Abstract

The molecular difference between synchronous and metachronous metastases in colorectal cancer (CRC) remains unclear. Between 2000 and 2010, a total of 492 CRC patients were enrolled, including 280 with synchronous metastasis and 212 with metachronous metastasis. Clinicopathological and molecular features were compared between the two groups. Patients with synchronous metastasis were more likely to have right-sided CRC, poorly differentiated tumors, lymphovascular invasion, advanced pathological tumor (T) and node (N) categories, and liver metastases than those with metachronous metastasis. For right-sided CRC, patients with synchronous metastasis had more lymphovascular invasion and liver metastases than those with metachronous metastasis. For left-sided CRC, patients with synchronous metastasis were more likely to have poorly differentiated tumors, lymphovascular invasion, advanced pathological T and N categories, and liver metastases than those with metachronous metastasis. Regarding the genetic mutations, patients with metachronous metastasis had more mutations in TP53, NRAS, and HRAS and fewer mutations in APC than those with synchronous metastasis; for right-sided CRC, synchronous metastasis was associated with more APC mutations than metachronous metastasis, while for left-sided CRC, metachronous metastasis was associated with more TP53 and NRAS mutations than synchronous metastasis. The 5-year overall survival (OS) rates were significantly higher in metachronous metastasis patients than in synchronous metastasis patients, especially those with left-sided CRC. Multivariate analysis showed that age, sex, lymphovascular invasion, pathological N category, metachronous metastasis, and BRAF and NRAS mutations were independent prognostic factors affecting OS. CRC patients with synchronous metastasis had a worse OS than those with metachronous metastasis and exhibited distinct genetic mutations.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, synchronous metastasis, metachronous metastasis, prognostic factor, genetic mutation

Introduction

In Taiwan, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common cancer type and the 3rd leading cause of cancer-related death [1]. Approximately 15,000 CRC patients are diagnosed and 5,700 died from cancer every year; hence, CRC is a major public health problem. About half of patients ultimately died either due to progression of metastasis at presentation or recurrent disease after treatment. The most common metastatic site is liver, either synchronous or metachrous [5]. With the improvement of surgical techniques in liver surgery and perioperative care, resection of hepatic metastases has become a more feasible and safe treatment modality and provides an opportunity of long-term survival; however, only approximately 25% of patients could meet the criteria for surgery [2]. A multidisciplinary team is required to discuss the optical treatment strategy for the patients with metastatic CR, and improved survival rate is observed by proper patient selection and aggressive metastasectomy [3].

The timing of occurrence of metastatic disease seems to have an impact on prognosis. The five-year survival rate for CRC patients with synchronous metastasis was 3-11%, which was shorter than 12.8-32.4% for those with metachronous metastasis [4-6]. The discrepancy in the definition of synchronous and metachronous metastasis in previous studies may affect the incidence and survival rate of these patients. To date, there is no consensus regarding the definition of the cutoff time for synchronous and metachronous metastasis of CRC, which varies between 0-12 months after initial diagnosis [2-13]. We selected six months as the cutoff time in this study for the following reasons: (1) a cancer staging procedure is performed in some patients after fully recovered and it may take several months, and a duration of six months will ensure adequate staging for these patients; and (2) metastasis within 6 months after surgery probably has tumor behavior similar to that of metastasis at initial diagnosis [2]. In addition, when the cutoff time was over 4 months after initial diagnosis, the survival was significantly better in the metachronous group than the synchronous group [3].

Previous studies have compared the differences between patients with synchronous and metachronous liver disease and revealed no differences in gender [14], tumor location [15], tumor grading and differentiation [15,16], extent of vascular invasion [17]. It is our interest whether tumors with different timing of metastasis have different molecular profiles, which may possibly explain the different prognosis between these two groups. For example, KRAS mutations have been an important factor in predicting the response to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy [18]. BRAF mutations in advanced CRC was associated with a poor prognosis, and BRAF inhibitor monotherapy did not show meaningful therapeutic effect for BRAF-mutant advanced CRC [19]. The KRAS/BRAF mutation status is an important predictor of the treatment response for advanced CRC. There have been few reports investigating the molecular difference between synchronous and metachronous metastasis in CRC patients [12,13]. In the study by Kim et al [12], mutations in major pathway genes, including KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, TP53, APC, and NRAS, were identified, and similar mutational profiles were observed between patients with synchronous and metachronous metastasis. Fujiyoshi et al [13] reported that the concordance rates of KRAS and BRAF mutations were high between primary CRC tumor tissues and metastatic tissues; however, the high concordance rates of these genes where not significantly different between patients with synchronous and metachronous metastases. It seems that the genetic alterations were not significantly different between patients with synchronous and metachronous metastases.

