Abstract

Background

To systematically review the evidence published in systematic reviews (SR) on the health impact of staying at home, social distancing and lockdown measures. We followed a systematic review approach, in line with PRISMA guidelines.

Methods

In October 2020, we searched the databases Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Ovid Medline, Ovid Embase and Web of Science, using a pre-defined search strategy.

Results

The literature search yielded an initial list of 2172 records. After screening of titles and abstracts, followed by full-text screening, 51 articles were retained and included in the analysis. All of them referred to the first wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. The direct health impact that was covered in the greatest number (25) of SR related to mental health, followed by 13 SR on healthcare delivery and 12 on infection control. The predominant areas of indirect health impacts covered by the included studies relate to the economic and social impacts. Only three articles mentioned the negative impact on education.

Conclusions

The focus of SR so far has been uneven, with mental health receiving the most attention. The impact of measures to contain the spread of the virus can be direct and indirect, having both intended and unintended consequences.

Highlights

This article provides a snapshot of systematic reviews published by October 2020.

Most of the emphasis has been on the mental health impact of policy measures.

The impact on health care delivery and infection control was explored in fewer studies.

Other policy areas and social determinants of health had hardly been studied in systematic reviews.

The impact of policy measures on health can be direct and indirect.

Keywords: COVID-19, health impact, lockdown, social distancing, staying at home

Introduction

In response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, governments worldwide adopted policies that aimed to reduce transmission, culminating in March and April 2020 in many countries in staying at home and physical (or ‘social’) distancing measures, often referred to as ‘lockdown’. While these measures helped to bring down the number of new infections, gaining valuable time for the health sector to shore up its capacity and expertise for dealing with infected patients, it has become clear that the policy response had wide-ranging impacts on the health and well-being of populations across all sectors of society and affecting all health determinants.

Faced with new waves of infections in autumn 2020 and winter 2020/2021 and the imposition of new lockdowns in many countries, it is important to understand the positive and negative impacts of lockdowns on the health and well-being of populations to inform future policy responses.

A Health Impact Assessment conducted by Public Health Wales April–May 2020 found that there was a scarcity of academic peer-reviewed research literature regarding the impacts of prolonged quarantine periods and social distancing on health and well-being.14 However, the academic literature on COVID-19 is evolving rapidly and so a renewed assessment of the academic literature was appropriate.

The overarching aim of this study was to systematically review the evidence published in systematic reviews on the health impact of staying at home, social distancing and lockdown measures.

Methods

A systematic review of systematic reviews was conducted following the Prepared Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.15 Relevant publications were identified by systematically searching the scientific literature, with the search undertaken on 20 October 2020. We searched the scientific databases Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Ovid Medline, Ovid Embase and Web of Science, using a pre-defined search strategy (detailed search strategies are provided in the Supplementary material).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection were defined a priori, after piloting them on a sample of 70 articles. Articles were included if they were published in English, were systematic reviews and focused on the health impact of staying at home, social distancing and lockdown measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic or other pandemics. There was no limitation set on the date of publication or the country of study implementation.

Articles published in languages other than English, not concerned with humans, not following a systematic review study design, or not concerned with the health impact of measures were excluded.

Identified studies were reviewed independently for eligibility in a two-step process: a first screen was performed on title and abstract, followed by the screening of full texts. Data were extracted using a standardized data extraction spreadsheet. In cases of doubt, studies were discussed within the research group and consensus reached. Because of the heterogeneity of included studies, no meta-analysis could be undertaken, and the results of our systematic review are presented in the form of a narrative synthesis.

Results

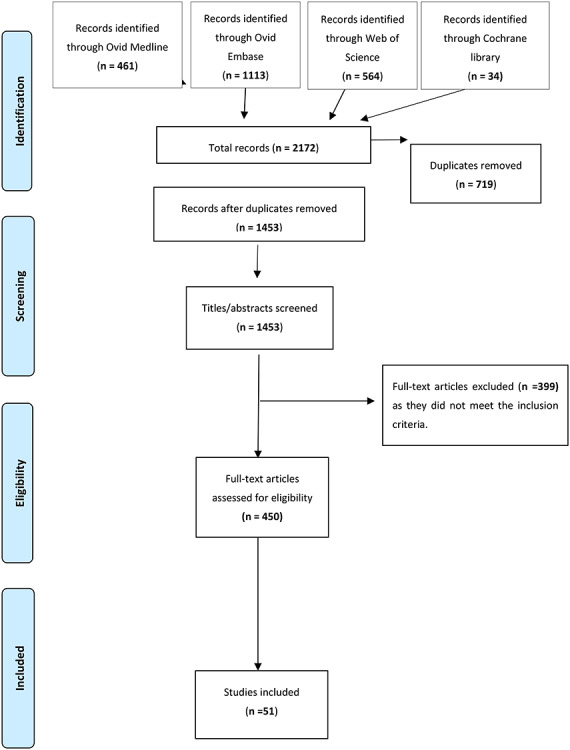

The literature search yielded an initial list of 2172 records that provided 450 relevant articles after the first screening of title and abstract. Papers were screened and selected, as illustrated in Fig. 1. After the second screening based on full texts, 51 articles were retained.1–13,16–53

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of systematic article selection.

General description of included articles

The overall characteristics of the articles included in the systematic review are shown in Table 1. All of them referred to the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. April and March 2020 represent the time limits for almost half of the systematic reviews included (n = 25). Overall, eight systematic reviews were performed with a meta-analysis.3,5,6,24,29,33,38,44 Almost one third of articles inclu-ded (n = 16) describes other outbreaks or pandemics in addition to the COVID-19 pandemic, including Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Influenza A (H1N1), Ebola, Chikungunya, Zika, Multiple drug resistance (MDR) bacteria, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).17,21–23,25,26,29–31,34,37,41,42,49–51

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the studies included

| Reference | Aim | Country/ies | Study population | Type of setting | Type of lockdown measure/s | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdo, C., et al. (2020) | To perform a systematic review of the literature regarding the consequences of COVID-19 infection in terms of domestic violence and substance abuse, and compare incidences found | ● Poland ● England ● Saint Louis |

● Substance abusers ● Victims of violence |

● Home-based setting | ● Social isolation ● Quarantine |

● Social distancing and quarantines might be an additional contributor to the aggravation of substance abuse and increased domestic violence |

| Andrenelli, E., et al. (2020) | To provide the rehabilitation community with updates on the latest scientific literature on rehabilitation needs due to COVID-19 | ● Italy ● China ● Singapore ● Spain ● USA |

● COVID-19 patients ● Subjects in need of rehabilitation interventions and rehabilitation professionals ● People quarantined at home or with restricted mobility due to the lockdown |

● Acute care wards ● Inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation facilities ● Home-based setting |

● Quarantine ● Restrictions of health services: rescheduling non-urgent outpatient visits and reducing the so-called ‘non-essential’ activities (also including consultations and rehabilitation intervention delivery), repurposing non-intensive care unit wards as intensive care units, restricting access to the hospital and reduce the moving of patients in the hospital, avoiding moving vulnerable patients within the hospital |

● Patients admitted to the hospital risk of sequelae of prolonged prone positioning during mechanical ventilation ● Patients in the home environment: risk of frailty, sarcopenia and dementia and the psychological effects of quarantine |

| Araujo, L. A. D., et al. (2020) | To examine the impact of epidemics or social restriction on mental and developmental health in parents and children/adolescents | ● USA ● China ● England ● South Africa ● Sierra Leone ● Nigeria |

● Parents ● Children ● Adolescents |

● Home-based setting ● School |

● Social isolation ● Lockdown in general ● School closures |

● School closures: some studies using models indicate divergent results on the effectiveness of closing schools to control COVID-19. Loss in the teaching/learning and socialization processes. In addition, a number of public policies take place in schools including programs on: health food, personal hygiene, sports, citizenship incentives and others ● Quarantine: was linked to anxiety, stress and depression and to stress in parents and children. It can become risk factors that threaten child growth and development ● Other effects: impact on education |

| Banerjee, D., et al. (2020) | To assess the impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on psychological health/well-being in the South-Asian countries | ● South-Asian countries | ● General population (age group of 18–60 years) ● Vulnerable groups ● Healthcare workers ● people with pre-existing psychiatric conditions |

