Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells are advantaged innate cytotoxic lymphocytes with characteristics of tumor immunosurveillance and microorganism elimination. Distinguish from the adaptive T and B lymphocytes, the autologous or allogeneic NK cells efficaciously fulfil the function of combating transformed hematological malignancies and metastatic solid tumors via the proverbial mechanisms including direct cytolytic effect and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) as well as paracrine effects dispense with antigen presentation. Herein, we review the candidate sources (e.g., peripheral blood, umbilical cord blood, placental blood, cell lines and stem cells) for large-scale and clinical-grade NK cell manufacturing, ex vivo cultivation (feeder-, cytokine cocktail- or physicochemical irritation-dependent strategies) for NK cell persistence and activation. Furthermore, we also figure out the promising prospects as well as the accompanied challenges of NK cell- or chimeric antigen receptor-transduced NK (CAR-NK) cell-based adoptive immunotherapy in standardizations for industrialized preparation and clinical practices.

Keywords: Natural killer cells (NKs), large-scale manufacture, cancer immunotherapy, chimeric antigen receptor-transduced NK (CAR-NK), clinical trials

Introduction

Anti-cancer immunotherapy, including the immune-checkpoint inhibitors and adoptive cellular transplantation, has emerged as novel therapeutic strategies by relieving or eliminating cancer-induced immunosuppression [1,2]. In recent years, immunotherapy has become a rosy and powerful implement for hematologic malignancy and multiple solid tumor management in both preclinical and clinical practices [3,4]. Nevertheless, the potentially swift adverse effects (e.g., autoimmunity, nonspecific inflammation, innate or acquired resistance) and the difficulty in achieving controllable modulation of the immune response are the key challenges and prerequisites in the extensive implementation of immunotherapies for tumor, and in particular, the hurdles in adoptive T lymphocyte-based immunotherapy and double-edged characteristics of cancer immunoediting [3-5].

Natural killer (NK) cells, a heterogeneous lymphocyte sub-population originated from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in bone marrow environment, were firstly identified from mouse with characteristics of cytolytic effector without requirement for preliminary antigen presentation by Kiessling and their colleagues in the 1970s [6]. The functional maturation of NK cells, also known as “NK cell education”, involves step-wise intermediates and acquires self major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) recognition via inhibitory receptors [7]. Generally, NK cells in humans are historically divided into two subsets including the IFN-γ-producing CD3-CD56brightCD16+ and cytotoxic CD3-CD56dimCD16high counterparts, which spontaneously facilitate tumor immunosurveillance, pathogenic microorganism and abnormal cell elimination via cytokine- or receptor-ligand-mediated natural cytotoxicity effects, respectively [8-10]. Of the two distinct subsets, the CD3-CD56dim NK cells are the most numerous in blood, while the CD3-CD56bright subset is characterized with less maturation [11]. Additionally, numerous reports reveal new insights upon the presence of long-lived memory NK cells with enhanced responsiveness and CD16-dependent functional capability, which maintain well the functional and phenotypic signatures of the freshly isolated counterpart after in vitro expansion and thus inspire novel NK cell-based interventions against cancer [12,13].

In recent years, due to the deficiency of current cancer therapies as well as tremendous clinical demands for ameliorating patients with recurrent or refractory tumors, the innate cytotoxic NK cell-based cancer immunotherapies, including adoptive NK cell transfer and chimeric antigen receptor-expressing NK cells (CAR-NKs), are recognized as the cutting-edge immunotherapeutic strategies and highly concerned both in numerous preclinical studies and clinical trials upon malignancies [9,14]. Pioneer investigations highlight the conception that NK cells are capable of targeting and eliminating quiescent or non-proliferating cancer stem cells (CSCs), which represents a potentially new strategy to capitalize on the advantaged intrinsic lymphocyte subset [15]. Likewise, under the circumstance of immune homeostasis, NK cells play an indispensable role in the spatio-termporal balance between cancer cell proliferation and elimination, and the accompanied immune manipulations, which collectively reinforce the naturally occurring immunosurveillance with other immune contexture [16]. Similar to CAR-expressing T cells, state-of-the-art updates have enlightened the prospect of CAR-modified NK (CAR-NK) cells in enhancing tumor-specific targeting and cytotoxic efficacy against cancer cells and the resultant tumor escape without causing cytokine storms [17]. Taken together, the autologous or allogeneic NK cell- and CAR-NK cell-based immunotherapy serves as a promising strategy for hematologic malignance and solid tumor management.

In this review, we mainly focus on current advances in NK cell sources, optimization of ex vivo culture conditions, clinical application in tumor immunosurveillance, and the major strategies and challenges of NK cell- or CAR-NK cell-based adoptive immunotherapy in large-scale, clinical-grade cell product preparation and the simultaneous cancer research.

The source of NK cells

Peripheral blood-derived NK (PB-NK) cells

Of the current NK cell sources, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are the dominant ingredient for GMP- or clinical-grade product manufacturing [10]. In general, the autologous or allogeneic lymphokine-induced NK cells take a proportion of peripheral blood cells between 5% and 20%, that is 29% of total circulating lymphocytes instead [10,18]. After a two-week period of ex vivo amplification and activation under sterile environment, the percentage of NK cell counterpart could reach a range of 40%-90% according to the variation of current manufacturing craftsmanship [13,18]. The major advantage of peripheral blood-derived NK cells is that PBMCs can be immediately and conveniently collected in a closed system and prepared after the aseptic apheresis, which collectively helps diminish the potential for NK cell contamination (Table 1). However, even though various methods have been developed for large-scale NK cell preparation from PBMCs, yet the output and stability of production is far from satisfaction due to the otherness of blood donators (e.g., race, gender and age) as well as numerous adverse parameters in the present procedures [13,19].

Table 1.

The source of NK cells

| The Source of NK Cells | Kinds of NK Cells | Specific NK Cell Phenotype | NK Cell Function | Advantages | Drawbacks | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral Blood-derived NKs (PB-NKs) | N/A | high expression of CD16, adhesion molecules (CD2, CD11a, CD18, CD62L), KIRs, DNAM-1, NKG2C, IL-2R, CD57 and CD8 (receptors associated with terminal NK cell Maturation); Expression of CD56, NCRs (NKp46 and NKp30), and NKG2D | balance of receptor signaling (KIR, NCR and FC); (TRAIL) receptor is central to NK cell-mediated apoptosis; ADCC via CD16, which binds to the Fc of IgG Ab | high cytotoxic of resting PB-NK cell; expression of CD57, an activation marker associated with terminal differentiation of NK cells | low number of NK cells in PB; a log more T-cells in PB relevant to GVHD; lower expression of CXCR4; absent or present in minimum of NK-cell progenitors | [41,75,76] |

| NK Cell Lines | NK-92 | LGL- lymphoma; CD16- | IL-2-dependent; high cytotoxic without ADCC (++) | obtained conveniently; the only cell line product approved in clinical treatment | Irradiation before injection and potential for tumorigenesis in vivo | [77,78] |

| NK-YS | NK-nasal lymphoma; CD2+, CD5+, CD7+, CD25+, CD56+, CD16- and CD95+ | IL-2-dependent; High cytotoxic against K562 and Jurkat cells without ADCC (+) | obtained conveniently; benefit biological studies of EBV-associated nasal angiocentric NK cell lymphoma/leukemia | safety for clinical remains to be verified | [79] | |

| NKL | LGL- leukemia; CD2+, CD16+, and CD95+ without expression CD57 | IL-2-dependent; high cytotoxic (++) | N/A | N/A | [80,81] | |

| NKG | LGL- leukemia: CD16-, CD27-, CD3-, αβTCR-, γδTCR-, CD4-, CD8-, CD19-, CD161-, CD45+, CXCR4+, CCR7+, CXCR1-, and CX3CR1- | IL-2-dependent; high cytotoxicity depended on the presence of NKG2D and NKp30 (+++) | exhibited strong cytotoxicity against human primary ovarian cancer cells in vitro | without proliferation in vivo | [82] | |

| KHYG-1 | LGL- lymphoma; CD1-, CD2+, surface CD3-, cytoplasmic CD3ε+, CD7+, CD8α +, CD16-, CD25-, CD33+, CD34-, CD56+, CD57-, CD122+, CD132+, and TdT- | IL-2-dependent; high cytotoxicity without ADCC (++) | from NK-cell malignancy and obtained conveniently | safety for clinical remained to be verified | [83] | |

| SNK-6 | NK-nasal lymphoma; CD2 (Leu5b)+, CD3 (Leu4)-, CD20-, CD45RO+, EBER-1+, CD3ε+, CD16- | IL-2 dependent; cytotoxicity not be tested | N/A | N/A | [84] | |

| IMC-1 | LGL- leukemia; CD56+, CD2+, CD11a+, CD38+ CD16+ (lost after 7-day culture), CD8+ (lost after 28-day culture) and HLA-DR+ | IL-2 dependent; high cytotoxicity and lyses target cells and antibody-independent (+) | N/A | N/A | [85] | |

| Umbilical Cord Blood-derive NKs (UCB-NKs) | N/A | similar levels of CD56, NCRs (NKp46 and NKp30), and NKG2D but a low expression of CD16; high expression of inhibitory receptor NKG2A, an immature phenotype | enhanced cytotoxicity by activation with cytokines such as IL-2 or IL-15 or the combination of IL-15 with IL-2 or IL-18 | directly applicable to NK cell-directed alloreactivity; high expression of CXCR4; a log few T-cells in UCB; naive, minimizes GVHD; rapidly reconstitute after CBT | reduced cytotoxicity against K562 cells compared to PB NK cells; low numbers and immaturity of UCB NK cells | [75,76] |