To date, there has been a lack of investigation into the correlation among the mutational profiles, metastatic pattern, and prognosis of CRC patients with synchronous and metachronous metastases. The aim of this study was to compare the differences in the clinicopathological and mutational profiles between synchronous and metachronous metastases in CRC patients.

Materials and methods

Between 2000 and 2010, a total of 492 metastatic CRC patients were identified with available tumor samples in the biobank and were included in this study, including 280 patients with synchronous metastasis and 212 patients with metachronous metastasis. Synchronous metastasis was defined as distant metastasis at diagnosis or within 6 months after diagnosis. The molecular and clinicopathological features were collected. Written informed consent for sample collection was signed by all the 492 patients, and the tumor samples were stored at the biobank of Taipei Veterans General Hospital. The Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital approved the present study.

The exclusion criteria included patients who received preoperative chemoradiotherapy, who did not receive surgical treatment for primary CRC, who did not have available tumor tissue in the biobank, who underwent emergent operations, or died within 30 days after surgery. Right-side CRC was defined as a tumor located from the cecum to the transverse colon, while left-sided CRC was defined as a tumor extending from the splenic flexure to the rectum.

After surgery, patients were followed up every 3 months for the first 2 years and semiannually thereafter. In addition, carcinoembryonic antigen analysis, chest radiography, abdominal sonogram, and computerized tomography if needed were arranged. Proton emission tomography or magnetic resonance imaging was arranged when elevation of carcinoembryonic antigen level without determination of tumor recurrence site. Patients with resectable synchronous or metachronous metastasis received surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil and oxaliplatin). Patients with unresectable metastasis received palliative chemotherapy with FOLFIRI (folinic acid, fluorouracil and irinotecan) or FOLFOX. Targeted therapies such as bevacizumab, cetuximab, and panitumumab were not reimbursed by the Taiwan National Health Insurance Administration before 2010.

DNA extraction and mutational analysis of the 12-gene panel

The extraction of DNA was performed using the QIAamp DNA Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) The 12-gene panel with identification of 139 mutations selected from hotspots was investigated according to the COSMIC database and previous studies [20,21]. As described in a previous report [22], the MassArray method was used to detect the mutations of the 139 hotspots in 12 genes.

Microsatellite instability (MSI) analysis

Five microsatellite markers were used to determine the MSI phenotype according to the international criteria, including D5S345, D2S123, BAT25, BAT26, and D17S250 [23]. MSI-high tumors were defined as samples with 2 or more positive MSI markers, and microsatellite stable (MSS) tumors were defined as samples with 0 or 1 positive MSI marker.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The statistical endpoint for overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of diagnosis until the death date. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to assess the impact of the molecular and clinicopathological features on OS. The clinicopathological features were compared using the Chi-squared and two-tailed Fisher’s exact tests. Numerical values were compared using Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was defined as p value less than 0.05.

Results

Clinicopathological features

Among the 492 CRC patients, 280 patients had synchronous metastasis and 212 patients had metachronous metastasis. In Table 1, patients with synchronous metastasis had more right-sided tumors, poorly diffferentiated tumors, lymphovascular invasion, and advanced pathological T and N categories than patients with metachronous metastasis.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features between synchronous and metachronous metastasis in CRC

| Synchronous metastasis n=280 n (%) | Metachronous metastasis n=212 n (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.547 | ||

| <70 | 131 (46.8) | 105 (49.5) | |

| ≥70 | 149 (53.2) | 107 (50.5) | |

| Sex | 0.252 | ||

| Male | 179 (63.9) | 146 (68.9) | |

| Female | 101 (36.1) | 66 (31.1) | |

| Tumor location | 0.005 | ||

| Right-sided | 93 (33.2) | 46 (21.7) | |

| Left-sided | 187 (66.8) | 166 (78.3) | |

| Tumor differentiation | 0.003 | ||

| Well to moderate | 247 (88.2) | 203 (95.8) | |

| Poor | 33 (11.8) | 9 (4.2) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | <0.001 | ||

| Absent | 156 (55.7) | 164 (77.4) | |

| Present | 124 (44.3) | 48 (22.6) | |

| Pathological T category | <0.001 | ||

| T1 | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.9) | |

| T2 | 5 (1.8) | 19 (9.0) | |

| T3 | 197 (70.4) | 164 (77.4) | |

| T4 | 77 (27.5) | 27 (12.7) | |

| Pathological N category | <0.001 | ||

| N0 | 57 (20.4) | 79 (37.3) | |

| N1 | 79 (28.2) | 64 (30.2) | |

| N2 | 144 (51.4) | 69 (32.5) | |

| MSI status | 0.715 | ||

| MSS | 260 (92.9) | 195 (92.0) | |

| MSI-high | 20 (7.1) | 17 (8.0) |

MSI: microsatellite instability; MSS: microsatellite stable; TNM: tumor, node, metastasis; bold: statistically significant.

