Abstract

Objective:

To compare in-hospital outcomes after umbilical cord milking versus delayed cord clamping among infants <29 weeks’ gestation.

Study design:

Multicenter retrospective study of infants born <29 weeks’ gestation from 2016 to 2018 without congenital anomalies who received active treatment at delivery and were exposed to UCM or DCC. The primary outcome was mortality or severe (grade III or IV) intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) by 36 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA). Secondary outcomes assessed at 36 weeks PMA were mortality, severe IVH, any IVH or mortality, and a composite of mortality or major morbidity. Outcomes were assessed using multivariable regression, incorporating mortality risk factors identified a priori, confounders, and center. A prespecified, exploratory analysis evaluated severe IVH in two GA strata, 22-246/7 and 25-286/7 weeks.

Results:

Among 1,834 infants, 23.6% were exposed to UCM and 76.4% to DCC. The primary outcome, mortality or severe IVH, occurred in 21.1% of infants: 28.3% exposed to UCM and 19.1% exposed to DCC, with an adjusted odds ratio that was similar between groups (aOR 1.45, 95% CI 0.93, 2.26). UCM exposed infants had higher odds of severe IVH (19.8% UCM vs. 11.8% DCC, aOR 1.70 95% CI 1.20, 2.43), as did the 25-286/7 week stratum (14.8% UCM vs. 7.4% DCC, aOR 1.89 95% CI 1.22, 2.95). Other secondary outcomes were similar between groups.

Conclusion:

This analysis of extremely preterm infants suggests that DCC is the preferred practice for placental transfusion, as UCM exposure was associated with an increase in the adverse outcome of severe IVH.

Trial registration

Keywords: Placental transfusion, Intraventricular hemorrhage, Neonatal Research Network

Compared with immediate cord clamping (ICC), delayed cord clamping (DCC) has associated benefit in decreasing mortality, all grades of IVH, and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in preterm infants.(1)(2) Multiple professional organizations endorse at least 30 seconds of DCC for preterm infants who do not require resuscitation.(3–6) However, many preterm infants require some intervention to transition to extrauterine life, which may limit opportunities for DCC in this population. In such situations placental transfusion via umbilical cord milking (UCM) is a potential alternative, as it can be performed quickly and may provide similar benefits.(7)

The majority of trials comparing DCC and UCM have either concentrated on establishing the safety profile of UCM or were powered to determine the effect of UCM on initial hematocrit, need for blood transfusions, or hemodynamics.(8–11) Until recently, trials have reported similar rates of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) after DCC and UCM.(12–14) The comparative effectiveness of the two modes of placental transfusion remains debatable for some providers, and favorable results from small trials have led to continued use of UCM in clinical practice despite current recommendations.(15) In 2019, a multicenter trial was stopped early due to increased rates of severe IVH among infants exposed to UCM, specifically among infants 23-27 weeks’ gestation.(16) Thus, additional studies assessing the potential benefits or harm after exposure to UCM are needed.

The objective of our retrospective study was to compare the risk-adjusted rates of mortality or severe IVH by 36 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA) after UCM versus DCC among infants born < 29 weeks’ gestation in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network (NRN). Additionally, we performed a prespecified, exploratory analysis evaluating severe IVH in two gestational age strata, 22-246/7 and 25-286/7 weeks.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from the NRN Generic Database (GDB). The cohort includes infants born between 220/7-286/7 weeks’ gestation in NRN centers from January 1st, 2016 to December 31st, 2018. Each participating center obtained institutional review board approval for the NRN GDB registry. Based on the study objective to compare the two modes of placental transfusion, infants exposed to ICC were not included in the analysis. The exclusion criteria were infants with missing exposure documentation; infants with severe congenital malformations, including those with congenital heart disease and/or genetic syndromes; infants who were alive at birth but did not receive active treatment in the form of ventilatory support, including continuous positive airway pressure, positive pressure ventilation (PPV), intubation, chest compressions or epinephrine administration, surfactant therapy or mechanical ventilation and parental nutrition after delivery as previously defined by Rysavy et al(17); and ) infants with documented exposure to both DCC and UCM.

The NRN GDB collects demographic, maternal, and neonatal information from birth until death, hospital discharge, or 120 days postnatal age using pre-specified definitions. (18–19) Antenatal steroid exposure was defined as the administration of at least one dose of any corticosteroid (dexamethasone or betamethasone) given during the present pregnancy. Pregnancy induced hypertension was defined as maternal blood pressure > 140 systolic or 90 diastolic. Rupture of membranes before onset of labor was defined as preterm premature rupture of membranes and rupture of membranes >18 hours was defined as prolonged rupture of membranes. Antepartum hemorrhage included placental previa, abruption or threatened abortion resulting in bleeding after 20 weeks. Gestational age was determined by best obstetric estimate based on ultrasonography and/or the date of the last menstrual period. Hypothermia was defined as temperature <36 degree Celsius. The Papile criteria were used to classify IVH, and severe IVH was defined as grade III and IV.(20) Cranial ultrasound performed closest to 36 weeks PMA was used to diagnose cystic periventricular leukomalacia (cPVL), which was defined by the presence of cystic echolucencies in the periventricular white matter, and ventriculomegaly, which was defined by the presence of enlarged ventricles. Severe brain injury was defined as presence of severe IVH, cPVL, porencephalic cyst or ventriculomegaly diagnosed on cranial ultrasound by the radiologist at each NRN center. Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) was defined as modified Bells stage IIA or greater.(21) Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) was limited to grade three BPD, infants requiring invasive mechanical ventilation at 36 weeks PMA as defined by Jensen et al.(22) This definition was chosen to identify infants with BPD severity that is most closely associated with death or serious respiratory morbidity. Late onset sepsis (≥ 72 postnatal hours) was defined by positive blood culture for bacteria or fungi and antibiotic therapy for greater than or equal to five days or intent to treat but death occurring before five days.(23–24) Severe retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) was defined as stage 4 disease or greater with ‘plus’ disease or ROP receiving treatment.(25)

The exposure of interest was UCM, and DCC exposure served as the reference group. Both were identified in the GDB registry using two yes/no questions: ) Is there documentation of cord milking? and Is there documentation of at least 30 seconds of delayed cord clamping?

