Abstract

Background

Cultivated tea is one of the most important economic and ecological trees distributed worldwide. Cultivated tea suffer from long-term targeted selection of traits and overexploitation of habitats by human beings, which may have changed its genetic structure. The chloroplast is an organelle with a conserved cyclic genomic structure, and it can help us better understand the evolutionary relationship of Camellia plants.

Results

We conducted comparative and evolutionary analyses on cultivated tea and wild tea, and we detected the evolutionary characteristics of cultivated tea. The chloroplast genome sizes of cultivated tea were slightly different, ranging from 157,025 to 157,100 bp. In addition, the cultivated species were more conserved than the wild species, in terms of the genome length, gene number, gene arrangement and GC content. However, comparing Camellia sinensis var. sinensis and Camellia sinensis var. assamica with their cultivars, the IR length variation was approximately 20 bp and 30 bp, respectively. The nucleotide diversity of 14 sequences in cultivated tea was higher than that in wild tea. Detailed analysis on the genomic variation and evolution of Camellia sinensis var. sinensis cultivars revealed 67 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), 46 insertions/deletions (indels), and 16 protein coding genes with nucleotide substitutions, while Camellia sinensis var. assamica cultivars revealed 4 indels. In cultivated tea, the most variable gene was ycf1. The largest number of nucleotide substitutions, five amino acids exhibited site-specific selection, and a 9 bp sequence insertion were found in the Camellia sinensis var. sinensis cultivars. In addition, phylogenetic relationship in the ycf1 tree suggested that the ycf1 gene has diverged in cultivated tea. Because C. sinensis var. sinensis and its cultivated species were not tightly clustered.

Conclusions

The cultivated species were more conserved than the wild species in terms of architecture and linear sequence order. The variation of the chloroplast genome in cultivated tea was mainly manifested in the nucleotide polymorphisms and sequence insertions. These results provided evidence regarding the influence of human activities on tea.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12862-021-01800-1.

Keywords: Chloroplast genome, Cultivated tea, Evolution, ycf1, Camellia

Background

From ancient times, numerous plant species have been taken from their habitats and introduced into cultivation—that is, into various human-made systems [1]. The cultivation process has played an important role in human history and cultivated environments often present strong ecological contrasts with wild environments [2]. Wild species are exposed to natural selection that operates to promote survival under abiotic and biotic stresses, while cultivated species are subjected to artificial selection that emphasizes a steady supply, improved quality and increased yield. The criteria for fitness are expected to change dramatically under both regimes. Therefore, alterations in vegetation phenology, growth and reproductive traits occur because the plants are subjected to different levels of stress and distinctive selection pressures [3]. Pot experiments showed there were significant differences in the flowering and pod set between wild and cultivated types of soybean [4]. In addition, the compounds and microstructures have been surveyed for many horticultural plants [5]. The inadequate genetic information prevents us from fully understanding the spreading process of cultivated plants. We need to compare the genetic differences between cultivated species and wild species in order to use these species more effectively.

Camellia, containing approximately 280 species, is a genus with high economic, ecological and phylogenetic values in the family Theaceae [6, 7]. Camellia are native to Asia and have been cultivated for more than 1300 years [8]. Because their variety of uses, the cultivated species are now found all over the world [9, 10]. Camellia species can provide many valuable products, including making tea with the young leaves and extracting edible oil from the seeds. Moreover, most Camellia species are also of great ornamental value [11]. The genus Camellia is composed of more than 110 taxa [12], of which Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze is the most important source of the beverage tea. Cultivated tea plant varieties mainly belong to two major groups: Camellia sinensis var. sinensis (CSS; Chinese type) and Camellia sinensis var. assamica (CSA; Assam type) [13]. Due to long-term cultivation and manual selection, C. sinensis formed many local varieties, such as Camellia sinensis var. sinensis cv. Anhua (CSSA), Camellia sinensis var. sinensis cv. Longjing43 (CSSL), Camellia sinensis var. assamica cv. Yunkang10 (CSAY) and so on. Wild tea plants are important genetic diversity resources that can provide new traits for improved yield, disease resistance and tolerance to different environmental conditions. For example, the leaves of CSSA, well known for its specific area, are the main sources of dark tea [14]. The quality of dark tea products is related to the abundant cultivars, germplasm resources and geographical conditions [15].

The chloroplast (cp) genome is often used to analyze the evolutionary process and the phylogenetic status because of its high degree of conservation and relatively compact gene alignment. Moreover, cp genome sequences are useful in the identification of closely related, breeding-compatible plant species [16]. Although the cp genome is very useful, there are still a limited number of full cp genomes available from Camellia species so far [7, 14, 17–21].

It has been proven that human interference has effects on the genetic structure, leaf nutrients and pollen morphology of Camellia [22–24]. For example, due to human overexploitation of habitats and long-term targeted selection of traits, the genetic diversity of Camellia germplasm resources has been significantly reduced [25]. Thus, it remains unclear what impact the artificially selected cultivated Camellia has had on the evolutionary mechanism of the cp genome.

Current research often ignores material differences between cultivated and wild species. After sequencing the complete chloroplast genome of CSSA (MH042531), we wanted to explore evolutionary characteristics between cultivated tea and its wild relatives [14]. To assess the variations in the chloroplast genome in wild and cultivated species of Camellia, and to detect the evolutionary characteristics of cultivated tea, we selected earlier published Camellia chloroplast genomes and conducted comparative and evolutionary analysis. This can help us to better understand the structure of the Camellia chloroplast genomes and the phylogenetic relationships among species, and provide more information about the influence of human activities on tea. We believe that this research will encourage more researchers to pay attention to tea resources.

Results

Chloroplast genome features of cultivated tea

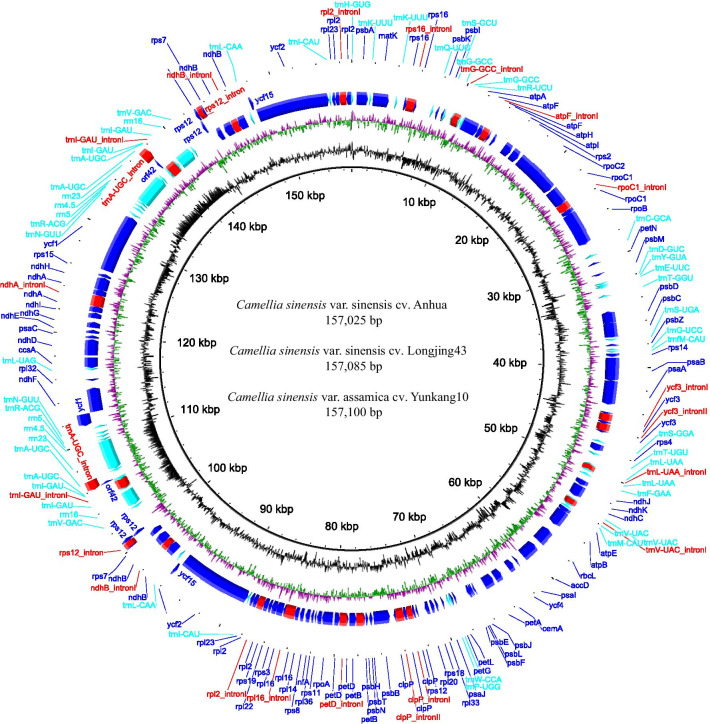

The lengths of the whole genomes of cultivated tea (CSSA, CSSL and CSAY) were slightly different, ranging from 157,025 to 157,100 bp. However, compared with CSSA and CSSL, the genome of CSAY was different. Both CSSA and CSSL contained 81 unique CDS genes, 30 tRNA, 4 rRNA and 3 pseudogenes (ψycf1, ψycf2 and ψycf15). Among them, atpF, ndhA, ndhB, petB, petD, rpl2, rpl16, rpoC1, rps16, trnG-GCC, trnI-GAU, trnL-UAA, and trnV-UAC contained a single intron, while clpP and ycf3 contained two introns. However, in CSAY, orf42 and ycf15 were lost, and rps12 and trnA-UGC had an inserted intron sequence (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Gene map of the complete chloroplast genome of cultivated tea. The inner circle corresponds to the GC content, and the next circle corresponds to the GC skew. The next three circles correspond to the genes. Genes with clockwise arrows represent reverse strands, while genes with counterclockwise arrows represent forward strands. Blue, red and aqua colors of the blocks represent protein-coding genes, introns and RNA, respectively. The third circle corresponds to the shared genes among three cultivated tea. The fourth circle corresponds to the unique genes of Camellia sinensis var. sinensis Anhua and Camellia sinensis var. sinensis Longjing43. The fifth circle corresponds to the unique genes of Camellia sinensis var. assamica cv. Yunkang10

