Abstract

Reverse ecology is the inference of ecological information from patterns of genomic variation. One rich, heretofore underutilized, source of ecologically relevant genomic information is codon optimality or adaptation. Bias toward codons that match the tRNA pool is robustly associated with high gene expression in diverse organisms, suggesting that codon optimization could be used in a reverse ecology framework to identify highly expressed, ecologically relevant genes. To test this hypothesis, we examined the relationship between optimal codon usage in the classic galactose metabolism (GAL) pathway and known ecological niches for 329 species of budding yeasts, a diverse subphylum of fungi. We find that optimal codon usage in the GAL pathway is positively correlated with quantitative growth on galactose, suggesting that GAL codon optimization reflects increased capacity to grow on galactose. Optimal codon usage in the GAL pathway is also positively correlated with human-associated ecological niches in yeasts of the CUG-Ser1 clade and with dairy-associated ecological niches in the family Saccharomycetaceae. For example, optimal codon usage of GAL genes is greater than 85% of all genes in the genome of the major human pathogen Candida albicans (CUG-Ser1 clade) and greater than 75% of genes in the genome of the dairy yeast Kluyveromyces lactis (family Saccharomycetaceae). We further find a correlation between optimization in the GALactose pathway genes and several genes associated with nutrient sensing and metabolism. This work suggests that codon optimization harbors information about the metabolic ecology of microbial eukaryotes. This information may be particularly useful for studying fungal dark matter—species that have yet to be cultured in the lab or have only been identified by genomic material.

Bias toward codons that match the tRNA pool is robustly associated with high gene expression in diverse organisms, suggesting that codon optimization could be used in a reverse ecology framework to identify ecologically relevant genes. This study finds that this is indeed the case for 329 species of budding yeasts, suggesting that codon optimization harbors information about the metabolic ecology of microbial eukaryotes.

Introduction

The immense diversity of life is due, in part, to adaptation to the wide variety of environmental niches available. By acting on the interface between genotype, phenotype, and environment, natural selection has given rise to numerous ecological adaptations [1–3]. Elucidating the precise relationship between genotype, phenotype, and environment, however, is often challenging. For example, a connection was only recently made between environmental distribution of seeds of different sizes, phenotypic variation in the beaks of Darwin’s finches, and changes in the expression of the protein BMP4 [4–6].

Genomic sequencing has accelerated the rate at which the underlying genomic mechanisms of well-established ecologically adapted phenotypes are elucidated [7,8]. While powerful, this type of ecological genomics requires extensive knowledge of the ecological niche in which species live. For many microbial species, however, detailed ecological information is unavailable due to both the scale of the ecosystems they live in and the dearth of information reported during collection [9]. One potentially powerful way to address this gap in knowledge is to use the extensive genomic resources available in microbes to conduct reverse ecology—directly predicting ecology from genotype [10,11].

Reverse ecology has been successful in broadly linking environmental phenotype with genotype using multiple types of genomic features [11–13]. Optimal growth temperature was successfully inferred from genomic content, including tRNA, ribosome, and gene features, in 549 Bacteria and 170 Archaea [14]. In the red bread mold Neurospora crassa, analysis of highly divergent genomic regions in 48 isolates uncovered “genomic islands” associated with adaptation in 2 different ecosystems [15]. Across the entire tree of life, metabolic capability (assessed using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) gene annotations) was used to examine the evolution of exogenously required metabolites likely found in the environment [16]. Metabolic network analysis has emerged as a common genomic feature for reverse ecology analysis [17,18]. There are, however, other promising genomic features that can be used in reverse ecology.

One potentially useful but underutilized genomic feature for reverse ecology studies is codon usage, which has long been associated with gene expression [19–21]. Changes in gene expression have been shown to play an important role in ecological adaptation [22–24]. For example, in wild isolates of budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, changes in the expression of multiple genes were linked to phenotypic differences in copper resistance and pigmentation, which in turn may be associated with adaptation to high copper environments [25]. Over evolutionary time, increased levels of gene expression result in a selective pressure for accurate and efficient translation [26–30] and increased mRNA stability [31,32]. Codons that match the tRNA pool—called optimal codons—have a substantial impact on both translation [27,29,30] and mRNA stability [31]. Therefore, optimal codon usage is correlated with high gene expression in multiple lineages, especially in microbes [19,33–38]. Moreover, codon usage has both a mechanistic role (as a contributing factor to gene expression) and an evolutionary role (as an adaptation of moderately or highly expressed genes over time) within organisms. Therefore, we hypothesize that ecological adaptations that are, at least partly, due to high expression levels of specific genes or pathways will be reflected in their codon usage values.

Previous work in diverse microbes supports the hypothesis that codon optimization can be used to identify associations between codon usage and ecology [12,39–43]. For example, an analysis of metagenomes collected from mine biofilms shows an enrichment of optimal codons in bacterial and archaeal genes associated with inorganic ion transport [39]. In fungi, codon optimization in host-induced and secreted proteins is associated with generalist fungal parasites [41]. Although these studies were highly successful in linking particular ecological niches with highly enriched groups of genes, we still lack examples where reverse ecology has linked particular ecologies to specific metabolic pathways.

The galactose (GAL) pathway (also known as the Leloir pathway) in the budding yeast subphylum Saccharomycotina is an iconic pathway that metabolizes galactose into glucose-1-phosphate, which can then be used in core metabolism or as an intermediate in other metabolic processes [44,45]. The genes encoding the 3 enzymes of the GAL pathway—GAL1 (encoding a galactokinase), GAL10 (encoding a UDP-glucose-4-epimerase), and GAL7 (encoding a galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase)—are frequently clustered in yeast genomes and are induced in response to the presence of galactose [46–48]. There has been extensive research into the biochemistry [44], regulation [49–51], and evolutionary history [48,52] of this pathway. Ecological work on the GAL pathway revealed that gene inactivation is associated with an ecological shift in Saccharomyces kudriavzevii, a close relative of the species to S. cerevisiae [53]. There is also a positive association between galactose metabolism ability and the flower/Ipomoea isolation environment and a negative association between galactose metabolism ability and tree or insect frass isolation environments [54]. By identifying organisms that can grow in particular substrates, analyses of gene gain and loss give us insights into ecological adaptation; however, such analyses do not tell us how well organisms grow in these substrates—addressing this question requires understanding of variation in gene expression of the genes involved [55–57]. The recent publication of 332 budding yeast genomes and the identification of translational selection on codon usage in a majority of these species provide a unique opportunity to test for differences in GAL gene expression—inferred from optimal codon usage—across ecological niches inferred from recorded isolation environments [54,58–60].

In this study, we characterize the presence and codon optimization of the GAL pathway in 329 budding yeast species and identify an association between optimization in the GAL pathway and 2 specific ecological niches. We identify a complete set of GAL genes in 210 species and evidence of physical clustering of GAL1, GAL7, and GAL10 in 150 species. Consistent with our hypothesis that codon optimization is a signature of high gene expression, we find that growth rate on galactose-containing medium is positively and significantly correlated with GAL codon optimization. In the CUG-Ser1 major clade, which contains the opportunistic human pathogen Candida albicans, codon optimization in the GAL pathway is higher in species found in human-associated ecological niches when compared to species associated with insect (and not human) ecological niches. In the family Saccharomycetaceae, another major clade in the subphylum Saccharomycotina that contains the model species S. cerevisiae, we find that codon optimization in the GAL pathway is higher in species isolated from dairy-associated niches compared to those from alcohol-associated niches. For example, codon optimization among closely related Kluyveromyces species is nearly twice as high in species isolated from dairy niches as those found associated with marine or fly niches. We also used KEGG Orthology (KO) annotations to find genes whose codon optimization correlated with GAL optimization. Many of the top hits in this analysis are known to be involved in sensing or regulating sugar metabolism in yeasts. These results suggest that codon optimization is a valuable genomic feature for linking metabolic pathways with ecological niches in microbes.

Methods

Galactose (GAL) pathway characterization

Genomic sequence and gene annotation data were obtained from the comparative analysis of 332 budding yeast genomes [58] (S1 Data). Mitochondrial sequences were filtered from these genomes using previously described methods [59]. Reference protein sequences for GAL gene annotation (approximately 40 proteins for each of the GAL genes) and for PMI40 gene annotation, which is involved in mannose assimilation and was used as a negative control (315 reference proteins), were obtained from GenBank and previous KO annotations [58,61]. A protein HMM profile was constructed for each gene and used to conduct 2 HMMER searches (version 3.1b2; http://hmmer.org/), one on publicly available annotations and one on all possible open reading frames generated using ORFfinder (version 0.4.3; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/). The search on all possible open reading frames was done to ensure that inferences of gene absences were not due to errors in publicly available gene annotations. The results of the 2 searches were compared using the Perl script fasta_uniqueseqs.pl (version 1.0; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/CBBresearch/Spouge/html_ncbi/html/fasta/uniqueseq.cgi). Discrepancies between the 2 searches, which most often occurred in cases where the publicly available annotation combined 2 nearby genes, were resolved manually. The genes GAL1 and GAL3 are known ohnologs (i.e., paralogs that arose from a whole genome duplication event) [62,63]. We annotated ohnologs as GAL3 only in the lineage where previous work has demonstrated a divergent function [51]. All other GAL1 homologs were included in subsequent analyses as there is a lack of evidence for functional divergence [51]. All reference and annotated GAL and PMI40 genes are available in the supplementary FigShare repository. All instances where GAL1, GAL7, and GAL10 were found on the same contig were considered to represent GAL gene clusters.

