Abstract

To better understand the processing of e-cigarette prevention messages, we conducted a content analysis of 1,968 participants’ open-ended responses to one of four messages, which focused on industry manipulation (Big tobacco), financial and psychological cost of vaping (Can’t afford), harmful chemicals in e-cigarettes (Formaldehyde), or uncertainty about the ingredients of e-liquids (Top secret). Health Belief Model (HBM) and perceived message effectiveness (PME) constructs were coded and the frequency of each variable was compared across message conditions. Among the HBM constructs, perceived health threat had the most mentions overall (38.8%). Self-efficacy of staying away from vaping had the fewest mentions across all messages (0.56%). For PME, participants more frequently mentioned message perceptions (15.75% positive message perceptions, 8.38% negative) than effect perceptions (3.46% positive effect perceptions, 1.37% negative). Big tobacco received the highest number of mentions for positive message perceptions and Formaldehyde received the highest number of mentions for positive effect perceptions. Future anti-vaping messages are recommended to address the efficacy element and to combine different themes to communicate harms of e-cigarettes.

Keywords: content analysis, e-cigarette risk messages, health belief model, perceived message effectiveness

Rates of electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use in the United States have rapidly increased in recent years. In 2016, 15.3% of adults had ever used e-cigarettes (Bao et al., 2018) compared to 1.8% in 2010 (McMillen et al., 2014). The proportion of adult never smokers who used e-cigarettes increased from 0.3% in 2010 to 5.7% in 2016 (Bao et al., 2018). Use of e-cigarettes has risen particularly fast among high school youth, jumping from 1.5% in 2010 to 27.5% in 2018 (Cullen et al., 2019). This rise is driven in part by the recent popularity of USB flash drive-shaped e-cigarettes, such as JUUL (King et al., 2018). These products are easy to conceal, have high nicotine content, and come in various flavors that appeal to youth (King et al., 2018). Moreover, e-cigarettes have been widely marketed as a healthier and cleaner alternative to combusted cigarettes, and a tool for smoking cessation, making the devices more socially acceptable among both smokers and non-smokers (Paek et al. 2014; Willis et al., 2017).

Although e-cigarettes may contain lower levels of toxic substances than combusted cigarettes (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018), they still pose high risk of heart and respiratory diseases (Alzahrani et al., 2018; Osei et al., 2019). As of February 18, 2020, 2,807 hospitalized cases of EVALI (e-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury) and 68 deaths have been reported (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020). These cases have been linked to the use of vitamin E acetate in THC used in e-cigarettes (Blount et al., 2019). In addition, most e-cigarettes contain nicotine, which is highly addictive and can cause long-term damage to teens’ brain development. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults is also strongly related to the use of other tobacco products (Khouja et al., 2020). Thus, communicating the risks of e-cigarettes to the public is important.

Emerging research has examined e-cigarette risk messages and found that these messages are a feasible tool to educate people about the harms of e-cigarette use (Cavallo et al., 2019; Walter et al., 2019). However, existing studies have primarily relied on close-ended questions to measure people’s responses to e-cigarette messages. We know little about, when participants have the freedom to write down whatever comes to their mind, to what extent they would think about theoretical constructs that are instrumental to attitude and behavior change. Examining responses to open-ended questions can help us explore these questions and can also complement close-ended measures of variables (Reynolds-Tylus et al., 2020). Yet, only a few studies to date (Owusu et al., 2020; Roditis et al., 2020) have used open-ended questions or qualitative methods to examine people’s reactions to e-cigarette risk messages, and they have primarily focused on either youth or smokers. Given that the rates of e-cigarette use among adult never smokers have been increasing (Bao et al., 2018) and smokers are susceptible to becoming dual users (Owusu et al., 2019), which prolongs their nicotine addiction and leads to increased health risks (Alzahrani et al., 2018), it is important to address how various audiences (younger and older adults, smokers, and non-smokers) react to e-cigarette prevention messages.

This study aims to identify and summarize the cognitive responses of U.S. adult smokers and non-smokers to e-cigarette risk messages with different message themes. We focus on cognitive variables related to e-cigarettes and evaluations of the messages, which are particularly important to risk message development and evaluation. We utilize the Health Belief Model and perceived message effectiveness as our theoretical framework, because numerous studies have shown that their constructs are instrumental to attitude and behavior change. Also, these constructs often serve as important outcomes and are measured using close-ended questions in health risk message testing studies (Noar et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2019).

Health Belief Model

As one of the most widely applied health behavior theories (Glanz et al., 2015), Health Belief Model (HBM, Janz & Becker, 1984) provides a means to understand why people engage in health-promoting behaviors, which can help design and evaluate effective public health messages. HBM states that a person’s likelihood of engaging in a health-promoting behavior is determined by three antecedents, including (a) perceived threat, comprising perceived susceptibility and perceived severity of a health condition and its consequences, (b) perceived benefits to engage in a health-promoting behavior, and (c) perceived barriers to performing the behavior. When an individual perceives high threat of a health condition and believes that the benefits of taking a health-promoting action exceed the barriers, the individual is ready to take the health-promoting action. Such readiness will be translated into an action when the individual sees internal (e.g., chest pain) or external (e.g., illness of family members) cues to action and believes they possess high self-efficacy to perform the behavior.

