Abstract

To improve women’s access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in family planning (FP) clinics, we examined readiness to provide PrEP, and barriers and facilitators at the clinic level to integrate PrEP services into Title X-funded FP clinics across the Southern US. Title X-funded FP clinics across DHHS regions III (Mid-Atlantic), IV (Southeast), and VI (Southwest), comprising the Southern US. From February to June, 2018, we conducted a web-based, geographically targeted survey of medical staff, providers and administrators of Title X-funded FP clinics in DHHS regions III (Mid-Atlantic), IV (Southeast), and VI (Southwest). Survey items were developed using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to assess constructs relevant to PrEP implementation. One-fifth of 283 unique Title X clinics across the South provided PrEP. Readiness for PrEP implementation was positively associated with a climate supportive of HIV prevention, leadership engagement, and availability of resources, and negatively associated with providers holding negative attitudes about PrEP’s suitability for FP. The Title X FP network is a vital source of sexual health care for millions of individuals across the US. Clinic-level barriers to providing PrEP must be addressed to expand onsite PrEP delivery in Title X FP clinics in the Southern US.

Keywords: Southern US, Women, PrEP, HIV prevention, Family planning, Implementation

Introduction

In the United States (US), nearly 40,000 people are diagnosed with HIV annually, and 1.2 million individuals are living with HIV [1]. More than half of all new HIV diagnoses occur in the Southern US, despite making up 38% of the US population [1]. While men who have sex with men continue to be overrepresented in new HIV diagnoses, women also face a substantial burden of HIV [2]. In 2017, 19% of new HIV diagnoses in the US were among women [3], with Black women accounting for 69% of all HIV diagnoses among women in the South [4]. Thus, reducing HIV among women living in the Southern US remains a public health priority.

The Department of Health and Human Services’ (DHHS), Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America [5], has identified 4 strategic initiatives to achieve an end to the US HIV epidemic by 2030. One key initiative is to protect people at risk using proven HIV prevention interventions, including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Since the 2012 FDA approval of daily oral PrEP [6], there has been wide-scale endorsement to bring PrEP to scale in the US [7–9]. However, PrEP remains underutilized among women relative to need, and women are less than 5% of US PrEP users [10–12].

According to dissemination and implementation science, the first steps in adoption of a new health care innovation like PrEP are to ensure that those who can benefit are aware of it (e.g., women at risk for HIV are knowledgeable about PrEP) and to ensure the intervention is accessible in settings where they seek care (e.g., PrEP is offered in women’s health settings) [13]. The Title X Family Planning Program supports a nationwide network of approximately 4000 service sites that serve approximately four million clients annually, ~ 90% of whom are women [14, 15]. Rather than primary care or STI clinics, most women utilize and trust family planning clinics for sexual health services [16, 17]. Title X was designed to ensure confidential access to contraception regardless of age, particularly for low-income individuals, but also funds the provision of many preventive health services (e.g., HIV testing). For most female clients, Title X clinics serve as their usual source of medical care [18], particularly in many Southern states that have not expanded Medicaid [19].

While clinical guidelines for women’s health providers have recently incorporated recommendations for PrEP [20], the extent to which Title X clinics, especially in the South, are providing PrEP is largely unknown. Among Title X clinics not offering PrEP, virtually nothing is known about their capacity and readiness to begin implementing PrEP beyond assessment of provider attitudes, knowledge, and intentions for prescribing PrEP [21, 22]. A 2015 national survey of family planning providers found low PrEP knowledge, especially in the South [21]. Only one-third of respondents overall could correctly define PrEP and its efficacy, less than 5% had ever prescribed PrEP, and most felt uncomfortable prescribing PrEP due to lack of training.

In line with findings conducted among other healthcare providers (e.g., primary care, STI clinic, and infectious diseases) [23–29], family planning providers had high willingness to prescribe and interest in being educated about PrEP [21]. However, beyond PrEP-specific provider education and training, virtually nothing is known about the prioritization, capacity, barriers, and facilitators at the clinic level (e.g., implementation climate, leadership engagement, available resources) to integrate PrEP services into these potentially ideal clinical settings for reaching women. To begin filling these gaps, we conducted a geographically-targeted survey among providers, medical staff, and administrators of Title X-funded clinics across 18 Southern states. We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [30] to facilitate evaluation of internal clinic factors and the external contextual factors that may influence the successful adoption of PrEP services in Title X clinics in the Southern US.

Methods

Study Design and Population

From February through June of 2018, we conducted a web-based, geographically targeted survey of clinic medical staff, providers, and administrators of Title X family planning clinics in DHHS regions III (Washington D.C., Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia), IV (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee), and VI (Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas). The National Clinical Training Center for Family Planning (NCTCFP) supported our online recruitment of participants via listserv emails and advertisement on their website. Additional recruitment efforts included engagement with state Title X grantees and in-person recruitment at an NCTCFP national meeting.

A small number of surveys (13 of 755) were completed by respondents outside of the targeted Title X DHHS regions, thus excluded from analyses. Our analyses included all surveys where the question related to PrEP use in a respondent’s clinic was answered (n = 519). A comprehensive overview of the study’s protocol, data collection instruments, and statistical analysis methods has been published elsewhere [31]. Briefly, survey items were adapted from existing, validated measures of CFIR constructs (specifically, those for intervention characteristics, implementation climate, leadership engagement, available resources, PrEP knowledge, and PrEP attitudes) [21, 32–34] or developed by our study team using CFIRspecific tools to assess CFIR constructs relevant to PrEP implementation [30].

Definition of the CFIR Construct Outcomes

Outcomes were CFIR construct measures derived as semicontinuous composite scores based on collections of related survey items. The primary outcome was readiness for PrEP implementation. Key secondary outcomes included measures of implementation climate, leadership engagement, availability of resources, knowledge about PrEP, and attitudes about PrEP. Each outcome, except knowledge about PrEP, was derived as the mean of one or more Likert scale survey items that were identified as having high internal consistency based on Cronbach’s Alpha (see Table S1 and Table S2, Supplemental File 1) [35]. Knowledge about PrEP was derived as the number of correct responses identified by the respondent from a set of 5 questions.

