Abstract

Stroke-related damage to the crossed lateral corticospinal tract causes motor deficits in the contralateral (paretic) limb. To restore functional movement in the paretic limb, the nervous system may increase its reliance on ipsilaterally descending motor pathways, including the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract, the reticulospinal tract, the rubrospinal tract, and the vestibulospinal tract. Our knowledge about the role of these pathways for upper limb motor recovery is incomplete, and even less is known about the role of these pathways for lower limb motor recovery. Understanding the role of ipsilateral motor pathways to paretic lower limb movement and recovery after stroke may help improve our rehabilitative efforts and provide alternate solutions to address stroke-related impairments. These advances are important because walking and mobility impairments are major contributors to long-term disability after stroke, and improving walking is a high priority for individuals with stroke. This perspective highlights evidence regarding the contributions of ipsilateral motor pathways from the contralesional hemisphere and spinal interneuronal pathways for paretic lower limb movement and recovery. This perspective also identifies opportunities for future research to expand our knowledge about ipsilateral motor pathways and provides insights into how this information may be used to guide rehabilitation.

Keywords: stroke rehabilitation, motor activity, lower extremity

Overview

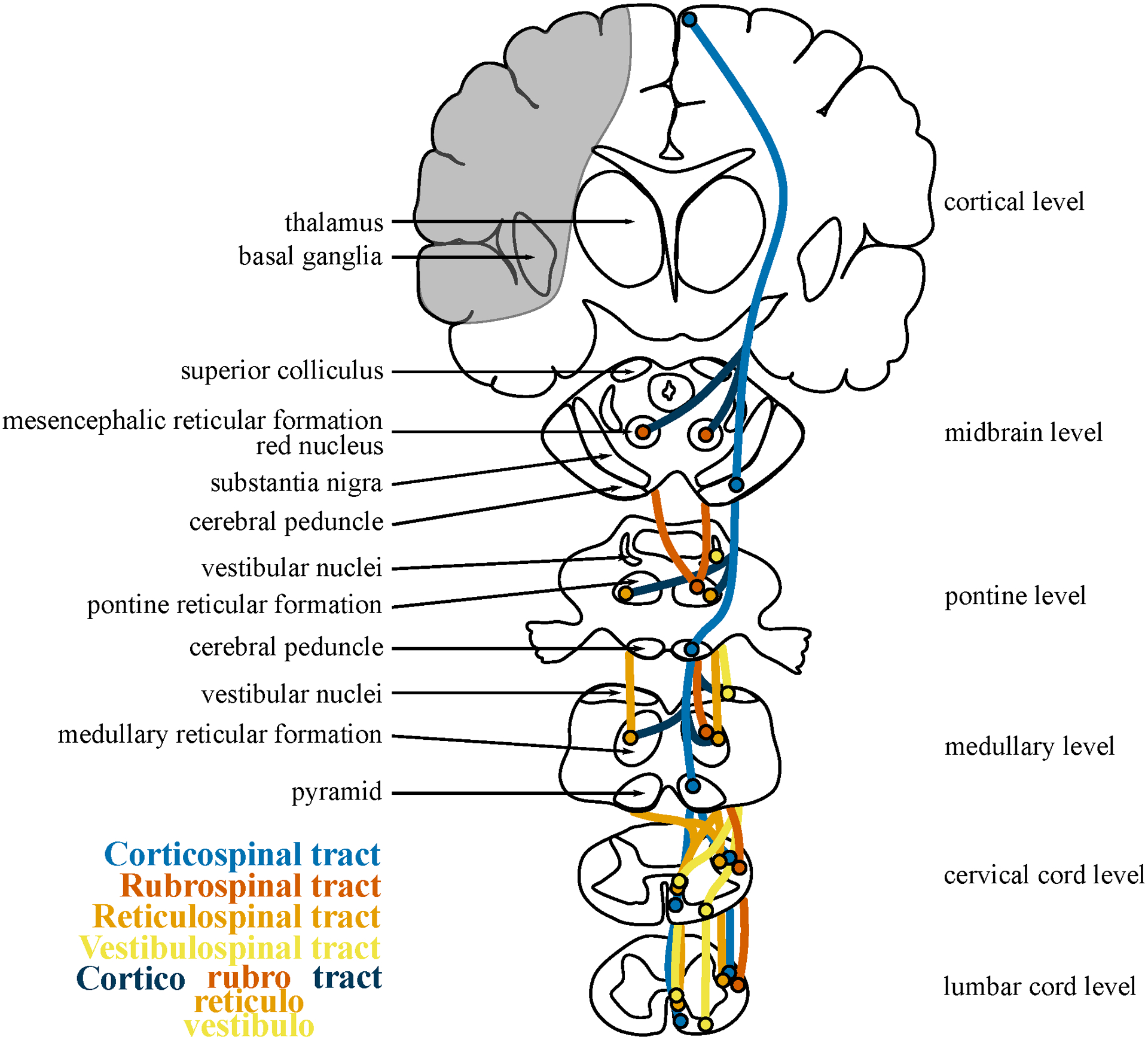

In humans, the crossed lateral corticospinal tract is one of the primary descending pathways contributing to movement (Porter & Lemon, 1993). Stroke often impacts the crossed lateral CST originating from the ipsilesional hemisphere by damaging the tract or neighboring networks. The disruption of motor signals through this crossed pathway results in motor deficits in the contralateral (paretic) upper and lower limbs (Porter & Lemon, 1993). To restore functional movement in the paretic limb, the nervous system may increase its reliance on other motor pathways, including those that descend ipsilaterally from the contralesional hemisphere (Jankowska & Edgley, 2006). One such pathway is the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract, consisting of fibers that descend ipsilaterally instead of crossing contralaterally with most of the lateral corticospinal tract. Ipsilateral projections from non-corticospinal tract pathways originating in the contralesional hemisphere may also contribute to movement in the paretic limb (Jankowska & Edgley, 2006). These tracts include the reticulospinal, rubrospinal, and vestibulospinal tract, with or without input from cortical sources (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Potential ipsilateral motor pathways to the paretic limb after stroke.

Displayed are potential ipsilateral projections of the corticospinal tract (lateral and anterior), rubrospinal tract, reticulospinal tract, and vestibulospinal tract. The cortical projections to the red nucleus, reticular formation, and vestibular nuclei are shown, which form the corticorubrospinal tract, corticoreticulospinal, and corticovestibulospinal tract. Double crossed pathways for the rubrospinal and reticulospinal tracts are also shown. Labeled are major structures, particularly those relevant to these motor pathways at four brain levels and two spinal cord levels. The gray shaded area represents an example case of a stroke of the middle cerebral artery. The courses of the displayed tracts are approximate and point estimates of broad distribution areas, and some tracts may not actually descend to all spinal levels.

Although there has been some interest in the role of ipsilateral motor pathways to paretic limb movement after stroke, most investigations have focused on the upper limb (Alawieh, Tomlinson, Adkins, Kautz, & Feng, 2017; Bradnam, Stinear, & Byblow, 2013). Our knowledge about the potential role of these pathways for upper limb motor recovery is incomplete, and even less is known about the role of these pathways for lower limb motor recovery. There may be less information about the lower limb because it often has better functional recovery from stroke than the upper limb (Desrosiers et al., 2003), likely because of reduced cortical and increased brainstem and spinal control (Yang & Gorassini, 2006) and because lower limb movements allow greater functional recovery through compensation. There also are limitations to using neurophysiological tools to evaluate ipsilateral motor pathways to the lower limb (Kesar, Stinear, & Wolf, 2018; Logothetis, 2008), and the contribution of individual pathways to the lower limb is dynamic and influenced by various factors, including time since stroke, stroke severity, stroke location, and lesion size. Despite these limitations, learning more about the ipsilateral motor pathways that contribute to lower limb movement after stroke is possible and is important. Walking and mobility impairments are major contributors to long-term disability after stroke (Gresham et al., 1975), and improving walking is a high priority for many stroke survivors (R. W. Bohannon, Andrews, & Smith, 1988). An enhanced understanding of the role of ipsilateral motor pathways to the lower limb can help improve our rehabilitative efforts and provide alternate solutions to address stroke-related impairments. In this perspective paper, we discuss potential contributions of ipsilateral motor pathways from the contralesional hemisphere and spinal interneuronal pathways to paretic lower limb movement. Although the focus of this paper is on the lower limb, upper limb literature is referenced in cases where little or no evidence is available for the lower limb. In this paper, we also provide insights into how this evidence can be translated into new rehabilitative strategies and discuss opportunities for future research.

Crossed (contralateral) lateral corticospinal tract

The crossed lateral corticospinal tract receives inputs from the primary motor cortex (M1), supplementary motor area (SMA), premotor cortex (PMC), and primary somatosensory cortex (S1) (Porter & Lemon, 1993). This tract descends through the internal capsule and crosses to the contralateral side of the body in the medulla. These projections have direct and indirect connections with upper limb and lower limb motor neurons in the lateral spinal cord, as well as many other connections, including with subcortical structures (Porter & Lemon, 1993).