The primary outcome was a composite outcome of mortality or severe IVH by 36 weeks’ PMA. Secondary outcomes were ) mortality by 36 weeks’ PMA; ) severe IVH in those surviving to 36 weeks’ PMA; any grade IVH or mortality by 36 weeks’ PMA; and a composite outcome of mortality or major morbidity diagnosed by 36 weeks’ PMA. Major morbidity was defined as severe brain injury, NEC, late onset sepsis, grade 3 BPD or severe ROP.

Statistical analyses

The NRN Data Coordinating Center (RTI International) performed the statistical analysis using the R statistical software version 3.5.1 (Feather Spray, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was established at P < .05. Exposure data were missing for <1% of the cohort which was handled using complete case analysis. Baseline maternal and neonatal characteristics were compared between infants exposed to UCM versus DCC using t-tests for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test for categorical variables. The risk-adjusted association of each mode of placental transfusion with each outcome was assessed using multivariable logistic regression. The following variables were incorporated into the final regression model risk factors for mortality identified a priori: sex, GA (in weeks), ANS exposure (no antenatal steroids or any antenatal steroids), and birth resuscitation (PPV, intubation in the delivery room, chest compressions and/or epinephrine administration)(19)(26–27); covariates that were statistically significantly imbalanced between the groups; and NRN center as a random effect.

A prespecified, exploratory analysis evaluated severe IVH in two GA strata, 22-246/7 and 25-286/7 weeks. Based on the publication of an interim study, a post-hoc, stratified analysis was conducted to understand the effect of mode of delivery and chorioamnionitis on the primary outcome of mortality or severe IVH by 36 weeks PMA.(16)

Results

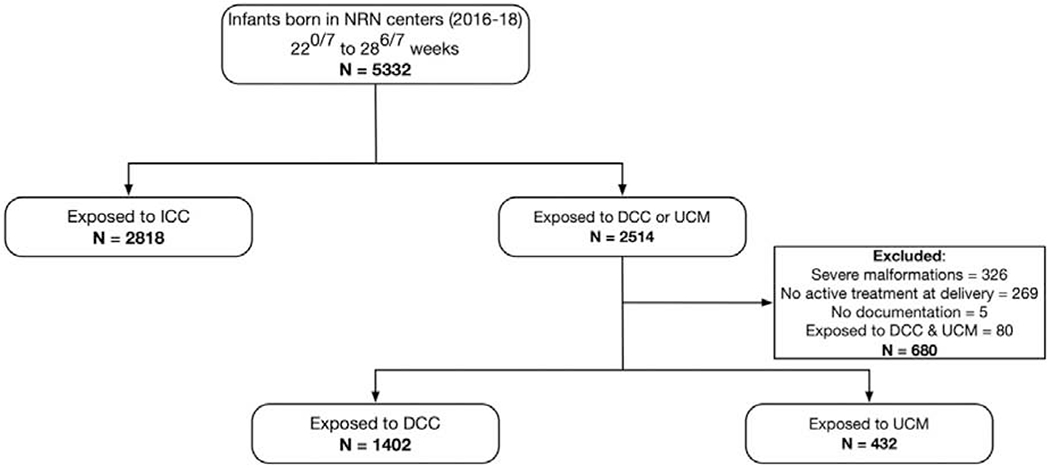

Between January 1st, 2016 and December 31st, 2018, 5,332 infants 220/7-286/7 weeks’ gestation were born in participating NRN centers and 2,514 infants were exposed to placental transfusion. After applying the exclusion criteria, 1,834 were included in the final analysis, of which 23.6% (n=432) were exposed to UCM and 76.4% (n=1,402) were exposed to DCC (Figure 1). Between 2016 to 2018, DCC was the primary mode of placental transfusion in the majority of centers (Figure 2). Maternal and neonatal characteristics that differed between the two groups were: race, maternal insurance, preterm premature rupture of membranes, maternal antibiotics, antepartum hemorrhage, mode of delivery, multiples, Apgar score ≤ 4 at 5 minutes, PPV, intubation, chest compressions, epinephrine, hypothermia on admission, and surfactant (Table I).

Figure 1. Study Flow Diagram.

Figure 2. Number of Infants Exposed to DCC or UCM per year (2016-2018) by Center.

The y-axis shows percentage of preterm infants exposed to DCC (blue) or UCM (orange) and the x-axis shows the NRN centers. The years are differentiated by the shading which gets darker with each subsequent year (e.g., light blue represents the number of DCC exposed infants in 2016 and the darkest blue the number of DCC exposed infants in 2018). Centers A, B, C, D were no longer a part of the NRN centers in 2017 and 2018.

Table 1:

Maternal and Neonatal Characteristics

| Characteristics | UCM (N = 432) | DCC (N = 1402) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Maternal age (years), mean (SD) | 28.8 (5.7) | 28.4 (6.1) | 0.17 |

| Race/Ethnicity | < 0.0001 | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 31 (7.2%) | 569 (40.6%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 252 (58.5%) | 592 (42.3%) | |

