Abstract

Lewy bodies are pathological protein inclusions present in the brain of patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD). These inclusions consist mainly of α-synuclein with associated proteins, such as parkin and its substrate aminoacyl tRNA synthetase complex-interacting multifunctional protein-2 (AIMP2). Although AIMP2 has been suggested to be toxic to dopamine neurons, its roles in α-synuclein aggregation and PD pathogenesis are largely unknown. Here, we found that AIMP2 exhibits a self-aggregating property. The AIMP2 aggregate serves as a seed to increase α-synuclein aggregation via specific and direct binding to the α-synuclein monomer. The co-expression of AIMP2 and α-synuclein in cell cultures and in vivo resulted in the rapid formation of α-synuclein aggregates with a corresponding increase in toxicity. Moreover, accumulated AIMP2 in mouse brain was largely redistributed to insoluble fractions, correlating with the α-synuclein pathology. Finally, we found that α-synuclein preformed fibril (PFF) seeding, adult Parkin deletion or oxidative stress triggered a redistribution of both AIMP2 and α-synuclein into insoluble fraction in cells and in vivo. Supporting the pathogenic role of AIMP2, AIMP2 knockdown ameliorated the α-synuclein aggregation and dopaminergic cell death in response to PFF or 6-hydroxydopamine treatment. Taken together, our results suggest that AIMP2 play a pathological role in the aggregation of α-synuclein in mice. Since AIMP2 insolubility and coaggregation with α-synuclein have been seen in the PD Lewy body, targeting pathologic AIMP2 aggregation might be useful as a therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative α-synucleinopathies.

INTRODUCTION

Lewy bodies (LBs) are α-synuclein intracellular inclusions that pathologically define several neurodegenerative diseases including PD, diffuse LB disease, and multiple system atrophy (1). In particular, point mutations and multiplication of α-synuclein are linked to PD, and the presence of α-synuclein and ubiquitin positive Lewy inclusion has been used as a diagnostic hall mark for PD (2, 3). α-synuclein is an intrinsically unstructured protein with a physiological function in vesicle trafficking at synaptic membranes (4). Several alterations on this gene can enhance its tendency to be transformed into beta sheet structured aggregates. These modifications include an accumulation of α-synuclein, point mutations (A30P, A53T, and E46K), post-translational modifications (nitrosylation, S129 or Y39 phosphorylation, dopamine conjugation, and C-terminal truncation), and association with other proteins (5–9). Despite extensive studies on direct modifications and the central role of α-synuclein in LB-like pathology in cells and animal models, the pathological roles of other proteins in association with α-synuclein are largely unknown.

AIMP2 is a pathogenic substrate for parkin because AIMP2 is accumulated in brains of parkin knockout mice and postmortem brains from juvenile patients with PD harboring parkin deletion or sporadic patients with PD (10–13). Under physiological conditions, AIMP2 is assembled into a protein complex called aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (ARS) complex, which is composed of eight different ARS and three auxiliary noncatalytic proteins (AIMP1, AIMP2, and AIMP3) (14). Under pathological PD conditions with parkin or VPS35 dysfunction, proteasomal or lysosomal targeting and degradation of AIMP2 are compromised, resulting in upregulation and nuclear translocation of AIMP2 and interaction with nuclear enzyme poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) (12, 15). AIMP2 interaction with PARP1 can cause the over-activation of PARP1 and production of poly (ADP-ribose), which mediates energy depletion and distinct cell death pathway called parthanatos (16). In addition to the cell death execution, AIMP2 accumulation is associated with its co-localization with α-synuclein in LB of postmortem brains from patients with PD (11, 13). Moreover, AIMP2 overexpression in cell culture has a tendency to form aggresome-like puncta (17). The amyloid beta precursor protein was found to interact with AIMP2 in a separate unbiased screening (18). Together, these reports suggest that AIMP2 has a potential role in aggregate formation associated with PD and other proteinopathies. Since AIMP2 accumulation has been identified in many cases of PD and its accumulation is rather specific to the ventral midbrain (VM) among other brain regions, understanding AIMP2 in α-synuclein aggregation might provide critical insights into pathways to PD-specific LB pathogenesis.

RESULTS

AIMP2 self aggregation and toxicity

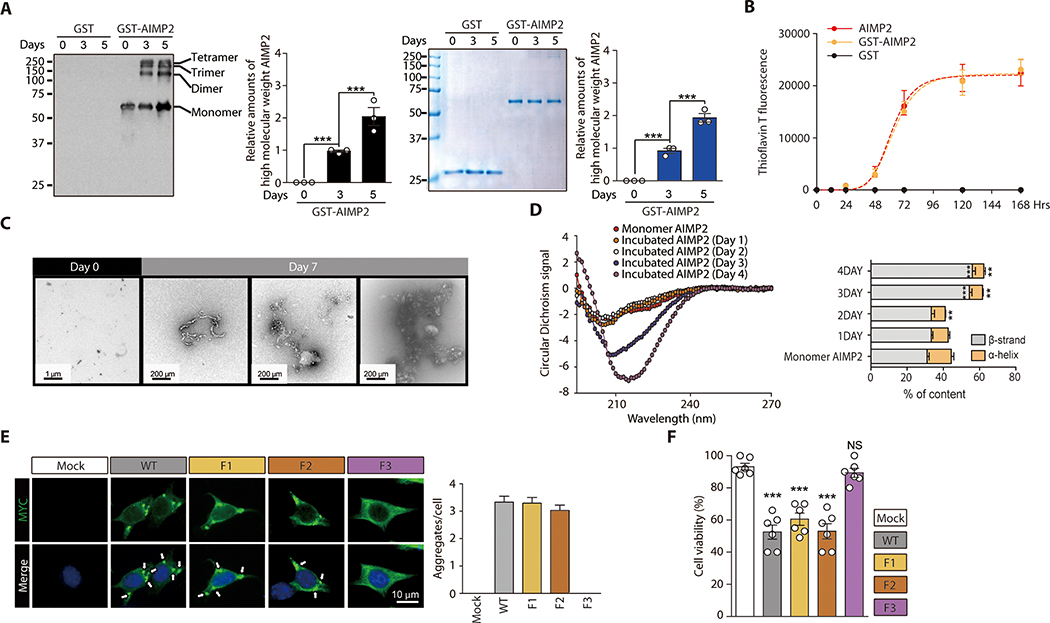

AIMP2 has been found in the Lewy body (LB) inclusion of patients with PD, and its aggregate-like puncta formation has been shown in cell culture experiments (17). Based on the correlative presence of AIMP2 and α-synuclein in insoluble aggregates, we hypothesized that AIMP2 might play a role in the active formation of LB pathology. To determine the potential pathologic role of AIMP2, we sought to determine whether AIMP2 itself might possess an amyloidogenic property to self aggregate. In vitro incubation of purified recombinant GST-AIMP2-FLAG (fig. S1A) resulted in an increase in the high molecular weight oligomeric species of AIMP2 as determined by a Western blot analysis using anti-AIMP2 antibody or Coomassie staining (Fig. 1A). To further evaluate the amyloidogenic tendency of AIMP2 in vitro, recombinant GST-AIMP2-FLAG or AIMP2-FLAG (fig. S1B) was incubated in sodium acetate buffer and subjected to fluorescence reading afforded by amyloid-sensitive thioflavin T (ThT). The incubation of GST-AIMP2-FLAG or AIMP2-FLAG alone resulted in a robust increase in ThT fluorescence with a maximum intensity at 5–7 days (120–168 Hrs) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Amyloid-like self-oligomerization and cell toxicity by AIMP2.

(A) Aggregation of recombinant GST-AIMP2-FLAG (50 uM) in 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 7.5) during in vitro incubation based on Western blot analysis and Coomassie brilliant blue staining. Quantification of AIMP2 Western blots and Coomassie bands (n = 3).

(B) Amyloid formation for GST, GST-AIMP2-FLAG or AIMP2-FLAG (50 uM) incubated in vitro for indicated days determined by ThT fluorescence staining (n = 3).

(C) Ultrastructure of native or aggregated recombinant GST-AIMP2-FLAG (7 d incubation) monitored by TEM.

(D) CD spectra of AIMP2 monomer and aggregates formed during incubation for the indicated days (left panel). Secondary structure analysis by Dichroweb (n =3 experiments, right panel, statistical comparisons with monomer AIMP2)

(E) Aggregate formation in SH-SY5Y cells transfected with MYC-tagged wild type AIMP2 (WT), and deletion mutants monitored by immunofluorescence (left panel). Quantification of aggregate puncta number per cell (n = mock 136, WT 115, F1 124, F2 120 cells total from 6 slides, right panel).

(F) Trypan blue exclusion cell viability assay for SH-SY5Y cells transfected with the indicated constructs (48 hrs) (n = 6 per group).

Quantified data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA test with Tukey post-hoc analysis, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; NS: not significant.

We next examined the ultrastructure of AIMP2 aggregate using a transmission electron microscope (TEM). The TEM analysis revealed the formation of a heterogeneous string- or globular-shaped aggregate by GST-AIMP2-FLAG in vitro (Fig. 1C). We assessed alteration of the secondary structure of AIMP2-FLAG during aggregation using a circular dichroism (CD) analysis. The CD analysis revealed alterations of CD signal curves at 3 and 4 days of AIMP2 incubation, indicating an increase in β-strand content during the AIMP2 aggregation (Fig. 1D). The motif necessary for AIMP2 aggregation was monitored by AIMP2 deletion mutants (fig. S1C). Equal expression of MYC-tagged AIMP2 (AIMP2 WT) and deletion mutants (F1, and F2) in SH-SY5Y cells resulted in an aggregate puncta formation with a similar extent (fig. S1C and Fig. 1E). The C-terminus GST-like domain of AIMP2 (F3 mutant) failed to form an aggregate (Fig. 1E). Consistent with aggregate formation by AIMP2 and its deletion mutants, the expression of full length AIMP2 and deletion mutants F1, and F2 led to comparable cell death in SH-SY5Y cells whereas the F3 fragment failed to induce cellular toxicity (Fig. 1F).