In Table 2, for right-sided CRC, patients with synchronous metastasis tended to have lymphovascular invasion more often than patients with metachronous metastasis. For left-sided CRC, patients with synchronous metastasis tended to have poorly differentiated tumors, lymphovascular invasion, and advanced T and N categories more often than patients with metachronous metastasis.

Table 2.

Clinicopathological features of colorectal cancer with synchronous or metachronous metastasis stratified by tumor location

| Variables | Right-sided CRC | Left-sided CRC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Synchronous metastasis n=93 n (%) | Metachronous metastasis n=46 n (%) | P value | Synchronous metastasis n=187 n (%) | Metachronous metastasis n=166 n (%) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 0.768 | 0.782 | ||||

| <70 | 38 (40.9) | 20 (43.5) | 93 (49.7) | 85 (51.2) | ||

| ≥70 | 55 (59.1) | 26 (56.5) | 94 (50.3) | 81 (48.8) | ||

| Sex | 0.768 | 0.259 | ||||

| Male | 53 (57.0) | 25 (54.3) | 126 (67.4) | 121 (72.9) | ||

| Female | 40 (43.0) | 21 (45.7) | 61 (32.6) | 45 (27.1) | ||

| Tumor differentiation | 0.633 | 0.002 | ||||

| Well to moderate | 78 (83.9) | 40 (87.0) | 169 (90.4) | 163 (98.2) | ||

| Poor | 15 (16.1) | 6 (13.0) | 18 (9.6) | 3 (1.8) | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.018 | <0.001 | ||||

| Absent | 61 (65.6) | 39 (84.8) | 95 (50.8) | 125 (75.3) | ||

| Present | 32 (34.4) | 7 (15.2) | 92 (49.2) | 41 (24.7) | ||

| Pathological T category | 0.436 | <0.001 | ||||

| T1 | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.2) | ||

| T2 | 2 (2.2) | 3 (6.5) | 3 (1.6) | 16 (9.6) | ||

| T3 | 68 (73.1) | 35 (76.1) | 129 (69.0) | 129 (77.7) | ||

| T4 | 22 (23.7) | 8 (17.4) | 55 (29.4) | 19 (11.4) | ||

| Pathological N category | 0.443 | <0.001 | ||||

| N0 | 20 (21.5) | 12 (26.1) | 37 (19.8) | 67 (40.4) | ||

| N1 | 28 (30.1) | 17 (37.0) | 51 (27.3) | 47 (28.3) | ||

| N2 | 45 (48.4) | 17 (37.0) | 99 (52.9) | 52 (31.3) | ||

| MSI status | 0.420 | 0.250 | ||||

| MSS | 83 (89.2) | 43 (93.5) | 177 (94.7) | 152 (91.6) | ||

| MSI-high | 10 (10.8) | 3 (6.5) | 10 (5.3) | 14 (8.4) | ||

MSI: microsatellite instability; MSS: microsatellite stable; T: tumor; N: node; bold: statistically significant.

Molecular analysis

In Figure 1, the most common mutated gene in patients with synchronous metastases was KRAS, followed by APC, TP53, and PIK3CA; the most common mutated gene in those with metachronous metastases was KRAS, followed by TP53, APC, and PIK3CA. As shown in Figure 2A, in right-side colon cancer, the most common mutated gene in those with synchronous metastases was KRAS, followed by APC, TP53, and PIK3CA; the most common mutated gene in those with metachronous metastases was KRAS, followed by TP53, APC and PIK3CA. As shown in Figure 2B, in left-sided colon cancer, the most common mutated gene in those with synchronous metastases was KRAS, followed by APC, TP53, and PIK3CA; the most common mutated gene in those with metachronous metastases was TP53, followed by KRAS, APC, and PIK3CA. In brief, the most common four mutated genes are the same in these two groups, and KRAS was the most common mutated gene. But the order of prevalence of mutated gene differs in these two groups, with more APC and less TP53 mutation in those with synchronous metastases than in those with metachronous metastasis. The order of prevalence of mutated genes did not differ by sideness in synchronous group but not in metachronous group. For left-sided CRC with metachronous metastases, the most common mutated gene was TP53 rather than KRAS in right-sided CRC with metachronous metastases.

Figure 1.

The oncoprint of genetic mutations in CRC with synchronous and metachronous metastases in all CRC patients.

Figure 2.

The oncoprint of genetic alteration in CRC with synchronous and metachronous metastases in right-sided and left-sided CRC. The figures of mutation profiles are shown as follows: (A) right-sided CRC patients and (B) left-sided CRC patients.

