Abstract

Background

The hormone ghrelin stimulates food intake, promotes adiposity, increases body weight, and elevates blood glucose. Consequently, alterations in plasma ghrelin levels and the functioning of other components of the broader ghrelin system have been proposed as potential contributors to obesity and diabetes. Furthermore, targeting the ghrelin system has been proposed as a novel therapeutic strategy for obesity and diabetes.

Scope of review

The current review focuses on the potential for targeting ghrelin and other proteins comprising the ghrelin system as a treatment for obesity and diabetes. The main components of the ghrelin system are introduced. Data supporting a role for the endogenous ghrelin system in the development of obesity and diabetes along with data that seemingly refute such a role are outlined. An argument for further research into the development of ghrelin system-targeted therapeutic agents is delineated. Also, an evidence-based discussion of potential factors and contexts that might influence the efficacy of this class of therapeutics is provided.

Major conclusions

It would not be a “leap to” conclusions to suggest that agents which target the ghrelin system – including those that lower acyl-ghrelin levels, raise LEAP2 levels, block GHSR activity, and/or raise desacyl-ghrelin signaling – could represent efficacious novel treatments for obesity and diabetes.

Keywords: Ghrelin, GHSR, LEAP2, GOAT, Obesity, Diabetes

Abbreviations: GH, Growth hormone; GHSR, Growth hormone secretagogue receptor; GOAT, Ghrelin O-acyltransferase; KO, Knockout; LEAP2, Liver-enriched antimicrobial peptide 2; MRAP2, Melanocortin receptor accessory protein-2; PWS, Prader–Willi Syndrome; ZDF, Zucker diabetic fatty

Highlights

-

•

We review the potential of targeting the ghrelin system to treat obesity and diabetes.

-

•

The main components of the ghrelin system are introduced.

-

•

We present data for and against roles of the ghrelin system in obesity and diabetes.

-

•

We discuss factors that might influence the efficacy of this class of therapeutics.

1. Introduction to the ghrelin system

This review focuses on the potential for targeting ghrelin and other proteins comprising the ghrelin system as a new treatment for obesity and diabetes. The ghrelin system encompasses several key components, including ghrelin, growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR; ghrelin receptor), ghrelin-O-acyltransferase (GOAT), liver-enriched antimicrobial peptide 2 (LEAP2), and melanocortin receptor accessory protein-2 (MRAP2) (Figure 1). Ghrelin is a hormone which, in adults, is produced mainly by a distinct population of gastric enteroendocrine ghrelin cells [1,2]. Ghrelin helps the body respond to changes in metabolic state by engaging GHSR-expressing neurons and GHSR-expressing peripheral cells that regulate food intake, body weight, and blood glucose [1,[3], [4], [5]]. Ghrelin also potentiates growth hormone (GH) release, stimulates gastrointestinal motility, induces gastric acid release, and has anti-depressant-like properties, among other effects [3]. In both humans and rodents, plasma ghrelin increases upon fasting and declines in obese states [3,[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]]. Plasma ghrelin levels are also dynamically influenced by feeding status, with levels rising pre-prandially and falling after the consumption of a meal [11,12]. While ghrelin is found in circulation as both acyl-ghrelin and desacyl-ghrelin, only acyl-ghrelin, which receives its unique post-translational acylation via interaction with the enzyme GOAT, binds GHSRs with high affinity [13,14]. Some studies have shown that desacyl-ghrelin also possesses biological activity, which presumably is GHSR-independent, including the ability to reduce food intake and/or block the orexigenic effect of acyl-ghrelin [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. GHSRs not only mediate the metabolic actions of acyl-ghrelin (which will be referred to as “ghrelin” for the remainder of the review), but also impact the activity of other G-protein coupled receptors with which it forms heterodimers, including melanocortin 3 receptor (MC3R), dopamine 1 receptor (D1R), and dopamine 2 receptor (D2R) [[23], [24], [25], [26]].

Figure 1.

Major components of the ghrelin system and classes of therapeutic agents that could potentially be used to treat obesity and diabetes. The hormone ghrelin acts by binding to its receptor GHSR. To do so, it must first be post-translationally modified by the addition of an acyl-group (most often, an octanoyl group), which is catalyzed by the enzyme GOAT. MRAP2 binds intracellularly to GHSR, and in so doing, facilitates ghrelin's orexigenic actions (and perhaps, others of ghrelin actions) while also inhibiting constitutive (ghrelin-independent) GHSR signaling. The hormone LEAP2 was recently identified as a potent GHSR antagonist (blocking ghrelin action) and inverse agonist (attenuating constitutive GHSR signaling). Compounds shown experimentally to target these different ghrelin system components that could potentially be used as anti-obesity and/or anti-diabetic therapeutic agents include GHSR antagonists, neutralizing anti-ghrelin L-RNA aptamers, cyclized desacyl-ghrelin analogs, GOAT inhibitors, LEAP2, LEAP2-derived analogs, and GHSR inverse agonists.

The hormone LEAP2 is the newest component to be identified as a key member of the ghrelin system [27]. LEAP2, which is highly expressed by the liver and jejunum, serves as a second endogenous ligand for GHSR [27]. Upon binding to GHSR, LEAP2 both blocks ghrelin action and reduces ghrelin-independent GHSR activity, or rather, constitutive GHSR activity [[27], [28], [29]]. As is the case for ghrelin, plasma levels of LEAP2 are highly regulated by body weight and feeding status, albeit in the opposite direction from ghrelin in adult humans and mice in most scenarios studied to date [28].

GHSR activity is also modulated intracellularly by MRAP2. In particular, MRAP2 potentiates ghrelin-dependent GHSR signaling via Gαq-mediated inositol phosphate-3 accumulation, inhibits constitutive GHSR signaling via Gαq, and decreases ghrelin-stimulated β-arrestin recruitment [30,31]. Although MRAP2 regulates other G-protein-coupled receptors than GHSR, we characterize it as a key component of the ghrelin system given its many effects on GHSR signaling and since its expression is required for ghrelin-induced food intake [30,31]. Other components of the ghrelin system include enzymes such as butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) and acyl-protein thioesterase 1 (APT1), which hydrolyze ghrelin to desacyl-ghrelin, ghrelin-reactive immunoglobulins, which may protect ghrelin from degradation, and the truncated transmembrane domain 6- and 7-lacking GHSR1b form of GHSR, which binds and in turn reduces the constitutive activity and cell-surface expression of GHSR [[32], [33], [34], [35]].

2. Data supporting a role for the endogenous ghrelin system in the development of obesity

Soon after the identification of ghrelin as an endogenous ligand for GHSR and a potent growth hormone secretagogue, it was shown that ghrelin administration increases food intake and body weight gain [3,4,7,36]. The administration of ghrelin and/or GHSR agonists also lowers energy expenditure and upregulates gene expression of fat storage-promoting enzymes in white adipose tissue [3,8,37]. Based on the early characterization of those functions, limiting ghrelin action was predicted to reduce food intake, body weight gain, and adiposity [3,4,7,8,12,38,39]. Indeed, neutralization of bioavailable ghrelin and administration of GHSR antagonists or GOAT antagonists to mice fed a high-fat diet lowers body weight and/or food intake [[40], [41], [42], [43]]. Administration of a GOAT antagonist to mice reduces weight gain in response to a diet enriched in medium-chain triglycerides [42]. Pharmacological antagonism of GHSR and chemogenetic inhibition of mediobasal hypothalamic GHSR-expressing neurons blunt fasting-induced rebound food intake in mice [44,45]. The administration of LEAP2 or LEAP2-derived peptide analogs acutely reduces baseline food intake and/or ghrelin-induced food intake in mice [27,29].

