Abstract

Morbidity and mortality associated with heart disease is a growing threat to the global population, and novel therapies are needed. Mavacamten (formerly called MYK-461) is a small molecule that binds to cardiac myosin and inhibits myosin ATPase. Mavacamten is currently in clinical trials for the treatment of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), and it may provide benefits for treating other forms of heart disease. We investigated the effect of mavacamten on cardiac muscle contraction in two transgenic mouse lines expressing the human isoform of cardiac myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) in their hearts. Control mice expressed wild-type RLC (WT-RLC), and HCM mice expressed the N47K RLC mutation. In the absence of mavacamten, skinned papillary muscle strips from WT-RLC mice produced greater isometric force than strips from N47K mice. Adding 0.3 µM mavacamten decreased maximal isometric force and reduced Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction for both genotypes, but this reduction in pCa50 was nearly twice as large for WT-RLC versus N47K. We also used stochastic length-perturbation analysis to characterize cross-bridge kinetics. The cross-bridge detachment rate was measured as a function of [MgATP] to determine the effect of mavacamten on myosin nucleotide handling rates. Mavacamten increased the MgADP release and MgATP binding rates for both genotypes, thereby contributing to faster cross-bridge detachment, which could speed up myocardial relaxation during diastole. Our data suggest that mavacamten reduces isometric tension and Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction via decreased strong cross-bridge binding. Mavacamten may become a useful therapy for patients with heart disease, including some forms of HCM.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Mavacamten is a pharmaceutical that binds to myosin, and it is under investigation as a therapy for some forms of heart disease. We show that mavacamten reduces isometric tension and Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction in skinned myocardial strips from a mouse model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy that expresses the N47K mutation in cardiac myosin regulatory light chain. Mavacamten reduces contractility by decreasing strong cross-bridge binding, partially due to faster cross-bridge nucleotide handling rates that speed up myosin detachment.

Keywords: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, mavacamten, myosin cross-bridge kinetics, regulatory light chain

INTRODUCTION

Global mortality from cardiovascular disease has continued to rise despite concerted efforts to develop better treatments. Cardiovascular diseases currently rank as the number one cause of mortality in the United States and globally (1, 2), encompassing a range of dysfunctional conditions from the blood vessels to the heart (3). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetically inherited disease that primarily affects sarcomeric proteins of the heart, which is estimated to affect ∼1 in 200 people (4). Although genetic penetrance varies, HCM mutations have been linked to elevated myocardial activation at low intracellular [Ca2+] during diastole, which can impair cardiac relaxation and precede the development of hypertrophy (4, 5). Systolic contraction is often preserved (or enhanced), and as the disease progresses, the walls of the cardiac ventricle typically thicken, resulting in HCM (6, 7). To date, ∼1,400 mutations in genes encoding for 11 sarcomeric proteins have been linked to HCM (4, 5, 8).

One potential new therapy under investigation to treat some forms of HCM is a pharmaceutical compound called mavacamten (formerly called MYK-461, from MyoKardia). Mavacamten binds to myosin and inhibits myosin ATPase (9). Given that myosin provides the force and motion that underlies contractility in the heart, mavacamten may suppress myosin activity to reduce systolic contraction and improve diastolic relaxation in some hearts (9–12). Biophysical studies have shown that mavacamten stabilizes the super-relaxed state of myosin (also called the myosin OFF state or the interacting heads motif) (9–11, 13, 14), slows down cross-bridge attachment and the rate of inorganic phosphate (Pi) release from myosin (9, 11, 15, 16), and speeds up cross-bridge detachment and the timing of relaxation during diastole (13, 14, 17–19). Mavacamten has recently moved into phase 3 clinical trials for the treatment of obstructive HCM (20), and additional studies will be required to test the potential impact of mavacamten on other forms of HCM (21).

Previous studies on mavacamten in animal models of HCM have focused on mutations in the myosin heavy chain (MYH7 gene) or myosin-binding protein-C (MYBPC3 gene) (9, 10, 12, 14, 16, 22). Myosin regulatory light chain (RLC, MYL2 gene) binds to the neck of myosin and influences cross-bridge activity and myocardial force production. RLC phosphorylation enhances cardiac contractility, and dysregulation of RLC phosphorylation occurs with cardiac stress and the progression to heart failure (23–26). Mutations in RLC also account for ∼2% of known HCM-associated mutations among all sarcomeric proteins (27). To better understand the potential therapeutic impacts of mavacamten, it is important to test the effects of mavacamten on myocardial dysfunction resulting from HCM mutations in different sarcomeric proteins.

Herein we investigated how mavacamten affects myocardial function in two humanized transgenic mouse lines: control mice expressing the human cardiac ventricular isoform of wild-type RLC (WT-RLC), and HCM mice that express the asparagine-to-lysine (N47K) point mutation in RLC. In humans, the N47K mutation in RLC is associated with late-onset HCM and was first identified in a cohort of Danish patients (28). In transgenic mice, this N47K mutation in RLC causes myofibrillar disarray; thickening of the ventricular free wall, septum, and papillary muscles; and increased cardiac mass (29–31). A combination of fiber mechanics and protein studies have shown that the N47K mutation reduces maximal force production, slows down myosin ATPase rates, slows down cross-bridge kinetics, and compromises power output at the protein and myocardial levels (30, 32–34). In intact papillary muscles, N47K prolonged cytosolic Ca2+ transients compared with transgenic controls, consistent with impaired relaxation function often associated with HCM (31).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Models

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and followed the U.S. National Institute of Health’s guidelines for animal use. Transgenic mouse lines were generated by the laboratory of Dr. Szczesna-Cordary, as previously described (31). WT-RLC mice (5 males, transgenic line 4, age 32–34 wk) expressed ∼40% wild-type human ventricular RLC in their hearts. N47K mice (2 females and 3 males, transgenic line 6, age 34–37 wk) expressed ∼100% human ventricular RLC with the N47K mutation in their hearts. Apparent protein expression for both lines was established based on SDS-PAGE gel densitometry of atrial tissue (31). Following euthanasia, hearts were immediately excised and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80°C at the University of Miami. Hearts were shipped overnight on dry ice to Washington State University and stored at −80°C for 3–5 wk until experiments were performed.

Papillary Muscle Preparation

Frozen hearts were placed in a vial with dissecting solution and left on ice for ∼10 min to thaw. They were then transferred onto a dissecting dish, and cardiac papillary muscles were excised from the left ventricle. Papillary muscles were then transferred to a skinning solution, trimmed to ∼180 µm in diameter and 700 µm in length, and skinned overnight at 4°C. Skinned papillary muscle strips were transferred to the storage solution, and if not used immediately for mechanics experiments, strips were stored at −20°C for 1–3 days until experiments were performed.

