Abstract

Purpose

Light is a salient cue that can influence neurodevelopment and the immune system. Light exposure out of sync with the endogenous clock causes circadian disruption and chronic disease. Environmental light exposure may contribute to developmental programming of metabolic and neurological systems but has been largely overlooked in Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) research. Here, we investigated whether developmental light exposure altered programming of visual and metabolic systems.

Methods

Pregnant mice and pups were exposed to control light (12:12 light:dark) or weekly light cycle inversions (circadian disruption [CD]) until weaning, after which male and female offspring were housed in control light and longitudinally measured to evaluate differences in growth (weight), glucose tolerance, visual function (optomotor response), and retinal function (electroretinogram), with and without high fat diet (HFD) challenge. Retinal microglia and macrophages were quantified by positive Iba1 and CD11b immunofluorescence.

Results

CD exposure caused impaired visual function and increased retinal immune cell expression in adult offspring. When challenged with HFD, CD offspring also exhibited altered retinal function and sex-specific impairments in glucose tolerance.

Conclusions

Overall, these findings suggest that the light environment contributes to developmental programming of the metabolic and visual systems, potentially promoting a pro-inflammatory milieu in the retina and increasing the risk of visual disease later in life.

Keywords: circadian disruption, environmental light, inflammation, high fat diet (HFD), Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD)

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis posits that early life exposures affect disease risk later in life.1 The DOHaD framework began with epidemiological studies of nutrition, which found that mismatch between developmental and later life environment, such as undernutrition in utero and rich postnatal diet, increased diseases such as hypertension and diabetes.2 Like nutrition, light is a salient biological cue and can prime metabolic, immune, endocrine, and neurological systems to alter the trajectory of health and disease.3–7

Light exerts many effects via the circadian system, molecular and physiological “clocks” that regulate biochemical and signaling processes.8 Light acts as a “zeitgeber,” or “time giver, to synchronize the body's central and peripheral clocks, and is the most powerful entraining cue. Given the crosstalk among the circadian system, metabolism, neurological function, and the immune system, circadian disruption can cause dyslipidemia,9 glucose intolerance,10,11 cognitive impairment,12–14 and altered immune function15–18 in both epidemiological and animal studies.19 Shift work, an occupational cause of circadian disruption, increases the risk of diabetes and cardiometabolic disease20,21; likewise, rodents developmentally exposed to chronodisruption develop glucose intolerance as adults.3,22

A window to the brain, the retina can serve as a marker of neurological health.23 Circadian clocks function in ocular tissues and regulate processes, such as retinal differentiation, intraocular pressure, photoreceptor disc shedding, and visual processing,24–26 the dysregulation of which can lead to visual impairment and blindness.27 Similar to the brain, the retina has high metabolic demands and is affected by metabolic disorders, such as diabetes. Unfortunately, environmental light exposure has been largely overlooked in studies of DOHaD and developmental programming.

Given the rapid rise in technologies and behavior that contributes to circadian disruption, the question of how our modern light environment relates to human development and disease is important.28,29 DOHaD studies evaluate disease trajectories after a developmental insult in the mother, followed by a challenge to the offspring, termed the “first hit/second hit” framework.30 The “second hit” can expose existing vulnerabilities that may not be obvious at baseline. Therefore, to investigate the impacts of developmental light environment on metabolic and neurological programming, mice were exposed to developmental circadian disruption and challenged with a high fat diet (HFD) later in life.

Methods

Animals and Developmental Light Treatment

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Healthcare System and conducted in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. The C57BL/6J offspring used in this study were bred in-house from C57BL/6J mice obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Male breeders were singly housed in standard conditions (ad libitum chow, 12:12 lighting) and female breeders were randomized and housed in large, wire-top cages. Naïve female breeders acclimated for 2 weeks in standard (12:12 light:dark) light conditions before randomization to either control treatment lighting (CL, n = 12) conditions (12:12 light:dark) or circadian disruption (CD, n = 13) lighting conditions where light cycle was inverted every 3 to 4 days (Fig. 1A), similar to other developmental studies.22,31 White LED light composition was measured with an Exemplar Smart CCD Spectrometer (B&W Tek, Newark, DE, USA) and spectra validated to be characteristic of neutral white LED light, with a peak at 450 nm and rounded peak around 575 nm. Lux levels were tested and calibrated to be equal between the two light treatment groups and ranged between approximately 50 to 400 lux, depending on the position and depth of the lux meter (Dual-range light meter 3151CC; Traceable, Webster, TX, USA) in the cage; lux measurements at the wire-top neared 400 lux due to proximity to the light source, whereas lux measurements taken from the cage floor underneath the food holder were around 50 lux. Mice from the CL and CD groups were housed in the same cage type and setup, so luminance ranges were equal between the groups.

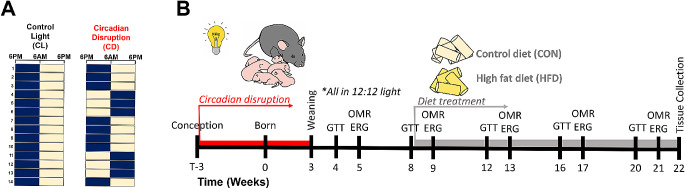

Figure 1.

Overall experimental design and timeline. (A) Dams and offspring (both sexes) were developmentally exposed to control light (CL) treatment (12:12 lights on at 6 AM and off at 6 PM) or circadian disruption (CD) treatment (inversion of photoperiod every 3–4 days). The navy blue and yellow boxes each represent a time period of 12 hours, with navy representing lights off and yellow representing lights on; each row is a new day. (B) Diagram of the experimental timeline. Female breeders and their pups were exposed to CL or CD light conditions during development, as represented by the lightbulb symbol and female with pups. At weaning (3 weeks age), offspring were all housed in control light conditions and fed standard rodent chow ad libitum. At 8 weeks of age, immediately following glucose tolerance test, offspring were fed with either high fat diet (HFD) or ingredient-matched control diet (CON) ad libitum, represented by the pale yellow and bright yellow cylinders. Glucose tolerance testing (GTT), visual function using optomotor response (OMR), and retinal function using electroretinogram (ERG) were longitudinally tested from 4 to 21 weeks of age. Tissues were collected for analysis at 22 weeks of age.

After 4 weeks of light treatment, 2 females, one from each light treatment group, were placed in a male's cage for 2 days for timed breeding during concordant light schedules before being returned to their home cages. Females were checked for vaginal plugs after pairings and weighed to confirm pregnancy. Nonpregnant females were re-paired with the same male. Dams and pups remained in CD or CL light treatments until weaning at three weeks of age (Fig. 1B). Developmental light treatment and dam ID were recorded for each pup and kept masked for the duration of the experiment.

From weaning onward, offspring were housed in standard lighting conditions (12:12 light:dark). Offspring were fed standard rodent chow (Teklad Rodent Diet 2018 irradiated 2918; Envigo Tekland, Madison, WI, USA) ad libitum from weaning until 8 weeks of age. Immediately following the glucose tolerance test (GTT) at 8 weeks of age, mice were randomized to receive either Western-style HFD (42% calories from fat, TD.88137; Envigo Tekland) or ingredient-matched control diet (CON; 13% calories from fat, TD.08485; Envigo Tekland) ad libitum for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 1B). At 22 weeks of age, adult offspring were euthanized between 10 AM and 12 PM (zeitgeber time [ZT] ZT4-ZT6) and tissue samples collected and flash frozen or preserved for cryosectioning and stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Actigraphy

Activity patterns of female mice exposed to CL or CD were measured using custom-built Arduino-based passive infrared motion detectors (PIRs; Fig. 2A)32 that collected activity data every 10 seconds. Actigraphy data from PIRs was further validated with running wheels (ENV-047; Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA). Actograms from PIRs and running wheels were created in ImageJ using the ActogramJ plugin.33 Measures of intradaily stability, intradaily variability, and relative amplitude were calculated using the nparACT package in R software.34

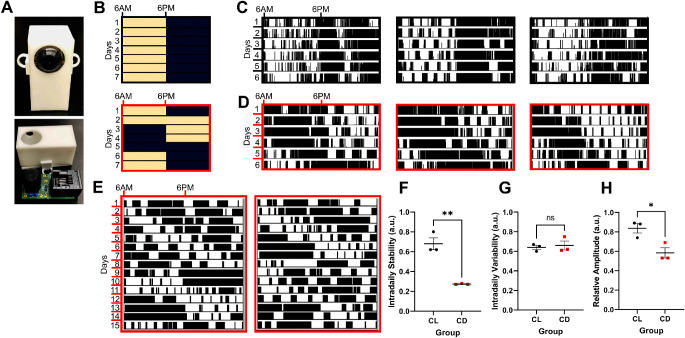

Figure 2.

