Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic is an unprecedented public health crisis, but its effect on suicide deaths is little understood.

Methods

We analyzed data from monthly suicide statistics between January 2017 and October 2020 and from online surveys on mental health filled out by the general population in Japan.

Results

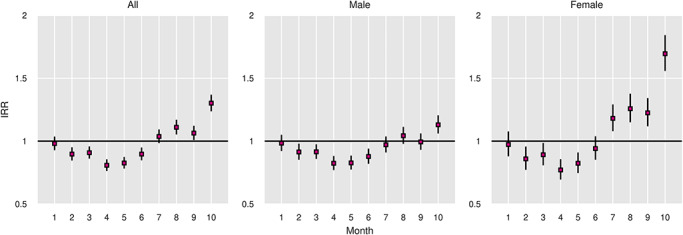

Compared to the 2017–19 period, the number of suicide deaths during the initial phase of the pandemic was lower than average but exceeded the past trend from July 2020. Female suicides, whose numbers increased by approximately 70% in October 2020 (incidence rate ratio: 1.695, 95% confidence interval: 1.558–1.843), were the main source of this increase. The largest increase was found among young women (less than 40 years of age). Our survey data indicated that the status of young women’s mental health has been deteriorating in recent months and that young female workers were more likely to have experienced a job or income loss than any other group, suggesting adverse economic conditions surrounding them.

Conclusions

Continuous monitoring of mental health, particularly that of the most vulnerable populations identified in this study, and appropriate suicide prevention efforts are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: mental health, morbidity and mortality, socioeconomics factors

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic is an unprecedented public health crisis that has both physical and mental health consequences. Emerging evidence suggests that this pandemic severely affects the mental health of the general population.1,2 These findings correspond with concerns that deteriorating mental health, in combination with higher unemployment rates during the pandemic, have the potential to increase the incidence of suicide worldwide3,4 as both conditions are risk factors for suicide.5–7

Despite this risk, to the best of our knowledge, there is still limited evidence on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of suicide at the national level by major demographic groups. The findings of a few existing studies suggest that the number of suicide deaths during the pandemic may initially decline8 or remain largely unchanged,9 then be followed by an increase,10 but none of these studies investigated the psychological and economic conditions of groups that have experienced changes in the number of suicide deaths. To address this gap, we examined the suicide deaths and mental health status of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan using our own monthly survey data, allowing us to closely monitor the status of the general population since the onset of the pandemic.

Japan had its first encounter with COVID-19 earlier than most of the rest of the world. The first case was reported on 16 January 2020, followed by outbreaks on a cruise ship at Yokohama Port in February 2020. The first wave of COVID-19 cases was observed in April 2020, and a second, larger wave of cases started in July 2020. As of 31 October 2020, the total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases was 91 329, and the number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 was 1754, or 13.95 deaths per 1 million people.11 The number of new COVID-19 cases in Japan is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

The Japanese government has imposed several measures to stem the tide of the pandemic. School closures started in early March, and the government declared a state of emergency in major metropolitan areas on 7 April 2020, which was extended to the rest of the country on April 16. Without introducing lockdown measures or strict domestic movement restrictions during the state of emergency, authorities requested non-essential businesses to close or opt to work remotely and requested stores and restaurants to operate for reduced hours. The state of emergency was lifted on 25 May 2020.

To examine the effect of these events, we examined the monthly trajectories of suicide deaths by sex, age group and occupation as well as the mental health conditions of these groups during this pandemic.

Methods

Data on suicide

We analyzed the publicly available monthly suicide statistics for January 2017–October 2020 (as of 30 November 2020) tabulated by the National Police Agency (NPA) and published by the NPA and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.12,13 The NPA suicide statistics are based on police investigations of suicide cases. There are two types of NPA data: those tabulated based on the date that the deceased was found and those tabulated by the date of death. We used the former, as these are the most frequently updated data.