Specific interaction of AIMP2 accelerates α-synuclein aggregation

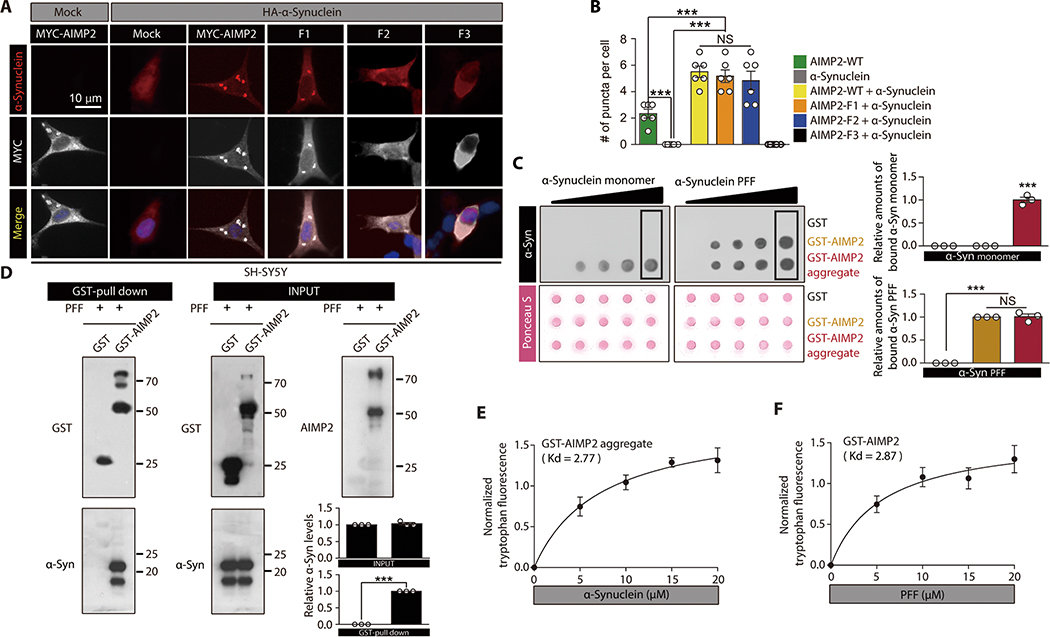

Next we sought to determine the potential role of the AIMP2 aggregate in α-synuclein interaction and aggregation. The transfection of MYC-AIMP2 in SH-SY5Y cells led to the formation of an aggregate, and this aggregation tendency was enhanced by HA-α-synuclein (Fig. 2A,B). Similarly, F1, and F2 AIMP2 fragment expression with HA-α-synuclein also led to aggregate formation which was positive for both AIMP2 and α-synuclein (Fig. 2A,B). The α-synuclein aggregates mainly colocalized with AIMP2-positive aggregates. Consistent with an enhancement of the aggregate formation, the cell viability was further reduced through a coexpression of AIMP2 full length or F1, F2 deletion mutants with HA-α-synuclein as compared to AIMP2 alone (Fig. S2A). However, HA-α-synuclein only or its expression with the F3 AIMP2 fragment failed to form any aggregates with no cellular toxicity (Fig. 2A, B, and fig. S2A).

Figure 2. Interaction between AIMP2 and α-synuclein is conformation specific.

(A) Immunofluorescence images showing co-localization and perinuclear aggregation of α-synuclein with AIMP2 in SH-SY5Y cells with the indicated transfections. The MYC signal is peudo-colored for original green fluorescence.

(B) Quantification of aggregates puncta with AIMP2 or α-synuclein in panel A (n = 6 slides per group, analyzed cell number is presented in data file S1)

(C) Dot blot analysis showing specific interaction of either α-synuclein monomer with AIMP2 aggregate or PFF with both monomeric and aggregate AIMP2. Equal loading was confirmed by Ponceau S staining. Affinity association of monomeric or fibril α-synuclein with blotted proteins were evaluated by using anti-α-synuclein antibody. Quantification of the boxed dot blot intensities (n = 3, right panel).

(D) Direct physical association of recombinant AIMP2 with PFF determined by a GST pull down assay. Quantification of Western blots (n = 3, right panel).

(E) Tryptophan fluorescence measurement of aggregated GST-AIMP2-FLAG (10 uM) incubated with increasing amounts of recombinant α-synuclein (n = 4 per group).

(F) Tryptophan fluorescence measurement of GST-AIMP2-FLAG (10 uM) incubated with increasing amounts of sonicated recombinant PFF (n = 4 per group).

Quantified data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA test with Tukey post-hoc analysis or unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, ***p < 0.001; NS: not significant.

AIMP2 itself has been shown to induce PARP1-dependent cytotoxicity (parthanatos) via nuclear translocation. Pharmacological inhibition of PARP1 activation with its inhibitor 3AB treatment largely prevented cellular toxicity induced by AIMP2 alone or AIMP2/α-synuclein coexpression (fig. S2B). However, there are still 20%, or 40% cell toxicity induced by AIMP2 alone or AIMP2/α-synuclein coexpression, respectively, which are not reversed with PARP1 inhibition (fig. S2B). AIMP2 nuclear translocation was mitigated with α-synuclein coexpression, whereas α-synuclein itself failed to show nuclear translocation (fig. S2C,D). Since AIMP2 expression alone resulted in a substantial cellular toxicity, the dosages of AIMP2 transfection were titrated to understand synergistic interaction of AIMP2 and α-synuclein. With 50 ng of AIMP2 transfection, there was no cellular toxicity, but α-synuclein coexpression led to about 40% cell death (fig. S2E). In this condition of AIMP2/α-synuclein interaction, there was a formation of the aggregate positive for both proteins. Both cytotoxicity and aggregate formation increased with an increasing dose of AIMP2 transfection (fig. S2E,F). We also evaluated the functional status of the proteasome and autophagy degradation pathways influencing aggregate formation and degradation. SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with MYC-AIMP2 with or without HA-α-synuclein, and proteasomal and autophagic flux were examined by Western blots of polyubiquitinated proteins and LC3-II conversion, respectively. AIMP2 expression alone increased the polyubiquitnated proteins which were further increased by α-synuclein coexpression (fig. S2G,H). On the other hand, LC3-II conversion increased with AIMP2 and/or α-synuclein expression, indicating either enhanced autophagosome formation or inhibition of downstream autophagic degradation pathway (fig. S2G,H).

To validate physical interaction between AIMP2 and α-synuclein, PFF was incubated either with GST-AIMP2-FLAG monomer or with GST-AIMP2-FLAG aggregate that was dot blotted on the membrane. This dot blot analysis revealed AIMP2 aggregate, but not AIMP2 monomer, has the ability to bind an α-synuclein monomer (Fig. 2C). Conversely, PFF can bind both the AIMP2 monomer and aggregate (Fig. 2C). This specific interaction between PFF and AIMP2 was confirmed by a GST pull-down experiment (Fig. 2D).

The intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence intensity of proteins with more than five tryptophan residues can be influenced by its local environments, reflecting the extent of the interaction with other binding partners (19, 20). Therefore, the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of a protein is used to obtain specific binding parameters of protein to ligands or to other proteins (19). A tryptophan fluorescence of AIMP2 with five tryptophans might be useful to understand its binding to α-synuclein without tryptophan. GST with the addition of α-synuclein failed to produce any demonstrable tryptophan fluorescence (fig. S2I). The addition of increasing amounts of α-synuclein or GST to monomeric GST-AIMP2-FLAG resulted in a linear graph of normalized tryptophan fluorescence (fig. S2J,K), suggesting a nonspecific interaction between AIMP2 and α-synuclein. However, aggregated GST-AIMP2-FLAG showed a hyperbolic and saturable tryptophan fluorescence graph upon increasing amounts of monomeric α-synuclein addition (Fig. 2E). The reaction between monomeric GST-AIMP2-FLAG and PFF also exhibited similar specific binding patterns (Fig. 2F). This interaction between AIMP2 and α-synuclein seems specific because both amyloid beta (Aβ) monomer and oligomer failed to bind both the AIMP2 monomer and aggregate (fig. S2L,M).