| Placental Blood-derive NKs (P-NKs) | p-NK | a distinct miRNA profile; CD56+, CD16+, KIR2DL2/3+, NKp46+, NKp30+, 2B4+ and CD94+ | Comparable cytotoxicity against K562 at various E:T ratio compared to UCB-NK | rich source of pNK cells and be readily obtained from Combo units | low cytolytic activity due to impaired lytic immunological synapse formation | [25] |

| decidual NK (dNK) cells | KIR and KIR2D recognized HLA-C; KIR2D at higher frequency than PB-NKs | contribute to the success of pregnancy | N/A | N/A | [86] | |

| Stem Cell-derived NK Cells (SC-NKs) | human inducible pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) | highly similar phenotypes compared to PB-NKs, except for high expression of NKG2A in iPSC-NK cells; low expression of KIR | effective killing of both HLA-deficient and HLA-sufficient targets including K562, SKOV-3, and SW480; improved activity against ovarian cell lines in vivo | a resource to produce unlimited numbers of NK cells; differentiated from own cells, with minimal immune rejection | complex process of induction; the concern of clinical effectiveness and safety | [87] |

| human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) | inhibitory and activating receptors typical of mature NK cells, such as KIR, NCR CD94+, NKG2A and CD16+ | direct cell-mediated cytotoxicity and Ab-dependent cellular cytotoxicity; up-regulate cytokine production by activated hESC-derived NK cells | a more homogeneous and competent population of effector cells compared with UCB-NK cells, with potent ability to kill human tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo | limited by their potential to evoke an allogeneic immune response, like as other cells used for clinical transplantation | [35,88] |

NK cell lines

During the years, a variety of NK cell lines have been consecutively established, which are recognized as potentially ideal candidates for good manufacturing practices (GMP)-grade NK cell preparation (Table 1). Of them, only the human NK-92 cell line, derived from a patient with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, has revealed safety and efficiency in treatment of patients with advanced renal cell cancer and melanoma [18,20]. Hence, large-scale homogeneous NK-92 cells could be conveniently and reproducibly expanded from the GMP-compliant cryopreserved master cell bank without cost-intensive NK cell purification methods as well [21]. Even so, the well-established and thoroughly standardized clinical-grade NK-92 cells still require irradiation before in vivo transplantation due to the intrinsic nature of the allogeneic tumor cell line [20].

Umbilical cord blood-derived NK (UCB-NK) cells

For decades, fundamental and clinical studies have enlightened the therapeutic prospects of umbilical cord blood (UCB) transplantation in remission of patients with malignant tumors and nonmalignant diseases due to their low immunogenicity (Table 1) [22]. For instance, preliminary studies upon UCB-derived HSCs and the accompanied cellular engineering have been demonstrated safe and capable of triggering potent antitumor reactions, especially for those recipients with human leucocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch [23,24]. Of the UCB counterparts, the content of NK cells is less than 5%, and more than 60% of them belong to the CD3-CD56+CD16+ subset whereas less than 40% are CD3-CD56+CD16- cells instead. Despite UCB-NKs exhibit inferior baseline cytotoxicity when compared with other sources, yet the occasional issues could be largely overcome by subsequent stimulation with cytokine cock-tail [23]. Above all, the unique biological properties of UCB-NK cells, including vigorous cellular vitality and cytolytic activity, could precipitate enhanced anticancer activity and make UCB-NK cells an alternative source for NK cell-based immunotherapy towards hematologic malignancies and multiple solid tumors.

Placental blood-derived NK (P-NK) cells

As mentioned above, the limitation of ex vivo expansion potential of PB-NK cells and UCB-NK cells restricts their therapeutic potential in large-scale clinical application [25]. Distinguish from those in peripheral blood or umbilical cord blood, the content of NK cells in placenta-derived total mononuclear cells (TNC) is much rare with a percentage of less than 2% [25]. State-of-the-art renewal has indicated the potential strategies for efficiently generating clinical-grade NK cells from placenta perfusate (P-NK) after a 3-week’s expansion in culture (Table 1). For instance, Kang et al reported the generation of nearly one billion CD3-CD56+ NK cells per placenta with a dramatic increase in anti-tumor cytolytic activity as well as elevated expression of multiple surface markers (e.g., NKG2D, NKp46, and NKp44), which was comparable to PB-NK or UCB-NK cells utilized in clinical applications [25].

Stem cell-derived NK (SC-NK) cells

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and human inducible pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), possess self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation potential [26], and thus have emerged as an excellent candidate for exploring embryonic development and generating functional cells including NK cells [27-29]. In contrast to those primary NK cells derived from healthy donators or tumor patients including the abovementioned PB-NK cells, UCB-NK cells and P-NK cells with donor variability and heterogeneity, hPSC-derived NK (hPSC-NK) cells are more homogeneous and convenient for large-scale industrial production and genetically engineering for individualized treatment as well as NK cell development and function studies (Table 1) [30,31]. For instance, Zhu et al and Lachmann et al took advantage of a two-stage culture system for CD34+CD45+ hematopoietic progenitor cell and the subsequent clinical-scale CD45+CD56+ NK cell generation, respectively [32-34]. Remarkably, Li and the colleagues successfully utilized human iPSCs for NK cell generation, and in particular, the derived NK cells with novel CAR4 transduction were able to specifically target tumor cells in an antigen-specific manner for improving (NOD-SCID IL2Rγnull) NSG mice survival in an ovarian cancer xenograft model, which provided standardized and targeted “off-the-shelf” CAR-NK cells for anticancer immunotherapy [29]. What’s more, both the in vitro and in vivo evidences have conformably indicated that hPSC-derived NK cells with high cytotoxicity against tumors of different origins [32,35]. These inspiring advances upon clinical-scale derivation of NK cells from hPSC-NK cells provide an unlimited and alternative source of NK cells for off-the-shelf replacement therapies [32].

Ex vivo persistence and activation

Feeder cell stimulation

Feeder cells have been wildly applied in facilitating the proliferation and activation of seeding cells by providing a microenvironment and secreting numerous cytokines. Importantly, ex vivo cocultivation of NK cells with autologous accessory niche cells or growth-inactivated feeder cells are splendid strategies for NK cell expansion and activation [12]. For instance, the cocultured non-NK monocytes or irradiated PBMCs or Epstein-Barr virus-transferred lymphoblastoid cell line (EBV-LCLs) could serve as feeder cells by providing a stimulatory signal for NK cell activation and proliferation, which also indicated the rationale of coculturing with feeder cells including direct cell-to-cell contact and humoral signals (Table 2) [18,36,37]. Likewise, the responsiveness as well as cytotoxicity of NK cells against tumor cells could also be dramatically elevated by application of feeder cells, such as allogeneic irradiated K562 cells, monocytes and genetically engineered cell lines with specific membrane-bound forms of ligand overexpression (e.g., IL-15, 4-1BB ligands) [38,39]. For instance, Lapteva et al successfully produced nearly 2 billion functional NK cells from 1.5×108 CD3-CD56+ NK cells within 8-10 days of coculture by utilizing an engineered K562 cell line with interleukin (IL)-15 and 4-1 BB Ligand (BBL) (K562-mb15-41BBL) co-expression to simulate NK cells in novel cell culture flasks (G-Rex) [39].

Table 2.

Ex vivo persistence and activation of NK cells

| Protocol Features | Culture System | Source of NK cells | Presence of serum | NK-cell product | Education Term | NK Cell Expansion and Purity | NK Cell Phenotype | NK Cell Function | Setting | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeder Cell Education | irradiated and activated autologous PBMCs as feeder cells | peripheral blood from 10 healthy donors | 10% autologous plasma or 5% human AB serum in AIM-V media | NK cells purified using a 2-step MACS System (CD3 depletion, then CD56 enrichment) were cultured in 24-well plates at 2*105 cells/mL with or without irradiated autologous feeder cells at a ratio of 1:20 (NK: feeder) supplemented with rhIL-2 and OKT3 | culturing for 5 days, harvest, resuspended with rhIL-2 (1,000 U/ml), transfer to bigger plate/flask culturing up to 16-18 days | 224-1200-fold expansion; with a purity of 94.9% | up-regulation of CD132, NKG2D, NKp30, NKp44, TRAIL, and DNAM-1; NKp80 levels decreased | enhanced cytotoxicity against K562 cells and ADCC | In vitro | [89] |

| irradiated EBV-LCLs as feeder cells | umbilical cord blood | 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum in X-VIVO media | 106 Immunomagnetic depletion of CD3+ cells cultured with a 1:20 ratio of TNCs to EBV-LCL feeder cells in media containing IL-2 | Culture medium containing IL-2, added every 2 days for up to 4 days of cell culture | 17.4*106,430*106, 6092*106 CD56+ cells obtained on d14, d21, and d35, respectively; CD56+ CD3- NK cells range 75-89% on d14 | up-regulation Of CD161, LFA-1, CD69, NKG2D, NKp30, NKp44, NKp80, NKp46 | highly cytotoxic against K562 | In vitro | [37] | |

| Cytokine Cocktail | peripheral blood and umbilical cord blood | Complete Serum-free Stem Cell Growth Media (SCGM) | CD56+ NK cells, purified with an NK isolation kit, stimulated with 100 Gy irradiated K562 (modified mIL21, 41BBL) | 14 days | the median NK cell expansion was 2222-fold (range 564-7370) | expression of T-bet, CXCR3, NKG2A,NKG2D, Granzyme B, CD16, NKp46, DNAM, NKp30, CD69 | cytotoxicity assessed by coculturing with 51Cr-labeld CLL, Raji and K562 targets | In vitro | [90] | |