● Home-based setting | ● Social isolation ● Isolation |

● Isolation: people in isolation are at the highest risk for psychiatric comorbidities ● Isolation and social isolation: elderly staying alone or in isolation and the migrant workers have often been deprived of their basic living amenities making them doubly vulnerable to the health risks of the pandemics and its social effects ● COVID-19 and lockdown: are linked to increased prevalence of depression, anxiety, sleep and alcohol use disorders in the general population ● People with pre-existing psychiatric conditions might be at increased risk for the infection due to lack of supervision and inadequate compliance to precautionary measures |

| Barello, S., et al. (2020) | to assess the available literature on perceived stress and psychological responses to pandemics in Health Care Workers | ● Australia ● Canada ● China ● Greece ● Hong Kong ● Japan ● Mexico ● Saudi Arabia ● Singapore ● South Korea ● Taiwan |

● Health care workers ● Medical residents |

● Home-based setting ● Work setting |

● Social isolation ● Quarantine |

● Social isolation: may have a negative psychosocial impact ● Quarantine: being quarantined: is associated to work-related stress and burnout |

| Bentlage, E., et al. (2020) | to provide practical recommendations for maintaining active lifestyles during pandemics | n.s. | ● General population ● Children ● Vulnerable populations: older adults, people with psychiatric patients or other health issues |

● Home-based setting | ● Social isolation ● Lockdown in general |

● Social isolation increase physical inactivity and the global burden of cardiovascular disease. In psychiatric patients may have negative effects on mental health ● lockdown in children: during the lockdown fruit intake increased. Sugary drink, red meat and potato chip intakes increased as well. The time for sports participation decreased sleep time and screen time increased. Depending on duration of the lockdown, it may have negative effects on adiposity levels in children ● lockdown in elderly: the reduction in social participation and physical activity during home confinement is of serious concern for older adults, as they are typically more inactive more prone to chronic disease |

| Brooks, S. K., et al. (2020) | to explore the psychological impact of quarantine on mental health and psychological wellbeing, and the factors that contribute to, or mitigate, these effects | ● Australia ● Canada ● China ● Liberia ● Hong Kong ● Sierra Leone ● Senegal ● South Korea ● Taiwan ● USA ● Sweden |

● General population ● School community members ● College students ● Health-care workers ● Residents ● Parents |

● Home-based setting ● Work setting |

● Isolation ● Quarantine |

● Prequarantine: the predictors of psychological impact include: having a history of psychiatric illness was associated with experiencing anxiety and anger 4–6 months after quarantine. Healthcare workers who experienced quarantine had more severe symptoms of post-traumatic stress than the general population. Healthcare workers also felt stigmatization, exhibited more avoidance behaviours after quarantine, reported greater lost income and were consistently more affected psychologically. Conversely, one study suggested that healthcare worker status was not associated with psychological outcomes. ● Stressors during quarantine: duration of quarantine, fears of infection, frustration and boredom, inadequate supplies, inadequate information ● Stressors post quarantine: finances, stigma ● other effects: lost income, Inadequate supplies, Inadequate information |

| Brown, E., et al. (2020) | to assess the impact of epidemic and pandemics on psychosis | ● Taiwan ● Hong Kong ● China ● Israel ● Sierra Leone ● South Korea ● Australia ● USA ● Malaysia |

● General population with any disease ● Psychiatric patients ● Patients infected with a virus |

● Home-based setting ● Work setting |

● Isolation ● Quarantine |

● Social isolation: incident cases of psychosis in patients not infected with a virus reported a increase in incident cases of schizophrenia attributed to the psychosocial stress and physical distancing measures associated with the COVID- 19 outbreak. Psychosis may reduce the motivation to to comply with infection control and with physical distancing measures patients with SARS with psychiatric complications ● patients with infection may develop psychiatric complications due to due to total social isolation |

| Burns, J., et al. (2020) | to assess the effectiveness of travel-related control measures during the COVID-19 pandemic on infectious disease and screening-related outcomes | multiple locations not specified | ● Travellers | ● travel | ● Travel restrictions:—reducing cross-border travel—Screening at borders with or without quarantine—Quarantine of travellers | ● Some travel-related control measures during the COVID-19 pandemic may have a positive impact on infectious disease outcomes23.—Travel restrictions may limit the spread of disease across national borders—Entry and exit symptom screening measures on their own are not likely to be effective in detecting a meaningful proportion of cases to prevent seeding new cases within the protected region, combined with subsequent quarantine, observation and PCR testing, the effectiveness is likely to improve23.—There was insufficient evidence to draw firm conclusions about the effectiveness of travel-related quarantine on its own23. In addition to their intended positive impact on infectious disease dynamics, travel-related control measures may also have negative health impacts, notably the well-known side effects of quarantine and isolation on mental health. Other effects: quarantine and isolation have far-reaching economic, social, legal, ethical and political implications |

| Burrell, A., et al. (2020) | to synthesise evidence regarding the effect of funeral practices on bereaved friends’ and relatives’ mental health and bereavement outcomes | ● Australia ● USA ● Netherlands ● Rwanda ● Turkey ● Hong Kong |

● General population | ● Home-based setting ● Community environments |

● restrictions to funeral practices | ● Current evidence regarding the effect of funeral practices on bereaved relatives' mental health and bereavement outcomes is inconclusive. Five observational studies found benefits from funeral participation while six did not24. |

| Cabarkapa, S., et al. (2020) | to investigate the psychological impact on HCWs facing epidemics or pandemics | ● Canada ● China ● Hong Kong ● Iran ● Italy ● Pakistan ● Poland ● Saudi Arabia ● Singapore ● South Korea ● Spain ● Taiwan ● Turkey ● USA |

● Health-care workers | ● Inpatient and outpatient ● Home-based setting |

● Isolation ● Quarantine |

● Quarantine: hospital employees had a high degree of post-traumatic stress symptoms which were strongly associated with exposure to SARS, quarantine and a relative or friend acquiring SARS. They also had the greatest risk for PTSD symptoms one-month later, and, this risk was increased even after home quarantine. Home quarantined HCWs had poorer sleep and a heightened degree of numbness than those who were not quarantined. ● Social isolation: a lack of family support and social isolation had a negative psychological impact on nurses who chose to isolate away from their families |

| Carmassi, C., et al. (2020) | To systematically review the studies investigating the potential risk and resilience factors for the development of PTSD symptoms in HCWs who faced the two major Coronavirus outbreaks that occurred worldwide in the last two decades, namely the SARS and the MERS, as well as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic | Multiple locations not specified | ● Health-care workers | ● Home-based setting ● Community environment |

● Quarantine ● Social isolation |

● Quarantine: three SARS studies and one on the MERS outbreak consistently reported high levels of PTSS among HCWs who had been quarantined. They sufferd also acute stress disorder, and quarantine was the most frequently associated factor. Similar findings emerged from a Canadian SARS study in which quarantined HCWs reported more PTSS than non-HCWs quarantined individuals. Moreover, in a study on MERS outbreak observed that quarantined HCWs had a higher risk of developing PTSS which persisted over time, particularly sleep and numbness-related symptoms ● Social isolation: social isolation and separation from family was found to be associated with higher rates of PTSS in SARS outbreak |

| Ceravolo, M. G., et al. (2020) | To provide the rehabilitation community with updates on the latest scientific literature on rehabilitation needs due to COVID-19 | ● Italy ● China ● Singapore ● China ● Spain ● USA |

● People experiencing disability due to COVID-19 | ● Home-based setting ● Community environment ● Outpatient level |

● Social restrictions ● Quarantine |

● Social restrictions and quarantine: the evidence suggest risk of frailty, sarcopenia, cognitive decline and depression of people quarantined at home or with restricted mobility due to the lockdown |

| Chandana Kumari, V. B., et al. (2020) | To report the status of COVID-19 pandemic, including its origin and transmission and to highlight the available therapeutics, preventive and control measures | ● Multiple locations not specified | ● General population | ● Home-based setting ● Community environment |

