Abstract

Research studies focusing on separation anxiety and its relation with other measures of anxiety and personality-relevant variables in community samples are still scarce. This study aimed to describe in a dimensional perspective the relationship between separation anxiety symptoms, anxiety levels, and personality traits in a community sample of Italian emerging adults. A sample of 260 college students [mean age (Mage)=21.22, standard deviation (SD)=1.91, 79.6% females] completed the adult separation anxiety questionnaire-27 (ASA-27), the state and trait anxiety inventory-Y (STAI-Y), and the personality assessment inventory borderline scale (PAI-BOR). ASA-27 was significantly and positively correlated with the PAI borderline scale. The mediation model showed that ASA-27 influenced the PAI-BOR through trait anxiety. Clinical implications of the study for psychotherapy research are discussed.

Key words: Emerging adulthood, adult separation anxiety, trait anxiety, state anxiety, borderline features

Introduction

Adult separation anxiety disorder (ASAD) - diagnosed in adults who have an unusually strong fear or anxiety to separating from people to whom they feel a strong attachment or boundaries - causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, academic, occupational, or other important areas of functioning [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder 5th edition (DSM-5); American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013].

In recent years, specific attention has been given to ASAD. The literature has focused attention on epidemiology prevalence and age of onset - connected with DSM-5 (e.g., Shear, Jin, Ruscio, Walters, & Kessler, 2006; Silove et al., 2015), and comorbidity (e.g., Shear et al., 2006; Silove, Claire, Wagner, Manicavasagar, & Rees, 2010). Moreover, recent papers have focused on the specificity of this diagnosis in the DSM-5 compared with previous versions of the DSM, in which the diagnosis was limited to childhood (e.g., Manicavasagar, Silove, & Hadzi-Pavlovic, 1998; Silove, Manicavasagar, & Pini, 2016). The mentioned studies were mainly carried out on clinical populations and little attention has been given to community samples, in which ASAD clinical diagnosis is not the milestone (Silove et al., 2015; Möller & Bögels, 2016). Moreover, they paid attention to the identification of symptoms of adult separation anxiety from a categorical perspective. Very few papers have addressed adult separation anxiety symptoms from a dimensional approach. This perspective might be useful to create a personality profile in which symptoms relying on emerging factors might describe typical features and declinations of adult separation anxiety at the specific ages in which people are more at risk for ASAD symptoms onset (Silove et al., 2010; Mroczkowski, Goes, Grados, Bienvenu, & Greenberg, 2016). Research studies focusing on separation anxiety, its distinction from other kinds of anxiety, and its relation with personality-relevant variables in community samples are still scarce (Bögels, Knappe & Clark, 2013; Strawn & Dobson, 2017). Concerning, for instance, the important distinction between state and trait anxiety1 (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, and Jacobs, 1983) in one of the few studies carried out on the considered topic, Santorelli (2010) found in a group of college students a stronger correlation between adult separation anxiety and trait anxiety as compared with state anxiety. As for personality variables, for instance, Wilhelm, Boyce, and Brownhill (2004), in a group of teachers trainees, found that separation anxiety was associated with Neuroticism.

Emerging adulthood seems to be a particularly challenging period from the ‘separation anxiety’ point of view. The disturbances derived from ASAD can make normal developmental activities that characterize emerging adulthood (such as moving away from home, getting married, or being an independent person issues) very difficult. Starting from late adolescence to early adulthood, individuals (aged 18-30 years) are asked in terms of developmental-stage requirements to become more independent and explore various life domains, struggling for identity exploration, instability, selffocus, and feeling in-between (Arnett, 1997, 2000, 2006). The term describes primarily young adults living in developed countries who do not have children, do not live in their own homes, or do not have sufficient income to become fully independent. Although adulthood has already been reached, most people do not perceive themselves entirely as adults, based on the belief that they have not fully formed ‘individualistic qualities of character’, such as financial and psychological independence, more responsibilities, and selfsufficiency. In such a contest, the shift towards more adultlike experiences could account, among other aspects, for an increased risk of developing anxiety and mood disorders and specifically of symptoms of separation anxiety (Tanner, 2006; Mabilia, Di Riso, Lis, & Bobbio, 2019).

