Abstract

In this review, we aim to summarize research findings and marketplace apps for women with perinatal mood disorders with the goal of informing clinicians and patients about current risks and benefits, as well as proposing clinical implementation advice and a harmonized agenda for both academic and industry advancement in this space. Multiple searches were run of academic databases in 2018–2020, examining literature on mobile apps for peripartum mental health. Multiple searches were also run of the iOS and Android app stores in 2019 and 2020, looking at apps for peripartum mental health. Results were compared within the academic dataset as well within the commercial app dataset; the two datasets were also examined for overlap. The academic search results were notable for small sample sizes and heterogeneous endpoints. The app store search results were notable for apps of generally poor quality (as assessed by a modified Silberg scale). Very few of the mHealth interventions studied in the academic literature were available in the app store; very few of the apps from the commercial stores were supported by academic literature. The disconnect between academically developed apps and commercially available apps highlights the need for better collaboration between academia and industry. More collaboration between the two approaches may benefit both app developers and patients in this demographic moving forwards. Additionally, we present a set of practice guidelines for mHealth in perinatal psychiatry based on the trends identified in this review.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00737-021-01138-z.

Keywords: mHealth, Digital mental health, Perinatal mental health

Introduction

Perinatal mental health has become an area of increasing interest in the past several years. Robust evidence has demonstrated the elevated prevalence of mental illness in the perinatal period, with postpartum depression affecting up to 1 in 7 women (Osborne et al. 2015). Perinatal anxiety, mania, and psychosis further increase the prevalence and burden. The myriad consequences of undertreated perinatal mental illness are well documented, including impaired fetal development, impaired maternal–fetal bonding, and difficulties for offspring later in life (Bansil et al. 2010; Field et al. 2006; Beebe et al. 2008; Glover et al. 2010; Murray et al. 2003). Perinatal illness also has the potential to be associated with mortality; suicides account for 1 in 5 perinatal deaths (Lindahl et al. 2005), and postpartum psychosis is associated with up to a 4.5% risk of infanticide (Brockington 2017).

Despite this acute need for services, today it remains challenging for women in the perinatal period to access mental health care. While more focus has been placed on the importance of screening in this population, only about a quarter of those who screen positive are actually connected with treatment resources (Stuart-Parrigon and Stuart 2014). This need for mental health care has only increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (Czeisler et al. 2020). Given the prevalence and impact of perinatal mental illness, as well as the lack of resources, there is a need for innovative solutions to increase access to information, resources, and care.

Mental health smartphone applications offer a solution given their increasing prevalence as well as ability to both assess patient status in addition to offering interventions. Today, smartphone prevalence rates among women in the USA are around 79% and above 90% for women ages 18–49 (Pew 2019). Through surveys, smartphones can capture traditional scales like the EPDS and through sensors can also capture data related to activity, sleep, energy etc. This real-time data offers a novel window in perinatal mental health that allows understanding of how both the environment and temporal dynamic impact clinical state. Finally, there are already thousands of mental health apps available today offering on demand psychoeducation, therapy skills, and other resources that are easily accessible. This access combined with potential for novel data capture and interventions presents a new opportunity to not only expand access to evidence-based care but also quality of that care.

However, this potential has not yet been fully realized in many fields of mental health. Reviews of research on general depression, anxiety, and substance use have examined the research evidence for mental health apps and found the current evidence does not support recommending them for routine clinical use (Lecomte et al. 2020; Connolly et al. 2020). In terms of the marketplace and app stores, increasing research suggests that apps available to consumers are often untested (Larsen et al. 2019) and may present privacy risks that may expose sensitive mental health data (Huckvale et al. 2019. For example, in January 2021, the period tracking app, Flo, settled Federal Trade Commission allegations that the company inappropriately shared the health information of users (FTC 2021). Preliminary evidence has shown that women in the perinatal period are likely to use mobile devices to access health-related information (Osma et al. 2016), suggesting that perinatal mental illness may be an area well-suited to digital mental health interventions. Recent reviews have examined the research in the perinatal app space (Dol et al. 2020; Hussain-Shamsy et al. 2020; Chan and Chen 2019), and one review in 2017 investigated the commercial apps available to patients (Zhang et al. 2017). However, no recent reviews have examined both the marketplace offerings and the clinical evidence, to provide a complete picture both of the evidence for apps in this space as well as the quality of apps which are available to consumers. In this review, we aim to summarize research findings and marketplace apps with the goal of informing clinicians and patients about current risks and benefits, as well as proposing clinical implementations advice and a harmonized agenda for both academic and industry advancement in this space.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al. 2009).

