Abstract

Epigenomics regulates gene expression and is as important as genomics in precision personal health, as it is heavily influenced by environment and lifestyle. We profiled whole-genome DNA methylation and the corresponding transcriptome of peripheral blood mononuclear cells collected from a human volunteer over a period of 36 months, generating 28 methylome and 57 transcriptome datasets. We found that DNA methylomic changes are associated with infrequent glucose level alteration, whereas the transcriptome underwent dynamic changes during events such as viral infections. Most DNA meta-methylome changes occurred 80–90 days before clinically detectable glucose elevation. Analysis of the deep personal methylome dataset revealed an unprecedented number of allelic differentially methylated regions that remain stable longitudinally and are preferentially associated with allele-specific gene regulation. Our results revealed that changes in different types of ‘omics’ data associate with different physiological aspects of this individual: DNA methylation with chronic conditions and transcriptome with acute events.

Personalized precision medicine has become an emerging theme for biomedical research as well as a model for future medical care1–6. Due to recent development of high-throughput technologies, physiological states can now be systematically profiled using detailed molecular approaches, which enable the identification of personalized molecular signatures associated with physiological states as well as disease onset and progression, thus enabling treatments tailored to each patient’s own medical condition and needs.

DNA methylation is a key mechanism in gene expression regulation and is influenced by environmental factors and age7–9. Methylation of cytosines in CpG islands alters the expression of associated genes, and methylated cytosines residing in a CHG or CHH context also occur at a lower frequency. DNA methylation is often asymmetric—for example, allelic differentially methylated regions (aDMRs) are associated with the preferential silencing of one of the two parental gene copies10–12.

The spatial and temporal regulation of DNA methylation is important in understanding biology and disease13. However, to date only a limited number of spatial and temporal studies have been performed. Notably, the Roadmap Epigenome Project reported significant tissue-specific epigenomic profiles, including DNA methylome profiles, in various human tissues14. Methylomic changes were reported in muscle through exercise in both animal models and human studies using reduced-representation bisulfite sequencing or microarrays8,9.

However, detailed dynamics and the relationship between the DNA methylome and transcriptome, as well as their association with health conditions, are poorly understood. Long-term dynamics of multi-omics changes are rarely documented, and how personal methylomic profiles are altered through different physiological states and health/disease states is unknown.

To address these issues, we monitored integrative personal omics profiles in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and other blood components of a volunteer over multiple years, and published the first 400 days in 20122. To further understand the dynamics of molecular changes that occurred over time in this individual, we now report a three-year longitudinal profile of a personal DNA meta-methylome in the PBMC samples of the same volunteer using whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS; that is, MethylC sequencing (MethylC-seq))15. We identified personalized longitudinal and allele-specific methylomic signatures, and analyzed the corresponding transcriptome (through RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)) during this period. We found that for this individual transcriptomic profiles changed frequently with acute events, whereas dynamic alterations of the DNA methylome associated with glucose elevation, a chronic condition. We also investigated aDMRs in the combined dataset and demonstrated their association with regulatory regions and gene expression. Overall, we expect this study to serve as a model for characterizing longitudinal personal epigenomes and as a valuable open resource to the scientific community.

Results

Personal methylome and transcriptome profiles over 36 months.

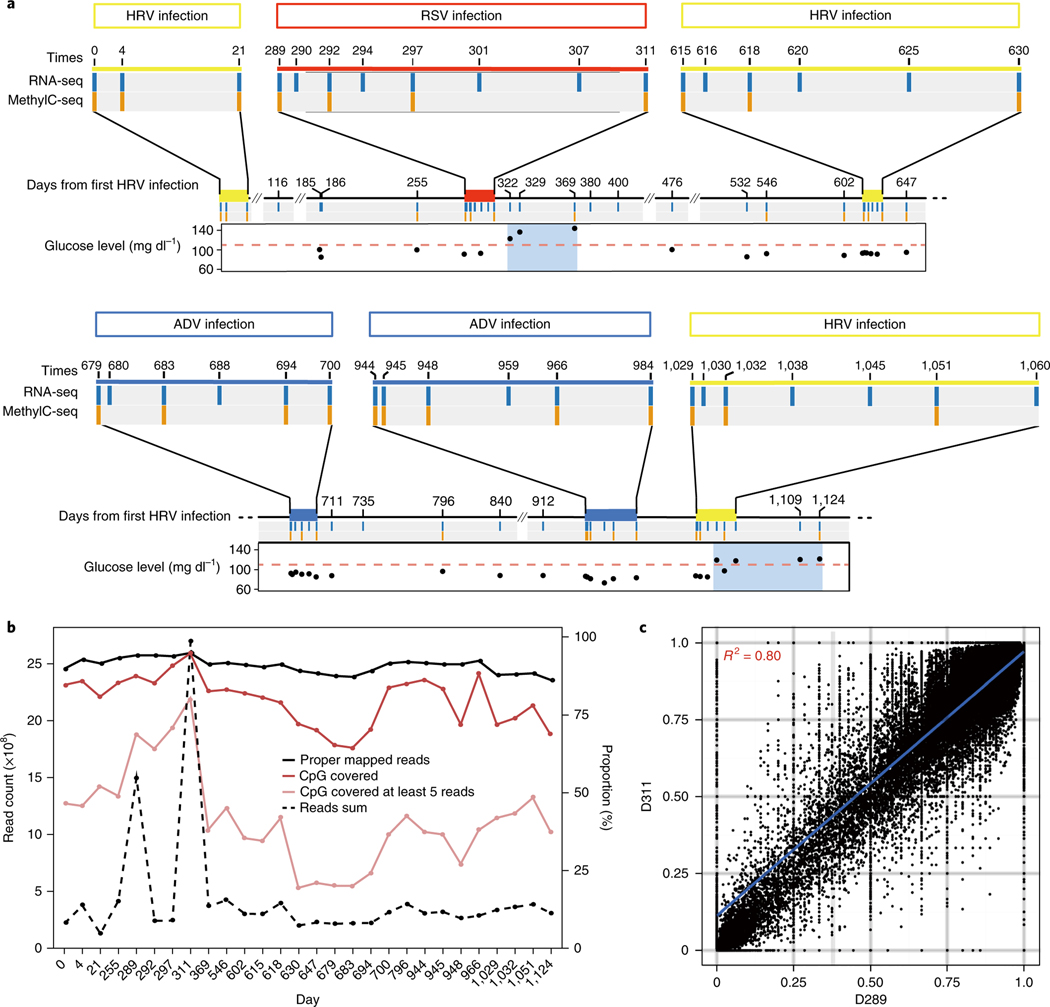

We collected peripheral blood samples donated by a 54-year-old male participant at 57 time points spanning 36 months, and extracted both DNA and RNA from PBMCs prepared at each time point (see Methods). During this period, the participant experienced six viral infections, including three human rhinovirus (HRV), two adenovirus (ADV) and one respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections, as well as two elevated periods of fasting glucose and glycated hemoglobin A1c that reached diabetic levels (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). Each viral infection and recovery occurred over days, whereas the elevated glucose periods occurred over months. A detailed record of this participant’s health parameters is included in the Supplementary Information (see Supplementary Table 1). We performed RNA-seq at all 57 time points and MethylCseq at 28 selected time points (see Methods). For methylome profiling, we included randomly selected healthy time points between infections, as well as time points at the beginning, middle and end of each acute viral infection; we also profiled samples from the two periods of elevated glucose levels, one of which partially overlapped with a viral infection (RSV) period (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1 |. Overview of methylome and transcriptome data during time series.