● Quarantine ● City lockdown |

● Quarantine: is one of the most misunderstood and feared methods of controlling COVID-19, because it may affect both infected and non-infected individuals with psychological, economical and emotional complications such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, insomnia, mood swings. From the economical point of view, quarantine reduces the productivity, hence minimalizes the economic growth27. Another study showed that quarantine strategies are more effective than traffic restrictions. According to them, it is estimated to reduce the number of cases by 89.7%. Quarantine can be the best self-preventive method that can be practiced at community and national level ● City lockdown: was proved to be effective when a study reported 72% drop in the number of infected people. They also suggested that, postponing lockdown would worsen the situation by five times ● Other effects: Quarantine reduces the productivity, hence minimalizes the economic growth |

| Chaudhry, H., et al. (2020) | To assess the levels of patient and surgeon satisfaction with the use of telemedicine as a tool for orthopaedic care delivery and to explore eventual differences in patient-reported outcomes between telemedicine visits and in-person visits | multiple locations not specified | ● Patients with Orthopaedic needs ● Orthopaedics |

● Telemedicine | ● Restrictions of health services ● Lockdown in general |

● Reduction in inpatients and outpatients orthopaedic care and increase of remote orthopaedic care |

| Ferreira, C. H. J., et al. | to offer guidance regarding physiotherapy in urogynaecology during the COVID-19 pandemic | multiple locations not specified | ● Urogynecologist patient with Physiotherapy needs | ● Home-based setting ● Community environment ● Outpatient level |

● Social distancing ● Restrictions of health services |

● Social distancing: during the pandemic it could increase PFD-related suffering and other morbidities affecting women’s quality of life because of multiple factors such as increased obesity, physical inactivity, stress and problems to access health care, including physiotherapy ● An early initiation of the rehabilitation process in urogynaecology is considered a crucial factor for women’s health |

| Fouche, A., et al. (2020) | To investigate how C-19 legislation enabled, or constrained, South African children’s protection from abuse and neglect and appraises the findings from a social- ecological resilience perspective with the aim of advancing child protection in times of emergency | South Africa | ● General population with a focus on children | ● Home-based setting ● Community environment |

● Strict lockdown | ● The regulations and directives that informed South Africa's strict lockdown offered three protective pathways. They (i) limited C-19 contagion and championed physical health; (ii) ensured uninterrupted protection (legal and statutory) for children at risk of abuse; and (iii) advanced social protection measures available to disadvantaged households28. ● Other effects: food insecurity, financial insecurity |

| Gao, Y. L., et al. (2020) | To explore the role and potential of telemedicine during the COVID-19, SARS and MERS outbreaks | China | ● Patients with pandemic infection ● Suspected COVID-19 or SARS patients ● General population during pandemics |

● Telemedicine | ● Restrictions of health services ● Lockdown in general |

● Remote medical treatment can reduce the spread of the virus and the unnecessary hospital visits during the outbreak and the accumulation of people in the hospital, accelerate the patients’ access to professional advice in time and alleviate anxiousness among the members of public |

| Grimes, C. L., et al. (2020) | To conduct an expedited review of the evidence and to provide guidance for management of common outpatient urogynecologic conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic | ● China ● Taiwan ● USA ● UK ● Hong Kong ● Spain |

● Urogynecologist patient principally female | ● Telemedicine ● Outpatient level |

● Restrictions of health services ● Lockdown in general |

● Restrictions of health services: behavioural, medical and conservative management will be valuable as first-line virtual treatments. ● Certain situations will require different treatments in the virtual setting while others will require an in person visit despite the risks of COVID-19 transmission6 |

| Haider, Z., et al. (2020) | To explore evidence for telemedicine in orthopaedics to determine its advantages, validity, effectiveness and utilization | ● Multiple locations not specified | ● Orthopaedic patients | ● Telemedicine | ● Restrictions of health services ● Lockdown in general |

● Orthopaedic studies revealed high patient satisfaction with telemedicine for convenience, less waiting and travelling time. Telemedicine was cost effective particularly if patients had to travel long distances, required hospital transport or time off work. No clinically significant differences were found in patient examination nor measurement of patient-reported outcome measures. Telemedicine was reported to be a safe method of consultation.7 |

| Henssler, J., et al. (2020) | To assess the psychological effects in both quarantined and isolated persons compared to non-quarantined and non-isolated persons | ● Taiwan ● USA ● UK ● Hong Kong ● Canada ● China ● South Korea ● Turkey ● France ● Singapore ● Spain ● NL ● Australia |

● General population ● Healthcare workers ● Students |

● Home-based setting ● Community environment ● Inpatient level |

● Isolation ● Quarantine |

● Isolation and quarantine: individuals experiencing isolation or quarantine were at increased risk for adverse mental health outcomes, particularly after containment duration of 1 week or longer. Effect sizes were summarized for depressive disorders, anxiety disorders and stress-related disorders. Elevated levels of anger were reported most consistently. There is compelling evidence for adverse mental health effects of isolation and quarantine, in particular depression, anxiety, stress-related disorders, and anger29 |

| Hossain, M. M., et al. (2020) | To synthesize the evidence on mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for preventing infectious diseases | ● UK ● USA ● Hong Kong ● Canada ● Sweden ● Netherlands ● New Zealand ● Ireland ● Brazil ● China Taiwan ● Australia ● Korea ● Liberia ● Sierra Leone ● Senegal ● Spain ● Turkey, ● Singapore ● France |

● Patients with a pandemic infection ● Providers ● Students ● Institutional stakeholders ● Community members |

● Home-based setting ● Community environment ● Inpatient level |

● Isolation ● Quarantine |

● Isolation and quarantine: it was reported a high burden of mental health problems among patients, informal caregivers and healthcare providers who experienced quarantine or isolation. Prevalent mental health problems among the affected individuals include depression, anxiety, mood disorders, psychological distress, posttraumatic stress disorder, insomnia, fear, stigmatization, low self-esteem, lack of self-control, and other adverse mental health outcomes30 |

| Imran, N., et al. (2020) | To assess the impact of quarantine on mental health of children and adolescents, and proposes measures to improve psychological outcomes of isolation | ● Canada ● Norway ● Mexico ● Finland ● Sierra Leone ● Denmark ● USA ● China ● Italy ● Spain |

● Parents and siblings ● Parents ● Close informants from NGO’s ● Social service ● Caregivers |

● Home-based setting ● Community environment |

● Isolation ● Quarantine |

● Isolation: the seven studies before onset of COVID 19 about psychological impact of quarantine in children have reported isolation, social exclusion stigma and fear among the children. Acute stress disorder, adjustment disorder, grief and post-traumatic stress disorder were the most frequent diseases ● Quarantine: three studies during the COVID-19 pandemic reported restlessness, irritability, anxiety, clinginess and inattention with increased screen time in children during quarantine ● Other effects: the provision of inadequate information, financial losses, and stigma were some of the factors identified with stress in quarantined |

| Lahiri, A., et al. (2020) | To identify the different public health interventions (NPIs) and to understand their proposed effectiveness (as per prediction models), under different assumptions, among Indian population | ● India | ● General population | ● Home-based setting ● Community environment |

● Social distances ● Lockdown and strict lockdown ● Quarantine ● Isolation ● Travels restrictions |

● Social distances, lockdown and strict lockdown, quarantine, isolation, travels restrictions: although there is mathematical rationality behind implementation of social distancing measures including lockdown, this study also emphasised the importance of other associated measures like increasing tests and increasing the number of hospital and ICU beds. The later components are particularly important during the social mixing period to be observed after lifting of lockdown32. |

| Lasheras, I., et al. (2020) | To investigate the prevalence of anxiety in medical students during this pandemic | ● China ● Iran ● UAEs ● Brazil ● India ● China |

