Abstract

Objectives

We performed a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to provide updated information regarding the clinical efficacy of remdesivir in treating coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Methods

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, clinical trial registries of ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform were searched for relevant articles published up to 18 November 2020.

Results

Five RCTs, including 13 544 patients, were included in this meta-analysis. Among them, 3839 and 391 patients were assigned to the 10 day and 5 day remdesivir regimens, respectively. Patients receiving 5 day remdesivir therapy presented greater clinical improvement than those in the control group [OR = 1.68 (95% CI 1.18–2.40)], with no significant difference observed between the 10 day and placebo groups [OR = 1.23 (95% CI 0.90–1.68)]. Patients receiving remdesivir revealed a greater likelihood of discharge [10 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.32 (95% CI 1.09–1.60); 5 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.73 (95% CI 1.28–2.35)] and recovery [10 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.29 (95% CI 1.03–1.60); 5 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.80 (95% CI 1.31–2.48)] than those in the control group. In contrast, no mortality benefit was observed following remdesivir therapy. Furthermore, no significant association was observed between remdesivir treatment and an increased risk of adverse events.

Conclusions

Remdesivir can help improve the clinical outcome of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and a 5 day regimen, instead of a 10 day regimen, may be sufficient for treatment. Moreover, remdesivir appears as tolerable as other comparators or placebo.

Introduction

As of 25 January 2021, more than 98 million coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases have been reported globally.1 Moreover, COVID-19 has resulted in nearly 2.1 million deaths worldwide, with a case fatality rate of 2.2%.1 Most importantly, the mortality and disease severity among patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is increasing.2,3 To manage this pandemic, significant efforts have been made worldwide to prevent COVID-19 outbreaks and develop appropriate treatments against severe SARS-CoV-2 infections to save human lives.4–10 Unfortunately, antiviral treatments effective in patients with COVID-19 remain limited.4

Since the first reported case that was successfully treated with remdesivir in the USA in March 2020,5 remdesivir became a promising anti-SARS-CoV-2 agent4 and thereafter its usefulness has been reported in several observational studies.11–17 Furthermore, several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are evaluating the clinical efficacy of remdesivir in COVID-19.18 Moreover, several meta-analyses of studies regarding this issue have been conducted.4,19–23 However, the level of evidence from these studies remains limited owing to the small number of published RCTs and the heterogeneity among these studies. Recently, the final reports of two large RCTs, the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT-1)24 and the WHO Solidarity trial,25 have been published. As most previous meta-analyses did not include the final results of these two RCTs,24,25 we conducted this systematic review and network meta-analysis to provide updated information regarding the clinical efficacy of remdesivir in the treatment of COVID-19.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,26 and was registered at PROSPERO with the number CRD42020219133.

The literature search was performed in electronic databases, including PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Library for relevant articles published from 1 January 2020 to 18 November 2020. The key words of COVID-19 [including coronavirus infections (MeSH term), corona virus, coronavirus infection, coronavir*, covid* and sars-cov-2 (text words)] and remdesivir [including remdesivir (MeSH term), Veklury and GS-5734 (text words)] were employed. Details regarding the search strategy are presented in Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online. Clinical trial registries of ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) were searched for registered trials. Furthermore, the reference list from relevant articles and the preprint service of medRxiv.org were searched manually for additional eligible articles. The articles were not limited to those published in English.

Study selection and data extraction

Two investigators (C.-H.C. and C.-Y.W.) independently screened and reviewed each study. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) patients with COVID-19 infection; (2) aged ≥18 years; (3) intervention with remdesivir; (4) compared with placebo, standard of care, or different treatment regimens of remdesivir; (5) RCT; and (6) evaluated outcome and efficacy, including mortality or clinical improvement. If there were any disagreements, a third investigator (C.-C.L.) was consulted.

