Abstract

Objectives

The binaural interaction component (BIC) of the auditory brainstem response (ABR) is obtained by subtracting the sum of the monaural right and left ear ABRs from the binaurally evoked ABR. The result is a small but prominent negative peak (herein called “DN1”), indicating a smaller binaural than summed ABRs, that occurs around the latency of wave V or its roll-off slope. The BIC has been proposed to have diagnostic value as a biomarker of binaural processing abilities; however, there have been conflicting reports regarding the reliability of BIC measures in human subjects. The objectives of the current study were to: 1) examine prevalence of BIC across a large group of normal-hearing young adults, 2) determine effects of interaural time differences (ITDs) on BIC, and 3) examine any relationship between BIC and behavioral ITD discrimination acuity.

Design

Subjects were 40 normal-hearing adults (20 male, 20 female), aged 21 to 48, with no history of otologic or neurologic disorders. Midline ABRs were recorded from electrodes at high forehead (Fz) referenced to the nape of the neck (near the 7th cervical vertebra), with Fpz (low forehead) as the ground. ABRs were also recorded with a conventional earlobe reference for comparison to midline results. Stimuli were 90 dB peSPL biphasic clicks. For BIC measurements, stimuli were presented in a block as interleaved right monaural, left monaural, and binaural stimuli with 2000+ presentations per condition. Four measurements were averaged for a total of 8000+ stimuli per analyzed waveform. BIC was measured for ITD = 0 (simultaneous bilateral) and for ITDs of ± 500 μs and ± 750 μs. Subjects separately performed a lateralization task, using the same stimuli, to determine ITD discrimination thresholds.

Results

An identifiable BIC DN1 was obtained in 39 of 40 subjects at ITD = 0 μs in at least one of two measurement sessions, but was seen in lesser numbers of subjects in a single session or as ITD increased. BIC was most often seen when a subject was relaxed or sleeping, and less often when they fidgeted or reported neck tension, suggesting myogenic activity as a possible factor in disrupting BIC measurements. Mean BIC latencies systematically increased with increasing ITD, and mean BIC amplitudes tended to decrease. However, across subjects there was no significant relationship between the amplitude or latency of the BIC and behavioral ITD thresholds.

Conclusions

Consistent with previous studies, measurement of the BIC was time consuming and a BIC was sometimes difficult to obtain in awake normal-hearing subjects. The BIC will thus continue to be of limited clinical utility unless stimulus parameters and measurement techniques can be identified that produce a more robust response. Nonetheless, modulation of BIC characteristics by ITD supports the concept that the ABR BIC indexes aspects of binaural brainstem processing and thus may prove useful in selected research applications, e.g. in the examination of populations expected to have aberrant binaural signal processing ability.

INTRODUCTION

Binaural hearing, as opposed hearing via only one ear, provides well-known advantages when listening in complex environments such as noisy workplaces, classrooms, or restaurants, where there are competing sounds from multiple sources (Moore 2007). Differing arrival times and intensities of sound at each ear (interaural time differences [ITDs] and interaural level differences [ILDs] respectively), and differing spectral cues, are used by the normal auditory system to provide information on the locations of sound sources (Middlebrooks & Green 1991). Binaural hearing also provides for better speech understanding in background noise (for a review, see Bronkhorst 2000).

Many disorders can disrupt the ability to utilize binaural cues effectively. The most obvious disruption is loss of hearing sensitivity. In particular, presbycusis (age-related hearing loss) is known to result in poorer speech understanding ability in noisy environments (e.g. Frisina & Frisina 1997), possibly related to temporal processing deficits from loss of cochlear synapses (e.g. Pathasarathy & Kujawa 2018). Unfortunately, the use of hearing aids or cochlear implants does not completely overcome this problem (e.g. Moore 1996; van Hoesel 2004; Zheng et al. 2017), perhaps partly because hearing devices themselves add distortion to the properties of incoming signals (van den Bogaert et al. 2006; Wiggins and Seeber 2011; Brown et al. 2016). In addition, binaural (particularly ITD) sensitivity declines with age even after controlling for audibility (e.g., Grose and Mamo 2010; reviewed in Eddins et al. 2018)

Children can also be impacted by binaural dysfunction. For example, it has been suggested that chronic conductive hearing loss resulting from recurrent otitis media in childhood may manifest as impaired binaural and auditory spatial processing abilities even into adulthood, well after resolution of the peripheral hearing loss (e.g. Gunnarson & Finitzo 1991; Whitton & Polley 2011). Binaural signal processing deficits, which may underlie central auditory processing disorder (CAPD) in at least some patients, can also occur as a neurodevelopmental problem (Bellis & Bellis, 2015), as a sequela to traumatic brain injury (Gallun et al. 2017), or due to neurodegenerative conditions such as multiple sclerosis (Levine et al. 1993).

It is important to diagnose binaural processing difficulties in order to allow for appropriate intervention and rehabilitation strategies. Although a variety of behavioral diagnostic tests have been developed to evaluate central auditory processing abilities, they are not useful in populations that cannot give reliable behavioral responses, are prone to significant variability, and may reflect higher-level cognitive and analytical processes or language deficits rather than binaural processing per se (for a review, see Bellis & Bellis 2015). An objective, neurophysiological biomarker that would assist in diagnosis and evaluation of auditory system deficits in binaural processing could facilitate research on causes and interventions for CAPD, and significantly improve early identification and treatment.

One potential biomarker that has been proposed (see Laumen et al. 2016a for a review) is the binaural interaction component (BIC) of the auditory brainstem response (ABR). The ABR, a non-invasive auditory electrophysiological measure widely used clinically, is readily elicited by both monaural and binaural acoustic stimulation. The ABR BIC (hereafter referred to simply as BIC) is calculated as the residual waveform obtained after subtracting the sum of the monaurally-evoked (right ear and left ear) ABRs from the binaurally stimulated ABR. If there was no binaural processing in the pathway reflected by the ABR (i.e., simply two independent monaural pathways), the sum of the monaural ABRs should equal the binaurally-evoked ABR, resulting in a zero-difference waveform containing only measurement artifact and/or noise. In practice, however, a small but prominent negative1 component first appears at approximately the latency of ABR wave V peak or its roll-off slope. This deflection indicates a different amount of synchronous neural activity occurring in the brainstem during binaural stimulation than would be expected from the individual monaural stimulations alone, and has been given various names in the literature including “β” (e.g. Levine 1981; Furst et al. 1990; Brantberg et al. 1999a), “DV” (e.g. McPherson et al. 1989; Jiang 1996; Van Yper et al. 2015), and “DN1” (e.g. Dobie & Berlin, 1979; Riedel & Kollmeier, 2006; Junius et al. 2007; Ferber et al. 2016). In this article, the term “DN1” (indicating the first negative peak in the difference waveform) will be used synonymously with “BIC”.

The BIC has been measured in animal models (e.g. Dobie & Berlin, 1979, Wada & Starr, 1989; Laumen et al. 2016b; Benichoux et al. 2018). It has also been measured in humans in normal hearing adults (e.g. Ainslie & Boston 1980; Dobie & Wilson 1985; Wilson et al. 1985; Fowler & Leonards 1985; McPherson & Starr 1993; Jiang 1996; Stollman et al. 1996; Brantberg et al. 1999a,b; Van Yper et al. 2015) and in full-term neonates soon after birth (Hosford-Dunn et al. 1981; Furst et al. 2004). DN1 latencies are longer, and amplitudes are lower, in neonates relative to adults (Jiang & Tierney 1996).

There is growing evidence that the DN1 is generated at the level of the lateral superior olive (LSO) of the brainstem (see Laumen et al. 2016a for a review; Benichoux et al. 2018; Tolnai & Klump, 2019), an area associated with processing of both interaural level differences (Tollin, 2003; Tollin et al. 2008) and interaural time differences (Joris & Yin 1995; see also Joris & Trussell 2018). Examining the dependence of BIC on binaural interactions, a number of researchers have measured BIC while varying interaural difference cues (ITDs or ILDs), and have observed systematic changes in the amplitude and latency of BIC in both normal adults (Furst et al. 1985; McPherson & Starr, 1995; Brantberg et al. 1999a; Riedel & Kollmeier 2002, 2006) and in neonates (Furst et al. 2004). Specifically, these papers report that latency of DN1 systematically increases with increasing ITD and/or ILD (the cues that control perceptual lateralization). The amplitude of DN1 has been reported to systematically decrease with increasing ILD or ITD (e.g. Furst et al. 1985; McPherson & Starr 1995; Riedel & Kollmeier 2006), but the form of the function has differed across studies. For example, Furst et al (1985) reported no significant change in amplitude for ITDs ranging from 0 – 1 ms, but a sharp amplitude decrease at larger ITDs. In contrast, McPherson and Starr (1995) and Riedel and Kollmeier (2006) reported a more gradual decrease in amplitude as ITD increased within this range. In addition, BIC amplitude has been reported to correlate with the behavioral ability to lateralize sound as a function of both ITD and ILD (Furst et al. 1985, 1990; McPherson & Starr 1995), and its presence has been suggested to indicate binaural stimulus fusion (Furst et al. 1985; McPherson & Starr, 1995). Taken as a whole, the findings to date suggest that the BIC reflects binaural auditory processing at the level of the brainstem.