AIMP2 accelerates α-synuclein aggregation

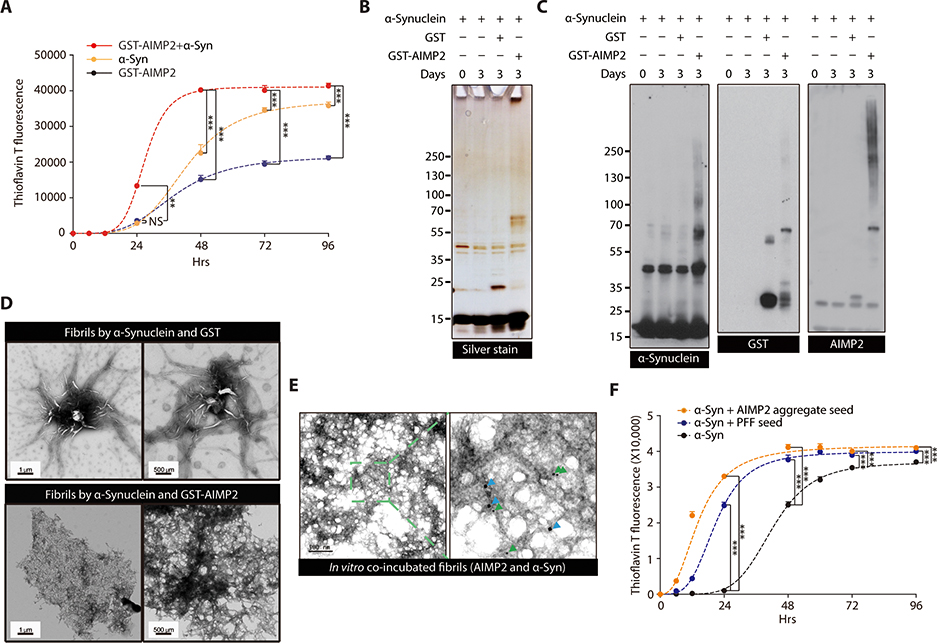

To obtain a mechanistic insight into the AIMP2 potentiation of α-synuclein pathologies, we performed a ThT-aided in vitro aggregation assay by incubating purified recombinant α-synuclein with or without GST-AIMP2-FLAG. As previously reported in many studies (21, 22), recombinant α-synuclein alone can self-aggregate into a ThT-reactive amyloid β sheet structure, reaching maximum ThT signal at around longer than 4 days of incubation (Fig. 3A). The addition of GST-AIMP2-FLAG into α-synuclein substantially accelerated the formation of amyloid aggregates based on the ThT fluorescence, reaching saturation as early as 2 days after incubation (Fig. 3A). Supporting the formation of fibril aggregates by AIMP2/α-synuclein co-incubation, there were silver stained protein species that were hard to be resolved in SDS-PAGE after 3 days of in vitro incubation (Fig. 3B). The immunoblot analysis confirmed the formation of SDS-resistant α-synuclein oligomer formation by co-incubating with AIMP2 (Fig. 3C). The immunoblot analysis also revealed concomitant aggregate formation of GST-AIMP2-FLAG (Fig. 3C). The ultrastructure of the co-aggregates formed by AIMP2 and α-synuclein is distinct from those formed by α-synuclein alone. Co-incubation of AIMP2 with α-synuclein resulted in a highly dense sheet-like conformation with few detectable amorphous oligomers (Fig. 3D) that is similar to EM structures of human LB (23). This aggregate structure is composed of both AIMP2 and α-synuclein since immunoGold electron microscopy (EM) revealed the localization of both proteins in this ultrastructure (Fig. 3E). Consistent with previous reports, aggregates by α-synuclein only are shapes with needle-like structure with many amorphous oligomer species (Fig. 3D). Next we sought to determine whether AIMP2 aggregation can serve as a template for α-synuclein aggregation. As previously reported (24), a small amount of PFF seeds accelerated α-synuclein aggregation as determined through ThT fluorescence (Fig. 3F). Similarly, the addition of preformed AIMP2 aggregates facilitated α-synuclein aggregation (Fig. 3F), indicating that the seed-template mechanism of AIMP2 aided α-synuclein aggregation.

Figure 3.

α-synuclein oligomer/fibril formation is enhanced by AIMP2 in vitro

(A) ThT fluorescence assay of in vitro aggregation for recombinant α-synuclein (50 uM) and/or GST-AIMP2-FLAG (50 uM) (n = 4 per group).

(B) Silver-stained gel image of in vitro incubation samples of α-synuclein (50 uM) and/or GST-AIMP2-FLAG (50 uM).

(C) Representative immunoblots of α-synuclein or AIMP2 for in vitro incubation samples with various combinations.

(D) Ultrastructure of protein aggregates prepared from α-synuclein incubation (7 d) with either GST or GST-AIMP2-FLAG monitored by a TEM.

(E) Localization of AIMP2 and α-synuclein in protein aggregate formed by in vitro coincubation of recombinant AIMP2 and α-synuclein determined by immuno-Gold EM using 10 nm (green arrow) or 20 nm (blue arrow) nanoGold particles conjugated to anti-AIMP2 and anti-α-synuclein antibodies, respectively.

(F) ThT fluorescence assay of in vitro aggregation for recombinant α-synuclein (50 uM) alone or with small amounts of PFF (2.5 uM) or AIMP2 preformed aggregate (2.5 uM) (n = 3 per group).

Quantified data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA test with Tukey post-hoc analysis, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; NS: not significant.

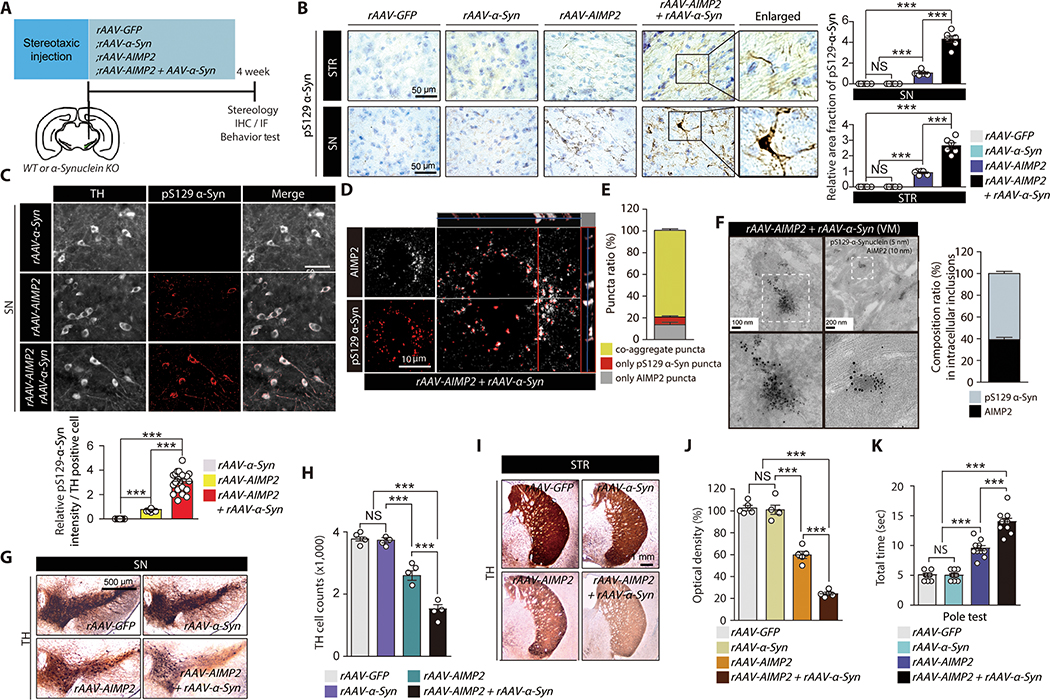

AIMP2 accelerates Lewy-like inclusion formation and dopaminergic toxicity in vivo

We investigated a pathological interaction of AIMP2 and α-synuclein in mouse brains with recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) injection (Fig. 4A). Intranigral rAAV injection transduced dopamine neurons with corresponding expression of GFP, α-synuclein, and AIMP2 by each rAAV virus (fig. S3A,B). The neuropathological assessment revealed nigral injection of rAAV-AIMP2 led to the formation of serine 129 phosphorylated (pS129) α-synuclein-positive aggregates in both the striatum and substantia nigra (SN) (Fig. 4B). These pS129 α-synuclein aggregates were increased by α-synuclein and AIMP2 coexpression (Fig. 4B). pS129 α-synuclein aggregates were colocalized in the TH-positive dopamine neurons (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the immunofluorescence and confocal double staining demonstrated an approximate 80% of the aggregates were double positive for AIMP2 and pS129-α-synuclein (Fig. 4D,E and fig. S3C). Small portions of the puncta were single positive for either pS129-α-synuclein or AIMP2 (Fig. 4D, E). An ultrastructure analysis by immunoGold EM demonstrated protein inclusions that were positive for both AIMP2 and pS129-α-synuclein in the SN of the mouse nigrally injected with rAAV-AIMP2 and rAAV-α-synuclein (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4. Co-expression and interaction of AIMP2 and α-synuclein in vivo enhanced α-synuclein aggregation and dopaminergic cell loss.

(A) Schematics of in vivo rAAV nigral injection to 2 month old C57BL/6 or α-synuclein KO mice. Experimental schedules for Western blot (WB), immunohistochemistry (IHC), TH stereology, and behavior test are indicated.

(B) Neuropathological assessment (Nissl counter stain) of phosphorylated α-synuclein in nigral and striatal sections from the indicated experimental mouse groups. Quantification of pS129-α-Syn immunohistochemistry (n = 6 slides from 3 mice per group, right panel).

(C) Immunofluorescence images showing pS129-α-synuclein and TH (pseudo-colored for original green fluorescence) expression in SN of mouse brains after intranigral injection of rAAV-α-synuclein, rAAV-AIMP2 or both. Quantification of pS129-α-Syn immunofluorescence (n = 23 cells from 3 mice per group, bottom panel).

(D) Confocal analysis of co-localization and aggregation of phosphorylated α-synuclein and AIMP2 (pseudo-colored for original green fluorescence).

(E) % ratio of aggregates with different composition of AIMP2 or/and phosphorylated α-synuclein (n = 66 cells from 3 mice).

