Abstract

Background:

Although surgical resection is the main treatment for rectal cancer, the optimal surgical protocol for elderly patients with rectal cancer remains controversial. This study evaluated the feasibility of robot-assisted surgery in elderly patients with rectal cancer.

Patients and Methods:

This retrospective study enrolled 156 patients aged 28–93 years diagnosed with Stage I–III rectal cancer, who underwent robot-assisted surgery between May 2013 and December 2018 at a single institution.

Results:

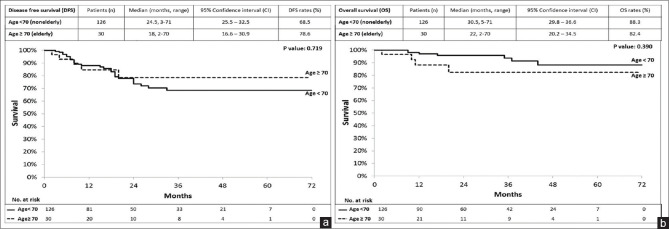

In total, 156 patients with rectal cancer, including 126 non-elderly (aged < 70 years) and 30 elderly (aged ≥70 years) patients, who underwent robot-assisted surgery were recruited. Between the patient groups, the post-operative length of hospital stay did not differ statistically significantly (P = 0.084). The incidence of overall post-operative complications was statistically significantly lower in the elderly group (P = 0.002). The disease-free and overall survival did not differ statistically significantly between the two groups (P = 0.719 and 0.390, respectively).

Conclusions:

Robot-assisted surgery for rectal cancer was well tolerated by elderly patients, with similar results to the non-elderly patients. Oncological outcomes and survival did not depend on patient age, suggesting that robot-assisted surgery is a feasible surgical modality for treating operable rectal cancer and leads to age-independent post-operative outcomes in elderly patients.

Keywords: Elderly patients, rectal cancer, robot-assisted surgery

INTRODUCTION

Rectal cancer, along with colon cancer, is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer globally. Moreover, it is the second and third leading causes of cancer death worldwide[1] and in Taiwan,[2] respectively. Surgery remains the mainstay of treating for patients with rectal cancer.[3] Rectal cancer surgery can be challenging; it involves radical tumour excision while preserving the anus. Standardised total mesorectal excision (TME) was established in 1982, and precise dissection along the mesorectal fascia became a standard procedure for middle and lower rectal cancer.[4] Tumour resection combined with maximum locoregional clearance and en bloc resection of the primary tumour, along with its blood supply and lymphatic drainage, significantly increases disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS).[5,6]

The laparoscopic TME (laTME) approach has become popular over the past 25 years as an appropriate alternative approach to traditional open anterior rectal resection with comparable oncological outcomes.[7] However, several studies have stated high conversion rates of up to 20%–30% as a limitation of laTME, which is closely related to higher morbidity rates and poor oncological outcome.[7,8,9,10,11,12] Robot-assisted surgery for rectal cancer was introduced since 2006 which demonstrated perioperative and oncological outcomes similar to laTME.[13,14,15] The advantages of robot-assisted surgery include a stable camera platform, three-dimensional imaging, tremor elimination, motion scaling, ambidextrous capability, instruments with multiple degrees of freedom and a third arm for fixed retraction.[7]

Robot-assisted surgery is particularly advantageous

It allows precise dissection in surgically problematic anatomical conditions, such as narrow pelvis and obese patients, making rectal resections for low-lying and bulky tumours possible.[16] Robot-assisted surgery also elicits small wounds, less blood loss, early recovery and high anal preservation rate. When recommending this surgery to elderly patients with rectal cancer, factors such as their shorter life expectancy, increased incidence of comorbidities and lower daily activity level compared with younger patients should be considered comprehensively.[17] In this study, we evaluated the feasibility of robot-assisted surgery in elderly patients with rectal cancer by comparing the clinical outcomes of non-elderly (aged <70 years) and elderly (aged ≥70 years) patients with rectal cancer, who underwent robot-assisted surgery at a single institute.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This retrospective study included 156 patients with Stage I–III rectal cancer, aged 28–93 years, who underwent robot-assisted surgery at our institution between May 2013 and April 2018. Patients recruited were then divided into two groups according to age: (1) non-elderly (age <70 years, n = 126) and (2) elderly (age ≥70 years, n = 30) groups. The median age of 70 years was selected considering the average life expectancy of the global population in 2016.[18]

This study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital (KMUHIRB-E (I)-20180290). All patients underwent routine pre-operative examination, including colonoscopy, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging for pre-operative staging. Rectal cancer was categorised according to its distance from the anal verge: upper (11–15 cm), middle (6–10 cm) and lower (≤5 cm). Patients with T3, T4 or N+ rectal cancer underwent pre-operative concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT). A fluoropyrimidine-based regimen was prescribed to patients with T3N0 or T2–3N+ rectal cancer, and a 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin regimen was prescribed for patients with T4 rectal cancer, as described previously.[19,20] Long-course radiotherapy (RT; total 5000 cGy in 25 fractions) was concurrently administered. Robot-assisted surgery was scheduled approximately 10–12 weeks after RT completion.[20]

