Abstract

Background

Salvadora persica L. (Toothbrush tree – Miswak; family-Salvadoraceae) grows in the arid-land ecosystem and possesses economic and medicinal importance. The species, genus and the family have no genomic datasets available specifically on chloroplast (cp) genomics and taxonomic evolution. Herein, we have sequenced the complete chloroplast genome of S. persica for the first time and compared it with 11 related specie’s cp genomes from the order Brassicales.

Results

The S. persica cp genome was 153,379 bp in length containing a sizeable single-copy region (LSC) of 83,818 bp which separated from the small single-copy region (SSC) of 17,683 bp by two inverted repeats (IRs) each 25,939 bp. Among these genomes, the largest cp genome size (160,600 bp) was found in M. oleifera, while in S. persica it was the smallest (153,379 bp). The cp genome of S. persica encoded 131 genes, including 37 tRNA genes, eight rRNA genes and 86 protein-coding genes. Besides, S. persica contains 27 forward, 36 tandem and 19 palindromic repeats. The S. persica cp genome had 154 SSRs with the highest number in the LSC region. Complete cp genome comparisons showed an overall high degree of sequence resemblance between S. persica and related cp genomes. Some divergence was observed in the intergenic spaces of other species. Phylogenomic analyses of 60 shared genes indicated that S. persica formed a single clade with A. tetracantha with high bootstrap values. The family Salvadoraceae is closely related to Capparaceae and Petadiplandraceae rather than to Bataceae and Koberliniacaea.

Conclusion

The current genomic datasets provide pivotal genetic resources to determine the phylogenetic relationships, genome evolution and future genetic diversity-related studies of S. persica in complex angiosperm families.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-021-07626-x.

Keywords: Salvadoraceae, Sequencing, Repeat analysis, Divergence, Phylogenomics, InDel, SNP, Chloroplast

Introduction

Salvadoraceae is a small family that comprises three genera, Salvadora Juss (±five species), Azima Lam. (±four species) and Dobera Juss. (two species) [1]. Salvadoraceae contains small trees and shrubs growing in arid environments and widespread worldwide. The main trunk of S. persica is erect or trailing and can grow up to 10 m with a circumference of 3 ft. Tree bark is rough with a brownish color and young branches are greenish [2, 3]. S. persica showed variation in different countries, which may be due to the climatic conditions, anthropogenic activities and water resources [4]. It is native to Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Egypt, Uganda Algeria, India, Zimbabwe and Sri Lanka [5]. S. persica is a non-deciduous, slow-growing perennial halophyte that can grow under extreme dry and saline conditions [6]. The Arabic name of S. persica is Khardal Shajar-el-Miswak. At the same time, in English it is called Mustard tree or Toothbrush tree [7]. For oral hygiene, chewing sticks have been used since 3500 BC by Babylonians. S. persica L. is an economically and medicinally plant with numerous medicinal properties. It has been used in traditional medicine, especially in the Middle East and Eastern Africa [4]. Phytochemically, the S. persica contains a higher proportion of fluorides. In contrast, it has shown considerable prospects for antimicrobial and anticancer due to the presence of benzyl isothiocyanate, alkaloids, salvadoside and salvadoraside, etc. [8].

Though S. persica has been utilized substantially by local communities, taxonomically, the family had suffered a lot due to displacement. It has always been classified as an outsider, dumped in or close to Oleales [9] or Celastrales [10, 11] or either as ‘incerta sedis’ [12]. In the beginning [13], it was placed in an extended order Capparales and later separated the family into distinct order Salvadorales [14]. Using chemical markers, Salvadoraceae was classified early with Capparales (Brassicales) [13, 14] due to custard oil. Later, its association with all mustard oil-producing families was confirmed by various genes phylogeny [15–17]. However, with the advancement in molecular methods, genetic variations have helped solve several taxonomic problems [18]. Up till now, numerous types of molecular markers have been designed, assessed, and categorized into various groups such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based features, simple sequence repeats (SSRs) and inter simple sequence repeats, random amplified polymorphic DNA, single-nucleotide polymorphism, hybridization-based molecular markers, and amplified fragment length polymorphism [19, 20]. Using some of these methods, Salvadoraceae was considered a sister family to Bataceae with strong support. Koeberliniaceae is regarded as a sister to these two families in a clade near core Brassicales. Recent combined molecular and morphological analysis of Brassicales supported this association [21]. Despite their importance of these molecular methods, there are still several disadvantages at certain levels of principles [20]. However, with the current advancements in next-generation sequencing methods and platforms, understanding large-scale genome composition, precisely, chloroplast genome, has shown unprecedented progress in exploring taxonomic and evolutionary challenges to important plant species [22, 23].

The chloroplast is a vital plant organelle in green plants that plays a keycrucialle in plant cells during carbon fixation and photosynthesis [24]. In angiosperms mostly these cp genomes are uniparentally inherited circular DNA molecules ranging from ~ 115 to 165 kb in length [25], and these differences are primarily due to IR contraction/expansion loss [26]. Moreover, in most angiosperms, these genomes are divided into four parts containing one small single-copy (SSC) region, one large single-copy (LSC) region, and two same length inverted repeat regions (IRs) regions [27, 28]. In terms of gene structure and composition, the cp genome is more conserved than the mitochondrial and nuclear genome [29, 30]. Cp genomes are a valuable genetic resource to infer the phylogenetic position of different species due to their highly conserve and non-recombinant nature [31, 32]. Comparatively, it has become an easy and cheap resource to sequence due to recent advancements in next-generation sequencing technology to solve the controversial phylogenetic questions of non-model taxa and infer their phylogenetic position complete cp genome and shared genes [22, 23].

More than 6500 chloroplast genomes are sequenced until now; however, there are still many economically and medicinally important plant species that haves no genomic datasets [33]. Notwithstanding the wide distribution of family Salvadoraceae in arid areas, very little is known about this family genetically. There is no genomic information at the species, genus, or family level. Hence, the current study was aimed to establish genomic datasets for S. persica as well for Salvadoraceae. The present study also characterized the whole cp genome of S. persica and compared it with the 11 available cp genomes from Brassicales. Furthermore, we performed phylogenomic assessment based on the shared genes amongst the 31 cp genomes from order Brassicales.