(F) Ultrastructure of inclusion and co-labelling of AIMP2 and pS129-α-synuclein by nanogold particles for VM tissues from mice co-injected with rAAV-AIMP2 and rAAV-α-synuclein. 10 nm and 5 nm nanogold particles were used to detect anti-AIMP2 and anti-pS129-α-synuclein antibodies, respectively. Composition ratio of AIMP2 and pS129-α-Syn in inclusion structures (n = 41 inclusions from 3 mice, right panel).

(G) TH immunohistochemistry of SN sections from the experimental mouse groups.

(H) Stereological counting of dopamine neurons in the SN pars compacta of mouse groups in panel G (n = 4 mice per group).

(I) TH immunohistochemistry of striatum (STR) sections from the experimental mouse groups.

(J) Quantification of striatal TH fiber density for panel I determined by optical density measurement (n = 4 mice per group)

(K) Pole test for mouse groups with nigral injection of the indicated rAAV viruses (n = 11 mice per group).

Quantified data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA test with Tukey post-hoc analysis, ***p < 0.001; NS: not significant.

The dopamine neuron viability was evaluated in these virally-induced mouse groups. AIMP2 expression alone resulted in an approximate 30% degeneration of TH positive dopamine neurons in the SN pars compacta (Fig. 4G,H). This degeneration was further increased by the coexpression of α-synuclein (Fig. 4G,H). The expression of either GFP or α-synuclein alone had no effect on the dopamine neuron viability (Fig. 4G,H). There are correlating alterations of dopaminergic nerve terminal densities in the striatum from each of the virally-induced mouse groups (Fig. 4I,J). Each virally induced mouse group was characterized with several behavior tests. An open field test showed a similar extent of reduction in exploratory distance for both rAAV-AIMP2 and rAAV-AIMP2/α-synuclein groups as compared to rAAV-GFP and rAAV-α-synuclein groups (fig. S3D,E). Both rAAV-AIMP2 and rAAV-AIMP2/α-synuclein injection groups exhibited anxiety-related behavior determined through a delayed first entrance to the center zone and a tendency to explore less in the center zone (fig. S3F,G). The latency to first enter the center zone was delayed in mice coexpressing both AIMP2 and α-synuclein (fig. S3F). Virally induced ipsilateral AIMP2 expression in mouse brain produced dopamine specific behavior deficits in pole test (Fig. 4K). The coexpression of AIMP2 and α-synuclein further enhanced this motor deficit (Fig. 4K). Moreover, motor coordination and hindlimb extension reflex were impaired for mice coexpressing both AIMP2 and α-synuclein in the SN (fig. S3H–J). AIMP2 expression alone was sufficient to produce lesser extents of motor coordination deficits in mice (fig. S3H).

Previously, we developed tetracycline-regulatable AIMP2 transgenic (Tg) mice expressing AIMP2 in pan-neuronal population by CamKIIα-tTA driver (12). In this PD mouse model, there is an age-dependent and progressive dopaminergic loss and behavioral deficits (12). Whole brains from young and adult transgenic mice and littermate controls were fractionated into Triton X-soluble and insoluble fractionations to examine the distribution of AIMP2 and α-synuclein. At a young age, there was no detectable expression of AIMP2, α-synuclein, and filament α-synuclein in the insoluble fractions (fig. S4A). The accumulated AIMP2 was mostly found in the insoluble fraction from old AIMP2 transgenic brains. However, soluble AIMP2 was present at almost equal amounts in both Tg and littermate control (fig. S4B). There was a concomitant increase of α-synuclein in the insoluble fraction with filament conformation α-synuclein in both insoluble and soluble fractions of Tg mouse brains (fig. S4B). The high molecular-weight filament α-synuclein was exclusively present in the insoluble fractions of old AIMP2 Tg brains (fig. S4B). The formation of age-dependent Lewy-like inclusion stimulated by AIMP2 could be mediated by endogenous α-synuclein since virally induced AIMP2 expression in the VM of α-synuclein knockout background failed to generate any Lewy-like inclusion (fig. S4C,D).

We also examined conditional parkin knockout mouse brains in which progressive dopaminergic neurodegeneration has been reported (25). The conditional adult deletion of parkin was induced by nigral injection of rAAV-CRE to homozygous parkin floxed mice (parkin fl/fl). With successful ablation of parkin in the VM, there was an increase and redistribution of AIMP2 into the insoluble fraction at 2-month post parkin deletion (fig. S5A,B). The high-molecular-weight α-synuclein with filament conformation markedly increased in the insoluble fraction of adult parkin knockout brains, correlating with AIMP2 accumulation (fig. S5A,B,C).

AIMP2 is required for PFF- induced α-synuclein pathology

AIMP2 regulation and its role in α-synuclein aggregation was investigated in the recently introduced PFF model of PD (26, 27). In vitro differentiated dopaminergic neurons from mouse neural precursor cell were treated with PFF. PFF treatment induced not only marked production of pS129-α-synuclein aggregates, but also the accumulation of endogenous AIMP2 and its aggregation (fig. S6A,B). To determine the pathological role of AIMP2, cultured dopamine neurons were transduced with rAAV-shAIMP2 (coexpressing reporter RFP) or rAAV-shControl (scrambled shRNA coexpressing reporter GFP). TH-positive dopamine neurons were transduced with these rAAV virus as monitored by reporter fluorescence expression (fig. S6C). rAAV-AIMP2 infection of dopamine neurons led to a 50% reduction of endogenous AIMP2 without cellular toxicity (fig. S6D,E). The resupplementation of AIMP2 by rAAV-AIMP2 coinfection was confirmed to be used to address the potential off-target effect of rAAV-shAIMP2 (fig. S6D,E). AIMP2 knockdown by rAAV-shAIMP2 infection reduced the formation of pS129-α-synuclein aggregates by PFF treatment (fig. S6F,G). The recovery of α-synuclein aggregation by rAAV-AIMP2 together with rAAV-shAIMP2 indicated AIMP2 reduction by shRNA is responsible for rAAV-shAIMP2-mediated suppression of PFF-induced α-synuclein aggregation.

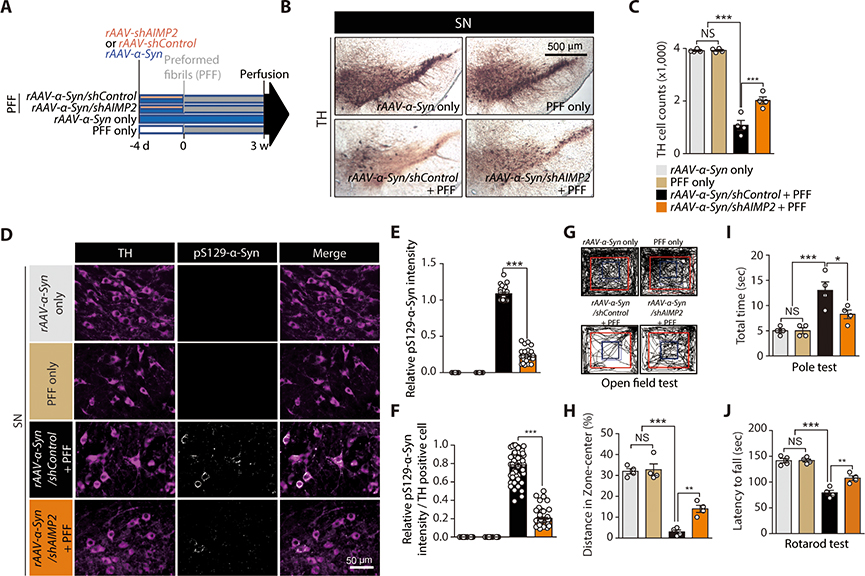

Next we sought to investigate AIMP2 function in an in vivo α-synucleinopathy mouse model. We employed the combinatorial model of PFF and rAAV-α-synuclein injection that develops α-synuclein pathology and dopamine neurodegeneration at around 3 weeks of incubation (28). Following the reported protocol (28) with some modifications, 2 month old C57/BL6 mice were co-injected with rAAV virus and PFF as follows: rAAV-α-synuclein only; PFF only; rAAV-α-synuclein/shControl+PFF; rAAV-α-synuclein/shAIMP2+PFF (Fig. 5). The rAAV-shAIMP2 titer that resulted in about 50% reduction of endogenous AIMP2 was used to prevent unwanted toxicity (fig. S6H,I). Consistent with the previous report (28), the combination of rAAV-α-synuclein injection followed by PFF led to more than 70% loss of dopamine neurons in SN pars compacta (Fig. 5B,C). This dopaminergic neuron loss was partially inhibited by AIMP2 knockdown via rAAV-shAIMP2 (Fig. 5B,C). Moreover, formation of pS129-α-synuclein aggregates in the combinatorial model was markedly diminished by the shRNA-mediated knockdown of AIMP2 (Fig. 5D–F). The anxiety phenotype induced in the combinatorial α-synucleinopathy model was also reduced in the knockdown background of AIMP2 by rAAV-shAIMP2.The bradykinesia induced by combinatorial expression of α-synuclein and PFF was partially restored by AIMP2 knockdown (Fig. 5J).

Figure 5. AIMP2 is required for PFF-induced α-synuclein aggregation and toxicity in vivo.

(A) Schematics of in vivo PFF and AAV viruses (expressing AIMP2, α-synuclein, shAIMP2, or shControl) injections to 2 month old C57/BL6 mice. Experimental schedules for virus or PFF injections and perfusion are indicated

(B) TH immunohistochemistry of SN sections from the indicated mouse groups.

(C) Stereological counting of dopamine neurons in the SN pars compacta of the indicated experimental mouse groups (n = 4 mice per group).

(D) Immunofluorescence images showing pS129-α-synuclein and TH expression in the SN of each experimental group. Note, rAAV-shControl and rAAV-shAIMP2 co-express reporter fluorescence GFP and RFP, respectively. pS129-α-synuclein signal is pseudo-colored in white in this image.

