Abstract

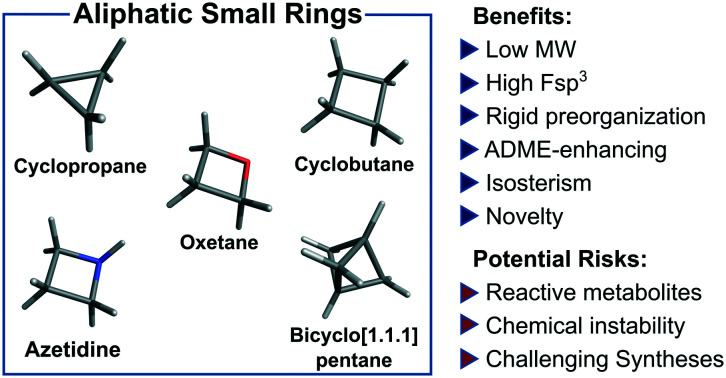

Aliphatic three- and four-membered rings including cyclopropanes, cyclobutanes, oxetanes, azetidines and bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes have been increasingly exploited in medicinal chemistry for their beneficial physicochemical properties and applications as functional group bioisosteres. This review provides a historical perspective and comparative up to date overview of commonly applied small rings, exemplifying key principles with recent literature examples. In addition to describing the merits and advantages of each ring system, potential hazards and liabilities are also illustrated and explained, including any significant chemical or metabolic stability and toxicity risks.

Aliphatic small rings including cyclopropanes, cyclobutanes, oxetanes, azetidines and bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes have been increasingly exploited in medicinal chemistry. This review summarises judicious successful application and reported limitations of these ring systems.

Introduction

Aliphatic 3- and 4-membered ring systems are commonplace within modern medicinal chemistry, frequently exhibiting favourable structural and physicochemical properties which have proven advantageous to molecular optimisation. Such properties generally stem from their intrinsic small size and rigidity, presenting atom-efficient three-dimensional structural scaffolds with defined vectors for pendant functionality.1 These vectors, combined with potential to make specific polar interactions, provide opportunity for potency and selectivity optimisation through protein-ligand complementarity and molecular pre-organisation. Small rings have been frequently applied to provide new intellectual property space through scaffold hops2 or, in certain cases, bioisosteric replacements for other ring systems or functional groups,3–6 sometimes providing improved properties, such as reduced hERG liability, through LogD and pKa modulation.7,8 Such rigid compounds can also be less susceptible to oxidative metabolism by promiscuous cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes than more flexible systems, through less favourable recognition and electronics for single electron oxidation. Furthermore, in contrast to planar aromatic rings, small aliphatic rings increase overall fraction of sp3 carbons (Fsp3), offering the potential for improved solubility owing to non-planar substituent vectors, disfavouring planar intermolecular crystal-packing interactions.1,9–11

Although some small rings such as cyclopropanes12 have been applied successfully in drug discovery for many years, others such as oxetanes and azetidines have seen increased application and popularity more recently. This in part aligns with increased commercial availability of building blocks containing these rings, plus improved synthetic methods to enable their incorporation into medicinal molecules. Some, such as bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes and numerous fused and spirocyclic variants of small rings, have only been popularised recently and, although medicinal chemistry applications of these have been limited to date, it is anticipated that more examples will appear in due course, enabling better assessment of their value to drug discovery programs.

In this review, aliphatic small rings which have general application and utility in medicinal chemistry are discussed: cyclopropanes (CyPr), cyclobutanes (CyBu), oxetanes, azetidines and bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes (BCP; Fig. 1). The attractive medicinal chemistry properties associated with each ring system have been exemplified and potential intrinsic limitations and mitigation strategies are described. As several of these ring systems have been reviewed separately in the past, the focus is largely on recent examples of contemporary medicinal chemistry application. In order to retain focus specifically on broadly useful rings, a few established small rings are not reviewed here. These include aziridines,13 epoxides,14 β-lactams,15–17 squaramides18,19 and diazirines,20–22 which have seen specific applications related to their chemical reactivities, but which have largely precluded more general applications in medicinal chemistry: aziridines and epoxides have seen limited application due to their inherent electrophilic reactivity, although several drugs including thiotepa, mitomycin, eplerenone, fosfomycin, scopolamine and tiotropium do contain these rings, often as covalent antibiotics or alkylating agents; β-lactams are also synonymous with antibiotics, owing to the ability to form covalent adducts with penicillin binding proteins resulting in inhibition of bacterial cell wall biosynthesis;15–17 diazirines have been applied widely as photoaffinity reagents for covalent cross-linking to proteins upon ultraviolet photoactivation.20–22

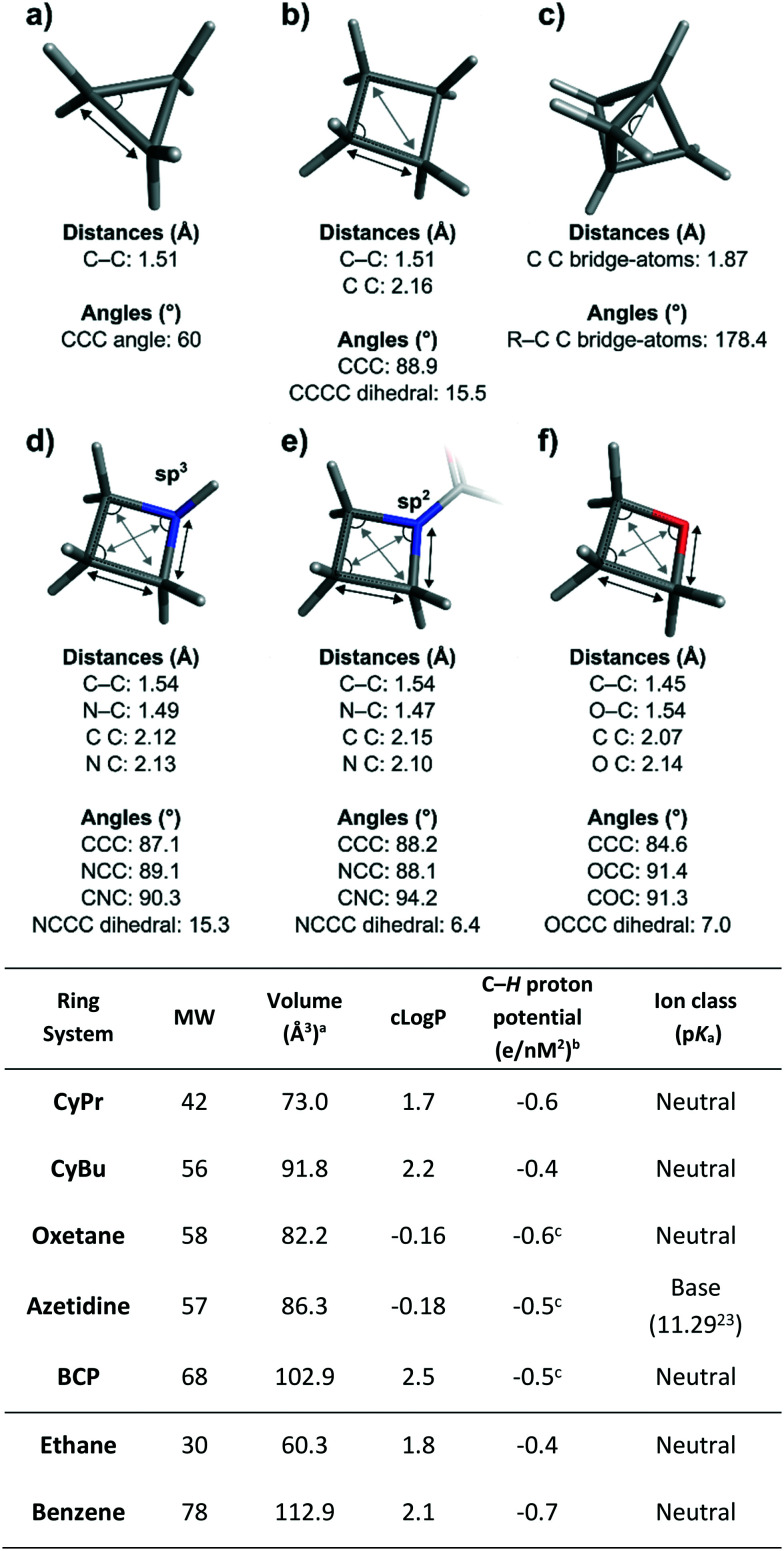

Fig. 1. Top: Median values for key structural parameters of the small rings featured in this review. a) Cyclopropane. b) Cyclobutane. c) Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane. d) Azetidine with sp3 hybridised nitrogen atom. e) Azetidine with sp2 hybridised nitrogen atom. f) Oxetane. Ring systems are depicted without substituents except for the azetidine with sp2 nitrogen. Bonded (A–A) and non-bonded atom distances (A A) are highlighted respectively with black and grey arrows and non-redundant angles are shown as circular segments. Statistics were generated via analysis of data from the Cambridge Structural Database, the Protein Data Bank, and in-house X-ray data using RDkit24 for substructure matching and computation of geometric values, and Spotfire for statistical analysis.25 The analysis included spirocyclic derivatives but not fused and bridged systems (with the exception of bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes). Bottom: Structural and physicochemical features of the ring systems featured in this review. Benzene and ethane are included for comparison. aVan der Waals volume. bMeasured using COSMO surfaces.26,27cMost polarized protons (C–H adjacent to heteroatom for oxetane and azetidine; bridgehead C–H for BCP).

Cyclopropanes

Introduction

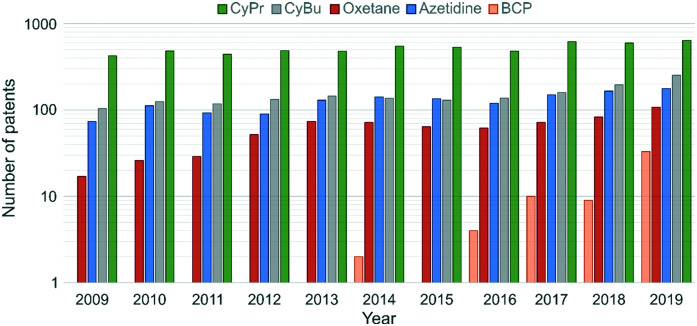

Cyclopropane (CyPr) rings are the most ubiquitous small ring system in medicinal chemistry. They appear in >60 marketed pharmaceutical agents with a wide variety of indications from Oncology to HIV.12 In 2019, CyPr rings featured in 642 patent applications, and have consistently been the most frequently used small ring in the patent literature (Fig. 2).28 The reasons for its prevalence are many-fold but primarily hinge upon the unique structure and physicochemical properties of the ring.

Fig. 2. Number of drug substance patents containing CyPr, CyBu, oxetane, azetidine and BCP substructures filed between 2009 and 2019.28 β-Lactones and β-lactams were excluded from the analysis.

Structural features and physicochemical properties of cyclopropanes

The unique characteristics of the CyPr group arise from the 60° internal angle (Fig. 1). This creates a planar, rigid structure with well-defined exit vectors and significant ring strain (27.5 kcal mol−1).29 The internal C–C bonds have more p-character and, as such, they are often considered pseudo double bonds, despite retaining a bond length (1.51 Å) closer to an aliphatic C–C bond. As a further consequence of the ring strain, the C–H bonds have more s-character and are shorter, stronger and more polarised than conventional C–H bonds (see table in Fig. 1). On average the CyPr ring is 0.2 and 0.5 log units less lipophilic than iPr groups and phenyl rings respectively, making it an attractive substituent for medicinal chemistry applications.30

Medicinal chemistry applications of cyclopropanes

CyPr groups have found extensive use in medicinal chemistry and have been employed to increase potency, provide conformational stability, and improve pharmacokinetics (PK) and solubility.12 They are frequently used as isosteres for small alkyl groups (e.g. Me and iPr), aromatic rings and alkenes. The use of CyPr in marketed drugs has been extensively reviewed12 and this section will focus on contemporary applications and limitations of their use.

Isopropyl isostere

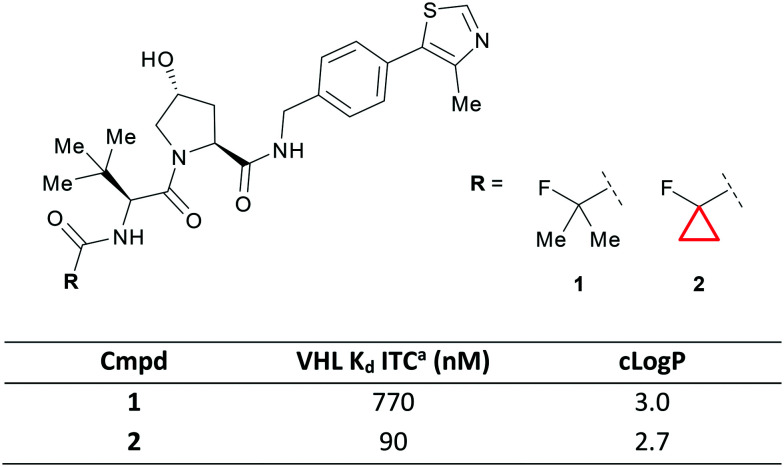

The E3 ligase Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) is an important target in medicinal chemistry due to its role in protein degradation. Bifunctional ligands containing a VHL binding warhead are able to harness this ligase to promote ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of target proteins.31,32 Due to the increased size requirements for a bifunctional ligand, efficient warheads for the E3 ligases such as VHL will be crucial to their success. Ciulli et al. recently showed that a small lipophilic CyPr was an optimal substituent in a series of peptide mimetics.33 Switching from iPr 1 to CyPr 2 gave a 9-fold increase in potency against the target which the authors attributed to the binding pocket being more accommodating to the smaller, constrained CyPr analogue (Fig. 3). The CyPr was also less lipophilic, an important consideration when working in ‘beyond rule-of-5’ space.34

Fig. 3. CyPr as an iPr isostere in the optimisation of VHL ligands.33aIsothermal titration calorimetry.

This VHL warhead was subsequently used by the same authors in the development of BAF degraders where the CyPr group formed a crucial part of the ternary complex interface.35 The iPr to CyPr change is one that is often employed by medicinal chemists during systematic structure–activity relationship (SAR) exploration36 and there are also numerous examples where the CyPr is detrimental to affinity.37,38 Additionally, this change is often exploited to improve metabolic stability, due to the shorter, stronger bonds in CyPr compared to iPr,12 however, this was not discussed during the optimisation of VHL ligands.

