Abstract

The University of California, Los Angeles Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care (ADC) program enrolls persons living with dementia (PLWD) and their family caregivers as dyads to work with nurse practitioner dementia care specialists to provide coordinated dementia care. At one year, despite disease progression, overall the PLWDs’ behavioral and depressive symptoms improved. In addition, at one-year, overall caregiver depression, strain, and distress related to behavioral symptoms also improved. However, not all dyads enrolled in the ADC program showed improvement in these outcomes. We conducted a mixed qualitative-quantitative study to explore why some participants did not benefit and what could be changed in this and other similar dementia management programs to increase the percentage who benefit. Semi-structured interviews (N=12) or surveys (N=41) were completed with 53 caregivers by telephone, mail and online. Seven areas for potential program improvement were identified from the first 12 interviews. These included: recommendations that did not match caregivers’ perceived care needs, barriers to accessing care and utilizing resources, differing care needs based on stage of dementia, needing services not offered by the ADC, needing more education or support, behavioral recommendations that the caregiver felt did not work, and poor rapport of the dementia expert with caregivers. Despite having been identified as having had no clinical benefit from participating in the program, most caregivers (85%) reported that the program was very beneficial or extremely beneficial. Respondents identified the close, longitudinal relationship and access to a dementia care expert as particularly beneficial. This dichotomy highlights that perceived benefit for most of the interviewed caregivers was not captured with the formal instruments used by the program.

INTRODUCTION

There are an estimated 5.8 million people living with Alzheimer’s dementia in the United States.1 The diagnosis of dementia requires change in cognition and behaviors, that are severe enough to affect a person’s ability to manage their activities of daily life.2 Alzheimer’s disease causes changes in a person’s memory, insight, judgment, and ability to communicate, and is the most commonly diagnosed form of dementia.3 In America, an estimated 18.6 billion hours of unpaid caregiving from friends and family members were spent caring for people with Alzheimer’s and related dementias in 2020 which is approximated to be worth $244 billion.1 Caregiving for people with dementia is especially demanding because the loss of function, presence of behavioral symptoms, and the extended course of the disease over several years cause continued challenges.4

Many family caregivers often become overwhelmed with the responsibilities of caring for a person living with dementia (PLWD) and suffer from stress and depression.1 They often have difficulty knowing where to turn for education, guidance, and support. Appointments with the PLWD’s physician are typically consumed with medication management and laboratory results, leaving little time to discuss dementia, prognosis, behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia (BPSD), and the need for long-term planning. Community-based organizations (CBOs) can offer support and education but are often not well-integrated in the medical visit and with the healthcare system. These gaps in care led to the creation of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care (ADC) program in which advanced practice nurse Dementia Care Specialists (DCS) who are trained on the unique challenges of the PLWD and their family members, use a co-management approach to providing dementia care. The DCS educates and guides families to better understand dementia, recognizing and managing the challenges associated with the current stage of dementia and how to prepare for future needs and crises. Through longitudinal, continuous care, the DCS is available to the PLWD and their family caregivers to provide dementia-related medical management, linkages to community resources, and health education about dementia.

While the majority of PLWD and caregiver participants in the UCLA ADC had improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms or their caregivers had reduced strain, depression, or distress at one year,5 25% of dyads did not benefit based on these outcome measures. To learn why some participants did not improve, we surveyed and interviewed caregivers of 53 participants who did not demonstrate clinical benefit. Based on the information learned from this subset of caregivers, potential program modifications and improvements can be made.

METHODS

This study used a mixed-methods design using the first 1,091 dyads followed longitudinally in the ADC program. Of those 1,091 dyads, 151 caregivers were identified as not benefitting from the ADC program based on the PLWD and caregiver clinical outcomes at 1 year. Those who did not benefit were the focus of this analysis.

Description of Program.

The UCLA ADC program was created in 2011 to provide comprehensive, coordinated dementia care for PLWD and their family caregivers.6 To date, the program has cared for over 3,000 PLWD-caregiver dyads. The DCS meets with the dyad in person to perform an individualized needs assessment and create a dementia care plan. The ADC program is a longitudinal co-management model in which the DCS works with the referring physician to provide ongoing dementia care. In addition to providing medical care and support from within the healthcare system, the ADC program forms formal partnerships with CBOs and helps to connect dyads with local resources.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis.