● Medical students | ● Home-based setting ● Community environment |

● Lockdown ● Strict quarantine regulations |

● Lockdown may prevent students from engaging in other beneficial activities such as exercise which, together with peer support, has been shown to be the most effective non-pharmacological therapy in the college and university student population and was found to alleviate general negative emotions in college students specifically during the pandemic ● Strict quarantine regulations and movement control may also limit access to counselling services, leading to a worsening of previously established anxiety disorders and cause of economic losses ● Other effects: worry about the economic influences, worry about academic delays, impacts on daily life and curricular factors |

| Leaune, E., et al. (2020) | To systematically review the evidence on the association between emerging viral disease outbreaks and suicidal ideation and behaviours | ● UK ● USA ● Ireland ● France ● Taiwan ● Hong Kong ● Guinea |

● General population ● patients with an infection ● Visitors of the emergency Department |

● Home-based setting ● Community environment |

● Quarantine | ● Quarantine: psychosocial factors such as the fear of being infected by the virus or social isolation related to quarantine measures, the disruption of normal social life are the most prominent factors associated with deaths by suicide during emerging viral disease outbreaks (EVDOs). Overall, the authors found scarce and weak evidence for an increased risk of deaths by suicide during EVDOs |

| Lenferink, L. I. M., et al. (2020) | To review the literature for clinical trials examining the effects of online EMDR for PTSD | ● Australia | ● Adult patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) | ● Telemedicine | ● Restrictions of health services ● Lockdown in general |

● Only one trial was identified. That uncontrolled open trial showed promising results |

| Leochico, C. F. D., et al. (2020) | To determine the challenges faced by telerehabilitation in the Philippines | ● Philippines | ● Patients with rehabilitation needs ● Health care workers ● policymakers |

● Telemedicine | ● Restrictions of health services ● Lockdown in general |

● Data are scant on telerehabilitation in the Philippines. Local efforts can focus on exploring or addressing the most pressing human, organizational, and technical challenges to the emergence of telerehabilitation in the country.9 ● Other effects: the study found 53 unique, albeit interrelated, challenges in the literature (e.g.: Apprehensions on convenience, costs, sustainability, and privacy) that could affect the emergence of telerehabilitation |

| Lin, Y. F., et al. (2020) | To summarize mathematical models to understand and predict the infectiousness of COVID-19 to inform and to manage the current outbreak | ● China | ● General population | ● Home-based setting ● Community environment |

● City lockdown ● Quarantine |

● City lockdown and quarantine: The overall median basic reproduction number (R0) was 3.77 dropped to a controlled reproduction number (Rc) of 1.88 after city lockdown. Other recently implemented public health measures beyond citywide lockdowns, including contact tracing, intensification of screening, quarantine of infected individuals, and mask utilisation, may also be contributing to the containment of COVID-19. Future models should attempt to capture the impact of these additional interventions on COVID-19 transmission.35 |

| Lithander, F. E., et al. (2020) | To provide a rapid overview of the COVID-19 literature, with a specific focus on older adults | ● China | ● Older adults COVID-19 positive admitted to hospitals ● Older adults in the general population ● Healthcare workers |

● Home-based setting ● Work setting ● Inpatient level |

● Isolation ● Quarantine ● Social distancing ● Community containment |

● Isolation and quarantine: classic public health measures are required to reduce and prevent person- to-person transmission, namely isolation and quarantine, social distancing and community containment. Isolation and quarantine can be effective tools for preventing the transmission if early detection of cases is possible. ● Social distancing and Community containment: stricter measures of ‘social distancing’ and even more stringent ‘community containment’ may be deployed if community transmission, without obvious linkages between cases, is evident. Evidence suggests that social distancing policies could have important negative consequences, particularly if in place for an extended period. Loneliness caused by social isolation has been associated with impaired cognitive function in older adults.36 |

| Loades, M. E., et al. (2020) | To establish what is known about how loneliness and disease containment measures impact on the mental health in children and adolescents | ● USA ● Canada ● Mexico ● Belgium ● Denmark ● China ● UK ● Netherlands |

● Children ● Adolescents ● Young adult |

● Home-based setting ● Community environment |

● Isolation ● Quarantine ● Social distancing |

● Social isolation: children and adolescents are probably more likely to experience high rates of depression and most likely anxiety during and after enforced isolation ends.37 This may increase as enforced isolation continues. Most studies reported moderate to large correlations between depressive symptoms and loneliness and or social isolation, most included a measure of depressive symptoms. Small to moderate associations between anxiety and loneliness/social isolation. One study found a small association between panic and loneliness and social isolation. [...] Positive associations were also reported between social isolation/loneliness and suicidal ideation, self-harm and eating disorder risk behaviours.37 ● Isolation: health problems after enforced isolation and quarantine in previous pandemics children who had experienced enforced isolation or quarantine were five times more likely to require mental health service input and experienced higher levels of posttraumatic stress |

| Luo, M., et al. (2020) | To evaluate the psychological and mental impacts of COVID-19. Secondary aims was to explore factors associated with higher psychological distress | ● China ● India ● Singapore ● Italy ● Iran ● Turkey ● Spain |

● Healthcare workers ● General population ● Patients with higher COVID-19 risk (cancer, diabetes, Parkinson’s) ● Caregivers |

● Home-based setting ● Work setting ● Inpatient level |

● Social isolation | ● Social isolation: is a risk factor of heavier psychological burden together with being women, being nurses, having high risks of contracting COVID-19, having lower socioeconomic status, and spending longer time watching COVID-19 related news. Protective factors identified include having sufficient medical resources, having up-to-date and accurate health information and taking precautionary measures |

| Melo-Oliveira, M. E., et al. (2020) | To summarize effects of the COVID-19 in the Quality of life (QoL) of the studied populations | ● Italy ● China ● Vietnam ● Saudi Arabia |

● Patients affected by primary antibody deficiencies ● Residents ● People from endemic and no endemic regions ● Individuals with COVID-19 |

● Home-based setting ● Community environment |

● Quarantine | ● Quarantine: there was a reduction of the mean wellbeing scores during the quarantine, compared to before evaluated, stratifying by age, a trend toward older ages was found in the desire for parenthood before and during the COVID-19 pandemic was found. The pandemic is changing the desire for parenthood, but It is unknown if this will determine a substantial modification of birth rate |

| Murphy, E. P., et al. (2020) | To describe the adverse outcomes, the cost reductions and the efficiencies associated with the virtual fracture clinic model | n.s. | ● Adults and children treated for injuries by a virtual clinic model | ● Telemedicine | ● Restrictions of health services ● Lockdown in general |

● Six studies reported adverse outcomes, while others variation in the efficiency. In challenging settings, during the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual fracture clinics are tools that can help to treat patients remotely, using agreed protocols. |

| Noone, C., et al. (2020) | To assess the effectiveness of video calls for reducing social isolation and loneliness in older adults. The review also sought to address the effectiveness of video calls on reducing symptoms of depression and improving quality of life | n.s. | ● Elderly living in nursing homes | ● Nursing homes | ● Social distancing | ● Social distancing: older people suffer of social distancing due to isolation at home, confinement into: nursing homes, rooms in old age homes and frail care units. The evidence was limited because few studies with a small number of participants, and with unreliable methods were included. All of the participants were in nursing homes, so our findings may not apply to older people living in other places, such as their homes |

| Nussbaumer-Streit, B., et al. (2020) | ● To assess the effects of quarantine (alone or in combination with other measures) of individuals who had contact with confirmed cases of COVID-19, who travelled from countries with a declared outbreak, or who live in regions with high transmission of the disease | Studies simulating outbreak scenarios in: ● China ● UK ● South Korea ● Taiwan ● Canada ● Hong Kong ● Japan ● Singapore |

● Individuals who had contact with confirmed cases of COVID-19 ● Individuals who travelled from countries with a declared outbreak ● Individuals who live in regions with high transmission of the disease |

● Home-based setting ● Community environments ● Travels ● School |

• School closure • Isolation • Quarantine • Social distance • Quarantine of travellers |

