Abstract

Purpose

The optimal timing for radiotherapy (RT) after incomplete transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) remains unclear. This study investigated the optimal timing to initiate RT after incomplete TACE in patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage B hepatocellular carcinoma.

Materials and Methods

This study included 116 lesions in 104 patients who were treated with RT after TACE between 2001 and 2016. The time interval between the last TACE session and RT initiation was retrospectively analyzed. The optimal cut-off time interval that maximized the difference in local failure-free rates (LFFRs) was determined using maximally selected rank statistics.

Results

The median time interval was 26 days (range: 2–165 days). At a median follow-up of 18 months (range: 3–160 months), the median overall survival was 18 months. The optimal cut-off time interval appeared to be 5 weeks; using this cut-off, 65 and 39 patients were classified into early and late RT groups, respectively. Early RT group had a significantly poorer Child-Pugh class and higher alpha-fetoprotein levels compared to late RT group. Other characteristics, including tumor size (7 cm vs. 6 cm; p=0.144), were not significantly different between the groups. The 1-year LFFR was significantly higher in the early RT group than in the late RT group (94.6% vs. 70.8%; p=0.005). On multivariate analysis, early RT was identified as an independent predictor of favorable local failure-free survival (hazard ratio: 3.30, 95% confidence interval: 1.50–7.29; p=0.003).

Conclusion

The optimal timing for administering RT after incomplete TACE is within 5 weeks. Early administration of RT is associated with better local control.

Keywords: Carcinoma, hepatocellular; chemoembolization, therapeutic; radiotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is widely used as the standard of care for the local treatment of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage B hepatocellular carcinoma (BCLC-B HCC). However, tumor cells at the periphery of HCC may remain viable, as they are supplied by both arterial and portal blood. Complete tumor necrosis may not be induced in large HCCs.1 Ischemic injury by TACE stimulates vascular endothelial growth factor production by residual tumor cells, which may induce neoangiogenesis and potentially cause disease recurrence.2 Radiotherapy (RT) has been investigated as a component of combined treatment to compensate for the limitations of TACE. Several studies, including meta-analyses and prospective trials, have reported significant therapeutic benefits of combination treatment using RT and TACE.3,4,5,6,7,8

In real-world practice, RT is frequently administered after incomplete TACE.9 However, the optimal therapeutic strategies to maximize treatment outcomes have not been well defined. In the clinical scenario, determination of the optimal timing for initiating RT is particularly important. Early administration of RT may enhance tumor control by eradicating residual tumor cells early. However, its application is limited since diffuse lipiodol retention around the tumor immediately after TACE may obscure the tumor margin, thereby hindering delineation of the RT target volume.10 Furthermore, the post-TACE acute inflammatory status of the liver with elevated liver function parameters may prevent the early initiation of RT.11 Consequently, RT is usually delayed for at least a few weeks. Therefore, it is of particular clinical importance to identify the optimal timing of RT initiation after TACE.

Therefore, in a homogeneous cohort of patients with BCLC-B HCC treated with TACE and RT, we investigated the optimal timing of RT initiation after incomplete TACE to determine optimal strategies that may maximize the clinical benefits of TACE with RT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

We retrospectively identified patients with BCLC-B HCC who underwent RT after TACE at our center between July 2001 and September 2016. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) a diagnosis of BCLC-B HCC, 2) RT administration after TACE, and 3) a <6-month interval between TACE and initiation of RT. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Child-Pugh class C, 2) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score ≥3, 3) presence of distant metastases, 4) history of other malignancies, 5) history of RT administration to the abdominal area, and 6) incomplete RT [biologically effective dose (BED) <40 Gy with α/β=10] due to patient refusal or poor general condition. A total of 116 lesions in 104 patients were included in the analysis.

Ethical statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (4-2019-0633). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board.