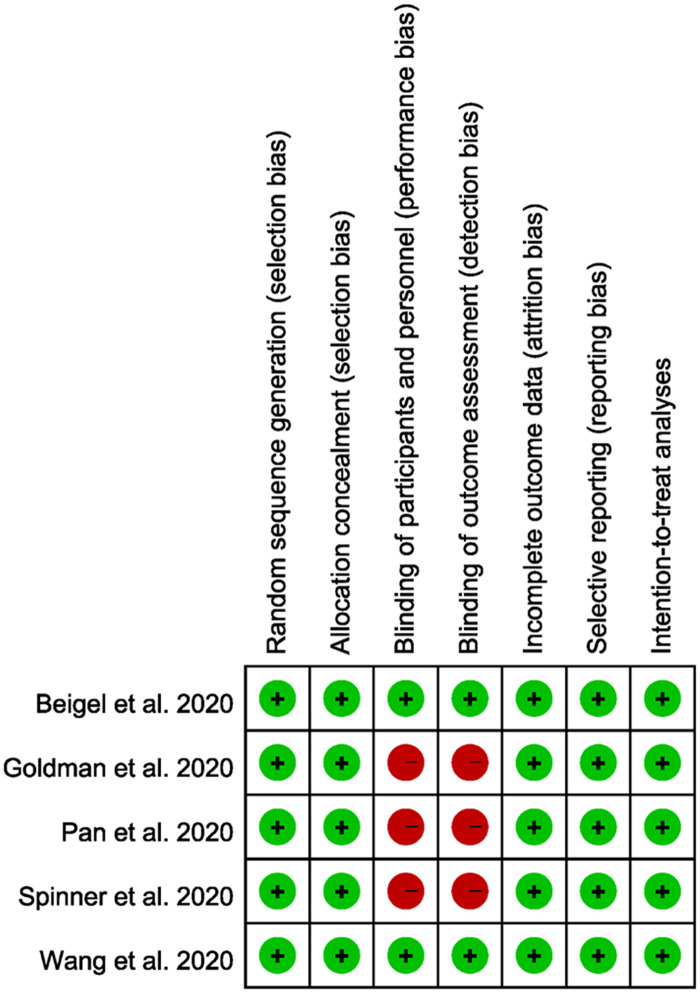

Quality assessment

The quality of each included study was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. Two reviewers subjectively reviewed all included studies and rated them as ‘low risk’, ‘high risk’ or ‘unclear’ according to the following items: randomization sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and inclusion of ITT analyses.

Outcome measure and statistical analysis

Outcomes of interest included: (1) clinical improvement, defined as at least a 2-point improvement from baseline on the ordinal scale of clinical status; (2) mortality; (3) recovery; (4) discharge; (5) adverse events; (6) serious adverse events; (7) time to clinical improvement; (8) time to mortality; and (9) time to recovery. ORs were considered as measures of effect size for categorical outcomes and HRs were used for time-to-event outcomes. Statistical significance was considered if the 95% CI did not include 1 for OR or HR.

A network meta-analysis with a random-effects model was performed for data synthesis, combining direct and indirect evidence across studies that evaluated multiple treatments (i.e. 10 day remdesivir, 5 day remdesivir and control). A frequentist approach was performed using the R package ‘netmeta’. Patients receiving a placebo or standard of care were considered as the reference group. Cochran’s Q and I2 statistical tests were used to measure heterogeneity and inconsistency. In addition, a design-based decomposition of Cochran’s Q was performed to divide the Q-statistic into between-design inconsistency and within-design heterogeneity.27 Furthermore, we performed net-splitting analysis (also called node-splitting analysis) with a back-calculation method. Results for direct and indirect comparisons were split for evaluating local consistency in network meta-analysis.28 Ranking of treatment, which is an analogue of the surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA), was calculated using the P value; a higher probability indicates better treatment.29 The network graphs were also plotted for each outcome. The nodes represent treatment and the edges represent the number of studies that provided results of direct comparison between the two treatments. The size of the nodes was proportional to the number of patients included in the treatment and the thickness of the edges was proportional to the number of included studies with direct evidence.