• Simulated quarantine avoided 44% to 81% incident cases and 31% to 63% of deaths if compared to any measures. Very low-certainty evidence suggests that the earlier quarantine measures are implemented, the greater the cost savings.41 • Quarantine of travellers: very low-certainty evidence identified that the effect of quarantine of travellers from a country with a declared outbreak on reducing incidence and deaths was small. • Others: wen the models combined quarantine with other prevention and control measures, including school closures, travel restrictions and social distancing, the models demonstrated a larger effect on the reduction of new cases, transmissions and deaths than individual measures alone |

| Park, M., et al. (2020) | To inform policymakers and leaders in formulating management guidelines and to provide directions for future research on systematic review of the literature available on transmission dynamics, severity, susceptibility and control measures | ● China ● South Korea ● Hong Kong |

● Individuals who had contact with confirmed cases ● confirmed cases ● Individuals who travelled from countries with a declared outbreak ● Individuals who live in regions with high transmission of the disease |

● Home-based setting ● Community environments ● Travels ● workplace ● School closure |

● Quarantine ● Travel restrictions ● Airport screening for travellers ● School closure ● Workplace distancing |

● Travel restrictions: current evidence from modelling studies on COVID-19 suggests that travel restrictions leading to reduced transmissibility can be highly effective in containing the spread ● School closure: is less effective than workplace distancing or quarantine of exposed individuals, a combined strategy which implements all three measures together was found to be most effective in reducing the spread. ● Airport screening is shown to be not as effective either ● workplace distancing was more effective in reducing the spread of COVID-19 than school closure |

| Patino-Lugo, D. F., et al. (2020). | To describe which non-pharmaceutical interventions used different countries and a when they use them. It also explores how Non-pharmaceutical interventions impact the number of cases, the mortality and the capacity of health systems | ● Argentina ● Australia ● Brazil ● Canada ● Chile ● China ● Colombia ● Cuba ● Germany ● Iran ● Italy ● Japan ● Mexico ● Norway ● Russia ● South Korea ● Spain ● United Kingdom and the USA |

● General population | ● Home-based setting ● Community environments ● Travels ● Workplace |

● Combination of measures ● Public transportation suspension ● Isolation ● Quarantine ● Social distancing measures ● Working areas measurements ● Restriction of travels between cities ● Restriction of domestic flights ● Closing day-cares and schools ● Quarantine of travellers from affected areas ● Border closure ● Airport case detection procedures |

● The effectiveness of isolated non-pharmaceutical interventions may be limited, but combined interventions have shown to be effective in reducing the transmissibility of the disease, the collapse of health care services and mortality. When the number of new cases has been controlled, it is necessary to maintain social distancing measures, self-isolation and contact tracing for several months.43 ● Other effects: economic impact and social impact |

| Poletti, B., et al. | To review the most recent experimental evidence about telepsychotherapy, focusing on its effectiveness, possible determinants of efficacy and therapists/patients’ attitudes, to rapidly inform psychotherapists | n.s. | ● Patients with common mental-health disorders | ● Telemedicine | ● Restrictions of health services ● Lockdown in general |

● Telepsychotherapy is a trustworthy alternative to be adopted, which can be used efficaciously to treat common mental-health disorders such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic distress. As well as in the traditional setting, a higher number of sessions and the proper management of patients' expectations seem to be asso- ciated with better outcomes.11 |

| Ren, X., et al. (2020) | to understand the impact of COVID-19 on mental health well-being | ● China | ● general population ● Health care workers |

● Home-based setting ● Community environments ● workplace |

• Social distance | • Social distance: people were prone to experience loneliness, anxiety and depression caused by social isolation and fear of being infected. People were worried also, about their love ones ● Other effects: economic impact and social impact |

| Sanchez, O. R., et al. (2020) | To analyse the existing scientific literature on strategies and recommendations to respond to violence against women (VAW) during the implementation of social distancing measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic | ● UK ● Italy ● China ● Switzerland ● USA ● Brazil ● Spain ● Germany ● Kenya ● Canada ● Australia ● India ● Netherlands ● South Africa ● Egypt |

● Women victims of violence | ● Home-based setting ● Community environments |

● Quarantine ● Lockdown ● Social distances |

● Quarantine: may increase the power and control abusers hold over victims and exacerbate violence in relationships. ● Lockdown and social distance: evidence showed that some factors increasing women’s vulnerabilities to violence were exacerbated during the social distancing and lockdown period |

| Shah, K., et al. (2020) | To assess global statistics and characteristics of household secondary attack rate (SAR) of COVID-19 | ● India ● China ● USA ● Taiwan ●Republic of Korea ● UK ● South Korea |

● General population ● Vulnerable populations ● Confirmed cases ● Contact with household, family and health care |

● Home-based setting ● Community environments ● Workplace |

● Quarantine ● Isolation |

● Quarantine and isolation: are most effective strategies for prevention of the secondary transmission of the disease. This study retrieved greater vulnerability of elder pepole and of spouse for secondary transmission than other household members |

| Stanworth, S. J., et al. (2020) | To provide a synthesis of the evolving published literature on COVID-19 and to provide expert opinion relevant to transfusion practice in times of potential or real shortage, addressing the entire transfusion chain from donor to patient | Multiple locations not specified | ● Patients with blood for transfusion needs ● Donors ● Healthcare workers |

● Home-based setting ● Inpatient level |

● Lockdown in general | ● A reduction in donor numbers has largely been matched by reductions in demand for transfusion. Contingency planning encompasses prioritisation strategies for patients of predicted shortage. |

| Tebeje, T. H., et al. (2020). | To examine how e-health applications are used to support person-centered health care at the time of COVID-19 | ● USA ● China ● Switzerland |

● General population ● Confirmed cases ● Contacts ● Health care workers |

● Telemedicine | ● Restrictions of health services ● Lockdown in general |

● Most of the studies used e-health technologies to facilitate clinical decision support and team care. Patient's engagement and access to health care from their homes were enhanced using telehealth and mobile health13 |

| Tinto, B., et al. (2020) | To review the information available in the literature on the epidemiological and clinical features of COVID-19 pandemic in West Africa | ● West Africa | ● General population | ● Home-based setting ● Community environments ● Workplace ● Travels |

● Travel restrictions ● Quarantine and self-containment of contacts of cases ● Introduction of a curfew in certain countries (Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Mali, Senegal, Niger and Guinea) ● Closure of markets and places of worship |

● Quarantine and self-containment of contacts of cases: the average size of households in certain West Africa countries is very high, this makes it difficult to comply distancing measures. ● Closure of markets and places of worship: the population struggles to comply with certain measures such as the closing of shops and the travel limitations. Difficulties to comply with self-containment and distancing measures could be a factor favouring the spread of the virus in these countries. ● Other effects: economic impact, as the majority of people work in the informal sector as trading and businesses, transport and restoration and these jobs are not subject to social protection |

| Tran, B. X., et al. (2020). | To explore the current research foci and their country variations regarding levels of income and COVID-19 transmission features | 115 countries | ● General population ● Healthcare workers |

● Home-based setting ● Community environments ● Workplace |

● Quarantine ● isolation ● Social distancing ● Community containment |

● Quarantine, isolation, social distancing and community containment: in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) implemented as soon as the outbreak occurred have demonstrated their effectiveness, for optimal public health as well as economic outcomes. ● Quarantine: stigma can arise when people are released from quarantine, even though they have been confirmed to be negative and are no longer risk. ● Other effects: economic impact |

| Usher, K., et al. (2020). | To examine, synthesize, and critically appraise the available evidence on the relationship between pandemic-related behaviours and psychological outcomes | ● Hong Kong ● Britain ● Portugal ● Finland ● Korea ● China ● Saudi Arabia ● Netherlands |

● General population of 18 years of age and above ● University students |

● Home-based setting ● Community environments ● Workplace |

● Social distancing ● Restricting religious activities ● Postponing or avoiding domestic or international travel ● Isolation ● Quarantine ● Restrictions of transports |