| peripheral blood | 5% heat-inactivated human fresh frozen plasma in X-VIVO 10 media | CD3 depleted and CD56 enriched, purified NK cell products were activated in vitro by IL-2 in bags and flasks | 12 days | from 1*107 cells to 7.59*108 cells CD56+ CD3- cells with both purity and viability of 94% | up-regulation of CD69, NKG2D, and NCRs; increased NK cells without KIRs | improved cytotoxic activity against leukemia and tumors | GMP | [91] | ||

| IL-15 | peripheral blood | 10% pooled human serum in AIM-V media | isolated with MACS NK Cell Isolation Kit, cultured with IL-15 | 2-5 weeks | purity: 94-99% | enhanced killing via NCRs, DNAM-1 and NKG2D | enhanced cytolysis of lymphoma and rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines | GMP | [92] | |

| IL-2 and IL-15 | peripheral blood | 10% pooled heat-inactivated human AB serum in RPMI1640 | isolated by double depletion (CD3-, CD19-) or by sequential depletion and enrichment (CD3-, CD56+) via CliniMACS, cultured in 75 cm2 flasks | for 1, 2, or 5 days | purity: 75-100% | up-regulation of NKG2A, NKp44, CD69 | high lysis of K562, Daudi cell lines | GMP | [93] | |

| IL-2 and IL-21 | peripheral blood | 10% fetal calf serum in RPMI-1640 medium | sorted for CD3- CD56+ incubated with 50 U/ml IL-2 and/or 20 ng/ml IL-21 | 20 hours | highly purified (> 98%) | up-regulation of CD69, CD25; activation of STAT3 | enhanced cytotoxicity against K562 | GMP | [94] | |

| OKT3 and IL-2 | peripheral blood | 5% human serum in CellGro SCGM serum-free medium | PBMCs cultured in T25 flasks, OKT3 added on first 5 days; 6-21 days added IL-2 and 5% human serum | 20 days | expansion fold: 1625; NK cell purity: 65% | up-regulation of 2B4, CD8, CD16, CD27, CD226, NKG2C, NKG2D, NKp30, NKp44, NKp46, LIR-1 and CXCR3 Downregulation of CCR7 | enhanced cytotoxicity against tumor cell lines and primary MM cells in vitro | GMP | [95] | |

| OKT3, IL-2 and IL-15 | peripheral blood | 5% human AB serum in stem cell growth medium (SCGM) | enriched CD56+ cells mixed with CD56- fraction at 1:1 ratio and cultured in the presence of OKT3, IL-2 and IL-15 for five days and then without OKT3 for 16 more days | 21 days | 90% CD56+ cells | up-regulation of NKp30, NKp44, DNAM-1, NKG2D, and CD11a | kill neuroblastoma cells effectively | GMP | [96] | |

| aCD16mAb, OK432 and IL-2 | peripheral blood | 10% inactivated human plasma in serum-free media | PBMCs cultured with IL-2, OK432 and aCD16mAb for initial activation without OK432 for further culture | 21 days | expansion fold: 637-5,712; NK purity: 79% | up-regulation of NKG2D, NKp44, and CD69; Downregulation of CD16 | increased cytotoxicity against various cancer cell lines | GMP | [97] | |

| anti-CD52, anti-CD3 and IL-2 | peripheral blood mononuclear cells | containing 10% donor plasma and 500 U/mL IL-2 in NKGM-1 medium | 1*106 cells were cultured in 24-well plate coated anti-CD3 and CD52; large-scale cultures in flask and bag | 14 days | from 5.7*109/ml to 8.4*109/ml NK cells, about 600 folds; %NK cell: 65% | expression of NKG2D, CD16, CD244, NKp46, NKp44, KIR2D1 and NKG2A | significant anti-tumor activity in mice injected with human pancreatic cancer cell line BxPC-3 | In vitro | [98] | |

| IL-12, IL-15 and IL-18 | peripheral blood mononuclear cells | 10% human AB serum in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM) | 2*106 cell/mL PBMCs in 24-well plate preactivated for 16-18 hours using IL-12, IL-15 and IL-18; washed out cytokines and cultured for 4 days with IL-2 | 4 days | N/A | up-regulation of CD25, CD62 and CXCR4 | high cytotoxic activity against K562 | In vitro | [99] | |

| Physicochemical Irritation | an automated bioreactor | peripheral blood from healthy donors and myeloma patients | 5% human serum in CellGro SCGM serum-free medium | PBMCs cultured with IL-2 and OKT3 in flasks, cell culture bags and bioreactors | 20 days | expansion fold: 1100 | up-regulation of NKp44 | enhanced cytotoxic capacity against K562 | GMP | [43] |

| NK purity: 53% | ||||||||||

| Industrialized Production and NK Cell Banking | Cultured in bag or flask | peripheral blood, umbilical cord blood or NK-92 cell line | 2.5% to 10% human AB serum in GMP-grade serum-free media | PBMCs or UCBMCs cultured with different cytokines (IL-2, IL-15, IL-21) and antibody (OKT3, CD52 and CD16) | 14-21 days | expansion fold: large | up-regulation of activator receptor | enhanced cytotoxic against tumor cell lines | GMP | [18] |

| NK purity: 30%-90% |

Cytokine cocktail

In contrast to coculture with feeder cells, cytokine cocktail-based NK cell cultivation is more convenience and thus satisfies the large-scale production of standardized NK cell component for clinical purposes. Meanwhile, the ex vivo cultivated NK cells with cytokine addition are reported with pronounced effects of recognizing and eliminating tumor cells, which further enlighten the promising source for NK cell-based clinical application in malignant tumors [12]. For decades, suspension cultivation of NK cells has been intensively explored with multiple cytokine cocktails such as IL-2, IL-7, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18 and IL-21, which are sufficient to boost the NK cell yield modestly before adoptive transfer [10]. For instance, we recently reported the high-efficient generation of PB-NK cells with preferable cell vitality and enhanced cytotoxicity by combining IL-2, IL-15 and IL-18 [13]. State-of-the-art renewal has prompted the selection of the individual cytokine combination for NK cell subpopulation survival, proliferation, activation, distribution and function in terms of cytotoxic potential and cytokine production (Table 2). For instance, numerous clinical trials as well as fundamental studies have indicated the addition of interleukin 2 (IL-2) in mobilization of NK cells in vivo and expansion of NK cell population in vitro, whereas IL-15 and IL-21 have been variably used instead and IL-15-stimulated NK cells reveal promising curative effect against solid tumors [17,36,40]. It’s worth noting that the combination of IL-12 with IL-15 and IL-18 is competent for a particularly attractive population of memory-like NK cells endowed with advantaged longevity and prolonged effector function [10,41,42]. The rationale is that cytokines are adequate for increasing NK cell responsiveness upon tumor cells with corresponding ligands by stimulating the expression of various activating receptors and costimulatory molecules [12,42].

Physicochemical irritation

In addition to the aforementioned feeder cell- or cytokine-based culture strategies, a sequence of auxiliary measures have been developed to facilitate NK cell ex vivo expansion and activation. For example, Sutlu and the colleagues took advantage of a closed, automated, sterile, large-scale bioreactor consisting of an assorted bag on a heated rocking or static platform under feeder-free current GMP conditions to derive PB-NK cells from both healthy donors and myeloma patients. Strikingly, an average of 9.8×109 NK cells with a purity of 38% were generated after a 21-days’ stimulation, which indicated the potential of physicochemical irritation for large-scale, clinical-grade, feeder-free generation of highly active NK cells for adoptive tumor immunotherapy (Table 2) [43]. Further studies on the underlying mechanism demonstrated that culture vessels were suffice to facilitate NK cell yield and cytolytic function towards tumor cells [43].

Industrialized production and NK cell banking

With the aid of novel culture strategy development, large-scale ex vivo purification and expansion of clinical-grade NK cells under GMP conditions could become available (Table 2). For the purpose, transfer of the abovementioned protocols to clinical-grade generation of NK cells as well as improve the freezing conditions for maintaining cell vitality, will finally help the autologous or allogeneic NK cells necessitate adaptation of GMP conditions and enhance the curative option in regenerative medicine [44]. Meanwhile, numerous preclinical studies as well as clinical trials have been conducted to explore the potential of NK cell-based therapy for malignant tumors by culturing NK cells with clinical-grade reagents under GMP conditions [18]. For example, Spanholtz et al reported the generation of clinical doses of GMP-grade NK cells with the characteristics of high purity, sterility and potency, which would significantly meet benchmarks for NK-cell immunotherapeutic products [36,45]. Another consideration in NK cell manufacture is that GMP-grade serum-free medium such as the commercial AIMV media (Life Technologies, USA), X-VIVO media (BioWhittaker, Belgium) and SCGM media (CellGenix, Germany) supplemented with 2.5-10% human AB serum [46]. These studies suggest the manufacture of clinical-grade NK cells by establishing a public cell bank, which will efficaciously benefit the large-scale generation of standardized cell sources for oncological surveillance. However, it’s difficult to assess the exact strengths and weaknesses of the existing manufacturing techniques due to the variation of culture materials, conditions, technologies and manipulations [18]. Above all, the deficiency of systematic characterization and precise evaluation of NK cells largely hinders the large-scale preparation of industrialized production for clinical applications [18]. In addition, on account of the heterogeneity of NK cells, there’s also an urgent need to identify suitable NK cell subsets for further clinical-grade expansion and specific CAR-NK cell manufacture as documented by clarification of a reported CD94/NKG2C+FcεRIγ- long-lived or NKG2C+ “memory” NK cell subset [12,17].