Codon optimization in the GAL pathway

To infer gene expression in the GAL pathway, we calculated the species-specific level of codon optimization in each GAL gene and compared it to the genome-wide distribution of codon optimization. Codon optimization of individual GAL genes was assessed by calculating the species-specific tRNA adaptation index (stAI) from previously calculated species-specific codon relative adaptiveness (wi) values [59,64]. Briefly, the species-specific codon relative adaptiveness values were calculated using stAI-calc [65] based on the genomic tRNA counts, optimized tRNA wobble weights, and genome-wide codon usage. Three species that previously failed to generate reliable wi values (Martiniozyma abiesophila, Nadsonia fulvescens var. elongata, and Botryozyma nematodophila) [59] were removed from all subsequent analyses. The stAI software does not take into account the CUG codon reassignment in the CUG-Ser1 and CUG-Ala clades. Previous analysis, however, suggests that this codon is rare [59]—the average frequency of the CUG codon in species where it has been reassigned is 0.005, 0.003, and 0.006 for GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7, respectively—and its influence on codon optimization calculations is not significant.

The stAI or species-specific tRNA adaptation index for each gene was calculated by taking the geometric mean of the previously calculated wi values for all the codons, except the start codon. The genome-wide distribution of gene stAI values is normally distributed, but the mean varies between species [59]. To compare codon optimization between species, we normalized each gene’s stAI value using the empirical cumulative distribution function to get the percentage of all genes with stAI values lower than that of the gene of interest; we call this the estAI value. For example, an estAI value of 0.4 for a given gene would indicate that 40% of the genes in the genome have lower stAI values (i.e., are less optimized) than the gene of interest. The estAI optimization values therefore range from 0 to 1, with 1 being the most optimized gene in the genome. Codon optimization of the mannose metabolism gene PMI40 was calculated in the same way as the GAL genes.

A total of 49 species’ genomes had multiple copies of at least one GAL gene. For those genomes, the gene with the highest estAI value was used. For example, we identified 2 copies of GAL10 in Candida ponderosae located on different contigs with estAI values of 0.46 and 0.44. Therefore, we used the estAI value of 0.46 as the representative GAL10 value for this species. The average difference between the maximum and minimum estAI for multiple copies of GAL1, GAL7, and GAL10 are 0.0948, 0.0007, and 0.0125. There were 14 cases where all gene copies with the highest estAI values were not found on the same contig. In 18 cases, all duplicates with the highest estAI values were located on the same contig. The use of the GAL gene copy with the highest estAI is supported by evidence in S. cerevisiae that functionally derived gene duplicates have reduced codon optimization, which is likely linked to an evolutionary trajectory toward novel functions [66]. To test the assumption that the majority of ohnologs have diversified in function or are undergoing decay and are therefore unrelated to growth rate, we examined the relationship between copy number and growth rate. We conducted a comparative analysis using generalized estimating in R using the package ape (v5.3) [67,68], which allowed us to phylogenetically compare categorial data (single versus multiple GAL genes) and continuous data (growth rate). Within the Saccharomycetaceae, the presence of multiple GAL gene copies showed no significant correlation with growth rate on galactose containing medium (p-values of 0.85, 0.72, and 0.06 for GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7; full analysis on FigShare).

Galactose growth data

To test the hypothesis that high levels of GAL codon optimization are associated with strong growth in media where galactose is the sole carbon source, we measured galactose, mannose, and glucose (as a control) growth for 258 species in the laboratory. Yeast strains corresponding to the species whose genomes were sequenced were obtained from the USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) NRRL Culture Collection in Peoria, Illinois, United States of America, or from the Fungal Biodiversity Centre (CBS) Collection in the Netherlands. All strains were initially plated from freezer stocks on yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) plates and grown for single colonies. YPD plates were stored at 4°C until the end of the experiment. To quantify growth on galactose, mannose, and glucose, we set up 3 replicates on separate weeks using different colonies for each strain. Strains were inoculated into liquid YPD and grown for 6 days at room temperature. For each replicate, strains were randomized and arrayed into a 96-well plate. The plate was then used to inoculate strains into a minimal medium containing 1% carbon source (D-galactose, 1% mannose, or 1% glucose), 5 g/L ammonium sulfate, and 1.7 g/L Yeast Nitrogen Base (w/o amino acids, ammonium sulfate, or carbon) and grown for 7 days. After a week, we transferred all strains to a second 96-well plate containing fresh minimal medium containing the carbon source.

To quantify the growth of each strain/species, we measured its optical density (OD units at 600 nm) following growth in a well of a BMG LABTECH FLUOstar Omega plate reader after a week at room temperature. We calculated 2 measures of growth, growth rate and endpoint, for each species and replicate. The growth rates were calculated in R (x64 3.5.2) using the grofit package (v 1.1.1.1), and end point, a proxy for saturation, was calculated by subtracting the T0 time point from the final time point for each species. The growth rate was calculated as the maximum slope of the growth curve (S2 Fig) We visually assessed growth on galactose and mannose for all species using the growth curves we collected; a species was denoted as having the ability to grow on galactose or mannose if it grew in at least 2 of 3 replicates tested. Growth data, both growth rate and endpoint, were set to 0 for all species that did not meet this requirement. Quantitative growth on galactose was successfully measured for a total of 258 species. Growth on galactose or mannose was then computed relative to glucose, by dividing the growth rate by the rate measured on galactose, to account for differences in the baseline growth rate of different species due to variables, such as cell size and budding type (unipolar versus bipolar). Therefore, a growth rate on galactose- (or mannose-) containing medium of 1 indicates that this species grew equally as quickly on galactose (or mannose) and glucose, whereas a growth rate of 0.5 indicates this species grew half as quickly on galactose (or mannose) as it did on glucose.

For the 71 species where new quantitative galactose growth data were unavailable, we used previously published species-specific binary growth data [54,58,60]. Uncertain growth is indicated where conflicting or variable growth was found in the literature (empty green triangles; Fig 1B). Quantitative galactose growth data (normalized to glucose) were compared to maximum gene codon optimization values using phylogenetically independent contrasts (PIC) [69]. Data from related species are not independent observations and therefore require a PIC analysis to ensure that covariation between traits is not the result of the relatedness of species [69]. The PIC analysis was conducted in R using the ape package (v5.3) [68]. The species Metschnikowia matae var. matae was removed from this analysis as it was a clear outlier on the residual plots for a complementary phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS) analysis (S3 Fig) [70,71]. Outliers in phylogenetically independent analyses occur when 2 closely related taxa have disparate trait values, which can be identified by examining the residual plots. In this case, the taxa Metschnikowia matae var. maris (strain yHMPu5000040795 = NRRL Y-63737 = CBS 13985) and Metschnikowia matae var. matae (strain yHMPu5000040940 = NRRL Y-63736 = CBS 13986) are very closely related, and yet the growth rate on galactose for Metschnikowia matae var. matae (1.390) is nearly double that of its closest relative Metschnikowia matae var. maris (0.750). The next most closely related species Metschnikowia lockheadii had a growth rate most similar to M. matae var. maris (0.567).

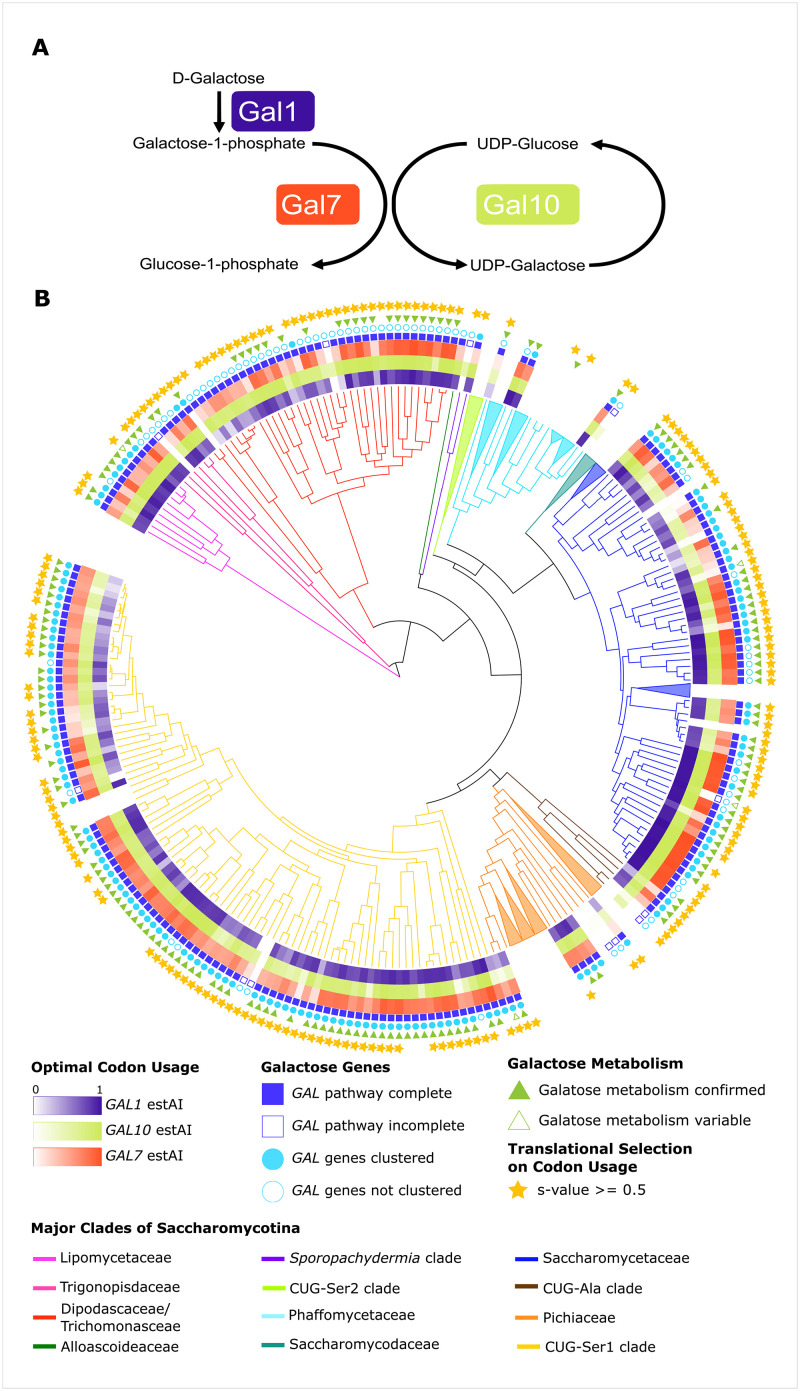

Fig 1. The GAL pathway and the distribution of galactose metabolism, GAL genes, and preferred codon usage across the Saccharomycotina.