We explored two separate dimensions for several of the CFIR constructs. Implementation climate was subdivided into HIV-related and general implementation climate constructs. Leadership engagement was subdivided into constructs for leadership supportive of PrEP and general leadership supportive of innovation/adoption of new practices. The available resources construct was subdivided into constructs for available resources specific to PrEP funding and general assessment of resources. The attitudes construct was subdivided into one for negative attitudes about PrEP and another for positive attitudes about PrEP.

Definition of the Covariates

Respondent-level covariates included self-reported race (White vs. non-White), ethnicity (Latino vs. non-Latino), age (in years), primary role at the clinic (administrator vs. medical staff/provider), years worked in primary role, and ability to prescribe medication (yes with or without a supervisor vs. no). Clinic-level covariates included respondent-report of their clinic’s PrEP-providing status (PrEP vs. non-PrEP), their clinic having staff that assist patients with enrolling in Medicaid and insurance programs (yes vs. no), having an on-site pharmacy (yes vs. no), and providing primary care services (yes vs. no). Sociodemographic covariates for the population of the clinic catchment area included HIV prevalence, percent uninsured, percent living in poverty, percent Latino, percent White, and percent of females aged 15 to 44 years based on county-level AIDSVu (2015) and US Census data (2010) [36, 37]. Since data from counties with a small number of cases and/or a small population size are suppressed in AIDSVu, for analysis we recoded suppressed values to the smallest positive HIV prevalence rate across the dataset. Using the 2013 NCHS urban–rural classification scheme [38], clinics were classified as metropolitan (i.e., urban, including large central or fringe metro, medium metro, and small metro areas) and nonmetropolitan (i.e., rural, including micropolitan and noncore counties) [38].

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4. Statistical tests were performed using a significance level of 0.05. Clinic address data were used to geographically describe the clinics with which the respondents were associated. For regression analyses, missing values for individual survey items and covariates were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) [39, 40] using full conditional specifications based on linear and logistic regression models for continuous and discrete survey items, respectively. All outcomes were analyzed using linear mixed models that included a clinic-specific random effect [41] to account for the possible correlation between respondents from the same clinic. The study’s pre-specified analysis plan is included in the published protocol [31]. Additional details about the study methods are provided in Expanded Methods, Supplemental File 2.

