Abstract

Once daily tenofovir/emtricitabine when used for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is effective in preventing HIV acquisition but requires consistent medication adherence. The use of ingestible technologies to monitor PrEP adherence can assist in understanding the impact of behavioral interventions. Digital pill systems (DPS) utilize an ingestible radiofrequency emitter integrated onto a gelatin capsule, which permits direct, real-time measurement of medication adherence. DPS monitoring may lead to discovery of nascent episodes of PrEP nonadherence and allow delivery of interventions that prevent the onset of sustained nonadherence. Yet, the acceptance and potential use of DPS in high-risk men who have sex with men (MSM; i.e., those who engage in condomless sex and use substances) is unknown. In this investigation, we conducted individual, semi-structured qualitative interviews with 30 MSM with self-reported non-alcohol substance use to understand their responses to the DPS, willingness and perceived barriers to its use, and their perceptions of its potential utility. We also sought to describe how MSM would potentially interact with a messaging system integrated into the DPS. We identified major themes around improved confidence of PrEP adherence patterns, safety of ingestible radiofrequency sensors, and design optimization of the DPS. They also expressed willingness to interact with messaging contingent on DPS recorded ingestion patterns. These data demonstrate that MSM who use substances find the DPS to be an acceptable method to measure and record PrEP adherence.

Keywords: HIV prevention, technology, PrEP, digital pill system, ingestible sensors

Introduction

Once-daily tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada™) for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is up to 99% effective in preventing acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) when taken every day as prescribed, but its effectiveness is directly linked to medication adherence, which can be challenging (1,2). In studies evaluating PrEP adherence in high risk populations, including men who have sex with men (MSM), tenofovir levels in participants’ plasma have demonstrated only 28% to 84% adherence to once-daily PrEP (3–8). In the multinational Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Initiative (iPrEx) study, PrEP adherence by drug detection was 51% in MSM and overall efficacy for HIV prevention was 44% versus placebo (1,9). Real-world clinical implementation of PrEP has been equivocal; some studies have documented suboptimal adherence, while others have outperformed the original iPrEx study (10). Near-continuous adherence in some studies may also reflect a high degree of motivation among individuals who self-select into research. Such studies have underscored the importance of identifying novel, accurate methods to measure PrEP adherence.

In order to measure and respond to PrEP nonadherence, many techniques have been developed, including user self-report, pill counts, pharmacy refills, electronic adherence monitors (EAMs), and pharmacologic measurement, including detection of drug concentrations in hair, plasma, urine, and erythrocytes (11,12). While there are advantages and disadvantages of using each adherence measure(11–17), there continues to be controversy around which tools will be most acceptable in the context of PrEP adherence monitoring. In contrast to adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), for example, the need for complete PrEP adherence may not be constant; indeed, the concept of prevention-effective adherence refers to the use of PrEP only in contextual situations where high-risk activities may occur, such that an individual is protected against HIV acquisition, and not during periods of low risk exposure (18). There is therefore a critical need to develop adherence tools that both measure and contextualize PrEP use.

Digital pill systems (DPS) are a novel direct and objective measure of real-time adherence to PrEP, which afford an opportunity to understand the context in which PrEP is used (19). DPS are comprised of three parts: (1) a radiofrequency identification (RFID)-tagged gelatin capsule, (2) a wearable reader device, and (3) a cloud-based server driving a collaborative interface (14). The RFID-tagged gelatin capsule, which encapsulates the oral medication in use, dissolves in the gastric acid after ingestion, releasing the medication and triggering a signal from the RFID tag. This signal is detected by the wearable reader, which then wirelessly relays a time-stamped message, containing a unique RFID code, to an interface by way of a cloud-based server. Ingestion data are displayed on this interface, and are accessible to patients via a mobile application, and to researchers and clinicians via an online system (14). By capturing objective medication ingestion data in real time, DPS present a novel method of adherence measurement that can promptly identify episodes and patterns of suboptimal adherence, and that allow for notification to a patient’s care team prior to the onset of persistent nonadherence (14,20–22). Thus, real-time adherence monitoring may permit delivery of evidence-based behavioral interventions at the moment of nonadherence.

DPS have previously been used to measure adherence and observe ingestion patterns with ART, antidiabetic agents, antihypertensives and opioids (14,23–25). Such investigations have demonstrated the feasibility of deploying DPS among specific patient populations. With respect to acceptability, small pilot studies using similar DPS to measure adherence to ART and tuberculosis treatment have found the DPS to be acceptable, and have documented participant satisfaction related to operating the DPS. The safety of DPS has also been demonstrated; two existing systems in the United States (US) have received clearance as medication event monitors from the FDA, and multiple investigations have demonstrated bioequivalence of several ART drugs, including tenofovir, an important component of PrEP (26,27).

Despite these advancements, the acceptability and optimal design of a DPS to measure PrEP adherence in MSM, particularly those with concomitant substance use disorders (28–34) and PrEP nonadherence (35,36), remains unknown. It is plausible that key design features of digital pills that have been accepted in other populations may not translate for those who may experience or fear social stigma related to PrEP use. For example, the use of a wearable device may not be acceptable in situations where PrEP adherence would be ideally recorded, and although recent data suggests that 81% of the US population own smartphones, those who may benefit most from a DPS may lack access to this technology (37). Yet, the ability to directly understand real-time PrEP adherence among individuals with substance use may enable timely delivery of interventions that boost adherence and prevent nonadherence. Understanding how MSM who use substances perceive the DPS, as well as clarifying the potential barriers to implementation in this population, will help to optimize this tool and provide valuable insights into PrEP ingestion patterns among individuals at high risk of HIV transmission.

Uptake of a DPS system among MSM who use substances is of interest, as MSM who use substances are less likely to achieve PrEP adherence (35,36). A study of MSM currently taking PrEP found that use of “club drugs” (e.g., methamphetamine, cocaine, ketamine, MDMA/ecstasy) increased the odds of same-day nonadherence by 50% and next-day nonadherence by 60% (35). Additionally, MSM who use substances are more likely to engage in condomless anal sex and have multiple sexual partners, which may place them at increased risk of HIV acquisition (28–34). Accordingly, the aim of this study was to understand the acceptance and optimal design of a DPS to measure PrEP adherence in HIV-negative MSM who self-reported non-alcohol substance use. We conducted individual quantitative assessments and semi-structured qualitative interviews, grounded in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (38), to explore barriers and facilitators associated with perceived use, design of the DPS, rudimentary messaging components of the DPS, and intended use of the technology to measure and improve PrEP adherence.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited through community outreach, social media platforms, and flyers posted at Fenway Health, a Boston community health center specializing in sexual and gender minority health, and recruitment events throughout the greater Boston area. All participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) 18 years or older; (2) self-reported HIV-negative; (3) cisgender MSM; (4) currently on PrEP or eligible for PrEP; and (5) self-reported substance use, excluding alcohol, within the last 6 months. Participants were excluded if they (1) self-reported living with HIV or (2) did not speak English. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Fenway Health. Qualitative interviews were conducted between November 2018 and July 2019.