All patients underwent surgery involving the left upper quadrant, the left lower quadrant and the pelvic cavity. The high dissection and low ligation method, which involves D3 lymph node dissection and low-tie ligation of the inferior mesentery artery with preservation of the left colic artery, was used in all patients.[21] The descending colon and sigmoid colon were first mobilised and then pelvic dissection was performed. A single-docking technique without moving the robotic surgical cart and repositioning robotic arms was implemented in all patients, as described previously.[21,22]

The demographic characteristics and clinicopathological features were recorded. Data, including age; sex; histological type; tumour, node and metastasis (TNM classification); perineural invasion; vascular invasion; tumour location (distance from anal verge); time interval between the completion of pre-operative RT and robotic surgery and tumour regression grade, were collected for all patients. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification prior to surgery, tumour location, type of surgical procedure, pathological TNM staging and post-operative complications were also recorded. The TNM staging was defined according to the criteria of the American Joint Commission on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control.[23,24]

Perioperative outcomes, including surgical procedures, docking time, console time, operation time and estimated blood loss, were also evaluated. Docking time was the time required to position the robot and secure its arms to the corresponding port sites. Console time was the total time during which the surgeon performed any procedure by using the robotic system. Operation time was the time between the initial skin incision and wound-closure completion.

Patients had regular post-operative follow-ups every 3 months during the first 2 years and then every 6 months during the subsequent 3 years. History was recorded, and physical examination was performed during the follow-ups, including the compilation of their clinical outcomes and survival statuses. Post-operative serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels were measured every 2–3 months. Colonoscopy was scheduled for approximately 1 year after surgery. All patients were followed up until their death, the last recorded follow-up, or 31 May 2019. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) follow-up duration for all patients was 26 (2–68) months. OS was defined as the time from the date of primary treatment to the date of death from any cause or the date of last follow-up. DFS was defined as the time from the date of primary treatment to the date of diagnosis of recurrence or metastatic disease or the date of final follow-up.

Statistical analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel 2010 and MedCalc (version 18.6; MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium; http://www.medcalc.org; 2018). Continuous variables were expressed as medians and IQRs and then analysed using one-way analysis of variance. Categorical variables were analysed using Fisher's exact or the Chi-square test where appropriate. OS and DFS were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. P < 0.05 denoted statistical significance.

RESULTS

Patient demographics

The demographic characteristics of the 156 included patients with rectal cancer who underwent robotic-assisted surgery are summarised in Table 1. The non-elderly and elderly groups comprised 126 and 30 patients, respectively, with a median (IQR) age of 59 (28–69) and 75 (70–93) years, respectively, and a male-to-female ratio of 1.57 and 1.31, respectively (P = 0.655). The lower rectum (≤5 cm from the anal verge) was the most common tumour site in both groups; its incidence was statistically significantly higher in the elderly group (P = 0.001). Of the 126 non-elderly patients, ninety (71.4%) had undergone CCRT before robot-assisted surgery, whereas 22 (73.3%) of the 30 elderly patients had completed RT before surgery (P = 0.109). The median interval between RT completion and surgical intervention was 83 and 86 days in the non-elderly and elderly groups, respectively (P = 0.113). Tumour regression grades did not differ between non-elderly and elderly patients who completed CCRT (P = 0.759).

Table 1.

156 patient demographics

| Age <70 (n=126), n (%) | Age ≥70 (n=30), n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 59 (28-69) | 75 (70-93) | <0.001 |

| Mean age (range) | 56.7 (28-69) | 77.7 (70-93) | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 49 (38.9) | 13 (43.3) | 0.655 |

| Male | 77 (61.1) | 17 (56.7) | |

| Tumour distance from anal verge (cm) | |||

| ≦5 (lower) | 75 (59.5) | 23 (76.7) | 0.001 |

| 6-10 (middle) | 48 (38.1) | 3 (10.0) | |

| 11-15 (upper) | 3 (2.4) | 4 (13.3) | |

| Distance from anal verge (cm), median (range) | 4 (0.5-15) | 4 (1-15) | 0.174 |

| Patients with a completion of CCRT | 90 (71.4) | 22 (73.3) | 0.109 |

| Interval between completion of RT and surgical intervention (number of patients), median (days) | 83 | 86 | 0.113 |

| Tumour regression grade (patients with completion of CCRT) | |||

| 0 | 29 (23.0) | 9 (30.0) | 0.759 |

| 1 | 35 (27.8) | 9 (30.0) | |

| 2 | 19 (15.1) | 3 (10.0) | |

| 3 | 7 (5.6) | 1 (3.3) | |

| ASA classification | |||

| II | 96 (76.2) | 7 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| III | 30 (23.8) | 22 (73.3) | |

| IV | 0 | 1 (3.33) | |

| Procedure | |||

| LAR | 75 (59.5) | 13 (43.3) | 0.275 |

| ISR | 48 (38.1) | 16 (53.4) | |

| APR | 3 (2.4) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Protective diverting colostomy | |||