Mice exposed to circadian disruption (CD) light conditions have altered activity rhythms. (A) Picture of the custom-built infrared motion sensor (PIR), showing (above) the sensor as encased in a 3D-printed plastic shell and (below) removed from the case showing the circuit board and components. (B) Representative control light (CL) cycle (black outline), with lights on (pale yellow shading) at 6 AM and lights off (navy blue shading) at 6 PM, and CD light cycle (red outline), with light inversions twice weekly (note that this is the same schedule as shown in Figure 1, but plotted with different start time). (C) Representative single-plotted actograms from 3 cages of female mice exposed to CL over a 6-day period, with vertical black lines indicating activity and each row representing a 24-hour period. (D) Representative single-plotted actograms from 3 cages of female mice exposed to CD over a 6-day period, with black lines indicating activity and each row a 24-hour period. (E) Representative actograms from running wheels of females exposed to CD over a 15-day period, with black lines indicating activity and each row a 24-hour period. (F) Intradaily stability (t = 6.77, df = 4, P = 0.003), (G) intradaily variability (t = 0.40, df = 4, P = 0.71), and (H) relative amplitude (t = 3.52, df = 4, P = 0.025) as calculated from the representative actograms in C and D, presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with student's 2-tailed unpaired t-tests, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

Serum Lipids and Glucose Panel

Dams were euthanized at weaning between 9 AM and 11 AM (ZT 3–ZT 5) during concordant light schedules. Serum was collected (1.1 mL Z-gel microtube; Sarstedt, Germany) and stored at −80°C. Serum samples were analyzed for lipids, glucose, and free fatty acids (FFAs) on a Beckman Coulter AU480 chemistry autoanalyzer (Brea, CA, USA) using Sekisui Diagnostics (Burlington, MA, USA) reagents and calibrators.

Weekly Weight and Blood Glucose

Mice were measured weekly for body weight and blood glucose (mg/dL) using a handheld glucometer (FreeStyle Lite; Abbott Diabetes Care, Alameda, CA, USA). Prior to glucose recording, the tail was gently cleaned to remove any debris, lightly pricked with an insulin needle (BD insulin syringe #32946), and a drop of blood collected on the glucometer strip.

Glucose Tolerance Testing

Intraperitoneal (IP) GTT was performed at 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 weeks of age. On the day of the test, food was removed at 7 AM (ZT 1) and mice fasted for 6 hours. At 1 PM (ZT 7), baseline blood glucose (mg/dL) of mice was measured just prior to IP injection of glucose solution (D+ glucose in dH2O, 2g/kg)35 and ensuing blood glucose (mg/dL) levels were recorded at 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes postinjection using a handheld glucometer (FreeStyle Lite; Abbott Diabetes Care). To summarize the hyperglycemia response, area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for each mouse using the trapezoidal method.36

Optomotor Response Testing

Visual function was measured with optomotor response (OMR) testing at 5, 9, 13, 17, and 21 weeks of age, as previously described37–39 using the OptoMotry system (Cerebral Mechanics, USA).40 Briefly, a mouse was placed on a central pedestal in an enclosed chamber of monitors, which display rotating vertical sine wave gratings of varying spatial frequency (with contrast set at 100%) or varying grating contrast (with spatial frequency set at 0.103 cycles/degree). A trained observer marked when the characteristic head tracking movement occurred (or did not occur) through a programmed staircase method to calculate the visual threshold. Measurements from the left and right eye were averaged for a combined visual threshold score. Contrast threshold results were converted to Michelson contrast values.41

Electroretinography

Retinal function was measured using electroretinography (ERGs) at 5, 9, 13, 17, and 21 weeks of age, following OMR testing. Mice were dark-adapted overnight, anesthetized with an IP injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (16 mg/kg), placed on a heating pad (37°C to maintain body temperature), and given corneal numbing drops (0.5% tetracaine hydrochloride; Bausch and Lomb) and drops for pupil dilation (1.0% tropicamide solution; Sandoz, Alcon) under dim red light. Anesthetized mice were placed on a heated platform (37°C to maintain body temperature) and ground and reference electrodes inserted into the tail and each cheek (Natus neurology Genuine Grass Platinum Subdermal Electrodes #F-E2-48). Custom-made gold loop recording electrodes were gently placed on each cornea and methylcellulose drops (1% carboxyl methylcellulose, Refresh Celluvisc; Allergan) applied after placement to prevent eye dryness and maintain electrode connection. Post-measurement, mice were given an IP injection of atipamezole (1 mg/kg) (Antisedan; Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ, USA) to counteract the effects of anesthesia,42 saline eye drops, and allowed to recover on a heating pad (37°C) before being returned to housing.

ERGs were performed using a 6-step protocol comprised of 5 scotopic stimuli of increasing luminance (−2.5, −1.9, −0.6, 0.8, and 1.9 log cd s/m2) followed by a 10-minute light adaptation step (1.5 log cd s/m2) and final flicker photopic stimulus (1.4 log cd s/m2 at 6.1 Hz) 43,44; this protocol measured the rod-dominated, mixed, and cone-dominated retinal responses. For the ERGs performed at 21 weeks of age, an additional photopic step was included to measure blue/green cone (M-opsin) response using a green LED flash (530 nm, 0.1 log cd s/m2) following the photopic flicker step. Retinal responses were recorded, oscillatory potentials (OPs) extracted (75–500 Hz), and signals averaged using the LKC software (UTAS BigShot; LKC Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA); waveforms were marked in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). For each mouse, the waveform from the eye with the highest b-wave amplitudes from the brightest dark-adapted step (flash stimulus = 1.9 log cd s/m2) was used for analysis.

Retinal Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Fresh whole eyes were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose. Tissues were embedded and frozen in optimal cutting temperature compound and sliced into 10-µm-thick sections. Blocking (with 0.1% Triton X-100) and primary antibody incubations on retinal sections were in 5% normal donkey serum in PBS and washed with PBS. Primary antibody incubations using Iba1 (ab178847; 1:100; Abcam) and CD11b (14-0112-82; 1:100; Invitrogen) were performed for 16 to 24 hours at 4°C. Secondary antibody incubations using Alexa Fluor 488 Donkey anti-mouse IgG (A-21202; 1:500) and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Donkey anti-rabbit IgG (A-31573; 1:500) and tissue nuclei visualized with nuclear stain 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 62247; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Coverslips were mounted using Prolong Gold (P36934; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Retinal tissue (n = 4–7 mice/group; 2–3 images per sample) images were taken on an Olympus Fluoview1000 confocal microscope (Center Valley, PA, USA) with a 20 times objective and a Lumenera INFINITY 1-3C USB 2.0 Color Microscope camera (Spectra Services, Ontario, NY, USA) by a researcher masked to treatment group. All images were compiled and quantified using ImageJ software. Fluorescence for each image was quantified by dividing the mean fluorescence by the imaging area; mean fluorescence across images was then averaged for each sample for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis and Data Availability

Longitudinal metabolic and visual measures were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA or mixed models (in the case of missing data) with post hoc Dunnett tests to compare treatment groups to the CL + CON control group, correcting for multiple comparisons. Nonlongitudinal data was measured using a 1-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett tests to compare treatment groups to the CL + CON control group, correcting for multiple comparisons. Dam serum results, intradaily stability, intradaily variability, and relative amplitude were analyzed with Student's unpaired 2-tailed t-tests. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM and results were considered significant if P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.0.0 and R version 3.2. Data and R code are available at: https://github.com/dclarktown/Light_mice (DOI:10.5281/zenodo.4536522).