● Quarantine, isolation and social distancing: rapid implementation of these public health strategies is the most effective, and indeed necessary, for containing viruses in pandemics, they also have many potentially negative sequelae and lead to a higher level of distress, fear and anxiety, and drive an increase in levels of panic and uncertainty. These measures are implemented very quickly without very much time for preparation. The rapidity of the change can (in itself) cause community alarm and anxiety. ● Other effects: economic impact as lack of supplies, job losses and other financial concerns |

| Viner, R. M., et al. (2020) | To identify what is known about the effectiveness of school closures and other school social distancing practices during coronavirus outbreaks | ● Taiwan ● Singapore ● Beijing ● China ● Hong Kong ● UK |

● General population: children and adults | ● School | ● School closure | ● School closure: data from the SARS outbreak suggest that school closures did not contribute to the control of the epidemic. Modelling studies of SARS produced conflicting results, modelling studies of COVID-19 predict that school closures alone would prevent only 2–4% of deaths, much less than other social distancing interventions. Adverse effects of school closure include: transmission from children to vulnerable grandparents, harms to child welfare particularly among the most vulnerable pupils, and nutritional problems especially to children for whom free school meals are an important source of nutrition, psychological harms. ● Other effects: economic harm: on working parents, health-care workers, and other key workers being forced from work to childcare, social impact and loss of education |

| Webster, R. K., et al. (2020) | To identify factors associated with adherence to quarantine during infectious disease outbreaks | ● Australia ● Sierra Leone ● Canada ● Senegal ● Liberia ● Taiwan ● Germany |

● School principals and staff ● Parents ● Students ● Households ● Contacts ● Residents ● Health care workers |

● Home-based setting ● Community environments ● Workplace ● School |

● Quarantine | ● People vary in their adherence to quarantine during infectious disease outbreaks. [...] The main factors which influenced or were associated with adherence decisions were the knowledge people had about the disease and quarantine procedure, social norms, perceived benefits of quarantine and perceived risk of the disease51 ● Other effects: economic impact as the need to work and fear of loss of income linked to quarantine |

| Yamamoto, V., et al. (2020) | To provide a comprehensive review of SARS-CoV-2 and to focus on nutritional support, psychological and rehabilitation of the pandemic and its management | Multiple locations | ● General population ● People with Alzheimer’s Disease or dementia ● Health-care workers |

● Home-based setting ● Community environments ● Workplace |

● Quarantine ● Social isolation |

● Quarantine: evidence suggests a link between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and/or depression and quarantine. There is a positive correlation between length of quarantine and symptoms of PTSD. The psychological symptoms were higher among health-care workers relative to others ● Social isolation: working from home, physical distancing, job loss and critical illness from the virus could induce long-term psychological effects in many individuals. Social isolation has been linked to a heightened risk of suicide attempts and suicide and several studies address the connection between job loss and a heightened risk of depression, anxiety and increased substance abuse. Social isolation has also been linked to domestic abuse and violence-related behaviours in the home ● Other effects: economic and social impact |

| Zupo, R., et al. (2020) | To analyze the preliminary effects of the quarantine lifestyle from the standpoint of dietary habits | ● Poland ● India ● Italy ● Spain ● China ● Chile ● Colombia ● Brazil |

● General population | ● Home-based setting | ● Lockdown ● Quarantine |

● Lockdown and quarantine: these results identified: i) a rise in consuption of carbohydrates; ii) more numerous snacks; iii) an high intake of fruits, vegetables and protein and iv) a decreased alcohol intake and fresh fish/seafood consumption. Data were scant on the consumption of junk foods. |

Characteristics of included articles

The majority of systematic reviews included focused on the impact of lockdown measures, with only nine articles focussing mostly on the impact of the pandemic.

Concerning the type of lockdown restrictions, the majority of the systematic reviews was focused on isolation, quarantine and social isolation, with many articles discussing multiple restrictive measures.

As regards other lockdown measures, four articles described the impact of school closures,41–43,50 seven systematic reviews explored the impact of travel restrictions,23,32,41–43, 47,49 two examined the impact of workplace distancing,42,43 and one explored the impact of restrictions of funeral practices.24

With regard to the impact on health services, two systematic reviews1,4 explored the rescheduling of non-urgent outpatient visits, non-urgent surgery interventions, the putting on hold of ‘non-essential’ activities and the limitations in accessing hospitals. The indirect effect of restrictions of health services, and lockdown more generally, is represented by telemedicine, which is described by the 10 systematic reviews.1,3,5–11,13

The health impact of lockdown measures can be direct or indirect (Table 2). The direct health impact that has been covered in the greatest number of included articles relates to mental health,16–19,21,22,24–26,28–34,36–38,40,44,45,48,49,52 followed by systematic reviews on healthcare delivery,1–13 and those on infection control.23,27,35,36,41–43,46,48,50,51 The predominant areas of indirect health impacts covered by the included studies relate to the economic9,21,23,27,28,31,33,43,44, 47–52 and social impacts.9,23,31,43,44,50,52 Only 3 articles mentioned the negative impact on education.17,33,50

Table 2.

Health impact areas of the studies included

| Number of systematic reviews a | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Direct health impact area | ||

| °Lifestyle and dietary habits | 2 | (Bentlage et al., 2020; Zupo et al., 2020) |

| °Violence and abuse | 4 | (Abdo et al., 2020; Fouche et al., 2020; Sanchez et al., 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2020) |

| °Substance abuse | 4 | (Abdo et al., 2020; Banerjee et al., 2020; Fouche et al., 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2020) |

| °Well-being and quality of life | 5 | (Banerjee et al., 2020; Barello et al., 2020; Brooks et al., 2020; Melo-Oliveira et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2020) |

| °Older people | 5 | (Banerjee et al., 2020; Bentlage et al., 2020; Lithander et al., 2020; Noone et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020) |

| °Children and child development and desire for parenthood | 6 | (Araujo et al., 2020; Bentlage et al., 2020; Fouche et al., 2020; Loades et al., 2020; Melo-Oliveira et al., 2020; Park et al., 2020; Viner et al., 2020) |

| °Infection control | 12 | (Burns et al., 2020; Chandana Kumari et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Lithander et al., 2020; Nussbaumer-Streit et al., 2020; Park et al., 2020; Patino-Lugo et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020; Tran et al., 2020; Viner et al., 2020; Webster et al., 2020) |

| °Health care delivery | 13 | (Andrenelli et al., 2020; Ceravolo et al., 2020; Chaudhry et al., 2020; Ferreira et al.,2020; Gao et al., 2020; Grimes et al., 2020; Haider et al., 2020; Lenferink et al., 2020; Leochico et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2020; Poletti et al.,2020; Stanworth et al., 2020; Tebeje & Klein, 2020) |

| °Mental health | 25 | (Abdo et al., 2020; Araujo et al., 2020; Banerjee et al., 2020; Barello et al., 2020; Brooks et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2020; Burrell & Selman, 2020; Cabarkapa et al., 2020; Carmassi et al., 2020; Fouche et al., 2020; Henssler et al., 2020; Hossain et al., 2020; Imran et al., 2020; Lahiri et al., 2020; Lasheras et al., 2020; Leaune et al., 2020; Lithander et al., 2020; Loades et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020; Noone et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2020; Sanchez et al., 2020; Tran et al., 2020; Usher et al., 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2020) |

| Indirect health impact area | ||

| °Education | 3 | (Araujo et al., 2020; Lasheras et al., 2020; Viner et al., 2020) |

| °Inadequate supplies | 3 | (Brooks et al., 2020; Fouche et al., 2020; Usher et al., 2020) |

| °Social impact | 7 | (Burns et al., 2020; Imran et al., 2020; Leochico et al., 2020; Patino-Lugo et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2020; Viner et al., 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2020) |

| °Economic impact | 15 | (Brooks et al., 2020; Burns et al., 2020; Chandana Kumari et al., 2020; Fouche et al., 2020; Imran et al., 2020; Lasheras et al., 2020; Leochico et al., 2020; Patino-Lugo et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2020; Tinto et al., 2020; Tran et al., 2020; Usher et al., 2020; Viner et al., 2020; Webster et al., 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2020) |

aThe same articles can be included in more than one area of impact

Direct health impact

Mental health

Overall, almost half of the studies explore the impact of lockdown measures on mental health.16–19,21,22,24–26,28–34,36–38,40,44,45,48,49,52 While the rapid implementation of quarantine, isolation and social distancing measures seems to be the most effective strategy to contain the spread of the virus, these measures, when implemented at short notice, can produce alarm and anxiety.49