(A) The 3 enzymes of the GAL pathway metabolize galactose into glucose-1-phosphate, which can then enter glycolysis after being converted into glucose-6-phosphate. (B) Various features of galactose metabolism plotted on a phylogeny of the budding yeast subphylum Saccharomycotina; the 12 major clades of the subphylum are color coded. The presence and codon optimization (measured by estAI) of the 3 GAL genes are represented in the inner 3 rings. Clades with 3 or more species without a complete GAL pathway were condensed and are shown as triangles; for the full tree, see S1 Fig. The GAL clusters in the Dipodascaceae/Trichomonascaceae, Pichiaceae, and Phaffomycetaceae were recently found to have likely originated from horizontal gene transfer events from the CUG-Ser1 clade [72]. We did not identify any GAL genes from species in the CUG-Ser2 clade or the family Saccharomycodaceae. In every other major clade examined, we identified complete and clustered occurrences of the GAL pathway (filled-in blue squares and circles, respectively.) High codon optimization (darker colors) in the GAL pathway is not restricted to any one major clade. The ability to metabolize galactose (filled-in green triangle) was assessed either experimentally in this study or taken from the literature. In some instances, where only literature data were available, there were conflicting or variable reports of galactose metabolism (5 species; empty green triangles). The majority of species in the Saccharomycotina have also been shown to have genome-wide selection on codon usage (denoted by the yellow stars) [59]. Species names and ecological information can be found in S1 Fig and Table A S1 Data.

As negative controls of the specificity of the association between gene codon optimization and growth rate, we also compared the optimization of the mannose metabolism gene PMI40 to growth rate on mannose- and galactose-containing media as well as the codon optimization of the GAL genes to growth rate on mannose.

Prediction of growth rate from unsampled genomes

To test the predictive ability of the observed correlation between GAL codon optimization and growth rate on galactose-containing medium, we analyzed the publicly available genomes of 2 species not included in the original 332 species analyzed: Kluyveromyces wickerhamii (GCA_000179415 [73], UCD 54–210) and Wickerhamiella occidentalis (GCA_004125095, NRRL Y-27364 [74]). To obtain the stAI for each species, we first annotated each genome using AUGUSTUS [75] (v 3.2.3) trained on S. cerevisiae gene models. We then filtered out any coding sequences shorter than 500 nucleotides. The remaining coding sequences were then run through stAI-calc to obtain the species-specific wi values for each codon. Annotations and genes can be found on the FigShare repository.

We tested for translational selection on codon usage (S-test), annotated the GAL genes, calculated the estAI values for the GAL genes, and measured growth rate on galactose-containing medium standardized to growth rate on glucose-containing medium; we used the same approaches as for the analyses of the 332 genomes. We then used PGLS regression to predict growth rate on galactose-containing medium from the codon optimization values observed in each gene (we used the PGLS in this analysis because the PGLS transforms the regression, allowing us to estimate growth rate without transforming the raw growth data). These predictions can be improved in the future with the addition of a robust phylogeny including all species. We then compared how good our predictions were relative to the predictions made on simulated sequences whose codon assignment was random. To do this, we generated 1,000 coding sequences with identical amino acid sequences to the observed GAL protein that had randomly assigned codon usage (data and custom perl script can be found on the FigShare repository). Based on the distribution of the growth rates of the random coding sequences, we then determined if the actual and predicted growth rate values fell within or outside the 95% confidence interval.

Ecological association analysis

To test for associations between GAL pathway codon optimization and ecological niche, we obtained species-specific isolation data from multiple sources. We first tested 50 isolation environments from data collated from The Yeasts: A Taxonomic Study [60], as recorded by Opulente and colleagues [54,58]. We compared codon optimization in each of the GAL genes between species isolated from a given environment versus species not isolated from that environment (S4 Fig). From this analysis, we identified 4 general ecological niches with potentially differential codon optimization: dairy-, alcohol-, insect-, and human-associated ecological niches. To validate and update the data from The Yeasts, we conducted an in-depth literature search for these 4 specific ecological niches for each of the 329 species of interest using all known anamorphs and synonyms per species (see S2 Data for updated information for the ecological niches and associated references). Dairy ecological niches identified included milks, butters, cheeses, and yogurts. Alcohol ecological niches identified included spontaneous beer fermentation, alcohol starters, wine, ciders, kombuchas, and liquors. Insect-associated ecological niches included insect guts, insect bodies, and insect frass. Human-associated ecological niches were characterized as any isolation from a human, regardless of pathogenicity. We did not take into account studies where species identification lacked genetic data and relied solely on phenotypic and assimilation data, because these identifications have been shown to be potentially unreliable [76–78]. For example, the only evidence that the species Candida castellii is associated with dairy niches comes from a single identification in a fermented milk product using only metabolic characterization [79]. Therefore, C. castellii was not considered associated with dairy niches.

To test for significant differences in GAL optimization between ecological niches, we first filtered the species set to retain only those that contain all 3 GAL genes (210 species) and that were previously shown to exhibit genome-wide selection on codon usage (266 species; s-value > = 0.5) [59]; thus, the total number of species tested was 170. We then compared levels of GAL codon optimization between ecological niches using the Wilcoxon rank sum test in R [80].

Evolutionary rate analysis

To examine variation in the evolutionary rates among both GAL and a representative set of genes in the genome, we used the maximum likelihood software PAML (version 4.9) [81,82]. Specifically, we examined the rates of synonymous changes in the Kluyveromyces species using the free-ratios model that allows for a different rate of evolution along each branch. The species tree was used as the input tree, and nucleotide sequences were aligned using the codon aware software TranslatorX (http://translatorx.co.uk/) [83]. For the analysis of a representative set of genes in the genome, we identified 651 previously annotated BUSCO genes [58] present in all four Kluyveromyces species for which the confidence interval was <10 for all PAML-inferred branch lengths. We then compared the distribution of BUSCO genes’ branch lengths within each species with those observed for the GAL genes. These data can be found on the FigShare repository.

Identification of additional metabolic pathways whose codon usage correlates with GAL optimization

To identify additional pathways that exhibit the same codon optimization trends between ecological niches as the GAL pathway, we tested whether the optimization of KOs was correlated with that of the GAL genes. KO annotations were previously generated for all species [58]. We started with the 266 genomes with evidence of translational selection on codon usage and identified 2,573 KOs present in 100 or more of those species. We then conducted a PIC analysis between the optimization of the GAL genes and each of the KOs across the species. p-values were adjusted to account for the total number of KOs tested using a Bonferroni correction (S3 Data).

Results and discussion

Variable GAL pathway and codon optimization across the Saccharomycotina

To examine variation in GAL codon optimization across the subphylum, we first examined whether GAL genes were present in each of the 329 genomes. Across the Saccharomycotina, we annotated 742 GAL genes (265, 256, and 221 annotations for GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7, respectively) in a total of 233 species (S1 Data and FigShare repository). The complete GAL enzymatic pathway (i.e., GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7) was identified in 210 species, of which 149 had evidence of GAL gene clustering. We cannot, however, rule out clustering of the GAL genes in the remaining 61 species as some of the annotations were at the ends of the contigs.

There were some discrepancies between galactose growth data and GAL gene presence data. Three species where galactose growth was experimentally observed lacked all 3 GAL genes: Ogataea methanolica, Wickerhamomyces sp. YB-2243, and Candida heveicola. The growth rates for these species are 0.129, 0.339, and 0.211 for O. methanolica, Wickerhamomyces sp., and C. heveicola. The low growth rates (seventh and third lowest overall) of O. methanolica and C. heveicola suggest these species may be utilizing trace amounts of other nutrients present in the medium. Finally, there were 26 species with a complete GAL gene cluster where no growth on galactose has been reported. This may represent a loss of pathway induction in these species or an inability to induce growth in the specific experimental conditions tested, as observed previously in the genus Lachancea [84]. Inactivation of the GAL pathway has also occurred multiple times in budding yeasts [48,53], and some of these taxa could be in the early stages of pathway inactivation.

Codon optimization in the GAL pathway, measured by estAI, varied greatly across the Saccharomycotina (Fig 1B.) The estAI values ranged from 0.02 (or greater than only 2% of the genes in the genome) in GAL7 from Lachancea fantastica nom. nud. to 0.99 (or greater than 99% of the genes in the genome) in GAL1 from Kazachstania bromeliacearum. To determine if there was an association between codon optimization and the ability to grow on galactose, we compared optimization in the GAL pathway between species that are able and unable to grow on galactose. We found that species without evidence for growth on galactose had significantly lower (p < 0.05) codon optimization in their GAL1 and GAL7 genes and that optimization in GAL7 and GAL10 was significantly lower (p < 0.05) in species with only a partial pathway (S5 Fig). Interestingly, the dataset contained no species with a partial GAL pathway containing GAL1. These correlations are consistent with a relaxation of selective pressures in nonfunctional pathways [85–87], and previous work has identified multiple parallel inactivation events of the GAL pathway in budding yeasts [53]. The GAL pathway may have alternative roles in cell function that are not associated with growth on galactose and may have not experienced the same selective pressures. For example, in C. albicans, GAL10 has been shown to be involved in cell integrity [88]. Finally, the GAL pathway may have an alternative induction system in these species. For example, the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (not a member of the Saccharomycotina) has a complete GAL cluster but is unable to grow on galactose. Mutants of S. pombe, however, have been isolated that constitutively express the GAL genes and can grow on galactose [89].