Search methodology

We conducted searches of the academic literature and app stores.

Three separate systematic searches were conducted in order to understand how this space is evolving in terms of academic literature. The first was a systematic search of electronic academic databases including CINAHL, EMBASE, Health Business Elite, PsycInfo, PubMed, and Web of Science. The initial search was conducted on August 16, 2018, the second on October 21, 2019, and the third on October 22, 2020. Similar searches were run on all 6 databases, with slight changes in wording and formatting as indicated for the different search programs. One example search is that which was run through EMBASE, which was searched for:

(“software”/exp OR “software” OR “computer code” OR “mobile application”/exp OR “mobile application”) AND (“perinatal depression”/exp OR “perinatal depression” OR “postpartum depression” OR “antenatal depression”/exp OR “antenatal depression” OR “peripartum depression”)

Two searches of the app stores were conducted in order to understand how this space is evolving in terms of the two most commonly used mobile app stores in the USA: the Apple App Store (iOS) and the Google Play store (Android). Searches were performed in April 2019 and July 2020. These store searches were based off of the database searches and involved the following keywords for the Google Play store:

“postpartum depression OR peripartum depression OR antenatal depression OR postnatal depression OR perinatal depression”

The Apple App Store did not allow for advanced or Boolean searching; it was thus searched for “postpartum depression.”

Study and app selection

The primary inclusion criteria were type of technology (mobile app), target time period (perinatal, allowing for up to a year postpartum in order to ensure maximum capture), and target condition (mood disorders). For academic results, if the publication did not primarily focus on the relevant technology type, target time period, and target condition, it was excluded. Results which were not in English, conference abstracts, and dissertations/theses were excluded. Results which described Internet-based but not mobile-app interventions were excluded in order to focus this review on mobile apps in particular. Results which described in-office interventions, e.g., interventions in which patients are handed a tablet while in the office waiting area, were excluded as they were deemed to be fundamentally in-office interventions aided by technology, rather than strictly mobile interventions in and of themselves. Only primary literature was included; reviews were excluded. Research regarding or apps including monitoring or screening only, with no direct intervention, were excluded. Of note, this review did evaluate some studies in which mHealth apps which were initially built for a general population were tested in this specific population (for example, see Baumel et al. 2018).

For the academic database searches, a total of 375 results were returned. For the app store searches, a combined total of 1141 results were returned in the 2019 search; a total of 475 results were returned in the 2020 search. Results were manually reviewed by one of the authors to determine if they met inclusion criteria. Disputes were resolved by consensus of all. For academic database results, both abstract and full text were reviewed.

Some results from the commercial searches focused on general peripartum wellness, including but not limited to peripartum depression. Within this category, purely informational apps were excluded, but apps with any intervention were included. For app store results, free apps were downloaded. Apps which had a download cost were assessed based on information available outside the paywall, including sample photos, description, and links to the developer’s website when available. This mirrors the realities of how a consumer or clinician can evaluate these apps today.

Analysis of information

Data was collected by manual coding of individual characteristics. The relevant characteristics of academic publications and apps, respectively, were decided in advance.

Among the academic publications, risk of bias was assessed via the Cochrane EPOC Group Risk of Bias tool (Cochrane 2017). An academic risk of bias tool was not appropriate for assessing the app store results, as the majority of these apps did not cite studies reviewing their efficacy (see Supplemental Table 1).

