Abstract

Insects are frequently infected with heritable bacterial endosymbionts. Endosymbionts have a dramatic impact on their host physiology and evolution. Their tissue distribution is variable with some species being housed intracellularly, some extracellularly and some having a mixed lifestyle. The impact of extracellular endosymbionts on the biofluids they colonize (e.g. insect hemolymph) is however difficult to appreciate because biofluid composition can depend on the contribution of numerous tissues. Here we investigate Drosophila hemolymph proteome changes in response to the infection with the endosymbiont Spiroplasma poulsonii. S. poulsonii inhabits the fly hemolymph and gets vertically transmitted over generations by hijacking the oogenesis in females. Using dual proteomics on infected hemolymph, we uncovered a weak, chronic activation of the Toll immune pathway by S. poulsonii that was previously undetected by transcriptomics-based approaches. Using Drosophila genetics, we also identified candidate proteins putatively involved in controlling S. poulsonii growth. Last, we also provide a deep proteome of S. poulsonii, which, in combination with previously published transcriptomics data, improves our understanding of the post-transcriptional regulations operating in this bacterium.

Introduction

Insects frequently harbor vertically transmitted bacterial symbionts living within their tissues, called endosymbionts [1]. Endosymbionts have a major impact on the host physiology and evolution as they provide ecological benefits such as the ability for the host to thrive on unbalanced diets [2], protection against viruses or parasites [3–6] or tolerance to heat [7]. A peculiar group of insect endosymbionts also directly affects their host reproduction. This group is taxonomically diverse and includes bacteria from the Wolbachia, Spiroplasma, Arsenophonus, Cardinium and Rickettsia genera [8,9]. Four reproduction-manipulative mechanisms have been unraveled so far, namely cytoplasmic incompatibility, male-killing, parthenogenesis and male feminization [10], all of them leading to an evolutionary drive that favors infected individuals over non-infected ones and promotes the endosymbiont spread into populations. Their ease of spread coupled with the virus-protecting ability of some species [3,4] make them promising tools to control insect pest populations or to render them refractory to human arboviruses [11]. Reproductive manipulators are however fastidious bacteria that are difficult to manipulate, hence slowing down research on the functional aspects of their interaction with their hosts [12]. Their real impact on host physiology thus remains largely elusive.

Spiroplasma are long helical bacteria belonging to the Mollicutes class, which are devoid of cell wall [13]. They infect a wide range of arthropods and plants where they act as pathogens, commensals or vertically transmitted endosymbionts depending on the species [13]. S. poulsonii (hereafter Spiroplasma) is a vertically transmitted endosymbiont infecting the fruit fly Drosophila [14,15]. It lives free in the host hemolymph where it feeds on circulating lipids [16] and achieves vertical transmission by infecting oocytes [17]. Most strains cause male-killing, that is the death of the male progeny during early embryogenesis through the action of a toxin named Spaid [18]. Spiroplasma infection also confers protection to the fly or its larvae against major natural enemies such as parasitoid wasps [19,20] and nematodes [21,22].

Spiroplasma has long been considered as untractable, but recent technical advances such as the development of in vitro culture [23] and transformation [24] make it an emergent model for studying the functional aspects of insect-endosymbiont interactions. Some major steps have been made in the understanding of the male killing [25–28] and protection phenotypes [20,22,29] or on the way the bacterial titer was kept under control in the adult hemolymph [16,30]. Such studies, however, relied on single-gene studies and did not capture the full picture of the impact of Spiroplasma on its host physiology. We tackled this question using dual-proteomics on fly hemolymph infected by Spiroplasma. This non-targeted approach allowed us to get an extensive overview of the end-effect of Spiroplasma infection on the fly hemolymph protein composition and to identify previously unsuspected groups of proteins that where over- or under-represented in infected hemolymph. Using Drosophila genetics to knock-down the corresponding genes, we identified new putative regulators of the bacterial titer. This work also provides the most comprehensive Spiroplasma proteome to date. By comparing this proteome to the existing transcriptomics data, we draw conclusions about Spiroplasma post-transcriptional regulations.

Results

1. Drosophila hemolymph protein profiling

We investigated the effect of Spiroplasma infection on Drosophila hemolymph protein content using Liquid Chromatography-tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (S1 Fig). To this end, we extracted total hemolymph from uninfected and infected 10 days old females. At this age, Spiroplasma is already present at high titers in the hemolymph but does not cause major deleterious phenotypes to the fly [31,32]. Extraction was achieved by puncturing the thorax and drawing out with a microinjector. This procedure induces some tissue damage but recovers very few hemocytes (circulating immune cells).

Peptides were mapped to both the Drosophila and Spiroplasma predicted proteomes, hence allowing having an overview of i) differentially represented Drosophila proteins in infected versus uninfected hemolymph and ii) an in-depth Spiroplasma proteome in the infected hemolymph samples. These two datasets will be analyzed in separate sections.

The mapping on Drosophila proteome allowed the identification of 909 quantified protein groups (a protein group contains proteins that cannot be distinguished based on the identified peptides). The complete list of quantified Drosophila proteins and their fold-change upon Spiroplasma infection is available in S1 Table.