Aromatic ring replacement

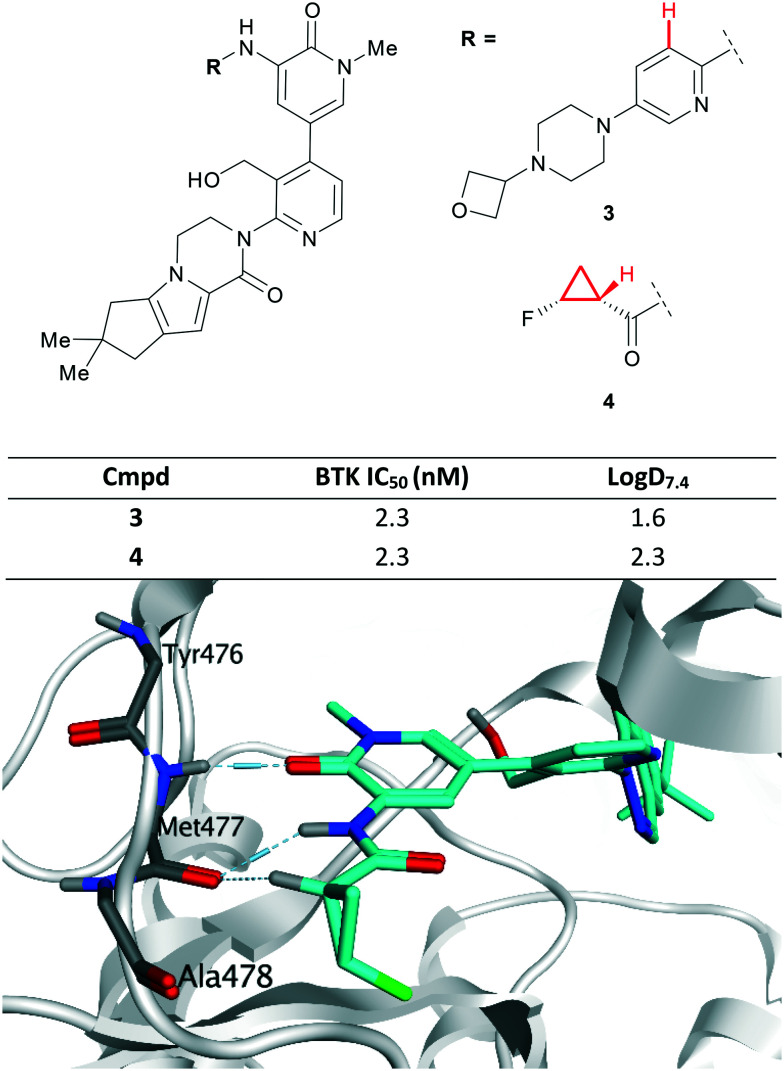

The CyPr group has long been recognised as a viable replacement for aromatic rings that can improve the physicochemical properties of the molecule through increased Fsp.3 Recently, scientists at Genentech reported 3 as a noncovalent inhibitor of Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) (Fig. 4).39 However, there was concern that the presence of a 2,5-diaminopyridine represented a structural hazard and could cause drug induced liver injury through in vivo bioactivation.40 Replacement of the aromatic ring with an amide F-CyPr 4 maintained potency despite a significant reduction in molecular weight.41 X-ray crystallography revealed that the carbonyl oxygen overlapped with the pyridine nitrogen and that the polarised α-carbonyl CyPr proton makes a hydrogen bond to a kinase hinge carbonyl (previously made by the pyridine C–H; highlighted in Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Top: Optimisation of BTK inhibitors by replacement of a 2,5-diaminopyridine, a potential structural hazard.41 Bottom: Close-up view of 4 (cyan) bound to BTK (PDB code: 6XE4), highlighting hydrogen bonding interactions (pale blue dashed lines) with the hinge (Met477), including nonclassical hydrogen bond with the polarised CyPr proton.41.

Further optimisation of the cyclopenta[4,5]pyrrolo[1,2-a]piperazinone moiety present in 4 resulted in a lead series, however further progress was halted due to hERG activity.41

Conformational stability

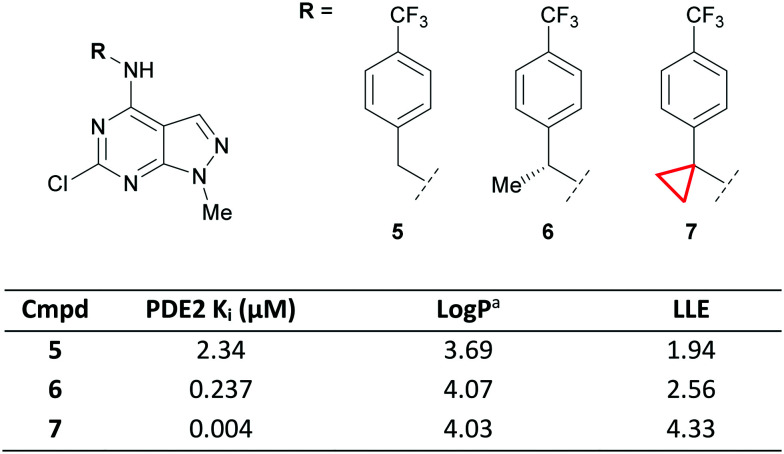

The ability of the CyPr group to constrain aliphatic systems is well documented and has been used in the development of drugs such as lemborexant.42 A CyPr ring was also used to constrain a benzyl group during the development of a series of phosphodiesterase 2 (PDE2) inhibitors.43 Extending out from a fragment hit into a lipophilic pocket with a para-CF3 benzyl group gave lead compound 5 with 2.34 μM affinity for PDE2 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Optimisation of PDE2 ligands via conformational stabilisation.43aLog P = Alog P98.44.

Initial attempts to improve the potency identified methyl substituted 6 with a 10-fold increase in PDE2 affinity over 5. Molecular modelling suggested that a CyPr group would stabilise the bioactive conformation by allowing it to adopt the preferred torsion angle with the distal phenyl ring. This led to a 50-fold increase in potency and a much improved lipophilic ligand efficiency (LLE)45,46 for CyPr 7, whilst maintaining the physicochemical properties of the series. A close analogue of 7, containing the CyPr, had suitable PK for an in vivo tool.

Morpholine isostere

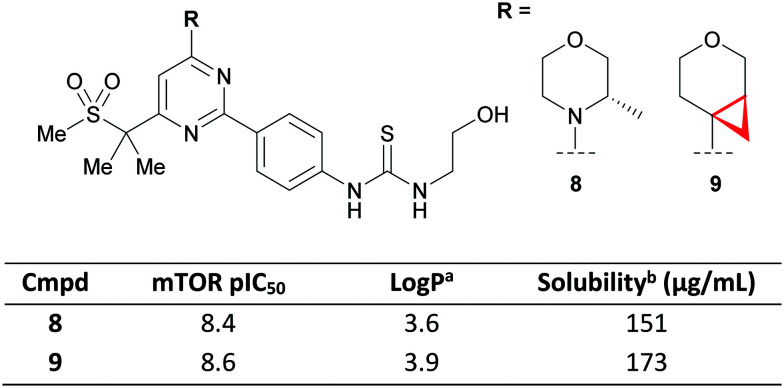

The π-character of the CyPr ring was recently exploited by scientists at GSK to conformationally restrict the free rotation of a tetrahydropyran (THP) ring as an isosteric replacement for morpholines.47 The 4-(pyrimidin-4-yl)morpholine motif is a privileged structure in targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway that appears in multiple patents and papers.48–50 Crucial to its success is the co-planarity afforded by an overlap of the nitrogen lone-pair and the aromatic system, with the morpholine oxygen acting as a hinge binder by hydrogen bonding to Val882. The authors proposed that a CyPr-THP would maintain the desired co-planarity whilst positioning the oxygen to form the key hydrogen bond. They demonstrated that this could be achieved with compound 9 which maintained potency (pIC50 = 8.6), with no detrimental effect on the physicochemical properties vs. the parent methyl morpholine 8 (Fig. 6). However, it should be noted that raised microsomal and hepatocyte clearance was observed for two additional CyPr-THP exemplars relative to their methyl morpholine matched pair (data not shown).

Fig. 6. CyPr THP as a morpholine isostere in a PI3K–mTOR inhibitor.47aLog P = measured ChromLog P.51bKinetic solubility measured at pH 7.4.

Alkene isostere

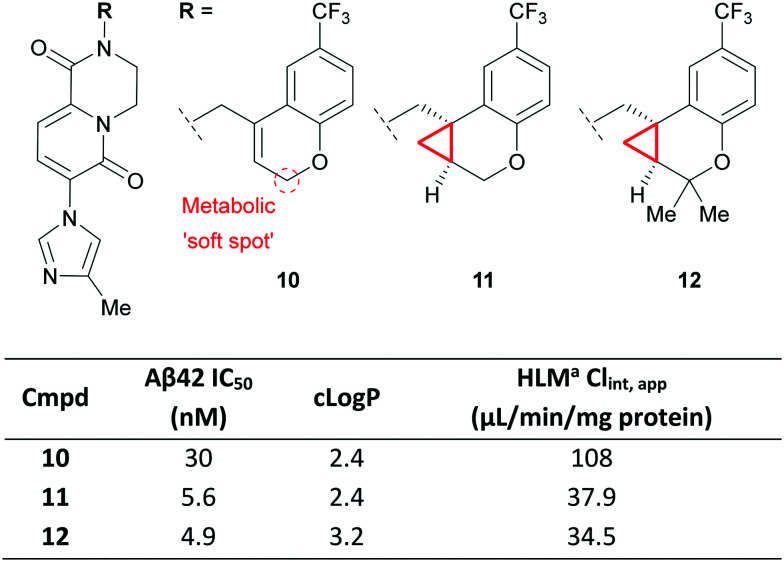

The stabilising effect of the CyPr group was recently used by a group at Pfizer in the development of CyPr-chromane γ-secretase inhibitors as agents that can reduce amyloid plaques (e.g. Aβ42), a pathology implicated in Alzheimer's Disease.52 The authors were initially looking for replacements for a naphthyl group and identified chromene 10 which showed potent reduction of Aβ42 in vitro but suffered from high clearance (Fig. 7). Metabolic identification (MetID) studies showed that this was primarily driven by CYP-mediated oxidation of the methylene between the alkene and chromene O atom. Introduction of the CyPr 11 improved potency through stabilisation of the bioactive conformation, and reduced metabolism through removal of the allylic methylene. Further work identified 12 which gave better brain exposure through increased lipophilicity. This compound displayed excellent tolerability up to 300 mg kg−1 in a rat dose escalation study and showed 40% reduction of brain Aβ42 after 4 hours when dosed orally at 10 mg kg−1.

Fig. 7. Exploration of CyPr as an alkene isostere.52aHuman liver microsomes.

t-Butyl isostere

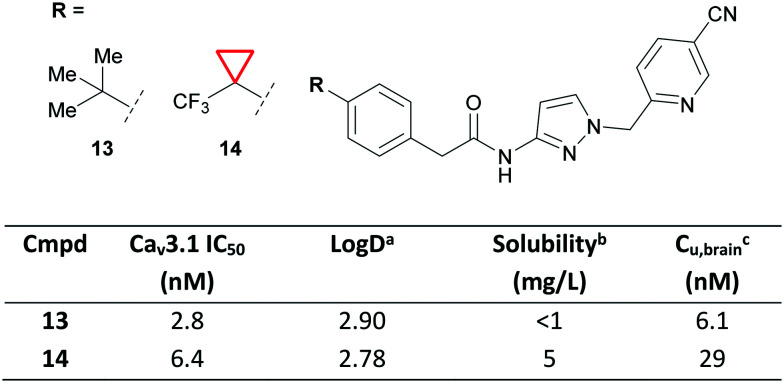

Due to the 3D characteristics of CyPr and the ability to break up crystal packing, CyPr rings are often employed to improve solubility. Recently, a team from Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd reported the development of selective T-type calcium channel (TTCC) blockers for the treatment of epilepsies.53 During their drug discovery program 13 was identified as a potent TTCC blocker, but it was limited by poor solubility and low brain exposure (Fig. 8). The authors showed that switching to a CF3–CyPr (14) improved solubility with little effect on lipophilicity. This was important as previous SAR showed that more polar compounds become P-gp substrates with limited CNS penetration. CyPr 14 was thus identified as a suitable drug candidate to treat epilepsy and has since entered clinical trials.

Fig. 8. Improving the solubility of TTCC blockers using CyPr.53aLog D = AZ log D, calculated Log D at pH 7.4. bSolubility measured at pH 7.0. cUnbound concentration in the brain. Wistar rats were dosed orally with 10 mg kg−1 of 13 and 14.

The CF3–CyPr had previously been reported by researchers at Novartis as a metabolically stable t-Bu isostere.54 In the above example, metabolic stability was good for both 13 and 14 and the authors state that the change was part of the systematic SAR exploration.

Liabilities of cyclopropanes

Cyclopropylamine as a structural alert

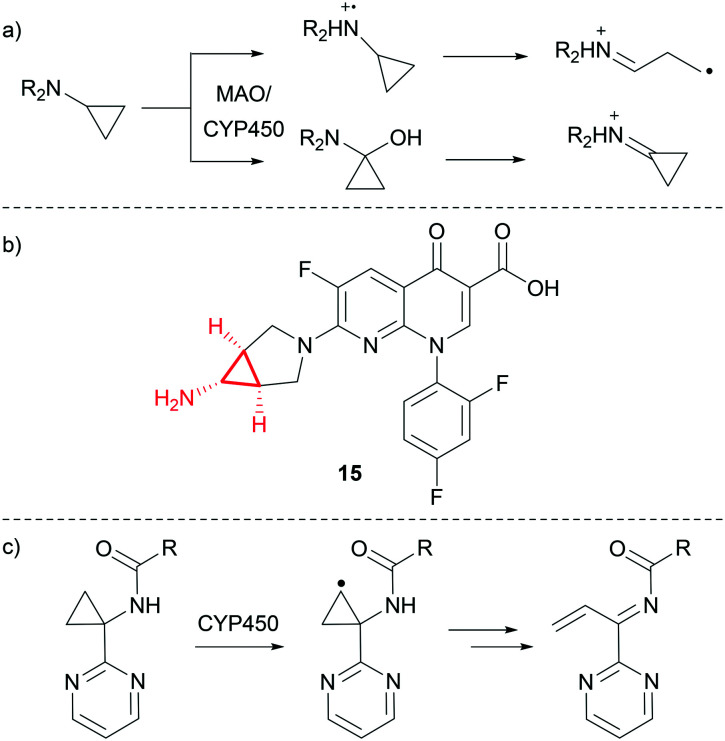

As discussed previously, CyPr groups are often introduced to address metabolic instability of iPr groups. However, cyclopropylamines may be substrates for both monoamine oxidase (MAO) and CYP450 oxidation, which can result in the formation of reactive metabolites.55 The bioactivation is understood to either proceed through single electron transfer from the nitrogen to form a radical cation, which can then undergo ring opening to form a reactive radical and iminium ion, or through hydroxylation of the CyPr carbon adjacent to the amine and subsequent dehydration to form an iminium ion (Fig. 9a).56 Time-dependant inhibition of CYP450s is often observed for compounds with this chemotype as the generated reactive intermediate can inhibit the metabolising enzyme.57,58

Fig. 9. a) Mechanisms of reactive metabolite formation from CyPr amines.56 b) Trovafloxacin.59 c) CYP450-mediated oxidation of a cyclopropylamine β-carbon.60,61.

Trovafloxacin 15 (Fig. 9b) is a broad spectrum antibiotic which was withdrawn from the market due to hepatotoxicity.59 It is believed that oxidation of the cyclopropylamine and subsequent breakdown into a reactive metabolite is the most likely mechanism of action for the observed toxicity, although the exact route of bioactivation is unknown.

In another recent example, researchers at BMS reported a series of Hepatitis C virus NS5B inhibitors where CYP450-mediated oxidation of a cyclopropylamine β-carbon led to the formation of a reactive intermediate (Fig. 9c).60,61 In this case, switching to the gem-dimethyl stopped the formation of reactive intermediates whilst maintaining potency.

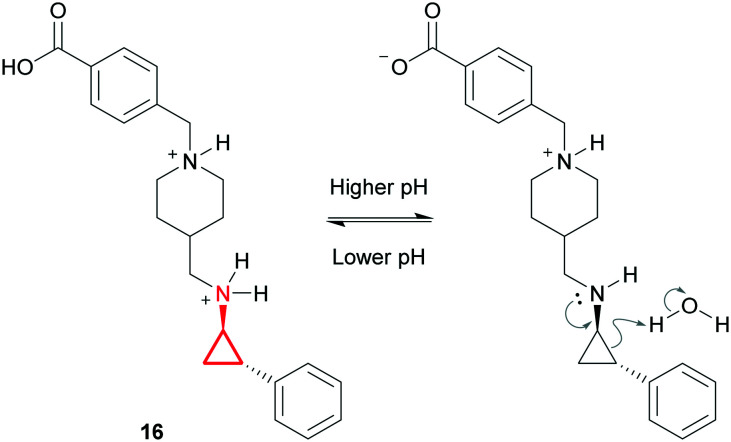

There have also been instances where the chemical stability of cyclopropylamines has been problematic. GSK2879552 (16) is a lysine-specific demethylase inhibitor currently undergoing clinical trials.62 It was revealed that this compound was unstable at high pH and that complete degradation occurred in 0.1 M NaOH after just 2 hours at 80 °C. After a thorough mechanistic study the authors proposed that at higher pH the basic CyPr-amine is uncharged and can react through the nitrogen lone pair via ring opening of the CyPr, leading to chemical degradation (Fig. 10). They claimed that the phenyl ring stabilises the transition state and that the driving force is the release of the strain energy. However, it is not clear why stability is such an issue in this example when the pharmacophore appears in several marketed drugs (e.g. tranylcypromine). Ultimately a stable formulation was identified through careful salt selection. Their strategy was to decrease the solubility of the complex whilst maintaining a saturated aqueous pH <5. This resulted in the identification of a napadisylate (dihydrate) formulation which had suitable stability for development.