GAL codon optimization is correlated with growth rate on galactose

Strong translational selection on codon usage is correlated with highly expressed genes in diverse organisms [34,35,37,90–94]. Therefore, we hypothesized that high levels of codon optimization in the GAL pathway reflect high levels of GAL gene expression and ultimately high growth rates on galactose. Previous work in the closely related budding yeasts S. cerevisiae and Saccharomyces uvarum suggests that the more robust growth of S. uvarum on galactose is associated with multiple underlying genetic differences that make the GAL network more active in this species [51,52,84,95]. The 2 species’ differences in growth rate on galactose and in GAL network activity are reflected in their GAL gene codon optimization values. Even though the GAL genes of S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum have high amino acid sequence identity (88.6%, 87.4%, and 88.6% for GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7, respectively), all 3 genes are more highly optimized in S. uvarum compared to S. cerevisiae (0.78 versus 0.70 for GAL1, 0.66 versus 0.46 for GAL10, and 0.55 versus 0.33 for GAL7). These results suggest that, over evolutionary time, a higher growth rate associated with increased flux through this pathway has resulted in a higher optimization of the GAL genes in S. uvarum.

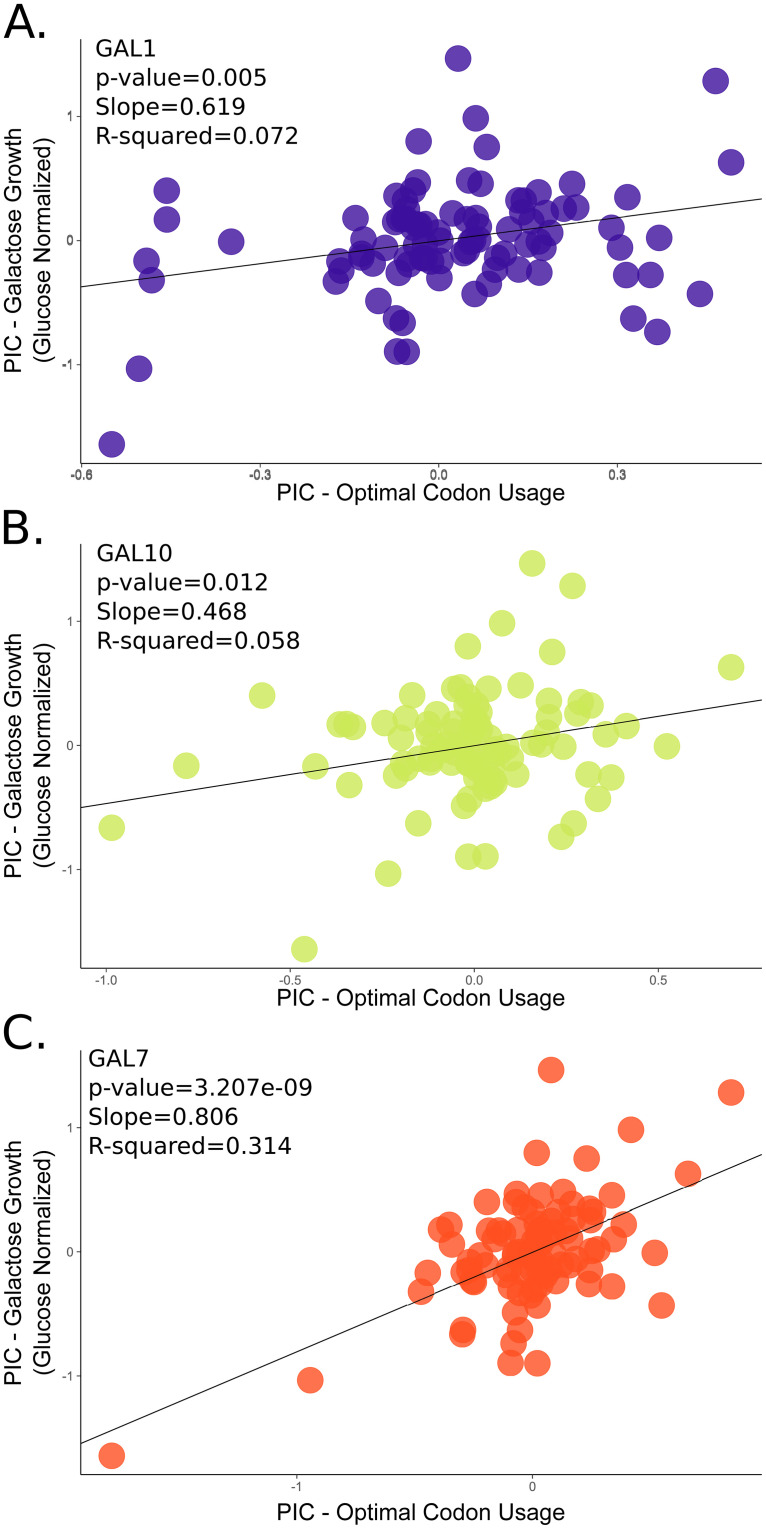

Across the budding yeasts, we measured growth rate on galactose relative to glucose. We found a significant positive correlation between growth rate on galactose-containing medium and codon optimization in the GAL pathway of species that can grow on galactose and whose genomes have experienced translational selection on codon usage (N species = 94, linear regression of PIC values; p-values of 0.005, 0.012, and 3.207e−9 for GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7, respectively; Fig 2). Codon optimization of GAL7 showed the strongest correlation with growth rate (Fig 2C), which may reflect the gene’s function; GAL7 encodes for the enzyme that metabolizes galactose-1-phosphate, a toxic intermediate [96,97] whose accumulation has been shown to reduce growth rate in S. cerevisiae [97]. Furthermore, the correlation between GAL7 optimization and growth rate on galactose remained strong when analyzed independently in both the Saccharomycetaceae (29 species) and in the CUG-Ser1 clade (47 species; S6 Fig), the 2 largest clades sampled. Furthermore, the GAL7 correlation was higher than additive models that included more than one gene—the second-best model correlated codon optimization with GAL7 and GAL10 with growth rate on galactose (p-value of 1.82e−8). The GAL1 and GAL10 genes were both significantly positively associated with growth rate in galactose in the Saccharomycetaceae, but not in the CUG-Ser1 clade (S6 Fig). This contrast may reflect the different regulatory mechanisms involved in galactose assimilation in the 2 major clades—tight control via a regulatory switch in the Saccharomycetaceae versus leaky expression in CUG-Ser1 [49,50]. We also tested the correlation between growth rate on galactose-containing medium and the PGM1 and PGM2 genes that encode phosphoglucomutases, enzymes that operate downstream of the galactose metabolism pathway by converting glucose-1-phosphate (Fig 1) to glucose-6-phosphate, which can enter glycolysis. There was no correlation between codon optimization in either PGM1 or PGM2 and growth on galactose-containing medium (S7 Fig). This result is likely due to the fact that both genes are involved in multiple metabolic pathways in addition to galactose metabolism.

Fig 2. Codon optimization in the GAL pathway is positively and significantly correlated with growth rate on galactose.

Phylogenetically independent contrasts (PIC) analyses of galactose growth (y axis) versus GAL gene optimal codon usage (x axis) in species that grow on galactose containing medium. Each point represents an independent contrast calculated between 2 species for either optimal codon usage or growth. A plot of the uncorrected data can be found in S11 Fig. There is a significant and positive correlation between the PIC values for codon optimization and galactose growth in GAL1 (A), GAL10 (B), and GAL7 (C). The best fit and strongest correlation is between growth on galactose and optimization in GAL7 (C). The analyses included 94 species with a growth rate on galactose greater than 0, a complete GAL cluster, and evidence of genome-wide translational selection on codon usage. One species, Metschnikowia matae var. matae, was removed as an obvious outlier based on residual analysis. Underlying data can be found in Tables B–D S4 Data.

To test the specificity of the observed correlation between GAL genes and growth on galactose, we examined whether GAL genes correlated with growth on mannose-containing medium, as well as whether codon optimization of the well-characterized mannose metabolism gene PMI40 correlated with growth on galactose [98]. Codon optimization of PMI40 did not correlate with growth rate on galactose (p-value 0.61 and R-squared −0.0079; S8 Fig). Similarly, GAL gene optimization did not correlate with growth rate on mannose (p-values of 0.97, 0.92, and 0.11 for GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7, respectively; S9 Fig). Interestingly, the average PMI40 codon optimization was very high (0.84) and not well correlated with growth rate on mannose (p-value 0.54 and R-squared −0.0048; S10 Fig). This suggests not only that PMI40 is highly expressed regardless of metabolic state but also that optimization in some pathways may better correlate with growth rate than in others. Nevertheless, these results illustrate that the codon optimization in GALactose metabolism genes is specifically correlated with growth rate on galactose. Collectively, our findings support the hypothesis that codon optimization is the result of selection on codon usage in species with high GAL gene expression.

Can we predict growth rate on galactose from GAL codon optimization data?

To examine if our analysis enables the prediction of growth rate on galactose-containing media, we analyzed the codon optimization of the GAL pathway in 2 species not included in the original dataset—K. wickerhamii (Saccharomycetaceae) and W. occidentalis (Dipodascaceae/Trichomonascaceae clade). Both species have evidence of translational selection on codon usage based on the S-test (s-values of 0.58 for K. wickerhamii and 0.68 for W. occidentalis). The growth rate values predicted for K. wickerhamii from the GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7 codon optimization values were 0.65, 0.44, and 0.47, respectively (S11 Fig). The growth rate of K. wickerhamii measured in the laboratory was 0.58. For W. occidentalis, we predicted growth rate values of 0.53, 0.54, and 0.76 based on GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7 codon optimization values, respectively (S11 Fig). The growth rate measured in the laboratory was 0.86.

