Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Brain bioenergetics are defective in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Preclinical studies find oxaloacetate (OAA) enhances bioenergetics, but human safety and target engagement data are lacking.

METHODS:

We orally administered 500 or 1000 mg OAA, twice daily for 1 month, to AD participants (n=15 each group) and monitored safety and tolerability. To assess brain metabolism engagement, we performed fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) before and after the intervention. We also assessed pharmacokinetics and cognitive performance.

RESULTS:

Both doses were safe and tolerated. Compared to the lower dose, the higher dose benefited FDG PET glucose uptake across multiple brain regions (p<0.05), and the higher dose increased parietal and frontoparietal glutathione (p<0.05). We did not demonstrate consistent blood level changes and cognitive scores did not improve.

CONCLUSIONS:

1000 mg OAA, taken twice daily for 1 month, is safe in AD patients and engages brain energy metabolism.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, bioenergetics, metabolism, oxaloacetate, safety

BACKGROUND

Energy metabolism constitutes a potential Alzheimer’s disease (AD) therapeutic target [1]. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) reveals reduced AD brain glucose utilization [2, 3], and lower oxygen uptake on oxygen PET could reflect deficient mitochondrial respiration [4]. Direct assessments of AD patient brain mitochondria show perturbed mitochondrial function and integrity [5-9]. Mitochondrial dysfunction in AD extends beyond the brain [10, 11], which suggests a relatively upstream role for defective energy metabolism in this disease [12, 13].

Promoting carbon flux through energy metabolism pathways could conceivably alleviate energy stress and normalize inter-connected biochemical pathways. Potential approaches include boosting pathway intermediates to change pathway equilibrium, or changing bioenergetic flux regulation [14]. Preclinical studies suggest oxaloacetate (OAA) could accomplish either goal [15]. In the cytosol, OAA reduction to malate by malate dehydrogenase 1 (MDH1) consumes NADH electrons to generate NAD+. Increasing the cytosolic NAD+/NADH ratio should enhance glycolysis flux, and in vitro experiments found adding OAA to cultured cells increased their NAD+/NADH ratio and glycolysis flux [16]. The malate product could access mitochondria, where oxidation back to OAA in the Krebs cycle would generate NADH and electrons for the respiratory chain. In support of this, adding OAA to cultured cells increased their respiration [16].

OAA carbon can access other pathways and prime the consumption or synthesis of other intermediates. Administered in high amounts to mice, OAA modifies proteins and pathways that monitor and respond to brain metabolic states [17]. Whether OAA can modify brain chemistry in human AD, though, is unknown. To address this, we administered OAA to persons with AD. The goal of this “Trial of OAA in AD” (TOAD) study was to determine whether it is possible to affect brain metabolism at a tolerable OAA dose. Partial and preliminary analyses from this study were reported in abstract form [18-20].

METHODS

Participants

The TOAD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02593318) was approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC) Human Subjects Committee and informed consent was obtained for all participants. All met current McKhann AD criteria [21]. Men and women with very mild, mild, or moderate AD were eligible. Supplementary Figure 1 shows the study plan.

Dosing Plan and Safety Assessments

The Food and Drug Administration reviewed and approved the study protocol. The TOAD was designed as a Phase Ib study with safety as its primary outcome. We assessed two OAA doses, 500 mg twice daily and 1000 mg twice daily, taken for approximately 1 month. We selected 500 mg twice daily as the lower dose after previously documenting 100 mg twice daily was tolerated [22], and because a study in diabetics reported doses up to 1000 mg/day were safe [23].

We planned to enroll 15 participants in each arm, ascertain adverse events, and determine the dose limiting toxicity (DLT) frequency. We required completion of the lower dose arm before enrolling any participants into the higher dose group. To ensure our DLT rate could not exceed 20% for either dose, enrollment was limited to no more than 3 participants at any time.

Pre- and post-treatment complete blood count (CBC), serum electrolyte, serum liver function test (LFT), and glucose testing informed the safety assessment. We administered a standard 35-point symptom checklist at the time of enrollment, at the end of the treatment period, and 1 month after completing treatment.

Imaging Biomarkers

We used FDG PET and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to assess target engagement. Participants underwent scans immediately prior to starting treatment and at the end of the 1-month treatment period. MRS and FDG PET scans were obtained within 2 days of each other.

Magnetic resonance (MR) scans were performed using a 3T scanner (Skyra, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a 20-channel head/neck receiver coil. T1-weighted MRI was acquired using an MPRAGE sequence (TR/TE/TI=2500/4.4/1100 ms, flip angle=9°, FOV=256x192 mm2, 176 slices, slice thickness=1 mm, GRAPPA acceleration factor=2) for anatomical reference. Three single-voxel MRS (SVS) scans were performed using a Semi-LASER sequence (TR=2000 ms, voxel size=40x30x20 mm3, number of averages=64) with prospective frequency corrections that actively compensate scanner frequency drift commonly present in MR scans [24]: short TE MRS (TE=35 ms) to measure N-acetylaspartate (NAA), creatine (Cr), choline (tCho), myo-inositol (mI), and Glx (glutamate+glutamine); long TE MRS (TE=144 ms) to measure lactate; and TE-averaged Semi-LASER to measure glutamate (Glu) (TE=35-227 ms with 6 ms steps, 32 increments, number of averages=4). Reduced glutathione (GSH) was measured from an axial slice in the frontoparietal regions using selective multiple quantum MRSI (TR/TE=1500/115 ms, FOV=200 x 200 mm2, matrix=10x10, slice thickness=2.5 cm) [24, 25]. Pre and post-treatment scans were matched for voxel and slice placement using vendor-provided automatic slice alignment software and based on anatomical landmarks. SVS data were analyzed using LCModel with basis sets generated by spectral simulation software (VeSPA, https://scion.duhs.duke.edu/vespa/simulation) at each echo time. Metabolite concentrations in SVS were measured using the internal concentration reference relative to unsuppressed water. Metabolite concentrations were corrected for tissue fraction in each voxel using the segmented MPRAGE images corresponding to the spectroscopic voxels. We also deployed a specialized sequence to more accurately measure GSH. GSH signals were quantified using in-house developed software for the frontal, parietal, and frontoparietal regions using the simultaneously measured creatine as an internal concentration reference as described previously [25] and summarized in the Supplementary Methods section.