| Yes | 16 (12.7) | 9 (30.0) | 0.041 |

| No | 110 (87.3) | 21 (70.0) | |

| Docking time (min), median (range) | 4 (3-22) | 5 (3-10) | 0.264 |

| Console time (min), median (range) | 180 (120-527) | 195 (140-368) | 0.278 |

| Operation time (min), median (range) | 280 (200-795) | 320 (230-595) | 0.187 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL), median | 100 (15-1050) | 50 (15-350) | 0.184 |

| Post-operative LOH (days), median (range) | 6 (5-30) | 7 (5-46) | 0.084 |

RT: Radiotherapy, CCRT: Concurrent chemo RT, ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists, LAR: Low anterior resection, ISR: Intersphenteric resection, APR: Abdominoperineal resection, LOH: Length of hospital stay

For all patients, the entire rectum and mesorectum (after the sigmoid or descending colon, mesocolon) were completely mobilised, followed by low anterior resection (LAR) with the double-stapled technique, intersphincteric resection (ISR) with coloanal anastomosis and loop colostomy, or abdominoperineal resection (APR), all performed as described previously.[21,22,25] Tumours located in the upper and middle rectum were excised through LAR using the double-stapled technique. Intraoperative dye test was routinely performed to examine potential anastomotic leakage after LAR by using the double-stapled technique.[26] ISR with coloanal anastomosis and loop colostomy was implicated for tumours in the low rectum, and natural orifice specimen extraction was performed transanally by using the Lone Star Retractor System (Lone Star Medical Products Inc., Houston, TX, USA). The hand-sewn method was used for coloanal anastomosis, and protective loop colostomy of the transverse colon was performed. Bleeding in the abdominal cavity was detected through laparoscopic assistance, and a drain tube was placed in the pelvic cavity.[27]

A significant number of patients in the elderly group (73.3%) were categorised as ASA Grade III than those in the non-elderly group, in which only 30 of the 126 (23.8%) patients were of ASA Grade III [P < 0.001, Table 1]. Surgical procedures used were LAR with the double-stapled technique, ISR with coloanal anastomosis and loop colostomy, or APR. The most frequently performed procedures were LAR in the non-elderly (59.5%) group and ISR in the elderly (53.4%) group. Protective diverting colostomy was performed on 9 of the 30 (30%) elderly patients and 16 of the 126 (12.7%) non-elderly patients [P = 0.041; Table 1].

No significant differences were observed for robotic surgical procedures, docking time, console time, operation time and estimated blood loss between the two groups [Table 1]. Notably, differences in the median post-operative length of hospital stay between the non-elderly and elderly groups were statistically insignificant (6 days vs. 7 days, P = 0.084).

Clinicopathological characteristics and oncological outcomes

Clinicopathological characteristics and oncological outcomes of all 156 patients are provided in Table 2. Pre-operative clinical staging indicated that most patients in both groups had T3 rectal cancers. The non-elderly and elderly groups had 81 (64.3%) and 23 (76.7%) patients with T3 rectal cancer, respectively; however, no statistically significant differences were observed for pre-operative tumour depth (P = 0.606) and staging (P = 0.197) between these two groups. The median number of lymph nodes harvested from both the non-elderly and elderly groups was 9 (P = 0.429). The distal resection margin (DRM) and circumferential resection margin (CRM) did not statistically significantly differ between the two study groups (P = 0.909 and P = 0.835, respectively). In the non-elderly group, DRM and CRM were positive in two patients (1.6%) each. DRM was positive in one elderly patient (3.3%), but CRM was negative for all elderly patients. R0 resection for primary rectal cancer was performed in 124 non-elderly (98.4%) and 29 elderly (96.7%) patients (P = 0.909). The outcome and survival data collection of all 156 patients was completed in May 2019. No statistically significant difference was observed in DFS [P = 0.719; Figure 1a] or OS [P = 0.390, Figure 1b] between the two groups. The median (IQR) disease-free duration was 24.5 (3–71) and 18 (2–70) months in the non-elderly and elderly groups, respectively, with a DFS of 68.5% and 78.6%, respectively [P = 0.719, Figure 1a]. The OS rate in the non-elderly and elderly groups was 88.3% and 82.4%, respectively [P = 0.390, Figure 1b].