Procedures

Potential participants were screened via phone or in person by a member of the study team. Eligible and interested individuals were scheduled for a one-time study visit where they consented to study procedures, and completed a brief, self-administered quantitative assessment on paper. Participants then took part in an audio-recorded, semi-structured qualitative interview in a private location at the study site with a trained member of the study team.

Measures

Quantitative assessment.

Participants self-reported sociodemographic information, including age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, relationship status, education, income, and primary care provider information. Health information questions included history of medical conditions, mental health problems, and sexually transmitted infections. Participants also reported on the number and type of sexual partners they have had in the last three months, preferred sexual activities, substance use before or during sexual activity, and condom use. The assessment included substance use questions surrounding frequency and severity of use.

Semi-structured qualitative interview.

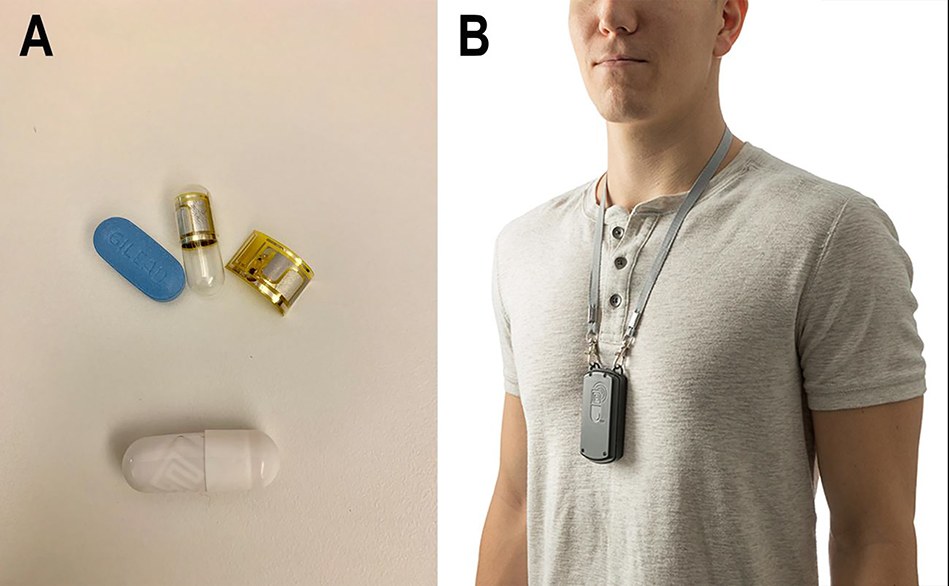

We developed a qualitative interview guide grounded in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) with an average length of 26.3 minutes (38). We role-played the interview guide with three members of the study team who ultimately conducted interviews to ensure questions and probes were clear (PC, YM, MJB). An expert in qualitative interview and analysis methods (RKR) trained interviewers (PC, YM, MJB) in specific qualitative interview techniques. Questions explored the acceptance and perceived usefulness of digital pills for measuring PrEP adherence, willingness to use digital pills, design of the DPS, structure of reminder messages, and potential uses for adherence data derived from the digital pill. Interviews also covered topics related to perceptions around data privacy and access; these results will be reported separately. A model of the digital pill and Reader device (etectRx, Gainesville, FL) was used to introduce the DPS to participants during the interview (Figure I). Sample questions and probes are provided in Table I. We adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) in the design, conduct and analysis of individual interviews (39).

Figure 1.

The digital pill system comprises an ingestible electronic sensor integrated into a gelatin capsule over-encapsulating tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada™) as a digital pill (a). Upon ingestion, the digital pill is activated and emits a radiofrequency signal that is transmitted to a wearable Reader device (b)

Table I.

Sample qualitative interview content areas, questions, and probes

| Content area | Sample questions and probes |

|---|---|

| Initial impressions of digital pill technology | • What are your initial reactions to the digital pill? • Are there design factors to the digital pill and Reader that prevent you from wanting to use it? • Why would these factors prevent your use of digital pills? |

| Willingness to use the DPS | • Given what you know, would you be willing to use the digital pill? Why/Why not? • If you were introducing the digital pill to your friends, what would you say about it? • Tell me how it would feel to use a DPS to record and visualize your PrEP adherence? |

| Perceptions around safety and the design of the DPS | • Are there design factors to the digital pill and reader that prevent you from wanting to use it? Why would these factors prevent your use of digital pills? • What are you thoughts about wearing the reader? Any changes to its design that would help? • What do you think about integrating the technology into another device that you use daily (e.g., watch, smartphone)? |

| Optimal users and uses of DPS | • What are potential factors that would prevent someone from wanting to use this technology? • If you were introducing the digital pill to your friends, what would you say about it? |

| Messaging and the DPS | • We programmed DigiPrEP to send a confirmatory text message each time you take your digital pill. I’m interested to hear your reaction to this. • Tell me about situations you would like to receive notifications about your adherence. • Would you be willing to receive messages regarding other influences of adherence? |

Sample topic areas, questions, and probes from individual qualitative interviews.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics from quantitative data were calculated. Audio-recorded interviews were professionally transcribed and then reviewed by study staff to confirm transcription accuracy and de-identify the text. We did not employ participant checking in the review of transcripts. Cleaned transcripts were entered into NVivo software (version 12) for data management of codes and applied thematic analysis (40–42). We applied the initial core components of the TAM (perceived use and intended use of a technology) to guide interpretation of interview transcripts. Four study team members (GG, MB, LM, YM) read transcripts individually to apply initial deductive codes. All transcripts were double-coded. Team members met regularly to review and discuss coding, adding new codes iteratively into the coding framework and resolving discrepancies at each stage. Discrepancies in computerized coding were reviewed by the PI and discussed with the study team; an audit trail of codebooks was preserved for reference and comparison throughout the process. At each five coded transcripts, the study team paused and assessed for thematic saturation (43). Three independent coders (GG, MB, YM) reviewed aggregate coding and identified key themes, which were presented to the full study team, who discussed and refined emergent themes. Finally, these themes were mapped onto the TAM to understand barriers and facilitators associated with DPS.