Fig. 10. Chemical degradation of GSK2879552 (16).62.

Cyclopropyl carboxylic acid as a structural alert

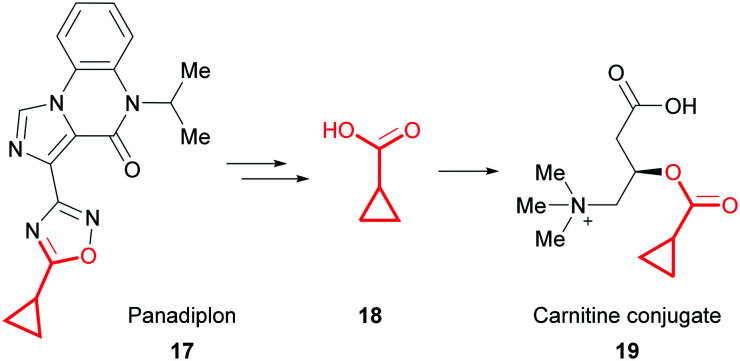

Compounds which contain a fragment capable of forming CyPr carboxylic acid in vivo should also be considered a structural alert because they can form carnitine conjugates.63 Carnitine is a small molecule involved in energy metabolism that transports long-chain fatty acids into mitochondria. Inhibition of this process through the formation of CyPr carnitine conjugates can lead to a toxic build-up of fatty acids or carnitine depletion. A phase 1 trial of the anxiolytic panadiplon (17) was recently paused due to hepatotoxicity.64 It is thought that metabolism generates CyPr carboxylic acid 18 and subsequent conjugation to carnitine conjugate 19 drives the observed toxicity (Fig. 11). Carnitine depletion only presents after chronic treatment with high doses and could potentially be mitigated by taking carnitine supplements. However, during optimisation, MetID studies can be used to identify whether formation of CyPr carboxylic acid is a major metabolic pathway.

Fig. 11. Formation of a CyPr carnitine conjugate from panadiplon (17).64.

Outlook

The CyPr group is a stalwart of medicinal chemistry and its use has arguably become more creative in recent years. Despite potential risks, such as reactive metabolite formation, the CyPr group will continue to be used extensively because of its unique properties and ability to improve potency, provide conformational stability, reduce metabolism and increase solubility.

Cyclobutanes

Introduction

Numerous medicinal chemistry manuscripts now report biologically active cyclobutane (CyBu)-containing compounds with improved activity and properties compared to their acyclic counterparts. In addition, the CyBu motif is recurrent in patents, with consistent application over the past decade (Fig. 2). Furthermore, in the last few decades the use of CyBu derivatives as molecular building blocks in organic synthesis has flourished, and many reliable preparative methods have been reported.65–67 The increased popularity of this cycloalkane ring system in organic synthesis, coupled with its unique structural and physicochemical features has boosted its broad use in medicinal chemistry. To date, 9 FDA-approved drugs containing a CyBu group have been marketed, spanning a wide range of indications.28

Structural features and physicochemical properties of cyclobutanes

In contrast to CyPr, CyBu is not planar but puckered, relieving eclipsing 1,2-interactions: the median puckering angle for CyBu is 15.5° (Fig. 1). In addition, the CyBu median CCC bond angle of 88.9° is a significant deviation from the ideal tetrahedral bond angle for carbon (109.5°), resulting in considerable ring strain compared to its larger homologues cyclopentane and cyclohexane (26, 6 and 0 kcal mol−1 respectively).68 CyBu groups are often used to rigidify linear alkyl chains linking two pendant functionalities; the median C C nonbonding distance of CyBu is 2.16 Å.

Medicinal chemistry applications of cyclobutanes

The CyBu ring system is often employed as a standalone substituent, for example as a mono-substituted pendant group or a 1,1-disubstituted gem-dimethyl isostere to maximise Van der Waals contacts with a target protein. Cis and trans 1,3-disubstituted CyBu rings have use as bridging motifs, restricting free rotation of an aliphatic chain. Such application to increase molecular rigidity has been shown to enhance binding affinity (minimising the entropic penalty of protein–ligand binding) and cellular permeability.69

In light of the small and compact 3-dimensional character of the CyBu group, in combination with its steric and electrostatic properties, incorporation of this carbocyclic small ring into drug molecules can often lead to improved physicochemical and ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion) properties, such as solubility and metabolic stability.70 This section reviews successful medicinal chemistry application of CyBu over the past decade.

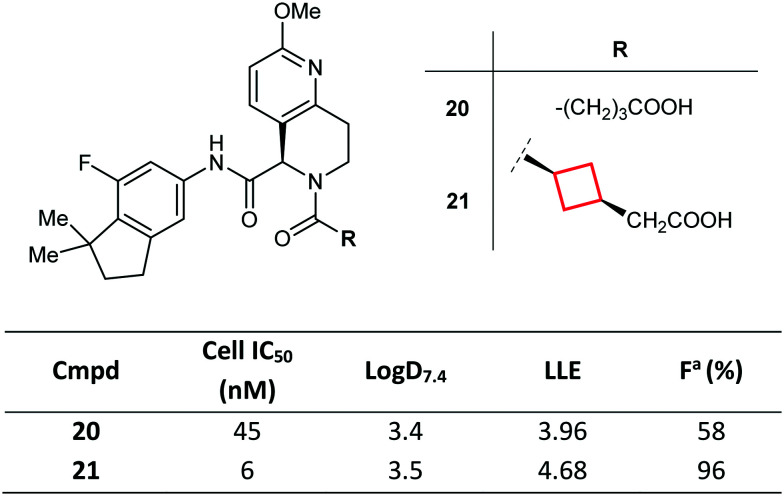

Aliphatic chain restriction (with extension)

CyBu rings can dramatically impact candidate selection, as demonstrated by Kono et al. during the development of novel retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γt (RORγt) inverse agonists.71 Potent RORγt inverse agonistic activity was demonstrated, achieving excellent selectivity against other ROR isoforms and nuclear receptors, as well as a suitable PK profile. Here, the authors introduced a cis 1,3-disubstituted CyBu ring into lead molecule 20 as a replacement to an unconstrained aliphatic linker towards a pendant carboxylate (itself required to modulate PK properties).72 Conformationally constrained molecule 21 was found to have improved potency (by stabilisation of the biologically relevant conformation) and optimal oral bioavailability and plasma exposure (Fig. 12). Of note, the trans-isomer was less potent than cis-isomer 21 (data not shown). On the basis of its potent in vivo efficacy and favourable preclinical PK profile, compound 21 was ultimately selected as a clinical candidate.

Fig. 12. Optimisation of RORγt inverse agonists via conformational rigidification of the acid tether with a CyBu group.71aFraction of dose reaching systemic circulation (bioavailability). Mice were dosed orally with 10 mg kg−1 of 20 and 21.

Aliphatic chain restriction (with contraction)

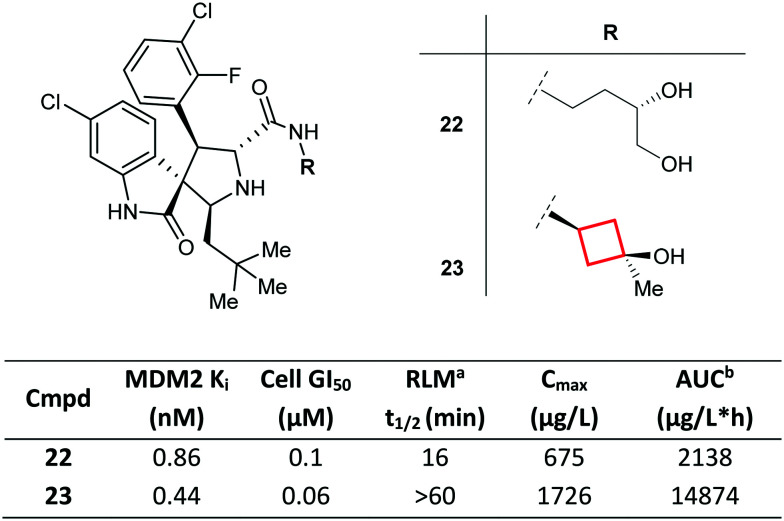

Replacement of a flexible alkyl chain with a rigid, constrained CyBu group may enhance the metabolic stability and PK profiles of molecules, as demonstrated by Zhao et al.73 Compound 22, a previously reported inhibitor of the MDM2 (murine double minute 2 homolog)-p53 interaction, was found to suffer from low metabolic stability, and MetID studies revealed the 1,2-diol side chain as the major metabolic soft spot. By conformationally constraining the carbinol side chain, consequently reducing the number of rotatable bonds in the molecule, the authors were able to identify CyBu 23 (MI-888) as a potent MDM2 inhibitor with improved metabolic stability in rat liver microsomes, superior oral PK profile (in particular, systemic exposure) and enhanced in vivo efficacy compared to 22 (Fig. 13). Remarkably, compound 23 was shown to achieve rapid, complete, and durable tumour regression in two types of tumour xenograft models.

Fig. 13. Optimisation of inhibitors of the MDM2-p53 interaction via conformational rigidification of the carbinol side chain with a CyBu group.73aRat liver microsomes. bArea under the plasma concentration time curve. Rats were dosed orally with 25 mg kg−1 of 22 and 23.

Ring contraction

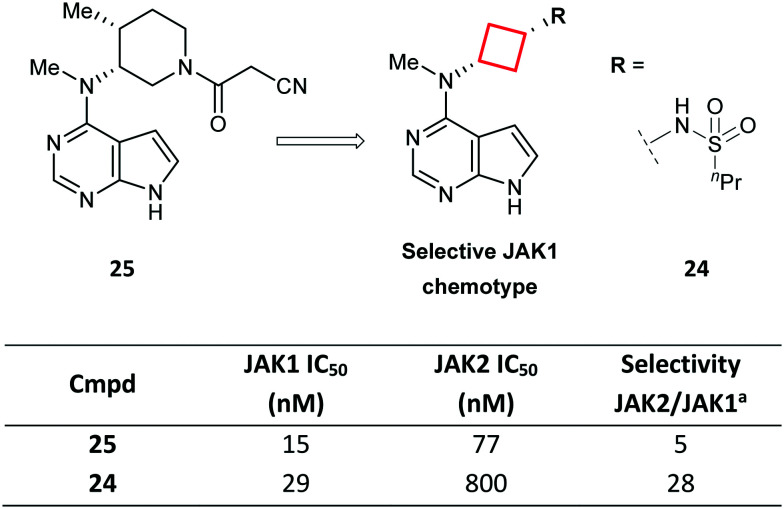

Another example that shows how a CyBu core played a paramount role in the development of a drug candidate is represented by sulfonamide 24 (PF-04965842): a selective JAK1 agent for the treatment of autoimmune diseases, developed from tofacitinib (25; Fig. 14).74 The significant JAK2 activity of tofacitinib may cause haematotoxicity, such as anaemia and thrombocytopenia, thus compounds with a JAK1-selective profile were deemed highly desirable. Replacement of the 3-aminopiperidine in tofacitinib with a cis-1,3-cyclobutyldiamine delivered a JAK1-selective chemotype. In particular, exemplar 24 was found to be a potent and selective JAK1 inhibitor with good physicochemical properties.

Fig. 14. Optimisation of selective JAK1 inhibitors via ring contraction of a piperidyl ring to a CyBu core.74aRatio of IC50 for JAK2 vs. JAK1.

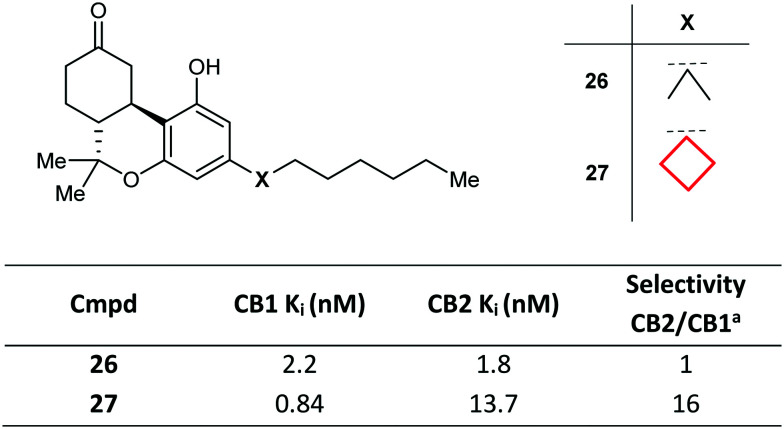

Gem-Dimethyl replacement

The CyBu ring is often used in medicinal chemistry as an isostere of the gem-dimethyl group. In the pursuit of selective cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) agonists, a variety of conformationally modified side chains in tricyclic framework 26 were explored. Whilst gem-dimethyl 26 was unselective vs. CB2, replacement with a CyBu group in 27 led to enhanced potency and a 16-fold selectivity margin (Fig. 15).75

Fig. 15. Development of cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) agonists via gem-dimethyl replacement with a CyBu group.75aRatio of binding affinities for CB2 vs. CB1.

Chain branching

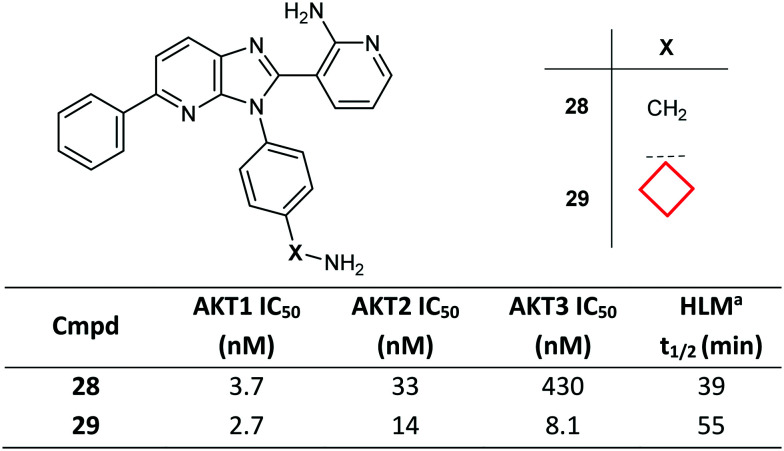

Introduction of a CyBu group may be advantageous in improving stability of metabolically labile aliphatic chains and in improving the overall binding affinity by filling small neighbouring hydrophobic pockets in the target protein. Imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine derivative 28 was optimised to improve both pan-AKT (protein kinase B) activity and the overall profile of the class. The optimisation campaign led to the discovery of CyBu-containing lead molecule ARQ 092 (29), which demonstrated high enzymatic potency against AKT1, AKT2 and AKT3, as well as potent cellular inhibition of AKT activation and the phosphorylation of the downstream target PRAS40 (Fig. 16).76 Compound 29 was also found to have higher metabolic stability in human liver microsomes preparations compared to parent molecule 28. A co-crystal structure of compound 29, bound to full-length AKT1, confirmed the allosteric mode of inhibition of this chemical class and the role in affinity gains of the CyBu group, placed in a hydrophobic cleft.