Comparison of chloroplast genomes between cultivated tea and wild tea

In our study, first, we compared CSS with its two cultivated species (CSSA and CSSL). These species were defined as the Chinese cultivated type. Then, we compared CSA with its one cultivated species (CSAY). These species were defined as the Assam cultivated type. Finally, we compared CSS, CSA and 12 wild but related species: Camellia azalea (CAZ), Camellia crapnelliana (CCR), Camellia cuspidate (CCU), Camellia grandibracteata (CGR), Camellia impressinervis (CIM), Camellia petelotii (CPE), Camellia pitardii (CPI), Camellia pubicosta (CPU), Camellia reticulata (CRE), Camellia sinensis var. pubilimba (CSP), Camellia taliensis (CTA) and Camellia yunnanensis (CYU). These species were defined as the wild type (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Chloroplast genomic features of seventeen Camellia species

| Species | CSS | CSSA | CSSL | CSA | CSAY | CSP | CGR | CTA | CIM | CPU | CAZ | CPI | CRE | CCR | CCU | CPE | CYU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome(bp) | 157,117 | 157,025 | 157,085 | 157,028 | 157,100 | 157,086 | 157,127 | 156,974 | 156,892 | 157,076 | 157,039 | 156,585 | 156,971 | 156,997 | 156,618 | 157,121 | 156,592 |

| CDS (bp) | 80,542 | 80,620 | 80,650 | 79,093 | 79,092 | 80,622 | 80,656 | 79,577 | 79,655 | 80,665 | 80,629 | 79,619 | 76,224 | 79,649 | 79,643 | 80,650 | 79,655 |

| Introns (bp) | 15,192 | 15,196 | 15,198 | 17,902 | 17,902 | 15,210 | 15,205 | 16,947 | 16,897 | 15,198 | 15,195 | 16,937 | 15,182 | 16,239 | 16,917 | 15,196 | 16,935 |

| IGS (bp) | 49,535 | 49,361 | 49,389 | 48,200 | 48,268 | 49,405 | 49,418 | 48,591 | 48,481 | 49,365 | 49,367 | 48,171 | 53,717 | 49,321 | 48,199 | 49,427 | 48,143 |

| tRNA (bp) | 2802 | 2802 | 2802 | 2789 | 2790 | 2802 | 2802 | 2813 | 2813 | 2802 | 2802 | 2812 | 2802 | 2742 | 2813 | 2802 | 2813 |

| rRNA (bp) | 9046 | 9046 | 9046 | 9044 | 9048 | 9047 | 9046 | 9046 | 9046 | 9046 | 9046 | 9046 | 9046 | 9046 | 9046 | 9046 | 9046 |

| Genes | 115 | 115 | 115 | 113 | 113 | 115 | 115 | 115 | 115 | 115 | 115 | 115 | 115 | 114 | 115 | 115 | 115 |

| CDS genes | 81 | 81 | 81 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 |

| tRNA genes | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Introns | 18 | 18 | 18 | 22 | 22 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 18 | 21 |

| Genome GC | 37.3 | 37.3 | 37.29 | 37.3 | 37.29 | 37.32 | 37.29 | 37.32 | 37.33 | 37.3 | 37.3 | 37.34 | 37.31 | 37.3 | 37.31 | 37.29 | 37.33 |

| CDS GC | 37.58 | 37.57 | 37.56 | 37.47 | 37.47 | 37.58 | 37.56 | 37.57 | 37.54 | 37.57 | 37.56 | 37.56 | 37.54 | 37.54 | 37.56 | 37.56 | 37.54 |

| Introns GC | 36.41 | 36.38 | 36.38 | 37.91 | 37.91 | 36.42 | 36.39 | 37.25 | 37.28 | 36.42 | 36.41 | 37.22 | 36.4 | 37.54 | 37.25 | 36.41 | 37.25 |

| IGS GC | 32.93 | 32.94 | 32.94 | 32.48 | 32.46 | 32.97 | 32.94 | 32.68 | 32.72 | 32.93 | 32.95 | 32.71 | 33.39 | 32.64 | 32.63 | 32.92 | 32.68 |

| tRNA GC | 52.86 | 52.86 | 52.86 | 52.99 | 52.97 | 52.86 | 52.86 | 52.86 | 52.9 | 52.89 | 52.86 | 52.92 | 52.86 | 52.88 | 52.9 | 52.86 | 52.9 |

| rRNA GC | 55.39 | 55.41 | 55.41 | 55.40 | 55.39 | 55.41 | 55.41 | 55.38 | 55.41 | 55.42 | 55.39 | 55.36 | 55.34 | 55.41 | 55.38 | 55.39 | 55.41 |

| Gene losses |

orf42, ycf1, ycf15 |

orf42, ycf1, ycf15 |

orf42, ycf1 |

orf42, ycf1 |

orf42, ycf1 |

orf42, ycf1, trnG |

orf42, ycf1 |

orf42, ycf1 |

|||||||||

| Intron losses | rps12 | rps12 | rps12 | rps12 | rps12 | rps12 | rps12 | rps12 | rps12 |

CSS: Camellia sinensis var. sinensis, CSSA: Camellia sinensis var. sinensis cv. Anhua, CSSL: Camellia sinensis var. sinensis cv. Longjing43, CSA: Camellia sinensis var. assamica, CSAY: Camellia sinensis var. assamica cv. Yunkang10, CSP: Camellia sinensis var. pubilimba, CSP; Camellia grandibracteata, CTA: Camellia taliensis, CIM: Camellia impressinervis, CPU: Camellia pubicosta, CAZ: Camellia azalea, CPI: Camellia pitardii, CRE: Camellia reticulata, CCR: Camellia crapnelliana, CCU: Camellia cuspidate, CPE: Camellia petelotii, CYU: Camellia yunnanensis

Table 2.

Information regarding the complete chloroplast genomes of the research species

| Species | Accession number | Subgenus1 | Section1 | Types | Sample location | Location | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camellia sinensis var. sinensis | KJ806281 | Thea | Thea | Wild | Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Science | Yunnan, China | [66] |

| Camellia sinensis var. sinensis cv. Anhua | MH042531 | Thea | Thea | Cultivar | Hunan City University | Hunan, China | [14] |

| Camellia sinensis var. sinensis cv. Longjing43 | KF562708 | Thea | Thea | Cultivar | Huajiachi campus of Zhejiang University | Zhejiang, China | [17] |

| Camellia sinensis var. assamica | MH394410 | Thea | Thea | Wild | Kunming Institute of Botany, Kunming | Yunnan, China | [21] |

| Camellia sinensis var. assamica cv. Yunkang10 | MH019307 | Thea | Thea | Cultivar | Menghai County | Yunnan, China | [67] |

| Camellia sinensis var. pubilimba | KJ806280 | Thea | Thea | Wild | Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Science | Yunnan, China | [66] |

| Camellia grandibracteata | NC024659 | Thea | Thea | Wild | Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Science | Yunnan, China | [66] |

| Camellia taliensis | NC022264 | Thea | Thea | Wild | Kunming Institute of Botany | Yunnan, China | [7] |

| Camellia impressinervis | NC022461 | Thea | Archecamellia | Wild | Kunming Institute of Botany | Yunnan, China | [7] |

| Camellia pubicosta | NC024662 | Thea | Corallina | Wild | International Camellia Species Garden | Zhejiang, China | [66] |

| Camellia azalea | NC035574 | Camellia | Camellia | Wild | Yangchun County | Guangdong, China | [19] |

| Camellia pitardii | NC022462 | Camellia | Camellia | Wild | Kunming Institute of Botany | Yunnan, China | [7] |

| Camellia reticulata | NC024663 | Camellia | Camellia | Wild | Kunming Institute of Botany | Yunnan, China | [66] |

| Camellia crapnelliana | NC024541 | Camellia | Heterogenea | Wild | Kunming Botanical Garden | Yunnan, China | [20] |

| Camellia cuspidata | NC022459 | Thea | Theopsis | Wild | Kunming Institute of Botany | Yunnan, China | [7] |

| Camellia petelotii | NC024661 | Thea | Archecamellia | Wild | International Camellia Species Garden | Zhejiang, China | [66] |

| Camellia yunnanensis | NC022463 | Camellia | Heterogenea | Wild | Kunming Institute of Botany | Yunnan, China | [7] |

1 The taxonomic classification of Camellia is based on Ming’s research [47]

Chloroplast genomic similarity

In the Chinese cultivated type, the average length across the cultivated species was 62 bp smaller than CSS. In the Assam cultivated type, the genome length of CSAY was 72 bp larger than CSA. In the wild type, the average length of the wild species was 156,923 bp, which was 194 bp and 105 bp variation compared with CSS and CSA, respectively. This showed that there was less length variation when comparing cultivated species with wild species (Table 1). Similarly, the number of genes and the GC content of cultivated species were more stable than that of wild species. After comparing the genes and introns insertion or deletion among the Chinese cultivated type, Assam cultivated type and wild type, we found that introns of the rps12 gene were deleted in CSS and its two cultivated species. The orf42, ycf1 and ycf15 genes were deleted in CSA and CSAY. However, these events occurred randomly in wild species. The differences in the GC content of the CDS, intron and IGS in the Chinese cultivated type and Assam cultivated type were approximately 0.01–0.03%, and 0–0.02%, respectively, but we found that the differences of the CDS, intron and IGS in the wild type were 0.02–1.05%.

