Abstract

Latin America is a region with a widely variable socioeconomic landscape, facing a surge in noncommunicable diseases, including chronic kidney disease and kidney failure, exposing significant limitations in the delivery of care. Despite region-wide efforts to explore and address these limitations, much uncertainty remains as to the capacity, accessibility, and quality of kidney failure care in Latin America. Through this second iteration of the International Society of Nephrology Global Kidney Health Atlas, we aimed to report on these indicators to provide a comprehensive map of kidney failure care in the region. Survey responses were received from 18 (64.2%) countries, representing 93.8% of the total population in Latin America. The median prevalence and incidence of treated kidney failure in Latin America were 715 and 157 per million population, respectively, the latter being higher than the global median (142 per million population), with Puerto Rico, Mexico, and El Salvador experiencing much of this growing burden. In most countries, public and private systems collectively funded most aspects of kidney replacement therapy (dialysis and transplantation) care, with patients incurring at least 1% to 25% of out-of-pocket costs. In most countries, >90% of dialysis patients able to access kidney replacement therapy received hemodialysis (n = 11; 5 high income and 6 upper-middle income), and only a small minority began with peritoneal dialysis (1%–10% in 67% of countries; n = 12). Few countries had chronic kidney disease registries or targeted detection programs. There is a large variability in the availability, accessibility, and quality of kidney failure care in Latin America, which appears to be subject to individual countries’ funding structures, underreliance on cheap kidney replacement therapy, such as peritoneal dialysis, and limited chronic kidney disease surveillance and management initiatives.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, dialysis, end-stage kidney disease, kidney failure, kidney registries, kidney transplantation

Latin America, as a region, is experiencing a demographic and epidemiologic transition, with reductions in child mortality and communicable diseases, longer life expectancy, and rapid urbanization triggering a surge in lifestyle-associated noncommunicable diseases.1 In this setting, the burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and kidney failure, particularly in wealthier countries, can be traced to diabetes and hypertension. Particular to Latin America is the phenomenon of Mesoamerican nephropathy or CKD of unknown etiology, an epidemic of rapidly progressive kidney disease among young male sugarcane workers in several Central American countries; the high mortality rate is exposing health care system limitations of many countries to cope with such a public health emergency.2, 3, 4 Although reporting of patient-level kidney failure information is patchy or absent in many countries, the Latin American Dialysis and Transplant Registry has existed since 1991. Supported by the Latin American Society of Nephrology and Hypertension (original Spanish name: Sociedad Latinoamericana de Nefrologia e Hipertension), the registry collects information from 20 countries and generates valuable annual reports on the region.5 Nevertheless, much uncertainty remains as to the capacity, accessibility, and quality of kidney failure care in the region and the world at large. In this article, we leveraged data from the second iteration of the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) Global Kidney Health Atlas to report on the capacity, accessibility, and quality of kidney failure care in Latin America.6 The methods for this research are described in detail elsewhere.7

Results

Results of this study are presented in tables and figures and broadly summarized into 2 categories: desk research (Tables 18, 9, 10 and 23,11, 12, 13, Figure 1, Supplementary Table S1, and Supplementary Appendix) and survey administration (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Supplementary Figures S1–S7).

Table 1.

Health finance, service delivery, and workforce prevalence in 18 Latin American countries participating in the ISN-GKHA survey8, 9, 10

| Country | World Bank income level | Area, km2 | Total population (2018) | GDP (PPP), $ billiona |

Total health expenditures, % of GDPa |

Annual cost KRTb (US$) and out-of-pocket cost/% paid by patient from total costc |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD | PD | KT (first year) | ||||||

| Global median [IQR]d | — | — | — | — | 6.5 [4.9–8.8] | 22,617 [14,882–49,690] | 20,524 [14,305–33,905] | 25,356 [15,913–43,901] |

| Latin America median [IQR]d | — | — | — | 138.0 [85.0–447.0] | 7.0 [6.0–8.0] | 17,454 [15,737–20,207] | 16,826 [15,290–19,556] | 15,913 [13,784–16,890] |

| Argentina | Upper-middle | 2,780,400 | 44,694,198 | 922.0 | 6.8 | 15,600/0 | 18,000/0 | 21,207/0 |

| Bolivia | Lower-middle | 1,098,581 | 11,306,341 | 84.0 | 6.4 | 20,701/0 | 16,732/0 | 13,784/0 |

| Brazil | Upper-middle | 8,515,770 | 208,846,892 | 3248.0 | 8.9 | 18,724/1–25 | 24,358/1–25 | 7458/1–25 |

| British Virgin Islands | High | 1910 | 106,977 | 0.5 | — | — | — | — |

| Chile | High | 756,102 | 17,925,262 | 452.0 | 8.1 | 22,758/1–25 | 20,524/1–25 | —/1–25 |

| Colombia | Upper-middle | 1,138,910 | 48,168,996 | 712.0 | 6.2 | 16,701/0 | 16,919 | 16,890/1–25 |

| Cuba | Upper-middle | 110,860 | 11,116,396 | 137.0 | 10.9 | — | — | — |

| Dominican Republic | Upper-middle | 48,670 | 10,298,756 | 173.0 | 6.2 | —/1–25 | —/1–25 | — |

| El Salvador | Lower-middle | 21,041 | 6,187,271 | 51.0 | 6.9 | — | — | —/26–50 |

