To The Editor,

Organ dysfunction in light chain (AL) amyloidosis results from deposition of misfolded monoclonal free light chains (FLC). A rapid reduction in FLC levels correlates with improvement in organ function and survival, and patients not achieving at least very good partial response (VGPR) have poor outcomes.(1, 2) The current hematologic response criteria for AL amyloidosis define complete response (CR) as no evidence of monoclonal protein based on serum and urine immunofixation, as well as achieving a normal FLC ratio. VGPR is defined as achieving a dFLC (difference in involved and uninvolved light chain) of < 4 mg/dL.(1) The response criteria do not take the levels of involved FLC (iFLC) into consideration. However, even low levels of amyloidogenic monoclonal FLC can result in organ dysfunction.(3–5) Recent data from our group shows that increased level of iFLCs at the time of normal FLC ratio or VGPR or better response are associated with inferior outcomes.(6, 7) Additionally, achievement of CR requires a normal FLC ratio, which can be skewed by discordant suppression of light chain levels.(8) We sought to examine the role of iFLC levels and FLC ratio in patients who have achieved a normal serum immunofixation and do not have any evidence of monoclonal protein in urine.

Patients with AL amyloidosis diagnosed from 2006–15 who achieved CR with first-line therapy [CR group] or VGPR, but who met all criteria for CR, except that they had an abnormal FLC ratio were included [IFE negative VGPR group]. Serum FLC levels were as categorized as high, low or normal based on reference range of the Freelite assay (The Binding Site); lambda: 0.57–2.63 mg/dL, kappa: 0.3–1.94 mg/dL, kappa/lambda ratio 0.26–1.65.(9) Organ involvement/ response were assessed by established criteria. (1, 10, 11) Responses were assessed as best response to first-line therapy. Progression free survival (PFS) was defined as time from start of first line therapy to relapse/progression requiring a change in treatment or death. Landmark survival analysis from best response was also conducted. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and patients provided consent for use of data for research.

Overall, 170 patients met the inclusion criteria, CR: 148; and IFE negative VGPR with abnormal FLC ratio: 22. The median estimated follow-up from start of therapy was 69 months. Median time to best response was 4.7 months (inter-quartile range, IQR: 2.5 – 10.0), with no difference in the CR vs. VGPR group (p=0.62). Elevated iFLC levels were seen in 22% (32/148) in the CR group and 50% (11/22) of patients in the IFE negative VGPR group. The baseline characteristics at diagnosis of the entire cohort and the two groups are described in detail in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. Median age at diagnosis was 60 years, 64% (n=108) were males and the iFLC was lambda in 76% (n=129) of patients. The median dFLC was 20.4 mg/dL (IQR: 9.9–55.1) and median bone marrow plasma cells (BMPC) were 10% (IQR 5–10%). Organ involvement was as follows: heart: 64% (n=108), kidney: 62% (n=105) and liver: 17% (n=28). Distribution of patients by the Mayo 2012 stage [% (n), N=159] was: 28/27/25/20 (n=44/43/40/32). Distribution per the renal stage [% (n), N=166] was 55/34/11%, (n=91/56/19). The two cohorts were similar in all baseline characteristics except the involved light chain type (CR vs. VGPR, lambda 80% vs. 50%, p=0.004) and distribution of patients across the renal stage (renal stage 1/2/3, %: 54/37/9 vs. 62/9/29, p=0.005). There was no difference in proportion of patients with GFR ≤30 ml/min in CR vs. VGPR groups. Proportion of patients with eGFR ≤ 30 ml/min/m2 in elevated vs. normal/low iFLC patients was 21% (11/127) vs 9% (9/43), p=0.04. Median time to best hematologic response was 4.7 months, with no difference in time to achieve best response in patients with normal vs. elevated iFLC levels (Supplementary Table S3). Treatment was autologous stem cell transplant based in 52% (n=89), proteasome inhibitor based in 20% (n=34), alkylator based in 26% (n=45) and immunomodulatory drugs in 1% (n=2) of patients.

Survival outcomes, (Figure 1a-d):