Results

Over the study period, 90 individuals were screened, 64 were eligible, and 30 enrolled in the study. Reasons for ineligibility included reporting no substance use in the past six months (n = 24) and reporting a positive or unknown HIV serostatus (n = 4); two participants were deemed ineligible for both of these reasons. All participants owned a smartphone. Thirty four individuals were eligible but did not enroll due to scheduling difficulties with the study team, or individuals who did not present at their scheduled interview time. Sociodemographic data for the 30 enrolled participants are presented in Table II. Mean age was 39.5 years old (range 23–63), most participants self-identified as Caucasian (63.3%), not Hispanic/Latino (73.3%), homosexual or gay (80%), and the majority had completed college (76.7%).

Table II.

Sociodemographic characteristics

| Variable | Sample (N = 30) |

|

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Age (in years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 39.5 (12.6) | - |

| Race* | ||

| White | 19 | 63.3 |

| Black/African American | 2 | 6.7 |

| More than one race or Other | 6 | 20 |

| Other | 2 | 6.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 22 | 73.3 |

| Education | ||

| High school graduate/GED | 2 | 6.7 |

| Some college education | 5 | 16.7 |

| College graduate | 8 | 26.7 |

| Some graduate education | 6 | 20 |

| Graduate/professional | 9 | 30 |

| Income (annual)a | ||

| Less than $6,000 | 3 | 10 |

| $6,000 to $11,999 | 4 | 13.3 |

| $12,000 to $17,999 | 2 | 6.7 |

| $18,000 to $23,999 | 3 | 10 |

| $24,000 to $29,999 | 2 | 6.7 |

| $30,000 to $59,999 | 6 | 20 |

| More than $60,000 | 9 | 31 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Homosexual or gay | 24 | 80 |

| Bisexual | 5 | 16.7 |

| Other | 1 | 3.3 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 21 | 70 |

| In a committed relationship | 2 | 6.7 |

| In a domestic partnership | 3 | 10 |

| Married | 3 | 10 |

| Divorced | 1 | 3.3 |

Data missing from one participant.

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Quantitative results

Descriptive statistics for select quantitative measures are presented in Table III. Participants reported a median of four sexual partners over the past three months (range 0–200). Nearly half of participants (n = 12) reported no condom use during the past 30 days. The majority (n = 17) reported current use of PrEP. Of these participants, 29.4% (n = 5) reported missing at least one dose of PrEP in the past two weeks. With respect to substance use, most participants reported non-medical use of stimulants (n = 19), as well as alcohol (n = 22), cannabis (n = 20), and other substances such as poppers (n = 18).

Table III.

Descriptive statistics for select quantitative measures

| Variable | Sample (N = 30) |

|

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Sexual partners in past three months | ||

| Median (range) | 4 (0–200) | - |

| On PrEP | ||

| Yes | 17 | 56.7 |

| No | 13 | 43.3 |

| Condom use in past 30 daysa | ||

| Never | 12 | 42.9 |

| Almost never | 4 | 14.3 |

| Sometimes | 3 | 10.7 |

| Almost every time | 5 | 17.9 |

| Every time | 4 | 14.3 |

| Ever had an STD | ||

| Yes | 18 | 60 |

| No | 12 | 40 |

| Had an STD in past 12 months | ||

| Chlamydia | 4 | 44.4 |

| Gonorrhea | 7 | 77.8 |

| Syphilis | 1 | 11.1 |

| Diagnosed mental health problems | ||

| Anxiety | 15 | 50 |

| Depression | 11 | 36.7 |

| Bipolar disorder | 2 | 6.7 |

| Schizophrenia | 1 | 3.3 |

| Other | 7 | 23.3 |

| None | 11 | 36.7 |

| Non-medical use of stimulants | ||

| Yes | 19 | 63.3 |

| No | 11 | 36.7 |

| Other substances in use | ||

| Alcohol | 22 | 73.3 |

| Marijuana | 20 | 66.7 |

| Sedatives | 6 | 20 |

| Opiates | 3 | 10 |

| Hallucinogens | 3 | 10 |

| Heroin | 1 | 3.3 |

| Other (e.g., poppers, amyl/butyl nitrate) | 18 | 60 |

| Missed doses of PrEP in past two weeks | ||

| Yes | 5 | 29.4 |

| No | 12 | 70.6 |

Data missing from two participants.

Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

Qualitative results

We identified five major themes surrounding the feasibility and acceptability of the DPS: (1) initial impressions of digital pill technology; (2) willingness to use the DPS; (3) perceptions around safety and the design of the ingestible sensor and wearable Reader; (4) optimal users and uses of the DPS; and (5) messaging connected to ingestions and nonadherence events (Table IV).

Table IV.

Participants’ perceived feasibility and acceptability of the Digital Pill System

| Themes | Content |

|---|---|

| Initial impressions of digital pill technology | • Technology is perceived as innovative and potentially valuable. • Access to their adherence data in real-time was perceived as a useful aspect of the technology. • Helpful for people starting PrEP. • Increased accountability around PrEP adherence. • A tool to build confidence in their ability to maintain adherence. |

| Willingness to use the DPS | • Willingness attributed to research with particular emphasis on studies that might benefit the MSM community. • Increased interested after learning more specific information about the operation of the technology. • Lack of need limited their interest in the technology, along with a greater uncertainty and lack of knowledge around how the technology works. |

| Perceptions around safety and the design of the DPS | • Safety-related and side effects concerns around using the DPS. • The design of the pill is not perceived as a barrier to using DPS. • No concerns about the palatability of the digital pill. • Opaque gelatin capsule is perceived as a benefit, decreasing stigma around PrEP. • The size of the wearable reader was perceived as a barrier, as well as the hazzle of charging it. • Reader is also viewed as a visual adherence reminder itself. • Suggestions such as, wearable reader can be integrated into a belt or a phone attachment. |

| Optimal users and uses of DPS | • For frequent travelers, people with memory issues, unstable living situations or disorganized lives, the DPS would be particularly helpful. • Viewed as a tool to overcome initial routine-related changes for people initiating PrEP. • Substances users and people having spontaneous sexual encounters will benefit from the DPS. |

| Messaging and the DPS | • Preference for confirmation messages after using the technology. • Confirmatory messages and reminder messages as potentially helpful for reinforcing their commitment to maintaining adherence. Also, they were seen as a way to connect with and feel cared by their providers. • Receptive to the idea of having a message after a nonadherence episode. • An important component of the technology will be the ability to customize frequency, timing, content and mode of delivery of all messages linked to the DPS. |

Initial impressions of digital pill technology

After participants were presented with the DPS, most described the technology as innovative and potentially valuable. Many participants liked the concept of having access to their adherence data in real-time and expressed a desire for a system that could independently verify their adherence patterns. Access to one’s own real-time adherence data, as well as the ability to receive notifications and information about one’s adherence on their smartphone, was perceived by many participants to be a useful component of the technology.