Fig. 16. Optimisation of AKT inhibitors via side chain branching with a CyBu group.76aHuman liver microsomal stability at 1 μM test compound.

Liabilities associated with cyclobutanes

Metabolism of CyBu substructures

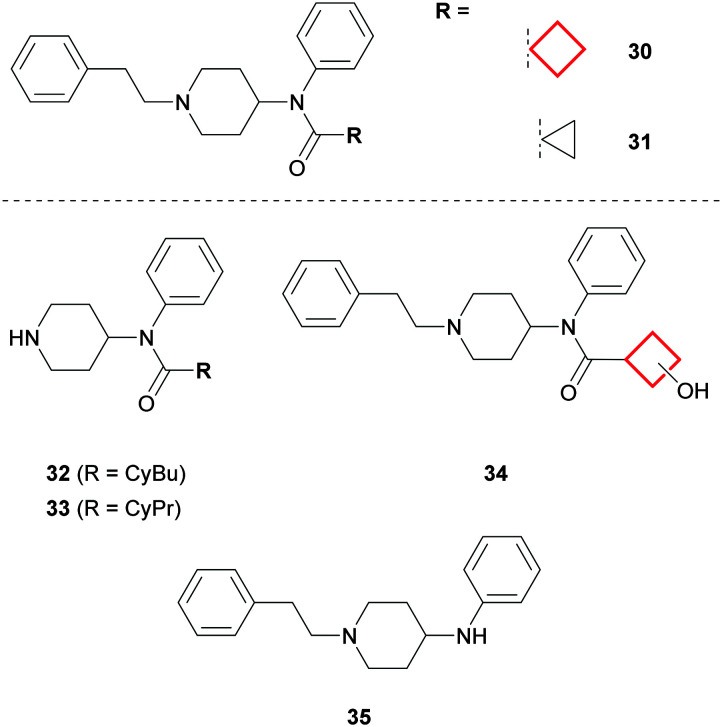

Whilst the CyBu group can be effectively employed to enhance the metabolic profile of drug molecules, success depends on the overall architecture and favourable physicochemical properties of the designed compounds. A CyPr to CyBu switch is a commonplace medicinal chemistry transformation when investigating SAR, often resulting in potency gains if lipophilic contacts are improved. However, Åstrand et al. demonstrated that CyBu-fentanyl 30 was less metabolically stable than the CyPr derivative 31 when incubated with human hepatocytes (Fig. 17). MetID studies revealed that N-dealkylation was the predominant metabolic transformation for both 30 and 31, to give corresponding piperidines 32 and 33. In addition, oxidation of the CyBu ring to give 34 was a major metabolite for 30, whilst oxidation of the CyPr ring in 31 was not observed.77 Interestingly, cleavage of the CyBu amide bond was another significant metabolite for 30 to give 35, whereas the corresponding biotransformation was not observed for CyPr 31. Indeed, it is possible that the resulting CyBu carboxylic acid metabolite may also be capable of forming carnitine conjugates in vivo, as for CyPr acid metabolites (vide supra).63,78

Fig. 17. MetID studies on CyBu-fentanyl (30) and CyPr-fentanyl (31).77.

Synthetic tractability

Whilst developing novel methods towards the syntheses of CyBu rings has gained increasing attention (particularly through photocycloaddition routes,67 or in the context of specific, complex natural products79), CyBu synthetic chemistry still remains largely underdeveloped. In particular, the ability to make select point changes to this ring system presents a large challenge, which has restricting implications for the structure-based and physicochemical property-based design of CyBu-containing molecules in medicinal chemistry.

Outlook

The CyBu ring is an important small ring in the medicinal chemistry toolbox, providing a small lipophilic group to enhance contacts with a target protein, or a structurally rigid scaffold across which to link pendant pharmacophoric features. Despite the relative lipophilic nature of this small ring, incorporation of the CyBu group often leads to improved PK profiles, through enhanced metabolic stability or solubility.

Oxetanes

Introduction

Oxetanes underwent a renaissance in the late 2000s, sparked by interest in their application as liponeutral gem-dimethyl isosteres and replacements for metabolically labile carbonyl functionality. In the following decade, substantial advances towards synthetic approaches80,81 facilitated application of oxetanes in drug discovery projects, leading to an improved appreciation of how this small ring may be leveraged to solve medicinal chemistry problems. Whilst 3-substituted oxetanes are predominant in the medicinal chemistry literature, 2- and poly-substituted oxetanes remain relatively underexplored (beyond taxane derivatives).

Over the past decade, there has been a general increase in the number of drug substance patents exemplifying oxetanes (Fig. 2). Currently, 3 taxane derivatives represent the only marketed drugs containing an oxetane, but a further 28 compounds (9 of which are not taxane-related) are in phase I–III clinical trials.28

Structural features and physicochemical properties of oxetanes

The oxetane moiety is small and polar, occupying an equivalent volume to a gem-dimethyl group82 and possessing a dipole comparable to a carbonyl functionality.83 Oxetanes are relatively flat compared to carbocyclic CyBu rings, as the oxygen atom reduces the number of gauche interactions present:80 the median puckering angle of oxetanes is 7.0° compared to 15.5° for CyBu rings (Fig. 1). The median COC bond angle is 91.3°. Notably, this strained COC bond angle exposes the oxygen lone pairs increasing Lewis basicity, such that oxetanes are excellent hydrogen bond acceptors. Oxetane has the highest hydrogen bonding avidity of the cyclic ethers,84 and exceeds that of aliphatic aldehydes, esters and ketones (but not amides).4

Medicinal chemistry applications of oxetanes

Due to its small size and polar nature, oxetane functionality has gained popularity as a physicochemical property modulating group capable of improving the drug likeness of molecules. In addition, the gauche-directing effect of this small ring (vide infra) has been used to conformationally bias molecules for improved protein interactions. Finally, oxetanes have been proposed and utilised as property-favourable or chemically stable isosteres of multiple functional groups. The following sections describe contemporary application of oxetanes, and reported limitations.

Reducing lipophilicity

Müller et al. demonstrated that replacement of a methylene unit with an oxetanyl moiety at various locations on test substrates consistently led to Log P reductions (∼−0.5 < ΔLog P ≤ −1.5).4 Furthermore, Log P reduction is even more pronounced when replacing structurally similar lipophilic appendages, such as gem-dimethyl, CyPr or CyBu groups.85 In this regard, oxetanes are useful groups for improving lipophilicity-driven negative endpoints, such as diminished aqueous solubility, metabolic instability, off-target promiscuity, hERG and CYP450 inhibition.

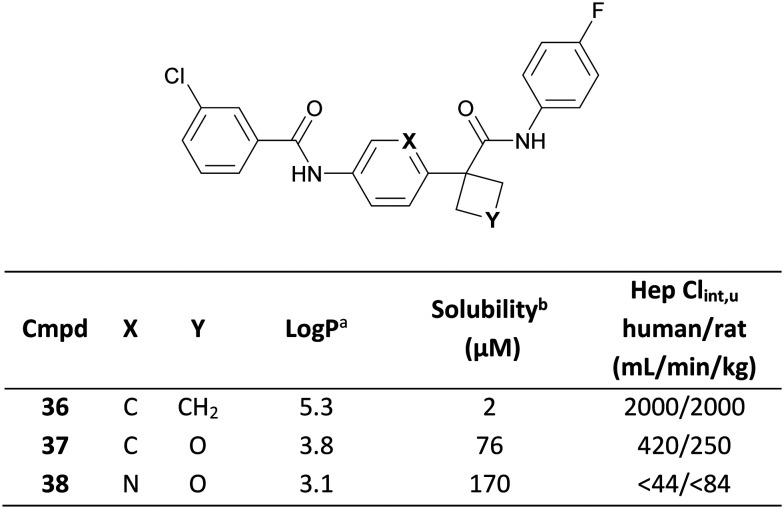

White and co-workers recently demonstrated use of an oxetane moiety to reduce the lipophilicity of a series of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase-1 (IDO1) inhibitors, leading to significantly improved PK parameters.86 CyBu 36 demonstrated high potency, but suffered from limited solubility and extensive metabolism in an in vitro hepatocyte assay, both of which were attributed to excessive lipophilicity (Log P = 5.3).44 Replacement of the CyBu with an oxetane in 37 significantly reduced lipophilicity (1.5 log unit decrease), greatly improving solubility and metabolic stability (Fig. 18) whilst retaining potency. Replacement of the central benzene with a pyridine in 38 led to further physicochemical and ADME improvements, ultimately translating to a low human QD dose prediction of 26 mg for 38.

Fig. 18. Reducing lipophilicity of IDO1 inhibitors through oxetane incorporation.86aLog P = Alog P98.44bFasted state simulated intestinal fluid (FaSSIF) solubility measured at pH 6.5.

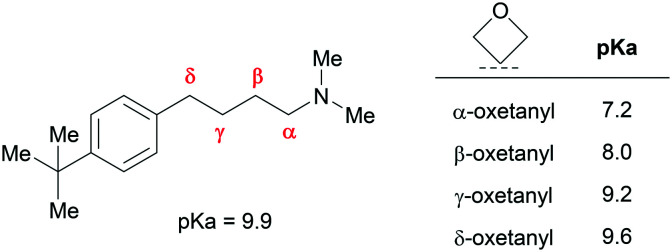

Attenuating amine basicity

Oxetanes can have significant impact on proximal amine basicity as a result of strong σ-electron withdrawing character. This effect is greatest when the oxetane is α relative to an amine, but can extend further: Müller and co-workers demonstrated a 0.3 pKa unit reduction for a δ-aminooxetane relative to the parent alkylamine (Fig. 19).4 Whilst amine pKa reductions may be accompanied by significant Log D increases, in many contexts Log D may be reduced despite attenuated basicity (e.g. replacing a lipophilic group with an oxetane). Lipophilic basic amines are associated with a greater risk of hERG inhibition, phospholipidosis and undesirable PK profiles. Consequently, oxetane installation proximal to an amine represents a strategy to overcome these issues.

Fig. 19. Effect of oxetane introduction on amine pKa for a series of alkylamines.4.

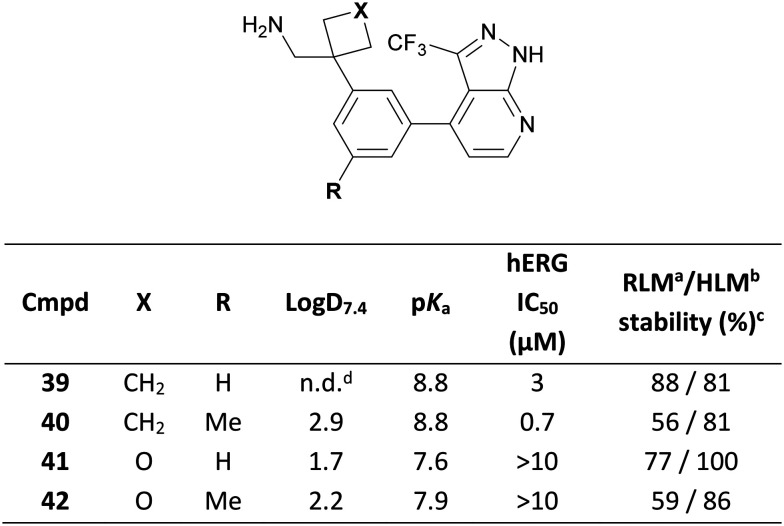

Scientists at Vertex Pharmaceuticals identified cyclobutyl amines e.g.39 and 40 as potent protein kinase Cθ (PKCθ) inhibitors (Fig. 20).87 These compounds however, showed significant hERG inhibition. Judicious replacement of the carbocycle with an oxetane afforded less basic and less lipophilic amines 41–42 with ablated hERG activity and maintained PKCθ inhibition. Furthermore, the oxetanes demonstrated maintained or improved metabolic stability, and improved CYP450 inhibition profiles.

Fig. 20. Reducing hERG inhibition of PKCθ inhibitors through oxetane incorporation.87aRat liver microsomes. bHuman liver microsomes. c% remaining after 30 minutes incubation. dNot determined.

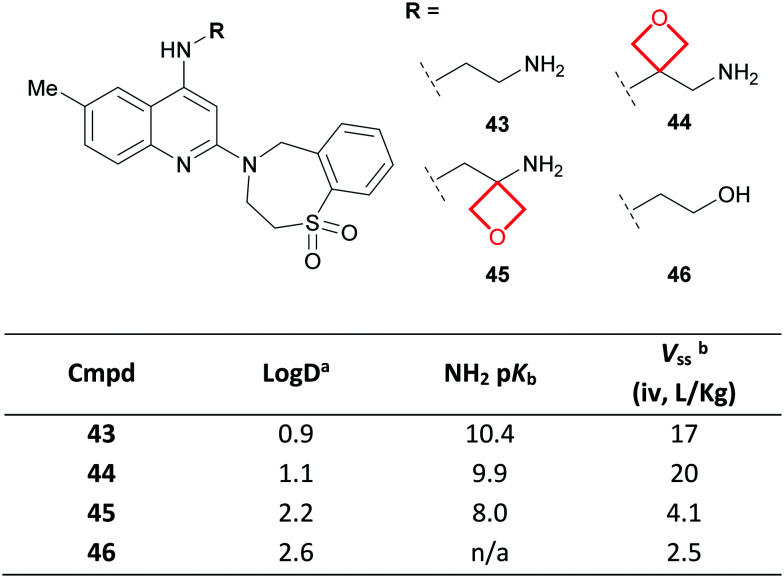

A team at Roche identified a series of respiratory syncytial virus fusion (RSVF) inhibitors reliant on a pendant basic amine for antiviral activity.88 The lipophilic nature of these basic compounds manifested in high volume of distribution values (Vss; e.g. compound 43, Fig. 21), which concerned the authors due to a perceived risk of accumulation and associated toxicity. To overcome this, oxetane inclusion was investigated. Oxetanes 44–45 retained potent activity relative to 43, whilst α-aminooxetane 45 demonstrated reduced amine basicity resulting in a lower Vss, comparable to non-basic alcohol 46.

Fig. 21. Improving the PK of RSVF inhibitors via incorporation of an oxetane.88aLog D = machine learning Log D. bVolume of distribution at steady state.

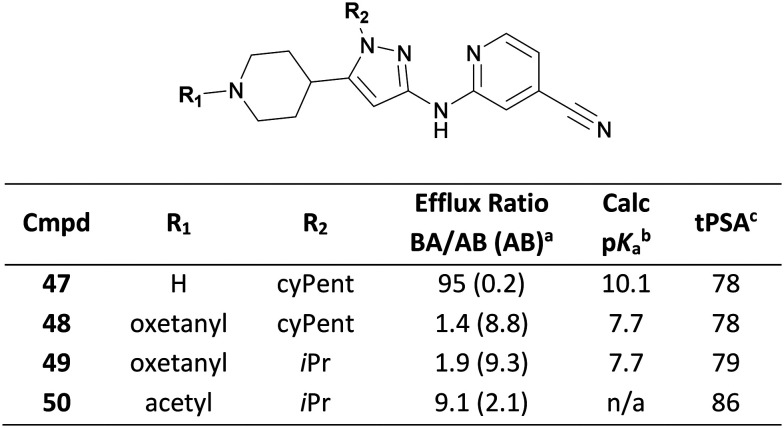

Amine pKa can also impact on efflux transporter recognition. During the development of a series of dual leucine zipper kinase (DLK, MAP3K12) inhibitors, Genentech scientists identified piperidine 47 which demonstrated efflux incommensurate with the desired CNS exposure (Fig. 22).89 Capping the piperidine with an oxetane simultaneously reduced hydrogen bond donor count and amine pKa whilst maintaining topological polar surface area (tPSA), affording 48 and 49 that demonstrated low efflux. Notably, non-basic acetyl 50 showed an insufficient improvement in efflux ratio, likely due to the higher tPSA.