| Guatemala | Lower-middle | 108,889 | 16,581,273 | 138.0 | 5.7 | —/51–75 | —/51–75 | —/51–75 |

| Haiti | Low | 27,750 | 10,788,440 | 20.0 | 6.9 | —/>75 | — | —/100 |

| Mexico | Upper-middle | 1,964,375 | 125,959,205 | 2463.0 | 5.9 | 16,148/26–50 | 10,927/1–25 | 15,913/1–25 |

| Panama | High | 75,420 | 3,800,644 | 104.0 | 7.0 | 20,721/1–25 | 20,075/1–25 | —/1–25 |

| Paraguay | Upper-middle | 406,752 | 7,025,763 | 89.0 | 7.8 | 14,040/26–50 | 15,330/26–50 | —/>75 |

| Peru | Upper-middle | 1,285,216 | 31,331,228 | 430.0 | 5.3 | 10,673/0 | 13,870/0 | —/0 |

| Puerto Rico | High | 13,791 | 3,294,626 | 130.0 | — | —/1–25 | —/1–25 | —/1–25 |

| Uruguay | High | 176,215 | 3,369,299 | 78.0 | 9.2 | 18,207/1–25 | 15,277/1–25 | —/1–25 |

| Venezuela, RB | Upper-middle | 912,050 | 31,689,176 | 382.0 | 3.2 | —/26–50 | —/26–50 | —/51–75 |

—, Data not reported/unavailable; GDP, gross domestic product; GKHA, Global Kidney Health Atlas; HD, hemodialysis; IQR, interquartile range; ISN, International Society of Nephrology; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; KT, kidney transplant; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PPP, purchasing power parity; RB, República Bolivariana.

Estimates are in US$ 2017.

Detailed reference list on annual cost of KRT is available in the Supplementary Appendix.

Costs are in US$ 2016.

Medians and interquartile ranges are calculated for the selected countries in the ISN-GKHA survey only.

Table 2.

Kidney replacement therapy and nephrology workforce statistics in 18 Latin American countries participating in the ISN-GKHA survey3,11, 12, 13

| Country | Treated KF, pmp, 2018 |

Prevalence of long-term dialysis, pmp, 2018 |

Long-term dialysis centers, pmp |

Kidney transplantation, pmp, 2018 |

Nephrology workforce, pmp |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | Prevalence | HD | PD | Total (HD + PD) | HD | PD | Incidence | Prevalence | Centers | Nephrologists | Nephrology trainees | |

| Global median [IQR]a | 142 [106–193] | 787 [522–1047] | 310 [99–597] | 25 [2–56] | 359 [112–636] | 4.5 [1.0–10.0] | 1.3 [0.4–2.5] | 14 [5–36] | 269 [66–468] | 0.4 [0.2–0.7] | 10.0 [1.2–22.9] | 1.4 [0.3–3.7] |

| Latin America median [IQR]a | 157 [85–189] | 715 [469–1065] | 451 [293–673] | 69 [44–135] | 602 [443–771] | 4.6 [2.9–10.9] | 1.0 [0.5–1.5] | 13 [6–23] | 135 [50–242] | 0.5 [0.3–0.9] | 9.8 [8.7–19.3] | 1.4 [0.9–3.0] |

| Argentina | 161 | 976 | 673 | 45 | 718 | 11.0 | 5.0 | 30 | 258 | 1.3 | 31.3 | 3.4 |

| Bolivia | — | — | 451 | — | — | 4.0 | 0.4 | 7 | 33 | 0.9 | 9.5 | 3.2 |

| Brazil | 204 | 876 | 591 | 49 | 640 | 4.0 | 0.7 | 28 | 236 | 0.5 | 19.7 | 2.4 |

| British Virgin Islands | — | — | 1399 | 42 | 1442 | 28.0 | — | — | — | — | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Chile | 173 | 1541 | 1259 | 73 | 1332 | 13.0 | 2.1 | 21 | 209 | 0.8 | 18.1 | 1.4 |

| Colombia | 70 | 686 | 400 | 148 | 547 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 17 | 139 | 0.2 | 5.2 | 0.4 |

| Cuba | 108 | 430 | 293 | 6 | 299 | 5.0 | 0.9 | 15 | 131 | 0.8 | 38.9 | 20.6 |

| Dominican Republic | 15 | 305 | 183 | 75 | 258 | 9.0 | 0.8 | 5 | 47 | 0.4 | 15.9 | 3.4 |

| El Salvador | 217 | 776 | 297 | 380 | 677 | 5.0 | 1.1 | 6 | 99 | 0.6 | 8.7 | 1.3 |

| Guatemala | 153 | 508 | 257 | 204 | 461 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 6 | 46 | 0.2 | 4.3 | 0.8 |

| Haiti | — | — | — | — | — | 1.0 | — | — | — | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| Mexicob | 344 | 1405 | 272 | 499 | 771 | 38.0 | 19.0 | 79 | 634 | 21.0 | 8.7 | 1.2 |

| Panama | 157 | 715 | 460 | 104 | 564 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 10 | 151 | 0.5 | 9.2 | 0.9 |

| Paraguay | 59 | 331 | 271 | 10 | 281 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 6 | 50 | 0.4 | 10.0 | 1.3 |

| Peru | 70 | 590 | 486 | 56 | 542 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 5 | 48 | 0.4 | 9.3 | 0.8 |

| Puerto Rico | 419 | 2129 | 1607 | 130 | 1737 | 16.4 | 1.2 | 18 | 392 | — | 30.3 | 1.5 |

| Uruguay | 165 | 1153 | 706 | 65 | 771 | 11.0 | 2.4 | 43 | 382 | 0.9 | 53.4 | 4.4 |

| Venezuela, RB | 100 | 388 | 374 | 14 | 388 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 1 | — | 0.2 | 15.9 | 1.6 |

—, Data not reported/unavailable; GKHA, Global Kidney Health Atlas; HD, hemodialysis; IQR, interquartile range; ISN, International Society of Nephrology; KF, kidney failure; PD, peritoneal dialysis; pmp, per million population; RB, República Bolivariana.