The crossed lateral corticospinal tract has an important contribution to movement and recovery in the contralateral paretic lower limb. Several studies using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) have found that lower limb functional impairments (Motricity Index, Barthel Index, and Functional Ambulation Scale) are worse in those with greater impairment of the crossed lateral corticospinal tract (lesioned hemisphere to paretic limb) (Imura et al., 2015; Jang et al., 2008; B. R. Kim, Moon, Kim, Jung, & Lee, 2016; E. H. Kim, Lee, & Jang, 2013). Lower limb motor, functional, and walking recovery are impaired in individuals lacking contralateral responses to transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in paretic muscles (Chang, Do, & Chun, 2015; Hendricks, Pasman, van Limbeek, & Zwarts, 2003; B. R. Kim et al., 2016; Steube, Wietholter, & Correll, 2001). These findings have been demonstrated in individuals with a variety of stroke severities, locations, and lesion sizes.

Despite the importance of the crossed lateral corticospinal tract for lower limb movement and recovery after stroke, other studies question the importance of this tract. Functional movements such as walking are present in individuals with chronic stroke even when the crossed lateral corticospinal tract to the paretic limb is completely destroyed (Ahn, Ahn, Kim, Hong, & Jang, 2006; Cho et al., 2012; Hong, Kim, & Kim, 2016). The extent to which a stroke lesion impacts the crossed lateral corticospinal tract is not predictive of walking speed (Dawes et al., 2008) or change in walking speed with treadmill rehabilitative training in individuals with chronic subcortical stroke (Seo et al., 2014). Similarly, the presence or absence of contralateral responses to TMS in the paretic lower limb is not associated with walking speed in individuals with chronic stroke (Sivaramakrishnan & Madhavan, 2018). As an animal correlate, monkeys recover locomotor and foot grasping abilities even after complete lesions of the crossed lateral corticospinal tract at the thoracic level (Courtine et al., 2005). It is important to note that the recovery of locomotor movements in the lower limb may reflect the development of compensation and not recovery of the original movement through alternative pathways (Levin, Kleim, & Wolf, 2009). Nevertheless, these findings suggest that lower limb movement and recovery in the paretic limb after stroke may be partially controlled by motor pathways besides the crossed lateral corticospinal tract.

General evidence for ipsilateral motor pathways

Neuroimaging studies support the potential role of alternative motor pathways, particularly ipsilateral pathways, to movement and recovery of the lower limb after stroke. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have reported enhanced activation in the contralesional (ipsilateral) hemisphere during paretic knee flexion and extension (Jang et al., 2005; Y. H. Kim et al., 2006; Luft et al., 2005) and paretic ankle dorsiflexion (Enzinger et al., 2009; Enzinger et al., 2008; MacIntosh et al., 2008). Activation of the ipsilesional (ipsilateral) hemisphere is less extensive during movements of the non-paretic limb, as is ipsilateral activation during unilateral movements in controls. Contralesional regions showing increased activation during paretic lower limb movement include M1, S1, SMA, PMC, secondary somatosensory cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and thalamus. These changes in brain activation have been observed in individuals with variable stroke chronicity, severity, location, and lesion size. Although most of these studies do not implicate specific ipsilateral motor pathways, Luft et al. (2008) found that brain activation during paretic knee flexion and extension increases in the bilateral red nucleus after treadmill-training rehabilitation in chronic stroke, suggesting an increased activation of the contralesional reticulospinal tract. Studies using functional near infrared spectroscopy have found similar patterns of activation during walking in subacute stroke; brain activation is greater in the contralesional M1, S1, SMA, pre-SMA, and PMC than in the ipsilesional hemisphere (Miyai et al., 2003; Miyai et al., 2002). Overall, increased activation of the contralesional hemisphere may reflect an increased contribution of ipsilaterally descending motor pathways to movement of the paretic limb after stroke, both in a unilateral and bilateral context. However, the link between brain activation and contribution to motor control is not clear; increased activation of the contralesional hemisphere also may reflect intracortical processes, compensatory movements, or mirror movements in the non-paretic limb (Krakauer, 2007; Logothetis, 2008).

It is also unclear whether upregulation of ipsilateral motor pathways from the contralesional hemisphere is beneficial to functional recovery after stroke. A few studies have found that greater contralesional brain activation is associated with worse functional outcomes (Enzinger et al., 2008; Y. H. Kim et al., 2006). This is supported by longitudinal investigations which have found that functional activation tends to shift back towards the ipsilesional hemisphere as individuals progress into the chronic stage of stroke (Y. H. Kim et al., 2006; Miyai et al., 2003). This shift in activation has been associated with improved walking function. These studies suggest that, although increased activation of ipsilateral motor pathways from the contralesional hemisphere may occur after stroke, this activation pattern generally subsides and may be maladaptive. However, others have found that greater contralesional brain activation is associated with better functional outcomes (Luft et al., 2005), and rehabilitation-induced improvements in walking and lower limb function are associated with increased brain activation bilaterally (Enzinger et al., 2009). These conflicting findings may reflect the effect of stroke chronicity. Studies that have found beneficial associations between contralesional brain activation and function involved chronic stroke survivors (Enzinger et al., 2009; Luft et al., 2005). Studies that found detrimental associations between contralesional brain activation and function largely involved sub-acute stroke survivors (Y. H. Kim et al., 2006; Miyai et al., 2003). These findings suggest that restoration of a typical pre-stroke pattern of brain activation may be beneficial in the early stages of stroke, but increased activation (regardless of hemisphere) can be beneficial in the chronic stages of stroke.

The importance of the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract for paretic movement may be exemplified by motor, strength, and coordination deficits observed in the limb ipsilateral to the lesion (Richard W Bohannon & Andrews, 1995; Debaere, Van Assche, Kiekens, Verschueren, & Swinnen, 2001; S. H. Kim, Pohl, Luchies, Stylianou, & Won, 2003; Kitsos, Hubbard, Kitsos, & Parsons, 2013). Similarly, several case studies have detailed instances where a unilateral stroke elicits contralateral hemiparesis that gradually recovers, but a second unilateral stroke in the previously unaffected hemisphere recovery leads to ipsilateral deterioration in the previously affected paretic limbs (Ago et al., 2003; J. S. Kim, 1999; Song, Lee, Park, Yoon, & Roh, 2005; Yamamoto, Takasawa, Kajiyama, Baron, & Yamaguchi, 2007). Some of these studies demonstrated that movements in the previously affected paretic upper limb elicited increased ipsilateral fMRI activation in the previously unaffected hemisphere (Ago et al., 2003; Song et al., 2005). In these cases, paretic limb recovery after the first stroke may have occurred through the enhancement of ipsilateral motor pathways that were then negatively affected by the second stroke, leading to renewed hemiparesis.

Candidate ipsilateral motor pathways for motor recovery

Below, we discuss evidence that the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract, reticulospinal tract, rubrospinal tract, and vestibulospinal tract may contribute to paretic lower limb movement and recovery after stroke. It is important to note that other motor tracts may also contribute to ipsilateral motor effects, including the tectospinal tract and the olivospinal tract. These tracts are not discussed in this review because there is minimal evidence that they contribute to lower limb movement in humans (Nathan & Smith, 1955; Splittgerber & Snell, 2019). Inter-hemispheric interactions also influence lower limb recovery after stroke but are beyond the scope of this review.

Uncrossed (ipsilateral) lateral corticospinal tract

One ipsilateral motor pathway from the contralesional hemisphere that may contribute to movements of the paretic lower limb is the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract. In cats, rats, primates, and likely humans, ~10–20% of lateral corticospinal tract fibers descend uncrossed, forming the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract that has a comparable innervation pattern as the crossed lateral corticospinal tract from the other hemisphere (Jankowska & Edgley, 2006). Although this section discusses evidence for the role of the uncrossed ipsilateral corticospinal tract for paretic limb movement, the corticospinal tract can also have ipsilateral effects through double-crossed branches of the crossed lateral corticospinal tract or through the uncrossed anterior corticospinal tract (Carson, 2005). The anterior corticospinal tract branches from the crossed lateral corticospinal tract and descends through the medial spinal cord in crossed and uncrossed projections. The anterior corticospinal tract role in lower limb movement is likely limited because it primarily synapses on motoneurons for axial and upper limb muscles.

Animal literature has come to variable conclusions about the role of the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract for lower limb movement after stroke. In rats, a lesion of the pyramidal tract at the brainstem level increases the density and distribution of ipsilateral corticospinal tract neurons to the paretic forelimb and increases the number of crossed corticospinal tract neurons that re-cross to the paretic limb (Brus-Ramer, Carmel, Chakrabarty, & Martin, 2007). In adult rats with acute and chronic lesions, stimulation of the contralesional M1 facilitates skilled locomotor recovery specifically through the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract (Brus-Ramer et al., 2007; Carmel, Kimura, & Martin, 2014). However, other literature in monkeys suggests that the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract has minimal contribution to upper limb movement (Soteropoulos, Edgley, & Baker, 2011; Zaaimi, Edgley, Soteropoulos, & Baker, 2012). In macaque monkeys, ipsilateral responses to stimulation of the contralesional corticospinal tract are rare and weak, both in normal adults (Soteropoulos et al., 2011) and adults with contralateral corticospinal tract lesions at the medullary level (Zaaimi et al., 2012). Instead of the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract, work in monkeys points to the potential role of the reticulospinal tract (see below). Given that the organization of the human corticospinal tract is more similar to that of primates than rats, results from monkey literature may provide greater insight, albeit with limitations (Lemon & Griffiths, 2005).

