Abstract

Horseshoe kidney (HSK) is a rare congenital malformation of the kidneys and is commonly associated with other anomalies of the renovascular and ureteropelvic systems. These anomalies present a surgical challenge, especially for surgeries involving the retroperitoneum. We present the case of a 56-year-old male patient with biopsy-proven rectal cancer who had completed neoadjuvant chemoradiation and was planned for curative resection. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed the presence of an HSK. Reconstructed three-dimensional (3D) images of the renal vasculature revealed the presence of an accessory renal artery originating directly from the aorta and supplying the isthmus of the HSK without any other venous or ureteral anomalies. Laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection with total mesorectal excision was done without any untoward complications. The presence of HSK per se is not a contraindication for laparoscopic operations involving the retroperitoneum. Pre-operative 3D CECT helps to identify the presence of anatomical variations and guides surgical resection.

Keywords: Colonic neoplasm, colorectal surgery, fused kidney, laparoscopic surgery

INTRODUCTION

Horseshoe kidney (HSK) is a rare congenital malformation seen in 0.25%–0.3% of the general population.[1] Anomalies of renal vessels, ureter, gonadal vessels and lumbar splanchnic nerves have been described in patients with HSK, which can increase the chances of iatrogenic complications in operations involving the retroperitoneum.[2]

We report a rare association of HSK in a patient with rectal cancer who underwent laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection with total mesorectal excision (TME) and describe the techniques we had employed to prevent an intraoperative mishap. Laparoscopic management of rectal cancer in the presence of HSK is scarcely described, except for few reports in Japanese literature.[3,4]

CASE REPORT

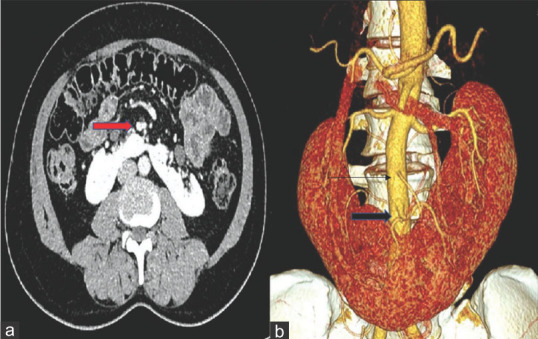

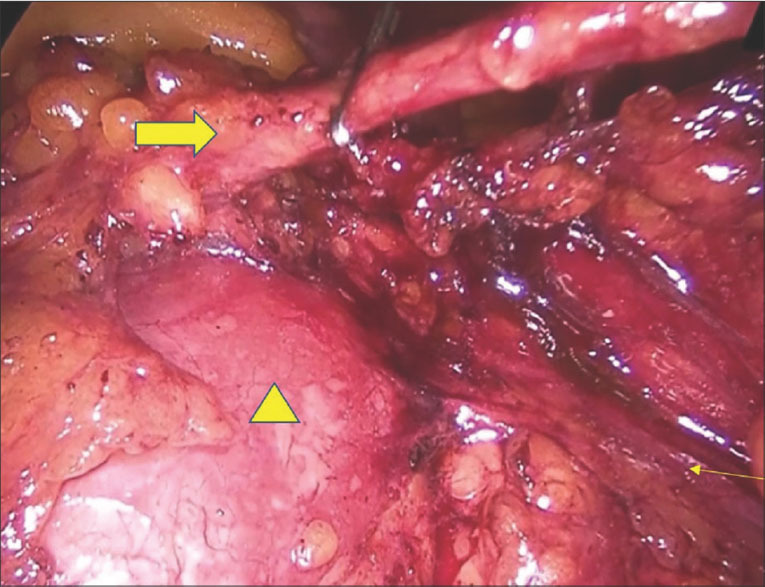

A 56-year-old male patient with complaints of melaena and altered bowel habits was diagnosed to have biopsy-proven carcinoma rectum. Clinical and radiological investigations revealed locally advanced carcinoma of the lower rectum with mesorectal infiltration, loss of fat plane with the prostate and enlarged perirectal nodes without distant metastasis. After a multidisciplinary tumour board discussion, the patient underwent neoadjuvant long-course radiation with concurrent capecitabine. Tumour restaging was performed using contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis, which revealed partial response of the tumour to chemoradiation therapy. Imaging also revealed the presence of an incidental HSK [Figure 1a]. Reconstructed three-dimensional (3D) images of the renal vascular system revealed an accessory renal artery arising directly from the aorta just below the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) and bifurcating before supplying the isthmus [Figure 1b]. No other anatomical abnormalities were visualised. Laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection with TME was done after ligation of the IMA just distal to the origin of the left colic artery using the conventional five-port technique. Isthmus of HSK was noted immediately below the origin of the IMA from the aorta [Figure 2]. The ipsilateral ureter was identified more medially than usual. The left ureter and gonadal vessels were both identified ventral to the HSK and preserved. The hypogastric plexus was dorsal to the HSK and preserved. The accessory renal artery was not visualised intraoperatively as the dissection was limited distal to the origin of the left colic artery. The patient was discharged on post-operative day 5. Final histopathology revealed the presence of a residual tumour without nodal involvement, for which the patient received 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy. At 18 months of follow-up, he is alive and disease free.