To better understand the performance of our growth rate predictions based on codon optimization values, we tested how well GAL genes with randomly assigned codons could predict growth rate. For both species, the predicted and the actual growth rates fell outside of the 95th percentile (S12 Fig). Additionally, for all but one observation (GAL7 in K. wickerhamii), the predictions and actual growth rate fell outside the 99th percentile. These results suggest that the prediction of galactose growth rate from GAL codon optimization in budding yeasts is highly informative. Future sequencing and growth characterization currently underway across the Saccharomycotina will provide additional data for model development and validation.

GAL codon optimization is associated with specific ecological niches

We further hypothesized that adaptation to specific ecological niches is associated with increased expression of the GAL pathway. To identify possible associations between GAL optimization and ecology, we conducted preliminary tests across 50 previously characterized ecological niches [54,60] for 114 species. This analysis led to an extensive literature search for 4 ecological niches of interest—dairy, alcohol, human, and insect—to maximize the number of species with ecological information. We uncovered 2 examples of niche-specific codon optimization (Fig 3): in the CUG-Ser1 clade, we found that GAL gene optimization was significantly higher in species that have been isolated from human-associated ecological niches versus those that have been isolated from insect-associated niches; and in the Saccharomycetaceae, we found GAL gene optimization was significantly higher in species isolated only from dairy-associated niches compared to species isolated only from alcohol-associated niches. Differential codon optimization between environments could be due to selection for increased optimization, a relaxation of selection, or selection for nonoptimal codon usage. While we are unable to differentiate between these scenarios, the elevated codon optimization of the GALactose genes relative to each species’ genome-wide distribution suggests that translational selection on codon usage has occurred in this pathway.

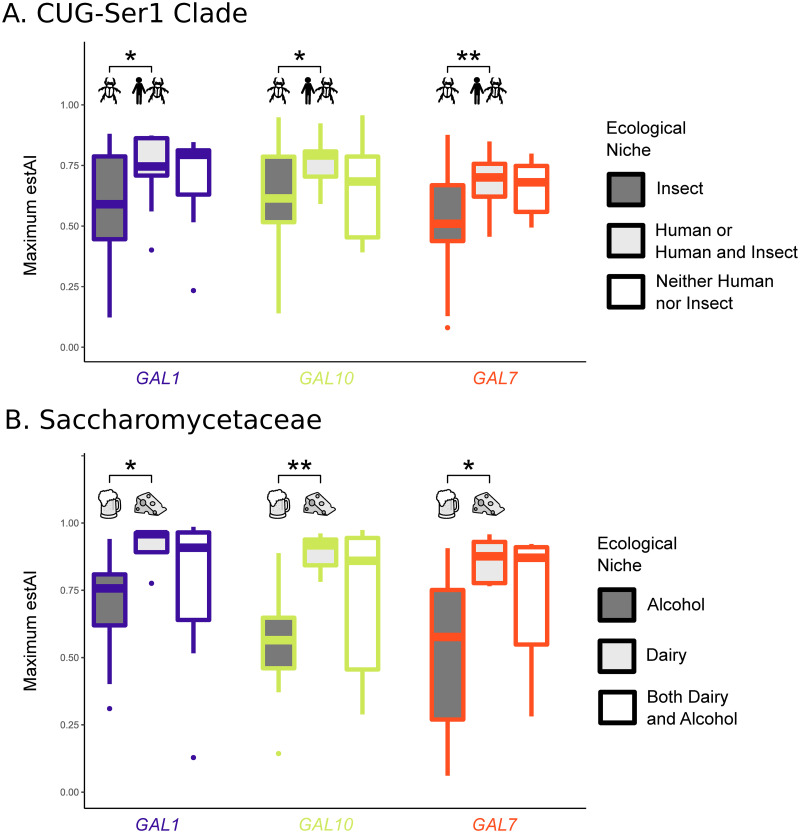

Fig 3. Codon optimization in the GAL pathway is correlated with specific ecological niches in 2 different major clades of budding yeasts.

p-values less than 0.01 are indicated with ** and less than 0.05 with *. (A) In the CUG-Ser1 clade, species associated with a human niche or human and insect niches (13 species) have significantly higher codon usage optimization values in all GAL genes (p-values of 0.022, 0.028, and 0.006 for GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7, respectively) when compared to species that are associated with insect niches but not human niches (44 species). Only 11 species were not associated with either human or insect niches. (B) In the Saccharomycetaceae, species associated with only dairy niches (5 species) have significantly higher codon usage optimization values in all of the GAL genes (p-values of 0.010, 0.002, and 0.014 for GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7, respectively) versus species associated with only alcohol niches (14 species). A total of 9 species are associated with both dairy and alcohol niches. Underlying data can be found in Tables E and F S4 Data.

CUG-Ser1 clade: Among CUG-Ser1 species that exhibit high genome-wide evidence of translational selection on codon usage (s-value ≥ 0.5), we found that GAL gene optimization was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in species from human-associated ecological niches or human- and insect-associated niches versus those that have been isolated from insect-associated niches only (57 species; Fig 3A). Only 2 species were found in human-associated niches and not insect-associated niches, Debaryomyces subglobosus and Cephaloascus fragrans; thus, we combined the human-associated species with the human- and insect-associated species into one group for subsequent analyses. Recent work has shown that many opportunistically pathogenic budding yeasts are likely to be associated with both environmental and human niches [99]. The 13 CUG-Ser1 species isolated from humans with genome-wide evidence of selection on codon usage had a mean optimization of 0.74, 0.76, and 0.69 for GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7, respectively.

We also found that GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7 optimization was significantly higher (Wilcoxon rank sum test p-values of 0.035, 0.014, and 0.003, respectively) in species from human-associated ecological niches than insect-associated niches only, irrespective of genome-wide evidence of translational selection (88 species). For example, the major human pathogen C. albicans does not have genome-wide evidence for high levels of translational selection but has a very high GAL10 codon optimization (estAI = 0.86). While C. albicans may not have evidence of genome-wide selection on codon optimization, a previous analysis suggests that at least 17% of genes in the C. albicans genome have likely experienced selection on codon usage [59].

Other opportunistic human pathogenic species with very high GAL10 codon optimization (estAI > 0.8) include Candida dubliniensis [100], Meyerozyma caribbica [101], Candida tropicalis [102], Meyerozyma guilliermondii [103], and Clavispora lusitaniae [104]. The optimization of GAL10 in human pathogenic species is consistent with findings that GAL10 expression is up-regulated during C. albicans growth in the mammalian intestinal track [105]. Furthermore, GAL10 in C. albicans is required for cell wall integrity, resistance to oxidative stress, and other virulence-related traits, even in the absence of galactose [88]. This suggests that GAL10 may play an additional role, outside of galactose metabolism, in the CUG-Ser1 clade.

Interestingly, the highest GAL10 optimization (average estAI = 0.93) in the CUG-Ser1 clade is found in Spathaspora species. While many Spathaspora species have been isolated from insects, 4 of the 5 species studied here (Spathaspora girioi, Spathaspora hagerdaliae, Spathaspora gorwiae, and Spathaspora arborariae) have been isolated only from rotting wood [106,107]. This observation is particularly interesting given the hypothesis that some features of saprophytic fungi, such as Aspergillus fumigatus and Cryptococcus spp., enable or predispose them to colonize human hosts [108,109]. Moreover, some pathogenic budding yeasts, including C. albicans and C. tropicalis, have recently been associated with soil [99]. Taken together, these results suggest that the GALactose metabolism pathway may contribute to the capability of CUG-Ser1 species to opportunistically infect humans through metabolic shifts, cell wall changes, or preadaptation to human-like environments. Further experimentation is needed to fully understand the contributions of this pathway to fungal pathogenicity.

Saccharomycetaceae: Among Saccharomycetaceae species, we found that GAL optimization is significantly higher (p < 0.05) in those that have been isolated only from dairy-associated niches compared to species isolated only from alcohol-associated niches (19 species; Fig 3B.) Only one species isolated from either dairy or alcohol, namely the alcohol-associated Lachancea thermotolerans, did not have evidence of genome-wide translational selection on codon usage. The 4 species isolated only from dairy-associated niches (Kluyveromyces lactis, Naumovozyma dairenensis, Vanderwaltozyma polyspora, and Kazachstania turicensis) have mean codon optimization values of 0.90, 0.88, and 0.84 for GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7, respectively. The 10 species that are only from alcohol-associated niches (S2 Data) have mean codon optimization values of 0.73, 0.61, and 0.59 for GAL1, GAL10, and GAL7, respectively. We also note that an association between galactose metabolism and these environments would not be apparent from gene presence/absence data only—a commonly used genomic feature in reverse ecology studies. Of the species found in dairy, alcohol, or both environments, the percentage of species with a complete GAL pathway was 83%, 88%, and 90% for the niches, respectively. The 4 dairy-associated species lacking a complete GAL pathway (the 17%) may be utilizing the other sugars and fermentation products available in dairy. Therefore, whereas gene presence/absence analyses may be better suited to address whether organisms “can” grow on a given substrate, codon optimization analyses may be better suited to address “how well” organisms grow on a given substrate. The association between GAL codon optimization and dairy associated niches may be the result of the fact that in many dairy environments, there are large microbial communities that often consist of lactic acid bacteria that convert lactose into glucose and galactose, which can subsequently be used in the GAL pathway [110,111]. The natural presence of galactose in dairy-associated environments is the likely driver of GAL codon optimization.

Species found in both dairy- and alcohol-associated niches have a range of optimization values that generally encompasses the values observed for species from dairy- or alcohol-only niches. It is likely that this group (associated with both dairy and alcohol niches) contains species or populations that are better adapted to one niche than the other. It is not possible, however, based on current literature to disentangle these 2 categories. For example, the species Kluyveromyces marxianus has been isolated from chica beer [112], cider [113], kombucha [114], and mezcal liquor [115]. However, K. marxianus is a well-known “dairy yeast” frequently found in both natural [116,117] and industrial dairy products [118]. Codon optimization of the GAL enzymatic pathway is also very high in K. marxianus with an average estAI of 0.92. We hypothesize that the high GAL codon optimization in K. marxianus is a result of its association with dairy and with the ability of K. marxianus to metabolize lactose into glucose and galactose [44]. There are 2 species that are associated with both dairy and alcohol niches whose GAL codon optimization values are higher than the maximum value observed in alcohol-only species—Naumovozyma castellii and Kazachstania unispora. Based on this, we hypothesize that these species are well adapted to dairy-associated environments.