Results

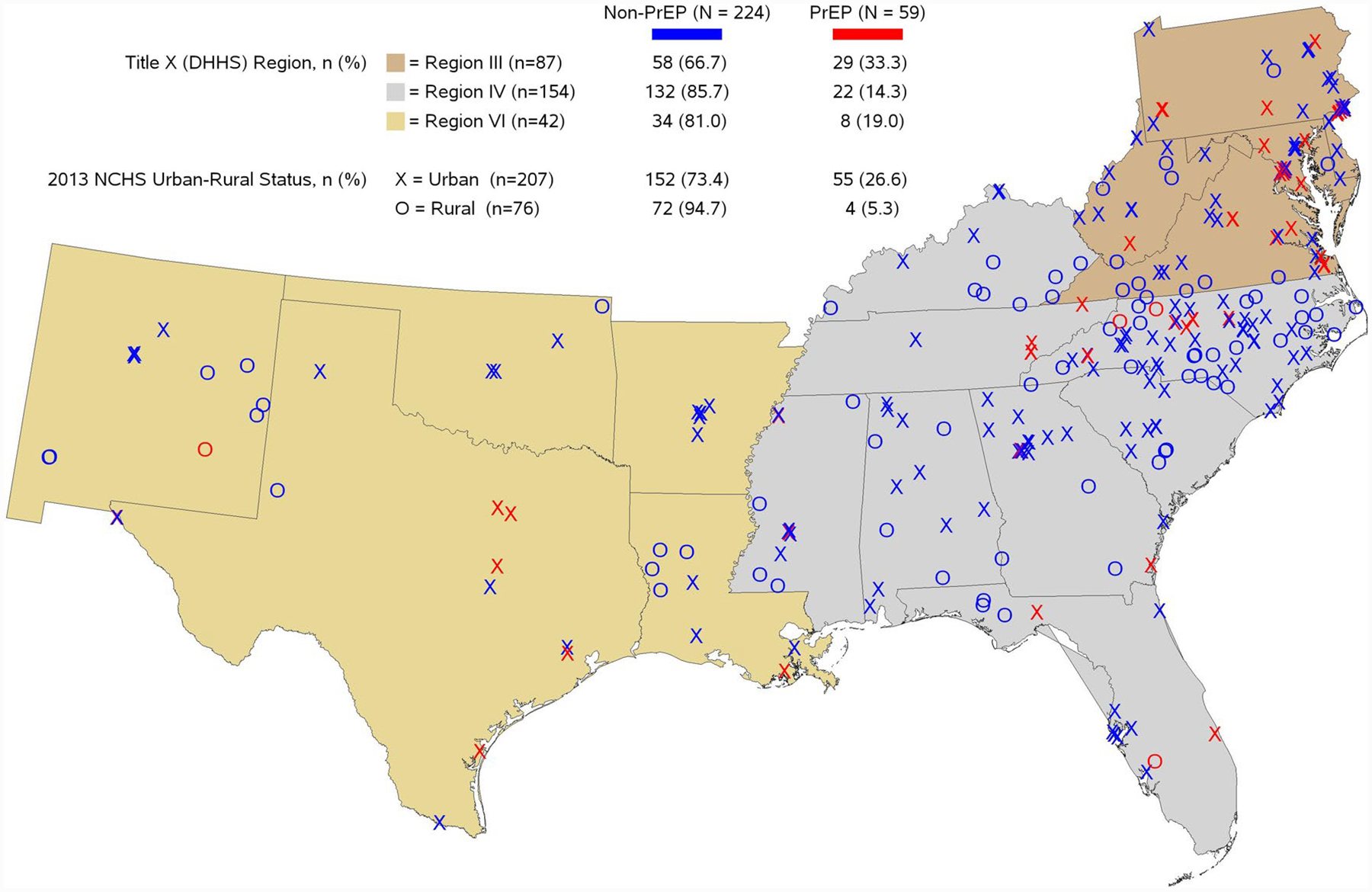

Among 742 respondents from an eligible Title X DHHS region who agreed to participate in the survey, 519 (69.9%) completed the survey. Summaries of respondent-level, clinic-level, and county-level characteristics are provided in Table 1. Region IV (Southeast) had more respondents compared to III (Mid-Atlantic) and VI (Southwest) (329 (63.4%) vs. 126 (24.3%) and 64 (12.3%), respectively). Most respondents were clinic providers or support staff (436 (84.0%) vs. 83 (16.0%) administrators) and were from clinics that did not provide PrEP (79.8% vs. 20.2% PrEP providing clinics). Using clinic address to identify instances where a clinic had multiple respondents, the median respondents per clinic was 1.0 (max = 12). For clinics with multiple respondents (n = 93), clinic’s PrEP providing status was defined as the majority response among the respondents from that clinic. For clinics where there was no majority agreement among the respondents (n = 8), the clinic’s PrEP providing status was classified as non-PrEP providing. Survey respondents represented 283 unique clinics across the three regions (30.7% in Region III, 54.4% in Region IV, and 14.8% in Region VI), with 76 (26.9%) of those clinics rurally-located (Fig. 1). Only 59 (20.9%) clinics provided PrEP (33.3% of clinics from Region III provide PrEP, 14.3% of clinics from Region IV, and 19.0% of clinics from Region VI); only four PrEP providing clinics were rurally-located. Figures S1.1–S1.5 in Supplemental File 3, depict mean differences between PrEP versus Non-PrEP providing respondents on several CFIR derived implementation factors, by region and urbanicity.

Table 1.

Description of characteristics for respondents by title X region and clinic PrEP providing status, among respondents from title X clinics in regions III, IV, and VI, February–June 2018

| Variable | Region III | Region IV | Region VI | Overall (N = 519) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-PrEP (N = 82) | PrEP (N = 44) | Non-PrEP (N = 287) | PrEP (N = 42) | Non-PrEP (N = 45) | PrEP (N = 19) | ||

| Respondent-level | |||||||

| Age (in years), mean (SD) | 50.3 (12.42) | 49.8 (11.04) | 44.3 (11.54) | 42.9 (11.35) | 48.9 (11.16) | 37.3 (13.06) | 45.7 (12.00) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||

| Latino/Latina/Latinx | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | 7 (15.6) | 5 (26.3) | 21 (4.0) |

| Not Latino/Latina/Latinx | 68 (82.9) | 42 (95.5) | 249 (86.8) | 35 (83.3) | 35 (77.8) | 12 (63.2) | 441 (85.0) |

| Prefer not to answer/missing | 13 (15.9) | 2 (4.5) | 31 (10.8) | 6 (14.3) | 3 (6.7) | 2 (10.5) | 57 (11.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 (1.2) | 2 (4.5) | 5 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) | 9 (1.7) |

| Black/African-American | 8 (9.8) | 13 (29.5) | 51 (17.8) | 3 (7.1) | 6 (13.3) | 4 (21.1) | 85 (16.4) |

| Native American/Alaskan Native | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| White | 55 (67.1) | 23 (52.3) | 184 (64.1) | 26 (61.9) | 34 (75.6) | 10 (52.6) | 332 (64.0) |

| Other | 1 (1.2) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (15.8) | 9 (1.7) |

| More than one race | 3 (3.7) | 3 (6.8) | 7 (2.4) | 6 (14.3) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (3.9) |

| Prefer not to answer/missing | 14 (17.1) | 2(4.5) | 36 (12.5) | 5 (11.9) | 4 (8.9) | 1 (5.3) | 62 (11.9) |

| Role(s) at clinic, n (%) | |||||||

| Manager, administrator, or center coordinator | 14 (17.1) | 9 (20.5) | 39 (13.6) | 10 (23.8) | 14 (31.1) | 4 (21.1) | 90 (17.3) |

| Clinical provider (NP, CNM, PA, MD, DO) | 45 (54.9) | 25 (56.8) | 102 (35.5) | 18 (42.9) | 19 (42.2) | 3 (15.8) | 212 (40.8) |

| Nurse | 19 (23.2) | 11 (25.0) | 139 (48.4) | 15 (35.7) | 20 (44.4) | 2 (10.5) | 206 (39.7) |

| Health Educator, Counselor, Health Care Associate, Medical Assistant, or Patient Navigator, n (%) | 17 (20.7) | 6 (13.6) | 48 (16.7) | 12 (28.6) | 6 (13.3) | 10 (52.6) | 99 (19.1) |

| Other provider | 2 (2.4) | 2 (4.5) | 4 (1.4) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (2.1) |

| Other administrator | 3 (3.7) | 3 (6.8) | 5 (1.7) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (6.7) | 1 (5.3) | 16 (3.1) |

| Primary role at clinic, n (%) | |||||||

| Administrator | 10 (12.2) | 7 (15.9) | 41 (14.3) | 9 (21.4) | 12 (26.7) | 4 (21.1) | 83 (16.0) |

| Provider | 72 (87.8) | 37 (84.1) | 246 (85.7) | 33 (78.6) | 33 (73.3) | 15 (78.9) | 436 (84.0) |

| Years worked in primary role, mean (SD) | 10.1 (9.21) | 9.0 (8.06) | 6.8 (7.17) | 6.8 (6.57) | 10.5 (9.42) | 4.2 (5.51) | 7.7 (7.86) |

| Able to prescribe medications, n (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 45 (54.9) | 24 (54.5) | 102 (35.5) | 18 (42.9) | 19 (42.2) | 3 (15.8) | 211 (40.7) |

| No | 37 (45.1) | 19 (43.2) | 185 (64.5) | 24 (57.1) | 26 (57.8) | 16 (84.2) | 307 (59.2) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Inner setting: readiness for implementation, mean (SD) | 3.8 (0.56) | – | 3.6 (0.59) | – | 3.1 (0.78) | – | 3.6 (0.63) |