Model

We examined the total number of deaths by suicide and the number of suicides by sex, age group (<40 years, 40–59 years and ≥ 60 years) and major occupations. We estimated the following Poisson regression model:  where the dependent variable is the number of suicides in month m in year y for group g, and

where the dependent variable is the number of suicides in month m in year y for group g, and  The

The  is an indicator variable for each month in 2020 (until October), where

is an indicator variable for each month in 2020 (until October), where  , and its associated coefficient,

, and its associated coefficient,  , captures the difference in the number of suicides in month k relative to the baseline period, which is the corresponding month in the last 3 years. The month fixed effects (i.e. 12 indicator variables for each month),

, captures the difference in the number of suicides in month k relative to the baseline period, which is the corresponding month in the last 3 years. The month fixed effects (i.e. 12 indicator variables for each month),  , were included to capture the baseline monthly fluctuations in suicide deaths. To facilitate the interpretation of the Poisson regression results, we converted the coefficients to incidence rate ratios (IRRs). This part of the analysis used publicly available data; thus, no ethics approval was necessary.

, were included to capture the baseline monthly fluctuations in suicide deaths. To facilitate the interpretation of the Poisson regression results, we converted the coefficients to incidence rate ratios (IRRs). This part of the analysis used publicly available data; thus, no ethics approval was necessary.

Data on mental health and changes in economic status

In addition, we assessed the general Japanese population’s mental health status by using data from a series of monthly online surveys that we have been conducting since April 2020. We selected the respondents from a commercial online panel so that they were representative of the Japanese population in terms of sex, age group and area of residence. Each monthly survey contained 1000 respondents. A more detailed description of the survey is provided in the Supplementary data. For the purposes of this study, we used surveys taken between April and October 2020 (N = 7000).

To measure mental health, we analyzed the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire nine-item scale14 and the seven-item General Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7),15 respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha values for each of the scales were 0.90 and 0.92, respectively. We also examined the respondents’ self-reported change in employment to understand whether they had experienced major job-related changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. We asked about changes in employment status only since June and used the data between June and October 2020 to analyze the job-related changes of the respondents (N = 5000). We calculated the presence of depressive (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) and anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 ≥ 10) as well as the percentages of those who had lost their jobs, taken leave or been temporarily laid off from work or experienced significant reduction in working hours in the last 3 months, and stratified them by sex and age group.

The survey was approved by the Ethics Review Committee on Human Research of Waseda University (approval #: 2020-050) and Osaka School of International Public Policy, Osaka University.

Results

During our study period, the number of suicides recorded in the NPA data was 81 431 of which 55 963 cases were for males and 25 468 suicide cases were for females. The average number of suicides per month was 1732.57 (SD = 158.98), and the maximum number was 2158, which was recorded in October 2020.

The top panel of Fig. 1 shows the IRRs for the months in 2020 when we used the overall number of suicide deaths in Japan and suicide by sex as the outcomes. The estimation always includes indicator variables for each month, and thus, the baseline period is the mean of 2017–19 in the corresponding months. The number of suicide deaths in the two time periods is provided in Supplementary Fig. S2. The shaded area in the figure indicates the period of the state of emergency. Starting in February, when the country had a major encounter with the disease with the Diamond Princess case, Japan experienced a decrease in suicide deaths. However, the declining trend observed in the early phase reversed in July and the IRR increased to 1.302 in October (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.237–1.369). The source of the increased suicide cases was mainly female suicides; the IRR for female suicides was 1.181 (95% CI: 1.079–1.292) in July, and it continued to rise until October (IRR: 1.695, 95% CI: 1.558–1.843).

Fig. 1.