Median and interquartile range are calculated for the selected countries in the GKHA survey only.

Data are for the province of Jalisco, Mexico (population, 8.26 million).

Figure 1.

Countries in the Latin America region that participated in the International Society of Nephrology Global Kidney Health Atlas survey.

Figure 2.

Funding structures for nondialysis chronic kidney disease (CKD) and kidney replacement therapy (KRT) care. Values represent absolute number of countries in each category, expressed as a percentage of total number of countries. HD, hemodialysis; N/A, not available; NGOs, nongovernmental organizations; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

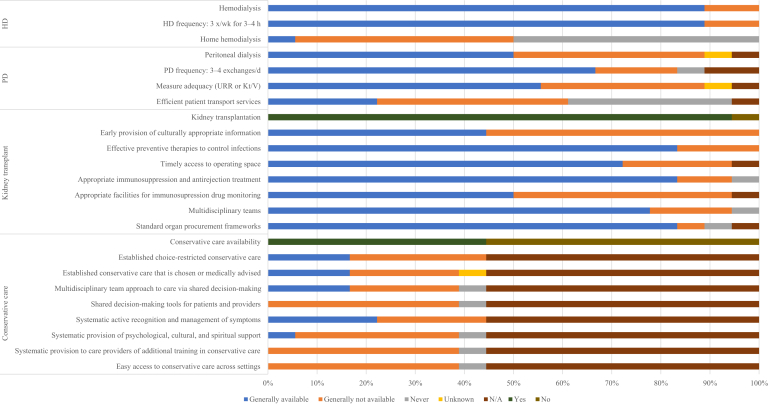

Figure 3.

Availability of choice in kidney replacement therapy or conservative care for patients with kidney failure. Values represent absolute number of countries in each category, expressed as a percentage of total number of countries. HD, hemodialysis; Kt/V, measure of dialysis adequacy; N/A, not provided; PD, peritoneal dialysis; URR, urea reduction ratio.

Figure 4.

Accessibility of kidney replacement therapy for patients with kidney failure (KF). Values represent absolute number of countries in each category, expressed as a percentage of total number of countries. N/A, not applicable; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 5.

Country-level scorecard for registries, national policies, advocacy, and barriers to optimal kidney failure (KF) care. AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; FHx, family history; HTN, hypertension; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; RB, República Bolivariana.

Setting

Latin America extends from Mexico and the Caribbean Islands in the north to the southernmost point shared by Argentina and Chile and covers an area of 20.425 million square kilometers, approximately 13% of the Earth’s land surface.14 It includes 13 dependencies and 20 countries with a growing population of 641 million people, more than half of which is concentrated in Mexico and Brazil. Latin Americans form a richly diverse, ethnic and cultural group of Spanish-, Portuguese-, and French-speaking people of predominantly European ancestry mixed with indigenous and African roots.

Since the turn of the century, the region has experienced considerable economic growth, as evidenced by an increase in the gross national income per capita of 4044 US$ in 1999 to 8700 US$ in 2018 and a total regional gross domestic product of 5.7 trillion US$.15 In line with this, average life expectancy at birth has steadily increased to 75 years, as has the adult literacy rate, which is now up to 93%.15 Despite these positive regional indicators, political turmoil and social unrest, common to much of this region and its history, have created a state of severe socioeconomic polarization and inequality both within and between countries. In 2018, 29.6% of the population of Latin America lived below the poverty line, whereas 10.2% or 63 million people lived in extreme poverty, a figure that has been steadily increasing since 2002.16 A ranking of countries according to their Gini index, a measure of the extent to which income distribution among individuals in a country deviates from a perfectly equal distribution, reveals that 13 of the top 30 countries with highest income inequality in the world are in Latin America.17 The Human Development Index, a composite of a country’s life expectancy, education index, and gross national income per capita, reflects the wide variation in quality of life of people between countries, with Chile scoring 0.843 (of a perfect score of 1) and Haiti scoring 0.498.18

A brief on what is known already on the current state of kidney care in the region

The latest report from the Latin American Dialysis and Transplant Registry highlights a growing incidence and prevalence of treated kidney failure, mostly dependent on hemodialysis (HD) with a slow but insufficient increase in the rate of transplantation and little growth in the use of peritoneal dialysis (PD). Large interregional variations have been observed in the degree of workforce capacity, training, and resources, including patient-level registries, dedicated to kidney failure care as well as the extent of funding coverage available for these therapies.19

