Abstract

Background

Indoor environments are considered one of the main settings for transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Households in particular represent a close-contact environment with high probability of transmission between persons of different ages and roles in society.

Methods

Households with a laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 positive case in the Netherlands (March-May 2020) were included. At least 3 home visits were performed during 4-6 weeks of follow-up, collecting naso- and oropharyngeal swabs, oral fluid, feces and blood samples from all household members for molecular and serological analyses. Symptoms were recorded from 2 weeks before the first visit through to the final visit. Infection secondary attack rates (SAR) were estimated with logistic regression. A transmission model was used to assess household transmission routes.

Results

A total of 55 households with 187 household contacts were included. In 17 households no transmission took place; in 11 households all persons were infected. Estimated infection SARs were high, ranging from 35% (95% confidence interval [CI], 24%-46%) in children to 51% (95% CI, 39%-63%) in adults. Estimated transmission rates in the household were high, with reduced susceptibility of children compared with adolescents and adults (0.67; 95% CI, .40-1.1).

Conclusion

Estimated infection SARs were higher than reported in earlier household studies, presumably owing to our dense sampling protocol. Children were shown to be less susceptible than adults, but the estimated infection SAR in children was still high. Our results reinforce the role of households as one of the main multipliers of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the population.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, secondary attack rate, household study, transmission model

We performed a household study and found higher infection secondary attack rates for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 than reported earlier. This is probably due to a dense sampling strategy; including sampling at multiple time points and anatomical sites.

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 [1]. Starting with an outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology, the causative agent, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was identified in early January 2020 [2]. Since then, the virus has spread rapidly across the world [3], globally disrupting day-to-day life and causing substantial excess morbidity, mortality, and economic recession [4, 5].

Evidence from case and cluster reports shows that SARS-CoV-2 is largely spread through respiratory droplets from infected persons, with proper distancing and indoor air ventilation being significant factors that reduce the risk of transmission [6]. Therefore, social distancing measures are important to reduce transmission, and most countries have instated strategies based on this premise. In the Netherlands, the first COVID-19 case was detected on 27 February 2020 [7]. In March, the Dutch government mandated a partial lockdown, characterized by social distancing; self-quarantine and self-isolation orders; closing of schools, bars, and restaurants; and urging people to work from home [8]. These measures generally increased the time spent at home. As household members live in close contact, it is difficult to attain a proper physical distance after a COVID-19 diagnosis of a household contact. In combination with evidence that a sizeable fraction of transmission events occur presymptomatically, the household constitutes a high-risk setting for SARS-CoV-2 transmission [9].

The infection secondary attack rate (SAR) of SARS-CoV-2 infection among household contacts is a useful measure to gauge the risk of transmission in this close-contact setting. It provides insight into the susceptibility of contacts and infectiousness of cases given certain characteristics, such as age, gender, household size, and severity of infection. Household studies performed in the first 6 months of the pandemic, mostly in China, found a relatively high household infection SAR of 15%–22% [10]. In most countries, pediatric patients are underrepresented in the statistics of the COVID-19 outbreak, and children usually exhibit mild symptoms [11, 12]. If children have lower susceptibility or infectiousness, this can have important implications for strategies to curb the spread of SARS-CoV-2. If children are not a significant driver in the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the effect of measures on the spread of SARS-CoV-2 might not outweigh the harmful side effects, such as the impact of school closures on the mental and social health of children. Previous household studies observed that the SAR was significantly higher for adult contacts compared with child contacts [10]. However, most studies only tested household contacts with COVID-19–related symptoms, relied only on reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in nasopharyngeal swabs, and did not perform any follow-up sampling. These studies may have missed mild, pre-, or asymptomatic cases, especially in children [13, 14]. In the present study, all household contacts were tested as soon as possible after a laboratory-confirmed infection in the household was established and subsequently followed up for 4–6 weeks. A dense sampling strategy was used that included sampling from various anatomical sites while using multiple molecular and serological diagnostic methods to establish infection. This sampling strategy increases the chance of detecting all SARS-CoV-2–infected household contacts. It also increases the chance of determining transmission routes, including asymptomatic transmission, as accurately as possible [10]. Our main aims in this study were to estimate SARs and determine factors that impact susceptibility and infectiousness, stratified by age of household contacts.