Some genetic models targeting the ghrelin system also support a role for an intact ghrelin system for normal eating behaviors and/or body weight responses to chronic high-fat diet exposure [44,[46], [47], [48]]. For example, when male ghrelin-knockout (KO) mice were placed on a high-fat diet early in life, they accumulated 30% less body weight over 20 weeks relative to wild-type controls [46]. Similarly, when female mice lacking GHSR (GHSR-null mice) were placed on a high-fat diet soon after weaning, they showed a robust phenotype relative to their wild-type littermates, such that after 19 weeks, they weighed 13% less and had nearly 50% less fat mass [47]. Male GHSR-null mice weighed 11% less and exhibited a 17% lower fat mass than wild-type littermates following high-fat diet exposure [47]. Female GHSR-null mice also accumulated less body weight than their wild-type littermates when fed regular chow, albeit not to the degree of those fed high-fat diet [47]. Another study demonstrated not only that male ghrelin-KO mice exhibited attenuated body weight gain when placed on a high-fat diet for 12 weeks, but also that following a 13-day caloric restriction period, they exhibited less rebound body weight gain upon resumption of ad libitum food access [48]. Simultaneous genetic deletion of both ghrelin and GHSR lowered body weight in animals fed regular chow [49]. Additionally, selective neuronal deletion of GHSRs was shown to almost completely prevent the development of diet-induced obesity, via upregulating energy expenditure [50].

The effects of ghrelin on food intake are particularly apparent when examining hedonic eating behaviors in preclinical models [44,[51], [52], [53], [54], [55]]. As examples, ghrelin administration increases the rewarding value of palatable foods, such that rodents are motivated to work harder to obtain palatable food rewards [44,55]. In contrast, calorically-restricted GHSR-null mice, similarly restricted wild-type mice given a GHSR antagonist, and chronic psychosocial stress-exposed GHSR-null mice all lack conditioned place preference for high-fat diet food rewards [44,52,56]. Furthermore, administered ghrelin induces cue-potentiated feeding behavior, whereas this feeding behavior is disrupted in mice with blocked GHSR signaling [53,54].

3. Data supporting a role for the endogenous ghrelin system in the development of diabetes

The GH secretagogue MK-677 was first identified as having the capacity to elevate fasting blood glucose in healthy human volunteers prior to the identification of GHSR and ghrelin [57]. In 2001, it was reported for the first time that acute administration of ghrelin increases blood glucose in healthy human volunteers [58]. A series of other studies support these findings, consistently reporting that ghrelin, as delivered by bolus or continuous infusion, increases blood glucose in both lean and obese human participants [22,[59], [60], [61], [62]]. In line with data in humans, both central and peripheral ghrelin administration increase blood glucose in rodents [58,[63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71]].

Ghrelin has many known glucoregulatory actions that likely contribute to its ability to increase blood glucose. For instance, administration of ghrelin reduces insulin sensitivity, restricts insulin secretion, increases circulating cortisol, and stimulates glucagon, somatostatin, and growth hormone secretion [65,68,[72], [73], [74], [75], [76]]. These effects of ghrelin occur, at least in part, via direct interactions with GHSR-expressing neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARC), the caudal brainstem, and GHSR-expressing delta cells within pancreatic islets [[75], [76], [77], [78]]. Perhaps counterintuitively, ghrelin also increases circulating concentrations of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), although presumably this serves to attenuate the overall effect that ghrelin has on blood glucose [72,79,80].

In contrast, chronic pharmacological blockade of GHSRs and genetic ablation of other ghrelin system components that normally engage GHSR signaling improve glucose tolerance and/or insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese mice [46,49,[81], [82], [83], [84]]. An intact ghrelin system is also required to prevent the development of life-threatening hypoglycemia in a mouse starvation model. More specifically, ghrelin-KO mice exhibit a progressive decline in fasting blood glucose to the point of near-death following a week-long caloric restriction regimen that provides 40% of usual daily calories and depletes body fat to <2% [85]. Hypoglycemia under this regimen also occurs in mice with ablated ghrelin cells, GOAT-KO mice, GHSR-null mice, mice with ghrelin cell-selective deletion of β1-adrenergic receptors (which exhibit impaired ghrelin secretion), mice carrying a GHSR mutation (A203E) that ablates its constitutive activity, mice overexpressing LEAP2, and mice with hepatocyte-selective GH receptor deletion [9,27,77,83,[86], [87], [88]]. Under the severe caloric restriction regimen, ghrelin release is stimulated in wild-type mice, which in turn induces GH release, followed by activation of hepatocyte GH receptors, stimulation of autophagy in the liver, and then enhanced gluconeogenesis [88,89]. Additionally, both GHSR-KO and ghrelin-KO mice require a higher glucose infusion rate during hyperinsulinemic-hypoglycemic clamps to maintain hypoglycemia [[90], [91], [92]]. Conversely, GHSR agonist administration reduces the glucose infusion rate required by ghrelin-KO mice during the hypoglycemic clamps, potentially via its actions to increase plasma corticosterone and plasma GH [91].

The literature also contains numerous reports linking the ghrelin system to hyperglycemia in models of diabetes [73]. For instance, ghrelin deletion attenuates hyperglycemia in leptin-deficient (ob/ob) mice, which are normally hyperphagic, obese, and diabetic [93] despite the obese phenotype of leptin deficiency remaining unaltered in the ob/ob mice with a ghrelin-KO background [93]. Furthermore, the administration of a GHSR inverse agonist improves glucose tolerance in Zucker diabetic fatty rats (ZDF; fa/fa; leptin-receptor deficient) [84]. In contrast to ob/ob mice, leptin receptor-deficient (db/db) mice, and ZDF rats, all of which exhibit relatively low plasma ghrelin levels [94], humans with maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 3 (MODY-3), and a MODY-3 mouse model [hepatocyte nuclear factor 1-alpha (HNF1α)-deficiency] exhibit elevated plasma ghrelin [95,96]. Notably, GHSR antagonist administration normalizes blood glucose in the otherwise hyperglycemic mice modeling MODY-3 [95]. Ghrelin is also higher in humans with the MODY-2 (glucokinase–MODY) form of diabetes mellitus [96].

The streptozotocin (STZ) model of type 1 diabetes, in which STZ administration to rats and mice chemically ablates pancreatic β-cells, resulting in hyperglycemia as well as hyperphagia, is also associated with alterations in plasma ghrelin. Several studies demonstrate elevated plasma ghrelin in STZ-treated animals [92,[97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103]]. Of particular interest, genetic ablation of ghrelin and pharmacological inhibition of GHSR cause significant reductions in STZ-associated hyperphagia [10,[101], [102], [103], [104]]. Genetic ablation of GHSR or genetic ablation of ghrelin also lowers fasting blood glucose in STZ-treated mice [10,92]. Furthermore, without ghrelin, STZ-treated mice are unable to mount the usual counterregulatory response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia [92].

4. Data that do not necessarily support a role for the endogenous ghrelin system in the development of obesity and diabetes

Although there are many examples of administered ghrelin and endogenously high ghrelin increasing food intake, food reward behaviors, adiposity, body weight, and blood glucose as well as numerous examples of pharmacologic and genetic manipulations that decrease ghrelin levels or ghrelin/GHSR signaling attenuating the development of obesity and lowering blood glucose, the literature does not universally support a role for the endogenous ghrelin system in the development of obesity and diabetes. Indeed, some studies have shown little to no effect of genetic or pharmacologic interference with ghrelin signaling on body weight and food intake [105,106]. For example, initial experiments of ghrelin-KO and GHSR-KO mice reported an insignificant effect of ghrelin deletion on body weight, cumulative food intake, and compensatory hyperphagia following a fast and only a modest reduction in body weight for GHSR-KO mice fed regular chow relative to wild-type controls [107,108]. In a different ghrelin-KO model, mice were resistant to diet-induced obesity only when introduced to high-fat diet soon after weaning, but not when challenged with high-fat diet exposure later in life [46,109]. The initial reports of GOAT-KO mice demonstrated either insignificant or only modest effects on body weight [83,110]. Additionally, ablation of ghrelin cells from adult mice had no effects on either food intake or body weight in mice fed regular chow or high-fat diet [86]. Moreover, while genetic deletion of ghrelin from ob/ob mice resulted in marked improvement in the hyperglycemia characteristic of leptin-deficiency, genetic deletion of GHSR from ob/ob mice paradoxically had the opposite effect – namely, it worsened the hyperglycemia of the ob/ob mice [111].