The BIC has been reported to be abnormal in the elderly (e.g. Van Yper et al. 2016), in persons with multiple sclerosis (Furst et al.1990), in specific language disorder (Clarke and Adams 2007), and in children diagnosed with CAPD (Gopal & Pierel, 1999; Delb et al. 2003) and autism spectrum disorder (El Moazen et al. 2020). In a different application, several researchers have proposed use of the BIC in matching bilateral electrode pairs in binaural cochlear implant users, using electrical ABR (EABR) measurements (Pellizone et al. 1990; Smith & Delgutte 2007; He et al. 2010, 2012; Hu & Dietz, 2015; Hu et al. 2016; see Brown et al. 2019).

Despite evidence that the BIC might have value as a non-invasive biomarker for binaural hearing, it has not been adopted in clinical diagnoses and evaluations. While studies in non-human species such as chinchillas and guinea pigs have reported robust and reliable BIC measurements (e.g. see Benichoux et al. 2018), human studies have produced more variable results, and some researchers have reported difficulty or even an inability to measure the BIC even with a large number of trials (e.g. Haywood et al. 2015; Brantberg et al. 1999a). Further, many human studies have reported results in a relatively small number of subjects.

If the BIC is to prove useful as a clinical neurodiagnostic indicator of binaural sound processing, it would need to be measurable in a high majority of subjects with normal binaural hearing. Thus, the first objective of the current study was to determine if the BIC can be reliably measured across a large group of normal hearing young adult subjects exhibiting normal binaural hearing using a broadband click stimuli, and to examine the range of response variability observed. The second objective of this study was to further evaluate the potential of the BIC to serve as a biomarker for binaural processing ability by evaluating: 1) the impact of ITD variation on BIC amplitude and latency, and 2) behavioral ITD discrimination using a parallel set of stimuli. The third objective was to compare the electrophysiological (BIC) results with behaviorally measured ITD discrimination thresholds obtained in the same subjects using the same stimulus. It was hypothesized that BIC amplitude would decrease, and latency increase, with increases in ITD. It was also hypothesized that BIC might be present more often across conditions in subjects with better performance on the ITD discrimination task, or that there might be a relationship between BIC parameters and ITD discrimination threshold.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Approval was obtained from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board for use of human subjects. Subjects were 40 normal hearing adults, 20 males and 20 females, aged 21 to 48 years (mean = 30; SD = 7). Normal hearing was defined as bilateral hearing thresholds ≤ 20 dB HL at audiometric frequencies from 250 Hz to 8000 Hz, with symmetrical hearing thresholds between the ears (≤ 10 dB difference at each frequency), normal Type A tympanograms in both ears, and normal results on the QuickSIN speech-in-noise test2 (Etymotic Research, Chicago, IL). The QuickSIN was included as a screening measure for auditory processing. None of the subjects had a history of otologic or neurological disorder. Subjects were paid for participation in the study.

Auditory Brainstem Response Recordings

Measurement system

Stimulus generation and ABR waveform acquisition were accomplished using a system comparable to that described in prior reports by our group (Beutelmann et al. 2015; Ferber et al. 2016; Benichoux et al. 2018). Stimuli were generated using MATLAB software (Natick, MA), routed through a Fireface UCX digital-to-analog convertor (RME, Haimhausen, Germany) and two Magna 3 headphone amplifiers (Schitt Audio, Newhall, CA), and presented via ER-2 insert earphones (Etymotic Research, Chicago, IL). The earphones were coupled to the subjects’ ears via disposable foam inserts that were carefully inserted to ensure the outer ends were evenly and symmetrically flush with the ear canal openings.

ABR waveforms were recorded from Ambu Neuroline 720 disposable surface electrodes (Ambu Inc., Columbia, MD), conditioned with a P511 AC amplifier (Grass instruments, Quincy, MA) with a built-in 60 Hz line filter and differential amplification for the evoked response, input to the Fireface for analog-to-digital conversion, and saved to a PC for recording and averaging using a custom MATLAB program. The Fireface used a 44.1 kHz sampling rate. A hospital-grade isolated power supply was used to minimize line noise, and an isolation transformer was placed in line for subject safety.

Stimulus blocks

Biphasic click stimuli (90 μs nominal duration) were presented at a level of 90 dB peSPL (corresponding to about 55 dB nHL, as measured across a subset of 15 of the normal hearing subjects). This level was selected after a pilot study indicated it was sufficient to produce a BIC, but not so loud that the subjects found it uncomfortable during a long test session. Stimulus level was calibrated via a 2 cc coupler attached to a Larson-Davis sound level meter and Tektronix oscilloscope for determination of peak equivalent SPL of the transient stimuli compared to a 1000 Hz calibration tone led through the system.

Monaural and binaural ABR conditions were interleaved within blocks of stimuli. Specifically, each ABR measurement used a block of 10,000 click presentations, consisting of a pseudorandomized order of 2000 monaural right ear clicks, 2000 monaural left ear clicks, 2000 binaural clicks presented simultaneously to each ear (ITD = 0), and 2000 binaural clicks presented at each of two selected non-zero ITDs (either ±500 μs or ±750 μs) per measurement. Responses were averaged separately by stimulation mode until at least 2000 repetitions were included for each listening condition (the number of stimuli presented typically exceeded 2000 per condition as a result of the artifact-reject filter excluding traces with electrical artifacts; furthermore, the number of accepted stimuli in individual conditions could exceed 2000 if the artifact reject filter did not exclude traces equally across listening conditions). Stimulus repetition rate was approximately 14 per second but “jittered” (specifically, the interstimulus interval was uniformly distributed between 9 ms and 19 ms in 1 sample increments).

ABR difference waveforms for each ITD condition were displayed in real time during measurements via digital subtraction of the summed monaural right and left ABRs from the binaural ABR (i.e., BIC = ABRBinaural − [ABRLeftMonaural + ABRRightMonaural]). To calculate the difference waveform for a non-zero ITD (the stimulus delayed to one ear), the corresponding monaural waveform was delayed by the same amount prior to summing of the monaural waveforms, as is standard procedure (e.g., Reidel & Kohlmeier 2006; Benichoux et al. 2018). For example, for ITD = +500 μs, the right monaural ABR was delayed 500 μs before addition to the left monaural waveform, and for ITD = −500 μs, the left monaural ABR was delayed 500 μs before addition to the right monaural waveform.

Measurement and recording parameters

After skin preparation, electrodes were placed according to the International 10–20 system (Jasper, 1958) at Fz (high forehead just under the hairline), referenced to the nape of the neck (just above the 7th cervical vertebra) with Fpz (low forehead) as the ground. Additionally, in the first recording session, standard ipsilateral monaural waveforms were also separately obtained for each ear by recording from Fz referenced to electrodes placed at each earlobe (A1 or A2) with Fpz as the ground. The ipsilateral waveforms were obtained for comparison to the monaural waveforms obtained with the midline (nape of neck) recordings. Electrode impedances were ≤ 5 kΩ (typically 3 to 4 kΩ) and balanced between electrode pairs within 1 kΩ.

During ABR measurements, subjects were seated comfortably with a neck pillow in a slightly reclining chair in a darkened sound booth and told to close their eyes and relax or sleep during measurements. The EEG was amplified by 50,000x and analog filtered 30 Hz to 3000 Hz by the Grass amplifier. Artifact rejection circuitry was set to ±20 μV. A recording delay was inserted by the MATLAB program to account for the acoustic delay caused by the tubing of the ER-2 insert earphones, with a recording epoch from −3 ms (providing a pre-stimulus baseline) to 18 ms post-stimulus.

ABR measurements were completed across two sessions done on different days, each typically 2 hours long, with rest breaks given during a session if needed (subjects who fell asleep were not awakened). On one of the days, ITDs measured were 0 (simultaneous binaural), −500 μs, and +500 μs, and on the other day, ITDs measured were 0, −750 μs, and +750 μs, with order of the days randomized across subjects. A total of four ABR measurement sets were completed on each measurement day (Each measurement set was comprised of an interleaved stimulus block as previously described, and averaged 2000+ stimulus presentations per listening condition: right monaural, left monaural, and binaural with two ITDs tested). The four ABR measurement sets were then combined for a total of 8000+ stimulus presentations per listening condition in the final (analyzed) waveforms. When an individual subject occasionally showed a much noisier set of ABR waveforms, with higher numbers of artifact-rejected sweeps, they were given a stretch break or their head position readjusted, and an additional ABR measurement set was completed. In these cases, the four ABR measurements with the most easily identifiable peak components and less visual noise in the trace were selected for further analysis.