METHODS

This study is an update of a generic stand-by protocol drafted in 2006 to quickly initiate scientific research in the case of an outbreak of an emerging pathogen [15]. The generic protocol was tailored to the current COVID-19 pandemic with input from the World Health Organization First Few Hundred protocol [16]. A prospective cohort study was performed following households where 1 household member was tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in the period 24 March 2020–6 April 2020 (1 household was included later on May 24).

Population

Any person aged ≥18 years who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and who had at least 1 child in their household aged <18 years and who consented to be contacted for scientific research were reported by the Public Health Service of the region of Utrecht. We contacted these persons (ie, the index cases) to request enrollment of the entire household in this study. Every household contact (persons living in the same house as the index patient) was to be enrolled in the study, except for contacts aged <1 year. Households were excluded if 1 or more of the household contacts did not want to participate in the study up front, as in that case it would not be possible to fully determine household transmission patterns.

Data Collection

Two research nurses performed the first home visit within 24 hours after inclusion to collect the informed consent forms and the first samples from all participants (see Table 1 for schedule of sample collection). Household contacts completed a questionnaire to collect demographic characteristics, medical history, travel history, antiviral drug use, symptoms, symptom onset, and hospital admission. Participants reported whether they had symptoms in the 2 weeks prior to the first visit. After the first visit, they filled in a symptoms diary for 2 weeks. A second visit was included at 2–3 weeks post-inclusion. At the last home visit at 4–6 weeks post-inclusion, participants reported whether they had developed symptoms in the weeks between the second and third home visit. We defined 3 age strata: adults aged ≥18 years, adolescents aged 12–17 years (corresponding to secondary school age), and children aged 1–11 years (corresponding to day care and primary school age).

Table 1.

Schedule of Administering Questionnaires, Symptom Diaries, and Home Visits for Sampling by a Research Nurse

| Day | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 (Range 14–21) | 35 (Range 28–42) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic questionnaire | x | |||||||||||||||

| Retrospective symptom questionnairea | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Symptom diary (on that specific day) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Serumb | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Naso- and oropharyngeal swabc | x | (x) | (x) | (x) | (x) | x | ||||||||||

| Oral fluid | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Fecesd | x | x | x |

a This questionnaire included questions on symptoms on the day of that home visit and symptoms in the 2 weeks prior to the first home visit or the symptoms between the last and second home visit.

b Participants aged ≥16 years: total of 18.5 mL. Participants with symptoms within 4 days prior to the first home visit were asked to provide 3 extra tubes of 8 mL for additional cellular immunity assays. Participants aged <16 years: total of 13.5 mL. Participants also had the option of capillary finger blood collection (0.5 mL) instead of venous blood collection.

c Participants aged ≥16 years additionally had the option to get a naso- and oropharyngeal swab every 3 days (days 3, 6, 9, and 12). Participants of all ages without a previous positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 result who developed acute symptoms also received an additional naso- and oropharyngeal swab as soon as possible after developing these symptoms. A naso- and oropharyngeal swab was not collected for the index case at the first home visit, as these persons were already swabbed a few days before.

d Feces samples were not collected by the nurse visiting the household. Participants received a feces collection kit at the first home visit and were asked to collect feces within 3 days after the first, second, and third home visit.

Molecular Diagnostics and Serological Analysis

Total nucleic acid was extracted from the nasopharyngeal swab (NP), oropharyngeal swab (OP), oral fluid, and feces specimens using MagNApure 96 with the total nucleic acid kit small volume and elution in 50 µL. RT-quantitative (q) PCR was performed on 5 µL extract using TaqMan Fast Virus 1-Step Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) on the Roche LC480II thermal cycler with SARS-like beta coronavirus (Sarbeco)–specific E-gene primers and probe, as described previously [17]. As no other Sarbeco viruses are currently detected in humans, a positive Sarbeco E-gene RT-qPCR is validly taken as positive for SARS-CoV-2. The results of the NP and OP swab tests were combined into 1 result: upper respiratory tract (URT) negative (NP and OP negative) or positive (NP and/or OP positive). For detection of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, we used the Wantai total immunoglobulin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as described previously [18].