The 151 caregivers were assigned an order through a random number process and then separated into types of caregivers (purposeful sampling) and then called in order. Approximately one-quarter of the sample was selected for semi-structured interviews, while the remaining caregivers, and those that did not want to participate in the interviews, were surveyed. Research assistants called caregivers, administered consent, and completed 12 semi-structured interviews that included both open-ended and structured responses. All telephone interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews were read in their entirety and, using content analysis, meaning units were identified as portions of the interview that provided answers to the research question.7 These meaning units were coded, grouped, and larger categories or themes were created. In an effort to increase validity, this process was repeated independently by a second researcher who was familiar with the ADC program. Emerging themes and exemplary texts were discussed among the full study team and any differences in coding were settled by group consensus. Representational quotes were used to illustrate the data.

Surveys were administered to the remaining sample of caregivers by mail, telephone, or online to provide additional insight on their experience in the program, including why the program did not seem to help them and what additional services might have been more helpful.

Measures.

Two types of measures were used. The first was to identify participants who did not respond to the program. These measures included the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q),8 a survey that assesses the caregiver’s perception of the severity of 12 dementia-related psychiatric and behavioral symptoms and the level of distress experienced by the caregiver in response to these symptoms; the Modified Caregiver Strain Index (MCSI),9 a 13-item validated tool used to assess severity of caregiver strain; the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),10 a 9-item validated tool used to assess depressive symptoms in the caregiver using the DSM-IV criteria for major depression; and the Dementia Burden Scale-Caregiver (DBS-CG)5 a composite of the NPI-Q Distress, MCSI, and PHQ-9 scales.