Results

Literature search and evaluation for study inclusion

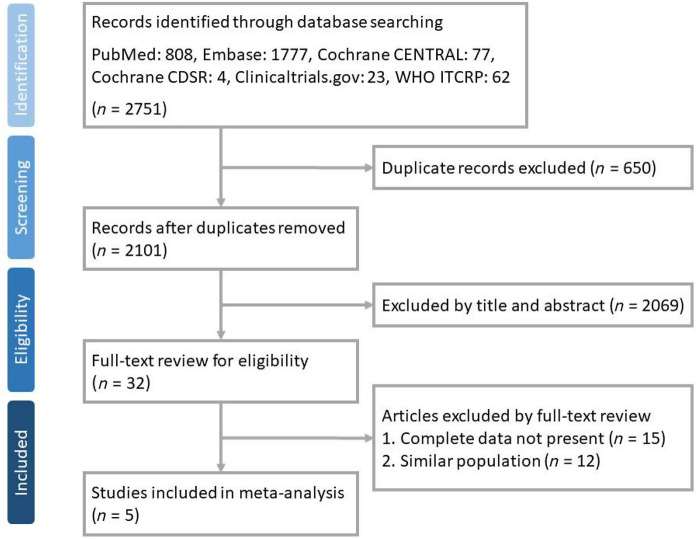

In total, 2751 articles were perused in PubMed (n = 808), Embase (n = 1777), Cochrane CENTRAL (n = 77), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (n = 4), ClinicalTrials.gov (n = 23) and WHO ICTRP (n = 62). Thirty-two articles were selected after removing duplicate records (n = 650) and ineligible articles by reviewing the title and abstract (n = 2069). Following the full-text review process, 13 articles were excluded and 5 articles were finally included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of five RCTs,24,25,30–32 three of which25,30,31 were open-label trials, whereas two24,32 were double-blind studies; all were multicentre studies24,25,30–32 and four were multinational studies.24,25,30,31 Although all included RCTs24,25,30–32 enrolled hospitalized patients with COVID-19, their inclusion criteria had some variations. Overall, 13 544 patients were included in the meta-analysis. Among them, 3839 and 391 patients were assigned to the 10 day and 5 day remdesivir regimens, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study, year | Study design | Study sites | Study subjects | Study group | Control group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beigel et al., 2020 | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial | 73 sites in 10 countries | Adults who were hospitalized with COVID-19 and presented evidence of lower respiratory tract infection (n = 1062) | Remdesivir 200 mg on Day 1 and 100 mg on Days 2–10 in single, daily infusions (n = 541) | Placebo (n = 521) |

| Pan et al., 2020 | Randomized, open-label trial | 405 hospitals in 30 countries | Adults who were hospitalized with COVID-19 (n = 11 266) | Remdesivir 200 mg on Day 1 and 100 mg on Days 2–10 in single, daily infusions (n = 2750) | Hydroxychloroquine (n = 954); lopinavir (n = 1411), interferon + lopinavir (n = 651), interferon (n = 1412); standard of care without drug (n = 4088) |

| Goldman et al., 2020 | Randomized, open-label, Phase 3 trial | 55 sites in 8 countries | Hospitalized patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, SpO2 ≤ 94% on ambient air and radiological evidence of pneumonia (n = 397) | Remdesivir 5 day course, 200 mg on Day 1 and 100 mg on Days 2–5 in single, daily infusions (n = 200) | Remdesivir 10 day course, 200 mg on Day 1 and 100 mg on Days 2–9 in single, daily infusions (n = 197) |

| Spinner et al., 2020 | Randomized, open-label trial | 105 hospitals in the USA, Europe, and Asia | Hospitalized patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and moderate COVID-19 pneumonia (n = 582) | Remdesivir 5 day course, 200 mg on Day 1 and 100 mg on Days 2–5 in single, daily infusions (n = 191) | Standard of care (n = 200) and remdesivir 10 day course, 200 mg on Day 1 and 100 mg on Days 2–10 in single, daily infusions (n = 193) |