Studies have utilized HBM to predict intentions and behaviors of tobacco product cessation or use. Kathuria et al. (2019) found that higher perceived severity of smoking-related diseases, lower perceived barriers to quitting, and greater self-efficacy for quitting predicted greater likelihood of quitting smoking. Cues to action, such as hospitalization and symptoms of smoking-related diseases, also motivated smokers to quit. Moreover, a longitudinal study revealed that lower perceived threat of smoking predicted e-cigarette use for non-smokers (Cooper et al., 2018). As such, HBM serves as a useful framework to understand people’s cognitive responses to e-cigarette risk messages that are expected to motivate the action of staying away from e-cigarettes. Indeed, public health messages tend to achieve optimal behavior and attitude change if they can positively influence HBM constructs (Glanz et al., 2015). Thus, we are interested in whether people will think about HBM constructs after viewing e-cigarette risk messages, even when the messages were not developed based on HBM. We ask:

RQ1a. Which and to what extent are HBM constructs (i.e., perceived threat of vaping-related health issues, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and cues to action) present in viewers’ open-ended responses to e-cigarette risk messages?

Perceived Message Effectiveness

Perceived message effectiveness (PME) focuses on the audience’s perceptions of whether or not a message will be able to accomplish its goals of changing perceptions and behavior (Nabi, 2018). PME includes two related constructs (Noar, Bell, et al., 2018). The first construct is message perceptions, which are people’s judgment about the attributes of a message (Rucker & Petty, 2006), such as its credibility (e.g., “this message is believable”) and understandability (e.g., “this ad is easy to understand”). In other words, message perceptions index people’s assessment of the message features. The second construct is effect perceptions, which are evaluations of a message’s ability to change crucial theoretical antecedents to a behavior or behavior itself. For instance, the message may probe perceived impact of a message on one’s self-efficacy (e.g., “this message made me feel confident to quit vaping”) (Bigsby et al., 2013) or behavioral motivation (e.g., “this ad made me want to stay away from e-cigarettes”) (Niederdeppe et al., 2011). In other words, effect perceptions indicate people’s evaluations of the potential of a message to change their attitude, beliefs, and behaviors (Noar, Bell, et al., 2018).

PME could be a useful tool to select messages and project health messages’ potential to change behaviors (Cappella, 2018; Noar, Bell, et al., 2018). In the context of anti-smoking messages, meta-analysis indicated that PME predicted subsequent quit intentions and cessation behavior (Noar, Barker, et al., 2018). Some longitudinal data demonstrated that audience ratings of effect perceptions of PME predicted positive changes in quitting intentions and smoking behavior (Brennan et al., 2014). Similarly, message perceptions of PME at baseline were associated with increased likelihood of quit attempts at follow-up (Davis et al., 2017). Given the predictive value of PME for the eventual success of messages in changing beliefs or behaviors, we aim to understand how viewers evaluate the effectiveness of e-cigarette risk messages:

RQ2a. Which and to what extent are PME constructs (i.e., message perceptions and effect perceptions) present in viewers’ open-ended responses to e-cigarette risk messages?

Message Themes

According to Message Framing Theory (Pan & Kosicki, 2005), message frames in persuasion messages activate certain knowledge structures, making them more accessible. In turn, the activated themes in cognitive responses predict attitude and behavioral change. Shen (2010) found that compared to messages focusing on secondhand smoke and industry manipulation, messages highlighting health consequences of smoking elicited more thoughts on health consequences. Thoughts on health consequences but not thoughts on secondhand smoke and industry manipulation then predicted less favorable attitudes towards smoking. Thus, anti-smoking messages with different themes might be differentially effective for cessation and prevention. Indeed, messages that focused on the adverse consequences of smoking and secondhand smoke, as well as those that revealed the manipulative nature of the tobacco industry were more effective in preventing youths from smoking than messages using financial appeal, regulatory appeal, and personal testimonial (Niederdeppe et al., 2016).

In the context of e-cigarette risk communication, message themes also play an important role (Cavallo et al., 2019; Kong et al., 2016; Roditis et al., 2020). Roditis et al. (2020) found that youth who were susceptible to e-cigarette use responded favorably to messages emphasizing specific health consequences of e-cigarette use but did not find messages emphasizing addictiveness of e-cigarettes appealing. Similarly, e-cigarette risk messages evoked more fear and were rated more effective by youths when they focused on the negative consequences of e-cigarettes on teens’ brain development and the containment of harmful chemicals than when they emphasized addiction and nicotine (Noar et al., 2019). Overall, these findings suggest that message themes matter in shaping people’s responses to e-cigarette risk messages. In this study, we developed four e-cigarette risk messages focusing on different themes per prior research, including tobacco industry manipulation practice, financial and psychological cost, harmful chemicals, and uncertainty about the ingredients contained in e-cigarettes. We ask:

RQ1b. Do HBM constructs presented in viewers’ responses to e-cigarette risk messages differ across the message themes?

RQ2b. Do PME constructs presented in viewers’ responses to e-cigarette risk messages differ across the message themes?

Method

Participants

A national sample of 2,801 adults was recruited using multiple online recruitment strategies (e.g., web banners, website referrals, affiliate marketing, pay-per-click) by Toluna (www.toluna-group.com), a market research company. Participants who viewed the control message and those who provided invalid open-ended responses (e.g., “1234” “none”) were excluded, resulting in a study sample of 1,968 individuals. The study sample was 18–91 years old (M = 48.5, SD = 16.8), 53% women, 47% men. About 80% were White, 11% Black, and 9% other races; 35% had a bachelor’s degree or higher, 35% some college, and 30% high school and lower. No significant demographic differences were found across message conditions.

Participants included never smokers (never smoked or smoked less than 100 cigarettes, 36%), former smokers (smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime but were not currently smoking cigarettes, 6%), and current smokers (smoked at least 100 cigarettes and were currently smoking cigarettes every day or some days, 58%). In terms of e-cigarette use, 60% were never e-cigarette users (never used any e-cigarette products), 16% were former users (used e-cigarettes but not in the past 30 days), and 24% were current users (used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days).

