Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the primary pathological factors that contributes to aging-related cognitive impairments, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. We recently reported that old DM rats exhibited impaired myogenic responses of the cerebral arteries and arterioles, poor cerebral blood flow autoregulation, enhanced blood-brain barrier (BBB) leakage, and cognitive impairments. These changes were associated with diminished vascular smooth muscle cell contractile capability linked to elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduced ATP production. In the present study, using a nonobese T2DN DM rat, we isolated parenchymal arterioles (PAs), cultured cerebral microvascular pericytes, and examined whether cerebrovascular pericyte in DM is damaged and whether pericyte dysfunction may play a role in the regulation of cerebral hemodynamics and BBB integrity. We found that ROS and mitochondrial superoxide production were elevated in PAs isolated from old DM rats and in high glucose (HG)-treated α-smooth muscle actin-positive pericytes. HG-treated pericytes displayed decreased contractile capability in association with diminished mitochondrial respiration and ATP production. Additionally, the expression of advanced glycation end products, transforming growth factor-β, vascular endothelial growth factor, and fibronectin were enhanced, but claudin 5 and integrin β1 was reduced in the brain of old DM rats and HG-treated pericytes. Further, endothelial tight junction and pericyte coverage on microvessels were reduced in the cortex of old DM rats. These results demonstrate our previous findings that the impaired cerebral hemodynamics and BBB leakage and cognitive impairments in the same old DM model are associated with hyperglycemia-induced cerebrovascular pericyte dysfunction.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This study demonstrates that the loss of contractile capability in pericytes in diabetes is associated with enhanced ROS and reduced ATP production. Enhanced advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in diabetes accompany with reduced pericyte and endothelial tight junction coverage in the cortical capillaries of old diabetic rats. These results suggest our previous findings that the impaired cerebral hemodynamics, BBB leakage, and cognitive impairments in old DM model are associated with hyperglycemia-induced cerebrovascular pericyte dysfunction.

Keywords: aging, blood-brain barrier, cerebral vascular pericytes, diabetes mellitus, oxidative stress

INTRODUCTION

Emerging evidence indicates that individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM), especially type 2 diabetes, have a higher risk of developing cognitive impairments, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia (1, 2). AD and vascular dementia are the most common forms of cognitive impairments that account for 60%–80% and 5%–10% of all dementia cases, respectively (3, 4). The annual cost for the treatment of dementia is $159 billion and is projected to rise to $511 billion by 2040 (2, 5). This risk factor for cognitive impairments increases with age: one in eight people over the age of 65 have AD, and this number increases to one in two over the age of 85 (2, 6). Vascular damage in cerebral circulation is one of the major complications in DM. It becomes more severe when superposed with aging (7–10); however, whether it directly contributes to the development of cognitive impairments and the underlying mechanisms are not fully illuminated.

Epidemiological and animal studies demonstrated that elderly DM individuals display enhanced blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability that is associated with loss of cerebral vascular pericytes and endothelial tight junctions (11–14); despite this, there is disagreement in terms of whether these are caused by hyperglycemia (15, 16). Cerebrovascular pericytes play a critical role in maintaining cerebral vascular function. They are mural cells of the cerebral microvasculature, including precapillary arterioles, capillaries, and postcapillary venules. They are embedded in the cerebral capillary basement membrane and wrap around the endothelial cells (ECs) (17–19). Pericytes are multifunctional. They maintain the capillary barriers and BBB integrity, regulate cerebral blood flow (CBF), and control leukocyte passage through the vessel wall (17, 18, 20–22). Pericytes also play a role in angiogenesis, phagocytosis, and clearance of cell debris and display multipotent stem cell activities (15, 17–23). Pericytes consist of several subtypes: ensheathing pericytes express α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and can be found in the wall of the precapillary arterioles; mesh pericytes have short processes wrapping around the capillary longitudinally; thin-strand pericytes on the capillaries do not have the contractile capability (24, 25). As such, no specific pericyte markers, including platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFR-β), neural-glial antigen (NG2), α-SMA, aminopeptidase N (CD13), desmin (DES), have been identified because of their dynamic diverse characteristics and morphologies between organs and developmental stages, and along the vessels when there is a transition from precapillary arterioles to capillaries and postcapillary venules (17, 20, 26–29). In the brain, pericytes interact with astrocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and ECs to modulate the distribution of oxygen and nutrients to neuronal tissue. Pericytes that are localized on the wall of first- to fourth-order precapillary arterioles are α-SMA positive (30). These cells regulate CBF by controlling capillary diameter via their contractile capability (22, 31–33). Along with ECs, neuron, and astrocyte, pericyte is a vital component of the neurovascular unit, which abuts the vasculature and regulates BBB permeability by substantial intercellular communication in response to neuronal activity without alternations in transluminal pressure (19, 34). Pericyte loss in the retina can be directly caused by hyperglycemia in association with capillary remodeling and reduces the survival of ECs in diabetes (35, 36). Diabetic retinopathy has been reported to be an indicator of an increased risk for the development of cognitive impairments, as retinal microvascular shares prominent similarities with the cerebral microvasculature (35, 37). Loss of cerebral pericytes results in BBB breakdown and AD-like neuronal loss (38, 39).

Our recent reports using a type 2 diabetic rat (T2DN) demonstrated that this nonobese DM model displayed massive BBB leakage following acute elevations in pressure and cognitive impairments upon aging, which was associated with reduced myogenic response and CBF autoregulation, neurovascular uncoupling, decreased endothelial tight junction and pericyte coverage on cerebral capillaries in the hippocampus, and neurodegeneration (40). We also reported that the impaired myogenic response of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) in T2DN rats is associated with an enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, imbalanced mitochondrial dynamics, and depletion of ATP in VSMCs (41). Of note, the impaired cerebral hemodynamics found in our previous studies was recently observed to occur not only in the surface cortex and MCA but also in the deep cortex and parenchymal arteriole (PA) in old T2DN rats (40). Although the contractile cells that play an essential role in the regulation of vasoconstriction in the MCA are mainly VSMCs, they are not the only cell type that regulates the diameters of precapillary arterioles. Pericytes that express the contractile protein α-SMA may also play an important role in the regulation of vasoconstriction in cerebral arterioles (22, 31–33). The present study continues our previous works aiming to explore whether the contractile capability of α-SMA positive pericytes is also altered in old DM rats and whether pericyte dysfunction and loss of endothelial tight junctions in this DM model are associated with prolonged hyperglycemia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

These experiments were performed using old (18 mo) male nondiabetic Sprague-Dawley (SD) control and age-matched diabetic T2DN rats. The rats were obtained from our inbred colonies maintained at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC). All animals were housed according to standard laboratory animal conditions, including a 12-h light-dark cycle and with free access to food (0.1% sodium, Teklad traditional diet 7034, Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) and water ad libitum throughout the study. The UMMC animal care facility is approved by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All animal experiments were conducted following protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the UMMC.

Human Brain Microvascular Pericyte Studies

Experiments were performed using human brain microvascular pericyte (HBMVPs; cAP-0030, Angio-proteomie, Boston, MA) isolated from human brain cortical tissue. The cells were cultured in six-well plates precoated with Quick Coating Solution (cAP-01, Angio-proteomie) and incubated in pericyte growth medium (cAP-09, Angio-proteomie) supplied with normal glucose (NG, 5.5 mM) or high glucose (HG, 20 mM) for 14 days before subsequent experiments. The purity of the cells was validated by > 95% positively staining with antibodies against α-SMA, PDGFR-β, DES, and CD13. Early passages (P3-P4) of HBMVPs were used in all experiments. All experiments using HBMVPs were repeated three times, and triplicate wells were used for each experiment.

Cerebral PA Isolation

PAs were dissected as we described previously (34, 40, 42, 43). Briefly, the rats were sacrificed with 4% isoflurane, and the brains were removed. A small portion of the brain containing MCA was separated, and PAs branching directly from the MCA were dissected for subsequent study. Isolated PAs with an inner diameter of 20–40 µm (40) and covered with α-SMA- and PDGFR-β-positive-stained pericytes were used in this study.

Determination of ROS Production

ROS production was compared with the superoxide indicator dihydroethidium (DHE; D11347, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and mitochondrial ROS production was measured using the MitoSOX Red Mitochondrial Superoxide Indicator kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PAs freshly isolated from old SD and T2DN rats, and in NG- and HG-treated HBMVPs. PAs or HBMVPs were placed in a six-well plate, respectively, and incubated with DHE (10 µM) or MitoSOX (5 µM) for 10 min at room temperature, respectively. The vessels were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA), mounted, and coverslipped with VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium (H-1000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). PAs were imaged with 405-nm excitation and 590-nm emission (41, 44) using the Nikon Eclipse 55i fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY). Live NG- and HG-treated HBMVPs were photographed at the same excitation wavelength by the Lionheart automated live-cell imager (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). Relative ROS or mitochondrial ROS production was quantified with an Image J software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html) by comparing the mean intensities of the red fluorescence in different groups as we previously described (41).

