Abstract

Objective:

We examined factors influencing end-of-life care preferences among persons living with HIV (PLWH).

Methods:

223 PLWH were enrolled from 5 hospital-based clinics in Washington, DC. They completed an end-of-life care survey at baseline of the FACE™-HIV Advance Care Planning clinical trial.

Findings:

The average age of patients was 51 years. 56% were male, 66% heterosexual, and 86% African American. Two distinct groups of patients were identified with respect to end-of-life care preferences: (1) a Relational class (75%) who prioritized family and friends, comfort from church services, and comfort from persons at the end-of-life; and (2) a Transactional/Self-Determination class (25%) who prioritized honest answers from their doctors, and advance care plans over relationships. African Americans had 3x the odds of being in the Relational class versus the Transactional/Self-determination class, Odds ratio = 3.30 (95% CI, 1.09, 10.03), p = 0.035. Males were significantly less likely to be in the relational latent class, Odds ratio = 0.38 (CI, 0.15, 0.98), p = 0.045. Compared to non-African-Americans, African-American PLWH rated the following as important: only taking pain medicines when pain is severe, p = 0.0113; saving larger doses for worse pain, p = 0.0067; and dying in the hospital, p = 0.0285. PLWH who were sexual minorities were more afraid of dying alone, p = 0.0397, and less likely to only take pain medicines when pain is severe, p = 0.0091.

Conclusion:

Integrating culturally-sensitive palliative care services as a component of the HIV care continuum may improve health equity and person-centered care.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, palliative care, African American, sexual minority, gender, health disparities

Introduction

Palliative care is an essential component of the care continuum for persons living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).1 However, adult persons living with HIV (PLWH) are less likely than individuals with other serious illnesses to discuss advance care planning (ACP) or palliative care needs with clinicians, creating gaps in person-centered care.2–4 African-Americans (AAs) are impacted disproportionately by the HIV epidemic in the United States (US).5–8 African-Americans are 12% of the US population, but constitute 44% of PLWH.9 African-Americans, men who have sex with men (MSM) have the highest HIV prevalence, comprising 25% of PLWH [8].Due to this disproportionate HIV prevalence6–9 and the limited life-expectancy of PLWH,9–11 cultural and racial understanding from a patient-centered perspective is critical to improving patient care for PLWH.11

Fear of HIV stigma can be compounded by the stigma of poverty or sexual minority status.10–12 Risk factors for poor engagement along the HIV care continuum also include medical mistrust,5,10,13 negative religious coping,12,14,15 lack of health education, poor social support, and internalized homophobia.9–13 Understanding how these factors hinder the engagement of AA-PLWH in palliative or hospice care is a crucial step towards making systematic changes to enhance equitable access to and provision of palliative and hospice care.6,14 One aim of this ACP trial was to survey the palliative care needs of PLWH at baseline, prior to randomization.16

Methods

Setting

PLWH were recruited from 5 hospital-based HIV-clinics in Washington, DC from October 2013-March 2017. The trial was approved by the ethics committees of all study sties (Institutional Review Boards). A Safety Monitoring committee monitored the protocol yearly. All participants gave written informed consent.

Study Design and Participants

We conducted an ACP survey at baseline, prior to randomization, as part of the larger parent ACP clinical trial.16 The ACP parent trial was a multisite, 2 parallel-group, randomized controlled clinical trial with an intent-to-treat design. The design and methods for this study have been published previously.16 Inclusion criteria were: (1) adult PLWH aged ≥21 years; (2) ability to speak and understand English; and (3) diagnoses of HIV or AIDS. Exclusion criteria were screening positive for HIV dementia, homicidality, suicidality, or psychosis (assessed by a trained research assistant). Participants who screened positive were provided with appropriate referrals.

Procedures

Providers identified potentially eligible patients who were then approached by a trained research assistant during a clinic visit. Following informed consent, trained research assistants collected demographic, baseline, and ACP survey data from eligible participants. PLWH met with the research assistant independently in a private room. The research assistants administered the surveys orally and face-to-face in order to monitor emotional reactions, ensure understanding of the questions, control for vision impairment, and ensure data completeness. The research assistant recorded responses onto standardized paper forms. The trained research assistants also obtained medical data through chart abstraction, which were later scanned into the secure database REDCap and then verified through data checks.

