Abstract

When the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed, it fundamentally changed end-of-life care for children. Concurrent Care for Children (ACA, section 2302) enables Medicaid/CHIP children with a 6 month to live prognosis to use hospice care while continuing treatment for their terminal illness. Although ACA, section 2302 was enacted a decade ago, little is known about these children. The purpose of this study was to generate the first-ever national profile of children enrolled in concurrent hospice care. Using data from multiple sources including US Medicaid data files from 2011 to 2013, a descriptive analysis of the demographic, community, hospice, and clinical characteristics of children receiving concurrent hospice care was conducted. The analysis revealed that the national sample was extremely medically complex, even for children at end of life. They received care within a complicated system involving primary care providers, hospices, and hospitals. These findings have clinical and care coordination implications for hospice nurses.

Keywords: pediatric, concurrent hospice care, end-of-life care, hospice care, Medicaid

The passage of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) fundamentally changed end-of-life care for children. Concurrent Care for Children (ACA, section 2302) is landmark federal legislation that enables Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) children with a 6 month to live prognosis to enroll in hospice care while continuing to receiving care to treat their terminal illness.1 This Medicaid benefit is available to children under 21 years. Concurrent care ensures that families are never required to stop life-prolonging care in order to receive quality care from an interdisciplinary hospice team focused on comfort. As an example, a child living with cancer and a six-month prognosis is entitled to continue chemotherapy once enrolled in hospice care. Among the 30,000 children who die annually in the United States (US) with health-related conditions, concurrent hospice care offers continuity of care for children and their families at end of life.2

ACA, section 2302 was enacted a decade ago, and yet, information on children receiving concurrent hospice care is surprisingly scarce.3 What is known has focused on policy and clinical implementation of concurrent care. In a recent policy study, researchers examined state-level implementation of pediatric concurrent care and found significant variation in publicly-available guidelines on implementing this care.1 While states such as Michigan offered guidance on payment, care coordination, and staffing, nineteen states provided no state-specific guidelines on concurrent care. From a clinical perspective, Lindley and Morvant discussed the challenges of hospitalizing a child receiving concurrent hospice care.4 The primary challenge identified was understanding the reason for the child’s inpatient admission. Admission for hospice care issues are often not clearly distinguished from admissions for treatment of the life-limiting illness. These authors offered recommendations for navigating the complicated hospitalization scenario including the creation of a Medicaid concurrent care navigator to assist with preauthorization and payment issues within Medicaid. This literature highlights the complexity of implementing concurrent care; however, an overall description of the children receiving concurrent hospice care is lacking.

Understanding the children who receive concurrent hospice care is clinically important and policy relevant. Knowledge about the demographic characteristics of children and the actual clinical care used will provide information for hospice nurses that has not been previously available and will offer key insights into health and health care needs of these children. From a policy perspective, understanding the hospice and community characteristics of where children received concurrent care will provide important information on utilization. Given the current policy environment surrounding the ACA, improving knowledge about the children receiving this important benefit will inform the policy discussion. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe the children receiving concurrent hospice care in a national sample of Medicaid beneficiaries.