As shown in Table 3, patients with synchronous metastasis had more APC mutations and fewer mutations in TP53, NRAS, and HRAS than patients with metachronous metastasis. For right-sided CRC, patients with synchronous metastasis had more APC mutations than patients with metachronous metastasis, while for left-sided CRC, patients with metachronous metastasis had more TP53 and NRAS mutations than patients with synchronous metastasis.

Table 3.

The mutation spectrum of synchronous and metachronous metastasis in CRC stratified by tumor location

| Mutation | All CRC | Right-sided CRC | Left-sided CRC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Synchronous metastasis n=280 n (%) | Metachronous metastasis n=212 n (%) | P value | Synchronous metastasis n=93 n (%) | Metachronous metastasis n=46 n (%) | P value | Synchronous metastasis n=187 n (%) | Metachronous metastasis n=166 n (%) | P value | |

| TP53 | 72 (25.7) | 74 (34.9) | 0.027 | 27 (29.0) | 11 (23.9) | 0.524 | 45 (24.1) | 63 (38.0) | 0.005 |

| APC | 90 (32.1) | 50 (23.6) | 0.037 | 34 (36.6) | 8 (17.4) | 0.021 | 56 (29.9) | 42 (25.3) | 0.331 |

| PIK3CA | 36 (12.9) | 30 (14.2) | 0.677 | 13 (14.0) | 8 (17.4) | 0.597 | 23 (12.3) | 22 (13.3) | 0.789 |

| BRAF | 17 (6.1) | 8 (3.8) | 0.250 | 8 (8.6) | 4 (8.7) | 0.985 | 9 (4.8) | 4 (2.4) | 0.231 |

| KRAS | 121 (43.2) | 82 (38.7) | 0.312 | 47 (50.5) | 22 (47.8) | 0.764 | 74 (39.6) | 60 (36.1) | 0.508 |

| NRAS | 9 (3.2) | 17 (8.0) | 0.018 | 5 (5.4) | 4 (8.4) | 0.454 | 4 (2.1) | 13 (7.8) | 0.013 |

| HRAS | 2 (0.7) | 7 (3.3) | 0.034 | 0 | 1 (2.2) | 0.154 | 2 (1.1) | 6 (3.6) | 0.109 |

| FBXW7 | 10 (3.6) | 10 (4.7) | 0.524 | 2 (2.2) | 3 (6.5) | 0.196 | 8 (4.3) | 7 (4.2) | 0.977 |

| PTEN | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0.431 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0.288 |

| SMAD4 | 11 (3.9) | 6 (2.8) | 0.509 | 5 (5.4) | 3 (6.5) | 0.785 | 6 (3.2) | 3 (1.8) | 0.404 |

| TGFβ | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.4) | 0.731 | 0 | 1 (2.2) | 0.154 | 3 (1.6) | 2 (1.2) | 0.751 |

| AKT1 | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.5) | 0.732 | 0 | 1 (2.2) | 0.154 | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 0.181 |

Bold: statistically significant.

Metastatic patterns

As shown in Table 4, patients with synchronous metastasis had more liver metastases and fewer metastases in the lung and bone than those with metachronous metastasis. For right-sided CRC, patients with synchronous metastasis had more liver metastases than those with metachronous metastasis, while for left-sided CRC, patients with synchronous metastasis had more liver metastases and fewer lung metastases than those with metachronous metastasis.

Table 4.

Metastatic pattern of colorectal cancer stratified by tumor location

| Metastatic pattern | All CRC | Right-sided CRC | Left-sided CRC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Synchronous metastasis n=280 n (%) | Metachronous metastasis n=212 n (%) | P value | Synchronous metastasis n=93 n (%) | Metachronous metastasis n=46 n (%) | P value | Synchronous metastasis n=187 n (%) | Metachronous metastasis n=166 n (%) | P value | |

| Liver | 191 (68.2) | 83 (39.2) | <0.001 | 55 (59.1) | 17 (37.0) | 0.014 | 136 (72.7) | 66 (39.8) | <0.001 |

| Lung | 68 (24.3) | 88 (41.5) | <0.001 | 21 (22.6) | 17 (37.0) | 0.074 | 47 (25.1) | 71 (42.8) | <0.001 |

| Peritoneum | 73 (26.1) | 42 (19.8) | 0.104 | 34 (36.6) | 18 (39.1) | 0.768 | 39 (20.9) | 24 (14.5) | 0.117 |

| Bone | 6 (2.1) | 12 (5.7) | 0.040 | 1 (1.1) | 3 (6.5) | 0.071 | 5 (2.7) | 9 (5.4) | 0.187 |

| Others | 17 (6.1) | 21 (9.9) | 0.115 | 6 (6.5) | 5 (10.9) | 0.364 | 11 (5.9) | 16 (9.6) | 0.185 |

Bold: statistically significant. Some patients had more than one metastatic pattern.