FDG PET images were obtained on a GE Discovery ST-16 PET/CT scanner. After an overnight fast an intravenous catheter was inserted, the participant was placed in a supine position, and a 10 mCi FDG bolus was given. Images were acquired, reconstructed, and attenuation corrected to a single PET image. Images were processed using the PET PVE12 pipeline operating under SPM12 (www.fil.ion.ac.uk/spm) [26]. Briefly, the anatomical MR images from the MRS session were segmented into tissue type using the unified segmentation process as implemented in the VBM8 toolbox (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de). Partial volume effects (PVE) correction was performed based on the Muller-Gartner algorithm [27]. Intensity normalization was performed by dividing the PVE-corrected images by the mean signal intensity of the pons to generate a standard uptake value ratio (SUVR) image. PET PVE12 was used to extract the mean SUVR from each image using the Desikan-Killiany atlas to define regions of interest.

OAA Integrity, Blood Measurements, and Cognitive Testing

Terra Biological, LLC (San Diego) provided the OAA. Terra markets hypromellose capsules that contain 100 mg of anhydrous enol-OAA and ascorbic acid. For this study Terra provided hypromellose capsules containing 500 mg anhydrous enol-OAA and no ascorbic acid. We serially monitored the OAA stocks from which our capsules derived to ensure its content remained over 95% OAA.

Each subject took their first one or two OAA capsules in the KUMC Clinical Trials Unit (CTU), in the morning following an overnight fast. A blood sample was obtained just before swallowing the OAA and at 60 and 90 minutes after this. The blood was added to an Eppendorf tube containing anticoagulant and centrifuged to separate the plasma from the red blood cells. The plasma was removed and stored at −80°C and samples were batched for measurements of OAA and pyruvate content. Plasma OAA and pyruvate were determined using a validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay.

The cognitive assessment battery included the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale cognitive portion (ADAS-Cog11), MMSE, immediate and delayed Logical Memory test (LMT), and the color naming portion of the Stroop test. The test battery was administered before starting the intervention and was repeated while concluding the 1-month treatment.

Statistics

We performed a linear mixed-effects analysis of the effect of treatment dose on our outcomes using R (R Core Team, Vienna Austria) and the lme4 package. We entered dose (1g/day, 2g/day) and timepoint (baseline, 1-month follow-up) into the model as fixed effects and included random intercepts for participants. P-values were obtained by likelihood ratio tests of the full model including the interaction of timepoint and dose against the model without the interaction. For supporting and post-hoc analyses, we performed paired and unpaired Student’s t-tests. Analyses were conducted with α=0.05 to protect against Type I error. We did not correct for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

The first participant enrolled in January 2016 and the final participant completed the study in September 2018. We consented 31 unique participants. Three consented twice and enrolled in both the 500 mg (lower dose) and 1000 mg (higher dose) twice daily groups. Each arm enrolled seventeen participants. One from each arm screen-failed and did not advance to the baseline visit; one in the lower dose group withdrew consent following MRS claustrophobia during the baseline visit; and one in the higher dose group withdrew after the baseline visit for unknown reasons, was lost to follow-up, and did not complete any post-treatment evaluations. Aside from adverse events recording, our analyses do not include data from these four participants. In total, we acquired 30 sets of pre-and post-treatment data, 15 from the lower and 15 from the higher dose group. Table 1 provides participant demographics.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

One participant enrolled into each group screen-failed; one participant enrolled into the lower dose group withdrew consent during the baseline visit; and one participant in the higher dose group discontinued for unknown reasons after the baseline visit, was lost to follow-up, and did not generate post-treatment data. SD=standard deviation.

| Participants Enrolled |

Participants with Pre/Post Data |

Participants with Pre/Post Data Age (Mean±SD) |

Participants with Pre/Post Data Age (Range) |

Male/ Female |

Participants with Pre/Post Data MMSE Baseline (Mean+SD) |

Participants with Pre/Post Data MMSE (Range) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 mg Twice Daily | 17 | 15 | 70.0±5.7 | 62-81 | 6/9 | 21.5±4.3 | 14-27 |

| 1000 mg Twice Daily | 17 | 15 | 71.3±8.1 | 55-84 | 4/11 | 21.9±3.2 | 16-28 |

CBC, electrolyte, LFT, and glucose screening did not reveal any consistent treatment-related alterations (data not shown). We determined no DLT events. Table 2 lists adverse events for the 15 participants from each group who contributed to the full analysis. One participant on the higher dose experienced nausea, relieved by taking the OAA with food. We attributed this adverse event to the study drug. In the lower dose group, one participant with evolving psychotic confusion, documented before starting the OAA, continued to worsen throughout the intervention and the entire one-month post-treatment follow-up period. Because symptom progression was clearly present before and after the treatment period, we did not attribute it to the treatment. Another participant in the lower dose group experienced increased confusion only during the post-treatment follow-up period, while no longer taking OAA, and we did not attribute this post-treatment worsening confusion to the study drug.