Characteristics of participating countries

Thirty-nine respondents, representing 18 of the 28 (64.2%) countries in the ISN’s Latin America region, completed the online questionnaire (Figure 1). Most respondents were nephrologists (n = 33 [85%]), followed by nonnephrologist physicians (n = 3 [8%]) and policy makers (n = 2 [5%]), with a response rate of 50.7%. Participating countries jointly represented a population of 592.4 million (93.8% of the total population in Latin America). Half of all participating countries were upper-middle income (n = 9); responses also were submitted by high-income (n = 5), lower-middle income (n = 3), and low-income (n = 1) countries, an income level distribution representative of the entire ISN region and similar to the 11 nonparticipating countries (1 high-income, 8 upper-middle income, and 2 lower-middle income countries). As a proportion of gross domestic product, health expenditures in participating countries ranged from 10.9% in Cuba to 3.2% in Venezuela (Table 1).8, 9, 10

Burden of CKD and kidney failure in Latin America

The average prevalence of CKD in Latin America was 9.9% (95% confidence interval, 8.75%–11.1%), ranging from 6.3% in Haiti (low-income country) to 15.4% in Puerto Rico (high-income country).20 The highest proportions of deaths and disability-adjusted life years attributed to CKD were found in high-income and lower-middle income countries, including Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala (Supplementary Table S1).9,10

Data on the prevalence of kidney failure in Latin America were available for all participating countries, with the exception of Haiti, and only partially for Bolivia and British Virgin Islands. The median prevalence of treated kidney failure in Latin America was 715 per million population (pmp) (interquartile range [IQR], 469–1065 pmp), just below the global median of 787 pmp, with a higher prevalence observed in high-income and upper-middle income countries (n = 4 [22.2%]; prevalence >1100 pmp) (Table 2).3,11, 12, 13 The median number of new cases of treated kidney failure in the region (157 pmp; IQR, 85–189 pmp) was higher than the global median (142 pmp), with Puerto Rico, Mexico, and El Salvador experiencing much of this growing burden (419, 344, and 217 pmp, respectively). In most countries (n = 11; 5 high-income and 6 upper-middle income countries), >90% of dialysis patients receive HD (Table 2).3,11, 12, 13 PD was the predominant form of dialysis in Mexico and El Salvador (64% and 56% of total dialysis patients, respectively) and accounted for a significant proportion of dialysis treatment in Guatemala, Colombia, and Dominican Republic (44%, 27%, and 29%, respectively). Patients living with a functioning graft represented between a third and just under half of all treated kidney failure patients in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Mexico (26%, 27%, 33%, and 45%, respectively) but <10% in Guatemala and Peru. Transplants in higher-income countries were mainly from deceased donors, with the exception of Mexico, which performed the highest number of living donor transplants in the region, whereas lower-income countries relied almost entirely on living donors (Table 2).3,11, 12, 13

Health finance and service delivery

In most countries, public and private systems collectively funded nondialysis CKD and most aspects of kidney replacement therapy (KRT) care, with the exception of post-transplant immunosuppressive medications, which were covered more often by public funding (41% public and free at point of delivery) (Figure 2). This represented a significant difference from the globally dominant structure of public funding for KRT: services were free at the point of delivery in 43% of countries around the world (vs. only 22% of countries in Latin America). Among the 18 participating countries, 10 (55%) had data available for the annual cost of dialysis. In the region, median annual costs (in US$) per person for maintenance HD ($17,454; IQR, $15,737–$20,207) and maintenance PD ($16,825; IQR, $15,290–$19,556) were below global averages ($22,617 and $20,524, respectively) (Table 1).8, 9, 10 Data on the annual cost of kidney transplantation in the first year were available in 5 countries; costs ranged from $7458 in Brazil to $21,207 in Argentina. Out-of-pocket costs (percentage of total costs paid by the patient) for KRT were at least 1% to 25% in most countries; proportions were higher for transplantation services and in lower-income countries, with the exceptions of Argentina, Bolivia, and Peru, where patients with kidney failure incurred no costs (Table 1).8, 9, 10

Health workforce for nephrology care

Mirroring the global trend, nephrologists were primarily responsible for kidney failure care in Latin America (n = 18 [100%]), with varying support from multidisciplinary teams (n = 5 [28%]) and primary care physicians (n = 4 [22%]). The median number of nephrologists (9.8 pmp; IQR, 8.7–19.3 pmp) and the median number of nephrology trainees (1.4 pmp; IQR, 0.9–3 pmp) in Latin America were similar to median numbers worldwide (9.95 and 1.4 pmp, respectively) (Table 2).3,11, 12, 13 Overall, the number of nephrologists was higher in high-income countries, such that 4 countries (Argentina, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Uruguay) had >30 nephrologists pmp, whereas Haiti, Guatemala, and El Salvador had <9 nephrologists pmp. The most commonly reported workforce shortages were for nephrologists (72%; n = 13), surgeons and interventional radiologists for HD access (72% and 83%, respectively), and transplant surgeons (72%) (Supplementary Figure S1). Lower-income countries had workforce shortages of significantly more of the 14 types of care providers (median, 9.5) than high-income and upper-middle income countries (median, 7) (Supplementary Figure S1).