Procedures

This paper examines open-ended responses to the messages from a larger online study investigating effects of e-cigarette risk messages (Owusu et al., in press). After providing informed consent, participants reported their sociodemographic information and past tobacco use. They were then randomly assigned to view one of the four e-cigarette risk messages (see Appendix 1). Immediately after viewing the message, participants were asked to “type in every thought that came to mind while looking at that picture.” They were given an unlimited amount of time and instructed to list as many thoughts as possible. The survey also measured variables reported elsewhere (Owusu et al., in press). Upon completion of the survey, participants were debriefed that the messages were used for research only and had not been approved by any public health or federal agency. A quit-line telephone number and links to smoking cessation websites were provided to all respondents. All research protocols were approved by the Georgia State University Institutional Review Board.

Four E-Cigarette Risk Messages

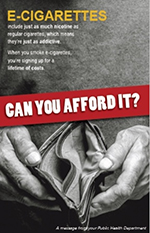

There are few publicly available e-cigarette risk messages designed specifically for smoker and non-smoker adults. Thus, Owusu et al. (2020) developed four messages that communicated harms of e-cigarette use (see Appendix 1). Based on themes in prior research (Kong et al., 2016; Noar et al., 2019) and existing anti-tobacco messages, our ads featured four themes: (a) Big tobacco revealed strategies employed by the tobacco companies to market their products, such as making products maximally addictive; (b) Can’t afford highlighted the economic and psychological consequences of e-cigarette use, including the cost of trying to satisfy one’s craving for nicotine; (c) Formaldehyde presented the harmful chemicals in e-cigarettes; and (d) Top secret emphasized that the content of e-cigarettes remains uncertain as tobacco companies are not required to list all of the ingredients.

Coding of Open-Ended Responses

A content analysis was conducted to identify the presence of the Health Belief Model (HBM) and perceived message effectiveness (PME) constructs in the data (0 = absent, 1 = present). The unit of analysis was each participant’s response. Table 1 summarizes the operational definitions and examples of the variables. We coded for five HBM constructs: (a) perceived health threat of vaping, (b) perceived benefits of not vaping (for this study, “not vaping” means staying away from e-cigarettes, including both not initiating and quitting, depending on participants’ vaping status), (c) perceived barriers to not vaping, (d) self-efficacy for not vaping, and (e) cues to action. We also coded for four PME factors, including (a) positive message perceptions, defined as positive evaluations of the message features such as message credibility and understandability, (b) negative message perceptions, (c) positive effect perceptions, defined as positive evaluation of the potential of a message to change people’s attitudes towards or behaviors about vaping, and (d) negative effect perceptions.

Table 1.

Operational Definitions and Examples of HBM and PME Constructs

| Constructs | Operational Definitions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| HBM Constructs | ||

| Perceived heath threat | Participants mentioned the health risk and harm of e-cigarette use and/or that e-cigarettes are as harmful as or more harmful than combusted cigarettes. | “Using e cigars can cause cancer and will be hospitalized or leads to death.” “No difference between e-cig and cig. Just as harmful for your body.” |

| Perceived benefits of not vaping | Participants mentioned the benefits of quitting vaping and/or not initiating vaping, such as financial, physical and mental benefits. | “E-cigarettes are expensive. I could save a lot of money by staying away from them.” “I have more energy almost immediately after I stop vaping.” |

| Perceived barriers to not vaping | Participants mentioned obstacles to quit vaping and/or appealing factors that encourage e-cigarette initiation. | “E-cig is addictive. I feel like I will never leave to quitting.” “Some people started vaping because of the many flavors, but then got hooked.” |

| Self-efficacy of not vaping | Participants mentioned their confidence in their abilities to quit vaping or not initiate vaping. | “I tried but it’s so difficult to quit. I don’t think I can ever stop vaping.” “Will people be able to give up a nasty habit? Absolutely no!” |

| Cues to action | Participants mentioned internal (e.g., personal physical and mental symptoms) or external (e.g., illness of close others, news reports, etc.) cues that remind them to quit vaping or not to initiate vaping. | “My chest pain made me think to quit vaping.” “Knowing that the company and government are trying to reduce the population of people by getting them addicted to e-cigarettes, vapers should really quit.” |

| PME Constructs | ||

| Positive message perceptions | Participants positively evaluated the message attributes and features, such as creditability, understandability, and other aspects of message design. | “The message is stated to be from Public Health. The message is accurate and believable.” “I liked the design look of the ad.” |

| Negative message perceptions | Participants negatively evaluated the message attributes and features. | “Nonsense! I never heard this claim before. I don’t believe it.” “The image is pretty plain and irrelevant to the message.” |

| Positive effect perceptions | Participants mentioned that the messages had positive influences on people’s perceptions and behaviors, such as increasing their negative attitudes towards vaping and motivating them to quit vaping. | “This picture made me feel like tobacco companies don’t care about my health as a person, which is true.” “Looking at the ad made me not want to use e-cigs.” |

| Negative effect perceptions | Participants mentioned that the messages were not effective in changing people’s attitudes or behaviors in the desired direction. | “I don’t think this ad will make me give up e cigarettes.” “This is just another propaganda. The ad will not make people quit vaping.” |

Note. HBM = Health Belief Model. PME = Perceived Message Effectiveness.

For each HBM and PME variable, the coding categories were mutually exclusive; that is, a construct was either present or absent in a response. However, a response may include multiple HBM and PME constructs. For instance, in the response, “Vaping is very bad for your health. This ad is a bit vague and probably intentionally so. This ad is believable,” the variables of perceived health threat (“very bad for your health”), positive message perceptions (“believable”), and negative message perceptions (“vague”) were present. All research team members read the responses to be familiar with the data and refined an initial codebook created by the first author. The first author then conducted a 3-hour training with the third author, in which the codebook was finalized. Then, the two members independently coded a random 20% of all responses. Intercoder reliability was high, with Krippendorff’s alphas ranging from .94 to 1. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. The first author then coded the remaining data.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS v26. Descriptive statistics assessed the frequency of the HBM and PME constructs in participants’ responses. Chi-square analyses examined how the presence of the constructs differs across the four message conditions. The Bonferroni method was used to adjust for post-hoc multi-group comparisons.