Academic publications were assessed based on a series of predetermined criteria aimed at evaluating transparency, methodology, accessibility, and information quality. Data points included the type of publication and whether it was peer-reviewed; target condition and sample size; funding source; mobile app platform and cost; target outcomes and study findings; length of follow-up; and date of publication. For the full list of data points assessed, please see Table 1.

Table 1.

Academic database search results

| Article | Platform | App cost | Funding source | Target condition | Sample size | Method | Outcomes | Length of follow-up | Evidence | Also in app store? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dennis-Tiwary et al. (2017). Salutary effects of an attention bias modification mobile application on biobehavioral measures of stress and anxiety during pregnancy | iOS | Free | NIH, NIMHD | Antenatal anxiety | 33 | Attention bias modification training | Self-report anxiety, stress, depression; salivary cortisol; ERP (event-related potential on EEG) to threat cues | 4 weeks | No effect on subjective anxiety, positive effect on cortisol level | Yes |

| Hantsoo et al. (2018). A mobile application for monitoring and management of depressed mood in a vulnerable pregnant population | iOS, Android | Free | Ginger.io; Penn Center for Healthcare Innovation; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program | Antenatal depression | 72 | Tracking | PHQ9; GAD; number of phone calls with providers (as a proxy for patient engagement); subjective ease of managing mental health with the app | 8 weeks | Improved PHQ9, GAD scores; more provider phone encounters that mentioned mental health, and better anxiety/depression scores in those that did have such a phone call | No |

| Chan et al. (2019). Using smartphone-based psychoeducation to reduce postnatal depression among first-time mothers: Randomized controlled trial | Not specified | Free | Health and Medical Research Fund, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region | Antenatal and postnatal depression | 660 | Education | EPDS; secondary: anxiety, stress level, health-related QoL | 4 weeks | Improved EPDS at 4 weeks compared to control | No |

| Teychenne et al. (2018). Feasibility and acceptability of a home-based physical activity program for postnatal women with depressive symptoms: A pilot study | Web app | Not specified | Institutional | Postpartum depression at 3–6 months | 11 | Education, motivational material | EPDS | 8 weeks | Improved EPDS scores | Unknown |

| Baumel et al. (2018). Digital Peer-Support Platform (7Cups) as an adjunct treatment for women with postpartum depression: Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy study | URL, certain part available via app | Free | Not specified | Postpartum depression and anxiety | 20 | Self-help tools, peer support | Beck depression inventory II; EPDS; Beck anxiety inventory | 2 months | Improved EPDS but no difference with control | Yes |

| Goetz et al. (2020). Effects of a brief electronic mindfulness-based intervention on relieving prenatal depression and anxiety in hospitalized high-risk pregnant women: Exploratory pilot study | Not specified | Free | Not specified | Peripartum depression and anxiety during inpatient stay | 68 | Mindfulness | EPDS; STAI-S; abridged version of PRAQ-R | None | Improved childbirth anxiety (reduction in PRAQ-R and STAI-S), no change in EPDS | Yes |

| Jannati et al. (2020). Effectiveness of an app-based cognitive behavioral therapy program for postpartum depression in primary care: A randomized controlled trial | Not specified | Free | None | Postpartum depression | 78 | CBT | EPDS | 2 months | Significantly improved EPDS between baseline and 2 months in intervention group (no change in control) | No |

| Shorey et al. (2017). A randomized‐ controlled trial to examine the effectiveness of the ‘Home‐but not Alone’ mobile‐ health application educational programme on parental outcomes | Not specified | Not specified | National University of Singapore Start-Up Grant | Postpartum depression in first-time parents | 250 | Education | EPDS | 6 weeks | No significant change in depression | No |