Typically, plasma ghrelin levels are lower in individuals with obesity than in lean individuals. With some exceptions, plasma ghrelin is consistently reported as being inversely correlated with body weight. This correlation has been found in both adult humans with obesity or metabolic syndrome and in mouse models of diet-induced obesity [28,[112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118], [119]]. In diet-induced obese mice, fasting fails to increase plasma ghrelin [120], whereas in humans with obesity, plasma ghrelin levels are not suppressed after consumption of a meal [121]. Furthermore, plasma levels of the GHSR antagonist and inverse agonist LEAP2 are higher in diet-induced obese mice and adult humans with obesity as compared to lean controls [28]. In particular, plasma LEAP2 is positively correlated with body mass index, percentage body fat, plasma glucose, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), serum triglycerides, visceral adipose tissue volume, visceral adipose tissue volume to subcutaneous adipose tissue volume ratio, and intrahepatocellular lipid content in humans and with fat mass and body weight in mice [28]. These findings translate to an increase in the mean plasma LEAP2/ghrelin molar ratio in subjects with obesity when compared with lean subjects [28]. If ghrelin were a major driver of obesity and the glucose intolerance associated with obesity, one might predict that plasma ghrelin would be increased and plasma LEAP2 decreased relative to levels in lean control subjects as opposed to the reverse.

Not only is plasma ghrelin lower and LEAP2 higher in obese states, but ghrelin transport across the blood–brain barrier is also impaired in obese mice [115,122,123]. These findings lead to the hypothesis that the hypothalamic circuitry controlling food intake becomes ghrelin-resistant during obesity [35]. As examples of this specific ghrelin resistance, ghrelin fails to acutely induce food intake in diet-induced obese mice and in obese Agouti mice, whether acutely or chronically administered [120,124,125]. Administered ghrelin also fails to reduce energy expenditure in diet-induced obese mice unlike its clear effect to reduce energy expenditure in mice fed regular chow [126]. Ghrelin-induced GH release is also attenuated in human subjects with obesity [127]. Among the pathways proposed to mediate the ghrelin resistance of obesity is the above-described coordinated rise in plasma LEAP2 and fall in plasma ghrelin observed in humans and mice with obesity [28].

Similar to the lower levels of plasma ghrelin observed in obesity, lower levels of plasma ghrelin have been reported in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Often, the plasma ghrelin is negatively correlated with circulating insulin levels and obesity in these participants, suggesting that the higher insulin levels observed in early stages of type 2 diabetes and in obesity may drive reductions in plasma ghrelin [128,129]. As mentioned in the discussion above for obesity, we might have predicted plasma ghrelin to be high in type 2 diabetes if it were driving the hyperglycemia. Further, despite the STZ model of type 1 diabetes mellitus being associated with elevated plasma ghrelin, consistent changes to plasma ghrelin in humans with type 1 diabetes mellitus have not been observed [96,[130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135]].

As another example, Prader–Willi Syndrome (PWS) [[136], [137], [138], [139], [140]], which is characterized by failure-to-thrive, GH deficiency, and hypotonia in early-childhood and unrelenting hunger, hard-to-control food-seeking behaviors, hyperphagia, and obesity in late childhood and adulthood, is associated with high plasma ghrelin – approximately 3- to 4.5-fold higher than in matched control subjects with non-syndromic obesity [116,[141], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148], [149], [150]]. Adults with PWS exhibit blunted or absent postprandial ghrelin reductions, and most studies find positive correlations with plasma ghrelin to the overeating and obesity of PWS [116,[141], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148], [149], [150]]. Thus, for years, PWS has been touted as a prime example of a condition in which high ghrelin may be contributing to hyperphagia and obesity [151]. It has also been proposed that the occurrence of high ghrelin in youngsters with PWS may prime their brain for the eventual occurrence of obesity [143], as is supported by work suggesting a key role for proper expression of ghrelin for normal development of hypothalamic feeding circuits [152]. Yet, impaired prohormone processing, including that of proghrelin, has been reported in PWS, as has detection of both mature ghrelin and unprocessed proghrelin by the standard ghrelin assay kits, suggesting that perhaps the levels of biologically-active, mature ghrelin might actually not be elevated in PWS [153]. Indeed, ghrelin deletion and GHSR deletion have only minimal effects on the metabolic profile of Snord116del mice modeling PWS [154]. Instead, daily administration of a GHSR agonist to Snord116del neonates markedly improves their survival, suggesting that boosting ghrelin/GHSR signaling might be beneficial in the early stages of PWS [154]. Furthermore, others have proposed that a high plasma desacyl-ghrelin to acyl-ghrelin ratio contributes to the failure-to-thrive phenotype in infants with PWS [147,155]. Whether or not increased endogenous plasma desacyl-ghrelin contributes to the failure-to-thrive phenotype in youngsters with PWS, a cyclized desacyl-ghrelin analog (AZP-531) has been shown in a two week-long, proof-of-concept multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 47 adult patients with PWS to significantly improve food-related behaviors and reduce appetite [156]. A short-term course of this desacyl-ghrelin analog also reduced hemoglobin A1c and body weight when tested in a small cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes [157].

5. Is there a role for therapeutic targeting of the ghrelin system to treat obesity and diabetes?

As evidenced in the above discussion, the literature does not draw a straight line from altered ghrelin system functioning to obesity or diabetes. Yet, would it be a leap to conclusions to suggest that therapeutics which lower acyl-ghrelin, raise LEAP2, block GHSR activity, and/or raise desacyl-ghrelin signaling, might be beneficial in obesity or diabetes? Examples of agents with these properties are numerous in the literature and include the following classes depicted in Figure 1: anti-ghrelin L-RNA aptamers (anti-ghrelin vaccine), GHSR antagonists, GHSR inverse agonists, GOAT inhibitors, cyclized desacyl-ghrelin analogs, LEAP2, and LEAP2-derived peptide analogs [29,41,[157], [158], [159]]. Our simple answer is no. Instead, it is our strong opinion that ample preclinical and clinical data exist supporting further research and development in this area. Moreover, as outlined in Figure 2, we believe there are several factors which may influence the efficacy of such agents. These factors are described in more detail below.

Figure 2.

Factors and contexts that might influence the efficacy of ghrelin system-targeted therapeutic agents in treating obesity and diabetes. While the safety and efficacy of compounds which lower acyl-ghrelin, raise LEAP2, block GHSR activity, and/or raise desacyl-ghrelin signaling remain to be fully tested in clinical trials, studies have provided clues as to clinical scenarios that may heighten their anti-obesity and/or anti-diabetic effects or alternatively might result in negative consequences. These factors and contexts and specific scenarios in which therapeutic agents that block ghrelin/GHSR signaling might be particularly beneficial or detrimental are summarized here and discussed further in the text.

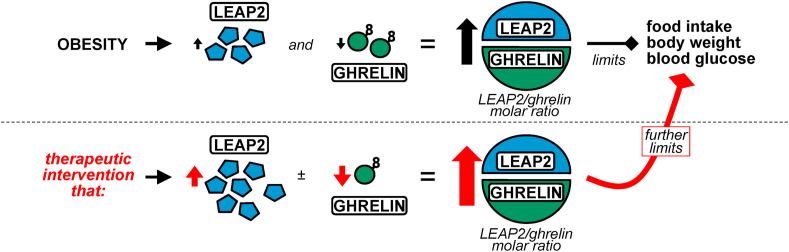

As mentioned, ghrelin levels are low in obesity, and at least some of ghrelin's metabolic actions are blunted in obesity due to a state of ghrelin resistance. Similarly, plasma LEAP2 depends on both the long-term, underlying metabolic state (e.g., body mass and adiposity) as well as more short-term, meal-dependent changes in nutrient availability [28]. These state- and meal-dependent LEAP2 changes are mostly opposite of those of ghrelin. Notably, the concentration of plasma LEAP2 in the ad libitum–fed state is more than 20-fold higher than that of plasma ghrelin in both mice and humans [28]. Also, the potency of LEAP2 as a GHSR antagonist is very close to the potency of ghrelin as a GHSR agonist when assessed in vitro [27,29,160]. Therefore, we have hypothesized that in the fed state, LEAP2 serves as the dominant ligand of GHSR, prominently antagonizing ghrelin actions [28]. In contrast, in the fasted state, the fall in the plasma LEAP2/ghrelin molar ratio seems to favor a relatively higher degree of ghrelin-GHSR binding. This potentially explains why genetic deletion of endogenous ghrelin does not have pronounced metabolic effects in ad libitum–fed conditions, but does upon energy restriction [85]. The same reasoning can be used to predict a dominant role for LEAP2 in the setting of obesity. As indicated in Figure 3, we have proposed that in obese states, LEAP2 rises and ghrelin falls, shifting the plasma LEAP2/ghrelin molar ratio higher so as to limit ghrelin's capacity to exacerbate obesity and glucose intolerance by raising food intake, body weight, and blood glucose. Furthermore, our model predicts that therapeutic interventions that raise plasma LEAP2 or further reduce plasma ghrelin, in an effort to raise the plasma LEAP2/ghrelin molar ratio even higher, would serve to limit the development of obesity and glucose intolerance in obesogenic environments.

