Abstract

Background

Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH) is a life-threatening hyperinflammatory event and a fatal complication of viral infections. Whether sHLH may also be observed in patients with a cytokine storm induced by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection is still uncertain. We aimed to determine the incidence of sHLH in severe COVID-19 patients and evaluate the underlying risk factors.

Method

Four hundred fifteen severe COVID-19 adult patients were retrospectively assessed for hemophagocytosis score (HScore). A subset of 7 patients were unable to be conclusively scored due to insufficient patient data.

Results

In 408 patients, 41 (10.04%) had an HScore ≥169 and were characterized as “suspected sHLH positive”. Compared with patients below a HScore threshold of 98, the suspected sHLH positive group had higher D-dimer, total bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, triglycerides, ferritin, interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, lactate dehydrogenase, creatine kinase isoenzyme, troponin, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, while leukocyte, hemoglobin, platelets, lymphocyte, fibrinogen, pre-albumin, albumin levels were significantly lower (all P < 0.05). Multivariable logistic regression revealed that high ferritin (>1922.58 ng/mL), low platelets (<101 × 109/L) and high triglycerides (>2.28 mmol/L) were independent risk factors for suspected sHLH in COVID-19 patients. Importantly, COVID-19 patients that were suspected sHLH positive had significantly more multi-organ failure. Additionally, a high HScore (>98) was an independent predictor for mortality in COVID-19.

Conclusions

HScore should be measured as a prognostic biomarker in COVID-19 patients. In particular, it is important that HScore is assessed in patients with high ferritin, triglycerides and low platelets to improve the detection of suspected sHLH.

Keywords: Secondary Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis, COVID-19, HScore, Ferritin, Triglycerides, Platelet, Cytokine storm

Highlights

Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH) has prognostic value in corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

HScore in severe COVID-19 cases can help detect sHLH

Risk factors for suspected sHLH in severe COVID-19 are high ferritin (>1922.58 ng/mL), low platelets (<101 × 109/L) and high triglycerides (>2.28 mmol/L).

Cytokine storm syndrome is the cause of suspected sHLH in severe COVID-19

Introduction

COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 continues to spread globally and represents a serious worldwide health problem [1]. RECOVERY trial results showed dexamethasone reduced 28-day mortality in severe COVID-19 by attenuating the exaggerated inflammatory response in the host [2]. However, in coronavirus infection, several studies observed delay in viral clearance with systemic corticosteroid therapy, potentially indicating increased viral replication as an adverse effect [1]. Therefore, it is urgent to accurately identify the patient subsets that may benefit from immunosuppressive treatment.

Accumulating evidence has indicated that a cytokine storm caused by an excessive immune response drives disease progression and organ failure in COVID-19 patients [3–5]. sHLH is a cytokine-driven fulminant hyperinflammatory syndrome associated with morbidity and mortality up to 88%. sHLH in adults often occurs after infections, especially viral infections by Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and influenza [6]. The main clinical features of sHLH include persistent fever, cytopenia, and hyperferritinemia [7]. Lung involvement is common and was shown to be an independent determinant of death in sHLH [8]. It is reasonable to speculate that the abnormal hyperinflammatory state in COVID-19 may induce sHLH, thus driving a poor prognosis.

A recent study suggested that HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome, could be used to identify suspected occurrence of sHLH in severe COVID-19 without mandatory bone marrow hemophagocytosis [3]. Once a diagnosis of sHLH is established, targeted interventions should be carried out rapidly, including immunosuppressants such as glucocorticoids and chemotherapy drugs [7]. To provide more accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment, it is necessary to conduct studies about sHLH in severe COVID-19.

In this study, we screened severe COVID-19 patients for sHLH with objectives to (1) determine the incidence of suspected sHLH in severe COVID-19, (2) describe clinical features of suspected sHLH associated with COVID-19, (3) evaluate risk factors for suspected sHLH and identify mortality-associated risk factors in COVID-19 patients, and (4) highlight potential relationships between emerging knowledge of COVID-19 disease progression and suspected sHLH.

Patients and methods

The present study is a single-center, retrospective study, which was approved by the ethics committee of Wuhan Infectious Diseases Hospital (KY-2020-03-01).

Data collection

A total of 1399 confirmed COVID-19 patients from January 2, 2020 to March 28, 2020 were screened. We retrieved demographic and epidemiological characteristics, laboratory testing results, clinical diagnosis and treatment data from electronic medical records and files.

Definition

Severe COVID-19 was defined according to WHO 2020 classification, as follows: fever or suspected respiratory infection, plus one of the following: respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min; severe respiratory distress; or SpO2 ≤ 93% on room air [9]. The Berlin Definition was used to diagnose acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [10]. Acute kidney injury (AKI) was diagnosed using the KDIGO criteria [11]. Prothrombin time test, the levels of fibrin/fibrinogen (Fib) degradation products, and platelet counts were used for the diagnosis of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [12]. Diagnosis of septic shock was based on the Third International Consensus Definition for Sepsis and Septic Shock [13]. Liver and heart injury were diagnosed according to laboratory testing results [14].

The HScore was developed by Fardet et al. and colleagues to estimate an individual’s risk of having sHLH. This scoring system can be freely available online (http://saintantoine.aphp.fr/score/) and contains nine items in routine practice, including known underlying immunodepression, maximal temperature (°C), hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lower hemoglobin level, lower leucocytes count, lower platelets count, higher ferritin level (ng/ml), higher triglyceride level (mmol/l), lower fibrinogen level (g/l), higher serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase/ recombinant aspartate aminotransferase (SGOT/ASAT) level (UI/L), hemophagocytosis features on bone marrow aspirate. We set HScore 169 and 98 as the cut off because HScore at 169 achieved the optimal discriminative power in previous study and HScore < 98 virtually rules out the diagnosis of sHLH [15]. Patients with HScores between 98 and 169 were not categorized as either suspected sHLH positive or negative [15].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as median (lower quartile, upper quartile) and compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Frequency was used to represent the unordered classification variables and Pearson chi-square tests were used for comparison. Ordered categorical variables were expressed as frequency and compared by Wilcoxon rank-sum or Kruskal-Wallis tests. A binary logistic regression model was used for multivariate analysis to select factors associated with suspected sHLH or death. The receiver-operator characteristic analysis and area under the curve were used to evaluate the discrimination of potential variables to diagnose suspected sHLH. The model was validated internally by bootstrap resampling, and the prognostic performance was measured by the concordance index (C-index) and calibration curve. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) or R software. Graphs were made in Stata 16.0 or MedCalc softwares. All probability calculations were two-tailed, and p values of 0.05 or less were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics and laboratory findings of severe COVID-19

Of the 1399 COVID-19 confirmed patients who met a treatment endpoint, either recovery or death, in Wuhan Infectious Diseases Hospital by March 28, 2020 were included in this study. Of 1399 patients, 424 met the criteria for severe COVID-19. However, 9 patients were missing, and thus 415 patients were included in this study for analysis. Among the 415 patients, 171 were female (41.20%) and 244 were male (58.80%), 255 were over than 60 years old (61.45%). Non-survivors were 220 (53.01%), including 138 male (62.73%).