NK cells in cancer immunosurveillance

Hematological malignancies

Besides the direct or indirect roles in eliminating intracellular pathogens, NK cells play a pivotal role in cancer immunosurveillance (Table 3) [47]. In the 1980s, NK cells were first implicated in cancer immunosurveillance such as X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome and Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, in which the NK cell dysfunction was associated with a higher incidence of tumors [11,48,49]. Similarly, Activation of CD70 reverse signaling in NK cells upon CD27-expressing malignant B cells was demonstrated with better outcome of lymphoma immunosurveillance [50]. In general, NK cells turned into frequently dysfunctional in various tumor patients by abnormally disabling the NK cell activating receptors and downregulating their affinity during antitumor response [12]. Gattazzo et al and Bouis et al further reported the involvement of inhibitory KIR3DL1 receptor and stimulator of interferon genes (STING) deficiency with NK-type lymphoproliferative disease of granular lymphocytes and NK cell developmental defect-associated hypogammaglobulinemia, respectively [51,52]. Very recently, a clinical study upon chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) by Bryce and his colleagues clarified that NK cell reduction as well as abnormally upregulated genes (HIF-1α, GATA-1, PU.1, and GATA-2) was implicated in bone marrow hematopoietic dysfunction and a deficiency recapitulated in blood, which collectively provided molecular insight into the etiology and basis of the complex immunodeficiency status in CLL [53].

Table 3.

NK cell application in cancer treatments

| Malignancies | The Kinds of Diseases | Source of NK cells | Ex Vivo Expansion before in vivo Infusion | Purity of Infused NK Cells | Dosage of Infused NK Cells | Clinical Outcomes | Clinicaltrial.gov no./EudraCT no./UMIN no. | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematological Malignancies | chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) | allogeneic natural killer (NK) cells | CD3-/CD56+ selection; aldesleukin-activated haploidentical NK cells IV over less than 1 hour on day 0 | N/A | donor NK cell dose 1.5-8.0*107/kg | SD: 4 of 6 (66.7%) | NCT00625729 | N/A |

| myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) | allogeneic PBMCs | CD3- and CD19- selection; IL-2 induction | N/A | 6.7*106 cells/kg (1.3-17.6*105) | CR, mCR or PR: 6 of 16 (37.5%); SD: 2 of 16 (12.5%) | 2011-003181-32 | [100] | |

| acute myeloid leukemia (AML) | allogeneic PBMCs | CD3- and CD56+ selection | N/A | 4*106 cells/kg (1.3-5.5*106) | median follow-up: 22.5 months (6-68); DFS: 9 of 16 (56%); DR: 7 of 16 (44%) Median DR: 9 months | NCT00799799 | [101] | |

| lymphoma | allogeneic PBMCs | expansion CD3- selection; IL-2 induction | N/A | 1*106 cells/kg; 3*106 cells/kg; 1*107 cells/kg; 3*107 cells/kg | SD: 7 of 15 (47%) | NCT01212341 | [102] | |

| PD: 8 of 15 (53%) | ||||||||

| aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma | allogeneic PBMCs | CD3- selection; IL-2 induction | 43%±11% | 2.1±1.9*107 cells/kg (0.2-4*107) | CR: 2 of 6 (33%); DR: 2 of 6 (33%) | N/A | [103] | |

| chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) | allogeneic PBMCs | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3-Month CR: 50% | NCT01390402 | N/A | |

| acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) | allogeneic PBMCs | CD3- and CD19- selection or CD34+ selection CD56+ selection; rhIL-2 stimulation | 95% (84-99%) | 1) IL-2 stimulated: 14.6*106 cells/kg (6-45.1*106) | IL-2 stimulated: Median follow-up: 20 months; NR/PR: 7 of 9 (78%) | NCT01386619, NCT00945126 | [104] | |

| 2) Unstimulated: 13.1*106 cells/kg (3.2-38.3*106) | Unstimulated: Median follow-up: 45 months NR/PR: 5 of 9 (59%) | |||||||

| multiple myeloma (MM) | autologous PBMCs | co-culture with K562-mb15-41BB | N/A | 7.5 × 106 cells/kg/cycle | OS: 3 of 5 (60%) | NCT02481934 | N/A | |

| Multiple Solid Tumors | colorectal cancer or gastric carcinoma | allogeneic PBMCs | IL-2 and OK-432 induction, stimulation with FN-CH296 induced T cells expansion | 92.9% (66.3-97.9%) | 1) 5*108 cells/infusion | 4-Month SD: 4 of 6 (67%) | UMIN 000013378 | [105] |

| 2) 1*109 cells/infusion | 4-Month PD: 2 of 6 (33%) | |||||||

| 3) 2*109 cells/infusion | ||||||||

| squamous cell lung cancer | NK-92 cell line; IL-2 induction | expressed high-affinity variant of CD16 | N/A | N/A | N/A | NCT03387111 (QUILT-3.090) | [106] | |

| liver cancer | allogeneic Liver MNCs | IL-2 stimulation | N/A | Small dose: 10-100*106 cells; | N/A | NCT01147380 | N/A | |

| Large dose: 10-100*107 cells | ||||||||

| ovarian and breast cancer | allogeneic PBMCs | CD3- selection | 33% (23.1-55.5) | 2.15*107 cells/kg (8.33-3.94*107) | Ovarian cancer: PR: 4 of 14 (29%); SD: 8 of 14 (57%); PD: 1 of 14 (7%); Breast cancer: SD: 4 of 6; PD: 2 of 6 | N/A | N/A | |

| IL-2 induction | ||||||||

| cholangiocarcinoma | allogeneic PBMCs | combined With Cytokine-induced NK Cells | N/A | N/A | N/A | NCT02482454 | [107] | |

| pancreatic cancer | allogeneic PBMCs | autologous Cytokine-induced NK Cells | N/A | after 2-4 days of chemotherapy, 5*109 autologous cytokine induced NK cells | N/A | NCT03002831 | [108,109] | |

| non-small cell lung cancer | allogeneic PBMCs | expansion IL-15 and hydrocortisone induction CD56 | 92.4% (83.2-98.4%) | 4.15*106 cells/kg (0.2-29*106) | median follow-up: 22 months (16.5-26) | 2005-005125-58 | [105] | |

| median PFS: 7 months | ||||||||

| end-stage and chemotherapy-resistant cancer | NK cell line NK-92 | expansion rhIL-2 induction and irradiation | N/A | starting dose: | Median OS: 15.5 months (3-26), 1-year OS: 9 of 16, 2-year OS: 4 of 16; PR: 2 of 15; SD: 6 of 15; PD: 7 of 15 | N/A | [110] | |

| 1) 1*109 cells/m2; | ||||||||

| 2) 3*109 cells/m2; | ||||||||

| 3) 10*109 cells/m2) | ||||||||

| esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | allogeneic PBMCs | CD3- selection; IL-2 induction and cultured with genetically modified K562 feeder cells for expansion | > 90% | N/A | N/A | N/A | [111] | |

| recurrent or refractory neuroblastoma | allogeneic PBMCs | CD3- selection or CD56+ selection; rhIL-2 stimulation | 95% (84-99%) | 1) IL-2 stimulated: 14.6*106 cells/kg (6-45.1*106) | IL-2 stimulated: Median follow-up: 20 months NR/PR: 7 of 9 (78%) | NCT01386619 | [104] | |

| 2) Unstimulated: 13.1*106 cells/kg (3.2-38.3*106) | unstimulated: median follow-up: 45 months NR/PR: 5 of 9 (59%) |