Dimension of Pediatric Concurrent Hospice Care

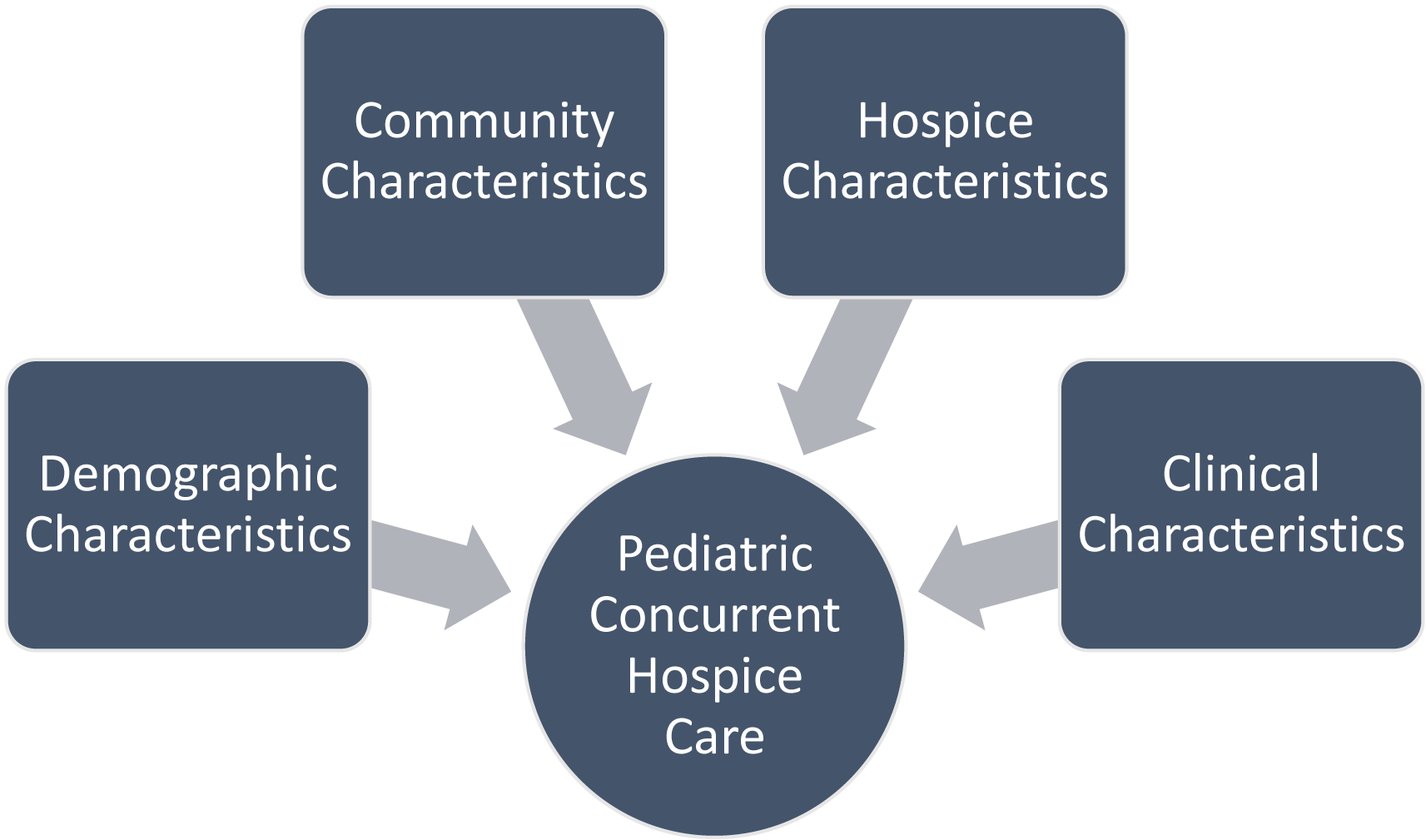

Consistent with prior relevant pediatric hospice studies, the analysis focused on the following dimensions of pediatric concurrent hospice care: demographic, community, hospice, and clinical characteristics (Figure 1).2,3 Demographic characteristics were included because studies have shown the influence of factors such as age and health on hospice use.5,6 It is also known that community characteristics may impact the receipt of pediatric hospice care. Children who reside in rural areas or areas with significant poverty might not have access to pediatric hospice care.7 Previous work has also demonstrated the importance of hospice characteristics on hospice care among children and their families.8 Finally, the clinical characteristics of hospice care including live discharges and hospice transitions are critical indicators of quality concurrent hospice care for children.6

Figure 1.

Dimensions of Pediatric Concurrent Hospice Care

Methods

Design & Sample

Data from the 2011 to 2013 US Medicaid data files were used in this retrospective descriptive analysis. A total of 21,383 children enrolled in Medicaid hospice care from 1/1/2011 to 12/31/2013 were the sampling frame. For the purpose of this study, children who concurrently used non-hospice, medical services on the same day as hospice care based on their Medicaid claims activity dates were included in the study.9,10 Observations were excluded if date of birth or death were missing or participants were over 21 years. The final sample was 6,243 children who received concurrent hospice care. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Tennessee, Knoxville Institutional Review Board.