Results

Participants’ (N = 1,968) responses to e-cigarette risk messages ranged from one word (e.g., “cancer” “disgusting”) to 192 words (M = 13.52, SD = 13.61). Table 2 presents the overall percentage of each HBM and PME construct and the percentages across each message theme.

Table 2.

Frequencies of Coding Schemes by Message Condition

| Constructs | Big tobacco (n = 518), % |

Can’t afford (n = 504), % |

Formaldehyde (n = 492), % |

Top secret (n = 454), % |

Full Sample (N = 1,968), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBM Constructs | |||||

| Perceived heath threat | 27.99a | 40.87b | 45.12b | 41.41b | 38.67 |

| Perceived benefits of not vaping | 2.70b | 53.37c | 1.02a | 2.86b | 15.29 |

| Perceive barriers to not vaping | 10.23c | 17.46d | 0.61a | 3.30b | 8.08 |

| Self-efficacy of not vaping | 0.77a | 0.40a | 0.41a | 0.66a | 0.56 |

| Cues to action | 27.80c | 4.37a | 8.74b | 29.74c | 17.48 |

| PME Constructs | |||||

| Positive message perceptions | 29.54b | 12.30a | 11.59a | 8.37a | 15.75 |

| Negative message perceptions | 12.36b | 6.94a | 7.72a, b | 6.17a | 8.38 |

| Positive effect perceptions | 3.67a, b | 2.58a, b | 5.69b | 1.76a | 3.46 |

| Negative effect perceptions | 1.93a | 0.79a | 1.83a | 0.88a | 1.37 |

Note. Percentages in the first four columns are within condition percentages. Percentages that do not share a subscript letter differ at p < .05 by the post-hoc multi-group comparison using the Bonferroni correction. HBM = Health Belief Model. PME = Perceived Message Effectiveness.

Health Belief Model Constructs

Perceived health threat of vaping.

After message exposure, 38.67% of participants mentioned the health threat related to e-cigarette use, especially lung cancer. The proportions of participants mentioning perceived health threat differed significantly across the message conditions, χ2(3, N = 1,968) = 36.01, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .14. Post-hoc multi-group comparisons (i.e., comparing column proportions) revealed that while the percentages were not significantly different among Formaldehyde (45.12%), Top secret (41.41%), and Can’t afford (40.87%) conditions, the number of participants mentioning perceived health threat was significantly lower for Big tobacco (27.99%) than for other messages.

One participant pointed out, “E-cigarettes are dangerous. Bad for your lung and can cause cancer. I don’t want to die.” Another participant wrote, “It’s just a waste a horrible habit that could cost you your life.” Notably, while the messages focused on the absolute harm of e-cigarette use, most participants compared the health risk of e-cigarette use to that of smoking, with many indicating e-cigarettes are equally or even more harmful than traditional cigarettes. For instance, some mentioned that e-cigarettes “are just as harmful to your health as any other tobacco products” and “probably worse than cigarettes.”

Perceived benefits of not vaping (staying away from e-cigarettes).

Overall, 15.29% of respondents mentioned the benefits of quitting vaping or not initiating vaping, especially the financial benefits. The percentages of participants identifying perceived benefits differed significantly across the message conditions, χ2(3, N = 1,968) = 759.05, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .62. Perceived benefits of not vaping was mentioned most often for the Can’t afford condition (53.37%), significantly more frequently than for the Top secret (2.86%) and Big tobacco (2.70%) conditions. Perceived benefits of not vaping had the lowest number of mentions for the Formaldehyde condition (1.02%).

Participants’ discussion about the benefits of not vaping focused primarily on financial cost. One participant wrote, “If I stop vaping, I can save a lot of money.” Another indicated that “I thought about all of the money that I could have saved.” Other perceived benefits of not vaping included physical health benefits (e.g., “I can live longer” “I will not die in my 40s because of lung cancer”) and mental health rewards (e.g., “I feel great, healthy, and happy by achieving my goal [stopping use of e-cigarettes]”).

Perceived barriers to not vaping (staying away from e-cigarettes).

A total of 8.08% of participants mentioned obstacles to quitting vaping and appealing factors that encourage e-cigarette initiation. The chi-square test and post-hoc multi-group comparisons revealed that the Can’t afford condition produced the most mentions about perceived barriers to not vaping (17.46%), followed by Big tobacco (10.23%), Top secret (3.30%), and Formaldehyde (0.61%); χ2(3, N = 1,968) = 113.86, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .24. Both e-cigarette users and non-users mentioned addiction as a primary barrier to quit vaping. A current user wrote, “E-cigarettes are just as addicting as cigarettes. They contain the same stuff. Once you try them, you’re hooked.” A non-user mentioned, “If you start a bad habit now, it would be hard to quit, a never-ending addiction.” A few participants also mentioned that flavored e-cigarettes promote vaping initiation, “They are coming out with fruit flavored nicotine that is obviously marketed to the youth. It’s hard to say no to those different flavors.”

Self-efficacy of not vaping (staying away from e-cigarettes).