Solutions

Solutions were adapted from Pulcastro et al. (24) and Tanner et al. (35), with solution formulations calculated via solving ionic equilibria according to Godt and Lindley (36). All concentrations are listed in mM unless otherwise noted. Dissecting solution: 50 N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (=BES), 30.83 K propionate, 10 Na azide, 20 ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (=EGTA), 6.29 MgCl2, 6.09 ATP, 1 1,4-dithiothreitol (=DTT), 20 2,3-butanedione monoxime (=BDM), 50 μM leupeptin, 275 μM pefabloc, and 1 μM trans-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucylamido(4-guanidino)butane (=E-64). Skinning solution: dissecting solution with 1% Triton-XT wt/vol and 50% glycerol wt/vol. Storage solution: dissecting solution with 50% glycerol wt/vol. Relaxing solution: pCa 8.0 (pCa = −log10 [Ca2+]), 20 BES, 5 EGTA, 5 MgATP, 1 Mg2+, 0.3 Pi, 35 phosphocreatine, 300 U/mL creatine kinase, 200 ionic strength (adjusted with Na methanesulfonate), and pH 7.0. Maximal Ca2+-activating solution: same as relaxing solution with pCa 4.8. Rigor solution: same as activating solution without MgATP.

Mavacamten (MYK-461) was purchased from Axon Medichem (Reston, VA) and dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to make a 1 mM stock solution. This stock was then diluted in relaxing (pCa 8.0), activating (pCa 4.8), and rigor (pCa 4.8, 0 MgATP) solutions to yield a final mavacamten concentration of 0.3 µM (with 0.03% DMSO). This 0.3 μM mavacamten concentration was chosen because it represents the IC50 value for inhibiting myosin ATPase activity in biochemical assays using murine and bovine myosin (9).

Muscle Mechanics

Aluminum t-clips were attached to both ends of skinned papillary muscle strips and mounted between a piezoelectric motor (P841.40, Physik Instrumente, Auburn, MA) and a strain gauge (AE801, Kronex, Walnut Creek, CA) in a relaxing solution that contained either no mavacamten or 0.3 μM mavacamten. These mavacamten concentrations were maintained throughout the entire experiment for each strip, and temperature was maintained at 17°C throughout the entire experiment. Sarcomere length was set to 2.2 µm, as described previously (37–39), and strips were Ca2+ activated to assess steady-state isometric tension (=force normalized to the cross-sectional area of each strip) across a range of pCa values.

Stochastic length perturbations were applied for a period of 60 s, using an amplitude distribution with a standard deviation of 0.05% muscle length over the frequency range 0.5–250 Hz (35). Elastic and viscous moduli, E(ω) and V(ω), were measured as a function of angular frequency (ω) from the in-phase and out-of-phase portions of the stress-strain response to the stochastic length perturbation. The complex modulus versus frequency relationship, Y(ω), defined as E(ω) + iV(ω) where i = , from individual fibers was fit to Eq. 1 to estimate six model parameters (A, k, B, 2πb, C, 2πc):

| (1) |

The A term in Eq. 1 reflects the viscoelastic mechanical response of passive, structural elements in the muscle and holds no enzymatic dependence. The parameter A represents the combined mechanical stress of the strip, while the parameter k describes the viscoelasticity of these passive elements, where k = 0 represents a purely elastic response and k = 1 is a purely viscous response. The B and C terms in Eq. 1 reflect enzymatic cross-bridge cycling behavior that produces frequency-dependent shifts in the viscoelastic mechanical response during Ca2+-activated contraction. These B and C processes characterize work-producing (cross-bridge recruitment) and work-absorbing (cross-bridge detachment) muscle responses, respectively. The parameters B and C represent the mechanical stress from the cross bridges (i.e., number of cross bridges formed × their mean stiffness), and the rate parameters 2πb and 2πc reflect cross-bridge kinetics that are sensitive to biochemical perturbations affecting enzymatic activity, such as [MgATP], [MgADP], or [Pi]. Molecular processes contributing to cross-bridge force generation underlie the cross-bridge recruitment rate, 2πb (40–42), while processes contributing to cross-bridge detachment or force decay underlie the cross-bridge detachment rate, 2πc (43).

Under maximally activated conditions (pCa 4.8), [MgATP] was titrated toward rigor (using rigor solution with either no mavacamten or 0.3 μM mavacamten) to measure changes in cross-bridge detachment rate (2πc) as a function of [MgATP]. This 2πc-MgATP relationship was fit to Eq. 2 for each myocardial strip to estimate cross-bridge nucleotide handling rates [i.e., MgADP release rate (k−ADP) and MgATP binding rate (k+ATP)]:

| (2) |

Biochemical Analysis

Remaining pieces of the left ventricular free wall were used for biochemical analysis, as previously described (44). Cardiac fibrosis (i.e., collagen content) was assessed using a hydroxyproline colorimetric assay (Cat. No. K555-100, BioVision). SDS-PAGE gels were stained with Pro-Q diamond phosphostain and Sypro-Ruby total protein stain. The intensity ratio of Pro-Q diamond to Sypro-Ruby was used to assess posttranslational phosphorylation levels for cardiac myosin binding protein-C, troponin I and T, and RLC. Similarly, the intensity of Sypro-Ruby for each of these proteins was normalized to actin to assess total protein content.

Statistical Analysis

All data are listed or plotted as means ± SE. Constrained nonlinear least squares fitting of data to Eq. 1, Eq. 2, or the three-parameter Hill equation (Table 1) was performed using sequential quadratic programming methods in MATLAB (v.7.9.0, The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Statistical analysis applied linear mixed models with main effects of mavacamten, genotype, and their interaction in SPSS (IBM Statistical, Chicago, IL), using pCa, frequency, or [MgATP] as a repeated measure for the force-pCa, modulus-frequency, or kinetics-MgATP relationships.

Table 1.

Characteristics of tension-pCa relationships

| WT-RLC |

N47K |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.3 µM mavacamten | Control | 0.3 µM mavacamten | |

| Tmin, kN m−2 | 2.08 ± 0.23 | 1.68 ± 0.23 | 2.15 ± 0.26 | 2.40 ± 0.22 |

| Tmax, kN m−2 | 15.55 ± 0.71*† | 10.99 ± 0.48† | 12.18 ± 0.51* | 9.56 ± 0.45 |

| Tdev, kN m−2 | 13.46 ± 0.58*† | 9.31 ± 0.39† | 10.03 ± 0.42* | 7.16 ± 0.32 |

| pCa50 | 5.54 ± 0.01* | 5.45 ± 0.01† | 5.58 ± 0.03* | 5.52 ± 0.02 |

| nH | 4.97 ± 0.29† | 5.96 ± 0.36 | 3.94 ± 0.22* | 5.07 ± 0.57 |

| Maxfit, kN m−2 | 13.67 ± 0.61*† | 9.70 ± 0.39† | 10.30 ± 0.45* | 7.56 ± 0.35 |

| n strips | 18 | 14 | 16 | 14 |

Values are means ± SE. tmin, absolute tension value at pCa 8.0; tmax, absolute tension value at pCa 4.8; tdev, Ca2+-activated, developed tension (Tmax − Tmin); RLC, regulatory light chain; WT, wild type. Maxfit, pCa50, and nH represent fit parameters to a three-parameter Hill equation for the developed tension versus pCa relationship: .

P < 0.05 denotes a post hoc effect of mavacamten treatment within a genotype; †P < 0.05 denotes a post hoc effect of the genotype between treatment groups.