The primary method that has been used to assess the excitability of the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract in humans after stroke is to apply TMS to the contralesional hemisphere and measure motor evoked potentials (MEPs) in the ipsilateral paretic limb. Several studies have demonstrated TMS-evoked ipsilateral MEPs in the paretic upper limb after stroke, but relatively few studies have reported ipsilateral MEPs in the paretic lower limb (Table 1). TMS observations in the lower limb are from individuals with chronic stroke and various lesion locations and sizes. Benecke et al. (1991) found ipsilateral MEPs in the paretic rectus femoris and tibialis anterior in individuals with severe hemiparesis. Jayaram et al. (2012) found that ipsilateral MEPs in the paretic vastus lateralis were larger than contralateral MEPs in individuals with chronic stroke (cortical and subcortical). Individuals who had greater ipsilateral MEPs relative to contralateral MEPs also had slower walking speeds and smaller lower extremity Fugl Meyer Scale (FMLE) scores. Madhavan et al. (2010) also found an increased relative ipsilateral connectivity to the paretic tibialis anterior which was associated with poorer motor control of the paretic and non-paretic ankle. Considered together, these three papers suggest that greater excitability of ipsilateral motor pathways to the paretic limb occurs after stroke but may be maladaptive. However, during a paretic hip adduction task, TMS-induced MEPs in non-target muscles (Tan, Shemmell, & Dhaher, 2016) and knee extension torque (Tan & Dhaher, 2017) are smaller when TMS is applied to the contralesional hemisphere than the ipsilesional hemisphere. These findings suggest that a greater contribution of ipsilateral motor pathways to the paretic limb may be adaptive by reducing unwanted synergistic muscle activation and movement. Whether ipsilateral motor pathways are adaptive or maladaptive may depend on the type of movement and whether the desire is to improve function broadly or performance/impairment (Levin et al., 2009).

Table 1.

Studies reporting ipsilateral motor evoked potentials in the lower limb post stroke.

| Study | Participants | Coil | Stim. intensity | Condition | Muscles | MEP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude (%MMax) | Latency (ms) | ||||||

| Benecke et al. 1991 | n=3 chronic |

120 mm circular | 60% MSO | ?% isometric | RF | ipsi: 25.7% contra: 40.7%* |

ipsi: 29.9 contra: 15.6* |

| TA | ipsi: 18.0% contra: 49.0%* |

ipsi: 40.1 contra: 16.1* |

|||||

| EDB | ipsi: NP contra: 42.3%* |

ipsi: NP contra: 16.7* |

|||||

| FCR | Latency (ms) | ||||||

| Jayaram et al. 2012 | n=9 chronic |

110 mm double cone | 80–170% AMT | 20% isometric | VL | Paretic: 1.7 Non-Paretic: 0.55 |

- |

| ICE | Latency (ms) | ||||||

| Madhavan et al. 2010 | n=15 chronic |

110 mm double cone | 30–70% MSO | 10% isometric | TA | Paretic: 0.03 Non-Paretic: 0.46 |

- |

| Amplitude | Latency | ||||||

| Tan et al. 2016 | n=12 chronic |

110 mm double cone | 40–66% MSO | 40% isometric hip adduction | VM,VL, RF,AL, TA,MG,BF |

Reported activation of non-target muscles | Mostly 0–3ms difference between sides |

| Amplitude | Latency | ||||||

| Tan & Dhaher 2017 | n=11 chronic |

110 mm double cone | ? | 40% isometric hip adduction | VM,VL AL,TA |

Reported torque of non-target muscles | - |

FCR (functional connectivity ratio): . ICE (index of corticospinal excitability): . AL: adductor longus; AMT: active motor threshold; BF: biceps femoris; EDB: extensor digitorum brevis; MG: medial gastrocnemius; %MMax: percentage of maximal muscle wave; MSO: maximal stimulator output; RF: rectus femoris; TA: tibialis anterior; VL: vastus lateralis; VM: vastus medialis;

In Benecke et al. 1991, contra represents contralateral responses in the non-paretic limb in response to the same stimuli that elicited ipsilateral responses in the paretic limb, not contralateral responses in the paretic limb to stimulation of the ipsilesional hemisphere.

There are limitations to the use of TMS for assessing the contribution of the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract. First, MEP amplitude assesses the excitability of a pathway, which is not necessarily associated with the strength of that pathway’s contribution to movement (Bestmann & Krakauer, 2015). Second, it is not clear that these responses result from activation of the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract (Fisher, Zaaimi, & Baker, 2012). Some studies have demonstrated delayed latencies for ipsilateral MEPs in the upper and lower limb, suggesting that these responses may be elicited through pathways with additional synapses, such as cortico-subcortico-spinal pathways (Benecke et al., 1991; Ziemann et al., 1999). Alternatively, delayed latencies may reflect the time for the TMS-induced electrical current to spread to the crossed lateral corticospinal tract. Thus, ipsilateral responses to TMS may represent stimulation of both crossed and uncrossed pathways, particularly in the lower limb where the motor representations of each leg are in close proximity and higher stimulation intensities are often required.

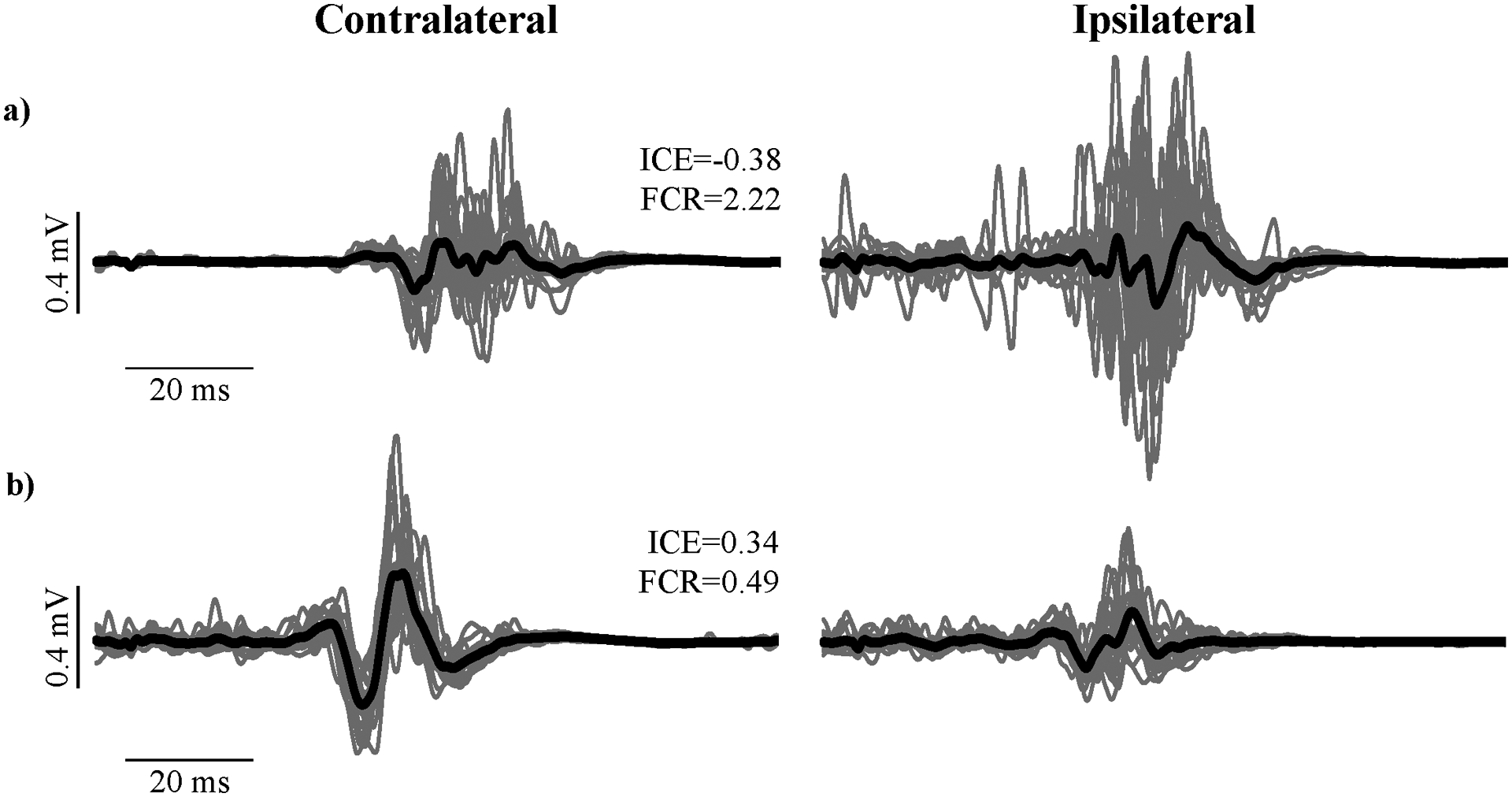

To address this issue, several studies have expressed ipsilateral MEPs relative to contralateral MEPs as a way to evaluate the probability that ipsilateral responses reflect ipsilateral, not contralateral pathways. For example, Madhavan et al. (2010) used the index of corticospinal excitability (ICE) ratio, , where slope represents the linear slope of the steepest portion of the TMS recruitment curve. Values <0, represent predominately ipsilateral excitability, and values >0 represent predominately contralateral excitability. Similarly, Jayaram et al. (2012), used the functional connectivity ratio (FCR), . Values <1 represent predominately contralateral connectivity, and values >1 represent predominately ipsilateral connectivity. Tan et al. (2016) and Tan & Dhaher (2017) evaluated the relative contribution of the ipsilesional and contralesional hemisphere to responses in non-target muscles as a similar ratio, . In Fig. 2, we provide representative examples from one individual with predominately ipsilateral excitability/connectivity (Fig. 2a) and one individual with predominately contralateral excitability/connectivity (Fig. 2b), with corresponding ICE and FCR values. Anecdotally, the individual with greater ipsilateral excitability/connectivity demonstrated a faster comfortable walking speed than the other individual (0.87 vs. 0.53 m/s), but FMLE scores were similar (23 vs. 25). In this example, greater ipsilateral excitability/connectivity may improve broad function without influencing impairment (Levin et al., 2009).