Figure 1.

(a) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showing horseshoe kidney with the isthmus in the midline and its relation to the accessory renal artery (bold red arrow). (b) reconstructed three-dimensional contrast-enhanced computed tomography image showing the accessory renal artery (bold black arrow) arising from the abdominal aorta just inferior to the inferior mesenteric artery (single arrow) and supplying the isthmus of the horseshoe kidney

Figure 2.

Intraoperative photograph showing the inferior mesenteric artery being clipped (bold arrow) just inferior to the isthmus of the horseshoe kidney (triangle) and the ureter is seen running posterior to the inferior mesenteric artery (single thin arrow)

DISCUSSION

Approximately 63% of HSK patients have more than three renal arteries, while single or double renal arteries are seen in 37% of patients. The isthmus may receive a separate branch from the abdominal aorta (most common type), with additional or separate arteries arising from the common iliac artery and IMA also. Renal vein anomalies are also relatively high in HSK (23%). Inferior vena cava variations are ten times more common in patients with HSK. Ureters may descend anterior to the isthmus. Ureteral duplications, retrocaval ureters and variation in the number of ureters have been described.[2] Operating on a patient with HSK is fraught with danger due to these anomalous vascular and abnormal ureteral pathways.

Pre-operative planning-multidetector CT of the abdomen has been described as the imaging of choice in patients with renal fusion abnormalities because it provides high spatial and temporal resolution across multiple planes and provides accurate delineation of vital structures. The use of 3D CT angiography with reconstructed images of the vessels provides an in-depth view of the intraoperative anatomy and makes dissection safer.[5]

The presence of anatomic variations has been considered a relative contraindication for laparoscopic surgery. On the contrary, laparoscopic surgery provides a magnified view of the operative field and should be considered the approach of choice in patients with anatomical variations in whom pre-operative mapping of anomalies has been done.

In our patient, pre-operative identification of the location of the accessory renal artery helped us to decide the level of dissection. The IMA was dissected and ligated just distal to the origin of the left colic artery, as indicated in cases with lower rectal cancer. Avoiding unnecessary high ligation of the IMA close to the aorta prevents inadvertent vascular injury to the isthmic supply.

Medial approach (vessel- first approach) was employed in our patient rather than lateral approach. Besides the theoretical possibility of reduced tumour handling and dissemination, medial approach in such complicated cases also offers the advantage of tackling the most important step of the operation early. Initial ligation also gives the added advantage of deciding the level of bowel transection, which is very vital in patients with low rectal lesions where low anterior resection is performed. Improved lymph nodal harvest and better circumferential margin rates have been noted in medial-to-lateral approach compared to vice versa and is our preferred technique in laparoscopic rectal operations.[6] However, unlikely in this era of advanced imaging techniques, it is of utmost importance that any chances of inoperability due to the primary tumour are ruled out before vessel ligation.

Basic surgical principles such as dissection of all anatomical landmarks before vascular ligation and emphasis on proper dissection planes and maintaining strict haemostasis for optimal visualisation also prevent iatrogenic injuries. The most cardinal principle, however, is to recognise the presence of anomalous structures intraoperatively and avoiding unnecessary ligation of any structure, unless indicated.

To conclude, laparoscopic surgery can be safely performed in patients with HSK with proper pre-operative planning and meticulous surgical technique. The use of ancillary technology such as 3D CT angiography with reconstructed images can help minimise the risk of iatrogenic injuries and should be strongly considered pre-operatively.

Patient consent

Consent has been taken from the patient and family for publishing these images in a medical journal.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his name and initial will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Natsis K, Piagkou M, Skotsimara A, Protogerou V, Tsitouridis I, Skandalakis P. Horseshoe kidney: A review of anatomy and pathology. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014;36:517–26. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taghavi K, Kirkpatrick J, Mirjalili SA. The horseshoe kidney: Surgical anatomy and embryology. J Pediatr Urol. 2016;12:275–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubo N, Furusawa N, Imai S, Terada M. Case of laparoscopic high anterior resection of rectosigmoid colon cancer associated with a horseshoe kidney using preoperative 3D-CT angiography. Surg Case Rep. 2018;4:66. doi: 10.1186/s40792-018-0472-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maeda Y, Shinohara T, Nagatsu A, Futakawa N, Hamada T. Laparoscopic resection aided by preoperative 3-D CT angiography for rectosigmoid colon cancer associated with a horseshoe kidney: A case report. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2014;7:317–9. doi: 10.1111/ases.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiappacasse G, Aguirre J, Soffia P, Silva CS, Zilleruelo N. CT findings of the main pathological conditions associated with horseshoe kidneys. Br J Radiol. 2015;88:20140456. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussain A, Mahmood F, Torrance AW, Tsiamis A. Impact of medial-to-lateral vs.lateral-to-medial approach on short-term and cancer-related outcomes in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2018;26:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]