Treatment

TACE was performed using the conventional method. A combination of 5 mL of iodized oil contrast medium (Lipiodol; Guerbet, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France) and 30–50 mg of doxorubicin (Adriamycin; Ildong Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea) was infused selectively into a subsegmental branch of the feeding artery. If this was impossible, a segmental branch was chosen instead. Embolization was subsequently performed using gelatin sponge particles (Cutanplast; Mascia Brunelli S.p.A., Milan, Italy). Identifying TACE incompleteness and necessity of additional RT was determined individually in the multidisciplinary discussion that included intervention radiologists, radiation oncologists, and hepatologists. Patients were considered for additional RT after TACE for the following cases; progressive disease according to the modified RECIST criteria,12 or incomplete uptake of iodized oil on contrast-enhanced computed tomography. When the result of TACE was expected to be incomplete due to large size of the tumor and/or poor vascularity, the combination treatment of TACE and RT was planned from the beginning. The necessity of additional RT was determined through multidisciplinary discussion while considering the tumor and patient's condition. Repeated TACE was avoided in patients compatible to TACE refractoriness13 or when further TACE seemed technically inaccessible.

The gross tumor volume included enhanced tumor areas, complete tumor areas filled by the lipiodol-doxorubicin or lipiodol-cisplatin mixture, and tumor areas showing complete tissue necrosis after TACE on dynamic enhanced computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. The clinical target volume included the gross tumor volume with a 5-mm margin, and the planning target volume was defined as the clinical target volume with a 5-mm margin. All patients were educated on respiratory control, and an abdominal compressor was used to restrict diaphragmatic movement. Before 2010, tumor movement was accounted for in the planning target volume by adding a margin of 1–2 cm in the craniocaudal direction. However, since 2010, four-dimensional computed tomography-based planning has been adopted. The internal target volume was delineated based on the tumor movement during individual respiratory phases, and 5-mm margins around the internal and clinical target volumes were defined as the clinical and planning target volumes, respectively.

RT doses were decided according to the physicians' discretion to maximize the dose delivered to tumor while satisfying the dose constraints for normal organs, such as remnant liver and gastrointestinal tract. Various dose fractionation schedules were used: 100–60 Gy/20–30 fractions in daily >3 Gy dose, 54–36 Gy/20–30 fractions in daily <3 Gy dose. Three-dimensional conformal RT and intensity-modulated RT was used in 89 (85.6%) and 15 (14.4%) patients, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The time interval between the last session of TACE and RT initiation was evaluated. The optimal cut-off time interval that maximized the difference in the local failure-free rate (LFFR) was determined using maximally selected rank statistics.14 The LFFR, outfield intrahepatic failure-free rate, distant metastasis-free rate, and overall survival (OS) were defined as the time between the date of RT initiation and the first event, and were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. A Cox regression model was used for univariate and multivariate analyses of LFFR by backward stepwise model selection. Baseline characteristics were compared between the two groups using the chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, or Student's t-test, as appropriate. The relationship between the time interval and probability of 1-year local control was analyzed using logistic regression. Propensity score matching between the early and late RT groups was performed by using a 1:1 nearest neighbor (greedy-type) matching and a caliper width of a 0.2 standard deviation of the logit distance measure. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p-value of <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 3.4.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS software (version 23.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) packages.

RESULTS

Patient and tumor characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics before RT. All patients had BCLC-B HCC. The median age was 59 years (range: 34–83 years), and median tumor size was 7 cm (range: 2–20 cm). Of the patients, 61 (58.7%) and 43 (41.3%) had single and multiple tumors, respectively. Most patients (n=96, 92.3%) had Child-Pugh class A disease. The median number of TACE treatments before and after RT were 2 (range: 1–7) and 0 (range: 0–7), respectively. The median time interval between TACE and RT initiation was 26 days (range: 2–165 days). Among the 104 patients analyzed, the median follow-up duration was 18 months (range: 3–160 months), and the median OS was 18.0 months.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics (n=104).

| Age (yr) | 59 (34–83) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 17 (16.3) |

| Male | 87 (83.6) |

| Largest tumor size (cm) | 7 (2–20) |

| No. of tumors | |

| Single | 61 (58.7) |

| Multiple | 43 (41.3) |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 29 (1–83000) |

| PIVKA-II (mAU/mL) | 143 (11–4751) |

| No. of TACE before RT | 2 (1–7) |

| No. of TACE after RT | 0 (0–7) |

| RT dose (Gy)* | 51.5 (34–117) |

| RT technique | |

| Three-dimensional conformal | 89 (85.6) |

| Intensity-modulated | 15 (14.4) |

| Child-Pugh class | |

| A | 96 (92.3) |

| B | 8 (7.7) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 (2.7–5.1) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.2–2.6) |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.04 (0.8–1.69) |

| AST (IU/L) | 37 (15–196) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 26 (7–331) |

| ALP (IU/L) | 105 (46–431) |

| Time interval (days) | 26 (2–165) |

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; PIVKA-II, prothrombin induced by vitamin K absence-II; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; RT, radiotherapy; INR, international normalized ratio; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

Data are presented as median (range) or n (%).