Classification of Index and Primary Cases

Laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined as either at least 1 positive PCR on any of the clinical samples taken during follow-up and/or detection of antibodies at any sampling time point. Every index case was, by definition, infected, as they had at least 1 positive PCR on an URT swab.

Symptoms and Severity of COVID-19

The day of symptom onset as reported by the participant was set as the first day of illness. Participants were considered symptomatic if at least 1 of the following symptoms occurred at any time point: respiratory symptoms (including sore throat, cough, dyspnea or other respiratory difficulties, rhinorrhea), fever, chills, headache, anosmia or ageusia, muscle pain, joint ache, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, or fatigue. For household contacts, symptom onset that occurred more than 2 weeks prior to the first day of illness or the first positive test result of the index case was considered not related to SARS-CoV-2 transmission within the household.

A differentiation was made between mild, moderate, and severe COVID-19 based on self-reported symptoms or hospital admission [19]. We defined mild COVID-19 cases as laboratory-confirmed cases that showed any clinical symptoms. Moderate COVID-19 cases showed clinical signs of pneumonia, including dyspnea, and severe COVID-19 cases reported dyspnea and consulted a health professional (eg, went to an emergency room) for their symptoms or reported having been admitted to the hospital for COVID-19.

Primary Case

In every household, a primary case (the most likely first case of the household) was determined based on laboratory confirmation, symptom onset, and travel history. As a default, the index case was considered the primary case, and a household contact was only considered the primary case if they had a laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection with a symptom onset at least 2–14 days before the index case. Household contacts who had symptoms more than 2 weeks before the index case were included in the analysis as susceptible to COVID-19 unless they were already seropositive at day 1.

Statistical Analyses

Secondary Attack Rate

Household SARs were estimated excluding the index case (ie, the laboratory-confirmed person that led to inclusion of the household in the study) but including the primary case. This corresponds to common practice as reliable information on the primary case in the household often is lacking [20, 21]. To take the clustered nature of the data into account, SARs were estimated with a logistic regression using generalized estimating equations, with household as the unit of clustering and assuming an exchangeable correlation structure. Analyses were performed using 3 age strata as defined above and using covariates sex, household size, and severity of infection of the index case. Model selection was based on the quasi information criterion for small sample sizes (QICc). Analyses were carried out in R (version 3.6.0) using the geepack (version 1.5.1) and emmeans (version 1.3.1) packages [22–26].

Transmission Model

In addition to the estimates of the SAR, we analyzed the data using the final size distribution of a stochastic susceptible-exposed-infected-recovered transmission model. In this model, persons are classified as susceptible (S), infected but not yet infectious (E), infected and infectious (I), or recovered and immune (R). The appeal of these analyses are that the estimated parameters have a biological interpretation (susceptibility, infectiousness), the final size distributions are invariant with respect to the latent-period distribution, and the different assumptions on the distribution of the infectious period can be incorporated [27, 28]. With respect to the contact process, we assumed frequency-dependent transmission as this mode of transmission is preferred over density-dependent transmission by information criteria (not shown) [29]. Time is rescaled in units of the infectious period, and we assumed a realistic variation in the infectious period corresponding to an infectious period of 6–10 days. Here, because households were included only if an infected person was present, the final size distributions needed to be conditioned on the presence of an infected index case if the index case was not also the primary case [28]. Such conditioning was applied for 17 households (Figure 1). Model selection was performed using leave-one-out cross-validation information criterion (LOOIC), a measure for predictive performance [29, 30]. Estimation was performed in a Bayesian setting using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo implemented in Stan (version 2.21.2) [31]. Details will be made available on our digital repository https://github.com/mvboven/COVID-19-FFX.