Outcome Measure

The Lyon Family Centered ACP Survey-Patient Version-Revised17,18 assessed the values, beliefs, and life experiences with illness and end-of-life care of PLWH. The survey has 31 items across 4 domains: (1) ACP and Preparation; (2) Thoughts about Death and Dying; (3) Dealing with Dying; and, (4) Spiritual Well-Being. The ACP Survey was adapted with permission from the Association of Retired Persons (AARP)19 and Edinger & Smucker.20 The adapted survey was revised, validated, and piloted with adolescents living with HIV and bereaved families of children who had died of AIDS.17,18 Questions were clarified, reading difficulty was lowered to 6th grade level, and the number of items was reduced through meetings with community advisory boards. In the revised survey, the original Likert scale was modified slightly to improve psychometric properties, adding a neutral item and removing “no response,” yielding a 6-point Likert scale as follows: 1 = Very important, 2 = Somewhat important, 3 = Neither important nor unimportant, 4 = Not very important, 5 = Not at all important, 6 = Don’t know. The 10 responses to item 18 were selected to highlight in this paper because of the variance in responses. The query is: “How important would each of the following be to you if you were dealing with your own dying?” The sub-items are: Family and friends visiting me; staying in my own home; honest answers from my doctor; comfort from church services or persons such as a minister, priest, Iman, or rabbi; planning my own funeral; being able to complete an advance directive that would let loved ones know my wishes if I were unable to speak for myself; fulfilling personal goals/pleasures; reviewing my life history with my family; having health care professionals visit me at my home; and understanding my treatment choices.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample. Frequency distributions and percentages describe all item responses. Two-tailed Pearson chi-square and Fisher’s exact statistics were implemented using SAS 9·4 (Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.) to examine responses to survey items by demographic characteristics. However, because of the small sample size and large number of items, item response data are presented and discussed for exploratory purposes only and data are presented in the supplemental files.

Latent Class Analysis (LCA)21 identified unobserved latent classes/groups of PLWH with respect to goals and values about end-of-life care, as measured by item 18: “How important would each of the following be to you if you were dealing with your own dying?” Relationships between the socio-demographics (e.g., race, age, gender, sexual orientation, education level and income) and palliative care preferences were assessed, taking into account measurement errors in the latent class membership estimation.

We fit a series of LCA models with increasing number of latent classes and determined the optimal number of latent classes by comparing K-Class model with (K-1)-Class model iteratively. Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (aBIC), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Lo–Mendel–Rubin likelihood ratio (LMR LR), the adjusted LMR LR (ALMR LR) test, and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) were used for model comparisons. Once the number of latent classes was identified, individuals were classified into their most likely latent classes on the basis of their most likely latent class membership. The quality of latent class classification was assessed using entropy statistics and classification probabilities for the most likely latent class membership. Finally, the effects of demographic characteristics on the latent class membership were examined. To take into account measurement errors in the estimated latent class membership, the model estimation was implemented using the 3-step method22,23 in MPLUS 8·4 (Computer software, Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén). Significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Patients (N = 223) were 56% male, 86% Black or African American, aged 22–77 years (Mean = 51, SD = +/− 12). 20% were adults aged 22–39 years, 57% were adults aged 40–60 years, and 23% were over age 61, as reported in Table 1. Thirty-four percent were sexual minorities, defined here as self-reported non-heterosexual. Close to half had a high school education or less, 42%, and household income equal to or below the Federal poverty line, 40%. Two-thirds, 66%, had at least one co-morbidity, and 16% were receiving disability insurance. Participants had been living with HIV for an average of 17·5 years. All transgender persons (N = 4) and perinatally-infected PLWH (N = 6) who were approached agreed to participate and were eligible for participation. All enrolled participants completed the survey.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of People Living With HIV (n = 223).

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 50·8 (12·3) |

| Range | 22–77 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 125 (56·1) |

| Female | 94 (42·2) |

| Transgender | 4 (1·8) |

| Race | |

| African-American | 192 (86·1) |

| Non-African-American | 25 (11·2) |

| Declined | 6 (2·7) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 148 (66·4) |

| Non-Heterosexual | 75 (33·6) |

| Education | |

| High School or Lower | 93 (41·7) |

| Some College or Higher | 130 (58·3) |

| Income | |

| Equal, Below Federal | 86 (39·5) |

| Poverty Line | |

| Higher than Federal | 87 (39·9) |

| Poverty Line | |

| Declined to Report | 45 (20·64) |

| Time Since HIV Diagnosis (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 17–5 (8·2) |

| Advance Directive in Chart | |

| Yes | 29 (13·3) |

| No | 178 (81·7) |

| Don’t know | 11 (5·1) |

| Currently drug and/or alcohol dependent | |

| Yes | 9 (4·1) |

| No | 2l2 (95·9) |

| On Disability | |

| Yes | 36 (16·0) |

| No | 187 (84·0) |

| Comorbiditiesa | |

| Liver Disease including Hep B & Hep C | 63 (28·3) |

| Diabetes | 35 (l5·7) |

| Cancer or malignancies | 25 (11·2) |

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Heart disease or heart failure including heart attack or stroke | 25 (11·2) |

| Renal disease (kidney disease) | l8 (8·l) |

| HIV Associated Neurological Disorder (HAND) | 3 (l·3) |

More than one comorbidity could be chosen.