*RT dose for the tumor was calculated as the equivalent dose in 2-Gy fractions with α/β=10.

Optimal cut-off time interval

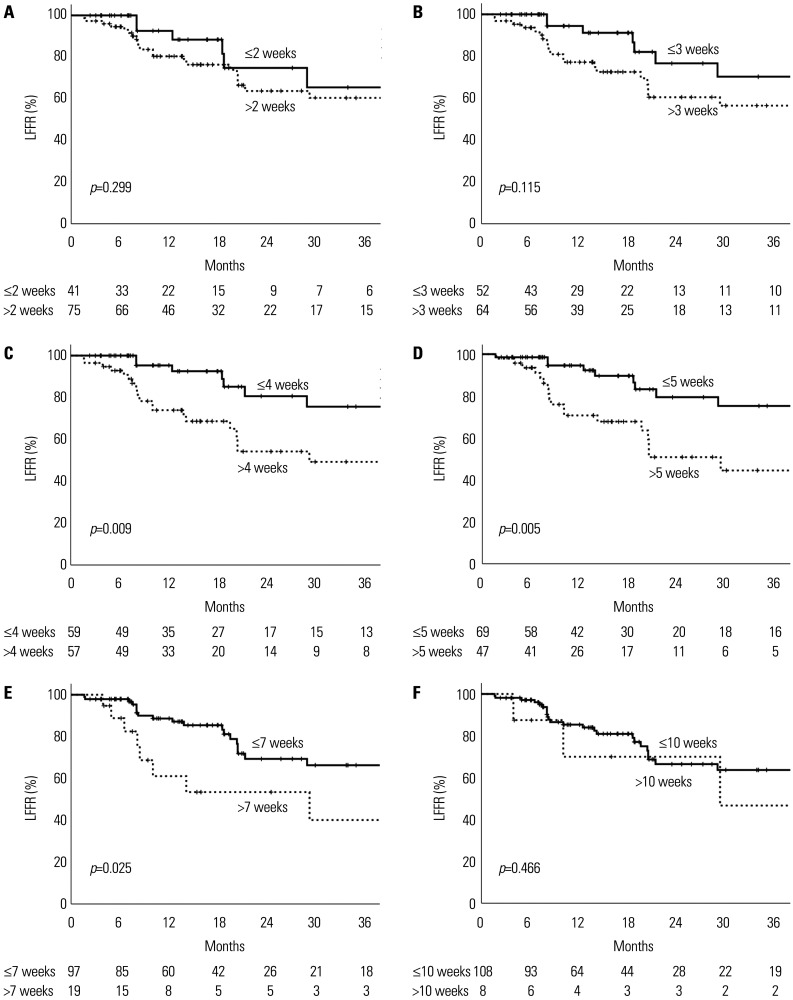

Among the 116 lesions, the probability of 1-year local control decreased with an increase in the time interval between TACE and RT initiation (Fig. 1). One-year LFFRs were analyzed in the early and late RT groups using various cut-off values (Fig. 2): within 2 weeks, the 1-year LFFRs were 92.6% and 80.4%, respectively (p=0.299); within 3 weeks, they were 94.4% and 77.2%, respectively (p=0.115); within 4 weeks, they were 95.3% and 73.9%, respectively (p=0.009); within 5 weeks, they were 94.6% and 70.8%, respectively (p=0.005); within 7 weeks, they were 88.7% and 61.1%, respectively (p=0.025); and within 10 weeks, they were 85.3% and 70.0%, respectively (p=0.466).

Fig. 1. Local control probabilities at 1 year after radiotherapy as a function of time interval. The 95% confidence intervals have been plotted around the hazard ratios.

Fig. 2. LFFRs in the early and late radiotherapy groups using a cut-off time interval of (A) 2 weeks, (B) 3 weeks, (C) 4 weeks, (D) 5 weeks, (E) 7 weeks, and (F) 10 weeks. The difference in the LFFRs was the greatest using a cut-off time interval of 5 weeks. LFFR, local failure-free rate.