Table 2. Adverse events for the 15 participants from each group who contributed pre-and-post intervention data.

| Intervention | AE | Number with the AE |

Likely or Unlikely Related to OAA |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 mg Twice Daily (n=15) | Increased confusion | 2 | Unlikely | Began or worsened during post-treatment follow-up period |

| Cervical stenosis | 1 | Unlikely | ||

| Syncope | 1 | Unlikely | ||

| 1000 mg Twice Daily (n=15) | Nausea | 1 | Likely | Resolved by taking capsules with food |

| Sinus infection | 1 | Unlikely | ||

| Breast calcification | 1 | Unlikely |

We ascertained three adverse events not listed in Table 2. One participant exhibited profound bradycardia during their screening visit, which resulted in screen failure. Another experienced claustrophobia during their baseline visit MRS, before receiving any OAA. A participant in the high-dose group who withdrew after their baseline evaluation noted intermittent stomach upset that did not require intervention. As this participant was lost to follow-up we could not attribute causality, but nevertheless we considered this a possibly related adverse event.

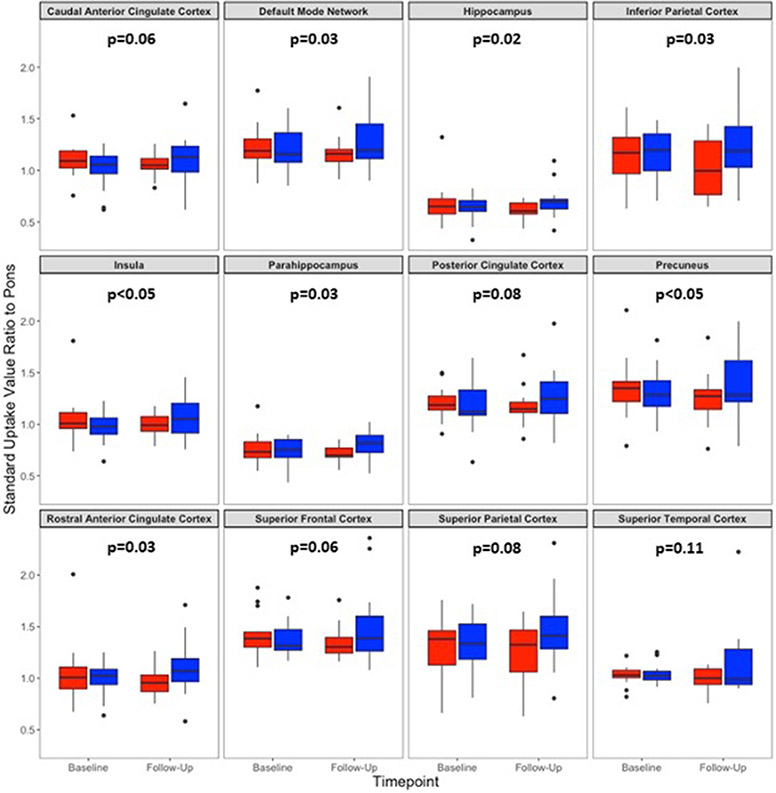

Linear mixed-model analysis showed significant dose by time effects across multiple FDG PET SUVR regions (Figure 1). Benefits for the higher dose group were seen in the default mode network (DMN) (p=0.04), rostral anterior cingulate (p=0.03), precuneus (p<0.05), inferior parietal cortex (p=0.03), insula (p<0.05), hippocampus (p=0.02), and parahippocampal gyrus (p=0.03). Other regions, including the posterior cingulate cortex (p=0.08), superior frontal cortex (p=0.06), superior parietal cortex (p=0.08), caudal anterior cingulate (p=0.06), and superior temporal cortex (p=0.11) trended towards a higher dose benefit following the intervention.

Figure 1. Dose by timepoint FDG PET SUVR by region of interest.

The box and whiskers plots illustrate pre- and post-treatment SUVR values across 12 regions. The lower dose is shown in red, and the higher dose in blue. P values were determined using a linear mixed-model approach and reflect the significance of the primary effect of interest, the dose by time interaction. They were obtained by likelihood ratio tests of a full linear mixed model of OAA dose and study timepoint. This was tested against a reduced model without the interaction. P values between 0.045 and 0.049 are designated as <0.05; for other values the rounded decimal is indicated. The DMN values are a composite average of superior parietal cortex, precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex, and rostral anterior cingulate cortex measurements.

To further explore these interactions, we performed paired t-test comparisons on pre- and post-treatment values. With the lower dose, post-treatment values trended lower than the pre-treatment values, and on one occasion this change reached statistical significance (p<0.05 for the inferior parietal cortex) (Supplementary Table 1). Conversely, with the higher dose post-treatment values trended higher than the pre-treatment values, but these changes did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Table 1). In general, pre-versus-post intervention percent changes showed substantial variability, with each standard deviation value exceeding its associated mean.