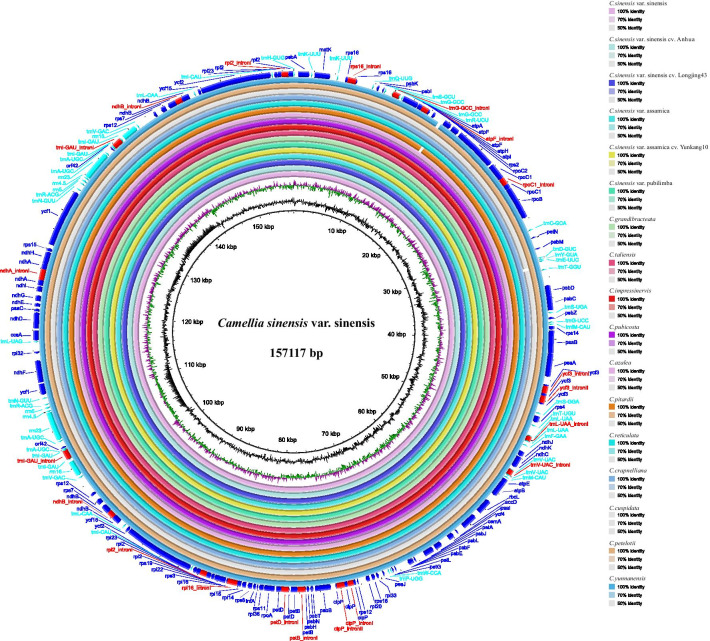

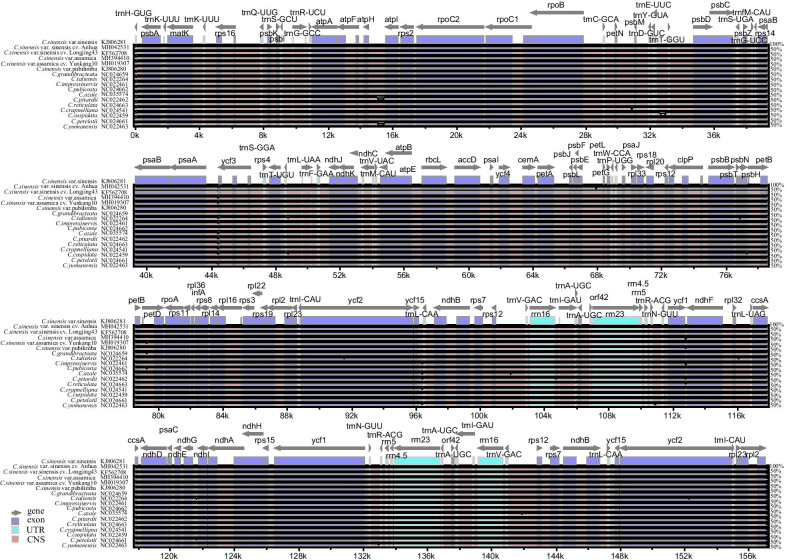

mVISTA and Blast Ring Image Generator (BRIG) were used to compare the genomic sequence identity. Comparing CSS and CSA with their cultivated types, the regions with relatively low identity were psaA_ycf3, petL_petG and ycf1_ndhF. Comparing CSS and CSA with other wild types, the regions with relatively low identity were atpH_atpI, trnE-UCC_trnT-GGU, psaA_ycf3, ycf15_trnL-CAA, ycf1_ndhF and ndhG_ndhI (Figs. 2 and 3). In conclusion, at the genomic level, the cultivated species were more conserved than the wild species.

Fig. 2.

The sequence identity of seventeen Camellia species. The inner circle is the reference genome. Next circles represent the sequence identity between C.sinensis var. sinensis and sixteen other species. The outermost circle corresponds to the protein-coding genes and intergenic spacer regions. Genes with clockwise arrows represent reverse strands, while genes with counterclockwise arrows represent forward strands

Fig. 3.

Alignment visualization of the seventeen Camellia chloroplast genome sequences using C.sinensis var. sinensis as a reference. The vertical scale indicates the percentage of identity, ranging from 50 to 100%. Arrows indicate the annotated genes and their transcriptional direction. The different colored boxes correspond to exons, tRNA or rRNA, and noncoding sequences (CNSs)

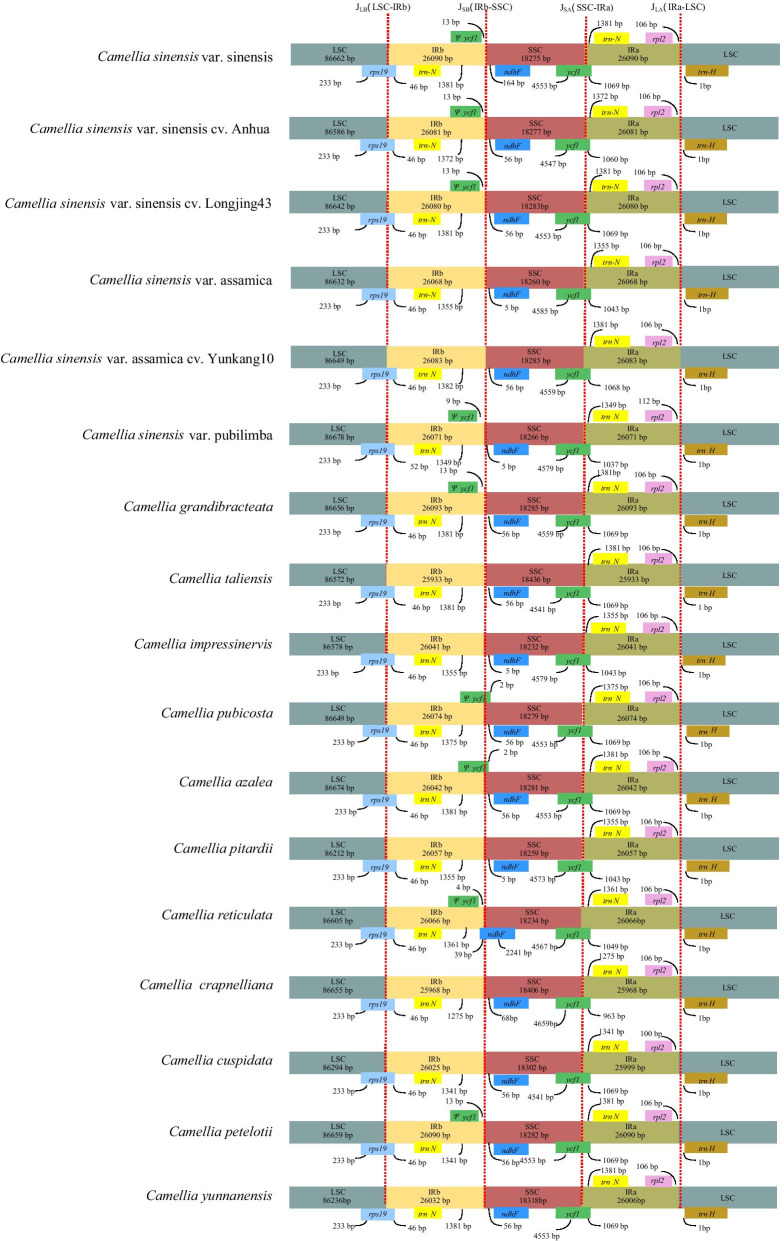

The expansion and contraction of IR regions

The locations of inverted repeat (IR) regions were extracted via a self-BLASTN search, and the characteristics of the IR/Large single copy region (LSC) and IR/Small single copy region (SSC) boundary regions were analyzed. The IRs boundary regions of the 17 complete Camellia cp genomes were compared, showing slight differences in junction positions (Fig. 4). In order to detect possible IR border polymorphisms, first of all, we compared the four IR boundaries of the Chinese cultivated type. No difference was found at the LSC/IRb or IRa/LSC border; meanwhile, only minor differences were discovered at the IRb/SSC and SSC/IRa borders. Next, we compared the four IR boundaries of the Assam cultivated type, and the results were similar. Then, we compared the cp genome boundaries of the wild type. The rps19 gene at the LSC/IRb boundary expanded 52 bp from the LSC region to the IRb side in CPU, while it stopped at 46 bp from the LSC region in the rest of the species. On the other side of the IRa/LSC boundary, the lengths of the spacers between the IRa/LSC junction and the rpl2 gene (in IRa) were 112 bp for CPU, while those of the rest of the species were all 106 bp. Consistently, in all of the compared cp genomes, the ycf1 gene spanned the SSC/IRa region and the length of ycf1 ranged from 963 to 1069 bp in IRa. Remarkably, most species have an ycf1 pseudogene at the IRa/LSC junction, while this was not observed in CSA, CTA, CIM, CPI, CCR, CCU, or CYU. Similar to most plants, the ndhF gene involved in photosynthesis was located in the SSC region. However, the ndhF gene was located at the IRb/SSC boundary of CRE, and there was a 35 bp overlap between ndhF gene and ψycf1gene.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of IR boundary regions among the 17 Camellia chloroplast genomes, using C. sinensis var. sinensis as the reference. Boxes above or below the line are forward strands and reverse strands, respectively