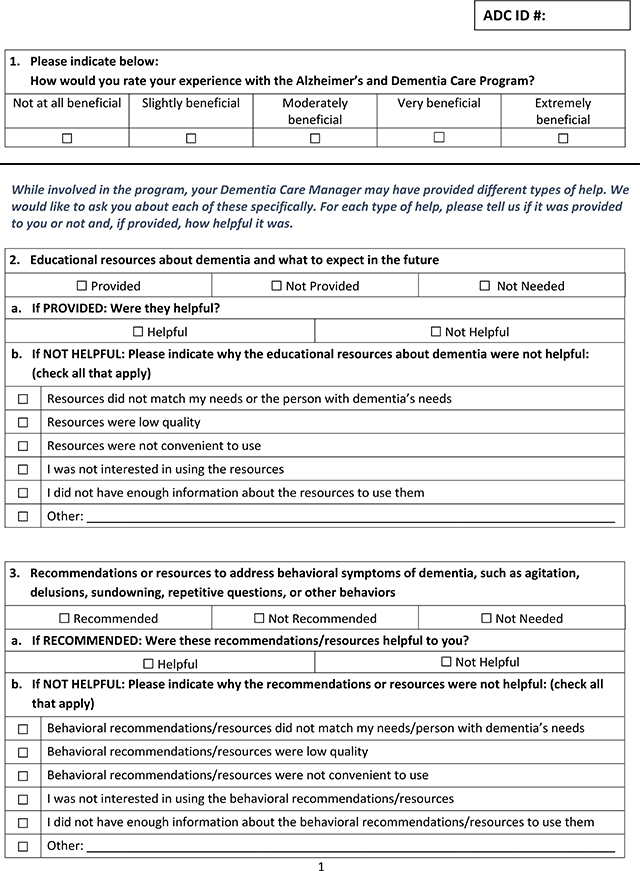

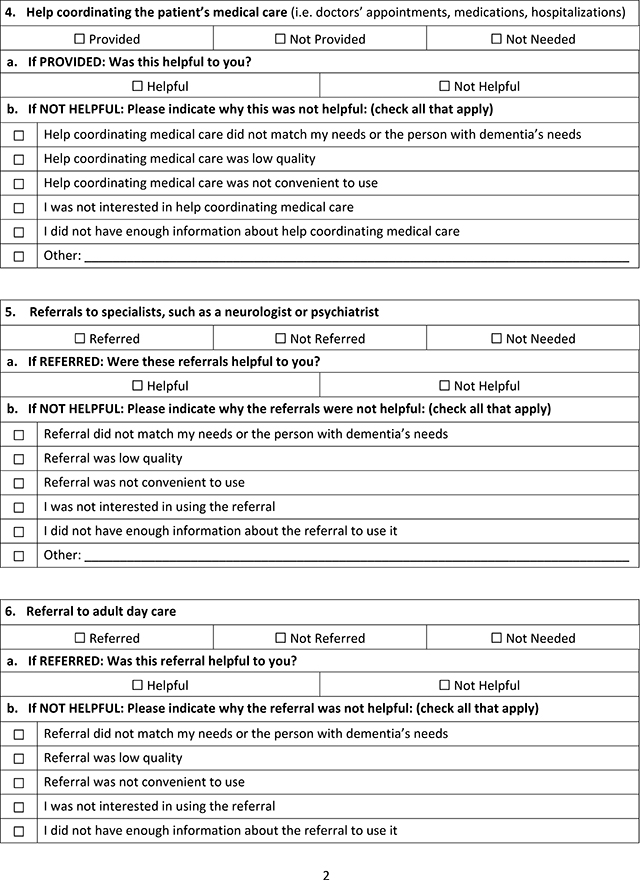

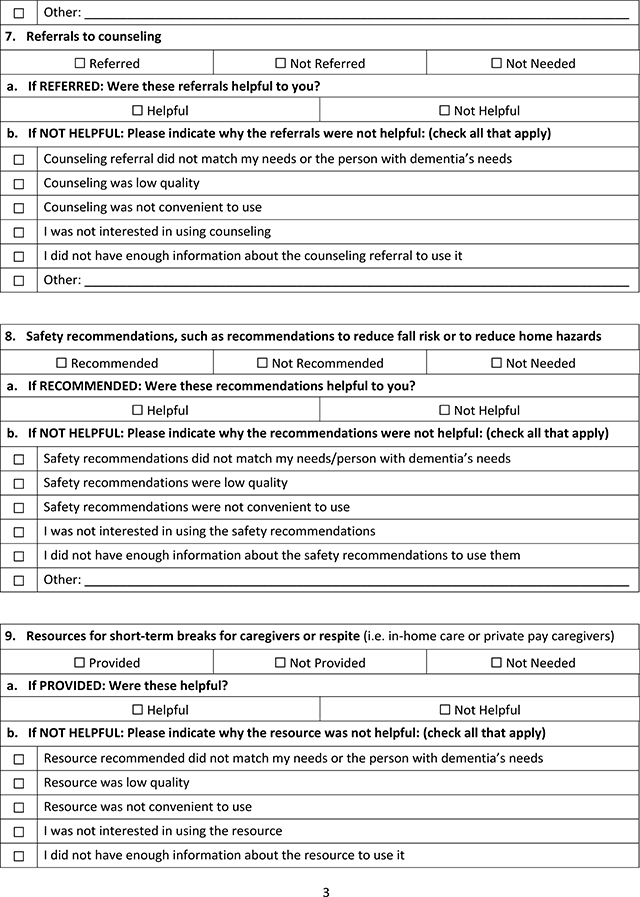

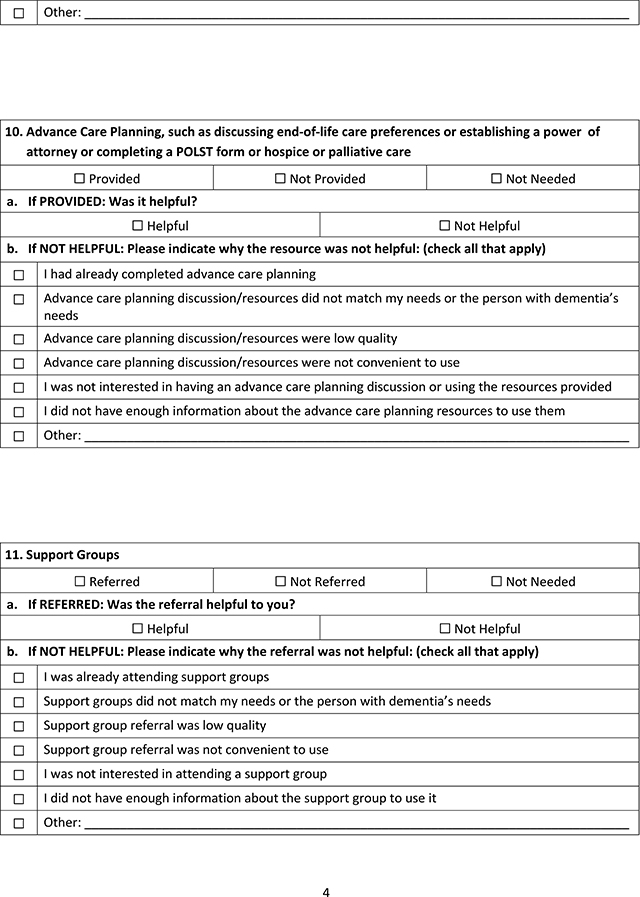

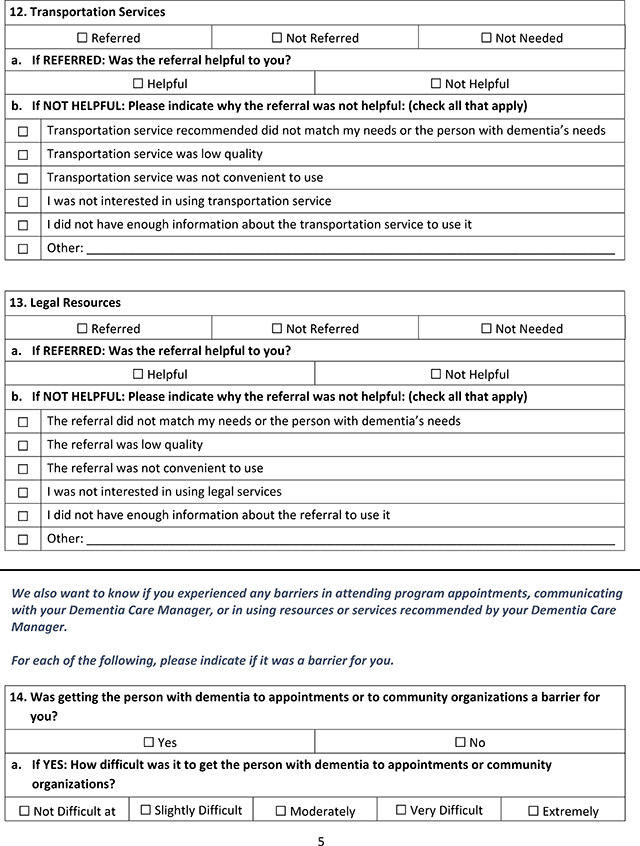

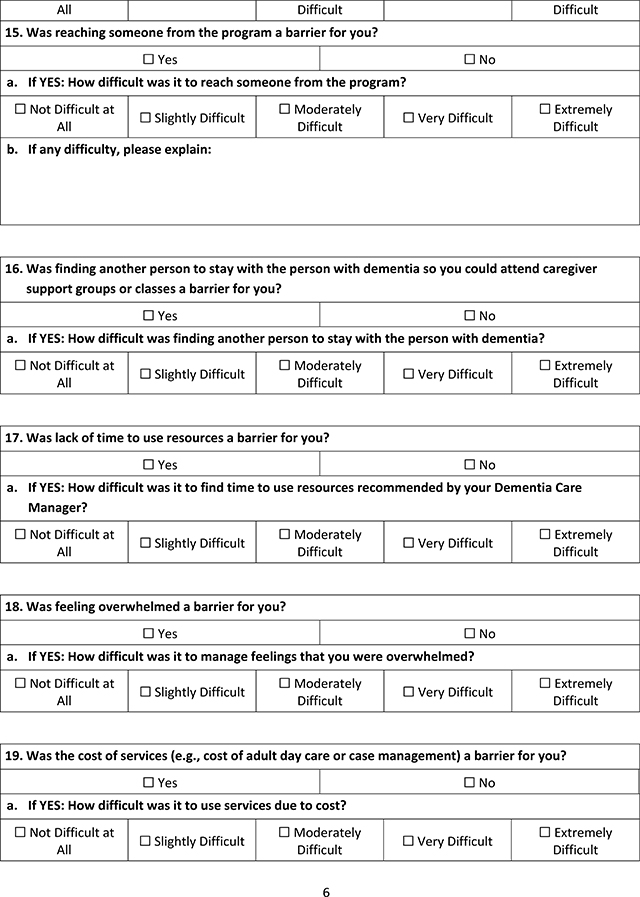

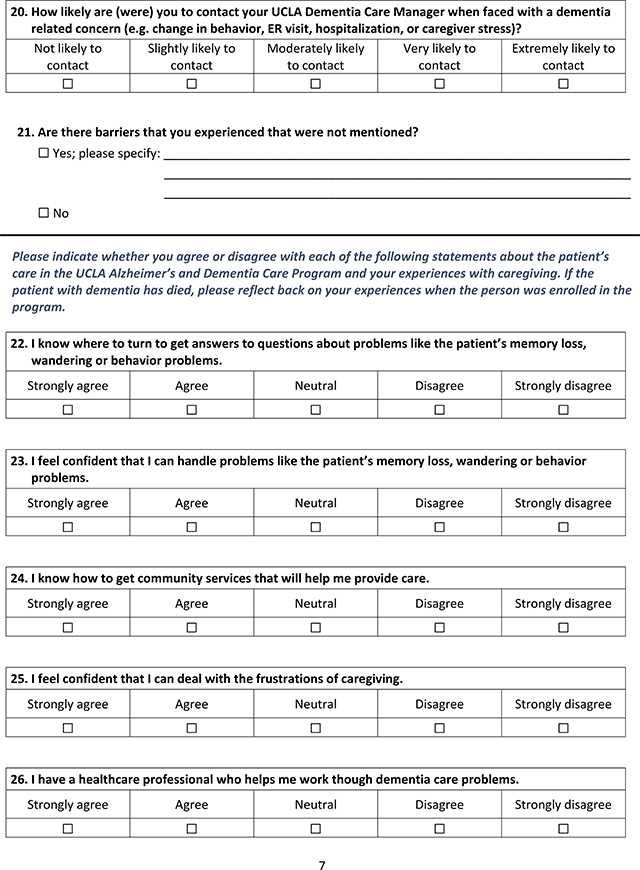

The second measures (Appendix A) were specific to this study and sought to determine why participants did not respond to the intervention and how the program could be improved. These included evaluations of specific services and referrals provided by the program, as well as identifying barriers that the caregivers believed kept them from finding the ADC helpful.

Quantitative Data Analysis.

We used the NPI-Q severity scale to define PLWD benefit (i.e., having a 1-year score of ≤ 6 or having a baseline score of > 9 and improving by at least 3 points). Three points has been previously established as the minimal clinically important difference in change in NPI-Q severity score. 11 DBS-CG benefit is scored using a possible range of 0–100. DBS-CG benefit was defined as having a 1-year score of ≤ 17.8 or having a baseline score of > 22.8 and improving by at least 5 points, the minimal clinically important difference.5 Defining benefit in this manner identified those who maintained low symptoms and had improved symptoms from the program. Those who did not benefit based on these criteria were the focus of this analysis.