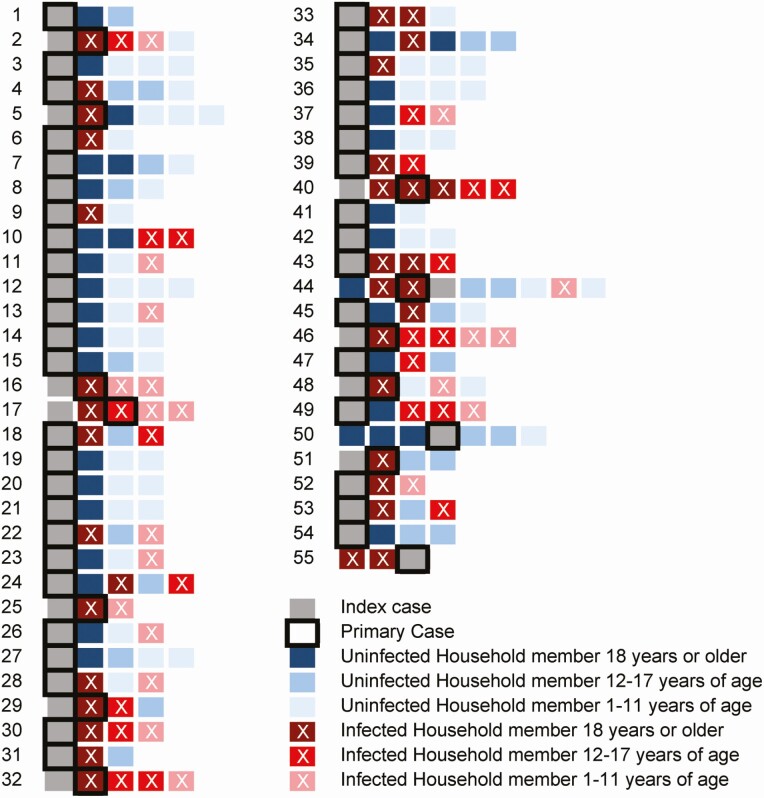

Figure 1.

Overview of transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 within households. Each row represents a household, and each square represents a household member. The gray squares are the index cases, and the most likely primary case is indicated by a black border. Blue squares indicate uninfected household members, and red squares indicate infected household members, with lighter colors indicating a younger age group. The squares are ordered by age, but the first 2 squares are always 2 spouses and the parents/guardians of the children.

Ethics

The University Medical Center Utrecht Medical-Ethical Review Committee approved the generic and adapted study protocols. All participants aged >12 years gave written informed consent; parents or guardians of participating children aged <16 years gave written informed consent for participation; and both parents and children had to give consent for children aged 12–16 years.

RESULTS

Descriptive Analysis

Fifty-five households were included, with 242 participants. Each household had an index case (55 participants) and the other 187 participants were household contacts (Table 2). Household size varied from 3 to 9 persons (Figure 1). Index cases were predominantly female (n = 40, 72.7%) and healthcare workers (n = 41, 75.9%). Seven index cases were admitted to the hospital before or during participation in the study, and none of the other cases in the household required hospitalization. In 10 of the 55 households, the index case was observed not to be the primary case; in 9 households, this was determined to be another adult, and in 1 household, an adolescent contact. In 17 households, no transmission took place; in 11 households, every member got infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 1). In children, fewer SARS-CoV-2 infections were found compared with adolescent and adult household contacts. In total, 51% of adults, 46% of adolescents, and 30% of children got infected. Children and adolescent household contacts were less often symptomatic than adult contacts. Adults were also more likely to have a severe infection (37%) compared with adolescents (15%) and children (5%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Study Population

| All Household Members | Index Cases | All Household Contacts | Adult Household Contacts (Aged≥18 Years) | Adolescent Household Contacts (Aged 12–17 Years) | Children Household Contacts (Aged 1–11 Years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N (%) Unless Stated Otherwise | N = 242a | N = 55a | N = 187a | N = 71a | N = 46a | N = 70a |

| Age at first home visit, years | Mean (standard deviation) | 27 (18.4) | 43 (9.0) | 22 (17.8) | 42 (12.8) | 14 (1.4) | 7 (3.0) |

| Gender (male) | 114 (47.1) | 15 (27.3) | 99 (52.9) | 44 (62.0) | 20 (43.5) | 35 (50.0) | |