Results

Circadian Disruption during Development Alters Activity Patterns

Actigraphy data confirmed that, compared to CL (Figs. 2B, 2C), CD treatment altered activity patterns (Figs. 2B, 2D), similar to other studies using the same light paradigm31,45; results were validated with running wheels (Fig. 2E). Disrupted mice had decreased intradaily stability and relative amplitude, suggesting weaker coupling to zeitgebers (e.g. light) and dampening of circadian rhythms in CD mice; however, there was no difference in intradaily variability, a marker of activity fragmentation (Figs. 2F–H).

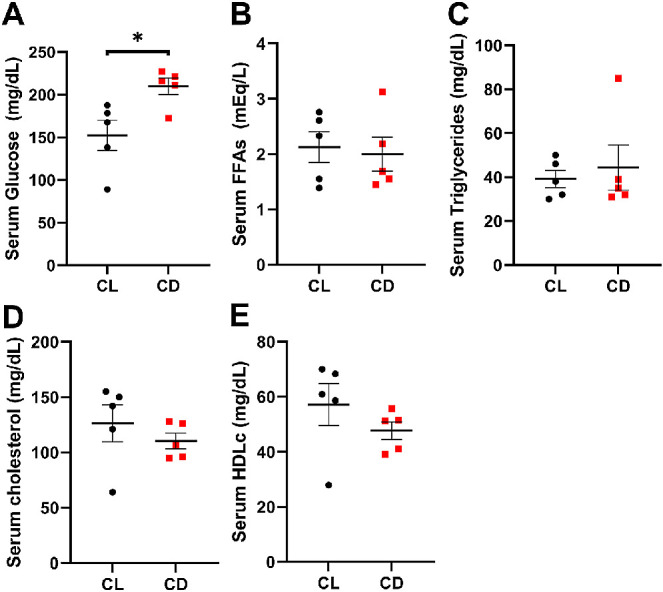

Circadian Disruption Alters Maternal Serum Glucose

At weaning, CD dams had significantly higher serum glucose (Fig. 3A; Student's unpaired t-test [t = 2.892, df = 7], P = 0.023) than CL dams. Serum FFAs, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and high density lipoproteins (HDLc) did not differ between groups (Figs. 3B–E).

Figure 3.

Circadian disruption increases serum glucose levels. At weaning, dams in the CD group had higher serum (A) glucose (t = 2.836, df = 8, P = 0.022) but similar levels of (B) free fatty acids (FFAs; t = 0.3135, df = 8, P = 0.762), (C) triglycerides (t = 0.4747, df = 8, P = 0.648), (D) cholesterol (t = 0.8841, df = 8, P = 0.402), and (E) high density lipoprotein (HDLc; t = 1.141, df = 8, P = 0.287) compared to dams in the CL group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with Student's 2-tailed unpaired t-tests, *P < 0.05, n = 5 per group.

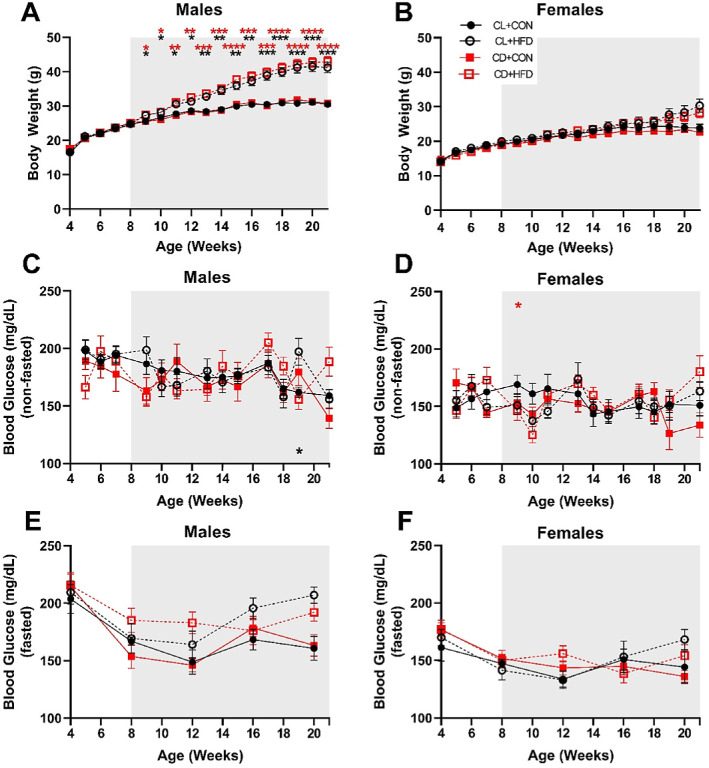

HFD Has Sex-Specific Influences on Body Weight and Blood Glucose

Male mice fed an HFD developed higher body weight over time (Fig. 4A). Irrespective of developmental light treatment, male HFD groups were significantly heavier than the control groups (mixed-effects, group*time: F(51, 559) = 22.77, P < 0.0001), starting just 1 week after diet treatment (9 weeks of age, P < 0.05) and continuing until the end of the experiment (21 weeks of age, P < 0.001). Although the interaction was significant (mixed-effects, group*time: F(51, 549) = 3.280, P < 0.0001), female mice fed an HFD did not significantly differ in body weight in post hoc analyses (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Only male mice gained weight after HFD exposure. (A) Male HFD groups developed significantly higher body weight starting at 9 weeks, 1 week after start of diet treatment (mixed-effects analysis, F(51, 559) = 22.77, P < 0.0001). (B) Female mice showed an interaction between time and treatment (mixed-effects analysis, F(51, 549) = 3.28, P < 0.0001), but no significant differences between treatment groups. (C) CL + HFD males had significantly higher blood glucose (non-fasted) at 19 weeks (mixed-effects analysis, F(36, 386) = 1.74, P = 0.006). (D) CD + HFD females had significantly lower blood glucose (non-fasted) at 10 weeks (mixed-effects analysis, F(36, 385) = 1.63, P = 0.015). There were no differences between groups in blood glucose levels after fasting for 6 hours (prior to GTT) in (E) males (mixed-effects analysis, F(12, 132) = 1.56, P = 0.11) or (F) females (mixed-effects analysis, F(12, 128) = 1.35, P = 0.20). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by mixed models with post-hoc Dunnett tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 versus the CL + CON group. Black asterisks indicate the CL + HFD group and red asterisks indicate the CD + HFD group. Grey shading indicates period of diet treatment. For males, CL + CON n = 8 to 10, CL + HFD n = 9 to 10, CD + CON n = 7 to 9, and CD + HFD n = 8 to 10 at each timepoint; for females, CL + CON n = 8 to 9, CL + HFD n = 5 to 9, CD + CON n = 9 to 10, and CD + HFD n = 7 to 11 at each timepoint.

Weekly blood glucose measurements varied considerably; male mice fed an HFD with developmental circadian disruption had significantly higher nonfasted blood glucose levels (mixed-effects, group*time: F(36, 386) = 1.742, P = 0.006) at 19 weeks of age compared to the control group (P < 0.05; Fig. 4C). Female mice fed an HFD with developmental circadian disruption had slightly lower nonfasted blood glucose levels at 10 weeks of age compared to the control group (mixed-effects, group*time: F(36, 385) = 1.629, P = 0.0146, P < 0.05; Fig. 4D). There were no differences in fasted blood glucose levels between groups (Figs. 4E, 4F).