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic characteristics and oncological outcomes between the non-elderly and elderly groups

| Age <70 (n=126), n (%) | Age ≥70 (n=30), n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative clinical staging | |||

| Tumour depth | |||

| T1 | 4 (3.2) | 1 (3.3) | 0.606 |

| T2 | 26 (20.6) | 4 (13.3) | |

| T3 | 81 (64.3) | 23 (76.7) | |

| T4 | 15 (11.9) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| N0 | 55 (43.7) | 13 (43.3) | 0.047 |

| N1 | 45 (35.7) | 16 (53.4) | |

| N2 | 26 (20.6) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Stage | |||

| I | 25 (19.8) | 5 (16.7) | 0.197 |

| II | 30 (23.8) | 12 (40.0) | |

| III | 71 (56.4) | 13 (43.3) | |

| Post-operative pathological outcomes | |||

| Tumour size (cm) | 0.625 | ||

| s<5 | 116 (92.1) | 29 (96.7) | |

| ≥5 | 10 (7.9) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Tumour size (cm), mean±SD (range) | 2.10±1.8 (0-12.5) | 2.30±1.7 (0-7.5) | 0.147 |

| Tumour depth | |||

| T0 | 36 (28.6) | 9 (30.0) | 0.982 |

| T1 | 24 (19.0) | 5 (16.7) | |

| T2 | 29 (23.0) | 7 (23.3) | |

| T3 | 36 (28.6) | 9 (30.0) | |

| T4 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| N0 | 97 (77.0) | 27 (90.0) | 0.230 |

| N1 | 23 (18.3) | 3 (10.0) | |

| N2 | 6 (4.7) | 0 | |

| Harvested lymph node, median (range) | 9 (0-31) | 9 (2-22) | 0.429 |

| Harvested apical node, median (range) | 2 (0-10) | 2 (0-5) | 0.212 |

| Distance of proximal resection margin (cm), median (range) | 5.8 (0.9-58) | 6.0 (1.5-12.5) | 0.302 |

| Distance of DRM (cm), median (range) | 1.8 (0.1-8.1) | 1.75 (0.1-3.5) | 0.142 |

| Distance of CRM (cm), median (range) | 1.35 (0.1-14) | 1.2 (0.1-9.8) | 0.440 |

| DRM | |||

| Negative | 124 (98.4) | 29 (96.7) | 0.909 |

| Positive | 2 (1.6) | 1 (3.3) | |

| CRM | |||

| Negative | 124 (98.4) | 30 (100) | 0.835 |

| Positive | 2 (1.6) | 0 | |

| Resection degree of primary tumour | |||

| R0 | 124 (98.4) | 29 (96.7) | 0.909 |

| R1 | 2 (1.6) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Local recurrence | |||

| Negative | 114 (90.5) | 30 (100) | 0.168 |

| Positive | 12 (9.5) | 0 | |

| Distant metastasis | |||

| Negative | 104 (82.5) | 28 (93.3) | 0.234 |

| Positive | 22 (17.5) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Survival | |||

| Yes | 106 (84.1) | 23 (76.7) | 0.326 |

| No | 7 (5.6) | 4 (13.3) | |

| Lost follow-up | 13 (10.3) | 3 (10) |

T0–T4: Tumour depth defined according to the criteria of the AJCC/International Union against Cancer UICC, N0–N2: Presence of any lymph node metastases defined according to the criteria of the AJCC/UICC, DRM: Distal resection margin, CRM: Circumferential resection margin, AJCC: American Joint Commission on Cancer, UICC: Union for International Cancer Control, SD: Standard deviation

Figure 1.

(a) Disease-free survival of 156 patients with rectal cancer who underwent robot-assisted surgery divided into non-elderly (age <70 years) and elderly (age ≥70 years) (P = 0.719). (b) Overall survival of 156 patients with rectal cancer who underwent robot-assisted surgery divided into non-elderly (age <70 years) and elderly (age ≥70 years) (P = 0.390)

Surgical outcomes and post-operative complications

Local recurrence occurred in 12 (9.5%) non-elderly patients but not in any elderly patients [P = 0.168, Table 2]. No statistically significant difference was observed between the non-elderly and elderly groups for distant metastasis [P = 0.234, Table 2] . Survival statuses for both the non-elderly and elderly groups did not differ statistically significantly [P = 0.326, Table 2] . Of the 126 non-elderly patients, 106 (84.1%) are alive, 7 (5.6%) have died and 13 patients (10.3%) have been lost to follow-up. Of the 30 elderly patients, 23 (76.7%) are alive, 4 (13.3%) have died and 3 (10%) have been lost to follow-up.

The post-operative complications are listed in Table 3. The incidence of overall post-operative complications was statistically significantly lower in the elderly group than that in the non-elderly group (P = 0.002). There were 26 episodes (20.6%) of post-operative complications in the non-elderly group, whereas in the elderly group, there were 5 episodes (16.7%) of post-operative complications. The most common in-hospital complications were anastomotic leakage (5.6%) and anal stenosis (4.8%) in the non-elderly group and pulmonary complication (10%) in the elderly group. Loop colostomy was subsequently performed on patients with anastomotic leakage in both groups (seven non-elderly patients and one elderly patient). Patients who developed stenosis of coloanal anastomosis underwent dilation using a colonoscopy (six non-elderly patients and one elderly patient). According to the Clavien–Dindo classification, all post-operative ileus, urinary tract and pulmonary complications were of Grade I, and the patients recovered after conservative treatment. Post-operative 30-day mortality did not occur in either study group in our study.

Table 3.