Compared with survivors, non-survivors were older and had shorter length of hospital stay, higher SOFA scores and APACHE II scores at 24 h post-admission, significantly lower leukocytes, platelets, neutrophils, lymphocytes, Fib, pre-albumin, albumin, while D-Dimer, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum creatinine (sCr), ferritin, Interleukin − 6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatine kinase isoenzyme (CK-MB), troponin were all significantly higher (all P < 0.0001) (Table 1). There were no significant differences in underlying comorbidities between survivor and non-survivor patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all 415 patients with severe COVID-19 and stratified into survivors and non-survivors

| All(n = 415) | Survivors(n = 195) | Nonsurvivors(n = 220) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, Male/Female, n (%) | 244(58.80) /171(41.20) | 106(54.36)/ 89(45.64) | 138(62.73)/ 82(37.27) | 0.0839 |

| Age, years, Mean (SD) | 62.63(13.49) | 57.77(12.67) | 66.93(12.74) | < 0.0001 |

| age, years, n(%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| <40 | 23(5.54) | 15(7.69) | 8(3.64) | |

| 40–60 | 137(33.01) | 92(47.18) | 45(20.45) | |

| ≥ 60 | 255(61.45) | 88(45.13) | 167(75.91) | |

| ARDS, n(%) | 258(62.93)/ 152(37.07)a;5 | 75(38.46) /120(61.54) | 183(85.12)/ 32(14.88); 5 | < 0.0001 |

| DIC, n(%) | 20(5.00) /380(95.00); 15 | 1(0.52) /193(99.48); 1 | 19(9.22) /187(90.78); 14 | < 0.0001 |

| Liver injury, n(%) | 78(19.50) /322(80.50); 15 | 26(13.40) /168(86.60); 1 | 52(25.24)/ 154(74.76); 14 | 0.0028 |

| Heart injury, n(%) | 104(26.00) /296(74.00); 15 | 12(6.19) /182(93.81); 1 | 92(44.66)/ 114(55.34); 14 | < 0.0001 |

| Kidney injury, n(%) | 60(15.00) /340(85.00); 15 | 5(2.58) /189(97.42); 1 | 55(26.70)/ 151(73.30); 14 | < 0.0001 |

| Shock, n (%) | 87(21.75) /313(78.25); 15 | 2(1.03)/ 192(98.97); 1 | 85(41.26)/ 121(58.74); 14 | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking history, n(%) | 20(4.84) /393(95.16); 2 | 15(7.69)/ 180(92.31) | 5(2.29)/ 213(97.71); 2 | 0.0107 |

| Alcohol history, n(%) | 21(5.08)/ 392(94.92); 2 | 15(7.69)/ 180(92.31) | 6(2.75)/ 212(97.25);2 | 0.0225 |

| Comobidities | ||||

| Diabetes, n(%) | 79(19.13) /334(80.87); 2 | 30(15.38)/ 165(84.62) | 49(22.48) /169(77.52); 2 | 0.0673 |

| Hypertension, n(%) | 147(35.59)/ 266(64.41); 2 | 64(32.82)/ 131(67.18) | 83(38.07)/ 135(61.93); 2 | 0.2657 |

| Chronic heart failure, n(%) | 39(9.44) /374(90.56); 2 | 12(6.15)/ 183(93.85) | 27(12.39)/ 191(87.61); 2 | 0.0306 |

| COPD, n(%) | 13(3.15) /400(96.85); 2 | 3(1.54)/ 192(98.46) | 10(4.59)/ 208(95.41); 2 | 0.0765 |

| Stroke, n(%) | 26(6.30)/ 387(93.70); 2 | 10(5.13)/ 185(94.87) | 16(7.34)/ 202(92.66); 2 | 0.3557 |

| Malignant Tumor, n(%) | 19(4.60) /394(95.40); 2 | 10(5.13)/ 185(94.87) | 9(4.13)/ 209(95.87); 2 | 0.6283 |

| Chronic liver disease, n(%) | 14(3.39)/ 399(96.61); 2 | 5(2.56)/ 190(97.44) | 9(4.13)/ 209(95.87); 2 | 0.3805 |

| Chronic kidey disease, n(%) | 11(2.66) /402(97.34); 2 | 3(1.54)/ 192(98.46) | 8(3.67)/ 210(96.33); 2 | 0.1793 |

| Hepatitis B, n(%) | 15(3.62) /399(96.38); 1 | 7(3.59)/ 188(96.41) | 8(3.65)/ 211(96.35); 1 | 0.9726 |

| HIV, n (%) | 0(0.00) /414(100.00); 1 | 0(0.00)/ 195(100.00) | 0(0.00)/ 219(100.00); 1 | 1.0000 |

| Autoimmue disease, n(%) | 17(4.12) /396(95.88); 2 | 7(3.59)/ 188(96.41) | 10(4.59)/ 208(95.41); 2 | 0.6105 |

| Respiratory support, n(%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Intranasal oxygen inhalation | 146(37.15) | 122(63.21) | 24(12.00) | |

| Mask oxygen Inhalation | 18(4.58) | 10(5.18) | 8(4.00) | |

| High Flow | 67(17.05) | 24(12.44) | 43(21.50) | |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 75(19.08) | 9(4.66) | 66(33.00) | |

| Invasive ventilaiton | 53(13.49) | 3(1.55) | 50(25.00) | |

| ECMO | 4(1.02) | 0(0.00) | 4(2.00) | |

| CRRT, n(%) | 79(19.13) /334(80.87); 2 | 30(15.38)/ 165(84.62) | 49(22.48)/ 169(77.52); 2 | 0.0673 |

| Inotropic support, n(%) | 87(20.96)/328(79.03) | 2(1.03)/ 193(98.97) | 85(38.64)/ 135(61.36) | < 0.0001 |

| Corticosteroid treatment, n(%) | 226(54.45)/189(45.54) | 85(43.59)/ 110(56.41) | 141(64.09)/ 79(35.91) | < 0.0001 |

| Co-infection, n(%) | ||||

| Influenza A | 401(97.33)/ 6(1.46); 8 | 193(98.97)/ 2(1.03) | 208(95.85)/ 4(1.84); 8 | 0.0799 |

| Influenza B | 402(97.57)/ 5(1.21); 8 | 195(100.00)/ 0(0.00) | 207(95.39)/ 5(2.30); 8 | 0.0101 |

| Tuberculosis | 8(1.94)/ 405(98.06); 2 | 3(1.54)/ 192(98.46) | 5(2.29)/ 213(97.71); 2 | 0.8428 |

| Symptoms and signs, n(%) | ||||

| heart rate, (per minute) | 0.0002 | |||

| ≤ 100 | 37(15.42) | 28(26.17) | 9(6.77) | |

| >100 | 200(83.33) | 77(71.96) | 123(92.48) | |

| Total | 240(100.00) | 107(100.00) | 133(100.00) | |

| Nasal stuffiness | 8(1.94)/ 405(98.06); 2 | 4(2.05) /191(97.95) | 4(1.83) /214(98.17); 2 | 1.0000 |

| Nasal discharge | 12(2.91) /401(97.09); 2 | 5(2.56)/ 190(97.44) | 7(3.21)/ 211(96.79); 2 | 0.6960 |

| Sneezing | 4(0.97) /408(99.03); 3 | 3(1.54)/ 192(98.46) | 1(0.46)/ 216(99.54); 3 | 0.5414 |

| Sore throat | 8(1.94) /405(98.06); 2 | 4(2.05)/ 191(97.95) | 4(1.83)/ 214(98.17); 2 | 1.0000 |

| Cough | 330(79.90) /83(20.10); 2 | 157(80.51)/ 38(19.49) | 173(79.36)/ 45(20.64); 2 | 0.7700 |

| Sputum production | 157(38.01)/ 256(61.99); 2 | 67(34.36)/ 128(65.64) | 90(41.28)/ 128(58.72); 2 | 0.1478 |

| Chest tightness | 264(63.92)/ 149(36.08); 2 | 113(57.95)/ 82(42.05) | 151(69.27)/ 67(30.73); 2 | 0.0168 |

| Chest pain | 12(2.91) /401(97.09); 2 | 6(3.08)/ 189(96.92) | 6(2.75)/ 212(97.25); 2 | 0.8445 |

| Hemoptysis | 7(1.69) /406(98.31); 2 | 4(2.05)/ 191(97.95) | 3(1.38)/ 215(98.62); 2 | 0.8817 |

| Headache | 13(3.15)/ 400(96.85); 2 | 10(5.13)/ 185(94.87) | 3(1.38)/ 215(98.62); 2 | 0.0292 |