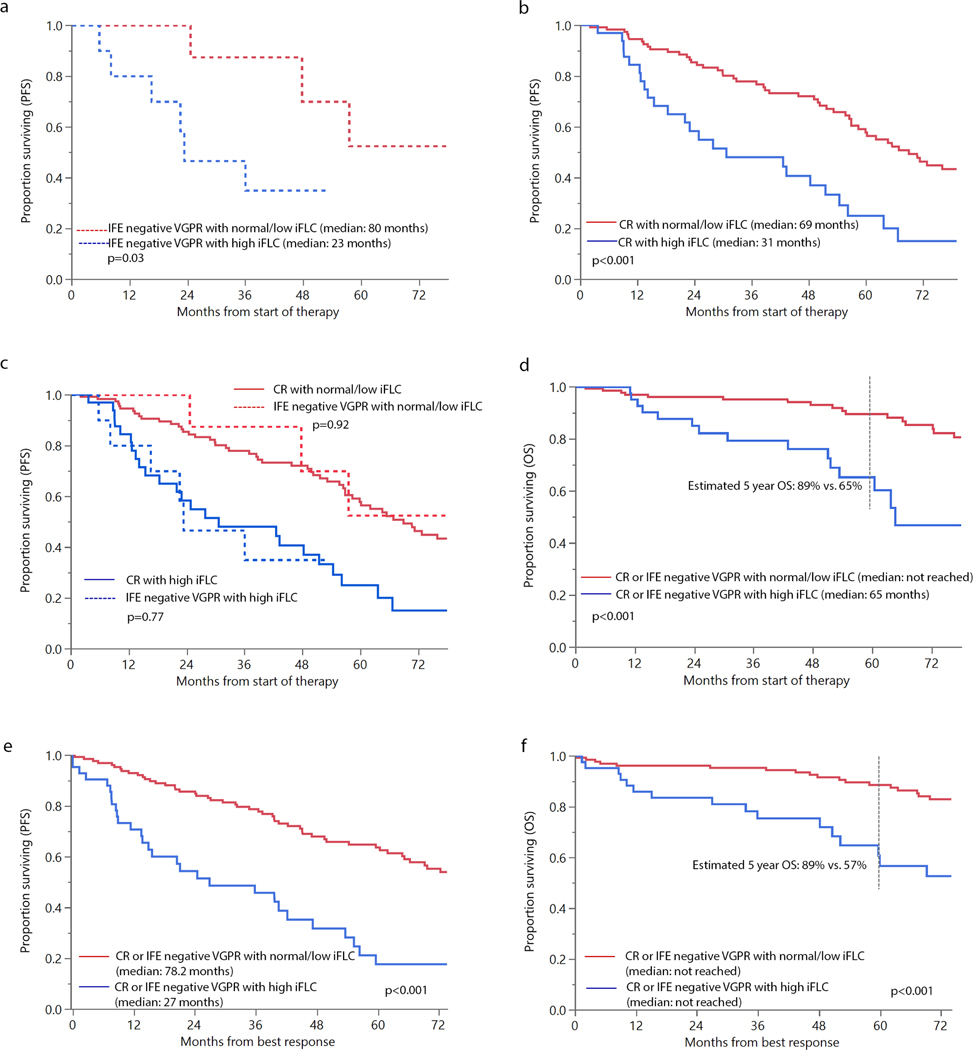

Figure 1:

Survival based on levels of involved light chain (iFLC), elevated vs. normal/low (a) progression free survival (PFS) in patients with immunofixation (IFE) negative very good partial response (VGPR) with abnormal free light chain ratio; (b) PFS in patients with complete response; (c) PFS in patients with CR or IFE negative VGPR with abnormal ratio; and (d) overall survival (OS) in patients with elevated vs. normal/low levels of iFLC (e) landmark PFS from best response in patients with elevated vs. normal/low levels of iFLC (f) landmark OS from best response in patients with elevated vs. normal/low levels of iFLC

Amongst the patients with IFE negative VGPR, PFS was significantly better in patients with normal/low iFLC levels vs. elevated iFLC levels (80 vs. 23 months, p=0.03). Similarly, in the CR group, median PFS was longer in the low/normal vs. high iFLC group (69 vs. 31 months, p<0.001). When these groups were analyzed together (Figure 1c), PFS was similar in the VGPR and CR group for patients with low/normal iFLC (p=0.92) and those with high iFLC (p=0.77), suggesting that in patients achieving negative immunofixation, outcomes were more dependent on iFLC levels than achieving a normal FLC ratio. Overall survival (OS) was significantly longer in low/normal iFLC group (median OS not reached vs. 65 months, p<0.001). Estimated 5 year OS was 89% vs. 65%, respectively. Landmark analyses from time of best response also demonstrated superior OS and PFS in patients with normal/low iFLC. (Figure 1e-f) As shown in Table 1, iFLC levels were independent predictors of both PFS and OS, even after adjusting for known prognostic (Mayo 2012 stage, presence of ≥ 10% BMPCs at diagnosis) and confounding (GFR ≤ 30 ml/min/m2) factors. OS was similar in patients in CR vs. IFE negative VGPR, with median OS not reached in the CR group vs. 111 months in the IFE negative VGPR group, p=0.4.