Differences in sociodemographic and baseline clinical characteristics between those who completed interviews or surveys and those who did not were compared using t-tests and chi square tests, as appropriate. All analyses were performed using R version 4.0.3. The study was approved by the California State University, Fresno and the UCLA Institutional Review Boards.

RESULTS

Of 151 participants who were identified as not clinically benefitting from the program, 40 were randomly selected to be interviewed, and 12 (30%) agreed. These included 7 interviews with daughters, 2 interviews with wives, 2 interviews with husbands, and 1 interview with a son. The remaining 111 were surveyed and 41 (36%) responded. Sociodemographic characteristics of the PLWD and their caregivers who were included in the study and those who were not sampled or did not respond are provided in Table 1. Caregivers who provided responses had slightly higher NPI-Q distress scores, but these differences were below the minimal clinically important difference for this scale.

Table 1:

Caregiver characteristics stratified by survey completion, N=151.

| Variable | Did not complete surveys n = 98 (65%) | Completed interviews/surveys n = 53 (35%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 71 (72.4%) | 41 (77.4%) | 0.563 |

| Relationship to PLWD | 0.873 | ||

| Female Spouse | 23 (23.5%) | 10 (18.9%) | |

| Male Spouse | 11 (11.2%) | 8 (15.1%) | |

| Female Child | 37 (37.8%) | 24 (45.3%) | |

| Male Child | 11 (11.2%) | 4 (7.5%) | |

| Friend or other family member | 14 (14.3%) | 6 (11.3%) | |

| Paid caregiver | 2 (2%) | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Race | 0.647 | ||