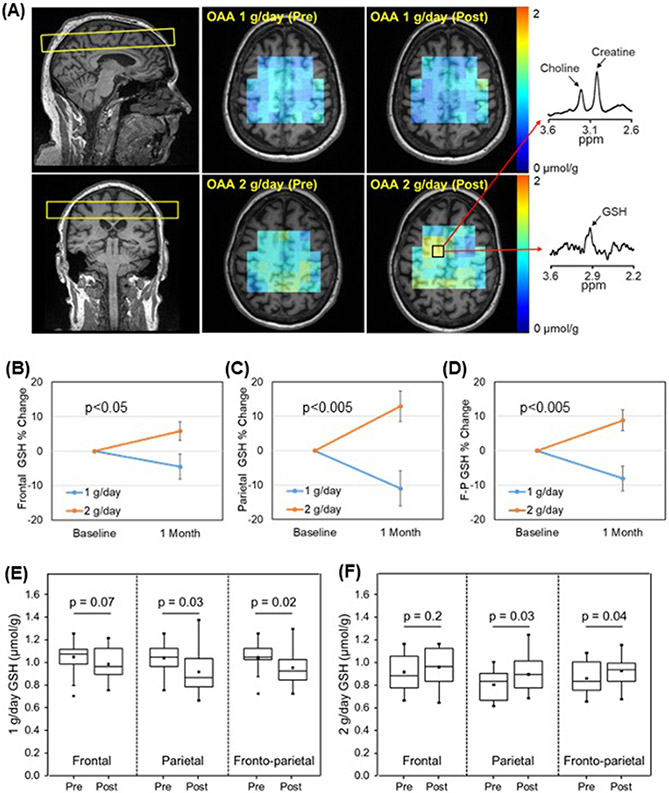

We also used MRS to assess target engagement. Figure 2A shows the slice placement used to obtain GSH maps, a spatial representation of the pre- and post-treatment GSH concentrations, and representative GSH and creatine spectra. For the GSH measurements there were 14 successful paired scans in the lower dose group (one participant’s scans were degraded by motion) and 15 successful paired scans in the higher dose group. All three brain regions showed a dose by time interaction (frontal, p=0.02; parietal, p=0.0007; frontoparietal, p=0.0007) (Figure 2B-D). On unpaired t-tests mean GSH concentrations trended down with the lower dose and up in the higher dose (Supplementary Table 2). For the parietal and frontoparietal regions a paired analysis showed statistically significant decreases in GSH with the lower dose (parietal p=0.03, frontoparietal p=0.02) and a statistically significant increase in GSH with the higher dose (parietal p=0.03, frontoparietal p=0.04) (Figure 2E-F).

Figure 2. Brain GSH.

(A) GSH MRSI slice placement (left), GSH maps (middle), and representative MR spectra of GSH and simultaneously measured creatine and choline signals (right). (B) Frontal region percent changes between pre- and post-treatment GSH levels. (C) Parietal region percent changes between pre- and post-treatment GSH levels. (D) Frontoparietal (F-P) region percent changes between pre- and post-treatment GSH levels. (E) Mean regional GSH levels pre and post the 1 g/day dose. Levels mostly decreased over the 1-month treatment period. (F) Mean regional GSH levels pre and post the 2 g/day dose. Levels mostly increased over the 1-month treatment period. Error bars in B-D are SEM.

Lactate, glutamate, and standard neurochemical profile measurements did not reveal any statistically significant changes (Supplementary Figure 2). Supplementary Figure 3 shows pre and post-treatment spectra of GSH and simultaneously measured creatine signals, with overlaid spectral fit lines. We tested for correlations between GSH and FDG PET SUVR pre and post-treatment regional changes and detected a modest positive correlation between parietal GSH and FDG PET SUVR measurements (Supplementary Figure 4).

We did not observe any statistically significant differences between the pre- and post-treatment cognitive test score means (Table 3). On paired t-test, in the lower dose group there was a significant decline in the post-treatment MMSE scores as compared to the pre-intervention MMSE scores (p=0.04). All other cognitive test pre- versus post-treatment paired t-test comparisons were non-significant. We did not detect any correlations between changes in cognitive test scores and changes in either MRS GSH or FDG PET SUVR regional values (Supplementary Figure 4).

Table 3. Cognitive test results.

Values are group means (standard deviation).

| Cognitive Test | Intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 mg Twice Daily (n=15) | 1000 mg Twice Daily (n=15) | |||

| Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | |

| MMSE | 21.5 (4.4) | 20.0 (5.0) | 21.9 (3.3) | 20.7 (2.6) |

| ADASCog11 | 22.2 (10.4) | 23.3 (11.0) | 18.5 (5.2) | 20.9 (5.2) |

| LMT (Immediate Recall) | 2.8 (3.0) | 3.5 (3.0) | 2.7 (2.8) | 3.7 (3.1) |

| LMT (Delayed Recall) | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.7 (1.3) | 1.2 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.9) |

| Stroop Color Naming (total correct)* | 49.1 (21.2) | 49.2 (25.5) | 47.0 (16.9) | 46.1 (17.2) |

Two participants from the lower dose group were unable to complete the Stroop test, so for the Stroop test lower dose group the n=13.

We measured OAA levels in plasma samples obtained immediately before, 60 minutes after, and 90 minutes after the first OAA dose (Table 4). Plasma OAA concentration measurements varied tremendously between individuals, with standard deviations for each time point ranging from 51-109% of the corresponding mean value. Because we batch-analyzed samples we compared batch means and found substantial inter-batch variation. Supplementary Table 3 shows the extent to which the different PK assay batches generated different results. To address this we normalized each participant’s 60 and 90-minute OAA concentration measurements to their baseline measurements, which reduced the standard deviation:mean concentration ratios to 19%-50%, but still we did not observe a significant dose-related increase in the plasma OAA level.

