Abstract

Objectives

To observe skeletal width changes after mini-implant–assisted rapid maxillary expansion (MARME) and determine the possible factors that may affect the postexpansion changes using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) in young adults.

Materials and Methods

Thirty-one patients (mean age 22.14 ± 4.76 years) who were treated with MARME over 1 year were enrolled. Four mini-implants were inserted in the midpalatal region, and the number of activations ranged from 40 to 60 turns (0.13 per turn). CBCT was performed before MARME (T0), after activation (T1), and after 1 year of retention (T2). The mean period between T1 and T0 was 6 ± 1.9 months and between T2 and T1 was 13 ± 2.18 months. A paired t-test was performed to compare T0, T1, and T2. The correlations between the postexpansion changes and possible contributing factors were analyzed by Pearson correlation analysis.

Results

The widths increased significantly after T1. After T2, the palatal suture width decreased from 2.50 mm to 0.75 mm. From T1 to T2, decreases recorded among skeletal variables varied from 0.13 mm to 0.41 mm. This decrease accounted for 5.75% of the total expansion (2.26 mm) in nasal width (N-N) and 19.75% at the lateral pterygoid plate. A significant correlation was found between postexpansion change and palatal cortical bone thickness and inclination of the palatal plane (ANS-PNS/SN; P < .05).

Conclusions

Expanded skeletal width was generally stable after MARME. However, some amount of relapse occurred over time. Patients with thicker cortical bone of the palate and/or flatter palatal planes seemed to demonstrate better stability.

Keywords: Maxillary expansion, Mini-implants, Long-term effects

INTRODUCTION

Transverse maxillary deficiency is considered a common problem,1,2 reported to affect 7.9% of adolescents and nearly 10% of adults.3 This problem is often associated with a high arched palate, unilateral or bilateral posterior crossbite, and dental crowding, which could be underlying factors causing parafunction of the masticatory system.4,5

Rapid maxillary expansion (RME) is a widely used and accepted method for the correction of maxillary constriction in children. However, the fused, mature midpalatal suture and adjacent articulations limit the desired results for nongrowing patients using conventional RME.6,7 Conventional tooth-anchored RME use could cause dentoalveolar tipping, less skeletal movement, and lack of long-term stability.8,9

To reduce possible unwanted side effects, mini-implant–assisted rapid maxillary expansion (MARME) was designed to increase the maxillary width in nongrowing patients using four mini-implants placed in the cortical bone of the palate and nasal floor (NF).10–12 Previous studies found that MARME could produce more favorable orthopedic and less dentoalveolar side effects as compared with conventional tooth-borne RME.10,13,14 A study comparing tooth-borne expanders and bone-borne expanders reported that the use of bone-borne expansion in the adolescent population increased the extent of skeletal changes in the range of 1.5 to 2.8 times compared with that of tooth-borne expansion and did not result in any dental side effects.15

In terms of stability after MARME, Choi et al.16 reported skeletal changes and acceptable stability of MARME using posteroanterior cephalometric records and dental casts. More detailed information regarding the skeletal changes might be more appropriately studied using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT). In previous studies, hard palate (HP) thickness was found to affect the increase in maxillary width by MARME,17 and the rigidity of palatal bone was reported to be closely related to the width changes.18,19 However, few studies have evaluated the stability of skeletal width and factors contributing to stability after MARME in adults.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to observe changes in skeletal width after MARME and investigate the possible factors that potentially affected postexpansion changes using CBCT in young adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This retrospective study involved 31 young adults (19 women and 12 men, mean age 22.14 ± 4.76 years, range: 18–33 years) who underwent MARME followed by orthodontic treatment at the department of orthodontics, Shandong University Dental Hospital, from January 2017 to December 2018. Before treatment, all selected patients were informed regarding the study, and informed consent was signed by each patient. In addition, ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Shandong University Dental Hospital (No. 20180102).

Inclusion criteria were (1) 5 mm or greater of maxillomandibular width discrepancy with narrow palatal roof,20 (2) no history of orthodontic treatment or orthognathic surgery, (3) comprehensive and good-quality CBCT images, (4) no tooth extraction, and (5) no severe syndromes such as cleft lip or palate. Three patients were excluded because of loose mini-screws, and the success rate was approximately 92%. In addition, 12 patients were excluded for having extractions in the retention phase, thus possibly affecting measurements made in the T2 CBCT.