a, Summary of time course study. The subject was monitored for 1,124 d, during which there were 6 infections (yellow bar, HRV infection; red bar, RSV infection; blue bar, ADV infection). Fifty-seven RNA-seq (blue column, n = 57 independent samples) and 28 MethylC-seq (orange column, n = 28 independent samples) samples were generated. Point plot shows the changes in glucose level; the pink dashed line represents the upper limit of the healthy glucose level. Glycated hemoglobin A1c levels generally followed the same trend as the glucose levels2 (not shown). b, Statistics for MethylC-seq data. The left y axis is for the dashed line. The right y axis is for solid lines. c, Scatter plot shows high correlation of methylation levels between day 289 (D289) and D311 samples (n = 2 independent samples, Spearman correlation).

Each MethylC-seq library was sequenced in at least 4 Illumina HiSeq 2000/2500 lanes, with 2 of the libraries sequenced in 8 HiSeq lanes for more detailed characterization, achieving at least 30 × sequencing depth for each sample. Each RNA-seq library was sequenced in at least one HiSeq 2000/2500 lane. Approximately 40% of the CpG sites in the genome were covered by at least 5 unique reads (76% for the in-depth samples), which were used for methylation analysis (Fig. 1b). Although lower than some studies16,17, this coverage is more than sufficient for calling significant differentially methylated regions (DMRs) using sliding windows (see Methods). In total, 15–70% of the tested CpG sites were methylated (binomial test, q-value < 0.05; see Methods). In accordance with previous findings, methylated cytosines were enriched in CpG sites (q-value < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

Since all of the data were collected from PBMCs of the same individual, we expected a high correlation between each possible sample pair. Indeed, the DNA methylation patterns were highly correlated between all samples, suggesting only mild overall changes of PBMC DNA methylation over the time course (Fig. 1c). Although the average absolute differences of all methylated sites between each two time points were small (Supplementary Fig. 1b), 82.1% of methylated loci had more than 10% methylation-level changes between the highest and lowest levels over time. These results indicated that the DNA methylation profiles were generally stable and that our data were of high quality, since low-quality data would be expected to show considerable variability. Interestingly, we observed higher similarity between methylomic profiles in samples taken near or at time points with elevated glucose levels compared to other samples (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

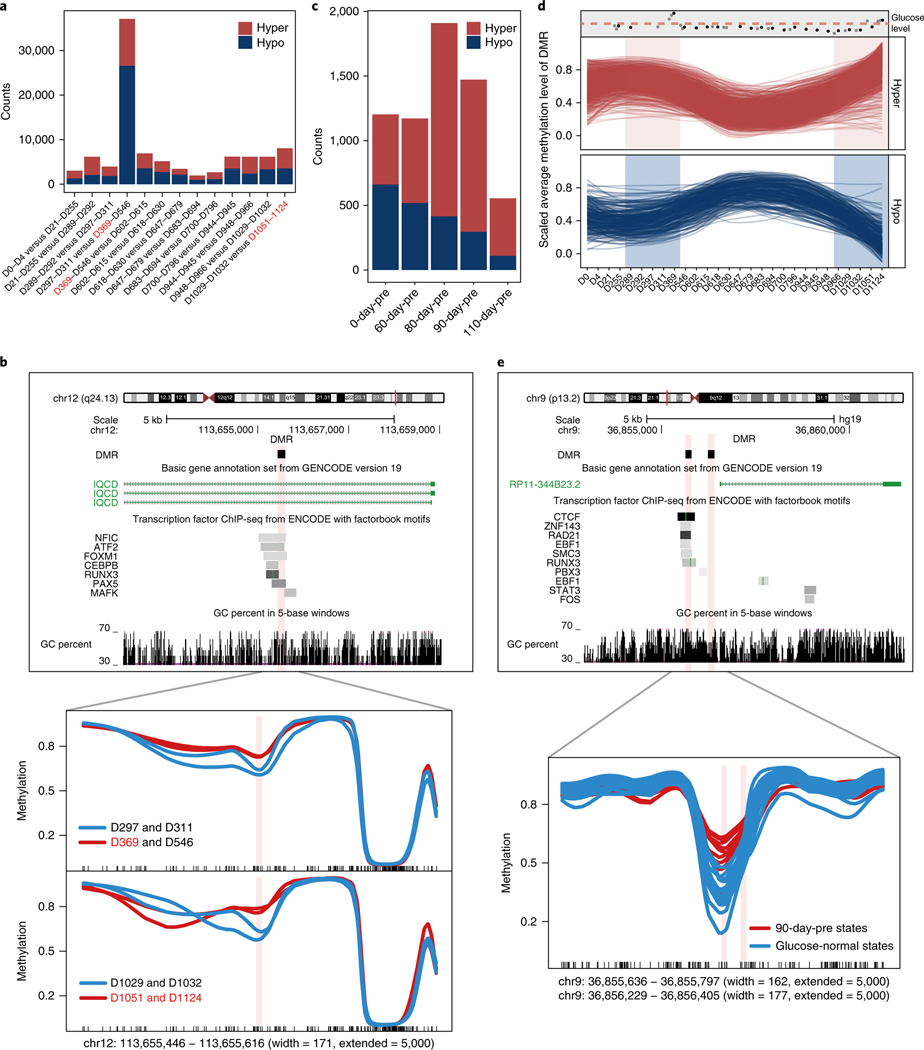

To study the dynamic patterns of whole-genome methylation profiles, we identified DMRs between adjacent time points using the BSmooth algorithm18 (see Methods and Supplementary Table 2). As expected, DMRs were mostly enriched at the flanking regions of the transcription start sites (TSSs) and enhancer regions (Supplementary Fig. 2a). The highest number of DMRs was identified between the first glucose-elevated period and the time points immediately before it (Fig. 2a). Although the number of DMRs identified between the second glucose-elevated period and time points immediately before it was much lower, it still ranked second highest in the entire time course. We identified 476 DMRs that were shared between the 2 glucose-elevated events (Supplementary Table 2). One example was shown in Fig. 2b, where it was hypermethylated at glucose-elevated time points compared with their respective previous time points. Sliding window analysis along the entire time course suggested that the dynamics of the global methylome associated with longitudinal glucose level changes.