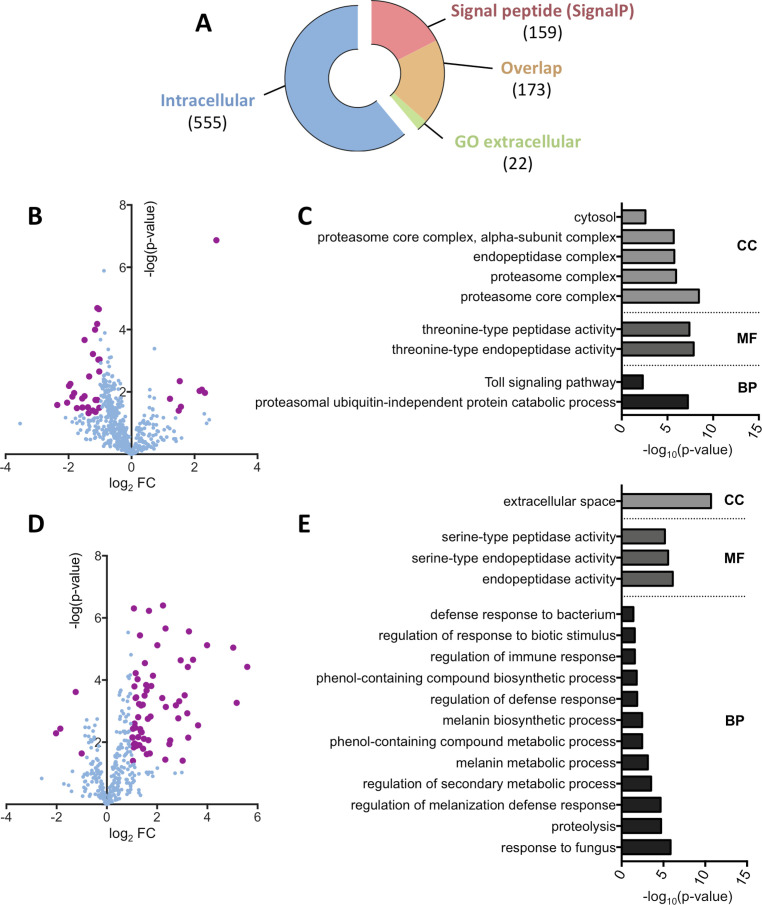

The hemolymph extraction process involves tissue damage (e.g. the subcuticular epithelium, muscles and fat body) that leads to the release of intracellular proteins in the sample. Hence we first sorted protein groups depending on whether the main protein is predicted to be extracellular or not. Proteins were defined as extracellular if they bore a predicted signal peptide or were annotated with a Gene Ontology (GO) term “extracellular”, or intracellular if no signal peptide nor any “extracellular” GO term was predicted. Based on this localization criteria the Drosophila dataset could be split in 555 intracellular protein groups representing 61% of the total proteome and 354 extracellular proteins representing the remaining 39% of the total proteome (Fig 1A).

Fig 1. Drosophila hemolymph protein profiling upon Spiroplasma infection.

(A) Representation of the dataset repartition between intracellular and extracellular protein groups. Extracellular groups are detected either by the presence of a predicted signal peptide using the SignalP algorithm or the annotation with a GO term referring to the extracellular space. The overlap category corresponds to protein groups with both a predicted signal peptide and a GO term “extracellular”. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of protein groups in each category. (B) Volcano plot of the intracellular protein group subset. The log2 fold-change indicates the differential representation of the protein group in the infected samples versus the uninfected samples. Bold purple dots indicate significance as defined by an absolute fold change value over 2 or under -2 and a p-value below 0.05. (C) Functional GO annotation of the intracellular protein groups. Only significant (p-value < 0.05) GO terms of hierarchy 4 or less are displayed. CC: Cell Component; MF: Molecular Function; BP: Biological Process. (D) Volcano plot of the extracellular protein group subset. The log2 fold-change indicates the differential representation of the protein group in the infected samples versus the uninfected samples. Bold purple dots indicate significance as defined by an absolute fold change value over 2 or under -2 and a p-value below 0.05. (E) Functional GO annotation of the extracellular protein groups. Only significant (p-value < 0.05) GO terms of hierarchy 4 or less are displayed. CC: Cell Component; MF: Molecular Function; BP: Biological Process.

We then compared the relative amounts of protein groups between infected and uninfected hemolymph. Of the intracellular protein groups, 35 were differentially represented in the Spiroplasma infected samples, including 8 overrepresented and 27 depleted groups compared to the uninfected control (Fig 1B). A functional GO analysis on the differentially represented protein groups revealed that a significant part of these protein groups were related to the proteasome (subunits α2, 3, 4 and 7 and subunits β3 and 6) and the Toll immune pathway (Fig 1C). The Toll pathway GO enrichment comprises only proteasome subunits, probably because of their involvement in the degradation of Toll pathway intermediates (e.g. Cactus [33]). While differentially abundant intracellular protein groups were mostly underrepresented in Spiroplasma infected hemolymph, analysis of the extracellular protein subset revealed an opposite trend. Among the 71 extracellular protein groups having a significantly different abundance, 4 were depleted and 67 were overrepresented in the infected samples compared to the uninfected ones (Fig 1D). Surprisingly, the functional GO annotation highlighted an overrepresentation of serine-endopeptidase molecular function. Serine proteases are involved in the regulation of the melanization and the Toll pathways and indeed the associated GO terms are enriched in the infected samples (Fig 1E).