| Myalgia | 49(11.86) /364(88.14); 2 | 29(14.87)/ 166(85.13) | 20(9.17)/ 198(90.83); 2 | 0.0739 |

| Fatigue | 165(40.05) /247(59.95); 3 | 78(40.21)/ 116(59.79) | 87(39.91)/ 131(60.09); 2 | 0.9509 |

| Digestive symptoms | 58(14.04)/ 355(85.96); 2 | 28(14.36)/ 167(85.64) | 30(13.76)/ 188(86.24); 2 | 0.8615 |

| Discomfort of eye | 1(0.24)/ 412(99.76); 2 | 1(0.51)/ 194(99.49) | 0(0.00)/ 218(100.00); 2 | 0.4722 |

| Cyanosis | 48(11.59) /366(88.41); 1 | 10(5.13)/ 185(94.87) | 38(17.35)/ 181(82.65); 1 | 0.0001 |

| Rhonchial | 26(6.30) /386(93.46); 3 | 13(6.67)/ 181(92.82) | 13(5.96)/ 205(94.04); 2 | 1.0000 |

| Moist rales | 76(18.40) /337(81.60); 2 | 33(16.92)/ 162(83.08) | 43(19.72)/ 175(80.28); 2 | 0.4632 |

| SPO2(≤93%/>93%) | 279(67.23)/ 136(32.77) | 96(49.23)/ 99(50.77) | 183(83.18)/ 37(16.82) | < 0.0001 |

| Length of hospitalization, d | 12.00(7.00,18.00); | 15.00 (11.00,20.00) | 10.00(4.00,15.00) | < 0.0001 |

| Length of ICU, d | 2.00(0.00,9.00); | 0.00 (0.00,6.50); | 3.00 (1.00,9.00); | < 0.0001 |

| Temperature, °C | 38.50(38.00,39.00) | 38.50 (38.00,39.00) | 38.50 (38.00,39.00) | 0.5281 |

| arterial pressure, mmHg | 87.00(79.83,92.83); 21 | 86.00 (78.00,91.33);2 | 88.00 (82.00,93.67); 19 | 0.0005 |

| heart rate, per mimute | 89.00(81.00,100.00); 2 | 90.00 (82.00,100.00) | 88.50 (80.00,102.00); 2 | 0.9356 |

| respiratory rate | 22.00(20.00,26.00); 1 | 22.00 (20.00,26.00) | 22.00 (20.00,28.00) | 0.7331 |

| <24, (per minute) | 251(60.48) | 122(62.56) | 129(58.64) | 0.3642 |

| 24–30, (per minute) | 87(20.96) | 40(20.51) | 47(21.36) | |

| ≥ 30, (per minute) | 77(18.55) | 33(16.92) | 44(20.00) | |

| Total | 415(100.00) | 195(100.00) | 220(100.00) | |

| SOFA | 3.00(1.00,4.00); 4 | 2.00(1.00, 3.00) | 3.00(2.00,5.00); 4 | < 0.0001 |

| APACHEII | 7.00(5.00,10.00); 4 | 6.00 (4.00,7.00) | 9.00 (7.00,13.00); 4 | < 0.0001 |

| Laboratory Tests | ||||

| Lowest leukocyte, ×109/L | 5.44(3.83, 8.50)b; 10 | 4.45 (3.43,5.91) | 7.57 (4.63,11.60); 10 | < 0.0001 |

| Lowest haemoglobin, g/L | 109.00(88.00,123.00); 10 | 110.00 (91.00,124.00) | 108.00 (86.00,122.00); 10 | 0.5267 |

| Lowest patelets, ×109/L | 125.50(53.00,188.00);9 | 152.00 (86.00,217.00) | 91.00 (42.00,165.00); 9 | < 0.0001 |

| Lowest neutrophils, ×109/L | 5.38(3.00,11.36); 14 | 3.55 (2.55,8.59) | 6.99 (4.30,11.63); 14 | < 0.0001 |

| Lowest lymphocyte, ×109/L | 0.55(0.35,1.06); 11 | 0.86 (0.49,1.44) | 0.44 (0.28,0.64); 11 | < 0.0001 |

| Lowest fibrinogen, g/L | 4.10(2.70,5.90); 22 | 4.50 (3.40,6.50);6 | 3.60 (2.20,5.30); 16 | < 0.0001 |

| Lowest prealbumin, g/L | 83.00(45.00,117.00); 10 | 104.00 (67.00,145.00); 1 | 64.00 (33.00,98.00); 9 | < 0.0001 |

| Lowest albumin, g/L | 28.00(25.10,31.40); 8 | 30.10 (27.60,34.40) | 26.00 (23.45,28.70); 8 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak D-Dimer, mg/L | 10.06(1.15,42.82) | 1.58 (0.63,14.04) | 27.31 (7.60,58.76) | < 0.0001 |

| Peak total bilirubin, μg/L | 18.95(13.00,32.30); 13 | 15.40 (11.70,30.00); 2 | 22.50 (15.39,32.76); 11 | 0.0019 |

| Peak alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 49.00(31.00,77.00); 12 | 48.00 (30.00,68.00) | 50.50 (31.50,87.00); 12 | 0.1652 |

| Peak aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 43.00(29.00,72.00); 11 | 34.00 (24.00,50.00) | 57.00 (36.00,108.00); 11 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak blood urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 9.20(5.97,18.00); 14 | 6.66 (5.03,9.79); 1 | 14.90 (8.10,24.30); 13 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak serum creatinine, μg/L | 82.00(59.40,139.80); 13 | 70.70 (53.70,89.30) | 120.70 (69.30,276.80); 13 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak triglycerides, mmol/L | 2.15(1.42,3.43); 14 | 2.16 (1.42,4.53);1 | 2.10 (1.41,3.27); 13 | 0.5062 |

| Peak ferritin, μg/L | 927.22(492.02,2000.00); 18 | 600.08 (356.00,987.50);6 | 1675.09 (837.84,2000.00);12 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak Interleukin −6, pg/mL | 11.18(7.92,19.57); 26 | 9.32 (6.90,13.50); 9 | 13.89 (9.99,27.90); 17 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm/h | 60.00(43.00,79.00); 22 | 61.00 (45.30,88.00); 4 | 59.35 (40.00,73.00); 18 | 0.0527 |

| Peak C-reactive protein, mg/L | 122.60(30.50,160.00); 12 | 49.40 (8.70,121.90); 3 | 160.00 (111.00,160.40); 9 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak procalcitonin, ng/mL | 0.20(0.06,2.87); 17 | 0.07 (0.05,0.23); 4 | 1.08 (0.16,6.40); 13 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 429.00(274.00,699.00); 10 | 300.50 (221.00,403.00); 1 | 675.00 (464.00,1095.00); 9 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak creatine kinase isoenzyme, U/L | 27.00(17.00,66.00); 16 | 19.50 (14.00,51.00); 1 | 34.00 (20.00,84.00); 15 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak Troponin, pg/mL | 10.85(3.50,99.00); 13 | 4.40 (1.70,9.10); 1 | 70.50 (11.20,823.05); 12 | < 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: ARDS Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, DIC Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, ECMO Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, CRRT Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy, ICU Intensive Care Unit, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, APACHE Acute Physiology, Age, Chronic Health Evaluation

Data are expressee as: aNo. (%) yes/no; no. missing (if applicable); bMedian (range); no. missing (if applicable)

P value compare between survivor group vs non-survivor group, P < 0.05 means had significantly different

Clinical characteristics and laboratory findings of COVID-19 associated with suspected sHLH according to HScore

Of the 415 patients the available data was only sufficient to generate HScores for 408. Of these 408 patients, 41 (10.05%) had a HScore≥169 and were identified as suspected sHLH. Conversely, 279 (68.38%) had a HScore≤98 were considered negative for suspected sHLH. The remaining 88 patients had HScores 98–169 and were not categorized.