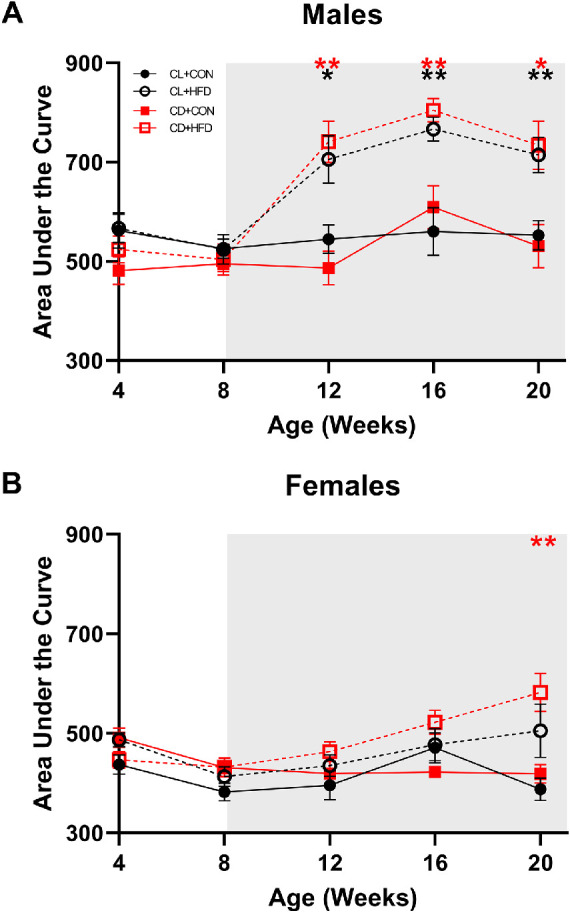

HFD and Developmental Disruption Impair Glucose Tolerance

There were no differences in glucose tolerance between groups at 4 or 8 weeks of age (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. S1), prior to diet treatment. However, at 12 and 16 weeks of age, there were significant interactions between sex and treatment (2-way ANOVA, sex*diet: P < 0.01), with HFD males displaying impaired glucose tolerance after 1 month of diet treatment. CD + HFD males also developed elevated blood glucose more rapidly postinjection compared to CL + CON (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 132) = 4.130, P = 0.0001, P < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. S1E). This trend of worsened glucose tolerance in the male CD + HFD and CL + HFD groups continued at 16 and 20 weeks of age (P < 0.05; see Fig. 5A, Supplementary Fig. S1G, S1I), whereas females did not differ in glucose tolerance until CD + HFD females developed elevated glucose at 20 weeks of age (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 126) = 3.069, P = 0.0008, P < 0.05; see Fig. 5B, Supplementary Fig. S1J).

Figure 5.

Males on HFD have higher area under the curve (AUC) values of glucose tolerance testing and at earlier timepoints than females. (A) Male AUC values; CD + HFD and CL + HFD groups had higher AUC values at 12, 16, and 20 weeks of age compared to the CL + CON group (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 132) = 4.13, P < 0.0001, P < 0.05). (B) Female AUC values; CD + HFD group had higher AUC values at 20 weeks of age compared to the CL + CON group (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 126) = 3.07, P < 0.001, P < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by mixed models with Dunnett tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 versus CL + CON group. Black asterisks indicate the CL + HFD group and red asterisks indicate the CD + HFD group. Grey shading indicates period of diet treatment. For males, CL + CON n = 9 to 10, CL + HFD n = 9 to 10, CD + CON n = 8 to 9, and CD + HFD n = 9 to 10 at each timepoint; for females, CL + CON n = 8 to 9, CL + HFD n = 6 to 9, CD + CON n = 7 to 10, and CD + HFD n = 7 to 11 at each timepoint.

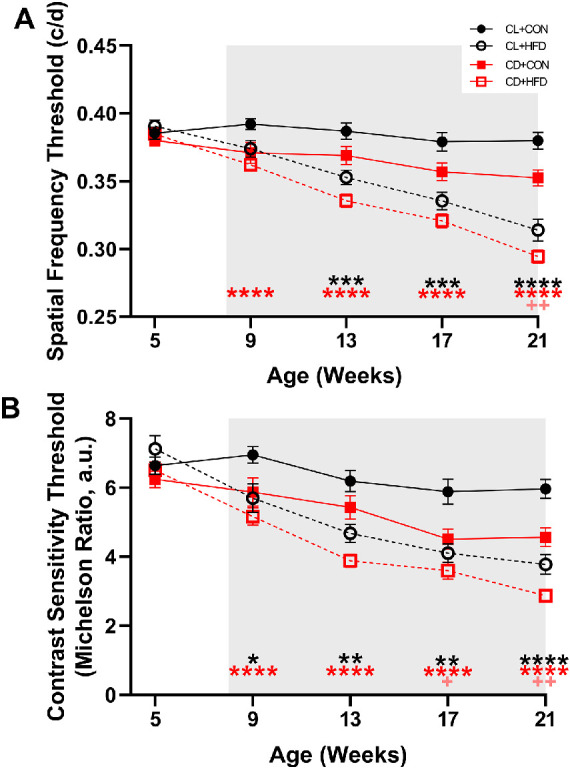

Developmental Circadian Disruption and HFD Reduce Visual Function

OMR results did not differ at baseline, but by 9 weeks of age (1 week after diet start), CD + HFD mice exhibited decreased spatial frequency (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 275) = 14.33, P < 0.0001, P < 0.001; Fig. 6A); at 13, 17, and 20 weeks of age, CD + HFD and CL + HFD had decreased spatial frequency, and at 20 weeks of age CD + CON had decreased spatial frequency compared to CL + CON (P < 0.01; see Fig. 6A). Likewise, CD + HFD and CL + HFD exhibited decreased contrast sensitivity at 9 and 13 weeks of age, and all groups had decreased contrast sensitivity at 17 and 20 weeks of age compared to CL + CON (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 275) = 8.233, P < 0.0001, P < 0.05; see Fig. 6B). Although there were no significant interactions between sex and treatment, sex as a main effect was significant for frequency at 5, 9, and 13 weeks and for contrast at all time points, with males having slightly higher visual acuity.46

Figure 6.

HFD and developmental circadian disruption reduced visual function. (A) Spatial frequency thresholds decreased after the induction of HFD (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 275) = 14.33, P < 0.0001) in the CD + HFD group (P < 0.05), whereas the CL + HFD group developed decreased spatial frequency slightly later (P < 0.05) and the CD + CON group had decreased visual frequency at 20 weeks of age (P < 0.05). (B) Contrast sensitivity thresholds decreased after exposure to HFD (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 275) = 8.23, P < 0.0001) in the CD + HFD and CL + HFD groups (P < 0.05), whereas the CD + CON group had decreased contrast sensitivity at 17 and 21 weeks of age compared to the CL + CON group (P < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by mixed models with Dunnett tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 versus the CL + CON group. Black asterisks indicate the CL + HFD group, red asterisks indicate the CD + HFD group, and pink crosses indicate the CD + CON group. Grey shading indicates period of diet treatment. For each timepoint, CL + CON n = 17 to 19, CL + HFD n = 14 to 19, CD + CON n = 17 to 19, and CD + HFD n = 16 to 21.