Figure 2. Contralateral and ipsilateral MEPs in humans.

Displayed are MEPs recorded in the paretic tibialis anterior following TMS at 130% of active motor threshold from two individuals with chronic stroke during isometric contractions (unpublished data). Contralateral MEPs represent responses to stimulation of the ipsilesional hemisphere, and ipsilateral MEPs represent responses to stimulation of the contralesional hemisphere. a) Participant with greater ipsilateral than contralateral MEPs. b) Participant with greater contralateral than ipsilateral MEPs. To illustrate ways that ipsilateral MEPs have been expressed relative to contralateral MEPs, index of corticospinal excitability (ICE) and functional connectivity ratio (FCR) values are displayed for each participant. Gray lines are MEPs from individual stimulations (n=20); black lines are the average MEPs.

Reticulospinal tract

Another ipsilateral motor pathway from the contralesional hemisphere that may contribute to paretic lower limb movements is the reticulospinal tract. The reticulospinal tract originates from the reticular formation in the pons and medulla and receives input primarily from M1 and PMC, forming the corticoreticulospinal tract. Other contributors to the corticoreticular tract include S1 and the prefrontal cortex. The reticulospinal tract descends through a lateral portion originating from the medullary reticular formation (lateral reticulospinal tract) and a medial portion originating from the pontine tegmentum and pontomedullary reticular formation (medial reticulospinal tract) (Splittgerber & Snell, 2019). The lateral and medial reticulospinal tract have both crossed and uncrossed fibers, although the medial reticulospinal tract is largely uncrossed. reticulospinal tract projections primarily synapse on interneurons for axial and proximal muscles in the spinal cord, although the tract also contains direct connections onto motoneurons (Splittgerber & Snell, 2019). Because of its pattern of innervation, the reticulospinal tract is thought to have a primary role in postural stability and stereotyped, multi-segmental movements such as walking. Supporting a role in locomotion, activity of reticulospinal tract neurons in the medial reticular formation is modulated in a phasic manner during locomotion and responds to gait modifications in cats (Matsuyama & Drew, 2000). Thus, reticulospinal tract is thought to provide critical input to central pattern generators to sustain and adapt locomotion. The important role of the reticulospinal tract for posture and walking may partially explain the improved recovery of the lower limb relative to the upper limb after stroke.

From the animal literature, there is also evidence for a potential role of the reticulospinal tract to paretic limb movement after stroke, although mostly in the upper limb. In monkeys, Zaaimi et al. (2012) used micro-stimulation and intercellular recordings to assess the contribution of the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract and reticulospinal tract to recovery of affected hand movement. Stimulation of the medial longitudinal fasiculus elicited bilateral responses, which were enhanced after lesioning the contralateral corticospinal tract. In contrast, stimulation of the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract rarely elicited responses before or after lesioning. These findings reinforce the idea that ipsilaterally descending subcortical pathways may have a more prominent contribution to paretic limb movement than the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract, although there are important limitations that must be considered. Animal models of stroke differ from typical stroke in humans in many ways including age of onset, cause of injury, comorbidities, and timing (van der Worp et al., 2010).

Information about the relevance of the uncrossed reticulospinal tract for paretic lower limb movement in humans after stroke is sparse. Throughout this section, discussion of the reticulospinal tract generally extends to the corticoreticulospinal tract. DTI in individuals with chronic subcortical stroke has shown that the contralesional uncrossed reticulospinal tract has increased integrity at both the brainstem and spinal levels compared to healthy controls (Karbasforoushan, Cohen-Adad, & Dewald, 2019). In contrast, the crossed lateral corticospinal tract from the ipsilesional hemisphere has decreased integrity compared to healthy controls. Although relation with lower limb motor impairment was not reported, changes in both tracts were associated with greater upper limb motor impairment (Karbasforoushan et al., 2019). These findings suggest that the reticulospinal tract may have a greater motor contribution after stroke, but that this contribution is maladaptive. In contrast, Jang et al. (2013) used DTI to demonstrate that an increased volume of reticulospinal tract fibers from the contralesional hemisphere is associated with greater walking independence in individuals with subacute thalamic stroke. Although indirect evidence, trunk control is an important predictor of walking independence after stroke (TWIST algorithm) (Smith, Barber, & Stinear, 2017). Because the reticulospinal tract has an important role in posture and trunk control (Drew, Prentice, & Schepens, 2004; Shinoda, Sugiuchi, Izawa, & Hata, 2006), these findings suggest that this motor pathway may be important for lower limb recovery after stroke. Contrasting findings between the upper limb and lower limb about the adaptiveness of the reticulospinal tract is adaptive may reflect differences in the type of movement and whether performance/impairment or broad function is assessed (Levin et al., 2009).

Another technique that has been used to evaluate the reticulospinal tract is the acoustic startle response. This is a reflex in response to a loud sound that is thought to be mediated through the reticulospinal tract (Valls-Sole, Kumru, & Kofler, 2008). Most research using the acoustic startle response has been in the upper limb and has demonstrated that the startle response is enhanced in the paretic biceps brachii of individuals with acute or chronic stroke, especially those with spasticity (Li, Chang, Francisco, & Verduzco-Gutierrez, 2014; Voordecker, Mavroudakis, Blecic, Hildebrand, & Zegers de Beyl, 1997). In the lower limb of individuals with subacute to chronic stroke, acoustic startle responses occur with greater frequency and decreased latency in the paretic tibialis anterior as compared to the non-paretic limb and controls (Jankelowitz & Colebatch, 2004a). Collectively, these findings support an increased excitability of the uncrossed reticulospinal tract during movement of the paretic lower limb. One limitation of this technique is that the acoustic stimulus is generally bilateral, disallowing the differentiation between the contributions of the crossed and uncrossed reticulospinal tract. Additionally, it is important to note that increased reflex excitability does not necessarily imply a role in movement. Amid this sparse and conflicting research, it is unclear what role the uncrossed reticulospinal tract has for paretic limb movement and recovery in humans after stroke.

Rubrospinal tract

Another subcortical motor pathway from the contralesional hemisphere that may contribute to paretic lower limb movements is the rubrospinal tract. The rubrospinal tract originates from the magnocellular portion of the red nucleus in the mesencephalon and receives input primarily from the cerebellum and the cortex (Nathan & Smith, 1955). The rubrospinal tract descends through a mostly crossed lateral tract that follows a similar path and has a similar termination pattern as the lateral corticospinal tract (Splittgerber & Snell, 2019). The pathway including the cortex and the rubrospinal tract is termed the corticorubrospinal tract. Discharge of cells in the red nucleus are related to a variety of aspects of voluntary movement. Like the reticulospinal tract, rubrospinal tract neurons are modulated in a phasic manner during locomotion and in response to gait modifications in cats (Lavoie & Drew, 2002). Because most rubrospinal tract fibers are crossed, this tract likely has a limited role as an ipsilateral uncrossed pathway to the paretic limb (although a double-crossed pathway may contribute to the paretic limb). Furthermore, there is some question about the magnitude of the role that rubrospinal tract plays in humans because the magnocellular portion of the red nucleus is quite small, and most projections from the red nucleus do not descend to the spinal cord or very far in the spinal cord (Nathan & Smith, 1955, 1982).

In rats, stimulation of the contralesional M1 enhances projections to the bilateral magnocellular red nucleus. These projections may contribute to increased strength of the uncrossed corticorubrospinal tract or the double-crossed corticorubropsinal tract (contralesional M1 to ipsilesional red nucleus to paretic limb) (Carmel, Kimura, Berrol, & Martin, 2013). Similarly, micro-stimulation in monkeys with an experimental lesion of the corticospinal tract reveals adaptations in the red nucleus that appear to contribute to motor recovery of flexor and extensor upper limb movements (Belhaj-Saïf & Cheney, 2000). In humans, DTI has shown increased integrity in the red nucleus and dorsal pons in individuals with stroke (variable chronicity and stroke location) as compared to healthy controls (Ruber, Schlaug, & Lindenberg, 2012; Takenobu et al., 2014; Yeo & Jang, 2010), suggesting an increased strength of the rubrospinal tract. Of these studies, one showed increased integrity bilaterally (Ruber et al., 2012) and two showed increased integrity only in the ipsilesional hemisphere (Takenobu et al., 2014; Yeo & Jang, 2010). Thus, it is unclear whether changes in rubrospinal tract integrity reflect changes in uncrossed, crossed, double-crossed, or all of these pathways to the paretic limb. Importantly, increased integrity of the red nucleus and dorsal pons in humans was associated with better upper limb motor function (Ruber et al., 2012; Takenobu et al., 2014; Yeo & Jang, 2010). Overall, these studies suggest that the rubrospinal tract may play a role in the recovery of paretic limb movement after stroke, although this suggestion is tempered by the diminished role of the rubrospinal tract in humans and limb and species differences.