The studies reported a high burden of mental health problems among several groups of the population who experienced quarantine or isolation: patients, the general population and health workers. Prevalent mental health issues include anxiety,17,18,21,29–31,33,37,44,49,52 depression,17,18,29,30,37,44,52 post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), stress,17,19,21,22,25,26,29–31,37,49,52 and stigmatization. In particular among children, older people and health workers the evidence suggests a link between PTSD and quarantine or isolation.21,25,30,31,37,52 Stigma is linked both to quarantine and isolation30 and particularly experienced by health workers21 and children31,48; the two groups experienced stigma due to quarantine even if they had been confirmed to be negative.31,48

Health care delivery

The pandemic and the subsequent lockdown measures had a negative impact on health care delivery, resulting in limitations to available health care services. These restrictions included: the postponement of non-urgent outpatient visits and of non-urgent surgical interventions, the reduction of non-essential services, and restrictions in accessing hospitals for both patients and their caregivers.1

The included studies find that restrictions of health care services posed enormous challenges to patients and health care providers, and telemedicine has been proposed by several authors as a potential solution to overcoming the barrier in accessing health care services, especially for outpatient care.3,5–11,13

Tele-psychotherapy8,11 has been evaluated in treating common mental-health disorders such as anxiety, depression and PTSD. The use of telemedicine has also been investigated in orthopaedic care.3,7 The resulting reduction in inpatient and outpatient orthopaedic care and the increase in remote orthopaedic care was associated with high patient satisfaction related to convenience and reduced waiting and travelling times. Evidence suggests that telemedicine in orthopaedic care can be safe and cost-effective, with high patient and clinician satisfaction.7

The restrictions of rehabilitation services due to lockdown measures increased, especially among older people, the risk of frailty, sarcopenia, dementia, cognitive decline and depression, in particular among those quarantined at home or with restricted mobility.1 Yet, a systematic review on tele-rehabilitation identified 53 challenges in the literature (e.g.: on sustainability and privacy) that could affect the development of tele-rehabilitation.9

Finally, a systematic review on the delivery of urogynaecology care using telemedicine6 identified the clinical situations that would allow virtual settings and those that should be managed with an in-person visit despite the risks of COVID-19 transmission.

Infection control

The effect of lockdown measures on infection control was investigated in 12 systematic reviews.23,27,35,36,41–43,46,48,50,51 According to Chandana et al.,27 quarantine is one ‘of the most misunderstood and feared methods of controlling COVID-19, because it may affect both infected and non-infected individuals with psychological, economical and emotional complications such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, insomnia, mood swings’. They continue that the lockdown of a city ‘was proved to be effective when a study reported 72% drop in the number of infected people’.27 A systematic review conducted in China35 emphasises that the lockdown of a city reduced the reproduction number (R0) from 3.77 to a controlled reproduction number (Rc) of 1.88 after lockdown. Other public health measures implemented, apart from citywide lockdowns and, encompassing contact tracing, intensification of screening, quarantine and mask utilisation, may also be contributing to containing the spread of the virus.35 In fact, some systematic reviews suggest that combinations of different control measures are the most effective way to reduce transmission of the disease, prevent the collapse of health care services and reduce mortality.41,43

Concerning travel restrictions, a systematic review on COVID-19, SARS and MERS suggested that travel restrictions leading to reduced transmissibility can be highly effective in containing the spread.42 In line with these results are those retrieved by the Cochrane Systematic Reviews developed by Burns et al.,23 which found that travel-related control measures during the COVID-19 pandemic may have a positive impact on infectious disease outcomes. In particular, travel restrictions may limit the spread of disease across national borders, while entry and exit symptom screening measures on their own are not likely to be effective. The evidence is scant on the effectiveness of travel-related quarantine23 and there is very low-certainty evidence on the effect of quarantine of travellers from a country with a declared outbreak on reducing incidence and death.41

Finally, systematic reviews on the impact of school closures found that they do not seem to be effective42 and do not contribute to the control of the epidemic.50

Children, child development and desire for parenthood

Six systematic reviews on children and their development17,20,28,37,42,50 have been included in our study. The focus on the limited effect of school closures on pandemic control,42,50 as discussed above, and on adverse effects of school closures on issues including: increased risk of transmission from children to grandparents, harms to child welfare particularly among the most vulnerable pupils, nutritional issues and the loss of teaching/learning and socialization processes. Importantly, children miss out on public policies taking place in schools, such as balanced and free food programs, guidance about personal hygiene, physical activity and citizenship initiatives.50

Social isolation in children may increase the risk for cardiovascular disease, reduce physical activity and have negative effects on mental health,20,50 such as an increased likelihood of high rates of depression and anxiety during and after enforced isolation.37

Quarantine in children is linked to anxiety, stress and depression and can become a risk factor for child growth and development.17

Isolation and quarantine together are related to an increased risk of requiring mental health services and to higher levels of post-traumatic stress.37

A systematic review found that during quarantine, despite a reduction in the quality of life, there was an increased desire for parenthood, although it is unknown if these changes are associated with an increase in terms of birth rates.39

Older people

Despite quarantine and isolation being the most effective strategies for prevention of the secondary transmission of disease, the evidence suggests a greater vulnerability of older people for secondary transmission than other household members.46 Other negative consequences were also experienced, particularly if quarantine and isolation were in place for an extended period, and the loneliness caused by social isolation has been associated with impaired cognitive function in older adults.36

Lockdown in older people with a subsequent reduction in social participation and physical activity during home confinement was identified as a serious concern, as they are typically more inactive and more disposed to chronic disease.18,20 Finally, a systematic review on older people in nursing homes emphasized that older people suffer from social distancing due to isolation and confinement. The evidence on this however was limited because only few studies with a small sample size and using unreliable methods were included in this systematic review.40

Well-being and quality of life

Only five systematic reviews were retrieved on well-being and quality of life (QOL).18,19,21,39,44 Importantly, four systematic reviews explored the impact of lockdown measures on health workers in terms of well-being and QOL.18,19, 21,44 According to the evidence summarised in these studies, healthcare professionals who had been quarantined had more severe symptoms of post-traumatic stress than the general population, felt stigmatised, presented more avoidance behaviours, reported huger lost income and were more affected at the psychological level.21

Quarantine in the general population was linked to a reduction of the mean wellbeing scores,39 work-related stress, burnout,19 frustration, fears of infection, boredom, inadequate supplies and inadequate information.21

Finally, lockdown and social distancing were linked in the general population to a negative psychosocial impact, an increased prevalence of depression, anxiety, sleep, alcohol use disorders and the fear of being infected. People were also worried about their loved ones.18,19,44

Substance abuse

The four systematic reviews16,18,28,52 focussed on the correlation of infection control measures and substance abuse found that lockdown was associated with increased alcohol use disorders in the general population,18 and social isolation and quarantine were identified as potential contributors to the aggravation of substance abuse.16,52

Violence and abuse

A link between lockdown and domestic violence and abuse was identified in four systematic reviews,16,28,45,52 with three of them16,28,52 also exploring substance abuse (see previous section).