| Sawyer et al. (2019). The effectiveness of an app-based nurse-moderated program for new mothers with depression and parenting problems (eMums Plus): Pragmatic randomized controlled trial | iOS, Android | Free | Channel 7 Children’s Research Foundation Grant (161,258); National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centres of Research Excellence Grant (1,099,422) | Postnatal depression, maternal self-competence, quality of mother-infant relationship | 160 | Nurse-led group intervention, education, peer support | EPDS; maternal self- competence (PSCS, PSI competence subscale); quality of mother-infant relationship (SCAST scale, PSI attachment subscale) | 12 months | No significant change in depressive symptoms nor improvement in maternal caregiving; mothers in intervention found app helpful and easy to use | Yes |

Mobile apps were assessed on criteria based on a modified Silberg scale (Griffiths and Christensen 2000), a set of criteria for assessing the information quality of digital health smartphone applications. Categories which are assessed include authorship, attribution of information sources, disclosure, and currency. In addition to the Silberg scale criteria, the apps were assessed by whether the app cited any data supporting its use; whether the app had any connection to academia; overall methodology; target of the app; transparency around what can be done with user data; and cost to download. Overall, the app assessments were aimed at evaluating transparency, methodology, accessibility, and evidence basis. For the full list of data points assessed, please see Table 2.

Table 2.

App store search results

| App name | Developer | Platform | Cost | Year updated | Does the app have a connection to academia? | Is there any research supporting this app? | Does it cite its sources? | Method | Target condition | Funding source provided? | Authors’ names and credentials provided? | Does the app specify what it does with user data? | Silberg score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postpartum Depression | El Makaoui | Android | Free | 2019 | No | No | No | Education | Postpartum depression | No | No | No | 1 |

| MamaMend | MamaMend | Android | Free | 2020 | No | No | Yes | Education | General postpartum wellness | No | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Post Pregnancy Recovery | Not clear | Android | Free | 2018 | No | No | No | Education and tips | Postpartum depression, general postpartum wellness | No | No | “May collect anonymous usage data” | 1 |

| Mom Stuff: Real Talk for Real Mamas | Laura Pigg | iOS | Free | 2019 | No | No | Yes | Peer support, education, assessment, tips | Postpartum depression, postpartum anxiety | No | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| APGO Perinatal Depression | Fountainhead Mobile Solutions | iOS, Android | Free | 2020 | Yes | No | No | Education | Providers (obstetrics) | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Mom Net Mobile | Oregon Research Behavioral Intervention Strategies and ORBIS, Inc | iOS, Android | Free | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Unknown | CBT | Postpartum depression | Yes | Yes | No | 3 |

| Veedamom | Daya Veeda LLC | iOS | Free | 2018 | No | No | No | Tracking, education, meditation, tips | Postpartum depression, general postpartum wellness | No | One name, no credentials | “May be used for research purposes” | 3 |

| Postpartum Depression | Pinkdev | Android | Free | 2017 | No | No | No | Education | Postpartum depression | No | One name, no credentials | No | 3 |

| Lifeline4 Moms | Worcester Polytechnic Institute | iOS, Android | Free | 2018 | Yes | Yes for the recommendations made in the app, but not for the app itself | Some | Assessment and recommendations | Providers (obstetrics) | Partially | Yes | No | 7 |

| Moment Health | Moment Health | Android (in 2019, also iOS) | Free | 2018 | Yes | Research is referred to but details are not provided | No | Tracking, community resources | Postpartum mental health | No | No | No | 3 |

| Overcome Postpartum Anxiety and Depression-Help | Wenqiang Yan | iOS | $2.99 | 2016 | No | No | No | Education, tips, supportive quotes | Postpartum depression and anxiety | No | One name, no credentials | No | 3 |

| OCD During Pregnancy | OCD Inc | iOS | $17.99 | 2016 | No | No | No | Education, workbook | Peripartum OCD | No | One name, no credentials | No | 3 |

The collected data was analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Academic database result characteristics

A total of nine academic publications were included. All publications were peer-reviewed. Target conditions included peripartum, antepartum, and postpartum depression and anxiety. Some studies looked at specific groups within the larger target conditions including first-time parents, at 3–6 months postpartum, and during inpatient stay. The sample sizes were small with 67% studying less than 100 participants (n = 6), and only 11% with over 500 participants (n = 1). They also had relatively short length of follow-up; only 1 study had 12-month follow-up and the rest (89%) had less than 2-month follow-up (n = 8).