| Hispanic | 93 (21.6%) | 153 (10.9%) | |

| Asian | 24 (5.6%) | 51 (3.6%) | |

| Other | 29 (6.7%) | 26 (1.9%) | |

| Unknown/Not reported | 2 (0.5%) | 10 (0.7%) | |

| Maternal Insurance | < 0.0001 | ||

| Private | 620 (44.29%) | 241 (55.79%) | |

| Public | 744 (53.14%) | 148 (34.26%) | |

| Other | 36 (2.57%) | 43 (9.95%) | |

| Limited or no prenatal care | 37 (8.6%) | 150 (10.7%) | 0.24 |

| Received antenatal steroids** | 416 (96.3%) | 1359 (97.1%) | 0.42 |

| No steroids | 16 (3.7%) | 40 (2.9%) | 0.58 |

| Partial steroid course | 96 (22.4%) | 304 (21.8%) | |

| Complete steroid course | 317 (73.9%) | 1054 (75.4%) | |

| Antenatal MgSo4 | 398 (92.1%) | 1281 (91.6%) | 0.77 |

| Diabetes prior to pregnancy | 20 (4.6%) | 48 (3.5%) | 0.31 |

| Gestational diabetes | 20 (4.7%) | 69 (5.0%) | 0.90 |

| Hypertension during pregnancy | 112 (25.9%) | 414 (29.6%) | 0.16 |

| Pregnancy induced hypertension | 64 (14.8%) | 229 (16.3%) | 0.50 |

| Preterm premature rupture of membranes | 200 (46.6%) | 739 (53.0%) | 0.02 |

| Prolonged rupture of membranes | 117 (27.3%) | 390 (28.0%) | 0.81 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 194 (44.9%) | 712 (50.8%) | 0.04 |

| Maternal antibiotics | 385 (89.1%) | 1139 (81.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 116 (26.9%) | 220 (15.8%) | < 0.0001 |

| Cesarean delivery | 320 (74.1%) | 843 (60.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Neonatal characteristics | |||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 0.91 | ||

| 22 weeks | 0 (0%) | 39 (2.8%) | |

| 23 weeks | 43 (10%) | 99 (7.1%) | |

| 24 weeks | 54 (12.5%) | 165 (11.8%) | |

| 25 weeks | 71 (16.4%) | 202 (14.4%) | |

| 26 weeks | 64 (14.8%) | 251 (17.9%) | |

| 27 weeks | 84 (19.4%) | 284 (20.3%) | |

| 28 weeks | 116 (26.9%) | 362 (25.8%) | |

| GA in weeks (continuous), mean (SD) | 26.5 (1.7) | 26.4 (1.7) | 0.94 |

| Multiples | 143 (33.1%) | 340 (24.3%%) | <0.001 |

| Birth weight (grams), mean (SD) | 880.5 (247.9) | 873.1(247.2) | 0.65 |

| SGA | 37 (8.6%) | 125 (8.9%) | 0.92 |

| Male | 216 (50.0%) | 700 (49.9%) | 1.0 |

| Apgar scores | |||

| ≤4 at 1 minute | 236 (54.8%) | 669 (47.9%) | 0.01 |

| ≤4 at 5 minutes | 82 (19.0%) | 208 (14.9%) | 0.04 |

| Delivery room interventions | |||

| PPV | 378 (87.5%) | 1103 (78.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Intubation | 322 (74.5%) | 723 (51.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Chest compressions | 22 (5.1%) | 36 (2.6%) | 0.01 |

| Epinephrine | 13 (3.0%) | 21 (1.5%) | 0.06 |

| Admission temperature (degrees Celsius) | 36.5 (0.7) | 36.7 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Hypothermia on admission | 68 (16.0%) | 159 (11.4%) | 0.01 |

| Surfactant | 359 (84.9%) | 1011 (73.0%) | <0.0001 |

DCC = Delayed cord clamping, UCM = Umbilical cord milking, SD = Standard deviation, PPV = Positive pressure ventilation, SGA = Small for gestational age.

p-values based on t-test/Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and Fischer’s exact test for two level categorical variables, and for multi-level categorical variables a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel mean score test using rank scores performed.

Data presented as % for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous variables.

Data for ANS subgroup missing for one infant in the UCM exposed group.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The adjusted odds of mortality or severe IVH by 36 weeks PMA were not statistically different between the two groups (aOR 1.45, 95% CI 0.93, 2.26) (Table 2). UCM exposed infants had increased odds of severe IVH by 36 weeks PMA compared with DCC exposed infants (aOR 1.70, 95% CI 1.20, 2.43). The rates for the secondary composite outcome of mortality or major morbidity by 36 weeks PMA were not statistically different [75.1% in the UCM group and 57.3% in the DCC group (aOR 1.16, 95% CI 0.71, 1.89)]. The adjusted odds of the remaining secondary outcomes were also not significantly different (Table 2). There was a significant interaction (p = 0.001) by GA between UCM or DCC and the composite outcome of mortality or major morbidity (Figure 3; available at www.jpeds.com). The interaction by GA reflects infants ≥24 weeks gestation as none of the 22-week GA infants were exposed to UCM and 100% of 23-week GA infants exposed to UCM suffered from mortality or a major morbidity.

Table 2:

Neonatal outcomes among infants exposed to UCM versus DCC

| Outcomes | UCM (n = 432) | DCC (n = 1402) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | |||

| Composite of mortality or severe IVH at 36 weeks PMA | 122 (28.3%) | 266 (19.1%) | 1.45 (0.93, 2.26) |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||

| Mortality by 36 weeks PMA | 63 (14.6%) | 153 (10.9%) | 0.98 (0.52, 1.83) |

| Severe IVH by 36 weeks PMA | 82 (19.8%) | 159 (11.8%) | 1.70 (1.20, 2.43) |

| Severe IVH among 22-24 weeks (n = 400) | 34 (38.2%) | 80 (28.9%) | 1.19 (0.65, 2.19) |

| Severe IVH among 25-28 weeks (n = 1434) | 48 (14.8%) | 79 (7.4%) | 1.89 (1.22, 2.95) |

| Any IVH or mortality by 36 weeks’ PMA | 188 (43.6%) | 466 (33.5%) | 1.01 (0.45, 1.59) |

| Composite of mortality or major morbidity by 36 weeks’ PMA* | 319 (75.1%) | 774 (57.3%) | 1.16 (0.71, 1.89) |

| Other outcomes | |||

| Death < 12 hours | 9 (2.1%) | 17 (1.2%) | 1.47 (0.40, 5.39) |

| Hypotension therapy or mortality in 12 hours | 144 (33.3%) | 250 (17.8%) | 1.31 (0.73, 2.36) |

