Abstract

This article discusses the paradox of exclusion/inclusion: U.S. health policy prohibits Latinos who fall under certain classifications from accessing health services and insurance yet permits them to be “human subjects” in health research. We aim to advance the discussion of health research ethics post the Tuskegee syphilis experiment in Latinos by (a) tracing the impacts of policy exclusion and the social context of anti-Latino sentiment on Latinos’ low participation rates in health research and inequitable access to treatment modalities; (b) challenging researchers to address social sources of vulnerabilities; and (c) offering recommendations on adapting a social justice ethical stance to address these challenges, which are part of the Tuskegee Study legacy.

Keywords: Tuskegee, research ethics, health care reform, social justice, Latino health

LESSONS FROM THE U.S. PUBLIC HEALTH SYPHILIS STUDY AT TUSKEGEE AND IN GUATEMALA

The story of the U.S. Public Health Service Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, also known as the Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, spurred public outrage and raised questions about race and medical ethics in 1972 (Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel, 1973). The study of untreated syphilis in poor Black male farmers in Alabama was ethically unjustified but still was executed because the racialized ideology of that period that supported the notion of a “clinical course of syphilis that was different for the two races-Black and White” (Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel, 1973, p. 12). This approach was feasible and capitalized on the vulnerability of low-income Black male farmers who were perceived by researchers as lacking the financial means and autonomy to seek out treatment for their syphilis. A study by Susan Reverby (2011) exposed the U.S. Public Health Service for deliberately infecting poor and vulnerable persons with syphilis in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948. Human subjects were unknowingly exposed to syphilis, including prison inmates who had been infected by prostitutes and who tested positive for syphilis.

These two studies illustrate past atrocities committed against African American men and Guatemalans that have led to greater federal oversight with respect to research ethics (Reverby, 2011; Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel, 1973). Yet the critical lessons related to vulnerability are deeper and more complex (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1978), and despite the changes in research ethics post the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, abuse based on vulnerability is still an issue of concern for Latinos in the United States. We argue that the policy logic of excluding certain classifications of Latino immigrants from receiving health coverage is contradictory to the ethical principles that underlie the policy of inclusion of Latinos as human subjects in health research. On one hand, provisions of federal health and social policies such as the Affordable Care Act of 2010 and the Supreme Court’s Decision of 2012 prohibit certain groups of Latino immigrants from receiving health care coverage and participating in the private insurance exchanges, while the research guidelines for inclusion of women, minorities, and other vulnerable populations allow for increased participation in clinical trials (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2010; U.S. National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 2012). This policy paradox raises a fundamental moral and ethical question–whether it is just to withhold basic health resources from certain population groups based on differences in citizenship status, placing them at a disadvantage, while encouraging them to participate in health research, including clinical trials in which the goals are benefits generally in the population but also specifically to their subpopulation. The mandated inclusion of racial/ethnic minorities in National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding was for the purpose of ensuring benefit for these groups and to address health disparities. We discuss how this paradox of inclusion/exclusion in research and health care impacts subsequent treatment modalities and the extent to which clinical studies are translated into interventions that benefit diverse Latino communities in the United States. We challenge researchers to look beyond individual levels of vulnerability and recommend addressing social sources of vulnerability if the ethical rights and benefit of Latinos are to be protected. We end by providing recommendations on adapting a social justice ethical agenda to address Latino’s low participation rates in health research, inequitable access to treatment modalities, and social vulnerabilities.

THE PARADOX OF EXCLUSION AND INCLUSION IN U.S. HEALTH POLICY

Although federal and state health policies have always prevented unauthorized immigrants (foreign-born noncitizens who are not legal residents) from participating in public benefit programs (e.g., food stamps and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families; The National Immigration Law Center, 2011), the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (which addresses Welfare Reform) and the 2010 Affordable Care Act mark a dramatic shift toward more exclusionary policies and the disinvestment of federally funded health care for legal immigrants. Prior to the enactment of welfare reform, lawful permanent residents generally were eligible for assistance in a similar manner as U.S. citizens. Now, although the provisions of health care reform increase coverage options for low- and moderate-income Latinos through an expansion in Medicaid as well as in federal subsidies that allow certain individuals to purchase coverage through new health insurance exchanges, newly arriving lawful permanent residents are barred from receiving Medicaid or participating in the Children’s Health Insurance Program for 5 years (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2000; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009).

Federally mandated restrictions on immigrants to access health care coverage have created a “chilling effect” or the voluntary withdrawal from seeking health benefits by immigrants (Fix & Passel, 1999; Viladrich, 2012). This chilling effect is fueled by rising anti-immigrant sentiment that personifies immigrants as “undeserving” of social benefits (Chavez, 2012; Fix & Laglagaron, 2002). The rise of anti-immigrant activism such as Arizona’s SB 1070, a racial profiling law in Arizona, while struck down by the Supreme Court (Arizona v. United States, 2012), has inspired a flurry of other proposed legislation aimed at imposing stricter requirements and penalties on immigrants. Localities with a long history of immigration such as Maricopa County, Arizona, and in newer destinations such as Prince William County, Virginia, are considered laboratories for new ways to crack down on immigrants (Hsu, 2008). For example, extreme measures taken by local officials in Maricopa have sparked federal civil rights investigation and have been deemed by the U.S. Attorney’s Office as discriminatory harassment, improper searches, and arrests of Hispanic people (Hsu, 2008). In Virginia, the state legislature considered two proposals (HB1798/SB1143) to ban unauthorized immigrants from accessing state and local health care and food assistance (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2006), and Prince William County took similar measures to deny public benefits to undocumented immigrants (Fair Immigration Reform Movement, 2007). As a result of these harsh measures, Latinos (legal and unauthorized) avoid seeking public health services and hesitate to enroll in critical health care and social assistance programs out of fear that they will be retaliated and discriminated against for doing so. The policy context of exclusion toward Latino immigrants shapes the societal biases and perceptions toward all Latinos and influences the ideological underpinnings of science and medicine.