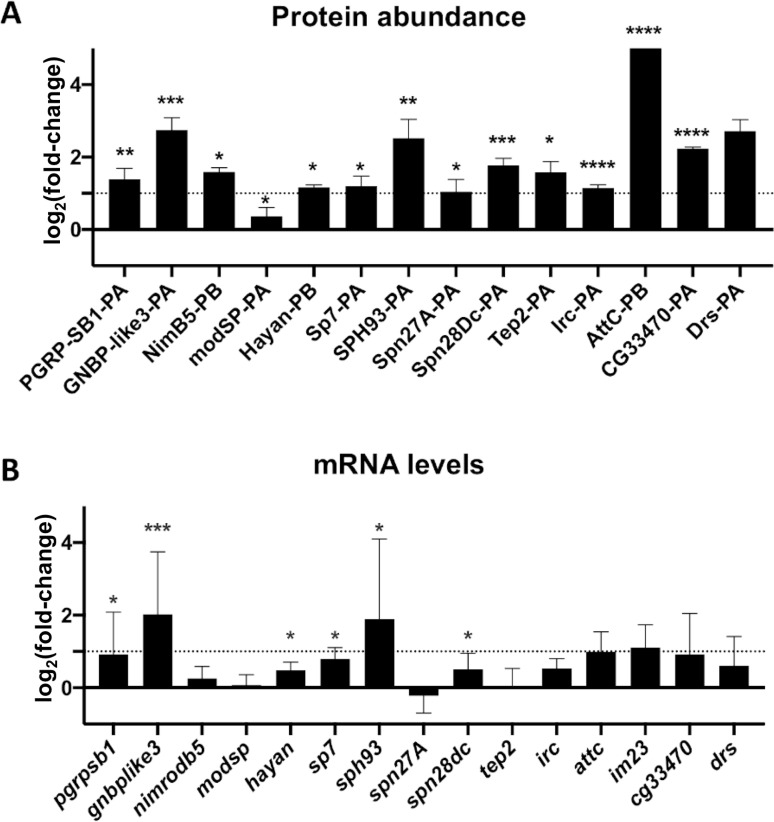

2. Immune-related protein enrichment is a consequence of a mild transcriptional activation

Since Spiroplasma is devoid of cell wall, it lacks microbe-associated molecular patterns such as peptidoglycan and is not expected to interact with pattern-recognition receptors regulating the fly immune system. This idea was supported by previous work showing that Spiroplasma do not trigger a strong level of Toll and Imd pathway, the two main immune pathways in Drosophila [31,34]. Previous work also showed that flies defective for the inducible humoral immune response have normal Spiroplasma titer, suggesting that immune pathways are not required to control Spiroplasma growth [31]. Our observation that several immune-related proteins are more abundant in the hemolymph of infected flies (Fig 2A and S1 Table) led us to investigate further on this point. We first tested if the changes in immune-related protein abundance were a consequence of altered gene expression. We measured the corresponding mRNA levels of several differentially represented proteins (Fig 2B). Immune-related genes were slightly upregulated in infected flies, although their induction levels did not compare with those observed after systemic infection by a pathogenic bacteria [35,36]. These results confirm that Spiroplasma does not trigger a strong immune response [31,34], but rather provokes a mild and chronic production of immunity proteins.

Fig 2. Spiroplasma infection induces a mild transcriptional immune response.

(A) Changes in a selection of immune-related protein group abundances quantified by LC-MS/MS. Data are expressed as fold change of the Label-Free Quantification (LFQ) values of Spiroplasma infected hemolymph over the uninfected control (log2 scale). *, p<0.05; ** p<0.005, ***; p<0.005, ****, p<0.0005 upon Student t-test. (B) mRNA quantification of a selection of candidate genes in uninfected and Spiroplasma-infected flies. Results are expressed as the fold change of target mRNA normalized by rpL32 mRNA in Spiroplasma-infected flies as compared to uninfected flies (log2 scale). *, p<0.05; ** p<0.005, ***; p<0.0005 upon Mann-Whitney test on ΔCt values. Each bar represents the mean +/- standard deviation of a pool of at least 2 independent experiments with 3 biological replicates each.

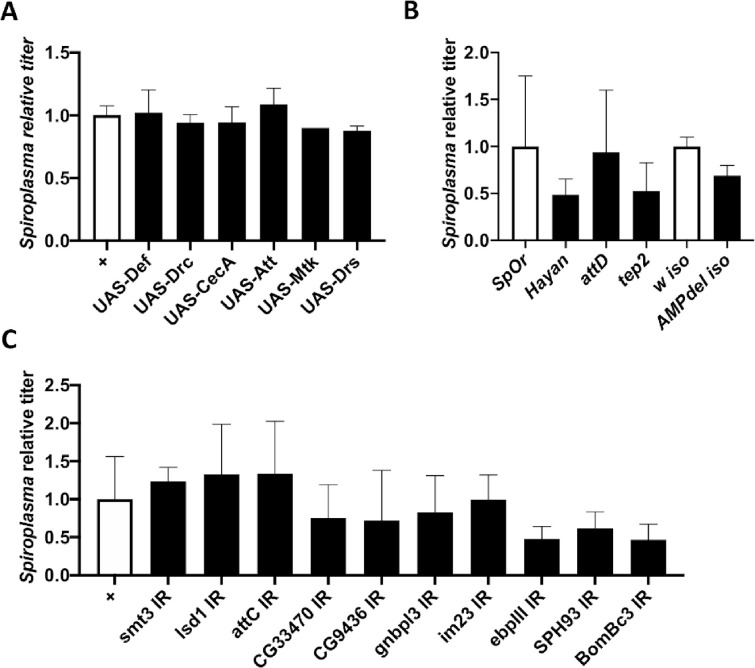

3. A majority of enriched hemolymphatic proteins are not involved in Spiroplasma growth control

A systemic infection or a genetic induction of the humoral immune response promotes Spiroplasma growth in flies [31]. We therefore wondered if the presence of small amounts of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) could be beneficial for Spiroplasma growth. To test this hypothesis, we measured Spiroplasma titer in flies over-expressing different AMP genes [37]. We found that AMP gene overexpression did not increase Spiroplasma titer (Fig 3A). Similarly, flies lacking ten AMP coding genes [38] had a Spiroplasma titer comparable to that of control flies (Fig 3B). These results suggest that AMPs released during the humoral immune response do not affect Spiroplasma growth.

Fig 3. Targeted genetic screening of candidate proteins.

(A-C) Quantification of Spiroplasma titer in two weeks old flies in various genetic backgounds. Titer is expressed as the fold-change over the appropriate control line. All graphs represent the mean +/- standard deviation of a pool of at least 2 independent experiments with 3 biological replicates each. (A) Control flies (Act5C-GAL4 driver crossed w1118, white bars) are compared to flies overexpressing a single antimicrobial peptide gene driven by the ubiquitous Act5C-GAL4 driver (black bars). Titer is expressed as the fold-change over control. (B) Quantification of Spiroplasma titer in wild-type flies (OregonR, white bar) and hayan, attD and tep2 null mutants (black). Spiroplasma titer in AMP10 iso flies were compared to that of their isogenic wild-type counterpart (w1118 iso, white bar). (C) Quantification of the impact of RNAi-mediated knockdown on Spiroplasma titer with the Act5C-GAL4 driver. Titer is expressed as the fold-change over the control (Act5C-GAL4 driver crossed to w1118).