Results

S. persica chloroplast genome: composition and structure

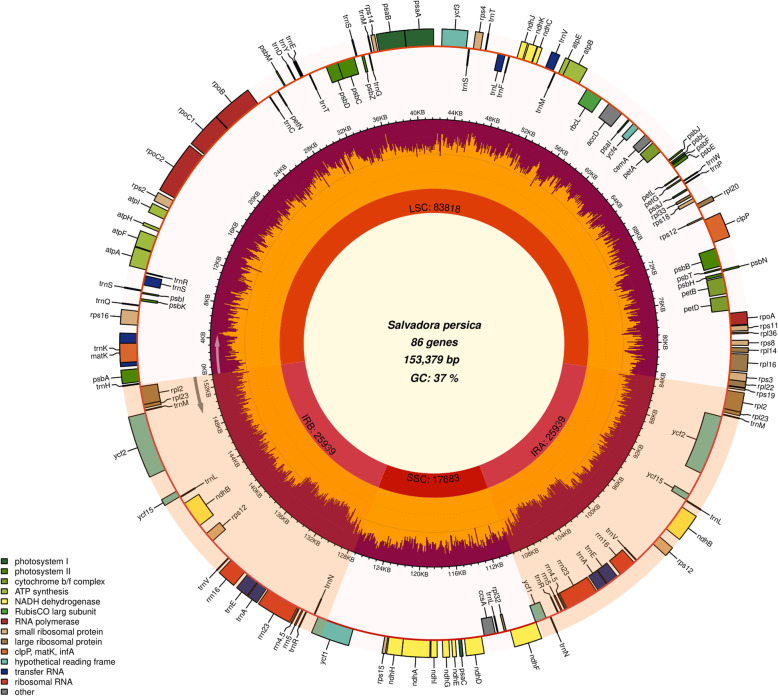

The assembly and detailed bioinformatic analyses showed that the chloroplast (cp) genome size of S. persica is 153,379 bp. It has a distinctive quadripartite structure which consists of LSC (83,818 bp) region, separated from the SSC region (17,683 bp) by two inverted repeats (IRs; 25,939 bp) (Fig. 1; Table 1). The cp genome of S. persica comprises 131 genes, including 86 protein-coding genes (9 large and 12 small ribosomal subunits, 43 photosynthesis-related proteins, four DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and ten genes encoding other proteins), 37 tRNA genes, and eight rRNA genes (Table S1). About 22 genes containing introns were determined in the S. persica cp genome, including 12 protein-coding genes and eight tRNA genes (with one intron), whereas the other two protein-coding genes (ycf3 and clpP) with two introns (Table 2). The matK gene is present in the intronic region of trnK-UUU gene which had the largest intron (2549 bp). Similarly, the ycf15 gene had the smallest intron (295 bp) (Table 3). The trans-spliced gene small ribosomal protein-12 (rps12) is having single intron. Moreover, its five ′ end exon is present in the LSC region, while the three ′ end exon is duplicated in IR region (Fig. 1). Inclusively, the protein-coding, tRNA and rRNA genes contain 47.2, 1.8 and 5.9%, respectively, in the S. persica cp genome. Similar to typical angiosperm cp genomes, the GC composition of tRNA (52.8%) and rRNA (55.3%) is the highest, followed by protein-coding genes (37.4%) in the coding regions. Codon – anticodon characteristic pattern and codon usage of S. persica cp genome is summarized in Table 3. The most frequent amino acid was leucine (10.8%), whereas the least frequent one was cysteine (1.2%). The GC content of the S. persica cp genome is 36.7%, whereas the LSC, SSC, and IR regions’ GC content is 34.6, 30.2, and 42.2%, respectively. Similar results were observed in related species. However, the highest GC contents in the IR regions are due to the high GC contents of eight rRNA genes located in these regions.

Fig. 1.

Genomic map of the S. persica cp genome. The pink part inside the inner green circle indicates the extent of the inverted repeat regions (IRa and IRb; 25,949 bp), which separate the genome into small (SSC; 17,683 bp) and large (LSC; 83,798 bp) single copy regions. Genes drawn inside the circle are transcribed clockwise, and those outsides are transcribed counter clockwise. Genes belonging to different functional groups are color-coded. The red in the inner circle corresponds to the GC content, and the light green corresponds to the AT content

Table 1.

Summary of complete chloroplast genomes

| S. persica | A. tetracantha | A. arabicum | A. thaliana | B. nigra | C. rubella | C. papaya | M. oleifera | R. carnosula | R. cretica | C. limprichtiana | T. hassleriana | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (bp) | 153,379 | 153,415 | 154,234 | 154,478 | 153,633 | 154,601 | 160,100 | 160,600 | 154,328 | 154,188 | 153,746 | 157,688 |

| Overall GC contents | 36.7 | 36.1 | 36.6 | 36.3 | 36.4 | 36.5 | 36.9 | 36.8 | 36.1 | 36.3 | 36 | 35.8 |

| LSC size in bp | 83,818 | 83,841 | 83,401 | 84,170 | 83,552 | 83,990 | 88,749 | 88,563 | 83,463 | 83,274 | 83,293 | 87,509 |

| SSC size in bp | 17,683 | 17,488 | 17,716 | 17,780 | 17,695 | 17,855 | 18,701 | 18,881 | 18,130 | 18,169 | 17,763 | 18,677 |

| IR size in bp | 25,939 | 26,043 | 26,558 | 26,264 | 26,193 | 26,462 | 26,325 | 26,570 | 26,367 | 26,372 | 26,262 | 25,804 |

| Protein coding regions size in bp | 72,281 | 78,288 | 79,482 | 77,925 | 79,881 | 78,489 | 78,636 | 79,881 | 78,708 | 76,734 | 50,010 | 79,755 |

| tRNA size in bp | 2811 | 2784 | 2789 | 2791 | 2790 | 2792 | 2792 | 2739 | 2826 | 2826 | 2623 | 2863 |

| rRNA size in bp | 9052 | 9054 | 8929 | 8929 | 9050 | 9052 | 9050 | 9050 | 9050 | 9050 | 8929 | 9400 |

| Number of genes | 131 | 131 | 128 | 129 | 132 | 130 | 131 | 129 | 130 | 132 | 113 | 131 |

| Number of protein coding genes | 86 | 84 | 83 | 85 | 87 | 84 | 84 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 71 | 85 |

| Number of rRNA | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| Number of tRNA | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 36 | 37 | 37 | 35 | 38 |

Table 2.

The lengths of introns and exons for the splitting genes

| Gene | Strand | Start | End | ExonI | IntronI | ExonII | IntronII | ExonIII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| atpF | – | 11,074 | 12,350 | 145 | 722 | 410 | ||

| petB | + | 74,594 | 75,997 | 6 | 756 | 642 | ||

| petD | + | 76,196 | 77,382 | 8 | 704 | 475 | ||

| rps16 | – | 4913 | 6034 | 40 | 885 | 197 | ||

| rpoC1 | – | 20,203 | 23,031 | 432 | 786 | 1611 | ||

| ycf3 | – | 42,381 | 44,403 | 118 | 739 | 230 | 783 | 153 |

| clpP | – | 69,667 | 71,658 | 71 | 834 | 294 | 567 | 226 |

| rpl2 | – | 83,985 | 85,494 | 391 | 685 | 434 | ||

| ycf15 | + | 93,141 | 93,666 | 77 | 295 | 154 | ||

| ndhB | – | 94,345 | 96,563 | 775 | 686 | 758 | ||

| ndhB | + | 140,635 | 142,853 | 775 | 686 | 758 | ||

| ycf15 | – | 143,532 | 144,057 | 77 | 295 | 154 | ||

| rpl2 | + | 151,704 | 153,213 | 391 | 685 | 434 | ||

| ndhA | – | 118,768 | 120,965 | 553 | 1106 | 539 | ||

| trnS-CGA | + | 8236 | 9016 | 31 | 690 | 60 | ||

| trnE-UUC | + | 102,180 | 103,201 | 32 | 950 | 40 | ||

| trnA-UGC | + | 103,265 | 104,136 | 37 | 799 | 36 | ||

| trnA-UGC | – | 133,062 | 133,933 | 37 | 799 | 36 | ||

| trnE-UUC | – | 133,997 | 135,018 | 32 | 950 | 40 | ||

| trnL-UAA | + | 47,067 | 47,658 | 35 | 507 | 50 | ||

| trnV-UAC | – | 51,131 | 51,809 | 39 | 603 | 37 | ||

| trnK-UUU | – | 1582 | 4202 | 37 | 2549 | 35 |

Table 3.

Codon Usage in this chloroplast genome

| Codon | Amino acid | Frequency | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| GCA | A | 13.735 | 615 |