Fig. 22. Improving efflux of DLK, MAP3K12 inhibitors via oxetane incorporation.89aMDCK-MDR1 permeability; AB = apical-to-basolateral; BA = basolateral-to-apical. bPiperidine pKa values were calculated using ACDLabs.90cTopological polar surface area.

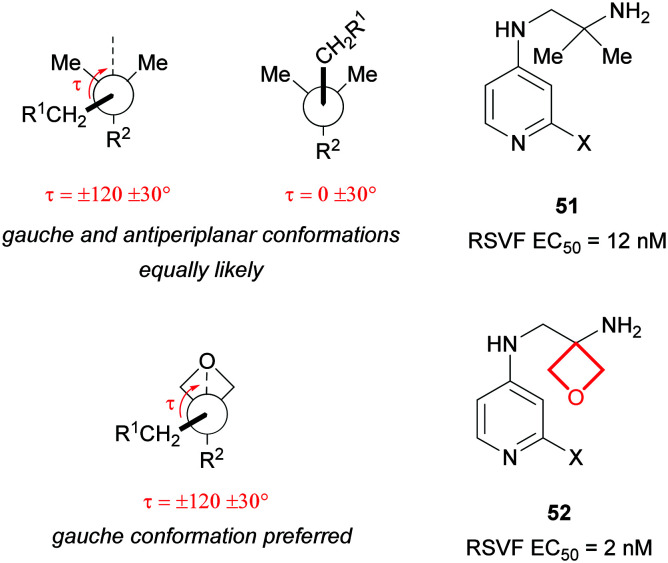

Conformational preferences of oxetanes

A reported analysis of the Cambridge Structural Database revealed the CH2-R1 group α to a 3,3-disubstituted oxetane preferentially adopts a torsional angle of τ = ± 120 ± 30° (a gauche backbone arrangement) in contrast to a gem-dimethyl group which is equally likely to adopt τ = 0 ± 30° (an antiperiplanar conformation; Fig. 23).4 Scientists at Roche working on a series of RSVF inhibitors identified that the potency of gem-dimethylamine 51 could be enhanced through oxetane incorporation.91 Modelling suggested the NH2 interacted favourably with the protein when the alkyl chain adopted a gauche conformation, as predicted more likely for oxetane 52.

Fig. 23. Comparison of conformational preferences of alkyl chains bearing an oxetane vs. a gem-dimethyl group and effect on potency for a matched pair of RSVF inhibitors (X = undisclosed substitution).91.

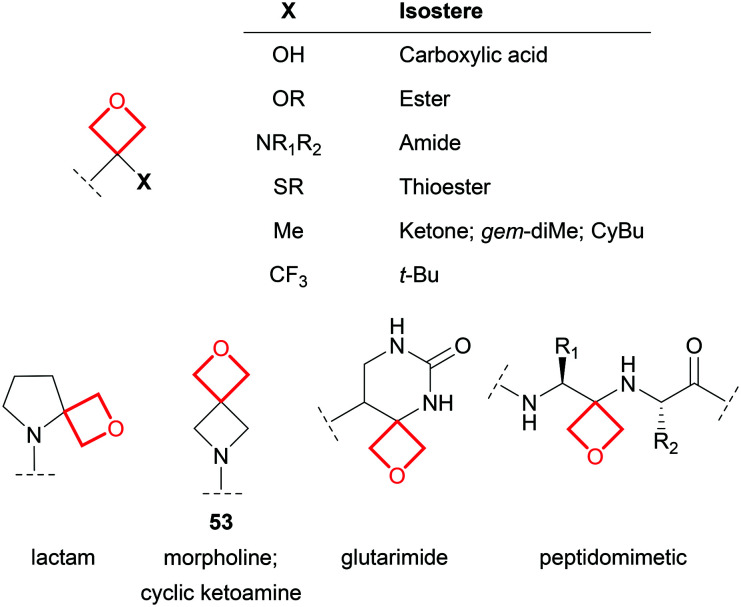

Oxetanes as isosteres

Within drug molecules, carbonyl functional groups can be susceptible to chemical and metabolic instability, and α-stereocenters may be liable to racemisation. Oxetane has a comparable dipole, and similar lone pair spatial orientation and hydrogen bonding capabilities to the C O group. Consequently, oxetane derivatives have been proposed as stable isosteres of ketones,4 esters,92 thioesters,93 carboxylic acids,94 amides,92 cyclic ketoamines and lactams,4 and glutarimides95 (Fig. 24). However, it should be noted that oxetane isosteres differ from their carbonyl counterparts in lateral bulk, non-bonded C O distance, conformational preference and mesomerism. For example, non-hydrolysable oxetanyl peptidomimetics possess the same hydrogen bond donor and acceptor pattern to a peptide,5 but introduce a basic amine and likely assume different low energy conformations to the parent peptide.96

Fig. 24. Examples of proposed oxetanyl isosteres of various functional groups.

Oxetanes have also been proposed as property-enhancing isosteres of the gem-dimethyl group, t-butyl group,54,97 CyPr, CyBu,85 and morpholine.82 Of particular note, homospiromorpholine 53 represents a highly soluble fragment, capable of greatly increasing aqueous solubility above and beyond the morpholine matched pair.4

Liabilities associated with oxetanes

Metabolism of oxetane substructures

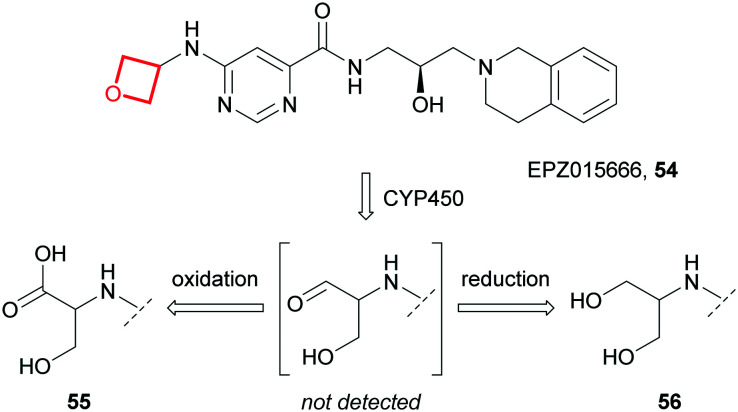

Whilst oxetane incorporation can positively impact physicochemical properties and ADME parameters, the oxetane units themselves may be liable to metabolic biotransformation, depending on overall chemical context of the molecule. For example, Rioux and co-workers showed the major metabolites of the first-in-class protein arginine methyltransferase-5 (PRMT5) inhibitor EPZ015666 (54) were hydroxypropionic acid 55 and diol 56, formed via CYP450-mediated oxidative scission of the oxetane followed by oxidation or reduction of the intermediate aldehyde (Fig. 25).187

Fig. 25. The major metabolites of EPZ015666 (54), formed via CYP450-mediated oxidation of the oxetane ring.187.

In addition to turnover via redox pathways, oxetane-containing molecules may be substrates of liver microsomal epoxide hydrolase (mEH),98,99 forming a diol metabolite via hydrolysis (akin to 56). Toselli et al. demonstrated that spirocyclic, bridged bicyclic and straight chain oxetanes can be turned over by mEH.100 The authors noted no correlation between extent of hydrolysis by mEH and physicochemical properties (Log D, pKa, LUMO energy), whilst minor structural changes had significant impact (Fig. 26), implicating global structural recognition as a key factor for susceptibility to mEH turnover. It was suggested that oxetanes may provide handles to reduce dependency on CYP450-mediated clearance to minimise risk of drug–drug interactions, although PK predictions would likely present a challenge.

Fig. 26. Subtle structural changes can influence mEH recognition.100.

Hydrolytic instability of oxetanes

Although substantially less reactive than the smaller homologue epoxide, the ring strain (25.3 kcal mol−1)80 and Lewis basicity associated with oxetanes render this small ring prone to acid-catalysed ring opening. Indeed, this makes oxetanes useful synthetic intermediates.80 This instability to protic conditions however, can be problematic in the context of medicinal chemistry applications. For example, in one study a range of 3-monosubstituted oxetanes showed limited stability in acidic aqueous media.4 However, it should be noted that this liability is entirely context specific and should be assessed for different oxetanes; in the same study, 3,3-disubstituted oxetanes were found to be much more stable, fully recoverable after 2 hours from buffered aqueous solutions over the pH range 1–10 at 37 °C.

Outlook

The oxetane ring has become an established part of the medicinal chemistry toolbox, with applications focussing on property enhancement owing to its small and polar nature. Whilst reported applications predominantly utilise 3-substituted oxetanes, judicious incorporation of 2- and poly-substituted oxetanes remains underexplored. This imbalance may shift as novel, simplified synthetic approaches to more elaborate oxetane motifs are developed.

Azetidines

Introduction

Azetidines are polar, rigid 4-membered rings distinct to their neutral small ring congeners because of their basic nitrogen atom.101,102 Despite the prevalence of the larger cyclic amine homologues pyrrolidine and piperidine,103 azetidines feature in only 9 approved drugs28 which is undoubtedly due in part to their challenging synthesis.104 Nevertheless, an increasing number of synthetic methods to form and append azetidines to molecules104–106 has given them significant prominence in drug discovery in recent years (Fig. 2).

Structural features and physicochemical properties of azetidines

Azetidines share similar median bond lengths and angles to CyBu rings, with the exception of the CNC bond angle when the nitrogen is sp2 hybridised (Fig. 1). The median puckering angle of azetidines with sp3 hybridised nitrogens (15.3°) is similar to that of CyBu (15.5°) and expectedly, significantly larger than for the flatter sp2 analogues (6.4°). Furthermore, the calculated ring strain of azetidine is much larger than that of piperidine (25.2 vs. 0 kcal mol−1 respectively)107,108 and pyramidal inversion of the nitrogen is facile at room temperature (ΔG≠ = 10 kcal mol−1 for N-methyl azetidine in the liquid phase).109 Finally, in aqueous solution at 25 °C, the pKa of azetidine (11.29) is similar to pyrrolidine (11.27) and piperidine (11.22), yet distinct to that of aziridine (8.04).23

Medicinal chemistry applications of azetidines

The small size, polarity, high Fsp3 character, basicity and rigidity of azetidines can often improve the global properties of molecules, e.g. lipophilicity, solubility, in vitro metabolism and PK. Notably, azetidines have found particular prominence as replacements for numerous functionalities including pyrazine,110 piperidine,111–113 pyrrolidine,114 diazepane,115 β-lactam,116 pyrrolidinone,117 piperazine,118 CyPr,119 and proline.120 In this section, recent noteworthy applications of azetidines have been captured, as well as examples of reported liabilities.

Reducing lipophilicity

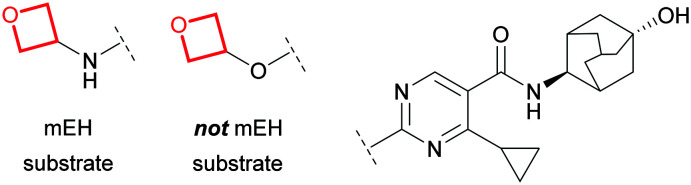

The symmetric nature of 1,3-substituted azetidines make them viable replacements for 1,4-substituted piperidines. A team at AstraZeneca recently reported the discovery of a melanin concentrating hormone receptor 1 (MCHr1) antagonist 57 with markedly lower lipophilicity compared to previously reported antagonists (Fig. 27).111 Aiming to further reduce lipophilicity whilst maintaining the favourable CNS properties of 57, the team proposed an azetidine replacement for the piperidine core (58). It was postulated that this could project the key pharmacophoric features in similar positions to the putative bioactive conformation of piperidine-containing agonists such as 57. Indeed, this transformation resulted in an overall increase in LLE, with Caco-2 permeability and efflux only marginally affected (57vs.58). Despite the reduction in Log D, hERG inhibition remained a concern. Nevertheless, this reduction enabled the broader scoping of SAR on the periphery of 58. This culminated in the discovery of AZD1979 (59), where in fact the azetidine-containing 2-oxa-6-azaspiro[3.3]heptane replacement of the pyrrolidine provided the desired wider selectivity margin over hERG inhibition. This change led to a decrease in pKa (from 9.9 to 8.2 for 58 and 59 respectively) which likely contributed to the reduced hERG activity, despite a slight increase in Log D.111

Fig. 27. Discovery of azetidine-containing MCHr1 antagonist AZD1979 (59).111aFunctional [35S]GTPγS assay developed for MCHr1. bCaco-2 permeability; AB = apical-to-basolateral; ER = efflux ratio.

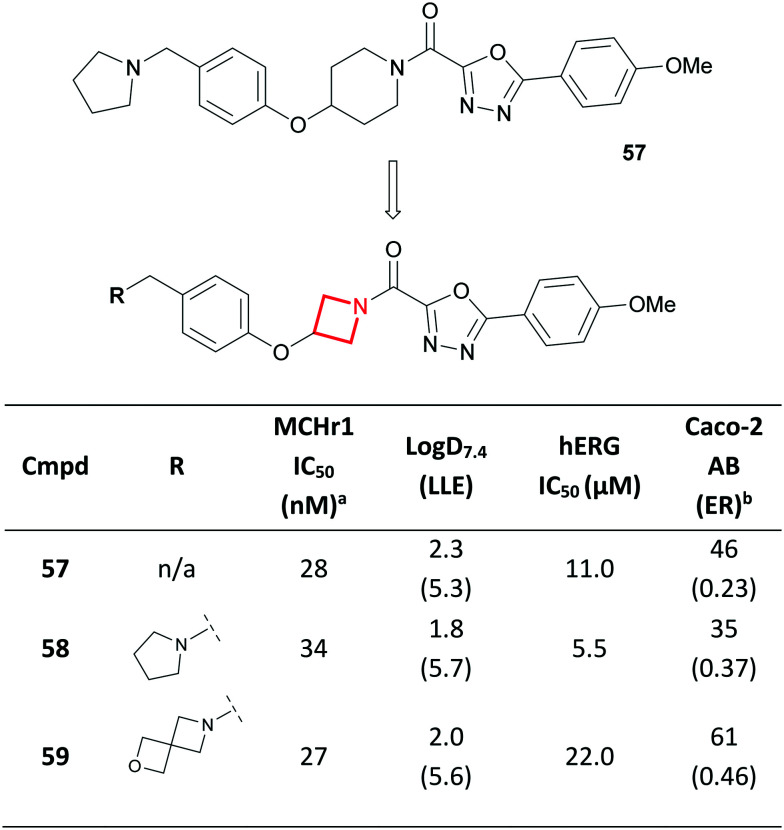

A similar ring contraction strategy was reported by scientists at Janssen and Hutchinson MediPharma, who demonstrated that the 1,2-substituted pyrrolidine core of a series of selective PI3Kγ/δ dual inhibitors (e.g.60) could be replaced with a 1,2-disubstituted azetidine (e.g.61), leading to reduced lipophilicity and improved microsomal stability (Fig. 28).114 Modification of the pyrimidine substitution of 61 afforded the highly potent and kinome-selective 62, a promising pre-clinical candidate that demonstrated desirable PK properties and good efficacy in an in vivo arthritis model.

Fig. 28. Replacement of the 1,2-disubstituted pyrrolidine core of a series of PI3Kγ/δ dual inhibitors with an azetidine.114aLog D = AZ log D, calculated Log D at pH 7.4. bRat liver microsomes. cHuman liver microsomes. d% remaining after 30 minutes incubation. eNot determined.