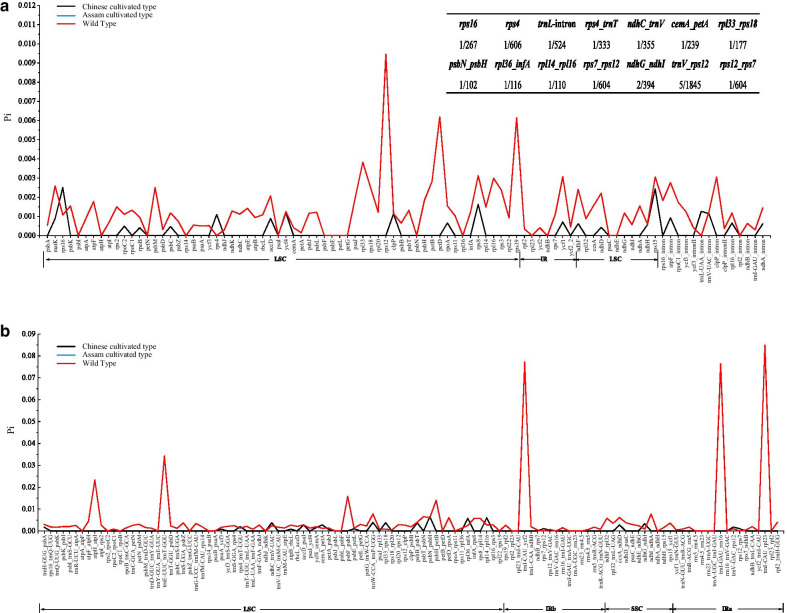

Nucleotide diversity

Comparisons based on the nucleotide diversity (Pi) values of the Chinese cultivated type, Assam cultivated type, and wild type were presented, including the intergeneric regions (IGS), protein-coding genes and introns (Additional file 1: Table S1, Fig. 5). In our study, the average Pi values for the genes, introns and IGS in wild type were approximately 6.6, 3.5 and 9.1 times that of the Chinese cultivated type. In addition, the Pi values for all regions in the Assam cultivated type were 0. Comparing Chinese cultivated type with wild type, the Pi values of most genes, introns and IGS in the wild species were higher than those of in the cultivated species. For example, rps12, petD, rps19, trnI-CAU_rpl23, trnI-CAU_ycf2, trnI-GAU_rrn16, clpP_intron, rps16_intron, and atpF_intron were highly variable in the wild species, but they were not variable in the three cultivated species. For the photosynthetic genes, except for ndhD, ndhF, ndhH and psbC, the Pi values of the photosynthetic genes of three cultivated tea were 0. The Pi values of these genes were smaller than that of the wild species. These results indicate that these genes and noncoding regions were more conserved among the cultivated species than among the wild species.

Fig. 5.

Comparative analysis of nucleotide variability (Pi) values among Chinese cultivated type, Assam cultivated type and wild type. X-axis: the names of protein-coding genes, introns or intergenic regions, Y-axis: nucleotide diversity of each window

Furthermore, although the average Pi values of the cultivated species were lower, we still found that the Pi values of rps16, rps4, trnL-UAA_intron, rps4_trnT-UGU, ndhC_trnV-UAC, cemA_petA, rpl33_rps18, psbN_psbH, rpl36_infA, rpl14_rpl16, rps7_rps12, ndhG_ndhI, trnV-GAC_rps12, and rps12_rps7 in the Chinese cultivated type were higher than those in wild species, and these difference sequences were mainly located in the LSC region (Fig. 5).

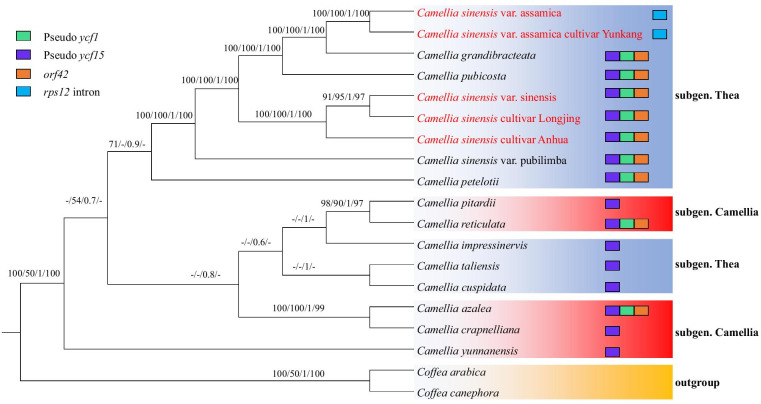

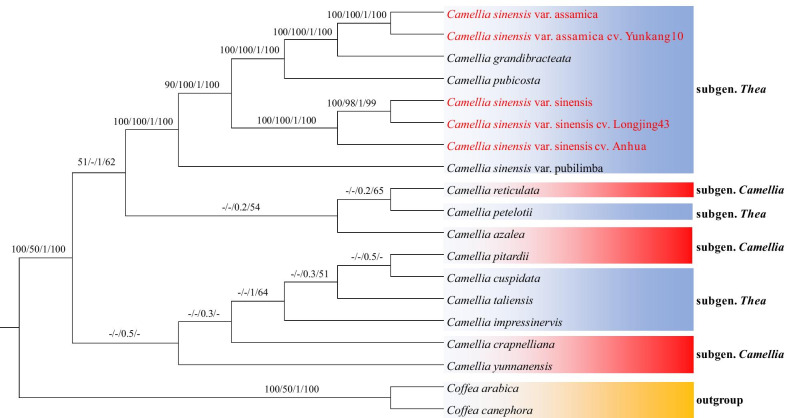

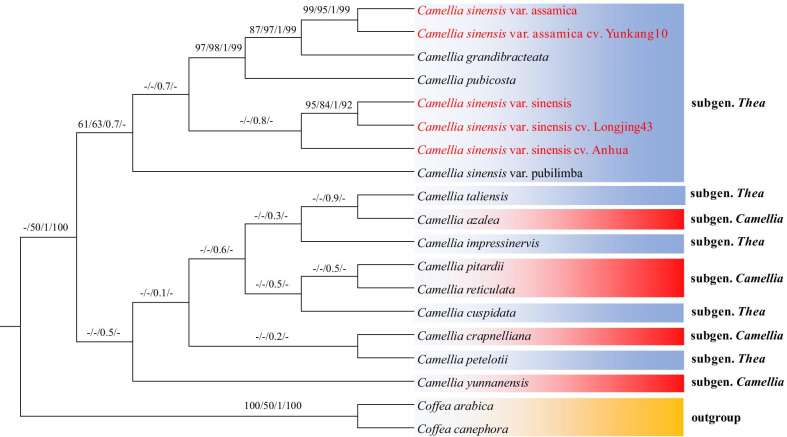

Phylogenetic analysis of cultivated tea and wild tea

We constructed three phylogenetic trees of cultivated and wild tea, namely, the complete cp genomic tree (complete cp-Tree), all shared protein coding genes among all species tree (SCDS-Tree) and the ycf1 gene tree (ycf1-Tree) (Figs. 6, 7 and 8). All phylogenetic trees supported the hypothesis that the Thea subgenus could be divided into two clades: clade I, including CSS, CSSL, CSSA, CSA, CSAY, CGR, CPU and CSP, and clade II, including CPE CIM, CTA and CCU. Clade I was strongly supported, because the posterior probabilities or bootstrap values obtained by neighbor-joining (NJ), maximum parsimony (MP), Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) were very high for each lineage. These results suggested that the seven species in clade I were closely related. All phylogenetic trees proved that CSS was the closest relative to CSSA and CSSL, and CSA was the closest relative to CSAY. In particular, in the ycf1-Tree, the posterior probabilities or bootstrap values of these species were lower than those of the complete cp-Tree and the SCDS-Tree. The value of CSSA was less than 50%. These results suggested that the ycf1 gene has diverged in cultivated tea.

Fig. 6.

The phylogenetic tree of Camellia species based on the complete cp genomes (complete cp-Tree). Coffea canephora and Coffea arabica were selected as the outgroup. Tree were constructed by neighbor-joining (NJ), maximum parsimony (MP), Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) with bootstrap values or posterior probabilities above the branches, respectively. Bootstrap values less than 50% are represented by "-". As indicated in the legend at the top left, the unique genes and introns of each species were plotted onto branches using colored squares

Fig.7.

The phylogenetic tree of Camellia species based on the all shared coding protein genes among all species (SCDS-Tree). Coffea canephora and Coffea arabica were selected as the outgroup. Tree were constructed by neighbor-joining (NJ), maximum parsimony (MP), Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) with bootstrap values or posterior probabilities above the branches, respectively. The bootstrap values less than 50% are represented by "-"

Fig. 8.

The phylogenetic tree of Camellia species based on the ycf1 gene (ycf1-Tree). Coffea canephora and Coffea arabica were selected as the outgroup. Tree were constructed by neighbor-joining (NJ), maximum parsimony (MP), Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) with bootstrap values or posterior probabilities above the branches, respectively. The bootstrap values less than 50% are represented by "-"

In addition, we found conflict among the three trees (Figs. 6, 7 and 8). The topological structures consisting of the Camellia subgenus (CPI, CRE, CAZ, CCR, and CYU) and the Thea subgenus (CPE, CIM, CTA and CCU) were poorly supported by the complete cp-Tree, SCDS-Tree and ycf1-Tree, because most bootstrap values or posterior probabilities were less than 50% for each lineage. These results may be caused by unbalanced sampling.

The cp-Tree showed some structural variations among the Camellia cp genomes (Fig. 6). The clade, which was made up of CSS, CSSL, CSSA, CSA, CSAY, CGR, CPU, CSP and CPE, was characterized by the rps12 intron deletion, the ψycf1 gene, and the ψycf15 gene (except for CSA and CSAY). The other species, except for CRE and CAZ, had lost the ψycf1 gene and the orf42 gene.