| Wang et al., 2020 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 10 sites in China | Hospitalized adult patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, with an interval from symptom onset to enrolment of ≤12 days, SpO2 ≤ 94% on room air or PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mm Hg and radiologically confirmed pneumonia (n = 237) | Remdesivir 200 mg on Day 1 and 100 mg on Days 2–10 in single, daily infusions (n = 158) | Placebo (n = 78) |

SpO2, oxygen saturation; PaO2/FiO2, ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen.

Clinical improvement

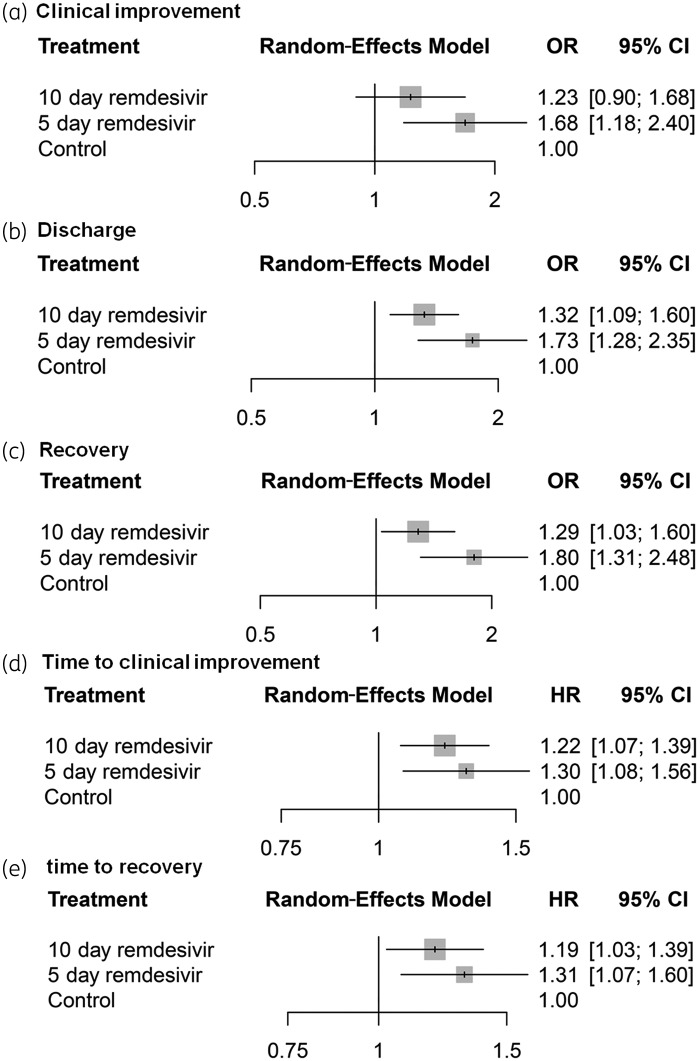

The network meta-analysis included three studies providing results for clinical improvements during the treatment period, among which one study had a three-arm design. Two direct comparisons between 10 day remdesivir therapy versus 5 day remdesivir therapy, two comparisons between 10 day remdesivir therapy versus control, and one comparison between 5 day remdesivir therapy versus control were used for the network meta-analysis. Patients receiving 5 day remdesivir therapy revealed greater clinical improvement than those in the control group [OR = 1.68 (95% CI 1.18–2.40), Figure 2a], with no significant difference observed between the 10 day treatment and placebo groups [OR = 1.23 (95% CI 0.90–1.68), Figure 2a]. The OR for 10 day remdesivir versus 5 day remdesivir was 0.73 (95% CI 0.55–0.97). Similarly, patients receiving remdesivir had a higher likelihood of discharge [10 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.32 (95% CI 1.09–1.60); 5 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.73 (95% CI 1.28–2.35); Figure 2b] and recovery [10 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.29 (95% CI 1.03–1.60); 5 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.80 (95% CI 1.31–2.48); Figure 2c] than those in the control group. A shorter time to clinical improvement [10 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.22 (95% CI 1.07–1.39); 5 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.30 (95% CI 1.08–1.56); Figure 2d] and time to recovery [10 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.19 (95% CI 1.03–1.39); 5 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.31 (95% CI 1.07–1.60); Figure 2e] were observed in the remdesivir group when compared with the control group.