The academic publications focused mostly on the use of intervention-based apps (n = 5), including ones utilizing mindfulness (n = 1), CBT (n = 1), nurse-led interventions (n = 1), attention bias modification training (n = 1), and educational and motivational material to increase physical exercise (n = 1). Many also focused on apps utilizing education (n = 4). Other studies provided peer support (n = 1) and symptom tracking (n = 1). All of the studies measured at least one of the outcomes via various scales, with most popular being EPDS (n = 7). Other scales were used such as PHQ-9, GAD, and Beck depression and anxiety inventory. One study measured salivary cortisol and ERP (event-related potential on EEG) to threat cues. Forty-four percent showed evidence for the intervention (n = 4), 22% showed mixed evidence (n = 2), 22% showed no significant change (n = 2), and 11% showed no difference with control (n = 1). Forty-four percent (n = 4) studied apps also found in the app store, though one was not in English. Unfortunately, none of these apps was found in the initial application search.

App store result characteristics

A total of 12 apps were included. When comparing the identical searches run in April 2019 and July 2020, only one app appeared in both searches. Two of the apps included in the initial search were no longer available on the app store by the second iteration of search 1 year later. Interestingly, 5 apps which appeared in the 2019 search did not appear in the identical search run in 2020, but when searched manually by app name, were found.

The most common target conditions of these apps were postpartum depression (n = 7) and postpartum anxiety (n = 2) with some emphasizing general postpartum wellness (n = 3). Two apps were targeted towards obstetric providers, while the rest were targeted towards patients. The apps focused mostly on education (n = 9), though some also utilized assessment (n = 2), tips (n = 4), tracking (n = 2), support (n = 2), CBT (n = 1), and community resources (n = 1).

Seventy-five percent of apps (n = 9) scored less than 5 on the Silberg scale, with the highest score being 7 (n = 2) out of a possible score of 9. Less than 30% of the apps (n = 2) had any supporting research. Of those, one of the apps referred to research; however, details were not provided and the other referred to research for the recommendations made in the app, but not for the app itself. Only 25% of apps (n = 3) cited their sources and one of those cited only some of its sources. Three apps provided funding sources, of which one app provided only partial funding data. Regarding users’ data, 66% of apps (n = 8) did not specify what they did with user data.

Discussion

In this review, we examined both the academic literature and commercial app stores for mobile health interventions targeting perinatal mental health. We found little overlap, either in terms of actual apps (n = 1) or research findings put into practice, between the academic and the commercial approach to this field. In terms of quality, both the academic literature and commercial offering remained low quality; there were not substantial changes between timepoints captured in our data collection.

Focusing on the app stores, of the 12 apps included in this review, only one cited research supporting that app; another referenced said evidence but did not provide details. Four out of the 12 apps indicated some connection to academia. Taken together, these two trends (very little academic involvement for commercial apps, and very little commercial availability for academically developed apps) suggest a concerning disconnect between the academic approach and the commercial approach to the digital mental health space in this population. We found that even finding apps on the commercial marketplace was not simple, as four of the articles described apps which were available when searched for by name but did not appear in our survey of the app stores. When considering the patient population, we modeled our search terms (e.g., “postpartum depression”) after what we believe real patients would type into the app store when searching for resources. Therefore, there is some question as to whether apps which exist in the store but are not easily found can be considered as resources available to the average patient.