Fig. 2 |. The dynamic pattern of the whole-genome methylome.

a, Bar plot shows the counts of DMRs between adjacent time points. The glucose-elevated time points are marked in red. b, Genome browser view of an example DMR (upper panel) shared between two glucose-elevated events. The methylation levels in the DMR were significantly higher at glucose-elevated time points compared with previous time points (lower panel). The glucose-elevated time points are marked in red. ChIP-seq, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing; IQCD, IQ motif containing D. c, Bar plot shows the counts of DMRs between extended glucose-elevated and glucose-normal states. d, Time-course dynamics of methylation levels of DMRs shared by 80-day-pre states and 90-day-pre states. 90-day-pre states are shaded in red or blue. The methylation levels were scaled between 0 and 1. The changes in glucose levels during all measured time points are indicated at the top of the panel (gray points, glucose levels of time points without MethylC-seq data; black points, glucose levels of time points with MethylC-seq data; the pink dashed line represents the upper limit of the healthy glucose level). e, Genome browser view of two DMRs (upper panel) shared between 80-pre-day states and 90-pre-day states. The methylation levels in the DMRs were significantly higher at 90-daypre states compared with glucose-normal states (lower panel).

We next compared the methylomic patterns between glucose-elevated and glucose-normal time points. Since it is possible that methylomic changes may not happen at the exact times when glucose elevation occurred, but may happen before symptom manifestation, we extended the ‘glucose level elevated’ states by including time points that were 60, 80, 90 and 110 days before the periods of actual glucose elevation. We defined these extended states as 60-daypre, 80-day-pre, 90-day-pre and 110-day-pre, respectively. We then identified DMRs using the BSmooth algorithm18 between each of these extended states and the normal time points (Supplementary Table 3). Interestingly, the highest number of DMRs were identified at the 80-day-pre and 90-day-pre states (Fig. 2c), suggesting more active global methylomic changes approximately 80 days before the actual glucose level changes. In total, we identified 1,302 DMRs that were shared between 80-day-pre and 90-day-pre states (Supplementary Table 3 and Fig. 2d). Two of the DMRs are shown in Fig. 2e. The majority of the DMRs were located 50–500 kb from TSSs of genes (Supplementary Fig. 2b). We found enrichment of terms such as ‘Type II diabetes mellitus’ for these DMRs using the GREAT algorithm19 (Supplementary Fig. 2c).

Longitudinal methylome and transcriptome changes associated with chronic glucose alterations and viral infections, respectively.

To understand how longitudinal molecular profiles associate with health-related biological functions, we next focused on methylation patterns at gene promoter regions. We first applied a sliding window approach to investigate short-term methylomic and transcriptomic changes (see Methods). For the methylomic profiles, we identified 1,001 differentially methylated promoters (within 1 kb of annotated TSSs) between each two adjacent time points (chi-squared test, P value < 0.05; fold change >2; see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Gene set functional analysis on gene ontology terms and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways showed that genes whose promoter regions changed significantly over time were highly enriched in ‘glucose and diabetes’-related pathways (Supplementary Figs. 3b, c).

For the transcriptomic profiles, we used a sliding window covering three adjacent time points and compared gene expression levels between these grouped time points (upper heatmap, Supplementary Fig. 4). We observed more frequent short-term fluctuations in transcriptomic profiles as compared with the methylomic changes. Unlike the observations in the methylomic results, a higher percentage of genes in ‘immunologic processes’-related pathways demonstrated significant transcriptomic changes (lower panel, Supplementary Fig. 4). We noticed that some transcriptomic changes were also associated with ‘glucose and diabetes’-related functions but these were less frequent than ‘immunologic processes’-related terms. These results suggest that the longitudinal methylomic profiles are associated with glucose elevation, a chronic condition, whereas the longitudinal transcriptomic profiles reflect a variety of physiological conditions—in particular, acute conditions such as viral infections in our case.

We also examined possible longitudinal correlations between differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and the methylation levels in their promoter regions, and found that the overall correlation between them was weak (R2 < 0.2 in most cases; Supplementary Fig. 1d). This indicated that the changes in gene expression longitudinally in this individual might not be solely, or mainly, determined by DNA methylation, but probably also involve other factors (for example, transcription factors or post-transcriptional regulation).