Chloroplast genome variation and evolution in cultivated tea

To explain the changes in the cp genome structure of the cultivated tea group, we detected single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and insertion/deletion (indel) in the cp genome of cultivated tea. In the Chinese cultivated type, after comparing the whole cp genome of three species, 67 SNPs and 46 indels were found. The LSC, IRb, SSC and IRa regions contained 43, 3, 13, and 8 SNPs and 37, 2, 5, and 2 indels, respectively (Additional file 2: Table S2). Most of the SNPs and indels were located in the noncoding region (IGS and intron). There were 39 SNPs and 41 indels in this region, while 28 SNPs and 5 indels were found in the protein coding region. The two ycf1 genes, which are located at the junction of SSC and IRa, contained the most SNPs and indels, 6 and 2, respectively. For the photosynthetic genes, psbC, ndhD, ndhF and ndhH presented SNP variations, while the psbI gene presented indel variation. For the 14 sequences with higher Pi values in cultivated species than in wild species, trnV-GAC_rps12 and ndhG_ndhI contained the most abundant SNPs, with 5 and 2 respectively (Fig. 5). In the Assam cultivated type, after comparing the whole cp genome of two species, 4 indels were found, but no SNPs. All indels were located in the IGS region. In particular, a long sequence (77 bp) was inserted into the IRb/SSC boundary region (Additional file 3: Table S3).

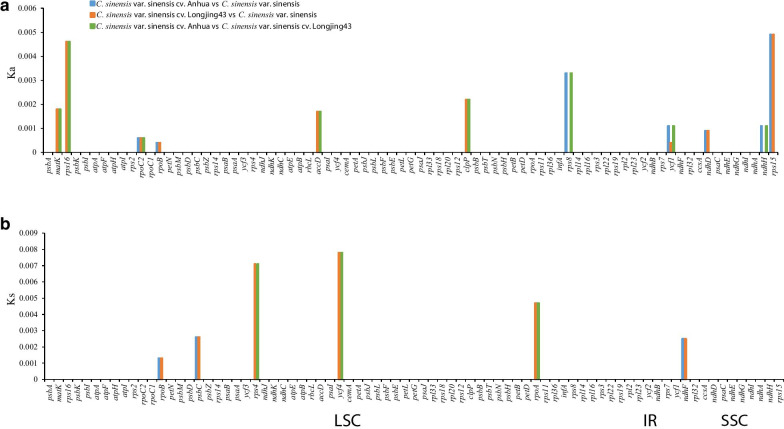

To have a clear view of the evolution of cultivated species, we used their 80 shared protein coding genes to calculate their nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution (Ka) rates, synonymous nucleotide substitution (Ks) rates and Ka/Ks ratio. First, we compared CSS and its cultivated species. The results showed that only 16 protein coding genes had synonymous or nonsynonymous mutations (Fig. 9, Additional file 4: Table S4). Among them, there were nonsynonymous mutations in matK, rps16, rpoC2, rpoB, accD, clpP, rps8, ycf1, ndhD, ndhH and rps15. The genes with the highest rate of nonsynonymous mutations were rps16, rps8 and rps15. There were synonymous mutations in rpoB, psbC, rps4, ycf4, rpoA and ndhF. The highest mutation rates were rps4, ycf4 and rpoA. Of the 80 genes, 79 had a Ka / Ks value of 0, and only rpoB, had a Ka/Ks value of 0.3004 < 0.5, suggesting very strong purifying selective pressure. Then, we compared CSA and its cultivated species. However, no protein coding genes had synonymous or nonsynonymous mutations, suggesting very strong purifying selective pressure (Additional file 5: Table S5).

Fig. 9.

Nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution (Ka) and synonymous nucleotide substitution (Ks) of homologous protein-coding genes from C. sinensis var. sinensis, C. sinensis var. sinensis cv. Longjing43 and C. sinensis var. sinensis cv. Anhua

The site specific selection events of 16 genes with synonymous or non-synonymous mutations were analyzed by Bayesian Empirical Bayes (BEB), and we found that some amino acid sites of ycf1 and rps15 exhibited site-specific selection (Additional file 6: Table S6). In ycf1, there were six sites under positive selection, and in rps15, there was one site under positive selection. For example, in the rps15 gene, the codon ACC (threonine) of CSS was mutated to AAC (asparagine) in two cultivated species.

Discussion

Understanding the genetic variation between cultivated and wild species is crucial for introducing interesting traits from wild species into cultivars [26]. Organelle genome sequencing has proven to be an effective way to resolve phylogenetic relationships among closely related species [27, 28]. Here, we constructed and compared the complete cpDNA genome sequences of three cultivars and fourteen wild species of Camellia. At the genomic level, cultivated species were more conserved than wild species, in terms of both architecture and linear sequence order (the length, genes number, genes arrangement, and GC content) (Table 2, Figs. 2 and 3). For other land plant species, such as peanuts, cherries and radishes, the cp genome size and structure, as well as the gene content and order, are highly conserved among the cultivated and wild species [29–31].

We found that the IR regions of cultivated tea had expanded or contracted. The IR length of the CSSA and CSSL was approximately 20 bp smaller than that of the CSS, accounting for 32% of the difference in the complete genome length. The IR length of the CSAY was approximately 30 bp larger than that of the CSA, accounting for 42% of the difference in the complete genome length (Fig. 4). In fact, the contraction and expansion of IRs is considered to be one of the important reasons for the cp genome length variation [32]. Further SNP and indel analysis showed that ycf1 and trnV-GAC_rps12 changed in the Chinese cultivated type, while trnN-GUU_ndhF and rrn5_trnR-ACG changed in the Assam cultivated type. In CSS and CSSL, a 9 bp sequence (TCCTTCTTC/GAAGAAGGA) was inserted into the ycf1 gene (Additional file 2: Table S2). This is suggested that ycf1 is one of the important reasons for the expansion or contraction of the IRs of the Chinese cultivated type. The same results were also found in Zheng’s study [33]. He analyzed the cp genome length variation in 272 species and found that atpA, accD and ycf1 accounted for 13% of the difference in length. Therefore, ycf1, which is associated with plant survival, may play a key role in the cp genome size variations of cultivated tea. In CSAY, a 77 bp sequence was inserted into the trnN-GUU_ndhF region (IRb/SSC boundary region) (Additional file 3: Table S3). This is the main reason for the expansion or contraction of the IRs of the Assam cultivated type.

In addition to the variations in genome size, there were also some nucleotide mutations in the cultivated species. In this study, the nucleotide diversity of cultivated tea was lower than that of wild tea (Fig. 5), but the unbalanced sampling between the 14 wild tea and 3 cultivated tea may lead to nucleotide diversity difference of cpDNA fragments. The nucleotide diversity comparison of 358 cultivated rice and 54 wild rice also presented similar results [34]. Nevertheless, we found that the nucleotide diversity of 14 sequences in the Chinese cultivated tea was higher than that of wild tea (rps16, rps4, trnL-UAA_intron, rps4_trnT-UGU, ndhC_trnV-UAC, cemA_petA, rpl33_rps18, psbN_psbH, rpl36_infA, rpl14_rpl16, rps7_rps12, ndhG_ndhI, trnV-GAC_rps12, and rps12_rps7) (Fig. 5). These sequences suggested the variations in the cp genomes of cultivated tea, and they are potential molecular markers for distinguishing Camellia species and for the phylogenetic analysis of Camellia.

Previous studies have proven that human interference had effects on the genetic structure, leaf nutrients and pollen morphology of Camellia. Yan et al. analyzed the genetic relationship of five semi-wild tea which due to lack of human management for a long time were studied by using genome-wide SNP. They found that human interference will affect the genetic structure of tea. After the human interference stopped, the tea from five different geographical regions could be divided into three different groups because of the absence of free pollination [22]. Xiong et al. made comparative analyses of the nutrient content in the leaves of cultivated and wild C. nitidissima. They found that cultivated C. nitidissima had significantly higher contents of essential amino acids (26.05%) and total amino acids (33.27%) than wild C. nitidissima [23]. Shu et al. proved that there are obvious differences in pollen morphology and exine morphology between cultivated and wild species of Camellia [24]. Therefore, to explore specific evolutionary characteristics between cultivated tea and its wild relatives, we subsequently performed evolutionary research on cultivated tea.

First, to have a clear view of the cp genomic adaptive evolution of cultivated tea, we performed evolutionary analysis on the protein-coding sequences. The Ka/Ks ratio is very useful for measuring selective pressure at the protein level [35]. In the Chinese cultivated type, Ka/Ks value of 79 genes was 0, and only rpoB had a value of 0.3004. In addition, some amino acids of ycf1 and rps15 exhibited site-specific selection (Additional file 4: Tables S4 and Additional file 6: S6). rpoB is crucial for genetic information transmission, and it affects the transcription of DNA into RNA and the translation of RNA into protein. They were also found to be under selective pressure in beverage crops [13]. The rps15 gene has a function in chloroplast ribosome subunits [35]. ycf1, encoding a component of the chloroplast’s inner envelope membrane protein translocon, is one of the largest plastid genes [13], and it is also essential for almost all plant lineages [36]. These positively selected genes may have played key roles in the adaptation of cultivated tea to various environments.