RESULTS

Maximal Force and Ca2+ Sensitivity

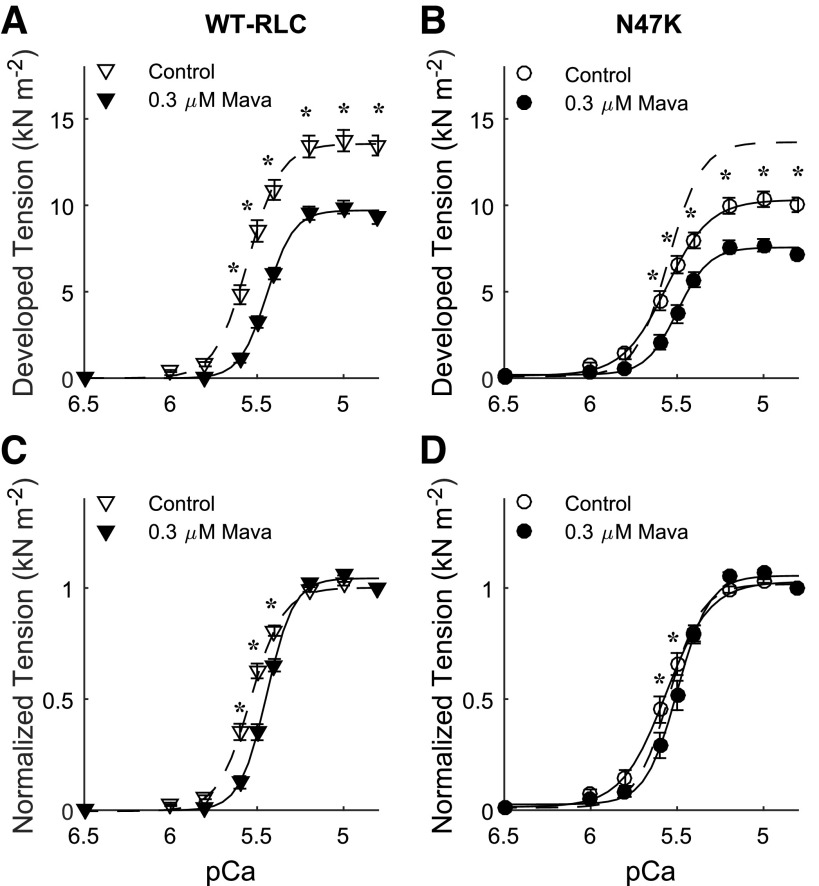

Developed tension (=Ca2+-activated tension minus relaxed tension at pCa 8.0 for each strip) was greater in skinned papillary muscle strips from WT-RLC mice versus N47K mice (Fig. 1, A vs. B). These tension differences between genotypes may follow from greater fibrosis in the N47K hearts than WT-RLC hearts, as hydroxyproline assays showed a 58% increase in collagen content for N47K (P = 0.01; 1.2 ± 0.2 µg/mL for WT-RLC and 1.9 ± 0.1 µg/mL for N47K). We did not detect any differences in protein phosphorylation levels or protein content between genotypes for cardiac myosin binding protein-C; troponin I and T; or RLC (Supplemental Fig. S1; all Supplemental Material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12288281). Tension values were also greater from pCa 5.6-4.8 for control strips (no mavacamten) versus 0.3 µM mavacamten-treated strips from both genotypes. For both genotypes, 0.3 µM mavacamten reduced tension by ∼25% of control values at maximal Ca2+ activation (pCa 4.8). Although subtle, Ca2+ sensitivity of the force-pCa relationships was greater for N47K strips (pCa50, main effect of genotype P = 0.012, Table 1). The 0.3 µM mavacamten reduced Ca2+ sensitivity of the tension-pCa relationship for both genotypes (main effect of treatment P < 0.001), with the shift in pCa50 being greater for WT-RLC versus N47K. Mavacamten-treated strips also showed a significant increase in Hill coefficient (nH, main effects of treatment P = 0.005 and genotype P = 0.011, Table 1), although the effect was greater for N47K strips. This indicates greater cooperativity of the force-pCa relationship in the presence of mavacamten, even though mavacamten inhibited Ca2+-activated force development.

Figure 1.

Ca2+-activated tension is plotted against pCa for myocardial strips from WT-RLC (A) and N47K transgenic mice (B) (2.2 µm sarcomere length). Lines represent fits to a three-parameter Hill equation (see legend of Table 1), with the dashed line for WT-RLC control strips replotted in B. Steady-state isometric tension increased as [Ca2+] increased for all myocardial strips, but Ca2+-activated tension was smaller in strips treated with 0.3 µM mavacamten for both genotypes, compared with control not treated strips. Five mice were used from each genotype, and the number of strips used for these measurements corresponds to the values listed in Table 1 (n = 18 for WT-RLC control, n = 14 for WT-RLC with 0.3 µM mavacamten, n = 16 for N47K control, and n = 14 for N47K with 0.3 µM mavacamten). Significant main effects and interactions: pCa, treatment, pCa × treatment, pCa × genotype, pCa × treatment × genotype at P < 0.001, and genotype at P = 0.003. *P < 0.05 denotes a post hoc effect of mavacamten within a genotype. Normalized Ca2+-activated tension was replotted for WT-RLC (C) and N47K transgenic (D) mice. Lines represent three-parameter Hill fits, with the dashed line for WT-RLC control strips replotted in D. RLC, regulatory light chain; WT, wild type.