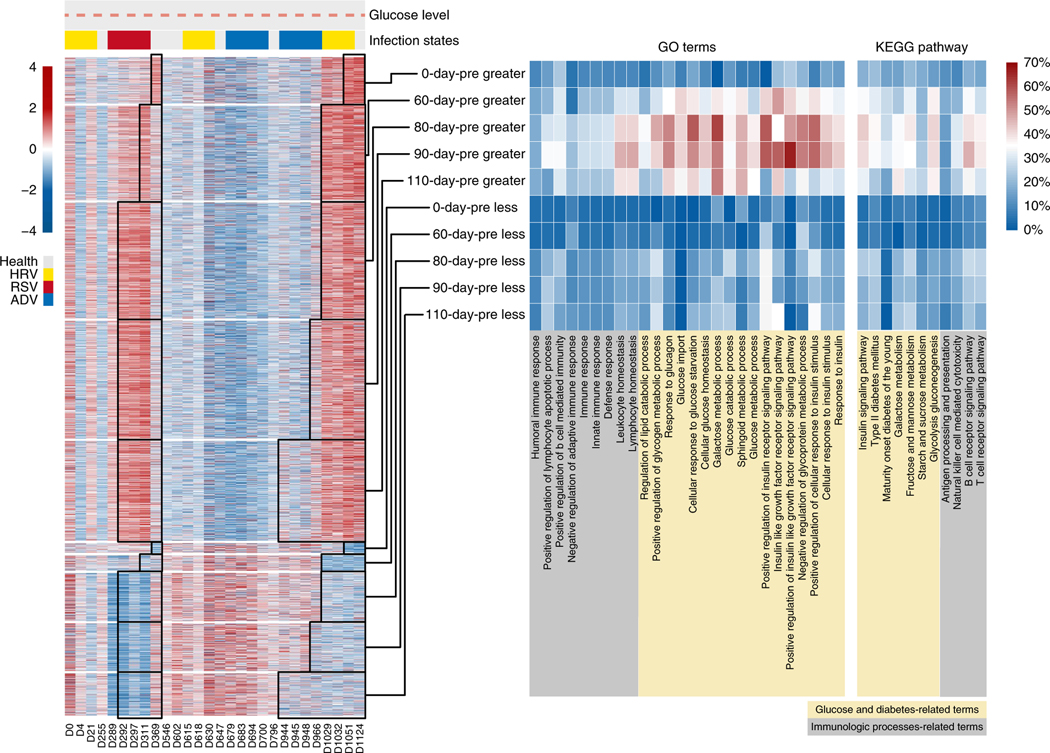

Since the significant methylomic and transcriptomic changes occurred near clinically relevant periods, we next explored associations between the molecular profiles and the recorded physiological states (the two periods of glucose level elevation and the six viral infections). First, we identified genes whose associated promoters were differentially methylated between ‘glucose level elevated’ periods and ‘glucose level normal’ periods (see Methods). Surprisingly, gene set analysis of these genes did not show significant functional terms or pathways (Fig. 3, 0-day-pre). We hypothesized that the reason might be due to a ‘phase-delayed alignment’ between longitudinal methylome changes and physiological states. In other words, since glucose level elevation is a chronic condition, the associated methylomic changes might occur before manifestation of the symptoms, similar to what we found in the global analysis described above. To test this hypothesis, we then identified differentially methylated genes for 60-day-pre, 80-day-pre, 90-day-pre and 110-day-pre states, respectively. Interestingly, we observed that ‘glucose and diabetes’-related terms and pathways contained a higher percentage of the differentially methylated genes in these extended states than that of the exact period when glucose elevation occurred. More specifically, the higher percentage of differentially methylated genes in these terms started at the 110-day-pre state, peaked at the 90-day-pre and 80-day-pre states, and was reduced at the 60-day-pre state (Fig. 3, right panel, and Supplementary Fig. 5a). These results indicate that methylomic changes that were associated with the ‘glucose-elevated’ states for this individual occurred at 80–90 days before the manifestation of elevated glucose, consistent with our DMR findings. In contrast, we did not observe the same phase shifts in our transcriptomic changes (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Fig. 3 |. Methylomic changes were associated with glucose alterations.

Left panel: scaled methylation levels of differentially methylated promoters between glucose-elevated and glucose-normal states (crimson, highest methylation level; marine, lowest methylation level); the changes in glucose levels and infection states during all measured time points are indicated at the top of the heatmap (gray points, glucose levels of time points without MethylCseq data; black points, glucose levels of time points with MethylC-seq data; the pink dashed line represents the upper limit of the healthy glucose level; yellow bar, HRV infection; red bar, RSV infection; blue bar, ADV infection). No clustering was performed. Middle panel: percentages of glucose-related differentially methylated genes in glucose- and immune-related gene ontology (GO) terms. Right panel: percentages of glucose-related differentially methylated genes in glucose- and immune-related KEGG pathways.

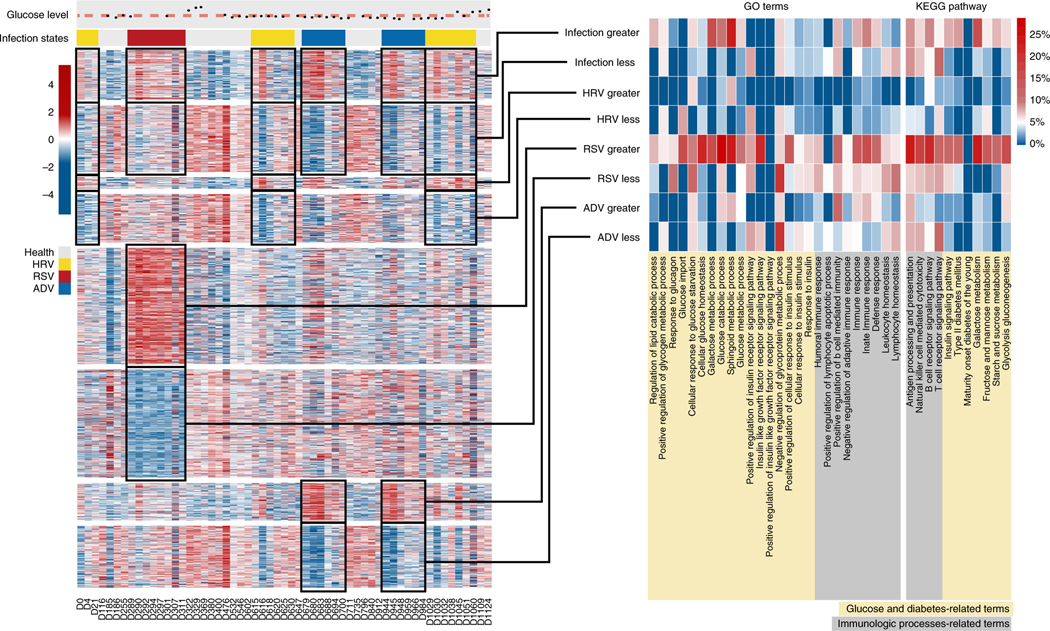

We next conducted similar analyses, focusing on the ‘viral infection’ states, acute conditions compared with ‘glucose elevation’ states. As expected, we did not find a higher percentage of the differentially methylated genes in either ‘immunologic processes’-related or ‘glucose and diabetes’-related terms/pathways, although we did notice a slightly higher fraction of ‘glucose and diabetes’-related terms during RSV infection. This is probably due to the overlap between the RSV infection and the first glucose-elevated period (Supplementary Fig. 5c). On the other hand, the transcriptome changes in viral infection periods were highly associated with ‘immunologic processes’-related pathways and terms (Fig. 4). Some ‘glucose and diabetes’-related terms showed significant enrichment but were less frequent than ‘immunologic processes’-related terms. As mentioned above, the presence of glucose terms is probably due to the overlapping between viral infection periods and glucose elevation periods, and also perhaps to the fact that viral infection may trigger glucose elevation2. Unlike previous findings for a ‘glucose elevation’ state, evidence for a presymptomatic change in transcriptome between transcriptome profiles and ‘virus infection’ states was not obvious.

Fig. 4 |. Changes in gene expression during infection.

Left panel: scaled gene expression levels of DEGs between viral infection and normal states (crimson, highest methylation level; marine, lowest methylation level); the changes in glucose levels and infection states during all measured time points are indicated at the top of the heatmap (black points, glucose levels of time points; the pink dashed line represents the upper limit of the healthy glucose level; yellow bar, HRV infection; red bar, RSV infection; blue bar, ADV infection). No clustering was performed. Middle panel: percentages of infection-related DEGs in glucose- and immune-related gene ontology terms. Right panel: percentages of infection-related DEGs in glucose- and immune-related KEGG pathways.

It is possible, but improbable, that these methylome and transcriptome changes were entirely due to differences in cell compositions. Although the composition of the first two time points of each infection differed in cell composition from the other time points, the composition of the latter time points was similar to those of the healthy samples as well as those of the other infection periods (Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, the cell composition of our PBMC samples was computationally deconvoluted using CIBERSORT20 (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Although there were minor changes of cell composition between the samples, we did not observe a strong correlation between physiological states and cell type proportions (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Most importantly, in this study we attempted to identify meta-methylomic and meta-transcriptomic profile changes in PBMCs as molecular signatures of physiological status changes, which integrated the contributions of all PBMC cell populations—the parameter we are most interested in, analogous to metagenomic mixtures.

Dynamic methylation sites associated with the onset of chronic glucose elevation overlap with regulatory elements.