(E) Quantification of relative pS129-α-synuclein signal intensities in the VM from the indicated experimental groups (n = 20~29 cells from 4 mice per group).

(F) Quantification of relative pS129-α-synuclein signal intensities in TH-positive dopaminergic neurons of the VM from the indicated experimental groups (n = 60 dopamine cells from 4 mice per group).

(G) Representative exploration paths of mice from each group in the open field test.

(H) Assessment of anxiety in each experimental mouse group determined by % of exploration distance in the center zone (n = 4 per group).

(I) Assessment of bradykinesia in each experimental mouse group monitored by measuring the time taken to descend the vertical pole in pole test (n = 4 mice per group).

(J) Motor coordination of each experimental mouse group determined by latency to fall in accelerating rotarod test (n = 4 mice per group).

Quantified data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA test with Tukey post-hoc analysis, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; NS: not significant.

AIMP2 is required for α-synuclein aggregation under pathological condition

In PD, AIMP2 might be accumulated due to dysfunction of parkin or VPS35 or still unknown mechanisms. Such accumulation of AIMP2 can induce PD-related pathological changes, especially dopaminergic neuron loss (11, 12). Besides, AIMP2 interaction profile is affected by ionizing or oxidative stresses through dissociation of AIMP2 from the ARS complex (12, 14). In this context, cellular stresses leading to α-synuclein aggregation could affect endogenous AIMP2 solubility. As such α-synuclein-expressing SH-SY5Y cells were challenged with 6-hydroxy dopamine (6-OHDA), which is known to precipitate α-synuclein aggregation (29, 30). These cells were divided into Triton X-soluble and insoluble fractions to show redistribution of both AIMP2 and α-synuclein to insoluble fraction (fig. S7A). α-synuclein filament alteration was observed in the insoluble fraction upon 6-OHDA treatment (fig. S7A,B). Endogenous AIMP2 was knocked down by transfecting α-synuclein-expressing SH-SY5Y cells with shRNA (fig. S7C) followed by 6-OHDA treatment. The 6-OHDA treatment increased thioflavin S-positive aggregates whereas AIMP2 shRNA transfection prevented the aggregates (fig. S7D).

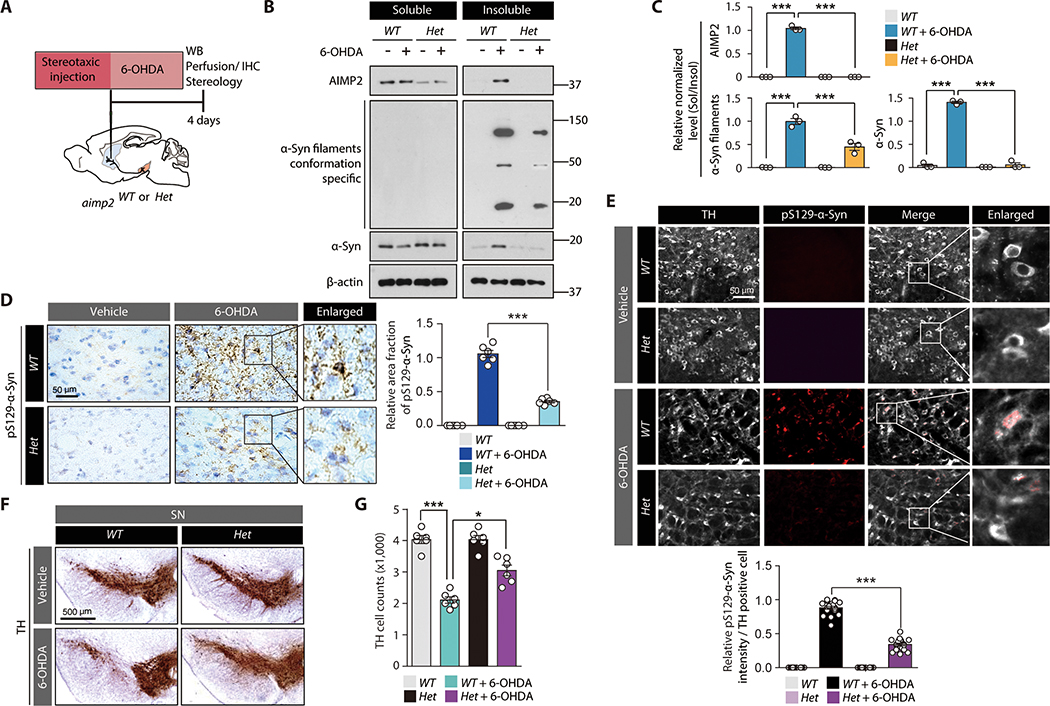

6-OHDA striatal injection model (Fig. 6A) was employed to model PD-related pathology in mice (31–33). Homozygous Aimp2 knockout (KO) mice are nonviable due to defective lung development (34). Therefore, heterozygous Aimp2 KO (Het) mice (fig. S8A) were used. This heterozygous KO mouse demonstrated more than 50% reduction of AIMP2 (fig. S8B). These mice are viable without obvious behavioral or morphological defects. AIMP2 ablation blocked redistribution of α-synuclein/AIMP2 and α-synuclein filament aggregation due to 6-OHDA (Fig. 6B,C). Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence images of SN sections revealed pS129-α-synuclein immunoreactivity in the tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) positive dopaminergic neurons of wild type (WT) mice under 6-OHDA intoxication (Fig. 6D,E). On the other hand, Aimp2 heterozygous KO background reduced the pS129-α-synuclein immunoreactivity (Fig. 6D,E). The alterations of α-synuclein pathologies correlated well with dopaminergic neuronal viability. In a 6-OHDA PD mouse model, an approximate 50% degeneration of dopaminergic neurons was induced in the SN compared to those in PBS-injected WT mice. Such degeneration was mostly prevented in aimp2 heterozygous KO mice (Fig. 6F,G).

Figure 6. AIMP2 is required for 6-OHDA-induced α-synuclein aggregation and toxicity in vivo.

(A) Schematics of in vivo 6-OHDA striatal injection to 2 month old heterozygous Aimp2 KO mice (Aimp2 Het) or wild type littermate control (WT). Experimental schedules for western blot (WB), IHC, and TH stereology are indicated.

(B) Western blots of AIMP2, α-synuclein, and filament conformation α-synuclein expression in Triton X-100 soluble and insoluble fractions of the VM from the indicated experimental mouse groups.

(C) Quantification of relative amounts of AIMP2, α-synuclein, and filament conformation α-synuclein expression in insoluble fractions normalized to those in soluble fractions from sample groups in panel B (n = 3 mice per group).

(D) Neuropathological assessment of phosphorylated α-synuclein-positive inclusions in mouse brains of each experimental group monitored by immunohistochemistry using pS129 α-synuclein antibody and Nissl counter staining. Quantification of pS129-α-Syn immunohistochemistry (n = 6 slides from 3 mice per group, right panel).

(E) Representative immunofluorescence images showing pS129-α-synuclein and TH (pseudo-colored for original green fluorescence) expression in the SN of each experimental mouse group. Quantification of pS129-α-Syn immunofluorescence in TH-positive cells (n = 20 cells from 3 mice per group, bottom panel).

(F) TH immunohistochemistry images of SN sections from the indicated experimental mouse groups.

(G) Stereological counting of dopamine neurons in the SN pars compacta of each experimental mouse group (n = 5~6 mice per group).

Quantified data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA test with Tukey post-hoc analysis, *p < 0.05, and ***p < 0.001.