Data Sources

Multiple data sources were used for the study. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) collects and prepares the Medicaid Analytical Extract (MAX) files, which are person-level, administrative claims files from data submitted electronically by all 50 states and the District of Columbia.11 Four MAX files were used: Personal Summary (enrollment and demographic information), Other Therapy (diagnosis and procedure information), Inpatient (hospitalization data on service dates and procedure codes), and Prescription Drug (information on prescription fill dates and national drug codes). Medicaid claims data were used because it is one of the few data sources that includes hospice information on children in all states. Additionally, data were used from 2011 because this is the first full year that concurrent care was enacted and 2013 was used because it is the most current year for which data were available. Another source of data was the publicly-available 2010 US Census files. These data provided information on community characteristics. Finally, the publicly-available CMS Hospice Provider of Services files and CMS Hospice Utilization and Payment files were used for information on hospice providers.

Measures

Demographic Characteristics.

Age was categorized as < 1 year, 1 to 5 years, 6 to 14 years, and 15 to 20 years. Gender was dichotomized as girls and boys. The child’s race was operationalized as Caucasian or non-Caucasian, while ethnicity was Hispanic versus non-Hispanic. Using the Feudtner et al. definition, a measure of complex chronic condition was created.12 Individual measures for each of the complex chronic conditions (i.e., neurologic/neuromuscular, cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, gastrointestinal, hematologic/immunologic, metabolic, other congenital or genetic defect, malignancy, premature/neonatal, and miscellaneous) were also created. Multiple complex chronic conditions were defined as 2 or more complex chronic conditions. Mental/behavioral disorder was whether a child had a mental or behavioral diagnosis.13 Technology dependence was defined as requiring medical technology or devices.12

Community Characteristics.

Rural/urban was defined using the Health Resources & Services Administration definition of rurality.14 The four census regions of Midwest, Northeast, South, and West were the regional categories. The median county-level income within the home was the measure of household income. Individual measures for each state and the District of Columbia were also created.

Hospice Characteristics.

The size of a hospice was dichotomized as ≤ 50 employees or > 50 employees. A measure of hospice ownership, which was defined as for-profit versus non-profit & government was created. The hospice’s organizational age was measured as the number of years the hospice was a licensed provider. Pediatric program was whether or not the hospice had a dedicated patient services for children.

Clinical Characteristics.

Hospice live discharge was defined as the number of times a child discontinued hospice care for a day or more and then re-enrolled in hospice care. Two measures of hospice transitions were created and defined as whether health care was used after hospice discontinuation: emergency room use and inpatient admission. Hospice length of stay was calculated as the total number of days a child was enrolled in hospice care. Enrollment in hospice care for a single day was the measure of 1-day hospice admission. Primary care visit was defined as whether a child received care from their primary care provider or pediatrician during the hospice enrollment. Non-hospice symptom management was defined as receiving care for constipation symptoms from a non-hospice provider during the hospice enrollment. Provider coordination was measured by the number of non-hospice providers seen during hospice enrollment and insurance coordination was defined as having private health insurance along with Medicaid.

Analysis Plan

A secondary analysis of the data was conducted for this study. Descriptive statistics were calculated on the demographic, community, hospice, and clinical characteristics. The results are presented as univariate distributions and means. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.15 Microsoft Office Excel version 19 was used to create the map illustrating the number of pediatric concurrent care patients in each state.16

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of children in concurrent hospice care. Among the 6,243 children, the average age was 7 years (not shown). The most common age group was 1 to 5 years (38.0%) and the least common was infants less than 1 year (10.9%). Girls (48.5%) and boys (51.5%) were evenly represented with similar distribution between Caucasian (51.1%) and non-Caucasian (48.9%) children. Approximately a quarter (23.2%) of the sample was Hispanic. More than half (56.4%) of the children had a complex chronic condition and 39% presented with multiple complex chronic conditions. The distribution of specific complex chronic conditions is displayed in Figure 2 with miscellaneous conditions being the most common (37%) diagnoses, followed by cardiovascular (26%) and neurologic/neuromuscular (26%) conditions. More than 40% of children had a mental/behavioral disorder and a third of children were technology dependent.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, 2011–2013 (n= 6,243)

| Variables | n | % or mean (std dev) |

|---|---|---|

| Age Groups | ||

| <1 yr | 681 | 10.9% |

| 1 to 5 yrs | 2400 | 38.0% |

| 6 to 14 yrs | 1967 | 31.1% |

| 15 to 20 yrs | 1251 | 20.0% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 3029 | 48.5% |

| Male | 3214 | 51.5% |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 3190 | 51.1% |

| Non-Caucasian | 3053 | 48.9% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 1449 | 23.2% |

| Non-Hispanic | 4794 | 76.8% |

| Complex Chronic Condition | 3519 | 56.4% |

| Multiple Complex Chronic Conditions | 2409 | 38.6% |

| Mental/Behavioral Disorders | 2606 | 41.7% |

| Technology Dependence | 1991 | 31.9% |

Figure 2.