To further explore potential differences of regulatory roles between differentially methylated sites associated with chronic and acute conditions, we defined cytosines differentially methylated between high-glucose-level and normal-glucose-level samples as glucose-dynamics-related differentially methylated sites (gDMSs), and cytosines differentially methylated between viral infection and non-viral infection samples as infection-related differentially methylated sites (iDMSs). We then intersected both types of DMSs with experimentally defined genomic annotations, including gene coding annotations from GENCODE19 and transcription factor binding regions from ENCODE21 (Supplementary Figs. 6c, d). The gDMSs were more significantly enriched at promoter regions (7.59%) and transcription factor binding sites (18.97%) compared to iDMSs (4.14% in promoter and 15.37% in transcription factor binding sites, respectively; chi-squared test, P value < 2.2 × 10−16 for promoters and P value < 2.2 × 10−16 for transcription factor binding sites). We also intersected both types of DMSs with functional genomic regions of different cell types predicted by chromHMM22 (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Figs. 6e and 7). Similar to the GENCODE/ENCODE annotations, gDMSs were more significantly enriched in active TSSs (2.48%) than iDMSs (0.3%) (chi-squared test, P value < 2.2 × 10−16 for gDMSs and P value < 2.2 × 10−16 for iDMSs). These results suggest that gDMSs affect more promoter regions than iDMSs, raising the possibility that glucose changes/chronic conditions affect gene expression regulation more through promoter DNA methylation than acute conditions such as viral infections.

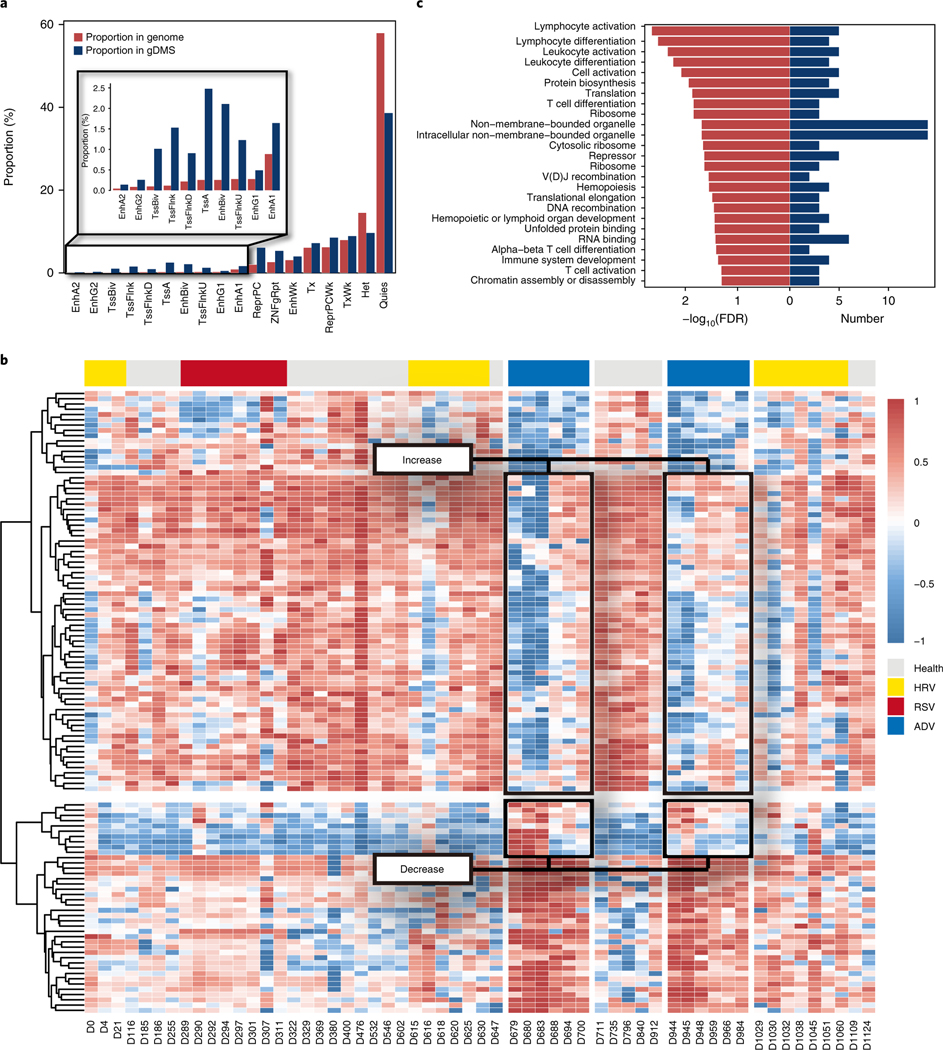

Fig. 5 |. Annotation of the differentially methylated sites related to glucose elevation and DeGs during viral infection.

a, Bar plot shows the proportion of various types of regulatory regions (defined by chromHMM, Epigenome identity: E029) in gDMSs that were significantly higher than in the whole genome. b, Heatmap of gene expression profile of 116 DEGs shared by 2 ADV infection events (gray bar, health condition; yellow bar, HRV infection; red bar, RSV infection; blue bar, ADV infection). c, Enriched gene ontology terms for the 46 DEGs (n = 33 biologically independent samples, Wilcoxon rank sum test, false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P value < 0.05) that showed downregulation at the beginning of ADV infection and were gradually upregulated until the end of the infection period.

To study the relationship between the longitudinal methylome data and known methylation markers associated with type 2 diabetes (T2D), we computed the Pearson correlation coefficients of the methylation levels of 149 reported genomic markers of T2D23 between each pair of time points. The correlations at time points before glucose-elevated periods were higher than the other periods, suggesting more aligned epigenetic regulation before glucose-elevated periods (Supplementary Fig. 6f). We further overlapped gDMSs with the known 149 methylation markers associated with T2D. Significantly, 5 of the 149 markers overlapped with gDMSs (binomial test, P value = 9.696 × 10−7). Thus, the gDMS regions identified in this study are associated with at least some of the identified T2D markers in other studies.

Dynamic gene expression changes during viral infection.

The longitudinal nature of the transcriptome data provided an opportunity to investigate gene expression dynamics in this individual across various viral infection periods. We identified genes that were differentially expressed at each of the six viral infection periods and identified shared trends of gene expression dynamics within the infection periods of the same viral type, as well as event-specific gene expression patterns. For example, the 2 ADV infection periods shared 116 DEGs compared to healthy states (Wilcoxon rank sum test, false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P value <0.05) and these 116 genes showed similar time-course dynamics in the 2 ADV infections (Fig. 5b). In addition to genes that were consistently upregulated or downregulated during the whole ADV infection periods, a total of 56 genes showed expression level changes at specific times during the infection periods. Of these 56 genes, 46 were downregulated at the beginning of the infection and became gradually upregulated until the end of the infection period; 10 genes showed reverse dynamic patterns. These ‘ADV dynamic’ genes were enriched in immunological biological functions, especially immune response terms such as ‘lymphocyte activation’ and ‘leukocyte activation’ (Fig. 5c). In addition to the 56 dynamic genes that were shared by the 2 ADV infection events, we also identified 582 and 420 genes that were specific to the first and second ADV infection events, respectively. These infection-event-specific genes also showed a variety of time-course dynamic expression patterns (Supplementary Fig. 8). Not surprisingly, the genes specific to the two ADV infection events were enriched for immunological functions. However, we also found event-specific terms, such as ‘innate immune response’ and ‘inflammatory response’ for the first ADV infection and ‘T cell activation’ for the second ADV infection (Supplementary Table 4). These event-specific enriched terms might imply distinct responses to different viral infection scenarios.