The species K. wickerhamii, for which we predicted growth rate on galactose-containing media from codon optimization, belongs to the Saccharomycetaceae. The observed codon optimization values of K. wickerhamii GAL genes lie below the lower (first) quantile of species found in dairy-associated niches: GAL1 below 0.892 (observed 0.887), GAL10 below 0.843 (observed 0.660), and GAL7 below 0.776 (observed 0.531). We would therefore predict that K. wickerhamii is not associated with dairy niches. Consistent with this prediction, K. wickerhamii is characterized as “confined to Drosophila species and to tree exudates that probably act as Drosophila habitats” [60].

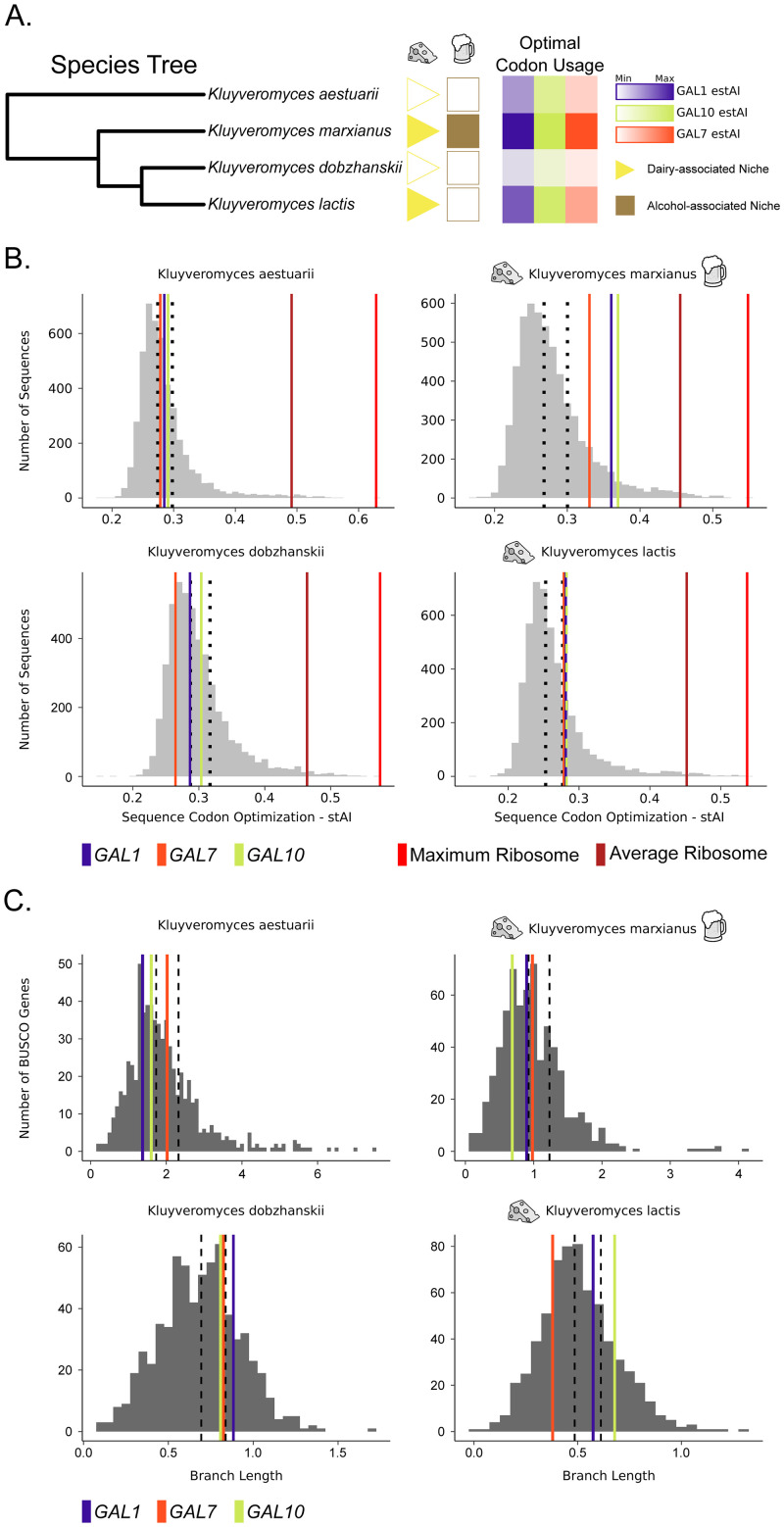

Differential GAL pathway optimization in Kluyveromyces

The genus Kluyveromyces provides an example of how codon optimization varies between closely related species that differ in their ecological niches (Fig 4). Two of the 4 species in this clade have not been isolated from either dairy or alcohol; Kluyveromyces aestuarii has been isolated from marine mud and seawater, while Kluyveromyces dobzhanskii has been isolated from flies, plants, and mushrooms [60]. Of the 4 species represented here, only K. dobzhanskii is not known to metabolize lactose into glucose and galactose [60]. While all 4 species are capable of growing on galactose, GAL gene codon optimization is much higher in the 2 species with dairy-associated ecological niches, Kluyveromyces lactis and Kluyveromyces marxianus (Fig 4A). Codon optimization for GAL genes is greater than 75% of the genome (estAI > 0.75) for K. lactis and K. marxianus. In K. marxianus, the optimization of GAL1 and GAL10 (estAI 0.93 and 0.94) is nearly that of the average ribosomal gene (estAI 0.99; Fig 4B). Ribosomal genes, which are among the most highly expressed genes in the genome, are known to be highly optimized in a broad range of species [119]. In contrast, optimization values for GAL genes in K. aestuarii and K. dobzhanskii are nearer to the mean (mean estAI values of 0.63 and 0.46, respectively; Fig 4B).

Fig 4. Closely related Kluyveromyces species exhibit differential codon optimization in the GAL pathway associated with isolation from dairy environments.

All 4 Kluyveromyces species were shown experimentally to metabolize galactose. (A) Species phylogeny of 4 closely related Kluyveromyces species. K. marxianus and K. lactis are both associated with dairy niches and have high codon optimization values in their GAL pathway genes. In contrast, K. aestuarii is associated with marine mud, and K. dobzhanskii is associated with flies. (B) The genome-wide distribution of codon optimization (stAI) values for the 4 Kluyveromyces species included in this study. The 50th and 75th percentiles are shown with black dashed lines. In the 2 species associated with dairy niches, the codon optimization for all 3 GAL genes falls in the top 25th percentile. In the 2 species not associated with dairy, the GAL genes fall below the top 25th percentile. Genes encoding ribosomal proteins are well established to rank among the most highly optimized genes within a genome. (C) The distribution of terminal synonymous (dS) branch lengths (in unrooted gene trees) calculated for the 651 BUSCO genes. All 3 GAL genes fall within the interquartile range for K. aestuarii and K. marxianus. In K. dobzhanskii, all 3 GAL genes lie above the 70th percentile with GAL1 in the upper quartile. In K. lactis, GAL7 falls below the interquartile range, while GAL10 lies above. The 50th and 75th percentiles are shown with black dashed lines. Underlying data can be found in Tables G–P S4 Data.

We hypothesized that the low GAL optimization in K. aestuarii and K. dobzhanskii was due to a relaxation in translational selection on the GAL pathway. To test this hypothesis, we estimated the rate of synonymous site evolution using PAML on the GAL genes and 651 BUSCO genes. In K. aestuarii and K. marxianus, the GAL genes all fell within the median 50% of BUSCO genes, suggesting that the synonymous sites in these species have not experienced rapid change or high levels of conservation. In the sister species K. dobzhanskii and K. lactis, there was some evidence of relaxation of selection on synonymous sites in GAL10 and GAL1 in K. dobzhanskii, leading to longer branches. In K. lactis, GAL7 also had a short branch that fell within the most slowly evolving 25% of the highly conserved BUSCO genes, which may indicate constraint on this gene’s codon usage. This finding is consistent with the strong association between GAL7 and growth rate on galactose-containing medium.

GAL optimization is correlated with optimization in other metabolic genes

In general, multiple metabolic pathways, as opposed to a single one, likely contribute to adaptation to an ecological niche [54,120]. To identify genes in other metabolic pathways that are potentially associated with galactose metabolism, we tested whether levels of codon optimization in GAL genes were significantly correlated with levels of codon optimization in other KOs. We identified 78/2,572 KOs with a significant positive or negative association with GAL optimization (PIC, multiple test corrected p-value <0.05; S3 Data). To explore the results, we focused on the top hits for each individual GAL gene and hits that occurred in more than one GAL gene (Table 1).

Table 1. KEGG Orthology (KO) annotated genes that have a codon optimization correlated with GAL1, GAL10, or GAL7.