Prevalence of complex chronic conditions by type, 2011–2013

Note. Unable to report renal/urologic and premature/neonatal conditions because <10% in accordance with Data Use; complex chronic conditions were not mutually exclusive.

Community Characteristics

The community characteristics of the children in the study are shown in Table 2. A majority (61.4%) of study participants resided in urban areas of the US. The most common region of residence was the northeast (49.3%) and the least common was the West (10.0%). The median household income was $59,000/annually in communities where children resided. The top 5 states with pediatric concurrent hospice care use were New York (n=2,809), Ohio (n=1,076), California (n=500), Texas (n=332), and Pennsylvania (n=232) as noted in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Community Characteristics, 2011–2013 (n= 6,243)

| Variables | n | % or mean (std dev) |

|---|---|---|

| Rural/Urban | ||

| Urban | 3833 | 61.4% |

| Rural | 2415 | 38.6% |

| Region | ||

| Midwest | 1427 | 22.9% |

| Northeast | 3081 | 49.3% |

| South | 1111 | 17.8% |

| West | 624 | 10.0% |

| Household Income (median) | 6243 | $59,432(15295) |

Note: std dev = standard deviation

Figure 3.

Number of pediatric concurrent hospice care patients, 2011–2013

Hospice Characteristics

Table 3 displays the characteristics of hospices that provided pediatric concurrent hospice care. A majority of hospices (61.3%) had 50 or less employees. It was common for these hospices to be for-profit (61.3%). The average organizational age of hospices was 19 years, and slightly more than a third of the hospices (37.2%) had dedicated pediatric program.

Table 3.

Hospice Characteristics, 2011–2013 (n= 6,243)

| Variables | n | % or mean (std dev) |

|---|---|---|

| Size | ||

| 50 or less employees | 3826 | 61.3% |

| More than 50 employees | 2417 | 38.7% |

| Ownership | ||

| For profit | 3839 | 61.3% |

| Non-profit/Government | 2418 | 38.7% |

| Organizational Age | 6243 | 18.6 (9.56) |

| Pediatric Program | 2320 | 37.2% |

Note: std dev = standard deviation

Clinical Characteristics

The clinical characteristics of concurrent hospice care are listed in Table 4. Children receiving concurrent care discharged and reenrolled in hospice care on average 20 times at end of life. Almost 20% of children in concurrent care transitioned out of hospice to use the emergency room, while 11% transitioned for inpatient care. The average hospice length of stay for those receiving concurrent care was 89 days. A third of these children experienced a 1-day hospice admission. More than half of the children during concurrent care (58.9%) continued to visit their primary care physician. Less than a quarter of children in the study (19%) received treatment for their constipation from a non-hospice provider. Care was coordinated on average between a hospice and 2 non-hospice providers during concurrent care, and a third of the children were dually insured by Medicaid and private insurance that required coordination between payers.

Table 4.

Clinical Characteristics, 2011–2013 (n= 6,243)

| Variables | n | % or mean (std dev) |

|---|---|---|

| Hospice Live Discharge | 6243 | 19.5 (10.7) |

| Hospice Transitions | ||

| Emergency Room Use | 1216 | 19.5% |

| Inpatient Admission | 678 | 10.9% |

| Hospice Length of Stay | 6243 | 88.5 (109.8) |

| 1-Day Hospice Admission | 2025 | 32.4% |

| Primary Care Visit | 3674 | 58.9% |

| Non-Hospice Symptom Management | 1214 | 19.5% |

| Provider Coordination | 6243 | 1.9 (2.40) |

| Insurance Coordination | 2008 | 32.2% |

Note: std dev = standard deviation

Discussion

This study is one of the first to describe children receiving pediatric concurrent hospice care in a national Medicaid sample. It sought to understand the demographic, community, hospice, and clinical characteristics of these children from 2011 to 2013. The pattern that emerged was one of striking complexity - medically complex children receiving care within a complicated system involving primary care providers, hospice stays, and care within the hospital with variation by state.