Vestibulospinal tract

The vestibulospinal tract originates from the vestibular nuclei in the pons and medulla and receives input primarily from the vestibular apparatus, with some input from the cortex (Fukushima, 1997). The vestibulospinal tract descends through an uncrossed lateral portion and through an uncrossed medial portion originating from the lateral vestibular nucleus (Fukushima, 1997). Projections from the lateral vestibulospinal tract primarily synapse on interneurons for axial and proximal muscles of the upper and lower limb. Projections from the medial vestibulospinal tract terminate in the cervical and high thoracic spinal cord, and thus, are thought to primarily contribute to axial and upper limb motor control. Like the reticulospinal tract and rubrospinal tract, vestibulospinal tract neurons are modulated in a phasic manner during locomotion in cats (Matsuyama & Drew, 2000). The role of the vestibulospinal tract for posture and walking (Drew et al., 2004) may partially account for improved recovery of the lower limb relative to the upper limb after stroke.

The primary method to assess the strength of the descending vestibulospinal tract is with sound evoked myogenic potentials (SEMPs) with intense acoustic stimulation that elicits a response in the vestibular nuclei (Colebatch, Halmagyi, & Skuse, 1994). Responses are at a shorter latency than the acoustic startle reflex. In the upper limb, SEMPs in the biceps brachii are only present in the paretic limb for some individuals with chronic stroke (Miller & Rymer, 2017). In others with bilateral SEMPs, the response amplitude is larger in the paretic than the non-paretic biceps brachii and sternocleidomastoid (Miller, Klein, Suresh, & Rymer, 2014; Miller & Rymer, 2017). This suggests that there is increased strength of the descending vestibulospinal tract to the paretic limb (but see (Jankelowitz & Colebatch, 2004b)). As mentioned for the reticulospinal tract, the importance of trunk control for walking independence (Smith et al., 2017) suggests that the vestibulospinal tract may have an important role in walking recovery. Although increased strength of this pathway may contribute to motor control, an increase in vestibulospinal tract strength likely contributes to overall spinal hyperexcitability and spasticity (Li & Francisco, 2015). Paired with the relative paucity of evidence about this pathway, particularly in the lower limb, it is unclear whether the contribution of the vestibulospinal tract is enhanced after stroke and whether such enhancement is adaptive. Furthermore, the adaptiveness of this pathway may depend on the task and outcome.

Spinal interneuronal pathways

Although not specifically ipsilateral motor pathways, we would be remiss to not mention spinal interneuronal pathways, such as the central pattern generator (CPG) and propriospinal pathways, which play a greater role for movements of the lower limb than the upper limb, and may contribute to lower limb movement and recovery after stroke (Knikou, 2010; Zehr et al., 2004) and partially explain why lower limb recovery often exceeds that of the upper limb. CPGs are specialized circuits located in the spinal cord that yield rhythmic locomotor movements (MacKay-Lyons, 2002). Supraspinal inputs have a complex influence on and interaction with CPG operation, and changes after stroke (particularly enhancement of cortico-subcortico-spinal and ipsilateral pathways) may impact CPG function and activation of the lower limbs (MacKay-Lyons, 2002). Propriospinal pathways are spinal interneurons that transmit signals over short or long distances. These pathways may serve to process and relay descending commands, particularly from cortico-subcortico-spinal pathways, and thus, may become more important to achieve muscle activation after stroke, particularly if ipsilateral pathways are enhanced.

Modulation patterns of muscle activity and reflexes can provide insight into CPG pathways (Burke, 1999), and several studies have investigated these patterns in the lower limb after stroke. Kautz & Patten found that the movement of the non-paretic leg influences muscle activation in the paretic leg during bilateral pedaling, but not during isometric or discrete movements in individuals with chronic stroke (Kautz & Patten, 2005). Furthermore, unilateral pedaling of the non-paretic leg induces rhythmic muscle activation in the paretic leg, especially in individuals with greater stroke-related impairment (Kautz, Patten, & Neptune, 2006). These exaggerated interlimb influences may reflect altered CPG processing of sensory information form the non-paretic leg. In terms of reflexes, individuals with subacute to chronic stroke have relatively preserved interlimb cutaneous reflexes during walking, although there are some alterations in modulation pattern (Zehr, Fujita, & Stein, 1998; Zehr & Loadman, 2012). Although these studies suggest that CPG function in the lower limb may be altered after stroke, it is unclear whether these changes are adaptive. Furthermore, current methods to assess CPG function are indirect and may reflect other changes within the nervous system.

Animal work supports a role for spinal interneuronal systems in recovery from neurological injury (Filli & Schwab, 2015). For example, in rats with a lateral hemisection at the thoracic level, recovery of hindlimb stepping is likely mediated through increased sprouting and growth of propriospinal pathways rather than through direct descending projections (Bareyre et al., 2004; Courtine et al., 2008). In humans with stroke, propriospinal systems appear to be preserved but may have a blunted effect. In the paretic and non-paretic upper limb of individuals with chronic stroke, intra- and inter-limb cutaneous reflexes are apparent after stroke (Zehr, Loadman, & Hundza, 2012). In the lower limb, interlimb reflexes in the paretic leg after stimulation of the non-paretic leg and arm are apparent, supporting the preservation of these interlimb pathways (Zehr & Loadman, 2012). Similarly, modulation of muscle activity and cutaneous reflexes occurs during walking and arm and leg cycling in individuals with chronic stroke (Klarner, Barss, Sun, Kaupp, & Zehr, 2014). Although these pathways appear to be intact after stroke, their effects also may be blunted (Barzi & Zehr, 2008) and lead to inappropriate and dysfunctional activation (Zehr & Loadman, 2012). These findings do not necessarily support an increased role of propriospinal pathways for spontaneous recovery after stroke, but in the Implications for rehabilitation section, we discuss evidence that propriospinal pathways may be exploited to improve recovery.

Conclusions

Motor pathways descending ipsilaterally from the contralesional hemisphere to the paretic limb may contribute to movement after stroke-related damage to the crossed lateral corticospinal tract. In the studies that have investigated ipsilateral motor pathways to the lower limb after stroke, there is compelling evidence that the uncrossed lateral corticospinal tract and reticulospinal tract may be important for motor recovery, with input from the rubrospinal tract, vestibulospinal tract, and spinal interneuronal pathways. However, the evidence is sparse, which weakens any conclusions. Additionally, the contribution and adaptiveness of each pathway may depend on the type of movement and whether the desire is to improve function broadly or performance/impairment (i.e. compensation vs. recovery). Because of the importance of improving walking and mobility after stroke (R. W. Bohannon et al., 1988; Gresham et al., 1975), more research into the role of these ipsilateral motor pathways is needed.

Implications for rehabilitation

Knowledge about the functional relevance of ipsilateral motor pathways to the paretic limb has important implications for rehabilitation. This section discusses these implications but is speculative because the adaptive involvement of these pathways is still unclear. Under the guidance of the popular interhemispheric inhibition model, many investigations have used non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) tools like transcranial direct current stimulation, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and epidural electrical cortical stimulation to decrease the excitability of the contralesional hemisphere and/or increase the excitability of the ipsilesional hemisphere (Boddington & Reynolds, 2017). This strategy aims to enhance contralateral motor pathways from the ipsilesional hemisphere to the paretic limb and is often paired with a motor task or therapy to enhance the effects and target neuroplasticity in relation to particular movements. However, if ipsilateral motor pathways play an important role in stroke recovery, such an approach could potentially disrupt recovery. For some individuals with stroke, using NIBS to increase the excitability of the contralesional hemisphere and enhance ipsilateral motor pathways may be potentially beneficial (Bradnam et al., 2013; Plow et al., 2016). Under this strategy, preliminary assessments, such as presence of ipsilateral MEPs, would be used to determine whether facilitatory NIBS should be applied in an attempt to upregulate ipsilateral motor pathways. Further benefit may be garnered by pairing this NIBS strategy with concurrent therapy. Similar strategies have been proposed in the upper limb; for example, Stinear et al. (2007) suggested that individuals without contralateral MEPs and reduced integrity of the ipsilesional corticospinal pathway may benefit from priming the contralesional cortex. In addition to the implications for the application of NIBS, knowledge about the functional relevance of ipsilateral motor pathways to the paretic limb can also support the use of ipsilateral motor signals to drive brain-computer interface systems (Bundy et al., 2017). Future research will have to determine whether enhancing the contralesional hemisphere could have a negative effect by accentuating interhemispheric inhibition of the ipsilesional hemisphere (Boddington & Reynolds, 2017).