The IRRs for suicides in Japan in 2020 relative to 2017–19: total and by sex. Note: the vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

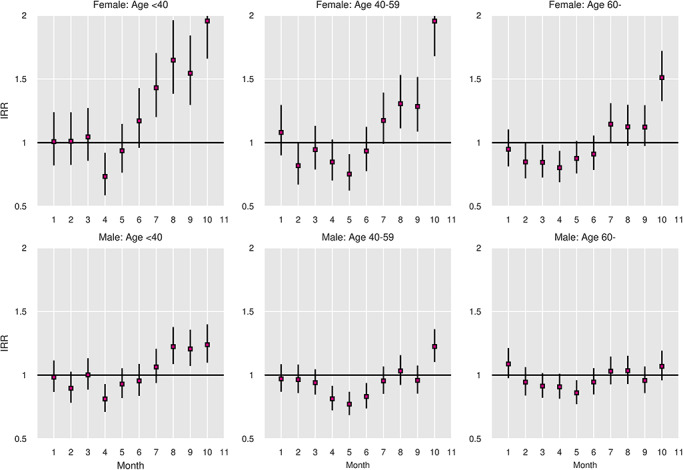

According to Fig. 2, which reports the IRRs by sex and age group, suicide deaths by all demographic groups exhibited the same trajectories, with an initial decline during the state of emergency followed by an increase starting in July. We observed the largest increase among young individuals (less than 40 years old) for both sexes. In particular, the incidence of suicide among young women was 1.648 and 1.956 (95% CI: 1.384–1.962 and 1.66–2.304) for August and October, respectively. However, in October, suicides by middle-aged women (age group: 40–59 years) also sharply increased (IRR: 1.955, 95% CI: 1.679–2.276).

Fig. 2.

The IRRs for suicides in Japan in 2020 relative to 2017–19: by sex and age group. Note: the vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

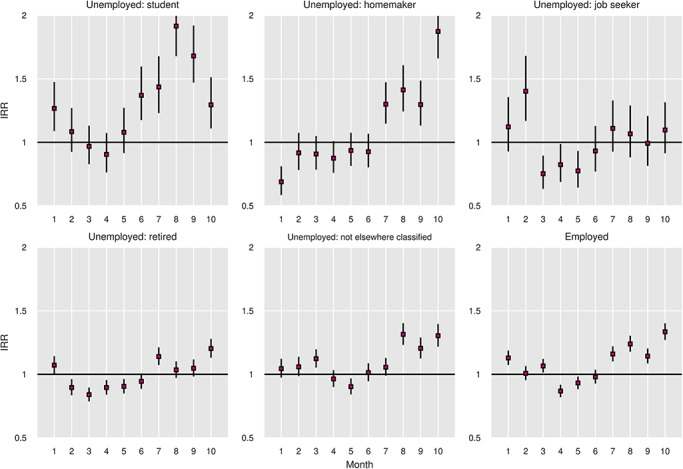

Figure 3 reports the IRRs for the months in 2020 by major occupation categories. The number of suicide deaths by occupation group is provided in Supplementary Fig. S3. It indicates that students and homemakers experienced the largest increase in suicides during the second phase of the pandemic. Student suicides started to increase in June with its IRR peaked in August (1.915, 95% CI: 1.678–2.186). The increase was observed not just among middle and high school students; the number of suicides by university students almost doubled in August and September 2020 (46 and 51 in 2020, respectively, the average in 2017–19 in each month: 24). The incidence of suicide among homemakers also increased starting in the summer months, with the IRR for homemaker suicides rising to 1.873 in October (95% CI: 1.661–2.113). Among the employed, the number of suicides started to rise in July and the IRR in October was 1.335 (95% CI: 1.271–1.402).

Fig. 3.