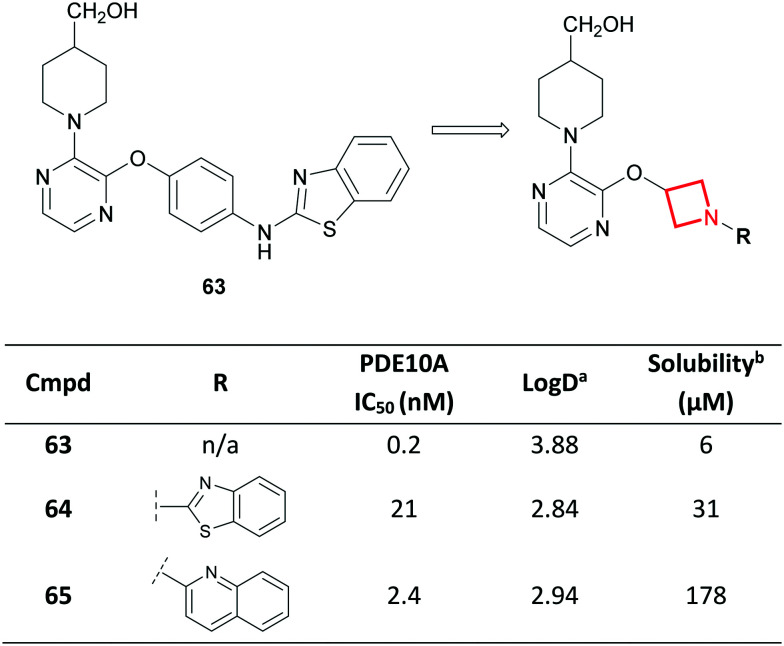

Solubility enhancement

Azetidines have also been used to replace unsaturated ring systems.110 Towards the discovery of potent and selective phosphodiesterase 10A (PDE10A) inhibitors for the treatment of schizophrenia,121 scientists at Amgen noted that the low aqueous solubility of inhibitor 63 (ref. 122) could prove challenging to its further development (Fig. 29). This was attributed to a high degree of aromaticity, known to limit aqueous solubility.1,9,10 As a result, saturated heterocycles were proposed as replacements to the central aromatic ring. Molecular modelling assisted in concluding that an azetidine replacement may be tolerated. Despite a 100-fold loss in potency for azetidine 64, the authors were satisfied with the 5-fold improvement in solubility. Further optimisation culminated in a novel series of soluble and potent PDE10A inhibitors (e.g.65) demonstrating >1000-fold selectivity over other PDEs.121,123 In parallel to increasing the Fsp3 character of the inhibitors, the azetidine ring contributes to a predicted reduction in Log D, which would be conducive to increasing solubility.

Fig. 29. Solubility enhancements in Amgen's PDE10A inhibitor drug discovery program.121,123aLog D = AZ log D, calculated Log D at pH 7.4. bAqueous solubility measured at pH 7.4 using a phosphate buffered saline solubility assay.

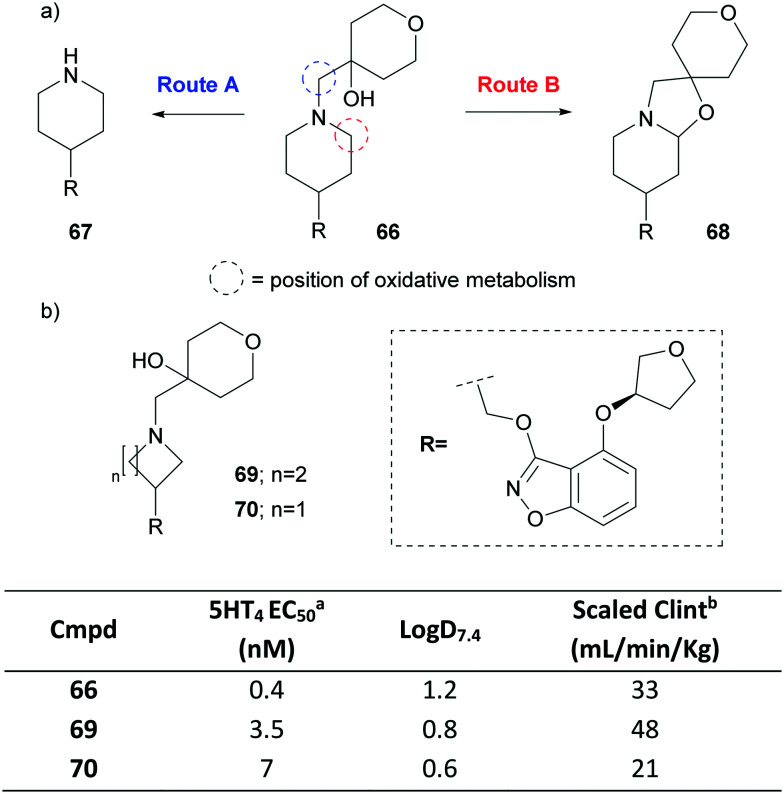

Shifting metabolism

Scientists at Pfizer recently disclosed a partial agonist of the human 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4 (5-HT4), PF-04995274 (66).113 After dosing volunteers with 66, metabolites 67 and 68 were detected in pooled plasma (Fig. 30a). In fact, 68 was found in higher abundance than the parent drug, despite only being a minor component in in vitro experiments.113,124 Compound 67 is believed to be formed via an oxidative dealkylation (route A), whereas 68 is generated via the intramolecular trapping of an oxidatively formed iminium species (route B).125 Concerns around the off-target pharmacology of the metabolites led to the exploration of replacements of the piperidine. A pyrrolidine variant 69 generated the two analogous metabolites whereas azetidine 70 showed neither (Fig. 30b). Interestingly, for the latter, a metabolic shift was observed where hydroxylation of the benzisoxazole ring became the predominant metabolic route. This shift was attributed to the higher calculated energy barrier for abstraction of the hydrogen on the α-carbons to the azetidine nitrogen compared to that of the larger azacycles. The replacement also resulted in a drop in Log D, reduced intrinsic CYP450-mediated turnover and thus a lowering of the predicted human intrinsic clearance, all whilst retaining functional potency.

Fig. 30. a) Metabolites observed in pooled human plasma for PF-04995274 (66). b) Optimisation of the 5-HT4 partial agonist.125acAMP HTRF agonist assay. bHuman liver microsomes scaled to the whole liver using physiological parameters (not corrected for incubational binding).

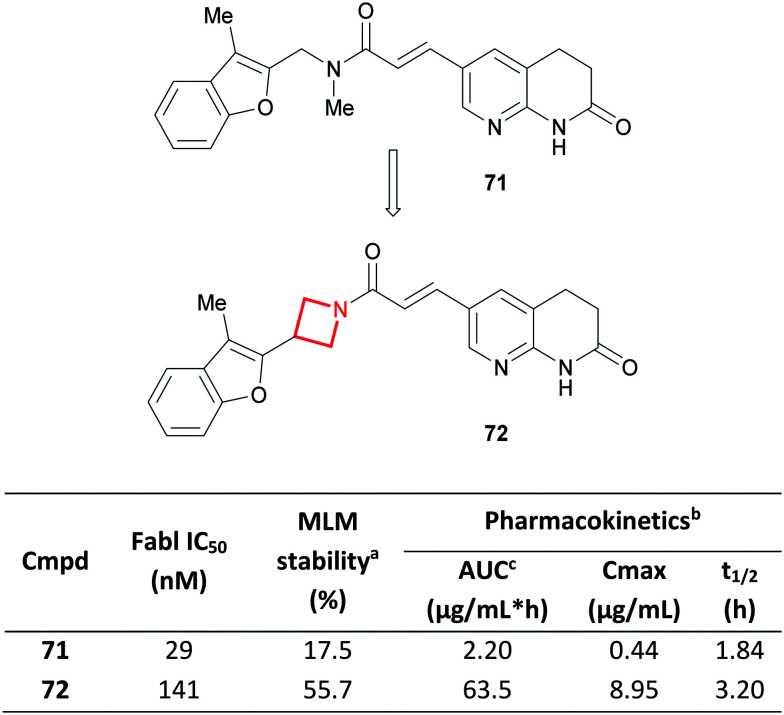

Reducing metabolism

Like CyBu rings, azetidines have also been used to constrain linkers, particularly in the field of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 agonists, as β-alanine126 and γ-aminobutyric acid127,128 replacements. In a related case-study, scientists at Aurigene replaced a linear tertiary amide in the enoyl-[acyl carrier protein] reductase (Fabl) inhibitor AFN-1252 (ref. 129) (71) with an azetidine amide (72) (Fig. 31).130 Despite the introduction of an extra carbon, a significant improvement in stability towards mouse liver microsomes was observed, translating to an improved mouse PK profile.131 This was credited to the cyclic and conformationally restricted azetidine amide which was claimed to be more resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis than the linear analogue. The azetidine in 72 likely also benefits from a relatively higher energy barrier for oxidative N-dealkylation,113 although this was not discussed in the report. Comparable activity for FabI was reported, coupled with good cellular activity and in vivo efficacy in a murine systemic infection model.

Fig. 31. Conformational restriction of Fabl inhibitors and their effect on in vitro metabolism and in vivo PK.130aIn vitro metabolism study in mouse liver microsomes; value indicates % of compound remaining after a 60 min incubation. bSingle dose in mice (P.O., 10 mg kg−1). cArea under plasma concentration time curve.

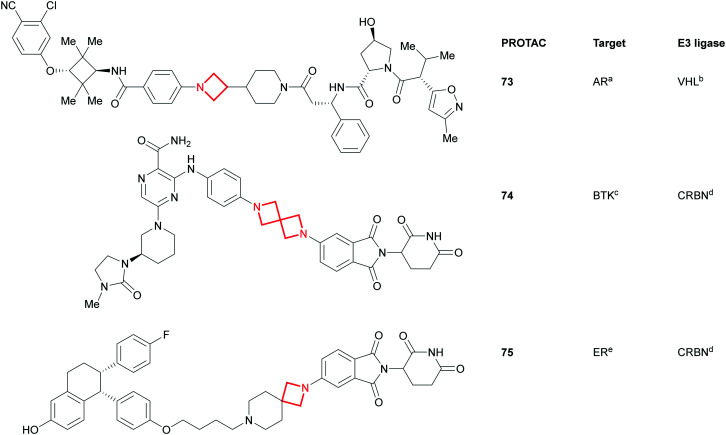

Linkers in the beyond-rule-of-5 (BRo5) chemical space

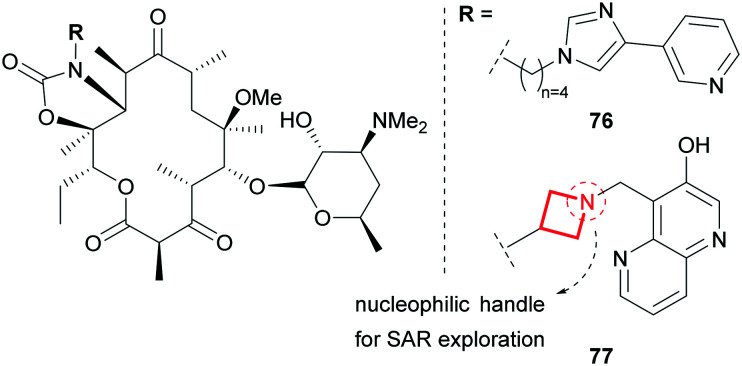

Alongside azetidines, the more elaborate azetidine-containing spirocycles (Fig. 32) have tremendous capacity in modulating the overall properties of molecules.132–134 This, combined with their rigidity, aptness for exploration of 3D space80 and also their versatility as reagents, makes these azetidine substructures ideal for implementing in proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) drug discovery programs.135,136 PROTACs tend to occupy the BRo5 chemical space where oral absorption constitutes a significant challenge. The linker in these bifunctional molecules has been recognised as one of the key design features as it: a) needs to connect and project the target protein and E3 ligase ligands in a fashion conducive for degradation and b) can significantly modulate the global physicochemical properties. In the advent of this modality, it is interesting to see that amongst others, azetidines and spiro-azetidines appear to play an important part in the sampling of chemical space as can be seen from examples taken from recent publications137,138 and patent filings (e.g.73;13774;13975;140Fig. 32).

Fig. 32. Azetidine- and spiroazetidine-containing PROTACs. PROTACs are aligned with the target binding ligand, linker and E3 ligase binding ligand from left to right. aAndrogen receptor; bVon-Hippel Lindau; cBruton's tyrosine kinase; dcereblon; e estrogen receptor.

Similarly, azetidines have also been used as tethers to ketolides in the search for novel broad spectrum antibiotics. One of the key features of telithromycin (76), responsible for its efficacy in erythromycin resistant strains, is the alkyl–aryl tether of the ketolide scaffold (Fig. 33).141 Aiming to develop an antibiotic which matches the efficacy of 76, yet is devoid of its reported hepatotoxicity,142 scientists at Pfizer replaced the alkyl tether with an azetidine functionality.143 This rigid ring constrains the tether and modulates the global properties of the molecule by introducing polarity and basicity. The nucleophilic handle off the ketolide also facilitated the broad exploration of SAR of the pendant group resulting in the clinical candidate 77 which has an improved metabolic and safety profile compared to 76.

Fig. 33. Azetidine as a tether in the optimisation of ketolide antibiotics.143.

Liabilities associated with azetidines

Chemical stability

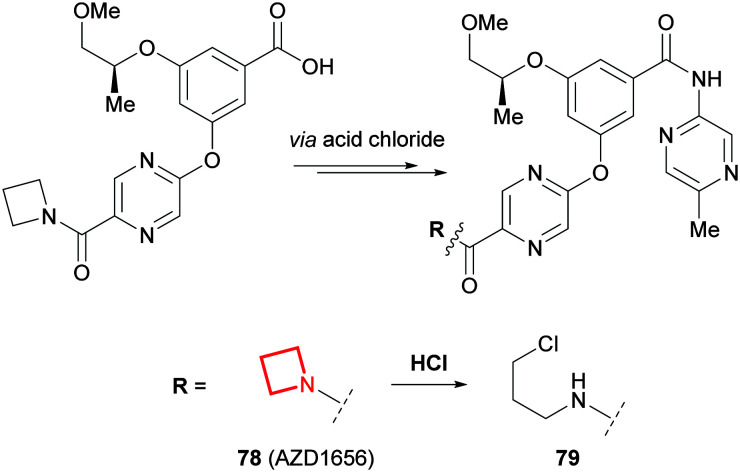

Similar to aziridines, azetidines can undergo ring opening reactions,104,105 albeit at a much slower rate.144 During the scale-up of the glucokinase activator AZD1656 (78), scientists at AstraZeneca noted that 79 was formed alongside 78 on the final amide coupling step (Fig. 34).145 It was concluded that the HCl by-product of the reaction led to the activation and subsequent ring opening of the azetidine in 78. A mitigation strategy employed a pyridine scavenger in the reaction, which was removed using sulfuric acid instead of HCl during aqueous work-up, to avoid the formation of 79. Similar intermolecular ring openings have been reported for azetidine hydrochloride salts which can dimerise upon standing.146,147

Fig. 34. Hydrochloric acid promoted ring opening of the azetidine in AZD1656 (78).145.