| Inner setting: implementation climate—HIV-specific measure, mean (SD) | 3.5 (0.63) | – | 3.3 (0.63) | – | 3.3 (0.68) | – | 3.3 (0.64) |

| Inner setting: implementation climate—general measure, mean (SD) | 3.8 (0.76) | 3.9 (1.11) | 3.7 (0.80) | 3.8 (0.62) | 3.6 (0.90) | 4.0 (0.88) | 3.8 (0.82) |

| Knowledge, mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.69) | 4.5 (1.13) | 2.7 (1.84) | 3.9 (1.49) | 2.4 (1.72) | 4.6 (0.84) | 3.0 (1.82) |

| Inner setting: leadership engagement—PrEP-specific measure, mean (SD) | 3.5 (0.86) | – | 3.4 (0.81) | – | 3.2 (0.79) | – | 3.4 (0.82) |

| Inner setting: leadership engagement—general measure, mean (SD) | 3.6 (0.86) | 3.7 (1.09) | 3.5 (0.87) | 3.7 (0.67) | 3.5 (1.04) | 3.8 (0.81) | 3.5 (0.89) |

| Inner setting: available resources—PrEP-specific funding, mean (SD) | 3.2 (0.86) | – | 3.4 (0.83) | – | 3.3 (0.86) | – | 3.3 (0.84) |

| Inner setting: available resources—general assessment of resources, mean (SD) | 3.0 (0.87) | 3.5 (0.96) | 2.9 (0.82) | 3.2 (0.83) | 2.5 (0.94) | 3.5 (0.72) | 3.0 (0.88) |

| Characteristics of Individuals: negative attitudes about PrEP, mean (SD) | 2.4 (0.58) | 1.8 (0.63) | 2.7 (0.59) | 2.2 (0.61) | 2.6 (0.62) | 2.3 (0.43) | 2.5 (0.64) |

| Characteristics of individuals: positive attitudes about PrEP, mean (SD) | 3.4 (0.83) | 3.5 (0.80) | 3.1 (1.01) | 3.4 (0.84) | |||

| Clinic-level | |||||||

| 2013 NCHS Urban-Rural county classification, n (%) | |||||||

| Urban | 60 (73.2) | 44 (100.0) | 204 (71.1) | 34 (81.0) | 29 (64.4) | 18 (94.7) | 389 (75.0) |

| Rural | 22 (26.8) | 0 (0.0) | 83 (28.9) | 8 (19.0) | 16 (35.6) | 1 (5.3) | 130 (25.0) |

| Primary Care Services provided by clinic, n (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 17 (20.7) | 17 (38.6) | 118 (41.1) | 16 (38.1) | 7 (15.6) | 13 (68.4) | 188 (36.2) |

| No | 65 (79.3) | 27 (61.4) | 169 (58.9) | 25 (59.5) | 38 (84.4) | 6 (31.6) | 330 (63.6) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Respondent’s clinic has staff who assist patients with enrolling in Medicaid, insurance programs, or Family Planning Waivers, n (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 49 (59.8) | 34 (77.3) | 200 (69.7) | 29 (69.0) | 28 (62.2) | 14 (73.7) | 354 (68.2) |

| No/I don’t know | 33 (40.2) | 9 (20.5) | 87 (30.3) | 13 (31.0) | 17 (37.8) | 5 (26.3) | 164 (31.6) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Respondent’s clinic has a pharmacy on site, n (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 18 (22.0) | 17 (38.6) | 148 (51.6) | 24 (57.1) | 27 (60.0) | 16 (84.2) | 250 (48.2) |

| No/I don’t know | 62 (75.6) | 27 (61.4) | 139 (48.4) | 18 (42.9) | 17 (37.8) | 3 (15.8) | 266 (51.3) |

| Missing | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) |

| County-level | |||||||

| HIV prevalence rate (per 100,000 population), mean (SD) | 633 (830.7) | 813 (823.0) | 434 (405.6) | 512 (459.6) | 297 (238.4) | 505 (219.0) | 495 (543.3) |

| Females 15 to 44 years (%), mean (SD) | 20.7 (4.27) | 23.1 (4.03) | 20.1 (2.68) | 21.1(3.28) | 19.9 (2.16) | 21.6 (1.04) | 20.5 (3.20) |

| Hispanic or Latino (%), mean (SD) | 5.3 (4.43) | 6.1 (3.80) | 6.7 (4.16) | 7.2 (5.97) | 29.3 (26.89) | 38.9 (17.46) | 9.6 (12.76) |

| White Race (%), mean (SD) | 70.8 (24.52) | 61.2 (19.71) | 66.9 (18.35) | 69.3 (19.96) | 70.4 (11.45) | 62.6 (9.53) | 67.4 (19.11) |

| Uninsured (%), mean (SD) | 8.9 (2.75) | 9.1 (3.63) | 13.7 (2.66) | 14.0 (3.37) | 14.9 (5.60) | 19.8 (2.71) | 12.9 (4.02) |

| Living in poverty (%), mean (SD) | 17.6 (6.43) | 16.7 (6.47) | 18.6 (5.03) | 18.1 (5.76) | 19.9 (3.52) | 17.4 (2.22) | 18.3 (5.33) |

SD standard deviation

More than one response option may be selected for role(s) at clinic and services provided by clinic, so these categories are not mutually exclusive

Responses are considered missing if no response was selected for this question

Clinic urban–rural status was defined using the 2013 NCHS urban–rural classification scheme for counties where Metropolitan (urban) includes large central or fringe metro, medium metro, and small metro and Nonmetropolitan (rural) includes micropolitan and noncore counties

Fig. 1.