The IRRs for suicides in Japan in 2020 relative to 2017–19: by major occupation group. Note: the vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

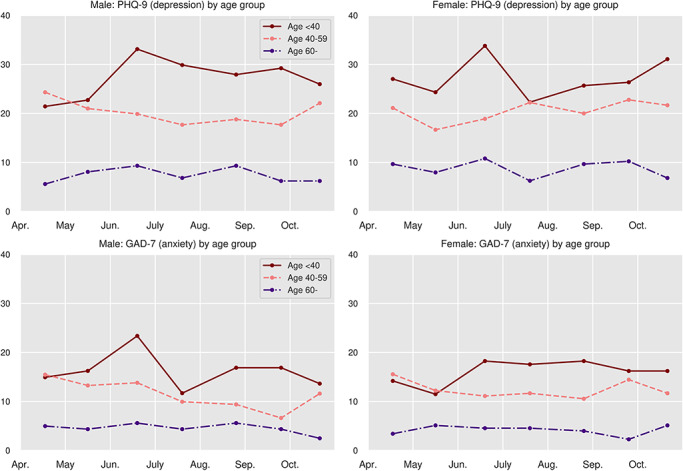

Figure 4 reports the percentages of those categorized as having depressive symptoms or anxiety disorders according to sex and age group. The top panel shows the prevalence of depression based on PHQ-9 score, and the bottom panel shows the percentages of those who were considered to have anxiety disorders based on their GAD-7 score. Overall, relatively young individuals (those less than 40 years old) were more likely to have depressive and anxiety symptoms than those in older age groups. The June data reported the worst status of mental health for these individuals, which was right after the state of emergency was lifted. Figure 4 also suggests that the prevalence of depressive symptoms among relatively young women has been increasing since July, with 31.08% of them (N = 148) being classified as depressed in October.

Fig. 4.

The prevalence of depressive/anxiety symptoms among the general population in Japan by sex/age group: April–October 2020.

Finally, when we analyzed our survey respondents in the labor force who reported to have lost their job, taken leave/been temporarily laid off from work or experienced a drastic decrease in working hours over the past 3 months, stratified by sex and age groups, we found that female respondents were more likely to experience changes in their employment status and working hours, with 21.37% of them reporting such changes compared to 16.25% of male workers. Among female workers, 25.24% of young individuals (less than 40 years old) reported drastic changes in employment and working conditions, whereas the corresponding number for young male workers was lower at 17.01%. The full data are reported in Supplementary Table S1.

Discussion

Main finding of this study

This study examined the monthly trajectories of suicide deaths in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that the number of suicide deaths was lower during the initial phase of the pandemic in 2020 than the average during the 2017–19 period. Starting in July 2020, however, the number exceeded the trend of the past 3 years. Across all age and occupation groups, the largest increase was found among relatively young women, those aged less than 40 years at the time of their death. The prevalence of suicide among students and homemakers during the second phase of the pandemic was also notably higher in 2020 than the monthly averages of 2017–19.

What is already known on this topic

The COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented public health crisis that entails both physical and mental health consequences. However, its effect on actual suicide deaths and the psychological and economic conditions of demographic groups that have experienced an increase in suicide deaths is not fully understood.

What this study adds

This study presented one of the first systematic evidence on the monthly trajectories of suicide deaths by sex, age group and occupation in one of the world’s most developed countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. It also highlighted the most vulnerable populations during this unprecedented public health crisis.

Potential factors behind the large increases in suicide cases by women and young individuals during the second phase of the pandemic include the economic consequences of the pandemic, school closures and media reporting of celebrity suicides. The economic damage of the current pandemic was particularly evident in industries that are served mainly by women, such as the service, retail and travel industries.16 The labor statistics for October 2020 indicate that the number of employed individuals in non-permanent positions, such as part-time or contract workers, decreased for 8 consecutive months from the onset of the pandemic. Between July and October 2020, the number of these precarious workers decreased by 4.59 million from the same months in the previous year of which 2.91 million were women.16 It should also be noted that the occupation categories reported in the NPA data are based on the occupation at the time of death, and some women might have been categorized as homemakers if they had lost their jobs prior to their death.