Table 4. Pharmacokinetics data.

n=15 for both doses.

| Dose | Parameter | Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Minutes | 60 Minutes | 90 Minutes | ||

| 500 mg | OAA (ng/ml) | 94 (102) | 63 (55) | 87 (80) |

| OAA (normalized) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.01 (0.51) | 1.15 (0.41) | |

| Pyruvate (ng/ml) | 8298 (3293) | 8305 (3532) | 7621 (3184) | |

| Pyruvate (normalized) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.15) | 0.93 (0.14) | |

| OAA/Pyruvate | 0.010 (0.009) | 0.007 (0.005) | 0.010 (0.007) | |

| OAA/Pyruvate (normalized) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.02 (0.48) | 1.30 (0.56)* | |

| 1000 mg | OAA (ng/ml) | 1400 (962) | 1355 (690) | 1363 (759) |

| OAA (normalized) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.07 (0.20) | 0.99 (0.19) | |

| Pyruvate (ng/ml) | 10254 (5045) | 9688 (3891) | 9200 (3966) | |

| Pyruvate (normalized) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.98 (0.16) | 0.93 (0.16) | |

| OAA/Pyruvate | 0.14 (0.06) | 0.15 (0.06) | 0.16 (0.079) | |

| OAA/Pyruvate (normalized) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.09 (0.17)* | 1.11 (0.30) | |

p<0.05, unpaired t-test relative to 0 minutes.

Because OAA can decarboxylate to form pyruvate, we measured plasma pyruvate levels and similarly analyzed the magnitude of change relative to the pyruvate baseline (Table 4). The 60 and 90-minute post-dose plasma pyruvate levels did not change significantly from the baseline when considered as absolute concentrations or normalized values. Lastly, we divided the OAA concentration for each sample by its corresponding pyruvate concentration and further normalized each 60 and 90-minute OAA/pyruvate value to its corresponding baseline value. This calculation revealed a significant 30% increase in the plasma OAA/pyruvate relative value 90 minutes after 500 mg of OAA (p<0.05), and a significant 9% increase 60 minutes after 1000 mg (p<0.05) (Table 4).

To track the integrity of the OAA used throughout the study, at frequent intervals we assessed the stability of the OAA stocks from which our capsules derived. The percentage of OAA in the measured samples did not fall below 95% (Supplementary Table 4). In terms of OAA content, the OAA stocks from which our capsules derived appeared stable for over 1 year.

DISCUSSION

In AD, OAA doses of 500 or 1000 mg, twice daily orally for one month, are safe and tolerated. The higher dose appears to engage brain metabolism. We conclude in individuals with AD, it is possible to engage brain energy metabolism at an OAA dose that is tolerated by those individuals.

OAA potentially caused a mild gastrointestinal side-effect in up to two of 16 individuals that received the higher dose (12.5%). In one participant, taking the OAA with food relieved this complaint. Short-duration safety studies, though, do not eliminate the possibility that longer-term exposures could cause unanticipated side effects. It will be interesting to see if higher doses or longer exposures generate a more reliable pattern of gastrointestinal irritation.

The optimal way to determine engagement in studies that target brain energy metabolism and mitochondrial function is unclear. Blood-based biomarkers can directly assess effects on metabolism or mitochondria in peripheral tissue [28-30] but positive results do not guarantee concurrent central nervous system effects. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) changes could perhaps reassure in this respect, but CSF procurement may complicate participant recruitment, we lack validated CSF biomarkers of metabolism or mitochondrial function, and CSF is not itself brain tissue. Neuroimaging approaches can more directly screen for metabolism changes and perhaps indirectly screen for changes to brain mitochondria, but the sensitivity and specificity of these approaches for detecting target engagement remains unclear.

Compared to the lower OAA dose, the higher OAA dose benefited the FDG PET SUVR across multiple regions. Other AD intervention studies also used FDG PET to assess brain energy metabolism engagement. Intervention duration in these studies ranged from six to 12 months [31-33] and included placebo groups in which glucose utilization declined over time [31, 32]. We suspect trends towards reduced FDG PET glucose uptake in our study’s lower dose group reflects the expected progressive decline for this biomarker, but without a placebo group we cannot confirm this.

Others propose OAA for the treatment of neurologic disorders but for reasons different from ours. One alternative rationale is that because glutamate transaminates OAA to generate aspartate and α-ketoglutarate in a reaction catalyzed by glutamate-OAA transaminase, increasing OAA could reduce brain glutamate. This putative mechanism would not necessarily require OAA to access the brain, if reduced blood glutamate caused glutamate to transfer from brain to blood [34-39]. At the doses of OAA we tested MRS-measured brain Glu and Glx levels did not change.

GSH did change, but since we lacked a placebo group and the low and high dose interventions did not run concurrently, it is necessary to consider whether drift or noise in the GSH measurements inflated the high dose post-treatment values. Data in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2 suggest this did not happen. The high dose baseline values, while not statistically different from the low dose baseline values, trend lower rather than higher. This argues strongly against an artifact-inducing, time-dependent upward calibration shift during the high dose trial period.

Reflective of our FDG PET data, the low dose associated with declining GSH while the high dose associated with increased GSH. This could indicate the low dose was functionally insufficient. If correct, longitudinal decline in the low dose group was not caused by OAA, but rather represents the disease’s natural history. As a biological alternative, we cannot rule out the possibility that the low dose of OAA shifted bioenergetic metabolism in a fundamentally different way than the high dose. For example, yeast that transition from anaerobic to aerobic environments switch from fermentation to oxidative metabolism; this is known as the Pasteur Effect [40]. Whether the human brain demonstrates similar metabolic swings exceeds the scope of this trial.