We then tested if other immune-related proteins found more abundant in infected hemolymph could alter Spiroplasma growth. We first compared the Spiroplasma titers of control OregonR flies with that of hayan, attD and tep2 mutants. We observed no difference in bacterial titer, indicating that these genes are not required neither detrimental to Spiroplasma growth (Fig 3B). We then used an in vivo RNAi approach to silence immune genes coding for the most enriched proteins in Spiroplasma-infected flies using the ubiquitously expressed Act5C-GAL4 driver. Silencing these genes did not provoke an increase in Spiroplasma titer, further reinforcing the idea that immune proteins do not prevent Spiroplasma growth (Fig 3C).

Among the most differentially represented proteins in Spiroplasma infected hemolymph, we also detected several proteins of unknown function. To test their role in Spiroplasma growth control, we used the same RNAi-mediated knockdown approach and quantified Spiroplasma titer in these flies. Most of the RNAi lines tested showed no change in Spiroplasma titer as compared to control lines (S2 Fig). Two RNAi lines targeting CG18067 and CG14762, respectively, showed a slight yet not significant reduction in Spiroplasma titer. These results suggest that all the tested genes do not facilitate Spiroplasma growth nor control its titer. Instead, these proteins are likely to be induced as a consequence of Spiroplasma infection and may participate in the host adaptation to the bacteria. A mutant line was available for only one of the most enriched uncharacterized proteins (CG15293). We found that this mutation leads to a significant increase in bacteria titer (S2 Fig). This gene codes for a 37 kDa secreted protein with no known function. Our results raised the hypothesis that CG15293 participates in the control of Spiroplasma titer in vivo.

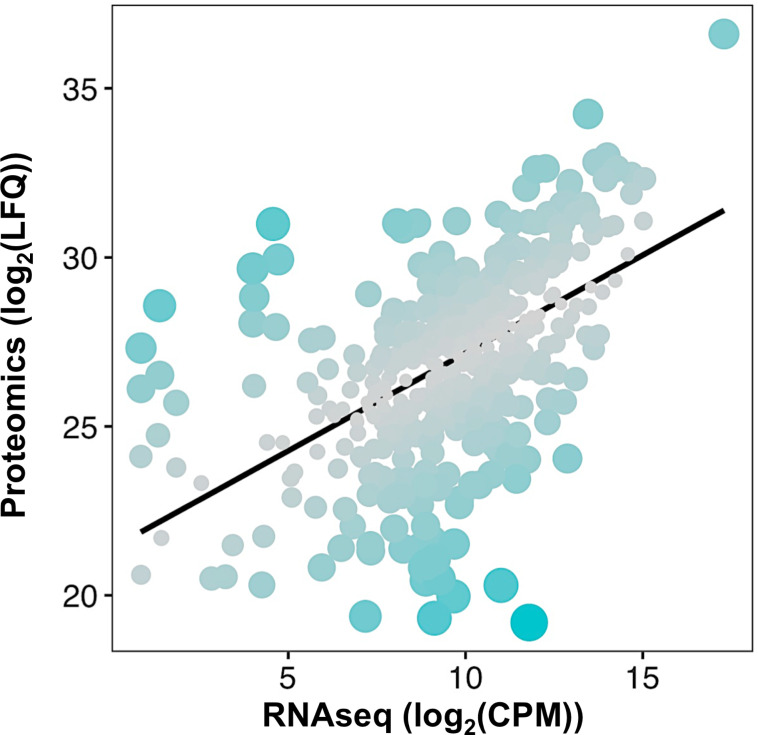

4. Transcriptome-proteome correlation in Spiroplasma poulsonii

The proteomics analysis of infected hemolymph samples also allowed the detection and quantification of Spiroplasma proteins. With a total of 503 proteins, this is the most comprehensive Spiroplasma proteome to date. The complete list of Spiroplasma quantified proteins is available in S2 Table.

We took advantage of a previously published transcriptomics dataset of Spiroplasma [23] to compare the expression level of Spiroplasma genes to their corresponding protein abundance by building a linear model of the proteomics signal as a function of the transcript level (Fig 4). The two measures are poorly correlated (Kendall’s τ = 0.40). Analyzing the normalized residuals of the model also allowed us to identify proteins that are particularly discrepant with the model, that is with absolute standardized residuals greater than 2. This approach uncovered 27 proteins, of which 11 have a significantly higher abundance and 16 a lower abundance in the proteome than what was predicted from the transcriptomics data (S3 Table). Over-represented proteins with a reliable annotation include the membrane lectin Spiralin B, the cytoskeletal protein Fibrilin, the glucose transporter Crr, the potassium channel KtrA, a ferritin-like protein Ftn, the chromosome partitioning protein ParA and the DNA polymerase subunit DnaN. Under-represented proteins include the transporters SteT and YdcV, the serine/threonine phosphatase Stp, the helicase PcrA, the ATP synthase subunit AtpH, the GMP reductase GuaC and the tRNA-(guanine-N(7)-)-methyltransferase TrmB. Other proteins have no predicted function.

Fig 4. Spiroplasma transcription-translation correlation.

Each dot represents a protein positioned according to its log2(LFQ; Label-free Quantification) value in the proteome versus its log2(CPM; Count Per Million) in the transcriptomics dataset from [23]. The black line represents the linear model log2(LFQ) = 0.57892 x log2(CPM) + 21.38325, with an adjusted R2 = 0.2909. Dot size and color are adjusted to the residuals of the model, with bigger bluer dots indicating a higher residual hence a stronger deviation from the linear model for the considered protein.

Discussion

This study provides an extensive characterization of the proteome of Spiroplasma-infected Drosophila hemolymph. This dual-proteomics approach provides a deep proteome of Spiroplasma in its natural environment and pinpoints host proteins which abundance is altered by the presence of the bacteria. The power of Drosophila genetics allowed us to test the involvement of these candidate genes in regulating endosymbiosis. A targeted genetic screen revealed that most of the differentially abundant proteins upon Spiroplasma infection do not participate in the control of symbiont growth but may rather be involved in host adaptation to Spiroplasma.