Survival analysis

In Figure 3A, patients with metachronous metastasis had better 5-year OS than patients with synchronous metastasis (53.5% vs. 32.3%, P<0.001). For right-sided CRC, there was no significant difference in 5-year OS between patients with synchronous metastasis and patients with metachronous metastasis (34.6% vs. 43.3%, P=0.266, Figure 3B). For left-sided CRC, patients with metachronous metastasis had a better 5-year OS rate than patients with synchronous metastasis (55.7% vs. 31.0%, P<0.001, Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

The 5-year overall survival (OS) rates were significantly higher in CRC patients with metachronous metastasis than in those with synchronous metastasis (53.5% vs. 32.3%, P<0.001). For right-sided CRC, the 5-year OS rates were not significantly differrent between patients with synchronous metastasis and patients with metachronous metastasis (34.6% vs. 43.3%, P=0.266). For left-sided CRC, patients with metachronous metastasis had a better 5-year OS rate than patients with synchronous metastasis (55.7% vs. 31.0%, P<0.001). The survival curves are shown as follows: (A) all CRC patients (B) right-sided CRC patients, and (C) left-sided CRC patients.

In Table 5, the univariate analysis showed that eight covariates were significantly correlated with OS: age, sex, lymphovascular invasion, pathological N category, MSI status, synchronous metastasis, and BRAF and NRAF mutations. The eight covariates were included in the multivariate analysis, which showed that age, sex, lymphovascular invasion, pathological N category, synchronous metastasis, and BRAF and NRAS mutations were independent prognostic factors affecting OS.

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival in colorectal cancer

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Odds ratio | Confidence interval | P value | Odds ratio | Confidence interval | P value | |

| Age (year) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| <70 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| ≥70 | 1.65 | 1.270-2.130 | 1.79 | 1.361-2.347 | ||

| Sex | 0.034 | 0.018 | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Female | 0.74 | 0.559-0.978 | 0.70 | 0.524-0.942 | ||

| Tumor location | 0.157 | |||||

| Right-sided | 1.00 | |||||

| Left-sided | 0.82 | 0.614-1.082 | ||||

| Lymphovascular invasion | <0.001 | 0.008 | ||||

| Absent | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Present | 1.75 | 1.3389-2.279 | 1.38 | 1.031-1.859 | ||

| Pathological T category | 0.078 | |||||

| T1 | 1.00 | |||||

| T2 | 1.36 | 0.175-10.533 | ||||

| T3 | 1.86 | 0.260-13.293 | ||||

| T4 | 2.67 | 0.368-19.392 | ||||

| Pathological N category | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| N0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| N1 | 1.33 | 0.951-1.865 | 1.06 | 0.751-1.491 | ||

| N2 | 2.04 | 1.487-2.791 | 1.86 | 1.336-2.575 | ||

| MSI status | 0.044 | |||||

| MSS | 1.00 | |||||

| MSI-high | 1.56 | 1.012-2.401 | ||||

| Metastasis | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Synchronous metastasis | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Metachronous metastasis | 0.48 | 0.366-0.617 | 0.47 | 0.356-0.613 | ||

| BRAF mutation | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 2.50 | 1.545-4.057 | 3.32 | 2.024-5.450 | ||

| NRAS mutation | 0.031 | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 1.76 | 1.054-2.934 | 2.30 | 1.434-3.696 | ||

| HRAS mutation | 0.242 | |||||

| No | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 0.51 | 0.162-1.583 | ||||

| TP53 mutation | 0.987 | |||||

| No | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.760-1.322 | ||||

| APC mutation | 0.754 | |||||

| No | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 0.96 | 0.721-1.267 | ||||

T: tumor; N: node; MSI: microsatellite instability; MSS: microsatellite stable; bold: statistically significant.

In Figure 4A, the 5-year post-metastasis survival rates were not significantly different between CRC patients with synchronous metastasis and those with metachronous metastasis (33.0% vs. 32.3%, P=0.822). For right-sided CRC, the 5-year post-metastasis rates were not significantly differrent between patients with synchronous metastasis and patients with metachronous metastasis (34.6% vs. 25.0%, P=0.127, Figure 4B). For left-sided CRC, the 5-year post-metastasis rates were not significantly differrent between patients with synchronous metastasis and patients with metachronous metastasis (31.0% vs. 34.6%, P=0.637, Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

The 5-year post-metastasis survival rates were not significantly different between CRC patients with synchronous metastasis and those with metachronous metastasis (33.0% vs. 32.3%, P=0.822). For right-sided CRC, the 5-year post-metastasis rates were not significantly differrent between patients with synchronous metastasis and patients with metachronous metastasis (34.6% vs. 25.0%, P=0.127). For left-sided CRC, the 5-year post-metastasis rates were not significantly differrent between patients with synchronous metastasis and patients with metachronous metastasis (31.0% vs. 34.6%, P=0.637). The survival curves are shown as follows: (A) all CRC patients (B) right-sided CRC patients, and (C) left-sided CRC patients.