| GCC | A | 6.968 | 312 |

| GCG | A | 5.65 | 253 |

| GCT | A | 23.628 | 1058 |

| TGC | C | 3.64 | 163 |

| TGT | C | 8.553 | 383 |

| GAC | D | 8.553 | 383 |

| GAT | D | 30.172 | 1351 |

| GAA | E | 37.899 | 1697 |

| GAG | E | 11.993 | 537 |

| TTC | F | 19.966 | 894 |

| TTT | F | 41.227 | 1846 |

| GGA | G | 25.817 | 1156 |

| GGC | G | 6.164 | 276 |

| GGG | G | 11.725 | 525 |

| GGT | G | 22.445 | 1005 |

| CAC | H | 5.874 | 263 |

| CAT | H | 19.452 | 871 |

| ATA | I | 25.415 | 1138 |

| ATC | I | 16.37 | 733 |

| ATT | I | 43.683 | 1956 |

| AAA | K | 39.261 | 1758 |

| AAG | K | 14.74 | 660 |

| CTA | L | 12.819 | 574 |

| CTC | L | 7.348 | 329 |

| CTG | L | 7.727 | 346 |

| CTT | L | 22.489 | 1007 |

| TTA | L | 33.723 | 1510 |

| TTG | L | 22.11 | 990 |

| ATG | M | 22.132 | 991 |

| AAC | N | 11.166 | 500 |

| AAT | N | 37.207 | 1666 |

| CCA | P | 12.082 | 541 |

| CCC | P | 7.839 | 351 |

| CCG | P | 4.757 | 213 |

| CCT | P | 15.41 | 690 |

| CAA | Q | 28.184 | 1262 |

| CAG | Q | 7.281 | 326 |

| AGA | R | 17.107 | 766 |

| AGG | R | 7.258 | 325 |

| CGA | R | 13.668 | 612 |

| CGC | R | 3.864 | 173 |

| CGG | R | 4.288 | 192 |

| CGT | R | 12.73 | 570 |

| AGC | S | 5.516 | 247 |

| AGT | S | 16.035 | 718 |

| TCA | S | 16.191 | 725 |

| TCC | S | 12.149 | 544 |

| TCG | S | 6.812 | 305 |

| TCT | S | 22.512 | 1008 |

| ACA | T | 15.231 | 682 |

| ACC | T | 9.357 | 419 |

| ACG | T | 4.98 | 223 |

| ACT | T | 19.273 | 863 |

| GTA | V | 19.206 | 860 |

| GTC | V | 7.325 | 328 |

| GTG | V | 7.683 | 344 |

| GTT | V | 19.072 | 854 |

| TGG | W | 18.849 | 844 |

| TAC | Y | 7.035 | 315 |

| TAT | Y | 30.596 | 1370 |

| TAA | * | 3.395 | 152 |

| TAG | * | 2.211 | 99 |

| TGA | * | 2.457 | 110 |

Comparative analysis of S. persica cp genome with the cp genome of related species

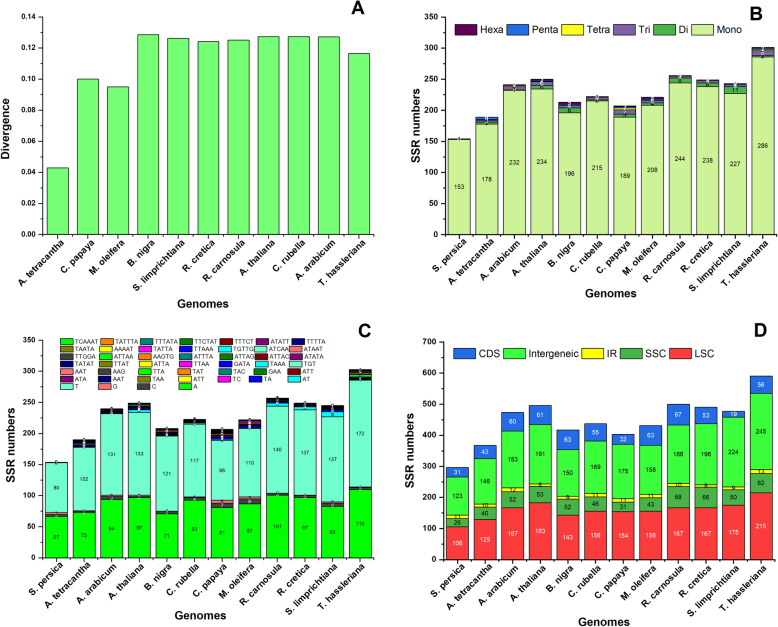

The S. persica cp genome was compared with other eleven cp genomes (A. tetracantha, A. arabicum, A. thaliana, B. nigra, C. rubella, C. papaya, M. oleifera, R. carnosula, R. cretica, C. limprichtiana and T. hassleriana) from six families Salvadoraceae, Apocynaceae, Brassicaceae, Caricacrea, Moringaceare, and Cleomaceae. The results revealed that the genome size of M. oleifera (160,600 bp) is the largest of these, followed by C. papaya (160,100 bp). In comparison, the smallest genome sizes were detected in S. persica (153,379 bp) and A. tetracantha (153,415 bp) from family Salvadoraceae. This difference in size was accredited to the LSC region’s size (Table 1). Analysis of genes with known function revealed that S. persica shared 71 genes with other 11 species cp genomes. The highest number of protein coding genes (PCGs) were detected in B. nigra (87) while lowest were observed in C. limprichtiana (71) (Table 1). Overall, the current results are showing a high rate of sequence resemblances among protein-coding and IR region (Figure S1). However, maximum amount of sequence divergences was observed in many intergenic regions, especially atpH – atpI, trnK-rps16, trnT-pscbD, rpoB-trnC, rps4-ndhJ, petA-psbL, rbcL-accD, ndhC-trnV and ycf4-cemA. Similarly, some divergences were also observed in protein-coding genes, including ycf1, rpl16, clpP, rpoC1, rpoC2, ndhA, atpF, ndhF and ycf15 (Figure S1). In pairwise sequence divergences, S. persica showed maximum divergences (0.28) with B. nigra and lowest with A. tetracantha (0.042) (Fig. 2a). Moreover, many SNP and InDel substitutions were revealed in the S. persica cp genome coding region and related species. The highest number of InDels were detected in T. hassleriana (352), while the lowest was observed in B. nigra (6). On the other hand, highest number of SNPs was detected in T. hassleriana (9935) and the lowest was detected in B. nigra (1009) (Table S2).

Fig. 2.

Evolutionary sequence divergence and simple sequence repeats (SSR) Analysis. Estimates of Evolutionary Divergence among S. persica and related cp genomes (a) Analysis of simple sequence repeats in the twelve chloroplast genomes including S. persica (b), frequency of identified SSR motifs in different repeat class types (c), SSR numbers detected in the twelve species LSC, SSC, IR, CDS and Intergenic regions (d)

Microsatellite markers arrangement in cp genome

In microsatellite analysis, a considerable variation was observed in order Brassicales. The lowest number of SSRs were detected in S. persica (154) and A. tetracantha (189) from the family Salvadoraceae. Similarly, T. hassleriana having highest microsatellite repeats, i.e., 301 followed by R. carnosula (256) and A. thaliana (250) (Fig. 2b). In S. persica cp genome about 153 SSRs were mononucleotide while one SSR is dinucleotide. Similarly, in A. tetracantha 178 mononucleotides, three di, three tri, and one tetra, four pentanucleotides were found. The hexanucleotide was absent in this genome. A. arabicum’ genome contained 232 mono, one di, five tri, two tetra and one pentanucleotide. A. thaliana has 234 mononucleotides, six di, six tri, one tetra, two Penta, and one hexanucleotide. B. nigra contain 196 mononucleotides, eight di, four tri, two penta and three hexanucleotide while tetranucleotide is absent. C. rubella has 215 mononucleotides, two di, four tri and one tetranucleotide, penta and hexanucleotide are missing here (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, mononucleotides are most abundant nucleotides among all six types of nucleotides in all cp genomes. In S. persica, almost 52.8% of the mononucleotide contain a T motif and 43.7 have A motif. A comparable pattern of SSR-motif was noted in related cp genomes (Fig. 2c). Among these SSRs 31 and 43 SSRs were found in coding-regions of S. persica and A. tetracantha, respectively. Similarly, in S. persica 106, 26, 11 and 123 SSRs were identified in LSC, SSC, IR and non-coding regions, respectively (Fig. 2d).