Table 1:

Multivariate survival analysis for progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with CR or immunofixation negative VGPR with abnormal FLC ratio

| HR with 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Progression free survival | ||

| iFLC level: elevated vs. normal/low | 3.17 (1.97–5.12) | <0.001 |

| Mayo 2012 stage (3/4 vs. 1/2) | 1.51 (0.94–2.42) | 0.09 |

| BMPCs ≥ 10%, yes vs. no | 1.34 (0.84–2.13) | 0.22 |

| GFR ≤ 30 ml/min/m2 | 0.67 (0.31–1.46) | 0.31 |

| Overall survival | ||

| iFLC: elevated vs. normal/low | 3.60 (1.73–7.51) | <0.001 |

| Mayo 2012 stage (3/4 vs. 1/2) | 2.71 (1.27–5.79) | 0.01 |

| BMPCs ≥ 10%, yes vs. no | 1.71 (0.81–3.58) | 0.16 |

| GFR ≤ 30 ml/min/m2 | 0.75 (0.27–2.10) | 0.59 |

Abbreviations: BMPCs: bone marrow plasma cells; CI: confidence interval; CR: complete response; HR: hazard ratio; iFLC: involved light chain; VGPR: very good partial response

Number of patients included in multivariate analysis: 157. Time zero in multivariate analysis was start of first-line therapy.

Organ response:

Patients with low/normal iFLC had higher rates of cardiac response [86% (60/70) vs. 54% (15/28), p=0.001) and renal response [84% (61/73) vs. 56% (14/25), p=0.007]. No difference was observed in rates of liver response [78% (14/18) vs. 71% (5/7), p=0.74], though number of patients was small in this group. (Supplementary Table S4) Amongst patients in CR, patients with low/normal iFLC had higher cardiac response rates compared with patients in CR with high iFLC levels [88% (56/64) vs. 52% (12/23), p=0.001]. Similarly, renal response rates were also higher in patients with low/normal iFLC with CR [86% (59/69) vs. 61% (11/18), p=0.03]. Sample size for assessment of organ response in patients with IFE negative VGPR was small. There was no difference in cardiac response in patients with normal iFLC (67%, 4/6) vs. elevated iFLC (60%, 3/5), p=0.82. Similarly, there was no difference in renal response amongst patients with normal iFLC (40%, 2/4) vs. elevated iFLC (43%, 3/7), p=0.82. Although the sample size was small, we did not observe any statistically significant difference in cardiac response rates amongst patients with CR (78%, 68/87) vs. IFE negative VGPR with low/normal (67%, 4/6), p=0.53. Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in renal response rates amongst patients with CR (80%, 70/87) vs. IFE negative VGPR with low/normal iFLC (50%, 2/4), p=0.19.

We observed that in patients with no evidence of monoclonal protein by immunofixation, the levels of iFLC predict for survival and organ response, while FLC ratio does not appear to impact outcomes. The normal range for FLC ratio was derived from a study of normal controls/polyclonal hypergammaglobulinema(9), but achievement of a normal ratio by itself has never been shown to independently predict for organ response or survival in AL amyloidosis. It is simply used as a surrogate for presence of monoclonal FLCs. However, there can be many factors including suppression of non-clonal light chains due to current effective therapies, immune reconstitution of the non-clonal light chain, etc. which may result in an abnormal ratio. It has been demonstrated that in patients with CR/VGPR, normalization of FLC ratio does not impact outcomes.(7) It is important to note that variation in iFLC, especially at low levels can be high resulting in some inconsistency from one measurement to the other; however the highest variation is seen with FLC ratio, which makes it less reliable for disease monitoring.(12) Different from prior reports(6, 7), this study included immunofixation negative patients only to evaluate the impact of iFLC level and FLC ratio with respect to CR criteria. Achievement of dFLC<1mg/dL has been associated with improved organ response and time to next therapy, but not OS based on data available to date.(13) Similarly, we observed superior PFS (Not reached vs. 64.6 months, p<0.001), but not OS (Not reached vs. 110.7 months, p=0.42) improvement in patients achieving dFLC<1mg/dL. (Supplementary results)

These findings taken together suggest a need to reconsider the criteria for defining CR. We propose that CR be defined as achieving negative immunofixation in serum and urine and achieving normal or low levels of iFLC, while the presence of an abnormal FLC ratio should not preclude a patient being categorized as CR. Specifically, an abnormal FLC ratio skewed in favor of the non-amyloidogenic (uninvolved) FLC should be considered as “normalized” for the purpose of defining CR as suppression of the uninvolved LC can result in this abnormal FLC ratio. Normalization of FLC level has also previously been recommended as a criterion for CR in consensus guidelines for conducting clinical trials.(14) The limitation of this approach would be that in a small number of patients, FLC can be elevated due to renal dysfunction. We had a limited number of patients with renal dysfunction in our dataset to allow for subset analysis. A bone marrow biopsy to determine presence of monoclonal plasma cells can provide clarification in such patients.(15)

Limitations of our study include its retrospective nature and lack of a validation dataset. Our findings need to be validated independently by other investigators in large datasets, including in larger subsets of patients with renal dysfunction and patients treated with different therapies.