The LFFR was consistently higher in the early RT group compared to the late RT group. The largest difference in LFFR was observed at the cut-off duration of 5 weeks, whereas the LFFR in the early RT group remained higher than 90% (Fig. 2D). Maximally selected rank statistics also revealed 5 weeks to be the optimal cut-off interval that maximized the difference in LFFR. Therefore, we selected 5 weeks as the optimal cut-off time interval between TACE and RT initiation.

Analyses according to early and late RT

Overall, 65 and 39 patients were included in the early RT (≤5 weeks) and late RT (>5 weeks) groups, respectively. The total numbers of lesions were 69 and 47 in the early RT and late RT groups, respectively. Table 2 shows the comparison of the characteristics of patients in the early and late RT groups. The characteristics were mostly similar, with no significant differences in age, sex, tumor size, number of tumors, prothrombin induced by vitamin K absence-II levels, number of TACE treatments before and after RT, RT dose, as well as levels of albumin, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase. In contrast, certain characteristics, such as tumor marker status and liver function, were significantly poorer in the early RT group. Specifically, the following parameters were significantly higher in the early RT group than in the late RT group: alpha-fetoprotein (median: 70 ng/mL vs. 17 ng/mL, p=0.010), international normalized ratio (median: 1.07 vs. 1.0, p=0.005), and alkaline phosphatase (median: 118 IU/L vs. 97 IU/L, p=0.037). Likewise, 8 (12.3%) patients in the early RT group had Child-Pugh class B disease, compared to 0 (0%) patient in the late RT group.

Table 2. Comparison of Patient Characteristics between Early and Late RT Groups.

| Early RT (≤ 5 weeks, n=65) | Late RT (>5 weeks, n=39) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 57 (37–83) | 62 (34–81) | 0.146 |

| Sex | 0.732 | ||

| Female | 10 (15.4) | 7 (17.9) | |

| Male | 55 (84.6) | 32 (82.1) | |

| Largest tumor size (cm) | 7 (3–20) | 6 (2–20) | 0.144 |

| No. of tumors | 0.090 | ||

| Single | 34 (52.3) | 27 (69.2) | |

| Multiple | 31 (47.7) | 12 (30.8) | |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 70 (1–83000) | 17 (1–10172) | 0.010 |

| PIVKA-II (mAU/mL) | 168 (14–2000) | 91 (11–4751) | 0.917 |

| No. of TACE before RT | 2 (1–7) | 2 (1–5) | 0.242 |

| No. of TACE after RT | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–7) | 0.466 |

| RT dose (Gy)* | 50 (34–81) | 52 (41–117) | 0.060 |

| RT technique | |||

| Three-dimensional conformal | 58 (89.2) | 31 (79.5) | 0.171 |

| Intensity-modulated | 7 (10.8) | 8 (20.5) | |

| Child-Pugh class | 0.024 | ||

| A | 57 (87.7) | 39 (100) | |

| B | 8 (12.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 (2.7–5.1) | 3.9 (3–4.8) | 0.457 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.2–2.6) | 0.7 (0.2–2.1) | 0.531 |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.07 (0.8–1.69) | 1 (0.88–1.21) | 0.005 |

| AST (IU/L) | 39 (15–196) | 32 (17–159) | 0.530 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 30 (8–331) | 24 (7–317) | 0.910 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 118 (53–431) | 97 (46–258) | 0.037 |

| Time interval (days) | 14 (2–35) | 48 (36–165) | <0.001 |

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; PIVKA-II, prothrombin induced by vitamin K absence-II; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; RT, radiotherapy; INR, international normalized ratio; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

Data are presented as median (range) or n (%).

*RT dose for the tumor was calculated as the equivalent dose in 2-Gy fractions with α/β=10.

RT initiation was individualized at referral. The reasons for RT delay were as follows: decreased general performance of patients following TACE (n=1), fever (n=1), perihepatic abscess (n=1), late detection of recurrent disease (n=3), low compliance (n=2), and high volume center-related process delays, including delays in post-TACE imaging and patient referral (n=31).