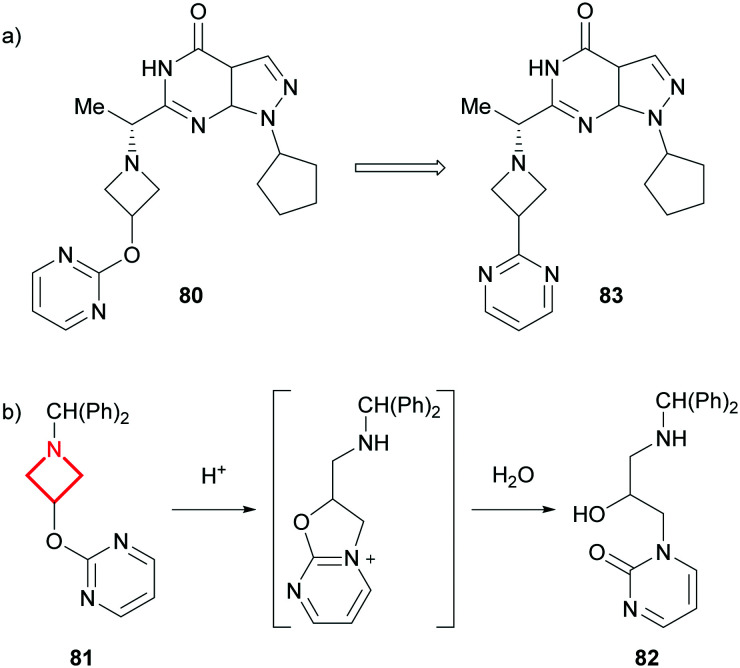

A related ring opening was observed by scientists at Pfizer who noted a significant chemical instability of their PDE9A inhibitor 80 in acidic and neutral media (Fig. 35a).148 After performing analytical investigations on a model system (81) in aqueous HCl, the team concluded that the pendant pyrimidine participates in an intramolecular ring opening of the azetidine, resulting in the formation of 82 following the addition of water (Fig. 35b). Optimisation of the series focussed on distorting the trajectory of the pyrimidine intramolecular attack. Lead compound 83, which lacks the oxygen linker to the pyrimidine, showed improved stability with no decomposition observed after 10 hours at pH <2.

Fig. 35. a) Overall modification of the PDE9A inhibitor 80. b) Intramolecular ring opening of the azetidine-containing model system (81).148.

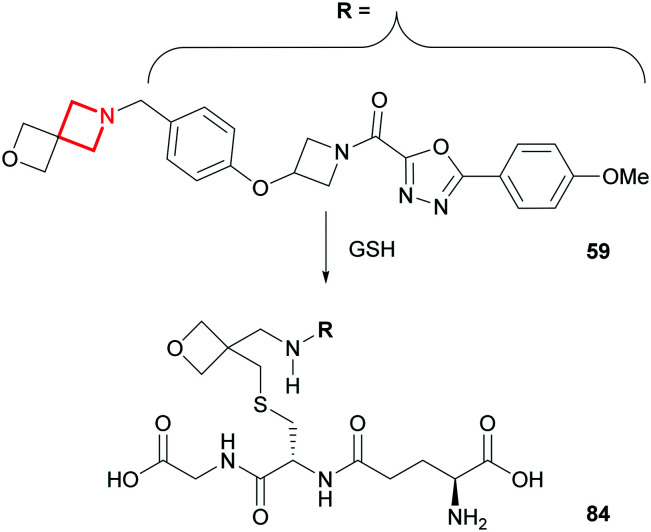

GSH reactivity

Metabolite identification studies of the aforementioned AZD1979 (59) in human hepatocytes revealed an unusual glutathione (GSH) ring opening of the spiro-azetidine (Fig. 36).149 This is a glutathione transferase-catalysed transformation and does not occur in the absence of this enzyme, nor is it a result of any prior bioactivation catalysed by CYP450s. Fortunately, the GSH-conjugated metabolite (84) was not a toxicological concern towards the advancement of AZD1979 into clinical development.

Fig. 36. Glutathione transferase catalysed metabolism of AZD1979 (59).149.

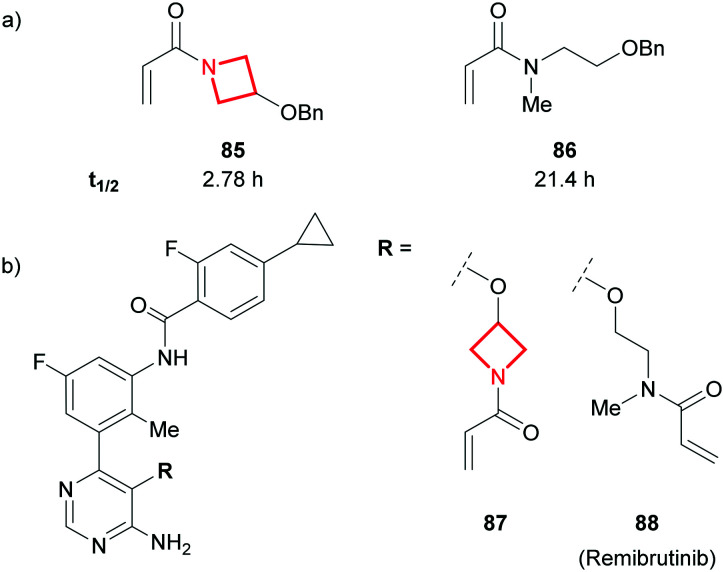

N-Acryloyl azetidines have been explored in programs where covalent inhibition of a target is the desired mechanism of action.150,151 In such programs, the reactivity of the electrophile needs to be fine-tuned to enable potent and selective inhibition of the target, whilst evading any significant GSH-induced metabolism.152,153 Remarking on the rarity of N-acryloyl azetidines in drug discovery, scientists at Eli Lilly assessed the susceptibility of these electrophiles to GSH conjugation in phosphate buffer. A significantly higher reactivity compared to their open chain analogues was reported (e.g.85vs..86, Fig. 37a).154 This was attributed to the reduced amide character of N-acylazetidines, caused by non-planarity, and thus a higher electrophilicity of the conjugated double-bond.154,155 A team at Novartis recently reported the low plasma stability of the Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor 87 which was credited to the aforementioned reactivity.156 This was deprioritised in favour of the open-chain variant which is found in remibrutinib (88; Fig. 37b).

Fig. 37. a) Half-life (t1/2) measurement at 0.1–1 mM of acrylamide, 10 mM glutathione, 70 mM phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4), 30% MeCN at 37 °C.154 b) Novartis' acrylamide BTK covalent inhibitors.156.

Outlook

Azetidines represent the smallest stable azacycle used in medicinal chemistry. Like many functional groups, azetidines can carry certain liabilities worth interrogating. However, their unique characteristics can impart significant benefits to the global properties of molecules. This, coupled with the ease of functionalisation on the nitrogen atom, make them particularly valuable scaffolds in drug discovery programs.

Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes

Introduction

The bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane (BCP) motif is the smallest of the bridged aliphatic ring systems and has gained prevalence within medicinal chemistry predominantly for its application as a saturated benzene isostere. Despite the first instance of its successful bioisosterism in 1996,157 the BCP moiety has yet to appear in any approved drug scaffolds, although it has appeared in an increasing number of patents over the past decade (Fig. 2), likely in part due to recent advances in efficient BCP synthesis.158–166 The use of the BCP motif as an alkyne isostere167 or a t-Bu isostere3,168 has been less thoroughly explored.

Structural features and physicochemical properties of bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes

The BCP ring system has largely been employed to improve physicochemical and PK properties relative to phenyl analogues. BCPs have a median non-bonded C C distance of 1.87 Å and an approximately linear substitution vector arrangement: the median carbon bridgehead substituent angle is 178.4° (Fig. 1). While the BCP ring positions opposite substituents in a near-linear fashion, mimicking that of a para-substituted benzene, the BCP presents a shorter non-bonded C C distance relative to its phenyl counterpart (2.79 Å for benzene).169 As a result of its rigid 3D character, replacement of phenyl with a bridged BCP ring increases Fsp,3 consequently disrupting planarity, limiting intermolecular π-stacking and likely imparting improvements in solubility. Generally, a reduction in lipophilicity can also be observed for BCP-analogues relative to phenyl rings. Benefits of reduced lipophilicity include a reduced likelihood of non-specific binding and generally lower metabolic clearance of resulting compounds.

Medicinal chemistry applications of bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes

Due to its rigid 3D character and linear positioning of its substituents, the BCP ring system is becoming a more prominent motif capable of modulating physicochemical properties in pharmaceutical compounds, resulting in an increasing occurrence in medicinal chemistry design strategies.

Phenyl bioisostere

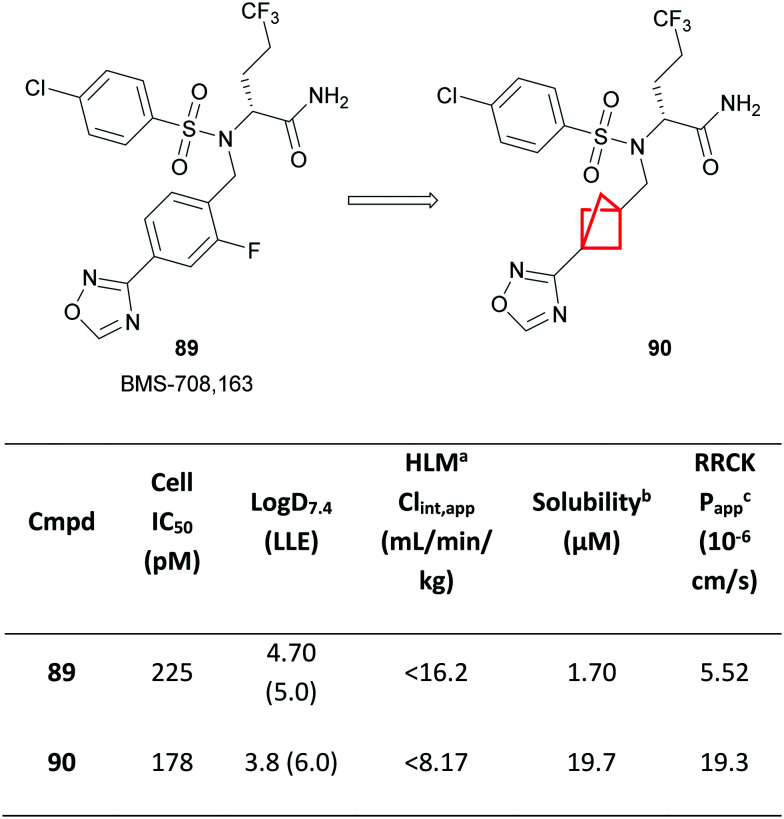

An early example of the application of BCP as a phenyl isostere was demonstrated by Stepan and colleagues from Pfizer, in which a fluorophenyl group in the known γ-secretase inhibitor 89 was replaced with a BCP ring in 90 (Fig. 38).170

Fig. 38. Optimisation of a γ-secretase inhibitor.170aHuman liver microsomes; Clint,app = total apparent intrinsic clearance from scaling in vitro t1/2 in HLM. bThermodynamic solubility measured at pH 6.5. cApparent permeability coefficient in Ralph Russ canine kidney (RRCK) cells with low transporter activity.

A significant increase in solubility was observed, attributed to the increased Fsp3 character, as well as a substantial reduction in lipophilicity. Compound 90 also remained equipotent to 89, affording a higher LLE, and confirming that the shorter interbridgehead distance of the BCP was well tolerated within the binding pocket. Improved metabolic stability was observed, likely as a result of the reduction in Log D, as well as improved intrinsic permeability. Compound 90 was also outside of the scope of the patent of the original γ-secretase inhibitor 89.171

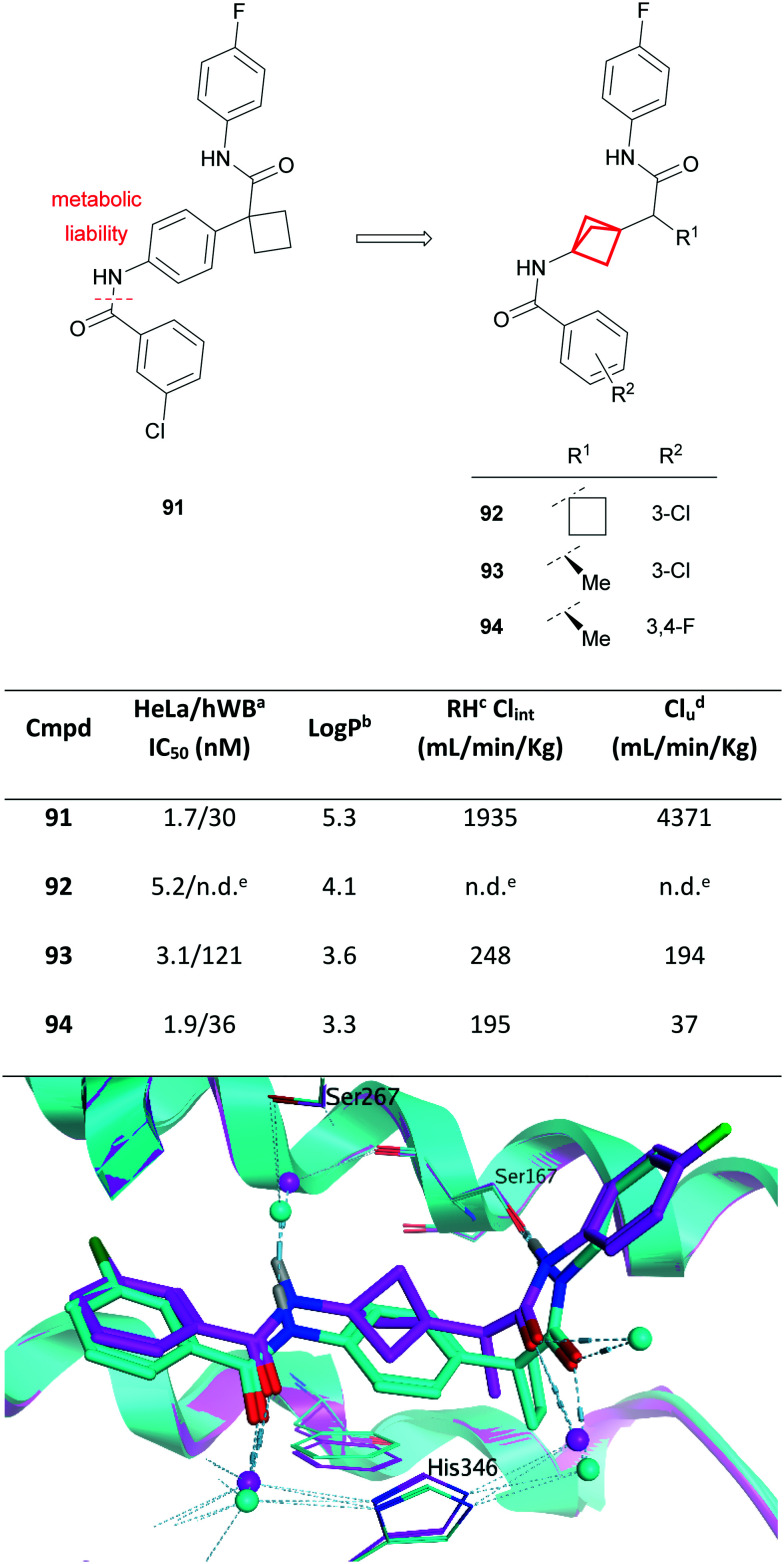

Similar improvements in metabolic stability, lipophilicity and solubility have been observed through analogous phenyl replacements with BCP.171–174 For example, recent work from scientists at Merck has shown the use of BCP as a phenyl isostere to address concerns of metabolic instability (Fig. 39). Compound 91 was identified from an automated ligand identification system to have excellent potency against IDO1.86,175 Compound 91, whilst achieving excellent potency in cell-based and whole cell assays, was limited by poor metabolic stability in both in vitro and in vivo rat PK studies.

Fig. 39. Top: Development of IDO1 inhibitors.86,175aHuman whole blood assay. bLog P = Alog P98.44cRat hepatocytes, in vitro unbound clearance. dIn vivo PK study performed in rat. eNot determined. Bottom: Overlay of IDO1-bound structures of 93 (magenta; PDB code: 6WJY) and related aryl-linked bisamide (cyan; PDB code: 6V52) illustrating the utility of BCP as an isostere of a phenyl spacer. Water molecules are shown as spheres; hydrogen bonds are shown as pale blue dashed lines.