Essential medications and health product access for kidney failure care

All but 2 countries, Argentina and El Salvador, reported that long-term HD was generally available to patients in a thrice-weekly, 3- to 4-hour treatment format (Figure 3). The median number of HD centers was 4.55 pmp (n = 18; IQR, 3.0–10.9 pmp), with the highest densities in the British Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico (27.93 and 16.39 pmp, respectively) and the lowest in Haiti and Guatemala (0.65 and 0.90 pmp, respectively) (Table 2).3,11, 12, 13 Home HD was rare in the region, with only Puerto Rico reporting general availability to patients. In two-thirds of countries (n = 12), >50% of HD patients began treatment with a temporary dialysis catheter, and in 5 of these (British Virgin Islands, Haiti, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela), this proportion was >75% (Supplementary Figure S2). As observed globally, fewer patients in lower-income countries, such as Haiti, Guatemala, and El Salvador, began dialysis with a functioning vascular access (fistula or graft) or tunneled catheter. The median number of PD centers in the region was 0.96 pmp (n = 16; IQR, 0.5–1.5 pmp), which was below the global average; Guatemala, Colombia, and Paraguay had the lowest PD capacity (Table 2).3,11, 12, 13 Twelve countries (67%) were able to offer adequate frequency of exchanges (3–4 manual exchanges per day or equivalent cycles on automated PD), whereas just over half (n = 10 [56%]) had the capacity to measure PD adequacy (via measurement of urea reduction ratio or measurement of dialysis adequacy), and only 4 countries (22%) had efficient patient transport services available (Figure 3).

Kidney transplantation was available across most of the region (n = 17 [94%]), with a regional median of 0.5 transplant centers pmp (n = 16; IQR, 0.3–0.9 pmp), just above the global median of 0.42 pmp (IQR, 0.20–0.72 pmp). Mexico and Argentina had the highest capacity for transplantation (1.36 and 1.28 transplant centers pmp, respectively), whereas Haiti had the lowest (0 pmp) (Table 2).3,11, 12, 13 All countries with transplant capacity performed a combination of deceased and living donor kidney transplants, with the exceptions of Haiti and El Salvador, which had capacity for living donor kidney transplants only. Most countries with kidney transplantation available had national transplant waitlists (63%; n = 10), whereas the rest had regional lists only. Less than half of all countries were able to provide early and culturally appropriate information about transplantation to patients (44%; n = 8) (Figure 3).

In all but one surveyed country (Haiti), at least half of all patients with kidney failure were able to access dialysis, a proportion that varied because of regional capacity more than individual patient characteristics (Figure 4). Among those able to access dialysis, only a small minority began with PD (1%–10% in 67% of countries; n = 12), with Mexico and El Salvador being the exceptions; this proportion was affected by patient characteristics and regional capacity in two-thirds of countries. Patients had better access to transplantation services than to PD, with Argentina, Bolivia, and Puerto Rico reporting that >50% of eligible patients were able to access transplantation services.

Conservative care was available in less than half of all countries (n = 8; 44%) in Latin America, and only 3 countries—Argentina, British Virgin Islands, and Paraguay—were able to provide it when medically advised or chosen by the patient (Figure 3). Among those countries able to offer this service, few (17%; n = 3) took a multidisciplinary approach to care via shared decision making, no country had readily available decision-making tools for patients and providers, and only 4 countries (Argentina, the British Virgin Islands, Cuba, and Haiti) had the capacity to systematically and actively recognize and manage symptoms. Psychological, cultural, and spiritual support was only available in Panama, and no country had the resources to systematically train health care providers in conservative care.

Reporting of KRT quality indicators

All countries were able to provide information about the adequacy of HD, but only 16 countries were able to provide the same information for PD and transplantation. The least-reported indicator of dialysis adequacy was patient-reported outcome measures, with almost one-third of countries reporting that this information was collected by <10% of centers (Supplementary Figure S3). Small solute clearance and bone mineral markers in HD patients were also less commonly measured by centers, as were delayed graft function and rejection rates in transplant recipients.

Health information systems, statistics, and national health policy

Most countries in Latin America had official dialysis and transplantation registries (n = 14 [77.8%] and n = 13 [72.2%], respectively), few had CKD registries (n = 5 [27.8%]), and only the British Virgin Islands had an acute kidney injury (AKI) registry (Figure 5). El Salvador, Haiti, and Peru had no registries at all, and Mexico only had a registry for the state of Jalisco. In general, participation in registries was mandatory, with the main exception being the dialysis registries of Brazil, Paraguay, and Venezuela and the CKD registries of Argentina and Uruguay, where provider participation was voluntary. Most registries had national coverage and collected general information on the etiology of kidney disease, dialysis modality, or transplant source; patient outcome measures, such as hospitalizations, quality of life, and mortality, were more consistently collected in dialysis registries (64%, 50%, and 86%, respectively) than in transplantation registries (31%, 23%, and 69%, respectively) (Supplementary Figure S4).

Routine testing for kidney disease was available to all patients with diabetes and hypertension in the region, but less frequently to long-term users of nephrotoxic medications, high-risk ethnic groups (despite 44% of countries identifying ethnic groups as being at high risk for CKD), or patients with a family history of kidney disease (Figure 5). Only 6 countries (Bolivia being the only lower-middle income country among them) had a CKD detection program, and no country had an AKI detection program. CKD screening was generally reactive, with the exceptions of Cuba, Chile, Puerto Rico, and Uruguay, which had active screening measures in place. Services to diagnose and treat complications of kidney failure were reported as generally available in most cases (Supplementary Figure S5).