Post-hoc waveform analysis

ABR recordings saved to MATLAB files were subjected to additional off-line, post-hoc analysis. First, waveforms were digitally filtered (3rd order Butterworth filter) from 100 to 3000 Hz. Second, a custom MATLAB program was used (by the first author, who has many years of experience measuring ABRs) to mark latencies and absolute (baseline to peak) amplitudes of all identifiable waves I through V of the monaural and binaural ABRs. Relative (peak to trough) amplitude was also determined for waves I, III, and V. Because DN1 could sometimes be small and thus difficult to differentiate above the noise floor, a conservative approach was taken to determine its presence or absence. Specifically, the temporal region of the difference waveform corresponding to wave V and its roll-off slope across the repeated ABR measurements was examined for comparison to the final summed waveform. If DN1 was not replicable across multiple runs or was not clearly above the noise floor of the trace in the summed waveform, it was judged to be absent. When present, the DN1 component of the BIC was also marked for latency, and for both absolute (i.e. peak) and relative (i.e. peak-to-peak; in this case, negative DN1 peak to the following positive peak) amplitude.

Finally, an objective cross-correlation based-analysis was applied using the individual BIC traces to compute BIC amplitude, latency, and a “signature” human BIC waveform. This procedure is described in detail in Benichoux et al. (2018) but will be briefly described here. The premise of this approach is based on the empirical observation in different species (from mouse to human) that the amplitude and the latency of the BIC waveform scales with increasing ITD but the general morphology or shape of the BIC waveform stays the same (Benichoux et al. 2018). First, the across subject grand means for stimuli with all ITDs (0, ±500 and ±750 μs) were computed. Next, these five grand mean waveforms, one for each ITD, were temporally aligned (based on the prominent DN1 component) and averaged. This across-subject and across-ITD grand mean BIC waveform defines a “signature” BIC waveform, truncated to capture the window from 2 ms to 10 ms after stimulus onset, approximately centered on DN1. Next, for each subject, individual BIC waveforms for each ITD were cross-correlated with the signature BIC. The maxima of these cross-correlations were scaled by the product of the RMS (Root-Mean-Squared) amplitudes of the two BIC waveforms, and then normalized to the scaled maxima of the 0-ITD autocorrelation function to derive a normalized scaling factor of each BIC function. Likewise, the time-shift of the maxima of each cross-correlation function was calculated to derive the delay (i.e. latency) of each BIC function relative to the 0-ITD condition. In summary, cross-correlating individual subject measurements with the signature BIC waveform provides a standardized and objective measure of the latency and amplitude of the BIC as a function of ITD. Because the predominant component of the BIC waveform is the DN1 component, this method effectively measures the relative latency and amplitude of DN1 with respect to the values corresponding to ITD = 0 μs.

Interaural Time Difference (ITD) Discrimination Behavioral Task

In separate sessions that lasted up to 1 hour, subjects performed a behavioral simple right/left lateralization task, using the same click stimuli used for the ABR measurements, to determine individual ITD discrimination thresholds. This task was implemented in a separate MATLAB program, and stimuli delivered via the same ER-2 insert earphones. This stimulus and task were expected to stimulate the brainstem circuitry responsible for producing the BIC (Furst et al. 1985, 1990; Riedel & Kollmeier 2002).

Prior to beginning the task, a “centering” procedure was done. For this procedure, a 1000 Hz test tone was presented binaurally at ITD = 0. Subjects were asked to verify that the tone was perceived as falling in the center of their head (midline). If the tone was not perceived at midline (which happened in very few cases), the placement of one or both ER-2 foam inserts was adjusted until a midline percept was reported. Behavioral testing was subsequently done without changing the position of the insert earphones.

During testing, subjects sat upright at a desk in the sound booth and responded using a large touch screen monitor. On the screen was a schematic illustration of a head, as shown in Figure 1A, with horizontal bars indicating the right and left sides of the head. Test stimuli consisted of sequential sets of clicks presented bilaterally. The first, diotic (reference) click was presented with ITD = 0, and the second, dichotic click was presented with a non-zero ITD so that there was perceived lateralization relative to the first click. ITDs were imposed, for left-favoring values, by fixing the stimulus in the left ear and delaying the stimulus in the right ear. For right-favoring values, the right ear stimulus was presented earlier than the left. The subject’s task was to indicate if the second stimulus was perceived as falling to the left or the right relative to the first. If the second stimulus was perceived as falling to the right of the first set, the subject was instructed to touch anywhere on the bar that was on the right side of the screen, and vice versa. Subjects received immediate feedback from the selection bar, which flashed green if their response was correct (based on the left- or right-favoring value of ITD; e.g. see Figure 1A) and flashed red if their response was incorrect.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the behavioral ITD discrimination task setup (A) and a typical set of results, from Subject ID #1828 (B). A: Subjects were presented with two click stimuli (a diotic reference click followed by a dichotic click with an ITD of varied magnitude) and instructed to select a bar on the screen according to the perceived lateral position (left or right) of the second stimulus relative to the first. The bar flashed green if the subject selected the correct side, and red if incorrect (a ‘correct’ response for a rightward ITD is illustrated here). B: Two threshold runs (shown in red and blue) were conducted simultaneously, with trials interleaved to determine the 79.4% correct ITD discrimination threshold. ITD just-noticeable-difference (JND) thresholds (horizontal lines) were calculated as the mean of the last 6 of the 10 reversals (filled triangles; see text for description).

Testing started with the ITD for the second binaural click stimulus at 800 μs, an easy condition for normal hearing subjects within the range expected for normal listening conditions in most individuals (Wightman & Kistler, 1989), and then the ITD changed adaptively depending on the subject’s response. A 3-down, 1-up psychometric procedure was used (Levitt, 1971), resulting in a 79.4% correct threshold; i.e., three consecutive correct responses were required for the ITD to decrease, but just one incorrect response resulted in an increase in the ITD. The initial step size was 300 μs, logarithmically adjusted over the course of the run (as cue magnitude decreased or increased, step size also decreased or increased). Two interleaved ITD threshold runs were performed so that no presentation pattern could be perceived by the subject. Testing continued until 10 reversals were observed (changes in direction of the ITD size). For each run, the first four reversals were discarded, and the last six reversals were averaged for the ITD just-noticeable-difference (JND) discrimination threshold estimation for that run. Illustrative results for a set of two interleaved threshold runs for one subject are shown in Figure 1B.

Three to six practice runs were first completed (more practice runs were used for subjects having difficulty performing the task reliably) to familiarize and train the subject on the task. Practice runs were discarded. Six ITD threshold estimates were then obtained (3 runs of 2 thresholds each). The highest and lowest of these 6 estimates were discarded and the average of the remaining 4 ITD threshold estimates was calculated to represent the subject’s final click ITD discrimination threshold.

RESULTS

Electrophysiological Measures

ABR Waveform Morphology

The midline electrode montage used in the BIC measurements resulted in increased distance from the midline (nape) electrode to the distal auditory nerve source, and thus wave I was expected to have a smaller amplitude than with the ipsilateral ABR montage typically used clinically for monaural stimulation. As expected, all 40 subjects showed a clear wave I in both ears with the earlobe reference montage, which was only measured once in the first session. With the midline montage, 39 of 40 subjects showed a wave I for monaural stimulation in at least one of the two measurement sessions. Across both sessions, 36 subjects showed a reliable wave I for the left ear and 37 subjects showed a reliable wave I for the right ear. In addition, there was slightly longer latency and a decrease in wave I amplitude with the midline montage relative to the ipsilateral. Table 1 provides mean and standard deviation (SD) wave I latency and absolute (baseline to peak) amplitude under each montage (for a subject with wave I in both measurement sessions, the average value was used in the calculations).

Table 1.

Means and SD of wave I latency (in ms), and absolute amplitude (in μV) for monaurally stimulated ABRs for ipsilateral and midline electrode montages. Also shown is the number of subjects showing an identifiable wave I for each ear and montage.

| Monaural Right Ear Stimulation | Monaural Left Ear Stimulation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Electrode Location: | Right Earlobe | Midline Nape | Left Earlobe | Midline Nape |

| Wave I Latency (ms) | ||||

| Mean | 1.39 | 1.70 | 1.64 | 1.73 |

| (SD) | (.12) | (.11) | (.11) | (.13) |

| Wave I Peak Amplitude (μV) | ||||

| Mean | .090 | .013 | .099 | .009 |

| (SD) | (.05) | (.03) | (.05) | (.04) |

| # of subjects | 40 | 39* | 40 | 39* |

For midline montage, monaural waveforms were measured twice, once in each session. If a subject had a wave I value at only one measurement session for a given ear stimulation, that value was used, but if a subject had a wave I at both measurement sessions, the average was used in calculating the mean.

Despite smaller wave I amplitudes (due to electrode montage), most subjects showed relatively well-defined ABR peaks for both monaural and binaural stimulation at ITD = 0 with the midline electrode montage. Individual subjects showed differences in waveform morphology as expected (e.g., due to differences in head size and orientation of the neural generators), but morphology was largely stable within a given subject across the two measurement sessions. Although some previous authors have reported multiple BIC components (e.g. Levine 1981; Jiang 1996; Van Yper et al. 2015), in this study only DN1 was seen prominently and reliably.