Determination of Mitochondrial Respiration and ATP Production

Mitochondrial respiration and ATP production were compared in NG- or HG-treated HBMVPs using the Seahorse XFe24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) by measurement of the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) as we previously described (41, 45). Briefly, NG- or HG- treated HBMVPs (5 × 103/well) were seeded on an XFe24 plate that was precoated with Corning Cell-Tak Cell and Tissue Adhesive (3.5 µg/cm2, CB40241, Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON) in the pericyte growth medium. The same concentration of mannitol was applied as an osmotic control for HG. After HBMVPs attached to the plate, the cells were washed with PBS and replaced with XF base medium containing 10 mM glucose, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate; pH7.4, and incubated at 37°C for 1 h in the air. OCR and ECAR in NG- and HG-treated cells were compared in two groups: under basal conditions and after sequential addition of oligomycin (1 µM), carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 2 µM), rotenone (0.5 µM), and antimycin-A (0.5 µM) for three cycles. Results generated by the Agilent Seahorse XFe24 Analyzer Wave 2.4 software were normalized with the protein concentrations. The maximal effects at 30 min and 40 min followed the administration of oligomycin were averaged after the responses were fully developed. A calculation of oligomycin-induced ECAR − basal ECAR was used to determine glycolytic reserve capacity (41, 46).

Comparison of Cell Proliferation in NG- and HG-Treated HBMVPs

Cell proliferation was compared in NG- and HG-treated HBMVPs using an MTS Assay Kit (ab197010, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) according to the manufacturer protocol. Briefly, NG- or HG-treated HBMVPs (5 × 103/well) were seeded onto a 96-well plate. MTS reagent was placed to each well, and the cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 4 h. The soluble colored formazan dye generated from viable cells was quantified by comparing the absorbance at 490 nm using a plate reader (BioTek).

Comparison of the Contractile Capability of NG- and HG-Treated HBMVPs

The contractile capability of NG- and HG-treated HBMVPs was determined using a collagen-based Contraction Assay Kit (CBA-201, Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA), as we previously described (34, 41). Briefly, NG- or HG-treated HBMVPs were harvested and resuspended in pericyte growth medium at 3 × 106 cells/mL. The cells were mixed with a collagen gel working solution at a ratio of 1:4. After the collagen was polymerized at 37°C for 1 h, the cells were allowed to develop contractile force by incubation for another 24 h. The stressed matrix of collagen gel was then gently released from the sides of the 24-well plate, and changes in the size of collagen gel area were measured after stimulation and quantified with Image J software using the following equation (34, 40, 41, 47, 48): contraction (%) = [(Areawell − Areagel)/Areawell] × 100%. The absolute values of the contraction areas in NG- and HG-treated cells were also recorded.

Immunofluorescence Staining

HBMVPs were fixed with 3.7% PFA, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), blocked with 1% BSA, incubated with primary antibodies against α-SMA (1: 300; A2547, Sigma-Aldrich), PDGFR-β (1: 500; ab32570, Abcam), DES (1: 200; sc-23879, Santa Cruz), and CD13 (1: 200; ab108310, Abcam), followed by Alexa Fluor 555- or Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cells were mounted and coverslipped with an antifade mounting medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; H-1200, Vector Laboratories), and images were captured with an Eclipse 55i fluorescence microscope connected with a DS-FiL1 color camera (Nikon, Melville, NY) at a magnification of ×850. Experiments were repeated three times in triplicates.

Freshly isolated PAs were fixed with 3.7% PFA and incubated with primary antibodies against α-SMA (1:300; A2547, Sigma-Aldrich) and PDGFR-β (1: 200; ab32570, Abcam) in a blocking and staining solution (10% BSA, 2% Triton X-100, and 0.02% sodium azide), followed by Alexa Fluor 555- or Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The slides were imaged with a Nikon C2+ confocal head mounted on an Eclipse Ti2 inverted microscope (Nikon) using a ×60 oil immersion objective (total magnification of ×1,320).

The brains were collected and fixed with 4% PFA, followed by 10%, then 30% cytoprotective solution, as we previously described (40). The brains were embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. embedding compound (4583, Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA), and 50-µm-thick frozen sections were prepared using a cryostat (CryoStar NX50, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The sections were stored in an FD Section Storage Solution (PC101, FD NeuroTechnologies, Inc., Columbia, MD) at −20°C to preserve an optimal morphology and antigenicity. Free-floating sections were incubated with 0.1% trypsin at 37°C for 2 h and sodium citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0) at 80°C for 4 h for enzymatic and heat-mediated antigen retrieval, respectively. The sections were rinsed with PBST (phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20), incubated with primary antibodies against Collagen IV (Col IV; 1:300; ab6586, Abcam, or 1:200; MA1-22148, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the blocking and staining solution at 4°C for 72 h, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight. The brain sections were then washed by PBST three times at 80 rpm and incubated with antibodies against claudin 5 (CLDN5; 1:300; 4C3C2, Thermo Fisher Scientific), occludin (OCLN; 1:300; sc-133256, Santa Cruz) for tight junctions, or against neuro-glial antigen 2 (NG2; 1:200; ab50009, Abcam) or PDGFR-β (1:200; ab32570, Abcam) for pericytes. The brain sections were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 555-labeled secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and mounted with DAPI antifade mounting medium (H-1200, Vector Laboratories) before being coverslipped. Images were acquired for comparing tight junction or pericyte coverage using a Nikon C2+ laser scanning confocal head mounted on an Eclipse Ti2 inverted microscope (Nikon) using a ×20 objective lens and a ×1.6 or ×4.5 digital zoom (total magnification of ×704 and ×1,980, respectively). A series of optical sections were captured with a Z step, and 10 images were used to generate a Z-projection. Four rats of each group were studied, and three to four sections per animal were sampled for quantification. The area of OCLN/Col IV or CLDN5/Col IV represented the percentage of the tight junction area on the capillary. Percentage area of pericytes coverage was indicated by the area of NG2 or PDGFR-β divided by the area of Col IV, both of which were measured using NIS-Elements Imaging Software 4.6 (Nikon).

All primary antibodies were validated in our recently published manuscripts (40, 49), consistent with previous reports (50, 51). We also used secondary antibodies only to ensure there was no nonspecific fluorescent signals under the same conditions as we used for immunofluorescence staining (data not shown).

Western Blot

Western blots were performed using proteins obtained from NG- or HG-treated HBMVPs or brain tissues of SD or DM rats. Briefly, cells or brains were homogenized with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (R0278, Sigma-Aldrich) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (PPI; Thermo Fisher Scientific), sonicated, and centrifuged at 9,000 g for 15 min. The concentrations of protein in the cell and brain supernatants were determined using a Bradford method (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Equal volumes and amounts of proteins (20 μL, 25 μg) were prepared in 2× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) with 2-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad), denatured, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred to 0.2-μm nitrocellulose membranes by Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with a blocking solution in TBST (20 mM Tris, 500 mM sodium chloride, and 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.5), and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies against advanced glycation end products (AGEs; 1:1,000; ab23722, Abcam), integrin β1 (ITGB1; 1:2,000; ab179471, Abcam), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; 1:1,000; sc-7269, Santa Cruz), fibronectin (FN; 1:1,000; NBP1-91258, Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO), CLDN5 (1:1,000; 34–1600, Thermo Fisher Scientific), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β1; 1:500; sc-146, Santa Cruz), and GAPDH (1:2,500; 2118S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). The membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (1:10,000; ab6271, Abcam) or rabbit anti-mouse IgG H&L (HRP) (1:10,000; ab6728, Abcam) secondary antibodies. SuperSignalTM West Dura Extended Duration substrate (34076, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the membrane for chemiluminescent detection. A ChemiDoc Imager system (Bio-Rad) was used to analyze the relative intensities of immunoreactive bands.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Nondiabetic SD and age-matched DM rats were euthanized with isoflurane. A small block (around 1 mm3) of the cortex was collected and immediately immersed in 4% formaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4), followed by incubation in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M PB. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) samples were sectioned and imaged by the UMMC Electron Microscopy facility in the Pathology Department.

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean values ± SE. The significance of differences in corresponding values between groups examined in immunofluorescence staining, Western blot, MTS test, and contraction assay was analyzed by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. A two-way ANOVA for repeated comparisons followed by a Holm–Sidak post hoc test was used to compare the significant difference between groups for the measurements of the OCR and ECAR. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Validation of HBMVPs and Identification of PAs

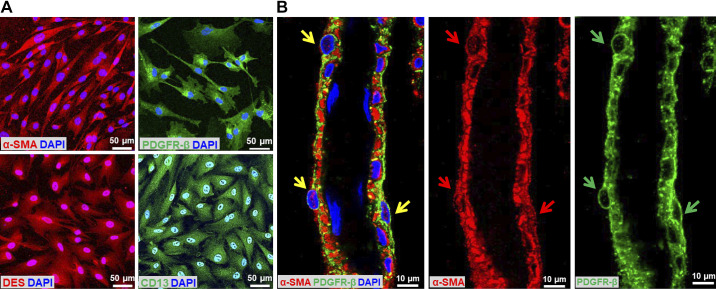

We first determined the percentage of the HBMVPs that express α-SMA, PDGFR-β, DES, and CD13 by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 1A). We found that >95% of the cells expressed all four markers.