| Education level | |||||||

| Low | 1 (1.9) | 11 (15.9) | |||||

| Medium | 17 (31.5) | 22 (31.9) | |||||

| High | 36 (66.7) | 36 (52.2) | |||||

| Healthcare worker | 41 (75.9) | 13 (19.1) | |||||

| Comorbidity (1 or more)b | 50 (21.1) | 20 (37.0) | 30 (16.5) | 16 (23.2) | 8 (18.2) | 6 (8.7) | |

| Symptomatic | |||||||

| 2 weeks prior to first home visit | 158 (67.0) | 51 (94.4) | 107 (58.9) | 49 (71) | 24 (54.6) | 34 (49.3) | |

| At first home visit | 126 (53.4) | 44 (81.5) | 82 (45.1) | 41 (59.4) | 16 (36.4) | 25 (36.2) | |

| During follow-up | 126 (52.1) | 47 (85.5) | 79 (42.3) | 38 (53.5) | 17 (37.0) | 24 (34.3) | |

| Anytime during the study | 184 (78.0) | 54 (100) | 130 (71.4) | 56 (81.2) | 28 (63.6) | 46 (66.7) | |

| Hospital admission (related to coronavirus disease 2019) | 7 (12.7) | ||||||

| Laboratory-confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection | 133 (55.0) | 55 (100) | 78 (41.7) | 36 (50.7) | 21 (45.7) | 21 (30.0) | |

| Severity of infection | |||||||

| Asymptomatic | 6 (4.7) | 0 | 6 (8.0) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (15.0) | 2 (10.0) | |

| Mild | 73 (56.6) | 21 (38.9) | 52 (69.3) | 21 (60.0) | 14 (70.0) | 17 (85) | |

| Moderate | 19 (14.7) | 11 (20.4) | 8 (10.7) | 6 (17.1) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | |

| Severe | 31 (24.0) | 22 (40.7) | 9 (12.0) | 7 (20.0) | 2 (10.0) | 0 |

a Six participants did not fill in the questionnaires: 1 index case, 2 adult contacts, 2 adolescent contacts, and 1 child contact. Information on education level, occupation, comorbidity, symptoms, and severity is missing.

b Comorbidities include asthma; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; chronic bronchitis or other chronic lung diseases; cardiovascular diseases; diabetes; immune disorders or received treatment causing immunocompromised state; and chronic kidney, liver, or neuromuscular disorders. Obesity, hypertension, hay fever, and other allergies are not included.

Secondary Attack Rates

Overall, the estimated household infection SAR was 43% (95% CI, 33%–53%). In univariable analysis, only age was significant at the 5% level (P = .036), while sex (P = .11), household size (P = .64), being a healthcare worker (P = .28), and severity of infection of the index case (P = .30) were all not significantly associated with the outcome (P > .10). In a multivariable analysis that included sex and age group (child, adolescent, adults), being a child was strongly associated with decreased probability of infection (P = .006), while female sex was not significantly associated with increased probability of infection (P = .053). The univariable model with age was the preferred model based on QICc. Estimates of the infection SARs with this model show that the SAR is lowest in children (35%, 95% CI, 24%–46%), higher in adolescents (0.41, 95% CI, 27%–56%), and highest in adults (51%, 95% CI, 39%–63%; see Supplementary Table 1).

Household Transmission

Building on the results of the SAR estimates, we analyzed transmission models that differed with respect to assumptions on the susceptibility and transmissibility of age groups (children, adolescents, adults). Table 3 shows the results. In the unstructured model, the transmission rate was estimated at 1.2 per infectious period, which implies that an infected person infects on average 1.2 persons in an as of yet uninfected household. Given our assumption on frequency-dependent transmission, this implies that the probability of direct transmission from an infected to an uninfected person (ie, without taking indirect transmission via intermediate persons into account) in a household of 4 persons would be 1-exp[–1.2/4] = 0.26. Overall, differences between models were modest, and the data did not allow estimation of more than 2–3 parameters. Judged by the LOOIC information criterion, the unstructured model and the model with a parameter for the susceptibility of children performed best. Estimated susceptibility of children in the model with variable susceptibility was 0.67 (95% CI, .40–1.1), meaning children have 67% of the susceptibility of adults.