The results of our survey also revealed the unfavorable psychological and economic conditions of young women. We found that the status of mental health among young women (less than 40 years of age) was worse than that of women aged above 40 years, which may underlie their relatively high suicide rate in the second half of 2020. Relatively worse mental health conditions among young and economically vulnerable individuals were also reported in another study in which other attributes of the respondents were explicitly taken into account.17 In addition, we found that young female workers were more likely to have experienced a job or income loss in recent months than any other groups were, suggesting their adverse economic conditions.

The increase in student suicides might be associated with the school closure and unusual school calendar of 2020. Schools in Japan closed around 2 March after the former Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, abruptly announced a request for school closure on 27 February 2020, and they did not reopen until the state of emergency was lifted in late May. Thus, elementary to high school students had to stay at home for almost 3 months. Emerging evidence indicates the negative impact of school closure on students; a study conducted between June and July (after school reopening) found that 72% of surveyed students reported symptoms that indicated some form of stress reaction.18

Returning to school after a long break is known to be difficult for some students, even in normal years, and student suicides have previously peaked on the first day of school after the summer break, specifically on 1 September.19 Elementary to high schools in Japan resumed around late May and reopened in August after a short summer break in 2020, which may explain the observed increase in student suicides starting in June.

As for university students, most universities in Japan switched to online teaching when the new academic year started in April and largely remained online during the spring and fall semesters.20 It is possible that some university students were under distress because online and solitary learning without on-campus activities continued for a prolonged period; 29.41% of the students in our survey were classified as depressed, equivalent to the prevalence of depression symptoms among those who had lost their jobs (Supplementary Table S2).

Media reports on celebrity suicides might also explain some of the increases in suicide deaths observed in this study. Several well-known individuals died by suicide during the pandemic; two notable instances were the suicide death of a male actor, who died at the age of 30 years on 18 July 2020, and that of a 40-year-old actress on 27 September 2020. Both of them were at the peak of their careers and the media reports on their unexpected suicide deaths might have affected vulnerable individuals. The subsequent increase in actual suicides is known to be particularly large when celebrity suicides are widely discussed on social media or when they are regarded as a ‘surprise’,21,22 both of which are applicable in the abovementioned two cases.

Although the number of suicides started increasing in July 2020, Japan experienced a decline in suicide deaths in the initial phase of the pandemic. The decline may be explained by enhanced social connectedness during times of crisis. For instance, the level of social connectedness and altruism is known to increase in the aftermath of natural disasters,23 and if natural disasters and the current pandemic share certain similarities, then enhanced connectedness might have worked as a protective factor with regard to suicide risks.

Limitations of this study

This study has several limitations. First, our analysis used provisional monthly data on suicide deaths, which may be corrected upward in subsequent months. Thus, any reported decline should be interpreted with caution. Second, our data on suicide deaths are aggregate in nature and our study remains descriptive. Our analysis could not control for the impacts of confounders because the NPA does not release individual-level data. Some important potential contributing factors, including macroeconomic indicators and the incidence of intimate partner violence, could not be explicitly included in the analysis because reliable data were not yet available. Thus, the factors discussed above are merely suggestive and whether they had causal effects on the observed increase remains to be investigated in future studies. Third, our online surveys relied on the commercial panel of respondents who were not randomly sampled from the general population. Thus, the survey data may not be fully representative of the general population in Japan.

Despite these limitations, the present study makes an important contribution to the scientific community by reporting the trajectories of suicide deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic and by highlighting the most vulnerable populations during this unprecedented public health crisis. Suicide is a serious public health issue that can affect any country, with more than 800 000 individuals dying by suicide every year globally.24 The experience in Japan may provide valuable implications for other countries. Given that the most affected industries were those mainly served by women in many other countries, it is likely that women constitute one of the highest risk groups for suicide in those countries as well. Similarly, since many countries also introduced school closures during the peak period of the pandemic, future studies should investigate the impact of school closures on schoolchildren and university students. The results of our study strongly indicate that continuous monitoring of mental health and appropriate suicide prevention efforts are necessary during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary Material

Michiko Ueda, Associate Professor

Robert Nordström, Graduate Student

Tetsuya Matsubayashi, Professor

Contributor Information

Michiko Ueda, Faculty of Political Science and Economics, Waseda University, Shinjuku, Tokyo 169-8050, Japan.