Table 2 provides mean and SD peak latencies for all identifiable waves I-V for the midline-measurement ABRs for monaural stimulation, and for binaural stimulation at each ITD, and indicates the number of subjects showing identifiable peaks. Note that the binaural listening condition of ITD = 0 was replicated across the two measurement sessions, so both values are shown for comparison. The same data are provided for absolute (baseline to peak) amplitudes of waves I-V in Table 3. As an additional comparison, relative (peak to following trough) amplitudes were also measured and are shown in Table 4. Mean peak values are in the general latency ranges that would be expected for the measurement parameters and montage used.

Table 2.

Means and SD of ABR peak latencies (in ms) and the number of subjects showing each identifiable peak. Part A: monaural and binaural stimulation for ITD = 0 μs (simultaneous) across both sessions. Part B: binaural waveforms for each of the non-zero ITDs.

| A | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Right Monaural | Left Monaural | Binaural | ||||||||||||||||||

| Wave | I | II | III | IV | V | I | II | III | IV | V | I | II | III | IV | V | |||||

| ITD = 0 μs (+/− 500 μs session) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean | 1.70 | 2.96 | 3.83 | 5.06 | 5.87 | 1.72 | 2.93 | 3.86 | 5.06 | 5.87 | 1.67 | 2.93 | 3.83 | 5.06 | 5.82 | |||||

| (SD) | (.12) | (.14) | (.15) | (.19) | (.21) | (.13) | (.16) | (.17) | (.21) | (.23) | (.11) | (.14) | (.16) | (.20) | (.23) | |||||

| # Subjects | 37 | 37 | 39 | 40 | 40 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 36 | 37 | 40 | 38 | 40 | |||||

| ITD = 0 μs (+/− 750 μs session) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean | 1.70 | 2.97 | 3.83 | 5.04 | 5.85 | 1.73 | 2.92 | 3.85 | 5.06 | 5.85 | 1.66 | 2.94 | 3.85 | 5.06 | 5.81 | |||||

| (SD) | (.13) | (.15) | (.14) | (.21) | (.22) | (.15) | (.17) | (.18) | (.20) | (.21) | (.16) | (.16) | (.16) | (.20) | (.22) | |||||

| # Subjects | 39 | 39 | 40 | 39 | 40 | 37 | 36 | 40 | 38 | 40 | 39 | 39 | 40 | 40 | 40 | |||||

| B. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Binaural ITD = −750 μs | Binaural ITD = −500 μs | Binaural ITD = +500 μs | Binaural ITD = +750 μs | |||||||||||||||||

| Wave | I | II | III | IV | V | I | II | III | IV | V | I | II | III | IV | V | I | II | III | IV | V |

| Mean | 1.74 | 2.83 | 3.81 | 4.89 | 5.85 | 1.74 | 2.99 | 3.90 | 5.10 | 5.82 | 1.74 | 2.92 | 3.88 | 5.13 | 5.82 | 1.70 | 2.73 | 3.83 | 4.77 | 5.82 |

| (SD) | (.11) | (.13) | (.18) | (.25) | (.20) | (.18) | (.28) | (.23) | (.25) | (.27) | (.20) | (.27) | (.24) | (.30) | (.23) | (.17) | (.21) | (.18) | (.19) | (.18) |

| # Subjects | 17 | 22 | 40 | 35 | 40 | 31 | 19 | 40 | 26 | 40 | 29 | 15 | 39 | 23 | 40 | 23 | 25 | 40 | 32 | 40 |

Table 3.

Means and SD of ABR absolute (baseline to peak) amplitudes (in μV) and the number of subjects showing each identifiable peak. Part A: monaural and binaural stimulation waveforms for ITD = 0 μs across both sessions. Part B: binaural waveforms for each of the non-zero ITDs.

| A. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Right Monaural | Left Monaural | Binaural | ||||||||||||||||||

| Wave | I | II | III | IV | V | I | II | III | IV | V | I | II | III | IV | V | |||||

| ITD = 0 μs (+/− 500 μs session) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean | .013 | .072 | .146 | .191 | .159 | .009 | .067 | .142 | .192 | .149 | .041 | .135 | .276 | .359 | .210 | |||||

| (SD) | (.04) | (.04) | (.06) | (.05) | (.07) | (.04) | (.05) | (.05) | (.07) | (.08) | (.06) | (.12) | (.12) | (.13) | (.14) | |||||

| # Subjects | 37 | 37 | 39 | 40 | 40 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 36 | 37 | 40 | 38 | 40 | |||||

| ITD = 0 μs (+/− 750 μs session) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mean | .013 | .069 | .159 | .192 | .136 | .008 | .065 | .146 | .189 | .160 | .040 | .107 | .282 | .357 | .222 | |||||

| (SD) | (.04) | (.05) | (.05) | (.05) | (.07) | (.04) | (.06) | (.06) | (.05) | (.06) | (.08) | (.10) | (.09) | (.09) | (.14) | |||||

| # Subjects | 39 | 39 | 40 | 39 | 40 | 37 | 36 | 40 | 38 | 40 | 39 | 39 | 40 | 40 | 40 | |||||

| B. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Binaural ITD = −750 μs | Binaural ITD = −500 μs | Binaural ITD = +500 μs | Binaural ITD = +750 μs | |||||||||||||||||

| Wave | I | II | III | IV | V | I | II | III | IV | V | I | II | III | IV | V | I | II | III | IV | V |

| Mean | .012 | .013 | .184 | .233 | .297 | .054 | .067 | .195 | .286 | .276 | .051 | .021 | .204 | .280 | .300 | .026 | .009 | .184 | .240 | .352 |

| (SD) | (.06) | (.05) | (.09) | (.08) | (.11) | (.07) | (.10) | (.07) | (.09) | (.12) | (.12) | (.08) | (.10) | (.08) | (.12) | (.06) | (.06) | (.10) | (.06) | (.09) |

| # Subjects | 17 | 22 | 40 | 35 | 40 | 31 | 19 | 40 | 26 | 40 | 29 | 15 | 39 | 23 | 40 | 23 | 25 | 40 | 32 | 40 |

Table 4.

Means and SD of ABR relative (peak to trough) amplitudes for waves I, III, and V (in μV) and the number of subjects showing each identifiable peak. Part A: monaural and binaural stimulation waveforms for ITD = 0 μs across both sessions. Part B: binaural waveforms for each of the non-zero ITDs.

| A. | ||||||||||||

| Right Monaural | Left Monaural | Binaural | ||||||||||

| Wave | I | III | V | I | III | V | I | III | V | |||

| ITD = 0 μs (+/− 500 μs session) | ||||||||||||

| Mean | .097 | .158 | .374 | .087 | .131 | .384 | .200 | .291 | .647 | |||

| (SD) | (.05) | (.05) | (.13) | (.04) | (.07) | (.12) | (.11) | (.15) | (.22) | |||

| # Subjects | 37 | 39 | 40 | 38 | 40 | 40 | 36 | 40 | 40 | |||

| ITD = 0 μs (+/− 750 μs session) | ||||||||||||

| Mean | .102 | .158 | .357 | .099 | .127 | .372 | .201 | .286 | .679 | |||

| (SD) | (.05) | (.07) | (.13) | (.06) | (.07) | (.13) | (.12) | (.12) | (.23) | |||

| # Subjects | 39 | 40 | 40 | 37 | 40 | 40 | 39 | 40 | 40 | |||

| B. | ||||||||||||

| Binaural ITD = −750 μs | Binaural ITD = −500 μs | Binaural ITD = +500 μs | Binaural ITD = +750 μs | |||||||||

| Wave | I | III | V | I | III | V | I | III | V | I | III | V |

| Mean | .131 | .130 | .474 | .153 | .133 | .620 | .176 | .122 | .671 | .124 | .109 | .497 |

| (SD) | (.06) | (.08) | (.16) | (.07) | (.09) | (.20) | (.16) | (.09) | (.22) | (.06) | (.10) | (.19) |

| # Subjects | 17 | 40 | 40 | 31 | 40 | 40 | 29 | 39 | 40 | 23 | 40 | 40 |

Of note in Table 3 is that the mean absolute (peak) wave V amplitude in the binaural waveforms increased with increasing ITD; that is, wave V amplitude for ITD = 0 (Table 3A, Binaural) is smaller than the wave V amplitudes for ITDs of ±500 and the amplitudes at ITDs ±500 μs are generally smaller than those measured for ITDs of ±750μs. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the lateral superior olive (LSO) is the key generator for the BIC (Benichoux et al. 2018; Brown et al. 2019) because maximum inhibition in LSO will be seen at ITDs near 0 because the excitatory input from one ear overlaps maximally with the inhibitory input from the other ear. This feature of binaural interaction at LSO produces the BIC, due to the fact that binaural ABR wave V amplitude will be reduced relative to the sum of the right and left monaural wave V. As ITD increases, however, there will be a decrease in inhibition because the excitation and inhibition do not completely overlap in time and thus the LSOs on both sides will be more active and wave V amplitude should increase until it approaches the sum of the monaural amplitudes at a large enough ITD.