Latent Class Analysis of Goals and Values If Dying

Reponses to the item, “How important would each of the following be to you if you were dealing with your own dying?” were examined using latent class analysis to determine if there were subpopulations within the sample, or if there was homogeneity of responses. Model fit indices/statistics for model comparisons are shown in Table 2. The single-class model has the largest information criterion indices and the p-values of all the statistical tests in the 2-class model are <0·05, indicating that the single-class model was rejected and a model with at least 2 latent classes is in favor. In comparison between the 2-class model and the 3-class model, both models have similar AIC and aBIC, but the 2-class model has a smaller BIC. Importantly, all the LR tests (i.e., LMR LRT, LMRa-LRT, and BLRT) are all statistically insignificant for the 3-class model, indicating that the 2-class model can’t be rejected. Thus, we favor the 2-class model. The quality of class classification of the model is adequate with an entropy statistic of 0·73.

Table 2.

Latent Class Model Fit Comparison (N = 217)a.

| Model | AIC | BIC | aBIC | LMR-LRT P value | LMRa-LRT P value | BLRT P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Class | 1546·29 | 1580·09 | 1548·40 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| 2-Class | 1439·56 | 1510·54 | 1443·99 | 0·0000 | 0·0000 | 0·0000 |

| 3-Class | 1436·53 | 1544·69 | 1443·29 | 0·1139 | 0·1179 | 0·0800 |

6 participants who declined to give race were excluded.

··:Not applicable.

AIC: Akaike information criterion; BIC: Bayesian information criterion; aBIC: adjusted BIC; LMR-LRT: Lo-Mendell-Rubin-adjusted likelihood ratio test; LMRa- LRT: Lo-Mendell-Rubin-adjusted likelihood ratio test; BLRT: Bootstrapped likelihood ratio test.