Spiroplasma is devoid of cell wall, hence devoid of peptidoglycan, which is the main immune elicitor for the insect immune system [39]. This led to the assumption that Spiroplasma was undetectable by the canonical innate immune pathways. Furthermore, the elicitation of the fly immune system (by an infection or using genetics) has no impact on Spiroplasma titer, suggesting that the bacteria are not only invisible by also resistant to the fly immune effectors [31]. Flies that over-express AMPs and the ΔAMP10 mutant line have normal bacterial titer that confirms the host immune system does not affect Spiroplasma growth. However, numerous immune-related proteins (mostly associated to the Toll pathway) were enriched in Spiroplasma infected hemolymph, including receptors or putative receptors (GNBP1, GNBP-like3), signal transduction intermediates (Spätzle-Processing Enzyme and Hayan) and effectors or putative effectors (Attacin, Bomanin Bc3 and CG33470). The Spiroplasma titer was not altered in several fly lines carrying loss-of function alleles of these genes, indicating that the immune elicitation is a consequence of the infection but not a control mechanism. It is worth noting that the expression levels of the genes were extremely low as compared to a fully-fledged immune response against pathogenic bacteria [35]. Such low induction of the immune response has been reported in flies experiencing stress, such as cold or heat stress [40,41]. Therefore, the mild induction of immune proteins in infected hemolymph may be an unspecific stress response associated to the presence of bacteria. Another attractive hypothesis would be that proteases released by Spiroplasma could trigger the soluble sensor Persephone and activate the Toll pathway in a peptidoglycan-independent fashion [42,43].

Another uncovering of this study is the depletion of proteasome components in the hemolymph upon Spiroplasma infection. As the ubiquitin-proteasome system is a major degradation pathway for intracellular proteins [44], the components that we detected in the hemolymph are presumably released from cells that broke upon hemolymph collection (epithelial, fat or muscular cells, but also possibly hemocytes). However, functionally active 20S proteasome units have been discovered circulating in extracellular fluids in mammals, including serum [45] hence we cannot exclude the existence of circulating proteasome units in Drosophila hemolymph. Host ubiquitin-proteasome systems have long been suspected to be a key element in symbiotic homeostasis. It is upregulated in cells harboring intracellular symbionts in weevils, presumably to increase protein turnover and provide free amino-acids to the bacteria [46]. In vitro work on cell cultures infected by the facultative endosymbiont Wolbachia also revealed that it induces the host proteasome presumably also to support its own growth [47–49]. Remarkably, one proteasome subunit was detected as enriched upon Spiroplasma infection in the aphid Aphis citricidus when the insect was feeding on a suboptimum but not on an optimum host plant, suggesting an interaction between symbiosis, nutrition and the proteasome-ubiquitin degradation system [50]. In the case of Drosophila-Spiroplasma interaction, the depletion of proteasome subunits upon infection could thus be a titer regulation mechanism: by decreasing its proteolysis, the host would limit the release of amino acids in the extracellular space that would be usable by Spiroplasma.

Our approach also produced an in-depth Spiroplasma proteome on total proteins regardless of their cell localization. This gives a quantitatively unbiased overview of each protein abundance which was not achieved by previous data based on detergent extractions [30]. Such quantitative approach allowed us to make a comparison between the transcript and protein levels on about one fourth of the total number of predicted coding sequences [23]. Although the correlation between transcriptomics and proteomics data greatly varies among models, tissues and experimental set-ups [51], our data indicate a rather low correlation in the case of Spiroplasma. The correlations between transcript and protein levels depends on the interaction between transcript stability and protein stability [52]. It also depends on the intrinsic chemical properties of each transcript that affect the ribosome binding or the translation speed, for example the Shine-Dalgarno sequence in prokaryotes [53] or more importantly the codon adaptation index of the coding sequence [54]. An explanation for the overall lack of correlation between transcripts and proteins regardless of the model could be that selection operates at the protein level, hence changes in mRNA levels would be offset by post-transcriptional mechanisms to maintain stable protein levels over evolutionary times [55]. This hypothesis entails that genes having a low mRNA level compared to their protein levels are likely to be under strong selective pressure to maintain high protein abundancy through post-transcriptional regulations. Intriguingly, this is the case for S. poulsonii Spiralin B, a protein homologous to the S. citri Spiralin A, a membrane lectin suspected to be essential for insect to plant transmission [56,57]. Spiralin B has been identified as a putative virulence factor in S. poulsonii as it is upregulated when the bacteria are in the fly hemolymph compared to in vitro culture [23] and could be involved in oocyte infection for vertical transmission. Similarly, the Crr glucose transporter has an unexpectedly high protein/mRNA ratio, possibly in connection with its role in bacteria survival in the hemolymph. Spiroplasma has a pseudogenized transporter for trehalose, the most abundant sugar in the hemolymph [30]. This could have been selected over host-symbiont coevolution to prevent Spiroplasma overgrowth, hence increasing the stability of the interaction by limiting the metabolic cost of harboring the bacteria. Maintaining high Crr levels could thus be an offset response to maintain bacteria proliferation despite trehalose inaccessibility. Last, the ferritin-like protein Ftn has also a bias towards high protein abundancy, suggesting that iron could be a key metabolite in Spiroplasma-Drosophila symbiotic homeostasis.

All tissues bathed by hemolymph contribute to its composition. As a consequence, studying the impact of symbionts on this biofluid is unapproachable by transcriptomic methods only. Dual proteomics proved to be an efficient approach to overcome this hurdle and gain novel insights into the Drosophila-Spiroplasma symbiosis. This method is also promising for the study of other symbioses, particularly those where symbionts inhabit biofluids rather than cells.

Material and methods

Spiroplasma and Drosophila stocks

Flies were kept at 25°C on cornmeal medium (35.28 g of cornmeal, 35.28 g of inactivated yeast, 3.72 g of agar, 36 ml of fruits juice, 2.9 ml of propionic acid and 15.9 ml of Moldex for 600 ml of medium). The complete list of fly stocks is available in S4 Table.

Spiroplasma poulsonii strain Uganda-1 [58] was used for all infections. Fly stocks were infected as previously described [31]. Briefly, 9 nL of Spiroplasma-infected hemolymph was injected in their thorax. The progeny of these flies was collected after 5–7 days using male killing as a proxy to assess the infection (100% female progeny). Flies from at least the 3rd generation post-injection were used experimentally.