Viscoelastic Myocardial Stiffness

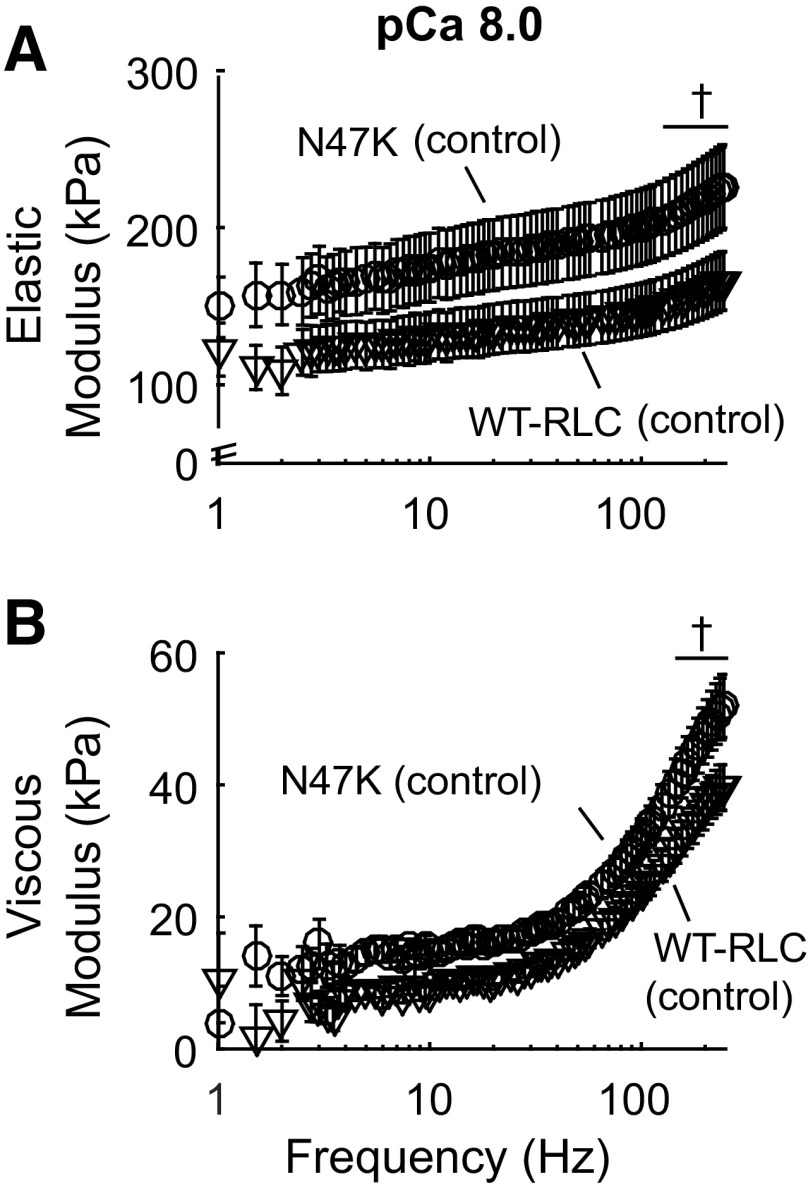

Elastic and viscous modulus values were measured at relaxed (pCa 8.0, Fig. 2) and maximally activated (pCa 4.8, Fig. 3) conditions. Data are only shown for control strips from both genotypes under relaxed conditions because there were no significant effects of mavacamten on elastic or viscous moduli at pCa 8.0 within each genotype (Fig. 2). Elastic and viscous moduli were greater for N47K versus WT-RLC under relaxed conditions (for both control and mavacamten-treated strips), which reflects increased myocardial stiffness that may arise due to increased fibrosis and cardiac remodeling associated with the HCM phenotype in N47K mice (29, 31).

Figure 2.

Elastic (A) and viscous (B) moduli are plotted against frequency under relaxed conditions (pCa 8.0). Viscoelastic myocardial stiffness was greater for N47K strips (○) vs. WT-RLC strips (▽) at the highest frequencies. Data are only shown for control strips because there were no significant effects of mavacamten on viscoelastic stiffness in myocardial strips from either genotype. Five mice were used from each genotype, and the number of strips used for these measurements corresponds to the values listed in Table 1 (n = 18 for WT-RLC control, n = 14 for WT-RLC with 0.3 µM mavacamten, n = 16 for N47K control, and n = 14 for N47K with 0.3 µM mavacamten). Significant main effects and interactions for elastic modulus: frequency (P < 0.001), genotype (P = 0.003); and for viscous modulus: frequency and genotype at P < 0.001. †P < 0.05 denotes a post hoc effect of genotype within treatment group. RLC, regulatory light chain; WT, wild type.

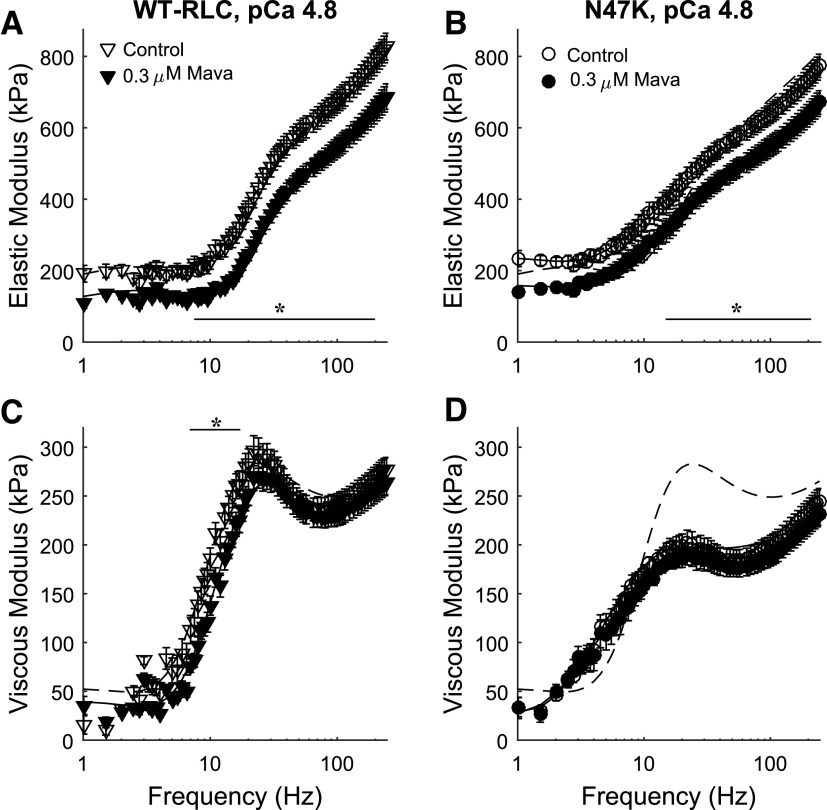

Figure 3.

Elastic (A, B) and viscous (C, D) moduli are plotted against frequency at maximal Ca2+-activated conditions (pCa 4.8). Elastic moduli were greater in control strips for both genotypes above ∼10 Hz. Viscous moduli were greater in control strips between 7 and 17 Hz for WT-RLC mice. Lines represent fits to Eq. 1 for each condition, with the dashed line for control strips from WT-RLC mice replotted in B and C. Five mice were used from each genotype, and the number of strips used for these measurements corresponds to the values listed in Table 1 (n = 18 for WT-RLC control, n = 14 for WT-RLC with 0.3 µM mavacamten, n = 16 for N47K control, and n = 14 for N47K with 0.3 µM mavacamten). Significant main effects and interactions for elastic modulus: frequency, treatment, frequency × treatment, frequency × genotype at P < 0.001; and for viscous modulus: frequency, frequency × genotype, frequency × treatment × genotype at P <0.001, and genotype at P = 0.005. *P < 0.05 denotes a post hoc effect of mavacamten within a genotype. RLC, regulatory light chain; WT, wild type.

At maximal Ca2+ activation, the magnitude of elastic modulus values was greater for control strips for both genotypes at frequencies greater than ∼10 Hz (Fig. 3, A and B). This reflects more bound, cycling cross bridges in control strips for both genotypes, compared to mavacamten-treated strips. There was a slight right-shift toward higher frequencies in the viscous modulus for mavacamten-treated WT-RLC strips (significant between 7 and 17 Hz, P < 0.05), indicating faster overall cross-bridge kinetics (Fig. 3C). There were no obvious shifts in the viscous modulus-frequency relationship in the N47K strips, although the magnitude of viscous modulus values was smaller compared with WT-RLC (indicated by the dotted line, Fig. 3D). Together, these pCa 4.8 moduli data suggest that WT-RLC strips have greater cross-bridge binding than N47K strips and that mavacamten suppresses cross-bridge binding for both genotypes, both of which reflect consistency with tension measurements (Fig. 1).