Mortality in the suspected sHLH positive group was significantly higher than that in the suspected sHLH negative group (100.00% vs 34.77%, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics and Laboratory Findings of COVID-19 according to HScore (≤98 as sHLH negative, ≥169 as sHLH positive, 98–169 as uncertain)

| ≤98 (n = 279) | ≥169(n = 41) | 98–169(n = 88) | P valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| outcome | < 0.0001 | |||

| Survivor, n(%) | 182(65.23) | 0(0.00) | 13(14.77) | |

| Non-survivor, n(%) | 97(34.77) | 41(100.00) | 75(85.23) | |

| Total | 279(100.00) | 41(100.00) | 88(100.00) | |

| Gender, Male/Female, n(%) | 153(54.84)/ 126(45.16) | 27(65.85)/14(34.15) | 60(68.18)/28(31.82) | 0.0537 |

| Age, years, Mean (SD) | 63.00(52.00,72.00) | 63.00(52.00,71.00) | 65.00(57.00,72.00) | 0.2419 |

| age, years, n(%) | 0.1869 | |||

| <40 | 17(6.09) | 3(7.32) | 3(3.41) | |

| 40–60 | 101(36.20) | 11(26.83) | 25(28.41) | |

| ≥ 60 | 161(57.71) | 27(65.85) | 60(68.18) | |

| ARDS, n(%) | 150(53.76)/129(46.24)a | 34(85.00)/6(15.00); 1 | 68(80.95)/16(19.05); 4 | < 0.0001 |

| DIC, n(%) | 6(2.17)/ 271(97.83); 2 | 4(10.53)/34(89.47);3 | 10(12.66)/69(87.34); 9 | 0.0004 |

| Liver, n(%) | 36(13.00)/241(87.00); 2 | 12(31.58)/26(68.42); 3 | 30(37.97)/49(62.03); 9 | < 0.0001 |

| Heart, n(%) | 50(18.05)/227(81.95); 2 | 17(44.74)/21(55.26); 3 | 35(44.30)/44(55.70); 9 | < 0.0001 |

| Kidney, n(%) | 17(6.14)/260(93.86); 2 | 16(42.11)/22(57.89); 3 | 26(32.91)/53(67.09); 9 | < 0.0001 |

| Shock, n(%) | 31(11.19)/246(88.81); 2 | 20(52.63)/18(47.37); 3 | 34(43.04)/45(56.96); 9 | < 0.0001 |

| Smoking history, n(%) | 14(5.04)/264(94.96); 1 | 2(4.88)/39(95.12) | 4(4.60)/83(95.40); 1 | 0.9111 |

| Alcohol history, n(%) | 16(5.76)/262(94.24); 1 | 1(2.44)/40(97.56) | 4(4.60)/83(95.40); 1 | 0.3577 |

| Comobidities | ||||

| Diabetes,n(%), n(%) | 50(17.99)/228(82.01); 1 | 9(21.95)/32(78.05) | 20(22.73)/68(77.27) | 0.5630 |

| Hypertension, n(%) | 97(34.89)/181(65.11); 1 | 11(26.83)/30(73.17) | 38(43.18)/50(56.82) | 0.1639 |

| Chronic heart failure, n(%) | 29(10.43)/249(89.57); 1 | 2(4.88)/39(95.12) | 7(7.95)/81(92.05) | 0.2138 |

| COPD, n(%) | 5(1.80)/273(98.20); 1 | 2(4.88)/39(95.12) | 6(6.82)/82(93.18) | 0.0537 |

| Stroke, n(%) | 18(6.47)/260(93.53); 1 | 0(0.00)/41(100.00) | 8(9.09)/80(90.91) | 0.3853 |

| Tumor, n(%) | 11(3.96)/267(96.04); 1 | 2(4.88)/39(95.12) | 5(5.68)/83(94.32) | 0.5927 |

| Chronic liver disease, n(%) | 6(2.16)/272(97.84); 1 | 2(4.88)/39(95.12) | 6(6.82)/82(93.18) | 0.0907 |

| Chronic kidey disease, n(%) | 7(2.52)/271(97.48); 1 | 2(4.88)/39(95.12) | 2(2.27)/86(97.73) | 0.5200 |

| Hepatitis B,n(%) | 11(3.94)/268(96.06) | 3(7.32)/38(92.68) | 1(1.15)/86(98.85); 1 | 0.7610 |

| HIV, n(%) | 0(0.00)/279(100.00) | 0(0.00)/41(100.00) | 0(0.00)/87(100.00); 1 | 1.0000 |

| Autoimmue disease, n(%) | 7(2.52)/271(97.48); 1 | 3(7.32)/38(92.68) | 6(6.82)/82(93.18) | 0.0422 |

| Respiratory support, n(%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Intranasal oxygen inhalation | 129(47.43) | 3(8.11) | 13(16.46) | |

| Mask oxygen Inhalation | 16(5.88) | 1(2.70) | 1(1.27) | |

| High Flow | 48(17.65) | 3(8.11) | 14(17.72) | |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 35(12.87) | 12(32.43) | 26(32.91) | |

| Invasive ventilaiton | 17(6.25) | 14(37.84) | 22(27.85) | |

| ECMO | 1(0.37) | 3(8.11) | 0(0.00) | |

| CRRT, n(%) | 50(17.99)/228(82.01); 1 | 9(21.95)/32(78.05) | 20(22.73)/68(77.27) | 0.5630 |

| Inotropic support, n(%) | 33(11.83)/ 246(88.17) | 21(51.22)/ 20(48.78) | 30(34.09)/ 58(65.91) | < 0.0001 |

| Corticosteroid treatment, n(%) | 133(47.67)/ 146(52.33) | 35(85.37)/ 6(14.63) | 55(62.50)/ 33(37.50) | < 0.0001 |

| Co-infection, n(%) | ||||

| Influenza A | 3(1.08)/ 273(98.56); 3 | 1(2.44)/ 38(92.68); 2 | 2(2.27) /84(95.45); 2 | 0.0924 |

| Influenza B | 1(0.36)/275(99.28); 3 | 1(2.44)/ 38(92.68); 2 | 3(3.41) /83(94.32); 2 | 0.0127 |

| Tuberculosis | 4(1.44) /274(98.56);1 | 1(2.44)/ 40(97.56) | 3(3.41)/ 85(96.59) | 1.0000 |

| Symptoms and signs, n(%) | ||||

| heart rate, (per minute) | 0.6759 | |||

| ≤ 100 | 32(21.77) | 2(3.57) | 4(6.67) | |

| >100 | 113(76.87) | 26(92.86) | 56(93.33) | |

| Total | 147(100.00) | 28(100.00) | 60(100.00) | |

| Nasal stuffiness | 5(1.80) /273(98.20); 1 | 2(4.88) /39(95.12) | 1(1.14) 87(98.86) | 1.0000 |

| Nasal discharge | 6(2.16)/272(97.84); 1 | 5(12.20)/ 36(87.80) | 1(1.14)/87(98.86) | 0.0086 |

| Sneezing | 3(1.08)/ 275(98.92); 1 | 0(0.00)/40(100.00); 1 | 1(1.14)/87(98.86) | 1.0000 |

| Sore throat | 4(1.44)/274(98.56); 1 | 1(2.44)/40(97.56) | 3(3.41)/ 85(96.59) | 1.0000 |

| Cough | 226(81.29)/ 52(18.71); 1 | 30(73.17)/11(26.83) | 69(78.41)/ 19(21.59) | 0.4468 |

| Sputum production | 104(37.41)/174(62.59); 1 | 16(39.02)/25(60.98) | 33(37.50)/55(62.50) | 0.9802 |

| Chest tightness | 172(61.87)/106(38.13); 1 | 30(73.17) /11(26.83) | 58(65.91) /30(34.09) | 0.3367 |