Furthermore, few studies have investigated separation anxiety in emerging adults as they are preparing themselves to leave their home, usually for the first time, to attend college. In fact, within the emerging adulthood period, university students could be considered a peculiar sample. According to the Italian Institute of Statistics data (ISTAT, 2018), in Italy, 2.113 million university students, aged between 20 to 34 years, graduated. At the same time, youth unemployment is increased with a percentage ranging from 16% to 31.7% among those aged between 15-24 years (ISTAT, 2018). Eurostat (2014) data showed that in Italy around half of Italian young adults live at home up to the age of 35 years, and only a few of them are involved in long-distance romantic relationships and delaying commitment to a stable romantic partner. In this current scenario Italian young adults - in particular University students - have more time to experiment with different life possibilities and as a result they experience for a longer time the period of emerging adulthood (Arnett & Tanner, 2006). On the other hand, this period can delay and make it difficult for them to face their adult responsibilities and to acquire the necessary capacities to stand alone as a self-sufficient person, often through extended post-secondary education (Arnett & Galambos, 2003). Furthermore, in the absence of social safety valves, the prolongation of this transition period can become ‘a combined developmental undertaking’ (Scabini & Cigoli, 2000) of parents and sons/daughters. For Italian emerging adults, the demands for developmentally appropriate levels of separation include not only a physical separation, but an emotional and identity individuation that can be maintained throughout adulthood (Cramer, 2004; Schwartz, Cote & Arnett, 2005; Seligman & Wuyec, 2007; Kroger, Martinussen, & Marcia, 2010), and when experiencing difficulties in relationships with family members and peers (Arnett, 2004; Lewinsohn, Rohde, Seeley, Klein, & Gotlib, 2003). The condition of ‘being a university student’, unemployed, away from home, but often economically dependent from home, seem to create some difficulties in facing the full transition towards adulthood, prolonging the separation/individuation process initiated during adolescence more than necessary; this condition may result in symptoms of separation anxiety in individuals who had not previously experienced significant separation anxiety in childhood.

One of the few dimensional instruments devised to assess separation anxiety disorder symptoms occurring starting the age of 18 years old, is the adult separation anxiety questionnaire (ASA-27, Manicavasagar, Silove, Wagner, & Drobny, 2003), which validity was established in the original study (Manicavasagar, Silove, Curtis, & Wagner, 2000; Seligman et al., 2007). However no empirical investigation was carried out to compare separation anxiety within the important distinction between state and trait anxiety. Moreover, during the emerging adulthood period, separation anxiety can be connected with some clinical features such as emotional lability, interpersonal difficulties, and uncertainty about identity, which are all considered ‘physiological’ due to the transition from adolescence and dependency, to adulthood and autonomy - prolonged in the condition of ‘being a university student’. These features seem to revoke some of the basic components of borderline personality disorders (BPD, DSM-5), a severe personality disorder with features such as emotional lability, impulsivity, interpersonal difficulties, identity disturbance, cognitive impairment, separation anxiety, and fear of abandonment (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). However, some studies introduced a model of borderline psychopathology in which some symptoms are stable/structural and others are more unstable/ transient and may resolve rapidly (Zanarini et al., 2007). This model subdivides borderline features into behavioral aspects that are considered symptomatic and episodic due to developmental issues, and into fixed traits, which are enduring and chronically linked to structured psychopathological features (Skodol et al., 2005). Taking into account the episodic nature of some BPD manifestations in occurrence with specific life events and transient phases, such as the University period and emerging adulthood, our attention was focused on Borderline-like features as measured by the personality assessment inventory-borderline features scale (PAI-BOR) (Morey, 1991, 2007). De Moor, Distel, Trull, and Boomsma (2009) found that the PAI-BOR can be used to study the etiology of BPD features in community samples and to screen for BPD features in nonclinical settings in both genders with different age ranges. In the same direction, Jackson, Sher, Gotham, and Wood (2001) underlined the importance to assess PAI-BOR in the general population. Hence, BPD features may appear as symptoms of a transition period (Seligman et al., 2007), such as emotional lability, interpersonal difficulties, uncertain about identity that could be connected with separation anxiety.

In recent years (Biasi et al., 2017) a significant increase of University students’ access to universities’ psychological services showed a growth in students’ psychological distress. Several studies showed that about one-third/a half of university students present mild to high levels of subjective sufferance and moderate levels of stress-related mental health issues, in particular anxiety and depression (Bayran & Bilgel, 2008; Garlow et al., 2008; Keyes et al., 2012). These concerns found among university students can be considered a public health problem (Biasi et al., 2017), since they can negatively affect students’ ability to adapt and regulate their emotions, consequently influencing their academic performance (Mowbray et al., 2006; Menozzi, Gizzi, Tucci, Patrizi, Mosca, 2016). From this perspective, university psychological services might play a significant role in improving students’ wellbeing and adaptation. An overall assessment of students’ functioning, including separation anxiety symptoms and personality traits, might be fundamental in planning prevention and intervention programs.