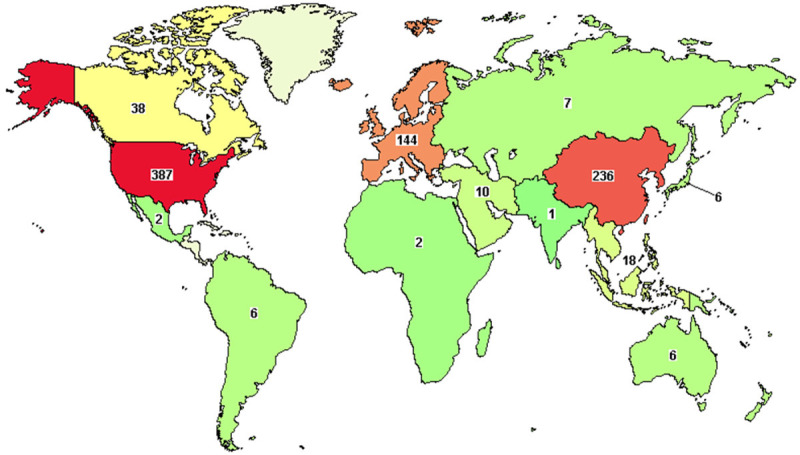

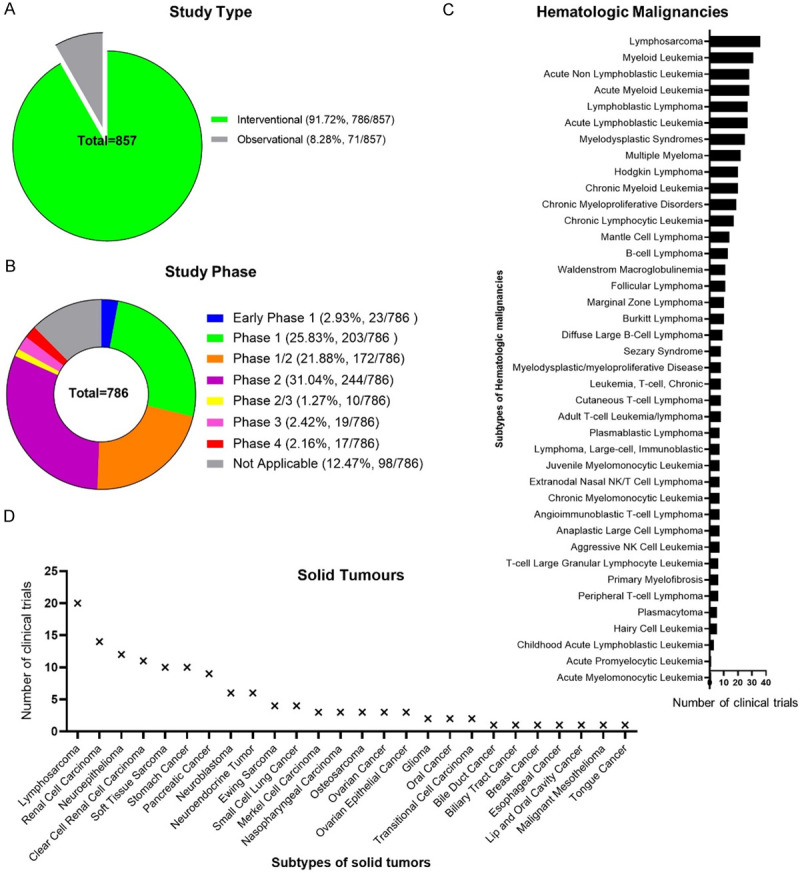

Up to December 31th, 2020, there are 857 interventional and observational clinical trials registered upon NK cells against multiple tumors, and 229 of them focus on leukemia according to the Clinicaltrials.gov website (Figures 1, 2A; Table S1). Most of the interventional studies upon tumors are in phase 1, phase 1/2 and phase 3 stages (Figure 2B). Of the 229 registered studies, a certain type of hematologic malignancies has been reported, such as myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), lymphoma, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) (Figure 2C; Tables S1, S2). Furthermore, among the 31 completed interventional studies with NK cell infusion, most of the trials were upon AML (18/31) and ALL (13/31) with a remission rate of 30~80% (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=natural+killer+cell&cond=Leukemia&recrs=e&age_v=&gndr=&type=Intr&rslt=With&Search=Apply), which is consist with a current review of NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy by Suen and his colleagues [41]. For instance, a pilot study upon 10 patients (0.7-21-year-old) indicated that haploidentical NK cell transplantation was competent to serve an ideal candidate measure for childhood acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remission due to the antileukemic effects without inducing organ toxicity or graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which was further confirmed by another study upon 13 patients with elderly high risk acute myeloid leukemia [54,55]. Moreover, after systemic administration, the alloreactive haploidentical KIR ligand-mismatched donor NK cells could be found in peripheral blood or bone marrow of all evaluable patients, which further manifested the safety and feasibility of NK cell-based cytotherapy for hematological malignancies [54-56]. Simultaneously, it should be noted that the efficacy of the infused haploidentical NK cells upon AML could be reduced by recipient regulatory T cells (Treg), thus depletion of host Treg with IL-2-diphtheria fusion protein (IL2DT) was suffice to further help improve the complete clearance rate of refractory AML [57]. Taken together, these findings collectively suggest that autologous or allogeneic NK cell infusion may play a pivotal role in remission of hematologic malignancies along or as an adjunct to HSC transplantation.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the distribution of NK cell-based clinical trials against tumors worldwide. The number of registered clinical trials upon NK cell-based cytotherapy against tumors according to the ClinicalTrials.gov website (up to December 31th, 2020).

Figure 2.

The overview of NK cell-based clinical trials in tumor immunosurveillance. (A) The percentages of observational and interventional studies of NK cell-based clinical trials; (B) The distribution of study phases among the interventional studies of NK cell-based clinical trials; (C, D) The statistical analyses of the subtypes of registered interventional studies of NK cell-based clinical trials against hematological malignancies (C) and solid tumors (D).

Multiple solid tumors

Even though NK cells belong to innate immunocyte category, yet more and more evidences indicate their potent influence upon innate and adaptive immune host defenses [11,41,47]. Clinical evidences have indicated the inverse correlation of NK cell activity with cancer incidence and prognosis of various solid tumors, especially the high intra-tumoral NK cell infiltration shows perfect association with better outcomes of colorectal cancer, gastric carcinoma and squamous cell lung cancer [58,59]. Remarkably, tumor-infiltrating NK cells derived from tumor patients usually manifest a decreased expression of major activating receptors and resultant decline anti-tumor capacity [10,60]. Recently, Zheng and their colleagues demonstrated the small-sized mitochondrial fragmentation in human liver cancers was correlated with impaired cytotoxicity and NK cell loss, which collectively resulted in tumor evasion of NK cell-mediated surveillance and poor survival of patients with liver cancer [61].

Accordingly, of the registered 73 studies upon solid tumor treatment, a series of recurrent or refractory or metastatic or advanced cancers were administrated with NK cells, including respiratory- (nasopharyngeal cancer, small or non-small cell lung cancer, squamous cell carcinoma), reproductive- (breast cancer, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, fallopian tube carcinoma, primary peritoneal carcinoma, prostate adenocarcinoma), digestive- (tongue cancer, esophageal carcinoma, colorectal cancer, colon cancer, gastric carcinoma, biliary tract cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma), urogenital and endocrine- (pancreatic neoplasms, thyroid carcinoma, urinary bladder neoplasms, bladder carcinoma, prostate cancer, adenocarcinoma), neural- (neurospongioma, neuroastrocytoma, neuroblastoma, brain and central nervous system tumors), kinematic- (Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma) and cutaneous- (cutaneous melanoma, lip and oral cavity carcinoma, adenoid cystic skin carcinoma, adnexal carcinoma) associated clinical trials from phase I to phase III were conducted (Figure 2B, 2D; Tables 3, S1, S3). In particular, lymphosarcoma, renal cell carcinoma and neuroepithelioma are the most intensively studied tumor types among the registered trials (Figure 2D). However, among the 57 completed trials, melanoma, Gastrointestinal neoplasms together with urologic neoplasms are the most common types of NK cell-targeted solid tumors according to the ClinicalTrials.gov records. For instance, a phase II study of allogeneic NK cell-based immunotherapy upon recurrent ovarian and breast cancer corroborated that patients with adoptive transfer of haplo-identical NK cells after lymphodepleting chemotherapy was correlated with transient donor chimerism, and sustained in vivo NK cell augment might be restricted by host lymphocytes or even recipient regulatory T cells (Treg) [62]. However, the definite NK cell-based immunotherapeutic strategies upon solid tumors have not been successful largely due to the immune subversion and dysregulation of NK cell function by various soluble factors (e.g., TGF-β, IDO, PGE2) in the tumor microenvironment [10]. Fortunately, a promising study verified that the synergistic effect of PD1-PDL1 (programmed cell death protein 1-PD1 ligand 1) interaction between NK cells with tumor cells could be blocked by PDL1 monoclonal antibody, whereas ADCC was simultaneously reinforced via the activating CD16 Fc receptor [11]. Therefore, before large-scale clinical utility in cancer surveillance, multifaceted strategies to facilitate in vivo NK cell persistence and vitality together with inhibitory checkpoint blockage or CAR modification are urgently needed.

NK cell engineering and cancer targeting therapy

Despite considerable progress has been achieved in understanding the potent mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies of cancer evading destructive immunity, that is “tumor escape” or “immune evasion in cancer”, yet the crosstalk between tumor metabolism and immunosuppression as well as tumor heterogeneity is still an ultimate frontier in the field [41]. Thus, even though NK cells are deployed for innate immune defense, a certain number of tumor cells with genetic or epigenetic variations are sufficient to bypass the immunological surveillance and reoccupy the basic prerequisite for tumor formation and progression [12]. For instance, the heterogeneous tumor cells could suppress NK cell function by interdicting the NKG2D receptor via dys-upregulating the inhibitory MHC-I molecules or shedding of the tumor-associated complementary NKG2D ligands [63,64].

Therewith, modulation of NK cell-associated receptor expression is of great importance for overcoming immune response inhibition and the resultant tumor escape. Current preclinical and clinical practices have involved the genetically modified NK cells with single, dual or triple-chimeric antigen receptors (CAR) to redirect the specificity of NK cells against fatal cancers (Tables 4, S4) [14,44]. The CAR-modified NK cells are capable of eradicating tumor cells by means of NK cell receptor-dependent, soluble factor secretion-dependent and CAR-dependent mechanisms [14,17,65]. Distinguish from the current CAR-transduced T (CAR-T) cells, CAR-NK cells occupy remarkable advantages including the pattern in recognizing tumor cells, safety in clinical application, few on-target/off-tumor effects or cytokine storm, and their abundant contents in clinical specimens [17,29]. For instance, a number of phase I/II clinical trials have suggested the favorable tolerance and outcomes of cancer patients without GVHD or serious toxicities [17,40]. With the aid of HLA-mismatched anti-CD19 CAR-CB-NK cell infusion, 63.6% (7/11) of the enrolled patients with relapsed or refractory leukemia (non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or CLL) had a complete remission without neurotoxicity, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) or cytokine release syndrome. Strikingly, the transferred CAR-NK cells could expand and persist in vivo for over 12 months [14].

Table 4.