This table contains the significant (multiple test corrected p-value <0.001***) results with the greatest absolute slope for each GAL gene and 3 additional results that are significant in both GAL7 and GAL10. Gene names for S. cerevisiae are listed where available.

| KO | KO Title | S. cerevisiae Gene | GAL1 slope | GAL10 slope | GAL7 slope | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K00916 | CTK1; CTD kinase subunit alpha | CTK1 | −0.28 | *** | −0.14 | −0.17 | ||

| K08139 | HXT; MFS transporter, SP family, sugar:H+ symporter | RGT2, SNF3, GAL2, HXT1–11, HXT13–17 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 1.09 | *** | ||

| K02564 | nagB, GNPDA; glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase | 0.23 | 0.65 | *** | 0.33 | |||

| K05292 | PIGT; GPI-anchor transamidase subunit T | GPI16 | 0.17 | 0.52 | *** | 0.66 | *** | |

| K14012 | NSFL1C, UBX1, SHP1; UBX domain-containing protein 1 | SHP1 | 0.20 | 0.49 | *** | 0.57 | *** | |

| K17605 | PPP2R4, PTPA; serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A activator | RRD1, RRD2 | −0.30 | −0.47 | *** | −0.68 | *** |

Within the top correlated KO annotations, we found several annotations related to glucose and galactose metabolic sensing and regulation. It is important to note, however, that KEGG annotations are unable to differentiate between orthologs, ohnologs, or paralogs. Codon optimization of genes annotated with the KO K08139 were significantly and positively correlated with optimization in GAL7. Genes with this annotation have been implicated in metabolic sensing. This KO includes SNF3 and RTG2, which have been shown to detect glucose in S. cerevisiae [121] but are associated with galactose sensing in C. albicans [122]. GAL2, the galactose transporter, is also associated with this annotation. To discern which homologs may have correlated expression with the GALactose metabolism genes, further analysis and a more complete taxon sampling would be required. The annotation K05292 is associated with the S. cerevisiae gene GPI16, whose codon optimization was correlated with both GAL7 and GAL10; GPI16 encodes a subunit of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol transamidase complex. This complex is involved in the addition of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors to proteins, which allow these proteins to be anchored to the plasma membrane [123]. Not only can these anchors contain galactose, but they may be involved in the recognition of opportunistic pathogens by the host immune system [123]. This correlation further supports the link between the galactose metabolism pathway and isolation from human associated niches in the CUG-Ser1 clade. Codon optimization in the gene SHP1 is correlated with optimization of both GAL7 and GAL10. Shp1 has been shown to be involved in glucose sensing in the cAMP-PKA pathway, which helps to regulate storage of carbohydrate levels [124]. Other notable genes whose optimization correlates with GALactose genes are YCK1/YCK2, which are involved in glucose sensing [125]; ICL1, which encodes a member of the glyoxylate shunt that may be differentially used in alternative carbon metabolism [126], and THI6/PHO8, which is involved in the production of thiamine pyrophosphate, a cofactor used by several carbon metabolism enzymes. These results suggest that correlated codon optimization may be a useful way to computationally associate the expression of pathways. Follow-up analyses within specific subclades and experimental work are needed to determine whether these associations are mechanistically relevant.

Conclusions

Here, we use reverse ecology to associate genotype (codon optimization) with phenotype (growth rate on galactose) and ecology (isolation environment) across an entire evolutionary lineage (budding yeasts). The conceptual evolutionary model for this association (Fig 5) is that selection for increased rates of galactose metabolism in galactose-rich environments will result in selection for optimization of codon usage in the GAL genes. This selection is likely to continue until codon usage is no longer a barrier to maximum flux allowed through this pathway for a given metabolic load. Therefore, codon optimization not only reflects a mechanistic measure of expression but an evolutionary signal for selection on increased expression.

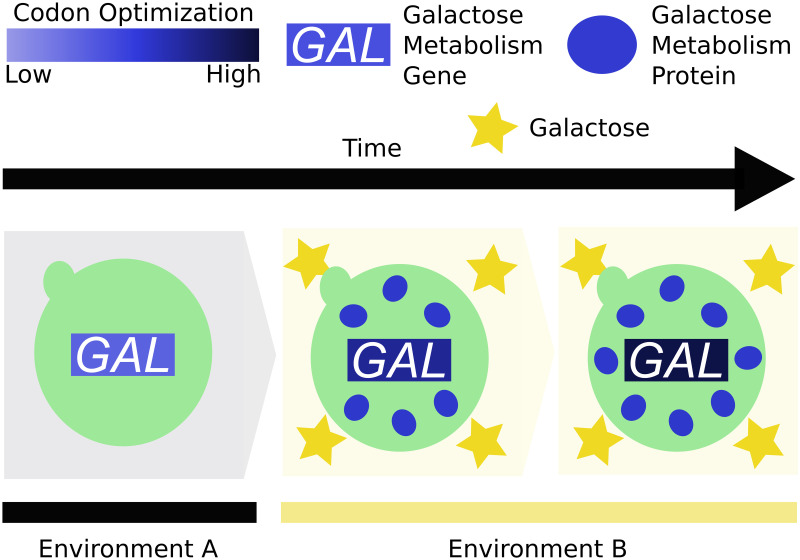

Fig 5. A model for ecological codon adaptation in the GALactose metabolism pathway.

The ancestral species in environment A maintains the GALactose metabolism pathway at an intermediate codon optimization. Upon introduction to environment B, which contains abundant galactose, there is increased demand for the GALactose metabolism enzymes to take advantage of this energy source. In this new environment, substitutions that increase codon optimization of the GAL genes will be selectively advantageous. Codon optimization will continue to increase under translational selection until it is no longer a barrier to expression or optimal flux through the pathway has been achieved.

By studying a well-known metabolic pathway in a diverse microbial subphylum, we provide a proof of concept for the utility of codon optimization as a genomic feature for reverse ecology. Our discovery of optimization in the GAL pathway in dairy-associated Saccharomycetaceae and human-associated CUG-Ser1 yeasts is consistent with the known functional roles of the enzymes in the pathway. The complete GAL pathway metabolizes galactose, a component of dairy environments, into usable energy [127]. The GAL10 gene affects phenotypes associated with human colonization in CUG-Ser1 yeasts [88]. Similarly, in the Kluyveromyces species found on dairy-associated niches that are able to metabolize lactose into glucose and galactose, there is high optimization in this pathway compared to closely related species not associated with dairy. Interestingly, examination of codon optimization in the gene sets of the 4 Kluyveromyces species studied here would have identified at least K. marxianus as a potential dairy-associated yeast, even in the absence of any knowledge about its isolation environments. Thus, genome-wide examination of codon optimization in fungal, and more generally microbial, species can generate specific hypotheses about metabolic ecology that can be experimentally tested. Our method can also be applied directly to single-cell genomes generated from microbial dark matter known only from DNA [128]. Finally, using an unbiased approach, we identified a strong correlation between optimization in the GAL pathway and other pathways involved in metabolic processing. This novel finding suggests that codon optimization may also be useful for identifying coregulated or correlated pathways in microbial, including fungal, species.

By focusing on a well-characterized pathway, we are able to associate a specific genotype with both a phenotype and ecology. While previous codon-based reverse ecology studies have identified functional categories of genes associated with environments [39–43], we illustrate that this approach can also be useful at the level of individual genes and pathways. It is important to note that this approach may not work for all genes—especially those that have universally high codon usage, such as ribosomal genes and the mannose metabolism gene PMI40. More broadly, our results suggest that codon optimization can be a useful tool for predicting candidate genes and pathways involved in ecological adaptation, which can be subsequently tested experimentally.

Supporting information

Various features of galactose metabolism plotted on a phylogeny of the budding yeast subphylum Saccharomycotina; the 12 major clades of the subphylum are color coded. The presence and codon optimization (measured by estAI) of the 3 GAL genes are represented in the inner 3 rings. The GAL clusters in the Dipodascaceae/Trichomonascaceae, Pichiaceae, and Phaffomycetaceae were recently identified as likely originating from horizontal gene transfer events from the CUG-Ser1 clade. High codon optimization (darker colors) in the GAL pathway is not restricted to any one major clade. Complete and clustered occurrences of the GAL pathway are represented by filled-in blue squares and circles, respectively. Ecological associations were uncovered using a literature search (S2 Data).

(PDF)

Growth rate is calculated based on the maximum slope of the curve in the R package grofit. The slopes calculated in this species for galactose are 0.0495, 0.0747, and 0.0862 in the replicates 1 to 3 for an average growth rate of 0.070. The slopes calculated in this species for glucose are 0.0712, 0.0762, and 0.0682 in the replicates 1 to 3 for an average growth rate of 0.072. Therefore, the glucose normalized rate of growth on galactose is 0.97.

(PDF)

(A) The residual versus fitted analysis shows 2 outlier strains: Metschnikowia matae var. matae and Metschnikowia matae var. maris. (B) Residual and Q-Q normalized plots after removal of Metschnikowia matae var. matae. No clear outliers remained after removal of this species.

(PDF)

Blue bars are the codon optimization values for species that have not been isolated from the particular ecology. Yellow bars are the codon optimization values for species that have been isolated from that ecology. Ecological information was tested in 50 isolation environments from data collated from The Yeasts: A Taxonomic Study as recorded by Opulente and colleagues [54].

(PDF)

(A) Wilcoxon rank sum test of GAL codon optimization versus binary data for growth on galactose. A total of 170 species were included in this analysis. (B) Wilcoxon rank sum test of GAL codon optimization in species with complete or incomplete GAL pathways. A total of 185 species were included in this analysis.

(PDF)

(A) The phylogenetically corrected correlation between GAL codon optimization and quantitative growth on galactose-containing medium is significant in all genes when only species from the family Saccharomycetaceae are considered. A total of 29 species were included in this analysis. (B) The phylogenetically corrected correlation between GAL codon optimization and quantitative growth on galactose-containing medium is only significant in GAL7 when only the CUG-Ser1 major clade species are considered. This analysis includes 47 species.

(PDF)

This analysis suggests that codon optimization in PGM1/PGM2 does not contribute to growth on galactose-containing medium.

(PDF)

(PDF)

This result supports the conclusion that the association between GAL optimization and growth rate on galactose is specific to that pathway.

(PDF)

This result is likely due to the very high codon optimization observed in PMI40.

(PDF)

The circular points represent the predicted growth rates based on the observed codon optimization values (lines). The triangles represent the actual growth rate measured in the laboratory.