Cross-Bridge Kinetics as [MgATP] Varied

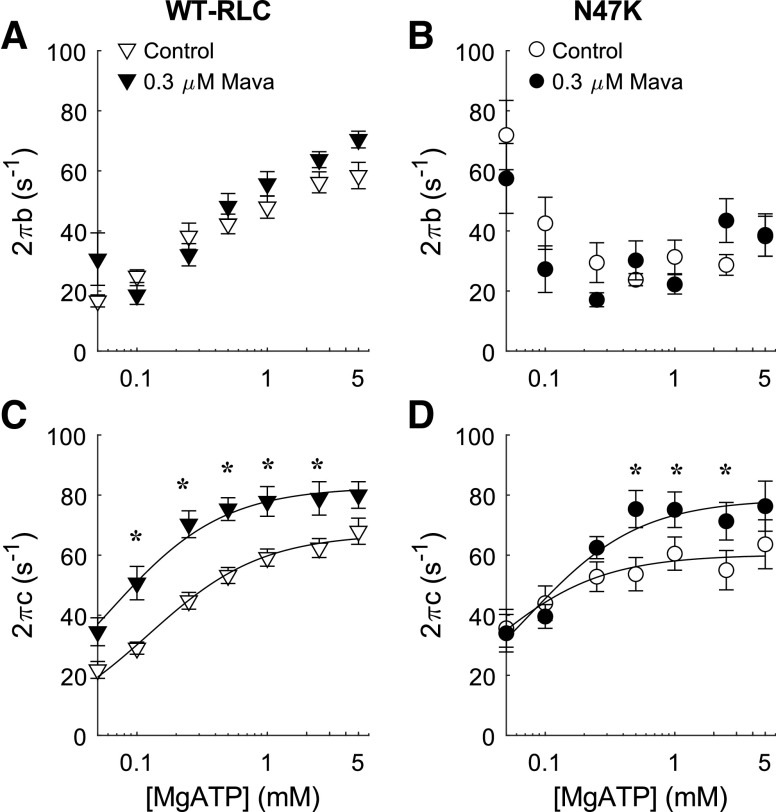

Modulus data were fit to Eq. 1 to estimate cross-bridge kinetics at pCa 4.8 as [MgATP] varied (Fig. 4). Additional model parameters reflecting characteristics of viscoelastic myocardial stiffness (A, k, B, C) are shown in the data supplement (Supplemental Fig. S2). At saturating [MgATP] of 5 mM, cross-bridge recruitment rate (2πb) was faster for WT-RLC strips versus N47K strips (Fig. 4, A and B). Cross-bridge recruitment rate decreased in the presence and absence of mavacamten in WT-RLC strips as [MgATP] decreased (Fig. 4A). Cross-bridge recruitment rate was less sensitive to changes in [MgATP] and mavacamten in N47K strips (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Kinetic parameters from Eq. 1 for cross-bridge recruitment rate (2πb, A and B) and detachment rate (2πc, C and D) are plotted against [MgATP]. Lines represent fits to Eq. 2 for the detachment-MgATP relationship. The rate of cross-bridge detachment was faster in mavacamten-treated myocardial. Five mice were used from each genotype, and the number of strips used for these measurements corresponds to the values listed in Table 2 (n = 15 for WT-RLC control, n = 11 for WT-RLC with 0.3 µM mavacamten, n = 9 for N47K control, and n = 7 for N47K with 0.3 µM mavacamten). Significant main effects and interactions for 2πb: MgATP (P < 0.001), genotype (P = 0.016), MgATP × treatment (P = 0.016), MgATP × genotype (P < 0.001); and for 2πc: MgATP (P < 0.001) and treatment (P < 0.001). *P < 0.05 denotes a post hoc effect of mavacamten within a genotype. RLC, regulatory light chain; WT, wild type.

Near saturating [MgATP], cross-bridge detachment rate (2πc) was not different between genotypes, but detachment rate increased in both groups of fibers with mavacamten treatment (Fig. 4, C and D). For both genotypes, cross-bridge detachment rate decreased in the presence or absence of mavacamten as [MgATP] decreased. These relationships for detachment rate as a function of [MgATP] were fit to Eq. 2 to estimate cross-bridge nucleotide handling rates in each strip. Summary data show that MgADP release rate (k−ADP) did not differ significantly between genotypes. Mavacamten treatment slightly increased MgADP release rate, by ∼15%, in both genotypes (P = 0.025 for main effect of treatment for k−ADP, Table 2). Mavacamten treatment also increased the MgATP binding rate (P = 0.013 for main effect of treatment), with treatment affecting k+ATP more greatly for WT-RLC strips (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimates of myosin nucleotide handling rates from fits to Eq. 2 for the cross-bridge detachment rate (2πc)-[MgATP] relationships from each strip

| WT-RLC |

N47K |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.3 µM mavacamten | Control | 0.3 µM mavacamten | |

| k−ADP, s−1 | 73.69 ± 2.35 | 86.57 ± 7.45 | 83.63 ± 4 .17 | 95.19 ± 6.13 |

| k+ATP, mM s−1 | 550.74 ± 86.14* | 1,246.37 ± 297.88 | 634.00 ± 63.05 | 883.69 ± 111.07 |

| MgATP50, µM | 164.55 ± 18.09* | 103.67 ± 25.41 | 141.50 ± 13.48 | 120.05 ± 18.14 |

| n strips | 15 | 11 | 9 | 7 |

Values are means ± SE. k−ADP, cross-bridge MgADP release rate; k+ATP, cross-bridge MgATP binding rate; MgATP50, [MgATP] concentration at half-maximal detachment rate; RLC, regulatory light chain; WT, wild type.

P < 0.05 denotes a post hoc effect of the genotype between treatment groups.

DISCUSSION

Although several studies have been published on the effects of mavacamten on muscle contraction, this is the first study, to our knowledge, that assessed the effects of mavacamten on myosin cross-bridge nucleotide handling in myocardial strips. We now show that mavacamten increased the myosin MgADP release and MgATP binding rates in permeabilized papillary muscle strips from transgenic WT-RLC (control) mice and the N47K mouse model of HCM. The cardiac muscle mechanics data presented herein are also consistent with prior studies showing that mavacamten decreases myocardial force production (9, 17), inhibits myosin ATPase activity (9, 11, 15), and accelerates cross-bridge detachment rate (16, 17). The known effects of mavacamten on cross-bridge activity are summarized in Fig. 5, and further discussed below.

Figure 5.

Schematic highlighting the effects of mavacamten and genotype on cross-bridge kinetics. A: blue arrows and text summarize known effects of mavacamten from multiple biophysical studies, as well as the findings presented in Figs. 1–4. B: green arrows and text summarize differences between the WT-RLC and N47K genotype, and blue arrows and text summarize the influence of mavacamten. RLC, regulatory light chain; WT, wild type.

Implications of Mavacamten for Contractile Function

We show that a 0.3 µM concentration of mavacamten decreased maximal tension ∼25% in both groups of fibers (Fig. 1), which agrees with other studies showing that mavacamten depresses maximal isometric force in permeabilized cardiac strips from rats (9) and organ donors (17). Mamidi et al. (16) showed that mavacamten only depressed force at submaximal [Ca2+], without significantly affecting maximal force, in permeabilized myocardial strips from wild-type mice and transgenic mice lacking cardiac myosin binding protein-C. The combination of mavacamten stabilizing the myosin OFF state (10, 11), slowing down the rates of force development (16) and cross-bridge recruitment (Fig. 4, A and B), and decreasing ATPase rate in mouse cardiac myofibrils (9) supports the findings that mavacamten suppresses force-generating myosin activity that underlies the force-pCa relationship. It is likely that these decreases in myocardial force also follow from mavacamten decreasing the number of strongly bound cross bridges, a mechanism that is supported by our findings that elastic modulus decreased in mavacamten-treated strips (Fig. 3).