Figure 2.

Forest plots among treatment strategies for clinical improvement (a), discharge (b), recovery (c), time to clinical improvement (d) and time to recovery (e).

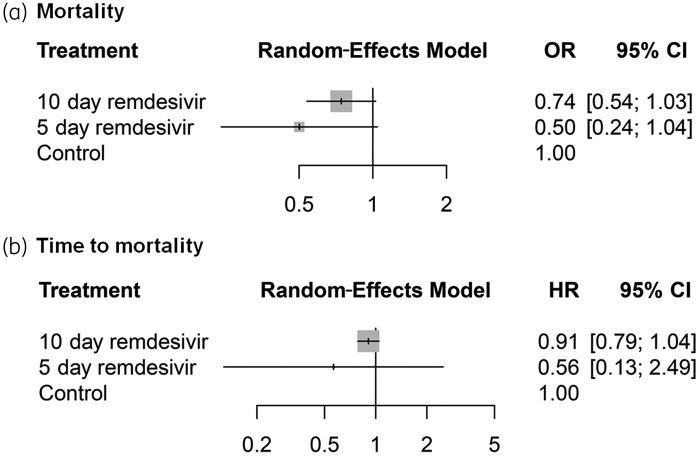

Mortality

A network meta-analysis of mortality from four studies showed that patients receiving remdesivir treatment had lower odds of mortality than those in the control group [10 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 0.74 (95% CI 0.54–1.03); 5 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 0.50 (95% CI 0.24–1.04); Figure 3a]. Higher mortality was observed in the 10 day remdesivir group than in the 5 day remdesivir group, but the results were not statistically significant [OR = 1.48 (95% CI 0.76–2.88)]. No significant data regarding time to mortality were observed in the remdesivir group when compared with the control group (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Forest plots among treatment strategies for mortality (a) and time to mortality (b).

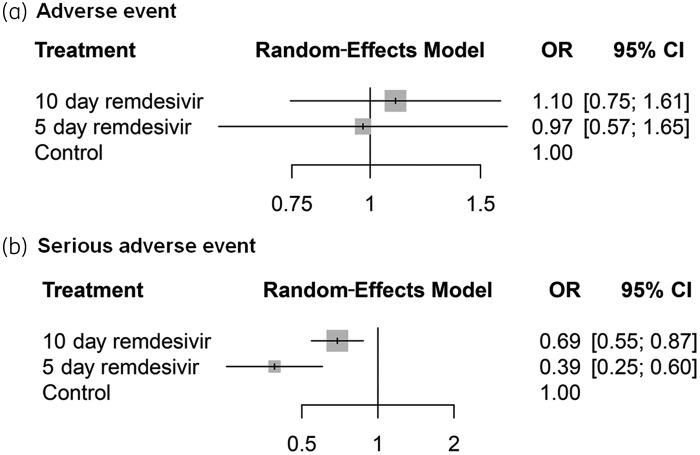

Risk of adverse events

No evidence of a relationship between remdesivir treatment and adverse events was detected [10 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 1.10 (95% CI 0.75–1.61); 5 day remdesivir versus control: OR = 0.97 (95% CI 0.57–1.65); Figure 4a]. However, a lower risk of serious adverse events was observed in both the 10 day remdesivir group [OR = 0.69 (95% CI 0.55–0.87)] and 5 day remdesivir group [OR = 0.39 (95% CI 0.25–0.60)] than in the control group (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Forest plots among treatment strategies for risk of adverse events (a) and serious adverse events (b).