Represented Clinics by Urban–Rural and PrEP Providing Status, among Respondents from Title X Clinics in Regions III, IV, and VI, February–June 2018. Note. Clinic urban–rural status was defined using the 2013 NCHS urban–rural classification scheme for counties where Metropolitan (urban) includes large central or fringe metro, medium metro, and small metro and Nonmetropolitan (rural) includes micropolitan and noncore counties

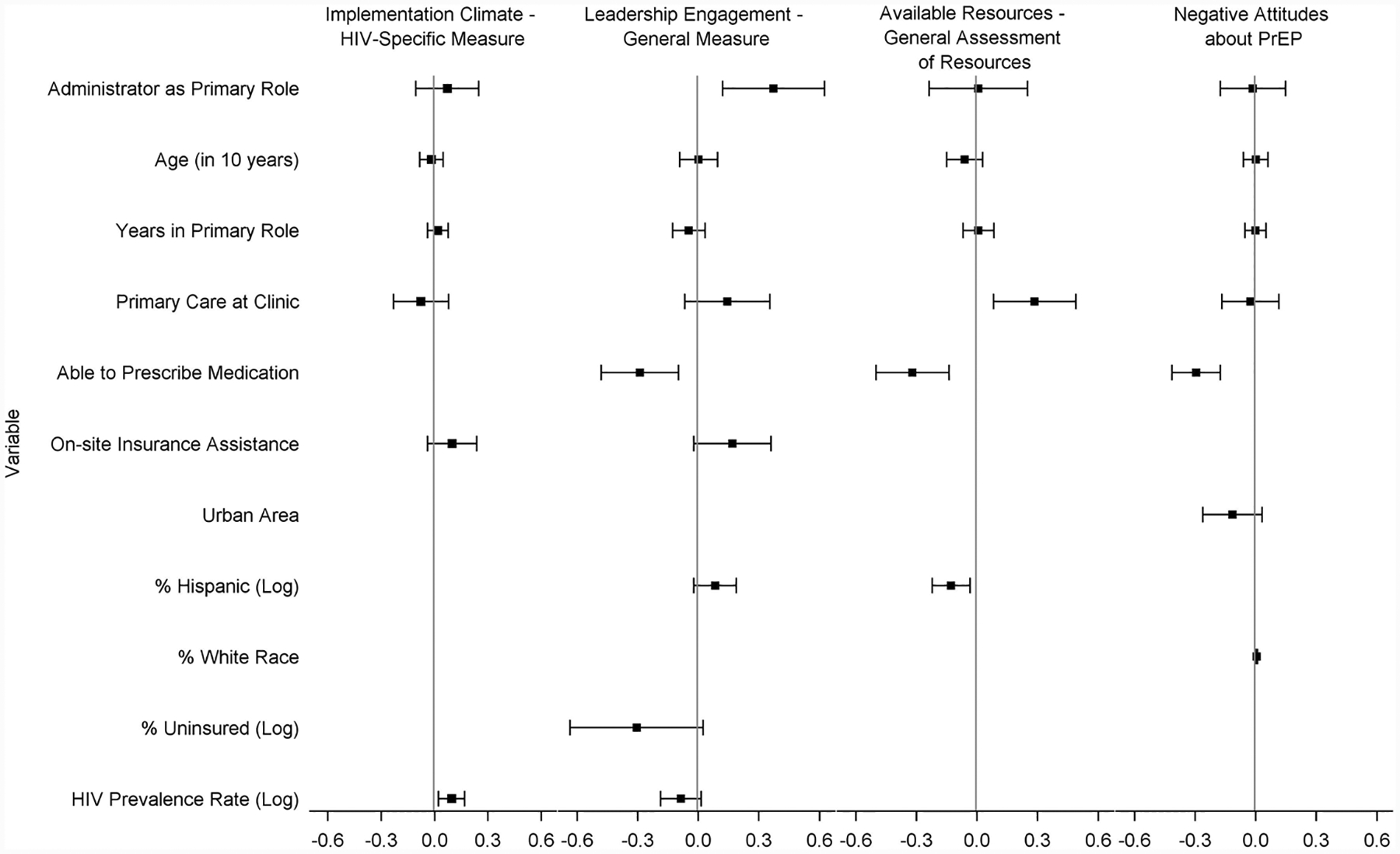

The survey was created so that only respondents from non-PrEP providing clinics completed survey items comprising the readiness for PrEP implementation outcome; therefore, only non-PrEP providing clinic respondents were included in the CFIR construct outcomes model analyses (n = 414). For constructs with both a general and HIV/PrEP-specific measure, the observed correlation was low which supported our inclusion of both constructs in the readiness for implementation outcome model (See Table S3, Supplemental File 1). Presented results are based on models that removed covariates that were not of interest a priori and for which the data indicated no evidence of association using a backward selection approach. Though results of the full and reduced models were consistent, Supplemental File 1 includes results based on the full models. The reduced model (Fig. 2) demonstrated a significant positive association between readiness for PrEP implementation and the HIV-specific implementation climate (0.12 (95% CI 0.02, 0.23)), general leadership engagement (0.11 (95% CI 0.03, 0.19)), and general assessment of resources (0.14 (95% CI 0.07, 0.21)), and a negative association between readiness for PrEP implementation and negative attitudes about PrEP (− 0.15 (95% CI − 0.25, − 0.05)). The associations for general assessment of resources and negative attitudes about PrEP remained significant with conservative Bonferroni p value correction. Providing primary care services and percent of the clinic’s county living in poverty were the only other covariates significantly associated with readiness to implement PrEP (0.17 (95% CI 0.03, 0.31) and − 0.01 (95% CI − 0.03, − 0.001), respectively; see Table S4, Supplemental File 1).

Fig. 2.