BIC DN1 is Observed in Most Subjects

Illustrative examples of waveform sets are shown in Figure 2 for the ITD = 0 condition for two individual subjects. In these waveform sets, the top (blue) trace is the ABR for monaural left ear stimulation, and the second (red) trace is for monaural right ear stimulation. The third, solid black, trace is the ABR for binaural stimulation, which is overlaid with the dashed purple line representing the calculated sum of the monaural waveforms. The bottom trace of each set shows the calculated difference waveform (binaural ABR minus summed monaural), with the BIC DN1 appearing as a negative deflection occurring around the latency of wave V or its roll-off slope. Note that the voltage scale shown for the difference trace has been reduced from that for the ABR traces, so that the very small BIC can be more easily visualized. Figure 3 shows, for ITD = 0, a series of illustrative individual difference waveforms for 12 cases where a BIC DN1 was identified, compared to a series of individual difference waveforms for 8 cases where there was no clearly replicable or apparent DN1 above the noise floor for the particular measurement.

Figure 2.

Illustrative examples of waveform sets for two individual subjects (Subject ID #1831 and #1834) at ITD = 0 μs. The measured monaural left (blue), the monaural right (red), and the binaural (black) ABRs are shown for each subject. The dashed (purple) line superimposed over the binaural waveform is the calculated sum of the monaural waveforms, and the bottom (gray) trace is the calculated BIC difference waveform (binaural minus summed monaural). Note the voltage scale is different for the bottom trace to show the BIC DN1 as a small negative deflection occurring at approximately the latency of wave V or its roll-off slope. Waves I through V are indicated on each of the left, right, binaural, and summed monaural waveforms, and the DN1 wave is marked on the BIC waveform with vertical tick marks. Latency is defined as time relative to stimulus onset (in ms).

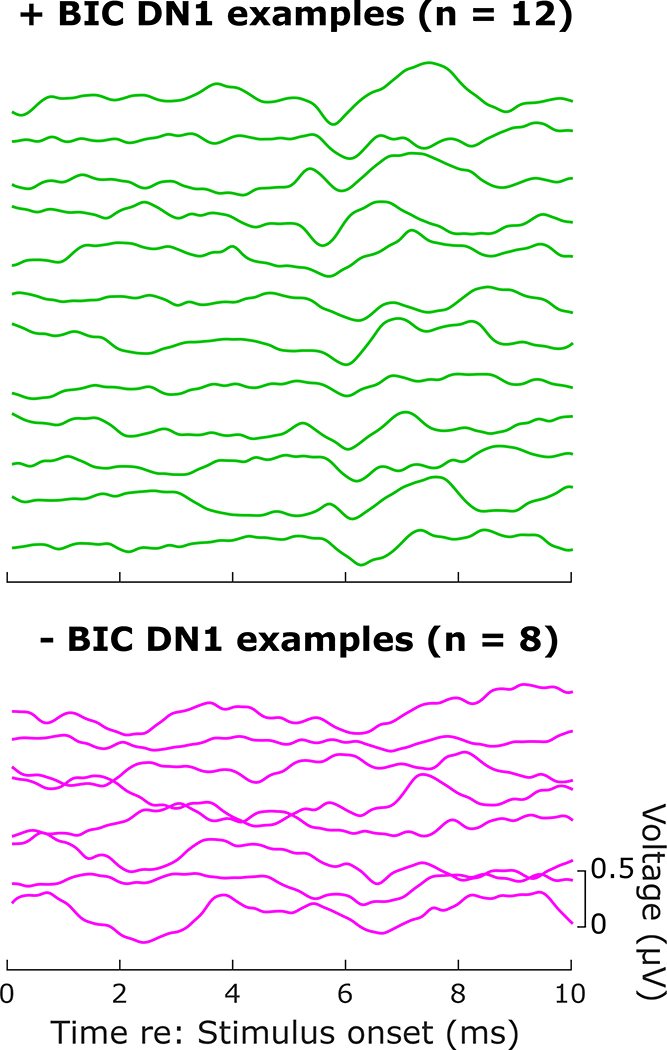

Figure 3.

A series of representative individual examples (each trace represents a different subject) of BIC difference waveforms at ITD = 0 μs where a BIC DN1 wave was visually identified (top; n = 12), and a series of BIC difference waveforms (at any ITD) where there was no BIC DN1 wave identified (bottom; n = 8). Note that some of the lower, no-DN1 traces may appear to show a negative deflection in the DN1 latency range; however, in those cases the deflection was either not replicable across repeated measurements within that condition (not shown) and/or was not clearly above the noise floor of the trace.

In 39 of the 40 subjects, a BIC DN1 was identified at ITD = 0 in at least one of the two ABR measurement sessions; however, not all subjects produced a clear BIC at ITD = 0 in both sessions. In the session in which measurements were made at 0 and ±500 μs ITDs, 83% (33/40) of the subjects produced a visually identifiable BIC at ITD = 0, and in the session in which measurement were made at 0 and ±750 μs ITDs, 73% (29/40) of subjects produced a BIC at ITD = 0. Only 46% of subjects produced an identifiable BIC at ITD = 0 across both sessions. The one subject who did not produce an identifiable BIC at ITD = 0 in either session did, however, produce an identifiable BIC at ITD = −500 μs and at −750 μs. In fact, in 6 subjects during the ITD = ±500 μs measurement session, and in 5 subjects during the ITD = ±750 μs measurement session, there was an identifiable BIC at a non-zero ITD, but no identifiable BIC at ITD = 0 in the same session. This latter finding is believed to be related to noisiness in some waveform measurements making identification of the BIC more difficult, as further discussed below.

At non-zero ITDs, binaural and monaural summed ABRs often had either poorer morphology (fewer identifiable peaks, such as showing only waves III and V), or a full complement of peaks but smaller amplitudes than seen at ITD = 0. Two illustrative individual examples of subject data sets showing these morphological differences are shown in Figure 4, which also illustrates BIC waveforms for ITD = 0 versus the BIC for a non-zero ITD. Note the longer latency BIC DN1 for non-zero ITDs relative to ITD = 0 in these examples.

Figure 4.

Illustrative individual examples of waveform sets for two subjects (Subject ID #1824 and #1831) showing morphological ABR differences and earlier latency for BIC DN1 for ITD = 0 μs (upper traces) versus non-zero ITDs (lower traces). Black trace: binaural ABR. Gray trace: calculated BIC difference waveform. Note the different voltage scale for the BIC traces to aid visibility of the small DN1. Waves I through V are indicated on the binaural waveforms (when present), and the DN1 wave is marked on the BIC waveforms with vertical tick marks.

Progressively fewer subjects showed an identifiable BIC as ITD was increased, with only 7 subjects showing a clear BIC across all ITD conditions including ITD = 0 at both sessions. Specifically, for ITDs of −500 or +500 μs, BIC DN1 was identified in 63% and 68% of subjects, respectively. For ITDs of −750 or +750 μs, BIC DN1 was identified in only 43% and 48% of subjects, respectively. Nevertheless, as shown in Figure 5, the grand mean (± SEM, standard error of the mean) waveform set across the ITDs for this normative subject group as a whole (n = 40) reveals an identifiable BIC for each condition and the expected increased latency with increased ITD (Laumen et al. 2016). Similarly, the mean binaural, monaural sum, and BIC ABR waveforms show decreases and delays that are symmetric across positive (solid) and negative (dashed) ITD values.

Figure 5.

Grand mean waveforms (± SEM, standard error of the mean) averaged across all trials, from all 40 normal hearing subjects, for monaural, binaural, and summed monaural conditions, and revealing an identifiable BIC DN1 at each ITD condition. BIC DN1 shows the expected increasing latency and decreasing magnitude with increasing ITD magnitude. Similarly, the binaural and summed monaural waveforms show amplitude decreases and delays that change systematically with increasing ITD magnitude, and are symmetric across positive (solid) and negative (dashed) ITD magnitude.

Table 5 shows mean and SD of latency and amplitude data for the BIC DN1 component, and the number of subjects showing an identifiable BIC at each ITD. Amplitude values are shown in two ways because both have been used in prior studies of the BIC: 1) relative BIC amplitudes (calculated as the difference between the negative DN1 peak and the subsequent positive peak amplitude), and 2) normalized absolute BIC amplitudes. These latter values were DN1 amplitude normalized to the mean RMS values of the two monaural waveforms to account for differences in overall amplitudes that may be due to non-BIC factors across sessions such as changes in electrode impedance or differences in myogenic activity (see Ferber et al. 2016 for details of this approach). Specifically, the normalization procedure was accomplished by dividing the BIC absolute amplitude for a given ITD condition by the average RMS amplitude values as calculated over the range 0 to 10 ms post-stimulus of the monaural ABR waveforms used to calculate that BIC within that recording session.

Table 5.