Rank probability

The rank probability for each treatment, calculated using the P value, is presented in Table 2. The results revealed that the 5 day remdesivir treatment is superior to 10 day remdesivir treatment and placebo/standard of care.

Table 2.

Rank probability for treatment by P value

| Parameter | 5 day treatment | 10 day treatment | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical improvement | 0.991 | 0.458 | 0.051 |

| Mortality | 0.923 | 0.543 | 0.034 |

| Recovery | 0.995 | 0.499 | 0.006 |

| Discharge | 0.986 | 0.513 | 0.001 |

| Adverse event | 0.615 | 0.314 | 0.572 |

| Serious adverse event | 0.999 | 0.501 | 0.001 |

| Time to clinical improvement | 0.882 | 0.615 | 0.002 |

| Time to mortality | 0.754 | 0.590 | 0.156 |

| Time to recovery | 0.922 | 0.570 | 0.008 |

Heterogeneity and inconsistency

Heterogeneity across studies for all outcomes of interest was absent or low, except for adverse events with an I2 value of 66%. Furthermore, after the total heterogeneity was decomposed, no within-design heterogeneity was observed. Nonetheless, the Q-statistic for between-design inconsistency in adverse events was significant (Q = 8.06, P = 0.018) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Heterogeneity and inconsistency for each study outcome

| Total heterogeneity |

Within-design heterogeneity |

Between-design inconsistency |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | Q | P value | Q | P value | Q | P value | |

| Clinical improvement | 0 | 0.67 | 0.715 | 0.00 | NA | 0.67 | 0.715 |

| Mortality | 0 | 2.05 | 0.562 | 0.98 | 0.323 | 1.07 | 0.585 |

| Recovery | 0 | 0.73 | 0.694 | 0.00 | NA | 0.73 | 0.694 |

| Discharge | 0 | 1.52 | 0.677 | 1.24 | 0.266 | 0.28 | 0.868 |

| Adverse event | 66 | 8.93 | 0.030 | 0.86 | 0.353 | 8.06 | 0.018 |

| Severe adverse event | 0 | 1.31 | 0.727 | 0.06 | 0.801 | 1.24 | 0.537 |

| Time to clinical improvement | 20 | 3.73 | 0.293 | 0.06 | 0.804 | 3.66 | 0.160 |

| Time to mortality | 0 | 1.94 | 0.380 | 1.88 | 0.170 | 0.05 | 0.818 |

| Time to recovery | 33 | 3.00 | 0.223 | 0.00 | NA | 3.00 | 0.223 |

Results of net-splitting analyses revealed that there might be inconsistencies in comparisons between 10 day remdesivir treatment versus 5 day remdesivir treatment and between 10 day remdesivir treatment versus control for most outcomes of interest. The 95% CIs of indirect results were wider than those of direct results.

Quality assessment

Except for the risk of performance and detection biases owing to the open-label design in three studies,25,30,31 the other studies had a low risk of bias in all fields (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Summary of the risks of bias in each domain. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Discussion

This network meta-analysis of five RCTs24,25,30–32 involving 13 544 patients investigated the clinical efficacy and safety of remdesivir in the treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Most importantly, we observed a positive impact of remdesivir treatment on clinical outcomes of hospitalized COVID-19 patients, which was supported by the following evidence. First, patients receiving the 5 day remdesivir treatment showed greater clinical improvement than those in the control group. Second, patients receiving 5 day and 10 day remdesivir treatments were associated with a higher likelihood of being discharged than those in the control group. Third, a shorter time to clinical improvement and recovery was observed in patients receiving remdesivir than in the control group, irrespective of treatment duration. Finally, although patients receiving remdesivir treatment were associated with a lower risk of mortality than the control group, the difference was not statistically significant. Our findings were consistent with those of previous meta-analyses,20,23,33,34 which only included approximately 2000 patients. In contrast, our meta-analysis included the largest RCT by the WHO25 and the final reports of ACTT-1.30 Therefore, our findings are based on the analysis of more than 10 000 patients, providing more updated information and stronger evidence than previous studies. In summary, all these findings indicate that remdesivir could help improve clinical outcomes of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and demonstrate the promising role of remdesivir in treating patients with COVID-19.