Figure 1.

Validation of HBMVPs and identification of PAs. A: representative images of the expression of α-SMA-, PDGFR-β-, DES-, and CD13-positive HBMVPs. Images were captured with an Eclipse 55i fluorescence microscope connected with a DS-FiL1 color camera (Nikon, Melville, NY) at the magnification of ×850. B: representative image of isolated PAs covered with α-SMA- and PDGFR-β-positive-stained pericytes. Yellow arrows point to α-SMA- and PDGFR-β-positive pericytes. Red and green arrows point to α-SMA- and PDGFR-β-positive pericytes, respectively. The slides were imaged with a Nikon C2+ confocal head mounted on an Eclipse Ti2 inverted microscope (Nikon) using a ×60 oil immersion objective (total magnification of ×1,320). DES, desmin; HBMVPs, human brain microvascular pericytes; PAs, parenchymal arterioles; PDGFR-β, platelet-derived growth factor receptor β; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin.

We previously reported that the myogenic response of the PAs isolated from the lenticulostriate arteriolar bed was impaired in both young and old T2DN rats (40). These PAs (inner diameters of 20–40 µm) were located in the deep cortex of adult rats (40). We also found that CBF in the deep cortex failed to respond to pressures detected with an implanted laser-Doppler flowmeter (PF5010, Perimed Inc.) probe into the brain at a depth of 1.5–2 mm (40, 52). In the present study, we carefully dissected the PAs as we previously described (40, 53, 54) and demonstrated that the freshly isolated PAs were covered with α-SMA- and PDGFR-β-positive-stained pericytes (Fig. 1B). These vessels were used for the examination of ROS production by pericytes.

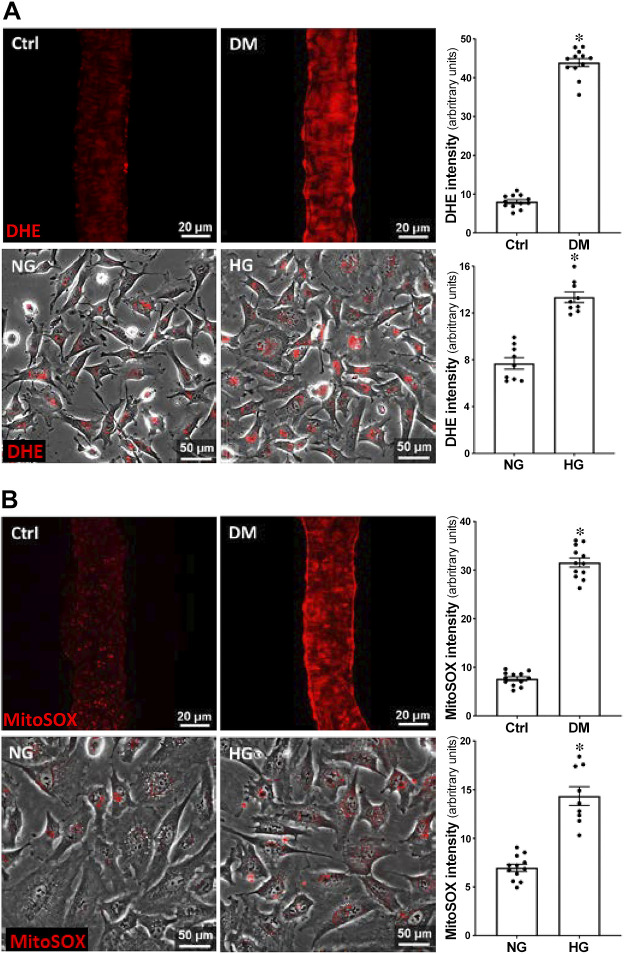

Comparison of the Production of ROS and Mitochondrial Superoxide in PAs Isolated from DM versus Non-DM rats and in HG- versus NG-Treated HBMVPs

A comparison of ROS production in PAs isolated from control and DM rats and in NG- and HG-treated HBMVPs is presented in Fig. 2. DHE fluorescence intensity was fourfold [43.90 ± 1.05 vs. 8.07 ± 0.50 arbitrary unit (a.u.)] and onefold (13.35 ± 0.45 vs. 7.69 ± 0.49 a.u.) higher in PAs of DM rats and HG-treated HBMVPs, respectively, compared with age-matched non-DM rats (Fig. 2A, top) and NG-treated cells (Fig. 2A, bottom). Similarly, MitoSOX fluorescence intensity was threefold (31.56 ± 0.94 vs. 7.64 ± 0.41 a.u.) and onefold (14.35 ± 0.96 vs. 6.98 ± 0.36 a.u.) higher in PAs of DM rats (Fig. 2B, top) and HG-treated HBMVPs (Fig. 2B, bottom), respectively, than non-DM rats and NG-treated cells.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the production of ROS and mitochondrial superoxide in PAs isolated from DM vs. non-DM rats and in HG- vs. NG-treated HBMVPs. A: representative images of DHE staining (left) and relative quantitation (right) of DHE fluorescence intensity in PAs isolated from DM vs. nondiabetic Ctrl rats (top) and HG- vs. NG-treated HBMVPs (bottom). B: representative images of MitoSOX staining (left) and quantitation (right) of MitoSOX fluorescence intensity in PAs isolated from Ctrl vs. DM rats (top) and HG- vs. NG-treated HBMVPs (bottom). PAs were imaged with 405-nm excitation and 590-nm emission using the Nikon Eclipse 55i fluorescence microscope. Live cells were photographed at the same excitation and emission wavelengths by the Lionheart automated live-cell imager. N = 12 vessels/6 rats per group. Experiments using the HBMVPs were repeated three times in triplicates. *P < 0.05 from the corresponding value in DM versus age-matched non-DM rats or HG- versus NG-treated HBMVPs. Ctrl, control; DHE, dihydroethidium; DM, diabetes mellitus; HBMVPs, human brain microvascular pericytes; HG, high glucose; NG, normal glucose; PA, parenchymal arterioles; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

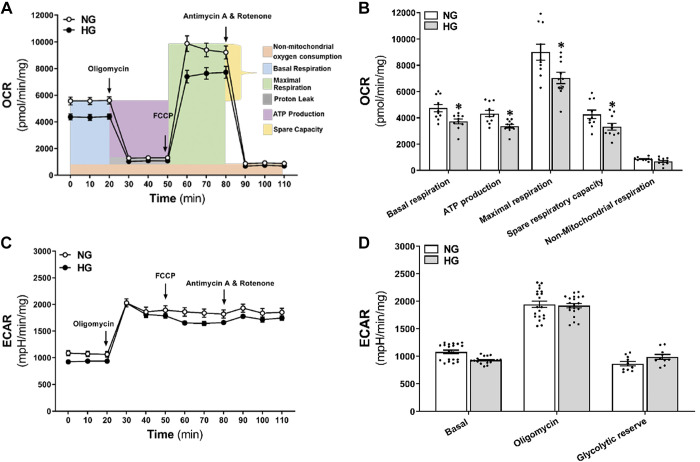

Comparison of Mitochondrial Respiration and ATP Production in HG- and NG-Treated HBMVPs

We compared changes in OCR for mitochondrial respiration and ECAR for glycolysis in NG- and HG-treated HBMVPs using Seahorse XFe 24 analyzer. As presented in Fig. 3, A and B, mitochondrial basal respiration (3,718.2 ± 185.9 vs. 4,741.6 ± 284.5 pmol/min/mg) and ATP production (3,372.7 ± 144.5 vs. 4,333.1 ± 251.4 pmol/min/mg) were significantly reduced in HG-treated than NG-treated cells. Similarly, HG-treated HBMVPs exhibited lower maximal respiration (7,038.0 ± 429.0 vs. 9,005.2 ± 610.2 pmol/min/mg) and spare respiratory capacity (3,319.8 ± 265.2 vs. 4,263.7 ± 328.3 pmol/min/mg) than NG-treated cells. However, there was no change in basal ECAR, oligomycin-induced ECAR, and the glycolytic reserve in HG-treated HBMVPs (Fig. 3, C and D).

Figure 3.

Comparison of mitochondrial respiration and ATP production in HG- and NG-treated HBMVPs. A: Seahorse XF Cell OCR Mito Stress Test profiles in HG- and NG-treated HBMVPs. OCR was measured before and after the application of the following inhibitors: oligomycin (1 µM, inhibitor of complex V), FCCP (2 µM, uncoupling agent collapsing the inner membrane gradient), antimycin A (0.5 µM, inhibitor of complex III), and rotenone (0.5 µM, inhibitor of complex I) were added at the indicated points. B: quantitative analysis of OCR in HG- and NG-treated HBMVPs. C: Seahorse XF Cell ECAR in HG- and NG-treated HBMVPs. D: quantitative analysis of basal ECAR, oligomycin-induced ECAR, and the glycolytic reserve in HG- and NG-treated HBMVPs. Experiments were repeated three to four times in triplicates. *P < 0.05 from the corresponding values in HG- versus NG-treated HBMVPs. ECAR, extracellular acidification rate; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone; HBMVPs, human brain microvascular pericytes; HG, high glucose; NG, normal glucose; OCR, oxygen consumption rate.