To our knowledge, no studies have tried to analyze the peculiarity of emerging adulthood in university students, by distinguishing through a dimensional perspective anxiety separation symptoms, which take into account both traits and state anxiety, and personality features. This paper aimed to try and highlight the boundaries of separation anxiety symptoms, levels of state and trait anxiety, and some personality traits, using respectively the ASA- 27 (Manicavasagar et al., 2003), the state and trait anxiety inventory-Y (STAI-Y) (Spielberger et al., 1983) and PAIBOR (Morey, 1991, 2007) on a community Italian University sample of emerging adults.

The first specific aim of this study was to investigate the possible relationship between separation anxiety measured through the ASA-27 and trait and state anxiety measured through the STAI-Y (Spielberger et al., 1983). A stronger correlation between adult separation anxiety and trait anxiety was expected as compared with state anxiety, as already found by Santorelli (2010) in a group of college students.

A second aim was to identify possible personality vulnerability factors associated with separation anxiety. Although it was expected that in the present sample of emerging adults PAI-BOR will fall in the normal range, PAI-BOR factors were hypothesized as possible developmental issues in emerging adults. For these reasons, significant correlations between separation anxiety and PAI-BOR and related subscales are expected.

Finally, the role of separation anxiety versus trait anxiety on PAI-BOR and subscales were investigated using a mediation model. It was expected that although trait anxiety will have a direct influence on PAI-BOR, separation anxiety will play a significant role as mediator through an indirect effect on PAI-BOR.

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedure

A total of 260 Italian college students attending the University of Padova took part in the current study. This sample was predominantly female (207, 79.6%) and age ranged between 18 to 31 years [mean age (Mage)=21.22, standard deviation (SD)=1.91]. All participants indicated they had never been hospitalized or treated because of psychiatry symptoms in the past two years. Exclusion criteria included participants who presented a clinical cutoff on PAI-BOR inventory. Very few (<3% of the total sample) reported previous psychological counseling or intervention in the past two years for mild problems, yet no separation anxiety problems. Only 7 subjects (2.8%) of the total sample were living together with a partner and just one (0.4%) was married. Trained university master students supervised the participants while compilating the self-report measures during regular university hours. The study procedure was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Italian law 196/2003, UE GDPR 679/2016). Participants provided their written assent before participation. All subjects were informed that data were collected in an anonymous form, that they could omit any information they did not wish to provide, and that they could withdraw from the study at any moment.

Measures

Adult separation anxiety-27

The ASA-27 (Manicavasagar et al., 2003) is a self-report inventory designed to assess separation anxiety symptoms in adulthood. It is composed of 27 items rated on a four-point scale (from 0=‘this has never happened’ to 3=‘this happens very often’). The items are summed to obtain a total score for ASA-27, where higher scores indicate greater separation anxiety symptoms severity. Scores range from 0 to 81. The ASA-27 shows a good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89), as well as concurrent validity (Manicavasagar et al., 1998, 2000, 2003). The ASA-27 has been also translated into the Italian language and validated on a sample of Italian university students, showing good psychometric properties (Mabilia et al., 2019). In this study ASA-27 showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 (95% confidence interval, CI=[0.87, 0.91]).

Personality assessment inventory

The PAI (Morey, 1991, 2007) provides relevant information for clinical diagnosis, treatment planning, and screening for psychopathology. The PAI is a 344-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure response style, personality, and symptoms of mental disorder. Each item is rated on a four-point scale (from ‘false, not at all true’ to ‘true’). The PAI consists of 22 non-overlapping full scales including 4 validity scales, 11 clinical scales, 5 treatment scales, and 2 interpersonal scales. PAI has been validated in Italy on a sample of 1.538 participants, showing good psychometric properties (Pignolo et al., 2018). In the present study, BOR and its subscales were considered. This scale assesses a personality functioning of borderline level, including unstable and fluctuating personal relations, impulsivity, emotional lability and instability as well as uncontrolled rage. It included four subscales: PAI-borderline affective instability (BORA) focused on emotional sensibility, fast mood changes, and scarce emotional control; PAI-borderline identity problems (BORI) focuses on uncertainty concerning basic life questions and issues, feeling of void, dissatisfaction, and lacking aims; PAI-borderline negative relationships (BORN) focuses on a history of intense and ambivalent relationships, in which the individual feels as if they are taken advantage of and betrayed; PAI-borderline selfharm (BORS) focuses on impulsivity in domains with a high potential for negative consequences. In this study, BOR Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84 (95% CI=[0.81, 0.87]), while the Cronbach’s alpha of BOR subscales were 0.78 (95% CI=[0.73, 0.81]) for BORA, 0.73 (95% CI=[0.68, 0.78]) for BORI, 0.55 (95% CI=[0.45, 0.63]) for BORN, and 0.56 (95% CI=[0.47, 0.64]) for BORS.