Robert Nordström, Faculty of Political Science and Economics, Waseda University, Shinjuku, Tokyo 169-8050, Japan.

Tetsuya Matsubayashi, Osaka School of International Public Policy, Osaka University, Toyonaka, Osaka 560-0043, Japan.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding statement

This work was financially supported by JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research Grant Number 20H01584. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. O'Connor RC, Wetherall K, Cleare S et al. Mental health and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. Br J Psychiatry 2020;21:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7(10):883–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7(6):468–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kawohl W, Nordt C. COVID-19, unemployment, and suicide. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7(5):389–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Niederkrotenthaler T, Gunnell D, Arensman E et al. Suicide research, prevention, and COVID-19. Crisis 2020;41(5):321–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Norstrom T, Gronqvist H. The great recession, unemployment and suicide. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69(2):110–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang S, Stuckler D, Yip P et al. Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: time trend study in 54 countries. BMJ 2013. British Medical Journal Publishing Group;347:f5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Calderon-Anyosa RJC, Kaufman JS. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown policy on homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle deaths in Peru. Prev Med 2021. February 2021;106331:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim AM. The short-term impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on suicides in Korea. Psychiatry Res 2021. Jan;295:113632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tanaka T, Okamoto S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat Hum Behav 2021;5(2):229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ministry of Health . Labour and Welfare. On the Number of COVID-19 Cases. [Internet]. 2020. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/covid-19/kokunainohasseijoukyou.html#h2_1 (1 December 2020, date last accessed).

- 12. Ministry of Health . Labour and Welfare. Suicide Statistics: Suicide Statistics by Region [Internet]. 2020. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000140901.html (24 November 2020, date last accessed).

- 13. National Police Agency . Suicide Statistics as of October 2020 [Internet]. 2020. https://www.npa.go.jp/publications/statistics/safetylife/jisatsu.html (30 November 2020, date last accessed).

- 14. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA 1999;282(18):1737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Löwe B. a brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(10):1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Statistics Bureau of Japan . Summary of the 2020 Labor Survey Results. [Internet]. 2020. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/sokuhou/tsuki/index.html (5 December 2020, date last accessed).

- 17. Ueda M, Stickley A, Sueki H et al. Mental health status of the general population in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2020;74(9):505–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Center for Child Health and Development . Report on the Second Survey on the Novel Coronavirus and Children. [Internet]. 2020. https://www.ncchd.go.jp/center/activity/covid19_kodomo/report/report_02.html (3 October 2020, date last accessed).

- 19. Matsubayashi T, Ueda M, Yoshikawa K. School and seasonality in youth suicide: evidence from Japan. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70(11):1122–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology . Survey on Higher Education Intitutions Regarding the Teaching Style in the Fall Semester [Internet]. 2020. https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20200915_mxt_kouhou01-000004520_1.pdf (3 October 2020, date last accessed).

- 21. Fahey RA, Matsubayashi T, Ueda M. Tracking the Werther Effect on social media: emotional responses to prominent suicide deaths on twitter and subsequent increases in suicide. Soc Sci Med 2018;219:19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ueda M, Mori K, Matsubayashi T et al. Tweeting celebrity suicides: users’ reaction to prominent suicide deaths on Twitter and subsequent increases in actual suicides. Soc Sci Med 2017. Sep;189:158–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsubayashi T, Sawada Y, Ueda M. Natural disasters and suicide: evidence from Japan. Soc Sci Med 2013;82:126–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Health Organization . Preventing Suicide. 2014. https://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/ (3 October 2020, date last accessed).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.