| Other outcomes, restricted to survivors of first 12 hours | |||

| Severe brain iniury | |||

| Severe IVH | 82 (19.8%) | 159 (11.8%) | 1.66 (1.07, 2.55) |

| Cystic PVL | 21 (5.1%) | 48 (3.5%) | 1.45 (0.80, 2.65) |

| Porencephalic cyst | 11 (2.6%) | 21 (1.5%) | 1.35 (0.53, 3.43) |

| Ventriculomegaly | 44 (10.4%) | 94 (6.8%) | 1.45 (0.94, 2.24) |

| NEC** | 38 (9.0%) | 121 (8.7%) | 1.04 (0.57, 1.90) |

| Severe BPD | 221 (60.7%) | 541 (44.1%) | 1.17 (0.71, 1.91) |

| Late onset sepsis | 68 (16.1%) | 232 (16.8%) | 0.94 (0.64,1.38) |

| Severe ROP*** | 30 (8.4%) | 99 (8.2%) | 0.86 (0.35, 2.12) |

| Length of stay mean (SD) | 86 (19.1) | 82 (19.9) | 0.62 (−2.94, 4.18) |

DCC = Delayed cord clamping, UCM=Umbilical cord milking, BPD Bronchopulmonary dysplasia, IVH = Intraventricular hemorrhage, PVL = Periventricular leukomalacia, NEC = Necrotizing enterocolitis, ROP = retinopathy of prematurity.

Data presented as n (%) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous varables.

Variables in the model include: GA, male, multiples, antenatal steroids (no antenatal steroid exposure or any antenatal steroid exposure), PPV, intubation, chest compressions and/or epinephrine, race, maternal insurance, preterm premature rupture of membranes, maternal antibiotics, antepartum hemorrhage, mode of delivery, hypothermia on admission, surfactant, and center as random effect.

Morbidities include severe brain injury, NEC, grade 3 BPD, late onset sepsis and severe ROP.

NEC stage II or greater

Severe ROP (stage 4 or requiring treatment)

Data presented as n (%) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous variables.

Figure 3. Raw and Adjusted Odds Ratio for Mortality or Severe Morbidity by Gestational Age.

Variables in the model include sex, antenatal steroids, positive pressure ventilation, intubation, resuscitation (PPV, intubation, chest compressions and/or epinephrine), race, 1-minute Apgar < = 4, antenatal hemorrhage, cesarean delivery, the interaction of GA and exposure to DCC or UCM, and center as a random effect.

Only infants ≥24 weeks gestation were included in the model as there were no 22-week infants exposed to UCM and 100% of 23-week infants exposed to UCM experienced mortality or major morbidity.

The four sites (A-D in Figure 1) that did not have exposed infants all three years were excluded from the model.

In our cohort there were no 22-week GA infants exposed to UCM. Beginning at 23 weeks GA, UCM exposed infants had higher rates of severe IVH compared with those exposed to DCC (Table 3; available at www.jpeds.com). In the 25-286/7-week stratum, UCM exposed infants had two times higher rates of severe IVH than infants exposed to DCC, (14.8% versus 7.3%, aOR 1.89 95% CI 1.22, 2.95) (Table 2). There was not a significant difference in the odds of severe IVH in the younger GA stratum (aOR 1.19 95% CI 0.65, 2.19).

Table 3:

Severe IVH stratified by GA and exposure.

| Infant exposed to UCM (N = 432) | Infants exposed to DCC (N = 1402) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe IVH (N = 82) | No Severe IVH (N = 332) | Severe IVH (N = 159) | No Severe IVH (N = 1192) | |

| 22 weeks | 0(NA) | 0(NA) | 10 (27.0%) | 27 (73.0%) |

| 23 weeks | 21 (52.5%) | 19 (47.5%) | 35 (40.2%) | 52 (59.7%) |

| 24 weeks | 13 (26.5%) | 36 (73.5%) | 35 (23.0%) | 118 (77.0%) |

| 25 weeks | 16 (22.5%) | 55 (77.5%) | 27 (13.8%) | 169 (86.2%) |

| 26 weeks | 14 (22.2%) | 49 (77.8%) | 26 (10.7%) | 217 (89.3%) |

| 27 weeks | 6 (7.9%) | 70 (92.1%) | 16 (5.7%) | 263 (94.3%) |

| 28 weeks | 12 (10.4%) | 103 (89.6%) | 10 (2.8%) | 346 (97.2%) |

DCC = delayed cord clamping, UCM = Umbilical cord milking, IVH = Intraventricular hemorrhage

Data presented as n (%) for categorical variables

An interim publication suggested an association of both mode of delivery and chorioamnionitis with severe IVH.(16) Therefore, the associations of both were assessed in a post-hoc analysis. The mode of delivery (aOR 1.26 95% CI 0.70, 2.28) and presence of maternal chorioamnionitis (aOR 1.20 95% CI 0.77, 1.89) were not associated with mortality or severe IVH by 36 weeks PMA among infants exposed to UCM (Table 4; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 4:

Stratified analysis by mode of delivery and chorioamnionitis

| UCM (n = 432) | DCC (n = 1402) | aOR (95% CI) | p value | p for interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of delivery | |||||

| Cesarean | 320 (74.1%) | 843 (60.1%) | 1.26 (0.70, 2.28) | 0.45 | 0.87 |

| Vaginal | 112 (25.9%) | 559 (39.9%) | 1.68 (0.95, 2.97) | 0.08 | |

| Chorioamnionitis | |||||

| Yes | 194 (44.9%) | 712 (50.8%) | 1.20 (0.77, 1.89) | 0.42 | 0.17 |

| No | 238 (55.1%) | 690 (49.2%) | 1.93 (1.00, 3.73) | 0.05 |

DCC = Delayed cord clamping, UCM = umbilical cord milking

Data presented as n (%) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous variables.

Variables in the model include: GA, male, multiples, antenatal steroids, PPV, intubation, chest compressions and/epinephrine, race, maternal insurance, preterm premature rupture of membranes, maternal antibiotics, antepartum hemorrhage, mode of delivery, hypothermia on admission, surfactant, and center as random effect.