| Chest pain | 7(2.52) /271(97.48) | 1(2.44) /40(97.56) | 4(4.55)/ 84(95.45) | 0.6647 |

| Hemoptysis | 5(1.80) 273(98.20); 1 | 2(4.88) /39(95.12) | 0(0.00) /88(100.00) | 1.0000 |

| Headache | 9(3.24)/ 269(96.76); 1 | 2(4.88) /39(95.12) | 2(2.27)/ 86(97.73) | 0.8098 |

| Myalgia | 34(12.23) /244(87.77); 1 | 3(7.32) /38(92.68) | 12(13.64) /76(86.36) | 0.5736 |

| Acratia | 102(36.82)/175(63.18);2 | 26(63.41) /15(36.59) | 35(39.77)/ 53(60.23) | 0.0052 |

| Digestive symptoms | 36(12.95) /242(87.05) | 9(21.95)/ 32(78.05) | 13(14.77)/ 75(85.23) | 0.3021 |

| Discomfort of eye | 1(0.36)/ 277(99.64); 1 | 0(0.00)/ 41(100.00) | 0(0.00)/ 88(100.00) | 1.0000 |

| Cyanosis | 27(9.71) /251(90.29); 1 | 10(24.39) /31(75.61) | 7(7.95)/ 81(92.05) | 0.0393 |

| Rhonchial | 18(6.47) 259(93.17); 1 | 4(9.76) /37(90.24) | 4(4.55)/ 84(95.45) | 1.0000 |

| Moist rales | 51(18.35)/ 227(81.65) | 12(29.27) /29(70.73) | 12(13.64) 76(86.36) | 0.1028 |

| SPO2(≤93%/>93%) | 173(62.01)/ 106(37.99) | 32(78.05)/ 9(21.95) | 67(76.14)/ 21(23.86) | 0.0131 |

| Length of hospitalization, d | 12.00(8.00,18.00)b | 17.00(11.00,22.50) | 12.00(7.00,16.00) | 0.0029 |

| Length of ICU, d | 0.00(0.00,6.00) | 9.50(3.50,12.00) | 3.00(0.50,12.00) | < 0.0001 |

| Temperature, °C | 38.50(38.00,39.00) | 38.50(38.00,38.90) | 38.90(38.00,39.00) | 0.4406 |

| Arterial pressure, mmHg | 87.00(78.33,93.00) | 86.58(81.50,91.33) | 86.75(81.33,93.50) | 0.1593 |

| Heart rate, per mimute | 89.00(82.00,99.00); 1 | 90.0081.00,100.00 | 88.00(80.00,102.00) | 0.5895 |

| Respiratory rate | 0.5070 | |||

| <24, (per minute) | 164(58.78) | 26(63.41) | 58(65.91) | |

| 24–30, (per minute) | 65(23.30) | 5(12.20) | 15(17.05) | |

| ≥ 30, (per minute) | 50(17.92) | 10(24.39) | 15(17.05) | |

| Total | 279(100.00) | 41(100.00) | 88(100.00) | |

| SOFA | 2.00(1.00,3.00) | 3.00(1.00,4.00) | 3.00(2.00,5.00) | < 0.0001 |

| APACHEII | 7.00(5.00,9.00) | 8.00(6.00,11.00) | 8.00(6.00,13.00) | 0.0010 |

| Laboratory Tests | ||||

| Lowest leukocyte, ×109/L | 5.08(3.74,7.83)b; 4 | 6.97(4.38,9.31) | 6.77(3.81,10.53); 1 | 0.0118 |

| Lowest haemoglobin, g/L | 112.00(94.00,124.00); 4 | 95.00(77.00,106.00) | 106.00(78.00,122.00); 1 | 0.0020 |

| Lowest patelets, ×109/L | 151.00(81.00,197.00); 3 | 61.00(27.00,101.00) | 83.00(26.00,144.00); 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Lowest neutrophils, ×109/L | 4.73(2.76,11.46); 8 | 5.10(3.32,7.39) | 7.02(3.97,12.72); 1 | 0.0804 |

| Lowest lymphocyte, ×109/L | 0.69(0.44,1.22); 5 | 0.33(0.18,0.53) | 0.43(0.28,0.66); 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Lowest fibrinogen, g/L | 4.50(3.24,6.35); 15 | 2.40(1.60,3.46) | 3.80(2.10,5.40); 2 | < 0.0001 |

| Lowest prealbumin, g/L | 93.00(59.00,127.00); 4 | 51.00(28.00,85.00) | 55.00(29.00,89.00); 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Lowest albumin, g/L | 28.90(26.20,32.30); 2 | 24.40(22.30,27.60) | 26.60(23.40,28.90); 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak D-Dimer, mg/L | 4.58(0.80,32.09); 5 | 47.82(20.06,80.00) | 17.83(3.46,63.70); 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak total bilirubin, μg/L | 16.60(12.20,30.00); 6 | 23.98(17.38,37.80) | 25.20(16.60,32.30); 1 | 0.0007 |

| Peak alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 47.00(28.00,67.00); 6 | 57.00(36.00,122.00) | 62.00(38.00,109.00); 1 | 0.0001 |

| Peak aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 38.00(26.00,55.00); 5 | 85.00(52.00,215.00) | 65.00(40.00,121.00); 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak blood urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 7.50(5.30,11.00); 8 | 21.66(13.50,35.30) | 14.90(8.50,24.00); 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak serum creatinine, μg/L | 72.95(55.60,99.00); 7 | 246.10(146.00,413.70) | 105.20(67.40,263.10); 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.95(1.31,3.27); 8 | 3.27(2.33,4.27) | 2.20(1.58,3.43); 1 | 0.0001 |

| Peak ferritin, μg/L | 710.11(433.23,1276.37); 11 | 2000.00(2000.00,2000.00) | 2000.00(962.51,2000.00); 2 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak Interleukin −6, pg/mL | 10.20(7.26,14.98); 16 | 23.41(11.73,60.57); 1 | 14.60(8.56,26.90); 4 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm/h | 60.00(43.00,80.00); 10 | 65.50(49.20,79.00); 3 | 58.30(39.00,74.00); 4 | 0.5133 |

| Peak C-reactive protein, mg/L | 76.68(15.60,160.00); 5 | 160.00(160.00,206.40) | 160.00(121.20,198.80); 2 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak procalcitonin, ng/mL | 0.11(0.05,0.50); 10 | 4.21(2.63,15.22) | 0.98(0.19,4.90); 2 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 349.00(241.00,534.00); 4 | 1096.00(708.00,1676.00) | 662.00(432.00,944.00); 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak creatine kinase isoenzyme, U/L | 21.50(15.00,52.50); 9 | 47.00(32.00,85.00) | 38.00(21.00,77.00); 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Peak Troponin, pg/mL | 6.15(2.40,24.60); 7 | 303.10(33.80,2202.10) | 51.50(6.44,591.40); 1 | < 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: ARDS Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, DIC Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, ECMO Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, CRRT Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy, ICU Intensive Care Unit, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, APACHE Acute Physiology, Age, Chronic Health Evaluation

Data are expressee as: aNo. (%) yes/no; no. missing (if applicable); bMedian (range); no. missing (if applicable)

c P value compare between Hscore ≥169 group vs Hscore ≤98 group, P < 0.05 means had significantly different

There were no statistically significant differences in age and gender between suspected sHLH negative and positive groups. Clinical symptoms and signs were similar in suspected sHLH positive group and negative group, except cyanosis was more frequent in suspected sHLH positive patients (P = 0.03). For comobidities, suspected sHLH positive patients had significantly higher autoimmue disease (P = 0.042).