Only 0.56% of participants discussed their confidence in their abilities to quit vaping or not initiate vaping, and most of these comments focused on a lack of self-efficacy. The chi-square test found no difference in mentions of self-efficacy among the message conditions, χ2(3, N = 1,968) = 0.95, p = .913, Cramer’s V = .02; Big tobacco (0.77%), Top secret (0.66%), Formaldehyde (0.41%), and Can’t afford (0.40%). After viewing the Formaldehyde message, a current e-cigarette user said, “That’s what I am putting into my body. That’s why I want to stop vaping, but I find it very very hard and have been unable to.” Another user who viewed Big tobacco said, “I want to quit vaping, but not optimistic that getting off nicotine will be easy.” In contrast, one non-user mentioned, “That it is just bad, and addictive, as cigarettes. I’m really glad that I’m able to stay away from them.”

Cues to action.

Overall, 17.48% of participants indicated internal or external cues that reminded them about the risk of e-cigarettes and nudged them to quit vaping or not to initiate vaping. The percentages of participants mentioning this construct differed significantly across the message conditions, χ2(3, N = 1,968) = 171.67, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .16. More participants who viewed Top secret (29.74%) and Big tobacco (27.80%) mentioned cues to action than those who viewed Formaldehyde (8.74%). Cues to action were mentioned the least frequently in the Can’t afford condition (4.37%).

Most participants referred to external cues, such as family members’ poor health conditions due to using e-cigarettes (e.g., “My husband got really sick and developed a lung infection while using e-cigarettes”), other people’s vaping behaviors, (e.g., “I personally know a child age 13 taking one to school and the mom thinking nothing of it because it’s flavored! It’s just addictive as cigarettes”), and the tobacco industry’s manipulative practice (e.g., “Big tobaccos are liars. They keep you hooked on their products”). A few respondents indicated internal cues. “I coughed a lot lately. It’s maybe the time to throw my vape pens away,” a Top secret message viewer said.

Perceived Message Effectiveness Constructs

Positive message perceptions.

Overall, 15.75% of participants left positive remarks about the message attributes and features. The differences across conditions were significant, χ2(3, N = 1,968) = 103.77, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .23. Post-hoc multi-group comparisons showed that Big tobacco received most compliments about its message features (29.54%), followed by Can’t afford (12.30%), Formaldehyde (11.59%), and Top secret (8.37%).

Positive message evaluations included discussions about how credible a message was (e.g., “I have smoked for a long time and believe the ad statement is true.” “I believe the ad”) and how a message was “easy to understand” and “effective at making you understand the dangers of e-cigarettes.” In addition, participants commented that some ads had “cool font” and “good color,” and included “original ideas” and “informative messages.” Many viewers also stated that the messages caught their attention (e.g., “It immediately caught my attention.” “The word formaldehyde caught my eye”).

Negative message perceptions.

After viewing the messages, 8.38% of respondents left negative remarks about the message features, and the comments differed significantly across messages, χ2(3, N = 1,968) = 15.18, p = .002, Cramer’s V = .09. Post-hoc multi-group comparisons revealed that Big tobacco (12.36%) and Formaldehyde (7.72%) received more negative evaluations than Can’t afford (6.94%) and Top secret (6.17%) conditions. Most negative comments focused on the message design, such as the background color (e.g., “The dark background is too dark”), word font (e.g., “The words are too small”), and the pictures in the ads (e.g., “Solid message but the picture made no sense”). A few participants thought that their message was “more propaganda,” “untrusting,” and “a little too much in your face.”

Positive effect perceptions.

Overall, 3.46% of participants described the potential effects of these messages on people’s perceptions and intentions regarding vaping, mainly how the messages increased their negative attitudes towards e-cigarette use and encouraged quitting or not trying. The difference across conditions was significant, χ2(3, N = 1,968) = 12.50, p = .006, Cramer’s V = .08. More participants viewing Formaldehyde (5.69%) assessed its persuasion effects positively than those exposed to Top secret (1.76%). The percentages of viewers indicating positive effect perceptions did not differ between Big tobacco (3.67%) and Can’t afford (2.58%) conditions. A current e-cigarette user stated, “It scared me and made me want to stop vaping.” A former user wrote, “The picture makes me regret using e-cigarettes. I don’t really use e-cigarettes now, so the picture encouraged me to throw mine out.” And a never user said, “The information about e-cigarettes having nicotine made me less likely to try them.”

Negative effect perceptions.

Only a few (1.37%) respondents explicitly mentioned that these messages did not positively affect people’s attitudes and behaviors. They mentioned that the message was not effective in changing individuals’ attitudes and behaviors in the desired direction (e.g., “The message is not going to make people stop smoking.” “[The message] didn’t really convince me to quit using them”). Others pointed out that the message “utilized a scare tactic” and had adverse influences on people’s behaviors (e.g., “These propaganda posters just made me want to vape more”). The chi-square test found no difference across message conditions, χ2(3, N = 1,968) = 4.01, p = .261, Cramer’s V = .05; Big tobacco (1.93%), Formaldehyde (1.83%), Top secret (0.88%), and Can’t afford (0.79%).

We also examined but found no significant difference in the frequency of the HBM and PME constructs as a function of participants’ sociodemographic factors, smoking status, and e-cigarette use status (current, former, never; results not shown).

Discussion

This study aims to explore how U.S. adults respond to e-cigarette risk messages. We conducted a content analysis of 1,968 participants’ open-ended responses to one of four e-cigarette risk messages with different themes. Constructs of the Health Belief Model (HBM) were coded because those factors are important cognitive antecedents to behavior change and are frequently used to design public health messages. We also coded perceived message effectiveness (PME) to examine how participants judged the message features (i.e., message perceptions) and the persuasion effects of the messages (i.e., effect perceptions).