Discussion

In this large, contemporary, observational study, UCM was not associated with the primary outcome of mortality or severe IVH by 36 weeks PMA but was associated with higher odds of the secondary outcome of severe IVH. These results are similar to the large randomized trial comparing DCC and UCM, which favored DCC.(16) Over the past three years in the NRN, DCC was the more frequently used mode of placental transfusion, as may be expected based on professional organizational guidelines.(3–6)

We previously reported that compared with ICC, infants exposed to any mode of placental transfusion had a lower odds of mortality.(28) The current study was motivated by the need to differentiate between the outcomes of infants exposed to DCC versus UCM. Although we did not find an association with the composite outcome of mortality or severe IVH, the key finding of the current study was a statistically significant and clinically relevant increased odds of severe IVH following UCM exposure. This signal persisted in the stratified analysis of infants 250/7–286/7 weeks but not in the 220/7–246/7-week subgroup. The high rate of severe IVH among infants in the 220/7–246/7-week subgroup, regardless of exposure to UCM or DCC, in combination with the small sample size (n = 400) may have contributed to our inability to detect a difference in this stratum. Findings from our observational study are similar to the results of a recent trial comparing the two placental transfusion modalities, which was stopped early due to high rates of severe IVH among infants randomized to UCM.(16) Additionally, these findings parallel those reported in the Canadian Neonatal Network, which similarly found higher rates of severe IVH among infants exposed to UCM compared with DCC.(29)

In our cohort, 13% of infants had severe IVH, which is similar to the previously reported rates of 16% among extremely premature infants. (30–31) As expected, rates of severe IVH were higher among infants with lower gestational age (Table 3). The inverse relationship between gestational age and severe IVH risk has been attributed to limited cerebral autoregulation, capillary fragility, and fluctuations in cerebral blood flow.(32) Animal data show that UCM causes large oscillating swings in both arterial pressure and cerebral blood flow, further increasing fluctuations in cerebral perfusion.(33) The combination of extreme immaturity and large oscillating swings in arterial pressure and cerebral blood flow secondary to UCM are likely contributing to the increase in severe IVH.

The majority of trials comparing UCM and DCC have either concentrated on establishing the safety profile for UCM or were powered to determine the effect on hemodynamics.(8–11) Four trials that assessed IVH as an outcome were small, with a median enrollment of 106 infants (range 40-474).(12–16) The largest trial was prematurely stopped after enrolling 474 of the planned 1,500 infants due to increased rates of severe IVH in the UCM group.(16) Although not a clinical trial, our study adds to the growing body of evidence for DCC over UCM as the preferred method of placental transfusion. Compared with DCC, UCM allows for quick placental transfusion in order to initiate resuscitation soon after birth. However, the potential for neurologic injury and harm associated with UCM may outweigh the benefits of early resuscitation. Additionally, trials across the world are examining the ability to perform DCC with concurrent resuscitation (e.g. VentFirst NCT02742454, Baby DUCC Australian Trial Registry 1261800621213). If feasible and successful, these trials may provide further support for DCC as the optimal approach to placental transfusion.

Despite current recommendations, there was some variation in the application of approaches to cord management and placental transfusion over the study period (Figure 2). Two centers used UCM as their primary mode of placental transfusion whereas most other centers used DCC. These data were collected before 2019 and we hypothesize that placental transfusion across NRN centers today may be changing in response to the increasing evidence of harm after exposure to UCM. Neuro-centric care practices for extremely preterm infants vary between units, which may also influence outcomes.(34) To account for unmeasured differences, we included center as a random effect in our model; however, by itself it is unlikely to account for all variations in clinical practice which may contribute to our findings.

We pursued a post-hoc analysis to examine 2 additional risk factors (chorioamnionitis and mode of delivery) associated with severe IVH. A meta-analysis in 2018 reported that chorioamnionitis is a risk factor for IVH.(35) The inflammatory response seen with chorioamnionitis results in an increase of cytokines that cause hemodynamic alterations and systemic vasculitis, which both increase the risk for IVH.(36–37) In our stratified analysis, the presence of chorioamnionitis did not affect the exposure and primary composite outcome relationship. Previous studies have also reported that infants born via vaginal delivery are at increased risk of IVH.(38) A similar stratified analysis found that the mode of delivery had no effect on the relationship between placental transfusion and the primary composite outcome. This study was not powered for these analyses and we examined the primary composite outcome, not severe IVH alone, both of which may contribute to the absence of a detectable association.

This study has the following limitations. Retrospective studies are subject to inherent methodological limitations leading to unmeasured covariate imbalances and non-differential biases which cannot be corrected in the analysis. Therefore, this observational study cannot infer causation; however, it does demonstrate an association between UCM exposure and severe IVH. Differences in the 5-minute Apgar scores in our bivariate analysis suggest that the subset of infants exposed to UCM required more resuscitation and may have been exposed to UCM in order to expediate initiation of resuscitation. This scenario leads to confounding by indication, or treatment-selection bias, which could persist despite model adjustments and influence study results.(39) Although data missingness in the GDB is quite low, infants with incomplete data (eg, missing exposure or outcome data) were excluded which leads to selection bias. Another limitation of the dataset is the lack of granular data surrounding placental transfusion; details regarding the duration of the delay, type of UCM (intact vs cut), the number of times the cord was milked or timing of the onset of infant breathing are not available. The UCM group was much smaller than the DCC group and such comparisons are subject to type 1 error. Finally, large databases that utilize data from multiple centers highlight clinical practice variation, which could either exaggerate or mask study findings.

Although utilizing a database has several limitations, it also has several strengths. The NRN GDB is a robust database which includes multiple centers across the United States. From 2016 to 2018, the NRN GDB provided 1,834 infants for assessment, making this one of the larger studies comparing outcomes following placental transfusion. A recently published retrospective study from the Canadian Neonatal Network included 394 infants in UCM group and 4,419 in the DCC group with similar findings.(29) Although the Canadian Neonatal Network’s study reflects a larger cohort, the generalizability differs from this study as it includes infants < 33 weeks GA and the organization and regionalization of extremely preterm care delivery between Canada and the United States are not the same. Thus, our findings from the NRN may more accurately reflect outcomes in clinical practice in the United States. Previous cohort studies have not exclusively focused on extremely premature infants and randomized trials have inconsistently included infants less than 24 weeks’ gestation, populations at high risk for adverse neurologic outcomes. Given that UCM exposure was associated with an adverse event as serious as severe IVH, caution should be exercised before considering use of UCM as a mode of placental transfusion.