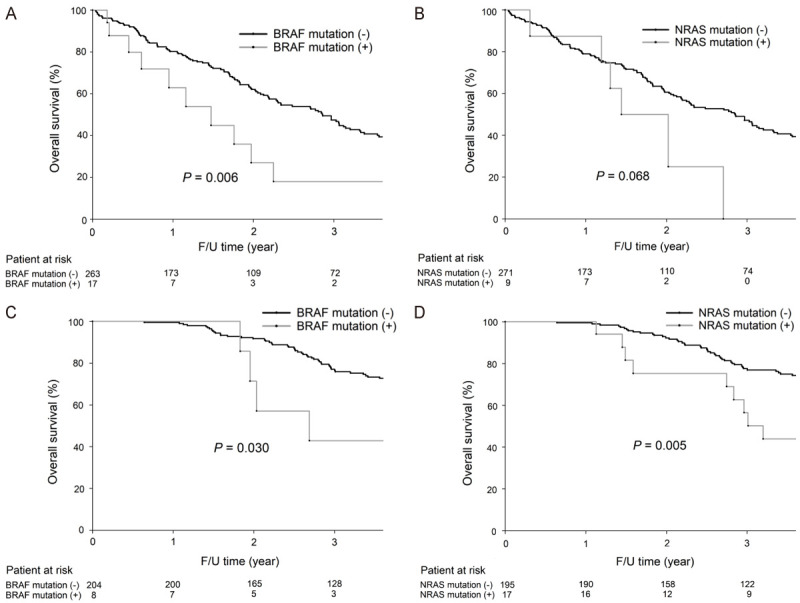

As shown in Figure 5A, for patients with synchronous metastasis, the 3-year OS rates (18% vs. 47.5%, P=0.006) were significantly lower in patients with BRAF mutations than in those without BRAF mutations; the 3-year OS rates were not significantly different between patients with NRAS mutations and those without NRAS mutation (0% vs. 47.2%, P=0.068, Figure 5B). For patients with metachronous metastasis, the 3-year OS rates were significantly lower in patients with BRAF mutations than in those without BRAF mutations (42.9% vs. 77.1%, P=0.030, Figure 5C); the 3-year OS rates (56.5% vs. 77.6%, P=0.005, Figure 5D) were significantly lower in patients with NRAS mutations than in those without NRAS mutations.

Figure 5.

A. For CRC patients with synchronous metastasis, the 3-year OS rates were significantly lower in patients with BRAF mutations than in patients without BRAF mutations (18.0% vs. 47.5%, P=0.006). B. For CRC patients with synchronous metastasis, the 3-year OS rates were not significantly different between patients with NRAS mutations and those without NRAS mutation (0% vs. 47.2%, P=0.068). C. For CRC with metachronous metastasis, the 3-year OS rates were significantly lower in patients with BRAF mutations than in those without BRAF mutations (42.9% vs. 77.1%, P=0.030). D. For metachronous metastatic CRC patients, the 3-year OS rates were significantly lower in patients with NRAS mutations than in patients without NRAS mutations (56.5% vs. 77.6%, P=0.005).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study includes the largest population investigating the genetic alterations between synchronous and metachronous metastasis in CRC patients. The novel finding of the present study is that different genetic mutations exist between synchronous and metachronous metastasis in CRC. In addition, the differences in mutational profiles between synchronous and metachronous metastases are also distinct in right-sided and left-sided CRC.

The major difference between the present study is that patients with metachronous metastasis had more mutations in TP53, NRAS, and HRAS and fewer mutations in APC than those with synchronous metastasis, while no difference in genetic mutations was noted between synchronous and metachronous metastases in other studies [12,13]. In addition, our results demonstrated that synchronous metastasis was associated with more APC mutations in right-sided colon cancer and metachronous metastasis was associated with more TP53 and NRAS mutations in left-sided colon cancer. The reason for the discrepancy between the present study and others might be due to sample size, racial difference, the definition of synchronous and metachronous metastases, and environmental factors.

In the present study, patients with synchronous metastasis had a worse OS rate than patients with metachronous metastasis, especially among those with left-sided CRC. Our result is interesting, and the possible reason is that patients with synchronous metastasis had more advanced pathological T and N categories than patients with metachronous metastasis, especially among those with the left-sided CRC.