Figure 3.

Model illustrating the coordinated response of ghrelin and LEAP2 to obesity and the proposed metabolic effects of a therapeutic intervention that would further raise the plasma LEAP2/ghrelin molar ratio. Top: Obesity is associated with an increase in plasma LEAP2 and a decrease in plasma ghrelin. The resulting increased plasma LEAP2/ghrelin molar ratio serves to limit food intake, body weight, and blood glucose, or rather, processes that would otherwise exacerbate obesity and glucose intolerance. Bottom: Therapeutic interventions that increase plasma LEAP2 and/or decrease plasma ghrelin, such as many of those illustrated in Figure 1, would further increase the plasma LEAP2/ghrelin molar ratio. In turn, food intake, body weight, and blood glucose would be further limited, as would the development of obesity and glucose intolerance in obesogenic environments.

Why might raising LEAP2 be helpful in the setting of obesity? Importantly, plasma LEAP2 is positively correlated with body mass index, and postprandial increases in plasma LEAP2 have been observed only in subjects with body mass indices greater than 35–40 kg/m2 [28]. This suggests that less severe degrees of obesity (e.g., Class I obesity) may not be associated with what is presumed to be compensatory elevations of LEAP2 which would otherwise limit food intake and body weight gains. As such, individuals with less severe obesity might benefit from therapies that would raise plasma LEAP2 (for instance, to curb appetite and reduce food reward). So too might individuals who have achieved weight loss through lifestyle interventions, but who run the risk of rebound weight gain, as weight loss induces decreases in plasma LEAP2 and reciprocal increases in plasma ghrelin [28].

Why might lowering plasma ghrelin even further in obesity be helpful? Several studies have reported an effect of insulin administration to markedly lower plasma ghrelin [91,92,[161], [162], [163]]. However, despite this drop in plasma ghrelin, for instance in wild-type mice subjected to insulin tolerance testing, the remaining ghrelin continues to exert key glucoregulatory effects, as emphasized by the exaggerated hypoglycemia of similarly-treated ghrelin-KO mice [91]. Likewise, despite the observed drops in plasma ghrelin in wild-type mice subjected to hyperinsulinemic-hypoglycemic clamps, the remaining ghrelin retains its key permissive glucoregulatory functions, as highlighted by the requirement for a markedly higher glucose infusion rate in ghrelin-KO mice, the attenuated changes to the traditional counterregulatory hormones corticosterone and GH in ghrelin-KO mice, and their rescue upon administration of GHSR agonist [91]. Thus, even though plasma ghrelin levels start off low in obesity, pushing them even lower might still be beneficial in obesity and diabetes.

The context in which targeting the ghrelin system is used might also be important. For example, exercise has been shown to influence plasma ghrelin in several human trials. While many of these clinical studies and some preclinical studies demonstrated lower plasma ghrelin following exercise [[164], [165], [166], [167], [168], [169], [170], [171], [172]], higher plasma ghrelin has also been observed [[173], [174], [175], [176], [177], [178], [179]], as has unchanged plasma ghrelin [[180], [181], [182]]. Our group showed that in wild-type mice, a short bout of high intensity exercise transiently elevated plasma ghrelin [183]. Furthermore, GHSR-null mice submitted to the same high intensity interval exercise paradigm exhibited markedly reduced food intake following exercise as compared to wild-type mice [183]. These data suggest that an intact ghrelin system is required for the usual food intake response to exercise, that its effects may last several hours post-exercise, and that its loss or blockade may potentially amplify the efficacy of exercise to reduce post-exercise food intake. Thus, perhaps targeting the ghrelin system may be particularly efficacious when done in conjunction with exercise.

Other groups of patients that might particularly benefit from targeting the ghrelin system include post-menopausal women. Indeed, the body weights and body composition of female mice are much more susceptible to the effects of GHSR deletion than males, especially when challenged with high-fat diet [47]. Also, estrogen-dependent changes in both ghrelin levels and ghrelin orexigenic efficacy exist [184]. For example, ovariectomy increases plasma ghrelin. Male and ovariectomized female rats are more sensitive than intact female rats to the orexigenic effects of administered ghrelin. Ghrelin's effects are reduced upon estrogen delivery to male and ovariectomized female rats. Also, ovariectomized GHSR-null mice resist the gains in food intake and body weight normally induced by ovariectomy. Age might also be an important factor. For instance, similar to humans, fasted young mice are susceptible to hypoglycemia upon beta blocker administration, potentially as a result of reducing ghrelin secretion, whereas adult mice are not [9]. Aged mice also appear to be particularly susceptible to ghrelin or GHSR deletion [185,186]. Thus, different age brackets should be investigated to determine if one or the other is more responsive to targeting the ghrelin system. In nearly all studies, ghrelin administration drives hedonic eating, whereas GHSR and GOAT deletion or GHSR antagonism diminish it [[187], [188], [189]]. Accordingly, those individuals whose obesity is driven by food reward behaviors might benefit more from targeting the ghrelin system. It is also certain that specific genetic mutations might enhance performance of ghrelin system-targeting therapies. As described above, some monogenic forms of diabetes, such as MODY-3 and MODY-2, are associated with elevated plasma ghrelin, and a GHSR antagonist reversed hyperglycemia in a preclinical MODY-3 mouse model. Also, ghrelin deletion improved hyperglycemia in leptin-deficient mice. Furthermore, the cyclized desacyl-ghrelin analog shows promise in reducing appetite in patients with PWS.

6. Theoretical downsides to modulating the ghrelin system as a means to treat obesity and diabetes

There are potential drawbacks to pharmacologically reducing GHSR signaling as a means to treat obesity and diabetes. One drawback relates to actions of ghrelin and GHSR to stimulate adult hippocampal neurogenesis, while genetic GHSR deletion reduces adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the settings of chronic social defeat stress (a model of chronic psychosocial stress) and caloric restriction [[190], [191], [192]]. Such reductions in adult hippocampal neurogenesis have been linked to exaggerated depressive-like behavior and deficiencies in learning and memory and may be particularly relevant in neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease [[190], [191], [192]]. Consequently, individuals with diabetes or obesity suffering from depression or a neurodegenerative disorder may not be optimal candidates for therapeutic interventions that would decrease ghrelin/GHSR signaling. Also, ghrelin possesses gastroprokinetic activity, leading to the investigation of GHSR agonists as a potential treatment for diabetic gastroparesis [193]. As a result, diabetic individuals complicated by gastroparesis may not be the best candidates for treatment with a GHSR antagonist.

Another theoretical drawback to blocking ghrelin/GHSR signaling relates to the proposed function of ghrelin as a survival hormone [4]. In particular, we and others have hypothesized that the endogenous ghrelin system serves an essential function during extreme nutritional and psychological challenges to defend blood glucose, protect body weight, and ultimately allow survival [4]. Highlighting these protective actions of ghrelin, ghrelin-KO mice and related genetic models that decrease ghrelin/GHSR signaling experience marked hypoglycemia and increased mortality upon exposure to a prolonged caloric restriction regimen that depletes body fat to <2%, as mentioned above [9,27,77,[85], [86], [87], [88], [89]]. Ghrelin prevents hypoglycemia from occurring in fasted, beta blocker-treated 3-week-old mice, modeling the hypoglycemia occasionally experienced by beta blocker-treated human infants and toddlers when they have not been eating [9]. During hyperinsulinemic-hypoglycemic clamp procedures, ghrelin-KO and GHSR-KO mice require greater glucose infusion rates to prevent blood glucose levels from falling beneath the target range [[90], [91], [92]]. GHSR-null mice exhibit reduced exercise tolerance when run on treadmills [183]. Also, pharmacological antagonism of GHSR and GHSR-deletion worsen anorexia/cachexia and accelerate death in tumor-bearing rodents [194,195]. Given these findings, activating the ghrelin system could be a viable pharmacological approach to promote food intake and defend against hypoglycemia, body weight loss, poor exercise endurance, and death during extreme nutritional challenges including severe caloric restriction and cachexia [4,183]. In contrast, it likely would be appropriate to avoid treatment with agents that reduce ghrelin/GHSR signaling in the presence of anorexia/cachexia syndromes, such as those associated with cancer, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [4]. It also might be prudent to avoid the use of drugs that reduce ghrelin/GHSR signaling in diabetic patients susceptible to insulin-induced hypoglycemia.