In conclusion, in this large, contemporary, observational study comparing short-term outcomes among infants < 29 weeks’ gestation following DCC or UCM exposure, UCM was not associated with improvements in the primary composite outcome of mortality or severe IVH and was associated with an increase in the adverse outcome of severe IVH. Although UCM-exposed infants were likely sicker, the association of UCM with severe IVH is similar to the largest randomized trial comparing DCC and UCM, which also favored DCC. Results of this study add to the emerging literature surrounding placental transfusion modalities and outcomes and provide complementary data to published clinical trials. Future studies describing long term neurodevelopmental outcomes following placental transfusion are required.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study. We acknowledge the contributions of the other investigators (Appendix) who participated in this study.

The National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) provided grant support for the Neonatal Research Network’s Generic Database Study through cooperative agreements. While NICHD staff had input into the study design, conduct, analysis, and manuscript drafting, the comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent the views of NICHD, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the U.S. Government. Participating NRN sites collected data and transmitted it to RTI International, the data coordinating center (DCC) for the network, which stored, managed and analyzed the data for this study. On behalf of the NRN, RTI International had full access to all of the data in the study, and with the NRN Center Principal Investigators, takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of Abbreviations

- GA

gestational age

- PMA

postmenstrual age

- IVH

intraventricular hemorrhage

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- NICHD

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- NRN

Neonatal Research Network

- GDB

Generic Database

- cPVL

cystic periventricular leukomalacia

- BPD

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- NEC

necrotizing enterocolitis

- ROP

retinopathy of prematurity

Appendix

Additional members of the Generic Database Subcommittee of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network:

NRN Steering Committee Chair: Richard A. Polin, MD, Division of Neonatology, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, (2011-present).

Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (UG1 HD27904) – Abbot R. Laptook, MD; Martin Keszler, MD; Angelita M. Hensman, PhD RNC-NIC; Elisa Vieira, BSN RN; Lucille St. Pierre, BS.

Case Western Reserve University, Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital (UG1 HD21364) – Anna Maria Hibbs, MD MSCE.

Children’s Mercy Hospital, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine and Kansas University Medical Center (U10 HD68284) – William E. Truog, MD; Eugenia K. Pallotto, MD MSCE; Prabhu S. Parimi, MD; Cheri Gauldin, RN BSN CCRC; Anne Holmes, RN MSN MBA-HCM CCRC; Allison Knutson, BSN RNC-NIC; Lisa Gaetano, RN MSN.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, and Good Samaritan Hospital (UG1 HD27853, UL1 TR77) – Brenda B. Poindexter, MD MS; Kurt Schibler, MD; Stephanie L. Merhar, MD MS; Cathy Grisby, BSN CCRC; Kristin Kirker, CRC.

Duke University School of Medicine, University Hospital, University of North Carolina, Duke Regional Hospital, and WakeMed Health and Hospitals (UG1 HD40492, UL1 TR1117, UL1 TR1111) – C. Michael Cotten, MD MHS; Ronald N. Goldberg, MD; Joanne Finkle, RN JD; Kimberley A. Fisher, PhD FNP-BC IBCLC; Matthew M. Laughon, MD MPH; Carl L. Bose, MD; Janice Bernhardt, MS RN; Gennie Bose, RN; Cindy Clark, RN; Stephen D. Kicklighter, MD; Ginger Rhodes-Ryan, ARNP MSN NNP-BC; Donna White, BSN RN-BC.

Emory University, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Grady Memorial Hospital, and Emory University Hospital Midtown (UG1 HD27851, UL1 TR454) – David P. Carlton, MD; Ravi M. Patel, MD; Yvonne Loggins, RN; Colleen Mackie, BS RT; Diane I. Bottcher, RN MSN.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development – Andrew A. Bremer, MD PhD; Rosemary D. Higgins, MD; Stephanie Wilson Archer, MA.

Indiana University, University Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Riley Hospital for Children at Indiana University Health, and Eskenazi Health (U10 HD27856, UL1 TR6) – Gregory M. Sokol, MD; Dianne E. Herron, RN CCRC.

McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, Memorial Hermann Southwest Hospital (UG1 HD87229) – Jon E. Tyson, MD MPH; Amir M. Khan, MD; Kathleen A. Kennedy, MD MPH; Claudia Pedrozza, PhD; Elizabeth Eason, MD, Emily K. Stephens, BSN RNC-NIC; Georgia E. McDavid, RN; Karen Martin, RN; Donna Hall, RN; Sharon L. Wright, MT.

Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Center for Perinatal Research, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Riverside Methodist Hospital (U10 HD68278) – Pablo J. Sánchez, MD; Leif D. Nelin, MD; Sudarshan R. Jadcherla, MD; Patricia Luzader, RN; Erna Clark, BA; Julie Gutentag, RN; Courtney Park, RN BSN; Julie C. Shadd, BSN RD; Melanie Stein, RRT BBA; Hallie Baugher, BS MSN; Jacqueline McCool.

RTI International (U10 HD36790) – Marie G. Gantz, PhD; Carla M. Bann, PhD; Dennis Wallace, PhD; Kristin M. Zaterka-Baxter, RN BSN CCRP; Jenna Gabrio, MPH CCRP; David Leblond, BS; Jeanette O’Donnell Auman, BS.

Stanford University and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital (UG1 HD27880, UL1 TR93) – David K. Stevenson, MD; Valerie Y. Chock, MD MS Epi; M. Bethany Ball, BS CCRC; Melinda S. Proud, RCP; Elizabeth N. Reichert, MA CCRC, R. Jordan Williams, BA.