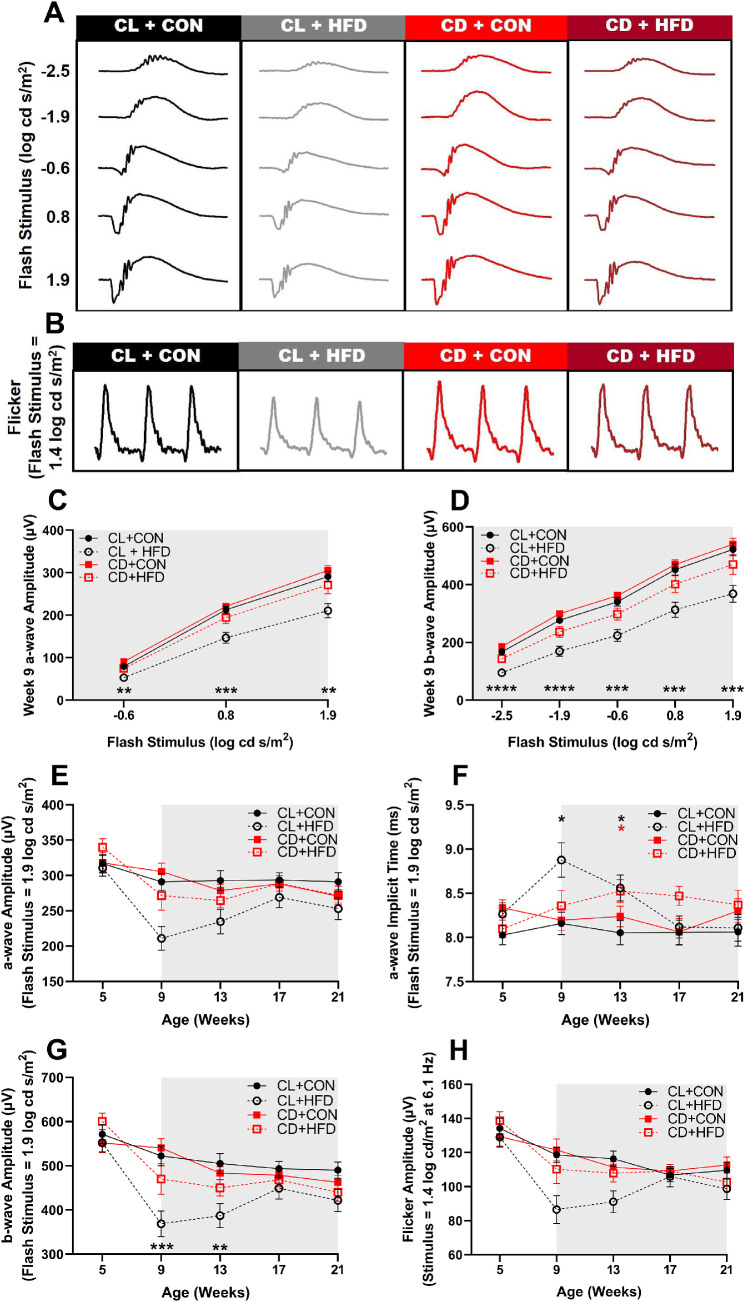

Developmental Disruption Alters Retinal Function in Response to HFD

Results of scotopic full-field ERGs revealed retinal function deficits. Representative scotopic (Fig. 7A) and photopic flicker (Fig. 7B) waveforms visibly show amplitude differences at 9 weeks of age, after 1 week of HFD. As shown in the intensity response curve, the CL + HFD group had lower a-wave (2-way ANOVA, F(6, 140) = 4.025, P < 0.001, P < 0.05; Fig. 7C) and b-wave (2-way ANOVA, F(12, 280) = 2.519, P < 0.01, P < 0.05; Fig. 7D) amplitudes. When analyzed over time, a-wave amplitudes did not significantly differ (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 260) = 1.686, P = 0.069; Fig. 7E), but a-wave implicit times (ITs) did differ (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 260) = 1.957, P < 0.05; Fig. 7F), with the CL + HFD group showing delayed ITs at 9 and 13 weeks (P < 0.05) and CD + HFD at 13 weeks (P < 0.05). There were also deficits in b-wave amplitudes over time (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 260) = 1.957, P < 0.05; Fig. 7G) in the CL + HFD group at 9 (P < 0.001) and 13 (P < 0.01) weeks of age. However, there were no differences in flicker b-wave amplitudes over time (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 255) = 1.699, P = 0.067; Fig. 7H) or in green cone b-wave amplitude when measured at 21 weeks of age (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 47) = 1.465, P = 0.236; Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 7.

Transient deficits in retinal function after acute HFD treatment. Representative ERG waveforms at 9 weeks of age (1 week after HFD) in response to (A) a series of scotopic stimuli and (B) photopic flicker stimuli showing visible amplitude deficits in the CL + HFD group. (C) Intensity response curve of a-wave amplitudes at 9 weeks of age (2-way ANOVA, F(6, 140) = 4.03, P < 0.001) show decreased amplitudes in the CL + HFD group. (D) Intensity response curve of b-wave amplitudes at 9 weeks of age (2-way ANOVA, F(12, 280) = 2.52, P < 0.005) shows decreased amplitudes in the CL + HFD group. (E) The a-wave amplitudes (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 260) = 1.69, P = 0.069) over time and (F) implicit times (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 260) = 1.96, P < 0.05) with delays in the CL + HFD and the CD + HFD groups. (G) The b-wave scotopic (−2.5, −1.9, −0.6, 0.8, and 1.9 log cd s/m2) amplitudes (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 260) = 2.32, P < 0.01) and (H) flicker amplitudes (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 255) = 1.70, P = 0.067) over time. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by 2-way ANOVAs or mixed models with Dunnett tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 versus the CL + CON group. Black asterisks indicate the CL + HFD group and red asterisks indicate the CD + HFD group. Grey shading indicates period of diet treatment. For each timepoint, CL + CON n = 16 to 19, CL + HFD n = 14 to 19, CD + CON n = 15 to 19, and CD + HFD n = 15 to 21.

OPs, generated by amacrine cells in the inner retina,47 were also affected by HFD treatment (Supplementary Fig. S3). Amplitude deficits in OP2 (mixed-effects, group*time: F(12, 260) = 2.436, P < 0.01), but not OP4, occurred in the CL + HFD group at 9, 13, and 21 weeks (P < 0.05) and in the CD + HFD group at 21 weeks of age (P < 0.05). These results suggest HFD-induced impairment in ON-pathway and rod activity (OP2) but not in OFF-pathway and cone signaling (OP4).48

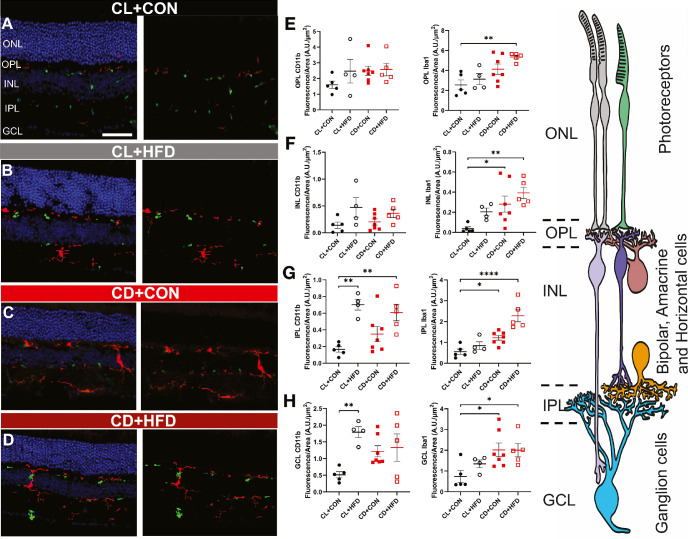

Increased Retinal Microglia and Macrophage Expression in Response to Altered Developmental Light Environment and HFD

Retinal inflammatory response increased significantly within CD + CON, CL + HFD, and CD + HFD groups (Fig. 8). CD11b-positive and Iba1-positive cells (labeling microglia and macrophages) were not only observed within the inner retinal layers, where they typically reside (ganglion cell layer [GCL], inner plexiform layer [IPL] and outer plexiform layer [OPL]), but were also found in the inner nuclear layer (INL) and reached the outer nuclear layer (ONL; Supplementary Fig. S4), where the cell bodies of rods and cones reside.

Figure 8.

Both CD and HFD cause increased retinal immune activation, as measured by CD11b (green) and Iba1 (red). Representative retinal immunofluorescence microscopy results, with (left) and without (right) DAPI staining (blue), showing retinal layers of the (A) CL + CON group, the (B) CL + HFD group, the (C) CD + CON group, and the (D) CD + HFD group show increased retinal expression of CD11b in CL + HFD, CD + CON, and CD + HFD groups and increased retinal expression of Iba1 in the CD + CON and CD + HFD groups. Measured fluorescence by retinal layer, showing no difference in (E) CD11b staining in the OPL (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 1.23, P = 0.33) but increased Iba1 staining in the OPL (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 6.25, P = 0.0047) in the CD + HFD group. (F) In the INL, there was also no difference in CD11b expression (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 2.52, P = 0.092), but Iba1 expression was increased (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 5.36, P = 0.022) in the CD + CON and CD + HFD groups. In the IPL, (G) CD11b increased (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 8.06, P = 0.0015) in both HFD groups while Iba1 increased (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 15.87, P < 0.0001) in both CD groups. Likewise, in the GCL, (H) CD11b was increased (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 4.34, P = 0.019) in the CL + HFD group and Iba1 was increased (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 3.89, P = 0.023) in both CD groups. (I) Drawing representing the retinal layers. Images from the CL + CON group (n = 5 mice), CL + HFD group (n = 4 mice), CD + CON group (n = 7 mice), and CD + HFD group (n = 5 mice) include both sexes. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by 1-way ANOVAs with Dunnett tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 versus the CL + CON group. Scale bar = 12 µm.