In conclusion, patients who achieved low/normal iFLC at the time of CR/conventional VGPR have superior outcomes, even if they have an abnormal FLC ratio.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

RESEARCH SUPPORT/GRANT FUNDING: Amyloidosis Foundation (SS and MAG)

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: SS: Honoraria (advisory board), Janssen; AD: Research Funding from Celgene, Takeda, Prothena, Jannsen, Pfizer, Alnylam, GSK; PK: Research Funding from Celgene, Takeda. MQL: Research Funding from Celgene; MAG: Honoraria/consultancy from Ionis, Alnylam, Prothena, Celgene, Janssen, Specytrum, Annexon, Apellis, Amgen, Medscape, Abbvie, Research to Practice, Physcians Education Resource and Teva; SKK: Research Funding and membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees: AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen, KITE, Merck. Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees: Oncopeptides, Takeda. Research funding from Novartis and Roche.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: All potential conflicts of interest have been disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Palladini G, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Kumar S, Wechalekar A, Hawkins PN, et al. New criteria for response to treatment in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis based on free light chain measurement and cardiac biomarkers: impact on survival outcomes. Journal of clinical oncology. 2012;30(36):4541–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Hayman SR, Buadi FK, Zeldenrust SR, et al. Changes in serum-free light chain rather than intact monoclonal immunoglobulin levels predicts outcome following therapy in primary amyloidosis. American journal of hematology. 2011;86(3):251–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sidana S, Tandon N, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Buadi FK, Lacy MQ, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes in light chain amyloidosis patients with non-evaluable serum free light chains. Leukemia. 2018;32(3):729–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milani P, Basset M, Russo F, Foli A, Merlini G, Palladini G. Patients with light-chain amyloidosis and low free light-chain burden have distinct clinical features and outcome. Blood. 2017;130(5):625–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dittrich T, Bochtler T, Kimmich C, Becker N, Jauch A, Goldschmidt H, et al. AL amyloidosis patients with low amyloidogenic free light chain levels at first diagnosis have an excellent prognosis. Blood. 2017;130(5):632–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tandon N, Sidana S, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Dingli D, et al. Impact of involved free light chain (FLC) levels in patients achieving normal FLC ratio after initial therapy in light chain amyloidosis (AL). American journal of hematology. 2018;93(1):17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muchtar E, Dispenzieri A, Leung N, Lacy MQ, Buadi FK, Dingli D, et al. Optimizing deep response assessment for AL amyloidosis using involved free light chain level at end of therapy: failure of the serum free light chain ratio. Leukemia. 2019;33(2):527–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singhal S, Vickrey E, Krishnamurthy J, Singh V, Allen S, Mehta J. The relationship between the serum free light chain assay and serum immunofixation electrophoresis, and the definition of concordant and discordant free light chain ratios. Blood. 2009;114(1):38–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katzmann JA, Clark RJ, Abraham RS, Bryant S, Lymp JF, Bradwell AR, et al. Serum reference intervals and diagnostic ranges for free kappa and free lambda immunoglobulin light chains: relative sensitivity for detection of monoclonal light chains. Clinical chemistry. 2002;48(9):1437–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palladini G, Hegenbart U, Milani P, Kimmich C, Foli A, Ho AD, et al. A staging system for renal outcome and early markers of renal response to chemotherapy in AL amyloidosis. Blood. 2014;124(15):2325–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gertz MA, Comenzo R, Falk RH, Fermand JP, Hazenberg BP, Hawkins PN, et al. Definition of organ involvement and treatment response in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL): a consensus opinion from the 10th International Symposium on Amyloid and Amyloidosis, Tours, France, 18–22 April 2004. American journal of hematology. 2005;79(4):319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katzmann JA, Snyder MR, Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Benson JT, et al. Long-term biological variation of serum protein electrophoresis M-spike, urine M-spike, and monoclonal serum free light chain quantification: implications for monitoring monoclonal gammopathies. Clinical chemistry. 2011;57(12):1687–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manwani R, Sharpley F, Mahmood S, Sachchithanantham S, Lachmann H, Gillmore J, et al. Achieving a Difference in Involved and Uninvolved Light Chains (dFLC) of Less Than 10mg/L Is the New Goal of Therapy in Systemic AL Amyloidosis: Analysis of 916 Patients Treated Upfront with Bortezomib-Based Therapy. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):3262-. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comenzo RL, Reece D, Palladini G, Seldin D, Sanchorawala V, Landau H, et al. Consensus guidelines for the conduct and reporting of clinical trials in systemic light-chain amyloidosis. Leukemia. 2012;26(11):2317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sidana S, Tandon N, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Rajkumar SV, Kumar SK. The importance of bone marrow examination in patients with light chain amyloidosis achieving a complete response. Leukemia. 2018;32(5):1243–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.