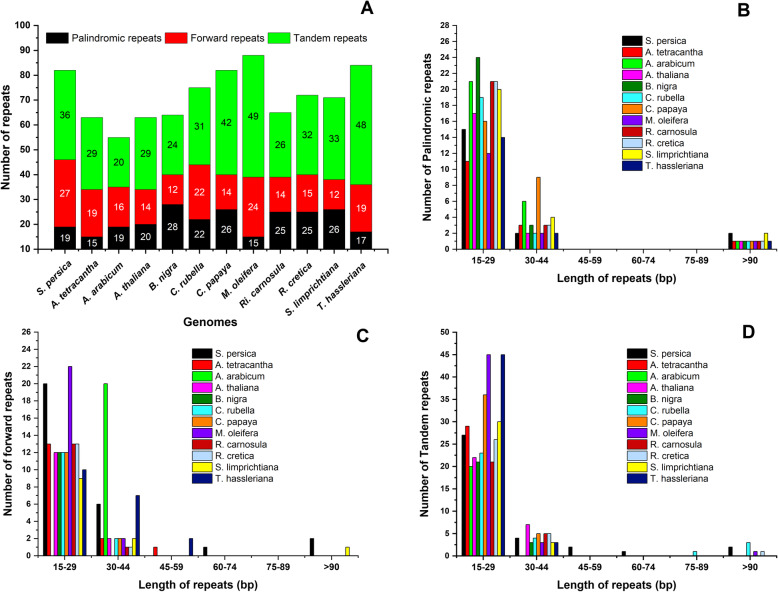

Repeat distribution in S. persica cp genome

In the current study, we studied different repeat sequences i.e., palindromic, forward and tandem repeats in S. persica chloroplast genome and compared it with 11 others cp genome genomes (Fig. 3). The results showed that S. persica contains 19 palindromic, 27 forward and 36 tandem repeats. A. tetracantha had 15 palindromic, 19 forward and 29 tandem repeats (Fig. 3). In S. persica repeats, 15 palindromic repeats were 15–29 bp, 2 were 30–44 bp in length while 2 were > 90 bp in length. In the case of forward repeats, 20 repeats were 15–29 bp, six repeats were 30–44 bp,1 was 60–74 bp in length, and 2 were > 90 bp in length. Similarly, 27 tandem repeats were15–29 bp in length, 4 were 30–44 bp in length, 2 were 45–59 bp in length, one repeat was 60–74 bp in length and 2 were > 90 bp in length. Furthermore, among these cp genomes, highest number of tandem repeats were detected in M. oleifera (49) followed by C. limprichtiana (48), while the lowest number was detected in A. arabicum (20). Similarly, the highest number of forward repeats were detected in S. persica (27), while lowest was seen in B. nigra and C. limprichtiana (12). However, the highest number of palindromic repeats were in B. nigra (28) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of repeated sequences in S. persica and other eleven cp genomes. a Totals numbers of three repeat types; b Number of palindromic repeats by length; c Number of forward repeats by length; d Number of tandem repeats by length

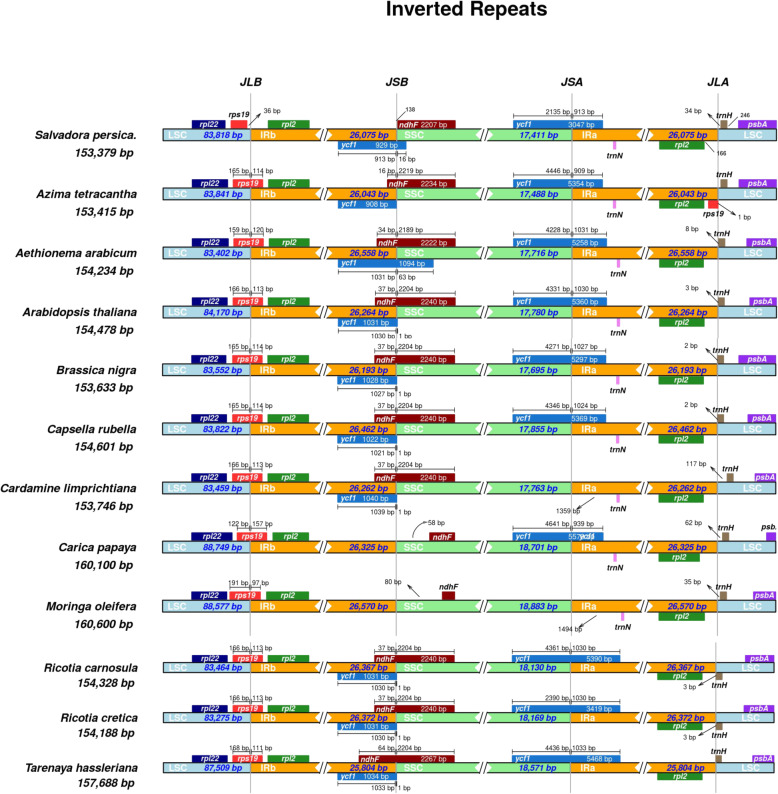

IR expansion and contraction in S. persica cp genome

In most angiosperms cp genomes IR regions are reported to be the most conserved regions. The larger IR length correlates with larger cp genome sizes. The IR length in S. persica is similar to previously reported angiosperm genomes. In the present study, comparative assessment of 4 junctions viz. JSA, JSB, JLA and JLB with IRa and IRb, two single copy regions, and S. persica with related 11 related species were performed (Fig. 4). Despite the similar lengths of S. persica and related genomes, some enlargement and shrinkage were noted within the IR region, ranging from 25,804 bp in T. hassleriana to 26,570 bp in M. oleifera. Results revealed that in S. persica the rps19 gene present 36 bp away from JLB junction toward the LSC region. The rpl2 gene occupied IRB region, the ycf1 gene overlapped the JSB junction and 913 bp present in IRB and 16 bp in SSC region. The ndhF gene occupied the SSC region about 138 bp away from JSB border and the trnN present in IRA region, while trnH present 34 bp away from JLA junction toward LSC region (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Distance between adjacent genes and junctions of the small single-copy (SSC), large single-copy (LSC), and two inverted repeats (IR) regions of S. persica with related species cp genomes. Boxes above and below the mainline indicate the adjacent border genes. The figure does not scale regarding sequence length and only shows relative changes at or near the IR/SC borders

Similarly, the psbA gene is resent in the LSC region. On the other hand, in A. tetracantha the rpl22 gene present in LSC region, the rps19 gene present across the JLB junction 165 bp toward LSC region and 114 bp toward IRB, ycf1 gene present in IRB region while ndhF present 16 bp in IRB region and 2234 in SSC region while the trnN gene present in IRA region. The rps19 gene in all other cp genomes showed almost similar result like A. tetracantha. In the case of ycf1 gene, the locations were also the same as A. tetracantha except A. arabicum in which the gene present across the JSB junction and in C. papaya present across JSA junction while in M. oleifera it is absent. The ndhF gene in C. papaya and M. oleifera 58 and 80 bp away from JSB junction toward the SSC side. The trnN gene occurs in the same position in all genomes but was absent in R. carnosula, R. cretica and T. hassleriana. The trnH occurs 117 bp away from JLA junction toward the LSC region.

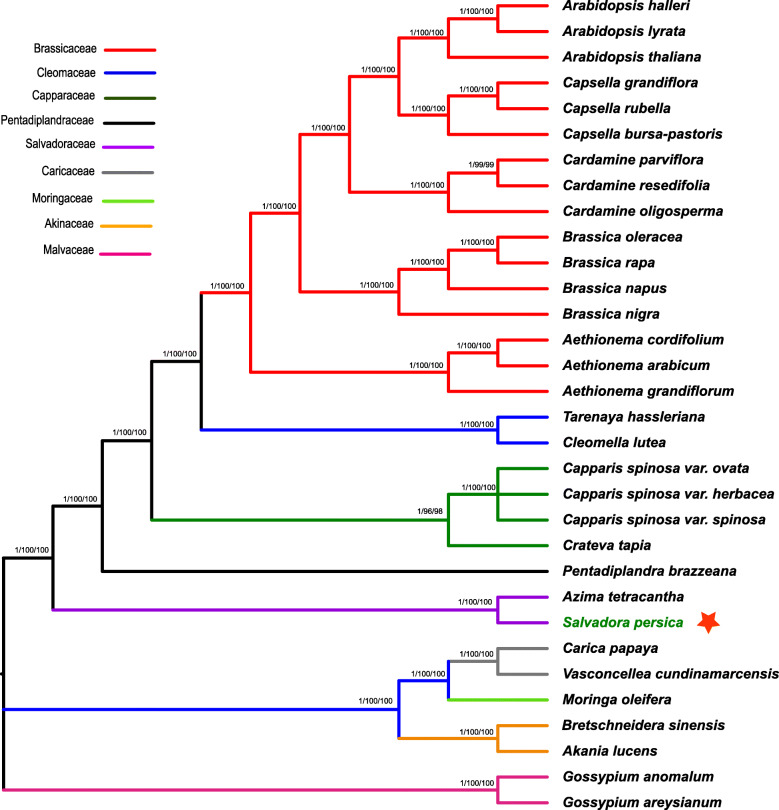

Phylogenomic assessment of S. persica

In the current study, the phylogenomic disposition of S. persica within the order Brassicales was revealed by analyzing multiple alignments of 60 shared genes from 9 families representing 32 genera (Fig. 5). The overall concatenated alignment size from the 60 protein – coding genes was 63,045 bp. Gossypium anomalum and G. areysianum species were set as the outgroup. Phylogenetic analysis using Maximum parsimony (MP), Bayesian inference (BI), and Maximum likelihood (ML) were performed. The results revealed that S. persica forms a single-clade with A. tetracantha showing highest bootstrap values. Similarly, this study also revealed that the family Salvadoraceae is closely related to Caricaceae, Petadiplandraceae, and Capparaceae.