HBM Constructs

Public health messages are more likely to succeed if they can positively influence HBM constructs (Glanz et al., 2015). The first goal of this study was to explore whether people thought about cognitive antecedents to behavioral change identified by the HBM while viewing e-cigarette risk messages, even when the messages were not developed based on HBM. We found that all HBM constructs were present in participants’ open-ended responses. The results complement prior studies of e-cigarette risk messages that utilized closed-ended questions to measure HBM variables, which reminded participants about those constructs via survey questions, rather than allowing them to freely list whatever came to their mind. If viewers cannot naturally think about cognitive factors that theoretically motivate attitude and behavior change, researchers may not be able to confidently state that those factors are actual antecedents to attitude and behavior change. Using a content analysis approach, we found that even when the messages were not explicitly designed based on HBM and when people had the freedom to list any cognitive responses to the messages, participants still thought about HBM constructs.

Overall, perceived heath threat of vaping was mentioned the most frequently, and self-efficacy of not vaping was mentioned the least. The prominence of perceived health threat is not surprising given that our messages were designed to communicate the harms of e-cigarette use. Moreover, existing public health campaigns about e-cigarettes primarily focus on the negative health consequences of e-cigarette use (e.g., Real Cost Campaign; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2016). Exposure to our messages might trigger participants’ recall of existing campaign messages, making them more likely to mention health risks of vaping. However, few respondents mentioned that they were able to stay away from e-cigarettes, potentially due to the lack of efficacy information in our messages.

Across the four message conditions, certain HBM constructs were mentioned with different frequencies (see Table 2). Specifically, perceived health threat of vaping was mentioned the least frequently among Big tobacco viewers, maybe because the message primarily focused on industry manipulation rather than negative health consequences of e-cigarette use. As the image in Can’t afford (i.e., an empty wallet) centered on the financial cost of vaping, more than half of participants viewing the message mentioned perceived benefits of not vaping, especially the money that they could have saved by not using e-cigarettes. The text of Can’t afford also mentioned addictive nicotine, which may explain why perceived barriers to not vaping (i.e., addiction and habitual behaviors) had the largest number of mentions in this condition.

Moreover, cues to action was mentioned more often in Top secret and Big tobacco than in other message conditions. Some respondents who viewed Top secret mentioned that government agencies should regulate the tobacco companies to list all ingredients. Some Big tobacco viewers also indicated that the tobacco industry does not care about their health. Those thoughts serve as external cues to action, motivating people to stay away from e-cigarettes. Thus, consistent with Message Framing Theory, our findings suggested that different message themes in e-cigarette risk messages elicited different cognitive responses to the messages that matched the frames of the messages. This highlights the importance of considering message themes when designing e-cigarette risk messages.

The Can’t afford and Formaldehyde messages mainly elicited thoughts related to perceived health threat, perceived benefits of, and perceived barriers to not vaping; thus, the two messages may be useful to inform the public about the harms of vaping and prepare them for staying away from e-cigarettes. Because Big tobacco viewers frequently mentioned cues to action, this message may be particularly useful for those who have been ready but have not yet taken any action. As Top secret elicited many thoughts about perceived health threat and cues to action, this message may be effective for a wider range of audiences, from those who are preparing to act to those who are ready to act. Together, our findings suggested that messages with different themes elicited different cognitive responses, which can be used to determine the application and effectiveness of the messages among different audience groups.

PME Constructs

Past meta-analysis has shown that self-reported PME predicted subsequent quit intentions and cessation behavior (Noar et al., 2018). However, in the studies in that meta-analysis, participants were reminded to report their effectiveness thoughts by answering close-ended questions. We found that in their open-ended responses, viewers also commented on the effectiveness of the messages. PME research has recently begun to distinguish between message perceptions and effect perceptions (Yzer et al., 2015). In our study, participants more frequently mentioned what they thought about message characteristics (i.e., message perceptions) than about the impacts of the messages on their attitude and behavior change (i.e., effect perceptions). Given that heuristics, such as message design, source credibility, or presenter attractiveness, can also lead to persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), e-cigarette risk message designers should take both message themes and message heuristics into account. Future quantitative research should evaluate which construct – message perceptions or effect perceptions will better predict people’s belief and behavioral change in the context of e-cigarette risk communication. In addition, future studies should also explore whether a message needs to induce effectiveness thoughts to be effective in predicting quit intentions and cessation behavior.

Across the four message themes, very few participants who were exposed to Top secret reported positive evaluations about both the message features and anticipated effects. The Top secret message focused on the uncertainty about the ingredients of e-liquids. It utilized a tactic of uncertainty to evoke feelings of anxiety, which motivate people to engage in advised actions. However, the message did not highlight the self-efficacy of not vaping. When experiencing uncertainty and negative emotions, individuals without sufficient self-efficacy will be less likely to take a recommended action (Afifi & Weiner, 2004). Thus, a focus on uncertainty but a lack of efficacy components in the message may explain why the fewest participants mentioned the effectiveness of Top secret. Notably, it remains unclear whether participants will report more self-efficacy thoughts once efficacy information is added into e-cigarette risk messages. We encourage future studies to further explore how viewers react to messages with efficacy components, especially those using an uncertainty tactic.

Practical Implications

More participants commented on the message features than the persuasive effects of the messages. Given that heuristics can also result in persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), the finding suggests that in addition to persuasion arguments, e-cigarette risk message designers should pay also attention to features of their messages, such as fonts and colors, presenters in the pictures, and poster orientations (portrait vs. landscape) mentioned by our participants. In addition, e-cigarette risk message development is also suggested to focus on selecting proper message themes. For instance, compared to messages indicating e-cigarette companies are not required to list all of the harmful ingredients, messages emphasizing formaldehyde in e-cigarettes and the financial and psychological cost of vaping may be more effective in informing the public and increasing their intentions to stay away from e-cigarette use.