Treatment Protocol

A maxillary skeletal expander type II (Biomaterials Korea, Seoul, South Korea; Figure 1A) was designed for each patient according to the protocol of Moon et al.21 Previous studies have reported that digital planning is a successful method for maxillary skeletal expansion.22 The jackscrew was oriented in the midpalatal region between the maxillary first molars and close to the palatal tissue to enable fixation for the insertion of mini-implants. The length of the mini-implants was 11 mm, and the thickness of the jackscrew was 2.3 mm, providing a depth of 8.7 mm for the insertion of mini-implants. Four mini-implants were inserted along guided slots of the jackscrew. Each had a diameter of 1.5 mm. The jackscrew was activated one turn (0.13 mm per turn) per day, and the amount of activation was performed according to the amount of maxillary width deficiency of each patient evaluated by CBCT before MARME, ranging from 40 to 60 turns. Once the expansion was done, the jackscrew was locked for at least 3 months to stabilize the expansion.

Figure 1.

(A) Mini-implant assisted rapid maxillary expander (MARME). (B) Jackscrew and four mini-implants were maintained in the palate for retention.

After about 3 months of retention, the stainless steel arms were removed but the jackscrew and four mini-implants in the palatal region of the patients were maintained as a passive retainer, and orthodontic alignment treatment was started. The jackscrew and four mini-implants were kept in place until the brackets were debonded (Figure 1B).

CBCT Scan and Measurement

CBCT images were obtained before treatment (T0), after retention (T1), and after debonding (T2). The mean period between T1 and T0 was 6 ± 1.9 months and between T2 and T1 was 13 ± 2.18 months. CBCT scans were obtained using a NewTom 5GX-ray scanner (Quantitative Radiology, Verona, Italy), which was set at 110 kV and 7.33 Ma while acquiring a total of 538 slices with a 4.8-second scan with an 18 × 16-cm field of view and a standard voxel size of 0.3 mm. The digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) format was imported into Dolphin imaging 11.8 (Chatsworth, Calif).