Mutations in APC, KRAS, and TP53 were frequently found in primary CRC and were correlated with a higher frequency of liver metastasis [24]. In addition, mutations in APC, TP53, and KRAS were also frequently detected in both primary CRC and lung metastasis tissues [25]. In the present study, for right-sided CRC, synchronous metastasis was associated with more APC mutations and liver metastases than metachronous metastasis; for left-sided CRC, metachronous metastasis was associated with more TP53 and NRAS mutations and more lung metastases than synchronous metastasis. For right-sided CRC, patients with APC mutations had more liver metastases than patients without APC mutations (69.0% vs. 44.3%, P=0.007). For left-sided CRC, compared with patients with none or either TP53 or NRAS mutations, patients with both TP53 and NRAS mutations had a higher frequency of lung metastases (37.5% vs. 10.6%, P=0.015). It was reported that concurrent mutations of TP53 and RAS/BRAF are associated with extrahepatic metastases in CRC [26]. According to our results, it seems that APC mutation may play an important role in liver metastases in right-sided CRC with synchronous metastasis. In addition, concurrent TP53 and NRAS mutations may be associated with lung metastases in left-sided CRC with metachronous metastasis.

Among our 212 patients with metachronous metastasis, 17 patients (8%) had NRAS mutations. Our results showed that for patients with metachronous metastasis, NRAS-mutated CRC was associated with a worse 3-year OS rate than NRAS-nonmutant CRC. It was reported that BRAF and NRAS mutations were correlated with distant metastasis, and BRAF mutation rather than NRAS mutation was correlated with a poorer OS rate in stage I-III CRC [27]. In their study, the number of patients with NRAS mutation (n=7) was too small to investigate the prognostic role of NRAS mutation. The discrepancy between the present study and the study of Guo et al [27] is the patient population and the number of patients with genetic mutations. Since the present study enrolled patients with synchronous and metachronous metastasis and most of them had advanced CRC, the frequency of genetic mutations was higher than that in the study by Guo et al [27], which enrolled patients with stage I-III CRC. Consequently, according to our results, both BRAF and NRAS mutations are prognostic indicators for CRC patients with synchronous or metachronous metastasis. Meta-analysis demonstrated that mutations in BRAF, PIK3CA, NRAS and exons 3 and 4 of KRAS predict resistance to ant-EGFR therapy [28]. Our results might be helpful for evaluation of clinical benefit of anti-EGFR therapy in metastatic CRC.

There are limitations to the present study. This is a retrospective study, and the patients who had metastatic CRC without surgical treatment and available tumor tissue in the biobank were excluded and so selection bias exists. Although a significant difference was noted in some genetic mutations, the patient number is small and the difference in some genetic mutations could not be detected due to low prevalence of mutation. More patients enrolled from different countries and different races are required to validate our findings.