On univariate analysis, a time interval of >5 weeks was the only significant predictor of a poor LFFR. On multivariate analysis, a time interval of >5 weeks was an independent predictor of a poor LFFR (hazard ratio: 3.30, 95% confidence interval: 1.50–7.29, p=0.003) (Table 3).

Table 3. and Multivariate Analyses of Factors Influencing the Local Failure-Free Rate.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age, yr (continuous) | 1.03 (0.99–1.06) | 0.149 | ||

| Sex (male vs. female) | 1.37 (0.41–4.52) | 0.611 | ||

| Largest tumor size, cm (continuous) | 1.05 (0.97–1.14) | 0.244 | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 0.077 |

| No. of tumors (multiple vs. single) | 0.67 (0.31–1.45) | 0.304 | ||

| AFP, ng/mL (continuous) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.662 | ||

| PIVKA-II, mAU/mL (continuous) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.195 | ||

| No. of TACE before RT (continuous) | 0.91 (0.65–1.27) | 0.568 | ||

| No. of TACE after RT (continuous) | 1.12 (0.83–1.52) | 0.467 | ||

| RT dose, Gy (continuous)* | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.483 | ||

| Time interval (>5 weeks vs. ≤5 weeks) | 2.92 (1.34–6.35) | 0.007 | 3.30 (1.50–7.29) | 0.003 |

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; PIVKA-II, prothrombin induced by vitamin K absence-II; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; RT, radiotherapy; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interal.

*RT dose for the tumor was calculated as the equivalent dose in 2-Gy fractions with α/β=10.

Although the local failure rate was higher in the late RT group, the OS, outfield intrahepatic failure-free rate, and distant metastasis-free rate were not significantly different between the groups. In the early and late RT groups, the 1-year local failure rates were 5.7% and 34.6%, respectively (p=0.002); the 1-year outfield intrahepatic failure-free rates were 56.1% and 49.5%, respectively (p=0.107); the 1-year distant failure-free rates were 67.0% and 80.6%, respectively (p=0.139); and the 1-year OS rates were 63.1% and 74.4%, respectively (p=0.977) (Fig. 3), when calculated from RT start date. When calculated from the last TACE date, the 1-year local failure rates were 5.7% and 31%, respectively (p=0.005); and the 1-year OS rates were 63.1% and 79.5%, respectively (p=0.680).

Fig. 3. (A) Local failure-free rate (LFFR), (B) outfield intrahepatic failure-free rate, (C) distant failure-free rate, and (D) overall survival (OS) rate in patients with cut-off time intervals of ≤5 weeks and >5 weeks.

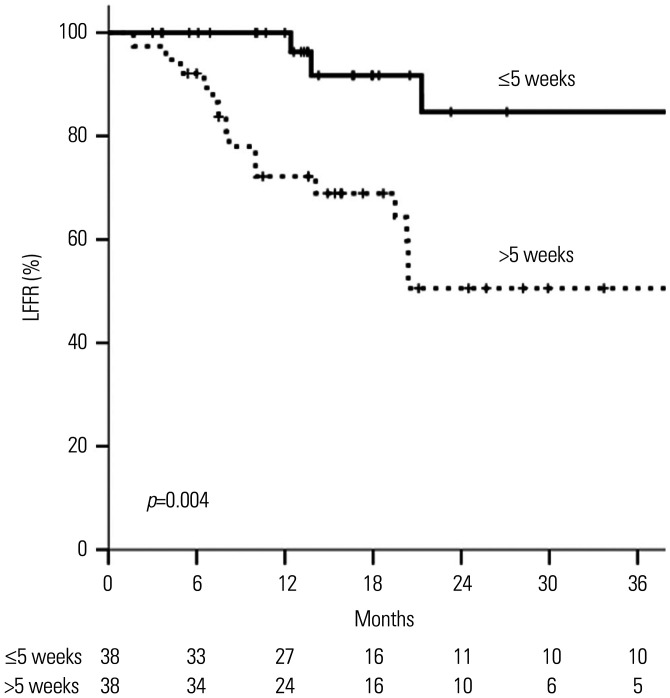

After propensity score matching, the patient and tumor characteristics were well-balanced between the early and late RT groups (Supplementary Table 1, only online). The LFFR was significantly higher in the early RT group (p=0.004) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Local failure-free rates (LFFRs) in patients with cut-off time intervals of ≤5 weeks and >5 weeks after propensity score matching.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that the likelihood of local control increases with a decrease in the time interval between TACE and RT. Based on the estimated optimal cut-off time interval of 5 weeks, patients were categorized into the early and late RT groups; patient characteristics were mostly similar between the groups. However, certain characteristics, including tumor marker status and liver function, were poorer in the early RT group than in the late RT group. Nevertheless, the early RT group had a higher LFFR than the late RT group (1-year LFFR: 94.6% vs. 70.8%; p=0.005). Moreover, early administration of RT was an independent predictor of a favorable LFFR.