CAR-NK cell application in cancer treatments

| NCT Number | Title | Status | Conditions | Interventions | Phases | Enroll-ment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03692663 | Study of Anti-PSMA CAR NK Cell in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer | Not yet recruiting | Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer | Biological: anti-PSMA CAR NK cells | Early Phase 1 | 9 |

| NCT03692637 | Study of Anti-Mesothelin Car NK Cells in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer | Not yet recruiting | Epithelial Ovarian Cancer | Biological: anti-Mesothelin Car NK Cells | Early Phase 1 | 30 |

| NCT03941457 | Clinical Research of ROBO1 Specific BiCAR-NK Cells on Patients with Pancreatic Cancer | Recruiting | Pancreatic Cancer | Biological: BiCAR-NK cells (ROBO1 CAR-NK cells) | Phase 1/Phase 2 | 9 |

| NCT03940820 | Clinical Research of ROBO1 Specific CAR-NK Cells on Patients with Solid Tumors | Recruiting | Solid Tumor | Biological: ROBO1 CAR-NK cells | Phase 1/Phase 2 | 20 |

| NCT03415100 | Pilot Study of NKG2D-Ligand Targeted CAR-NK Cells in Patients with Metastatic Solid Tumors | Unknown status | Solid Tumors | Biological: CAR-NK cells targeting NKG2D ligands | Phase 1 | 30 |

| NCT03931720 | Clinical Research of ROBO1 Specific BiCAR-NK/T Cells on Patients with Malignant Tumor | Recruiting | Malignant Tumor | Biological: BiCAR-NK/T cells (ROBO1 CAR-NK/T cells) | Phase 1/Phase 2 | 20 |

| NCT03056339 | Umbilical & Cord Blood (CB) Derived CAR-Engineered NK Cells for B Lymphoid Malignancies | Recruiting | B-Lymphoid Malignancies/ALL/CLL/Non-hodgkin Lymphoma | Drug: Fludarabine/Drug: Cyclophosphamide/Drug: Mesna/Biological: iC9/CAR.19/IL15-Transduced CB-NK Cells/Drug: AP1903 | Phase 1/Phase 2 | 36 |

| NCT04623944 | Safety of Intravenous Allogeneic Engineered Natural Killer Cells in Adults with AML or MDS | Recruiting | Relapsed/Refractory AML/AML, Adult/MDS/Refractory MDS | Biological: NKX101-CAR NK cell therapy | Phase 1 | 27 |

| NCT02944162 | CAR-pNK Cell Immunotherapy for Relapsed/Refractory CD33+ AML | Unknown status | AML/AML with Maturation/Acute Myeloid Leukemia Without Maturation/ANLL | Biological: anti-CD33 CAR-NK cells | Phase 1/Phase 2 | 10 |

| NCT03940833 | Clinical Research of Adoptive BCMA CAR-NK Cells on Relapse/Refractory MM | Recruiting | Multiple Myeloma | Biological: BCMA CAR-NK 92 cells | Phase 1/Phase 2 | 20 |

| NCT03692767 | Study of Anti-CD22 CAR NK Cells in Relapsed and Refractory B Cell Lymphoma | Not yet recruiting | Refractory B-Cell Lymphoma | Biological: Anti-CD22 CAR NK Cells | Early Phase 1 | 9 |

| NCT03690310 | Study of Anti-CD19 CAR NK Cells in Relapsed and Refractory B Cell Lymphoma | Not yet recruiting | Refractory B-Cell Lymphoma | Biological: Anti-CD19 CAR NK Cells | Early Phase 1 | 9 |

| NCT04639739 | Anti-CD19 CAR NK Cell Therapy for R/R Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | Not yet recruiting | NHL | Biological: anti-CD19 CAR NK | Early Phase 1 | 9 |

| NCT03824964 | Study of Anti-CD19/CD22 CAR NK Cells in Relapsed and Refractory B Cell Lymphoma | Unknown status | Refractory B-Cell Lymphoma | Biological: Anti-CD19/CD22 CAR NK Cells | Early Phase 1 | 10 |

| NCT02892695 | PCAR-119 Bridge Immunotherapy Prior to Stem Cell Transplant in Treating Patients with CD19 Positive Leukemia and Lymphoma | Unknown status | ALL/CLL/Follicular Lymphoma/Mantle Cell Lymphoma/B-cell Prolymphocytic Leukemia/Diffuse Large Cell Lymphoma | Biological: anti-CD19 CAR-NK cells | Phase 1/Phase 2 | 10 |

| NCT03579927 | CAR.CD19-CD28-zeta-2A-iCasp9-IL15-Transduced Cord Blood NK Cells, High-Dose Chemotherapy, and Stem Cell Transplant in Treating Participants With B-cell Lymphoma | Withdrawn | CD19 Positive/Mantle Cell Lymphoma/Recurrent Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma/Recurrent Follicular Lymphoma/Refractory B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma/Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma/Refractory Follicular Lymphoma | Procedure: Autologous HSC Transplantation/Drug: Carmustine/Drug: Cytarabine/Drug: Etoposide/Biological: Filgrastim/Drug: Melphalan/Biological: Rituximab/Biological: Umbilical Cord Blood-derived Natural Killer Cells | Phase 1/Phase 2 | 0 |

Meanwhile, pioneer investigators have turned to the safety and efficacy of diverse CAR-NK cell preclinical evaluation by utilizing NSG, NOG or patient-derived tumor xenografts (PDX) models, including the CAR-targeting antigens from both hematological disorders (e.g., CD19, CD20, CD22, CD70 and CD276) and solid tumors (e.g., HER-2, EGFR, ErbB2 and GD2) (Table S4) [14,17,50,66,67]. As to the safety and effectiveness evaluation of CAR-NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy, a total amount of 16 clinical trials in early phase 1 or phase1 1/2 have been registered and most of them were launched in the United States and China according to the ClinicalTrial.gov website (Table 4, up to December 31th, 2020). In details, of the 16 interventional trials, ten studies were upon hematologic malignancy (e.g., AML, ALL, CLL, refractory B-Cell lymphoma, multiple myeloma) by mainly targeting CD19, CD22 and CD33, while the other six ones were against solid tumors such as castration-resistant prostate cancer, epithelial ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer and other malignant tumors by targeting PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen), mesothelin, ROBO1 (roundabout guidance receptor 1) and NKG2D (natural killer cell group 2D) instead (Table 4).

Nevertheless, there are certain challenges before large-scale application of CAR-NK cell-based oncotherapy such as the low transduction efficiency and ex vivo expansion rate of CAR-modified NK cells, together with the safety and effectiveness in clinical practices [17]. Above all, novel targets as well as new tools to monitor NK cell activity are needed to counteract NK cell suppressors and invigorate NK cell-based tumor surveillance.

Prospect and implication

Cancer immunotherapy manifests promising potential in inducing durable responses against multiple hematologic and solid malignancies via manipulating the other immune contexture to recognize and attack tumor cells [4,16]. Despite the preferable toxicity profile in cancer immunotherapy than that in other cancer therapies, the potential complications such as cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) and immune-related adverse events (irAEs) still require special management during treatment algorithms for tumor subtypes [4]. For instance, the chimeric antigen receptor-transduced (CAR) T lymphocyte-based cancer immunotherapy often shapes tumor immunogenicity and accompanied with the failure of cancer immunoediting including elimination (e.g., cancer immunosurveillance), equilibrium, and escape [1,4,68]. Distinguish from the aforementioned checkpoint inhibitors and adoptive CAR-T therapy, natural killer cells are adequate for cell immunosurveillance by enhancing antibody and T cell responses, and swiftly removing cancer cells with oncogenic transformation-associated surface biomarker expression [2,69]. Therewith, NK cells are advanced off-the-shelf products for cancer immunotherapy via both direct cytolytic effect and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) as well as paracrine effects [4,39].

The spectacular success of current advances in small-scale prospective studies has highlighted considerable concerns in employing autologous and allogeneic NK cells as a tumor treatment modality [69]. Moreover, the tumor escape due to the resistance of residual cancer cells to endogenous NK cells could be overcome by ex vivo propagation, activation and genetic modification of NK cells [69]. Nevertheless, before large-scale application in tumor immunotherapy, a cohort of core issues in fundamental and clinical studies of NK cells need to be improved and strengthened. Firstly, there’ an urgency of establishing the GMP-grade cryopreserved master cell bank and practical quality control system for subsequent large-scale ex vivo NK cell generation. Secondly, the challenges for identifying more convenient large-scale, GMP-grade, feeder-free manufacturing craftsmanship and systematically dissecting the NK cell biology among various sources. Thirdly, it’s of importance for optimizing the security and feasibility of NK cell-based schemes before clinical administration of malignant tumors. Fourthly, great efforts are needed to manipulate the balance between activating and inhibitory receptor signals as well as modulate NK cell trafficking into solid tumor-associated microenvironment by immune modulating, which will facilitate clinical practices and hold great therapeutic promise [47]. Fifthly, the next generation of NK cell-based products should attach close attention to overcome tumor escape by increasing molecularly targeted issues such as optimized carrier structure, cancer stem cell-specific CAR frameworks (e.g., CD24, CD44) and co-stimulatory molecules, and efficient DNA integration of viral payload and delivery system [70,71]. Above all, in the context of the multipronged cancer immunotherapy is indispensable for the ultimately once and for all overcome of haematological or solid malignancies, including the innate (e.g., dendritic cells) and specific (e.g., T lymphocytes, tumor-infiltrating T cells, genetically engineered CAR-T and TCR-T cells) immune responses, together with immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., PD-1/PD-L1, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4) and routine treatment (e.g., chemotherapy, radiotherapy) [72-74].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the project Youth Fund supported by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2020QC097), Project funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019M661033), Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin City (19JCQNJC12500), the Major Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81330015), National Science and Technology Major Projects of China for “Major New Drugs Innovation and Development” (2014ZX09508002-003), Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (H2020206403), Science and Technology Project of Tianjin (17ZXSCSY00030), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2020J01649), Key project funded by Department of Science and Technology of Shangrao City (2020XGFY05). The co-authors would like to thank the members of precision medicine division of Health-Biotech (Tianjin) Stem Cell Research Institute Co., Ltd. for their assistance.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- NKs