Mean and SD latencies (in ms), normalized absolute amplitudes* (in aU; arbitrary units following normalization), and relative amplitude† of the BIC DN1 (in μs), for each interaural time difference condition.

| ITDs: | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −750 μs | −500 μs | 0 μs (sess. 1) | 0 μs (sess. 2) | +500 μs | +750 μs | ||

| # Subjects with BIC | 16 | 25 | 32 | 29 | 27 | 20 | |

| Latency (ms) | Mean | 6.41 | 6.31 | 5.98 | 5.97 | 6.27 | 6.34 |

| (SD) | (.16) | (.22) | (.23) | (.26) | (.21) | (.23) | |

| Normalized absolute amplitude (aU) | Mean | −1.10 | −1.49 | −1.32 | −1.33 | −1.21 | −0.96 |

| (SD) | (.52) | (.59) | (.63) | (.55) | (.52) | (.59) | |

| Relative amplitude (μV) | Mean | .153 | .189 | .243 | .205 | .180 | .169 |

| (SD) | (.10) | (.09) | (.14) | (.07) | (.08) | (.07) | |

DN1 absolute amplitude (baseline to negative peak) was normalized to the RMS average of the monaural waveforms for the time period 0 to 10 ms.

Negative DN1 peak to the following positive peak.

A linear mixed-model analysis in SPSS v25 software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, IBM) was used on all available BIC data by gender and across ITDs. For ITD = 0, the singular or average value (as noted for Figure 6) was used for the statistical analysis. For BIC latency values, analysis revealed a statistically significant effect of gender (p = 0.003) and of ITD (p < 0.001), but no significant interaction. Examination by gender revealed a slightly longer latency mean BIC for male than for female subjects (mean difference = 0.113 ms). For ITDs, Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that ITD = 0 produced a significantly shorter latency than any of the four non-zero ITD conditions at p < 0.0001, and ITD = −750 μs produced significantly longer latency than either ITD = −500 μs (p = 0.05) or ITD = 500 μs (p = 0.03), but other comparisons did not reach the level of significance.

Figure 6.

Plots of BIC DN1 mean (± 1 SD; standard deviation) latency (A), normalized absolute amplitude (B; DN1 absolute [baseline-to-negative-peak]) amplitude was normalized to the RMS average of the monaural waveforms for the time period 0 to 10 ms), and relative amplitude (C; negative DN1 peak to following positive peak), at each ITD. Note that the normalization procedure results in arbitrary units (labelled aU in the figure). For subjects who had identifiable BIC DN1 responses at ITD = 0 μs in both measurement sessions, the average value was used.

For the normalized absolute BIC amplitude values, statistical analysis revealed no significant effect of either gender (p = 0.38) or ITD (p = 0.07), likely due to the relatively high variability in these data. For BIC relative amplitude values, statistical analysis revealed a significant effect of ITD (p = 0.04) but not of gender (p = 0.43), and no significant interaction (p = 0.24). Fisher’s LSD pairwise comparisons revealed that the means for both positive ITDs were significantly smaller than that at ITD = 0 (ITD = 500 μs, p = 0.02; ITD = 750 μs, p = 0.007), and the mean for ITD = −750 μs was also significantly smaller than for ITD = 0 (p = 0.02), but none of the other comparisons were significant at p < 0.05.

Figure 6 graphs the mean and SD of BIC DN1 latencies (part A), normalized absolute BIC amplitudes (part B), and relative BIC amplitudes (part C) for all available data at each ITD. For ITD = 0, if a subject had an identifiable BIC at only one measurement session, that was used, but when a subject had an identifiable BIC at both measurement sessions, the average of the two BIC values across the waveforms was used. A systematic increase in mean latency was observed with increasing ITDs. BIC normalized amplitude values were more variable but still tended to decrease (becoming more negative) with increasing ITD relative to ITD = 0, except at ITD = −500 μs. However, BIC relative (negative peak to following positive peak) amplitude values showed the expected systematic reduction in BIC size with increases in ITD.

Cross-Correlation Analysis

Because the DN1 of the BIC is very small in amplitude, making it prone to being obscured by noise, Benichoux et al. (2018) developed a cross-correlation analysis technique that captures information conveyed by the complete BIC waveform. This technique was applied to the current BIC data (see Methods), and the amplitude results are shown in Figure 7. Peak cross-correlation magnitudes for the 0 μs ITD conditions were averaged together across the two recording sessions for each subject; cross-correlation magnitudes for nonzero ITDs were normalized to this value. Individual data are shown as thin colored lines, and the median and interquartile range (25% - 75% of responses) are shown as heavy black lines and gray shaded areas, respectively, in Figure 7. The noise floor of this calculation was estimated, in the same manner as previously described (Benichoux et al. 2018), by calculating the cross-correlation of the pre-stimulus waveform with the 0 μs ITD BIC waveform, and the interquartile range of the resulting relative amplitudes are shown as a light gray shaded area in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Results of a cross-correlation (xcorr) based analysis following Benichoux et al. (2018; see text for details). Shown is normalized amplitude, relative to 0 μs ITD, that relates the amplitudes of the two waveforms. The 0 μs ITD conditions were averaged together across the two recording sessions for each subject. Individual relative xcorr amplitudes are shown as thin colored lines, and the median and interquartile range (25% - 75% of responses) are shown as heavy black lines and gray shaded areas. The noise floor of this calculation was estimated by calculating the cross-correlation of the pre-stimulus waveform with the 0 ITD BIC waveform, and the interquartile range of the resulting relative amplitudes are shown as a light gray shaded area.

A substantial reduction in relative amplitude is visible (Figure 7) with increasing ITD magnitudes (+ or -). Notably the cross-correlation takes into account additional features in the BIC waveform besides the prominent DN1 trough. Importantly, this procedure is objective and can be applied to identify changes in BIC morphology across arbitrary changes in stimulus or subject parameters. An implementation of this procedure could be useful to researchers and clinicians in the future.

Subjects Exhibited Normal Binaural Hearing Based on ITD Discrimination Task

In addition to BIC testing, subjects completed a behavioral ITD discrimination task (see Methods). Most subjects learned the task quickly and, after a few practice runs, reliably converged at an ITD discrimination threshold within the range expected for transients (Yost et al. 1971). Using the same broadband transient stimuli as that used to evoke the ABR BIC, the mean ITD discrimination threshold across subjects was 32 μs with a range from 18 μs to 85 μs (SD = 11, n = 40). However, it is notable that 85 μs was an outlier threshold from one subject who had substantial difficulty performing the task. If this outlier is removed from the analysis, the mean threshold was 30 μs with a range from 18 μs to 45 μs (SD = 7, n = 39).

The ITD discrimination task was intended to serve as an assay for the functioning of the binaural auditory brainstem similar to its usage by Furst et al. (1985,1990) and Riedel and Kollmeier (2002). As indicated above, all subjects (except for perhaps one) performed this task quite well and would be considered normal in terms of binaural hearing abilities with this particular transient stimulus. Because the binaural brainstem circuit that produces the BIC DN1 is also thought to contribute to the lateralization of transient stimuli (Furst et al. 1985, 1990; Riedel & Kollmeier 2002) we hypothesized that subjects performing the ITD discrimination task well would also be expected to produce a measurable BIC DN1. However, when comparison was made between ITD discrimination threshold and a measurable BIC for each subject, there was no clear correspondence. For example, Figure 8 plots individual ITD discrimination thresholds for the subjects divided into three groups: the 15 subjects in whom BIC was present in either all, or all but one, of the ITD conditions (ITD = 0 in both sessions, and all or all but one non-zero condition; the “+ BIC” group in Figure 8), the 12 subjects with BIC in only two or fewer ITD conditions across the two sessions (“- BIC” group in Figure 8), and the remaining 13 subjects whose number of identifiable BIC DN1s was in between the other groups (>2 but <5 BIC responses; the “Average BIC” group in Figure 8). Note that the one outlier subject value is indicated with an up arrow on this figure and was not included in statistical comparisons. While more subjects in the “+ BIC” group, with a clear BIC DN1 measured at most or all ITD conditions, tended to have somewhat lower behavioral ITD thresholds than the other two groups, they did not necessarily show the smallest (best) ITD discrimination thresholds, and the groups were not significantly different from one another when compared with Student’s t-tests (p > 05). Conversely, subjects in the “- BIC” group, with the fewest identifiable BIC responses, were not necessarily those with the largest (poorer) ITD discrimination thresholds. In fact, the subject with the outlier high threshold fell into the “+ BIC” group and the subject who did not show an identifiable DN1 at ITD=0 at either session (“- BIC group) had an ITD threshold near the mean (31 μs).

Figure 8.

Scatterplot of ITD discrimination thresholds with subjects divided into response groups (see text for details): “+ BIC” = 15* subjects with identifiable BICs across all, or all but one, ITD condition (green), “Average BIC” = 13 subjects with identifiable BIC across many but not all conditions (black), and “- BIC” = 12 subjects who had only 2 or fewer identifiable BIC responses across the sessions (magenta). *Note that the value for the subject with an outlier high threshold (marked with an arrow) was not included in statistical comparisons. Pairwise comparisons with a Student’s t-test did not reveal significant differences across the groups (p > 0.05 in all cases).

Individual BIC latencies at ITD = 0 μs (averaged across sessions for subjects with BIC at both sessions) were plotted against individual behavioral ITD discrimination thresholds (Figure 9). A linear regression determined no relationship between the two variables: Y = 3×10−4\x + 5.98 (R2 = 7×10−5).

Figure 9.