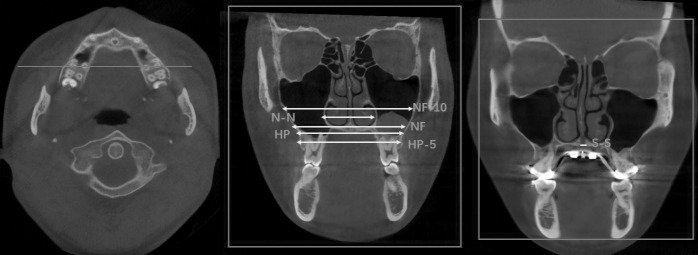

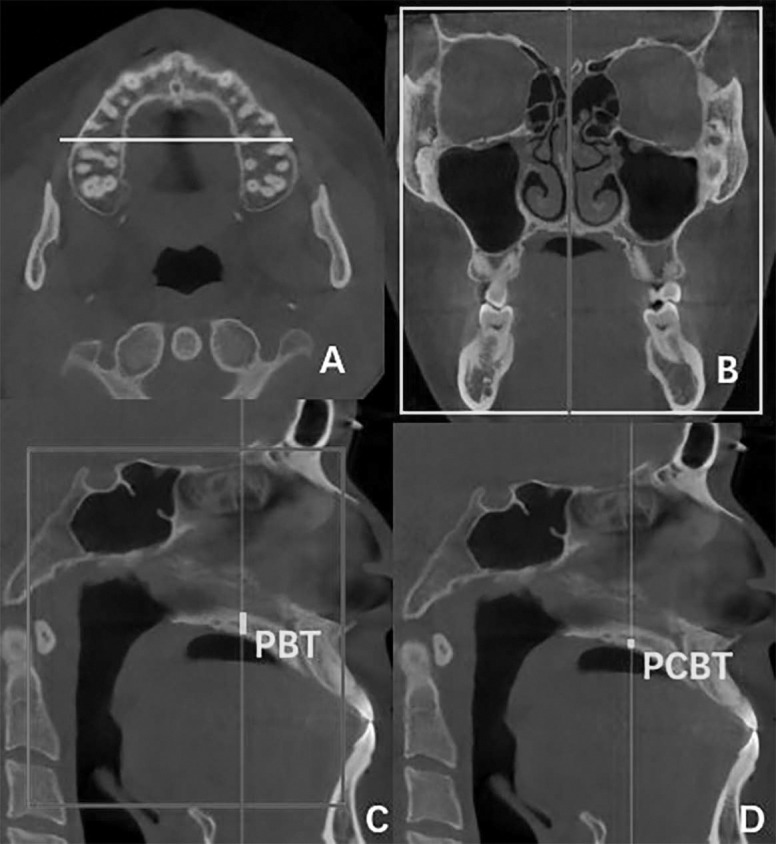

The images were reoriented along the palatal suture, tangent to the nasal floor and parallel to the palatal plane.23 The skeletal width parameters are shown in Figures 2 and 3. Then, the measured coronal images were oriented by the coronal line that was positioned at the center of the palatal root canal in the most apical region of the maxillary first molars on the right and left sides (if the left and right root canal were not at one coronal line, choosing the midpoint). The possible factors affecting stability, including palatal bone thickness (PBT), palatal cortical bone thickness (PCBT), and inclination of the palatal plane (ANS-PNS/SN) were measured at the midsagittal plane (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

NF, maxillary width tangent to the nasal floor at its most inferior level; HP, maxillary width parallel to the lower border of the CT image and tangent to the hard palate; HP5, maxillary width parallel to the line NF and 5 mm below the line HP; N-N, nasal width between the most lateral walls of the nasal cavity; NF10, maxillary width parallel to the line NF and 10 mm above the line NF; S-S, posterior midpalatal suture width at the HP level.

Figure 3.

(A) Orientation of coronal image identical to Figure 3. (B) Orientation of the sagittal image along the midpalatal suture. (C) PBT, palatal bone thickness. (D) PCBT, palatal cortical bone thickness.

Figure 4.

Lpt-Lpt, linear distance between the left and right lateral pterygoid plate measured at the axial slice crossing the palatal plane; Z-Z, linear distance between the foramina of the left and right zygomatic bones measured at the axial slice; T-T, linear distance between the left and right temporal bone measured at the axial slice crossing the inferior border of joint tubercle.

Statistical Analysis

Two operators performed the measurements, and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) of Fleiss were used to check the interobserver reliability. The measures were repeated after 2 weeks. The method error was calculated to test the reproducibility of the measurements.24

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 21.0, Chicago, Ill). The normality of the data was checked by Shapiro-Wilk test. The means and standard deviations of the measurements were calculated, and the paired t-test was used to compare among T0, T1, and T2. The significance level was determined as P < .05. Correlations between width changes (T2-T1 relapse) and PBT, PCBT, and ANS-PNS/SN were analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis and linear regression analysis.

RESULTS

At T1, all width measurements showed significant increases (P < .05). The width increases were found in a triangular pattern, with the largest increase at HP5 (2.94 ± 1.32 mm) and the least at T-T (1.31 ± 1.04 mm).

At T2, decreases observed in the skeletal measures varied from 0.13 to 0.41 mm. The smallest rate of decrease was noted at N-N. The amount of decrease (0.13 mm) accounted for 5.75% of the total expansion (2.26 mm). The largest rate of decrease was 19.75% for the lateral pterygoid plate (Lpt-Lpt; Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Width Comparisons Among T0, T1, and T2

| Parameter |

T0 (Mean ± SD) |

T1 (Mean ± SD) |

T2 (Mean ± SD) |

T1-T0 |

T2-T1 |

T2-T0 |

(T1-T2)/ T1-T0, % |

PT1-T0 |

PT2-T1 |

PT2-T1 |

| NF | 68.92 ± 5.53 | 71.25 ± 5.70 | 70.90 ± 5.72 | 2.33 ± 1.22 | −0.35 ± 0.33 | 1.98 ± 1.29 | 15.02 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| HP | 65.53 ± 4.93 | 68.18 ± 5.13 | 67.76 ± 5.16 | 2.65 ± 0.98 | −0.41 ± 0.35 | 2.23 ± 1.08 | 15.47 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| HP5 | 62.28 ± 4.32 | 65.21 ± 4.56 | 64.85 ± 4.65 | 2.94 ± 1.32 | −0.37 ± 0.41 | 2.56 ± 1.46 | 12.59 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| NF10 | 80.35 ± 8.25 | 82.63 ± 8.23 | 82.35 ± 8.27 | 2.28 ± 1.32 | −0.27 ± 0.33 | 2.00 ± 1.31 | 11.84 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| N-N | 33.74 ± 2.81 | 36.00 ± 2.59 | 35.86 ± 2.55 | 2.26 ± 1.08 | −0.13 ± 0.16 | 2.12 ± 1.08 | 5.75 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Z-Z | 103.57 ± 5.07 | 105.02 ± 4.89 | 104.74 ± 4.82 | 1.45 ± 1.04 | −0.28 ± 0.32 | 1.17 ± 0.95 | 19.31 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Lpt-Lpt | 57.33 ± 4.63 | 58.90 ± 4.68 | 58.59 ± 4.60 | 1.57 ± 0.82 | −0.31 ± 0.29 | 1.26 ± 0.89 | 19.75 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| T-T | 119.13 ± 8.37 | 120.44 ± 8.33 | 120.21 ± 8.35 | 1.31 ± 1.04 | −0.23 ± 0.24 | 1.08 ± 1.06 | 17.56 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| S-S | 0.12 ± 0.07 | 2.50 ± 1.41 | 0.75 ± 0.34 | 2.38 ± 1.33 | −1.75 ± 0.37 | 0.63 ± 0.32 | * | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