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic trees of S. persica with related 31 species from class Brassicales. The 60 shared genes dataset was analyzed using Bayesian inference (BI), maximum parsimony (MP), and maximum likelihood (ML). Numbers above the branches represent bootstrap values in the MP and ML. The red star represents the position of S. persica

Discussion

The current study showed the first complete cp genome sequence for S. persica, genus Salvadora and family Salvadoraceae. Further, the cp genome was compared with eleven cp genomes of related species from order Brassicales. These cp genomes ranged from 153 kb to 160 kb in size and comprised all the four major components of chloroplast genome architecture. All the cp genomes are conserved and in the same range, and its genome sizes ranging from 153,379 bp in S. persica to 160, 600 bp in M. oleifera, which encoded 113–132 genes (131 in S. persica, 132 in B. nigra and 113 in C. limprichtiana) (Table 1). The size range of S. persica cp genome is found in the same range as the sizes of the previously reported cp genomes of A. tetracantha (153,415 bp) and other related species [29, 34–36]. Like typical angiosperms cp genomes (20 ± 28 kb), these species’ IRs length ranges from 25 to 26 kb in length [34, 37]. However, some variations were observed in these cp genomes, mainly due to variation in the LSC regions rather than contraction and expansion of IR region, as was found recently [27, 34, 38]. Like other reported cp genomes from Brassicales about 18 genes are duplicated in the IR regions, containing, four rRNA genes, seven tRNA genes, and eight protein-coding genes (PCGs) [39–41].

Furthermore, 22 (eight tRNA genes and 12 protein-coding genes) having introns were determined in these genomes and among these introns containing genes clpP, ycf3 and rps12 genes have two introns each (Table 2). In synergy with previously reported cp genomes, angiosperm rps12 was unequally divided. The maturase K (matK) gene is marked within the trnK intron as reported in other cp genomes from family Brassicales [42–44]. The S. persica LSC, SSC, and IR region’s GC content were 34.6, 30.2, and 42.2%. Like other angiosperm cp genomes, higher GC content was detected in IRs due to 8 rRNAs in these regions [23, 27, 45].

The complete S. persica cp genome was compared with the related 11 plant cp genomes. Chloroplast gene analysis with known function revealed that S. persica shared 74 protein-coding genes with related species. Furthermore, the gene contents and organization of S. persica were similar to those of other Brassicales cp genomes [34, 41, 43]. Similarly, the average pairwise sequence divergence among the S. persica and related species’ cp genomes was determined (Fig. 2a). The cp genome of S. persica exhibited an average sequence divergence of 0.112 with all species.

In contrast, the highest sequence divergence with B. nigra (0.128) whereas the lowest was observed with A. tetracantha (0.042). Despite the conserved gene order reported in most plants, some distinguished changes such as sequence inversion [32], gene loss [46] and contraction and expansion at the borders between IRs, SSC, and LSC regions [47, 48]. Similar length variation was observed previously among cp genomes due to the expansion and contraction of the IR regions [48, 49]. The S. persica cp genome was highly conservative in structure, size, IR and SC boundary locations. However, due to the contraction and expansion of IR regions some diversion was observed in most land plants [43, 50–53].

A detailed analysis of JSA, JSB, JLA and JLB between two IRs and LSCs of S. persica and with 11 related species (A. tetracantha, A. arabicum, A. thaliana, B. nigra, C. rubella, C. papaya, M. oleifera, R. carnosula, R. cretica, C. limprichtiana, and T. hassleriana) were performed. Despite similar lengths of the IR regions of S. persica and related species, some contraction and extension were determined, with the IR regions ranging from 25,804 bp in T. hassleriana to 26,570 bp in M. oleifera. Despite the four conserved junctions in these cp genomes, some variations were observed with C. papaya and M. oleifera cp genomes. The rps19 gene is present 36 bp away in the LSC region in S. persica. Simultaneously, in other genomes it is partially duplicated genes detected in the IRs, including 114 bp of rps19 in A. tetracantha (Fig. 4). Previous reports suggested that repeats, playing a pivotal role in cp genome rearrangements, are essential in performing phylogenetic assessments [54, 55]. Also, comparative evaluation of cp genomes has shown that repeat sequences induce indels and substitutions [56], and re-arrangements of cp sequences and their variatihat occur due to improper recombination and slipped strand mispairing of such repeat sequences [54, 57, 58]. The detection of repeat sequences shows that loci are hotspots for genome re-configuration [55, 59], and repeats can be used to proposed molecular markers for population and phylogenetic studies [55].

As reported by various researchers, repeat sequences which can be very useful in phylogenetic studies can contribute significantly to genome rearrangement [60]. Total 82 repeats were noted in the S. persica cp genome. Similarly, about 63 repeats were detected in the A. tetracantha cp genome. In comparative analysis, higher repeats (88) were found in M. oleifera while the lowest was seen in A. arabcum (55) cp genome respectively (Fig. 3). In our study, tandem repeats were detected to be the most plentiful in the M. oleifera (49) cp genome, showing similar traits to the previously reported cp genome [61, 62]. SSRs are helpful molecular markers to determine a high degree of variation with similar species and have been used to explore population genetics and polymorphisms [63]. SSRs distinguish potentially valuable markers because of maternal inheritance, relative lack of recombination, and their haploid nature for phylogenetic studies [64]. SSRs have been primarily used to analyze gene flow, genetic variation estimation, and analyze the populations’ history animals and plants [65, 66]. We have detected 154 microsatellites in the S. persica cp genome and about 123 were observed in non-coding regions. It has been in synergy with angiosperm cp genomes where a higher number of SSRs were revealed primarily on non-coding regions. Approximately, 154, 189, 243. 252, 213, 224, 207, 221, 255, 249, 243 and 301 SSRs were detected in A. tetracantha, A. arabicum, A. thaliana, B. nigra, C. rubella, C. papaya, M. oleifera, R. carnosula, R. cretica, C. limprichtiana, and T. hassleriana cp genomes, respectively (Fig. 2). Mono SSRs mainly were detected in S. persica cp genome. A similar pattern was also reported previously in angiosperms cp genomes [42, 66–68]. Current results are in accordant to recent studies exhibit that the SSRs detected in the cp genome are usually composed of polyadenine or polythymine repeats and rarely comprise tandem guanine (G) and cytosine (C) repeats [56]. Therefore, SSRs extend a greater contribution to the ‘AT’ diversity of S. persica cp genomes, as previously reported for different species [37, 69]. These analyses also revealed that approximately 80% of SSRs were determined in non-coding regions. Similar results were reported earlier, showing SSRs are unequally distributed and might give more information to select molecular markers for both intra and inter-specific polymorphisms [70, 71]. Our findings are parallel with other reports from family Brassicaceae that SSRs having ‘A’ or ‘T’ mononucleotide repeats dominated the cp genomes. Furthermore, mono-nucleotide, penta-nucleotide and hexa-nucleotide repeats contained ‘A’ or ‘T’ at higher amount, which revealed a biased base composition, with an overall ‘AT’ richness in the cp genomes [27, 72].

Chloroplast genomes are valuable sources for molecular, evolutionary and phylogenetic studies. In the recent decade, numerous analyses on the comparison of plastid protein-coding genes [73–75] and complete genome sequences [34, 76] have been done to answer the phylogenetic disposition at deep-nodes and improve the mysterious evolutionary relatedness among angiosperms. In this study, the phylogenetic position of S. persica within the order Brassicales was established by analyzing multiple alignments of 60 shared genes from 9 families representing 26 genera (Fig. 5). The results revealed that S. persica forms a single clade with A. tetracantha with high bootstrap and BI through different methods. Similarly, this study also revealed that family Salvadoraceae is affiliated with Caricaceae, Petadiplandraceae and Capparaceae [77]. reported that Salvadoraceae is affiliated in Brassicales based on trnL-F as currently considered by most angiosperms systematic.