| White | 58 (81.7%) | 29 (74.4%) | |

| African American | 8 (11.3%) | 5 (12.8%) | |

| Asian | 3 (4.2%) | 4 (10.3%) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Other | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| DBS-CG | 24.5 (16.8–32.2) | 30.1 (21–35.5) | 0.211 |

| MCSI (n= 142) | 9 (6–14) | 10.5 (7–14) | 0.456 |

| NPI-Q-Distress Score (n= 148) | 10 (5–14) | 12 (7–20) | 0.041 |

| Caregiver PHQ-9 (n= 148) | 3.5 (1.8–7) | 4 (2–8) | 0.642 |

DBS-CG = Caregiver Dementia Burden Score; MCSI = Modified Caregiver Strain Index; NPI-Q = Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire.

During the interviews, most caregivers (9 of the 12 interviewed) expressed their appreciation for being in the program and were surprised to hear that they had been identified as caregivers who did not benefit from the ADC program. One husband shared “Everything that [DCS] did I found helpful... I may not have taken advantage of things...but I found her attention to detail and personalizing everything... I found so very helpful. That I did.” The qualitative analysis identified seven themes around potential program improvement, including: 1) recommendations that did not match caregiver perceived care needs, 2) barriers to accessing care and utilizing resources, 3) differing care needs based on stage of dementia, 4) needing services not offered by the ADC, 5) needing more education or support, 6) behavioral recommendations that the caregiver felt did not work, and 7) poor rapport of the dementia expert with caregivers.