Linear Mixed Model Results for the Primary Endpoint, Inner Setting: Readiness for Implementation, among Respondents from Non-PrEP Providing Title X Clinics in Regions III, IV, and VI, February–June 2018. Note: HIV-Specific Climate = Implementation Climate: HIV-Specific Measure, General Climate = Implementation Climate: General Measure, Knowledge = Knowledge about PrEP, PrEP-Specific Engagement = Leadership Engagement: PrEP-Specific Measure, General Engagement = Leadership Engagement: General Measure, PrEP-Specific Funding Resources = Available Resources: PrEP-Specific Funding, General Assessment of Resources = Available Resources: General Assessment of Resources, Negative Attitudes = Negative Attitudes about PrEP, Positive Attitudes = Positive Attitudes about PrEP, Primary role as administrator versus a provider. Primary Care at Clinic = Respondent’s Clinic offers primary care services. The percent variables are the percents or log transformed percents among the county population where the respondent’s clinic is located and based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2010 Census and AIDSVu. The points indicate linear mixed model estimate and whiskers indicate unadjusted 95% confidence intervals

Figure 3 includes model results for the four CFIR constructs that were associated with readiness for PrEP implementation. HIV prevalence in the clinic’s catchment area was significantly associated with HIV-specific implementation climate (0.10 (95% CI 0.02, 0.17); see Table S5.1, Supplemental File 1). The respondent’s primary role and ability to prescribe medication were significantly associated with general leadership engagement (0.37 (95% CI 0.12, 0.62); − 0.29 (95% CI − 0.48, − 0.10); see Table S5.2, Supplemental File 1). The percent Latino in the clinic’s catchment area, the respondent’s clinic providing primary care services, and the respondent’s ability to prescribe medication were significantly associated with general assessment of resources (0.28 (95% CI 0.08, 0.49); − 0.13 (95% CI − 0.22, − 0.04); − 0.32 (95% CI − 0.50, − 0.14); see Table S5.3, Supplemental File 1). The respondent’s ability to prescribe medication was significantly associated with negative attitudes about PrEP (− 0.30 (95% CI − 0.42, − 0.18); see Table S5.4, Supplemental File 1).

Fig. 3.

Linear Mixed Model Results for Key Secondary Endpoints, Implementation Climate—HIV-Specific Measure, Leadership Engagement—General Measure, Available Resources—General Assessment of Resources, and Negative Attitudes about PrEP, among Respondents from Non-PrEP Providing Title X Clinics in Regions III, IV, and VI, February–June 2018. Note: Primary role as administrator versus a provider. Primary Care at Clinic = Respondent’s Clinic offers primary care services. The percent and prevalence rate variables are the percents or log transformed percents or rate among the county population where the respondent’s clinic is located and based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2010 Census and AIDSVu. The points indicate linear mixed model estimate and whiskers indicate unadjusted 95% confidence intervals

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that most participating Title X clinics in the Southern US did not provide PrEP. Similar to recent findings denoting the South as a PrEP desert for men who have sex with men based upon few PrEP providers [42], our study indicates that only one-fifth of 283 unique Title X clinics across the South were providing PrEP. There was noticeable variation across the South, with proportionately fewer PrEP-providing Title X clinics in the Southeast and Southwest compared to the Mid-Atlantic states, and incredibly limited PrEP access in rural areas. Improving PrEP access in places women seek sexual health care remains a critical priority in the South, which experiences the greatest burden of the current HIV epidemic.

Slow adoption of new evidence-based practices, like PrEP, is a widespread concern among healthcare systems [43, 44], with some noting up to a 20-year lag before a new evidence-based practice is widely integrated into routine care [45]. Organizations have difficulty systematically implementing new practices, often due to challenges coordinating change across a practice setting, rather than lack of recognizing the new practice as relevant and desirable [43, 46]. Our findings support this such that PrEP knowledge, a widely cited provider-level barrier to PrEP implementation, was not associated with perceived readiness to provide PrEP care. Instead, in line with the implementation science literature, we found that having a climate supportive of HIV prevention practices, supportive leadership, availability of resources, and individual attitudes about PrEP’s suitability for family planning were the salient factors associated with readiness to provide PrEP [47].

Successful adoption of new evidence-based practices into healthcare settings has been characterized by organizational factors, including provider/staff and administrators’ readiness to implement the new practice (to what degree is it possible), their attitudes about the new practice individually (is it desirable) as well as collectively (climate supportive of new practices), leadership support (making the change a priority), and adequacy of resources (training, staffing, and financial) [48]. When these factors are collectively present before the adoption of a new practice, they may indicate an organization’s readiness to make the change (i.e., adopt/implement the new practice), and have predicted successful implementation [48–50]. Thus, Title X clinics with higher levels of readiness for PrEP implementation across the Southern US may be prime sites for immediate allocation of additional support, such as educational interventions or supplemental financial support to offset delivery costs—two commonly cited barriers to PrEP service provision [23–28, 51], to help them move from PrEP readiness to implementation. Title X clinics with lower PrEP readiness may require more robust, time-intensive interventions to address challenges with organizational climate, leadership engagement, and more substantial resource constraints (e.g., staffing) identified as salient in our study.

Title X clinics comprise the largest federally-funded sexual health network across the US [15]. However, each service site is a unique organization, operating within different social and political environments (e.g., Medicaid expansion, state-level PrEP assistance programs). Our findings suggest that understanding the organizational readiness for providing PrEP of individual clinics, particularly in high HIV burden regions like the Southern US, through a similar survey assessment to the one conducted in our study, may be an important first step to appropriately matching the type and/or intensity of intervention necessary for facilitating PrEP provision in these important clinical care sites for women.

The national Title X network is large, so undertaking an organizational assessment for each clinical site is likely not feasible. Title X funding is allocated at the state-level, with most states’ Title X funding administered by a single grantee [15]. The state-level grantee(s) distributes Title X funds to clinical service sites to support provision of family planning and preventive services. Similar to how the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative has prioritized certain counties or states for receipt of additional funding to address HIV based on epidemiologically determined need in these communities [5], Title X service sites located in high HIV areas could first be prioritized for an organizational assessment, followed by targeted intervention efforts to support PrEP scale-up in geographic areas most heavily impacted by HIV. Our findings indicate that county-level HIV incidence was the only factor significantly associated with a more supportive climate for HIV services in Title X clinics, suggesting that sites in high burdened communities may be especially receptive to providing PrEP for prevention. Even a more targeted approach to understanding and then addressing barriers to providing PrEP in geographically-targeted Title X clinics would likely only be achievable with additional financial support to the state-level grantee and the focal service sites to offset known resource constraints associated with PrEP provision and monitoring.