AIMP2 in LB inclusion in brains from patients with PD

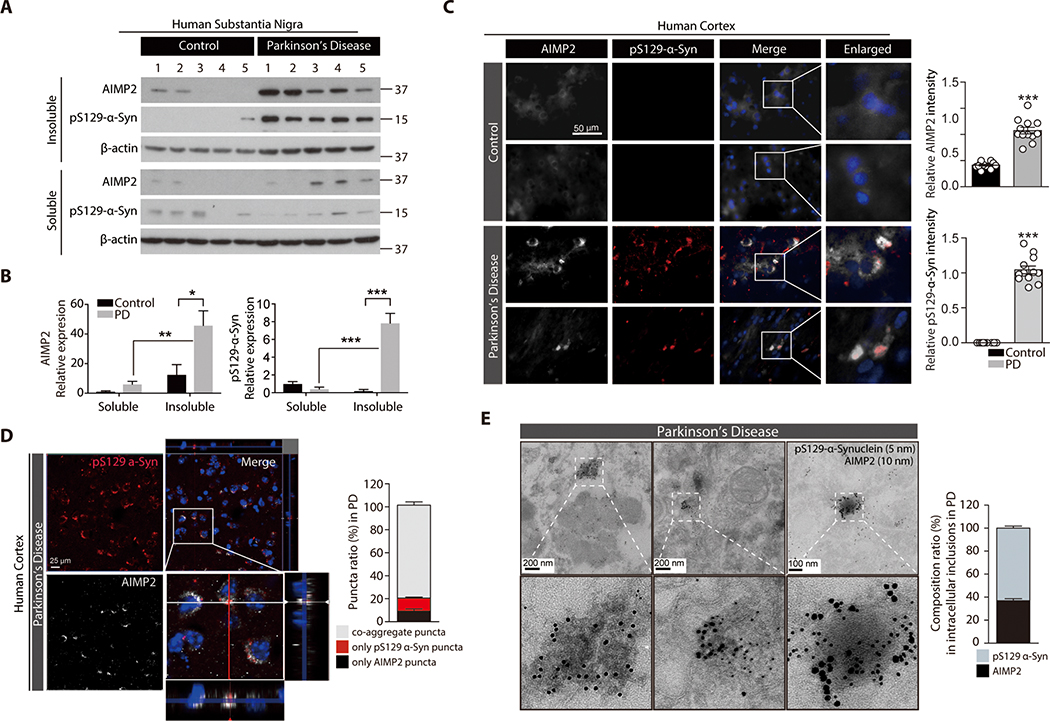

Postmortem SN brains from patients with PD and age-matched controls (table S1) were subjected to fractionation into NP-40 soluble and insoluble compartments. Both AIMP2 and phosphorylated α-synuclein were redistributed into the insoluble fraction in SN brains of patients with PD, but not in control brains (Fig. 7A,B). The cellular distribution of AIMP2 and phosphorylated α-synuclein in the postmortem temporal lobe of patients with PD with confirmed Lewy pathologies (table S2) was further evaluated. Postmortem PD brains concomitantly expressed elevated expression of AIMP2 aggregates (Fig. 7C). The AIMP2 signal overlapped with pS129 α-synuclein immunoreactivity (Fig. 7C), and their colocalization was further confirmed by confocal z-stack imaging (Fig. 7D). Ultrastructure analysis by immunoGold EM revealed co-presence of both AIMP2 and pS129 α-synuclein signals in electron-dense inclusion structures from postmortem brains from patients with PD (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7. Insoluble co-aggregation of α-synuclein with AIMP2 in human PD brains.

(A) Distribution of AIMP2 and phosphorylated α-synuclein (pS129-α-syn) in NP-40 soluble and insoluble fractions prepared from postmortem human brains of patients with PD and age matched controls based on Western blot analysis.

(B) Relative distribution of AIMP2 and phosphorylated α-synuclein (pS129-α-syn) into each fractions normalized to β-actin (n = 5 per group).

(C) Co-aggregation of AIMP2 (pseudo-colored for original green fluorescence) into LB inclusions in temporal lobe from postmortem PD brains monitored by immunofluorescence. Quantification of AIMP2 and pS129-α-Syn immunofluorescence (n = 12 slides from 4 Con and 12 slides from 4 PD, right panel).

(D) Confocal microscopic and Z-stack images showing colocalization of AIMP2 (pseudo-colored for original green fluorescence) in the pS129 α-synuclein-positive LB in PD human brain samples. % puncta ratio composed of AIMP2 or/and phosphorylated α-synuclein (n = 21 cells from 4 PD, right panel)

(E) Ultrastructure of inclusion and colabeling of AIMP2 and pS129-α-synuclein by nanogold particles for postmortem human PD brain tissues determined by an immunoGold EM. 10 nm and 5 nm nanogold particles were used to detect anti-AIMP2 and anti-pS129-α-synuclein antibodies, respectively. Composition ratio of AIMP2 and pS129-α-Syn in inclusion structures (n = 26 inclusions from 4 PD, right panel).

Quantified data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA test with Tukey post-hoc analysis or unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The pathological link of AIMP2 to PD was initially identified as a toxic substrate of PD-linked E3 ubiquitin ligase parkin (11, 13). In addition, a recent report indicated that the lysosomal clearance of AIMP2 can be regulated by another PD linked gene, VPS35 (15). Although AIMP2 has been shown to be present in the Lewy bodies of postmortem brains from patients with PD (11, 13), the role of AIMP2 in the formation of LB inclusions or α-synuclein pathology has not been investigated. An in vitro aggregation assay revealed a strong potentiation of α-synuclein aggregation by co-incubating with AIMP2. This result suggests that defective parkin/VPS35 and AIMP2 accumulation in PD might play a causative role in α-synuclein aggregation. Moreover, since both AIMP2 and α-synuclein are present in whole brain regions (12) and we have shown the copresence of AIMP2 and α-synuclein aggregates in the temporal lobe of LB dementia patients brains, its role in α-synuclein pathologies could be extended to other α-synucleinopathies in addition to PD.

Since α-synuclein aggregation and protein aggregation-related neurodegenerative diseases can cause cellular dysfunction mainly due to the sequestration of metastable and functionally important proteins (35), targeting the AIMP2-α-synuclein cycles in aggregate formation might present a robust tool to screen chemical compounds with therapeutic potential for proteinopathies. For instance, the co-incubation strategy of AIMP2 and α-synuclein can shorten the incubation time for the ThT-aided high-throughput screening compared to relatively long incubation time required for amyloid aggregation by α-synuclein alone (26, 36). In addition, the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of AIMP2 could be used to study its specific interaction with other proteins with no tryptophan residues. This type of fluorescence assay does not require an incubation time as in the case for the ThT assay. As such, it is more appropriate for large-scale compound screening to identify the compound that can specifically interfere with the AIMP2 aggregate interaction with α-synuclein or AIMP2 interaction with PFF α-synuclein. However, this assay has some limitations since AIMP2 tryptophan fluorescence could be influenced by diverse indirect mechanisms rather than affecting AIMP2-α-synuclein interaction.

In this study, we found that 6-OHDA oxidative stress induced AIMP2 amyloid oligomerization, correlating with α-synuclein aggregation. It is currently unclear how AIMP2 dissociation from the ARS complex is initiated upon 6-OHDA stress and what modification might have altered the AIMP2 solubility in the cytoplasm or nucleus. It is interesting to note that there was a marked enhancement of PARP1-independent cytotoxicity when AIMP2 and α-synuclein were coexpressed with more protein aggregate formation. The identification of signaling pathways responsible for AIMP2 aggregation and interaction with α-synuclein during oxidative stress, and PD related pathologies might provide potential therapeutic targets to ameliorate the progression of α-synuclein pathology as well as cytotoxicity. Moreover, although there have been no reports regarding the clinical relevance of other noncatalytic elements of ARS complex such as AIMP1 and 3, it would be interesting to evaluate AIMP1 or AIMP3 dysregulation in PD pathologies since their noncanonical functions involve regulation of immune or aging pathways that also play roles in PD pathogenesis (37, 38).

It has long been thought that parkin and α-synuclein signaling pathways are independent of each other (39). Several studies using parkin knockout mice have failed to observe LB pathologies as well as dopaminergic neuronal death (40–42). Moreover, a few available autopsy studies in juvenile or early onset PD cases with homozygous parkin loss reported no LB pathologies, even with a quite robust loss of pigmented dopamine neurons in the midbrain (43–45). In this context, it can appear that the role of parkin substrate AIMP2 in α-synuclein aggregation might be inconsistent with those aforementioned clinical and in vivo mouse model studies. However, it should be noted that several studies have indeed reported LB pathologies in early-onset PD cases with parkin mutations (46–51). There are also reports suggesting the involvement of parkin inactivation in common sporadic PD with LB (10, 52, 53). Consistent with this notion, AIMP2 aggregates and insoluble redistribution correlated well with LB pathologies in brains from sporadic patients with PD in which parkin is presumably inactivated. Moreover, the role of parkin substrate ZNF746 has been noted in PFF-induced parkin inactivation and α-synuclein pathology (54), suggesting a pathological link between α-synuclein and parkin which was previously thought to be independent. As mentioned above, several conventional parkin null mice failed to produce meaningful PD-related pathologies including α-synuclein aggregation. A compensatory mechanism during development could have masked the manifestation of PD pathologies because adult parkin ablation in mice resulted in progressive dopaminergic neuron loss (25). Similarly, we demonstrated adult parkin deletion in mice could trigger α-synuclein aggregation with concomitant AIMP2 accumulation and redistribution to the insoluble compartment.

In clinical cases, it is still unclear how AIMP2 accumulation downstream of inactive parkin leads to various outcomes in terms of LB formation; we speculate that additional pathological molecular changes might to ultimately set in motion α-synuclein abnormal aggregation. Supporting this notion, transgenic mice expressing robust amounts of α-synuclein in brains take about 10 months to exhibit Lewy like inclusion (55). Even with AIMP2 expression in mouse brains, we only observed filament conformation of α-synuclein at 8 months of age. These in vivo studies indicate that aging or other disease processes might contribute together to α-synuclein aggregation probably by affecting protein quality control or additional signaling pathways regulating α-synuclein stability.

Despite pathological interaction between AIMP2 and α-synuclein, there are limitations in our study especially when practical translational application is considered. First, previous studies and ours showed varying accumulation of AIMP2 in postmortem PD brain samples (10–12, 52). Extensive analysis of the AIMP2 accumulation in a larger cohort of patients with PD would be necessary to ascertain pathological correlation between AIMP2 upregulation and α-synucleinopathy in PD. Second, our study lacks safety profiling of AIMP2 knockdown in vivo. Therapeutic approaches to reduce the AIMP2 expression could have a low therapeutic index given that each PD case has variable extent of AIMP2 accumulation and a too large reduction of endogenous AIMP2 can impair other biological processes. In this regard, compounds inhibiting AIMP2 aggregation could be more safe and effective in regulating AIMP2-α-synuclein coaggregation in PD. Last, pathological AIMP2 aggregation in mouse and human brains was mainly monitored by morphologies and signal intensities using conventional anti-AIMP2 antibody. More sensitive detection and estimation of AIMP2 aggregate prevalence in PD requires development of AIMP2 fibril conformation specific antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The study aimed to determine potential roles of AIMP2 aggregation in α-synuclein-related pathologies. Aggregation and interaction between recombinant AIMP2 and α-synuclein was explored by ThT fluorescence assay, CD analysis, GST pull-down, dot blot, tryptophan fluorescence assay, and EM imaging. Most experiments were performed in at least triplicate for statistical analysis. AIMP2-α-synuclein interaction was further examined in both SH-SY5Y cells and dopamine neurons with treatment of PD stresses including 6-OHDA and PFF, respectively. Immunofluorescence, Western blots, trypan blue exclusion assay were performed in at least triplicate for statistical analysis of α-synucleinopathy-related phenotypes. For the animal studies, we used two PD animal models of 6-OHDA injection or PFF/rAAV-α-synuclein coinjection. To determine the role of AIMP2 in vivo, aimp2 ablation by genetic heterozygous KO or virally induced knockdown model was applied in these PD mouse models. Power analysis was performed by using G*Power 3.1 software (56) to determine approximate sample sizes for TH stereological analysis. On the basis of mean difference from our preliminary experiments (30–50% mean difference) a total sample size of 20 mice (5 mice per group) was calculated to obtain statistical significance (effect size f = 1.06, α error probability = 0.05, number of groups = 4). For all animal experiments, mice groups were randomized, and the experimenters were blinded to the genotypes and treatment of mice. No animals were excluded from analysis.