(PDF)

To better understand the performance of our growth rate predictions based on codon usage, we tested how well GALactose genes with randomly assigned codons could predict growth rate. The purple lines represent the empirically measured growth rate for each species. The orange line is the growth rate predicted by the actual codon usage for each gene based on the PGLS analysis. For each GAL gene associated with K. wickerhamii (panel A) and W. occidentalis (panel B), we generated 1,000 DNA sequences with random codon usage (while keeping the protein sequence identical). For each random sample, we then predicted growth rate based on our regression analysis. In both cases, both the predicted and the actual growth rates fall outside of the 95th percentile. Additionally, for all but one observation (GAL7 in K. wickerhamii), the predictions and actual growth rate fall outside the 99th percentile. These results show that our predictions are highly informative.

(PDF)

This includes major clade, file name, GALactose information, and codon selection values (S-value).

(XLSX)

This includes presence/absence data in addition to the corresponding references.

(XLSX)

For each KO, the correlation with each GAL gene is reported along with the multiple test corrected significance. Corrected p-values corresponding to 0.05, 0.005, and 0.001 are noted as *, **, and ***, respectively.

(XLSX)

(A) Data for Fig 1, including species and GALactose gene codon optimization. (B) Data for Fig 2A including GAL1 codon optimization and growth rate on galactose relative to glucose per species. (C) Data for Fig 2B including GAL10 codon optimization and growth rate on galactose relative to glucose per species. (D) Data for Fig 2C including GAL7 codon optimization and growth rate on galactose relative to glucose per species. (E) Data for Fig 3A including each species, their GAL codon optimization and their ecological niche. This also includes the minimum, Q1, median, Q3, and maximum codon optimization values. (F) Data for Fig 3B including each species, their GAL codon optimization and their ecological niche. This also includes the minimum, Q1, median, Q3, and maximum codon optimization values. (G) Data for Fig 4A including the Kluyveromyces species, their codon optimization values and ecological niches. (H) Data for Fig 4b including K. aesturaii codon optimization values for all genes. (I) Data for Fig 4B including K. aesturaii codon optimization values for ribosomal genes. (J) Data for Fig 4B including K. marxianus codon optimization values for all genes. (K) Data for Fig 4B including K. marxianus codon optimization values for ribosomal genes. (L) Data for Fig 4B including K. dobzhanskii codon optimization values for all genes. (M) Data for Fig 4B including K. dobzhanskii codon optimization values for ribosomal genes. (N) Data for Fig 4B including K. lactis codon optimization values for all genes. (O) Data for Fig 4B including K. lactis codon optimization values for ribosomal genes. (P) Data for Fig 4C including the branch lengths modeled for each BUSCO gene analyzed.

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Rokas and Hittinger labs for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- GAL

galactose

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- KO

KEGG Orthology

- PGLS

phylogenetic generalized least squares

- PIC

phylogenetically independent contrasts

- stAI

species-specific tRNA adaptation index

- YPD

yeast extract peptone dextrose

Data Availability

All analyses were done on publicly available and published genome assemblies and annotations (where available). The codon optimization values were obtained from the figshare repository from LaBella et al. 2019 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.4498292). Additional sequence analyses generated in this project, including the reference and annotated gene sequences, are stored in the figshare repository associated with this manuscript (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5067962). Data associated with each figure can be found in Supplementary Information file 4. All other information and data generated are available in the supplementary files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. DEB-1442113 (to A.R.) and DEB-1442148 (to C.T.H.), in part by the DOE Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (DOE BER Office of Science DE-SC0018409), USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Hatch Project 1020204 to C.T.H.), and a Guggenheim fellowship (to A.R). C.T.H. is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences and a H. I. Romnes Faculty Fellow, respectively supported by the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Savolainen O, Lascoux M, Merilä J. Ecological genomics of local adaptation. Nat Rev Genet. 2013. 10.1038/nrg3522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoekstra HE, Krenz JG, Nachman MW. Local adaptation in the rock pocket mouse (Chaetodipus intermedius): Natural selection and phylogenetic history of populations. Heredity (Edinb). 2005. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett RDH, Rogers SM, Schluter D. Natural selection on a major armor gene in threespine stickleback. Science. 2008;322. 10.1126/science.1159978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abzhanov A, Protas M, Grant BR, Grant PR, Tabin CJ. Bmp4 and morphological variation of beaks in Darwin’s finches. Science. 2004. 10.1126/science.1098095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abzhanov A, Kuo WP, Hartmann C, Grant BR, Grant PR, Tabin CJ. The calmodulin pathway and evolution of elongated beak morphology in Darwin’s finches. Nature. 2006. 10.1038/nature04843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant PR. Ecology and evolution of Darwin’s finches. Ecology and Evolution of Darwin’s Finches. Princeton University Press; 1999. 10.2307/4785 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daborn PJ, Yen JL, Bogwitz MR, Le Goff G, Feil E, Jeffers S, et al. A single P450 allele associated with insecticide resistance in Drosophila. Science. 2002. 10.1126/science.1074170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steiner CC, Weber JN, Hoekstra HE. Adaptive variation in beach mice produced by two interacting pigmentation genes. PLoS Biol. 2007. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou J. Predictive microbial ecology. J Microbial Biotechnol. 2009. 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00090_21.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy R, Borenstein E. Reverse ecology: From systems to environments and back. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012. 10.1007/978-1-4614-3567-9_15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li YF, Costello JC, Holloway AK, Hahn MW. “Reverse ecology” and the power of population genomics. Evolution. 2008. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00486.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Retchless AC, Lawrence JG. Ecological adaptation in bacteria: Speciation driven by codon selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2012. 10.1093/molbev/mss171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy R, Borenstein E. Metagenomic systems biology and metabolic modeling of the human microbiome: From species composition to community assembly rules. Gut Microbes. 2014. 10.4161/gmic.28261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauer DB, Wang DN. Predicting the optimal growth temperatures of prokaryotes using only genome derived features. Bioinformatics. 2019. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellison CE, Hall C, Kowbel D, Welch J, Brem RB, Glass NL, et al. Population genomics and local adaptation in wild isolates of a model microbial eukaryote. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011. 10.1073/pnas.1014971108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borenstein E, Kupiec M, Feldman MW, Ruppin E. Large-scale reconstruction and phylogenetic analysis of metabolic environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008. 10.1073/pnas.0806162105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao Y, Wang Y, Zheng X, Li F, Bo X. RevEcoR: An R package for the reverse ecology analysis of microbiomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2016. 10.1186/s12859-016-1088-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr R, Borenstein E. NetSeed: A network-based reverse-ecology tool for calculating the metabolic interface of an organism with its environment. Bioinformatics. 2012. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikemura T. Correlation between the abundance of Escherichia coli transfer RNAs and the occurrence of the respective codons in its protein genes. J Mol Biol. 1981. 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90363-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas LK, Dix DB, Thompson RC. Codon choice and gene expression: Synonymous codons differ in their ability to direct aminoacylated-transfer RNA binding to ribosomes in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988. 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gouy M, Gautier C. Codon usage in bacteria: Correlation with gene expressivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982. 10.1093/nar/10.22.7055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.López-Maury L, Marguerat S, Bähler J. Tuning gene expression to changing environments: From rapid responses to evolutionary adaptation. Nat Rev Genet. 2008. 10.1038/nrg2398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldspink G. Adaptation of fish to different environmental temperature by qualitative and quantitative changes in gene expression. J Therm Biol. 1995. 10.1016/0306-4565(94)00045-K [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Q, Zhu C, Fan Y, Song Z, Xing S, Liu W, et al. Population transcriptomics uncovers the regulation of gene expression variation in adaptation to changing environment. Sci Rep. 2016. 10.1038/srep25536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fay JC, McCullough HL, Sniegowski PD, Eisen MB. Population genetic variation in gene expression is associated with phenotypic variation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genome Biol. 2004. 10.1186/gb-2004-5-4-r26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rocha EPC. Codon usage bias from tRNA’s point of view: Redundancy, specialization, and efficient decoding for translation optimization. Genome Res. 2004. 10.1101/gr.2896904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chevance FFV, Le Guyon S, Hughes KT. The Effects of Codon Context on In Vivo Translation Speed. PLoS Genet. 2014. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoletzki N, Eyre-Walker A. Synonymous codon usage in Escherichia coli: Selection for translational accuracy. Mol Biol Evol. 2007. 10.1093/molbev/msl166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuller T, Waldman YY, Kupiec M, Ruppin E. Translation efficiency is determined by both codon bias and folding energy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010. 10.1073/pnas.0909910107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brule CE, Grayhack EJ. Synonymous Codons: Choose Wisely for Expression. Trends Genet. 2017. 10.1016/j.tig.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Presnyak V, Alhusaini N, Chen YH, Martin S, Morris N, Kline N, et al. Codon optimality is a major determinant of mRNA stability. Cell. 2015. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radhakrishnan A, Chen YH, Martin S, Alhusaini N, Green R, Coller J. The DEAD-Box Protein Dhh1p Couples mRNA Decay and Translation by Monitoring Codon Optimality. Cell. 2016. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duret L, Mouchiroud D. Expression pattern and, surprisingly, gene length shape codon usage in Caenorhabditis, Drosophila, and Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999. 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hiraoka Y, Kawamata K, Haraguchi T, Chikashige Y. Codon usage bias is correlated with gene expression levels in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Cells. 2009. 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahoo S, Das SS, Rakshit R. Codon usage pattern and predicted gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene X. 2019;2:100012. 10.1016/j.gene.2019.100012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Payne BL, Alvarez-Ponce D. Codon usage differences among genes expressed in different tissues of drosophila melanogaster. Genome Biol Evol. 2019. 10.1093/gbe/evz051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das S, Chottopadhyay B, Sahoo S. Comparative analysis of predicted gene expression among crenarchaeal genomes. Genomics Inform. 2017;15:38. 10.5808/GI.2017.15.1.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roymondal U, Das S, Sahoo S. Predicting gene expression level from relative codon usage bias: An application to escherichia coli genome. DNA Res. 2009. 10.1093/dnares/dsn029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]