The Title X network is also diverse, such that it is comprised of health department sites, hospitals- and/or academically-affiliated clinics, community-based clinics, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), and specialized family planning centers, among others (e.g., school-based health clinics). This diversity may affect scaling PrEP within the Title X network because these different types of service sites provide varying health services in addition to family planning (e.g., primary care). Though the majority of Title X service sites across the South are health departments [52], some states’ like Georgia’s Title X service sites are predominately FQHCs with integrated Title X family planning services within their community-based primary care clinics. Our study found that the provision of primary care was associated with greater readiness to provide PrEP. Provision of primary care was also associated with greater perceived resource availability to adopt new practices like PrEP. Primary care providers have been identified as ideal providers of PrEP, given that PrEP is a preventative intervention for otherwise healthy people, and they are accustomed to supporting long-term monitoring of health care needs [53]. Thus, Title X clinics that also offer primary care may be good initial sites for improving access to PrEP for women in the South, as they may require less intervention/support to begin offering PrEP.

Even though some clinical environments may be more supportive of PrEP services, the prescribing provider is at the heart of PrEP care. Prior research conducted in 2015 found that family planning providers, though lacking knowledge about PrEP, indicated they would be more likely to prescribe PrEP with additional training [21]. Our findings indicate that negative attitudes about PrEP and its suitability for family planning clinics was associated with less readiness to implement PrEP. Further, being a prescribing provider was one of the only factors significantly associated with holding negative attitudes about PrEP, and was also associated with lower perceived resources to adopt new practices. Even as knowledge about PrEP increases among providers, prescribing providers may still have concerns about how adding PrEP counseling, labs, and monitoring would add substantial time to an already limited visit allowance per patient. Educational interventions and trainings for Title X providers should address concerns about PrEP and its suitability for family planning clinics. Additionally, clinic leadership should work with providers and staff to create PrEP implementation plans that streamline and distribute the tasks associated with PrEP (e.g., screening, education, tests, and monitoring) across clinic staff to offset the time of PrEP care falling solely on providers. Such task-shifting models of PrEP care have been successfully implemented in other resource-constrained environments like STI clinics [54–57].

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Ours was a convenience sample of clinic providers and administrators, thus may be subject to selection bias. Clinic characteristics were provided by self-report rather than direct observations. Finally, the study was conducted among staff of Title X funded-family planning clinics, and therefore findings may not be generalizable across other women’s health settings. Nonetheless, a key strength of this study was the large sample size, along with the diversity of geographic location and clinic characteristics among the clinics represented by study participants.

Conclusion

The Title X family planning network is a vital source of sexual health care for millions of individuals across the US, including mostly women, but also growing numbers of men. For many women, especially in states that did not expand Medicaid, Title X clinics serve as their sole source of health care. Importantly, in 2017 alone, Title X clinics performed 1,192,119 confidential HIV tests resulting in 2195 new HIV diagnoses [58]. However, to date, there has been limited discussion of the role of this vital safety net in achieving the ambitious targets set forth by the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative. The Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative should leverage and expand on the important role that this network of family planning clinics has always played in providing HIV testing and preventive services to the 4 million people they serve each year.

At this critical juncture for ending the HIV epidemic, our study indicates that clinic-level barriers to providing PrEP, particularly resource concerns related to training, cost, and staffing, must be addressed to expand onsite PrEP delivery in these otherwise ideal PrEP-delivery sites for women. At a minimum, all Title X clinics should be provided with the support and resources to provide universal PrEP education to their patients, particularly in the South, where the epidemic burden is high and PrEP awareness among women remains low [59]. Until PrEP capacity is built within the Title X network, in the current absence of robust PrEP service offering within Title X clinics across the South, linkages between Title X clinics and established PrEP programs must be strengthened in the region, particularly in rural areas. Additionally, alternative PrEP delivery models such as telemedicine and pharmacy-based models that occur outside of the clinic setting must also be adapted for and studied in women to ensure they are acceptable and accessible.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant U24HD089880. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. A. Sheth receives funding from the National Institutes of Health (K23AI114407). L. Haddad’s effort is supported by the National Institutes of Health (K23HD078153).

Footnotes

Supplementary information The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03120-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of interest J Sales received grant funding for an Investigator Sponsored Grant from Gilead Sciences, Inc. (CO-US-276-4060). A. Sheth also received grant funding from Gilead Sciences.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV surveillance report, vol 28. 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2016-vol-28.pdf. Published August 2016. Accessed 1 Sept 2019.

- 2.Hodder SL, Justman J, Haley DF, et al. Challenges of a hidden epidemic: HIV prevention among women in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV Among Women. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html. Published March 2019. Accessed 27 June 2019.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC issue brief: HIV in the Southern United States. Updated May 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/cdc-hiv-in-the-south-issue-brief.pdf. Published May 2016. Accessed 27 June 2019.

- 5.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–5. 10.1001/jama.2019.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA approves first drug for reducing the risk of sexually acquired HIV infection. Washington, DC, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). High impact HIV prevention programs. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/highimpactprevention/hiv-prevention-programs.html. Published October 2019. Accessed 1 Dec 2019.

- 8.NIH HIV/AIDS Research Priorities and Guidelines for Determining AIDS Funding. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-15-137.html. Published August 2015. Accessed 1 Sept 2018.

- 9.Young I, McDaid L. How acceptable are antiretrovirals for the prevention of sexually transmitted HIV?: a review of research on the acceptability of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis and treatment as prevention. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):195–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Grey J. Estimates of adults with indications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by jurisdiction, transmission risk group, and race/ethnicity, United States, 2015. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):850–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang YA, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N, Hoover KW. HIV preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity—United States, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1147–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, et al. The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis-toneed ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):841–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury MJ, Kaplan RM, Hunter C. National Institutes of Health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1274–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health and Human Services. Program requirements for title X funded family planning projects. 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/opa/guidelines/program-guidelines/program-requirements/index.html. Published July 2019. Accessed 27 Jan 2020.