Limitations

We followed HBM and PME to conduct a content analysis of participants’ open-ended responses to e-cigarette risk messages. Coding theoretical constructs, rather than open coding (i.e., coding the data without theoretical themes) may ignore some other potentially useful information. However, coding HBM and PME factors can provide a nuanced understanding of the extent to which those constructs are present in people’s open-ended responses, which complements close-ended measure of those variables. Moreover, some variables, such as perceived risk of e-cigarettes and perceived response efficacy and self-efficacy were measured prior to exposure to the messages. This may have primed participants’ mentions of these variables, although given the very low frequency of self-efficacy mentions, it appears unlikely.

This study was cross-sectional. We are unable to identify how participants’ responses are related to their actual behavioral change. In addition, participants, on average, wrote 13 words in their responses, which may not thoroughly reflect their thoughts about the messages. Future studies should use individual in-depth interviews or focus groups to examine how viewers react to messages cognitively and emotionally. Moreover, although we selected the participants to be similar in demographic characteristics to the adult population in the United States, the sample was not nationally representative. The open-ended responses were also limited to the four e-cigarette risk messages, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Given that only one image per theme was used, the findings may only be applicable to this message rather than to other possible messages of the specific theme.

Conclusion

E-cigarette risk messages evoked thoughts related to cognitive antecedents of behavior change, such as perceived health threat, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and cues to action. Some participants also commented on the message features and persuasive effects of the messages. The results from the open-ended responses show that participants think about many theoretical variables that are often measured by closed-ended questions in message evaluation research. Different e-cigarette risk messages also resulted in different cognitive activities, suggesting combined use of these different themes to communicate the harms of e-cigarettes.

Appendix 1: Four E-cigarette Risk Messages

| Message | Message type | Headline | Body text | Endline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Formaldehyde

|

Harmful chemicals | E-Cigarettes: your daily dose of formaldehyde. | Sound familiar? It’s a chemical often found in embalming fluid, the substance used to preserve cadavers (dead bodies). Yup, it’s as bad as it sounds. | To learn more about what you’re inhaling, visit … A message from your Public Health Department |

Top secret

|

Uncertainty | Did you know? that e-cigarette companies ARE NOT required to list all the ingredients on the label? | In addition to what is listed on the label, you could be inhaling other harmful chemicals | Learn more about e-cigarettes by visiting … A message from your Public Health Department |

Big tobacco

|

Tobacco industry | Don’t fall for it: e-cigarettes are just another tool big tobacco is using to keep you addicted | Big tobacco wants you to think they care about your health by marketing e-cigarettes as a way to quit. | A message from your Public Health Department |

Can’t afford

|

Economic costs | Can you afford it? | E-cigarettes include just as much nicotine as regular cigarettes, which means they are just as addictive. When you smoke e-cigarettes, you’re signing up for a lifetime of costs. | A message from your Public Health Department |

References

- Afifi WA, & Weiner JL (2004). Toward a theory of motivated information management. Communication Theory, 14(2), 167–190. 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00310.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani T, Pena I, Temesgen N, & Glantz SA (2018). Association between electronic cigarette use and myocardial infarction. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(4), 455–461. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao W, Xu G, Lu J, Snetselaar LG, & Wallace RB (2018). Changes in electronic cigarette use among adults in the united states, 2014–2016. JAMA, 319(19), 2039–2041. 10.1001/jama.2018.4658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigsby E, Cappella JN, & Seitz HH (2013). Efficiently and effectively evaluating public service announcements: Additional evidence for the utility of perceived effectiveness. Communication Monographs, 80(1), 1–23. 10.1080/03637751.2012.739706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Morel-Espinosa M, Rees J, Sosnoff C, Cowan E, Gardner M, Wang L, Valentin-Blasini L, Silva L, De Jesús VR, Kuklenyik Z, Watson C, Seyler T, Xia B, Chambers D, Briss P, King BA, Delaney L, Jones CM, … Pirkle JL (2019). Evaluation of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients in an outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury 10 states, August-October 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(45), 1040–1041. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845e2external [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan E, Durkin SJ, Wakefield MA, & Kashima Y (2014). Assessing the effectiveness of antismoking television advertisements: Do audience ratings of perceived effectiveness predict changes in quitting intentions and smoking behaviours? Tobacco Control, 23(5), 412–418. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappella JN (2018). Perceived message effectiveness meets the requirements of a reliable, valid, and efficient measure of persuasiveness. Journal of Communication, 68(5), 994–997. 10.1093/joc/jqy044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo DA, Kong G, Ells DM, Camenga DR, Morean ME, & Krishnan-Sarin S (2019). Youth generated prevention messages about electronic cigarettes. Health Education Research, 34(2), 247–256. 10.1093/her/cyz001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2020). Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