Imaging found no difference in CD11b staining in the OPL (Fig. 8E, 1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 1.23, P = 0.33) or INL (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 1.49, P = 0.09); conversely, Iba1 staining was increased in the OPL (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 6.25, P = 0.0047) in the CD + HFD group. Comparatively, in the INL (Fig. 8F) Iba1 expression was greater (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 9.67, P = 0.02) in the CD + CON and CD + HFD groups. In the IPL, (Fig. 8G) CD11b increased (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 8.06, P = 0.0015) in both HFD groups, whereas Iba1 increased (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 15.87, P < 0.0001) in both CD groups. Likewise, in the GCL, (Fig. 8H) CD11b was increased (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 4.34, P = 0.019) in the CL + HFD group and Iba1 was increased (1-way ANOVA, F(3, 17) = 3.89, P = 0.028) in both CD groups.

Discussion

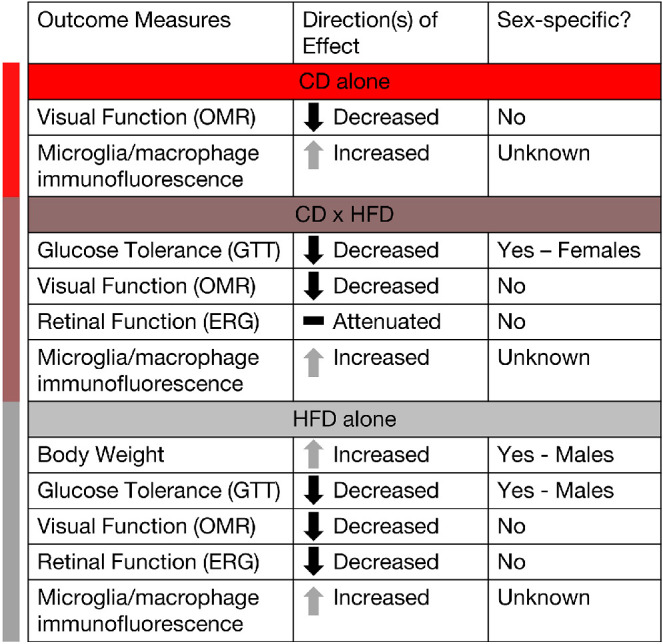

We investigated the influence of light environment on developmental programming of metabolic and visual outcomes. Developmental chronodisruption during a vulnerable window (E0 – 3 weeks) reduced visual function, altered retinal function, increased retinal microglial/macrophage activation, and impaired glucose tolerance in offspring (Fig. 9), with differences exacerbated after metabolic challenge with HFD. The findings of increased expression of retinal microglial and macrophage markers supports a role for immune system activation in mediating the visual function results.49–51 Overall, the findings support environmental light as a relevant exposure for developmental programming and DOHaD.

Figure 9.

Summary figure highlighting the influence of developmental light treatment and/or later HFD treatment on visual and metabolic outcomes and whether outcomes differed by sex.

Although previous research using genetic knockouts has been useful in understanding the contribution of specific clock genes to development, the use of environmental light to cause circadian disruption is relevant in modeling human exposure and disease. Prior studies have found that developmental chronodisruption dampens maternal rhythms in corticosterone, FFAs, cholesterol, and triglycerides,45 and alters activity rhythms.31,45 Likewise, we report altered activity (see Fig. 2) and increased serum glucose in CD dams (see Fig. 3), although the glucose results may be due to disruption and timing of sample collection rather than mean differences since we did not take multiple measurements at specific time intervals. In offspring, maternal environmental circadian disruption causes increased adiposity, hyperleptinemia,22 altered glucose handling,22,31 anxiety-like behavior,6 and increased blood pressure31,52; however, previous studies have not characterized the effects on the visual system.

In this study, metabolic outcomes exhibited clear sex differences (see Figs. 4, 5, Supplementary Fig. S1), as previously reported.53–56 Although all males fed an HFD developed worse glucose tolerance, notably, only the CD + HFD females developed impaired glucose tolerance, suggesting a sex-specific interaction between developmental light environment and later nutritional challenge. These glucose tolerance results align with previous findings of altered glucose homeostasis and metabolism in offspring following developmental circadian disruption22,31 and suggest that developmental chronodisruption enacts sex-specific effects on metabolic programming.57,58

Developmental chronodisruption led to decreased visual function, the pace of which was quickened by HFD (see Fig. 6). HFD alone also impaired visual function, the impact of which has not been well studied59; a previous study utilizing a high-fat, high-sucrose diet reported no differences,60 whereas another reported decreased OMR responses after 2 months of HFD (Douglass, AJ et al. IOVS 2020;61:ARVO E-Abstract 2245). However, an optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) study uncovered rapid neurovascular decoupling after sugary beverage consumption,61 suggesting clinical relevance for acute nutritional challenge. OMR measures the accessory optic system reflex in the retina from velocity-selective and direction-selective ON retinal ganglion cells.62,63 The increased retinal expression of retinal microglial and macrophage markers in the GCL layer of CD and CD + HFD mice supports a potential role for immune system activation in driving the visual function results.

Developmental light treatment altered retinal function responses to HFD challenge (see Fig. 7). The largest ERG a-wave and b-wave amplitude deficits occurred acutely in the CL + HFD group, with partial recovery. The retina has high energy needs, is sensitive to metabolic perturbations,64 and utilizes both glucose and lipids as fuel65; acute metabolic imbalance due to increased dietary fat may have caused ERG amplitude deficits. Surprisingly, ERG amplitude deficits were attenuated in the CD + HFD group. Developmental CD may have influenced retinal response to metabolic challenge.

Inflammasome activation is a well-known contributor to retinal disease pathology. Our study is novel in its investigation of the effects of developmental CD with later life HFD challenge in regard to retinal inflammation (see Fig. 8). Several studies have described increased retinal inflammation associated with HFD, primarily in regard to its role in diabetes.59,66–70 In the retina, HFD induces toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) dependent macrophages and microglial activation, a signaling pathway involved in chronic inflammation and insulin resistance.69 Likewise, retinal CD11b microglia and/or macrophages activation is observed in patients with diabetes and in diabetic animal models.71–73 In CD and HFD-treated mice, we found upregulation of Iba1-positive cells (microglia) and CD11b-positive cells (microglia and macrophages) within inner retinal layers (GCL, IPL, and OPL), as well as upregulation of Iba1 in the INL. Our results support that CD + HFD elicits a chronic inflammatory response within the inner retina. The circadian system regulates immune signaling,74–76 and increased microglial activation and astrogliosis occurs in mice with circadian clock gene knockout Rev-erbα77 and Arntl (Bmal1).78 As such, the upregulation in retinal inflammatory markers in CD mice may be due to lingering effects of developmental circadian disruption, aggravated by an HFD. This retinal inflammation correlates with the visual impairment and altered retinal function we found in CD-exposed and HFD-exposed offspring.

Several limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting our findings. As the C57BL/6J mouse strain is melatonin-deficient, these outcomes are independent of melatonin, a key circadian hormone and antioxidant; as untimely light exposure can disrupt melatonin production and rhythms in humans, the relevance of these results to human health requires further characterization of developmental circadian disruption in melatonin-proficient strains. Additionally, whereas the greatest difference in visual function from baseline was an approximately 0.1 unit decrease in spatial frequency in the CD + HFD group, it is unclear whether this change would affect fitness and how it would translate to human vision. In assessing the results, the 95% confidence intervals for the ERG and GTT AUC results were wider compared to the other outcomes, which suggests that a larger sample size may have provided more robust measures.

Environmental light and circadian disruption are ubiquitous exposures with great public health relevance. As genetic or environmental perturbation of the circadian system can affect retinal differentiation and neuronal development,79–83 and ipRGCs84 and opsins are active early in retinal development, the timing of light exposure during windows of early neuronal tissue development may impact later life vision outcomes. Our findings demonstrate reduced visual function, altered retinal function, impaired glucose tolerance, and upregulated retinal microglial and macrophage markers in mice developmentally chronodisrupted via environmental light. Likewise, environmental light programming may make offspring more vulnerable to developing metabolic and immune-mediated disease, such as diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. Further studies are also necessary to fully characterize the inflammatory responses associated with CD and HFD. Overall, these findings extend the prior research and collectively support environmental light as a relevant exposure3,85 for developmental programming and DOHaD research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH-NICHD F31 HD097918 [to D.A.C.T.], NIH-NIEHS T32 ES012870 [to D.A.C.T.], NIH-NIEHS P30ES019776 [to C.J.M.], and NIH-NEI Core Grant P30EY006360) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (Rehabilitation Research and Development Senior Research Career Scientist Award RX003134 [to M.T.P.]).