Generally, the deletion or insertion of amino acids in the encoded protein will affect the structure and function of this gene [37–39]. In the Chinese cultivated type, 16 protein coding genes had nucleotide substitutions, among which the ycf1 gene had the largest number of nucleotide substitution. At the same time, in ycf1, five amino acid sites exhibited site-specific selection, and a 9 bp sequence insertion was found in CSSA (Additional file 4: Table S4 and Additional file 6: S6, Fig. 9).

ycf1 has an open reading frame of unknown function, but some studies have inferred that ycf1 is very important for plant survival [33, 40]. In tobacco, a chimeric gene conferring resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics has been transferred into ycf1 in the cp genome. Then, the plantlets were cultured in plant regeneration medium containing the antibiotic spectinomycin. After that, the maintenance of a fairly constant ratio of wild-type versus transformed genome copies was found. However, the wild-type genome was still present in all samples whereas the transplastomic fragments were missing from several samples after culturing in antibiotic-free medium. This experiment proved that ycf1 encodes products that are essential for cell survival. ycf1 is also an important molecular marker of plants [41, 42], because it has higher variability than other known cp molecular markers (such as the widely used rbcL and matk genes), for both the total number of parsimony informative characters and the percent variability.

Phylogenetic analysis of cultivated and wild tea showed that CSSA and CSSL were closely related to the CSS, and CSAY was closely related to CSA (Figs. 6 and 7), which supports the previous finding that most of the cultivated tea originated directly from CSS and CSA [43]. However, in the ycf1-Tree, the posterior probabilities or bootstrap values of the cultivated tea branch were lower than that of the complete cp-Tree and the SCDS-Tree, which suggested that the ycf1 gene has diverged in cultivated tea (Figs. 6, 7 and 8). Similar results have been found in Corylus [44]. The ycf1 gene of Corylus chinensis and Corylus avellana have a similar evolutionary history, which is different from that of Corylus heterophylla. This evolution of cultivated plants may be related to the utilization efficiency of photosynthesis. Photosystem biogenesis regulator 1 (PBR1), the RNA binding protein encoded by the nuclear genome, can improve the translation efficiency of ycf1 in the Arabidopsis thaliana cp genome. Additionally, the symbiosis and stability maintenance of the three photosynthetic complexes are regulated [45]. However, at present, the effect of mutations in the single amino acid site and the insertion or deletion of the short sequence on the function of ycf1 is still not clear, and cultivated tea may provide important materials for this kind of research.

In the phylogenetic trees, CSS, CSA, CGR and CPU formed a monophyletic clade with 100% bootstrap values. CSS, CSA and CGR were classified into the sect. Thea, but CPU was classified into the sect. Corallina (Table 2). This indicates that CPU and sect. Thea plants have close genetic relationship. It also supports the result of Huang’s research [18]. However, CTA belongs to sect. Thea, together with two species of sect. Archecamellia and one species of sect. Theopsis that were located in another clade, which indicates that the phylogenetic direction of CTA is different from that of the other sect. Thea species. CTA is often considered to be a wild relative of cultivated tea [43]. Both are monoecious, insect-pollinated and outcrossing species. However, there are differences in their morphological characters. For example, CTA has the features of 5-locule ovaries and large sepals and petals, whereas CSS has features of 3-locule ovaries and small sepals and petals [46, 47]. Based on the evidence of the chloroplast genome, we hypothesized that CTA and CSS have different genetic polymorphism. In this study, CIM and CPE were not clustered into the same branch. The taxonomy of CIM is controversial. CIM and CPE were classified into the sect. Archecamellia by Ming et al. [47], while Chang et al. [46] classified CIM into the sect. Chrysantha. Therefore, we infer that it is not acceptable to combine the sect. Archecamellia and the sect. Chrysantha. In the subgenus Camellia, CPI and CRE formed a clade, as did CAZ and CCR, and the bootstrap value was 97–100%. Among them, CPI, CRE and CAZ are all sect. Camellia plants, while CCR is classified into sect. Heterogenea [47] or sect. Furfuracea [46]. However, both morphological and molecular characteristics indicate that CCR is closely related to some plants in sect. Camellia [48].

Conclusion

In this work, the complete cp genomes of three cultivated species and 14 wild species of Camellia were studied. Genomic variation and evolutionary processes were compared in these species. Genomic variation analyses showed that the cultivated species were more conserved than the wild species in terms of architecture and linear sequence order. In the Assam cultivated type, the variation in the chloroplast genome was mainly manifested by sequence insertion of IGS regions. In the Chinese cultivated type, the variation in the chloroplast genome was mainly manifested by the nucleotide polymorphism and sequence insertion of some sequences. These nucleotide polymorphisms also led to the mutation of amino acid sites in some genes, among which ycf1 was the gene with the most mutation sites. In addition to amino acid mutations, there was a 9 bp base insertion in the ycf1 gene. ycf1 is believed to be a critical gene for plant survival, and it may influence photosynthesis and be related to plant adaptation. Evolutionary processes analyses showed that CSA and its cultivated species were tightly clustered, while CSS and its cultivated species were not tightly clustered. The evolutionary relationship between CSS and CSSL was closer than that with CSSA in the ycf1-Tree. However, at present, the effect of the mutation in the single amino acid site and insertion or deletion of the short sequence on the function of ycf1 are still not clear, and cultivated tea may provide important materials for this kind of research.

Methods

Genomic materials collection of cultivated tea

The complete cp genome of CSSA has been presented and annotated in our previous study [14] with GenBank accession number MH042531. Meanwhile, we searched in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) dataset to find the published cultivated tea’s complete cp genomes, and only CSSL and CSAY with accession numbers KF562708 and MH019307 have been published [17]. Gene map of the three cultivated tea was generated using BRIG [49].

Comparative analysis between cultivated tea and wild tea

The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) was used to find closely related cp genomes of CSSA in NCBI. After the cp genome of Camellia was screened, 17 Camellia cp genomes with sampling information remained, including 3 cultivated species (CSSA, CSSL and CSAY) and 14 wild species (Table 2). Previous studies have shown that both CSSA and CSSL originated directly from CSS, while CSAY originated directly from CSA [43, 49]. Therefore, we used CSS and CSA as the reference sequence to study the genomic variations and evolution direction between cultivated tea and wild tea.

Three methods were used for comparative genomic analysis: (I) The comparison of the cp genomic sequence identity was based on the method of Li [50] using mVISTA in Shuffle-LAGAN mode and BRIG, respectively. (II) The comparison of the expansion and contraction of IR regions was presented. First, we annotated and extracted the IR boundary of the Camellia cp genomes by Plastid Genome Annotator (PGA) [51]. Then, the IR boundary regions were visualized by using Visio professional 2016. (III) Comparisons based on the Pi values of the Chinese cultivated type, Assam cultivated type, and wild type were performed according to the method of Njuguna [52]. First, we used annotation information to extract intergenic regions, protein coding genes and intron regions of 17 Camellia species in Tbtools v0.6666 [53]. After comparing these sequences, 211 loci shared among Camellia species were found, including 80 protein coding genes, 117 intergenic regions, and 14 intron regions. Each loci was divided into three datasets: (I) the sequences consisted of the Chinese cultivated type, (II) the sequences consisted of the Assam cultivated type; (III) the sequences consisted of wild type. Each sequence was aligned using clustal alignment with default settings in MEGA7.0 [54]. The Pi of these regions was calculated using DnaSP v6.10.04 [55] to show divergence at sequence level.

Phylogenetic analysis of Camellia

Three datasets were used to construct the following phylogenetic trees of Camellia: (I) the complete cp genomes, (II) the all shared protein coding genes among all species (SCDS), and (III) ycf1 gene sequences. First, all datasets were aligned using MAFFT v7.380 [56] under the FFT-NS-2 default setting. The alignments were used for phylogenetic analysis. After that, according to the method described by Xie et al. [57] and Zhang et al. [58], we used four methods to construct phylogenetic trees: NJ method, MP method, BI method and ML method. Coffea canephora and Coffea arabica were selected as the outgroup.

The NJ analysis was reconstructed via MEGA7.0 [54] under the default settings with 1000 bootstrap values. The MP analysis was performed in PAUP 4.0a167 [59] with heuristic searches with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The BI analysis was performed with Mrbayes 3.2.7 [60] under the best substitution models and parameters. The analysis parameters were set as four chains that were run simultaneously for 10,000,000 generations or until the average standard deviation of the split frequencies fell below 0.01. The best substitution models and parameters were computed by jmodeltest 2.1.7 [61]. The ML analysis was carried out in IQ-TREE [62] using the default settings, with 1000 bootstrap values for tree evaluation. The best substitution models were computed by IQ-TREE. All the best substitution models mentioned earlier were listed in Additional file 7: Table S7.

Evolutionary analysis of cultivated tea

After alignment of the cultivated and wild species, the number and position of SNPs and indels in the genomes were presented in DnaSP v6.10.04 according to the Wu’s method [63].