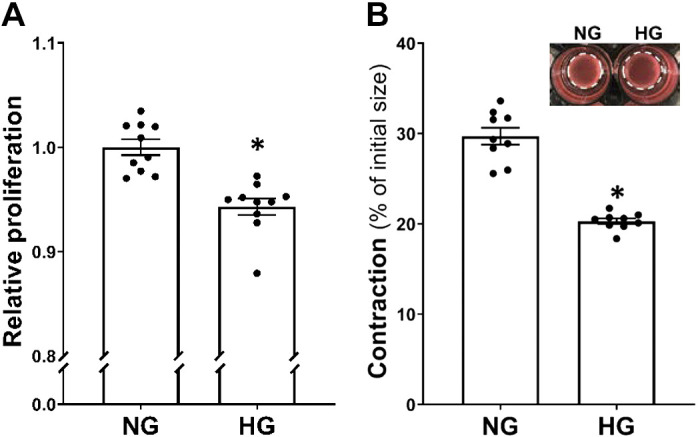

Comparison of Cell Proliferation and Contractile Capability in HG- and NG-Treated HBMVPs

As presented in Fig. 4A, cell proliferation, detected by the MTS assay, was 6% lower in HG- than NG-treated HBMVPs. HG-treated HBMVPs developed a much slower contraction after stimulation, and the gel area size (Fig. 4B) was shrunk by 20% (0.39 ± 0.01 cm2) in HG-treated cells compared with 30% (0.56 ± 0.02 cm2) in NG-treated pericytes.

Figure 4.

Comparison of cell proliferation and contractile capability in HG- and NG-treated HBMVPs A: comparison of relative proliferation in HG- vs. NG-treated HBMVPs using the MTS assay. B: comparison of the contractile capability of HG- vs. NG-treated HBMVPs using the cell contraction assay kit. The inserts are representative images, and the white dotted circles represent the gel area after stimulation. Experiments were repeated three to four times in triplicates *P < 0.05 the corresponding values in HG- versus NG-treated HBMVPs. HBMVPs, human brain microvascular pericytes; HG, high glucose; NG, normal glucose.

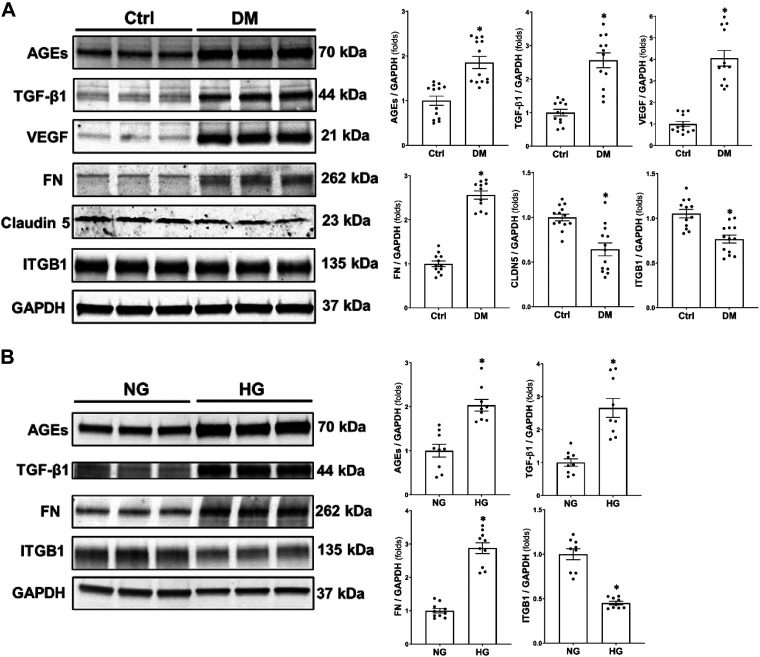

Comparison of the Expression of AGEs, TGF-β1, VEGF, FN, CLDN5, and ITGB1 in the Brain of DM versus Control Rats and HG- and NG-Treated HBMVPs

As presented in Fig. 5A, the expression of AGEs (1.71 ± 0.12 vs. 0.90 ± 0.09), TGF-β1 (1.37 ± 0.10 vs. 0.47 ± 0.04), VEGF (2.11 ± 0.18 vs. 0.51 ± 0.06), and FN (0.78 ± 0.03 vs. 0.30 ± 0.02) protein was higher by two-, three-, four-, and threefold, respectively, in the brains of DM rats than age-matched non-DM rats. In contrast, the expression of CLDN5 (0.60 ± 0.07 vs. 0.89 ± 0.06) and ITGB1 (0.92 ± 0.06 vs. 1.33 ± 0.06) was lower by 0.6- and 0.7-fold, respectively, in DM than SD brains. Similarly, HG-treated pericytes exhibited higher expression of AGEs (3.28 ± 0.21 vs. 1.55 ± 0.22), TGF-β1 (1.21 ± 0.17 vs. 0.43 ± 0.05), and FN (1.85 ± 0.11 vs. 0.64 ± 0.04) by two-, three-, and threefold, respectively, and lower expression of ITGB1 (1.03 ± 0.04 vs. 2.23 ± 0.14) by 0.5-fold than NG-treated HBMVPs (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the expression of AGEs, TGF-β1, VEGF, FN, CLDN5, and ITGB1 in the brain of DM vs. Ctrl rats and HG- and NG-treated HBMVPs. A: representative images (left) and quantitation (right) of AGEs, TGF-β1, VEGF, FN, CLDN5, and ITGB1 expression by Western blots in the brain of DM and Ctrl rats. N = 4 rats in each group and experiments were repeated three times. B: representative images (left) and quantitation (right) of AGEs, TGF-β1, FN, and ITGB1 expression by Western blot in HG- and NG-treated HBMVPs. Experiments using HBMVPs were repeated three times in triplicates. *P < 0.05 the corresponding value in DM versus non-DM rats or HG- versus NG-treated HBMVPs. AGEs, advanced glycation end products; CLDN5, claudin 5; Ctrl, control; DM, diabetes mellitus; FN, fibronectin; HBMVPs, human brain microvascular pericytes; HG, high glucose; ITGB1, integrin β1; NG, normal glucose; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-β1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

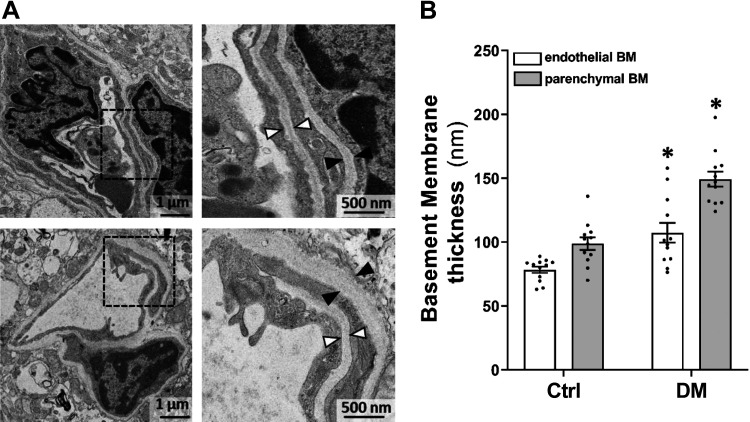

Comparison of Cerebral Vascular Basement Membranes Thickness in DM and Non-DM Rats

Both endothelial and parenchymal basement membranes on cortical capillaries of DM rats were compared with age-matched non-DM rats by TEM. Figure 6 demonstrates that cortical capillary endothelial basement membranes were thickened in DM than control rats (105.24 ± 7.82 vs. 78.29 ± 2.52 nm). Similarly, parenchymal basement membranes on the capillaries of the DM cortex were thickened compared with non-DM rats (154.63 ± 5.99 vs. 98.73 ± 4.94 nm).

Figure 6.

Comparison of cerebral vascular BM thickness in DM and non-DM rats. Representative images (A) and quantitation (B) of the thickness of the basement BM in DM and Ctrl rats. Black triangles denote the area of endothelial BM, and white triangles point to the area of parenchymal BM in the cerebral cortical capillary of non-DM and DM rats. Magnification: ×25,400 (left); ×68,580 (right). 12 vessels/6 rats per group. *P < 0.05 from the corresponding values in diabetic versus nondiabetic rats. BM, basement membrane; Ctrl, control; DM, diabetes mellitus.