This study compared the clinical efficacy of two regimens of remdesivir (5 day versus 10 day) employed for treating hospitalized patients with COVID-19 by performing a network meta-analysis. We observed that the 5 day regimen presented significantly greater clinical improvement than the 10 day regimen. Furthermore, the 5 day regimen of remdesivir was associated with a lower mortality rate than the 10 day regimen, but this difference was not statistically significant. The results of rank probability revealed that the 5 day regimen was superior to the 10 day regimen in terms of clinical improvement, mortality, recovery, discharge, time to clinical improvement, time to mortality and time to recovery (Table 2). These findings corroborate those of previous studies20,23,33 and suggest that remdesivir treatment for a short duration of 5 days may be sufficient to treat patients with moderate or severe COVID-19. However, the clinical efficacy of the 5 day remdesivir regimen was not assessed in critical COVID-19 patients who received mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the included RCTs.30,31 Therefore, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines only suggest using remdesivir in non-ventilated patients with severe COVID-19, but recommend against initiating remdesivir in critical COVID-19 patients outside clinical trials.35

Finally, this study assessed the safety of remdesivir for treating patients with COVID-19. Although a previous study has reported severe common adverse events, including an increase in hepatic enzymes (32.1%), renal injury (14.4%), increased creatinine levels (11.2%) and respiratory failure (6.4%),36 this meta-analysis did not detect an increased risk of adverse events following remdesivir treatment when compared with the control. Furthermore, a lower risk of serious adverse events was observed in both the 5 day and 10 day remdesivir groups than in the control group. Therefore, our findings suggest that remdesivir could be a safe antiviral agent for treating patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

This network meta-analysis had several strengths. This study included the largest number of patients and recently concluded studies when compared with previous meta-analyses.23,33,37 All findings were based on the analysis of RCTs and heterogeneity was low or absent across studies for all outcomes of interest, except for adverse events. However, this study also has a major limitation. The inclusion criteria varied among the included five RCTs;24,25,30–32 therefore, the disease severity of patients with COVID-19 could differ between studies, which would be associated with the heterogeneity of study populations. Fortunately, several clinical trials that have yet to present results are still ongoing (Table S2). After obtaining additional data in the near future, we plan to perform subgroup analysis according to the severity of COVID-19.

In conclusion, remdesivir can help improve clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and a 5 day regimen, instead of a 10 day regimen, may be sufficient for treatment. Moreover, remdesivir is as tolerable as other comparators or the placebo.

Funding

This study was supported by internal funding.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

Tables S1 and S2 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. WHO. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update and Weekly Operational Update. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/.