Table 3.

Estimation of Household Transmission Rates

| Transmission Ratea | Transmissibility of Childrenb | Transmissibility of Adolescentsb | Susceptibility of Childrenb | Susceptibility of Adolescentsb | Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation Information Criterion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstructured | 1.2 (0.94, 1.5) | ... | ... | ... | ... | 185.6 |

| Age-dependent transmissibility | 1.0 (0.72, 1.4) | 0.73 (0.042, 2.6) | 2.7 (0.98, 5.6) | ... | ... | 186.4 |

| Age-dependent susceptibility | 1.4 (0.96, 2.1) | ... | ... | 0.65 (0.35, 1.1) | 0.89 (0.47, 1.6) | 186.5 |

| Full age-dependence | 1.2 (0.79, 2.0) | 0.77 (0.047, 2.6) | 2.3 (0.79, 5.2) | 0.74 (0.39, 1.4) | 0.93 (0.51, 1.7) | 189.1 |

| Susceptibility of children | 1.4 (1.0, 1.8) | ... | ... | 0.67 (0.40, 1.1) | … | 184.6 |

Parameter estimates are represented by posterior medians and 95% credible intervals.

aRefers to the reference class, adults. Unit: per infectious period (see Methods section).

bTransmissibility and susceptibility are relative to adults and include intrinsic differences between groups (eg, differences in viral loads) and varying rates at which contacts are made.

DISCUSSION

Estimated household infection SARs in our study were high (43%) and substantially higher than reported in earlier studies (reviewed in [10]). Transmission model analyses corroborated this finding and, in addition, revealed that children aged <12 years had reduced susceptibility compared with adolescents and adults. Neither household size nor severity of infection of the index case had a significant impact on household infection SAR or household transmission.

In our study, we confirmed that the infection SAR for SARS-CoV-2 is higher than the infection SARs of related emerging coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV (6.0%) and Middle East respiratory syndrome-CoV (3.5%) [10]. High estimated SARs are also in line with observations from surveillance data and cluster reports that the household is the most frequently reported setting of infection [32]. Our study differs from earlier household studies for SAR-CoV-2 in that we observed substantially higher SARs [10, 33]. In fact, only a few studies reported estimates that were somewhat similar to our estimates (32%–38% vs 43%) [34, 35]. A systematic review showed that estimated infection SARs increase with frequency of testing [33] and that most of the earlier studies analyzed existing data from contact tracing procedures performed by local public health services, monitored household contacts only during quarantine without additional follow-up, or only tested symptomatic household contacts. A few studies did test all household contacts irrespective of symptoms. However, none had a follow-up of more than 4 weeks or an increased sensitivity for case finding through assessment of multiple sample types and diagnostic methods. Thus, we believe that our estimates of SARs may be more representative of the true household infection SARs than those presented in earlier studies.

A systematic review based on 18 studies concluded that children are at lower risk of infection than adults, although there was substantial heterogeneity in study design and in population characteristics [36]. Potential contributing factors include age-specific differences in the balance between innate and adaptive immune responses [37, 38], more concomitant viral infections or cross-immunity to other coronaviruses in adolescents and adults [39–41], and physiological differences in the respiratory tract of children compared with adults [38, 42]. Irrespective of the cause, a relevant question is, how infectious are infected children to other household members? This is especially relevant as in some studies the severity of infection of the index case was associated with higher infectiousness [10, 33]. We did not find evidence for lower transmissibility of children compared with adolescents and adults, but it should be noted that our study (and, for that matter, most other household studies) may be underpowered to detect even moderate differences in age-specific transmissibility.