Apps were assessed based on a number of criteria, including a modified Silberg scale (Griffiths and Christensen 2000), which is a tool to evaluate the quality of digital health information. Of the 12 apps in this study, only three specified the source of their funding. In the initial search of the app stores in 2019, only one of the apps (14%) commented on what was done with user data (another app stated that it “may collect anonymous usage data” but did not clearly state what was done with that data). In contrast, when the search was run again a year later, 4 out of 12 (33%) specified what they did with user data, which may suggest a positive trend towards more transparency around data use. Overall, these apps provided little of the data necessary for users to make an informed decision about the app’s quality. Also worthy of note are the apps which were not included in this analysis. Of the results from searching “postpartum depression” in the Android app store in 2020, 9% (n = 22) were not related to mental health at all. Of those, more than half were fitness apps, promising faster ways to lose baby weight. While physical activity can help reduce the burden of depressive symptoms, the focus on body image and messaging of these apps is troubling, particularly in this context.

Moving from the app stores to the academic literature, studies reported generally showed positive findings; however, these studies measured a wide range of heterogeneous outcomes, precluding broad statements about either efficacy or usability. The utility of these studies was also limited by small sample sizes, with only three studies including more than 100 participants, limiting the generalizability of these results to a larger population. The number of studies with positive findings, however, does offer some evidence for the feasibility of mHealth interventions as an approach to this population.

In terms of trends across time in both the academic and app marketplaces, we found little substantial change. When the same searches were run in the app stores in 2019 and 2020, only a single app appeared in both the initial and the repeat search, despite using the same search terms. A secondary analysis revealed that five apps from the initial search results were still available in the app stores, but no longer appeared as results of the same search, while two apps from the initial set were no longer available in the app store. This suggests changes in the search algorithms of the app stores themselves, as well as turnover in app availability, which may pose limitations for systematic research in this area. In the academic dataset, a number of new studies appeared in the literature between the initial and the final academic search, suggesting that research in this area is ongoing, but overall quality of studies did not improve.

These findings are in line with prior results. Other studies have investigated the academic literature (Dol et al. 2020; Hussain-Shamsy et al. 2020; Chan and Chen 2019) and also found nascent results, with our study covering 15 to 28 months past these. Prior research on the commercial app space (Zhang et al. 2017) also found evidence of limited quality apps, which we confirm has not greatly improved even 3 years later.

Like all reviews, there are several limitations which must be considered. The heterogeneity of the outcome measures and app tools used in the academic literature make it difficult to draw generalizable conclusions about mHealth for this population. Another limitation of this study at the review level is that the iOS and Android app stores do not allow for nuanced searching, raising the possibility that relevant apps are commercially available but were not included in this search (and indeed several apps which appeared under this search initially were no longer found under the same search a year later, despite still being in the app store). However, one goal of this review is to assess the apps which are available to consumers; therefore, we argue that this is actually a close approximation of the search that a consumer would run when searching for an app of this type. Future research may benefit from an investigation of what real-world women search for when seeking out perinatal mental health support in these settings.