Allele-specific methylation regions were stable over time.

We previously phased the personal genome of the participant2,24, which enabled us to determine here the DNA methylation patterns for each parental allele. The allele-specific methylation patterns can be either imprinted by parent of origin or associated with genotypes and, in both cases, the allele-specific methylation patterns are expected to be stable, although this has not been previously tested directly.

We conducted two analyses to test whether the allele-specific methylation patterns were stable over the 1,124-day time course. First, we selected two samples with distinct health states (day 289 and day 311, denoted as S1 and S2, respectively) and sequenced their bisulfite libraries to high depths. A total of 1.50 billion (25 × per strand) and 2.69 billion (44.8 × per strand) uniquely mapped non-identical reads were obtained for S1 and S2, respectively. We used the heterozygous single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from the phased genome to determine allele-specific DNA methylation (ASM) and assigned 489 million reads from S1 (32.54% of total reads) and 703 million reads from S2 (26.14% of total reads) to 1 of the 2 parental alleles, respectively. The ASM was determined for each of the cytosines that was covered by at least five reads on each allele using Fisher’s exact test. A total of 270,288 ASM cytosines passed the significance test, among which 182,274 (67.44%), 27,142 (10.04%) and 60,372 (22.34%) were located in CG, CHG, and CHH contexts, respectively. The majority of ASM events (92.53%) were from direct disruption or formation of CpG dinucleotides (an example is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9a). A total of 18,840 ASM events in CG context, 360 ASM events in CHG context and 966 ASM events in CHH context remained after removing the single nucleotide variant (SNV) ASM events. We observed a high correlation of allele-specific methylation patterns between the two samples (Pearson correlation R2 = 0.9729), indicating that the allele-specific methylation patterns were stable between these two states (Supplementary Fig. 9b).

We next identified allele-specific methylation loci for 26 time points (2 time points, D602 and D948, were excluded due to lower coverage). The allelic identities of over 99.99% of the allele-specific methylation loci were stable over time, with only minor allelic ratio changes (Fig. 6a and Methods). To understand why the small percentage of the outlier loci (< 0.01%) had the allelic identity switched between time points, we performed further analyses on these loci and found that the changes were most probably artifacts due to low read coverage. Therefore, the allele-specific methylation patterns were stable longitudinally.

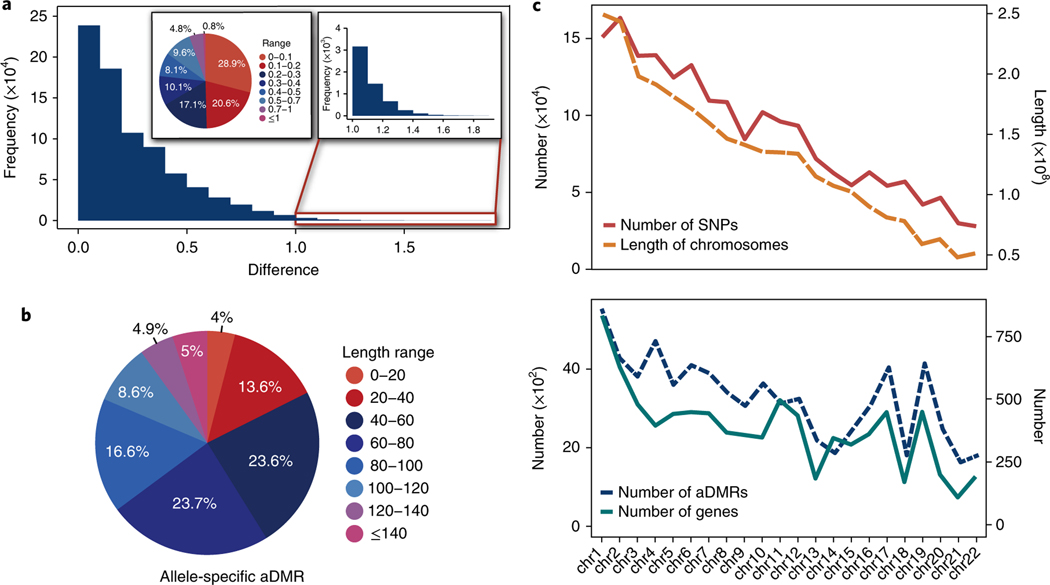

Fig. 6 |. Allele-specific methylation regions profile.

a, Histogram shows the distribution of the number of allele-specific methylation sites with the largest changes among samples. The x axis denotes the absolute value of the largest changes of methylation percentage; the y axis denotes the numbers of sites. The pie chart shows the ratio of sites with methylation-level changes. Almost all of the allele-specific identities of the allele-specific methylation loci were consistent over time. b, Pie chart shows the fraction of different lengths of allele-specific DMRs. c, Upper panel shows the distribution of numbers of SNPs and length of chromosomes; lower panel shows the distribution of the numbers of aDMRs (right y axis) and the total numbers of genes in each chromosome (left y axis) (n = 28 independent samples). The numbers of aDMRs are highly correlated with number of genes (R2 = 0. 85, Spearman correlation).

Since the ASM loci were stable among all of the samples, we combined the reads from all of the samples, achieving high sequencing depths at each base (average depth 374.5 × ). This enabled us to characterize personalized allele-specific methylation patterns at a level that had not been achieved previously. After combining all of the data, we identified 51,373,568 cytosine loci that were covered by at least 5 reads on each allele. We identified 1,055,795 (2.1%) ASM cytosines and clustered them into 11,135 aDMRs (Supplementary Table 5 and Methods). This number is approximately 11-fold higher than any other dataset reported previously24. The length of the aDMRs ranged from 5 bp to 419 bp with a median length of 67 bp (Fig. 6b). The aDMRs were not evenly distributed across the genome. The density of aDMRs on chromosomes 4, 17 and 19 was significantly higher than the other chromosomes and the number of DMRs was highly correlated with the number of genes in each chromosome, but not with the length of the chromosome or the number of SNVs in each chromosome. These observations suggested that aDMRs might play regulatory roles in gene expression (Fig. 6c).

Discussion

We report here a 1,124-day longitudinal analysis of methylomic and transcriptomic changes in the peripheral blood molecular components of one Caucasian volunteer in extreme detail. Our results demonstrated that personal transcriptomes and personal DNA methylomes displayed distinct dynamics that associate with different physiological conditions. Significant changes of the former often occurred during more dynamic and acute health conditions, whereas the PBMC DNA methylome profiles were associated with chronic events such as glucose level elevation.