“I think that’s great for PrEP… I think it would be a clever way to get people on track to actually take their pills. A lot of people would be like, ‘Oh, I don’t need it.’ But look, let me tell ya. My past experience, yes.” (Age 36, on PrEP)

“It’s connecting you with technology, and then it’s like… it’s making you inseparable.” (Age 27, not on PrEP)

Accountability and verification of PrEP adherence using the DPS

Many participants reported that the primary reason to use the DPS in the context of PrEP would be to improve their adherence. Participants who were currently on PrEP reflected that, in retrospect, the DPS would have been helpful when they started PrEP, viewing it as a tool to overcome initial routine-related changes associated with the initiation of a new medication. Similarly, those who were not currently on PrEP viewed the DPS as a method to help them understand their progress in adherence. Both current PrEP users and non-PrEP users who were open to this idea explained that the DPS would hold them accountable for taking PrEP on a regular basis. A number of participants also described past episodes when they were unsure if they had already taken their PrEP on a given day, noting that the DPS could serve as a way to validate past ingestions. Additionally, participants reported that the DPS could help them build confidence in their ability to maintain adherence; indeed, increased confidence was discussed as a powerful means by which to mitigate potential health anxiety related to nonadherence.

“It would make me feel good. Not good that I didn’t take my medicine but good that I’m having the assistance through this machine to learn to take my pills properly.” (Age 40, on PrEP)

“It helps me to have more confidence in other areas of my life, knowin’ that I’m HIV negative, and it just opens more possibilities of what I can do with my life and what other areas I might wanna challenge myself in.” (Age 53, on PrEP)

Willingness to use the DPS

More than half of participants, including some who self-reported adequate baseline PrEP adherence, described themselves as open to using the DPS (n = 19). Several participants noted that they would be willing to try the DPS in the context of a research investigation focused on PrEP adherence, with a particular emphasis on studies that might benefit the MSM community. Participants also discussed an increased interest in using the DPS after learning more specific information about how the technology operates, including the time commitment required to utilize the Reader device during each use.

“I just see this [technology] as the most fantastic thing on so many levels of chronic illness treatment other than this. It’s very exciting to me.” (Age 55, not on PrEP)

“When I first read about this study… I thought to myself, well, [the Reader] is probably something you have to keep on you all the time, in which case I wouldn’t be interested in it, but if… it would just sit in the medicine cabinet, then I’d be intrigued.” (Age 39, on PrEP)

Not all participants expressed a willingness to use the DPS. For some, a perceived lack of need limited their interest in the technology, while a broader uncertainty and lack of knowledge about the DPS was paramount for others. One participant noted that he would prefer to wait until the DPS had been more widely used and tested before trying it himself.

“I struggle to think of a situation where I would need that for my PrEP just because it’s like I do it at the same time every day and… whether I’m drinking alcohol or engaging in risky or sexual behaviors, that stuff to me doesn’t impact the fact that I take my PrEP every morning when I brush my teeth.” (Age 39, on PrEP)

“It’s something I’ve never heard of before. It’s something new. I actually don’t know if people will take it. I, personally, wouldn’t take it right away. I’d have to see more studies and, yeah, let time pass a little bit.” (Age 60, not on PrEP)

Perceptions of safety and the design of the DPS

A number of participants expressed safety-related concerns around using the DPS (n = 12), particularly as it relates to ingesting the digital pill itself. This was perceived as a barrier to acceptance of the DPS and its application in the real world. Some worried that ingesting a radiofrequency emitter would cause adverse events that might compound existing side effects from PrEP. Others reported concerns about the metal components of the DPS, citing allergies to various materials, as well as the potential side effects of ingesting digital pills.

“I do have initial concerns just because I have a lot of knowledge about how technologies are affecting our body, and I’d want to know more about the filament that gets broken down because then you’re putting a piece of technology in your body that’s transmitting a signal that’s non-organic.” (Age 29, not on PrEP)

“I’m definitely willing to try it but just being nervous at first. Just to see what my body would react to once I’m gonna take to it… For example, side effects…am I gonna throw up if I—once I take this? ‘Cause sometimes even just thinking about certain things you just—you wanna just throw it up. Either that or is my stomach gonna—am I gonna feel it in my stomach? Am I still gonna feel awkward in my intestines—when it’s going through the system, how’s my body gonna feel or react to it?” (Age 36, on PrEP)

Design of the digital pill and intrusiveness of ingesting a radiofrequency transmitter

Other participants did not perceive safety issues related to the DPS as a barrier to adoption. They also noted that the design of the digital pill and ingestible sensor would not be a barrier to using a DPS. They reported that ingesting a digital pill would feel similar to taking a standard PrEP tablet, and that the concept of swallowing an RFID tag, overencapsulating PrEP, was novel and exciting. These participants additionally noted that the gelatin capsule and RFID tag did not contribute significantly to the size of PrEP; therefore, they were not concerned about the palatability of the digital pill.

“When people actually have these, they do not even have the feeling that they are ingesting something that’s not like a regular capsule. It gives you the feeling that it’s just like any other capsule. You don’t have to think twice before taking this because… it acts as a medicine.” (Age 27, not on PrEP)

“Seems cool. Seems like it doesn’t really ask much of people who are taking medication. The pill still seems to me like a normal pill, so it’s nothing different in that sense.”(Age 25, not on PrEP)

Participants described the use of an opaque gelatin capsule, as opposed to a transparent one, as an additional benefit, noting that it could quell potential safety concerns that might arise from the ability to directly see the radiofrequency emitter during each dose. Participants also mentioned that the opaque capsule may mask the signature blue color of Truvada for PrEP, thereby decreasing the potential for PrEP-related stigma.

“Not [a] transparent one. Transparent one is like ingesting an LED bulb. Then it gives you that feeling, ‘Oh my god.’ Yeah. Even this chip that you see, people might still have that thing of, ‘Oh my god, I swallowed a chip. What’s gonna happen to me?’ This doesn’t give you that feeling. It’s like a normal capsule.” (Age 27, not on PrEP)

Barriers associated with using the Reader component of the DPS

A major perceived barrier to operating the DPS was the size of the wearable Reader. While recognizing that future versions of the device are likely to be miniaturized, participants viewed the current iteration of the technology – which requires that the Reader be worn on a lanyard around one’s neck – as bulky and inconvenient. They described the idea of carrying and traveling with the Reader, as well as the requirement that they remember to use an entirely separate device when taking their daily medication, as cumbersome.