Conclusions

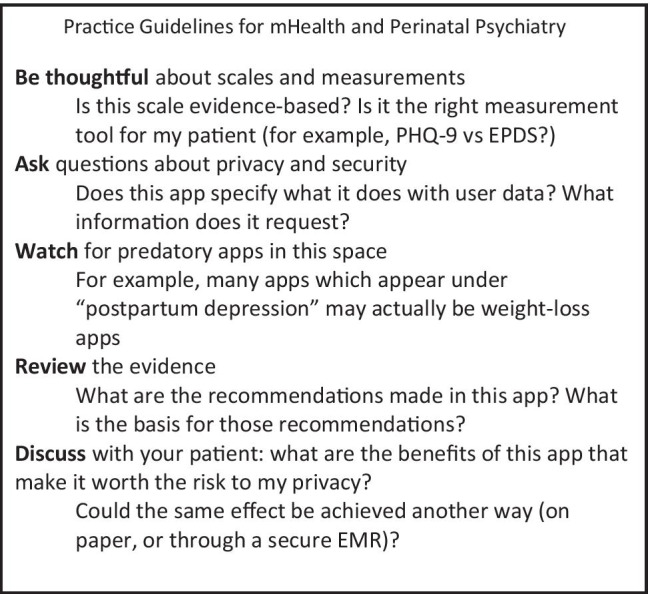

Based on the findings of this review, the authors have developed a set of practice guidelines for perinatal psychiatrists. These guidelines are intended to empower physicians to thoughtfully interact with the apps in this space and are based on the evidence highlighted in this paper (see Fig. 1). Ideally, this tool can be used by patients and providers together, to guide conversations about specific apps and whether they may be appropriate for that patient’s needs. While the space remains nascent, understanding its limitations and being able to explore those with patients is a critical skill today, as more and more patients are interested in digital mental health tools.

Fig. 1.

Practice guidelines for mHealth and perinatal psychiatry

The disconnect between academically developed apps and commercially available apps highlights the need for better collaboration between academia and industry. The academic approach, as shown in this review, has the advantage of a basis in evidence and rigorous measurements, but many of the apps developed by academia don’t make it to consumer-facing platforms. The industry approach has an advantage at getting new apps into consumers’ reach, but would benefit from a more evidence-based approach to both the tips provided in these apps and to the interventions themselves. More collaboration between the two approaches may benefit both app developers and patients in this demographic moving forward.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge David L. Osterbur, PhD’s assistance with data gathering for this review

Author contribution

All authors have contributed sufficiently to this manuscript, and all authors have approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

No proprietary dataset was used in this research.

Code availability

N/A

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Torous has received research support from Ostuka in the past 36 months.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Natalie Feldman, Email: nsfeldman@partners.org.

Diana Back, Email: dback@bwh.harvard.edu.

Robert Boland, Email: rboland@menninger.edu.

John Torous, Email: jtorous@bidmc.harvard.edu.

References

- Bansil P, Kuklina EV, Meikle SF, Posner SF, Kourtis AP, Ellington SR, Jamieson DJ. Maternal and fetal outcomes among women with depression. J Womens Health. 2010;19(2):329–334. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumel A, Tinkelman A, Mathur N, Kane JM. Digital peer-support platform (7Cups) as an adjunct treatment for women with postpartum depression: feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(2):e38. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.9482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe B, Jaffe J, Buck K, Chen H, Cohen P, Feldstein S, Andrews H. Six-week postpartum maternal depressive symptoms and 4-month mother-infant self- and interactive contingency. Infant Ment Health J. 2008;29(5):442–471. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockington I. Suicide and filicide in postpartum psychosis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(1):63–69. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0675-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, Chen M. Effects of social media and mobile health apps on pregnancy care: meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(1):e11836. doi: 10.2196/11836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, Leung WC, Tiwari A, Or KL, Ip P. Using smartphone-based psychoeducation to reduce postnatal depression among first-time mothers: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(5):e12794. doi: 10.2196/12794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions | Cochrane Training (2017) Retrieved Feb 11, 2021 from https://training.cochrane.org/cochrane-handbook-systematic-reviews-interventions

- Connolly SL, Hogan TP, Shimada SL, Miller CJ (2020) Leveraging implementation science to understand factors influencing sustained use of mental health apps: a narrative review. J Technol Behav Sci, 1–13. 10.1007/s41347-020-00165-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, Weaver MD, Robbins R, Facer-Childs ER, Barger LK, Czeisler CA, Howard ME, Rajaratnam SMW. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demographics of Mobile Device Ownership and Adoption in the United States | Pew Research Center (2019) Retrieved Feb 11, 2021 from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/