Compared to the suspected sHLH negative group, the suspected sHLH positive group had significantly higher prevalence of complications including ARDS, DIC, liver injury, heart injury, AKI and, shock as well as high SOFA scores (all P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Several laboratory findings were also statistically different between patients with suspected sHLH compared to those without, such as lower haemoglobin (Hb), platelets, lymphocytes, fibrinogen, pre-albumin, albumin, and higher D-Dimer, total bilirubin (Tbil), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), AST, triglycerides (TG), BUN, sCr, IL-6, PCT, LDH, ferritin, CK-MB, troponin,

With regard to treatments, of 41 suspected sHLH suspected patients, 8.11% (n = 3) received high-flow nasal cannula, 32.43% (n = 12) received non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation (NPPV), 37.84% (n = 14) were intubated, 8.11% (n = 3) received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, 21.95% (n = 9) received continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), 51.22% (n = 21) received inotropic support and 85.37% (n = 35) received corticosteroid treatment. Except CRRT (P = 0.56), all above-mentioned treatments in suspected sHLH positive group were significantly more common compared to suspected sHLH negative group (all P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Risk factors for mortality of severe COVID-19

High SOFA score, low leukocyte, low lymphocyte, low prealbumin, high AST, high CRP, high LDH and old age, were all significantly associated with death in severe COVID-19 patients by logistic regression analysis (all P < 0.05) (Table 3). In addition a higher HScore was also significantly associated with death in severe COVID-19 patients. This association was significant in comparison of patients with HScore ≤98 versus patients with HScore ≥169 (Odds Ratio = 22.77, 95% Confidence Interval, 2.23–232.80, P = 0.008), and was also significant with comparison of patients with HScore ≤98 versus patients with HScore 98–169 (Odds Ratio = 4.02, 95% Confidence Interval, 1.55–10.44, P = 0.004).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analyses of potential risk factors of Hemophagocytic lymphohistiosytosis (HLH)

| Regression Coefficient | OR (Odds Ratio) | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOFA | 0.221 | 1.247 | 1.010–1.539 | 0.040 |

| Lowest haemoglobin, g/L | 0.003 | 1.003 | 0.983–1.023 | 0.769 |

| Lowest platelet,×109/L | 0.008 | 1.008 | 1.000–1.015 | 0.038 |

| Lowest neutrophils, ×109/L | 0.025 | 1.026 | 0.987–1.066 | 0.195 |

| Lowest fibrinogen, g/L | 0.042 | 1.043 | 0.999–1.089 | 0.052 |

| Lowest prealbumin, g/L | 0.006 | 1.006 | 0.994–1.017 | 0.332 |

| Peak D-Dimer, mg/L | −0.004 | 0.996 | 0.993–1.00 | 0.061 |

| Peak aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | −0.000 | 1.000 | 0.999–1.001 | 0.910 |

| Peak serum creatinine, μg/L | −0.002 | 0.998 | 0.996–1.000 | 0.126 |

| Peak triglycerides, mmol/L | −0.300 | 0.741 | 0.611–0.900 | 0.003 |

| Peak ferritin, ng/mL | −0.002 | 0.998 | 0.997–0.999 | < 0.001 |

| Peak Interleukin −6, pg/mL | −0.000 | 1.000 | 0.999–1.000 | 0.175 |

| Peak C-reactive protein, mg/L | −0.002 | 0.998 | 0.990–1.005 | 0.510 |

| Peak lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | −0.000 | 1.000 | 0.999–1.000 | 0.639 |

Abbreviations: SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

P value compare between Hscore ≥169 group vs Hscore <169 group, P < 0.05 means had significantly different

Risk factors related to COVID-19 associated suspected sHLH

Multivariable logistic regression analyses found that independent risk factors for discriminating suspected sHLH in COVID-19 included high triglycerides (Odds Ratio, 0.74; 9% Confidence Interval, 0.61–0.90), high ferritin (Odds Ratio, 0.99; 95% Confidence Interval, 0.997–0.999), low platelets (Odds Ratio, 1.0079; 95% Confidence Interval, 1.00–1.01) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analyses of potential risk factors of mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

| Regression Coefficient | OR (Odds Ratio) | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOFA | 0.317 | 1.373 | 1.006–1.712 | 0.005 |

| Lowest leukocyte, ×109/L | 0.277 | 1.319 | 1.174–1.491 | < 0.001 |

| Lowest neutrophils, × 109/L | −0.011 | 0.989 | 0.976–1.001 | 0.080 |

| Lowest lymphocyte, ×109/L | 0.316 | 1.372 | 1.089–1.729 | 0.007 |

| Lowest prealbumin, g/L | −0.012 | 0.987 | 0.979–0.994 | 0.001 |

| Lowest albumin, g/L | 0.012 | 1.013 | 0.988–1.038 | 0.300 |

| Peak D-Dimer, mg/L | −0.001 | 0.998 | 0.991–1.005 | 0.632 |

| Peak aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | −0.004 | 0.995 | 0.992–0.997 | 0.000 |

| Peak blood urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 0.0004 | 1.000 | 0.989–1.011 | 0.931 |

| Peak serum creatinine, μg/L | 0.001 | 1.001 | 0.999–1.003 | 0.131 |

| Peak Interleukin −6, pg/mL | −0.000 | 0.999 | 0.998–1.000 | 0.880 |

| Peak C-reactive protein, mg/L | 0.006 | 1.006 | 1.000–1.012 | 0.036 |

| Peak lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 0.003 | 1.003 | 1.001–1.005 | < 0.001 |

| Peak creatine kinase isoenzyme, U/L | 0.003 | 1.003 | 0.999–1.008 | 0.080 |

| Peak Troponin, pg/mL | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.999–1.000 | 0.293 |

| Age, y | 0.057 | 1.059 | 1.030–1.088 | < 0.001 |

| Hscore 98–169 vs ≤98 | 1.393 | 4.028 | 1.553–10.444 | 0.004 |

| Hscore ≥169 vs ≤98 | 3.125 | 22.770 | 2.227–232.800 | 0.008 |

Abbreviations: SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

P value compare between survivor group vs nonsurvivor group, P < 0.05 means had significantly different

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis indicated that high ferritin may alone diagnose suspected sHLH in COVID-19, which had an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.816 (P < 0.01, sensitivity 85.4%, specificity 76.6%, cut-off value > 1922.58 ng/mL). A combination of high ferritin (cut-off value > 1922.58 ng/mL), high triglycerides (cut-off value > 2.28 mmol/L), and low platelets (cut-off value < 101 × 109/L) had an AUC of 0.863 (P < 0.001, sensitivity 85.4%, specificity 75.4%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for peak TG (a), ferritin (b), PLT (c) respectively. Receiver operating characteristic curve for the multivariable logistic regression model, including TG, ferritin, PLT (d). Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; TG, triglyceride; PLT, platelet

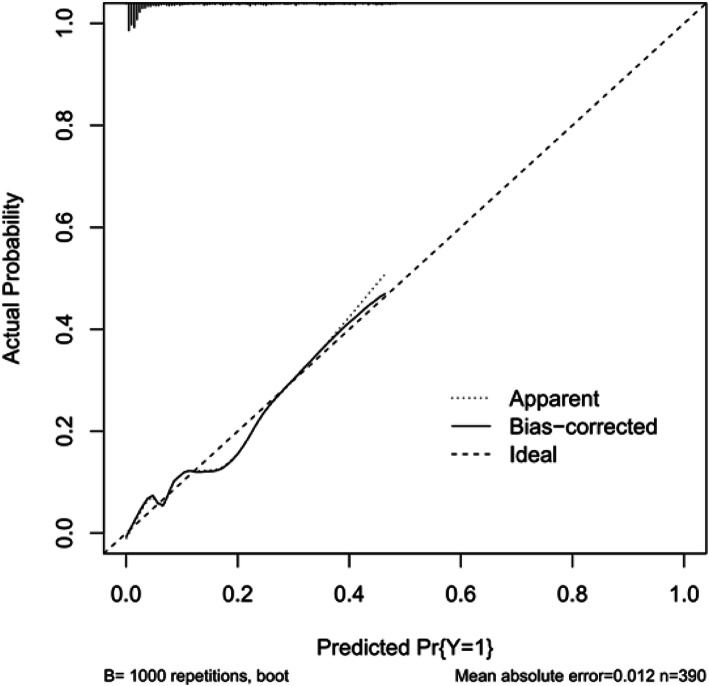

Internal validation was conducted using a bootstrapping strategy (1000 repetitions), the results achieved a C-index of 0.863 (95%CI 0.838–0.889). The calibration plot was shown Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Internal validation to validate a prediction model