7. Conclusions

We believe that ample data support further research and development of classes of drugs that act to lower plasma ghrelin, raise plasma LEAP2, block GHSR activity, and/or raise desacyl-ghrelin signaling as a means of treating obesity and diabetes. While the literature suggests certain scenarios in which these compounds may have negative consequences, the literature also highlights scenarios and contexts in which these compounds may be particularly beneficial as novel treatments for obesity and diabetes.

Author contributions

Deepali Gupta: writing – review and editing. Sean Ogden: visualization, writing – review and editing. Kripa Shankar: writing – review and editing. Salil Varshney: writing – review and editing. Jeffrey Zigman: conceptualization, visualization, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review and editing, funding acquisition.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Sherri Osborne–Lawrence for supporting all aspects of the lab's research over the years and Nathan Metzger for his efforts in support of our animal colony. Dr. Zigman acknowledges the lab's past students, postdoctoral researchers, and technicians for their inspiration and dedication to the research that has helped form the basis for the concepts outlined in this review. We also acknowledge the generous support from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK119341-01A1, 2 R01 DK103884-05, and P01 DK119130-01A1).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Kojima M., Hosoda H., Date Y., Nakazato M., Matsuo H., Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402(6762):656–660. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakata I., Nakano Y., Osborne-Lawrence S., Rovinsky S.A., Lee C.E., Perello M. Characterization of a novel ghrelin cell reporter mouse. Regulatory Peptides. 2009;155(1–3):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller T.D., Nogueiras R., Andermann M.L., Andrews Z.B., Anker S.D., Argente J. Ghrelin Molecular Metabolism. 2015;4(6):437–460. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mani B.K., Zigman J.M. Ghrelin as a survival hormone. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2017;28(12):843–854. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zigman J.M., Jones J.E., Lee C.E., Saper C.B., Elmquist J.K. Expression of ghrelin receptor mRNA in the rat and the mouse brain. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2006;494(3):528–548. doi: 10.1002/cne.20823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ariyasu H., Takaya K., Tagami T., Ogawa Y., Hosoda K., Akamizu T. Stomach is a major source of circulating ghrelin, and feeding state determines plasma ghrelin-like immunoreactivity levels in humans. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86(10):4753–4758. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tschop M., Smiley D.L., Heiman M.L. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature. 2000;407(6806):908–913. doi: 10.1038/35038090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asakawa A., Inui A., Kaga T., Yuzuriha H., Nagata T., Ueno N. Ghrelin is an appetite-stimulatory signal from stomach with structural resemblance to motilin. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(2):337–345. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mani B.K., Osborne-Lawrence S., Vijayaraghavan P., Hepler C., Zigman J.M. beta1-Adrenergic receptor deficiency in ghrelin-expressing cells causes hypoglycemia in susceptible individuals. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2016;126(9):3467–3478. doi: 10.1172/JCI86270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mani B.K., Uchida A., Lee Y., Osborne-Lawrence S., Charron M.J., Unger R.H. Hypoglycemic effect of combined ghrelin and glucagon receptor blockade. Diabetes. 2017;66(7):1847–1857. doi: 10.2337/db16-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J., Prudom C.E., Nass R., Pezzoli S.S., Oliveri M.C., Johnson M.L. Novel ghrelin assays provide evidence for independent regulation of ghrelin acylation and secretion in healthy young men. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;93(5):1980–1987. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings D.E., Purnell J.Q., Frayo R.S., Schmidova K., Wisse B.E., Weigle D.S. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes. 2001;50(8):1714–1719. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J., Brown M.S., Liang G., Grishin N.V., Goldstein J.L. Identification of the acyltransferase that octanoylates ghrelin, an appetite-stimulating peptide hormone. Cell. 2008;132(3):387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutierrez J.A., Solenberg P.J., Perkins D.R., Willency J.A., Knierman M.D., Jin Z. Ghrelin octanoylation mediated by an orphan lipid transferase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(17):6320–6325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800708105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inhoff T., Wiedenmann B., Klapp B.F., Monnikes H., Kobelt P. Is desacyl ghrelin a modulator of food intake? Peptides. 2009;30(5):991–994. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delhanty P.J., Neggers S.J., van der Lely A.J. Des-acyl ghrelin: a metabolically active peptide. Endocrine Development. 2013;25:112–121. doi: 10.1159/000346059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asakawa A., Inui A., Fujimiya M., Sakamaki R., Shinfuku N., Ueta Y. Stomach regulates energy balance via acylated ghrelin and desacyl ghrelin. Gut. 2005;54(1):18–24. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.038737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen C.Y., Inui A., Asakawa A., Fujino K., Kato I., Chen C.C. Des-acyl ghrelin acts by CRF type 2 receptors to disrupt fasted stomach motility in conscious rats. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):8–25. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuda K., Miura T., Kaiya H., Maruyama K., Shimakura S., Uchiyama M. Regulation of food intake by acyl and des-acyl ghrelins in the goldfish. Peptides. 2006;27(9):2321–2325. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inhoff T., Monnikes H., Noetzel S., Stengel A., Goebel M., Dinh Q.T. Desacyl ghrelin inhibits the orexigenic effect of peripherally injected ghrelin in rats. Peptides. 2008;29(12):2159–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toshinai K., Yamaguchi H., Sun Y., Smith R.G., Yamanaka A., Sakurai T. Des-acyl ghrelin induces food intake by a mechanism independent of the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Endocrinology. 2006;147(5):2306–2314. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broglio F., Gottero C., Prodam F., Gauna C., Muccioli G., Papotti M. Non-acylated ghrelin counteracts the metabolic but not the neuroendocrine response to acylated ghrelin in humans. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;89(6):3062–3065. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kern A., Albarran-Zeckler R., Walsh H.E., Smith R.G. Apo-ghrelin receptor forms heteromers with DRD2 in hypothalamic neurons and is essential for anorexigenic effects of DRD2 agonism. Neuron. 2012;73(2):317–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rediger A., Piechowski C.L., Yi C.X., Tarnow P., Strotmann R., Gruters A. Mutually opposite signal modulation by hypothalamic heterodimerization of ghrelin and melanocortin-3 receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(45):39623–39631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.287607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schellekens H., van Oeffelen W.E., Dinan T.G., Cryan J.F. Promiscuous dimerization of the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHS-R1a) attenuates ghrelin-mediated signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288(1):181–191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.382473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tian J., Guo L., Sui S., Driskill C., Phensy A., Wang Q. Disrupted hippocampal growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1alpha interaction with dopamine receptor D1 plays a role in Alzheimer's disease. Science Translational Medicine. 2019;11(505) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav6278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ge X., Yang H., Bednarek M.A., Galon-Tilleman H., Chen P., Chen M. LEAP2 is an endogenous antagonist of the ghrelin receptor. Cell Metabolism. 2018;27(2):461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.10.016. e466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mani B.K., Puzziferri N., He Z., Rodriguez J.A., Osborne-Lawrence S., Metzger N.P. LEAP2 changes with body mass and food intake in humans and mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2019;129(9):3909–3923. doi: 10.1172/JCI125332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.M'Kadmi C., Cabral A., Barrile F., Giribaldi J., Cantel S., Damian M. N-terminal liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2 (LEAP2) region exhibits inverse agonist activity toward the ghrelin receptor. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2019;62(2):965–973. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srisai D., Yin T.C., Lee A.A., Rouault A.A.J., Pearson N.A., Grobe J.L. MRAP2 regulates ghrelin receptor signaling and hunger sensing. Nature Communications. 2017;8(1):713. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00747-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouault A.A.J., Rosselli-Murai L.K., Hernandez C.C., Gimenez L.E., Tall G.G., Sebag J.A. The GPCR accessory protein MRAP2 regulates both biased signaling and constitutive activity of the ghrelin receptor GHSR1a. Science Signaling. 2020;13(613) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aax4569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edwards A., Abizaid A. Clarifying the ghrelin system's ability to regulate feeding behaviours despite enigmatic spatial separation of the GHSR and its endogenous ligand. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(4) doi: 10.3390/ijms18040859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen V.P., Gao Y., Geng L., Brimijoin S. Butyrylcholinesterase regulates central ghrelin signaling and has an impact on food intake and glucose homeostasis. International Journal of Obesity. 