It is important to note 2 related limitations of our analyses. For inclusion of households, our study depended on the prevailing testing policies and infected population in different age groups. This may well have resulted in a high likelihood of selecting (symptomatic) adult index cases, such that index cases may not be representative of infections in the population. Standard practice for estimating the SAR partly solves this problem by taking into account all secondary infections in the household while leaving the index case out of the analyses [21]. Related to this is the fact that the index case may not always be the primary (ie, first sequential) case in the household [20, 21], such that standard estimates of SARs may not be indicative of transmission routes in the household. In a previous household study, researchers tried to solve this issue by including index cases and excluding primary cases [43], but this introduces bias as it would artificially increase the SAR of the prevailing type of the index cases (ie, adults). In a sensitivity analysis, we reran the analyses using logistic regression by excluding both the primary and index cases and found a relatively small impact on the estimated SARs in different age groups (not shown). The transmission model analyses do not suffer from these problems but they do require that the primary case in the household can be identified, and this is often not possible in retrospective household analyses. Finally, we did not collect information about behavioral parameters that might have influenced transmission within households. However, we assume that households adhered to the prevailing social distancing and other control measures. Wearing masks was not one of the measures advised by the Dutch government at that time. Factors we did take into account, which might make isolation and quarantine more difficult, such as household size, were not significantly associated with the outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results confirm and reinforce that the household is a main transmission source of SARS-CoV-2. Our results also underscore the need not only for isolation of infected household members but also for prompt and effective quarantine of household contacts.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the Public Health Service Utrecht for assistance in the recruitment of households. We thank Alper Çevirgel, Anneke Westerhof, Anne-Marie van den Brandt, Anoek Backx, Bas van der Veer, Elma Smeets-Roelofs, Elsa Porter, Elske Bijvank, Fion Brouwer, Francoise van Heiningen, Gabriel Goderski, Gert-Jan Godeke, Harry van Dijken, Helma Lith, Hinke ten Hulscher, Ilse Akkerman, Ilse Schinkel, Jeroen Hoeboer, Jolanda Kool, Josine van Beek, Joyce Greeber, Kim Freriks, Lidian Izeboud, Lisa Beckers, Lisa Wijsman, Liza Tymchenko, Maarten Emmelot, Maarten Vos, Margriet Bisschoff, Marieke Hoogerwerf, Marit de Lange, Marit Middeldorp, Marjan Bogaard, Marjan Kuijer, Martien Poelen, Nening Nanlohy, Olga de Bruin, Rogier Bodewes, Ruben Wiegmans, Sakinie Misiedjan, Saskia de Goede, Sharon van den Brink, Sophie van Tol, Titia Kortbeek, and Yolanda van Weert for support during the early stages of this study, household visits, and laboratory analyses. We thank Johan Reimerink, in particular, for his contributions to developing the serological assays, and Chris van Dorp (Los Alamos National Laboratory) for his support coding the final size distribution in Stan.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. ProMED International Society for Infectious Diseases. Undiagnosed pneumonia–China (Hubei): request for information. Archive Number: 20191230.6864153. Available at: https://promedmail.org/promed-post/?id=6864153%20#COVID19. Accessed 16 October 2020.

- 2. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Eng J Med 2020; 382:1199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Timeline of WHO’s response to COVID-19. Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline. Accessed 16 October 2020.