State and trait anxiety inventory-Y

The STAI-Y (Spielberger et al., 1983) is a commonly used tool to measure anxiety (Spielberger et al., 1983). It consists of 40 items divided into two subscales of 20 items each, state anxiety, which assesses current anxiety symptoms, and trait anxiety, which assesses stable individual differences in anxiety proneness and refers to a general tendency to respond with anxiety to perceived threats in the environment. Items are based on a four-point scale (from 0=‘almost never’ to 3=‘almost ever’) and added to yield total subscale scores. The STAI-Y has been also translated into the Italian language and validated on a sample of adolescents and adults (Spielberger, Pedrabissi, & Santinello, 2012). In this study Cronbach’s alpha for STAI-Y trait was 0.89 (95% CI=[0.88, 0.91]) and for STAI-Y state was 0.93 (95% CI=[0.92, 0.94]).

Data analysis

The analyses were carried out using SPSS 23.0 and Hayes’ PROCESS model 4. Correlation analysis between ASA-27, STAI-Y, and PAI-BOR total score and subscales were performed. Correlations were interpreted when they were significant (P<0.05), and also Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1992; Richardson, 2011) was taken into account. Cohen (1992) suggested that d=0.2 be considered a ‘small’ effect size, 0.5 represents a ‘medium’ effect size and 0.8 a ‘large’ effect size.

SPSS macro (PROCESS, Model 4) developed by Preacher and Hayes (2008) was used to assess the mediational model, namely the direct effect of trait anxiety and the indirect effect through separation anxiety on Borderline Features of emerging adults. Age and Gender were used as covariates. First, the total effect (i.e., the total effect model) of trait anxiety on BOR and separately of its subscales, without including separation anxiety as mediator (Model 4), was assessed, then the aim has been to include the mediator (i.e., separation anxiety, Model 4) to test the significance of the direct and indirect effects of trait anxiety on the above-mentioned outcomes. This allowed the authors to observe how the total effects changes and to evaluate the role of the mediator (i.e., the mediated effect). The bootstrapping method (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) was applied to all the mediation models. Specifically, 5000 bootstrap sample was drowned from the full data and 95% confidence interval was used to determine the significance of the mediating effect. The significant mediating effect would be identified if the confidence interval excluded 0. To calculate the ratio of the indirect effect on the total effect, proportion mediated (PM=indirect effect/total effect) was calculated.

Results

Preliminary analysis

Before running analyses, borderline subscales were examined to check eventual clinical scores in the present sample. Morey (2007) suggested that at least three among the four subscales with scores higher than 70, indicate a psychopathological profile in the borderline dimensions. Results showed that none of the participants presented such a clinical profile. So, in this study, borderline characteristics can be considered as dimensional aspects in the transition to adulthood.

Correlation analysis

Correlations between ASA-27 with STAI-Y trait and state anxiety scales, and BOR and its subscales were all significant (P<0.01) with the only exception of BORS (Table 1). However, according to Cohen’s d ranges, only the correlations between ASA-27, STAI-Y trait anxiety, and BORI problems showed at least a medium effect size. All other correlations showed a small effect size.

Mediational model

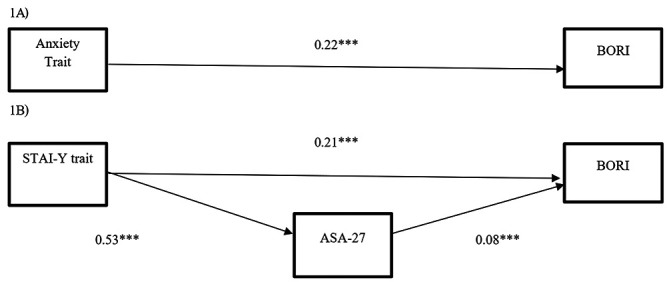

Given these results, a mediation model was carried out to assess the direct and indirect effect of separation anxiety on BORI as reported in Figure 1. First, we checked the total effect (i.e., the total effect model) of trait anxiety on BORI without including separation anxiety as mediator, which was then included (i.e., separation anxiety) to test the direct and indirect effect of trait anxiety. Age and gender were used as covariates.