“That’s a big device... If you have to carry that around, I think it would be very off-putting because at least for me, I don’t even have a wallet because I think wallets are too thick.” (Age 38, on PrEP)

“My initial thought was, wow, this is bulky… If I had to wear this around my neck walking down the street, I wouldn’t love it.” (Age 24, on PrEP)

Participants also described a number of potential strategies for circumventing these barriers. The most frequently reported strategy was to wear the Reader only when taking their medication in order to avoid the inconvenience of wearing the device for longer periods of time. This reflects a misconception held initially by many participants that the Reader would be required to be worn at all times, regardless of when an individual took their mediation. Other strategies included placing the device close to their body while taking their medication for the most efficient use, storing it in a location at home that they would see every day (e.g., next to their toothbrush), and storing it inside a travel bag in anticipation being away from home.

“I didn’t realize it transmitted that quickly. It was my first thought that somebody would have to digest the circuit board or whatever to emit a signal, but it’s almost instantaneous. Just put it next to your pill bottles, I think.” (Age 59, on PrEP)

“I wouldn’t wear it around my neck. I don’t know. I probably would probably wear—always keep it on me somewhere like in my pocket or somewhere where—like my bag but not way down in there.” (Age 36, on PrEP)

Despite the many perceived barriers to operating the Reader, some participants described its size as serving as a visual adherence reminder in itself. For these participants, the mere existence of such a prominent device near their pill bottle was viewed as an additional way to prompt them to take their medication, thereby reinforcing adherence behavior.

“If you were to just remember to put [the Reader] on, then I don’t think you’d forget to take your PrEP with it kind of thing. In a way it sounds redundant, I guess, because I feel like, if this isn’t permanently on you, then you make a conscious effort to put it on. When you make a conscious effort to put it on in the first place then you’re not going to forget to take the PrEP.” (Age 23, on PrEP)

“It’s a big device and when you see it on the table... you become more aware...”(Age 38, on PrEP)

When asked to expand upon their concerns about the Reader design, participants imagined that improved versions might include a Reader that is integrated directly into a watchband, smartphone or phone case, all of which were viewed as less intrusive than the current version. Participants also described future iterations of the Reader that could be integrated into a belt, a fob attached to a keychain, or a thin, credit card-sized object that could fit into a wallet.

Optimal users and uses of the DPS

Part of the TAM explores the potential application or intended use of technologies. In order to evaluate potential uses of the DPS, participants were asked to think about specific groups of people who would benefit from the use of the DPS, as well as scenarios in which the DPS would be most beneficial. Participants identified those with frequent travel or changes in routines, memory issues, unstable living situations, or otherwise disorganized lives as groups for whom the DPS would be particularly helpful, while also noting that these individuals may be difficult to engage more generally. Many also reflected on the potential utility of the DPS for early habit formation when beginning a new medication, noting that individuals who were starting PrEP for the first time might benefit from using this technology.

“I think the people that are at risk of not taking PrEP are the ones that would not use this. Because they are—I don’t know—they are disorganized. They don’t have a routine. It seems like I’m just thinking out loud here. They lead, not chaotic lives, but chaotic routines, and I think that this would get lost somewhere.” (Age 38, on PrEP)

“I think that it might be helpful for people that are new to the medication to have some type of a reminder or something until the person gets into the habit of taking it on a regular basis as the doctor prescribes it.” (Age 54, on PrEP)

With respect to optimal deployment strategies and contexts for the DPS, some participants identified daily changes in routines (e.g., patterns on weekdays versus weekends, staying over at a partner’s home) were identified as events that commonly disrupt medication-taking behavior; as such, these contexts were described as opportunities where the DPS could be useful for maintaining and reinforcing adherence.

“I take vitamins every day, so I usually just try to take it when I take my vitamins… I’m a nurse, so… I wouldn’t say there’s one specific time of the day that I take my meds because normally—like today, I didn’t work, so I woke up, took them in the morning, and went about my day. But, if I had worked last night, I wouldn’t have wanted to take them right before I go to bed in the morning ‘cause—I don’t know. Something about taking pills seems like starting your day to me. It puts me in a position to not sleep.” (Age 24, on PrEP)

Participants also described events like substance use and spontaneous sexual encounters as having historically compromised their ability to remember to take PrEP. As such, many participants viewed these types of events as episodes in which the DPS would be helpful and were willing to accept use of the technology in the context of substance use to help reinforce PrEP adherence during these episodes.

“I have had no issues forgetting to take PrEP, only if I have had like stimulant and drug use issues or if I had moments of using, I wasn’t always taking PrEP on time.” (Age 31, not on PrEP)

“I can see how maybe if someone were using a fair amount of controlled substances, it could be useful just because maybe that beep would be the little thing that brings them back to reality enough.” (Age 50, on PrEP)

Messaging connected to ingestions and nonadherence events

Participants considered three major categories surrounding messaging linked to the DPS: the delivery of messages to confirm that ingestions had been detected, reminder messages prior to one’s pre-specified dosing window, and reminder messages in the context of nonadherence events. The current iteration of the DPS includes simple, neutral text messages to indicate that the ingestion was recorded on the interface (e.g., “medication ingestion detected”). When asked if these messages would influence participants’ medication-taking behavior, the response was mixed; some reported that these messages would provide confirmation that they had used the technology successfully, thus reducing concerns about DPS malfunctions. Many participants additionally described these confirmatory messages, as well as reminder messages sent prior to one’s dosing window, as potentially helpful for reinforcing their commitment to maintaining PrEP adherence.

“It’d be nice, just almost like praise for the day, yes, oh, you took your PrEP, that’s great.” (Age 29, on PrEP)

“I think it would be helpful [receiving a reminder message from DPS] because in this world I feel there is no person who does not rely on a calendar.” (Age 27, not on PrEP)

Others, however, noted that such confirmatory and reminder messages could be excessive, and instead described a strategy of intensive daily messaging for a set period of time only, followed by a gradual tapering off of messages, which would correspond to an individual’s demonstrated level of adherence using the DPS over time.

“I think it would be useful. I would be thankful... I think, as long as the texts are customized to people’s schedules and not reminding people who are gonna do it anyway, then I think it could be done effectively without being annoying.” (Age 31, on PrEP)

Contextual basis of reminder messages linked to nonadherence events

Many participants were also receptive to the idea of receiving additional reminder messages following instances of nonadherence documented by the DPS. These messages were viewed as an acceptable means by which to introduce adherence interventions, particularly given that they were perceived to be more foolproof than other methods of managing one’s adherence. Some participants also suggested that this messaging modality could function as a platform in which anticipatory reminders could help reinforce PrEP adherence.