- 4. Newbold SC, Finnoff D, Thunström L, Ashworth M, Shogren JF. Effects of physical distancing to control COVID-19 on public health, the economy, and the environment. Environ Resour Econ (Dordr) 2020:1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vestergaard LS, Nielsen J, Richter L, et al. Excess all-cause mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe—preliminary pooled estimates from the EuroMOMO network, March to April 2020. Euro Surveill 2020; 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meyerowitz EA, Richterman A, Gandhi RT, Sax PE. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a review of viral, host, and environmental factors. Ann Intern Med 2021;174:69–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM). Patient with novel coronavirus COVID-19 in the Netherlands. 2020. Available at: https://www.rivm.nl/node/152811. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Minister Bruno Bruins, Minister Ingrid van Engelshoven, Minister Arie Slob, Minister Tamara van Ark. Kamerbrief met nieuwe aanvullende maatregelen om de COVID 19 uitbraak te bestrijden. Available at: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2020/03/15/covid-19-nieuwe-aanvullende-maatregelen. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun K, Wang W, Gao L, et al. Transmission heterogeneities, kinetics, and controllability of SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv 2020: doi:2020.08.09.20171132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Madewell ZJ, Yang Y, Longini IM Jr, Halloran ME, Dean NE. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e2031756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoang A, Chorath K, Moreira A, et al. COVID-19 in 7780 pediatric patients: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 2020; 24:100433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr 2020; 109:1088–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics 2020; 145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Assaker R, Colas AE, Julien-Marsollier F, et al. Presenting symptoms of COVID-19 in children: a meta-analysis of published studies. Br J Anaesth 2020; 125:e330–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Gageldonk-Lafeber AB, van der Sande MA, Meijer A, et al. Utility of the first few100 approach during the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2012; 1:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization. The First Few X (FFX) cases and contact investigation protocol for 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/20200129-generic-ffx-protocol-2019-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=595eb313_4. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill 2020; 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rijkers G, Murk JL, Wintermans B, et al. Differences in antibody kinetics and functionality between severe and mild severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:1265–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization. Clinical Management of COVID-19, 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-covid-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cummings DAT, Lessler J. Design and analysis of vaccine studies: by M. Elizabeth Halloran, Ira M. Longini, Jr., and Claudio J. Struchiner. Am J Epidemiol 2011; 174:872–3. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Halloran ME, Longini IM, Struchiner CJ.. Design and analysis of vaccine studies. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22. R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Halekoh U, Højsgaard S, Yan J. The R package GEEPACK for generalized estimating equations. J Stat Softw 2006; 15. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yan J. geepack: yet another package for generalized estimating equations. R-News 2002; 2:12–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yan J, Fine J. Estimating equations for association structures. Stat Med 2004; 23:859–74; discussion 75-7,79-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lenth R. emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.4.8., 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ball F, O’Neill P. The distribution of general final state random variables for stochastic epidemic models. J Appl Probab 2016; 36:473–91. [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Greeff SC, de Melker HE, Westerhof A, Schellekens JF, Mooi FR, van Boven M. Estimation of household transmission rates of pertussis and the effect of cocooning vaccination strategies on infant pertussis. Epidemiology 2012; 23:852–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vehtari A, Gelman A, Gabry J. Practical Bayesian model evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Stat Comput 2016; 27:1413–32. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Watanabe S. A widely applicable Bayesian information criterion. J Mach Learn Res 2013; 14:867–97. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carpenter B, Gelman A, Hoffman MD, et al. Stan: a probabilistic programming language. J Stat Softw 2017; 76:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leclerc QJ, Fuller NM, Knight LE, Funk S, Knight GM; CMMID COVID-19 Working Group . What settings have been linked to SARS-CoV-2 transmission clusters? Wellcome Open Res 2020; 5:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fung HF, Martinez L, Alarid-Escudero F, et al. The household secondary attack rate of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): a rapid review. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73(Suppl 2): S138–S45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rosenberg ES, Dufort EM, Blog DS, et al. ; New York State Coronavirus 2019 Response Team . COVID-19 testing, epidemic features, hospital outcomes, and household prevalence, New York State—March 2020. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:1953–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jiang XL, Zhang XL, Zhao XN, et al. Transmission potential of asymptomatic and paucisymptomatic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections: a 3-family cluster study in China. J Infect Dis 2020; 221:1948–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Viner RM, Mytton OT, Bonell C, et al. Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection among children and adolescents compared with adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2021; 175:143–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schulien I, Kemming J, Oberhardt V, et al. Characterization of pre-existing and induced SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells. Nat Med 2021; 27:78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Why is COVID-19 less severe in children? A review of the proposed mechanisms underlying the age-related difference in severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections. Arch Dis Child 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brodin P. Why is COVID-19 so mild in children? Acta Paediatr 2020; 109:1082–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Devulapalli CS. COVID-19 is milder in children possibly due to cross-immunity. Acta Paediatr 2020; 109:2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhu L, Lu X, Chen L. Possible causes for decreased susceptibility of children to coronavirus. Pediatr Res 2020; 88:342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yavuz S, Kesici S, Bayrakci B. Physiological advantages of children against COVID-19. Acta Paediatr 2020; 109:1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lewis NM, Chu VT, Ye D, et al. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.