2017;41(9):1413–1419. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fetissov S.O., Lucas N., Legrand R. Ghrelin-reactive immunoglobulins in conditions of altered appetite and energy balance. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2017;8:10. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Satou M., Nishi Y., Yoh J., Hattori Y., Sugimoto H. Identification and characterization of acyl-protein thioesterase 1/lysophospholipase I as a ghrelin deacylation/lysophospholipid hydrolyzing enzyme in fetal bovine serum and conditioned medium. Endocrinology. 2010;151(10):4765–4775. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Briggs D.I., Andrews Z.B. Metabolic status regulates ghrelin function on energy homeostasis. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;93(1):48–57. doi: 10.1159/000322589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Theander-Carrillo C., Wiedmer P., Cettour-Rose P., Nogueiras R., Perez-Tilve D., Pfluger P. Ghrelin action in the brain controls adipocyte metabolism. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(7):1983–1993. doi: 10.1172/JCI25811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wren A.M., Small C.J., Abbott C.R., Dhillo W.S., Seal L.J., Cohen M.A. Ghrelin causes hyperphagia and obesity in rats. Diabetes. 2001;50(11):2540–2547. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamegai J., Tamura H., Shimizu T., Ishii S., Sugihara H., Wakabayashi I. Chronic central infusion of ghrelin increases hypothalamic neuropeptide Y and Agouti-related protein mRNA levels and body weight in rats. Diabetes. 2001;50(11):2438–2443. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shearman L.P., Wang S.P., Helmling S., Stribling D.S., Mazur P., Ge L. Ghrelin neutralization by a ribonucleic acid-SPM ameliorates obesity in diet-induced obese mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147(3):1517–1526. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zorrilla E.P., Iwasaki S., Moss J.A., Chang J., Otsuji J., Inoue K. Vaccination against weight gain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(35):13226–13231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605376103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barnett B.P., Hwang Y., Taylor M.S., Kirchner H., Pfluger P.T., Bernard V. Glucose and weight control in mice with a designed ghrelin O-acyltransferase inhibitor. Science. 2010;330(6011):1689–1692. doi: 10.1126/science.1196154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esler W.P., Rudolph J., Claus T.H., Tang W., Barucci N., Brown S.E. Small-molecule ghrelin receptor antagonists improve glucose tolerance, suppress appetite, and promote weight loss. Endocrinology. 2007;148(11):5175–5185. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perello M., Sakata I., Birnbaum S., Chuang J.C., Osborne-Lawrence S., Rovinsky S.A. Ghrelin increases the rewarding value of high-fat diet in an orexin-dependent manner. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(9):880–886. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mani B.K., Osborne-Lawrence S., Mequinion M., Lawrence S., Gautron L., Andrews Z.B. The role of ghrelin-responsive mediobasal hypothalamic neurons in mediating feeding responses to fasting. Molecular Metabolism. 2017;6(8):882–896. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wortley K.E., del Rincon J.P., Murray J.D., Garcia K., Iida K., Thorner M.O. Absence of ghrelin protects against early-onset obesity. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115(12):3573–3578. doi: 10.1172/JCI26003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zigman J.M., Nakano Y., Coppari R., Balthasar N., Marcus J.N., Lee C.E. Mice lacking ghrelin receptors resist the development of diet-induced obesity. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115(12):3564–3572. doi: 10.1172/JCI26002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Briggs D.I., Lockie S.H., Wu Q., Lemus M.B., Stark R., Andrews Z.B. Calorie-restricted weight loss reverses high-fat diet-induced ghrelin resistance, which contributes to rebound weight gain in a ghrelin-dependent manner. Endocrinology. 2013;154(2):709–717. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pfluger P.T., Kirchner H., Gunnel S., Schrott B., Perez-Tilve D., Fu S. Simultaneous deletion of ghrelin and its receptor increases motor activity and energy expenditure. American Journal of Physiology - Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2008;294(3):G610–G618. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00321.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee J.H., Lin L., Xu P., Saito K., Wei Q., Meadows A.G. Neuronal deletion of ghrelin receptor almost completely prevents diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2016;65(8):2169–2178. doi: 10.2337/db15-1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uchida A., Zigman J.M., Perello M. Ghrelin and eating behavior: evidence and insights from genetically-modified mouse models. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2013;7:121. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Egecioglu E., Jerlhag E., Salome N., Skibicka K.P., Haage D., Bohlooly Y.M. Ghrelin increases intake of rewarding food in rodents. Addiction Biology. 2010;15(3):304–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walker A.K., Ibia I.E., Zigman J.M. Disruption of cue-potentiated feeding in mice with blocked ghrelin signaling. Physiology & Behavior. 2012;108:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanoski S.E., Fortin S.M., Ricks K.M., Grill H.J. Ghrelin signaling in the ventral hippocampus stimulates learned and motivational aspects of feeding via PI3K-Akt signaling. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;73(9):915–923. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Disse E., Bussier A.L., Deblon N., Pfluger P.T., Tschop M.H., Laville M. Systemic ghrelin and reward: effect of cholinergic blockade. Physiology & Behavior. 2011;102(5):481–484. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chuang J.C., Perello M., Sakata I., Osborne-Lawrence S., Savitt J.M., Lutter M. Ghrelin mediates stress-induced food-reward behavior in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(7):2684–2692. doi: 10.1172/JCI57660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chapman I.M., Bach M.A., Van Cauter E., Farmer M., Krupa D., Taylor A.M. Stimulation of the growth hormone (GH)-insulin-like growth factor I axis by daily oral administration of a GH secretogogue (MK-677) in healthy elderly subjects. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1996;81(12):4249–4257. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.12.8954023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Broglio F., Arvat E., Benso A., Gottero C., Muccioli G., Papotti M. Ghrelin, a natural GH secretagogue produced by the stomach, induces hyperglycemia and reduces insulin secretion in humans. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86(10):5083–5086. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.8098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vestergaard E.T., Moller N., Jorgensen J.O. Acute peripheral tissue effects of ghrelin on interstitial levels of glucose, glycerol, and lactate: a microdialysis study in healthy human subjects. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;304(12):E1273–E1280. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00662.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tassone F., Broglio F., Destefanis S., Rovere S., Benso A., Gottero C. Neuroendocrine and metabolic effects of acute ghrelin administration in human obesity. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88(11):5478–5483. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guido M., Romualdi D., De Marinis L., Porcelli T., Giuliani M., Costantini B. Administration of exogenous ghrelin in obese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: effects on plasma levels of growth hormone, glucose, and insulin. Fertility and Sterility. 2007;88(1):125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fusco A., Bianchi A., Mancini A., Milardi D., Giampietro A., Cimino V. Effects of ghrelin administration on endocrine and metabolic parameters in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2007;30(11):948–956. doi: 10.1007/BF03349243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sim Y.B., Park S.H., Kim S.S., Kim C.H., Kim S.J., Lim S.M. Ghrelin administered spinally increases the blood glucose level in mice. Peptides. 2014;54:162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nieminen P., Mustonen A.M. Effects of peripheral ghrelin on the carbohydrate and lipid metabolism of the tundra vole (Microtus oeconomus) General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2004;138(2):182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heppner K.M., Tong J. Mechanisms in endocrinology: regulation of glucose metabolism by the ghrelin system: multiple players and multiple actions. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2014;171(1):R21–R32. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dezaki K., Hosoda H., Kakei M., Hashiguchi S., Watanabe M., Kangawa K. Endogenous ghrelin in pancreatic islets restricts insulin release by attenuating Ca2+ signaling in beta-cells: implication in the glycemic control in rodents. Diabetes. 2004;53(12):3142–3151. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dezaki K., Kakei M., Yada T. Ghrelin uses Galphai2 and activates voltage-dependent K+ channels to attenuate glucose-induced Ca2+ signaling and insulin release in islet beta-cells: novel signal transduction of ghrelin. Diabetes. 2007;56(9):2319–2327. doi: 10.2337/db07-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chuang J.C., Sakata I., Kohno D., Perello M., Osborne-Lawrence S., Repa J.J. Ghrelin directly stimulates glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha-cells. Molecular Endocrinology. 2011;25(9):1600–1611. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reed J.A., Benoit S.C., Pfluger P.T., Tschop M.H., D'Alessio D.A., Seeley R.J. Mice with chronically increased circulating ghrelin develop age-related glucose intolerance. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;294(4):E752–E760. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00463.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Colombo M., Gregersen S., Xiao J., Hermansen K. Effects of ghrelin and other neuropeptides (CART, MCH, orexin A and B, and GLP-1) on the release of insulin from isolated rat islets. Pancreas. 2003;27(2):161–166. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200308000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tong J., Prigeon R.L., Davis H.W., Bidlingmaier M., Kahn S.E., Cummings D.E. Ghrelin suppresses glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and deteriorates glucose tolerance in healthy humans. Diabetes. 2010;59(9):2145–2151. doi: 10.2337/db10-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gray S.M., Page L.C., Tong J. Ghrelin regulation of glucose metabolism. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2019;31(7) doi: 10.1111/jne.12705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mani B.K., Shankar K., Zigman J.M. Ghrelin's relationship to blood glucose. Endocrinology. 2019;160(5):1247–1261. doi: 10.1210/en.2019-00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mani B.K., Zigman J.M. A strong stomach for somatostatin. Endocrinology. 2015;156(11):3876–3879. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DiGruccio M.R., Mawla A.M., Donaldson C.J., Noguchi G.M., Vaughan J., Cowing-Zitron C. Comprehensive alpha, beta and delta cell transcriptomes reveal that ghrelin selectively activates delta cells and promotes somatostatin release from pancreatic islets. Molecular Metabolism. 2016;5(7):449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adriaenssens A.E., Svendsen B., Lam B.Y., Yeo G.S., Holst J.J., Reimann F. Transcriptomic profiling of pancreatic alpha, beta and delta cell populations identifies delta cells as a principal target for ghrelin in mouse islets. Diabetologia. 2016;59(10):2156–2165. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4033-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Q., Liu C., Uchida A., Chuang J.C., Walker A., Liu T. Arcuate AgRP neurons mediate orexigenic and glucoregulatory actions of ghrelin. Molecular Metabolism. 2014;3(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Scott M.M., Perello M., Chuang J.C., Sakata I., Gautron L., Lee C.E. Hindbrain ghrelin receptor signaling is sufficient to maintain fasting glucose. PloS One. 2012;7(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Page L.C., Gastaldelli A., Gray S.M., D'Alessio D.A., Tong J. Interaction of GLP-1 and ghrelin on glucose tolerance in healthy humans. Diabetes. 2018;67(10):1976–1985. doi: 10.2337/db18-0451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tong J., Davis H.W., Gastaldelli A., D'Alessio D. Ghrelin impairs prandial glucose tolerance and insulin secretion in healthy humans despite increasing GLP-1. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2016;101(6):2405–2414. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dezaki K., Sone H., Koizumi M., Nakata M., Kakei M., Nagai H. Blockade of pancreatic islet-derived ghrelin enhances insulin secretion to prevent high-fat diet-induced glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 2006;55(12):3486–3493. doi: 10.2337/db06-0878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Longo K.A., Charoenthongtrakul S., Giuliana D.J., Govek E.K., McDonagh T., Qi Y. Improved insulin sensitivity and metabolic flexibility in ghrelin receptor knockout mice. Regulatory Peptides. 2008;150(1–3):55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao T.J., Liang G., Li R.L., Xie X., Sleeman M.W., Murphy A.J. Ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT) is essential for growth hormone-mediated survival of calorie-restricted mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(16):7467–7472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002271107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Abegg K., Bernasconi L., Hutter M., Whiting L., Pietra C., Giuliano C. Ghrelin receptor inverse agonists as a novel therapeutic approach against obesity-related metabolic disease. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2017;19(12):1740–1750. doi: 10.1111/dom.13020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li R.L., Sherbet D.P., Elsbernd B.L., Goldstein J.L., Brown M.S., Zhao T.J. Profound hypoglycemia in starved, ghrelin-deficient mice is caused by decreased gluconeogenesis and reversed by lactate or fatty acids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287(22):17942–17950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.358051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McFarlane M.R., Brown M.S., Goldstein J.L., Zhao T.J. Induced ablation of ghrelin cells in adult mice does not decrease food intake, body weight, or response to high-fat diet. Cell Metabolism. 2014;20(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Torz L.J., Osborne-Lawrence S., Rodriguez J., He Z., Cornejo M.P., Mustafa E.R. Metabolic insights from a GHSR-A203E mutant mouse model. Molecular Metabolism. 2020;39:101004. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fang F., Shi X., Brown M.S., Goldstein J.L., Liang G. Growth hormone acts on liver to stimulate autophagy, support glucose production, and preserve blood glucose in chronically starved mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2019;116(15):7449–7454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901867116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang Y., Fang F., Goldstein J.L., Brown M.S., Zhao T.J. Reduced autophagy in livers of fasted, fat-depleted, ghrelin-deficient mice: reversal by growth hormone. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(4):1226–1231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423643112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lin L., Saha P.K., Ma X., Henshaw I.O., Shao L., Chang B.H. Ablation of ghrelin receptor reduces adiposity and improves insulin sensitivity during aging by regulating fat metabolism in white and brown adipose tissues. Aging Cell. 2011;10(6):996–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00740.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shankar K., Gupta D., Mani B.K., Findley B.G., Lord C.C., Osborne-Lawrence S. Acyl-ghrelin is permissive for the normal counterregulatory response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Diabetes. 2020;69(2):228–237. doi: 10.2337/db19-0438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shankar K., Gupta D., Mani B.K., Findley B.G., Osborne-Lawrence S., Metzger N.P. Ghrelin protects against insulin-induced hypoglycemia in a mouse model of Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sun Y., Asnicar M., Saha P.K., Chan L., Smith R.G. Ablation of ghrelin improves the diabetic but not obese phenotype of ob/ob mice. Cell Metabolism. 2006;3(5):379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ariyasu H., Takaya K., Hosoda H., Iwakura H., Ebihara K., Mori K. Delayed short-term secretory regulation of ghrelin in obese animals: evidenced by a specific RIA for the active form of ghrelin. Endocrinology. 2002;143(9):3341–3350. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brial F., Lussier C.R., Belleville K., Sarret P., Boudreau F. Ghrelin inhibition restores glucose homeostasis in hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha (MODY3)-Deficient mice. Diabetes. 2015;64(9):3314–3320. doi: 10.2337/db15-0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nowak N., Hohendorff J., Solecka I., Szopa M., Skupien J., Kiec-Wilk B. Circulating ghrelin level is higher in HNF1A-MODY and GCK-MODY than in polygenic forms of diabetes mellitus. Endocrine. 2015;50(3):643–649. doi: 10.1007/s12020-015-0627-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Verhulst P.J., De Smet B., Saels I., Thijs T., Ver Donck L., Moechars D. Role of ghrelin in the relationship between hyperphagia and accelerated gastric emptying in diabetic mice. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(4):1267–1276. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ariga H., Imai K., Chen C., Mantyh C., Pappas T.N., Takahashi T. Does ghrelin explain accelerated gastric emptying in the early stages of diabetes mellitus? American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2008;294(6):R1807–R1812. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00785.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dong J., Peeters T.L., De Smet B., Moechars D., Delporte C., Vanden Berghe P. Role of endogenous ghrelin in the hyperphagia of mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Endocrinology. 2006 doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tsubone T., Masaki T., Katsuragi I., Tanaka K., Kakuma T., Yoshimatsu H. Leptin downregulates ghrelin levels in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2005;289(6):R1703–R1706. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00773.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ishii S., Kamegai J., Tamura H., Shimizu T., Sugihara H., Oikawa S. Role of ghrelin in streptozotocin-induced diabetic hyperphagia. Endocrinology. 2002;143(12):4934–4937. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gelling R.W., Overduin J., Morrison C.D., Morton G.J., Frayo R.S., Cummings D.E. Effect of uncontrolled diabetes on plasma ghrelin concentrations and ghrelin-induced feeding. Endocrinology. 2004;145(10):4575–4582. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Masaoka T., Suzuki H., Hosoda H., Ota T., Minegishi Y., Nagata H. Enhanced plasma ghrelin levels in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. FEBS Letters. 2003;541(1–3):64–68. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dong J., Peeters T.L., De Smet B., Moechars D., Delporte C., Vanden Berghe P. Role of endogenous ghrelin in the hyperphagia of mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Endocrinology. 2006;147(6):2634–2642. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sun Y., Butte N.F., Garcia J.M., Smith R.G. Characterization of adult ghrelin and ghrelin receptor knockout mice under positive and negative energy balance. Endocrinology. 2008;149(2):843–850. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sugiishi A., Kimura M., Kamiya R., Ueki S., Yoneya M., Saito Y. Derangement of ghrelin secretion after long-term high-fat diet feeding in rats. Hepatology Research. 2013;43(10):1105–1114. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sun Y., Ahmed S., Smith R.G. Deletion of ghrelin impairs neither growth nor appetite. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2003;23(22):7973–7981. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.7973-7981.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sun Y., Wang P., Zheng H., Smith R.G. Ghrelin stimulation of growth hormone release and appetite is mediated through the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(13):4679–4684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305930101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wortley K.E., Anderson K.D., Garcia K., Murray J.D., Malinova L., Liu R. Genetic deletion of ghrelin does not decrease food intake but influences metabolic fuel preference. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(21):8227–8232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402763101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kirchner H., Gutierrez J.A., Solenberg P.J., Pfluger P.T., Czyzyk T.A., Willency J.A. GOAT links dietary lipids with the endocrine control of energy balance. Nature Medicine. 2009;15(7):741–745. doi: 10.1038/nm.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ma X., Lin Y., Lin L., Qin G., Pereira F.A., Haymond M.W. Ablation of ghrelin receptor in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice has paradoxical effects on glucose homeostasis when compared with ablation of ghrelin in ob/ob mice. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;303(3):E422–E431. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00576.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cummings D.E. Ghrelin and the short- and long-term regulation of appetite and body weight. Physiology & Behavior. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Foster-Schubert K.E., Overduin J., Prudom C.E., Liu J., Callahan H.S., Gaylinn B.D. Acyl and total ghrelin are suppressed strongly by ingested proteins, weakly by lipids, and biphasically by carbohydrates. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;93(5):1971–1979. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tschop M., Weyer C., Tataranni P.A., Devanarayan V., Ravussin E., Heiman M.L. Circulating ghrelin levels are decreased in human obesity. Diabetes. 2001;50(4):707–709. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zigman J.M., Bouret S.G., Andrews Z.B. Obesity impairs the action of the neuroendocrine ghrelin system. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2016;27(1):54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.DelParigi A., Tschop M., Heiman M.L., Salbe A.D., Vozarova B., Sell S.M. High circulating ghrelin: a potential cause for hyperphagia and obesity in prader-willi syndrome. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;87(12):5461–5464. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shiiya T., Nakazato M., Mizuta M., Date Y., Mondal M.S., Tanaka M. Plasma ghrelin levels in lean and obese humans and the effect of glucose on ghrelin secretion. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;87(1):240–244. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.1.8129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ukkola O., Poykko S.M., Antero Kesaniemi Y. Low plasma ghrelin concentration is an indicator of the metabolic syndrome. Annals of Medicine. 2006;38(4):274–279. doi: 10.1080/07853890600622192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Barazzoni R., Zanetti M., Ferreira C., Vinci P., Pirulli A., Mucci M. Relationships between desacylated and acylated ghrelin and insulin sensitivity in the metabolic syndrome. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92(10):3935–3940. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Perreault M., Istrate N., Wang L., Nichols A.J., Tozzo E., Stricker-Krongrad A. Resistance to the orexigenic effect of ghrelin in dietary-induced obesity in mice: reversal upon weight loss. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2004 doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.English P.J., Ghatei M.A., Malik I.A., Bloom S.R., Wilding J.P. Food fails to suppress ghrelin levels in obese humans. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;87(6):2984. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Banks W.A., Tschop M., Robinson S.M., Heiman M.L. Extent and direction of ghrelin transport across the blood-brain barrier is determined by its unique primary structure. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2002;302(2):822–827. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.034827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Briggs D.I., Enriori P.J., Lemus M.B., Cowley M.A., Andrews Z.B. Diet-induced obesity causes ghrelin resistance in arcuate NPY/AgRP neurons. Endocrinology. 2010;151(10):4745–4755. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Martin N.M., Small C.J., Sajedi A., Patterson M., Ghatei M.A., Bloom S.R. Pre-obese and obese agouti mice are sensitive to the anorectic effects of peptide YY(3-36) but resistant to ghrelin. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2004 doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gardiner J.V., Campbell D., Patterson M., Kent A., Ghatei M.A., Bloom S.R. The hyperphagic effect of ghrelin is inhibited in mice by a diet high in fat. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2468–2476. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.012. 2476 e2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Naznin F., Toshinai K., Waise T.M., NamKoong C., Md Moin A.S., Sakoda H. Diet-induced obesity causes peripheral and central ghrelin resistance by promoting inflammation. Journal of Endocrinology. 2015;226(1):81–92. doi: 10.1530/JOE-15-0139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tamboli R.A., Antoun J., Sidani R.M., Clements A., Harmata E.E., Marks-Shulman P. Metabolic responses to exogenous ghrelin in obesity and early after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in humans. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2017;19(9):1267–1275. doi: 10.1111/dom.12952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Poykko S.M., Kellokoski E., Horkko S., Kauma H., Kesaniemi Y.A., Ukkola O. Low plasma ghrelin is associated with insulin resistance, hypertension, and the prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52(10):2546–2553. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Katsuki A., Urakawa H., Gabazza E.C., Murashima S., Nakatani K., Togashi K. Circulating levels of active ghrelin is associated with abdominal adiposity, hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2004;151(5):573–577. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1510573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bideci A., Camurdan M.O., Cinaz P., Demirel F. Ghrelin, IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005;18(12):1433–1439. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2005.18.12.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Soriano-Guillen L., Barrios V., Lechuga-Sancho A., Chowen J.A., Argente J. Response of circulating ghrelin levels to insulin therapy in children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatric Research. 2004;55(5):830–835. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000120679.92416.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Holdstock C., Ludvigsson J., Karlsson F.A. Abnormal ghrelin secretion in new onset childhood Type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2004;47(1):150–151. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Huml M., Kobr J., Siala K., Varvarovska J., Pomahacova R., Karlikova M. Gut peptide hormones and pediatric type 1 diabetes mellitus. Physiological Research. 2011;60(4):647–658. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Murdolo G., Lucidi P., Di Loreto C., Parlanti N., De Cicco A., Fatone C. Insulin is required for prandial ghrelin suppression in humans. Diabetes. 2003;52(12):2923–2927. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Prodam F., Cadario F., Bellone S., Trovato L., Moia S., Pozzi E. Obestatin levels are associated with C-peptide and antiinsulin antibodies at the onset, whereas unacylated and acylated ghrelin levels are not predictive of long-term metabolic control in children with type 1 diabetes. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;99(4):E599–E607. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Cassidy S.B., Schwartz S., Miller J.L., Driscoll D.J. Prader-Willi syndrome. Genetics in Medicine. 2012;14(1):10–26. doi: 10.1038/gim.0b013e31822bead0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Miller J.L. Approach to the child with prader-willi syndrome. The Journal of Cinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97(11):3837–3844. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Goldstone A.P. Prader-Willi syndrome: advances in genetics, pathophysiology and treatment. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;15(1):12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Holm V.A., Cassidy S.B., Butler M.G., Hanchett J.M., Greenswag L.R., Whitman B.Y. Prader-Willi syndrome: consensus diagnostic criteria. Pediatrics. 1993;91(2):398–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Rodriguez J.A., Zigman J.M. Hypothalamic loss of Snord116 and Prader-Willi syndrome hyperphagia: the buck stops here? Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2018;128(3):900–902. doi: 10.1172/JCI99725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Cummings D.E., Clement K., Purnell J.Q., Vaisse C., Foster K.E., Frayo R.S. Elevated plasma ghrelin levels in Prader Willi syndrome. Nature Medicine. 2002;8(7):643–644. doi: 10.1038/nm0702-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]