The full model accounted for about 52% of the explained variability in BORI scores (R2=0.522) and was significant (F (4,255)=69.54 P<0.001). STAI-Y trait statistically significantly predicts ASA-27 score (b=0.533, t=10.36, P<0.001). This effect could be interpreted as significantly positive because the bootstrap confidence interval was above zero (CI=[0.18, 0.25]). Participants with higher trait anxiety showed higher separation anxiety. STAY-Y trait statistically significantly predict BORI scores (b=0.216, t=11.11, P<0.001). This effect could be interpreted as significantly positive because the bootstrap confidence interval was above zero (CI=[0.43,0.63]). Participants with higher trait anxiety showed higher BORI features. ASA-27 statistically significantly predicts BORI score (b=0.080, t=4.08, P<0.001) this effect could be interpreted as significantly positive because the bootstrap confidence interval was above zero (CI=[0.04, 0.11]). Participants with higher separation anxiety showed higher BORI problems. Age and gender did not have significant effect on BORI (b= –0.0076, t= –0.08, P=0.93; b=0.53, t=1.21, P=0.22).

Table 1.

Correlations between adult separation anxiety-27 score, state and trait anxiety inventory-Y trait, and borderline total score and subscales (N=260).

| STAI-Y state | STAI-Y trait | BOR | BORA | BORI | BORN | BORS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA-27 | 0.44** | 0.55** | 0.48** | 0.34** | 0.54** | 0.39** | ns |

| STAI-Y state | 0.75** | 0.54** | 0.46** | 0.53** | 0.35** | 0.19** | |

| STAI-Y trait | 0.70** | 0.60** | 0.70** | 0.49** | 0.19** | ||

| BOR | 0.81** | 0.78** | 0.78** | 0.58** | |||

| BORA | 0.48** | 0.47** | 0.40** | ||||

| BORI | 0.50** | 0.20** | |||||

| BORN | 0.35** |

STAI-Y, state and trait anxiety inventory-Y; BOR, borderline; BORA, borderline affective instability; BORI, borderline identity problems; BORN, borderline negative relationships; BORS, borderline self-harm; ASA-27, adult separation anxiety-27. **P<0.01; *P<0.05.

Figure 1.

Total effect (A) and the direct and indirect effects (B) of trait anxiety on personality assessment inventory borderline scale-borderline identity problems (BORI), mediated by the presence of adult separation anxiety-27 (ASA-27) among emerging adults; STAI-Y, state and trait anxiety inventory-Y; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

STAI-Y trait showed a significant direct effect (b=0.22, t=11.11, P<0.001, CI=[0.177, 0.2541]) on BORI. STAI-Y showed indirect effect on BORI as mediated by ASA-27 (b=0.04, CI=[0.0212. 0.0659]). Participants with higher trait anxiety had higher separation anxiety; this score was associated with higher borderline identity problems because the bootstrap confidence interval for both was entirely above zero.

Discussion

The general purpose of the current study was to connect through a dimensional perspective, separation anxiety symptoms, considering both state and trait anxiety, and some borderline personality features in a non-clinical sample of Italian university emerging adults.

ASAD symptoms were scarcely explored in community samples, although they can be considered a key component in the comprehension of critical life periods, such as emerging adulthood (e.g., Bögels et al., 2013; Moller et al., 2016; Strawn & Dobson, 2017). As a matter of fact, ISTAT data (2012, 2017, 2018) indicated how, in the Italian context, young adults leave home later than they used to and/or present difficulty in finding a job, leading to some difficulties in the transition to adulthood. Moreover, several studies were carried out focusing on a categorical approach to explore adult separation anxiety, stressing the importance of the clinical diagnosis according to specific criteria (Silove et al., 2010; Mroczkowski et al., 2016). On the other hand, a dimensional approach where ASAD symptoms, rather than criteria, are assessed might be more appropriate in not-referred samples. This perspective allowed us to explore impaired functioning in specific domains, although where there are no cues for psychopathology or frank clinical diagnosis.

Investigating possible relations between separation anxiety symptoms, trait and state anxiety, all correlations were significant. However, according to Cohen’s d ranges (1992) ASA-27 total score showed stronger associations with STAI-Y trait compared with state anxiety. This pattern was expected and confirmed by a previous study (Santorelli, 2010).

Different personality vulnerability features associated with adult separation anxiety emerged. In particular, BOR seemed to represent some core psychological aspects typical of the emerging adulthood period, such as emotional lability, interpersonal difficulties, and the struggle to define identity (APA, 2000). As expected, in the present sample, BOR scores did not show a psychopathological distribution, but they helped as indicators useful to explore the specificity of this peculiar life period. Findings suggested positive correlations, with medium effect size, between ASA-27-total score and BORI scores. In emerging adulthood, the struggle to deal with developmental trajectories of separation/individuation processes, seemed to be related to transient difficulties in defining identity, such as prolonged identity formation in the absence of external scaffolding, leading to uncertainty and confusion in several potential identitary choices (Schwartz et al., 2005).