In the brain, the antioxidant GSH mostly exists in its reduced form and its MRS signal primarily detects the reduced species [41-43]. Elevations in the higher dose group suggest this intervention increased GSH synthesis, reduced free radical production, or reduced oxidative stress through some other mechanism. Malate generated through reduction of cytosolic OAA by MDH1 could provide substrate for the NADP-malic enzyme catalyzed reaction that produces pyruvate and NADPH, thereby increasing NADPH. NADPH could in turn facilitate conversion of oxidized GSH to reduced GSH. Alternatively, cytosolic GSH synthesis requires glutamate, cysteine, and glycine. An OAA-mediated Krebs cycle anaplerosis could evict glutamate from the mitochondria to the cytosol, and enhanced glycolysis flux should increase serine and through this glycine. An increase in GSH precursors could subsequently support its synthesis.

On cognitive tests the higher dose group did not change more than the lower dose group. This argues OAA does not adversely affect cognition, which is relevant from a safety perspective. For some participants post-treatment cognitive test scores improved relative to the pre-treatment scores obtained one month earlier, but post-treatment test score group means clearly did not improve at either dose. If OAA does have the ability to consistently improve AD patient function over a pre-existing baseline, it will require doses that exceed 1000 mg twice daily. Due to the very short duration of our study and lack of a placebo group, we can infer very little else about OAA’s ability to influence cognition in AD.

The TOAD did not proceed with two concomitant arms; we completed the low dose treatment part of the study before initiating the high dose treatment part. In the pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis, sample batches were run following the acquisition of an adequate number of samples. The majority of the high dose samples were, therefore, not run at the same time as the majority of the low dose samples. Profound differences in the absolute plasma levels likely reflect batch-related artifacts more than they reflect changes in the dose.

For our PK analysis, only the relative OAA/pyruvate ratio revealed a treatment-related plasma OAA increase. Several factors potentially contributed to our otherwise disappointing PK data. We assumed removing blood cells during the plasma isolation procedure would eliminate most OAA from the plasma, but this was not the case as baseline concentrations were high. Perhaps our plasma samples were contaminated by residual cells, rupture of blood cells occurred during phlebotomy or plasma isolation, or OAA is normally present at high levels in cell-free plasma. High background levels would diminish our ability to detect plasma changes. Further OAA PK analyses should consider a stricter attention to these details, and to running all samples together as opposed to running them in batches.

It is also possible a 500 or 1000 mg oral OAA dose is simply insufficient to appreciably raise the plasma level. Perhaps OAA is poorly absorbed, takes more than 90 minutes to absorb, or levels rise and fall within 60 minutes of ingestion. We selected 60 and 90-minute time points based on an earlier study in which 100 mg was administered [22], and it is possible we were misinformed by those data. Further OAA PK analyses should consider assessing additional time points.

Another study reported human PK data that showed a clear plasma increase 60 minutes after a 200 mg dose [23]. The author provided no information on method validation or analyte recovery, and concentrations were less than 3% of those determined in our study. Direct comparisons are therefore of little value.

Upon entering solution, some degree of spontaneous OAA decarboxylation is expected. Consuming OAA capsules did not increase the plasma pyruvate level. This indicates an extensive decarboxylation of OAA to pyruvate did not occur prior to absorption, or in blood following absorption. While monthly assessments of OAA integrity were performed on the batch from which the capsules derived, not the capsules themselves, batch stability over the study course suggests the capsules consumed by our subjects contained primarily OAA.

Despite our inability to show a reliable increase in plasma OAA following capsule consumption, changes in our biomarker endpoints suggest capsule OAA or a microbiome-generated derivative was absorbed. It is conceivable the intervention’s effects on the brain biomarkers were indirect, and unrelated to brain penetration, but the increase in GSH argues at least some OAA or an OAA derivative entered the brain.

Later stage AD trials increasingly assess brain amyloid (A) and occasionally tau (T) to verify participant diagnosis. We did not ascertain A-T status. We cannot assume every participant had AD, only that the majority did. We do not suspect this limitation voids our major findings that the evaluated OAA doses are safe over one month in persons with AD, and that it is possible to engage AD brain energy metabolism at a tolerable OAA dose. Three participants enrolled into both arms of the trial, but similarly we do not believe this voids our major findings.

We did not determine whether a dose-response relationship exists. Addressing this will require further studies at doses exceeding 1000 mg twice daily. Because the FDG PET and probably MRS biomarkers naturally change with disease progression, including a placebo group would also prove useful. Based strictly on the results of this study, though, it does appear OAA at a tolerated dose can influence AD patient brain energy metabolism.

Large phase 3 trials of drugs designed to inhibit beta amyloid production, prevent its aggregation, or remove plaques increasingly suggest these approaches will at best marginally slow decline and will not improve cognition [44]. Aggressively pursuing additional therapeutic targets gives the National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA) its best chance of meeting the stated goal of effectively treating AD by 2025 [45]. Manipulating bioenergetics to treat AD is not a new idea [1, 46-48], but efforts to develop interventions only recently began to account for target engagement [28, 31, 49-51]. This is the first time markers of brain energy metabolism were used to guide development of a unique, novel pharmacologic intervention specifically designed to alter AD bioenergetics. The TOAD demonstrates the feasibility of targeting brain energy metabolism to treat AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Alzheimer’s Association (PCTR-15-330495), and by the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center (P30AG035982). PK analyses were assisted by the University of Kansas Cancer Center (P30CA168524).