University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System and Children’s Hospital of Alabama (UG1 HD34216) – Waldemar A. Carlo, MD; Namasivayam Ambalavanan, MD; Monica V. Collins, RN BSN MaEd; Shirley S. Cosby, RN BSN; Tara McNair, RN BSN.

University of California - Los Angeles, Mattel Children’s Hospital, Santa Monica Hospital, Los Robles Hospital and Medical Center, and Olive View Medical Center (U10 HD68270) – Uday Devaskar, MD; Meena Garg, MD; Teresa Chanlaw, MPH; Rachel Geller, RN BSN.

University of Iowa, Mercy Medical Center, and Sanford Health (UG1 HD53109, M01 RR59, UL1 TR442) – Edward F. Bell, MD; Tarah T. Colaizy, MD MPH; Dan L. Ellsbury, MD; Michelle L. Baack, MD; Karen J. Johnson, RN BSN; Mendi L. Schmelzel, RN MSN; Jacky R. Walker, RN; Claire A. Goeke, RN; Tracy L. Tud, RN; Chelsey Elenkiwich, RN BSN; Megan M. Henning, RN; Megan Broadbent, RN BSN; Laurie A. Hogden, MD; Jane E. Brumbaugh, MD; Jonathan M. Klein, MD; John M. Dagle, MD PhD.

University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UG1 HD53089, UL1 TR41) – Janell Fuller, MD; Robin K. Ohls, MD; Sandra Sundquist Beauman, MSN RNC-NIC; Conra Backstrom Lacy, RN; Carol Hartenberger, RN MPH; Mary Hanson, RN BSN; Elizabeth Kuan, RN BSN.

University of Pennsylvania, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Hospital, and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (UG1 HD68244) – Eric C. Eichenwald, MD; Barbara Schmidt, MD MSc; Haresh Kirpalani, MB MSc; Soraya Abbasi, MD; Christine Catts, CRNP; Aasma S. Chaudhary, BS RRT; Sarvin Ghavam, MD; Toni Mancini, RN BSN CCRC; Jonathan Snyder, RN BSN.

University of Rochester Medical Center, Golisano Children’s Hospital, and the University at Buffalo John R. Oishei Children’s Hospital of Buffalo (UG1 HD68263, UL1 TR42) – Carl T. D’Angio, MD; Ronnie Guillet, MD PhD; Anne Marie Reynolds, MD MPH; Holly I.M. Wadkins, MA; Michael G. Sacilowski, MAT CCRC; Mary Rowan, RN; Rosemary L. Jensen; Deanna Maffett, RN; Diane Prinzing, AAS; Ann Marie Scorsone, MS CCRC; Kyle Binion, BS; Stephanie Guilford, BS; Constance Orme; Premini Sabaratnam, MPH; Daisy Rochez, BS MHA; Emily Li, BA; Jennifer Donato, BS; Satyan Lakshminrusimha, MD; Rachel Jones.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Parkland Health & Hospital System, and Children’s Medical Center Dallas (UG1 HD40689) – Luc P. Brion, MD; Maria M. DeLeon, RN BSN; Frances Eubanks, RN BSN; Pollieanna Sepulvida, RN; Diana M. Vasil, MSN RNC-NIC BSN.

University of Utah Medical Center, Intermountain Medical Center, McKay-Dee Hospital, Utah Valley Hospital, and Primary Children’s Medical Center (UG1 HD87226, UL1 TR105) – Bradley A. Yoder, MD; Mariana Baserga, MD MSCI; Stephen D. Minton, MD; Mark J. Sheffield, MD; Carrie A. Rau, RN BSN CCRC; Jill Burnett, RNC BSN; Brandy Davis, RN; Susan Christensen, RN; Manndi C. Loertscher, BS CCRP; Trisha Marchant, RNC; Earl Maxson, RN CCRN; Kandace McGrath; Jennifer O. Elmont, RN BSN; Melody Parry, RN; Susan T. Schaefer, RN, BSN, RRT; Kimberlee Weaver-Lewis, RN MS; Kathryn D. Woodbury, RN BSN.

Wayne State University, Hutzel Women’s Hospital and Children’s Hospital of Michigan (U10 HD21385) – Seetha Shankaran, MD; Girija Natarajan, MD; Sanjay Chawla, MD; Kirsten Childs, RN BSN; Bogdan Panaitescu, MD; John Barks, MD; Diane F. White, RRT CCRP.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Portions of this study were presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies webinar series, June 19, 2020 (virtual).

Data Sharing: Data reported in this paper may be requested through a data use agreement. Further details are available at https://neonatal.rti.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=DataRequest.Home.

References:

- 1.Nagano N, Saito M, Sugiura T, Miyahara F, Namba F, Ota E. Benefits of umbilical cord milking versus delayed cord clamping on neonatal outcomes in preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018; August 30 3: e0201528 10.1371/journal.pone.0201528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabe H, Gyte GM, Díaz-Rossello JL, Duley L. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping and other strategies to influence placental transfusion at preterm birth on maternal and infant outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019; 9 Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD003248.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 684: Delayed umbilical cord clamping after birth. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129: e5–10. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Pediatrics. Timing of umbilical cord clamping after birth. Pediatrics 2013; April 1;131: e1323–e1323. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-0191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perlman JM, Wyllie J, Kattwinkel J, Wyckoff MH, Aziz K, Guinsburg R, et al. Part 7: Neonatal Resuscitation: 2015 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations (Reprint). Pediatrics 2015; November 1;136: S120–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3373D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roehr CC, Hansmann G, Hoehn T, Bührer C. The 2010 Guidelines on Neonatal Resuscitation (AHA, ERC, ILCOR): similarities and differences--what progress has been made since 2005? Klin Padiatr 2011; September; 223:299–307. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katheria AC. Umbilical cord milking: A review. Front Pediatr 2018; 6:335. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song SY, Kim Y, Kang BH, Yoo HJ, Lee M. Safety of umbilical cord milking in very preterm neonates: a randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2017; 60:527–534. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.6.527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ram Mohan G, Shashidhar A, Chandrakala BS, Nesargi S, Suman Rao PN. Umbilical cord milking in preterm neonates requiring resuscitation: A randomized controlled trial. Resuscitation 2018; 130:88–91. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lago Leal V, Pamplona Bueno L, Cabanillas Vilaplana L, Nicolas Montero E, Martin Blanco M, Fernandez Romero C et al. Effect of milking maneuver in preterm infants: A Randomized controlled trial. Fetal Diagn Ther 2019; 45:57–61. doi: 10.1159/000485654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirk SK, Manolis SA, Lambers DS, Smith KL. Delayed clamping vs milking of umbilical cord in preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019; May;220: 482.e1–482.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.01.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosono S, Mugishima H, Fujita H, Hosono A, Minato M, Okada T, et al. Umbilical cord milking reduces the need for red cell transfusions and improves neonatal adaptation in infants born at less than 29 weeks’ gestation: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2008; January;93: F14–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.108902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabe H, Jewison A, Alvarez RF, Crook D, Stilton D, Bradley R, et al. Milking compared with delayed cord clamping to increase placental transfusion in preterm neonates: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2011; Feb; 117:205–11. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fe46ff [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katheria AC, Truong G, Cousins L, Oshiro B, Finer NN. Umbilical cord milking versus delayed cord clamping in preterm infants. Pediatrics 2015; July 1; 136:61–9.doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran C, Parucha J, Jegatheesan P, Lee H. Delayed cord clamping and umbilical cord milking among infants in California neonatal intensive care units. Am J Perinatol 2019; March 21;s-0039-1683876. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1683876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katheria A, Reister F, Essers J, Mendler M, Hummler H, Subramaniam A, et al. Association of umbilical cord milking vs delayed umbilical cord clamping with death or severe intraventricular hemorrhage among preterm infants. JAMA 2019; November 19;322:1877. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, Das A, Hintz SR, Stoll BJ, et al. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2015; May 7;372:1801–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fanaroff AA, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, Stark AR, et al. Trends in neonatal morbidity and mortality for very low birthweight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007; February 196: 147.e1–147.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Survey of morbidity and mortality among high-risk preterm infants (GDB). Manual of operations. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papile L-A, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: A study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr 1978; April 92:529–34. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80282-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, Keating JP, Marshall R, Barton L, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg 1978; January 187:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197801000-00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen EA, Dysart K, Gantz MG, McDonald S, Bamat NA, Keszler M, et al. The diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very preterm infants: An evidence-based approach. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; April 17; rccm.201812–2348OC. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201812-2348OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, Lemons JA, et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: The experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2002; August 1; 110:285–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardy RJ, Good WV, Dobson V, Palmer EA, Phelps DL, Quintos M, et al. Multicenter trial of early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity: study design. Controlled Clin Trials 2004; June; 25:311–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Revised Indications for the Treatment of Retinopathy of Prematurity: Results of the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2003; 121:13. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.12.1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wyckoff MH, Salhab WA, Heyne RJ, Kendrick DE, Stoll BJ, Laptook AR. Outcome of extremely low birth weight infants who received delivery room cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Pediatr 2012; February 160:239–244.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Handley SC, Sun Y, Wyckoff MH, Lee HC. Outcomes of extremely preterm infants after delivery room cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a population-based cohort. J Perinatol 2015; May 35:379–83. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumbhat N, Eggleston B, Davis AS, Van Meurs KP, Demauro SB, Foglia EE, et al. Placental transfusion and short-term outcomes among extremely preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2020; fetalneonatal-2019-318710. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2019-318710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Naggar W, Afifi J, Dorling J, Bodani J, Cieslak Z, Canning R, et al. A Comparison of Strategies for Managing the Umbilical Cord at Birth in Preterm Infants. J Pediatr 2020; May S0022347620306041. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Walsh MC, et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2010; 126:443–456. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szpecht D, Szymankiewicz M, Nowak I, Gadzinowski J. Intraventricular hemorrhage in neonates born before 32 weeks of gestation—retrospective analysis of risk factors. Childs Nerv Syst 2016; August 1; 32:1399–404. doi: 10.1007/s00381-016-3127-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen KA. Treatment of intraventricular hemorrhages in premature infants: Where is the evidence? Adv Neonatal Care 2013; April; 13:127–30. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e31828ac82e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blank DA, Polglase GR, Kluckow M, Gill AW, Crossley KJ, Moxham A, et al. Haemodynamic effects of umbilical cord milking in premature sheep during the neonatal transition. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2018; November;103: F539–46. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Handley SC, Passarella M, Lorch SA, Lee HC. Survey of preterm neuro-centric care practices in California neonatal intensive care units. J Perinatol 2019; February; 39:256–62. doi: 10.1038/s41372-018-0283-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villamor-Martinez E, Fumagalli M, Mohammed Rahim O, Passera S, Cavallero G, Degraeuwe P et al. Chorioamnionitis is a risk factor for intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants: A Systematic review and meta-analysis [published correction appears in Front Physiol. 2019 Feb 15;10:102]. Front Physiol 2018; 9:1253. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yanowitz TD, Ann Jordan J, Gilmour CH, Towbin R, Bowen A, Roberts JM, et al. Hemodynamic disturbances in premature infants born after chorioamnionitis: Association with cord blood cytokine concentrations. Pediatr Res 2002; March; 51:310–6. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200203000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoon BH, Romero R, Yang SH, Jun JK, Kim I-O, Choi J-H, et al. Interleukin-6 concentrations in umbilical cord plasma are elevated in neonates with white matter lesions associated with periventricular leukomalacia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; May 1; 174:1433–40. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70585-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Humberg A, Härtel C, Paul P, Hanke K, Bossung V, Hartz A, et al. Delivery mode and intraventricular hemorrhage risk in very-low-birth-weight infants: Observational data of the German Neonatal Network. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017; May; 212:144–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haneuse S Distinguishing selection bias and confounding bias in comparative effectiveness research: Med Care 2016; April;54: e23–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.