- 2. Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020; 55: 105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ko WC, Rolain JM, Lee NY et al. Arguments in favour of remdesivir for treating SARS-CoV-2 infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020; 55: 105933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siemieniuk RA, Bartoszko JJ, Ge L et al. Drug treatments for COVID-19: living systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2020; 370: m2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 929–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jean SS, Lee PI, Hsueh PR. Treatment options for COVID-19: the reality and challenges. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2020; 53: 436–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lai CC, Wang JH, Ko WC et al. COVID-19 in long-term care facilities: an upcoming threat that cannot be ignored. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2020; 53: 444–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang CJ, Chen TC, Chen YH. The preventive strategies of community hospital in the battle of fighting pandemic COVID-19 in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2020; 53: 381–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yen MY, Schwartz J, Chen SY et al. Interrupting COVID-19 transmission by implementing enhanced traffic control bundling: implications for global prevention and control efforts. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2020; 53: 377–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yen MY, Schwartz J, King CC et al. Recommendations for protecting against and mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic in long-term care facilities. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2020; 53: 447–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Antinori S, Cossu MV, Ridolfo AL et al. Compassionate remdesivir treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia in intensive care unit (ICU) and non-ICU patients: clinical outcome and differences in post-treatment hospitalisation status. Pharmacol Res 2020; 158: 104899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dubert M, Visseaux B, Isernia V et al. Case report study of the first five COVID-19 patients treated with remdesivir in France. Int J Infect Dis 2020; 98: 290–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D et al. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 2327–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee S, Santarelli A, Caine K et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of severe COVID-19: a community hospital’s experience. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2020; 120: 926–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rhodes NJ, Dairem A, Moore W et al. Multicenter point-prevalence evaluation of the utilization and safety of drug therapies for COVID-19. medRxiv 2020; doi:10.1101/2020.06.03.20121558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tempestilli M, Caputi P, Avataneo V et al. Pharmacokinetics of remdesivir and GS-441524 in two critically ill patients who recovered from COVID-19. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020; 75: 2977–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kalligeros M, Tashima KT, Mylona EK et al. Remdesivir use compared with supportive care in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19: a single-center experience. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7: ofaa319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brouqui P, Giraud-Gatineau A, Raoult D. Remdesivir investigational trials in COVID-19: a critical reappraisal. New Microbes New Infect 2020; 100707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Elsawah HK, Elsokary MA, Abdallah MS et al. Efficacy and safety of remdesivir in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: systematic review and meta-analysis including network meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol 2020; doi: 10.1002/rmv.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jiang Y, Chen D, Cai D et al. Effectiveness of remdesivir for the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 persons: a network meta-analysis. J Med Virol 2021; 93: 1171–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kow CS, Aldeyab M, Hasan SS. Effect of remdesivir on mortality in patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials. J Med Virol 2021; 93: 1860–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Misra S, Nath M, Hadda V et al. Efficacy of various treatment modalities for nCOV-2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest 2020; 50: e13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yokoyama Y, Briasoulis A, Takagi H et al. Effect of remdesivir on patients with COVID-19: a network meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Virus Res 2020; 288: 198137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19—final report. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1813–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pan H, Peto R, Karim QA et al. Repurposed antiviral drugs for COVID-19–interim WHO SOLIDARITY trial results. medRxiv 2020; doi:2020.10.15.20209817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015; 350: g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Krahn U, Binder H, König J. A graphical tool for locating inconsistency in network meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013; 13: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM et al. Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med 2010; 29: 932–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rücker G, Schwarzer G. Ranking treatments in frequentist network meta-analysis works without resampling methods. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015; 15: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goldman JD, Lye DCB, Hui DS et al. Remdesivir for 5 or 10 days in patients with severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1827–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spinner CD, Gottlieb RL, Criner GJ et al. Effect of remdesivir vs standard care on clinical status at 11 days in patients with moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 324: 1048–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2020; 395: 1569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilt TJ, Kaka AS, MacDonald R et al. Remdesivir for adults with COVID-19: a living systematic review for an American College of Physicians Practice Points. Ann Intern Med 2020; doi:10.7326/M20-5752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reddy Vegivinti CT, Pederson JM, Saravu K et al. Remdesivir therapy in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2021; 62: 43–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alhazzani W, Evans L, Alshamsi F et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines on the management of adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the ICU: first update. Crit Care Med 2021; 49: e219–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Charan J, Kaur RJ, Bhardwaj P et al. Rapid review of suspected adverse drug events due to remdesivir in the WHO database; findings and implications. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2021; 14: 95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gebrie D, Getnet D, Manyazewal T. Efficacy of remdesivir in patients with COVID-19: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e039159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.