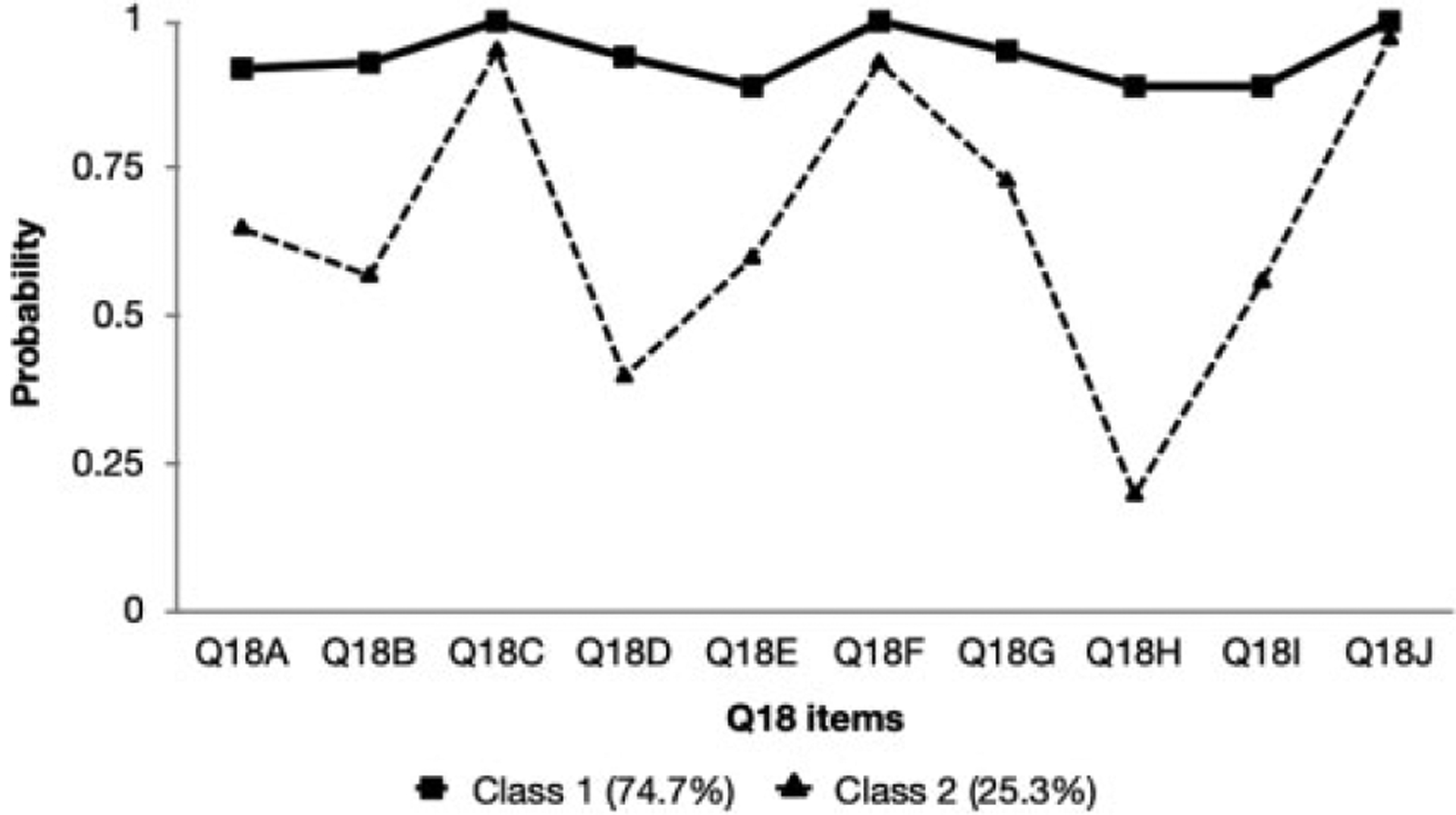

Selected results of the 2-class model are shown in Table 3. 74·7% (n = 162) of the sample were classified into Class 1 and 25·3% (n = 55) into Class 2. The classes are defined based on the conditional response probabilities (see Table 3 and Figure 1). Almost everyone in Class 1 endorsed importance of the following: family/friends visiting me; staying in my own home; comfort from church services or persons; planning my own funeral; reviewing my life history with my family; and having health care professionals visit me at my home. Thus, we labeled Class 1 as Relational: patients prioritized family, friends and comfort from church services, and comfort from healthcare personnel at EOL. We labeled Class 2 as Transactional/Self-Determination: as patients prioritized the importance of honest communication from their doctor, completing advance care plans, and understanding their treatment choices.

Table 3.

Selected Results of Latent Class Analysis for “How Important Would Each the Following Be to You If Dealing With Your Own Dying?” (N = 217)a.

| Items from question 18 | Class 1: Higher perception of importance–relational class (n = 162, 74·7%) | Class 2: Lower perception of importance–self-determination class (n = 55, 25·3%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family/friends visiting me | Not Important | 0·08 | 0·35 |

| Important | 0·92 | 0·65 | |

| Staying in my own home | Not Important | 0·07 | 0·43 |

| Important | 0·93 | 0·57 | |

| Honest answers from my doctor | Not Important | 0·00 | 0·05 |

| Important | 1·00 | 0·95 | |

| Comfort from church services or persons such as a minister, priest, imam, or rabbi | Not Important | 0·06 | 0·60 |

| Important | 0·94 | 0·40 | |

| Planning my own funeral | Not Important | 0·11 | 0·40 |

| Important | 0·89 | 0·60 | |

| Being able to complete an advance directive that would let loved ones know my wishes if I were unable to speak for myself | Not Important | 0·00 | 0·07 |

| Important | 1·00 | 0·93 | |

| Fulfilling personal goals/ pleasures | Not Important | 0·05 | 0·27 |

| Important | 0·95 | 0·73 | |

| Reviewing my life history with my family | Not Important | 0·11 | 0·80 |

| Important | 0·89 | 0·20 | |

| Having health care professionals visit me at my home | Not Important | 0·11 | 0·44 |

| Important | 0·89 | 0·56 | |

| Understanding my treatment choices | Not Important | 0·00 | 0·03 |

| Important | 1·00 | 0·97 |

Six participants who declined to give race were excluded.

Figure 1.

Profile for 2-class latent class analysis: probability of indorsing importance of Q18 items in response to: Q18: how important would each of the following be to you if you were dealing with your own dying?

Multinomial Logistic Regression

Selected results of the multinomial model are shown in Table 4. Patients who were African American were more likely to be classified in Class 1 [Odds Ratio (OR) = 3.30, 95% CI: 1·09 to 10·03], p = 0.035, meaning they were more likely to state family, friends and religious community as important. Males were less likely to be classified in Class 1 (OR = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.98), p = 0.045. 100% of transgendered persons (N = 4) were in Class 1. There were no significant associations by age or education with latent classes.

Table 4.