Considering the potential role of the reticulospinal tract in lower limb movement and recovery, strategies to enhance activation of this pathway may be beneficial after stroke. Recent work has shown that a startling acoustic stimulus can enhance execution of a planned movement or responses to perturbations (termed the StartReact reflex) in the elbow flexors, hand extensors, and ankle dorsiflexors after stroke (Coppens et al., 2018; Honeycutt & Perreault, 2012; Honeycutt, Tresch, & Perreault, 2015). Furthermore, startling acoustic stimulus has been shown to enhance automatic postural responses and intra- and inter-limb coordination in response to a balance perturbation (Coppens et al., 2018). Like the acoustic startle reflex, the StartReact reflex is thought to be elicited via the reticulospinal tract. Because of this movement enhancement, acoustic stimuli may be useful as a clinical tool, and repeated application of the StartReact reflex in a training environment may lead to plasticity and enhanced activation of the reticulospinal tract. Interestingly, transcranial direct current stimulation can further enhance the StartReact reflex and automatic postural responses in the lower limb of neurologically intact individuals (Nonnekes et al., 2014). These findings raise the possibility that a combination of NIBS and startling acoustic stimulus may further enhance recovery after stroke.

Because CPG and propriospinal pathways help relay descending input and may enhance motor input to the lower limb, strategies to utilize these pathways after stroke may be helpful. In particular, recent work has suggested that movement of the arms can facilitate muscle activation in the legs (Ferris, Huang, & Kao, 2006) and may improve walking after stroke (Klarner et al., 2016; Zehr et al., 2016). Kaupp et al. found that 5 weeks of arm cycling can lead to increased modulation of muscle activity, cutaneous reflexes, and stretch reflexes in the bilateral tibialis anterior (Kaupp et al., 2018).

Future research

Much of our evidence for the role of ipsilateral motor pathways comes from TMS studies, which have shortcomings that must be addressed by future investigations. Notably, ipsilateral responses to TMS have unclear constituent motor pathways. Future work should use experimental paradigms that help discriminate the potential motor pathways contributing to ipsilateral MEPs. For example, since longer MEP latencies may represent the activation of cortico-subcortico-spinal pathways (Fisher et al., 2012), studies should report the latencies of both ipsilateral and contralateral MEPs to allow this differentiation. TMS can be paired with DTI to help determine which motor pathways may be contributing to ipsilateral MEPs ((e.g. B. R. Kim et al., 2016)). Furthermore, pairing TMS with the acoustic startle response may help clarify the contribution of the reticulospinal tract after stroke (Chen, Li, Zhou, & Li, 2019).

Another limitation of TMS studies of ipsilateral pathways is that ipsilateral MEPs may result from the spread of current and activation of the crossed lateral corticospinal tract. To address this issue, future studies could use modeling to predict the induced electrical field, the activation of neurons, and the likelihood of involvement of different motor tracts (Goetz & Deng, 2017). To isolate ipsilateral from contralateral pathways more work could be focused on developing TMS coils that improve focality without sacrificing penetration depth (Deng, Lisanby, & Peterchev, 2013). Furthermore, instead of using suprathreshold TMS, future studies could apply subthreshold TMS to the contralesional hemisphere ((e.g. Petersen et al., 2001)). Activation of the ipsilesional hemisphere would be less likely following application of subthreshold TMS to the contralesional hemisphere, and deficits in ongoing EMG following stimulation would provide an indication of the ipsilateral cortical contribution to activation.

Beyond understanding the precise ipsilateral pathways involved in movement of the paretic lower limb, more research is needed to understand whether these enhanced ipsilateral pathways are supportive of post-stroke motor recovery. As detailed in this review, previous work is divided about whether ipsilateral pathways are related to better or worse function and recovery after stroke. Future work should help clarify this issue by linking the relative motor contributions of ipsilateral pathways to important functional outcomes to help drive these and other rehabilitative efforts.

Limitations

There are several factors that limit our ability to draw conclusions about the contribution of different motor pathways to movement and recovery of the paretic limb. First, we review evidence from neuroimaging (e.g. fMRI, DTI) and electrical stimulation (e.g. TMS, microstimulation, and peripheral stimulation), but these outcome measures do not necessarily assess the direct contribution of a particular pathway to movement (Bestmann & Krakauer, 2015; Johansen-Berg & Behrens, 2006; Krakauer, 2007; Logothetis, 2008). Second, many of these studies do not assess whether outcome measures and particular pathways have a beneficial or maladaptive influence on function. Third, we discuss findings as generally applicable to the stroke population as a whole, which may not be appropriate. Lesion characteristics (e.g. size, location, etiology) and person-specific factors (e.g. impairment level, comorbidities, time since stroke) all likely affect the contribution of individual pathways to the paretic limb and recovery from stroke. There have been only a limited number of studies that provide any insight into how these factors may influence the ipsilateral pathways that contribute to stroke recovery. Fourth, we present evidence from animal literature for insight into motor control and recovery after stroke, but there are many differences between animal models and human stroke that limit extrapolation of findings (van der Worp et al., 2010).

Supplementary Material

Significance statement.

This paper provides insight into the role of motor pathways from the undamaged brain hemisphere to movement and recovery of the less affected lower limb after stroke; this information may guide rehabilitative efforts to improve walking after stroke.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [F32HD102214 & R01HD075777].

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Accessibility

Data sharing not applicable – no new data generated.