“I would actually love if I got… a message on my phone saying, ‘Hey, seems like you forgot your PrEP today’ … because then, that’s a great way of reminding.” (Age 38, on PrEP)

“It would be helpful to me if… I haven’t taken it by 6:30 every morning, this thing sends me a text message to my phone, ‘Hey you haven’t taken your PrEP today.’ I guess being a little cynical, I could do that on my own on my phone right now if I really wanted to. Now, granted, I guess there’s some user error. I hit snooze. I get sidetracked… Maybe this thing sends you a second reminder ‘cause it is detecting it biologically.” (Age 39, on PrEP)

Some participants discussed the use of such reminders from the DPS, following instances of nonadherence, in the context of their relationships with their healthcare providers; the receipt of such messages was perceived as an additional way to connect with, and feel cared for by, their providers.

“I’d feel loved… That someone loves me, or that someone cares for me… ‘cause people like that. Yeah. I don’t think there’s anything negative about that. It lets them know they’re doing a good job and that they’re following the regimen they’re supposed to be on.” (Age 54)

“Oh, I love it. I like to be connected with doctors, pharmacy, medication that for some reason is making me feel good. Safe. Involved with something that could get better for everybody.” (Age 45)

Participants also commented on the structure of confirmatory messages, reminder messages prior to one’s dosing window, and reminder messages linked to nonadherence. In particular, they expressed a desire to have the ability to customize the frequency, timing, content and mode of delivery of all messages linked to the DPS; this was described as an especially important component of the technology – and one that would make it more acceptable to potential users.

“You would have a little dashboard on the phone that said, ‘What sort of PrEP compliance help are you seeking: daily? Do you just want a monthly summary or a weekly summary? Are you in a more ‘let yourself go’ mode, and you’d like it every 12 hours?’ I would still say, though, stick with the 24 [hours], because people habituate, and if something comes in too often they’ll ignore it…” (Age 50, on PrEP)

“I think that it would be helpful. A reminder in the morning and a friendly reminder or something linked to one of the—I think, yeah, there are things that people always see in the morning, right? I don’t know. It depends. Probably, it would be nice if you can change the way you are notified, like probably email or just an alert… Customizing the notification.” (Age 26, on PrEP)

Discussion

Prevention of new HIV infections is a key pillar of the UNAIDS “Getting to Zero” strategy (44), and one method of achieving zero new HIV infections is increasing access and uptake of PrEP among eligible individuals. Despite advancements in expanding access to PrEP, it remains underutilized, and adherence remains suboptimal. The development of tools that better track and assess PrEP adherence, and respond to events of nonadherence, may help PrEP initiators and experienced PrEP users to achieve optimal adherence. This investigation demonstrates that HIV-negative MSM who report the use of non-alcohol substances are generally accepting of a DPS to measure and record real-time PrEP adherence, including individuals who already perceived themselves to be PrEP adherent, but describe a number of potential barriers to adoption of the technology. Many participants viewed the DPS as providing an incontrovertible and readily accessible record of their adherence behavior, which had the potential to increase perceived confidence and personal accountability around PrEP-taking behavior. While DPS have been in development for at least a decade, the technology was still perceived to be innovative and novel by the MSM in the present study.

The TAM builds a framework through which to evaluate the application of novel health technologies by exploring the user’s perceived use, intended use and actual use of a technology (38). Grounding our qualitative interviews on the pillars of TAM allowed to identify important barriers and facilitators related to participants’ perceived and intended uses of the DPS. The majority of barriers centered around the design of the Reader, the composition of the digital pill, and perceived safety issues. The majority of facilitators centered around the innovative nature of DPS and the value of having real-time access to directly measured PrEP adherence data.

The Reader device was perceived to be the largest barrier to operation of the DPS, primarily as a result of its size and shape. Because the digital pill emits a radiofrequency signal, the technology requires a receiver that can capture this signal; the DPS described in this investigation boosts signaling strength within the radiofrequency transmitter, allowing for the use of an off-body Reader. While miniaturization or integration of the technological receiver capability of the Reader will occur as DPS technology advances, there may be instances where the current iteration of Reader is acceptable to certain participants who respond positively to visual cues surrounding adherence.

Another design-related barrier to acceptance of the DPS was the transparent version of the digital pill that was used to illustrate the interior components during the qualitative interviews. Participants considered this version of the pill to be disconcerting as it exposed the electronic components of the digital pill. In order to eliminate this barrier, participants proposed the use of opaque gelatin capsules. Similarly, participants reported concerns around the safety of ingesting electronic components of the digital pill. They described concerns around the potential release of metals (silver and zinc used in the radiofrequency emitter) into their body. As a solution to this barrier, participants recommended we provide additional safety data to study participants about preclinical studies surrounding safety of the digital pill. Importantly, during the study period, the DPS described in this investigation obtained 510K status from the FDA (45). Part of this clearance includes enhanced toxicology data around the safety of the ingestible sensor and adverse event reporting; we anticipate that the FDA clearance of this DPS will assuage many of the initial safety-related concerns posed by participants in the present study.

Future Reader design should be guided by user-centered feedback. In our qualitative interviews, participants suggested integrating the Reader technology into a smartphone case, a wallet card, or clothing accessories such as a belt buckle. The intent of these modifications would be to further integrate the Reader into the fabric of daily life, rendering a DPS even less intrusive and the experience of its use more akin to that of a typical medication ingestion. These suggestions are consistent with prior DPS studies that have used other types of Reader devices that require user interaction, including a wearable on-body patch system used in another DPS, which may lead to disengagement with a DPS (22). Future iterations of the DPS may therefore need to offer a wide variety of relay devices that accommodate daily routines as well as users’ individual preferences.

Facilitators to adoption of the DPS centered around the perceived innovative nature of the system and the benefits of accessing real-time PrEP adherence data. Compared to barriers, these facilitators mostly mapped onto the TAM intended use domain. Participants valued the innovative nature of the technology because of its ability to generate real-time PrEP adherence data. These data were described as a way to generate personal insights around the context of their adherence and nonadherence, and to receive feedback on their PrEP use, which could then be customized to meet their unique needs. For example, an individual who uses PrEP on an episodic, on-demand basis, and who demonstrates excellent adherence via a DPS, could signal a period of increased risk via the technology, which would trigger increased vigilance and intervention to support their adherence. Likewise, an individual who maintains continuous PrEP adherence, but who develops waning adherence during a particular period of time, could have their data used to signal the need for more intensive adherence supports. Providers could use DPS data to access patients with suboptimal adherence in order to better to understand the context in which this occurs. Finally, as on-demand PrEP becomes increasingly popular (46–48), DPS may also be used to understand other contextual behaviors around PrEP use and adherence, including HIV risk behaviors related to sexual activity or substance use (49). The DPS platform can be used to collect patient reported outcomes surrounding events of adherence or nonadherence, deliver ecological momentary assessments around ingestion patterns, or complete closed loop feedback systems that respond to nonadherence (50,51).