Social isolation was linked to domestic abuse and violence-related behaviour in the home.52 A systematic review identified that some factors increasing women’s vulnerabilities to violence were exacerbated during the social distancing and lockdown period.45 Even quarantine can increase the power and control abusers hold over victims and trigger violence.16,45 To overcome this issue with regard to children, South Africa’s strict lockdown offered protective pathways, including a policy to protect children at risk of abuse.28

Lifestyle and dietary habits

Among the 51 systematic reviews included in our study, only two20,53 focussed on lifestyle and dietary habits. Lockdown and quarantine were found to be associated with an increase of carbohydrate consumption, as well as more frequent consumption of snacks, although together with a high consumption of fruits and vegetables, and protein sources.20,53

Social isolation was found to cause a decrease in physical activity and, for children, a decrease in the time devoted to sports, and an increase in time sleeping and spent in front of screens, potentially increasing overweight and obesity among children.20,53

Indirect health impact

The areas of indirect health impact9,17,21,23,27,28,31,33,43,44,47–52 identified in the included studies concern the economic and social impact, the impact on education and the lack of supplies and food (Table 2).

Overall, the non-pharmaceutical interventions implemented to contain the virus, such as quarantine, isolation, social distancing and community containment, were noted to have important economic21,27,28,31,43,48,49,51,52 and social consequences.27,31,43,44,52 In particular, quarantine was associated with the necessity to work, the fear of loss of income, the lost income itself and a reduction in overall productivity resulting in a decline of economic growth.21,27 Moreover, some systematic reviews21,28,31,49 identified other fundamental issues, such as the lack or insecurity of supplies and food, and inadequate information, particularly linked to quarantine.

School closures were associated with a loss in teaching/learning and education, as well as with wider social impact and economic harm on working parents, health workers and other key workers being forced from work to care for children at home.17,50 Moreover, a systematic review33 on the prevalence of anxiety in medical students during the pandemic identified concerns on economic impact, academic delay, curricular factors and impact on their daily life.

Travel-related control measures related to quarantine had far-reaching economic, social, legal, ethical and political implications.23

Some populations, such as in west Africa,47 had difficulties complying with certain measures, such as travel limitations and the closure of markets and places of worship, as the majority of people work in the informal sector, including trading, other businesses, transport and restoration and these jobs are not subject to social protection.

Discussion

This systematic review set out to systematically review the evidence published in systematic reviews on the health impact of staying at home, social distancing and lockdown measures. A number of important findings emerged.

The first relates to the areas that have been studies so far. We intentionally kept a broad focus on all policy areas that are associated with the social determinants of health. Surprisingly, almost half of the studies (25 of 51) explore the impact of lockdown measures on mental health, with the common finding that these measures put a strain on the mental health of patients, the health workers and the general population. The second most commonly studied area, explored in 14 of the 51 included studies, was concerned with health care delivery. Many of these 14 systematic reviews explore the issue of telemedicine, with only indirect references to the Coronavirus pandemic. The impact of lockdown measures on containing the spread of the virus was explored in 12 studies, with the overall finding that these measures are successful and most promising when used in combination. In general, lockdown measures are enacted to contain the virus, but often discontinued for economic or political rather than purely epidemiological reasons. Other areas of the health impact of lockdown measures have received far less attention so far and warrant further research.

A second key finding of our study highlights that the complex and multifactorial nature of the health impact of lockdown measures, which can be both direct and indirect. While the closure of schools, for example, will have a direct impact on the education, mental and physical health of children, an indirect impact is that parents will have to stay at home to look after young children, preventing them from going to work. While our primary interest was on the impact of lockdown measures, it was sometimes difficult to ascertain whether the impact was due to these measures or the pandemic itself. We found that many studies were struggling with the same challenge. Causal pathways are often blurred, as mental health, for example, can be affected by both, policy measures and the pandemic itself. Policy measures aimed at containing the spread of the virus will have to mindful of direct and indirect impacts and intended and unintended consequences.

A third key finding relates to the strength of evidence gathered by October 2020. Unsurprisingly, the evidence on the topic was still mainly focused on the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic that occurred in spring 2020 and a renewed search of the literature is needed to capture more up-to-date evidence. We also identified methodological and terminological challenges. With regard to the methods used, some narrative reviews are defined by the authors as systematic reviews and vice versa. Furthermore, in many systematic reviews, conclusions are drawn based on a very limited number of papers with often low quality. In addition, in some systematic reviews, the impact of lockdown measures is mainly described in the introduction and the conclusions, rather than in the results section. There is also a need for more terminological clarity. Some authors misuse the terms ‘isolation’ and ‘quarantine’ and confuse ‘social isolation’ with ‘isolation’.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements and Funding

This work was funded by the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies in support of a request by the Austrian Ministry of Social Affairs, Health, Care and Comsumer Protection. The funder had no involvement in the conduct of the research. The authors would like to express their gratitude to Anja Laschkolnig (Austrian National Public Health Institute) for her input into the search strategy.

Valentina Chiesa, MD, Local Helath Unit of Reggio Emilia

Gabriele Antony, Health Expert, Austrian National Public Health Institute

Matthias Wismar, Programme Manager, Health Systems and Policies Place

Bernd Rechel, Researcher at European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies

Contributor Information

Valentina Chiesa, Local Health Unit of Reggio Emilia, Via Giovanni Amendola, 2, 42122, Reggio Emilia, Italy; London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine London, WC1H 9SH, 15-17 Tavistock Place, United Kingdom.

Gabriele Antony, Austrian National Public Health Institute (Gesundheit Österreich GmbH, GÖG).

Matthias Wismar, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Place Victor Horta 40/10, 1060 Brussels, Belgium.

Bernd Rechel, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, WC1H 9SH, 15-17 Tavistock Place, United Kingdom.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

Not required.

All data are incorporated into the article and its online supplementary material.

References

- 1. Andrenelli E, Negrini F, de Sire A et al. Systematic rapid living review on rehabilitation needs due to COVID-19: update to May 31st, 2020. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020;56(4):508–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ceravolo MG, de Sire A, Andrenelli E et al. Systematic rapid "living" review on rehabilitation needs due to COVID-19: update to march 31st, 2020. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020;56(3):347–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chaudhry H, Nadeem S, Mundi R. How satisfied are patients and surgeons with telemedicine in orthopaedic care during the COVID-19 pandemic? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2020;28:47–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferreira CHJ, Driusso P, Haddad JM et al. A guide to physiotherapy in urogynecology for patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Urogynecol J 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gao YL, Liu R, Zhou Q et al. Application of telemedicine during the coronavirus disease epidemics: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann Translat Med 2020;8(10):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grimes CL, Balk EM, Crisp CC et al. A guide for Urogynecologic patient care utilizing telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: review of existing evidence. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2020;75(8):469–70. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haider Z, Aweid B, Subramanian P et al. Telemedicine in orthopaedics and its potential applications during COVID-19 and beyond: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2020;1357633X20938241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lenferink LIM, Meyerbroker K, Boelen PA. PTSD treatment in times of COVID-19: a systematic review of the effects of online EMDR. Psychiatry Res 2020;293: (no pagination). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leochico CFD, Espiritu AI, Ignacio SD et al. Challenges to the emergence of telerehabilitation in a developing country: a systematic review. Front Neurol 2020;11:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murphy EP, Fenelon C, Murphy RP et al. Are virtual fracture clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic a potential alternative for delivering fracture care? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2020;26: 2610–2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poletti B, Tagini S, Brugnera A et al. Telepsychotherapy: a leaflet for psychotherapists in the age of COVID-19. A review of the evidence. Couns Psychol Q 16. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stanworth SJ, New HV, Apelseth TO et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on supply and use of blood for transfusion. Lancet Haematol 2020;7(10):e756–e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tebeje TH, Klein J. Applications of e-health to support person-centered health care at the time of COVID-19 pandemic. Telemedicine J Health 2020;31:150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Green L, Morgan L, Azam S et al. A Health Impact Assessment of the ‘Staying at Home and Social Distancing Policy’ in Wales in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Main Report. Cardiff: Public Health Wales NHS Trust, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, Moher D, Liberati A et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abdo C, Miranda EP, Santos CS et al. Domestic violence and substance abuse during COVID19: a systematic review. Indian J Psychiatry 2020;62(9 Supplement 3):S337–S42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Araujo LAD, Veloso CF, Souza MDC et al. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child growth and development: a systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]