References

- Ago T, Kitazono T, Ooboshi H, Takada J, Yoshiura T, Mihara F, … Iida M (2003). Deterioration of pre-existing hemiparesis brought about by subsequent ipsilateral lacunar infarction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 74(8), 1152–1153. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.8.1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn YH, Ahn SH, Kim H, Hong JH, & Jang SH (2006). Can stroke patients walk after complete lateral corticospinal tract injury of the affected hemisphere? Neuroreport, 17(10), 987–990. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000220128.01597.e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alawieh A, Tomlinson S, Adkins D, Kautz S, & Feng W (2017). Preclinical and Clinical Evidence on Ipsilateral Corticospinal Projections: Implication for Motor Recovery. Transl Stroke Res, 8(6), 529–540. doi: 10.1007/s12975-017-0551-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bareyre FM, Kerschensteiner M, Raineteau O, Mettenleiter TC, Weinmann O, & Schwab ME (2004). The injured spinal cord spontaneously forms a new intraspinal circuit in adult rats. Nat Neurosci, 7(3), 269–277. doi: 10.1038/nn1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzi Y, & Zehr EP (2008). Rhythmic arm cycling suppresses hyperactive soleus H-reflex amplitude after stroke. Clin Neurophysiol, 119(6), 1443–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belhaj-Saïf A, & Cheney PD (2000). Plasticity in the distribution of the red nucleus output to forearm muscles after unilateral lesions of the pyramidal tract. J Neurophysiol, 83(5), 3147–3153. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.3147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benecke R, Meyer BU, & Freund HJ (1991). Reorganisation of descending motor pathways in patients after hemispherectomy and severe hemispheric lesions demonstrated by magnetic brain stimulation. Exp Brain Res, 83(2), 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestmann S, & Krakauer JW (2015). The uses and interpretations of the motor-evoked potential for understanding behaviour. Exp Brain Res, 233(3), 679–689. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-4183-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddington LJ, & Reynolds JN (2017). Targeting interhemispheric inhibition with neuromodulation to enhance stroke rehabilitation. Brain Stimul, 10(2), 214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon RW, & Andrews AW (1995). Limb muscle strength is impaired bilaterally after stroke. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 7, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon RW, Andrews AW, & Smith MB (1988). Rehabilitation goals of patients with hemiplegia. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 11(2), 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bradnam LV, Stinear CM, & Byblow WD (2013). Ipsilateral motor pathways after stroke: implications for non-invasive brain stimulation. Front Hum Neurosci, 7, 184. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brus-Ramer M, Carmel JB, Chakrabarty S, & Martin JH (2007). Electrical stimulation of spared corticospinal axons augments connections with ipsilateral spinal motor circuits after injury. J Neurosci, 27(50), 13793–13801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3489-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundy DT, Souders L, Baranyai K, Leonard L, Schalk G, Coker R, … Leuthardt EC (2017). Contralesional Brain-Computer Interface Control of a Powered Exoskeleton for Motor Recovery in Chronic Stroke Survivors. Stroke, 48(7), 1908–1915. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.116.016304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RE (1999). The use of state-dependent modulation of spinal reflexes as a tool to investigate the organization of spinal interneurons. Exp Brain Res, 128(3), 263–277. doi: 10.1007/s002210050847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel JB, Kimura H, Berrol LJ, & Martin JH (2013). Motor cortex electrical stimulation promotes axon outgrowth to brain stem and spinal targets that control the forelimb impaired by unilateral corticospinal injury. Eur J Neurosci, 37(7), 1090–1102. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel JB, Kimura H, & Martin JH (2014). Electrical stimulation of motor cortex in the uninjured hemisphere after chronic unilateral injury promotes recovery of skilled locomotion through ipsilateral control. J Neurosci, 34(2), 462–466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3315-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson RG (2005). Neural pathways mediating bilateral interactions between the upper limbs. Brain Res Brain Res Rev, 49(3), 641–662. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MC, Do KH, & Chun MH (2015). Prediction of lower limb motor outcomes based on transcranial magnetic stimulation findings in patients with an infarct of the anterior cerebral artery. Somatosens Mot Res, 32(4), 249–253. doi: 10.3109/08990220.2015.1091769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YT, Li S, Zhou P, & Li S (2019). A startling acoustic stimulation (SAS)-TMS approach to assess the reticulospinal system in healthy and stroke subjects. J Neurol Sci, 399, 82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2019.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HM, Choi BY, Chang CH, Kim SH, Lee J, Chang MC, … Jang SH (2012). The clinical characteristics of motor function in chronic hemiparetic stroke patients with complete corticospinal tract injury. NeuroRehabilitation, 31(2), 207–213. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2012-0790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colebatch JG, Halmagyi GM, & Skuse NF (1994). Myogenic potentials generated by a click-evoked vestibulocollic reflex. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 57(2), 190–197. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.2.190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppens MJM, Roelofs JMB, Donkers NAJ, Nonnekes J, Geurts ACH, & Weerdesteyn V (2018). A startling acoustic stimulus facilitates voluntary lower extremity movements and automatic postural responses in people with chronic stroke. J Neurol, 265(7), 1625–1635. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-8889-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtine G, Roy RR, Raven J, Hodgson J, McKay H, Yang H, … Edgerton VR (2005). Performance of locomotion and foot grasping following a unilateral thoracic corticospinal tract lesion in monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Brain, 128(Pt 10), 2338–2358. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtine G, Song B, Roy RR, Zhong H, Herrmann JE, Ao Y, … Sofroniew MV (2008). Recovery of supraspinal control of stepping via indirect propriospinal relay connections after spinal cord injury. Nat Med, 14(1), 69–74. doi: 10.1038/nm1682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes H, Enzinger C, Johansen-Berg H, Bogdanovic M, Guy C, Collett J, … Matthews PM (2008). Walking performance and its recovery in chronic stroke in relation to extent of lesion overlap with the descending motor tract. Exp Brain Res, 186(2), 325–333. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1237-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debaere F, Van Assche D, Kiekens C, Verschueren SM, & Swinnen SP (2001). Coordination of upper and lower limb segments: deficits on the ipsilesional side after unilateral stroke. Exp Brain Res, 141(4), 519–529. doi: 10.1007/s002210100891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng ZD, Lisanby SH, & Peterchev AV (2013). Electric field depth-focality tradeoff in transcranial magnetic stimulation: simulation comparison of 50 coil designs. Brain Stimul, 6(1), 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers J, Malouin F, Richards C, Bourbonnais D, Rochette A, & Bravo G (2003). Comparison of changes in upper and lower extremity impairments and disabilities after stroke. Int J Rehabil Res, 26(2), 109–116. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200306000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew T, Prentice S, & Schepens B (2004). Cortical and brainstem control of locomotion. Prog Brain Res, 143, 251–261. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(03)43025-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enzinger C, Dawes H, Johansen-Berg H, Wade D, Bogdanovic M, Collett J, … Matthews PM (2009). Brain activity changes associated with treadmill training after stroke. Stroke, 40(7), 2460–2467. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.109.550053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enzinger C, Johansen-Berg H, Dawes H, Bogdanovic M, Collett J, Guy C, … Matthews PM (2008). Functional MRI correlates of lower limb function in stroke victims with gait impairment. Stroke, 39(5), 1507–1513. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.107.501999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris DP, Huang HJ, & Kao PC (2006). Moving the arms to activate the legs. Exerc Sport Sci Rev, 34(3), 113–120. doi: 10.1249/00003677-200607000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filli L, & Schwab ME (2015). Structural and functional reorganization of propriospinal connections promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res, 10(4), 509–513. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.155425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher KM, Zaaimi B, & Baker SN (2012). Reticular formation responses to magnetic brain stimulation of primary motor cortex. J Physiol, 590(16), 4045–4060. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.226209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima K (1997). Corticovestibular interactions: anatomy, electrophysiology, and functional considerations. Exp Brain Res, 117(1), 1–16. doi: 10.1007/pl00005786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz SM, & Deng ZD (2017). The development and modelling of devices and paradigms for transcranial magnetic stimulation. Int Rev Psychiatry, 29(2), 115–145. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2017.1305949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham GE, Fitzpatrick TE, Wolf PA, McNamara PM, Kannel WB, & Dawber TR (1975). Residual disability in survivors of stroke--the Framingham study. N Engl J Med, 293(19), 954–956. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197511062931903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks HT, Pasman JW, van Limbeek J, & Zwarts MJ (2003). Motor evoked potentials of the lower extremity in predicting motor recovery and ambulation after stroke: a cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 84(9), 1373–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honeycutt CF, & Perreault EJ (2012). Planning of ballistic movement following stroke: insights from the startle reflex. Plos One, 7(8), e43097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honeycutt CF, Tresch UA, & Perreault EJ (2015). Startling acoustic stimuli can evoke fast hand extension movements in stroke survivors. Clin Neurophysiol, 126(1), 160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JS, Kim JM, & Kim HS (2016). Correlation between ambulatory function and clinical factors in hemiplegic patients with intact single lateral corticospinal tract: A pilot study. Medicine (Baltimore), 95(31), e4360. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imura T, Nagasawa Y, Inagawa T, Imada N, Izumi H, Emoto K, … Araki O (2015). Prediction of motor outcomes and activities of daily living function using diffusion tensor tractography in acute hemiparetic stroke patients. J Phys Ther Sci, 27(5), 1383–1386. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SH, Bai D, Son SM, Lee J, Kim DS, Sakong J, … Yang DS (2008). Motor outcome prediction using diffusion tensor tractography in pontine infarct. Ann Neurol, 64(4), 460–465. doi: 10.1002/ana.21444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SH, Chang CH, Lee J, Kim CS, Seo JP, & Yeo SS (2013). Functional role of the corticoreticular pathway in chronic stroke patients. Stroke, 44(4), 1099–1104. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SH, You SH, Kwon YH, Hallett M, Lee MY, & Ahn SH (2005). Cortical reorganization associated lower extremity motor recovery as evidenced by functional MRI and diffusion tensor tractography in a stroke patient. Restor Neurol Neurosci, 23(5–6), 325–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankelowitz SK, & Colebatch JG (2004a). The acoustic startle reflex in ischemic stroke. Neurology, 62(1), 114–116. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000101711.48946.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankelowitz SK, & Colebatch JG (2004b). Galvanic evoked vestibulospinal and vestibulocollic reflexes in stroke. Clin Neurophysiol, 115(8), 1796–1801. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E, & Edgley SA (2006). How can corticospinal tract neurons contribute to ipsilateral movements? A question with implications for recovery of motor functions. Neuroscientist, 12(1), 67–79. doi: 10.1177/1073858405283392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaram G, Stagg CJ, Esser P, Kischka U, Stinear J, & Johansen-Berg H (2012). Relationships between functional and structural corticospinal tract integrity and walking post stroke. Clin Neurophysiol, 123(12), 2422–2428. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2012.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen-Berg H, & Behrens TE (2006). Just pretty pictures? What diffusion tractography can add in clinical neuroscience. Curr Opin Neurol, 19(4), 379–385. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000236618.82086.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbasforoushan H, Cohen-Adad J, & Dewald JPA (2019). Brainstem and spinal cord MRI identifies altered sensorimotor pathways post-stroke. Nat Commun, 10(1), 3524. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11244-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupp C, Pearcey GEP, Klarner T, Sun Y, Cullen H, Barss TS, & Zehr EP (2018). Rhythmic arm cycling training improves walking and neurophysiological integrity in chronic stroke: the arms can give legs a helping hand in rehabilitation. J Neurophysiol, 119(3), 1095–1112. doi: 10.1152/jn.00570.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautz SA, & Patten C (2005). Interlimb influences on paretic leg function in poststroke hemiparesis. J Neurophysiol, 93(5), 2460–2473. doi: 10.1152/jn.00963.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautz SA, Patten C, & Neptune RR (2006). Does unilateral pedaling activate a rhythmic locomotor pattern in the nonpedaling leg in post-stroke hemiparesis? J Neurophysiol, 95(5), 3154–3163. doi: 10.1152/jn.00951.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesar TM, Stinear JW, & Wolf SL (2018). The use of transcranial magnetic stimulation to evaluate cortical excitability of lower limb musculature: Challenges and opportunities. Restor Neurol Neurosci, 36(3), 333–348. doi: 10.3233/rnn-170801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BR, Moon WJ, Kim H, Jung E, & Lee J (2016). Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation and Diffusion Tensor Tractography for Evaluating Ambulation after Stroke. J Stroke, 18(2), 220–226. doi: 10.5853/jos.2015.01767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EH, Lee J, & Jang SH (2013). Motor outcome prediction using diffusion tensor tractography of the corticospinal tract in large middle cerebral artery territory infarct. NeuroRehabilitation, 32(3), 583–590. doi: 10.3233/NRE-130880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS (1999). Aggravation of poststroke sensory symptoms after a second stroke on the opposite side. Eur Neurol, 42(4), 200–204. doi: 10.1159/000008107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Pohl PS, Luchies CW, Stylianou AP, & Won Y (2003). Ipsilateral deficits of targeted movements after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 84(5), 719–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, You SH, Kwon YH, Hallett M, Kim JH, & Jang SH (2006). Longitudinal fMRI study for locomotor recovery in patients with stroke. Neurology, 67(2), 330–333. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000225178.85833.0d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitsos GH, Hubbard IJ, Kitsos AR, & Parsons MW (2013). The ipsilesional upper limb can be affected following stroke. ScientificWorldJournal, 2013, 684860. doi: 10.1155/2013/684860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klarner T, Barss TS, Sun Y, Kaupp C, Loadman PM, & Zehr EP (2016). Exploiting Interlimb Arm and Leg Connections for Walking Rehabilitation: A Training Intervention in Stroke. Neural Plast, 2016, 1517968. doi: 10.1155/2016/1517968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klarner T, Barss TS, Sun Y, Kaupp C, & Zehr EP (2014). Preservation of common rhythmic locomotor control despite weakened supraspinal regulation after stroke. Front Integr Neurosci, 8, 95. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2014.00095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knikou M (2010). Neural control of locomotion and training-induced plasticity after spinal and cerebral lesions. Clin Neurophysiol, 121(10), 1655–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer JW (2007). Avoiding performance and task confounds: multimodal investigation of brain reorganization after stroke rehabilitation. Exp Neurol, 204(2), 491–495. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie S, & Drew T (2002). Discharge characteristics of neurons in the red nucleus during voluntary gait modifications: a comparison with the motor cortex. J Neurophysiol, 88(4), 1791–1814. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.4.1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon RN, & Griffiths J (2005). Comparing the function of the corticospinal system in different species: organizational differences for motor specialization? Muscle Nerve, 32(3), 261–279. doi: 10.1002/mus.20333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin MF, Kleim JA, & Wolf SL (2009). What do motor “recovery” and “compensation” mean in patients following stroke? Neurorehabil Neural Repair, 23(4), 313–319. doi: 10.1177/1545968308328727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Chang SH, Francisco GE, & Verduzco-Gutierrez M (2014). Acoustic startle reflex in patients with chronic stroke at different stages of motor recovery: a pilot study. Top Stroke Rehabil, 21(4), 358–370. doi: 10.1310/tsr2104-358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, & Francisco GE (2015). New insights into the pathophysiology of post-stroke spasticity. Front Hum Neurosci, 9, 192. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK (2008). What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI. Nature, 453(7197), 869–878. doi: 10.1038/nature06976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft AR, Forrester L, Macko RF, McCombe-Waller S, Whitall J, Villagra F, & Hanley DF (2005). Brain activation of lower extremity movement in chronically impaired stroke survivors. Neuroimage, 26(1), 184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft AR, Macko RF, Forrester LW, Villagra F, Ivey F, Sorkin JD, … Hanley DF (2008). Treadmill exercise activates subcortical neural networks and improves walking after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke, 39(12), 3341–3350. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.527531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntosh BJ, McIlroy WE, Mraz R, Staines WR, Black SE, & Graham SJ (2008). Electrodermal recording and fMRI to inform sensorimotor recovery in stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair, 22(6), 728–736. doi: 10.1177/1545968308316386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay-Lyons M (2002). Central pattern generation of locomotion: a review of the evidence. Phys Ther, 82(1), 69–83. doi: 10.1093/ptj/82.1.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan S, Rogers LM, & Stinear JW (2010). A paradox: after stroke, the non-lesioned lower limb motor cortex may be maladaptive. Eur J Neurosci, 32(6), 1032–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07364.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama K, & Drew T (2000). Vestibulospinal and reticulospinal neuronal activity during locomotion in the intact cat. I. Walking on a level surface. J Neurophysiol, 84(5), 2237–2256. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.5.2237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DM, Klein CS, Suresh NL, & Rymer WZ (2014). Asymmetries in vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in chronic stroke survivors with spastic hypertonia: evidence for a vestibulospinal role. Clin Neurophysiol, 125(10), 2070–2078. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DM, & Rymer WZ (2017). Sound-Evoked Biceps Myogenic Potentials Reflect Asymmetric Vestibular Drive to Spastic Muscles in Chronic Hemiparetic Stroke Survivors. Front Hum Neurosci, 11, 535. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyai I, Yagura H, Hatakenaka M, Oda I, Konishi I, & Kubota K (2003). Longitudinal optical imaging study for locomotor recovery after stroke. Stroke, 34(12), 2866–2870. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000100166.81077.8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyai I, Yagura H, Oda I, Konishi I, Eda H, Suzuki T, & Kubota K (2002). Premotor cortex is involved in restoration of gait in stroke. Ann Neurol, 52(2), 188–194. doi: 10.1002/ana.10274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan PW, & Smith MC (1955). Long descending tracts in man. I. Review of present knowledge. Brain, 78(2), 248–303. doi: 10.1093/brain/78.2.248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan PW, & Smith MC (1982). The rubrospinal and central tegmental tracts in man. Brain, 105(Pt 2), 223–269. doi: 10.1093/brain/105.2.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonnekes J, Arrogi A, Munneke MA, van Asseldonk EH, Oude Nijhuis LB, Geurts AC, & Weerdesteyn V (2014). Subcortical structures in humans can be facilitated by transcranial direct current stimulation. Plos One, 9(9), e107731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen NT, Butler JE, Marchand-Pauvert V, Fisher R, Ledebt A, Pyndt HS, … Nielsen JB (2001). Suppression of EMG activity by transcranial magnetic stimulation in human subjects during walking. J Physiol, 537(Pt 2), 651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plow EB, Sankarasubramanian V, Cunningham DA, Potter-Baker K, Varnerin N, Cohen LG, … Machado AG (2016). Models to Tailor Brain Stimulation Therapies in Stroke. Neural Plast, 2016, 4071620. doi: 10.1155/2016/4071620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter R, & Lemon R (1993). Corticospinal function and voluntary movement. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruber T, Schlaug G, & Lindenberg R (2012). Compensatory role of the cortico-rubro-spinal tract in motor recovery after stroke. Neurology, 79(6), 515–522. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826356e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo JP, Do KH, Jung GS, Seo SW, Kim K, Son SM, … Jang SH (2014). The difference of gait pattern according to the state of the corticospinal tract in chronic hemiparetic stroke patients. NeuroRehabilitation, 34(2), 259–266. doi: 10.3233/NRE-131046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinoda Y, Sugiuchi Y, Izawa Y, & Hata Y (2006). Long descending motor tract axons and their control of neck and axial muscles. Prog Brain Res, 151, 527–563. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)51017-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakrishnan A, & Madhavan S (2018). Absence of a Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation-Induced Lower Limb Corticomotor Response Does Not Affect Walking Speed in Chronic Stroke Survivors. Stroke, 49(8), 2004–2007. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.118.021718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MC, Barber PA, & Stinear CM (2017). The TWIST Algorithm Predicts Time to Walking Independently After Stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair, 31(10–11), 955–964. doi: 10.1177/1545968317736820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song YM, Lee JY, Park JM, Yoon BW, & Roh JK (2005). Ipsilateral hemiparesis caused by a corona radiata infarct after a previous stroke on the opposite side. Arch Neurol, 62(5), 809–811. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.5.809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soteropoulos DS, Edgley SA, & Baker SN (2011). Lack of evidence for direct corticospinal contributions to control of the ipsilateral forelimb in monkey. J Neurosci, 31(31), 11208–11219. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0257-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splittgerber R, & Snell RS (2019). Snell’s clinical neuroanatomy (Eighth edition. ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Steube D, Wietholter S, & Correll C (2001). Prognostic value of lower limb motor evoked potentials for motor impairment and disability after 8 weeks of stroke rehabilitation--a prospective investigation of 100 patients. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol, 41(8), 463–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinear CM, Barber PA, Smale PR, Coxon JP, Fleming MK, & Byblow WD (2007). Functional potential in chronic stroke patients depends on corticospinal tract integrity. Brain, 130(Pt 1), 170–180. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenobu Y, Hayashi T, Moriwaki H, Nagatsuka K, Naritomi H, & Fukuyama H (2014). Motor recovery and microstructural change in rubro-spinal tract in subcortical stroke. Neuroimage Clin, 4, 201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan AQ, & Dhaher YY (2017). Contralesional Hemisphere Regulation of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation-Induced Kinetic Coupling in the Poststroke Lower Limb. Front Neurol, 8, 373. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan AQ, Shemmell J, & Dhaher YY (2016). Downregulating Aberrant Motor Evoked Potential Synergies of the Lower Extremity Post Stroke During TMS of the Contralesional Hemisphere. Brain Stimul, 9(3), 396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valls-Sole J, Kumru H, & Kofler M (2008). Interaction between startle and voluntary reactions in humans. Exp Brain Res, 187(4), 497–507. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1402-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Worp HB, Howells DW, Sena ES, Porritt MJ, Rewell S, O’Collins V, & Macleod MR (2010). Can animal models of disease reliably inform human studies? PLoS Med, 7(3), e1000245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voordecker P, Mavroudakis N, Blecic S, Hildebrand J, & Zegers de Beyl D (1997). Audiogenic startle reflex in acute hemiplegia. Neurology, 49(2), 470–473. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.2.470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Takasawa M, Kajiyama K, Baron JC, & Yamaguchi T (2007). Deterioration of hemiparesis after recurrent stroke in the unaffected hemisphere: Three further cases with possible interpretation. Cerebrovasc Dis, 23(1), 35–39. doi: 10.1159/000095756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JF, & Gorassini M (2006). Spinal and brain control of human walking: implications for retraining of walking. Neuroscientist, 12(5), 379–389. doi: 10.1177/1073858406292151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo SS, & Jang SH (2010). Changes in red nucleus after pyramidal tract injury in patients with cerebral infarct. NeuroRehabilitation, 27(4), 373–377. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2010-0622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaaimi B, Edgley SA, Soteropoulos DS, & Baker SN (2012). Changes in descending motor pathway connectivity after corticospinal tract lesion in macaque monkey. Brain, 135(Pt 7), 2277–2289. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]