Acquisition and handling of human postmortem brains

Postmortem SN brain from patients with PD and age-matched controls were powdered and fractionated into soluble and insoluble fraction by using lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail II and III (Sigma-Aldrich) and complete protease inhibitor mixture (Cell Signaling Technology) and ultracentrifugation (22,000g, 20 min). Protein lysates from each fraction were subjected to Western blot using the corresponding antibodies. Fixed postmortem human brain sections (temporal lobe) were kindly provided by the Brain and Body Donation Program (BBDP). Fixed brain sections were subjected to immunofluorescence experiments as described above. The demographic information of human samples is described in Table 1and 2

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). All data used to generate graphs was presented in data file S1. Normality of the data was tested with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Statistical significance was assessed either via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for two-group comparisons or ANOVA test with Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis for comparison of more than three groups. Assessments were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Fig.S8. Genotyping of Aimp2 KO mice.

Fig.S7. AIMP2 contributes to 6-OHDA-induced α-synuclein aggregation

Fig.S6. AIMP2 facilitates PFF-induced α-synuclein aggregation.

Fig.S5. AIMP2 redistribution and α-synuclein aggregation in virally induced adult parkin knockout mice.

Fig.S4. α-synuclein is required for AIMP2-stimulated Lewy-like inclusion formation

Fig.S3. Virally induced expression of α-synuclein and/or AIMP2 in vivo.

Fig.S2. Biological consequences of AIMP2-α-synuclein interaction

Fig.S1. Purification of recombinant AIMP2

Table S1. Detailed information for postmortem human brain tissues used in this study

Table S2. Detailed information for postmortem fixed temporal lobe (TL) sections from human PD brains used in this study (BBDP).

Data file S1. Raw data (Provided as separate Excel file)

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Ted M. Dawson, and Valina L. Dawson for sharing floxed parkin knockout mice.

Funding

This research was supported by grants (2017M3C7A1043848 to Y.L.) of National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, & Future Planning (MSIP), and also supported by the Korea Basic Science Institute under the R&D program (Project No. C030440 to Y.L. and H-S.K.) supervised by the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea. This work was also supported by grants from the NIH/NINDS NS38377 Morris K. Udall PD Research Center and NIH/NINDS NS107404 and NS098006 (to H.S.K.). We are also grateful to the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program of Sun City, Arizona for the provision of human biological materials. The Brain and Body Donation Program is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for PD and Related Disorders), the National Institute of Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001 to the Arizona PD Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Footnotes

Competing interests

S.H, and Y.L. hold a patent related to screening methods using AIMP2-α-synuclein interaction (10-1888785, Screening method of therapeutic agent for degenerative brain disease and kit for the same, South Korea domestic patent)