ABBREVIATIONS:

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAS-Cog

AD assessment scale-cognitive portion

- CBC

complete blood count

- Cho

choline

- Cr

creatine

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- CTU

clinical trials unit

- DLT

dose-limiting toxicity

- DMN

default mode network

- FDG PET

fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- F-P

frontoparietal

- Glx

glutamate+glutamine

- Glu

glutamate

- GSH

glutathione

- GM

gray matter

- KUMC

University of Kansas Medical Center

- Lac

lactate

- LFT

liver function test

- LMT

logical memory test

- MDH1

malate dehydrogenase 1

- mI

myo-inositol

- MPRAGE

magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo

- MR

magnetic resonance

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- MRSI

MR spectroscopic imaging

- NAA

N-acetyl aspartate

- NAPA

National Alzheimer’s Project Act

- OAA

oxaloacetate

- PVE

partial volume effects

- SD

standard deviation

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SUVR

standardized uptake value ratio

- SVS

single voxel MRS

- T

tesla

- t

total

- TOAD

Trial of OAA in AD

- WM

white matter

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Swerdlow RH. Treating neurodegeneration by modifying mitochondria: potential solutions to a "complex" problem. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].de Leon MJ, Ferris SH, George AE, Christman DR, Fowler JS, Gentes C, et al. Positron emission tomographic studies of aging and Alzheimer disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1983;4:568–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Silverman DH, Small GW, Chang CY, Lu CS, Kung De Aburto MA, Chen W, et al. Positron emission tomography in evaluation of dementia: Regional brain metabolism and long-term outcome. Jama. 2001;286:2120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fukuyama H, Ogawa M, Yamauchi H, Yamaguchi S, Kimura J, Yonekura Y, et al. Altered cerebral energy metabolism in Alzheimer's disease: a PET study. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kish SJ, Bergeron C, Rajput A, Dozic S, Mastrogiacomo F, Chang LJ, et al. Brain cytochrome oxidase in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of neurochemistry. 1992;59:776–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Parker WD Jr., Parks J, Filley CM, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Electron transport chain defects in Alzheimer's disease brain. Neurology. 1994;44:1090–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mutisya EM, Bowling AC, Beal MF. Cortical cytochrome oxidase activity is reduced in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of neurochemistry. 1994;63:2179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hirai K, Aliev G, Nunomura A, Fujioka H, Russell RL, Atwood CS, et al. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21:3017–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Swerdlow RH. Mitochondria and cell bioenergetics: increasingly recognized components and a possible etiologic cause of Alzheimer's disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:1434–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Parker WD Jr., Filley CM, Parks JK. Cytochrome oxidase deficiency in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1990;40:1302–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gibson GE, Sheu KF, Blass JP, Baker A, Carlson KC, Harding B, et al. Reduced activities of thiamine-dependent enzymes in the brains and peripheral tissues of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Archives of neurology. 1988;45:836–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Swerdlow RH, Khan SM. A "mitochondrial cascade hypothesis" for sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Med Hypotheses. 2004;63:8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Swerdlow RH, Burns JM, Khan SM. The Alzheimer's disease mitochondrial cascade hypothesis: progress and perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1219–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Swerdlow RH. Bioenergetic medicine. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:1854–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Swerdlow RH. Bioenergetics and metabolism: a bench to bedside perspective. Journal of neurochemistry. 2016;139 Suppl 2:126–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wilkins HM, Koppel S, Carl SM, Ramanujan S, Weidling I, Michaelis ML, et al. Oxaloacetate enhances neuronal cell bioenergetic fluxes and infrastructure. Journal of neurochemistry. 2016;137:76–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wilkins HM, Harris JL, Carl SM, E L, Lu J, Eva Selfridge J, et al. Oxaloacetate activates brain mitochondrial biogenesis, enhances the insulin pathway, reduces inflammation and stimulates neurogenesis. Human molecular genetics. 2014;23:6528–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Choi IY, Lee P, Vidoni ED, Clutton J, Becker AM, Sherry E, et al. Effects of oxaloacetate treatments on cerebral antioxidant and neurochemical profile in patients with Alzheimer’s disease using in vivo metabolic neuroimaging. 2019:AAIC Annual Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Vidoni ED, Choi IY, Lee P, Clutton J, Becker AM, Sherry E, et al. Trial of oxaloacetate in Alzheimer’s disease (TOAD): Final results. Alzheimer's & dementia (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2019:AAIC Annual Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Vidoni ED, Clutton J, Becker AM, Bothwell R, Mahnken JD, Wilkins H, et al. Trial of oxaloacetate in Alzheimer’s disease (TOAD): Interim PDG-PET analysis. 2018:AAIC Annual Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- [21].McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr., Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2011;7:263–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Swerdlow RH, Bothwell R, Hutfles L, Burns JM, Reed GA. Tolerability and pharmacokinetics of oxaloacetate 100 mg capsules in Alzheimer's subjects. BBA clinical. 2016;5:120–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yoshikawa K. Studies on the anti-diabetic effect of sodium oxaloacetate. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1968;96:127–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lee CY, Choi IY, Lee P. Prospective frequency correction using outer volume suppression-localized navigator for MR spectroscopy and spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2018;80:2366–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Choi IY, Lee P, Hughes AJ, Denney DR, Lynch SG. Longitudinal changes of cerebral glutathione (GSH) levels associated with the clinical course of disease progression in patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23:956–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gonzalez-Escamilla G, Lange C, Teipel S, Buchert R, Grothe MJ. PETPVE12: an SPM toolbox for Partial Volume Effects correction in brain PET - Application to amyloid imaging with AV45-PET. Neuroimage. 