Scatterplot of ITD discrimination thresholds plotted against individual BIC latencies at ITD = 0 μs. For subjects with a BIC across both measurement sessions at ITD = 0 μs, the average latency value was used. Note that one outlier subject showed a substantially larger ITD threshold than is represented on these axes, and thus is shown on the edge of the panel with an arrow. A regression line is fit to the data and there is no relationship between the two measures.

Impact of Myogenic Interference on the BIC

Throughout data collection, it was noted that the BIC was most likely to be obtained and well-formed above the noise floor when a subject either fell asleep during the recording session or was very still and relaxed. These sessions were likewise correlated with clean and reliable monaural and binaural ABR morphology across measurements. In contrast, noisier ABR waveforms, with BIC either more poorly defined or absent, were more likely to be seen when the subject was fidgeting, having difficulty sitting still and relaxing, or if they reported neck, jaw, or shoulder tension. In these latter cases more click traces were rejected by the artifact-reject filter, and it subsequently took longer to complete a run. Although there were rare instances where a subject fell asleep and had minimal artifact-rejected click traces but an identifiable BIC was still not obtained in the measurement, myogenic interference appeared in most cases to be a primary contributor to trouble obtaining a clear and reliable BIC measurement in these normal human subjects.

In an effort to more objectively examine the impact of noise in the ABR waveform on the ability to obtain a clear BIC, waveform signal-to-noise ratio (SNR, in dB) was examined. Specifically, SNR was calculated on the waveforms as the difference between the RMS of the pre-stimulus interval (between −3 ms and +1 ms, which is prior to wave I) and the RMS of the ABR waveform (between 2 and 10 ms). This SNR was compared between two groups of the subjects (as previously defined for Figure 8). The first group (“+BIC” in Figure 10) consisted of the 15 subjects who had a measurable BIC at all or all but one ITD across the two measurement sessions. For these subjects, data from one measurement session in which all BICs were present was used3. The second group (“- BIC” in Figure 10) consisted of the 12 subjects who showed only 1 or 2 identifiable BICs across the two measurement sessions. For these latter subjects, data was used from one measurement session in which either no BIC or only a single non-zero BIC was obtained. As shown in Figure 10, left column, the waveform RMS noise in the ABR waveforms is not clearly related to whether or not a BIC was identified. Pairwise comparisons with a Mann-Whitney U test indicated that waveform RMS noise did not differ significantly between the “+BIC” and “-BIC” groups (p > 0.05). For the BIC waveforms, the comparison revealed p < 0.05 with slightly higher RMS noise for traces from the “- BIC” group compared to the “+ BIC” group; however, this was greater than the Bonferroni corrected criteria of α = 0.001. Figure 10, right column, uses the calculated BIC SNR for comparison to waveform noise in all recordings. The low R2 values (<0.1) for all four ABR waveforms indicate that less than 10% of the variability in SNR was explained by the variability in the noise. Likewise, the R2 of ~0.5 for the BIC waveform suggests that half the variability is due to the noise, and the other half of the variability is attributable to other sources.

Figure 10.

Left: RMS amplitude of the noise within each monaural, binaural, summed, or BIC waveform (for all ITDs) for a group of subjects showing an identifiable BIC DN1 in most or all measurements; green circles, labelled “+ BIC”) and a group of subjects showing few identifiable BICs across measurements; magenta asterisks; labelled “- BIC”). The median and interquartile range are shown as a horizontal blue line, and a blue box. The range of responses is represented with connected horizontal black lines, and outliers (excluded from the distribution) are represented with red + marks. Pairwise comparisons with a Mann-Whitney U test indicated that waveform RMS noise did not differ significantly between the two groups for the ABR waveforms, but differed significantly (p < 0.05) for the BIC waveforms. Right: RMS amplitude as a function of the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR; in dB) of the BIC waveforms. Noise is estimated as the RMS amplitude of the recording from −3 ms to +1 ms, which precedes wave 1 in all conditions. Signal amplitude is estimated as the RMS amplitude in the BIC waveform between +2 ms and +10 ms, which captures the entire ABR waveform in all conditions. Colored dots connected with thin lines indicate responses collected within a single recording session, thick black lines represent a linear regression to all responses. Correlations between ABR SNRs and BIC noise were R2 < 0.1, and between BIC SNR and BIC noise was R2 ~0.5.

DISCUSSION

The BIC DN1 was measured in 98% of the normal hearing human subjects in this study in at least one of two measurement sessions at ITD = 0 μs, although smaller percentages showed a BIC at a given measurement session or as ITD increased. This is comparable to the majority of reports in the literature, which have reported >90% to 100% of normal adult subjects showing a BIC at ITD = 0 μs (e.g. Levine 1981; Fowler & Leonards 1985; Jones & van der Poel 1990; Brantberg et al. 1999a). In contrast, Haywood et al. (2015) reported that it was not clear that an ABR BIC could be identified above the noise floor for “a majority of subjects”. It is of note, however, that BIC amplitudes were smaller in the Haywood et al. study (approximately 0.1 μV ) compared to other reports (see below), due to the measurement techniques used; Specifically, Haywood essentially used a monaural electrode montage to measure BIC so that measurement was at a greater distance from the brainstem source. Also consistent with our findings, Brantberg et al. (1999a) reported obtaining lesser numbers of identifiable BICs across subjects as ITD increased.

Latency and amplitude values in the current study were similar to previous reports in the human BIC literature, although differences in stimuli, measurement parameters, and analysis approach make direct comparisons difficult. For ITD = 0 μs, the mean absolute DN1 amplitude in this study was approximately –0.2 μV, which is within (albeit at the lower end of) the range 0.2 to 0.6 μV absolute amplitudes reported by other researchers using similar measurements (e.g. Dobie & Norton 1980; Furst et al. 1985; Jones & van der Poel 1990; Brantberg et al. 1999a). Likewise, the mean DN1 latency of approximately 6.0 ms at 0 μs ITD in the current study is in the range reported for humans of 5.6 to 6.9 ms (e.g. McPherson & Starr, 1985; Furst et al. 1990; Jones & van der Poel 1990; Brantberg et al. 1999a). Amplitudes from the human studies are smaller and latencies longer than those seen in animal models, likely due to larger human head sizes resulting in greater distance to the neural generators and the presumed neural generator size in humans relative to smaller mammals (Laumen et al. 2016a; Benichoux et al. 2018).

The BIC appeared to be highly susceptible to degradation by myogenic artifact, which is believed in most cases to have been a primary reason for an absent BIC in this normal hearing population. Jiang and Tierney (1996) reported it was typically more difficult to obtain BICs in neonates than in adults, which they noted was likely due to myogenic contamination because muscle artifacts are more common in babies. However, it is notable that noise estimates from ABR waveforms in the current study revealed only weak, albeit still significant, correlations to the presence of BIC responses, suggesting waveform noise variability only accounts for a portion of the BIC measurement variability observed.

Unfortunately, measurement of the BIC is time consuming. In this study, each BIC interleaved-stimulus block measurement, with a minimum of 2000 click repetitions per listening condition and 3 ITD values, took about 12 to 14 minutes to complete, depending on the number of rejected traces due to electrical artifact. Further, many subjects needed stretch breaks after every 2 or 3 runs. Typically, four measurements needed to be averaged (8000 click repetitions minimum in this paper) before the BIC was clearly identifiable and determined to be replicable. For several subjects who had not shown a BIC response after 8000+ click repetitions were averaged, an additional 2000+ click repetitions were tried for inclusion in the average, but this still did not result in a measurable BIC in those cases. Further, a higher repetition rate of approximately 33/second was tried in pilot study in an attempt to speed up the measurements, but this appeared to make the BIC even harder to obtain. Jiang (1996) and Brantberg et al. (1999b) also reported that the BIC was harder to obtain as stimulus repetition rate increased (see also Laumen et al. 2016a for review of how stimulus parameters affect BIC).

When present, BIC latency significantly increased and amplitude generally decreased with increasing ITD, a finding consistent with previous research (e.g. Furst et al. 1985; McPherson & Starr 1995; Brantberg et al 1999a; Reidel & Kohlmeier, 2006). The latency changes across ITDs appeared to be relatively systematic in the current study, while variability was higher in amplitude measures, as also reported previously in the literature. In the current study, BIC relative (negative peak to following positive peak) amplitude was more reliable than BIC absolute (negative peak) amplitude in showing the predicted reduction with increasing ITD. The current relative BIC amplitude findings are consistent with the reports of McPherson and Start (1995) and Reidel and Kollmeier (2006), who showed systematic decreases in amplitude with ITDs < 1 ms.

In this study, however, only limited correspondence was found between the electrophysiologic BIC measures and the behavioral ITD discrimination threshold results. This is in contrast to some other researchers who have reported a correlation between the BIC and behavioral lateralization as a function of ITD and ILD (Furst et al. 1985, 1990; McPherson & Starr 1995), although it appears that those studies only utilized subjects in which they were able to measure a BIC. Further, we did not measure lateralization per se in our experiment, so it is difficult to compare our results to these other studies.