Data and materials availability

All data pertaining to this study are present within the main text and the Supplementary materials.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spillantini MG, Goedert M, The alpha-synucleinopathies: Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and multiple system atrophy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 920, 16–27 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lang AE, Lozano AM, Parkinson’s disease. Second of two parts. N Engl J Med 339, 1130–1143 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang AE, Lozano AM, Parkinson’s disease. First of two parts. N Engl J Med 339, 1044–1053 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norris EH, Giasson BI, Lee VM, Alpha-synuclein: normal function and role in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Top Dev Biol 60, 17–54 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brahmachari S, Ge P, Lee SH, Kim D, Karuppagounder SS, Kumar M, Mao X, Shin JH, Lee Y, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Ko HS, Activation of tyrosine kinase c-Abl contributes to alpha-synuclein-induced neurodegeneration. J Clin Invest 126, 2970–2988 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashimoto M, Takeda A, Hsu LJ, Takenouchi T, Masliah E, Role of cytochrome c as a stimulator of alpha-synuclein aggregation in Lewy body disease. J Biol Chem 274, 28849–28852 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahul-Mellier AL, Fauvet B, Gysbers A, Dikiy I, Oueslati A, Georgeon S, Lamontanara AJ, Bisquertt A, Eliezer D, Masliah E, Halliday G, Hantschel O, Lashuel HA, c-Abl phosphorylates alpha-synuclein and regulates its degradation: implication for alpha-synuclein clearance and contribution to the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 23, 2858–2879 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefanis L, alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2, a009399 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shults CW, Lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 1661–1668 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko HS, Lee Y, Shin JH, Karuppagounder SS, Gadad BS, Koleske AJ, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Phosphorylation by the c-Abl protein tyrosine kinase inhibits parkin’s ubiquitination and protective function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 16691–16696 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko HS, von Coelln R, Sriram SR, Kim SW, Chung KK, Pletnikova O, Troncoso J, Johnson B, Saffary R, Goh EL, Song H, Park BJ, Kim MJ, Kim S, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Accumulation of the authentic parkin substrate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase cofactor, p38/JTV-1, leads to catecholaminergic cell death. J Neurosci 25, 7968–7978 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee Y, Karuppagounder SS, Shin JH, Lee YI, Ko HS, Swing D, Jiang H, Kang SU, Lee BD, Kang HC, Kim D, Tessarollo L, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Parthanatos mediates AIMP2-activated age-dependent dopaminergic neuronal loss. Nat Neurosci 16, 1392–1400 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corti O, Hampe C, Koutnikova H, Darios F, Jacquier S, Prigent A, Robinson JC, Pradier L, Ruberg M, Mirande M, Hirsch E, Rooney T, Fournier A, Brice A, The p38 subunit of the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complex is a Parkin substrate: linking protein biosynthesis and neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet 12, 1427–1437 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han JM, Park BJ, Park SG, Oh YS, Choi SJ, Lee SW, Hwang SK, Chang SH, Cho MH, Kim S, AIMP2/p38, the scaffold for the multi-tRNA synthetase complex, responds to genotoxic stresses via p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 11206–11211 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yun SP, Kim H, Ham S, Kwon SH, Lee GH, Shin JH, Lee SH, Ko HS, Lee Y, VPS35 regulates parkin substrate AIMP2 toxicity by facilitating lysosomal clearance of AIMP2. Cell Death Dis 8, e2741 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.David KK, Andrabi SA, Dawson TM, Dawson VL, Parthanatos, a messenger of death. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 14, 1116–1128 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong ES, Tan JM, Soong WE, Hussein K, Nukina N, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Cuervo AM, Lim KL, Autophagy-mediated clearance of aggresomes is not a universal phenomenon. Hum Mol Genet 17, 2570–2582 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olah J, Vincze O, Virok D, Simon D, Bozso Z, Tokesi N, Horvath I, Hlavanda E, Kovacs J, Magyar A, Szucs M, Orosz F, Penke B, Ovadi J, Interactions of pathological hallmark proteins: tubulin polymerization promoting protein/p25, beta-amyloid, and alpha-synuclein. J Biol Chem 286, 34088–34100 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Maio R, Barrett PJ, Hoffman EK, Barrett CW, Zharikov A, Borah A, Hu X, McCoy J, Chu CT, Burton EA, Hastings TG, Greenamyre JT, alpha-Synuclein binds to TOM20 and inhibits mitochondrial protein import in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Transl Med 8, 342ra378 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vivian JT, Callis PR, Mechanisms of tryptophan fluorescence shifts in proteins. Biophys J 80, 2093–2109 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez JA, Ivanova MI, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Reyes FE, Shi D, Sangwan S, Guenther EL, Johnson LM, Zhang M, Jiang L, Arbing MA, Nannenga BL, Hattne J, Whitelegge J, Brewster AS, Messerschmidt M, Boutet S, Sauter NK, Gonen T, Eisenberg DS, Structure of the toxic core of alpha-synuclein from invisible crystals. Nature 525, 486–490 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uversky VN, Eliezer D, Biophysics of Parkinson’s disease: structure and aggregation of alpha-synuclein. Curr Protein Pept Sci 10, 483–499 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olanow CW, Perl DP, DeMartino GN, McNaught KS, Lewy-body formation is an aggresome-related process: a hypothesis. Lancet Neurol 3, 496–503 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kakuda K, Ikenaka K, Araki K, So M, Aguirre C, Kajiyama Y, Konaka K, Noi K, Baba K, Tsuda H, Nagano S, Ohmichi T, Nagai Y, Tokuda T, El-Agnaf OMA, Ogi H, Goto Y, Mochizuki H, Ultrasonication-based rapid amplification of alpha-synuclein aggregates in cerebrospinal fluid. Sci Rep 9, 6001 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin JH, Ko HS, Kang H, Lee Y, Lee YI, Pletinkova O, Troconso JC, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, PARIS (ZNF746) repression of PGC-1alpha contributes to neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Cell 144, 689–702 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volpicelli-Daley LA, Luk KC, Lee VM, Addition of exogenous alpha-synuclein preformed fibrils to primary neuronal cultures to seed recruitment of endogenous alpha-synuclein to Lewy body and Lewy neurite-like aggregates. Nat Protoc 9, 2135–2146 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luk KC, Kehm V, Carroll J, Zhang B, O’Brien P, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Pathological alpha-synuclein transmission initiates Parkinson-like neurodegeneration in nontransgenic mice. Science 338, 949–953 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thakur P, Breger LS, Lundblad M, Wan OW, Mattsson B, Luk KC, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ, Bjorklund A, Modeling Parkinson’s disease pathology by combination of fibril seeds and alpha-synuclein overexpression in the rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, E8284–E8293 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alves da Costa C, Dunys J, Brau F, Wilk S, Cappai R, Checler F, 6-Hydroxydopamine but not 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium abolishes alpha-synuclein anti-apoptotic phenotype by inhibiting its proteasomal degradation and by promoting its aggregation. J Biol Chem 281, 9824–9831 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganapathy K, Datta I, Sowmithra S, Joshi P, Bhonde R, Influence of 6-Hydroxydopamine Toxicity on alpha-Synuclein Phosphorylation, Resting Vesicle Expression, and Vesicular Dopamine Release. J Cell Biochem 117, 2719–2736 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvarez-Fischer D, Henze C, Strenzke C, Westrich J, Ferger B, Hoglinger GU, Oertel WH, Hartmann A, Characterization of the striatal 6-OHDA model of Parkinson’s disease in wild type and alpha-synuclein-deleted mice. Exp Neurol 210, 182–193 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coppola-Segovia V, Cavarsan C, Maia FG, Ferraz AC, Nakao LS, Lima MM, Zanata SM, ER Stress Induced by Tunicamycin Triggers alpha-Synuclein Oligomerization, Dopaminergic Neurons Death and Locomotor Impairment: a New Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Mol Neurobiol, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.da Conceicao FS, Ngo-Abdalla S, Houzel JC, Rehen SK, Murine model for Parkinson’s disease: from 6-OH dopamine lesion to behavioral test. J Vis Exp, (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim MJ, Park BJ, Kang YS, Kim HJ, Park JH, Kang JW, Lee SW, Han JM, Lee HW, Kim S, Downregulation of FUSE-binding protein and c-myc by tRNA synthetase cofactor p38 is required for lung cell differentiation. Nat Genet 34, 330–336 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olzscha H, Schermann SM, Woerner AC, Pinkert S, Hecht MH, Tartaglia GG, Vendruscolo M, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU, Vabulas RM, Amyloid-like aggregates sequester numerous metastable proteins with essential cellular functions. Cell 144, 67–78 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim C, Lv G, Lee JS, Jung BC, Masuda-Suzukake M, Hong CS, Valera E, Lee HJ, Paik SR, Hasegawa M, Masliah E, Eliezer D, Lee SJ, Exposure to bacterial endotoxin generates a distinct strain of alpha-synuclein fibril. Sci Rep 6, 30891 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee SW, Kim G, Kim S, Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase-interacting multi-functional protein 1/p43: an emerging therapeutic protein working at systems level. Expert Opin Drug Discov 3, 945–957 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oh YS, Kim DG, Kim G, Choi EC, Kennedy BK, Suh Y, Park BJ, Kim S, Downregulation of lamin A by tumor suppressor AIMP3/p18 leads to a progeroid phenotype in mice. Aging Cell 9, 810–822 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dawson TM, Ko HS, Dawson VL, Genetic animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 66, 646–661 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Von Coelln R, Thomas B, Savitt JM, Lim KL, Sasaki M, Hess EJ, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Loss of locus coeruleus neurons and reduced startle in parkin null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 10744–10749 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez FA, Palmiter RD, Parkin-deficient mice are not a robust model of parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 2174–2179 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Coelln R, Thomas B, Andrabi SA, Lim KL, Savitt JM, Saffary R, Stirling W, Bruno K, Hess EJ, Lee MK, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Inclusion body formation and neurodegeneration are parkin independent in a mouse model of alpha-synucleinopathy. J Neurosci 26, 3685–3696 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi H, Ohama E, Suzuki S, Horikawa Y, Ishikawa A, Morita T, Tsuji S, Ikuta F, Familial juvenile parkinsonism: clinical and pathologic study in a family. Neurology 44, 437–441 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajput AH, Pathologic and biochemical studies of juvenile parkinsonism linked to chromosome 6q. Neurology 53, 1375 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimura H, Hattori N, Kubo S, Yoshikawa M, Kitada T, Matsumine H, Asakawa S, Minoshima S, Yamamura Y, Shimizu N, Mizuno Y, Immunohistochemical and subcellular localization of Parkin protein: absence of protein in autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism patients. Ann Neurol 45, 668–672 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharp ME, Marder KS, Cote L, Clark LN, Nichols WC, Vonsattel JP, Alcalay RN, Parkinson’s disease with Lewy bodies associated with a heterozygous PARKIN dosage mutation. Mov Disord 29, 566–568 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruffmann C, Zini M, Goldwurm S, Bramerio M, Spinello S, Rusconi D, Gambacorta M, Tagliavini F, Pezzoli G, Giaccone G, Lewy body pathology and typical Parkinson disease in a patient with a heterozygous (R275W) mutation in the Parkin gene (PARK2). Acta Neuropathol 123, 901–903 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyakawa S, Ogino M, Funabe S, Uchino A, Shimo Y, Hattori N, Ichinoe M, Mikami T, Saegusa M, Nishiyama K, Mori H, Mizuno Y, Murayama S, Mochizuki H, Lewy body pathology in a patient with a homozygous parkin deletion. Mov Disord 28, 388–391 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pramstaller PP, Schlossmacher MG, Jacques TS, Scaravilli F, Eskelson C, Pepivani I, Hedrich K, Adel S, Gonzales-McNeal M, Hilker R, Kramer PL, Klein C, Lewy body Parkinson’s disease in a large pedigree with 77 Parkin mutation carriers. Ann Neurol 58, 411–422 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sasaki S, Shirata A, Yamane K, Iwata M, Parkin-positive autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinsonism with alpha-synuclein-positive inclusions. Neurology 63, 678–682 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farrer M, Chan P, Chen R, Tan L, Lincoln S, Hernandez D, Forno L, Gwinn-Hardy K, Petrucelli L, Hussey J, Singleton A, Tanner C, Hardy J, Langston JW, Lewy bodies and parkinsonism in families with parkin mutations. Ann Neurol 50, 293–300 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Imam SZ, Zhou Q, Yamamoto A, Valente AJ, Ali SF, Bains M, Roberts JL, Kahle PJ, Clark RA, Li S, Novel regulation of parkin function through c-Abl-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation: implications for Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci 31, 157–163 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dawson TM, Dawson VL, Parkin plays a role in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegener Dis 13, 69–71 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brahmachari S, Lee S, Kim S, Yuan C, Karuppagounder SS, Ge P, Shi R, Kim EJ, Liu A, Kim D, Quintin S, Jiang H, Kumar M, Yun SP, Kam TI, Mao X, Lee Y, Swing DA, Tessarollo L, Ko HS, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Parkin interacting substrate zinc finger protein 746 is a pathological mediator in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 142, 2380–2401 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee MK, Stirling W, Xu Y, Xu X, Qui D, Mandir AS, Dawson TM, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL, Human alpha-synuclein-harboring familial Parkinson’s disease-linked Ala-53 --> Thr mutation causes neurodegenerative disease with alpha-synuclein aggregation in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 8968–8973 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A, G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39, 175–191 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waxman EA, Giasson BI, Induction of intracellular tau aggregation is promoted by alpha-synuclein seeds and provides novel insights into the hyperphosphorylation of tau. J Neurosci 31, 7604–7618 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dar MA, Wahiduzzaman, Haque MA, Islam A, Hassan MI, Ahmad F, Characterisation of molten globule-like state of sheep serum albumin at physiological pH. Int J Biol Macromol 89, 605–613 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pachahara SK, Chaudhary N, Subbalakshmi C, Nagaraj R, Hexafluoroisopropanol induces self-assembly of beta-amyloid peptides into highly ordered nanostructures. J Pept Sci 18, 233–241 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rhee YH, Kim TH, Jo AY, Chang MY, Park CH, Kim SM, Song JJ, Oh SM, Yi SH, Kim HH, You BH, Nam JW, Lee SH, LIN28A enhances the therapeutic potential of cultured neural stem cells in a Parkinson’s disease model. Brain 139, 2722–2739 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig.S8. Genotyping of Aimp2 KO mice.

Fig.S7. AIMP2 contributes to 6-OHDA-induced α-synuclein aggregation

Fig.S6. AIMP2 facilitates PFF-induced α-synuclein aggregation.

Fig.S5. AIMP2 redistribution and α-synuclein aggregation in virally induced adult parkin knockout mice.

Fig.S4. α-synuclein is required for AIMP2-stimulated Lewy-like inclusion formation

Fig.S3. Virally induced expression of α-synuclein and/or AIMP2 in vivo.

Fig.S2. Biological consequences of AIMP2-α-synuclein interaction

Fig.S1. Purification of recombinant AIMP2

Table S1. Detailed information for postmortem human brain tissues used in this study

Table S2. Detailed information for postmortem fixed temporal lobe (TL) sections from human PD brains used in this study (BBDP).

Data file S1. Raw data (Provided as separate Excel file)