Author Contributions: D. Clarkson-Townsend designed the study, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote and edited the manuscript. K. Bales stained, imaged, quantified, and analyzed samples for immunofluorescence, and contributed to writing and editing of the manuscript. C. Marsit contributed to experimental design and editing of the manuscript. M. Pardue provided experimental resources and contributed to experimental design and editing of the manuscript.

Disclosure: D.A. Clarkson-Townsend, None; K.L. Bales, None; C.J. Marsit, None; M.T. Pardue, None

References

- 1. Barker DJP. The developmental origins of adult disease. J Am Coll Nutr . 2004; 23(Suppl 6): 588S–595S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McMillen IC, Robinson JS.. Developmental origins of the metabolic syndrome: prediction, plasticity, and programming. Physiol Rev . 2005; 85(2): 571–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Varcoe TJ, Gatford KL, Kennaway DJ.. Maternal circadian rhythms and the programming of adult health and disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol . 2018; 314(2): R231–R241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jackson CR, Capozzi M, Dai H, McMahon DG.. Circadian perinatal photoperiod has enduring effects on retinal dopamine and visual function. J Neurosci . 2014; 34(13): 4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fonken LK, Nelson RJ.. Effects of light exposure at night during development. Curr Opin Behav Sci . 2016; 7: 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smarr BL, Grant AD, Perez L, Zucker I, Kriegsfeld LJ.. Maternal and early-life circadian disruption have long-lasting negative consequences on offspring development and adult behavior in mice. Sci Rep . 2017; 7(1): 3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ciarleglio CM, Axley JC, Strauss BR, Gamble KL, McMahon DG.. Perinatal photoperiod imprints the circadian clock. Nat Neurosci . 2011; 14(1): 25–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Panda S. Circadian physiology of metabolism. Science . 2016; 354(6315): 1008–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reutrakul S, Knutson KL.. Consequences of circadian disruption on cardiometabolic health. Sleep Med Clin . 2015; 10(4): 455–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shimba S, Ogawa T, Hitosugi S, et al.. Deficient of a clock gene, brain and muscle Arnt-like protein-1 (BMAL1), induces dyslipidemia and ectopic fat formation. PLoS One . 2011; 6(9): e25231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morris CJ, Yang JN, Garcia JI, et al.. Endogenous circadian system and circadian misalignment impact glucose tolerance via separate mechanisms in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2015; 112(17): E2225–E2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karatsoreos IN, Bhagat S, Bloss EB, Morrison JH, McEwen BS.. Disruption of circadian clocks has ramifications for metabolism, brain, and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2011; 108(4): 1657–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rouch I, Wild P, Ansiau D, Marquié JC.. Shiftwork experience, age and cognitive performance. Ergonomics . 2005; 48(10): 1282–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chellappa SL, Morris CJ, Scheer FAJL.. Effects of circadian misalignment on cognition in chronic shift workers. Sci Rep . 2019; 9(1): 699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Loef B, Nanlohy NM, Jacobi RHJ, et al.. Immunological effects of shift work in healthcare workers. Sci Rep . 2019; 9(1): 18220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Loef B, van Baarle D, van der Beek AJ, Sanders EAM, Bruijning-Verhagen P, Proper KI.. Shift work and respiratory infections in health-care workers. Am J Epidemiol . 2018; 188(3): 509–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mohren DC, Jansen NW, Kant IJ, Galama J, van den Brandt PA, Swaen GM.. Prevalence of common infections among employees in different work schedules. J Occup Environ Med . 2002; 44(11): 1003–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hergenhan S, Holtkamp S, Scheiermann C.. Molecular interactions between components of the circadian clock and the immune system. J Molec Biol . 2020; 432(12): 3700–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Castanon-Cervantes O, Wu M, Ehlen JC, et al.. Dysregulation of inflammatory responses by chronic circadian disruption. J Immunol . 2010; 185(10): 5796–5805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leproult R, Holmbäck U, Van Cauter E.. Circadian misalignment augments markers of insulin resistance and inflammation, independently of sleep loss. Diabetes . 2014; 63(6): 1860–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kecklund G, Axelsson J.. Health consequences of shift work and insufficient sleep. BMJ . 2016; 355: i5210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Varcoe TJ, Wight N, Voultsios A, Salkeld MD, Kennaway DJ.. Chronic phase shifts of the photoperiod throughout pregnancy programs glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in the rat. PLoS One . 2011; 6(4): e18504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. London A, Benhar I, Schwartz M.. The retina as a window to the brain—from eye research to CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurol . 2013; 9(1): 44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tosini G, Pozdeyev N, Sakamoto K, Iuvone PM.. The circadian clock system in the mammalian retina. BioEssays . 2008; 30(7): 624–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McMahon DG, Iuvone PM, Tosini G.. Circadian organization of the mammalian retina: from gene regulation to physiology and diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res . 2014; 39: 58–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Felder-Schmittbuhl M-P, Buhr ED, Dkhissi-Benyahya O, et al.. Ocular clocks: adapting mechanisms for eye functions and health. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2018; 59(12): 4856–4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baba K, Ribelayga CP, Michael Iuvone P, Tosini G. The retinal circadian clock and photoreceptor viability. Adv Exp Med Biol . 2018; 1074: 345–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hatori M, Gronfier C, Van Gelder RN, et al.. Global rise of potential health hazards caused by blue light-induced circadian disruption in modern aging societies. NPJ Aging Mech Dis . 2017; 3(1): 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lunn RM, Blask DE, Coogan AN, et al.. Health consequences of electric lighting practices in the modern world: A report on the National Toxicology Program's workshop on shift work at night, artificial light at night, and circadian disruption. Sci Total Environ . 2017; 607-608: 1073–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Winett L, Wallack L, Richardson D, Boone-Heinonen J, Messer L.. A framework to address challenges in communicating the developmental origins of health and disease. Curr Environ Health Rep . 2016; 3(3): 169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mendez N, Halabi D, Spichiger C, et al.. Gestational chronodisruption impairs circadian physiology in rat male offspring, increasing the risk of chronic disease. Endocrinology . 2016; 157(12): 4654–4668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brown LA, Hasan S, Foster RG, Peirson SN.. COMPASS: continuous open mouse phenotyping of activity and sleep status. Wellcome Open Res . 2017; 1: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schmid B, Helfrich-Förster C, Yoshii T.. A new ImageJ plug-in “ActogramJ” for chronobiological analyses. J Biol Rhythms . 2011; 26(5): 464–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Blume C, Santhi N, Schabus M.. 'nparACT' package for R: A free software tool for the non-parametric analysis of actigraphy data. MethodsX . 2016; 3: 430–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Andrikopoulos S, Blair AR, Deluca N, Fam BC, Proietto J.. Evaluating the glucose tolerance test in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metabol . 2008; 295(6): E1323–E1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sakaguchi K, Takeda K, Maeda M, et al.. Glucose area under the curve during oral glucose tolerance test as an index of glucose intolerance. Diabetol Int . 2015; 7(1): 53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mui AM, Yang V, Aung MH, et al.. Daily visual stimulation in the critical period enhances multiple aspects of vision through BDNF-mediated pathways in the mouse retina. PLoS One . 2018; 13(2): e0192435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aung MH, Kim MK, Olson DE, Thule PM, Pardue MT.. Early visual deficits in streptozotocin-induced diabetic long Evans rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2013; 54(2): 1370–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gudapati K, Singh A, Clarkson-Townsend D, Feola AJ, Allen RS.. Behavioral assessment of visual function via optomotor response and cognitive function via Y-maze in diabetic rats. J Vis Exp . 2020(164): e61806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Prusky GT, Alam NM, Beekman S, Douglas RM.. Rapid quantification of adult and developing mouse spatial vision using a virtual optomotor system. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2004; 45(12): 4611–4616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prusky GT, Alam NM, Douglas RM.. Enhancement of vision by monocular deprivation in adult mice. J Neurosci . 2006; 26(45): 11554–11561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Turner PV, Albassam MA.. Susceptibility of rats to corneal lesions after injectable anesthesia. Comp Med . 