Hemolymph extraction procedure

Embryos were collected from conventionally reared flies and dechorionated using a bleach-based previously published method [59] to ensure that they were devoid of horizontally transmitted pathogens. One generation was then left to develop in conventional rearing conditions to allow for gut microbiota recontamination. Hemolymph was extracted from 10 days-old flies from the second generation after bleach treatment using a Nanoject II (Drummond) as previously described [16]. 1 μL of hemolymph was collected for each sample and frozen at -80°C until further use. Hemolymph was then diluted 10 times with PBS containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail 1X (Roche). 1 μl was used for protein quantification with the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermofisher). The remaining 9 μl were mixed with SDS (0.2% final), DTT (2.5mM final) and PMSF (10μM final). Aliquots of 15 μg were used for proteomics analysis.

Proteomics sample preparation and LC-MS/MS

Sample preparation and data analysis was carried out at the Proteomics Core Facility of EPFL. Each sample was digested by Filter Aided Sample Preparation (FASP) [60] with minor modifications. Dithiothreitol (DTT) was replaced by Tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) as reducing agent and iodoacetamide by chloracetamide as alkylating agent. A proteolytic digestion was performed using Endoproteinase Lys-C and Trypsin. Peptides were desalted on C18 StageTips [61] and dried down by vacuum centrifugation. For LC-MS/MS analysis, peptides were resuspended and separated by reversed-phase chromatography on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 RSLC nanoUPLC system in-line connected with an Orbitrap Q Exactive HF Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific). Database search was performed using MaxQuant 1.5.1.2 [62] against a concatenated database consisting of the Ensemble Drosophila melanogaster protein database (BDGP5.25) and a custom Spiroplama poulsonii proteome predicted from the reference genome (Genbank accession number JTLV00000000.2). Carbamidomethylation was set as fixed modification, whereas oxidation (M) and acetylation (Protein N-term) were considered as variable modifications. Label-free quantification was performed by MaxQuant using the standard settings. Hits were considered significant when the fold-change between infected and uninfected hemolymph was >2 or <-2 and the FDR<0.05.

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD024340.

Spiroplasma quantification

Spiroplasma quantification was performed by qPCR as previously described [32]. Briefly, the DNA of pools of 5 whole flies was extracted and the copy number of a single-copy bacterial gene (dnaA or dnaK) was quantified and normalized by that of the host gene rsp17. Primers sequences are available in S4 Table. Each experiment has been repeated 2 or 3 independent times with at least 3 biological replicates each. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

RT-qPCR

Gene expression measurements were performed by RT-qPCR as previously described [63,64]. Briefly, 10 whole flies were crushed and their RNA extracted with the Trizol method. Reverse transcription was carried out using a PrimeScript RT kit (Takara) and a mix of random hexamers and oligo-dTs. qPCR was performed on a QuantStudio 3 (Applied Biosystems) with PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix using primer sequences available in S4 Table. The expression of the target gene was normalized by that of the housekeeping gene rp49 (rpL32) using the 2-ΔΔCT method [65].

Each experiment has been repeated 2 or 3 independent times with at least 3 biological replicates each. Data were analyzed by Mann-Whitney tests.

Supporting information

(TIF)

(A) Quantification of Spiroplasma titer in two weeks old flies. Titer is expressed as the fold-change of Act5C-GAL4>UAS-RNAi over Act5C-GAL4> w1118. Bars represent the mean +/- standard deviation of a pool of at least 2 independent experiments. (B) Quantification of Spiroplasma titer in CG15293 mutant flies compared to control yw flies. Bars represent the mean +/- standard deviation of a pool of at least 3 independent experiments. ***; p<0.0005 upon Mann-Whitney test on ΔΔCt values.

(TIF)

(CSV)

(CSV)

(CSV)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Florence Armand, Romain Hamelin and the EPFL Proteomics Core Facility for sharing their expertise on proteomics.

Data Availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD024340.

