3: 160089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann ND, Lin WJ, Wang M, Cohain AT, Charney AW, Wang P, et al. (2020). Multiscale causal networks identify VGF as a key regulator of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun 11: 3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, & Schneider JA (2018). Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. J Alzheimers Dis 64: S161–S189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali BT, MacPherson KP, Reed-Geaghan EG, & Landreth GE (2020). Microglia depletion rapidly and reversibly alters amyloid pathology by modification of plaque compaction and morphologies. Neurobiol Dis 142: 104956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jager PL, Ma Y, McCabe C, Xu J, Vardarajan BN, Felsky D, et al. (2018). A multi-omic atlas of the human frontal cortex for aging and Alzheimer’s disease research. Sci Data 5: 180142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farfel JM, Yu L, Buchman AS, Schneider JA, De Jager PL, & Bennett DA (2016). Relation of genomic variants for Alzheimer disease dementia to common neuropathologies. Neurology 87: 489–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroutunian V, Perl DP, Purohit DP, Marin D, Khan K, Lantz M, et al. (1998). Regional distribution of neuritic plaques in the nondemented elderly and subjects with very mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 55: 1185–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopperton KE, Mohammad D, Trepanier MO, Giuliano V, & Bazinet RP (2018). Markers of microglia in post-mortem brain samples from patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Mol Psychiatry 23: 177–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing H, Zhu JX, Wang HF, Zhang W, Zheng ZJ, Kong LL, et al. (2016). INPP5D rs35349669 polymorphism with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease: A replication study and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 7: 69225–69230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser T, & Feng G (2019). Tmem119-EGFP and Tmem119-CreERT2 Transgenic Mice for Labeling and Manipulating Microglia. eNeuro 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch CM, & Goate AM (2015). Alzheimer’s disease risk genes and mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. Biol Psychiatry 77: 43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasemann S, Madore C, Cialic R, Baufeld C, Calcagno N, El Fatimy R, et al. (2017). The TREM2-APOE Pathway Drives the Transcriptional Phenotype of Dysfunctional Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Immunity 47: 566–581 e569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JC, Heath S, Even G, Campion D, Sleegers K, Hiltunen M, et al. (2009). Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 41: 1094–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, et al. (2013). Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 45: 1452–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, & Landreth GE (2010). The role of microglia in amyloid clearance from the AD brain. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 117: 949–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrekar-Colucci S, & Landreth GE (2010). Microglia and inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 9: 156–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC (1993). The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43: 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedicone C, Fernandes S, Dungan OM, Dormann SM, Viernes DR, Adhikari AA, et al. (2020). Pan-SHIP1/2 inhibitors promote microglia effector functions essential for CNS homeostasis. J Cell Sci 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q, Malhotra S, Torchia JA, Kerr WG, Coggeshall KM, & Humphrey MB (2010). TREM2- and DAP12-dependent activation of PI3K requires DAP10 and is inhibited by SHIP1. Science signaling 3: ra38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radde R, Bolmont T, Kaeser SA, Coomaraswamy J, Lindau D, Stoltze L, et al. (2006). Abeta42driven cerebral amyloidosis in transgenic mice reveals early and robust pathology. EMBO Rep 7: 940–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Readhead B, Haure-Mirande JV, Funk CC, Richards MA, Shannon P, Haroutunian V, et al. (2018). Multiscale Analysis of Independent Alzheimer’s Cohorts Finds Disruption of Molecular, Genetic, and Clinical Networks by Human Herpesvirus. Neuron 99: 64–82 e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, et al. (2015). limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43: e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrschneider LR, Fuller JF, Wolf I, Liu Y, & Lucas DM (2000). Structure, function, and biology of SHIP proteins. Genes Dev 14: 505–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salih DA, Bayram S, Guelfi S, Reynolds RH, Shoai M, Ryten M, et al. (2019). Genetic variability in response to amyloid beta deposition influences Alzheimer’s disease risk. Brain Commun 1: fcz022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh J, Kino Y, Asahina N, Takitani M, Miyoshi J, Ishida T, et al. (2016). TMEM119 marks a subset of microglia in the human brain. Neuropathology 36: 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims R, van der Lee SJ, Naj AC, Bellenguez C, Badarinarayan N, Jakobsdottir J, et al. (2017). Rare coding variants in PLCG2, ABI3, and TREM2 implicate microglial-mediated innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 49: 1373–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AP, Dong C, Preuss C, Moutinho M, Lin PB-C, Hajicek N, et al. (2020). PLCG2 as a Risk Factor for Alzheimer’s Disease. bioRxiv: 2020.2005.2019.104216. [Google Scholar]

- Viernes DR, Choi LB, Kerr WG, & Chisholm JD (2014). Discovery and development of small molecule SHIP phosphatase modulators. Med Res Rev 34: 795–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Beckmann ND, Roussos P, Wang E, Zhou X, Wang Q, et al. (2018). The Mount Sinai cohort of large-scale genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic data in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Data 5: 180185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Risacher SL, Nho K, Saykin AJ, Wang Z, Shen L, et al. (2019). Targeted genetic analysis of cerebral blood flow imaging phenotypes implicates the INPP5D gene. Neurobiol Aging 81: 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]