2005; 55(2): 175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Allen RS, Feola A, Motz CT, et al.. Retinal deficits precede cognitive and motor deficits in a rat model of type II diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2019; 60(1): 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aung MH, Park HN, Han MK, et al.. Dopamine deficiency contributes to early visual dysfunction in a rodent model of type 1 diabetes. J Neurosci . 2014; 34(3): 726–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Varcoe TJ, Boden MJ, Voultsios A, Salkeld MD, Rattanatray L, Kennaway DJ.. Characterisation of the maternal response to chronic phase shifts during gestation in the rat: implications for fetal metabolic programming. PLoS One . 2013; 8(1): e53800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van Alphen B, Winkelman BHJ, Frens MA.. Age- and sex-related differences in contrast sensitivity in C57Bl/6 mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2009; 50(5): 2451–2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wachtmeister L. Oscillatory potentials in the retina: what do they reveal. Prog Retin Eye Res . 1998; 17(4): 485–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wachtmeister L. Oscillatory potentials in the retina: what do they reveal. Prog Retin Eye Res . 1998; 17(4): 485–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhao L, Zabel MK, Wang X, et al.. Microglial phagocytosis of living photoreceptors contributes to inherited retinal degeneration. EMBO Mol Med . 2015; 7(9): 1179–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gupta N, Brown KE, Milam AH.. Activated microglia in human retinitis pigmentosa, late-onset retinal degeneration, and age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res . 2003; 76(4): 463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rashid K, Akhtar-Schaefer I, Langmann T.. Microglia in retinal degeneration. Front Immunol . 2019; 10: 1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mendez N, Torres-Farfan C, Salazar E, et al.. Fetal programming of renal dysfunction and high blood pressure by chronodisruption. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) . 2019; 10: 362–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hong J, Stubbins RE, Smith RR, Harvey AE, Núñez NP.. Differential susceptibility to obesity between male, female and ovariectomized female mice. Nutr J . 2009; 8: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Parks BW, Sallam T, Mehrabian M, et al.. Genetic architecture of insulin resistance in the mouse. Cell Metab . 2015; 21(2): 334–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yang Y, Smith DL Jr., Keating KD, Allison DB, Nagy TR. Variations in body weight, food intake and body composition after long-term high-fat diet feeding in C57BL/6J mice. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2014; 22(10): 2147–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Le May C, Chu K, Hu M, et al.. Estrogens protect pancreatic beta-cells from apoptosis and prevent insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2006; 103(24): 9232–9237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhu L, Zou F, Yang Y, et al.. Estrogens prevent metabolic dysfunctions induced by circadian disruptions in female mice. Endocrinology . 2015; 156(6): 2114–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Maniu A, Aberdeen GW, Lynch TJ, et al.. Estrogen deprivation in primate pregnancy leads to insulin resistance in offspring. J Endocrinol . 2016; 230(2): 171–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Clarkson-Townsend DA, Douglass AJ, Singh A, Allen RS, Uwaifo IN, Pardue MT.. Impacts of high fat diet on ocular outcomes in rodent models of visual disease. Exp Eye Res . 2021; 204: 108440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Atawia RT, Bunch KL, Fouda AY, et al.. Role of arginase 2 in murine retinopathy associated with Western diet-induced obesity. J Clin Med . 2020; 9(2): 317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kwan CC, Lee HE, Schwartz G, Fawzi AA.. Acute hyperglycemia reverses neurovascular coupling during dark to light adaptation in healthy subjects on optical coherence tomography angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2020; 61(4): 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schiller PH. Parallel information processing channels created in the retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2010; 107(40): 17087–17094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Giolli RA, Blanks RH, Lui F.. The accessory optic system: basic organization with an update on connectivity, neurochemistry, and function. Prog Brain Res . 2006; 151: 407–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kowluru RA, Chan P-S.. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy. Exp Diabetes Res . 2007; 2007: 43603–43603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Joyal J-S, Sun Y, Gantner ML, et al.. Retinal lipid and glucose metabolism dictates angiogenesis through the lipid sensor Ffar1. Nat Med . 2016; 22(4): 439–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Collins KH, Herzog W, Reimer RA, Reno CR, Heard BJ, Hart DA.. Diet-induced obesity leads to pro-inflammatory alterations to the vitreous humour of the eye in a rat model. Inflamm Res . 2018; 67(2): 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mancini JE, Ortiz G, Croxatto JO, Gallo JE.. Retinal upregulation of inflammatory and proangiogenic markers in a model of neonatal diabetic rats fed on a high-fat-diet. BMC Ophthalmol . 2013; 13: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tuzcu M, Orhan C, Muz OE, Sahin N, Juturu V, Sahin K.. Lutein and zeaxanthin isomers modulates lipid metabolism and the inflammatory state of retina in obesity-induced high-fat diet rodent model. BMC Ophthalmol . 2017; 17(1): 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lee JJ, Wang PW, Yang IH, et al.. High-fat diet induces toll-like receptor 4-dependent macrophage/microglial cell activation and retinal impairment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 2015; 56(5): 3041–3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rajagopal R, Bligard GW, Zhang S, Yin L, Lukasiewicz P, Semenkovich CF.. Functional deficits precede structural lesions in mice with high-fat diet-induced diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes . 2016; 65(4): 1072–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zeng HY, Green WR, Tso MO.. Microglial activation in human diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol . 2008; 126(2): 227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Krady JK, Basu A, Allen CM, et al.. Minocycline reduces proinflammatory cytokine expression, microglial activation, and caspase-3 activation in a rodent model of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes . 2005; 54(5): 1559–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ibrahim AS, El-Remessy AB, Matragoon S, et al.. Retinal microglial activation and inflammation induced by amadori-glycated albumin in a rat model of diabetes. Diabetes . 2011; 60(4): 1122–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Oishi Y, Hayashi S, Isagawa T, et al.. Bmal1 regulates inflammatory responses in macrophages by modulating enhancer RNA transcription. Sci Rep . 2017; 7(1): 7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Orozco-Solis R, Aguilar-Arnal L.. Circadian regulation of immunity through epigenetic mechanisms. Front Cell Infect Microbiol . 2020; 10: 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Scheiermann C, Gibbs J, Ince L, Loudon A.. Clocking in to immunity. Nat Rev Immunol . 2018; 18(7): 423–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Griffin P, Dimitry JM, Sheehan PW, et al.. Circadian clock protein Rev-erbα regulates neuroinflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2019; 116(11): 5102–5107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Musiek ES, Lim MM, Yang G, et al.. Circadian clock proteins regulate neuronal redox homeostasis and neurodegeneration. J Clin Invest . 2013; 123(12): 5389–5400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rao S, Chun C, Fan J, et al.. A direct and melanopsin-dependent fetal light response regulates mouse eye development. Nature . 2013; 494(7436): 243–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sawant OB, Horton AM, Zucaro OF, et al.. The circadian clock gene bmal1 controls thyroid hormone-mediated spectral identity and cone photoreceptor function. Cell Rep . 2017; 21(3): 692–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Baba K, Piano I, Lyuboslavsky P, et al.. Removal of clock gene Bmal1 from the retina affects retinal development and accelerates cone photoreceptor degeneration during aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2018; 115(51): 13099–13104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sawant OB, Jidigam VK, Fuller RD, et al.. The circadian clock gene Bmal1 is required to control the timing of retinal neurogenesis and lamination of Müller glia in the mouse retina. FASEB J . 2019; 33(8): 8745–8758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Noda M, Iwamoto I, Tabata H, Yamagata T, Ito H, Nagata K-I.. Role of Per3, a circadian clock gene, in embryonic development of mouse cerebral cortex. Sci Rep . 2019; 9(1): 5874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lo Giudice Q, Leleu M, La Manno G, Fabre PJ. Single-cell transcriptional logic of cell-fate specification and axon guidance in early-born retinal neurons. Development . 2019; 146(17): dev178103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Varcoe TJ. Timing is everything: maternal circadian rhythms and the developmental origins of health and disease. J Physiol . 2018; 596(23): 5493–5494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.