The findings from the study demonstrated that children in concurrent care were medically complex, even at end of life. Many children in the study had at least one complex, and frequently two or more complex chronic conditions. More than one-quarter had cardiovascular conditions and a similar number had neurologic or neuromuscular conditions. The children also suffered with mental health disorders and were technology dependent. While the information on complex chronic conditions is similar to prior research of children in non-concurrent or standard hospice care,17 this study provided new evidence on the added complexity of mental/behavioral health and technology dependence. Given the health profile of the children in this study, it would be expected that most children entered concurrent hospice care after lengthy illnesses requiring significant family support in the home as well as a history with multiple providers and services. These are exactly the children who stand to benefit most from concurrent care, which allows continued support for needed technology, for example, along with symptom management and home support. However, this profound medical complexity may have challenged home hospice nurses that have not traditionally remained involved in care after hospitalizations, emergency room visits, or prolonged illness courses.18

The study showed that use of concurrent care varied by state. The profile of children receiving concurrent care suggests their communities are characterized by urban areas of the northeast, where three (OH, NY, PA) out of the top five states (OH, NY, PA, TX, and CA) with the most pediatric concurrent care patients resided. This finding was consistent with prior work examining implementation of pediatric concurrent hospice care.1,19 These states represent early adopters of pediatric concurrent hospice care and often had state-level, publicly-available implementation guidelines. It is possible that that active and early state-level involvement in implementation of health care policies focused on pediatric end-of-life care may impact the number of children using the Medicaid benefit. Additional research might explore the role of state implementation practices on use of concurrent care among children and their families. The finding also revealed that using pediatric concurrent hospice care was not consistent across states and that some children might not have the same access to this care depending on where they live. The concentration of these services located within the northeast raises many questions for how children and their families access and navigate the aforementioned complexities in more rural parts of the southeast, mid-west, and western parts of the nation. More research is need to understand the influence of the community on receiving concurrent care.

Among the children in the study, the analysis revealed that patients experience complex clinical care. The children and their families sought care from a variety of providers including their primary care physician and in various settings including hospice, ER, inpatient, and clinic. They cycled in and out of hospice care on average 20 times and in a third of cases were only enrolled in hospice care for a single day. While their length of stay in hospice was longer than studies have shown in standard pediatric hospice care,20 this finding was expected given these children were receiving life-prolonging care and hospice care. However, families and care-providers of children who use concurrent care services must deal with a complex system of care that involves primary care utilization as well as navigating both hospice and hospital stays.21 This evidence suggests children who use concurrent care services transition among hospice and non-hospice providers frequently. These transitions require coordination between 2 or more non-hospice providers as well as coordination among private and Medicaid insurers, adding to the complexities in the pattern of care for children who use concurrent care services. Furthermore, many states such as Montana require the hospice to designate a nurse to coordinate all the care activity for these children.1. Care coordination under concurrent hospice care is a complicated undertaking requiring coordination of a vast network of the child’s providers, services, treatments, therapies, and medications. Clearly, additional nursing research is warranted to understand the role of and the impact on the hospice nurse in coordinating care for children receiving pediatric concurrent hospice care.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, it was limited to children enrolled in Medicaid; however, considering the large number of enrollees, and that some of the children in the study had additional private insurance plans, the findings of this study may be generalized to non-Medicaid populations as well. Second, the data in this study covered only the first three years of the ACA. These were the most recent data available. Third, the descriptive design of this study also precludes drawing conclusions about the effects of concurrent care implementation, but it provides an in-depth baseline of information that can be used in future studies. Finally, the findings of this study may not be applicable to outside the US because concurrent care is uniquely a US Medicaid care delivery model.

Clinical Implications

Despite the study limitations, the findings from the study have important clinical implications. The study results highlight the importance for hospice nurses to develop foundational understanding of pediatric concurrent hospice care even if their hospice does not have specialized pediatric program. The children receiving concurrent hospice care are medically complex and will require hospice nurses to have advanced knowledge of pediatric medical conditions, treatments, therapies, and medications. General information about concurrent care can be obtained from these sources:

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organizations – Concurrent Care for Children Implementation Toolkit https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/CCCR_Toolkit.pdf

Pediatric Concurrent Hospice Care Information Repository https://pedeolcare.utk.edu/

Additionally, the complex health care system used by these children and their families suggests the need for advanced care coordination skills among hospice nurses. A hospice nurse may need additional training and education on care coordination. While care coordination might already be an important part of the hospice nurse toolkit, concurrent care will require additional skills.