MetID studies identified amide bond cleavage as the predominant metabolic pathway (Fig. 39), generating a potentially mutagenic aniline metabolite.176 Alternative modifications, including the use of amide bioisosteres, provided insufficient improvement in metabolic stability or led to significant loss of cellular potency. Molecular modelling (later corroborated by X-ray crystallography; Fig. 39 bottom) indicated that the BCP ring could be well tolerated in the binding site, acting predominantly as a linker, presenting an opportunity to mitigate hydrolysis of the amide in compound 91. Direct isosteric replacement of the phenyl group with a BCP in 92 engendered a significant reduction in lipophilicity, albeit with a slight reduction in potency. Subsequent replacement of the α-CyBu with a chiral methyl group (93) could further decrease the lipophilicity and improved both potency and stability, translating to a good overall PK profile including low clearance and excellent oral bioavailability. Further modification of the aryl substituents (R2) led to the discovery of compound 94, which exhibited excellent potency, good PK and a much lower predicted human dose relative to previously reported IDO1 inhibitors.86,175

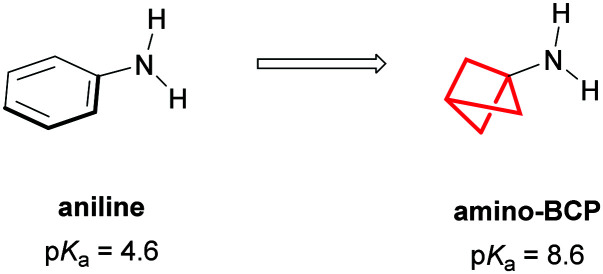

Aniline bioisostere

Amino-BCPs have also been shown to provide a metabolically stable bioisostere for anilines, proving more resistant to reactive metabolite formation and CYP450 inhibition.177 However, replacement of an aniline with an amino-BCP can strongly influence the basicity of the nitrogen (pKa(aniline) = 4.6, pKa(amino-BCP) = 8.6),178 changing the ion class of the compound (Fig. 40).101,102,179

Fig. 40. Amino-BCP as an isostere of aniline.

Limitations of bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes

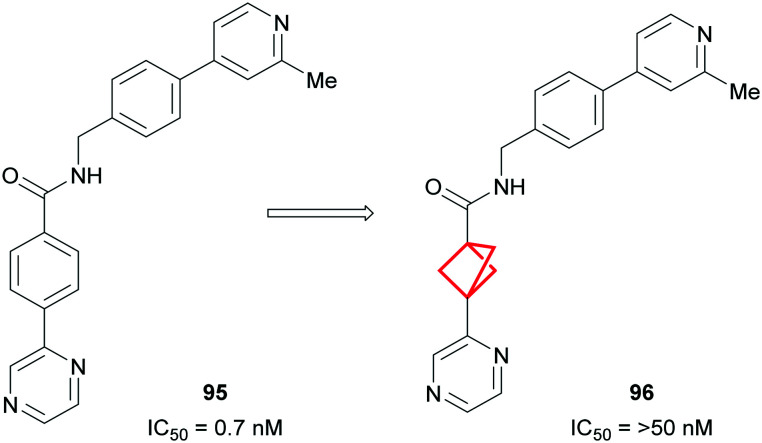

Loss of biological activity

While it is evident that physicochemical properties and PK can be improved by replacing a phenyl ring with a BCP motif, this successful isosterism cannot always be achieved. In the event that the phenyl group is important for binding affinity, i.e. through the formation of π-stacking interactions, replacement with a BCP ring can result in significant loss of potency.180,181 This was exemplified by Adsool and co-workers who found that replacement of the phenyl ring in Wingless Int-1 (Wnt)182 inhibitor 95 resulted in complete loss of activity for 96 in the cell-based reporter assay (Fig. 41).183

Fig. 41. Replacement of phenyl ring with BCP in known Wnt inhibitor causing loss of biological activity.183.

Synthetic tractability

Synthetic incorporation of the BCP motif in many cases still remains a challenge and, until recently, efficient synthetic methodologies have been elusive. As a result, commercially available reagents can be limited, expensive and have long lead times. Additionally, due to the difficulty of synthesis of more highly substituted BCP variants, the isosteric replacement of aromatic rings with BCP has largely been limited to mono- or para-substituted benzenes. Isosteric replacement of meta- and/or ortho-substituted benzenes with aliphatic rings remains relatively underexplored.160,184,185 However, during the preparation of this manuscript, a report describing the synthesis of 1,2-disubstituted BCPs was published, now facilitating the potential to investigate this substitution pattern for bioisosterism of ortho- or meta-substituted arenes.186

Outlook

The use of the BCP ring in medicinal chemistry has largely been precluded by the lack of synthetically tractable access to these novel bioisosteric scaffolds. In recent years the increase in prevalence of the BCP motif has gone hand in hand with the advent of increasingly efficient synthetic methods allowing more facile incorporation of this bicyclic scaffold.158–166 This is exemplified by the surge of appearances of BCPs in patents in recent years (Fig. 2). With growing attention from the synthetic community regarding access to these scaffolds, and the potential impact on physicochemical properties and PK profiles, the BCP bicyclic ring system will likely become more commonplace within medicinal chemistry.

Conclusions

This review aims to provide a brief comparative overview of the applications of three- and four-membered aliphatic rings to medicinal chemistry drug discovery projects. The small nature of these ring systems often engenders improvements in the physicochemical properties of molecules when replacing larger groups, positively impacting ADME end points such as metabolism and solubility. In addition, the rigid structures of the small rings provides opportunity to design conformationally restricted analogues, enhancing target protein binding affinity through minimised entropic penalties, as well as providing specific vectors between pharmacophoric features. Furthermore, the unique physicochemical, structural and electronic properties of each ring system has been utilised to overcome many other specific medicinal chemistry problems.

Reported medicinal chemistry liabilities are also known for each ring system, illustrated herein to increase awareness. However, it should be noted that many of these shortcomings are likely context specific and may not present when the overall molecular structure differs. A considerable limitation for several of these ring systems is synthetic tractability. Whilst general methods of assembly are reported, protocols for making specific point changes (that would be highly enabling for design of drug molecules) remain limited.

The interest in these small rings will undoubtedly increase as more creative medicinal chemistry applications are demonstrated, and as synthetic methodologies are developed that facilitate access to a more diverse array of substitution patterns. It is anticipated that the existing and newly emerging variants of these systems will continue to feature in future drug discovery programs.

Conflicts of interest

All authors are employees of AstraZeneca.

All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Notes and references

- Lovering F. MedChemComm. 2013;4:515–519. doi: 10.1039/C2MD20347B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H. Tawa G. Wallqvist A. Drug Discovery Today. 2012;17:310–324. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal M. V. Wolfstädter B. T. Plancher J.-M. Gatfield J. Carreira E. M. ChemMedChem. 2015;10:461–469. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuitschik G. Carreira E. M. Wagner B. Fischer H. Parrilla I. Schuler F. Rogers-Evans M. Müller K. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:3227–3246. doi: 10.1021/jm9018788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin M. Yazaki R. Fessard T. C. Carreira E. M. Org. Lett. 2014;16:4070–4073. doi: 10.1021/ol501590n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meanwell N. A. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:2529–2591. doi: 10.1021/jm1013693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meanwell N. A. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016;29:564–616. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson C. Moir E. M. Rankovic Z. Wishart G. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:5029–5046. doi: 10.1021/jm060379l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering F. Bikker J. Humblet C. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:6752–6756. doi: 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie T. J. MacDonald S. J. F. Drug Discovery Today. 2009;14:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie T. J. Macdonald S. J. F. Young R. J. Pickett S. D. Drug Discovery Today. 2011;16:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talele T. T. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:8712–8756. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girija S. S. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2016;16:892–904. doi: 10.2174/1389557515666150709122244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes A. R. Varela C. L. Tavares-da-Silva E. J. Roleira F. M. F. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;201:112327. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath A. Ojima I. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:10640–10664. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2012.07.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veinberg G. Potorocina I. Vorona M. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014;21:393–416. doi: 10.2174/09298673113206660268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J. F. and Mobashery S., The β-lactam (azetidin-2-one) as a privileged ring in medicinal chemistry, RSC Publishing, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Storer R. I. Aciro C. Jones L. H. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:2330–2346. doi: 10.1039/C0CS00200C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti L. A. Kumawat L. K. Mao N. Stephens J. C. Elmes R. B. P. Chem. 2019;5:1398–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. R. Robertson A. A. B. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:6945–6963. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M. M. Olaoye O. O. Molecules. 2020;25:2285. doi: 10.3390/molecules25102285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halloran M. W. Lumb J.-P. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019;25:4885–4898. doi: 10.1002/chem.201805004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searles S. Tamres M. Block F. Quarterman L. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956;78:4917–4920. doi: 10.1021/ja01600a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- RDkit: Open-source chemiinformatics:, http://www.rdkit.org, (accessed Sept 2020)

- TIBCO Spotfire 10.3.1., https://www.tibco.com/products/tibco-spotfire, (accessed Sept 2020)

- COSMOtherm release 19.0.1, COSMOlogic GmbH & Co KG, a Dassault Systèmes Company

- Eckert F. Klamt A. AIChE J. 2002;48:369–385. doi: 10.1002/aic.690480220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Integrity, https://integrity.clarivate.com/integrity/xmlxsl/pk_home.util_home, (accessed Aug 2020)

- Gagnon A. Duplessis M. Fader L. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 2010;42:1–69. doi: 10.1080/00304940903507788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landry M. L. Crawford J. J. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:72–76. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai A. C. Crews C. M. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2017;16:101–114. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengerle M. Chan K.-H. Ciulli A. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015;10:1770–1777. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares P. Gadd M. S. Frost J. Galdeano C. Ellis L. Epemolu O. Rocha S. Read K. D. Ciulli A. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:599–618. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson S. D. Yang B. Fallan C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;29:1555–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnaby W. Koegl M. Roy M. J. Whitworth C. Diers E. Trainor N. Zollman D. Steurer S. Karolyi-Oezguer J. Riedmueller C. Gmaschitz T. Wachter J. Dank C. Galant M. Sharps B. Rumpel K. Traxler E. Gerstberger T. Schnitzer R. Petermann O. Greb P. Weinstabl H. Bader G. Zoephel A. Weiss-Puxbaum A. Ehrenhöfer-Wölfer K. Wöhrle S. Boehmelt G. Rinnenthal J. Arnhof H. Wiechens N. Wu M.-Y. Owen-Hughes T. Ettmayer P. Pearson M. McConnell D. B. Ciulli A. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019;15:672–680. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0294-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao C. Zhao F. Song H. Guo J. Li X. Jiang X. Huan R. Song S. Zhang Q. Wang R. Wang K. Pang Y. Liu T. Lu T. Huang W. Wang J. Lin B. He Z. Li H. Li F. Zhao D. Cheng M. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:265–285. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouvry G. Atrux-Tallau N. Bihl F. Bondu A. Bouix-Peter C. Carlavan I. Christin O. Cuadrado M.-J. Defoin-Platel C. Deret S. Duvert D. Feret C. Forissier M. Fournier J.-F. Froude D. Hacini-Rachinel F. Harris C. S. Hervouet C. Huguet H. Lafitte G. Luzy A.-P. Musicki B. Orfila D. Ozello B. Pascau C. Pascau J. Parnet V. Peluchon G. Pierre R. Piwnica D. Raffin C. Rossio P. Spiesse D. Taquet N. Thoreau E. Vatinel R. Vial E. Hennequin L. F. ChemMedChem. 2018;13:321–337. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201700758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwertz G. Witschel M. C. Rottmann M. Bonnert R. Leartsakulpanich U. Chitnumsub P. Jaruwat A. Ittarat W. Schäfer A. Aponte R. A. Charman S. A. White K. L. Kundu A. Sadhukhan S. Lloyd M. Freiberg G. M. Srikumaran M. Siggel M. Zwyssig A. Chaiyen P. Diederich F. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:4840–4860. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. J. Johnson A. R. Misner D. L. Belmont L. D. Castanedo G. Choy R. Coraggio M. Dong L. Eigenbrot C. Erickson R. Ghilardi N. Hau J. Katewa A. Kohli P. B. Lee W. Lubach J. W. McKenzie B. S. Ortwine D. F. Schutt L. Tay S. Wei B. Reif K. Liu L. Wong H. Young W. B. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:2227–2245. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalgutkar A. S. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:6276–6302. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. J. Lee W. Johnson A. R. Delatorre K. J. Chen J. Eigenbrot C. Heidmann J. Kakiuchi-Kiyota S. Katewa A. Kiefer J. R. Liu L. Lubach J. W. Misner D. Purkey H. Reif K. Vogt J. Wong H. Yu C. Young W. B. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:1588–1597. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappas M. Ali A. A. E. Bennett K. A. Brown J. D. Bucknell S. J. Congreve M. Cooke R. M. Cseke G. de Graaf C. Doré A. S. Errey J. C. Jazayeri A. Marshall F. H. Mason J. S. Mould R. Patel J. C. Tehan B. G. Weir M. Christopher J. A. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:1528–1543. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster A. B. Abeywickrema P. Bunda J. Cox C. D. Cabalu T. D. Egbertson M. Fay J. Getty K. Hall D. Kornienko M. Lu J. Parthasarathy G. Reid J. Sharma S. Shipe W. D. Smith S. M. Soisson S. Stachel S. J. Su H.-P. Wang D. Berger R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;27:5167–5171. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose A. K. Viswanadhan V. N. Wendoloski J. J. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:3762–3772. doi: 10.1021/jp980230o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. W. Gallego R. A. Edwards M. P. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:6401–6420. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson P. D. Springthorpe B. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2007;6:881–890. doi: 10.1038/nrd2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs H. Bravi G. Campbell I. Convery M. Davies H. Inglis G. Pal S. Peace S. Redmond J. Summers D. J. Med. Chem. 2019;62:6972–6984. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W. Sun C. Xu S. Wu C. Wu J. Xu M. Zhao H. Chen L. Zeng W. Zheng P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;22:6746–6754. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K. K. C. Bailey S. Dinh D. M. Lam H. Li C. Wells P. A. Yin M.-J. Zou A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:5114–5117. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zask A. Kaplan J. Verheijen J. C. Richard D. J. Curran K. Brooijmans N. Bennett E. M. Toral-Barza L. Hollander I. Ayral-Kaloustian S. Yu K. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:7942–7945. doi: 10.1021/jm901415x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkó K. Bevan C. Reynolds D. Anal. Chem. 1997;69:2022–2029. doi: 10.1021/ac961242d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson M. Johnson D. S. Rankic D. A. Kauffman G. W. Ende C. W. Am. Butler T. W. Boscoe B. Evrard E. Helal C. J. Humphrey J. M. Stepan A. F. Stiff C. M. Yang E. Xie L. Bales K. R. Hajos-Korcsok E. Jenkinson S. Pettersen B. Pustilnik L. R. Ramirez D. S. Steyn S. J. Wood K. M. Verhoest P. R. MedChemComm. 2017;8:730–743. doi: 10.1039/C6MD00406G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezençon O. Heidmann B. Siegrist R. Stamm S. Richard S. Pozzi D. Corminboeuf O. Roch C. Kessler M. Ertel E. A. Reymond I. Pfeifer T. de Kanter R. Toeroek-Schafroth M. Moccia L. G. Mawet J. Moon R. Rey M. Capeleto B. Fournier E. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:9769–9789. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Seeman D. Jain M. Bell L. Ferreira S. Cohen S. Chen X.-H. Amin J. Snodgrass B. Hatsis P. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:514–516. doi: 10.1021/ml400045j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalgutkar A. S. Soglia J. R. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2005;1:91–142. doi: 10.1517/17425255.1.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaweska H. Fitzpatrick P. F. Biomol. Concepts. 2011;2:365–377. doi: 10.1515/BMC.2011.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerny M. A. Hanzlik R. P. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;436:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell D. J. Nikolic D. van Breemen R. B. Silverman R. B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:1757–1760. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]