Furthermore, the mediation model highlighted that anxiety traits not only seem to predict identity problems but separation anxiety - as measured with the ASA-27 - seem to significantly and positively mediate this relationship, although the regression coefficients are of small size. Still, the present sample is constituted of healthy participants who, differently from those reporting a clinical diagnosis, tend to be more heterogeneous in regards to the features underlying their functioning (McGorry & van Os, 2013). As such, in a healthy population, trait anxiety and separation anxiety might not be the main components explaining identity problems, albeit they were highly significant (P<0.001) and accounted for a high amount of variance (R2=52%) of the sample identity problems formation. Empirical studies concerning the process of identity foundation in adults showed that identity continues to develop during adulthood for many people (Cramer, 2004; Kroger et al., 2010). Findings of this study confirmed how, in this specific life period, trait anxiety contributed to the struggle in individuating an own identity (Seligman et al., 2007), but they also showed that they could become tougher if separation anxiety is experienced. In sum, the searching for identity and the symptoms of separation anxiety could be important aspects in the shift towards the adult age. Up until now empirical contributions to these topics were scarce and therefore the initial findings of this study need further explorations.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations must be considered in this study.

First, only data from college students were collected and the sample was not balanced for gender, which restricts the generalizability of findings related to adult separation anxiety. Moreover, this is a cross-sectional study and the regression coefficients of the mediation models are of small size; nevertheless, the present study has been useful to identify relevant variables that could be used for future longitudinal studies. Furthermore, based on the present findings, future studies should also consider other relevant personality dimensions for which trait and separation anxiety could be predictive, for instance referring to the dependent personality dimension (APA, 2000, 2013).

This is the first study that evaluated the relationship between separation anxiety and components of PAI-Borderline Personality problems in a non-clinical sample of emerging adults. Specifically, this study focused especially on certain types of symptoms of separation anxiety, on state and trait anxiety and on identity problems: all these problems could be relevant in comprehending more thoroughly the transition phase lived by emerging adults.

To deeply investigate the symptoms underlying separation anxiety in a non-clinical sample of emerging adults can be important in several contexts, in particular for clinical services aimed at University Students. Here, most of the self-referred patients present a high level of subjective sufferance without effective maladjustment or significant life impairment. In the diagnostic assessment of such a population, considering separation anxiety issues and discriminating between general trait and state anxiety, keeping in mind the effects on identity construction, could be particularly worthy of attention when planning interventions and treatments as well as prevention practices. In the context of borderline personality features and related disorder, prevention interventions are considered complex tasks, since there are multiple risk factors at the social, biological and psychological levels, which are subject to multifocality (Chanene & McCutcheon, 2013). Indeed, an indicated prevention of borderline personality should target also its underlining dimensions referring, for instance, to substance abuse, self-harming behavior or disruptive behavior (e.g., Chanene & McCutcheon, 2013). In this regard, the present paper suggests to further consider the role of separation anxiety for the prevention of problems in identity formation referred to borderline personality features. Cognitive behavioral therapy and its constitutive practices are reported in the literature as favored within the treatment of separation anxiety, anxiety problems and related disorders in children older than 7 years old and adolescents (Ehrenreich, Santucci & Weiner, 2008), including practices of cognitive restructuring - more indicated for adolescents - and psychoeducation. Psychoeducational interventions aiming to support identity development and psychological adjustment should be tailored considering individual differences and specific psychological needs as they allow to explore the multiple aspects referred to the self and to support an integrated functioning throughout life transition phases (Cordeiro, Paixao, Lens, Lacante & Luyckx, 2016).

Differently, interventions in such a community sample of emerging adults without having reached psychopathological levels of symptoms, from a psychodynamic perspective, is considered a ‘supportive’ intervention to the Ego functioning. Supportive psychotherapy is a type of psychotherapy that seeks to reduce psychological conflict and to strengthen a patient’s defenses through the use of various techniques, both psychodynamic or cognitive-behavioral, but definitively fixed in sustaining the patient’s resources in effectively coping with various life stressors. Supportive psychotherapy is geared towards straightforward therapeutic goals, such as helping patients to explore and have a better understanding of their current situation, share their feelings and thoughts, to find hope despite difficult circumstances and reinforcing and strengthening their resilience to the challenges they face. Reinforcing features such as identity values, relationships strength, the desire for separation from the original family and openness to more adult responsibilities and coping strategies permit, in such a perspective, to consider separation anxiety and global anxiety symptoms as the effects of evolutive tasks.