Considering the increasing clinical evidence in favor of TACE with RT, the addition of RT after incomplete TACE has become increasingly popular in clinical practice.3,4,5,6,7 However, the optimal radiation dose/fractionations, radiation techniques, strategies of combining TACE with RT (RT before TACE, RT sandwiched between TACE treatments, or RT following TACE), and time interval between TACE and RT remain unclear. We previously investigated the optimal RT dose for TACE with RT treatments and concluded that a higher BED (≥72 Gy) improved local control and progression-free survival.15 In line with the previous study, we evaluated the optimal timing of RT after incomplete TACE that may maximize treatment benefits.

So far, the time interval between TACE and RT varies across literature. Our previous prospective phase II trial that investigated the efficacy and toxicity of TACE with RT adopted a time interval between 4 and 6 weeks.5 A randomized clinical trial comparing TACE with RT and sorafenib used a time interval of <3 weeks.3 Likewise, most studies have used time intervals between 2 and 8 weeks.6 However, no study has yet investigated the effect of the time interval between TACE and RT on treatment outcomes. Among our patients, the time interval varied between 2 days and 5 months, and we evaluated the effect of the time interval on treatment outcomes.

In this study, the improvement in LFFR owing to early RT may be attributed to several factors. First, in patients receiving early RT, the higher retention of chemotherapeutic agents in liver tumor cells after embolization may enhance the radiosensitizing effect. Second, early RT may eradicate residual tumor cells after TACE before regrowth of the residual tumor. Third, early initiation may allow the administration of RT before ischemic injury from TACE induces a neoangiogenic reaction. A study using blood samples from patients with HCC demonstrated that the levels of two angiogenic factors, namely, vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor, increase after TACE.16 Improved tumor control may be anticipated in patients in whom RT is administered before tumor neoangiogenesis. However, although insignificant, the distant-failure free rate was slightly lower in the early RT group than in the late RT group. This may be due to the more advanced cancer in the early RT group, as can be seen by higher AFP level.17 Early administration of RT only affected local control; however, since RT is a local therapy, it did not affect distant metastasis or outfield intrahepatic failure.

Certain clinical situations may hinder the early initiation of RT after TACE. Diffuse peritumoral retention of lipiodol is commonly observed on simulation computed tomography immediately after TACE.10 This obscures the precise tumor margin and hinders radiation oncologists from defining accurate RT target volumes. Furthermore, an elevation in liver function parameters is common immediately after TACE.11 Therefore, additional RT at this point may lead to hepatic decompensation and liver failure. Delays in decision making, imaging, RT planning, or referral processes may also delay the initiation of RT, and this was the main reason for the RT delay in this study. Therefore, we suggest that patients who could benefit from additional RT be referred and prepared for RT planning expeditiously after multidisciplinary discussion.

In our study, implementing the cut-off time interval of 2 or 3 weeks yielded no significant differences in LFFR between the early and late RT groups, implying that very early addition of RT (within 2–3 weeks) may be unnecessary. Among our patients, the transiently elevated liver function parameters after TACE usually normalized within 2–3 weeks. Therefore, we speculate that very early initiation of RT is unnecessary and may increase hepatic toxicity. RT initiation within 3–5 weeks after TACE is safe and optimal.

This study had several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study extending over a long duration; treatment policies have changed over this period, particularly in terms of RT dose prescription. However, this homogeneous cohort included patients with BCLC-B HCC who were treated with TACE and RT, thereby allowing the evaluation of the sole effect of time intervals on treatment outcomes. Second, this study revealed no significant relationship between the LFFR and RT dose. This was in contrast to the findings of our previous study, which concluded that a BED ≥72 Gy was associated with better local control.15 However, the patient group in this study was different from that in the previous study. The previous study included patients with all BCLC disease stages, whereas this study selectively included BCLC-B HCC patients, and only a small proportion of patients (n=12, 11.5%) received radiation doses exceeding a BED of 72 Gy. Nevertheless, our findings should be interpreted with caution considering these limitations.