Selected Results of Latent Class Analysis for “How Important Would Each of the Following Be to You When Dealing With Your Own Dying?” (N = 217)a.

| Items | Class l: Relational (n = l62, 74·7%) | Class 2: Transactional/self-determination (n = 55, 25·3%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q18A | Not Important | 0·08 | 0·35 |

| Important1 | 0·92 | 0·65 | |

| Q18B | Not Important | 0·07 | 0·43 |

| Important1 | 0·93 | 0·57 | |

| Q18C | Not Important | 0·00 | 0·05 |

| Important1 | 1·00 | 0·95 | |

| Q18D | Not Important | 0·06 | 0·60 |

| Important1 | 0·94 | 0·40 | |

| Q18E | Not Important | 0·11 | 0·40 |

| Important1 | 0·89 | 0·60 | |

| Q18F | Not Important | 0·00 | 0·07 |

| Important1 | 1·00 | 0·93 | |

| Q18G | Not Important | 0·05 | 0·27 |

| Important1 | 0·95 | 0·73 | |

| Q18H | Not Important | 0·11 | 0·80 |

| Important1 | 0·89 | 0·20 | |

| Q18I | Not Important | 0·11 | 0·44 |

| Important1 | 0·89 | 0·56 | |

| Q18J | Not Important | 0·00 | 0·03 |

| Important1 | 1·00 | 0·97 |

6 participants who declined to give race were excluded.

Q18A: Family/friends visiting me.

Q18B: Staying in my own home.

Q18C: Honest answers from my doctor.

Q18D: Comfort from church services or persons such as a minister, priest, imam, or rabbi.

Q18E: Planning my own funeral.

Q18F: Being able to complete an advance directive that would let loved ones know my wishes if I were unable to speak for myself.

Q18G: Fulfilling personal goals/ pleasures.

Q18 H: Reviewing my life history with my family.

Q18I: Having health care professionals visit me at my home.

Q18 J: Understanding my treatment choices.

Patient-Reported End-of-Life Care Needs

We next present exploratory statistics on the significance of responses by gender, race and sexual orientation, because empirical data particularly on sexual minorities and end-of-life care goals, values, and beliefs are rare. We understand significance estimates are a limitation because of the large number of survey variables and small sample size. However, the data are valuable for exploring our understanding of minority populations and for generating future research with more robust samples. For this reason, we include all data from respondents by variables of interest in the supplementary files, as noted.

Hospice

Of the 223 participants, overall self-reported health ratings were excellent (28%), very good (30%), good (22%), fair (17%), and poor (2%). Only 8% had talked to their physician about their wishes for care at EOL, while 92% thought their doctor or hospital would respect their wishes for EOL care. 88% of PLWH reported they had heard of hospice. Of these, 67% knew of someone who had used hospice, 3% had used hospice services, and 3 had volunteered at a hospice. If dying, 53% reported they would want hospice support. See Supplemental Table 1 for frequencies/percentages of all surveyed responses.

Racial Differences

Six participants declined to report race and were excluded from the analysis of race. See Supplement Table 2 for descriptive statistics for all surveyed responses by race. Significant racial differences (Supplement Table 3) existed in the following EOL care needs. AA-PLWH’s preferred place of death, compared to non-African Americans, was more likely to be in a hospital, 19% vs. 4%, and less likely to be at home, 61% vs. 76%; (p = 0.0285). African-Americans were more likely to report they would only take pain medicines when the pain is severe (84% vs. 63%, p = 0.0113) and they would take the lowest amount of medicine possible to save larger doses for later when the pain is worse (70% vs. 41%, p = 0.0067). African Americans were also more likely to know someone who had used hospice services (72% vs. 50%, p = 0.0039). Although not a statistically significant difference, the majority of non-African Americans responded “living with great pain” was worse than death (17/25, 68%), compared to a minority of African Americans who responded “living with great pain” was worse than death (86/192, 45%).

Age Differences

Responses differed by age (Supplement Table 4). PLWH under age 40 were more afraid to die suddenly than middle aged or older adults (61% vs. 40% vs. 22%, p = 0.0007). Younger adults were also significantly more likely to value reviewing their life history if they were dying, compared to middle aged or older adults (82% vs. 71% vs. 52%, p = 0.0053).

Gender Differences

Females (Supplement Table 5) preferred the comfort of church services or religious clergy more often than males (88% vs. 71%, p = 0.0033). Females were more likely to want to plan their own funeral (88% vs. 72%, p = 0.0035). If dying, females were more likely to want to review their life history with their family (78% vs. 62%, p = 0.005).