Similarly, the previous phylogeny based on 18S locus showed association of Salvadoraceae in Brassicales [17, 78]. However, previously based on comparative analysis of floral and seed anatomy and molecular systematic Salvadoraceae, sister to Bataceae and Koberliniacaea near Brassicales. These conflicting findings need to be further analyzed based on complete cp genomes and shared concatenated genes from all representative species. This study is the first cp genome based phylogenetic assessment of genus family Salvadoracee. Therefore, it is necessary to use more species from the family Salvadoraceae and other Brassicales families to understand phylogeny and evolution better.

Conclusion

In this study, we elucidated the complete chloroplast genome of S. persica for the first time. The gene order and cp genome rearrangement of S. persica were similar to that of cp genomes of other related species in the order Brassicales. SSRs and repetitive sequences were analyzed in these cp genomes and highest number of SSRs and repeats were detected in T. hassleriana and M. oleifera respectively. Overall, a high degree of sequence similarity between S. persica and related cp genomes was detected. However, some divergence is detected in intergenic regions and some protein coding genes. The results revealed that S. persica form a single clade with A. tetracantha and the family Salvadoraceae is related to Petadiplandraceae and Capparaceae base on 60 cp shared genes. The current study provides a valuable set of information, which could help species identification and facilitate species identification and solve taxonomic questions.

Methodology

S. persica DNA extraction, sequencing and assembly

S. persica young leaves were collected from Jabal Al-Akhdar, Oman (23° 6′ 12.0780″ N; 57° 22′ 47.7984″ E). The voucher specimen (UoN-H101) was deposited in the Herbarium Center, University of Nizwa, Oman after identifying it from Taxonomist (Saif Al-Hathmi) at Oman Botanic Garden, Muscat Oman. Permission (6210/10/73) to collect plants for research purpose was obtained from Ministry of Environment & Climate Affairs, Muscat Oman. The leaf samples were ground into a fine powder with the help of liquid nitrogen. Cp DNA was extracted according to the protocol of [22, 23]. Cp DNA was further cleaned up using DNAeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) by following manufacture protocol. Similarly, genomic libraries were prepared for Ion S5 sequencing (Life Technologies USA, Eugene, OR, USA) by following manufacturer’s instructions. Cp DNA was fragmented into 400 bp enzymatically using Ion-Shear™ Plus Reagents kit and preparing libraries Ion-Xpress™ Plus gDNA Fragment Library kit. These libraries were quantified using Qubit 3.0 and bioanalyzer (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system, Life Technologies USA). The excellent quality library was amplified using the Ion OneTouch™ 2 instrument, and then the Ion OneTouch™ ES enrichment system was used to enrich these amplified libraries. Then the sample was loaded on Ion S5 530 Chip for sequencing by following Ion S5 sequencing protocol.

S. persica chloroplast assembly and genome annotation

A total of 5,526,428 raw reads were produced for S. persica. The generated cp genome reads were de novo assembled and then mapped to A. tetracantha, which was used as reference genome with the help of Bowtie2 assembler (v.2.2.3) [79] in Geneious prime (v.10.2.3) software [80]. CpGAVAS2 [81] was used for S. persica cp genome cp genome annotation. To check the annotation results manually BLAST (v.2.8.1) and DOGMA was used [82]. A genomic map was generated by software Chloroplast [83] and inverted repeat sequences were identified through REPuter [84]. For tRNA detection tRNAscan-SE version 1.21 [85] was used. Moreover, for manual adjustment, tRNAscan-SE and Geneious Prime were used to compare and manually adjusted the start, stop codons and intron boundaries with already reported cp genome. Furthermore, mVISTA version 2.1 [86] in Shuffle-LAGAN mode was used for S. persica cp genome divergence with related eleven species where S. persica was selected as reference genome. The cp genome was submitted to NCBI gene bank and publicly available with accession number MW233589.

Repeat analysis in S. persica cp genome

For reverse and forward repeats identification online software REPuter software [84], was used. About 90% of identities and 15 bp sequences were considered a minimum criterion. Similarly, to detect SSRs MISA software [87] was used with the following search criteria: for mononucleotide repeats ≥10 repeat units; for dinucleotide repeats ≥8 repeat units, for tri and tetra nucleotide repeats ≥4 repeat units; and for penta and hexa nucleotide repeats ≥3 repeat units. Furthermore, tandem repeat Finder version 4.07 [88], with default settings, was used to calculate tandem repeats in these cp genomes.

S. persica phylogenetic analysis and cp genome divergence

Chloroplast genome divergence among S. persica and 11 species from order Brassicales were calculated. A comparative analysis method was used to compare gene order and detect the unclear and absent gene annotation after multiple sequence alignments. MAFFT version 7.222 [89], was used to align the complete cp genome and Kimura’s two-parameter (K2P) model [90] was applied to calculate pairwise-sequence divergence. Similarly, to determine the phylogenetic positions of S. persica within the class Brassicales was established by downloading 31 cp genome sequences representing 9 genera from the NCBI database. Based on 60 shared genes among these 32 genomes three different approaches were applied to infer phylogenetic tree: maximum parsimony (MP), using PAUP 4.0 [91]; Bayesian inference (BI), implemented in Mr. Bayes 3.1.2 [92] and maximum likelihood (ML) using MEGA 6 [93], using previously described settings [22, 94]. The best substitution model GTR + G was tested by jModel Test version v2.1.02100 according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC) for Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) in BI analyses. The Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method was run using four incrementally heated chains across 1,000,000 generations, starting from random trees and sampling 1 out of every 100 generations. ML analysis parameters were optimized using a BIONJ tree101 as the starting tree with 1000 bootstrap replicates by employing the Kimura 2-parameter model with invariant sites and gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity. Similarly, to estimate the posterior probabilities, the values of first 30% of trees were discarded as burn-in. Maximum parsimony run was based on a heuristic search with 1000 random addition of sequence replicates with the tree-bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch-swapping tree search criterion.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Visual alignment of chloroplast genomes from S. persica with related 11 chloroplast genomes from order Brassicales. VISTA-based identity plot showing sequence identity among 11 species, using S. persica as a reference. The vertical scale indicates percent identity, ranging from 50 to 100%. The horizontal axis indicates the coordinates within the chloroplast genome. Arrows indicate the annotated genes and their transcription direction. The thick black lines show the inverted repeats (IRs).

Additional file 2: Table S1. Gene composition in this chloroplast genome.

Additional file 3: Table S2. SNP and Indel analysis of S. persica cp genome with related 11 species.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to OAPGRC (Oman’s Animal and Plant Genetic Resource Center) for their support and Mr. Arif Khan’s initial experimental work.

Authors’ contributions

Abdul Latif Khan and Sajjad Asaf performed experiments; Abdul Latif Khan, Sajjad Asaf and Lubna wrote the original draft and Bioinformatics analysis: Ahmed Al-Harrasi, Ahmed Al-Rawahi supervision and arranging resources. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the NCBI GenBank ((https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; Accession number MW233589).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The collection of plants in the present study was compiled according to the National guidelines of the Ministry of Environment & Climate Affairs, Muscat, Oman.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sajjad Asaf, Email: sajjadasaf@unizwa.edu.om.

Ahmed Al-Harrasi, Email: aharrasi@unizwa.edu.om.

References

- 1.Kubitzki K. Salvadoraceae. Flowering Plants· Dicotyledons. Berlin: Springer; 2003. p. 342–4.

- 2.Panday B. A textbook of botany angiosperm. New Delhi: Chand and company Ltd; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson L. The families of flowering plants: descriptions, illustrations, identification and information retrieval. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sher H, Al-Yemeni M, Masrahi YS, Shah AH. Ethnomedicinal and ethnoecological evaluation of Salvadora persica L.: a threatened medicinal plant in Arabian peninsula. J Med Plants Res. 2010;4:1209–1215. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyenger E, Patolia J, Chikara J. A useful plant for coastal saline soils. Wastelands News. 1992;32:50–51. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maggio A, Reddy MP, Joly RJ. Leaf gas exchange and solute accumulation in the halophyte Salvadora persica grown at moderate salinity. Environ Exp Bot. 2000;44(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/S0098-8472(00)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marwat SK, et al. Fruit plant species mentioned in the holy Qura'n and Ahadith and their ethnomedicinal importance. Am-Eurasian J Agric Environ Sci. 2009;5:284–295. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halawany HS. A review on miswak (Salvadora persica) and its effect on various aspects of oral health. Saudi Dental J. 2012;24(2):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg A. Classification, evolution, and phylogeny of the families of dicotyledons. Smithson Contrib Bot. 1986;(58):1–314. 10.5479/si.0081024X.58.