Post-operative complications between the non-elderly and elderly groups

| Age <70 (n=126), n (%) | Age ≥70 (n=30), n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall complications | 26 (20.6) | 5 (16.7) | |

| Ileus | 3 (2.4) | 0 | 0.002 |

| Anastomosis leakage | 7 (5.6) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Pulmonary complication | 2 (1.6) | 3 (10.0) | |

| Anal stenosis | 6 (4.8) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Intra-abdominal hematoma | 3 (2.4) | 0 | |

| Internal (mesorectum) bleeding | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Urethral injury during ISR | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Urinary retention | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 (0.8) | 0 |

ISR: Intersphincteric resection

DISCUSSION

Approximately 43,057 new cases of rectal cancer are diagnosed annually in the United States, which comprised nearly 30.7% of all colorectal cancer (CRC) new cases.[28] Rectal cancer accounts for the largest number of all CRC cases in developing countries or in low-risk areas, such as Asia.[29,30] Although tumour resection remains a standard of care for rectal cancer patients, CRC resection is performed less often on elderly patients than on non-elderly patients.[31] Elderly patients are also less likely to receive the recommended treatments.[32] This leads to slightly less favourable functional and oncological outcomes in older elderly patients with rectal cancer. Comorbidities, such as cardiovascular and respiratory problems, which may influence decision-making regarding surgical suitability, occur more commonly in elderly patients.[33] Thus, more comprehensive consideration is required for elderly patients when surgical decisions are made because the patients and their families might often prefer less aggressive treatments. Old age should not be a limiting factor for accepting rectal cancer treatment, including surgical resection, because curative resection can be well tolerated by patients aged >75 years.[34,35]

Robot-assisted surgery is an advancement of conventional minimally invasive surgery[36] and a promising tool for enhancing rectal resection. The high precision of robot-assisted surgery with enhanced optical magnification and fine instruments that are much smaller than the human wrist provide more flexibility than an ordinary human hand. The common drawbacks of minimally invasive rectal surgery, such as obesity and low-lying tumours, can be overcome through robotic assistance.[16] Laparoscopic surgery is safe for and well tolerated by both younger and elderly patients.[37] However, whether robot-assisted surgery is as feasible for elderly patients with rectal cancer as for non-elderly patients with rectal cancer has been discussed to a limited extent.

To our knowledge, no study has discussed the robot-assisted surgery specifically in terms of differences in surgical outcome between <70- and ≥70-year-old patients with rectal cancer. Nevertheless, in the current study, we observed no remarkable difference in the operative outcomes of the rectal cancer patients aged <70 and ≥ 70 years. Comparable to oncologic outcomes of open and laparoscopic approaches, robot-assisted surgery improved long-term survival to patients with mid- and low-rectal cancers.[38,39] The quality of TME, lymph node dissection and autonomic nerve system preservation in the pelvis were improved by the robot-assisted approach, thus reducing post-operative pelvic organ disorders.[40] Robot-assisted surgery is also associated with reduced complications concerning post-operative urination and sexual dysfunction. Our study observed one (1.0%) urethral injury during ISR and one (1.0%) urinary retention issue in the non-elderly group, but no such cases were noted in the elderly group.

Despite its effectiveness, rectal cancer surgery can lead to anal, urinary and reproductive function impairment; surgical complications; higher local tumour recurrence rate (5%–27%) and death.[41] The post-operative mortality and morbidity in elderly patients can considerably increase with increased age, advanced disease and post-operative medical and surgical complications.[42] It is noteworthy that the total complication rates of robot-assisted rectal surgery were significantly lower in the elderly group compared to the non-elderly group. Advanced disease status was similar in the non-elderly and elderly groups. In addition, pre-operative CCRT considerably improved the local recurrence rate in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer.[22] All patients in the elderly group were negative for local recurrence during the follow-up period after robot-assisted surgery, but 12 (9.5%) non-elderly patients developed local recurrence (P = 0.168), with an overall local recurrence rate of 7.7%.

Nitsche et al. indicated that compared with patients aged <75 years, those aged >75 years require a longer post-operative length of hospital stay after colorectal surgery (mean length of hospital stay, 24 ± 12 vs. 20 ± 13 days, P = 0.002) because they are monitored more often in the intensive care unit (77% vs. 62%, P < 0.001).[35] Notably, the median post-operative lengths of hospital stay did not differ between the non-elderly and elderly groups in our study. Previous research and a systematic review have revealed that among patients with CRC (aged ≥80 years), those with rectal cancer have a higher risk of post-operative 30-day mortality;[17,31,43] however, no post-operative 30-day mortality occurred in the current study.

In this study, survival and morbidity outcomes were promising, despite challenges, such as bulky tumours (10 non-elderly patients had a tumour of size >5 cm), low-lying rectal cancer (distance of 1.0 cm from the anal verge), more difficult operation conditions (48 non-elderly and 16 elderly patients had ISR) and a greater number of male patients (77 non-elderly and 17 elderly male patients). All patients had undergone robot-assisted surgery as planned, and none converted to open or laparoscopic surgery (conversion rate = 0%). An advanced local cancer stage and larger tumour size may account for higher conversion rates reported previously.[44,45,46,47]

CRM involvement is crucial when assessing surgery standards and is established as a prognostic factor for local recurrence and survival.[48,49,50,51] The overall rate of CRM involvement in this study was 1.3% (1.6% and 0% in the non-elderly and elderly groups, respectively), comparable with that reported in other studie [0%–6.8%, Table 4].[14,52,53,54,55] Moreover, the median distance of DRM in all 156 patients was 1.8 cm (1.8 and 1.75 cm in the nonelderly and elderly groups, respectively), also comparable with that reported in earlier studies [Table 4]. The overall anastomosis leakage rate in our study was 5.1% (8 out of 156 patients), relatively low compared with that in most other studies.[14,52,53,54,55]

Table 4.