- Cooper M, Loukas A, Case KR, Marti CN, & Perry CL (2018). A longitudinal study of risk perceptions and e-cigarette initiation among college students: Interactions with smoking status. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 186, 257–263. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, Chang JT, Anic GM, Wang TW, Creamer MR, Jamal A, Ambrose BK, & King BA (2019). E-cigarette use among youth in the united states, 2019. JAMA, 322(21), 2095–2103. 10.1001/jama.2019.18387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Duke J, Shafer P, Patel D, Rodes R, & Beistle D (2017). Perceived effectiveness of antismoking ads and association with quit attempts among smokers: Evidence from the tips from former smokers campaign. Health Communication, 32(8), 931–938. 10.1080/10410236.2016.1196413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Viswanath K (2015). Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (5th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, & Becker MH (1984). The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly, 11(1), 1–47. 10.1177/109019818401100101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathuria H, Seibert RG, Cobb V, Herbst N, Weinstein ZM, Gowarty M, Jhunjhunwala R, Helm ED, & Wiener RS (2019). Perceived barriers to quitting cigarettes among hospitalized smokers with substance use disorders: A mixed methods study. Addictive Behaviors, 95, 41–48. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khouja JN, Suddell SF, Peters SE, Taylor AE, & Munafò MR (2020). Is e-cigarette use in non-smoking young adults associated with later smoking? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tobacco Control. Advance online publication. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BA, Gammon DG, Marynak KL, & Rogers T (2018). Electronic cigarette sales in the United States, 2013–2017. JAMA, 320(13), 1379–1380. 10.1001/jama.2018.10488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Morean ME, & Krishnan-Sarin S (2016). Preference for gain- or loss-framed electronic cigarette prevention messages. Addictive Behaviors, 62, 108–113. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen RC, Gottlieb MA, Shaefer RMW, Winickoff JP, & Klein JD (2014). Trends in electronic cigarette use among us adults: Use is increasing in both smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 17(10), 1195–1202. 10.1093/ntr/ntu213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabi RL (2018). On the value of perceived message effectiveness as a predictor of actual message effectiveness: An introduction. Journal of Communication, 68(5), 988–989. 10.1093/joc/jqy048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 10.17226/24952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Avery R, Byrne S, & Siam T (2016). Variations in state use of antitobacco message themes predict youth smoking prevalence in the USA, 1999–2005. Tobacco Control, 25(1), 101–107. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Farrelly MC, Nonnemaker J, Davis KC, & Wagner L (2011). Socioeconomic variation in recall and perceived effectiveness of campaign advertisements to promote smoking cessation. Social Science & Medicine, 72(5), 773–780. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Barker J, Bell T, & Yzer M (2018). Does perceived message effectiveness predict the actual effectiveness of tobacco education messages? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Communication, 35(2), 148–157. 10.1080/10410236.2018.1547675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Bell T, Kelley D, Barker J, & Yzer M (2018). Perceived message effectiveness measures in tobacco education campaigns: A systematic review. Communication Methods and Measures, 12(4), 295–313. 10.1080/19312458.2018.1483017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Rohde JA, Horvitz C, Lazard AJ, Cornacchione Ross J, & Sutfin EL (2019). Adolescents’ receptivity to e-cigarette harms messages delivered using text messaging. Addictive Behaviors, 91, 201–207. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Rohde JA, Prentice-Dunn H, Kresovich A, Hall MG, & Brewer NT (2020). Evaluating the actual and perceived effectiveness of E-cigarette prevention advertisements among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 109, Article 106473. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osei AD, Mirbolouk M, Orimoloye OA, Dzaye O, Uddin S, Benjamin EJ, Hall ME, DeFilippis AP, Stokes A, Bhatnagar A, Nasir K, & Blaha MJ (2019). Association between e-cigarette use and cardiovascular disease among never and current combustible-cigarette smokers. The American Journal of Medicine, 132(8), 949–954. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu D, Huang J, Weaver SR, Pechacek TF, Ashley DL, Nayak P, & Eriksen MP (2019). Patterns and trends of dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes among U.S. adults, 2015–2018. Preventive Medicine Reports, 16, Article 101009. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.101009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu D, Lawley R, Yang B, Henderson K, Bethea B, LaRose C, Stallworth S, & Popova L (2020). “The lesser devil you don’t know”: A qualitative study of smokers’ responses to messages communicating comparative risk of electronic and combusted cigarettes. Tobacco Control, 29(2), 217–223. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owusu D, Massey Z, & Popova L (in press). An experimental study of messages communicating potential harms of electronic cigarettes. PLOS One. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paek H-J, Kim S, Hove T, & Huh JY (2014). Reduced harm or another gateway to smoking? Source, message, and information characteristics of e-cigarette videos on YouTube. Journal of Health Communication, 19(5), 545–560. 10.1080/10810730.2013.821560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z, & Kosicki GM (2005). Framing and the understanding of citizenship. In Dunwoody S, Becker LB, Kosicki GM, & McLeod D (Eds.), The evolution of key mass communication concepts (pp. 167–207). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, & Cacioppo JT (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and persuasion (pp. 1–24). Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds-Tylus T, Bigsby E, & Quick BL (2020). A comparison of three approaches for measuring negative cognitions for psychological reactance. Communication Methods and Measures. Advance online publication. 10.1080/19312458.2020.1810647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roditis ML, Dineva A, Smith A, Walker M, Delahanty J, lorio E, & Holtz KD (2020). Reactions to electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) prevention messages: Results from qualitative research used to inform FDA’s first youth ENDS prevention campaign. Tobacco Control, 29, 510–515. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker DD, & Petty RE (2006). Increasing the effectiveness of communications to consumers: Recommendations based on elaboration likelihood and attitude certainty perspectives . Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25(1), 39–52. 10.1509/jppm.25.1.39 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L (2010). The effect of message frame in anti-smoking public service announcements on cognitive response and attitude toward smoking. Health Communication, 25(1), 11–21. 10.1080/10410230903473490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2016). The Real Cost campaign. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/PublicHealthEducation/PublicEducationCampaigns/TheRealCostCampaign/default.htm

- Walter N, Demetriades SZ, & Murphy ST (2019). Just a spoonful of sugar helps the messages go down: Using stories and vicarious self-affirmation to reduce e-cigarette use. Health Communication, 34(3), 352–360. 10.1080/10410236.2017.1407275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis E, Haught MJ, & Morris Ii DL (2017). Up in vapor: Exploring the health messages of e-cigarette advertisements. Health Communication, 32(3), 372–380. 10.1080/10410236.2016.1138388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Owusu D, & Popova L (2019). Testing messages about comparative risk of electronic cigarettes and combusted cigarettes. Tobacco Control, 28(4), 440–448. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yzer M, LoRusso S, & Nagler RH (2015). On the conceptual ambiguity surrounding perceived message effectiveness. Health Communication, 30(2), 125–134. 10.1080/10410236.2014.974131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]