Sexual Minority Differences

Self-identified sexual minorities (Supplement Table 6) were more likely to be afraid of dying alone than heterosexual PLWH (53% vs. 39%, p = 0.0397). Sexual minorities were less likely to see as important, if dying, comfort from church services or religious clergy (66% vs. 85%, p = 0.002), and were less likely to consider themselves religious or spiritual (84% vs. 94%, p = 0.0093) or to attend religious or spiritual services (57% vs. 78%, p = 0.017). Sexual minorities were less likely to take pain medicines only when the pain was severe (70% vs. 85%, p = 0.0091).

Education and Income Differences

PLWH with a high school education or less (Supplement Table 7) were more likely to only take pain medicines when the pain is severe (88% vs. 75%, p = 0.0238) and to be afraid of being given too much pain medicine (26% vs. 13%, p = 0.0202). PLWH whose income was below the federal poverty level (Supplement Table 8) were more likely to report a preference to be at home if dying (93% vs. 76% vs. 80%, p = 0.0117).

Discussion

Survey findings fill a gap in our understanding of the self-reported goals and values of PLWH with respect to end-of-life care. Three-fourths of the participants prioritized the relational aspects of dying, such as having family and friends visit, receiving comfort from church services, and comfort from persons at the end-of-life. One-fourth prioritized the transactional/self-determination aspects of dying, such as honest answers from their doctors and advance care plans, over relationships. When asked about dealing with their own dying, African American, female, and transgendered PLWH were more likely to prioritize the relational aspects of dying. In contrast, non-African Americans and male PLWH prioritized the transactional/self-determination aspects of dying, specifically, honest answers from their doctor, completion of advance directives, and the desire to know their treatment choices. These findings contribute specificity to previous research about the importance of family, relationships, and religiousness/spirituality with respect to end-of-life issues for ethnic and racial minorities.24–28 To our knowledge, this is the first study to include the views of transgendered persons (N = 4), all of whom were African American and in the relational latent class.

Our exploratory analysis of the item responses revealed that AA-PLWH were significantly more likely than non-African Americans to report that if dying they would only take pain medications when the pain was severe; and would take the lowest dose, saving larger doses for later. These results confirm the findings of 2 trials with African American adolescent PLWH17,18 and survey results among adult African American members of the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP).19 Study results are consistent with reports that prescription opioid use is lower among African Americans than white patients28–30 and provide evidence that this lower use of prescription opioids may be a result of patients’ preferences. Further supporting this, most AA-PLWH were willing to endure great pain and did not regard this as a fate worse than death. PLWH who had less education and those who were sexual minorities were also more likely to report only taking pain medication when the pain was severe. Given that pain is the most prevalent symptom among PLWH and there is a risk for under-treatment of pain,1 study results suggest opportunities exist to educate patients about pain medication in more meaningful ways. Particularly, clinicians should focus on the negative impact of delaying pain medications until pain is severe, potentially resulting in inadequate pain relief and need for rescue doses.

Survey results show that most PLWH receiving care in Washington, DC preferred to die at home, regardless of race: 61% for African Americans and 76% for non-African Americans. This preference differs from practice in the United States where in 2018 only 15% of PLWH died at home.24 The trajectory to death may be less predictable for PLWH, which may trigger hospital admissions for potentially life-extending interventions, increasing the likelihood of death in the hospital.24 Consistent with this, more than half of study participants had multiple morbidities and disability status. Hospital-based death may also reflect limited home resources, concerns about family-caregiver burden, or concerns about HIV disclosure.25,26,30 Results highlight the importance of not generalizing by race and the importance of individualized patient-centered care.

With respect to age across the lifespan, younger PLWH were more afraid of dying suddenly compared to older PLWH, consistent with previous research that younger patients have higher death anxiety and higher risk of sudden death from accidents or homicide.26,27,31 Females have been shown to have higher death anxiety as well, which is often dealt with by finding comfort in religion,31 confirming study findings.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to examine the goals and values of PLWH who identify as sexual minorities with respect to end-of-life care. Sexual minorities feared dying alone, consistent with the stigma and discrimination which places many at risk of social isolation.32 Non-heterosexuals were less likely to find the church as a source of comfort, which may reflect feelings of discrimination, due to homophobic messages.33 However, if the church community is affirming of sexual minority status, religion could serve as a protective factor. Study findings may be used to generate future research on interventions to decrease social isolation and increase palliative care services for non-heterosexual PLWH.