Most countries (77%; n = 14) had national strategies to improve care for CKD patients; these may have been CKD-specific strategies or incorporated into noncommunicable disease strategies, the former being more inclusive of all patients with kidney disease than the latter (Supplementary Figures S6 and S7). National CKD-specific policies were available in 7 countries (39%), all of which were high-income or upper-middle income countries, except Bolivia. Recognition of kidney disease as a health priority at the government level was more common for CKD, followed by kidney failure and AKI (67%, 44%, and 11% of countries, respectively). The existence of advocacy groups in each domain followed a similar pattern. The most commonly cited barrier to optimal kidney failure care was the individual patient, followed by nephrologists, geographic characteristics, and the health care system (83%, 78%, 78%, and 72% of countries, respectively) (Figure 5).

Discussion

Our study brings to light several important aspects of kidney failure care in Latin America. The prevalence of treated kidney failure varied throughout the region, likely reflecting inequalities in the accessibility and affordability of KRT, as well as differences in the capacity to detect and manage CKD. Workforce and resource capacities to deliver kidney failure care vary dramatically across the region, as did the prevalence of CKD detection and management programs aimed at preventing the disease. PD remained an underutilized form of dialysis, especially in geographically large countries and countries with limited health budgets. Finally, there was a lack of official registries, advocacy groups, and targeted CKD detection programs in lower-income countries, such as El Salvador, Guatemala, and Haiti.

The fate of a patient with kidney failure in Montevideo may be drastically different than that of a patient in rural Guatemala. For many years, the Latin American Dialysis and Transplant Registry has highlighted wide variability in the prevalence of treated kidney failure in Latin America, with statistics from high-income countries increasingly resembling those of developed nations while those from low-income countries remain stagnant. In 2013, the Pan American Health Organization responded by setting a target goal of 700 treated kidney failure patients pmp by 2019 in 25 Latin American countries.21,22 Although it may be tempting to think that kidney disease is less prevalent in lower-income countries, evidence from our literature review shows otherwise, revealing increased morbidity and mortality among patients in countries like El Salvador and Guatemala.

Therefore, the question is not one of relative disease prevalence, but of differential access to treatment. Compared with the rest of the world, Latin American countries tended to fund most aspects of kidney failure care with a mix of public and private systems, which may have led to large differences in the extent to which KRT funding was consistent and universal both between and within countries, especially those with greater socioeconomic inequality. Although the optimal funding structure for kidney failure care is the subject of much debate,23 our findings suggest that countries with a larger proportion of government-funded coverage (e.g., Brazil) tended to have more robust and affordable KRT programs, whereas poorer countries with fragmented health care services that relied more heavily on private sources struggled to provide universal coverage, meaning citizens paid high out-of-pocket costs for treatment.24 Costa Rica, a country where every citizen has a constitutional right to receive KRT, had the most successful transplantation program in the region, with over half of all dialysis patients receiving transplants.25 Differences in funding structures and out-of-pocket costs may also explain the large variations in access to dialysis and the proportion of patients initiating PD or receiving transplants associated with geographic and patient characteristics reported in the region.

Although the funding structure for kidney failure care and the underlying willingness of governments to support it appear to play a significant role in its accessibility and prevalence, consideration should also be given to providing cheaper forms of KRT that can meet local needs. For example, it would not be reasonable to suggest that countries with limited health budgets allocate a large proportion of funding to expensive KRT modalities, such as HD for every citizen, particularly considering the increasing life expectancy in the region and the vast geographic coverage of many Latin American countries.1 PD has been shown to be a highly cost-effective form of KRT in resource-limited countries, while also being associated with better preservation of residual kidney function, greater patient satisfaction, and greater suitability for patients living in rural and remote areas.26, 27, 28, 29

In this context, our findings that PD was only generally available in half of the surveyed countries, the median prevalence of PD centers was lower than the global median, and a minority of dialysis patients began treatment with PD suggest that this dialysis modality is a highly underutilized resource in the Latin American region, especially in lower-income countries (e.g., Bolivia) and geographically large countries (e.g., Brazil and Argentina).3,12 The disproportionate expansion of HD compared with PD in Latin America has been described several times in the past, with common barriers being a shortage of trained staff and lack of financial support and health policies.21 Nevertheless, several countries have successfully overcome barriers and implemented PD programs, including Mexico (where most PD care is delivered by internists), Guatemala (where PD is universally available and costs are fully reimbursed), and Colombia (where most PD catheter insertions are performed by nephrologists instead of surgeons).30

Another important finding in this region is the large heterogeneity in workforce capacity (both nephrologists and trainees) between low-income and high-income countries. Although no global recommendation exists for the optimal density of nephrologists, the fact that they are generally responsible for most aspects of kidney failure care (as is the case in Latin America) highlights the importance of having an adequate number of training centers and sufficient workforce capacity and distribution to coordinate care. To reach the Pan American Health Organization target goal by 2019, it was estimated that countries in Latin America should have at least 20 nephrologists pmp,3,22 a goal that is almost beyond reach for a country like Haiti, whereas Uruguay and Cuba have surpassed it twice over. Several explanations have been proposed to explain this imbalance, including a lack of training centers in low-income countries, inequities in the resources allocated to train kidney health professionals by individual countries, and a desire among skilled professionals to migrate overseas.31