- 10.Cronquist A, Takhtadzhian AL. An integrated system of classification of flowering plants. New York: Columbia University Press; 1981.

- 11.Takhtadzhian AL, Takhtajan LA, Takhtajan A. Diversity and classification of flowering plants. New York: Columbia University Press; 1997.

- 12.Thorne RF. Classification and geography of the flowering plants. Bot Rev. 1992;58(3):225–327. doi: 10.1007/BF02858611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahlgren R. A system of classification of the angiosperms to demonstrate the distribution of characters. 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahlgren G. The last Dahlgrenogram. System of classification of the dicotyledons: the Davis and Hedge Festschrift: plant taxonomy, phytogeography and related subjects. Edinburg: Edinburgh University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodman J, et al. Nucleotide sequences of the rbcL gene indicate monophyly of mustard oil plants. Ann Missouri Botanical Garden. 1993;(1):686–99.

- 16.Rodman JE, Karol KG, Price RA, Sytsma KJ. Molecules, morphology, and Dahlgren's expanded order Capparales. Systematic Botany. 1996;(1):289–307.

- 17.Rodman JE, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Sytsma KJ, Karol KG. Parallel evolution of glucosinolate biosynthesis inferred from congruent nuclear and plastid gene phylogenies. Am J Bot. 1998;85(7):997–1006. doi: 10.2307/2446366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramakrishnan M, Ceasar SA, Duraipandiyan V, Al-Dhabi N, Ignacimuthu S. Using molecular markers to assess the genetic diversity and population structure of finger millet (Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn.) from various geographical regions. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2016;63(2):361–376. doi: 10.1007/s10722-015-0255-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal M, Shrivastava N, Padh H. Advances in molecular marker techniques and their applications in plant sciences. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27(4):617–631. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0507-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta PK, Varshney R. The development and use of microsatellite markers for genetic analysis and plant breeding with emphasis on bread wheat. Euphytica. 2000;113(3):163–185. doi: 10.1023/A:1003910819967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ronse De Craene LP, Haston E. The systematic relationships of glucosinolate-producing plants and related families: a cladistic investigation based on morphological and molecular characters. Botanical J Linnean Soc. 2006;151:453–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2006.00580.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asaf S, et al. Complete chloroplast genome of Nicotiana otophora and its comparison with related species. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:843. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan A, et al. First complete chloroplast genomics and comparative phylogenetic analysis of Commiphora gileadensis and C. foliacea: myrrh producing trees. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0208511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuhaus H, Emes M. Nonphotosynthetic metabolism in plastids. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2000;51(1):111–140. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer JD. Comparative organization of chloroplast genomes. Annu Rev Genet. 1985;19(1):325–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.19.120185.001545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma J, Yang B, Zhu W, Sun L, Tian J, Wang X. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Mahonia bealei (Berberidaceae) reveals a significant expansion of the inverted repeat and phylogenetic relationship with other angiosperms. Gene. 2013;528(2):120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asaf S, Jan R, Khan AL, Lee I-J. Complete chloroplast genome characterization of oxalis Corniculata and its comparison with related species from family Oxalidaceae. Plants. 2020;9:928. doi: 10.3390/plants9080928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bendich AJ. Circular chloroplast chromosomes: the grand illusion. Plant Cell. 2004;16(7):1661–1666. doi: 10.1105/tpc.160771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asaf S, et al. Chloroplast genomes of Arabidopsis halleri ssp. gemmifera and Arabidopsis lyrata ssp. petraea: Structures and comparative analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7556. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07891-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang T, Fang Y, Wang X, Deng X, Zhang X, Hu S, Yu J. The complete chloroplast and mitochondrial genome sequences of Boea hygrometrica: insights into the evolution of plant organellar genomes. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caron H, Dumas S, Marque G, Messier C, Bandou E, Petit RJ, Kremer A. Spatial and temporal distribution of chloroplast DNA polymorphism in a tropical tree species. Mol Ecol. 2000;9(8):1089–1098. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho K-S, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) and comparative analysis with common buckwheat (F. esculentum) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh BP, Kumar A, Kaur H, Singh H, Nagpal AK. CpGDB: a comprehensive database of chloroplast genomes. Bioinformation. 2020;16(2):171–175. doi: 10.6026/97320630016171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asaf S, Khan AL, Aaqil Khan M, Muhammad Imran Q, Kang SM, al-Hosni K, Jeong EJ, Lee KE, Lee IJ. Comparative analysis of complete plastid genomes from wild soybean (Glycine soja) and nine other Glycine species. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin Z, et al. Comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes in Vasconcellea pubescens A, DC and Carica papaya L. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56847-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Z, Ma Q. Limited variation across two chloroplast genomes with finishing chloroplast genome of Capsella grandiflora. Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 2016;27(5):3460–3461. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1066347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qian J, Song J, Gao H, Zhu Y, Xu J, Pang X, Yao H, Sun C, Li X’, Li C, Liu J, Xu H, Chen S. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asaf S, Khan AL, Khan A, Al-Harrasi A. Unraveling the chloroplast genomes of two Prosopis species to identify its genomic information, comparative analyses and phylogenetic relationship. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3280. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee S-B, Kaittanis C, Jansen RK, Hostetler JB, Tallon LJ, Town CD, Daniell H. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Gossypium hirsutum: organization and phylogenetic relationships to other angiosperms. BMC Genomics. 2006;7(1):61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu W, Kong H, Zhou J, Fritsch P, Hao G, Gong W. Complete chloroplast genome of Cercis chuniana (Fabaceae) with structural and genetic comparison to six species in Caesalpinioideae. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(5):1286. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seol Y-J, Kim K, Kang SH, Perumal S, Lee J, Kim CK. The complete chloroplast genome of two Brassica species, Brassica nigra and B Oleracea. Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 2017;28(2):167–168. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1115493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gandhi SG, Awasthi P, Bedi YS. Analysis of SSR dynamics in chloroplast genomes of Brassicaceae family. Bioinformation. 2010;5(1):16–20. doi: 10.6026/97320630005016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raman G, Park V, Kwak M, Lee B, Park S. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Arabis stellari and comparisons with related species. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Du X, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of yellow mustard (Sinapis alba L.) and its phylogenetic relationship to other Brassicaceae species. Gene. 2020;731(144340):144340. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Notsu Y, Masood S, Nishikawa T, Kubo N, Akiduki G, Nakazono M, Hirai A, Kadowaki K. The complete sequence of the rice (Oryza sativa L.) mitochondrial genome: frequent DNA sequence acquisition and loss during the evolution of flowering plants. Mol Gen Genomics. 2002;268(4):434–445. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0767-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu P-C, Zhang Y-Z, Geng H-M, Chen S-L. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Gentiana lawrencei var. farreri (Gentianaceae) and comparative analysis with its congeneric species. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2540. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khan A, Asaf S, Khan AL, Khan A, al-Harrasi A, al-Sudairy O, AbdulKareem NM, al-Saady N, al-Rawahi A. Complete chloroplast genomes of medicinally important Teucrium species and comparative analyses with related species from Lamiaceae. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7260. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho K-S, Park T-H. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Solanum nigrum and development of markers for the discrimination of S. nigrum. Horticulture Environ Biotechnol. 2016;57:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s13580-016-0003-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asaf S, et al. Expanded inverted repeat region with large scale inversion in the first complete plastid genome sequence of Plantago ovata. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–16. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60803-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hansen DR, Dastidar SG, Cai Z, Penaflor C, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Phylogenetic and evolutionary implications of complete chloroplast genome sequences of four early-diverging angiosperms: Buxus (Buxaceae), Chloranthus (Chloranthaceae), Dioscorea (Dioscoreaceae), and Illicium (Schisandraceae) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;45(2):547–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu H, et al. Species delimitation and interspecific relationships of the genus Orychophragmus (Brassicaceae) inferred from whole chloroplast genomes. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1826. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang H, Shi C, Liu Y, Mao S-Y, Gao L-Z. Thirteen Camelliachloroplast genome sequences determined by high-throughput sequencing: genome structure and phylogenetic relationships. BMC Evol Biol. 2014;14(1):151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park J, Xi H, Kim Y. The complete chloroplast genome of Arabidopsis thaliana isolated in Korea (Brassicaceae): an investigation of intraspecific variations of the chloroplast genome of Korean A thaliana. Int J Genomics. 2020;2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Cavalier-Smith T. Chloroplast evolution: secondary symbiogenesis and multiple losses. Curr Biol. 2002;12(2):R62–R64. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nie X, Lv S, Zhang Y, du X, Wang L, Biradar SS, Tan X, Wan F, Weining S. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a major invasive species, Crofton weed (Ageratina adenophora) PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yi X, Gao L, Wang B, Su Y-J, Wang T. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Cephalotaxus oliveri (Cephalotaxaceae): evolutionary comparison of Cephalotaxus chloroplast DNAs and insights into the loss of inverted repeat copies in gymnosperms. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5(4):688–698. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Asaf S, et al. The complete chloroplast genome of wild rice (Oryza minuta) and its comparison to related species. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:304. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Asano T, Tsudzuki T, Takahashi S, Shimada H, Kadowaki K-I. Complete nucleotide sequence of the sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) chloroplast genome: a comparative analysis of four monocot chloroplast genomes. DNA Res. 2004;11(2):93–99. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gao L, Yi X, Yang Y-X, Su Y-J, Wang T. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a tree fern Alsophila spinulosa: insights into evolutionary changes in fern chloroplast genomes. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9(1):130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.do Nascimento Vieira L, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Podocarpus lambertii: genome structure, evolutionary aspects, gene content and SSR detection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin W, Dai S, Chen Y, Zhou Y, Liu X. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Moringa oleifera lam.(Moringaceae) Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2019;4(2):4094–4095. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1627922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang Y, Tian Y, He S-L. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Moringa oleifera lam.(Moringaceae), an important edible species in India. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2019;4(1):1913–1915. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1611393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao Y, et al. The complete chloroplast genome provides insight into the evolution and polymorphism of Panax ginseng. Front Plant Sci. 2015;5:696. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ebert D, Peakall R. Chloroplast simple sequence repeats (cpSSRs): technical resources and recommendations for expanding cpSSR discovery and applications to a wide array of plant species. Mol Ecol Resour. 2009;9(3):673–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Addisalem AB, Esselink GD, Bongers F, Smulders MJ. Genomic sequencing and microsatellite marker development for Boswellia papyrifera, an economically important but threatened tree native to dry tropical forests. AoB Plants. 2015;1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Flannery M, et al. Plastid genome characterisation in Brassica and Brassicaceae using a new set of nine SSRs. Theor Appl Genet. 2006;113(7):1221–1231. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bessega CF, et al. New microsatellite loci for Prosopis alba and P. chilensis (Fabaceae) Applications Plant Sci. 2013;1:1200324. doi: 10.3732/apps.1200324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kuang D-Y, Wu H, Wang YL, Gao LM, Zhang SZ, Lu L. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Magnolia kwangsiensis (Magnoliaceae): implication for DNA barcoding and population genetics. Genome. 2011;54(8):663–673. doi: 10.1139/g11-026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shen X, Wu M, Liao B, Liu Z, Bai R, Xiao S, Li X, Zhang B, Xu J, Chen S. Complete chloroplast genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the medicinal plant Artemisia annua. Molecules. 2017;22(8):1330. doi: 10.3390/molecules22081330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Powell W, Morgante M, McDevitt R, Vendramin G, Rafalski J. Polymorphic simple sequence repeat regions in chloroplast genomes: applications to the population genetics of pines. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92(17):7759–7763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Provan J, Corbett G, Powell W, McNicol J. Chloroplast DNA variability in wild and cultivated rice (Oryza spp.) revealed by polymorphic chloroplast simple sequence repeats. Genome. 1997;40(1):104–110. doi: 10.1139/g97-014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li X, Gao HH, Wang YT, Song JY, Henry R, Wu HZ, Hu ZG, Yao H, Luo HM, Luo K, Pan HL, Chen SL. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Magnolia grandiflora and comparative analysis with related species. Sci China Life Sci. 2013;56(2):189–198. doi: 10.1007/s11427-012-4430-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goremykin VV, Hirsch-Ernst KI, Wölfl S, Hellwig FH. The chloroplast genome of Nymphaea alba: whole-genome analyses and the problem of identifying the most basal angiosperm. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21(7):1445–1454. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moore MJ, Soltis PS, Bell CD, Burleigh JG, Soltis DE. Phylogenetic analysis of 83 plastid genes further resolves the early diversification of eudicots. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(10):4623–4628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907801107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu C-S, Wang Y-N, Liu S-M, Chaw S-M. Chloroplast genome (cpDNA) of Cycas taitungensis and 56 cp protein-coding genes of Gnetum parvifolium: insights into cpDNA evolution and phylogeny of extant seed plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(6):1366–1379. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dobeš C, Paule J. A comprehensive chloroplast DNA-based phylogeny of the genus Potentilla (Rosaceae): implications for its geographic origin, phylogeography and generic circumscription. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2010;56(1):156–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bast F, Kaur N. Nuclear and Plastid DNA Sequence-based Molecular Phylogeography of Salvadora oleoides (Salvadoraceae) in Punjab, India Reveals Allopatric Speciation in Anthropogenic Islands Due to Agricultural Expansion. J Phylogenetics Evol Biol. 5:180. 10.4172/2329-9002.1000180 Page 2 of 7 J Phylogenetics Evol Biol, an open access journal Trends of Evolutionary Biology & Molecular Phylogenetics ISSN: 2329–9002. (CUP VOUCHER-SO-2014-11 Ferozpur Sukhwant Singh and Navreet Kaur 04-04-2014 …, 2017).