Access to hospice care may be limited for minorities.34 However, in cities like Washington, DC there are hospices devoted to providing services to patients with AIDS, such as Joseph’s House https://josephshouse.org which offers compassionate end-of-life care for homeless men and women with HIV. Findings indicate PLWH receiving care in Washington, DC are open to accessing hospice services and know someone who had used hospice services. Of those who had heard of hospice, 64% reported they would want hospice support, if dying. Among primarily AA-PLWH adolescents (N = 48) in the geographical south of the United States, 73% had heard of hospice but only 7% would want hospice support, if dying.17 Study findings are consistent with research indicating that greater exposure to hospice information was associated with more favorable beliefs about hospice care.35 Results also suggest a positive trend in knowledge about hospice among ethnic minority groups.36 Study participants trusted their clinicians and were willing to participate in a trial of family-centered advance care planning which found AA-PLWH were willing to limit treatment in some situations37 and agreed to document their advance care plans in their electronic health record.38

This study had limitations. The cross-sectional design does not allow for statements about causality. Findings may not generalize beyond PLWH receiving care in Washington, DC. Although the multisite design, high response rate, and completion of surveys in real-world hospital-based HIV clinics, increases the generalizability of findings to clinical practice. The sample size was too small to have meaningful statistical significance with respect to item responses. Data are presented to generate future research, given the paucity of research in this area with racial and sexual minorities. Participants may represent PLWH who trusted their hospitals and physicians (80% believing their doctor would very probably or most definitely respect their medical wishes), as well as more comfort discussing death and dying. Face-to-face survey administration may have created social desirability bias. However, non-response bias decreased as there were few missing data. Face-to-face survey administration also served as an effective engagement, safety monitoring, and data maximization strategy, while overcoming obstacles of low literacy, education, and vision impairment.

Conclusion

Two subpopulations were identified among PLWH: those who prioritized relationships if dying (females and African Americans) and those who prioritized self-determination over relationships (males and non-African Americans). A secondary analysis of item responses to the survey identified areas for future research to further explore differences in attitudes about pain management, place of death, and fear of dying alone. As HIV has become a chronic condition, understanding HIV positive persons’ attitudes, beliefs and values regarding end-of-life and palliative care may improve patient care and could be integrated into the HIV care continuum.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR)/National Institutes of Health (NIH) Award Number R01 NR014052-06 (no cost extension). This research has also been facilitated by the services and resources the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences-Children’s National (CTSI-CN) UL1RR031988. This research has also been facilitated by the services and resources provided by the District of Columbia Center for AIDS Research (DC-CFAR), an NIH funded program (AI117970), which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Aging, Fogarty International Center, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institute of Dia-betes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and Office of AIDS Research.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