Data from our force-pCa relationships also show that mavacamten treatment reduced Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction (pCa50, Table 1), suggesting that more calcium is required to elicit force generation as myosin ATPase activity is inhibited by mavacamten. Prior studies have shown similar effects of mavacamten in human myocardial strips (17), while others have not reported any significant effects of mavacamten on Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction in mouse (9) or rat myocardial strips (16). Although Ca2+ sensitivity was greater for N47K versus WT-RLC, this effect is subtle, and it could partially follow from mavacamten reducing Ca2+ sensitivity nearly twice as much for WT-RLC strips (Table 1). Given that strong cross-bridge binding helps stabilize and amplify thin-filament activation (45–48), kinetic differences between genotypes could also contribute to the relative differences in mavacamten on Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction. In the absence of mavacamten, slower cross-bridge recruitment for N47K would suggest less strong cross-bridge binding (with similar detachment rate between genotypes), leading to reduced Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction for N47K versus WT-RLC. We observed the opposite in control strips, with Ca2+ sensitivity of force being similar (or even slightly greater for N47K) between genotypes, similar to prior findings (30). In the presence of mavacamten, the rate of MgADP release and MgATP binding increased, yet mavacamten sped up MgATP binding more for WT-RLC than N47K (Table 2, Fig. 5B). This could lead to mavacamten reducing cross-bridge contributions to thin-filament activation more for WT-RLC than N47K, which could partially underlie the greater reduction in Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction for WT-RLC versus N47K strips.

Implications of Mavacamten for Relaxation Function

Observations from recent studies suggest that mavacamten may benefit slow relaxation associated with diastolic dysfunction. This likely follows from multiple mechanisms. Herein we show that mavacamten speeds up the rate of cross-bridge detachment, through a combination of faster MgADP release and MgATP binding (Fig. 4, Table 2). Faster cross-bridge detachment could help to speed up relaxation, which has been shown in electrically paced, mavacamten-treated cardiomyocytes (13, 14, 18, 19). A portion of this could be thin-filament based, as Sparrow et al. (18), used genetically encoded calcium probes conjugated to troponin to show that mavacamten may accelerate the rates of Ca2+ binding and Ca2+ release from troponin. However, these Ca2+ dynamics could be influenced by mavacamten stabilizing the myosin OFF state, thereby leading to fewer cross bridges in the ON state that can bind actin and generating force. This would decrease cross-bridge contributions to thin-filament activation, and computational modeling suggests that greater cooperative activation requires more time to reach steady-state activation levels, effectively slowing the apparent rate of force development (49, 50). Although we did not measure any differences in passive force levels at pCa 8.0 in this study (Table 1), prior measurements from our laboratory showed that mavacamten decreased passive force in human myocardium at physiological temperature (17). Altogether, these findings suggest that mavacamten benefits myocardial relaxation function, which could help HCM patients with elevated myocardial activation levels during diastole.

Different Sensitivities to Mavacamten between WT-RLC and N47K

As discussed earlier, there are some effects of mavacamten on contractility and cross-bridge kinetics that are greater for WT-RLC than for N47K. Albeit speculative, this may result from the N47K mutation altering the myosin OFF-ON equilibrium, thereby leading to different responses upon mavacamten treatment between genotypes. If the N47K mutation reduces the probability that cross bridges can populate the OFF state (or maintain the interacting heads motif along the backbone of the thick filament), then the effects of mavacamten to stabilize this OFF state may be reduced. This could lead to mavacamten having a greater impact on reducing calcium sensitivity of contraction in the WT-RLC strips versus the N47K strips, as we observed (Fig. 1). There may not be significant differences for mavacamten reducing maximal force between genotypes (∼30% reduction for both WT-RLC and N47K) because the pool of cross bridges occupying the OFF state at pCa 4.8 is small for either genotype. It is possible that the effects of mavacamten on Ca2+ sensitivity play a greater role on an in vivo myocardial function than the effects on maximal force, given that in vivo intracellular calcium levels are submaximal (51).

It is also possible that the N47K mutation changes the way that cross bridges bind with actin and transition through the force-generating steps of the cross-bridge cycle (Fig. 5B). In the absence of mavacamten, the rate of cross-bridge recruitment is slower for N47K versus WT-RLC (Fig. 4), which could contribute to the lower force production in N47K strips. Mavacamten produced relatively small or no changes in the cross-bridge recruitment rate for both genotypes, and there was not much sensitivity to changes in MgATP for N47K versus WT-RLC (Fig. 4, A and B). Again, this may suggest the N47K mutation disrupts the typical regulatory recruitment of myosin OFF-ON transition and then the cross-bridge recruitment process when compared with WT-RLC. This finding agrees with prior measurements showing the N47K mutation slowed cross-bridge kinetics compared with WT-RLC (30). In the absence of mavacamten, the rates of cross-bridge detachment were similar between genotypes, which is dominated by the similar rates of MgADP release that dictates the rate-limiting step of the cross-bridge cycle in muscle fibers ((52), Table 2). Upon mavacamten treatment, the rate of cross-bridge detachment, MgADP release, and MgATP binding increased for both genotypes. The increase in MgADP release was similar between genotypes (∼15%), while the rate of MgATP binding increased more for WT-RLC (>200%) than for N47K (∼40%). These kinetic differences suggest that the N47K mutation limits cross-bridge recruitment and alters the effect of mavacamten on nucleotide handling rates in skinned myocardial strips, compared with WT-RLC. Additional biochemical, structural biology, and/or computational modeling studies will be required to definitively illustrate the reason for these mechanistic differences of mavacamten between genotypes.

Conclusions

From a clinical standpoint, mavacamten may benefit some patients with heart disease showing hypercontractility during systole and/or poor relaxation during diastole. With mavacamten reducing maximal force and Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction, it is unlikely that mavacamten would be a viable therapy for all form of heart disease, nor all forms of HCM (21). In HCM patients (28) and this N47K mouse model (29–31), hypertrophy of the ventricle wall is routinely observed. Therefore, additional studies testing how mavacamten administration early in life affects the progression of hypertrophy in these N47K mice could be of interest to the field and benefit our understanding of disease progression. Early administration of mavacamten to mice expressing the myosin R403Q HCM mutation showed beneficial reductions in myofibrillar disarray and alleviated the progression of ventricular hypertrophy (9). Other RLC-N47K specific therapeutic approaches could be useful as well, such as targeted allele-specific RNA interference that was used to ameliorate the cardiac pathology caused by the N47K mutation in transgenic mice (53).