Our previous study2 explored longitudinal profiles of multiple omics data and their implications in real time and chronic human health. However, the longitudinal epigenomic profile was not analyzed. In this study, we monitored whole-genome DNA methylation and transcriptome profiles of the same generally healthy individual over a much longer period of 36 months. Although the methylome changes were modest, as might be expected for changes within a single individual, they correlated with glucose level changes. The gene expression changes were quite dramatic in magnitude and often occurred during viral infections. Since DNA methylation is generally considered to be a more stable epigenetic marker, we propose that DNA methylation may be a chronic mechanism for long-term regulation of gene expression rather than timely response to environmental stimulations.

Our results demonstrating association of differential DNA methylation with glucose level changes suggest that methylation may be a general method for long-term regulation of gene expression in individuals and, as such, may be a useful marker for following and predicting significant chronic personal health states. We further speculate that the modest methylation changes in aggregate across many promoters of metabolic genes may have a pronounced effect on chronic metabolic control.

Previous reports in ASM did not consider the dynamics of allele-specific methylation patterns. Our study confirmed that allele-specific DMRs were generally stable regardless of physiological states of human health. This finding allowed us to combine the methylome data from all of the time points, creating an ‘ultra-deep’ DNA methylation dataset for aDMR identification. We identified a much larger amount of aDMRs than previous reported (~11-fold greater than previously studies24) and, interestingly, these DMRs are not distributed randomly across the genome. Instead, the number of allele-specific DMRs is highly correlated with the number of genes on each chromosome, suggesting that aDMRs tend to co-locate with genes. It is probable that many of these events are functional, as they are associated with allele-specific gene regulation. Thus, we expect that personal methylomes have important associations with personal phenotypes.

It is important to note that our study only follows a single individual, a type of analysis that is important for precision health and medicine, in which monitoring, understanding and treating people is managed at an individual level. We are not able to ascertain how well these results extend to other individuals, and analysis of other human subjects will determine whether these results are generalizable, as expected, or whether they are truly personal molecular signatures. It is also worth noting that the primary goal is to explore the correlation between the DNA methylome and human health states, which will require additional studies to develop predictive models or clinical tests.

Regardless, using integrative, quantitative molecular signatures to predict human health states at an individual level is one of the most important goals in precision medicine. To successfully diagnose abnormal health states before canonical clinical symptoms appear, it would be crucial to detect molecular signatures of diseases in advance of their actual manifestation and define molecular symptoms. From this study, it is encouraging to observe that RNA expression and DNA methylation changes were associated with disease signatures, and DNA methylation changes were evident at time points preceding clinical symptoms, making early detection or even early prevention possible. In our current understanding, no single type of omics data is sufficient to predict precise human health states, but it may be possible to integrate multiple types of omics data to improve prediction power for a wide variety of disease types.

Methods

Subjects.

The subject in this study was recruited under the institutional review board protocol IRB-8629 at Stanford University, using written informed consent.

Sample collection.

Peripheral blood samples were collected at each time point and PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation at 400 × g for 25 min using Lymphocyte Separation Media (MP Biomedicals). Genomic DNA and RNA were isolated simultaneously from the PBMCs using the AllPrep DNA/RNA/Protein Mini Kit (QIAGEN).

WGBS (MethylC-seq).

Briefly, 5 μg genomic DNA was used for preparation of each Illumina library. The genomic DNA was mixed with 25 ng unmethylated lambda DNA (Promega) as bisulfite conversion control, and sheared with the Covaris S2 system with the following settings: use frequency sweeping, intensity 4, duty cycle 10% and bursts per second 200, for a total of 2 min. Fragmented DNA was then concentrated with QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN). The ends of the concentrated DNA were first repaired with the Epicentre End-It DNA End-Repair Kit (Epicentre/Illumina), and a deoxyadenosine was added to the 3’-end with Klenow 3’→ 5’ exo- enzyme (New England Biolabs). The end-repaired, dA-tailed DNA fragments were then ligated with Illumina’s Early Access Methylation Adapter Oligo (Catalog no. ME-100–0010). The ligated libraries were size selected for an average insert size of 300 bp by agarose gel excision and extraction, and underwent bisulfite conversion using the EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit (Zymo Research). Bisulfite-converted, adaptor-ligated DNA was then amplified with the uracil-tolerating PfuTurbo Cx Hotstart DNA polymerase (Agilent Technologies) using the following program: 98 °C 2 min, 15 cycles of (98 °C 30 sec, 60 °C 30 sec, 72 °C 30 sec), 72 °C 10 min. The final amplified libraries were further purified with the Agencourt AMPure XP SPRI beads (Beckman Coulter Genomics), and subjected to 101 base paired-end sequencing using Illumina’s HiSeq 2500 Sequencer.

Whole-transcriptome sequencing (messenger RNA sequencing).

Strand-specific RNA-seq libraries were prepared as described previously2. Briefly,5–9 μg total RNA isolated from PBMCs was used. The isolated messenger RNA was fragmented using RNA Fragmentation Reagents (Ambion) and uracil-containing complementary DNA in the second strand was synthesized using the SuperScript Double-Stranded cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher). The cDNA molecules were end-repaired with the Epicentre End-It DNA End-Repair Kit (Epicentre/Illumina), a deoxyadenosine base was added at the 3’ end of the fragments with the Klenow 3′ → 5′ exo- enzyme (New England Biolabs), and they were ligated with Illumina’s Paired-End Adaptor Oligo Mix (Part no. 1001782). The ligated libraries were size selected for an average insert size of 250 bp (2 mm gel slice) by agarose gel excision and extraction, and the uracil-containing second strands were digested with Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (New England Biolabs). The treated libraries were then amplified by PCR at the following conditions: 98 °C 30 sec, 15 cycles of (98 °C 10 sec, 65 °C 30 sec, 72 °C 30 sec), 72 °C 5 min. Each prepared library was sequenced on 1–3 HiSeq 2000 lanes (101 base paired-end).

Reads mapping and data processing.

The WGBS reads were aligned using BSMAP25 (version 2.73) to the hg19 reference assembly allowing up to three mismatches, sorted with Samtools26 (version 0.1.19), and duplicate reads were removed using Picard Tools (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/, version 1.119). Then, a python script named methratio.py downloaded with BSMAP was used to extract methylation ratios and numbers of converted and unconverted cytosines covering each locus from BSMAP mapping results. Meanwhile, the sequence of spike-in lambda DNA was included in the reference, so that the read from unmethylated lambda DNA could be mapped and analyzed as control. The bisulfite conversion rates for control samples ranged from 98.48% to 99.85%; median was 99.6%. At each reference CpG the binomial test was used to identify whether this cytosine was methylated, using a 0.05 q-value. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to identify iDMS, gDMSs and differentially methylated genes, as well as DEGs. ASM for each cytosine was identified by Fisher’s exact test. ASM sites and aDMRs were defined by merging allele-specific methylated cytosines on the same allele that were less than 50 bp apart. Merged genomic regions that contained five or more allele-specific methylated cytosines were reported as aDMR.