- Dennis-Tiwary TA, Denefrio S, Gelber S. Salutary effects of an attention bias modification mobile application on biobehavioral measures of stress and anxiety during pregnancy. Biol Psychol. 2017;127:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dol J, Richardson B, Murphy GT, Aston M, McMillan D, Campbell-Yeo M. Impact of mobile health interventions during the perinatal period on maternal psychosocial outcomes: a systematic review. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(1):30–55. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M. Prenatal depression effects on the fetus and newborn: a review. Infant Behav Dev. 2006;29(3):445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flo Health, Inc. | Federal Trade Commission (2021) Retrieved Feb 11, 2021 from https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/cases-proceedings/1923133/flo-health-inc

- Glover V, O’Connor TG, O’Donnell K. Prenatal stress and the programming of the HPA axis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz M, Schiele C, Müller M, Matthies LM, Deutsch TM, Spano C, Graf J, Zipfel S, Bauer A, Brucker SY, Wallwiener M, Wallwiener S. Effects of a brief electronic mindfulness-based intervention on relieving prenatal depression and anxiety in hospitalized high-risk pregnant women: exploratory pilot study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e17593. doi: 10.2196/17593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Quality of web based information on treatment of depression: cross sectional survey. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2000;321(7275):1511–1515. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7275.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantsoo L, Criniti S, Khan A, Moseley M, Kincler N, Faherty LJ, Epperson CN, Bennett IM. A mobile application for monitoring and management of depressed mood in a vulnerable pregnant population. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(1):104–107. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckvale K, Torous J, Larsen ME. Assessment of the data sharing and privacy practices of smartphone apps for depression and smoking cessation. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192542. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain-Shamsy N, Shah A, Vigod SN, Zaheer J, Seto E. Mobile health for perinatal depression and anxiety: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(4):e17011. doi: 10.2196/17011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannati N, Mazhari S, Ahmadian L, Mirzaee M. Effectiveness of an app-based cognitive behavioral therapy program for postpartum depression in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Med Informatics. 2020;141:104145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen ME, Huckvale K, Nicholas J, Torous J, Birrell L, Li E, Reda B. Using science to sell apps: evaluation of mental health app store quality claims. Npj Digit Med. 2019;2:18. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0093-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte T, Potvin S, Corbière M, Guay S, Samson C, Cloutier B, Francoeur A, Pennou A, Khazaal Y. Mobile apps for mental health issues: meta-review of meta-analyses. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(5):e17458. doi: 10.2196/17458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Cooper PJ, Wilson A, Romaniuk H. Controlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression: 2. Impact on the mother-child relationship and child outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:420–427. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.5.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne LM, Hermann A, Burt V, Driscoll K, Fitelson E, Meltzer-Brody S, Barzilay EM, Yang SN, Miller L, National Task Force on Women’s Reproductive Mental Health Reproductive psychiatry: the gap between clinical need and education. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):946–948. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osma J, Barrera AZ, Ramphos E. Are pregnant and postpartum women interested in health-related apps? Implications for the prevention of perinatal depression. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2016;19(6):412–415. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer A, Kaim A, Le H-N, McDonald D, Mittinty M, Lynch J, Sawyer M. The effectiveness of an app-based nurse-moderated program for new mothers with depression and parenting problems (eMums Plus): pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(6):e13689. doi: 10.2196/13689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey S, Lau Y, Dennis C-L, Chan YS, Tam WWS, Chan YH. A randomized-controlled trial to examine the effectiveness of the “Home-but not Alone” mobile-health application educational programme on parental outcomes. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(9):2103–2117. doi: 10.1111/jan.13293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart-Parrigon K, Stuart S. Perinatal depression: an update and overview. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(9):468. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0468-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teychenne M, van der Pligt P, Abbott G, Brennan L, Olander EK. Feasibility and acceptability of a home-based physical activity program for postnatal women with depressive symptoms: a pilot study. Ment Health Phys Act. 2018;14:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2018.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang MW, Ho RC, Loh A, Wing T, Wynne O, Chan SWC, Car J, Fung DSS. Current status of postnatal depression smartphone applications available on application stores: an information quality analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e015655. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No proprietary dataset was used in this research.

N/A