Mavacamten may suppress force generation in muscle at multiple steps of the cross-bridge cycle, via slowing actin-activated ATPase and Pi release to limit cross-bridge binding (11, 15), as well as speeding up myosin MgADP release and MgATP binding to enhance cross-bridge detachment (14, 22). In combination, these data suggest that mavacamten limits cooperative recruitment of myosin cross bridges into force-producing states of the cross-bridge cycle that underlies myocardial contractility. While some of the effects of mavacamten were slightly greater in myocardial strips from WT-RLC versus N47K strips, they were largely consistent for both genotypes (Fig. 5). Mavacamten represents a useful biophysical tool for modulating cardiac function, even though our findings suggest that mavacamten may only provide therapeutic benefits to some forms of heart disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by American Heart Association Grant 19TPA34860008 (to B.C.W.T.), National Science Foundation Grant 1656450 (to B.C.W.T.), and National Institutes of Health Grant R01HL149164 (to B.C.W.T) and Grants R01HL143830 and R56HL146133 (to D.S-C.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.O.A., K.K., D.S-C., and B.C.W.T. conceived and designed research; P.O.A., M.W., Y.B., A.M.H., K.B.A., and K.K. performed experiments; P.O.A., M.W., Y.B., A.M.H., K.B.A., D.S-C., and B.C.W.T. analyzed data; P.O.A., M.W., Y.B., D.S-C., and B.C.W.T. interpreted results of experiments; P.O.A. prepared figures; P.O.A. and B.C.W.T. drafted manuscript; P.O.A., D.S-C., and B.C.W.T. edited and revised manuscript; P.O.A., A.M.H., K.B.A., D.S-C., and B.C.W.T. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, , et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2018. Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 135, 2017. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KA. Mortality in the United States, 2017 key findings data from the National Vital Statistics System. NCHS Data Brief 328: 1–8, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francula-Zaninovic S, Nola IA. Management of measurable variable cardiovascular disease’ risk factors. Curr Cardiol Rev 14: 153–163, 2018. doi: 10.2174/1573403X14666180222102312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 65: 1249–1254, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Der Velden J, Tocchetti CG, Varricchi G, Bianco A, Sequeira V, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Hamdani N, Leite-Moreira AF, Mayr M, Falcao-Pires I, Thum T, Dawson DK, Balligand JL, Heymans S. Metabolic changes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathies: scientific update from the working group of myocardial function of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovasc Res 114: 1273–1280, 2018. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho CY, Carlsen C, Thune JJ, Havndrup O, Bundgaard H, Farrohi F, Rivero J, Cirino AL, Andersen PS, Christiansen M, Maron BJ, Orav EJ, Køber L. Echocardiographic strain imaging to assess early and late consequences of sarcomere mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2: 314–321, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.862128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michels M, Soliman OII, Kofflard MJ, Hoedemaekers YM, Dooijes D, Majoor-Krakauer D, Ten Cate FJ. Diastolic abnormalities as the first feature of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Dutch myosin-binding protein C founder mutations. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2: 58–64, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maron BJ, Maron MS. The 25-year genetic era in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: revisited. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 7: 401–404, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green EM, Wakimoto H, Anderson RL, Evanchik MJ, Gorham JM, Harrison BC, Henze M, Kawas R, Oslob JD, Rodriguez HM, Song Y, Wan W, Leinwand LA, Spudich JA, McDowell RS, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Heart disease: a small-molecule inhibitor of sarcomere contractility suppresses hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Science 351: 617–621, 2016. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson RL, Trivedi DV, Sarkar SS, Henze M, Ma W, Gong H, Rogers CS, Gorham JM, Wong FL, Morck MM, Seidman JG, Ruppel KM, Irving TC, Cooke R, Green EM, Spudich JA. Deciphering the super relaxed state of human β-cardiac myosin and the mode of action of mavacamten from myosin molecules to muscle fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: E8143–E8152, 2018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809540115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohde JA, Roopnarine O, Thomas DD, Muretta JM. Mavacamten stabilizes an autoinhibited state of two-headed cardiac myosin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: E7486–E7494, 2018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720342115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stern JA, Markova S, Ueda Y, Kim JB, Pascoe PJ, Evanchik MJ, Green EM, Harris SP. A small molecule inhibitor of sarcomere contractility acutely relieves left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. PLoS One 11: e0168407, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toepfer CN, Garfinkel AC, Venturini G, Wakimoto H, Repetti G, Alamo L, Sharma A, Agarwal R, Ewoldt JF, Cloonan P, Letendre J, Lun M, Olivotto I, Colan S, Ashley E, Jacoby D, Michels M, Redwood CS, Watkins HC, Day SM, Staples JF, Padrón R, Chopra A, Ho CY, Chen CS, Pereira AC, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Myosin sequestration regulates sarcomere function, cardiomyocyte energetics, and metabolism, informing the pathogenesis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 141: 828–842, 2020. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toepfer CN, Sharma A, Cicconet M, Garfinkel AC, Mücke M, Neyazi M, Willcox JAL, Agarwal R, Schmid M, Rao J, Ewoldt J, Pourquié O, Chopra A, Chen CS, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. SarcTrack. Circ Res 124: 1172–1183, 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawas RF, Anderson RL, Bartholomew Ingle SR, Song Y, Sran AS, Rodriguez HM. A small-molecule modulator of cardiac myosin acts on multiple stages of the myosin chemomechanical cycle. J Biol Chem 292: 16571–16577, 2017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.776815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mamidi R, Li J, Doh CY, Verma S, Stelzer JE. Impact of the myosin modulator mavacamten on force generation and cross-bridge behavior in a murine model of hypercontractility. J Am Heart Assoc 7: 1–15, 2018. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Awinda PO, Bishaw Y, Watanabe M, Guglin MA, Campbell KS, Tanner BCW. Effects of mavacamten on Ca 2+ ‐sensitivity of contraction as sarcomere length varied in human myocardium. Br J Pharmacol 177: 5609–5621, 2020. doi: 10.1111/bph.15271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sparrow AJ, Sievert K, Patel S, Chang YF, Broyles CN, Brook FA, Watkins H, Geeves MA, Redwood CS, Robinson P, Daniels MJ. Measurement of myofilament-localized calcium dynamics in adult cardiomyocytes and the effect of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations. Circ Res 124: 1228–1239, 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sparrow AJ, Watkins H, Daniels MJ, Redwood C, Robinson P. Mavacamten rescues increased myofilament calcium sensitivity and dysregulation of Ca2+ flux caused by thin filament hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 318: H715–H722, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00023.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heitner SB, Jacoby D, Lester SJ, Owens A, Wang A, Zhang D, Lambing J, Lee J, Semigran M, Sehnert AJ. Mavacamten treatment for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 170: 741–748, 2019. doi: 10.7326/M18-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho CY, Mealiffe ME, Bach RG, Bhattacharya M, Choudhury L, Edelberg JM, Hegde SM, Jacoby D, Lakdawala NK, Lester SJ, Ma Y, Marian AJ, Nagueh SF, Owens A, Rader F, Saberi S, Sehnert AJ, Sherrid MV, Solomon SD, Wang A, Wever-Pinzon O, Wong TC, Heitner SB. Evaluation of mavacamten in symptomatic patients with nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 75: 2649–2660, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toepfer CN, Wakimoto H, Garfinkel AC, McDonough B, Liao D, Jiang J, Tai AC, Gorham JM, Lunde IG, Lun M, Lynch TL, McNamara JW, Sadayappan S, Redwood CS, Watkins HC, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations in MYBPC3 dysregulate myosin. Sci Transl Med 11: eaat1199, 2019. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang AN, Battiprolu PK, Cowley PM, Chen G, Gerard RD, Pinto JR, Hill JA, Baker AJ, Kamm KE, Stull JT. Constitutive phosphorylation of cardiac myosin regulatory light chain in vivo. J Biol Chem 290: 10703–10716, 2015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.642165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pulcastro HC, Awinda PO, Breithaupt JJ, Tanner BCW. Effects of myosin light chain phosphorylation on length-dependent myosin kinetics in skinned rat myocardium. Arch Biochem Biophys 601: 56–68, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheikh F, Ouyang K, Campbell SG, Lyon RC, Chuang J, Fitzsimons D, Tangney J, Hidalgo CG, Chung CS, Cheng H, Dalton ND, Gu Y, Kasahara H, Ghassemian M, Omens JH, Peterson KL, Granzier HL, Moss RL, McCulloch AD, Chen J. Mouse and computational models link Mlc2v dephosphorylation to altered myosin kinetics in early cardiac disease. J Clin Invest 122: 1209–1221, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI61134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan CC, Muthu P, Kazmierczak K, Liang J, Huang W, Irving TC, Kanashiro-Takeuchi RM, Hare JM, Szczesna-Cordary D. Constitutive phosphorylation of cardiac myosin regulatory light chain prevents development of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: E4138–E4146, 2015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505819112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadav S, Sitbon YH, Kazmierczak K, Szczesna-Cordary D. Hereditary heart disease: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and animal models of HCM, RCM, and DCM associated with mutations in cardiac myosin light chains. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol 471: 683–699, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s00424-019-02257-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersen PS, Havndrup O, Bundgaard H, Moolman-Smook JC, Larsen LA, Mogensen J, Brink PA, Børglum AD, Corfield VA, Kjeldsen K, Vuust J, Christiansen M. Myosin light chain mutations in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: phenotypic presentation and frequency in Danish and South African populations. J Med Genet 38: E43, 2001. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.12.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abraham TP, Jones M, Kazmierczak K, Liang HY, Pinheiro AC, Wagg CS, Lopaschuk GD, Szczesna-Cordary D. Diastolic dysfunction in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy transgenic model mice. Cardiovasc Res 82: 84–92, 2009. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang L, Kazmierczak K, Yuan CC, Yadav S, Kawai M, Szczesna-Cordary D. Cardiac contractility, motor function, and cross-bridge kinetics in N47K-RLC mutant mice. FEBS J 284: 1897–1913, 2017. doi: 10.1111/febs.14096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Xu Y, Kerrick WGL, Wang Y, Guzman G, Diaz-Perez Z, Szczesna-Cordary D. Prolonged Ca2+ and force transients in myosin RLC transgenic mouse fibers expressing malignant and benign FHC mutations. J Mol Biol 361: 286–299, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenberg MJ, Kazmierczak K, Szczesna-Cordary D, Moore JR. Cardiomyopathy-linked myosin regulatory light chain mutations disrupt myosin strain-dependent biochemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 17403–17408, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009619107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenberg MJ, Watt JD, Jones M, Kazmierczak K, Szczesna-Cordary D, Moore JR. Regulatory light chain mutations associated with cardiomyopathy affect myosin mechanics and kinetics. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 108–115, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.09.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karabina A, Kazmierczak K, Szczesna-Cordary D, Moore JR. Myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation enhances cardiac β-myosin in vitro motility under load. Arch Biochem Biophys 580: 14–21, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanner BCW, Wang Y, Maughan DW, Palmer BM. Measuring myosin cross-bridge attachment time in activated muscle fibers using stochastic vs. sinusoidal length perturbation analysis. J Appl Physiol 110: 1101–1108, 2011. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00800.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godt RE, Lindley BD. Influence of temperature upon contractile activation and isometric force production in mechanically skinned muscle fibers of the frog. J Gen Physiol 80: 279–297, 1982. doi: 10.1085/jgp.80.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kieu TT, Awinda PO, Tanner BCW. Omecamtiv Mecarbil slows myosin kinetics in skinned rat myocardium at physiological temperature. Biophys J 116: 2149–2160, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pulcastro HC, Awinda PO, Methawasin M, Granzier H, Dong W, Tanner BCW. Increased titin compliance reduced length-dependent contraction and slowed cross-bridge kinetics in skinned myocardial strips from Rbm20ΔRRM mice. Front Physiol 7: 322, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanner BCW, Breithaupt JJ, Awinda PO. Myosin MgADP release rate decreases at longer sarcomere length to prolong myosin attachment time in skinned rat myocardium. Am J Physiol Circ Physiol 309: H2087–H2097, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00555.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell KB, Chandra M, Kirkpatrick RD, Slinker BK, Hunter WC. Interpreting cardiac muscle force-length dynamics using a novel functional model. Am J Physiol Hear Circ Physiol 286: H1535–H1545, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01029.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawai M, Brandt PW. Sinusoidal analysis: a high resolution method for correlating biochemical reactions with physiological processes in activated skeletal muscles of rabbit, frog and crayfish. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 1: 279–303, 1980. doi: 10.1007/BF00711932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer BM, Wang Y, Miller MS. Distribution of myosin attachment times predicted from viscoelastic mechanics of striated muscle. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011: 1–16, 2011. doi: 10.1155/2011/592343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer BM, Suzuki T, Wang Y, Barnes WD, Miller MS, Maughan DW. Two-state model of acto-myosin attachment-detachment predicts C-process of sinusoidal analysis. Biophys J 93: 760–769, 2007. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fenwick AJ, Awinda PO, Yarbrough-Jones JA, Eldridge JA, Rodgers BD, Bertrand WT. Demembranated skeletal and cardiac fibers produce less force with altered cross-bridge kinetics in a mouse model for limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2i. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 317: 226–234, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00524.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bremel R, Weber A. Cooperation within actin filament in vertebrate skeletal muscle. Nat New Biol 238: 97–101, 1972. doi: 10.1038/newbio238097a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKillop DF, Geeves MA. Regulation of the interaction between actin and myosin subfragment 1: evidence for three states of the thin filament. Biophys J 65: 693–701, 1993. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81110-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Metzger JM. Myosin binding-induced cooperative activation of the thin filament in cardiac myocytes and skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J 68: 1430–1442, 1995. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80316-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Razumova MV, Bukatina AE, Campbell KB. Different myofilament nearest-neighbor interactions have distinctive effects on contractile behavior. Biophys J 78: 3120–3137, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76849-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campbell K. Rate constant of muscle force redevelopment reflects cooperative activation as well as cross-bridge kinetics. Biophys J 72: 254–262, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78664-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanner BCW, Daniel TL, Regnier M. Filament compliance influences cooperative activation of thin filaments and the dynamics of force production in skeletal muscle. PLoS Comput Biol 8: e1002506, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation–contraction coupling. Nature 415: 198–205, 2002. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siemankowski RF, Wiseman MO, White HD. ADP dissociation from actomyosin subfragment 1 is sufficiently slow to limit the unloaded shortening velocity in vertebrate muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 658–662, 1985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zaleta-Rivera K, Dainis A, Ribeiro AJS, Cordero P, Rubio G, Shang C, Liu J, Finsterbach T, Parikh VN, Sutton S, Seo K, Sinha N, Jain N, Huang Y, Hajjar RJ, Kay MA, Szczesna-Cordary D, Pruitt BL, Wheeler MT, Ashley EA. Allele-specific silencing ameliorates restrictive cardiomyopathy attributable to a human myosin regulatory light chain mutation. Circulation 140: 765–778, 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]