Conclusions

In summary, the inclusion of concurrent care for children in the Affordable Care Act offered the opportunity to align care models with parents’ goals for their terminally-ill children. In this first step toward understanding care delivered under the concurrent care provision, significant medical complexity among children as well as high numbers of care transitions and providers in a complex system of care were identified using an administrative claims data. Continued attention to the complexity of caring for these children will require hospice nurse attention. Pediatric concurrent hospice care has important implications for the clinical care and care coordination provided by hospice nurses.

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to Ms. Jamie Butler, Ms. Kerri Qualls, and Ms. Theresa Profant for their assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Funding: This publication was made possible by Grant Number R01NR017848 from the National Institute of Nursing Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Contributor Information

Lisa C. Lindley, College of Nursing, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996.

Melanie J. Cozad, Department of Health Services Policy and Management, Center for Effectiveness Research in Orthopedics, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29201.

Radion Svynarenko, College of Nursing, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996.

Jessica Keim-Malpass, School of Nursing, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 22908,.

Jennifer W. Mack, Department of Pediatric Oncology and Division of Population Sciences, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02214.

References

- 1.Laird JM, Keim-Malpass J, Mack JW, Cozad MJ, Lindley LC. Examining variation in state Medicaid implementation of ACA: The case of Concurrent Care for Children. Health Aff. 2020;39(10):1770–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindley LC. Health care reform and concurrent curative care for terminally ill children: A policy analysis. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2011;13(2):81–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindley LC, Keim-Malpass J, Svynarenko R, Cozad MJ, Mack JW, Hinds PS. Pediatric concurrent hospice care: A scoping review and directions for future research. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2020;22(3):238–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindley LC, Morvant A. How to hospitalize a child receiving concurrent hospice care. NHPCO Pediatr e-Journal. 2020;6:6164. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindley LC, Newnam KM. Hospice use for infants with life-threatening health conditions, 2007 to 2010. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31(1):96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keim-Malpass J, Lindley LC. End-of-life transitions and hospice utilization for adolescents: Does having a usual source of care matter? J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2017;19(4):376–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roeland E, Lindley LC, Gilbertson-White S, Saeidzadeh S, Currie E, Friedman S, Bakitas M, Mack JW. End-of-life care among adolescent and young adult cancer patients living in poverty. Cancer. 2019;126(4):886–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindley LC, Edwards SL. Geographic variation in pediatric hospice care for children and adolescents in California, 2007–2010. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(1):15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mor V, Joyce NR, Cote DL, Gidwani RA, Ersek M, Levy CR, Faricy-Anderson KE, Miller SC, Wagner TH, Kinosian BP, Lorenz KA, Shreve ST. The rise of concurrent care for veterans with advanced cancer at end of life. Cancer. 2016;22(5):782–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mor V, Wagner TH, Levy C, Ersek M, Miller SC, Gidwani-Marszowski R, Joyce N, Faricy-Anderson K, Corneau EA, Lorenz K, Kinosian B, Shreve S. Association of expanded VA hospice care with aggressive care and cost for veterans with advanced lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(6):810–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruttner L, Borck R, Nysenbaum J, Williams S. Guide to MAX data. Medicaid Policy Brief #21 Washington, D.C.: Mathematica Policy Research; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: Updated for ICD-10 and complex technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garfield LD, Brown DS, Allaire BT, Ross RE, Nicol GE, Raghaven R. Psychotropic drug use among preschool children in the Medicaid program from 36 states. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):524–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health Resources and Services Administration. 2018. Defining rural population. Retrieve from https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/index.html

- 15.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel. https://office.microsoft.com/excel. 2018.

- 17.Lindley LC, Shaw S-L. Who are the children enrolled in hospice care? J Special Pediatr Nurs. 2014;19(4):308–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller EG, Laragione G, Kang TI, Feudtner C. Concurrent care for the medically complex child: Lessons of implementation. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:1281–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keim-Malpass J, Lindley LC. Repeal of the Affordable Care Act Will Negatively Impact Children at End of Life. Pediatr. 2017;140(3):e20171134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindley LC. Multiple complex chronic conditions and pediatric hospice utilization among California Medicaid beneficiaries, 2007–2010. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(3):241–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mooney-Doyle K, Lindley LC. Family and child characteristics associated with caregiver challenges for medically complex children. Fam Comm Health. 2019;43(1): 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]