The Ka and Ks rates as well as the Ka/Ks ratio in the homologous protein-coding genes were used to evaluate the adaptive evolution of the cultivated species. After aligning each gene using the ClustalW (Codons) program in MEGA7.0, the Ks, Ka and Ka/Ks values of each gene were determined according to Dong’s method [64] with the program from the PAML package [65]. For identification of site-specific selection, four models, M1 (neutral), M2 (selection), M7 (beta) and M8 (beta & ω), were used in codeml from the PAML package. The BEB was used to calculate the posterior probabilities for site classes. Only sites with posterior probabilities > 0.9 were selected.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Comparative analysis of nucleotide variability (Pi) values among the Chinese cultivated type, Assam cultivated type and wild type

Additional file 2: Table S2. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and insertion/deletion (indel) information from comparisons among C. sinensis var. sinensis, C. sinensis var. sinensis cv. Longjing43 and C. sinensis var. sinensis cv. Anhua

Additional file 3: Table S3. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and insertion/deletion (indel) information from comparisons between C. sinensis var. assamica and C. sinensis var. sinensis assamica cv. Yunkang10

Additional file 4: Table S4. Nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution (Ka) and synonymous nucleotide substitution (Ks) rates, as well as the Ka/Ks ratio of homologous protein-coding genes from C. sinensis var. sinensis, C. sinensis var. sinensis cv. Longjing43 and C. sinensis var. sinensis cv. Anhua

Additional file 5: Table S5. Nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution (Ka) and synonymous nucleotide substitution (Ks) rates, as well as the Ka/Ks ratio of homologous protein-coding genes from C. sinensis var. assamica and C. sinensis var. sinensis assamica cv. Yunkang10

Additional file 6: Table S6. Positive selection sites identified among 16 genes with synonymous or nonsynonymous mutations

Additional file 7: Table S7. The best substitution models in the phylogenetic analysis of Camellia

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate Dr. Huang Hui—from Kunming Institute of Botany—for providing us with the samples collection information of Camellia species. We also thank Chen Yi for the help during the analysis process.

Abbreviations

- BEB

Bayesian Empirical Bayes

- BI

The Bayesian inference

- BRIG

Blast Ring Image Generator

- CAZ

Camellia azalea

- CCR

Camellia crapnelliana

- CCU

Camellia cuspidate

- CDS

Protein-coding regions

- CGR

Camellia grandibracteata

- CIM

Camellia impressinervis

- cp

Chloroplast

- CPE

Camellia petelotii

- CPI

Camellia pitardii

- CPU

Camellia pubicosta

- CRE

Camellia reticulate

- CSA

Camellia sinensis var. assamica

- CSSA

Camellia sinensis var. sinensis cv. Anhua

- CSSL

Camellia sinensis var. sinensis cv. Longjing43

- CSP

Camellia sinensis var. pubilimba

- CSS

Camellia sinensis var. sinensis

- CTA

Camellia taliensis

- CYU

Camellia yunnanensis

- IGS

Intergeneric regions

- Indel

Insertion/deletion

- IR

Inverted repeat

- Ka

Nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution

- Ks

Synonymous nucleotide substitution

- LSC

Large single copy region

- ML

The maximum likelihood

- MP

The maximum parsimony

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NJ

The neighbor-joining

- PBR1

Photosystem biogenesis regulator 1

- PGA

Plastid Genome Annotator

- Pi

Nucleotide diversity

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SSC

Small single copy region

Authors' contributions

JP and ZXG conceived the study. All authors collected field samples. MD, SLQ, ZHY, XZF analyzed the final data. YZL and ZXG acquired funds for this study. JP wrote the original manuscript, and all authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Key Projects of National Forestry and Grassland Bureau (201801), Forestry Science and Technology Project of Hunan Province (XLK201920), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2019JJ50027), Postgraduate Scientific Research Innovation Project of Hunan Province (CX20200711) and Scientific Innovation Fund for Post-graduates of Central South University of Forestry and Technology (CX20201010). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Raw sequences data of CSSA were submitted to National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database with accession number MH042531. Other genomic data mentioned in the article can be accessed from NCBI and the details of accession number has been provided in Table 2.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zohary D. Domestication of crop plants. In: Levin SA, editor. Encyclopedia of biodiversity. New York: Elsevier; 2001. pp. 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denison RF, Kiers ET, West SA. Darwinian agriculture: when can humans find solutions beyond the reach of natural selection? Q Rev Biol. 2003;78(2):145–168. doi: 10.1086/374951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matesanz S, Gianoli E, Valladares F. Global change and the evolution of phenotypic plasticity in plants. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1206:35–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuniyuki Saitoh KN. Toshiro Kuroda: characteristics of flowering and pod set in wild and cultivated types of soybean. Plant Prod Sci. 2004;7(2):172–177. doi: 10.1626/pps.7.172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aharoni A, Giri AP, Verstappen FWA, Bertea CM, Sevenier R, Sun Z, Jongsma MA, Schwab W, Bouwmeester HJ. Gain and loss of fruit flavor compounds produced by wild and cultivated strawberry species. Plant Cell. 2004;16(11):3110–3131. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.023895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vijayan K, Zhang W-J, Tsou C-H. Molecular taxonomy of Camellia (Theaceae) inferred from nrITS sequences. Am J Bot. 2009;96(7):1348–1360. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang J-B, Yang S-X, Li H-T, Yang J, Li D-Z. Comparative chloroplast genomes of Camellia species. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e73053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao JY, Clifford RP, Du YQ. Collected species of the genus Camellia—an illustrated outline. Zhejiang: Zhejiang Science and Technology Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore MJ, Soltis PS, Bell CD, Burleigh JG, Soltis DE. Phylogenetic analysis of 83 plastid genes further resolves the early diversification of eudicots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(10):4623–4628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907801107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wachira F, Tanaka J, Takeda Y. Genetic variation and differentiation in tea (Camellia sinensis) germplasm revealed by RAPD and AFLP variation. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2001;76(5):557–563. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jianfei Z. Flora of China. Beijing: Flora of China Editorial Committee; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ming TL. A systematic synopsis of the genus Camellia. Acta Bot Yunnanica. 1999;21(2):3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei C, Yang H, Wang S, Zhao J, Liu C, Gao L, Xia E, Lu Y, Tai Y, She G, et al. Draft genome sequence of Camellia sinensis var. sinensis provides insights into the evolution of the tea genome and tea quality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(18):E4151–E4158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719622115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong M, Liu S, Xu Z, Hu Z, Ku W, Wu L. The complete chloroplast genome of an economic plant, Camellia sinensis cultivar Anhua, China. Mitochondrial DNA B. 2018;3(2):558–559. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1462124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen SH, Deng YS, Gong ZH, Zhu HY. Analysis of the evolution of technological innovation model of Anhua Dark Tea Industry. J Agric. 2015;5(6):96–101. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniell H, Lin CS, Yu M, Chang WJ. Chloroplast genomes: diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 2016;17:134. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye XQ, Zhao ZH, Zhu QW, Wang YY, Lin ZX, Ye CY, Fan LJ, Xu HR. Entire chloroplast genome sequence of tea (Camellia sinensis cv. Longjing 43): a molecular phylogenetic analysis. J Zhejiang Univ. 2014;40(4):404–412. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang H, Shi C, Liu Y, Mao S-Y, Gao L-Z. Thirteen Camellia chloroplast genome sequences determined by high-throughput sequencing: genome structure and phylogenetic relationships. BMC Evol Biol. 2014;14:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu X, Zheng W, Wen J. The complete chloroplast genome of the long blooming and critically endangered Camellia azalea. Conserv Genet Resour. 2018;10(1):5–7. doi: 10.1007/s12686-017-0749-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang JB, Li DZ, Li HT. Highly effective sequencing whole chloroplast genomes of angiosperms by nine novel universal primer pairs. Mol Ecol Resour. 2014;14(5):1024–1031. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng CX, Hollingsworth PM, Yang J, He ZS, Zhang ZR, Li DZ, Yang JB. Genome skimming herbarium specimens for DNA barcoding and phylogenomics. Plant Methods. 2018;14:43. doi: 10.1186/s13007-018-0300-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan G, Da-he Q, Chun Y, Yan L, Zheng-wu C, Juan C. Genetic diversity of old tea plant resources in Jiuan City of Guizhou Province, using genome-wide SNP. J Plant Genet Resour. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1917-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong Z, Qi X, Wei X, Chen Z, Tang H, Chai S. Nutrient composition in leaves of cultivated and wild Camellia nitidissima. Pak J Bot. 2012;44(2):635–638. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shu JL, Chen L, Wang HS, Wang PS, Xu M, Song WX. Pollen morphology, ultrastructure and evolution of tea plant and other genus Camellia plants. J Tea Sci. 1998;18(1):6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao DW, Yang JB, Yang SX, Kato K, Luo JP. Genetic diversity and domestication origin of tea plant Camellia taliensis (Theaceae) as revealed by microsatellite markers. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amar MH, Magdy M, Wang L, Zhou H, Zheng B, Jiang X, Atta AH, Han Y. Peach chloroplast genome variation architecture and phylogenomic signatures of cpDNA introgression in Prunus. Can J Plant Sci. 2019;99(6):885–896. doi: 10.1139/cjps-2019-0129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivanova Z, Sablok G, Daskalova E, Zahmanova G, Apostolova E, Yahubyan G, Baev V. Chloroplast genome analysis of resurrection tertiary relict Haberlea rhodopensis highlights genes important for desiccation stress response. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:204. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma PF, Zhang YX, Zeng CX, Guo ZH, Li DZ. Chloroplast phylogenomic analyses resolve deep-level relationships of an intractable bamboo tribe Arundinarieae (Poaceae) Syst Biol. 2014;63(6):933–950. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syu054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho M-S, Yoon HS, Kim S-C. Complete chloroplast genome of cultivated flowering cherry, Prunus xyedoensis 'Somei-yoshino' in comparison with wild Prunus yedoensis Matsum. (Rosaceae) Mol Breed. 2018;38(9):112. doi: 10.1007/s11032-018-0871-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Li Y, Li CJ, Yan CX, Zhao XB, Yuan CL, Sun QX, Shi CR, Shan SH. Twelve complete chloroplast genomes of wild peanuts: great genetic resources and a better understanding of Arachis phylogeny. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):504. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-2121-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamagishi H, Terachi T, Ozaki A, Ishibashi A. Inter- and intraspecific sequence variations of the chloroplast genome in wild and cultivated Raphanus. Plant Breed. 2009;128(2):172–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2008.01558.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer JD, Nugent JM, Herbon LA. Unusual structure of geranium chloroplast DNA: a triple-sized inverted repeat, extensive gene duplications, multiple inversions, and two repeat families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(3):769–773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.3.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng XM, Wang JR, Feng L, Liu S, Pang HB, Qi L, Li J, Sun Y, Qiao WH, Zhang LF, Chen YL, Yang QW. Inferring the evolutionary mechanism of the chloroplast genome size by comparing whole-chloroplast genome sequences in seed plants. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1555. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01518-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng L, Nam J, Chu SH, Rungnapa P, Min MH, Cao Y, Yoo JM, Kang JS, Kim KW, Park YJ. Signatures of differential selection in chloroplast genome between japonica and indica. Rice. 2019;12(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s12284-019-0322-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao CM, Deng YF, Wang J. The complete chloroplast genomes of Echinacanthus species (Acanthaceae): phylogenetic relationships, adaptive evolution, and screening of molecular markers. Front Plant Sci. 2019;9:1989. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong WL, Wang RN, Zhang NY, Fan WB, Fang MF, Li ZH. Molecular evolution of chloroplast genomes of Orchid species: insights into phylogenetic relationship and adaptive evolution. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3):716. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai Z, Guisinger M, Kim HG, Ruck E, Blazier JC, McMurtry V, Kuehl JV, Boore J, Jansen RK. Extensive reorganization of the plastid genome of Trifolium subterraneum (Fabaceae) is associated with numerous repeated sequences and novel DNA insertions. J Mol Evol. 2008;67(6):696–704. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dugas DV, Hernandez D, Koenen EJM, Schwarz E, Straub S, Hughes CE, Jansen RK, Nageswara-Rao M, Staats M, Trujillo JT, et al. Mimosoid legume plastome evolution: IR expansion, tandem repeat expansions, and accelerated rate of evolution in clpP. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16958. doi: 10.1038/srep16958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Y, Liu F, Yang DG, Li W, Zhou XJ, Pei XY, Liu YG, He KL, Zhang WS, Ren ZY, Zhou KH, Ma XF, Li ZH. Comparative chloroplast genomics of Gossypium species: insights into repeat sequence variations and phylogeny. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:367. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drescher A, Ruf S, Calsa T, Jr, Carrer H, Bock R. The two largest chloroplast genome-encoded open reading frames of higher plants are essential genes. Plant J. 2000;22(2):97–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong WP, Xu C, Li CH, Sun JH, Zuo YJ, Shi S, Cheng T, Guo JJ, Zhou SL. ycf1, the most promising plastid DNA barcode of land plants. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8348. doi: 10.1038/srep08348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neubig KM, Whitten WM, Carlsward BS, Blanco MA, Endara L, Williams NH, Moore M. Phylogenetic utility of ycf1 in orchids: a plastid gene more variable than matK. Plant Syst Evol. 2009;277(1–2):75–84. doi: 10.1007/s00606-008-0105-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, Yang SX, Ji PZ, Gao LZ. Phylogeography of Camellia taliensis (Theaceae) inferred from chloroplast and nuclear DNA: insights into evolutionary history and conservation. BMC Evol Biol. 2012;12:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei YL, Wen ZF, Liu F, Zhang JW, Huang WG, Lan YP, Cheng LL, Cao QC, Hu GL. Bioinformatics analysis of ycf1 gene in Corylus. J Shanxi Agric Sci. 2018;46(08):1244–1247, 1333. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang XF, Wang YT, Chen ST, Li JK, Shen HT, Guo FQ. PBR1 selectively controls biogenesis of photosynthetic complexes by modulating translation of the large chloroplast gene Ycf1 in Arabidopsis. Cell Discov. 2016;2:16003. doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2016.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang HD. Thea—a section of beveragial tea trees of the genus Camellia. Acta Sci Nat Univ Sunyatseni. 1981;1:87–99. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ming TL. A revision of Camellia sect. Thea. Acta Bot Yunnanica. 1992;14(2):115–132. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang ZD. Preliminary study of molecular phylogenetics and biogeography of the genus Camellia L. based on chloroplast DNA. 2017; Master's Thesis, Zhejiang SCI-TECH University, Hangzhou.