Participants also discussed the value of delivering messages surrounding adherence and nonadherence events linked to the DPS. They were accepting of confirmatory feedback messages, and described the need for simple, neutral messaging confirming proper operation of the DPS as a closed feedback system. They also identified reminder messages prior to a pre-specified dosing window, as well as reminder messages following nonadherence events, as largely acceptable and desirable avenues through which to engage with the DPS, monitor their PrEP adherence, and potentially communicate with healthcare providers. Consistent with studies among individuals living with HIV that have examined reactions to messaging surrounding ART adherence detected by a smart pill bottle (52,53), participants in the present study described the importance of detecting nascent nonadherence events and providing adherence supports during these times. These data suggest that the DPS can be deployed in the real world as both a clinical and research tool geared towards providing direct measures of PrEP adherence. Additionally, this investigation demonstrates that MSM will interact with simple messages from the DPS; the technology may therefore present a unique opportunity to impart PrEP adherence skills linked to real-time measures of adherence.

It is important for researchers to define the difference between messaging integral to DPS like neutral confirmation messages, and more structured messages delivering contingent reinforcement or corrective feedback to individuals as part of a behavioral intervention. Our data suggest that some form of neutral confirmation messaging is vital to maintaining adherence to a DPS so that actual adherence to PrEP can be recorded using this system. Future iterations of DPS-enabled messaging architecture should involve the development of feedback loops that provide real-time behavioral interventions that respond to PrEP nonadherence and immediately reinforce adherence. In light of data suggesting that substance use may increase the risk of next day PrEP nonadherence, a DPS messaging architecture may also include anticipatory reminders to reinforce adherence during episodes of substance use (30).

Additionally, iterative refinements in energy harvesting (e.g., the use of physiologic processes, such as generation of the acidic environment in the stomach, to generate energy to power devices) to boost the strength of the radiofrequency signal from the ingestible sensor, combined with the miniaturization and adaption of the wearable Reader into an increasingly unintrusive design, will continue to make the experience of using a DPS equivalent to taking standard medication. The ultimate aim will be to ensure that use of a DPS is seamless, allowing the user, scientists, and/or clinicians to focus on the adherence behavior, ingestion patterns, and linked interventions that accompany this type of technology.

There are several limitations to this investigation. First, our qualitative work asked participants about their perceived willingness to use the digital pill, but the lived experiences of individuals who actually use DPS may vary. Second, our study participants were predominantly Caucasian and well educated. It is possible that individuals of different racial backgrounds and education status may perceive the use of an ingestible sensor differently; therefore, our findings cannot be considered generalizable to MSM more broadly. Third, we were only able to enroll English-speaking individuals in this study; future work should explore the use of DPS in non-English speakers. Fourth, our eligibility criterion around negative HIV status was based on self-report only, and did not include a specified timeframe for a prior negative HIV test, nor did our procedures include confirmation of participants’ self-reported status via rapid HIV test. Fifth, this manuscript does not describe considerations surrounding data privacy and access to the DPS. While our qualitative interviews raised a number of perspectives about these topics, the breadth of qualitative data collected requires a more nuanced discussion in future publications (currently in process), as participant feedback around data security and privacy may have an impact on acceptance of the DPS. Finally, in the midst of this investigation, the DPS we described to participants in our qualitative interviews received clearance by the FDA. This may change perceptions of acceptability and safety surrounding the DPS and will require further exploration in this population.

These data helped to inform the development and optimization of a 90-day, open-label trial to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of deploying a DPS for PrEP adherence in HIV-negative MSM who use substances other than alcohol, which recently concluded. Our next step will be to conduct several additional demonstration trials to understand the real-world operability of digital pills. This investigation demonstrates that DPS are perceived as an acceptable technology to measure PrEP adherence among MSM with non-alcohol substance use. While there are many potential avenues for further optimization of the technology, MSM are largely willing to ingest digital pills and perceive value in having access to their real-time, personal adherence data. Digital pill technology may therefore be deployed to measure and monitor PrEP adherence, and can be combined with targeted interventions that detect and respond to suboptimal adherence in real-time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: PRC is funded by NIH K23DA044874, R44DA051106 and research funding from Gilead Sciences (ISR-17-1018), Hans and Mavis Psychosocial Foundation and e-ink corporation, KM and CO are funded by NIAID P30AI060354, EWB and RKR are funded by NIH R01DA047236.