There are a number of possible reasons for the lack of a clear relationship between the behavioral and electrophysiological measures in the current study. First, it is highly likely that the two measures simply did not index the same aspects of binaural processing. Neurons from the lateral superior olive of the brainstem are believed to be the primary source of the BIC (Benichoux et al., 2018; Tolnai & Klump 2019), and these neurons are known to be sensitive to ITDs of transient stimuli, such as clicks (Joris & Yin 1995; Irvine et al. 2001; Beiderbeck et al 2018). However, while ABRs to broadband click stimuli are known to be dominated by response from the higher, 2000–4000 Hz, region in normal hearing subjects (e.g. Eggermont & Don 1980), perceptual acuity for ITDs for broadband transients are thought to be more dependent on low frequencies <1000 Hz (Tollin & Henning 1999). Thus, it is possible that high-pass or low-pass filtering of the click stimuli might have changed the findings. Second, some subjects found the particular behavioral task chosen to be quite difficult to do even after multiple practice runs, thus introducing increased variability into the behavioral results. In this study, only a single click was presented to each ear binaurally at ITD = 0 μs and then at the comparison ITD, and subsequent pilot study suggests the task would have been easier for subjects and produced more reliable results had we instead given a short series of binaural click stimuli. Third, the BIC measurements may simply have been too variable to reflect fine differences in the ITD discrimination thresholds. In addition, the range of ITDs tested for the BIC was much larger than the range of ITD discrimination thresholds found in these normal hearing subjects. Finally, an alternative explanation for the lack of correspondence between performance on the ITD discrimination task and the presence of a reliably evoked BIC may simply boil down to noise resulting in missing BIC data. The BIC of course is derived from sums and differences of already noisy ABRs. Therefore, a relatively small amount of noise, perhaps due to myogenic potential, may accumulate rapidly when computing the BIC and thus render the BIC undetectable.

Unless approaches to optimizing ABR BIC measurement are developed and its diagnostic value (i.e., what physiological/behavioral capacities it predicts) is better specified, the BIC will continue to be of little clinical value. Other auditory evoked potentials (AEPs) have also been evaluated as potential biomarkers of binaural processing, including the frequency following response (e.g. Du et al. 2011; Clinard et al. 2017), middle latency response (e.g. Jones & van der Pool 1980; Debruyne 1984; McPherson & Starr, 1993; Fowler & Horn 2012) cortical/late response (e.g. Debruyne 1984; McPherson & Starr 1993; Epp et al. 2013) and interaural phase modulation-following response (e.g. Haywood et al. 2015), among others. It is possible that a different or higher-level AEP may be easier or faster to obtain, although it remains unclear whether these responses reflect the same binaural processing occurring at lower levels of the auditory system.

Although the results of this study do not support the current application of the acoustically-evoked ABR BIC as a clinical tool, there remains substantial interest in applying the electrically-evoked ABR BIC to the fitting of bilateral cochlear implants (e.g. He et al. 2012; Hu & Dietz 2015; Hu et al. 2016; see Brown et al. 2019). Further, the BIC may provide useful information as a research tool when applied to non-normal populations that are expected to have aberrant brainstem-level binaural processing abilities (e.g., multiple sclerosis; Furst et al. 1990). At the very least, and even with current methodology employed in this study and prior studies, the ABR BIC may still be a useful and informative research tool for non-invasive assessment of binaural brainstem function in humans and a variety of mammalian model species, e.g., using the cross-correlation analysis based on the signature BIC waveform (Figure 7; see Benichoux et al. 2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH National Institute for Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R01-DC011555 (to D. J. Tollin). Portions of this article were presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology (ARO), Baltimore, Maryland, February 2018.

Supported by NIH R01-DC011555

Financial disclosures/conflict of interest: This research was supported by a grant (to D.J.T.) from the National Institute of Health (NIH R01-DC011555). There are no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Footnotes

In some studies the binaural waveform was subtracted from the monaural sum so that the BIC appeared as a positive rather than negative peak (e.g. Levine 1981; Brantberg et al. 1999a; Furst et al. 2004; Van Yper et al. 2015).

37 of 40 subjects scored <1.5 dB SNR on the QuickSIN. The three subjects who scored 2.0 or 2.5 dB SNR were non-native English speakers, which may have partly impacted the results, but these results were still considered reasonably within the normal range.

For subjects with BIC at all 3 ITDs in both sessions, data from the measurement session for ±500 μs ITD was used.

References

- Ainslie P, Boston J (1980). Comparison of brainstem auditory evoked potentials for monaural and binaural stimuli. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 49, 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellis T, Bellis J (2015). Central auditory processing disorders in children and adults. Handbook Clin Neurol, 129, 537–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benichoux V, Ferber A, Hunt S, et al. (2018). Across species “natural ablation” reveals the brainstem source of a noninvasive biomarker of binaural hearing. J Neurosci, 38(40), 8563–8573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiderbeck B, Myoga M, Muller N, et al. (2018). Precisely timed inhibition facilitates action potential firing for spatial coding in the auditory brainstem. Nat Commun, 9(1), 1771. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04210-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutelmann R, Laumen G, Tollin DJ, Klump GM (2015). Amplitude and phase equalization of stimuli for click evoked auditory brainstem responses. J Acoust Soc Am, 137, 71–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantberg K, Hansson H, Fransson P-A., et al. (1999a). The binaural interaction component in human ABR is stable within the 0- to 1-ms range of interaural time differences. Audiol Neurootol, 4, 88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantberg K, Fransson P-A, Hansson H, et al. (1999b). Measures of the binaural interaction component in human auditory brainstem response using objective detection criteria. Scand Audiol, 28, 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronkhorst A (2000). The cocktail party phenomenon: A review of research on speech intelligibility in multiple-talker conditions. Acustica, 86, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Rodriguez F, Portnuff C, et al. (2016). Time-varying distortions of binaural information by bilateral hearing aids: Effects of nonlinear frequency compression. Trends in Hearing, 20, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Anbuhl K, Gilmer J, Tollin D (2019). Between-ear sound frequency disparity modulates a brain stem biomarker of binaural hearing. J Neurophysiol, 22(3), 1110–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke E, Adams C (2007). Binaural interaction in specific language impairment: an auditory evoked potential study. Dev Med Child Neurol, 4(4), 274–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinard C, Clinard S, Scherer M (2017). Neural correlates of the binaural masking level difference in human frequency-following responses. JARO, 18, 355–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debruyne F (1984). Binaural interaction in early, middle, and late auditory evoked responses. Scand Audiol, 13, 293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delb W, Strauss D, Hohenberg G, et al. (2003). The binaural interaction component (BIC) in children with central auditory processing disorders. Int J Audiol, 42(7), 401–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobie R, Berlin C (1979). Binaural interaction in brainstem-evoked responses. Arch Otolaryngol, 105(7), 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobie R, Norton S (1980). Binaural interaction in human auditory evoked potentials. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 49, 303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobie R, Wilson M (1985). Binaural interaction in auditory brain-stem responses: Effects of masking. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 62(1), 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Kong L, Wang Q, et al. (2011). Auditory frequency-following response: A neurophysiological measure for studying the “cocktail-party problem”. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 35, 2046–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddins A, Ozmeral E, Eddins D (2018). How aging impacts the encoding of binaural cues and the perception of auditory space. Hear Res, 369, 79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Moazen D, Sobhy O, Abdou R, Ismail H (2020). Binaural interaction component of the auditory brainstem response in children with autism spectrum disorder, Int J Pediatric Otorhinolaryngol, doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.109850 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont J, Don M (1980). Analysis of the click-evoked brainstem potentials in humans using high-pass noise masking. II. Effect of click intensity. J Acoust Soc Am, 68(6), 1671–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp B, Yasin I, Verhey J (2013). Objective measures of binaural masking level differences and comodulation masking release based on late auditory evoked potentials. Hear Res, 306, 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber A, Benichoux V, Tollin D (2016). Test-retest reliability of the binaural interaction component of the auditory brainstem response. Ear Hear, 27(5), e291–e301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler C, Leonards J (1985). Frequency dependence of the binaural interaction component of the auditory brainstem response. Audiology, 24, 420–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler C, Horn J (2012). Frequency dependence of binaural interaction in the auditory brainstem and middle latency responses. Am J Audiol, 190(21), 190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina D, Frisina R (1997). Speech recognition in noise and presbycusis: Relations to possible neural mechanisms. Hear Res, 106, 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst M, Levine R, McGaffigan P (1985). Click lateralization is related to the component of the dichotic brainstem auditory evoked potentials of human subjects. J Acoust Soc Am, 78(5), 1644–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst M, Eyal S, Korcyzn A (1990). Prediction of binaural click lateralization by brainstem auditory evoked potentials. Hear Res, 49, 347–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst M, Bresloff I, Levine R, et al. (2004). Interaural time coincidence detectors are present at birth: evidence from binaural interaction. Hear Res, 187, 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallun F, Papesh M, Lewis M (2017). Hearing complaints among veterans following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj, 31(9), 1183–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose JH, Mamo SK (2010). Processing of temporal fine structure as a function of age. Ear Hear, 31(6), 755–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]