A thorough assessment of these dimensions (identity, anxiety, and separation anxiety) could guide the therapist in the planning of tailored supportive psychotherapy able to increase patients’ ability to adapt to common life challenges, maintaining or building up their self-esteem, towards reducing or alleviating symptoms of depression, anxiety, and other aspects of maladjustment.

Conclusions

The present paper supports the consideration of anxiety symptoms and separation anxiety for identity formation and stability, particularly relevant in the context of emerging adulthood. More specifically, the consideration of a sample of university students, as exemplifying the now prolonged period of transition from the dependency of adolescence to the autonomy of adulthood, shows the importance of providing effective support in facing anxiety symptoms, thus allowing a smoother shift toward the acquisition of more adult responsibilities and competences as well as strengthening a stable identity as selfsufficient adults.

Acknowledgments

The Department of Developmental Psychology and Socialization supported this research. The first Author is thankful to the Fondazione Bruno Kessler (FBK) for the Ph.D. grant.

Footnotes

1 Trait anxiety assesses stable individual differences in anxiety proneness and refers to a general tendency to respond with anxiety to perceived threats in the environment; state anxiety assesses current anxiety symptoms.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J. (1997). Young people’s conceptions of the transition to adulthood. Youth and Society, 29, 1-23. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469-480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: the winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J. (2006). The psychology of emerging adulthood: what is known, and what remains to be known? Arnett J.J., Tanner J.L. (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 303-330). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Book. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J., Galambos N. L. (2003). Culture and conceptions of adulthood. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, (100), 91-98. doi: 10.1002/cd.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J., Tanner J. L. (2006). Emerging adults in America: coming of age in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bayran N., Bilgel N. (2008). The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43, 667-672. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0345-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biasi V., Cerutti R., Mallia L., Menozzi F., Patrizi N., Violani C. (2017). (Mal)adaptive psychological functioning of students utilizing University Counseling Services. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(403), 1-8. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels S. M, Knappe S., Clark L. A. (2013). Adult separation anxiety disorder in DSM-5. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 663-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanene A. M., McCutcheon L. (2013). Prevention and early intervention for borderline personality disorder: current status and recent evidence. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202, s24-s29. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98-101. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro P. M., Paixao M. P., Lens W., Lacante M., Luyckx K. (2016). Parenting style, identity development, and adjustment in carrer transitions: the mediating role of psychological needs. Journal of Carrer Development, 1-15. doi:10.1177/0894845316672742 [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. (2004). Identity change in adulthood: the contribution of defense mechanisms and life experiences. Journal of Research in Personality, 38(3), 280-316. [Google Scholar]

- de Moor S. M., Distel M. A., Trull T. J., Boomsma D. I. (2009). Assessment of borderline personality features in population samples: is the personality assessment inventoryborderline features scale measurement invariant across sex and age? Psychological Assessment, 21(1),125-130. doi: 10.1037/a0014502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich J. T., Santucci L. C., Weiner C. L. (2008). Separation anxiety disorder in youth: phenomenology, assessment, and treatment. Behavioral Psychology/Psicologìa Conductual, 16(3), 389-412. doi: :10.1901/jaba.2008.16-389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. (2012). Data from the Italian Institute of Statistics. Retrieved from: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. (2017). Data from the Italian Institute of Statistics. Retrieved from: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT, (2018). Data from the Italian Institute of Statistics. Retrieved from: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K. M., Sher K. J., Gotham H. J., Wood P. K. (2001). Transitioning into and out of large effect drinking in young adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 378-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes C., Eisenberg D., Perry G., Dube S., Kroenke K., Dhingra S. (2012). The relationship of level of positive mental health with current mental disorders in predicting suicidal behavior and academic impairment in college students. Journal of American College Health, 60, 126-133. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.608393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger J., Martinussen M., Marcia J. E. (2010). Identity status change during adolescence and young adulthood: a metaanalysis. Journal of Adolescence, 33(5), 683-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P. M., Rohde P., Seeley J. R., Klein D. N., Gotlib I. H. (2003). Psychosocial functioning of young adults who have experienced and recovered from major depressive disorder during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(3), 353-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabilia D., Di Riso D., Lis A., Bobbio A. (2019). A prediction model for separation anxiety: the role of attachment styles and internalizing symptoms in Italian young adults. Journal of Adult Development, 1-9. [Google Scholar]