Discussion

Herein, we present data that demonstrates the prognostic value of HScores, and three independent risk factors for high HScores in a specific cohort of severe COVID-19 patients. In this cohort, mortality was 53.01% in patients with severe COVID-19 and 100% in patients with suspected sHLH. Furthermore, we observed a significantly higher incidence of multi-organ dysfunction in patients with suspected sHLH. The frequency rate of suspected sHLH in severe COVID-19 patients was 10.05% (41 of 408). We assessed the clinical factors associated with suspected sHLH including hemoglobin, platelets, lymphocytes, fibrinogen, pre-albumin, albumin, D-dimer, total bilirubin, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, triglycerides, ferritin, interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, pro-calcitonin, lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine kinase-MB and troponin. The independent risk factors of suspected sHLH in this study were low platelet count(< 101 × 109/ml), high triglycerides(>2.28 mmol/L) and high ferritin (>1922.58 ng/mL).

There are two major kinds of HLH: primary and secondary. Primary HLH is related to gene defects – wherein typically CD8 and Natural Killer (NK) mediated cytotoxic genes are defective. Secondary HLH is acquired through infection, malignant conditions, and autoimmune diseases. It is a rare life-threatening complication characterized by uncontrolled activation of CD8 + T cells and NK cells, cytokine storm, and severe organ dysfunction [6, 7]. However, suspected sHLH lacks specific clinical characters [7]. Our study found that severe COVID-19 patients with suspected sHLH had similar clinical manifestations including body temperature, heart rhythm, respiration, and clinical symptoms as those without suspected sHLH. The overlap of clinical features impedes the diagnosis of suspected sHLH in severe infectious diseases especially in the case of cytopenias, prolonged fevers, and non-responsiveness to treatment [6, 7]. According to recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults, reevaluation of the clinical condition should be frequent (at least every 12 h) to determine if additional HLH-directed therapy is needed [16]. Therefore, the assessment of HScore in severe COVID-19 patients could improve the detection rates of suspected sHLH and promote early targeted-treatment. The HLH-2004 protocol was also widely used for the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. We did not apply HLH-2004 as diagnosis tool because most of the patients in our study did not have data on four diagnostic items of HLH-2004 protocol, including haemophagocytosis in bone marrow or spleen or lymph nodes, low or absent natural killer cell activity, soluble CD25 (soluble interleukin-2 receptor).

Progression of COVID-19 into organ failure results from a catastrophic overreaction of the immune system to the virus, known as a “cytokine storm”. Cytokine storms are characterized by high levels of IL-6, C-reactive protein and ferritin and causes immune cell-mediated tissue damage and catastrophic organ failure [6, 7]. As demonstrated in this study, the levels of IL-6, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were significantly higher in the suspected sHLH positive group than in the suspected sHLH negative group. It has been previously suggested that the presence of high ferritin syndrome in COVID-19 was a high-risk factor for suspected sHLH [3, 5]. Consistent with this, we observed that increased peak ferritin was associated with suspected sHLH and with increased fatality in severe COVID-19 (P < 0.001). It is important to consider that a higher ferritin level than 1922 ng/ml may be used as a screening indicator for suspected sHLH related to COVID-19.

Hypertriglyceridemia (fasting, equal to, or greater than 1.5 mmol/L) is one of the current diagnostic criteria for suspected sHLH [15]. Our results showed that hypertriglyceridemia (> 2.28 mmol/L) might be an independent risk factor to determine severe COVID-19 associated suspected sHLH. It also is easily available and standardized as laboratory diagnostic testing in clinical practice. The hyperinflammatory response contributes to hypertriglyceridemia via prolonged and intense T-lymphocyte and macrophage signaling. The proinflammatory signaling induces elevated IL-6 which mobilizes free fatty acids from adipocytes, decreased lipoprotein lipase activity and increased tumor necrosis factor alpha expression [17]. Furthermore, metabolic syndrome, wherein hypertriglyceridemia is a hallmark, also has characteristic increased serum ferritin levels, suggesting similar pathogenic mechanisms [18].

Thrombocytopenia is reported to be common in COVID-19 patients and is considered a risk factor for increased disease severity and mortality [19]. In our cohort study, severe COVID-19 patients had a low median platelet count (125.50 × 109/L). The mechanism underlying the low count of platelet in COVID-19 is multi-factorial and complex. First, SARS-CoV-2 damages endothelial cells triggering platelet activation and thrombosis in multi-organ, causing vast platelet consumption [19, 20]. Second, excessive inflammation in COVID-19 may induce venous and arterial thromboembolism. The incidence of thrombus in ICU patients with COVID-19 was found to be as high as 31% [21]. Moreover, suspected sHLH leads to depletion of blood cells and can cause cytopenia such as thrombocytopenia [6]. Therefore, we expected that platelets would be much lower in suspected sHLH patients. In the present study, we observed that platelet count, a simple and readily available biomarker, lower than 101 × 109/L is an independent risk factor and can be used to differentiate patients with suspected sHLH in this severe COVID-19 cohort. Thus, high ferritin, hypertriglyceridemia and low platelets are predictive of sHLH and should be measured in patients with severe COVID-19, to identify and facilitate specific treatment of sHLH. In addition, the prediction value of “peak TG, ferritin, and low PLT” in COVID-19 patients were supported by a series of previous studies [22–24].

We found that 41 patients who fulfilled suspected sHLH probability diagnosis according to HScore succumbed to COVID-19, while suspected sHLH negative patients had a survival rate of 68.38%. One of the possible reasons for the high mortality is the lack of targeted-treatment for suspected sHLH. Adult HLH patients with dyspnea, diarrhea, diffuse bleeding, jaundice and septicemia accompanied by organ failure were characterized by extreme symptoms of severe suspected sHLH, which has very poor prognosis [25]. These signs and symptoms, along with significant disease progression, provide a risk signature for possible HLH, consistent with the clinical manifestations of COVID-19 with cytokine storm [26]. Recently research indicated that suspected sHLH related to COVID-19 received IL-6 antagonistic therapy and Anakinra (recombinant soluble receptor antagonist of IL-1β and IL-1α) [27, 28]. Several drugs targeting specific cytokines are in on-going clinical trials in patients with COVID-19 [29] and the earliest possible detection of sHLH is of the utmost importance.

Our study has several limitations. First, in the severe COVID-19 group, some cases of suspected sHLH may have been missed, suggesting that suspected sHLH may have been underestimated in this study. The lack of definite indicators in the 88 patients with HScore ranging between 98 and 169 could have led to the underestimation of suspected sHLH. Second, all patients lacked specific diagnostic indicators for sHLH, such as laboratory test assessing soluble CD25 and NK-cell activity due to insufficient medical resources to provide these tests during the COVID-19 outbreak. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to infer a definite causality between sHLH and severe COVID-19. Therefore, we selected HScores ≥169 as the positive cut-off value and HScores ≤98 as the negative cut-off value to prevent overestimating suspected sHLH in these patients. Third, the upper limit of detection for ferritin was 2000 ng/ml, which might reduce the specificity of ferritin as a predictor of suspected sHLH. Fourth, the clinical parameters of the liver/spleen and cytological results of bone marrow aspiration were virtually absent in all patients. Fifth, there is no second validation cohort for the prediction model. In order to overcome the question, internal validation was conducted using bootstrapping (1000 repetitions), the results achieved a C-index 0.863(95%CI 0.838–0.889).