The midpalatal suture width increased significantly from 0.32 mm at T0 to 2.50 mm at T1 and subsequently decreased to 0.75 mm at T2.

In addition, a significant positive correlation was observed between PCBT and postexpansion change (T2-T1) in NF, HP, and Lpt-Lpt (P < .05), which indicated less relapse of expansion width in patients with greater PCBT. A negative correlation was observed between postexpansion change (T2-T1) and ANS-PNS/SN at NF, HP, and HP5 (P < .05), indicating less relapse of expansion width in patients with flatter ANS-PNS/SN (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pearson Correlation Coefficient Between the Postexpansion Changes (T2-T1) and Relative Variables

| Variable |

PCBT |

PBT |

ANS-PNS/SN |

| NF | 0.373* | 0.269 | −0.438* |

| HP | 0.429* | 0.296 | −0.534* |

| HP5 | 0.259 | 0.221 | −0.455* |

| NF10 | 0.302 | 0.122 | −0.281 |

| N-N | −0.027 | −0.084 | −0.261 |

| Z-Z | −0.005 | −0.046 | −0.350 |

| Lpt-Lpt | 0.449* | 0.273 | −0.322 |

| T-T | 0.007 | 0.008 | −0.321 |

| S-S | 0.328 | 0.474 | −0.255 |

Represents a significant correlation, P < .05.

The ICC values ranged from .91 to .93, showing excellent interobserver reliability. The method error varied from 0.09 to 0.20 mm for the measurements.

DISCUSSION

After MARME, transverse maxillary deficiencies of the patients enrolled in this study were resolved, which allowed for correction of their malocclusions in three dimensions. Stable increases in skeletal width from T0 to T2 were accomplished, even though a small amount of relapse was noted, comparing T2 to T1. Correlations between postexpansion changes and palatal cortical bone thickness and ANS-PNS/SN were observed.

Between T0 and T1, significant increases were observed in HP5 (2.94 mm), HP (2.65 mm), NF (2.33 mm), N-N (2.26 mm), and NF10 (2.28 mm), which described a pyramidal expansion pattern with the largest increase near the occlusal level, followed by the nasal level, and least in the adjacent bones.25,26 The midpalatal suture width of the HP increased from 0.12 mm to 2.50 mm on average during expansion. Because of the effects on the circumaxillary sutures, transverse increases were also detected at the zygomatic bone (Z-Z, 1.45 mm), temporal bone (T-T, 1.31 mm), and lateral pterygoid plate (Lpt-Lpt, 1.56 mm), in agreement with previous studies.27–30

During the MARME retention phase, the amount of relapse recorded in the skeletal variables varied from 0.13 to 0.41 mm, whereas the midpalatal suture width decreased from 2.50 mm to 0.75 mm. The smallest rate of width decrease was noted at the level of the nasal cavity, namely, a decrease of 0.13 mm, which accounted for 5.75% of the total expansion (2.26 mm), indicating that the increase in the nasal cavity was relatively irreversible. Consequently, this could also be associated with an increase in the width of alae nasi, which could influence the esthetics of patients by alar widening. Therefore, caution in using MARME might be warranted in some patients. The largest rate of relapse was 19.75% for the lateral pterygoid plate, followed by the zygomatic width (19.31%) and temporal width (17.56%). The midpalatal suture width at the HP level decreased by 1.75 mm on average from T1 to T2, which accounted for 70% of the total expansion (2.50 mm), whereas the amount of decreased width of HP was only 0.41 mm. It could be speculated that the reduction of the midpalatal suture width might have been mainly derived from bone remolding.