In conclusion, this study revealed that the probability of local control may be improved by administering RT as early as 5 weeks after TACE. A multidisciplinary discussion involving interventional radiologists, radiologists, radiation oncologists, surgeons, and hepatologists may expedite the identification of cases of incomplete TACE and emphasize the necessity of additional local treatment. This will facilitate early administration of RT after incomplete TACE. Future prospective studies are needed to validate our findings.

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Jinsil Seong.

- Data curation: all authors.

- Formal analysis: Jinsil Seong and Hwa Kyung Byun.

- Funding acquisition: Jinsil Seong.

- Investigation: Jinsil Seong.

- Methodology: Jinsil Seong.

- Project administration: Jinsil Seong.

- Resources: Jinsil Seong.

- Supervision: Jinsil Seong.

- Validation: Jinsil Seong and Hwa Kyung Byun.

- Visualization: Jinsil Seong and Hwa Kyung Byun.

- Writing—original draft: Jinsil Seong and Hwa Kyung Byun.

- Writing—review & editing: Jinsil Seong and Hwa Kyung Byun.

- Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Comparison of Patient Characteristics between Early and Late RT Groups after Propensity Score Matching

References

- 1.Higuchi T, Kikuchi M, Okazaki M. Hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization. A histopathologic study of 84 resected cases. Cancer. 1994;73:2259–2267. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940501)73:9<2259::aid-cncr2820730905>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang B, Xu H, Gao ZQ, Ning HF, Sun YQ, Cao GW. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Acta Radiol. 2008;49:523–529. doi: 10.1080/02841850801958890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon SM, Ryoo BY, Lee SJ, Kim JH, Shin JH, An JH, et al. Efficacy and safety of transarterial chemoembolization plus external beam radiotherapy vs sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma with macroscopic vascular invasion: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:661–669. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huo YR, Eslick GD. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization plus radiotherapy compared with chemoembolization alone for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:756–765. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi C, Koom WS, Kim TH, Yoon SM, Kim JH, Lee HS, et al. A prospective phase 2 multicenter study for the efficacy of radiation therapy following incomplete transarterial chemoembolization in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng MB, Cui YL, Lu Y, She B, Chen Y, Guan YS, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in combination with radiotherapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shim SJ, Seong J, Han KH, Chon CY, Suh CO, Lee JT. Local radiotherapy as a complement to incomplete transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2005;25:1189–1196. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi SH, Seong J. Stereotactic body radiotherapy: does it have a role in management of hepatocellular carcinoma? Yonsei Med J. 2018;59:912–922. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2018.59.8.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi SH, Seong J. Strategic application of radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;24:114–134. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2017.0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim HS, Jeong YY, Kang HK, Kim JK, Park JG. Imaging features of hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and radiofrequency ablation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W341–W349. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan AO, Yuen MF, Hui CK, Tso WK, Lai CL. A prospective study regarding the complications of transcatheter intraarterial lipiodol chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:1747–1752. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kudo M, Matsui O, Izumi N, Kadoya M, Okusaka T, Miyayama S, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization failure/refractoriness: JSH-LCSGJ criteria 2014 update. Oncology. 2014;87 Suppl 1:22–31. doi: 10.1159/000368142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hothorn T, Lausen B. On the exact distribution of maximally selected rank statistics. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2003;43:121–137. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byun HK, Kim HJ, Im YR, Kim DY, Han KH, Seong J. Dose escalation in radiotherapy for incomplete transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2020;196:132–141. doi: 10.1007/s00066-019-01488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sergio A, Cristofori C, Cardin R, Pivetta G, Ragazzi R, Baldan A, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): the role of angiogenesis and invasiveness. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:914–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamashiki N, Seki T, Wakabayashi M, Nakagawa T, Imamura M, Tamai T, et al. Usefulness of Lens culinaris agglutinin A-reactive fraction of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP-L3) as a marker of distant metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 1999;6:1229–1232. doi: 10.3892/or.6.6.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comparison of Patient Characteristics between Early and Late RT Groups after Propensity Score Matching