Conclusion

Although HScore has been widely used in various infectious diseases to identify sHLH, the criteria were not specifically studied for use in COVID-19 patients. It is important to find the clinical markers that predict mortality in COVID-19 patients. We recommend HScore for early suspected sHLH screening in severe COVID-19 patients with high ferritin, high triglyceride and low platelet levels. Prospective studies are needed to inform whether it is possible to utilize these markers to determine suspected sHLH diagnosis to identify at-risk populations to target for HLH therapy in severe COVID-19 in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the healthcare workers who have been fighting against COVID-19 at the frontline. We would like to express our appreciation for all the patients included in this study as well as their families. We also would like to thank Wuhan Infectious Disease Hospital and all the staff members that have participated in the treatment of COVID-19 patients.

We express deep appreciation to Coopersmith CM, MD (Director of Emory Critical Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA) who edited this manuscript.

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Abbreviations

- sHLH

Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- COVID-19

Corona virus disease 2019

- HScore

Hemophagocytosis score

- EBV

Epstein-Barr Virus

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- AKI

Acute kidney injury; Fib, fibrin/fibrinogen

- DIC

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- SGOT

Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase

- ASAT

Recombinant aspartate aminotransferase

- APACHE II

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BUN

Blood urea nitrogen

- sCr

Serum creatinine

- IL-6

Interleukin − 6

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- PCT

Procalcitonin

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- CK-MB

Creatine kinase isoenzyme

- Hb

Haemoglobin; Tbil, total bilirubin

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- TG

Triglycerides

- NPPV

Non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation

- CRRT

Continuous renal replacement therapy

- AUC

Area under the curve

- C-index

Concordance index

- NK

Natural Killer

Authors’ contributions

MM, LMC and SZ were responsible for statistical analysis and figures construction. MM, XD, WZL and RRL wrote this manuscript and organized tables and figures. YXD, TW, YX, JL, YXH, YZC, SSH, ZLW and LDZ were responsible for medical information collection. HXD, YAL, YZC, SSH, ZLW and LDZ were responsible for data extraction and verification. AD, JMQ, and DCC designed and guided this study. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Funding

The study was supported by grants from the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission, China (No. 20Y11901700, No. 20DZ2200500) and a grant from the Shandong Science and Technology Commission, China (No. ZR2019MH016). The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Participant data without names and identifiers will be made available after approval from the corresponding author. After publication of study findings, the data will be available for others to request. The research team will provide an email address for communication once the data are approved to be shared with others.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of Wuhan Infectious Diseases Hospital granted a waiver of informed consent from study participants (KY-2020-03-01). The data used in this study was anonymised before its use.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. No individual person’s data was shown separately. All data are presented as a whole.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mei Meng, Limin Chen, Sheng Zhang, Xuan Dong and Wenzhe Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Djillali Annane, Email: djillali.annane@aphp.fr.

Jieming Qu, Email: jmqu0906@163.com.

Dechang Chen, Email: 15168887139@163.com.

References

- 1.Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, Oczkowski S, Levy MM, Derde L, Dzierba A, du B, Aboodi M, Wunsch H, Cecconi M, Koh Y, Chertow DS, Maitland K, Alshamsi F, Belley-Cote E, Greco M, Laundy M, Morgan JS, Kesecioglu J, McGeer A, Mermel L, Mammen MJ, Alexander PE, Arrington A, Centofanti JE, Citerio G, Baw B, Memish ZA, Hammond N, Hayden FG, Evans L, Rhodes A. Surviving Sepsis campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):854–887. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson J, Mafham M, Bell J, Linsell L, et al. Effect of Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: Preliminary Report. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colafrancesco S, Alessandri C, Conti F, Priori R. COVID-19 gone bad: a new character in the spectrum of the hyperferritinemic syndrome? Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(7):102573. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Samkari H, Berliner N. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2018;13(1):27–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1503–1516. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seguin A, Galicier L, Boutboul D, Lemiale V, Azoulay E. Pulmonary involvement in patients with Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Chest. 2016;149(5):1294–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/clinical-management-of-novel-cov.pdf?sfvrsn=bc7da517_10&download=true. Accessed 14 Mar 2020.

- 10.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120(4):c179–c184. doi: 10.1159/000339789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Touaoussa A, El Youssi H, El Hassani I, Hanouf D, El Bergui I, Zoulati G, Amrani HM. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: clinical and biological diagnosis. Ann Biol Clin. 2015;73(6):657–663. doi: 10.1684/abc.2015.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The third international consensus definitions for Sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn GD, Hayes P, Breen KJ, Schenker S. The liver in congestive heart failure: a review. Am J Med Sci. 1973;265(3):174–189. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197303000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, Marzac C, Aumont C, Chahwan D, Coppo P, Hejblum G. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2613–2620. doi: 10.1002/art.38690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, von Bahr GT, Machowicz R, Berliner N, Birndt S, Gil-Herrera J, Girschikofsky M, Jordan MB, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133(23):2465–2477. doi: 10.1182/blood.2018894618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khovidhunkit W, Memon RA, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Infection and inflammation-induced proatherogenic changes of lipoproteins. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl 3):S462–S472. doi: 10.1086/315611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mateo-Gallego R, Lacalle L, Pérez-Calahorra S, Marco-Benedí V, Recasens V, Padrón N, Lamiquiz-Moneo I, Baila-Rueda L, Jarauta E, Calmarza P, Cenarro A, Civeira F. Efficacy of repeated phlebotomies in hypertriglyceridemia and iron overload: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12(5):1190–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2018.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, Mehra MR, Schuepbach RA, Ruschitzka F, Moch H. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, Kaptein FHJ, van Paassen J, Stals MAM, Huisman MV, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020; published online March 3. 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Retamozo S, Brito-Zerón P, Sisó-Almirall A, Flores-Chávez A, Soto-Cárdenas M, Ramos-Casals M. Haemophagocytic syndrome and COVID-19. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;3(4):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05569-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mousavi SA, Rad S, Rostami T, Rostami M, Mousavi S, Mirhoseini S, Kiumarsi A. Hematologic predictors of mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a comparative study. Hematology. 2020;25(1):383–388. doi: 10.1080/16078454.2020.1833435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGonagle D, Sharif K, O'Regan A, Bridgewood C. The role of cytokines including Interleukin-6 in COVID-19 induced pneumonia and macrophage activation syndrome-like disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(6):102537. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.England JT, Abdulla A, Biggs CM, Lee AYY, Hay KA, Hoiland RL, Wellington CL, Sekhon M, Jamal S, Shojania K, Chen LYC. Weathering the COVID-19 storm: lessons from hematologic cytokine syndromes. Blood Rev. 2021;45:100707. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2020.100707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radbel J, Narayanan N, Bhatt PJ. Use of Tocilizumab for COVID-19-induced cytokine release syndrome: a cautionary case report. Chest. 2020;158(1):e15–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimopoulos G, de Mast Q, Markou N, Theodorakopoulou M, Komnos A, Mouktaroudi M, Netea MG, Spyridopoulos T, Verheggen RJ, Hoogerwerf J, et al. Favorable Anakinra Responses in Severe Covid-19 Patients with Secondary Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28(1):117–123.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson LA, Canna SW, Schulert GS, Volpi S, Lee PY, Kernan KF, Caricchio R, Mahmud S, Hazen MM, Halyabar O, Hoyt KJ, Han J, Grom AA, Gattorno M, Ravelli A, Benedetti F, Behrens EM, Cron RQ, Nigrovic PA. On the alert for cytokine storm: immunopathology in COVID-19. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(7):1059–1063. doi: 10.1002/art.41285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Participant data without names and identifiers will be made available after approval from the corresponding author. After publication of study findings, the data will be available for others to request. The research team will provide an email address for communication once the data are approved to be shared with others.