It is necessary to retain the effects of expansion using a rigid device, because the opened palatal suture has a tendency to close and is influenced by periosteal, fascial, and muscular tension during masticatory movement. Three months is generally advised for consolidation after expansion.31–33 In the current study, the jackscrew and four mini-implants were kept in place in the midpalatal region of patients as a MARME retainer for more than 1 year, and favorable stability was observed.

Interestingly, there was a significant correlation between palatal cortical bone thickness, ANS-PNS/SN, and postexpansion change. That indicated that thicker palatal cortical bone tended to increase the bony support of the maxillary halves, thus increasing the stability of postexpansion. The rigidity of the palatal bone could affect the maxillary changes and stability after MARME.15–17 Those findings may indicate that a MARME retainer might be an effective device for patients whose palatal cortical bone was relatively thicker, whereas it might not be as effective for patients whose palatal cortical bone was relatively thinner. In addition, a significant correlation with ANS-PNS/SN showed that a flat palatal plane may be more conducive to the installation of the four mini-implants, thus being beneficial to the maintenance of width. It might also have been related to less muscular tension and effects of muscle function on the maxilla in subjects with flat palatal planes, thus leading to more stable skeletal width changes.

In the present study, we did not measure the dentoalveolar and tooth width changes to examine the effect of orthodontic tooth movement on the arch form. However, further studies with a larger sample would be beneficial.

CONCLUSIONS

After MARME treatment, changes in skeletal width were generally stable, although some small amounts of relapse occurred depending on the location examined.

Patients with a thicker cortical bone of the palate and/or a flatter palatal plane appeared to demonstrate better stability after MARME in the short term.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients for their cooperation and contribution to the study. We also thank Shandong University Dental Hospital for providing equipment. This research received a grant from a foundation of the key research and development projects of Shandong province (2018GSF118240) and the Youth scientific research funds of the School of Stomatology, Shandong University (2019QNJJ02).

REFERENCES

- 1. .Kurol J, Berglund L. Longitudinal study and cost-benefit analysis of the effect of early treatment of posterior cross-bites in the primary dentition. Eur J Orthod. 1992;14:173–179. doi: 10.1093/ejo/14.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. .Brunelle JA, Bhat M, Lipton JA. Prevalence and distribution of selected occlusal characteristics in the US population, 1988-1991. J Dent Res. 1996;75(spec no):706–713. doi: 10.1177/002203459607502S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. .Harrison JE, Ashby D. Orthodontic treatment for posterior cross-bites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002. CD000979.