Comparison of clinical and perioperative outcomes of robot-assisted surgery

| Study | Country (years) | Sample size | Lower rectum (%) | Pre-operative CCRT (%) | Conversion rate (%) | Estimated blood loss (mL) (median) | Overall complications (%) | Anastomotic leakage (%) | Rate of sphincter preservation (%) | DRM (cm) (median) | Positive CRM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present study | Taiwan (2019) | 156 (Stage 0-III) | 62.8 | 71.8 | 0 | 75 (15-1050) | 19.8 | 5.1 | 97.4 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| 126 (age<70) | 59.5 | 71.4 | 0 | 100 (15-1050) | 20.6 | 5.6 | 97.6 | 1.8 | 1.6 | ||

| 30 (age≥70) | 76.7 | 73.3 | 0 | 50 (15-350) | 16.7 | 3.3 | 96.7 | 1.75 | 0 | ||

| Park et al.[52] | Korea (2015) | 133 (yp Stage I-III) | 24.8 | 11.3 | 0 | 77.6 (0-700) | 19.7 | 4.5 | 100 | 2.75 | 6.8 |

| Ghezzi et al.[53] | Brazil/Italy (2014) | 65 (yp Stage 0-III) | 100 | 72.3 | 1.5 | 0 (0-175) | 41.5 | 7.1 | 86.2 | 2.7 | 0 |

| Cho et al.[54] | Korea (2012) | 278 (yp Stage 0-III) | 24.8 | 32.7 | 0.4 | 179.0 | 25.9 | 10.4 | 100 | 2.0 | 5 |

| Park et al.[55] | Korea (2011) | 52 (yp Stage 0-III) | 60.4 (<7 cm) | 23.1 | 0 | NA | 19.2 | 9.6 | 100 | 2.8 | 1.9 |

| Baek et al.[14] | Korea (2011) | 41 (yp Stage 0-III) | 36.6 (<7 cm) | 80.5 | 7.3 | 200 (20-2000) | 22.0 | 7.3 | 85.4 | 3.6 | 2.4 |

CCRT: Concurrent chemoradiotherapy, CRM: Circumferential resection margin, DRM: Distal resection margin, NA: Not applicable

However, the current study has some limitations. First, this was a single-institutional, retrospective study with a limited cohort size of 156 patients classified into a non-elderly group (<70 years of age, n = 126) and an elderly group (≥70 years of age, n = 30). Second, the effects of chemotherapy and RT were not analysed because the objective was the surgical outcome of robot-assisted surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

Robot-assisted surgery is safe and feasible for all patients with rectal cancer, regardless of age. Robot-assisted surgery for rectal patients is generally well tolerated; even elderly patients demonstrated post-operative clinical outcomes and complications comparable to those of non-elderly patients. Thus, age should not be considered a limiting factor for CRC surgery, including robot-assisted surgery. Rather using age alone as the determinant for choosing a less aggressive therapy, comprehensive assessment for robot-assisted surgery is recommended for elderly patients with rectal cancer.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by grants through funding from the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST108-2321-B-037-001, MOST107-2321-B-037-003, MOST107-2314-B-037-116, MOST107-2314-B-037-022-MY2, MOST107-2314-B-037-023-MY2) and the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW107-TDU-B-212-123006, MOHW107-TDU-B-212-114026B, MOHW108-TDU-B-212-133006, MOHW108-TDU-B-212-124026) funded by Health and welfare surcharge of tobacco products, and the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH108-8R34, KMUH108-8R35, KMUH108-8M33, KMUH108-8M35, KMUH108-8M36, KMUH106-6M30, KMUH105-5M21, KMUH104-4M25, KMUHS10801, KMUHS10804, KMUHS10807) and Center for Cancer Research, Kaohsiung Medical University (KMU-TC108A04). In addition, this study was supported by the Grant of Taiwan Precision Medicine Initiative and Biomarker Discovery in Major Diseases of Taiwan Project (AS-BD-108-1), Academia Sinica, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