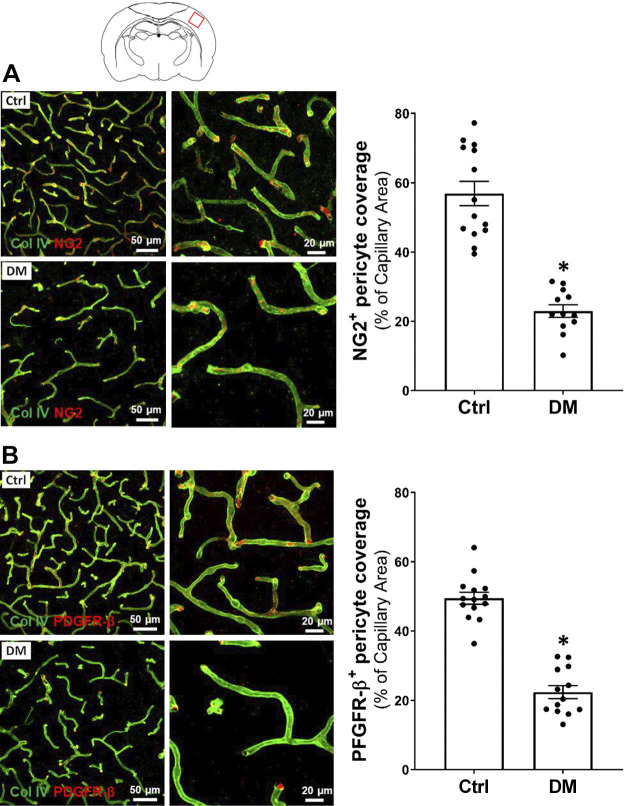

Comparison of Pericytes Coverage on Cerebral Cortical Capillaries of DM and Non-DM Rats

A comparison of pericyte coverage on cerebral capillaries in the cortex of DM and non-DM rats is presented in Fig. 7. We found there was significantly reduced NG2- (Fig. 7A) and PDGFR-β-positive (Fig. 7B) pericyte coverage (24.26 ± 1.83 vs. 56.90 ± 3.53% and 23.30 ± 1.84 vs. 49.45 ± 1.75%, respectively) on the capillaries of DM rats compared with the control group.

Figure 7.

Comparison of pericytes coverage on cerebral cortical capillaries of DM vs. non-DM rats. A: representative images (left) and quantitation (right) of pericyte coverage on the capillaries by comparison of area percentage of NG2 (red) on Col IV (green)-stained capillaries in DM versus the Ctrl rats. B: representative images (left) and quantitation (right) of pericyte coverage on the capillaries by comparison of area percentage of PDGFR-β (red) on Col IV (green)-stained microvessels in DM versus age-matched Ctrl rats. Four rats of each group were studied, and three to four sections were obtained per animal for quantification. *P < 0.05 from the corresponding values in diabetic versus age-matched non-diabetic rats. Col IV, collagen IV; Ctrl, control; DM, diabetes mellitus; NG2, neuro-glial antigen 2; PDGFR-β, platelet-derived growth factor receptor β.

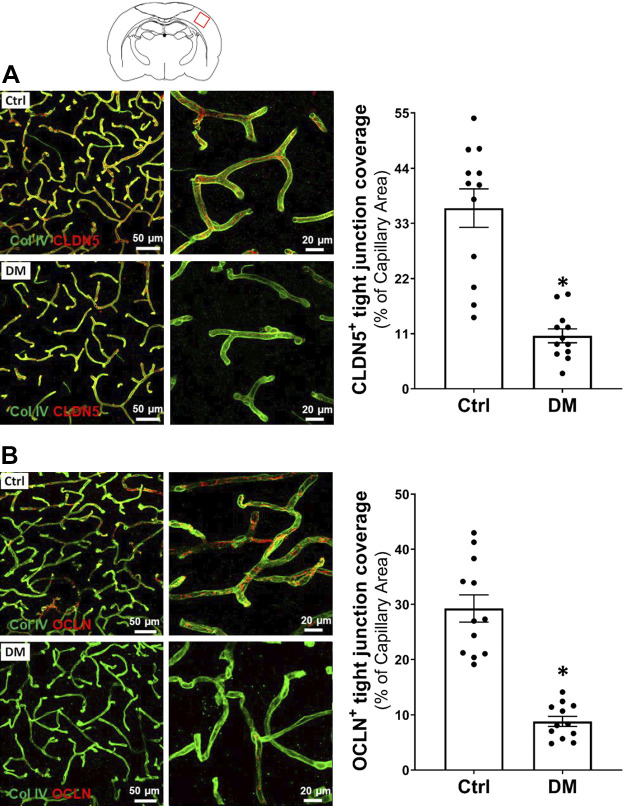

Comparison of Tight Junction Coverage on Cerebral Cortical Capillaries of DM and Non-DM Rats

A comparison of endothelial tight junction coverage on cerebral capillaries in the cortex of DM and non-DM rats is presented in Fig. 8. We found there was significantly reduced CLDN5- (Fig. 8A; Supplemental Videos S1 and S2; Supplemental materials are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12904076.v3 and https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12904082.v3) and OCLN-positive (Fig. 8B) tight junction coverage (10.74 ± 1.38% vs. 36.05 ± 3.83% and 7.92 ± 0.91% vs. 29.26 ± 2.47%, respectively) on the capillaries of DM rats compared with the control group.

Figure 8.

Comparison of tight junction coverage on cerebral cortical capillaries of DM and non-DM rats. A: representative images (left) and quantitation (right) of tight junction coverage on the capillaries by comparison of area percentage of CLDN5 (red) on Col IV (green)-stained capillaries in DM versus the Ctrl rats. B: representative images (left) and quantitation (right) of tight junction coverage on the capillaries by comparison of area percentage of OCLN (red) on Col IV (green)-stained microvessels in DM versus the age-matched control rats. Four rats of each group were studied, and three to four sections were obtained per animal for quantification. *P < 0.05 from the corresponding values in diabetic versus age-matched nondiabetic rats. CLDN5, claudin 5; Col IV, collagen IV; Ctrl, control; DM, diabetes mellitus; OCLN, occludin.

DISCUSSION

DM is one of the leading cardiovascular factors contributing to AD (55–58). DM and AD are both associated with cerebral vascular dysfunction. However, the linking mechanisms have not been fully understood. We previously reported that old T2DN DM rats exhibited BBB leakage, neurodegeneration, and cognitive impairments (40). The present study provides evidence that BBB leakage in old DM rats is due, at least in part to 1) loss of contractile capability of pericytes that express α-SMA and are localized on the wall of PAs in DM environment. This change in phenotype maybe related to enhanced ROS and mitochondrial superoxide production, diminished mitochondria respiration, and reduced ATP formation in DM pericytes. 2) Pericytes that lie on the cortical capillaries exhibit increased release of TGF-β1, VEGF, and FN, and reduced expression of CLDN5 and ITGB1 after exposure to DM-induced AGEs. Consistent with previous reports (25, 59, 60), the differential expression of these proteins in the present study was associated with basement membrane thickening, pericyte detachment from the basement membrane, and loss of endothelial tight junctions in the old DM rats.

The components of the BBB at the capillary level within the neurovascular unit consist of endothelial cells, astrocyte end-feet, pericytes, and basement membrane. The BBB is freely permeable to water and allows the diffusion of small polar (MW < 400 Da) and hydrophobic molecules (61), as well as selective transport of large molecules via specific transport proteins. However, it restricts pathogens and large and hydrophilic molecules crossing this barrier. There is significant evidence that BBB leakage is enhanced in DM and AD animal models and patients (11, 15, 62). BBB leakage results in neurodegeneration, a pathological hallmark of AD, which can be induced by neurovascular uncoupling; oxidative stress; alteration of BBB transport of glucose, insulin, choline, and other amino acids; a reduction in the clearance of toxic proteins (such as amyloid-β); infiltration of circulating inflammatory factors; glial activation; and alterations of cerebral capillary density (63–68). BBB breakdown could also induce barotrauma by increased transmission of pressure to the vulnerable capillaries secondary to incomplete CBF autoregulation (69–75). Enhanced BBB permeability is associated with the disruption of tight junction between the ECs of brain capillaries and pericyte loss and/or damage at the capillary level (14, 76, 77). However, difficulty in detecting BBB function in the heterogeneous brain microvascular beds and dissecting out the impact of hyperglycemia in vivo and ex vivo has led to considerable controversy concerning whether BBB leakage in DM is caused by hyperglycemia (11, 13, 15, 16, 62). Pericytes have several subtypes, but no specific pericyte markers have been identified to date. Pericytes share the expression of PDGFR-β with VSMCs, neurons, and neural progenitors (78); NG2 with VSMCs, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, and neuronal progenitors (79); α-SMA with myofibroblasts, cardiomyocytes, and VSMCs (30); DES with smooth muscle cells in the vasculature, skeletal muscle, heart, and podocytes (80, 81); CD13 with VSMCs and ECs (21, 82). Since there is no clear-cut single marker to distinguish pericyte subtypes, we used multiple markers correlating localization and morphology for the identification of pericytes in the present study.