- Manicavasagar V., Silove D., Curtis J., Wagner R. (2000). Continuities of separation anxiety from early life into adulthood. Journal of Anxiety Disorder, 14(1), 1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manicavasagar V., Silove D., Hadzi-Pavlovic D. (1998). Subpopulations of early separation anxiety: relevance to risk of adult anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 48(2-3), 181-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manicavasagar V., Silove D., Wagner R., Drobny J. (2003). A self-report questionnaire for measuring separation anxiety in adulthood. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 44(2), 146-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry P., van Os J. (2013). Redeeming diagnosis in psychiatry: timing versus specificity. The Lancet, 381(9863), 343-345. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menozzi F., Gizzi N., Tucci M. T., Patrizi N., Mosca M. (2016). Emotional dysregulation: the clinical intervention of Psychodynamic University Counselling. Journal of Education, Cultural and Psychologial Studies, 14, 169-182. doi: 10.7358/ecps-2016-014meno [Google Scholar]

- Möller E. L., Bögels S. M. (2016). The DSM-5 dimensional anxiety scales in a Dutch non-clinical sample: psychometric properties including the adult separation anxiety disorder scale. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 25(3), 232-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey L. C. (1991). Personality assessment inventory (pp. 11-46). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Morey L. C. (2007). Personality assessment inventory (PAI): professional manual (2nd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray C. T., Megivern D., Mandiberg J. M., Strauss S., Stein C. H., Collins K. (2006). Campus mental health services: recommendations for change. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76, 226-237. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.2.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczkowski M., Goes F. S., Grados M. J., Bienvenu O., Greenberg B. (2016). Dependent personality, separation anxiety disorder and other anxiety disorders in OCD. Personality and Mental Health, 10, 22-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignolo C., Di Nuovo S., Fulcheri M., Lis A., Mazzeschi C., Zennaro A. (2018). Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the personality assessment inventory (PAI). Psychological Assessment, 30(9), 1226-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., Hayes A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40(3), 879-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson G. P. (2011). Reflections on the foundations of system dynamics. System Dynamics Review, 27(3), 219-243. [Google Scholar]

- Santorelli N. T. (2010). Developmental antecedents of symptoms of adult separation anxiety in young adult college students. Dissertation, Georgia State University. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/psych_diss/75. [Google Scholar]

- Scabini E., Cigoli V. (2000). Il famigliare. Legami, simboli e transizioni (p. 142). Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. J., Cote J., Arnett J. J. (2005). Identity and Agency in Emerging Adulthood: Two Developmental Routes in the Individualization Process. Youth & Society, 37(6), 201-229. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman L. D., Wuyek L. A. (2007). Correlates of separation anxiety symptoms among first-semester college students: an exploratory study. Journal of Psychology, 141(2), 135-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear K., Jin R., Ruscio A. M., Walters E. E., Kessler R. C. (2006). Prevalence and correlates of estimated DSM-IV child and adult separation anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(6), 1074-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silove D., Alonso J., Bromet E., Gruber M., Sampson N., Scott K., Andrade L., Benjet C., Caldas de Almeida J.M., De Girolamo G., de Jonge P., Demyttenaere K., Fiestas F., Florescu S., Gureje O., He Y., Karam E., Lepine J. P., Murphy S., Villa-Posada J., Zarkov Z., Kessler R.C. (2015). Pediatric-onset and adult-onset separation anxiety disorder across countries in the world mental health survey. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(7), 647-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silove D., Claire L. M., Wagner R., Manicavasagar V., Rees S. (2010). The prevalence and correlates of adult separation anxiety disorder in an anxiety clinic. BMC Psychiatry, 10(21), 1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silove D., Manicavasagar V., Pini S. (2016). Can separation anxiety disorder escape its attachment to childhood? Journal of World Psychiatry, 15(2), 113-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol A. E., Oldham J. M., Bender D. S., Dyck I. R., Stout R. L., Morey L. C., Shea M. T., Zanarini M. C., Sanislow C. A., Grilo C. M., McGlashan T. H., Gunderson J. G. (2005). Dimensional representations of DSM-IV personality disorders: relationships to functional impairment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(10), 1919-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C. D., Gorsuch R. L., Lushene R., Vagg P. R., Jacobs G. A. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C. D., Pedrabissi L., Santinello M. (2012). STAI state-trait anxiety inventory forma Y: manuale. Firenze: Giunti O.S. Organizzazioni speciali. [Google Scholar]

- Strawn J. R., Dobson E. T. (2017). Individuation for a DSM- 5 disorder: adult separation anxiety. Depression and Anxiety, 34(12), 1082-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner J. L. (2006). Recentering during emerging adulthood: A critical turning point in life span human development. Arnett J. J., Tanner J. L. (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 21-55). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm K., Boyce P., Brownhill S. (2004). The relationship between interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety disorders and major depression. Journal of Affect Disorder, 79(1-3), 33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]