natural killer cells

- ADCC

antibody-dependent cytotoxic cell lysis

- CAR-NK

chimeric antigen receptor-transduced NK

- CSCs

cancer stem cells

- PB-NK

Peripheral Blood-derived NK cells

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- UCB-NKs

umbilical cord blood-derived NK cells

- GMP

good manufacturing practices

- HLA

human leucocyte antigen

- P-NK

placental blood-derived NK cells

- TNC

total mononuclear cells

- hPSCs

human pluripotent stem cells

- hESCs

human embryonic stem cells

- hiPSCs

human inducible pluripotent stem cells

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- ALL

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- MDS

Myelodysplastic Syndromes

- MM

multiple myeloma

- NKG2D

natural killer cell group 2D

- PSMA

prostate-specific membrane antigen

- ROBO1

roundabout guidance receptor 1

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- STING

stimulator of interferon genes

- GVHD

graft-versus-host disease

- IL2DT

IL-2-diphtheria fusion protein

- Treg

regulatory T cells

- PD1

programmed cell death protein 1

- PDL1

PD1 ligand 1

- CAR-T

CAR-transduced T

- MHC-I

major histocompatibility complex class I

- HSCs

hematopoietic stem cells

- PDX

patient-derived tumor xenografts

Table S1

Tables S2-S4

References

- 1.O’Donnell JS, Teng MWL, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting and resistance to T cell-based immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16:151–167. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Y. Cancer immunotherapy: harnessing the immune system to battle cancer. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3335–3337. doi: 10.1172/JCI83871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley RS, June CH, Langer R, Mitchell MJ. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:175–196. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0006-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy LB, Salama AKS. A review of cancer immunotherapy toxicity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:86–104. doi: 10.3322/caac.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Aquino MT, Malhotra A, Mishra MK, Shanker A. Challenges and future perspectives of T cell immunotherapy in cancer. Immunol Lett. 2015;166:117–133. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiessling R, Klein E, Wigzell H. “Natural” killer cells in the mouse. I. Cytotoxic cells with specificity for mouse Moloney leukemia cells. Specificity and distribution according to genotype. Eur J Immunol. 1975;5:112–117. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830050208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vivier E. What is natural in natural killer cells? Immunol Lett. 2006;107:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freud AG, Mundy-Bosse BL, Yu J, Caligiuri MA. The broad spectrum of human natural killer cell diversity. Immunity. 2017;47:820–833. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodgins JJ, Khan ST, Park MM, Auer RC, Ardolino M. Killers 2.0: NK cell therapies at the forefront of cancer control. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:3499–3510. doi: 10.1172/JCI129338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillerey C, Huntington ND, Smyth MJ. Targeting natural killer cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1025–1036. doi: 10.1038/ni.3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morvan MG, Lanier LL. NK cells and cancer: you can teach innate cells new tricks. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:7–19. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2015.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capuano C, Battella S, Pighi C, Franchitti L, Turriziani O, Morrone S, Santoni A, Galandrini R, Palmieri G. Tumor-targeting anti-CD20 antibodies mediate in vitro expansion of memory natural killer cells: impact of CD16 affinity ligation conditions and in vivo priming. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1031. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu M, Meng Y, Zhang L, Han Z, Feng X. High-efficient generation of natural killer cells from peripheral blood with preferable cell vitality and enhanced cytotoxicity by combination of IL-2, IL-15 and IL-18. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;534:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu E, Marin D, Banerjee P, Macapinlac HA, Thompson P, Basar R, Nassif Kerbauy L, Overman B, Thall P, Kaplan M, Nandivada V, Kaur I, Nunez Cortes A, Cao K, Daher M, Hosing C, Cohen EN, Kebriaei P, Mehta R, Neelapu S, Nieto Y, Wang M, Wierda W, Keating M, Champlin R, Shpall EJ, Rezvani K. Use of car-transduced natural killer cells in CD19-positive lymphoid tumors. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:545–553. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luna JI, Grossenbacher SK, Murphy WJ, Canter RJ. Targeting cancer stem cells with natural killer cell immunotherapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2017;17:313–324. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2017.1271874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galon J, Angell HK, Bedognetti D, Marincola FM. The continuum of cancer immunosurveillance: prognostic, predictive, and mechanistic signatures. Immunity. 2013;39:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu Y, Tian ZG, Zhang C. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-transduced natural killer cells in tumor immunotherapy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39:167–176. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koepsell SA, Miller JS, McKenna DH Jr. Natural killer cells: a review of manufacturing and clinical utility. Transfusion. 2013;53:404–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blum KS, Pabst R. Lymphocyte numbers and subsets in the human blood. Do they mirror the situation in all organs? Immunol Lett. 2007;108:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arai S, Meagher R, Swearingen M, Myint H, Rich E, Martinson J, Klingemann H. Infusion of the allogeneic cell line NK-92 in patients with advanced renal cell cancer or melanoma: a phase i trial. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:625–632. doi: 10.1080/14653240802301872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suck G, Odendahl M, Nowakowska P, Seidl C, Wels WS, Klingemann HG, Tonn T. NK-92: an ‘off-the-shelf therapeutic’ for adoptive natural killer cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65:485–492. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1761-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rocha V, Gluckman E Eurocord-Netcord registry and European Blood and Marrow Transplant group. Improving outcomes of cord blood transplantation: HLA matching, cell dose and other graft- and transplantation-related factors. Br J Haematol. 2009;147:262–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balassa K, Rocha V. Anticancer cellular immunotherapies derived from umbilical cord blood. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18:121–134. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2018.1402002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunstein CG, Gutman JA, Weisdorf DJ, Woolfrey AE, Defor TE, Gooley TA, Verneris MR, Appelbaum FR, Wagner JE, Delaney C. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy: relative risks and benefits of double umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2010;116:4693–4699. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-285304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang L, Voskinarian-Berse V, Law E, Reddin T, Bhatia M, Hariri A, Ning Y, Dong D, Maguire T, Yarmush M, Hofgartner W, Abbot S, Zhang X, Hariri R. Characterization and ex vivo expansion of human placenta-derived natural killer cells for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2013;4:101. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L, Wei Y, Chi Y, Liu D, Yang S, Han Z, Li Z. Two-step generation of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells from human pluripotent stem cells with reinforced efficacy upon osteoarthritis rabbits by HA hydrogel. Cell Biosci. 2021;11:6. doi: 10.1186/s13578-020-00516-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Wang H, Liu C, Wu Q, Su P, Wu D, Guo J, Zhou W, Xu Y, Shi L, Zhou J. MSX2 initiates and accelerates mesenchymal stem/stromal cell specification of hPSCs by regulating TWIST1 and PRAME. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;11:497–513. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei Y, Hou H, Zhang L, Zhao N, Li C, Huo J, Liu Y, Zhang W, Li Z, Liu D, Han Z, Zhang L, Song B, Chi Y, Han Z. JNKi- and DAC-programmed mesenchymal stem/stromal cells from hESCs facilitate hematopoiesis and alleviate hind limb ischemia. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:186. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1302-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Hermanson DL, Moriarity BS, Kaufman DS. Human iPSC-derived natural killer cells engineered with chimeric antigen receptors enhance anti-tumor activity. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:181–192. e185. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu H, Kaufman DS. An improved method to produce clinical-scale natural killer cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;2048:107–119. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9728-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boiers C, Carrelha J, Lutteropp M, Luc S, Green JC, Azzoni E, Woll PS, Mead AJ, Hultquist A, Swiers G, Perdiguero EG, Macaulay IC, Melchiori L, Luis TC, Kharazi S, Bouriez-Jones T, Deng Q, Ponten A, Atkinson D, Jensen CT, Sitnicka E, Geissmann F, Godin I, Sandberg R, de Bruijn MF, Jacobsen SE. Lymphomyeloid contribution of an immune-restricted progenitor emerging prior to definitive hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:535–548. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knorr DA, Ni Z, Hermanson D, Hexum MK, Bendzick L, Cooper LJ, Lee DA, Kaufman DS. Clinical-scale derivation of natural killer cells from human pluripotent stem cells for cancer therapy. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2:274–283. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu H, Blum RH, Bjordahl R, Gaidarova S, Rogers P, Lee TT, Abujarour R, Bonello GB, Wu J, Tsai PF, Miller JS, Walcheck B, Valamehr B, Kaufman DS. Pluripotent stem cell-derived NK cells with high-affinity noncleavable CD16a mediate improved antitumor activity. Blood. 2020;135:399–410. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lachmann N, Ackermann M, Frenzel E, Liebhaber S, Brennig S, Happle C, Hoffmann D, Klimenkova O, Luttge D, Buchegger T, Kuhnel MP, Schambach A, Janciauskiene S, Figueiredo C, Hansen G, Skokowa J, Moritz T. Large-scale hematopoietic differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells provides granulocytes or macrophages for cell replacement therapies. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4:282–296. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woll PS, Martin CH, Miller JS, Kaufman DS. Human embryonic stem cell-derived NK cells acquire functional receptors and cytolytic activity. J Immunol. 2005;175:5095–5103. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller JS, Oelkers S, Verfaillie C, McGlave P. Role of monocytes in the expansion of human activated natural killer cells. Blood. 