We recently demonstrated that old (18-mo) nonobese T2DN rats exhibited massive cortical and hippocampal BBB leakage following acute elevations in pressure and cognitive deficits (40). These changes were reversed after normalization of blood glucose levels with a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor without altering blood pressure or protein excretion (83–85). These results indicate that hyperglycemia plays an essential role in cerebral vascular and cognitive dysfunction in DM. We also found that old DM rats exhibited neurodegeneration and reduced tight junction and pericyte coverage on CA3 hippocampal capillaries in association with impaired myogenic response and autoregulation of CBF (40). Interestedly, the impaired CBF autoregulation was observed in both surface and deep cortices, and diminished myogenic reactivity to pressures was exhibited in both the MCAs and PAs in this DM rat model. Indeed, the impaired myogenic response of the MCA in DM rats appeared to be related to an imbalanced mitochondrial dynamics and the depletion of ATP in VSMCs (41). In the present study, we now have demonstrated that the production of ROS is also enhanced in the contractile pericytes treated with HG, which express α-SMA and typically found lining the wall of PAs upstream of cerebral capillaries. More specifically, the enhanced ROS production in HG-treated pericytes was mainly derived from mitochondrial. Additionally, our results that basal respiration, ATP production, maximal respiration, and spare respiratory capacity were decreased in HG-treated HBMVPs suggest mitochondrial dysfunction. The latter is also evidenced by there was no significant difference in ECAR, which reflects the rate of glycolysis, between NG- and HG-treated pericytes. These results are consistent with other studies using HG-treated retinal pericytes (86) and our recent studies using HG-treated primary cerebral VSMCs (41). HG enhances the production of mitochondrial ROS and promotes a generalized dysfunction of ECs, pericytes, VSMCs, and other cell types in DM (41, 87–90). The enhanced ROS and reduced ATP production in HG-treated HBMVPs were associated with diminished cell proliferation and contractile capability that likely contributes to the impaired myogenic response of PAs and poor CBF autoregulation in the deep cortex, as well as the reduced pericyte coverage in the present and previous studies (40).

Structurally, BBB integrity is maintained by a tightly sealed monolayer of ECs and pericytes, which are embedded in the cerebral capillary basement membrane and wrap around the endothelium. Cerebral capillary pericytes exhibit much lower α-SMA expression. Pericytes crosstalk with ECs, and the basement membrane of capillaries is critical for maintaining BBB function and cerebrovascular stability. Although little is known about whether hyperglycemia damages pericyte-endothelia-basement membrane crosstalk in the old DM brain, previous reports indicated that hyperglycemia-induced high levels of AGEs promoted vascular dysfunction and disrupted blood-nerve barrier in DM patients and HG-treated cerebral ECs, pericytes, and astrocytes (60, 91). It also has been observed that the basement membranes of cerebral capillaries were thickening in both AD and DM patients and DM animal models (92–94). AGEs increased HG-treated pericyte-released TGF-β1, resulting in more production of FN in an autocrine manner (15). AGEs also evoked ECs and pericytes-released VEGF, which feeds back to the ECs to down-regulate tight junction protein CLDN5 expression (60, 95). The present results are consistent with these previous findings demonstrating that the enhanced expression of AGEs, TGF-β1, VEGF, FN, and reduced expression of CLDN5 and ITGB1 were in association with the thickening of cortical capillary basement membranes in DM rats.

The vascular basement membrane is a complex extracellular matrix sandwiched between the ECs, pericytes, and astrocytes, which plays an essential role in barrier function (94). In the brain, pericytes separate the basement membrane into endothelial and parenchymal basement membranes. There are other proteins contributing to the formation and maintenance of the basement membrane in addition to the four major proteins: laminin, Col IV, nidogen, and perlecan (94, 96). FN is an insoluble extracellular matrix protein that binds to integrins and other extracellular matrix proteins. TGF-β1 and VEGF are soluble heparin-binding factors in the cerebral vascular basement membrane; both of them reduce CLDN5 expression. Additionally, pericyte ITGB1 is correlated to the expression of CLDN5, which anchors pericytes to the basement membrane (94). These results in terms of hyperglycemia-induced changes in protein expression by Western blots in DM pericytes were validated by immunostaining that CLDN5- and OCLN-positive tight junction coverage and NG2- and PDGFR-β-positive pericyte coverage and in cortical capillaries were reduced in DM rats.

In summary, this study demonstrates for the first time that increased BBB permeability in old DM rats is associated with reduced α-SMA-positive pericyte contractile capability, which may contribute to the impaired myogenic response of PAs and CBF autoregulation in the deep cortex found in our earlier studies (40). We also demonstrated that the alteration in AGEs-induced signaling transduction in cortical capillary pericytes exposed to HG is associated with the disruption of BBB integrity by basement membrane thickening, pericyte detachment, and tight junction damage. However, a limitation in the present study is that we were unable to provide direct evidence to separate the subtype of pericytes. Nevertheless, our findings provide a novel insight into the role of pericytes in the heterogeneous brain microvasculature and the potential underlying mechanisms by which hyperglycemia-induced damage to pericyte function that might contribute to DM-related dementia.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AG050049, AG057842, P20GM104357, and HL138685 and American Heart Association Grants 16GRNT31200036 and 20PRE35210043.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.L. and F.F. conceived and designed research; Y.L., H.Z., S.W., Y.G., X.F., B.Z., and W.G. performed experiments; Y.L., F.F., H.Z., and S.W. analyzed data; Y.L., R.J.R., F.F., H.Z., S.W., H.Y., and Z.C. interpreted results of experiments; Y.L. and F.F. prepared figures; Y.L. and F.F. drafted manuscript; Y.L., R.J.R., F.F., and H.Y. edited and revised manuscript; Y.L., R.J.R., F.F., H.Z., S.W., Y.G., X.F., B.Z., W.G., H.Y., and Z.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Paul J. May in the Department of Neurobiology and Anatomical Sciences at the University of Mississippi Medical Center for his consulting on the interpretation of TEM.