Recommendations did not Match Perceived Care Needs

The most commonly mentioned theme among the caregivers interviewed was the sentiment that recommendations made by the Dementia Care Specialist (DCS) did not match caregiver’s perceived care needs or were deemed to be unneeded. Examples of these recommendations include: advance care planning, referrals to specialists (e.g., neurology or psychiatry), transportation assistance, and adult day care. Home safety recommendations (e.g., home modifications, Safe Return bracelet) were most frequently reported by caregivers as unnecessary. Some caregivers felt that they had already adequately addressed safety issues while some lacked insight into risks. For example, even when the PLWD had a history of wandering, some caregivers felt that neither the Safe Return nor a GPS location system was needed. One husband said, “Well I didnť need it thank goodness because I was able to track my wife...every time she disappeared, I was able to track her down.”

Support group referrals were the next most commonly cited unneeded recommendation. Caregivers expressed several reasons why they felt support groups did not meet their perceived needs and therefore did not attend them. Some caregivers felt that a support group would not help to address their issues with caregiver burden, others felt it was an additional burden to attend, and others were not receptive to sharing concerns in a group setting. For example, when asked to describe the reason why she felt that a support group recommendation was unneeded, one wife said:

...you know we are not ready...we are not ready...when the time comes, when I am no longer able to handle it, that is going to be completely different. Right now I know I am tired, I know I need my day off or something...but like I said, I am able to handle.

Barriers to Accessing and Utilizing Care and Service

Caregivers identified several perceived barriers to accessing and utilizing recommended services including difficulties with transportation, location of services, lack of respite care, challenges with computer-based resources, and services that were not in the patienťs primary language. One caregiver described trouble getting to the appointment due to expensive parking and difficulty with physical transportation. Another caregiver explained that the recommendation for adult day programs was not helpful as the location wasnť close enough to their home. Lack of respite care was identified as a barrier to attending support groups and education classes. As one daughter shared, “Yeah, if they could do like home visits it would be easier because I cannot leave my mom alone and go... I couldnť leave my mom alone and go.”

Severe caregiver burden was another common barrier to accessing dementia care and services. Some caregivers described feeling overwhelmed with the responsibility of taking care of the PLWD, which in and of itself was a barrier. One daughter explained the difficulty she had attending a support group:

... When someone needs it the most, you’re too overwhelmed. Like caregiving, and I was finishing up school, there was no time. And thaťs why the behaviors were more challenging. Thaťs when you feel you hit rock bottom and you have to just figure it out. I’m not sure...my mom, brother and I were just figuring it out on our own. You can stay at rock bottom, you know? Because how are you going to help out your loved one?

Care Needs Varied by Dementia Stage

Caregivers also articulated that care needs changed with the progression of dementia and the appropriateness of DCS recommendations in relation to the PLWD’s stage of dementia was important. From one daughter’s perspective, getting help earlier in the disease progression would have been more valuable:

Again, for you to be an end-all, be-all and a go-to kind of thing, it would have been super helpful if I had known about you guys in the beginning...because it would have been like a one-stop shop instead of me flailing around. Because I had to pull a bunch of things together to make it work in Fresno. I think thaťs the big difference for me, I was four years in, of an eight-year journey when I met you guys, so it was like, okay, whatever. Iťs always good to have a second opinion and I already had everything in place by the time I got you guys.

For others, entering the ADC program during the late stages of the PLWD’s dementia wasnť helpful as caregivers felt they had already learned what they needed to on their own, rendering the program unnecessary. One wife felt that she had learned what she needed over time and did not see the benefit of the ADC program:

I wasnť impressed honestly...I felt like it wasted my time honestly...like pushing, pushing, pushing...and you know...when you’re taking care of somebody for so many years you donť need to go to all these places honestly...you know you already learn and iťs a daily basis you learn...

Needed Services Not Offered by the ADC

Some of the caregivers interviewed identified the need for different services that they felt werenť offered by the ADC program. For example, a caregiver cited the need for individual counseling and more in-depth one-on-one education rather than support and education in a group setting. Some caregivers requested services that were beyond what the DCS was able to accommodate or were beyond the DCS’ scope of practice. For example, a caregiver wanted the DCS to make senior living recommendations and wanted 24-hour access to their DCS in case of emergency, instead of using the on-call geriatrics practice. One daughter wanted access to a nutritionist in the ADC program “...you know what I would like, I would like a nutritionist. A nutritionist that can tell you about a diet for the brain, like the Mediterranean diet...”

Needed More Education or Support

Another theme was the feeling that the ADC program needed to provide more education or support. For example, one daughter wanted more frequent contacts from the DCS:

I think that the main thing that comes to mind now would be if they contact us regularly on the phone... even though they canť come and visit...like regularly call the patienťs family because every new change happens with them. Iťs not like that once a month or a few weeks or even a week be in touch for updates...if they could call them regularly...so it will be...the family wonť feel alone and more support and you know more you talk to them, the more education and the more support.