Conclusions

The genetic mutations are distinct between CRC patients with synchronous and metachronous metastasis, and these differences are also observed in patients with different tumor locations. Our results may have clinical impact and remind physicians to be aware of the genetic mutations and the metastatic patterns in the management of CRC patients.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V105C-043, V106C-027, V107C-004), Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (105-2314-B-075-010-MY2), and Taipei City Hospital (10601-62-059, 10701-62-050). The funding body did not play role in the design of the study, and collection, analysis and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan, Republic of China. Cancer Registry Annual Report. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engstrand J, Nilsson H, Strömberg C, Jonas E, Freedman J. Colorectal cancer liver metastases - a population-based study on incidence, management and survival. BMC Cancer. 2018;1:78. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3925-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lan YT, Jiang JK, Chang SC, Yang SH, Lin CC, Lin HH, Wang HS, Chen WS, Lin TC, Lin JK. Improved outcomes of colorectal cancer patients with liver metastases in the era of the multidisciplinary teams. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2459-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manfredi S, Lepage C, Hatem C, Coatmeur O, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Epidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2006;244:254–259. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217629.94941.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan EK, Ooi LL. Colorectal cancer liver metastases - understanding the differences in the management of synchronous and metachronous disease. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39:719–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okholm C, Mollerup TK, Schultz NA, Strandby RB, Achiam MP. Synchronous and metachronous liver metastases in patients with colorectal cancer. Dan Med J. 2018;65:A5524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mekenkamp LJ, Koopman M, Teerenstra S, van Krieken JH, Mol L, Nagtegaal ID, Punt CJ. Clinicopathological features and outcome in advanced colorectal cancer patients with synchronous vs metachronous metastases. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:159–164. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willem H, Jooste V, Boussari O, Romain G, Bouvier AM. Impact of absence of consensual cutoff time distinguishing between synchronous and metachronous metastases: illustration with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2019;28:167–172. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zizzo M, Galeone C, Braglia L, Ugoletti L, Siciliani A, Nachira D, Margaritora S, Pedrazzoli C, Paci M, Lococo F. Long-term outcomes after surgical resection for synchronous or metachronous hepatic and pulmonary colorectal cancer metastases. Digestion. 2020;101:144–155. doi: 10.1159/000497223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong S, Heo JS, Park JY, Choi DW, Choi SH. Surgical resection of synchronous and metachronous lung and liver metastases of colorectal cancers. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2017;92:82–89. doi: 10.4174/astr.2017.92.2.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovaleva V, Geissler AL, Lutz L, Fritsch R, Makowiec F, Wiesemann S, Hopt UT, Passlick B, Werner M, Lassmann S. Spatio-temporal mutation profiles of case-matched colorectal carcinomas and their metastases reveal unique de novo mutations in metachronous lung metastases by targeted next generation sequencing. Mol Cancer. 2016;15:63. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0549-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim KP, Kim JE, Hong YS, Ahn SM, Chun SM, Hong SM, Jang SJ, Yu CS, Kim JC, Kim TW. Paired primary and metastatic tumor analysis of somatic mutations in synchronous and metachronous colorectal cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49:161–167. doi: 10.4143/crt.2015.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujiyoshi K, Yamamoto G, Takahashi A, Arai Y, Yamada M, Kakuta M, Yamaguchi K, Akagi Y, Nishimura Y, Sakamoto H, Akagi K. High concordance rate of KRAS/BRAF mutations and MSI-H between primary colorectal cancer and corresponding metastases. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:785–792. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bockhorn M, Frilling A, Frühauf NR, Neuhaus J, Molmenti E, Trarbach T, Malagó M, Lang H, Broelsch CE. Survival of patients with synchronous and metachronous colorectal liver metastases--is there a difference? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1399–1405. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0508-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai MS, Su YH, Ho MC, Liang JT, Chen TP, Lai HS, Lee PH. Clinicopathological features and prognosis in resectable synchronous and metachronous colorectal liver metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:786–794. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alwan M, Stubbs R. Local recurrence in patients with synchronous or metachronous colorectal liver metastases--is there a difference? N Z Med J. 2005;118:U1631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taniai N, Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Matsumoto S, Mizuguchi Y, Suzuki H, Furukawa K, Akimaru K, Tajiri T. Outcome of surgical treatment of synchronous liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Nippon Med Sch. 2006;73:82–88. doi: 10.1272/jnms.73.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: can testing of tumor tissue for mutations in EGFR pathway downstream effector genes in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer improve health outcomes by guiding decisions regarding anti-EGFR therapy? Genet Med. 2013;15:517–527. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopetz S, Desai J, Chan E, Hecht JR, O’Dwyer PJ, Maru D, Morris V, Janku F, Dasari A, Chung W, Issa JP, Gibbs P, James B, Powis G, Nolop KB, Bhattacharya S, Saltz L. Phase II pilot study of vemurafenib in patients with metastatic BRAF-mutated colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:4032–4038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin JK, Lin PC, Lin CH, Jiang JK, Yang SH, Liang WY, Chen WS, Chang SC. Clinical relevance of alterations in quantity and quality of plasma DNA in colorectal cancer patients: based on the mutation spectra detected in primary tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(Suppl 4):S680–686. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3804-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu YL, Lin CC, Jiang JK, Lin HH, Lan YT, Wang HS, Yang SH, Chen WS, Lin TC, Lin JK, Lin PC, Chang SC. Clinicopathological and molecular differences in colorectal cancer according to location. Int J Biol Markers. 2019;34:47–53. doi: 10.1177/1724600818807164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, Sidransky D, Eshleman JR, Burt RW, Meltzer SJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Fodde R, Ranzani GN, Srivastava S. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joung JG, Oh BY, Hong HK, Al-Khalidi H, Al-Alem F, Lee HO, Bae JS, Kim J, Cha HU, Alotaibi M, Cho YB, Hassanain M, Park WY, Lee WY. Tumor heterogeneity predicts metastatic potential in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:7209–7216. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schweiger T, Liebmann-Reindl S, Glueck O, Starlinger P, Laengle J, Birner P, Klepetko W, Pils D, Streubel B, Hoetzenecker K. Mutational profile of colorectal cancer lung metastases and paired primary tumors by targeted next generation sequencing: implications on clinical outcome after surgery. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:6147–6157. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.10.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Datta J, Smith JJ, Chatila WK, McAuliffe JC, Kandoth C, Vakiani E, Frankel TL, Ganesh K, Wasserman I, Lipsyc-Sharf M. Coaltered Ras/B-raf and TP53 is associated with extremes of survivorship and distinct patterns of metastasis in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:1077–1085. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo F, Gong H, Zhao H, Chen J, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Shi X, Zhang A, Jin H, Zhang J, He Y. Mutation status and prognostic values of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA in 353 Chinese colorectal cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6076. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24306-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Therkildsen C, Bergmann TK, Henrichsen-Schnack T, Ladelund S, Nilbert M. The predictive value of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and PTEN for anti-EGFR treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:852–864. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.895036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]