- 15.Fowler CI, Gable J, Wang J, Lasater B, Wilson E. Family planning annual report: 2018 national summary. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International. 2019. Published August 2019. Accessed 23 Dec 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, Charles V. Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(2):102–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stormo AR, Saraiya M, Hing E, Henderson JT, Sawaya GF. Women’s clinical preventive services in the United States: who is doing what? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1512–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost JJ, Gold RB, Bucek A. Specialized family planning clinics in the United States: why women choose them and their role in meeting women’s health care needs. Women’s Health Issues. 2012;22(6):e519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones RK, Sonfield A. Health insurance coverage among women of reproductive age before and after implementation of the affordable care act. Contraception. 2016;93(5):386–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus. Committee Opinion No. 595. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:1133–6. Reaffirmed, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seidman D, Carlson K, Weber S, Witt J, Kelly PJ. United States family planning providers’ knowledge of and attitudes towards preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a national survey. Contraception. 2016;93(5):463–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood BR, McMahan VM, Naismith K, Stockton JB, Delaney LA, Stekler JD. Knowledge, practices, and barriers to HIV preexposure prophylaxis prescribing among Washington state medical providers. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(7):452–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1712–21. 10.1007/s10461-014-0839-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karris MY, Beekmann SE, Mehta SR, Anderson CM, Polgreen PM. Are we prepped for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? provider opinions on the real-world use of PrEP in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(5):704–12. 10.1093/cid/cit796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mimiaga MJ, White JM, Krakower DS, Biello KB, Mayer KH. Suboptimal awareness and comprehension of published preexposure prophylaxis efficacy results among physicians in Massachusetts. AIDS Care. 2014;26(6):684–93. 10.1080/09540121.2013.845289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White JM, Mimiaga MJ, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. Evolution of Massachusetts physician attitudes, knowledge, and experience regarding the use of antiretrovirals for HIV prevention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(7):395–405. 10.1089/apc.2012.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tripathi A, Ogbuanu C, Monger M, Gibson JJ, Duffus WA. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection: healthcare providers’ knowledge, perception, and willingness to adopt future implementation in the southern US. South Med J. 2012;105(4):199– 206. 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31824f1a1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tellalian D, Maznavi K, Bredeek UF, Hardy WD. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV infection: results of a survey of HIV healthcare providers evaluating their knowledge, attitudes, and prescribing practices. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(10):553–9. 10.1089/apc.2013.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaeer K, Sherman E, Shafiq S, Hardigan P. Exploratory survey of Florida pharmacists’ experience, knowledge, and perception of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(6):610–7. 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.14014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;7(4):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sales JM, Escoffery C, Hussen SA, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis integration into family planning services at title X clinics in the Southeastern United States: a geographically-targeted mixed methods study (Phase 1 ATN 155). JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(6):e12774. 10.2196/12774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norton WE. An exploratory study to examine intentions to adopt an evidence-based HIV linkage-to-care intervention among state health department AIDS directors in the United States. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ehrhart MG, Aarons GA, Farahnak LR. Assessing the organizational context for EBP implementation: the development and validity testing of the Implementation Climate Scale (ICS). Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Helfrich CD, Li YF, Sharp ND, Sales AE. Organizational readiness to change assessment (ORCA): development of an instrument based on the Promoting Action on Research in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cronbach LJJP. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 36.AIDSVu. 2015 HIV prevalence data. Emory University, Rollins School of Public Health. Atlanta, GA. www.aidsvu.org. Accessed 18 Nov 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics. 2010. 2010 Demographic Profile Data. U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census. https://factfinder.census.gov. Accessed 13 Nov 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS urban–rural classification scheme for counties. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2014;2(166):1–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Buuren S Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(3):219–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. L. Erlbaum Associates; 1983. ISBN: 9780898592689. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegler A, Bratcher B, Weiss KM. Geographic access to preexposure prophylaxis clinics among men who have sex with men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(9):1216–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. 2003;289(15):1969–75. 10.1001/jama.289.15.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balas EA, Boren SA. In: Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. Yearbook of Medical Informatics. Medicine NLo. Bethesda MD, editor. 2000. pp. 65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dopson S, Locock L, Chambers D, Gabbay J. Implementation of evidence-based medicine: evaluation of the Promoting Action on Clinical Effectiveness programme. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2001;6:23–31. 10.1258/1355819011927161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Commun Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):327–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holt D, Armenakis A, Harris S, Feild H. Toward a comprehensive definition of readiness for change: a review of research and instrumentation. Research in Organizational Change and Development. Amsterdam: JAI Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Armenakis AA, Harris SG, Mossholder KW. Creating readiness for organizational change. Hum Relat. 1993;46(6):681–703. 10.1177/001872679304600601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiner BJ, Amick H, Lee SYD. Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: a review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(4):379–436. 10.1177/1077558708317802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sales JM, Piper K, Escoffery C, Sheth A. Where can Southern girls go for PrEP? Examining the PrEP-providing practices of Title X-funded family planning clinics across the Southern US. Paper to be presented at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, March 2020. San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Department of Health and Human Services. Title X family planning grantees November 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/opa/title-x-family-planning/title-x-grantees/archive/index.html. Published November 2019. Accessed 23 Dec 2019.

- 53.Silapaswan A, Krakower D, Mayer KH. Pre-exposure prophylaxis: a narrative review of provider behavior and interventions to increase PrEP implementation in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):192–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pinto RM, Berringer KR, Melendez R, Mmeje O. Improving PrEP implementation through multilevel interventions: a synthesis of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(11):3681–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saberi P, Berrean B, Thomas S, Gandhi M, Scott H. A simple pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) optimization intervention for health care providers prescribing PrEP: pilot study. JMIR Form Res. 2018;2(1):e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spinelli MA, Scott HM, Vittinghoff E, et al. Brief report: a panel management and patient navigation intervention is associated with earlier PrEP initiation in a safety-net primary care health system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;79(3):347–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reback CJ, Clark KA, Runger D, Fehrenbacher AE. A promising PrEP navigation intervention for transgender women and men who have sex with men experiencing multiple syndemic health disparities. J Commun Health. 2019;44(6):1193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/opa/title-x-family-planning/fp-annual-report/fpar-infographic/index.html. Published August 2019. Accessed 30 Dec 2019.

- 59.Sales JM, Phillips AL, Tamler I, Munoz T, Cwiak C, Sheth AN. Patient recommendations for PrEP information dissemination at family planning clinics in Atlanta, Georgia. Contraception. 2019;99(4):233–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.