1992;80:2221–2229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vasu S, Berg M, Davidson-Moncada J, Tian X, Cullis H, Childs RW. A novel method to expand large numbers of CD56(+) natural killer cells from a minute fraction of selectively accessed cryopreserved cord blood for immunotherapy after transplantation. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:1582–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dalle JH, Menezes J, Wagner E, Blagdon M, Champagne J, Champagne MA, Duval M. Characterization of cord blood natural killer cells: implications for transplantation and neonatal infections. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:649–655. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000156501.55431.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lapteva N, Durett AG, Sun J, Rollins LA, Huye LL, Fang J, Dandekar V, Mei Z, Jackson K, Vera J, Ando J, Ngo MC, Coustan-Smith E, Campana D, Szmania S, Garg T, Moreno-Bost A, Vanrhee F, Gee AP, Rooney CM. Large-scale ex vivo expansion and characterization of natural killer cells for clinical applications. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:1131–1143. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2012.700767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perez-Martinez A, Fernandez L, Valentin J, Martinez-Romera I, Corral MD, Ramirez M, Abad L, Santamaria S, Gonzalez-Vicent M, Sirvent S, Sevilla J, Vicario JL, de Prada I, Diaz MA. A phase I/II trial of interleukin-15--stimulated natural killer cell infusion after haplo-identical stem cell transplantation for pediatric refractory solid tumors. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:1594–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suen WC, Lee WY, Leung KT, Pan XH, Li G. Natural killer cell-based cancer immunotherapy: a review on 10 years completed clinical trials. Cancer Invest. 2018;36:431–457. doi: 10.1080/07357907.2018.1515315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Natural killer cell memory in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:112–123. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sutlu T, Stellan B, Gilljam M, Quezada HC, Nahi H, Gahrton G, Alici E. Clinical-grade, large-scale, feeder-free expansion of highly active human natural killer cells for adoptive immunotherapy using an automated bioreactor. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:1044–1055. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.504770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Becker PS, Suck G, Nowakowska P, Ullrich E, Seifried E, Bader P, Tonn T, Seidl C. Selection and expansion of natural killer cells for NK cell-based immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65:477–484. doi: 10.1007/s00262-016-1792-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spanholtz J, Preijers F, Tordoir M, Trilsbeek C, Paardekooper J, de Witte T, Schaap N, Dolstra H. Clinical-grade generation of active NK cells from cord blood hematopoietic progenitor cells for immunotherapy using a closed-system culture process. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKenna DH Jr, Sumstad D, Bostrom N, Kadidlo DM, Fautsch S, McNearney S, Dewaard R, McGlave PB, Weisdorf DJ, Wagner JE, McCullough J, Miller JS. Good manufacturing practices production of natural killer cells for immunotherapy: a six-year single-institution experience. Transfusion. 2007;47:520–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Terme M, Ullrich E, Delahaye NF, Chaput N, Zitvogel L. Natural killer cell-directed therapies: moving from unexpected results to successful strategies. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:486–494. doi: 10.1038/ni1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roder JC, Haliotis T, Klein M, Korec S, Jett JR, Ortaldo J, Heberman RB, Katz P, Fauci AS. A new immunodeficiency disorder in humans involving NK cells. Nature. 1980;284:553–555. doi: 10.1038/284553a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sullivan JL, Byron KS, Brewster FE, Purtilo DT. Deficient natural killer cell activity in x-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome. Science. 1980;210:543–545. doi: 10.1126/science.6158759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al Sayed MF, Ruckstuhl CA, Hilmenyuk T, Claus C, Bourquin JP, Bornhauser BC, Radpour R, Riether C, Ochsenbein AF. CD70 reverse signaling enhances NK cell function and immunosurveillance in CD27-expressing B-cell malignancies. Blood. 2017;130:297–309. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-12-756585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gattazzo C, Teramo A, Miorin M, Scquizzato E, Cabrelle A, Balsamo M, Agostini C, Vendrame E, Facco M, Albergoni MP, Trentin L, Vitale M, Semenzato G, Zambello R. Lack of expression of inhibitory KIR3DL1 receptor in patients with natural killer cell-type lymphoproliferative disease of granular lymphocytes. Haematologica. 2010;95:1722–1729. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.023358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouis D, Kirstetter P, Arbogast F, Lamon D, Delgado V, Jung S, Ebel C, Jacobs H, Knapp AM, Jeremiah N, Belot A, Martin T, Crow YJ, Andre-Schmutz I, Korganow AS, Rieux-Laucat F, Soulas-Sprauel P. Severe combined immunodeficiency in stimulator of interferon genes (STING) V154M/wild-type mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:712–725. e715. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manso BA, Zhang H, Mikkelson MG, Gwin KA, Secreto CR, Ding W, Parikh SA, Kay NE, Medina KL. Bone marrow hematopoietic dysfunction in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Leukemia. 2019;33:638–652. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0280-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rubnitz JE, Inaba H, Ribeiro RC, Pounds S, Rooney B, Bell T, Pui CH, Leung W. NKAML: a pilot study to determine the safety and feasibility of haploidentical natural killer cell transplantation in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:955–959. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.4590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Curti A, Ruggeri L, D’Addio A, Bontadini A, Dan E, Motta MR, Trabanelli S, Giudice V, Urbani E, Martinelli G, Paolini S, Fruet F, Isidori A, Parisi S, Bandini G, Baccarani M, Velardi A, Lemoli RM. Successful transfer of alloreactive haploidentical KIR ligand-mismatched natural killer cells after infusion in elderly high risk acute myeloid leukemia patients. Blood. 2011;118:3273–3279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller JS, Soignier Y, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, McNearney SA, Yun GH, Fautsch SK, McKenna D, Le C, Defor TE, Burns LJ, Orchard PJ, Blazar BR, Wagner JE, Slungaard A, Weisdorf DJ, Okazaki IJ, McGlave PB. Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer. Blood. 2005;105:3051–3057. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bachanova V, Cooley S, Defor TE, Verneris MR, Zhang B, McKenna DH, Curtsinger J, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Lewis D, Hippen K, McGlave P, Weisdorf DJ, Blazar BR, Miller JS. Clearance of acute myeloid leukemia by haploidentical natural killer cells is improved using IL-2 diphtheria toxin fusion protein. Blood. 2014;123:3855–3863. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-532531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Tokuda K, Nakajo A, Xiangming C, Iwashige H, Aridome K, Hokita S, Aikou T. Clinical impact of intratumoral natural killer cell and dendritic cell infiltration in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2000;159:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Villegas FR, Coca S, Villarrubia VG, Jimenez R, Chillon MJ, Jareno J, Zuil M, Callol L. Prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating natural killer cells subset CD57 in patients with squamous cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2002;35:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pietra G, Vitale C, Pende D, Bertaina A, Moretta F, Falco M, Vacca P, Montaldo E, Cantoni C, Mingari MC, Moretta A, Locatelli F, Moretta L. Human natural killer cells: news in the therapy of solid tumors and high-risk leukemias. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65:465–476. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1744-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheng X, Qian Y, Fu B, Jiao D, Jiang Y, Chen P, Shen Y, Zhang H, Sun R, Tian Z, Wei H. Mitochondrial fragmentation limits NK cell-based tumor immunosurveillance. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:1656–1667. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Geller MA, Cooley S, Judson PL, Ghebre R, Carson LF, Argenta PA, Jonson AL, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Curtsinger J, McKenna D, Dusenbery K, Bliss R, Downs LS, Miller JS. A phase II study of allogeneic natural killer cell therapy to treat patients with recurrent ovarian and breast cancer. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:98–107. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.515582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaiser BK, Yim D, Chow IT, Gonzalez S, Dai Z, Mann HH, Strong RK, Groh V, Spies T. Disulphide-isomerase-enabled shedding of tumour-associated NKG2D ligands. Nature. 2007;447:482–486. doi: 10.1038/nature05768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Urosevic M, Dummer R. Human leukocyte antigen-G and cancer immunoediting. Cancer Res. 2008;68:627–630. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang X, Jasinski DL, Medina JL, Spencer DM, Foster AE, Bayle JH. Inducible MyD88/CD40 synergizes with IL-15 to enhance antitumor efficacy of CAR-NK cells. Blood Adv. 2020;4:1950–1964. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kailayangiri S, Altvater B, Spurny C, Jamitzky S, Schelhaas S, Jacobs AH, Wiek C, Roellecke K, Hanenberg H, Hartmann W, Wiendl H, Pankratz S, Meltzer J, Farwick N, Greune L, Fluegge M, Rossig C. Targeting Ewing sarcoma with activated and GD2-specific chimeric antigen receptor-engineered human NK cells induces upregulation of immune-inhibitory HLA-G. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1250050. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1250050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Han J, Chu J, Keung Chan W, Zhang J, Wang Y, Cohen JB, Victor A, Meisen WH, Kim SH, Grandi P, Wang QE, He X, Nakano I, Chiocca EA, Glorioso Iii JC, Kaur B, Caligiuri MA, Yu J. CAR-engineered NK cells targeting wild-type EGFR and EGFRvIII enhance killing of glioblastoma and patient-derived glioblastoma stem cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11483. doi: 10.1038/srep11483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004;21:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shimasaki N, Jain A, Campana D. NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:200–218. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Imai C, Iwamoto S, Campana D. Genetic modification of primary natural killer cells overcomes inhibitory signals and induces specific killing of leukemic cells. Blood. 2005;106:376–383. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Medrano-Gonzalez PA, Rivera-Ramirez O, Montano LF, Rendon-Huerta EP. Proteolytic processing of CD44 and its implications in cancer. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021:6667735. doi: 10.1155/2021/6667735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]