WC Su, CW Huang, JY Wang were responsible for conception and design of this study. All authors contributed to acquisition of data. WC Su analyzed and interpreted the patient data prior to drafting and completing the manuscript. JY Wang made critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. World Health Organization Cancer – Key Facts (Organization Updated Information on 12th September 2018) World Health Organization; [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 31]. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare. Ministry of Health and Welfare 2017 Statistics of Causes of Death. Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare; [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/cp-3961-42866-2.html . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen CF, Lin YC, Tsai HL, Huang CW, Yeh YS, Ma CJ, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted surgery, mini-laparotomy and conventional laparotomy in patients with Stage I-III colorectal cancer. J Minim Access Surg. 2018;14:321–34. doi: 10.4103/jmas.JMAS_155_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD. The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery–The clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg. 1982;69:613–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800691019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arbman G, Nilsson E, Hallböök O, Sjödahl R. Local recurrence following total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1996;83:375–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kusters M, Marijnen CA, van de Velde CJ, Rutten HJ, Lahaye MJ, Kim JH, et al. Patterns of local recurrence in rectal cancer: A study of the Dutch TME trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:470–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grass JK, Perez DR, Izbicki JR, Reeh M. Systematic review analysis of robotic and transanal approaches in TME surgery-A systematic review of the current literature in regard to challenges in rectal cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45:498–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arezzo A, Passera R, Ferri V, Gonella F, Cirocchi R, Morino M. Laparoscopic right colectomy reduces short-term mortality and morbidity. Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1457–72. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathis KL, Nelson H. Controversies in laparoscopy for colon and rectal cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2014;23:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang MJ, Liang JL, Wang H, Kang L, Deng YH, Wang JP. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open surgery for rectal cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on oncologic adequacy of resection and long-term oncologic outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:415–21. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-1091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trastulli S, Cirocchi R, Listorti C, Cavaliere D, Avenia N, Gullà N, et al. Laparoscopic vs open resection for rectal cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e277–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, et al. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): Multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1718–26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bianchi PP, Ceriani C, Locatelli A, Spinoglio G, Zampino MG, Sonzogni A, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: A comparative analysis of oncological safety and short-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2888–94. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baek JH, Pastor C, Pigazzi A. Robotic and laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: A case-matched study. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:521–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang J, Yoon KJ, Min BS, Hur H, Baik SH, Kim NK, et al. The impact of robotic surgery for mid and low rectal cancer: A case-matched analysis of a 3-arm comparison – Open, laparoscopic, and robotic surgery. Ann Surg. 2013;257:95–101. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182686bbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baukloh JK, Reeh M, Spinoglio G, Corratti A, Bartolini I, Mirasolo VM, et al. Evaluation of the robotic approach concerning pitfalls in rectal surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:1304–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin NL, Wang HS, Jiang JK, Lin HH, Lin CC, Lan YT, et al. The surgical outcome of tumor resection surgery for octogenarian patients with colorectal cancer. J Soc Colon Rectal Surg (Taiwan) 2018;29:22–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data – Life Expectancy. World Health Organization; [Last accessed on 2018 Oct 31]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/life_tables/situation_trends/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang CM, Huang MY, Tsai HL, Huang CW, Ma CJ, Yeh YS, et al. An observational study of extending FOLFOX chemotherapy, lengthening the interval between radiotherapy and surgery, and enhancing pathological complete response rates in rectal cancer patients following preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:702–12. doi: 10.1177/1756283X16656690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang MY, Lee HH, Tsai HL, Huang CW, Yeh YS, Ma CJ, et al. Comparison of efficacy and safety of preoperative chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced upper and middle/lower rectal cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13:53. doi: 10.1186/s13014-018-0987-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang CW, Yeh YS, Su WC, Tsai HL, Choy TK, Huang MY, et al. Robotic surgery with high dissection and low ligation technique for consecutive patients with rectal cancer following preoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:1169–77. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2581-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang CW, Tsai HL, Yeh YS, Su WC, Huang MY, Huang CM, et al. Robotic-assisted total mesorectal excision with the single-docking technique for patients with rectal cancer. BMC Surg. 2017;17:126. doi: 10.1186/s12893-017-0315-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: The 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual and the Future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gress DM, Edge SB, Greene FL, Washington MK, Asare EA, Brierley JD, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York City: American College of Surgeons, Principles of Cancer Staging – American Joint Committee on Cancer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang CW, Yeh YS, Ma CJ, Choy TK, Huang MY, Huang CM, et al. Robotic colorectal surgery for laparoscopic surgeons with limited experience: Preliminary experiences for 40 consecutive cases at a single medical center. BMC Surg. 2015;15:73. doi: 10.1186/s12893-015-0057-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen CW, Chen MJ, Yeh YS, Tsai HL, Chang YT, Wang JY. Intraoperative anastomotic dye test significantly decreases incidence of anastomotic leaks in patients undergoing resection for rectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:579–83. doi: 10.1007/s10151-012-0910-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin TC, Tsai HL, Yang PF, Su WC, Ma CJ, Huang CW, et al. Early closure of defunctioning stoma increases complications related to stoma closure after concurrent chemoradiotherapy and low anterior resection in patients with rectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:80. doi: 10.1186/s12957-017-1149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng Y. Rectal cancer in Asian vs? Western countries: Why the variation in incidence. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:64. doi: 10.1007/s11864-017-0500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devesa SS, Chow WH. Variation in colorectal cancer incidence in the United States by subsite of origin. Cancer. 1993;71:3819–26. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930615)71:12<3819::aid-cncr2820711206>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simmonds PD, George S, Baughan C, Buchanan R, Davis C, Fentiman I, et al. Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group. Surgery for colorectal cancer in elderly patients: A systematic review. Lancet. 2000;356:968–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biondi A, Vacante M, Ambrosino I, Cristaldi E, Pietrapertosa G, Basile F. Role of surgery for colorectal cancer in the elderly. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:606–13. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i9.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Limpert P, Longo WE, Kelemen PR, Vernava AM, Bahadursingh AN, Johnson FE, et al. Colon and rectal cancer in the elderly. High incidence of asymptomatic disease, less surgical emergencies, and a favorable short-term outcome. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;48:159–63. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hermans E, van Schaik PM, Prins HA, Ernst MF, Dautzenberg PJ, Bosscha K. Outcome of colonic surgery in elderly patients with colon cancer. J Oncol. 2010;2010:865908. doi: 10.1155/2010/865908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nitsche U, Späth C, Müller TC, Maak M, Janssen KP, Wilhelm D, et al. Colorectal cancer surgery remains effective with rising patient age. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:971–9. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1914-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ceccarelli G, Andolfi E, Biancafarina A, Rocca A, Amato M, Milone M, et al. Robot-assisted surgery in elderly and very elderly population: Our experience in oncologic and general surgery with literature review. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2017;29:55–63. doi: 10.1007/s40520-016-0676-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tokuhara K, Nakatani K, Ueyama Y, Yoshioka K, Kon M. Short-and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer in the elderly: A prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2016;27:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mirkin KA, Kulaylat AS, Hollenbeak CS, Messaris E. Robotic versus laparoscopic colectomy for Stage I-III colon cancer: Oncologic and long-term survival outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:2894–901. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5999-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Jesus JP, Valadão M, de Castro Araujo RO, Cesar D, Linhares E, Iglesias AC. The circumferential resection margins status: A comparison of robotic, laparoscopic and open total mesorectal excision for mid and low rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:808–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrey A. The short-term results of Da Vinci robotic rectal resection for malignant and benign tumors. Adv Res Gastroentero Hepatol. 2018;10:555780. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao DB, Wu YK, Shao YF, Wang CF, Cai JQ. Prognostic factors for 5-year survival after local excision of rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1242–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim YJ. Colorectal cancer surgery in elderly patients. Ann Coloproctol. 2017;33:121–2. doi: 10.3393/ac.2017.33.4.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Modini C, Romagnoli F, De Milito R, Romeo V, Petroni R, La Torre F, et al. Octogenarians: An increasing challenge for acute care and colorectal surgeons. An outcomes analysis of emergency colorectal surgery in the elderly. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e312–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hellan M, Ouellette J, Lagares-Garcia JA, Rauh SM, Kennedy HL, Nicholson JD, et al. Robotic rectal cancer resection: A retrospective multicenter analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2151–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim YS, Kim MJ, Park SC, Sohn DK, Kim DY, Chang HJ, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer after preoperative chemoradiotherapy: Case-matched study of short-term outcomes. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48:225–31. doi: 10.4143/crt.2014.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feroci F, Vannucchi A, Bianchi PP, Cantafio S, Garzi A, Formisano G, et al. Total mesorectal excision for mid and low rectal cancer: Laparoscopic vs robotic surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3602–10. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i13.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hellan M, Anderson C, Ellenhorn JD, Paz B, Pigazzi A. Short-term outcomes after robotic-assisted total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3168–73. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9544-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adam IJ, Mohamdee MO, Martin IG, Scott N, Finan PJ, Johnston D, et al. Role of circumferential margin involvement in the local recurrence of rectal cancer. Lancet. 1994;344:707–11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quirke P, Steele R, Monson J, Grieve R, Khanna S, Couture J, et al. Effect of the plane of surgery achieved on local recurrence in patients with operable rectal cancer: A prospective study using data from the MRC CR07 and NCIC-CTG CO16 randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2009;373:821–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60485-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quirke P. Training and quality assurance for rectal cancer: 20 years of data is enough. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:695–702. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kwak JM, Kim SH. Robotic surgery for rectal cancer: An update in 2015. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48:427–35. doi: 10.4143/crt.2015.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park EJ, Cho MS, Baek SJ, Hur H, Min BS, Baik SH, et al. Long-term oncologic outcomes of robotic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: A comparative study with laparoscopic surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;261:129–37. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghezzi TL, Luca F, Valvo M, Corleta OC, Zuccaro M, Cenciarelli S, et al. Robotic versus open total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: Comparative study of short and long-term outcomes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1072–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.02.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cho MS, Baek SJ, Hur H, Min BS, Baik SH, Lee KY, et al. Short and long-term outcomes of robotic versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: A case-matched retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e522. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park JS, Choi GS, Lim KH, Jang YS, Jun SH. S052: A comparison of robot-assisted, laparoscopic, and open surgery in the treatment of rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:240–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1166-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]