Dr. Lyon developed and adapted the Lyon ACP Survey – Patient version used in this analysis. The survey is available for free upon request at mlyon@childrensnational.org. The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Harding R Palliative care as an essential component of the HIV care continuum. Lancet HIV. [Internet]. 2018;5(9):e524–e530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Kraemer H. Patient-reported barriers to high-quality, end-of-life care: a multiethnic, multilingual, mixed-methods study. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(4):373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erlandson KM, Allshouse AA, Duong S, MaWhinney S, Kohrt WM, Campbell TB. HIV, aging, and advance care planning: are we successfully planning for the future? J Palliat Med. 2012; 15(10):1124–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sancgarlangkam A, Merlin JS, Tucker RO, Kelley AS. Advance care planning and HIV infection in the era of antiretroviral therapy: a review. Top Antivir Med. 2016. 23(5):174–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wingood GM, Lambert D, Renfro T, Ali M, DiClemente RJ. A multilevel intervention with African American churches to enhance adoption of point-of-care HIV and diabetes testing, 2014–2018. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S2):S141–S144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dale SK, Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Klein DJ. Medical mistrust is related to lower longitudinal medication adherence among African-American males with HIV. J Health Psych. 2016;21(7):1311–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dale SK, Bogart LM, Galvan FH, et al. Discrimination and hate crimes in the context of neighborhood poverty and stressors among HIV-positive African-American men who have sex with men. J Community Health. 2016;41(3):574–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Tarima SS, DiFranceisco WJ, Amir-khanian YA. Correlates of sexual HIV risk among African American men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2016; 106(1):96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schouten J, Ferdinand WW, Stolte IG, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the prevalence of age-associated comorbidities and their risk factors between HIV-infected and uninfected individuals: the AGE IV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(12):1787–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman R, Gwadz MV, Silverman E, et al. Critical race theory as a tool for understanding poor engagement along the HIV care continuum among African American/Black and Hispanic persons living with HIV in the United States: a qualitative exploration. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):54. [Internet]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wegner NS, Kanouse DE, Collins RL, et al. End-of-life discussions and preferences among persons with HIV. JAMA. 2001; 285(22):2880–2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kremer H, Ironson G, Kaplan L, Stuetzele R, Baker N, Fletcher MA. Spiritual coping predicts CD4-cell preservation and undetectable viral load over four years. AIDS Care. 2015;27(1):71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giesbrecht M, Stajduhar KI, Mollison A, et al. Hospitals clinics, and palliative care units: Place-based experiences of formal healthcare settings by people experiencing structural vulnerability at the end-of-life. Health Place. 2018;53:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee M, Nezu AM, Nezu CM. Positive and negative religious coping, depressive symptoms, and quality of life in people with HIV. J Behav Med. 2014;37(5):921–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ironson G, Stuetzle R, Ironson D, et al. View of God as benevolent and forgiving or punishing and judgmental predicts HIV disease progression. J Behav Med. 2011;34(6):414–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimmel AL, Wang J, Scott RK, Briggs L, Lyon ME. FAmily CEntered (FACE) advance care planning: Study design and methods for a patient-centered communication and decision-making intervention for patients with HIV/AIDS and their surrogate decision-makers. Contemp Clin Trials 2015;43:172–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garvie PA, He J, Wang J, D’Angelo LJ, Lyon ME. An exploratory survey of end-of-life attitudes, beliefs and experiences of adolescents with HIV/AIDS and their families. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2012;44:373–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyon ME, Dallas RH, Garvie PA, et al. For the Adolescent Palliative Care Consortium. A pediatric advance care planning survey: Congruence and discordance between adolescents with HIV/AIDS and their families. BMJ Support Palliat Care. [Internet]. 2017;0:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcarej-2016-001224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummins R North Carolina End of Life Care Survey: African American Members. AARP; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edinger W, Smucker DR. Outpatients’ attitudes regarding advanced directives. J Fam Pract. 1992;35(6):650–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioural, and Health Sciences. Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muthen BO. Beyond SEM: general latent variable modeling. Behaviormetrika. 2002;29(1):81–117. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling. a 3-step approach using Mplus. Mplus web notes: No. 15; 2012. https://www.statmodel.com/examples/webnotes/AuxMixture_submitted_corrected_webnote.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harding R, Marchetti S, Onwuteaka-Philpsen BD, et al. Place of death for people with HIV: a population-level comparison of eleven countries across three continents using death certificate data. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Racial Carr D. and ethnic differences in advance care planning; identifying subgroup patterns and obstacles. J Aging Health. [Internet]. 2012;24(6):923–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong M, Yi EH, Johnson KJ, Adam ME. Facilitators and barriers for advance care planning among ethnic and racial minorities in the US: a systematic review of the current literature. J Immigr Minor Health. [Internet]. 2017;20(5):1277–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang CH, Crowther M, Allen RS, et al. A pilot feasibility intervention to increase advance care planning among African Americans in the deep south. J Palliat Med. [Internet]. 2016; 19(2):164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazanec PM, Daly BJ, Townsend A. Hospice utilization and end-of-life care decision making of African Americans. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27(8):560–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duffy SA, Jackson FC, Schim SM, Ronis DL, Fowler KE. Racial/ethnic preferences, sex preferences, and perceived discrimination related to end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006; 54(1):150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall J, Hutson SP, West F. Anticipating needs at end of life in narratives related by people living HIV/AIDS in Appalachia. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(7):985–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce JD Jr, Cohen AB, Chambers JA, Meade RM. Gender differences in death anxiety and religious orientation among US high school and college students. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2007;10(2): 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J, Chu Y, Salmon MA. Predicting perceived isolation among midlife and older LGBT adults: the role of welcoming aging service providers. Gerontologist. 2018;58(5):904–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J, Young S. The influence of pastors’ ideologies of homosexuality on HIV prevention in the black church. J Relig Health. 2016;55(5):1700–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haber D Minority access to hospice. Am J Hospice Palliat Care. 1999;16(1):386–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky J. Racial differences in self-reported exposure to information about hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(10):921–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LoPresti MA, Dement F, Gold HT. End-of-life care for people with cancer from ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;33(3):291–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyon ME, Squires L, Scott RK, et al. Effect of FAmily CEntered (FACE) advance care planning on longitudinal congruence in end-of-life treatment preferences: A Randomized Controlled Trial. AIDS and Behavior. [Internet]. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02909-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyon ME, Squires L, D’Angelo DJ, et al. FAmily CEntered (FACE) Advance care planning among African-American and non-African-American adults living with HIV in Washington, DC: A randomized controlled trial to increase documentation & health equity. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2019;57(3):607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.painsymman.2018.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.