REFERENCES

- 1.de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Alzheimer's disease is type 3 diabetes-evidence reviewed. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2: 1101–1113, 2008. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaugler J, James B, Johnson T, Marin A, Weuve J, As A. Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 15: 321–387, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.2020 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 16: 391–460, 2020. [ 10.1002/alz.12068] [32157811] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayeda ER, Whitmer RA, Yaffe K. Diabetes and cognition. Clin Geriatr Med 31: 101–115, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2014.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med 368: 1326–1334, 2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csipo T, Lipecz A, Fulop GA, Hand RA, Ngo BN, Dzialendzik M, Tarantini S, Balasubramanian P, Kiss T, Yabluchanska V, Silva-Palacios F, Courtney DL, Dasari TW, Sorond F, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Yabluchanskiy A. Age-related decline in peripheral vascular health predicts cognitive impairment. Geroscience 41: 125–136, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11357-019-00063-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardigan T, Ward R, Ergul A. Cerebrovascular complications of diabetes: focus on cognitive dysfunction. Clin Sci 130: 1807–1822, 2016. doi: 10.1042/CS20160397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raghavan S, Vassy JL, Ho Y-L, Song RJ, Gagnon DR, Cho K, Wilson PWF, Phillips LS. Diabetes mellitus-related all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a national cohort of adults. J Am Heart Assoc 8: e011295–e011295, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ungvari Z, Tarantini S, Donato AJ, Galvan V, Csiszar A. Mechanisms of vascular aging. Circ Res 123: 849–867, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou H, Zhang X, Lu J. Progress on diabetic cerebrovascular diseases. Bosn J of Basic Med Sci 14: 185–190, 2014. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2014.4.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawkins BT, Lundeen TF, Norwood KM, Brooks HL, Egleton RD. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability and altered tight junctions in experimental diabetes in the rat: contribution of hyperglycaemia and matrix metalloproteinases. Diabetologia 50: 202–211, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0485-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber JD, VanGilder RL, Houser KA. Streptozotocin-induced diabetes progressively increases blood-brain barrier permeability in specific brain regions in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2660–H2668, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00489.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janelidze S, Hertze J, Nagga K, Nilsson K, Nilsson C, Swedish Bio FSG, Wennstrom M, van Westen D, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Hansson O. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability is associated with dementia and diabetes but not amyloid pathology or APOE genotype. Neurobiol Aging 51: 104–112, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salameh TS, Shah GN, Price TO, Hayden MR, Banks WA. Blood-brain barrier disruption and neurovascular unit dysfunction in diabetic mice: protection with the mitochondrial carbonic anhydrase inhibitor topiramate. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 359: 452–459, 2016. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.237057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirunpattarasilp C, Attwell D, Freitas F. The role of pericytes in brain disorders: from the periphery to the brain. J Neurochem 150: 648–665, 2019. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mae MA, Li T, Bertuzzi G, Raschperger E, Vanlandewijck M, He L, Nahar K, Dalheim A, Hofmann JJ, Lavina B, Keller A, Betsholtz C, Genove G. Prolonged systemic hyperglycemia does not cause pericyte loss and permeability at the mouse blood-brain barrier. Sci Rep 8: 17462, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35576-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allt G, Lawrenson JG. Pericytes: cell biology and pathology. Cells Tissues Organs 169: 1–11, 2001. doi: 10.1159/000047855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armulik A, Genove G, Betsholtz C. Pericytes: developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev Cell 21: 193–215, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweeney MD, Ayyadurai S, Zlokovic BV. Pericytes of the neurovascular unit: key functions and signaling pathways. Nat Neurosci 19: 771–783, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nn.4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res 97: 512–523, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000182903.16652.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armulik A, Genove G, Mae M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, He L, Norlin J, Lindblom P, Strittmatter K, Johansson BR, Betsholtz C. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature 468: 557–561, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nature09522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandopadhyay R, Orte C, Lawrenson JG, Reid AR, De Silva S, Allt G. Contractile proteins in pericytes at the blood-brain and blood-retinal barriers. J Neurocytol 30: 35–44, 2001. doi: 10.1023/A:1011965307612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uemura MT, Maki T, Ihara M, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Brain microvascular pericytes in vascular cognitive impairment and dementia. Front Aging Neurosci 12: 80, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown LS, Foster CG, Courtney JM, King NE, Howells DW, Sutherland BA. Pericytes and neurovascular function in the healthy and diseased brain. Front Cell Neurosci 13: 282, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartmann DA, Underly RG, Grant RI, Watson AN, Lindner V, Shih AY. Pericyte structure and distribution in the cerebral cortex revealed by high-resolution imaging of transgenic mice. Neurophoton 2: 041402, 2015. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.2.4.041402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan-Ling T, Page MP, Gardiner T, Baxter L, Rosinova E, Hughes S. Desmin ensheathment ratio as an indicator of vessel stability: evidence in normal development and in retinopathy of prematurity. Am J Pathol 165: 1301–1313, 2004. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63389-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Federico A, Di Donato I, Bianchi S, Di Palma C, Taglia I, Dotti MT. Hereditary cerebral small vessel diseases: a review. J Neurol Sci 322: 25–30, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hellstrom M, Kalen M, Lindahl P, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development 126: 3047–3055, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rucker HK, Wynder HJ, Thomas WE. Cellular mechanisms of CNS pericytes. Brain research bulletin 51: 363–369, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(99)00260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant RI, Hartmann DA, Underly RG, Berthiaume AA, Bhat NR, Shih AY. Organizational hierarchy and structural diversity of microvascular pericytes in adult mouse cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 39: 411–425, 2017. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17732229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall CN, Reynell C, Gesslein B, Hamilton NB, Mishra A, Sutherland BA, O'Farrell FM, Buchan AM, Lauritzen M, Attwell D. Capillary pericytes regulate cerebral blood flow in health and disease. Nature 508: 55–60, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nature13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nehls V, Drenckhahn D. Heterogeneity of microvascular pericytes for smooth muscle type alpha-actin. J Cell Biol 113: 147–154, 1991. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peppiatt CM, Howarth C, Mobbs P, Attwell D. Bidirectional control of CNS capillary diameter by pericytes. Nature 443: 700–704, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nature05193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S, Zhang H, Liu Y, Li L, Guo Y, Jiao F, Fang X, Jefferson Jr Li M, Gao W, Gonzalez-Fernandez E, Maranon RO, Pabbidi MR, Liu R, Alexander BT, Roman RJ, Fan F. Sex differences in the structure and function of rat middle cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 318: H1219–H1232, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00722.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammes HP, Lin J, Renner O, Shani M, Lundqvist A, Betsholtz C, Brownlee M, Deutsch U. Pericytes and the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes 51: 3107–3112, 2002. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfister F, Feng Y, Vom Hagen F, Hoffmann S, Molema G, Hillebrands JL, Shani M, Deutsch U, Hp H. Pericyte migration: a novel mechanism of pericyte loss in experimental diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes 57: 2495–2502, 2008. doi: 10.2337/db08-0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung NY, Han JC, Ong YT, Cheung CY, Chen CP, Wong TY, Kim HJ, Kim YJ, Lee J, Lee JS, Jang YK, Kee C, Lee KH, Kim EJ, Seo SW, Na DL. Retinal microvasculature changes in amyloid-negative subcortical vascular cognitive impairment compared to amyloid-positive Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Sci 396: 94–101, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2018.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nikolakopoulou AM, Montagne A, Kisler K, Dai Z, Wang Y, Huuskonen MT, Sagare AP, Lazic D, Sweeney MD, Kong P, Wang M, Owens NC, Lawson EJ, Xie X, Zhao Z, Zlokovic BV. Pericyte loss leads to circulatory failure and pleiotrophin depletion causing neuron loss. Nat Neurosci 22: 1089–1098, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0434-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sagare AP, Bell RD, Zhao Z, Ma Q, Winkler EA, Ramanathan A, Zlokovic BV. Pericyte loss influences Alzheimer-like neurodegeneration in mice. Nat Commun 4: 2932, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40.Wang S, Lv W, Zhang H, Liu Y, Li L, Jefferson JR, Guo Y, Li M, Gao W, Fang X, Paul IA, Rajkowska G, Shaffery JP, Mosley TH, Hu X, Liu R, Wang Y, Yu H, Roman RJ, Fan F. Aging exacerbates impairments of cerebral blood flow autoregulation and cognition in diabetic rats. Geroscience 42: 1387–1410, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11357-020-00233-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo Y, Wang S, Liu Y, Fan L, Booz GW, Roman RJ, Chen Z, Fan F. Accelerated cerebral vascular injury in diabetes is associated with vascular smooth muscle cell dysfunction. Geroscience 42: 547–561, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11357-020-00179-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fan F, Pabbidi MR, Ge Y, Li L, Wang S, Mims PN, Roman RJ. Knockdown of Add3 impairs the myogenic response of renal afferent arterioles and middle cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 312: F971–F981, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00529.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang H, Zhang C, Liu Y, Gao W, Wang S, Fang X, Guo Y, Li M, Liu R, Roman RJ, Sun P, Fan F. Influence of dual-specificity protein phosphatase 5 on mechanical properties of rat cerebral and renal arterioles. Physiol Rep 8: e14345, 2020. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson KM, Janes MS, Beckman JS. The selective detection of mitochondrial superoxide by live cell imaging. Nat Protoc 3: 941–947, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sure VN, Sakamuri S, Sperling JA, Evans WR, Merdzo I, Mostany R, Murfee WL, Busija DW, Katakam PVG. A novel high-throughput assay for respiration in isolated brain microvessels reveals impaired mitochondrial function in the aged mice. Geroscience 40: 365–375, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11357-018-0037-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee H, Abe Y, Lee I, Shrivastav S, Crusan AP, Huttemann M, Hopfer U, Felder RA, Asico LD, Armando I, Jose PA, Kopp JB. Increased mitochondrial activity in renal proximal tubule cells from young spontaneously hypertensive rats. Kidney Int 85: 561–569, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ge D, Meng N, Su L, Zhang Y, Zhang SL, Miao JY, Zhao J. Human vascular endothelial cells reduce sphingosylphosphorylcholine-induced smooth muscle cell contraction in co-culture system through integrin β4 and Fyn. Acta Pharmacol Sin 33: 57–65, 2012. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakota Y, Ozawa Y, Yamashita H, Tanaka H, Inagaki N. Collagen gel contraction assay using human bronchial smooth muscle cells and its application for evaluation of inhibitory effect of formoterol. Biol Pharm Bull 37: 1014–1020, 2014. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b13-00996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gonzalez-Fernandez E, Staursky D, Lucas K, Nguyen BV, Li M, Liu Y, Washington C, Coolen LM, Fan F, Roman RJ. 20-HETE enzymes and receptors in the neurovascular unit: implications in cerebrovascular disease. Front Neurol 11: 983, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao Z, Daquinag AC, Su F, Snyder B, Kolonin MG. PDGFRα/PDGFRβ signaling balance modulates progenitor cell differentiation into white and beige adipocytes. Development 145: dev155861, 2018. doi: 10.1242/dev.155861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nefla M, Sudre L, Denat G, Priam S, Andre-Leroux G, Berenbaum F, Jacques C. The pro-inflammatory cytokine 14-3-3ε is a ligand of CD13 in cartilage. J Cell Sci 128: 3250–3262, 2015. doi: 10.1242/jcs.169573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Korbo L, Pakkenberg B, Ladefoged O, Gundersen HJ, Arlien-Soborg P, Pakkenberg H. An efficient method for estimating the total number of neurons in rat brain cortex. J Neurosci Methods 31: 93–100, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cipolla MJ, Chan SL, Sweet J, Tavares MJ, Gokina N, Brayden JE. Postischemic reperfusion causes smooth muscle calcium sensitization and vasoconstriction of parenchymal arterioles. Stroke 45: 2425–2430, 2014. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pires PW, Dabertrand F, Earley S. Isolation and cannulation of cerebral parenchymal arterioles. J Vis Exp: 53835, 2016. doi: 10.3791/53835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Infante-Garcia C, Ramos-Rodriguez JJ, Galindo-Gonzalez L, Garcia-Allosa M. . Long-term central pathology and cognitive impairment are exacerbated in a mixed model of Alzheimer's disease and type 2 diabetes. Psychoneuroendocrinology 65: 15–25, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jayaraj RL, Azimullah S, Beiram R. Diabetes as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease in the Middle East and its shared pathological mediators. Saudi J Biol Sci 27: 736–750, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Geda YE, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, Baertlein L, Boeve BF, Tangalos EG, Ivnik RJ, Mielke MM, Petersen RC. Association of diabetes with amnestic and nonamnestic mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement 10: 18–26, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samaras K, Lutgers HL, Kochan NA, Crawford JD, Campbell LV, Wen W, Slavin MJ, Baune BT, Lipnicki DM, Brodaty H, Trollor JN, Sachdev PS. The impact of glucose disorders on cognition and brain volumes in the elderly: the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study. Age (Dordr) 36: 977–993, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9613-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roy S, Nasser S, Yee M, Graves DT, Roy S. A long-term siRNA strategy regulates fibronectin overexpression and improves vascular lesions in retinas of diabetic rats. Mol Vis 17: 3166–3174, 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shimizu F, Sano Y, Tominaga O, Maeda T, Abe MA, Kanda T. Advanced glycation end-products disrupt the blood-brain barrier by stimulating the release of transforming growth factor-beta by pericytes and vascular endothelial growth factor and matrix metalloproteinase-2 by endothelial cells in vitro. Neurobiol Aging 34: 1902–1912, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pardridge WM. Drug transport across the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32: 1959–1972, 2012. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Starr JM, Wardlaw J, Ferguson K, MacLullich A, Deary IJ, Marshall I. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability in type II diabetes demonstrated by gadolinium magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74: 70–76, 2003. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cukierman-Yaffe T, Gerstein HC, Williamson JD, Lazar RM, Lovato L, Miller ME, Coker LH, Murray A, Sullivan MD, Marcovina SM, Launer LJ; Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes-Memory in Diabetes-Memory in Diabetes (ACCORD-MIND) Trial Investigators . Relationship between baseline glycemic control and cognitive function in individuals with type 2 diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors: the action to control cardiovascular risk in diabetes-memory in diabetes (ACCORD-MIND) trial. Diabetes Care 32: 221–226, 2009. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deak F, Freeman WM, Ungvari Z, Csiszar A, Sonntag WE. Recent developments in understanding brain aging: implications for Alzheimer's disease and vascular cognitive impairment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 71: 13–20, 2016. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fulop GA, Ahire C, Csipo T, Tarantini S, Kiss T, Balasubramanian P, Yabluchanskiy A, Farkas E, Toth A, Nyúl-Tóth Á, Toth P, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Cerebral venous congestion promotes blood-brain barrier disruption and neuroinflammation, impairing cognitive function in mice. Geroscience 41: 575–589, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11357-019-00110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kiss T, Nyul-Toth A, Balasubramanian P, Tarantini S, Ahire C, Yabluchanskiy A, Csipo T, Farkas E, Wren JD, Garman L, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) supplementation promotes neurovascular rejuvenation in aged mice: transcriptional footprint of SIRT1 activation, mitochondrial protection, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic effects. Geroscience 42: 527–546, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11357-020-00165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meneilly GS, Tessier DM. Diabetes, dementia and hypoglycemia. Canadian J Diabetes 40: 73–76, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sommerfield AJ, Deary IJ, Frier BM. Acute hyperglycemia alters mood state and impairs cognitive performance in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27: 2335–2340, 2004. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Daneman R, Prat A. The blood-brain barrier. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7: a020412, 2015. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fan F, Geurts AM, Murphy SR, Pabbidi MR, Jacob HJ, Roman RJ. Impaired myogenic response and autoregulation of cerebral blood flow is rescued in CYP4A1 transgenic Dahl salt-sensitive rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 308: R379–R390, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00256.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fan F, Simino J, Auchus A, Knopman D, Boerwinkle E, Fornage M, Mosley T, Roman R. Functional variants in CYP4A11 and CYP4F2 are associated with cognitive impairment and related dementia endophenotypes in the elderly. In: The 16th International Winter Eicosanoid Conference. Baltimore, 2016, p. CV5. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nation DA, Sweeney MD, Montagne A, Sagare AP, D'Orazio LM, Pachicano M, Sepehrband F, Nelson AR, Buennagel DP, Harrington MG, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Ringman JM, Schneider LS, Morris JC, Chui HC, Law M, Toga AW, Zlokovic BV. Blood-brain barrier breakdown is an early biomarker of human cognitive dysfunction. Nat Med 25: 270–276, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0297-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shekhar S, Wang S, Mims PN, Gonzalez-Fernandez E, Zhang C, He X, Liu CY, Lv W, Wang Y, Huang J, Fan F. Impaired cerebral autoregulation-a common neurovascular pathway in diabetes may play a critical role in diabetes-related Alzheimer's disease. Curr Res Diabetes Obes J 2: 555587, 2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sweeney MD, Zhao Z, Montagne A, Nelson AR, Zlokovic BV. Blood-brain barrier: from physiology to disease and back. Physiol Rev 99: 21–78, 2019. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00050.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Toth P, Tarantini S, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Functional vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: mechanisms and consequences of cerebral autoregulatory dysfunction, endothelial impairment, and neurovascular uncoupling in aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 312: H1–H20, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00581.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prasad S, Sajja RK, Naik P, Cucullo L. Diabetes mellitus and blood-brain barrier dysfunction: an overview. J Pharmacovigil 2: 125, 2014. doi: 10.4172/2329-6887.1000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tucsek Z, Toth P, Tarantini S, Sosnowska D, Gautam T, Warrington JP, Giles CB, Wren JD, Koller A, Ballabh P, Sonntag WE, Ungvari Z, Csiszar A. Aging exacerbates obesity-induced cerebromicrovascular rarefaction, neurovascular uncoupling, and cognitive decline in mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69: 1339–1352, 2014. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bhowmick S, D'Mello V, Caruso D, Wallerstein A, Abdul-Muneer PM. Impairment of pericyte-endothelium crosstalk leads to blood-brain barrier dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 317: 260–270, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stallcup WB. The NG2 proteoglycan in pericyte biology. Adv Exp Med Biol 1109: 5–19, 2018. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-02601-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bell RD, Winkler EA, Sagare AP, Singh I, LaRue B, Deane R, Zlokovic BV. Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron 68: 409–427, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jung B, Arnold TD, Raschperger E, Gaengel K, Betsholtz C. Visualization of vascular mural cells in developing brain using genetically labeled transgenic reporter mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 38: 456–468, 2018. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17697720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Harrell CR, Simovic Markovic B, Fellabaum C, Arsenijevic A, Djonov V, Volarevic V. Molecular mechanisms underlying therapeutic potential of pericytes. J Biomed Sci 25: 21–21, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12929-018-0423-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kojima N, Williams JM, Slaughter TN, Kato S, Takahashi T, Miyata N, Roman RJ. Renoprotective effects of combined SGLT2 and ACE inhibitor therapy in diabetic Dahl S rats. Physiol Rep 3: e12436, 2015. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kojima N, Williams JM, Takahashi T, Miyata N, Roman RJ. Effects of a new SGLT2 inhibitor, luseogliflozin, on diabetic nephropathy in T2DN rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 345: 464–472, 2013. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.203869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang S, Fan F. Oral antihyperglycemic therapy with a SGLT2 inhibitor reverses cognitive impairments in elderly diabetics. Hypertension 74: A051–A051, 2019. doi: 10.1161/hyp.74.suppl_1.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Trudeau K, Molina AJ, Roy S. High glucose induces mitochondrial morphology and metabolic changes in retinal pericytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52: 8657–8664, 2011. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kowluru RA. Diabetic retinopathy: mitochondrial dysfunction and retinal capillary cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal 7: 1581–1587, 2005. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lagaud GJ, Masih-Khan E, Kai S, van Breemen C, Dube GP. Influence of type II diabetes on arterial tone and endothelial function in murine mesenteric resistance arteries. J Vasc Res 38: 578–589, 2001. doi: 10.1159/000051094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tabit CE, Chung WB, Hamburg NM, Vita JA. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 11: 61–74, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s11154-010-9134-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ungvari Z, Tarantini S, Nyul-Toth A, Kiss T, Yabluchanskiy A, Csipo T, Balasubramanian P, Lipecz A, Benyo Z, Csiszar A. Nrf2 dysfunction and impaired cellular resilience to oxidative stressors in the aged vasculature: from increased cellular senescence to the pathogenesis of age-related vascular diseases. Geroscience 41: 727–738, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11357-019-00107-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Goldin A, Beckman JA, Schmidt AM, Creager MA. Advanced glycation end products: sparking the development of diabetic vascular injury. Circulation 114: 597–605, 2006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Farkas E, Luiten PG. Cerebral microvascular pathology in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neurobiol 64: 575–611, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(00)00068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Johnson PC, Brendel K, Meezan E. Thickened cerebral cortical capillary basement membranes in diabetics. Arch Pathol Lab Med 106: 214–217, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Thomsen MS, Routhe LJ, Moos T. The vascular basement membrane in the healthy and pathological brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 37: 3300–3317, 2017. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17722436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Greene C, Hanley N, Campbell M. Claudin-5: gatekeeper of neurological function. Fluids Barriers CNS 16: 3, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s12987-019-0123-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xu H, Hu F, Sado Y, Ninomiya Y, Borza DB, Ungvari Z, Lagamma EF, Csiszar A, Nedergaard M, Ballabh P. Maturational changes in laminin, fibronectin, collagen IV, and perlecan in germinal matrix, cortex, and white matter and effect of betamethasone. J Neurosci Res 86: 1482–1500, 2008. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]