These factors not only play a role in the variable prevalence of treated kidney failure, but may also explain some of the gaps we found in the existence and quality of CKD detection programs and kidney registries reported by lower-income countries. Although greater funding for specialist capacity is important, establishing collaborations between countries to share knowledge and expertise and helping to develop comprehensive and accurate kidney failure registries are crucial to bridging these gaps.32 Important to the success and sustainability of such registries is their leadership by a multidisciplinary group composed of representatives from scientific societies, the Ministry of Health, and key financial institutions. To this end, the Pan American Health Organization and Latin American Society of Nephrology and Hypertension have been leading training and certification courses to establish kidney failure registries throughout Latin America.5 As an example of regional collaboration, in 2012, the Ministries of Health of Uruguay and Bolivia, with support from Latin American Society of Nephrology and Hypertension and funding from the Uruguayan International Cooperation Agency, agreed to develop a collaborative project to prevent and manage all stages of CKD in Bolivia.33 Some of the key aspects and objectives of this collaboration were to promote kidney health care in the primary care setting, train staff to recognize and test for kidney disease in high-risk populations, and develop a national kidney failure registry and a comprehensive PD program. Similarly, the Sharing Expertise in Establishing Renal Registries project, an ISN initiative to help develop kidney registries, has partnered with Latin American Society of Nephrology and Hypertension and the Latin American Dialysis and Transplant Registry to help develop registries in low-income countries and improve their quality and sustainability.34 Ultimately, programs and partnerships that foster solidarity and resourcefulness are vital to a region rife with socioeconomic inequities.

Alongside robust kidney registries, detection of AKI and early forms of CKD in the primary care setting is key to leveling the variability in kidney failure prevalence and the resulting demand in specialized kidney services observed in the region. The original cross-sectional descriptive study associated with the ISN’s 0by25 initiative (which has a target of zero preventable deaths from AKI by 2025 in low-income and middle-income countries) revealed that a patient from Latin America with an episode of AKI was 4.14 times more likely to die from it than patients from any other region of the world.35 Accordingly, one of the pilot feasibility projects implemented at a site in Bolivia consisted of capacity building and training in the primary care setting coupled with point-of-care assessment and teleconsultation to improve detection and management of AKI in low resource areas. Timely identification of patients at risk of kidney injury or with early forms of CKD should allow simple, cost-effective interventions to prevent or slow down disease progression and avoid the prohibitive costs associated with kidney failure therapies.

In conclusion, Latin America is a region with a high burden of kidney disease and variable capacity to deal with it. Fragmented funding structures and workforce shortages, coupled with unaffordable costs to patients and underutilization of cost-effective dialysis therapies, result in variable capacity to care for kidney failure patients, who are largely subject to each country’s socioeconomic landscape. Regional and international collaborations and partnerships have been successfully established to overcome these barriers to universal and quality health care for kidney failure and should remain a priority for local governments and the wider nephrology community.

Disclosure

VJ reports grants from GlaxoSmithKline and Baxter Healthcare, provides scientific leadership to George Clinical, and receives consultancy fees for Biocon, Zudis Cadilla, and NephroPlus, all paid to his institution, outside the submitted work. RP-F reports grants from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care and personal fees from Astra Zeneca and AKEBIA, outside the submitted work. DWJ reports grants and personal fees from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care, travel sponsorship from Amgen, personal fees from Astra Zeneca, AWAK, and Ono, and grants from National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, outside the submitted work. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This article is published as part of a supplement supported by the International Society of Nephrology (ISN; grant RES0033080 to the University of Alberta).

The ISN provided administrative support for the design and implementation of the study and data collection activities. The authors were responsible for data management, analysis, and interpretation, as well as manuscript preparation, review, and approval, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

We thank Kara Stephenson Gehman in International Society of Nephrology Global Kidney Health Atlas (ISN-GKHA) for carefully editing the English text of a draft of this article. We thank Jo-Ann Donner, coordinator at the ISN, for her prominent role and leadership in the manuscript management, editorial reviews, and submission process to Kidney International Supplements; Sandrine Damster, senior research project manager at the ISN, and Alberta Kidney Disease Network staff (Ghenette Houston, Sue Szigety, and Sophanny Tiv) for helping to organize and conduct the survey and for providing project management support. We also thank the ISN headquarters staff, including the Executive Director, Charu Malik, and the Advocacy team. We also appreciate the support from the ISN’s Executive Committee, regional leadership, and Affiliated Society leaders at the regional and country levels for their help with the ISN-GKHA survey.

Footnotes

Table S1. Burden of chronic kidney disease and its risk factors in 18 Latin American countries that participated in the ISN-GKHA survey.

Figure S1. Shortage in kidney failure providers identified by the 18 Latin American countries that participated in the ISN-GKHA survey.

Figure S2. Proportion of patients starting dialysis with different forms of vascular access and adequate education.

Figure S3. Quality indicators monitored and reported by countries that participated in the ISN-GKHA survey.

Figure S4. Registry characteristics for countries that have reported having ≥1 in the ISN-GKHA survey.

Figure S5. Availability of services to diagnose and treat complications of kidney failure.

Figure S6. National strategies available in countries.

Figure S7. Population covered under national noncommunicable disease and chronic kidney disease strategies.