Poor Rapport of Dementia Expert with Family Caregivers

In one interview, a caregiver noted that she considered the DCS’ approach to be too “heavy-handed.”

So you think you got everything ok, and then somebody comes in and doesnť exactly like whaťs going on. So making suggestions needs to be made delicately, I guess. Because if you come in and say something harsh, here I am doing the best I can, I’m working full time, I’m trying to care for my mom, and someone doesnť like...the suggestions need to be gently presented. Because this journey is horrible as it is. So being gentle is the best thing.

Another caregiver felt like the counseling she received at one of the community-based organizations would have been more helpful if it was with a licensed counselor instead of a counselor-in-training, specifically citing that the counselor did not seem prepared.

Behavioral Recommendations that the Caregiver Felt Did Not Work

Non-pharmacological behavioral modifications are often taught to family caregivers as a way to manage the PLWD’s behaviors. Examples include maintaining a daily schedule, improving communication skills, and learning to redirect or reorient the PLWD. Often these strategies are used in conjunction with medication to treat behaviors, but whether they are used alone or with pharmaceutical intervention they are not always effective as one daughter described:

I do have to say they are great in theory. And in theory they make perfect sense. But come reality it is a little more challenging to implement because some of the time, say if that person is going to do that behavior, it doesnť matter what you do or how you react or donť react, how you respond or donť respond, they will do that or continue to do that. Maybe if we were to react, maybe it would make the behavior worse. But it doesnť stop the behavior in other words. In theory, if you donť react the behavior will stop. Like some of them were so cookie-cutter, I’m like ‘uh huh, you have no idea’.

Of 53 caregivers who did not have clinical benefit from the ADC program and responded to the interviews and surveys, 45 (85%) felt that being enrolled in the ADC was very beneficial to extremely beneficial. However, the 56% of caregivers who felt overwhelmed were less likely to perceive the program as being very or extremely beneficial (76% versus 100%, p=0.042).

Table 2 shows the services recommended by the ADC and how beneficial these were perceived to be by caregivers. The most commonly recommended services were educational resources (94%), safety recommendations (87%), and advance care planning (87%). Recommendations in all categories were perceived as beneficial by at least 75% of respondents except private respite services (73%) and support groups (68%). Support groups were less frequently perceived as beneficial compared to counseling (90%), and respite services were less frequently perceived as beneficial compared to adult day care (80%).

Table 2:

Caregiver Receipt and Perception of Care Recommendations (N=53).

| Variable | N (%) Receiving recommendation | N (%) perceiving recommendation as beneficial |

|---|---|---|

| Educational Resources | 50 (94%) | 47 (94%) |

| Behavioral management (non-pharmacological) | 18 (34%) | 18(100%) |

| Coordinating medical care | 16 (30%) | 15 (94%) |

| Referral to specialist | 13 (25%) | 12 (92%) |

| Adult day care | 30 (57%) | 24 (80%) |

| Counseling | 29 (55%) | 26 (90%) |

| Safety recommendation | 46 (87%) | 39 (85%) |

| Respite care / stay | 37 (70%) | 27 (73%) |

| Advance care planning | 46 (87%) | 43 (93%) |

| Support groups | 40 (75%) | 27 (68%) |

| Transportation services | 8 (15%) | 8 (100%) |

| Legal resources | 2 (4%) | 2 (100%) |

DISCUSSION

This mixed methods study attempted to identify reasons why some PLWD and their caregivers did not benefit from a comprehensive, nurse practitioner-led dementia care program. Of note, this lack of benefit was defined by scores on validated measures of PLWD behavioral symptoms and caregiver strain, distress, and depression. Despite lack of benefit on these measures, 85% of the caregivers interviewed or surveyed felt that their participation in the ADC program was beneficial suggesting there are benefits to dementia care management that are not well captured by some validated measures of caregiver strain, depression, and distress due to behavioral symptoms.

In qualitative analyses, we identified seven themes of potential reasons for lack of clinical benefit among dyads that may inform the ADC and other dementia care programs. Some recommendations, such as those for safety, support groups, and adult day care, did not seem to fit the caregivers’ perceived current needs or were deemed inappropriate for the PLWD’s stage of dementia. For example, some caregivers had already tried behavioral interventions and felt that these no longer were effective. Another theme was barriers that interfered with the caregivers’ ability to access beneficial services including location, costs, lack of respite care, and technology. Other themes related to needing more intensive support or counseling services than could be provided by the program. Finally, some caregivers never established good rapport with the dementia care team. Many issues identified in this study are addressable in theory but harder in practice due to care delivery constraints created by our current Fee-for-service payment model. For example, some caregivers wanted more individualized or additional DCS contact which would only be possible with changes to provider reimbursement to allow for services such as telephone and telemedicine visits, time to research community caregiver and PLWD services, and vouchers or other payments to CBOs for private pay services (e.g. adult day care, counseling, education).