RNA-seq data were aligned to the GRCh37 (hg19) reference genome using the STAR package27 (version 2.3.0e), followed by Cufflinks28 (version 2.2.1) for transcript assembly and RNA expression analysis. The sva R package (version 3.12.0) was used for background correction18. The Samtools26 package (version 0.1.19) was used to identify variants including SNVs and indels. A summary of RNA-seq read statistics is provided in Supplementary Table 6.

Annotation data sources.

All genomic coordinates were based on the GRCh37 (hg19) reference genome annotation. Promoter was defined as upstream 1,000 bp from gene transcript start sites, and TSS, TES, utr5, utr3, exon, CpG-island and mapped Chip-seq data for transcription factor binding were all downloaded from the ENCODE database on the UCSC genome browser. The 18-state ChromHMM annotation of different cell types was downloaded from Roadmap Epigenome29, 30. Gene ontology biological process term and KEGG pathway annotation were downloaded from GSEA MsigDB database version 6.0.

Promoter methylation analysis.

The methylation level of the 1,000-bp promoter that contained at least 1 cytosine was calculated using formula:

where Ci represents the count of unconverted reads in promoter i, and CTi represents the total number of reads.

Calling DMRs using BSmooth.

The DMRs were identified using the BSmooth algorithm18 from the bsseq package (version 3.7) within Bioconductor. For each comparison, only CpG sites with coverage of at least five reads in all compared samples were included in our analysis. T-statistic cut-offs of –4.6, 4.6 and methylation difference greater than 10% were used for identifying DMRs. We also filtered out DMRs that did not have at least three CpGs.

Differentially methylated promoters between different glucose level periods.

Differentially methylated promoters between different glucose periods had to fulfill the following criteria: (1) they were missing methylation level detection at ≤ 1 time point in each glucose period, and (2) they had a P value <0.05 using one-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Differentially methylated promoters between two adjacent time points.

Events were categorized as being differentially methylated promoters at adjacent time points if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) they were covered by more than five reads, (2) the difference in methylation level between the two time points was greater than two-fold, and (3) they had a P value < 0.05 using chi-squared test.

Gene set enrichment analysis.

For DEGs, the gene ontology and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed using Functional Annotation Tool of DAVID bioinformatics 6.7 with default parameters on a gene list of DEGs’ enstID. An in-house python script was used to define significant gene enrichment in gene ontology terms and KEGG pathways using hypergeometric test (scipy packages version 0.18.0).

Functional interpretation of DMRs.

For DMRs, the functional interpretation was performed using GREAT31 3.0.0 with default parameters.

Identification of ASM sites and aDMRs.

Mapped MethylC-seq reads were assigned to one of the two alleles based on the vote of heterozygous SNPs within the reads. If the SNP contained cytosine, the bisulfite-converted equivalent (thymine) was also considered. After the reads were assigned to the alleles, the ASM for each cytosine was identified by Fisher’s exact test. Only cytosines covered by at least five reads on each allele were considered for the tests. Cytosines with P value smaller than 0.05 were considered allelic differentially methylated. DMRs are identified by merging allele-specific methylated cytosines on the same allele that were less than 50 bp apart. Merged genomic regions that contained five or more allele-specific methylated cytosines were reported as aDMR.

Data availability

The GEO accession number for all of the MethylC-seq and RNA-seq datasets generated in this study is GSE111405. For RNA-seq data from day 0 to day 400 (published previously2), the GEO accession number is GSE33029.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: 5U54DK10255603 and 5P50HG00773503 (M.S.); by grants 91631111, 31571327 and 31771426 from Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (D.X.); as well as by funding from Stanford University. M.S. is a cofounder and member of the scientific advisory board of Personalis and Q-bio.

Footnotes

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, statements of data availability and associated accession codes are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0237-x.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0237-x.

References

- 1.Ball MP et al. Harvard Personal Genome Project: lessons from participatory public research. Genome Med. 6, 10 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen R et al. Personal omics profiling reveals dynamic molecular and medical phenotypes. Cell 148, 1293–1307 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hood L & Friend SH Predictive, personalized, preventive, participatory (P4) cancer medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 8, 184–187 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li-Pook-Than J & Snyder M iPOP goes the world: integrated personalized omics profiling and the road toward improved health care. Chem. Biol 20, 660–666 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder M, Du J & Gerstein M Personal genome sequencing: current approaches and challenges. Genes Dev. 24, 423–431 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mias GI & Snyder M Personal genomes, quantitative dynamic omics and personalized medicine. Quant. Biol 1, 71–90 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horvath S DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 14, R115 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanzleiter T et al. Exercise training alters DNA methylation patterns in genes related to muscle growth and differentiation in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab 308, E912–E920 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowlands DS et al. Multi-omic integrated networks connect DNA methylation and miRNA with skeletal muscle plasticity to chronic exercise in Type 2 diabetic obesity. Physiol. Genomics 46, 747–765 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gertz J et al. Analysis of DNA methylation in a three-generation family reveals widespread genetic influence on epigenetic regulation. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002228 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ideraabdullah FY, Vigneau S & Bartolomei MS Genomic imprinting mechanisms in mammals. Mutat. Res 647, 77–85 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y & Sasaki H Genomic imprinting in mammals: its life cycle, molecular mechanisms and reprogramming. Cell Res. 21, 466–473 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergman Y & Cedar H DNA methylation dynamics in health and disease. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 20, 274–281 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kundaje A et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature 518, 317–330 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lister R et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature 462, 315–322 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lister R et al. Highly integrated single-base resolution maps of the epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell 133, 523–536 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panda K et al. Full-length autonomous transposable elements are preferentially targeted by expression-dependent forms of RNA-directed DNA methylation. Genome Biol. 17, 170 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen KD, Langmead B & Irizarry RA BSmooth: from whole genome bisulfite sequencing reads to differentially methylated regions. Genome Biol. 13, R83 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrow J et al. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome Res. 22, 1760–1774 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman AM, Liu CL & Green MR Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 12, 453–457 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kellis M et al. Defining functional DNA elements in the human genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 6131–6138 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ernst J & Kellis M Chrom HMM: automating chromatin-state discovery and characterization. Nat. Methods 9, 215–216 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wahl S et al. Epigenome-wide association study of body mass index, and the adverse outcomes of adiposity. Nature 541, 81–86 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuleshov V et al. Whole-genome haplotyping using long reads and statistical methods. Nat. Biotechnol 32, 261–266 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 25.Xi Y & Li W BSMAP: whole genome bisulfite sequence MAPping program. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 232 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobin A et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trapnell C et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc 7, 562–578 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kundaje A et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature 518, 317–330 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.http://egg2.wustl.edu/roadmap/data/byFileType/chromhmmSegmentations/ChmmModels/core_K27ac/jointModel/final/all.mnemonics.bedFiles.tgz (2018).

- 31.McLean CY et al. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat. Biotechnol 28, 495–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The GEO accession number for all of the MethylC-seq and RNA-seq datasets generated in this study is GSE111405. For RNA-seq data from day 0 to day 400 (published previously2), the GEO accession number is GSE33029.