- 49.Alikhan N-F, Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Beatson SA. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li C, Zhao Y, Xu Z, Yang G, Peng J, Peng XY. Initial characterization of the chloroplast genome of Vicia sepium, an important wild resource plant, and related inferences about its evolution. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:73. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qu XJ, Moore MJ, Li DZ, Yi TS. PGA: a software package for rapid, accurate, and flexible batch annotation of plastomes. Plant Methods. 2019;15:12. doi: 10.1186/s13007-019-0435-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Njuguna AW, Li Z-Z, Saina JK, Munywoki JM, Gichira AW, Gituru RW, Wang Q-F, Chen J-M. Comparative analyses of the complete chloroplast genomes of nymphoides and menyanthes species (menyanthaceae) Aquat Bot. 2019;156:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2019.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, Xia R. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13(8):1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, Sánchez-Gracia A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34(12):3299–3302. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xie DF, Yu Y, Deng YQ, Li J, Liu HY, Zhou SD, He XJ. Comparative analysis of the chloroplast genomes of the Chinese endemic genus Urophysa and their contribution to chloroplast phylogeny and adaptive evolution. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(7):1847. doi: 10.3390/ijms19071847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y-b, Yuan Y, Pang Y-x, Yu F-l, Yuan C, Wang D, Hu X Phylogenetic reconstruction and divergence time estimation of Blumea DC. (Asteraceae: Inuleae) in China based on nrDNA ITS and cpDNA trnL-F sequences. Plants. 2019;8(7):210. doi: 10.3390/plants8070210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swofford D. PAUP*; Version 4. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(8):754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9(8):772–772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;32(1):268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Z, Gu C, Tembrock LR, Zhang D, Ge S. Characterization of the whole chloroplast genome of Chikusichloa mutica and its comparison with other rice tribe (Oryzeae) species. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0177553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dong M, Zhou XM, Ku WZ, Xu ZG. Detecting useful genetic markers and reconstructing the phylogeny of an important medicinal resource plant, Artemisia selengensis, based on chloroplast genomics. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0211340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang Z, Nielsen R. Synonymous and nonsynonymous rate variation in nuclear genes of mammals. J Mol Evol. 1998;46(4):409–418. doi: 10.1007/PL00006320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang H, Shi C, Liu Y, Mao SY, Gao LZ. Thirteen Camelliachloroplast genome sequences determined by high-throughput sequencing: genome structure and phylogenetic relationships. Bmc Evol Biol. 2014;14:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang F, Li W, Gao CW, Zhang D, Gao LZ. Deciphering tea tree chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of Camellia sinensis var. assamica. Sci Data. 2019;6:209. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0201-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Comparative analysis of nucleotide variability (Pi) values among the Chinese cultivated type, Assam cultivated type and wild type

Additional file 2: Table S2. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and insertion/deletion (indel) information from comparisons among C. sinensis var. sinensis, C. sinensis var. sinensis cv. Longjing43 and C. sinensis var. sinensis cv. Anhua

Additional file 3: Table S3. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and insertion/deletion (indel) information from comparisons between C. sinensis var. assamica and C. sinensis var. sinensis assamica cv. Yunkang10

Additional file 4: Table S4. Nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution (Ka) and synonymous nucleotide substitution (Ks) rates, as well as the Ka/Ks ratio of homologous protein-coding genes from C. sinensis var. sinensis, C. sinensis var. sinensis cv. Longjing43 and C. sinensis var. sinensis cv. Anhua

Additional file 5: Table S5. Nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution (Ka) and synonymous nucleotide substitution (Ks) rates, as well as the Ka/Ks ratio of homologous protein-coding genes from C. sinensis var. assamica and C. sinensis var. sinensis assamica cv. Yunkang10

Additional file 6: Table S6. Positive selection sites identified among 16 genes with synonymous or nonsynonymous mutations

Additional file 7: Table S7. The best substitution models in the phylogenetic analysis of Camellia

Data Availability Statement

Raw sequences data of CSSA were submitted to National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database with accession number MH042531. Other genomic data mentioned in the article can be accessed from NCBI and the details of accession number has been provided in Table 2.