Conflicts of interest: This study was funded through unrestricted research funds through the ISR program at Gilead Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, Buchbinder S, Lama JR, Guanira JV, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir exposure and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012. September 12;4(151):151ra125–151ra125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doblecki-Lewis S, Cohen S, Liu A. Clinical treatment options infectious diseases: Update on PrEP implementation, adherence, and advances in delivery. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2015. June;7(2):101–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012. August 2;367(5):399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010. December 30;363(27):2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2015. February 5;372(6):509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer KH, Safren S, Haberer J, Elsesser S, Clarke W, Hendrix CW, et al. Project PrEPARE: High levels of medication adherence with continued condomless sex in U.S. men who have sex with men in an oral PrEP adherence trial. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014. October;30(S1):A23–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2012. August 2;367(5):411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haberer JE. Current concepts for PrEP adherence in the PrEP revolution: from clinical trials to routine practice. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016. January;11(1):10–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014. September;14(9):820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Anderson PL, Doblecki-Lewis S, Bacon O, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal- and community-based sexual health services. JAMA Intern Med. 2016. January 1;176(1):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spinelli M, Haberer J, Chai P, Castillo-Mancilla J, Anderson P, Gandhi M. Approaches to objectively measure antiretroviral medication adherence and drive adherence Interventions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020;In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Haberer JE. Adherence measurements in HIV: new advancements in pharmacologic methods and real-time monitoring. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018. February;15(1):49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stirratt MJ, Dunbar-Jacob J, Crane HM, Simoni JM, Czajkowski S, Hilliard ME, et al. Self-report measures of medication adherence behavior: recommendations on optimal use. Transl Behav Med. 2015. December;5(4):470–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chai PR, Castillo-Mancilla J, Buffkin E, Darling C, Rosen RK, Horvath KJ, et al. Utilizing an ingestible biosensor to assess real-time medication adherence. J Med Toxicol. 2015. December;11(4):439–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Alili M, Vrijens B, Demonceau J, Evers SM, Hiligsmann M. A scoping review of studies comparing the medication event monitoring system (MEMS) with alternative methods for measuring medication adherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016. July;82(1):268–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baxi SM, Liu A, Bacchetti P, Mutua G, Sanders EJ, Kibengo FM, et al. Comparing the novel method of assessing PrEP adherence/exposure using hair samples to other pharmacologic and traditional measures. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015. January;68(1):13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garrison LE, Haberer JE. Technological methods to measure adherence to antiretroviral therapy and preexposure prophylaxis: Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017. September;12(5):467–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR, Baeten JM, Curran K, Koechlin F, Amico KR, et al. Defining success with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: a prevention-effective adherence paradigm. AIDS. 2015. July;29(11):1277–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chai P, Rosen R, Boyer E. Ingestible biosensors for real-time medical adherence monitoring: MyTMed. Proc Annu Hawaii Int Conf Syst Sci. 2016;3416–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vallejos X, Wu C . Digital medicine: innovative drug-device combination as new measure of medication adherence. J Pharm Technol. 2017. August;33(4):137–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill LM, Golin CE, Pack A, Carda-Auten J, Wallace DD, Cherkur S, et al. Using real-time adherence feedback to enhance communication about adherence to antiretroviral therapy: patient and clinician perspectives. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2020. January;31(1):25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daar ES, Rosen MI, Wang Y, Siqueiros L, Shen J, Guerrero M, et al. Real‐time and wireless assessment of adherence to antiretroviral therapy with co‐encapsulated ingestion sensor in HIV-infected patients: a pilot study. Clin Transl Sci. 2020. January;13(1):189–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chai PR, Carreiro S, Innes BJ, Rosen RK, O’Cleirigh C, Mayer KH, et al. Digital pills to measure opioid ingestion patterns in emergency department patients with acute fracture pain: a pilot study. J Med Internet Res. 2017. January 13;19(1):e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chai PR, Carreiro S, Innes BJ, Chapman B, Schreiber KL, Edwards RR, et al. Oxycodone ingestion patterns in acute fracture pain with digital pills. Anesth Analg. 2017. December;125(6):2105–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carreiro S, Smelson D, Ranney M, Horvath KJ, Picard RW, Boudreaux ED, et al. Real-time mobile detection of drug use with wearable biosensors: a pilot study. J Med Toxicol. 2015. March;11(1):73–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu H, Daar E, Wang Y, Siqueiros L, Campbell K, Shen J, et al. Pharmacokinetics of coencapsulated antiretrovirals with ingestible sensors. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2020. January 1;36(1):65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chai PR, Pereira LM, Jambaulikar GD, Carrico AW, O’Cleirigh C, Mayer KH, et al. Short communication: bioequivalence of tenofovir component of tenofovir/rilpivirine/emtricitabine in digital pills. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2019. April;35(4):361–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carey JW, Mejia R, Bingham T, Ciesielski C, Gelaude D, Herbst JH, et al. Drug use, high-risk sex behaviors, and increased risk for recent HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Chicago and Los Angeles. AIDS Behav. 2009. December;13(6):1084–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostrow DG, Plankey MW, Cox C, Li X, Shoptaw S, Jacobson LP, et al. Specific sex drug combinations contribute to the majority of recent HIV seroconversions among MSM in the MACS. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009. July;51(3):349–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santos G-M, Coffin PO, Das M, Matheson T, DeMicco E, Raiford JL, et al. Dose-response associations between number and frequency of substance use and high-risk sexual behaviors among HIV-negative substance-using men who have sex with men (SUMSM) in San Francisco. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013. August;63(4):540–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freeman P Methamphetamine use and risk for HIV among young men who have sex with men in 8 US cities. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011. August 1;165(8):736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoenigl M, Chaillon A, Moore DJ, Morris SR, Smith DM, Little SJ. Clear links between starting methamphetamine and increasing sexual risk behavior: a cohort study among men who have sex with men. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016. April;71(5):551–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoenigl M, Chaillon A, Morris SR, Little SJ. HIV infection rates and risk behavior among young men undergoing community-based testing in San Diego. Sci Rep. 2016. May;6(1):25927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vosburgh HW, Mansergh G, Sullivan PS, Purcell DW. A review of the literature on event-level substance use and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012. August;16(6):1394–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grov C, Rendina HJ, John SA, Parsons JT. Determining the roles that club drugs, marijuana, and heavy drinking play in PrEP medication adherence among gay and bisexual men: Implications for treatment and research. AIDS Behav. 2019. May;23(5):1277–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hambrick HR, Park SH, Schneider JA, Mayer KH, Carrico AW, Sherman SE, et al. Poppers and PrEP: use of pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men who use inhaled nitrites. AIDS Behav. 2018. November;22(11):3658–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pew Research Center. Internet & Technology Mobile Fact Sheet [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2020 Aug 24]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/

- 38.Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989. September;13(3):319–40. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007. September 16;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006. January;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E. Applied thematic analysis. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42.QSR International. NVivo software. 2018.

- 43.Ando H, Cousins R, Young C. Achieving saturation in thematic analysis: development and refinement of a codebook. Compr Psychol. 2014. January;3:03.CP.3.4. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Getting to zero: 2011–2015 strategy [Internet]. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2010. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/sub_landing/files/JC2034_UNAIDS_Strategy_en.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.etectRx®, Inc. etectRx Announces U.S. FDA Clearance of Novel Ingestible Event Marker [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://etectrx.com/etectrx-announces-u-s-fda-clearance-of-novel-ingestible-event-marker/

- 46.Antoni G, Tremblay C, Delaugerre C, Charreau I, Cua E, Rojas Castro D, et al. On-demand pre-exposure prophylaxis with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus emtricitabine among men who have sex with men with less frequent sexual intercourse: a post-hoc analysis of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. Lancet HIV. 2020. February;7(2):e113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parienti J-J. On-demand PrEP efficacy: forgiveness or timely dosing. Lancet HIV. 2020. February;7(2):e79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molina J-M, Charreau I, Spire B, Cotte L, Chas J, Capitant C, et al. Efficacy, safety, and effect on sexual behaviour of on-demand pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in men who have sex with men: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2017. September;4(9):e402–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shrier LA, Koren S, Aneja P, de Moor C. Affect regulation, social context, and sexual intercourse in adolescents. Arch Sex Behav. 2010. June;39(3):695–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smiley SL, Milburn NG, Nyhan K, Taggart T. A systematic review of recent methodological approaches for using ecological momentary assessment to examine outcomes in U.S. based HIV research. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020. August;17(4):333–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hensel DJ, Fortenberry JD, Harezlak J, Craig D. The feasibility of cell phone based electronic diaries for STI/HIV research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012. December;12(1):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dworkin MS, Panchal P, Wiebel W, Garofalo R, Haberer JE, Jimenez A. A triaged real-time alert intervention to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among young African American men who have sex with men living with HIV: focus group findings. BMC Public Health. 2019. December;19(1):394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sabin LL, Bachman DeSilva M, Gill CJ, Zhong L, Vian T, Xie W, et al. Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy with triggered real-time text message reminders: the China adherence through technology study. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015. August;69(5):551–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.