- 4. .Lagravere MO, Carey J, Heo G, Toogood RW, Major PW. Transverse, vertical, and anteroposterior changes from bone-anchored maxillary expansion vs traditional rapid maxillary expansion: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:304e301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. .Isola G, Anastasi GP, Matarese G, et al. Functional and molecular outcomes of the human masticatory muscles. Oral Dis. 2018;24:1428–1441. doi: 10.1111/odi.12806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. .Kokich VG. Age changes in the human frontozygomatic suture from 20 to 95 years. Am J Orthod. 1976;69:411–430. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(76)90209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. .Melsen B, Melsen F. The postnatal development of the palatomaxillary region studied on human autopsy material. Am J Orthod. 1982;82:329–342. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90467-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. .Weissheimer A, de Menezes LM, Mezomo M, Dias DM, de Lima EM, Rizzatto SM. Immediate effects of rapid maxillary expansion with Haas-type and hyrax-type expanders: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. .Gurel HG, Memili B, Erkan M, Sukurica Y. Long-term effects of rapid maxillary expansion followed by fixed appliances. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:5–9. doi: 10.2319/011209-22.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. .Carlson C, Sung J, McComb RW, Machado AW, Moon W. Microimplant-assisted rapid palatal expansion appliance to orthopedically correct transverse maxillary deficiency in an adult. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2016;149:716–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. .MacGinnis M, Chu H, Youssef G, Wu KW, Machado AW, Moon W. The effects of micro-implant assisted rapid palatal expansion (MARPE) on the nasomaxillary complex––a finite element method (FEM) analysis. Prog Orthod. 2014;15:52. doi: 10.1186/s40510-014-0052-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. .Lee RJ, Moon W, Hong C. Effects of monocortical and bicortical mini-implant anchorage on bone-borne palatal expansion using finite element analysis. Am J Orhod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;151:887–897. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. .Lin L, Ahn H-W, Kim S-J, Moon S-C, Kim S-H, Nelson G. Tooth-borne vs boneborne rapid maxillary expanders in late adolescence. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:253–262. doi: 10.2319/030514-156.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. .Mosleh MI, Kaddah MA, Abd El Sayed FA, El Sayed HS. Comparison of transverse changes during maxillary expansion with 4-point bone-borne and tooth-borne expanders. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2015;148:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. .Celenk-Koca T, Erdinc AE, Hazar S, Harris L, English JD, Akyalcin S. Evaluation of miniscrew-supported rapid maxillary expansion in adolescents: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Angle Orthod. 2018;88:702–709. doi: 10.2319/011518-42.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. .Choi SH, Shi KK, Cha JY, Park YC, Lee KJ. Nonsurgical miniscrew-assisted rapid maxillary expansion results in acceptable stability in young adults. Angle Orthod. 2016;86:713–720. doi: 10.2319/101415-689.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. .Li Q, Tang H, Liu X, et al. Comparison of dimensions and volume of upper airway before and after mini-implant assisted rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. .Cistulli PA, Richards GN, Palmisano RG, et al. Influence of maxillary constriction on nasal resistance and sleep apnea severity in patients with Marfan's syndrome. Chest. 1996. 110:1184e8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19. .Zambon CE, Ceccheti MM, Utumi ER, et al. Orthodontic measurements and nasal respiratory function after surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion: an acoustic rhinometry and rhinomanometry study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012. 41:1120e6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20. .Baccetti T, Franchi L, Cameron CG, McNamara JA., Jr Treatment timing for rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod. 2001;71:343–350. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2001)071<0343:TTFRME>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. .Brunetto DP, Sant'Anna EF, Machado AW, Moon W. Non-surgical treatment of transverse deficiency in adults using microimplant-assisted rapid palatal expansion (MARPE) Dent Press J Orthod. 2017;22:110–125. doi: 10.1590/2177-6709.22.1.110-125.sar. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. .Cantarella D, Savio G, Grigolato L, et al. A new methodology for the digital planning of micro-implant-supported maxillary skeletal expansion. Med Devices (Auckl) 2020;13:93–106. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S247751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. .Li N, Sun W, Li Q, Dong W, Martin D, Guo J. Skeletal effects of monocortical and bicortical mini-implant anchorage on maxillary expansion using cone-beam computed tomography in young adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;157:651–661. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. .Houston WJ. The analysis of errors in orthodontic measurements. Am J Orthod. 1983;83:382–390. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(83)90322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. .Koudstaal MJ, Smeets JB, Kleinrensink G-J, Schulten AJ, van der Wal KG. Relapse and stability of surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion: an anatomic biomechanical study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(1):10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. .Zandi M, Miresmaeili A, Heidari A. Short-term skeletal and dental changes following bone-borne versus tooth-borne surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion: a randomized clinical trial study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42(7):1190–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. .Park JJ, Park YC, Lee KJ, Cha JY, Tahk JH, Choi YJ. Skeletal and dentoalveolar changes after miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion in young adults: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Korean J Orthod. 2017;47:77–86. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2017.47.2.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. .Cantarella D, Dominguez-Mompell R, Moschik C, et al. Zygomaticomaxillary modifications in the horizontal plane induced by micro-implant-supported skeletal expander, analyzed with CBCT images. Prog Orthod. 2018;19:41. doi: 10.1186/s40510-018-0240-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. .Cantarella D, Dominguez-Mompell R, Mallya SM, et al. Changes in the midpalatal and pterygopalatine sutures induced by microimplant-supported skeletal expander, analyzed with a novel 3D method based on CBCT imaging. Prog Orthod. 2017;18:34. doi: 10.1186/s40510-017-0188-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. .Li N, Wang W, Jia L, Wang XY, Ning RY, Guo J. The dentoskeletal effects of mini-implant assisted maxillary expansion on young adults with transvers maxillary deficiencies. Zhong Hua Kou Qiang Zheng Ji Xue Za Zhi. 2019;26:121–125. [Google Scholar]

- 31. .Schulte W, Lukas D. Periotest to monitor osseointegration and to check the occlusion in oral implantology. J Oral Implantol. 1993;19:23–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. .Braun S, Bottrel JA, Lee KG, Lunazzi JJ, Legan HL. The biomechanics of rapid maxillary sutural expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118:257–261. doi: 10.1067/mod.2000.108254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. .Chung CH, Goldman AM. Dental tipping and rotation immediately after surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion. Eur J Orthod. 2003;25:353–358. doi: 10.1093/ejo/25.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]