Funding Statement

BL - Swiss National Science Foundation grant N°310030_185295. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Douglas AE. Multiorganismal Insects: Diversity and Function of Resident Microorganisms. Annu Rev Entomol. 2015;60: 17–34. 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Douglas AE. How multi-partner endosymbioses function. Nat Rev Microbiol. Nature Publishing Group; 2016;14: 731–743. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teixeira L, Ferreira A, Ashburner M. The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 2009/02/19. 2008;6: e2. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O’Neill SL, Johnson KN. Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science (80-). 2008/11/01. 2008;322: 702. 10.1126/science.1162418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver KM, Russell JA, Moran NA, Hunter MS. Facultative bacterial symbionts in aphids confer resistance to parasitic wasps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003/02/04. 2003;100: 1803–1807. 10.1073/pnas.0335320100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scarborough CL, Ferrari J, Godfray HC. Aphid protected from pathogen by endosymbiont. Science (80-). 2005/12/17. 2005;310: 1781. 10.1126/science.1120180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montllor CB, Maxmen A, Purcell AH. Facultative bacterial endosymbionts benefit pea aphids Acyrthosiphon pisum under heat stress. Ecol Entomol. 2002;27: 189–195. 10.1046/j.1365-2311.2002.00393.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medina P, Russell SL, Corbett-Detig R. Deep data mining reveals variable abundance and distribution of microbial reproductive manipulators within and among diverse host species. bioRxiv. 2019; 679837. 10.1101/679837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duron O, Bouchon D, Boutin S, Bellamy L, Zhou L, Engelstadter J, et al. The diversity of reproductive parasites among arthropods: Wolbachia do not walk alone. BMC Biol. 2008/06/26. 2008;6: 27. 10.1186/1741-7007-6-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6: 741–751. 10.1038/nrmicro1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann AA, Montgomery BL, Popovici J, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Johnson PH, Muzzi F, et al. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature. 2011;476: 454. 10.1038/nature10356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masson F, Lemaitre B. Growing Ungrowable Bacteria: Overview and Perspectives on Insect Symbiont Culturability. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2020;84: e00089–20. 10.1128/MMBR.00089-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasparich GE. Spiroplasmas: evolution, adaptation and diversity. Front Biosci. 2002;7: 619–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haselkorn TS. The Spiroplasma heritable bacterial endosymbiont of Drosophila. Fly (Austin). 2010;4: 80–87. 10.4161/fly.4.1.10883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mateos M, Castrezana SJ, Nankivell BJ, Estes AM, Markow TA, Moran NA. Heritable Endosymbionts of Drosophila. Genetics. 2006;174: 363–376. 10.1534/genetics.106.058818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herren JK, Paredes JC, Schüpfer F, Arafah K, Bulet P, Lemaitre B. Insect endosymbiont proliferation is limited by lipid availability. Elife. 2014;3: e02964. 10.7554/eLife.02964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herren JK, Paredes JC, Schüpfer F, Lemaitre B. Vertical Transmission of a Drosophila Endosymbiont Via Cooption of the Yolk Transport and Internalization Machinery. MBio. 2013;4 (2): e00532–12. 10.1128/mBio.00532-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harumoto T, Lemaitre B. Male-killing toxin in a bacterial symbiont of Drosophila. Nature. Springer US; 2018;557: 252–255. 10.1038/s41586-018-0086-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie J, Butler S, Sanchez G, Mateos M. Male killing Spiroplasma protects Drosophila melanogaster against two parasitoid wasps. Heredity; 2014;112: 399–408. 10.1038/hdy.2013.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballinger MJ, Perlman SJ. Generality of toxins in defensive symbiosis: Ribosome-inactivating proteins and defense against parasitic wasps in Drosophila. Hurst G, editor. PLoS Pathog; 2017;13: e1006431. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaenike J, Unckless R, Cockburn SN, Boelio LM, Perlman SJ. Adaptation via symbiosis: recent spread of a Drosophila defensive symbiont. Science 2010;329: 212–215. 10.1126/science.1188235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton PT, Peng F, Boulanger MJ, Perlman SJ. A ribosome-inactivating protein in a Drosophila defensive symbiont. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. National Academy of Sciences; 2016;113: 350–355. 10.1073/pnas.1518648113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masson F, Calderon Copete S, Schüpfer F, Garcia-Arraez G, Lemaitre B. In Vitro Culture of the Insect Endosymbiont Spiroplasma poulsonii Highlights Bacterial Genes Involved in Host-Symbiont Interaction. MBio. 2018;9(2): e00024–18. 10.1128/mBio.00024-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masson F, Schüpfer F, Jollivet C, Lemaitre B. Transformation of the Drosophila sex-manipulative endosymbiont Spiroplasma poulsonii and persisting hurdles for functional genetics studies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2020; AEM.00835-20. 10.1128/AEM.00835-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veneti Z, Bentley JK, Koana T, Braig HR, Hurst GDD. A Functional Dosage Compensation Complex Required for Male Killing in Drosophila. Science 2005;307: 1461–1463. 10.1126/science.1107182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harumoto T, Anbutsu H, Fukatsu T. Male-killing Spiroplasma induces sex-specific cell death via host apoptotic pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10: e1003956. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harumoto T, Anbutsu H, Lemaitre B, Fukatsu T. Male-killing symbiont damages host’s dosage-compensated sex chromosome to induce embryonic apoptosis. Nat Commun. Nature Publishing Group; 2016;7: 12781. 10.1038/ncomms12781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harumoto T, Fukatsu T, Lemaitre B. Common and unique strategies of male killing evolved in two distinct Drosophila symbionts. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2018;285. 10.1098/rspb.2017.2167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paredes JC, Herren JK, Schüpfer F, Lemaitre B. The Role of Lipid Competition for Endosymbiont-Mediated Protection against Parasitoid Wasps in Drosophila. MBio. 2016;7(4): e01006–16. 10.1128/mBio.01006-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paredes JC, Herren JK, Schüpfer F, Marin R, Claverol S, Kuo C-H, et al. Genome sequence of the Drosophila melanogaster male-killing Spiroplasma strain MSRO endosymbiont. MBio. 2015;6(2): e02437–14. 10.1128/mBio.02437-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herren JK, Lemaitre B. Spiroplasma and host immunity: Activation of humoral immune responses increases endosymbiont load and susceptibility to certain Gram-negative bacterial pathogens in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13: 1385–1396. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01627.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masson F, Calderon-Copete S, Schüpfer F, Vigneron A, Rommelaere S, Garcia-Arraez MG, et al. Blind killing of both male and female Drosophila embryos by a natural variant of the endosymbiotic bacterium Spiroplasma poulsonii. Cell Microbiol. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2020;22(5): e13156. 10.1111/cmi.13156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palombella VJ, Rando OJ, Goldberg AL, Maniatis T. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is required for processing the NF-kappa B1 precursor protein and the activation of NF-kappa B. Cell. United States; 1994;78: 773–785. 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90482-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurst GDD, Anbutsu H, Kutsukake M, Fukatsu T. Hidden from the host: Spiroplasma bacteria infecting Drosophila do not cause an immune response, but are suppressed by ectopic immune activation. Insect Mol Biol. 2003;12: 93–97. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00380.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Gregorio E, Spellman PT, Rubin GM, Lemaitre B. Genome-wide analysis of the Drosophila immune response by using oligonucleotide microarrays. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2001;98: 12590–12595. 10.1073/pnas.221458698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Troha K, Im JH, Revah J, Lazzaro BP, Buchon N. Comparative transcriptomics reveals CrebA as a novel regulator of infection tolerance in D. melanogaster. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14: e1006847. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tzou P, Reichhart J-M, Lemaitre B. Constitutive expression of a single antimicrobial peptide can restore wild-type resistance to infection in immunodeficient Drosophila mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99: 2152–2157. 10.1073/pnas.042411999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanson MA, Dostálová A, Ceroni C, Poidevin M, Kondo S, Lemaitre B. Synergy and remarkable specificity of antimicrobial peptides in vivo using a systematic knockout approach. Elife. eLife Sciences Publications, Ltd; 2019;8: e44341. 10.7554/eLife.44341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007/01/05. 2007;25: 697–743. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacMillan HA, Knee JM, Dennis AB, Udaka H, Marshall KE, Merritt TJS, et al. Cold acclimation wholly reorganizes the Drosophila melanogaster transcriptome and metabolome. Sci Rep. 2016;6: 28999. 10.1038/srep28999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Telonis-Scott M, van Heerwaarden B, Johnson TK, Hoffmann AA, Sgrò CM. New Levels of Transcriptome Complexity at Upper Thermal Limits in Wild Drosophila Revealed by Exon Expression Analysis. Genetics. 2013;195: 809–830. 10.1534/genetics.113.156224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Issa N, Guillaumot N, Lauret E, Matt N, Schaeffer-Reiss C, Van Dorsselaer A, et al. The Circulating Protease Persephone Is an Immune Sensor for Microbial Proteolytic Activities Upstream of the Drosophila Toll Pathway. Mol Cell. Cell Press; 2018;69: 539–550.e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gottar M, Gobert V, Matskevich AA, Reichhart J-M, Wang C, Butt TM, et al. Dual detection of fungal infections in Drosophila via recognition of glucans and sensing of virulence factors. Cell. 2006;127: 1425–1437. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kleiger G, Mayor T. Perilous journey: a tour of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24: 352–359. 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sixt SU, Dahlmann B. Extracellular, circulating proteasomes and ubiquitin—Incidence and relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta—Mol Basis Dis. 2008;1782: 817–823. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heddi A, Vallier A, Anselme C, Xin H, Rahbe Y, Wackers F. Molecular and cellular profiles of insect bacteriocytes: mutualism and harm at the initial evolutionary step of symbiogenesis. Cell Microbiol. 2005/01/22. 2005;7: 293–305. doi:CMI461 [pii] 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00461.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fallon AM, Witthuhn BA. Proteasome activity in a naïve mosquito cell line infected with Wolbachia pipientis wAlbB. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2009;45: 460–466. 10.1007/s11626-009-9193-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White PM, Serbus LR, Debec A, Codina A, Bray W, Guichet A, et al. Reliance of Wolbachia on High Rates of Host Proteolysis Revealed by a Genome-Wide RNAi Screen of Drosophila Cells. Genetics. 2017;205: 1473–1488. 10.1534/genetics.116.198903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He Z, Zheng Y, Yu W-J, Fang Y, Mao B, Wang Y-F. How do Wolbachia modify the Drosophila ovary? New evidences support the “titration-restitution” model for the mechanisms of Wolbachia-induced CI. BMC Genomics. 2019;20: 608. 10.1186/s12864-019-5977-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guidolin AS, Cataldi TR, Labate CA, Francis F, Cônsoli FL. Spiroplasma affects host aphid proteomics feeding on two nutritional resources. Sci Rep. 2018;8: 2466. 10.1038/s41598-018-20497-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haider S, Pal R. Integrated analysis of transcriptomic and proteomic data. Curr Genomics. 2013;14: 91–110. 10.2174/1389202911314020003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwanhäusser B, Busse D, Li N, Dittmar G, Schuchhardt J, Wolf J, et al. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature. 2011;473: 337–342. 10.1038/nature10098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bingham AH, Ponnambalam S, Chan B, Busby S. Mutations that reduce expression from the P2 promoter of the Escherichia coli galactose operon. Gene. 1986;41: 67–74. 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90268-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lithwick G, Margalit H. Hierarchy of sequence-dependent features associated with prokaryotic translation. Genome Res. 2003;13: 2665–2673. 10.1101/gr.1485203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schrimpf SP, Weiss M, Reiter L, Ahrens CH, Jovanovic M, Malmström J, et al. Comparative Functional Analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster Proteomes. PLOS Biol. 2009;7: e1000048. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Killiny N, Castroviejo M, Saillard C. Spiroplasma citri Spiralin acts in vitro as a lectin binding to glycoproteins from its insect vector Circulifer haematoceps. Phytopathology. 2005;95: 541–548. 10.1094/PHYTO-95-0541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duret S, Berho N, Danet JL, Garnier M, Renaudin J. Spiralin is not essential for helicity, motility, or pathogenicity but is required for efficient transmission of Spiroplasma citri by its leafhopper vector Circulifer haematoceps. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69: 6225–6234. 10.1128/aem.69.10.6225-6234.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pool JE, Wong a, Aquadro CF. Finding of male-killing Spiroplasma infecting Drosophila melanogaster in Africa implies transatlantic migration of this endosymbiont. Heredity. 2006;97: 27–32. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Broderick N a., Buchon N, Lemaitre B. Microbiota-induced changes in Drosophila melanogaster host gene expression and gut morphology. MBio. 2014;5: 1–13. 10.1128/mBio.01117-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wiśniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Methods. 2009;6: 359–362. 10.1038/nmeth.1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rappsilber J, Mann M, Ishihama Y. Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat Protoc. 2007;2: 1896–1906. 10.1038/nprot.2007.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26: 1367–1372. 10.1038/nbt.1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Romeo Y, Lemaitre B. Drosophila immunity: methods for monitoring the activity of Toll and Imd signaling pathways. Methods Mol Biol. United States; 2008;415: 379–394. 10.1007/978-1-59745-570-1_22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iatsenko I, Marra A, Boquete J-P, Peña J, Lemaitre B. Iron sequestration by transferrin 1 mediates nutritional immunity in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117: 7317 LP-7325. 10.1073/pnas.1914830117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29: e45–e45. 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIF)

(A) Quantification of Spiroplasma titer in two weeks old flies. Titer is expressed as the fold-change of Act5C-GAL4>UAS-RNAi over Act5C-GAL4> w1118. Bars represent the mean +/- standard deviation of a pool of at least 2 independent experiments. (B) Quantification of Spiroplasma titer in CG15293 mutant flies compared to control yw flies. Bars represent the mean +/- standard deviation of a pool of at least 3 independent experiments. ***; p<0.0005 upon Mann-Whitney test on ΔΔCt values.

(TIF)

(CSV)

(CSV)

(CSV)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD024340.