Supplementary Appendix. Reference list for annual cost of kidney replacement therapy (for Table 1).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.González-Bedat M.C., Diez G.J.R., Cusumano A.M. End-stage renal disease in Latin America. In: García-García G., Agodoa L.Y., Norris K.C., editors. Chronic Kidney Disease in Disadvantaged Populations. Elsevier; London, UK: 2017. pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ordunez P., Saenz C., Martinez R. The epidemic of chronic kidney disease in Central America. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e440–e441. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70217-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cusumano A.M., Rosa-Diez G.J., Gonzalez-Bedat M.C. Latin American Dialysis and Transplant Registry: experience and contributions to end-stage renal disease epidemiology. World J Nephrol. 2016;5:389–397. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v5.i5.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ordunez P., Martinez R., Reveiz L. Chronic kidney disease epidemic in Central America: urgent public health action is needed amid causal uncertainty. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.González-Bedat M.C., Rosa-Diez G.J., Fernández-Cean J.M. National kidney dialysis and transplant registries in Latin America: how to implement and improve them. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2015;38:254–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bello A., Levin A., Lunney M. Current status of end-stage kidney disease care in world countries and regions-an international survey. BMJ. 2019;367:l5873. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bello A.K., Okpechi I.G., Jha V. Understanding distribution and variability in care organization and services for the management of kidney care across world regions. Kidney Int Suppl. 2021;11 e4–e10. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Central Intelligence Agency The world factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/ Available at: Published 2019. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- 9.World Health Organization The global health observatory. https://www.who.int/gho/en/ Available at:

- 10.World Bank GDP ranking. June 2019. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/gdp-ranking Available at:

- 11.ERA-EDTA Registry ERA-EDTA Registry annual report 2017. https://www.era-edta.org/en/registry/publications/annual-reports/ Available at:

- 12.Jain A.K., Blake P., Cordy P., Garg A.X. Global trends in rates of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:533–544. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United States Renal Data System . National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2018. 2018 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Bank Surface area (sq km) - Latin America & Caribbean. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.SRF.TOTL.K2?locations=ZJ Available at:

- 15.World Bank Latin America & Caribbean. https://data.worldbank.org/region/latin-america-and-caribbean Available at:

- 16.Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Social panorama of Latin America. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/44396/4/S1900050_en.pdf Available at:

- 17.World Bank GINI index (World Bank estimate) - Latin America & Caribbean. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=ZJ Available at:

- 18.United Nations Development Programme Human development data (1990 - 2017) http://www.hdr.undp.org/en/data Available at:

- 19.Sociedad Latinoamericana de Nefrologia e Hipertension (SLANH) Reporte 2018. https://slanh.net/reporte-2018/ Available at:

- 20.Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Global Burden of Disease study. http://www.healthdata.org/gbd Available at:

- 21.Gonzalez-Bedat M., Rosa-Diez G., Pecoits-Filho R. Burden of disease: prevalence and incidence of ESRD in Latin America. Clin Nephrol. 2015;83(suppl 1):3–6. doi: 10.5414/cnp83s003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan American Health Organization Strategic plan of the Pan American Health Organization 2014-2019. https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/7654/CD53-OD345-e.pdf?sequence=16&isAllowed=y Available at:

- 23.White S.L., Chadban S.J., Jan S. How can we achieve global equity in provision of renal replacement therapy? Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:229–237. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.041715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zatz R., Romao J.E., Jr., Noronha I.L. Nephrology in Latin America, with special emphasis on Brazil. Kidney Int. 2003;83:S131–S134. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.28.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cerdas M. Chronic kidney disease in Costa Rica. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;(97):S31–S33. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juergensen E., Wuerth D., Finkelstein S.H. Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: patients' assessment of their satisfaction with therapy and the impact of the therapy on their lives. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1191–1196. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01220406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang Y.-T., Hwang J.-S., Hung S.-Y. Cost-effectiveness of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: a national cohort study with 14 years follow-up and matched for comorbidities and propensity score. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30266. doi: 10.1038/srep30266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teerawattananon Y., Luz A., Pilasant S. How to meet the demand for good quality renal dialysis as part of universal health coverage in resource-limited settings? Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:21. doi: 10.1186/s12961-016-0090-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansen M.A.M., Hart A.A.M., Korevaar J.C. Predictors of the rate of decline of residual renal function in incident dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1046–1053. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pecoits-Filho R., Abensur H., Cueto-Manzano A.M. Overview of peritoneal dialysis in Latin America. Perit Dial Int. 2007;27:316–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pecoits-Filho R., Rosa-Diez G., Gonzalez-Bedat M. Renal replacement therapy in CKD: an update from the Latin American Registry of Dialysis and Transplantation. J Bras Nefrol. 2015;37:9–13. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20150002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cusumano A.M., Gonzalez Bedat M.C. Chronic kidney disease in Latin America: time to improve screening and detection. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:594–600. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03420807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sola L., Plata-Cornejo R., Fernandez-Cean J. Latin American special project: kidney health cooperation project between Uruguay and Bolivia. Clin Nephrol. 2015;83(suppl 1):21–23. doi: 10.5414/cnp83s021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pecoits-Filho R., Sola L., Correa-Rotter R. Kidney disease in Latin America: current status, challenges, and the role of the ISN in the development of nephrology in the region. Kidney Int. 2018;94:1069–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehta R.L., Burdmann E.A., Cerda J. Recognition and management of acute kidney injury in the International Society of Nephrology 0by25 Global Snapshot: a multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2016;387:2017–2025. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.