2017;147:669–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Muller-Gartner HW, Links JM, Prince JL, Bryan RN, McVeigh E, Leal JP, et al. Measurement of radiotracer concentration in brain gray matter using positron emission tomography: MRI-based correction for partial volume effects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:571–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wilkins HM, Mahnken JD, Welch P, Bothwell R, Koppel S, Jackson RL, et al. A Mitochondrial Biomarker-Based Study of S-Equol in Alzheimer's Disease Subjects: Results of a Single-Arm, Pilot Trial. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2017;59:291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Macchi Z, Wang Y, Moore D, Katz J, Saperstein D, Walk D, et al. A multi-center screening trial of rasagiline in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Possible mitochondrial biomarker target engagement. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis & frontotemporal degeneration. 2015:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Statland JM, Moore D, Wang Y, Walsh M, Mozaffar T, Elman L, et al. Rasagiline for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A randomized, controlled trial. Muscle & nerve. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gejl M, Gjedde A, Egefjord L, Moller A, Hansen SB, Vang K, et al. In Alzheimer's Disease, 6-Month Treatment with GLP-1 Analog Prevents Decline of Brain Glucose Metabolism: Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2016;8:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tune L, Tiseo PJ, Ieni J, Perdomo C, Pratt RD, Votaw JR, et al. Donepezil HCl (E2020) maintains functional brain activity in patients with Alzheimer disease: results of a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:169–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Keller C, Kadir A, Forsberg A, Porras O, Nordberg A. Long-term effects of galantamine treatment on brain functional activities as measured by PET in Alzheimer's disease patients. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2011;24:109–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ruban A, Berkutzki T, Cooper I, Mohar B, Teichberg VI. Blood glutamate scavengers prolong the survival of rats and mice with brain-implanted gliomas. Invest New Drugs. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Teichberg VI, Cohen-Kashi-Malina K, Cooper I, Zlotnik A. Homeostasis of glutamate in brain fluids: an accelerated brain-to-blood efflux of excess glutamate is produced by blood glutamate scavenging and offers protection from neuropathologies. Neuroscience. 2009;158:301–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zlotnik A, Gurevich B, Tkachov S, Maoz I, Shapira Y, Teichberg VI. Brain neuroprotection by scavenging blood glutamate. Experimental neurology. 2007;203:213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zlotnik A, Sinelnikov I, Gruenbaum BF, Gruenbaum SE, Dubilet M, Dubilet E, et al. Effect of glutamate and blood glutamate scavengers oxaloacetate and pyruvate on neurological outcome and pathohistology of the hippocampus after traumatic brain injury in rats. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Marosi M, Fuzik J, Nagy D, Rakos G, Kis Z, Vecsei L, et al. Oxaloacetate restores the long-term potentiation impaired in rat hippocampus CA1 region by 2-vessel occlusion. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;604:51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Nagy D, Marosi M, Kis Z, Farkas T, Rakos G, Vecsei L, et al. Oxaloacetate decreases the infarct size and attenuates the reduction in evoked responses after photothrombotic focal ischemia in the rat cortex. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2009;29:827–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Krebs HA. The Pasteur effect and the relations between respiration and fermentation. Essays Biochem. 1972;8:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gu F, Chauhan V, Chauhan A. Glutathione redox imbalance in brain disorders. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. 2015;18:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ribas V, Garcia-Ruiz C, Fernandez-Checa JC. Glutathione and mitochondria. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2014;5:151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Mandal PK, Shukla D, Govind V, Boulard Y, Ersland L. Glutathione Conformations and Its Implications for in vivo Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2017;59:537–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mullane K, Williams M. Alzheimer's disease beyond amyloid: can the repetitive failures of amyloid-targeted therapeutics inform future approaches to dementia drug discovery? Biochem Pharmacol. 2020:113945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fargo KN, Aisen P, Albert M, Au R, Corrada MM, DeKosky S, et al. 2014 Report on the Milestones for the US National Plan to Address Alzheimer's Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:S430–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Blass JP, Gibson GE. Correlations of disability and biologic alterations in Alzheimer brain and test of significance by a therapeutic trial in humans. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2006;9:207–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Taylor MK, Sullivan DK, Mahnken JD, Burns JM, Swerdlow RH. Feasibility and efficacy data from a ketogenic diet intervention in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2018;4:28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Swerdlow R, Marcus DM, Landman J, Harooni M, Freedman ML. Brain glucose and ketone body metabolism in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Clin Res. 1989;37:461A. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Torosyan N, Sethanandha C, Grill JD, Dilley ML, Lee J, Cummings JL, et al. Changes in regional cerebral blood flow associated with a 45day course of the ketogenic agent, caprylidene, in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: Results of a randomized, double-blinded, pilot study. Experimental gerontology. 2018;111:118–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Neth BJ, Mintz A, Whitlow C, Jung Y, Solingapuram Sai K, Register TC, et al. Modified ketogenic diet is associated with improved cerebrospinal fluid biomarker profile, cerebral perfusion, and cerebral ketone body uptake in older adults at risk for Alzheimer's disease: a pilot study. Neurobiology of aging. 2020;86:54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Fortier M, Castellano CA, Croteau E, Langlois F, Bocti C, St-Pierre V, et al. A ketogenic drink improves brain energy and some measures of cognition in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2019;15:625–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.