We also found that caregivers may not respond to the program because the burden of caregiving had overwhelmed them, consistent with estimates that 59% of family caregivers that care for a PLWD describe their emotional stress of caregiving as high to very high.1 If a caregiver is too overwhelmed to obtain help in the community or to learn more about the PLWD’s disease and its progression, they may not be able to take advantage of program services or may not see the benefit of a dementia care program.

In addition to perceiving the program as being beneficial, the vast majority of caregivers perceived individual recommendations as beneficial. However, individual counseling and adult day programs were more commonly perceived as more beneficial than support groups and private respite care, respectively. More individualized and intensive services may better meet caregiver needs for personal support and time away from caregiving.

Changes made to the program over the last 7 years have addressed some of the feedback provided by the caregivers. For example, in the second year of the program, vouchers were provided on a limited basis for participants to use for services such as individual counseling, private case management, and adult daycare that are typically out-of-pocket expenses. These particular services were identified as important for certain dyads who previously could not access these due to financial constraints. Support groups focused on the needs of persons with early onset Alzheimer’s disease and other rare dementia types were formed. A one-day caregiver educational “bootcamp” with provision of respite care was developed. Future research is needed to better gauge the current dyad experience in the ADC program and determine if additional modifications are needed.

The limitations of this study are important to note. This study sought caregivers of dyads that did not benefit based on objective measures, which could only be determined after they returned for their one-year annual visit. Thus, we were unable to capture a segment of dyads who did not agree to come back for an annual visit (49%)5. Some of these dyads may not have benefited from the program and may have been able to provide additional insights. The response rate of caregivers to our survey was 36%. However, the purpose of the study was to generate ideas to improve dementia care programs rather than obtain accurate quantitative data for population estimates. In addition, the interviews and surveys were conducted after some PLWD had left the program due to death or other reasons and relied on the caregiver being able to remember their experience. The study was limited to one program that was implemented at one site. Hence, the findings may not apply to other sites or other dementia care programs.

The UCLA ADC program was created in response to the need to improve dementia care for PLWD and their family caregivers. Although three-quarters of dyads demonstrated clinical benefit at 1 year, one-quarter did not. The finding that the vast majority of non-responders rated the program as beneficial suggest that other unmeasured benefits may have been achieved by receiving dementia care management. Furthermore, individual recommendations and services were rated highly. We also noted that caregivers who felt overwhelmed were less likely to perceive benefit from the program suggesting that this group may have greater unmet needs or need novel approaches to care and services. Insights gained from this study may guide dementia care programs to refine the services provided and researchers to develop new measures to quantify benefit.

Highlights.

Caregivers perceive benefit from dementia care despite being identified as not benefiting using formal instruments.

Identified barriers to helpful dementia care may not be easily addressed due to care delivery constraints created by our current Fee-for-service payment model.

Caregivers who felt overwhelmed were less likely to perceive benefit.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21AG0546

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. Published online 2020. 10.1002/alz.12068 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.National Institute on Aging. What is Dementia? Symptoms, Types, and Diagnosis. Basics of Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. Published 2017. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-dementia-symptoms-types-and-diagnosis

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Published 2017. Accessed January 1, 2019. www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/alzheimers/what-is-alzheimers-disease

- 4.Kasper J, Freedman V, Spillman B, Wolff J. The Disproportionate Impact Of Dementia On Family And Unpaid Caregiving To Older Adults. Health Aff. 2015;34(10):1642–1649B. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reuben DB, Tan ZS, Wenger NS, Romero T, Keeler E, Jennings LA. Patient and Caregiver Benefit from a Comprehensive Dementia Care Program.; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Reuben DB, Evertson LC, Wenger NS, et al. The University of California at Los Angeles Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care Program for Comprehensive, Coordinated, Patient-Centered Care: Preliminary Data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(12):2214–2218. 10.1111/jgs.12562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nursingplus Open. 2016;2. 10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thornton M, Travis SS. Analysis of the Reliability of the Modified Caregiver Strain Index. Journals Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(2):S127–S132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mao H, Kuo C, Huang W, Cummings JL, Hwang T. Values of the minimal clinically important difference for the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire in individuals with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(7):1448–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]