- 78.Khan AL, Asaf S, Lee I-J, Al-Harrasi A, Al-Rawahi A. First reported chloroplast genome sequence of Punica granatum (cultivar Helow) from Jabal Al-Akhdar, Oman: phylogenetic comparative assortment with Lagerstroemia. Genetica. 2018;146(6):461–474. doi: 10.1007/s10709-018-0037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shi L, Chen H, Jiang M, Wang L, Wu X, Huang L, Liu C. CPGAVAS2, an integrated plastome sequence annotator and analyzer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W65–W73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(17):3252–3255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zheng S, Poczai P, Hyvönen J, Tang J, Amiryousefi A. Chloroplot: An Online Program for the Versatile Plotting of Organelle Genomes. Front Genet. 2020;11:576124.pmid:33101394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(22):4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(5):955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brudno M, Poliakov A, Minovitsky S, Ratnere I, Dubchak I. Multiple whole genome alignments and novel biomedical applications at the VISTA portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server):W669–W674. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beier S, Thiel T, Münch T, Scholz U, Mascher M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(16):2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wirawan A, Kwoh CK, Hsu LY, Koh TH. INVERTER: integrated variable number tandem repeat finder. In: International Conference on Computational Systems-Biology and Bioinformatics. Berlin: Springer; 2010. p. 151–64.

- 89.Katoh K, Kuma K-I, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(2):511–518. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16(2):111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Swofford DL. PAUP*4.0b10: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony. Sunderland: Sinauer; 2003.

- 92.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(12):1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kumar S, Nei M, Dudley J, Tamura K. MEGA: a biologist-centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief Bioinform. 2008;9(4):299–306. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, Depamphilis CW, Müller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;76(3-5):273–297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Visual alignment of chloroplast genomes from S. persica with related 11 chloroplast genomes from order Brassicales. VISTA-based identity plot showing sequence identity among 11 species, using S. persica as a reference. The vertical scale indicates percent identity, ranging from 50 to 100%. The horizontal axis indicates the coordinates within the chloroplast genome. Arrows indicate the annotated genes and their transcription direction. The thick black lines show the inverted repeats (IRs).

Additional file 2: Table S1. Gene composition in this chloroplast genome.

Additional file 3: Table S2. SNP and Indel analysis of S. persica cp genome with related 11 species.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the NCBI GenBank ((https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; Accession number MW233589).