Elizabeth Heitman and Alan Wells (2004) argued that unethical conduct and the abuse of human subjects in research is the result of the racialization of humans: “How researchers view differences among groups” is “indicative of their relative worth in a moral hierarchy.” For instance, a case study evaluating the impact of the 1996 Welfare Reform on access to services for immigrants in New Mexico found that the exclusionary provisions (5-year bar on legal immigrants upon entering the United States from participating in Medicaid) affected the attitudes and perceptions of frontline medical care and social welfare providers. Findings suggests that in interpreting the exclusionary provisions, health providers draw “a clear line between ‘us’ and ‘those people’ categorized as ‘aliens’” (Cacari-Stone, 2012). For instance, an immigrant rights advocate explained the social impact of the welfare reform exclusions:

What we have done politically is that we have created these tiers of human beings: Who has access to education? Who has access to work? Who has access to health care? Right. And it’s not even the documented and undocumented anymore. It’s that the undocumented have X amount of rights, the legal permanent residents have X amount of rights, the U.S. citizens have X amount of rights. And when we create those tiers of citizenship, those categories of human beings, people internalize that and people start to see undocumented immigrants differently.

(Cacari-Stone, 2012, p. 8).

This social construction of difference based on citizenship not only contributes to a tiered system of belonging but also leads to the devaluation and abuse of human beings in health research (Heitman & Wells, 2004). Such xenophobic or racist ideologies create an environment in which unconscionable acts are regarded as “normal” and abuses are justified in the name of “research.” Legal scholar, McKanders (2010) argued that

state and local anti-immigrant laws lead to the segregation, exclusion, and degradation of Latinos from American society in the same way that Jim Crow laws excluded African Americans from membership in social, political, and economic institutions within the U.S. and relegated them to second-class citizenship status.

(p. 2)

The presence of exclusionary policies coupled with anti-Latino sentiment creates a similar racialized social context that existed during the decades of research abuses during the Syphilis Study at Tuskegee and lends to further mistrust of government research.

A LEGACY OF COMMUNITY MISTRUST

Although the mistrust of health research among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States stems profoundly from the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, other documented accounts of abuses involving Latinos have created historic fear and trauma that is passed across communities. Evidence of these abuses can be found in non-peer-reviewed sources such as the National Archives, newspapers, and university research records. Among these “unpublished” accounts are three examples that provide a lens for understanding the link between social discrimination, systematic mistreatment in public health policy and practice, and the long-standing mistrust of health among Latino communities: the disinfection of Mexicans on the U.S.–Mexican border between 1890 and 1930, the administering in 1968 of placebos to Latinas in San Antonio who thought they were receiving oral contraceptives, and the provision of “experimental” measles vaccine to Latino and African American babies and children in Los Angeles in 1990 (Alliance for Human Research Protection, 2012; Burnett, 2006; Cimons, 1996).

From 1890 to 1930, immigration policies with respect to Mexicans were liberal because the United States needed the labor to stimulate the economy. As a result, the Mexican population more than doubled every 10 years (Molina, 2011). During the same period, the U.S. Public Health Service implemented a formal “medical exclusion” policy that involved a full-scale medical surveillance system. In short, Mexicans underwent “intrusive, humiliating, and harmful baths and physical examinations at the hands of the US PHS starting in 1916” (Molina, 2011, p. 1027). José Burciaga, a janitor from El Paso, described his daily strip down and customs bath by the bridge:

They would spray some stuff on you. It was white and would run down your body. How horrible! And then I remember something else about it: they would shave everyone’s head … men, women, everybody. They would bathe you again with cryolite. That was an extreme measure. The substance was very strong.

(Burnett, 2006, p. 1)

The abuse was so severe that the National Archives suggests a connection between these U.S. Customs disinfection facilities in El Paso and the Desinfektionskammern (disinfection chambers) in Nazi Germany, noting that American officials referred to the immigrant fumigation buildings as “the gas chambers” (Burnett, 2006). Initially, this practice was in response to an outbreak of typhus in central Mexico (1915) and a year later to reports of new cases in Los Angeles and in El Paso. Although the threat of the disease subsided within a few months, the practice of disinfecting continued until the 1930s (Markel & Stern, 2002). Today, the negative medicalization of “Mexicans” and the idea of the “dirty Mexican” remains a part of medical discourse.

The labeling and stigmatization of Latinas as “sexual” gained momentum from 1940 through the 1960s and came to permeate national policy discourse. For example, underpinning this national discourse was a lack of respect for women’s autonomy and the stereotyping of Latinas as “promiscuous” and as uneducated “baby makers.” According to scholar Leo Chavez (2008), this discourse is a response to the nation’s fear of Latinas as a “threat to national security.” Chavez’s research examines the social construction of immigrants and Latinos in the United States and illustrates how this type of discourse that represents people as having “dangerous,”pathological,’ and ‘abnormal’ reproductive behaviors and beliefs” has “real political and economic consequences” (pp. 71–72). His research identifies the fear of Latina fertility as one of the central motivations for Proposition 187, a controversial yet comprehensive proposal to curb immigration by denying unauthorized immigrants access to social services including prenatal care and education (Chavez, 2008).

In the 1960s, public discourse regarding Latina sexuality, fertility, and reproduction culminated in a systematic public health policy and practice aimed at controlling population growth through normative sterilization and abortion as a common birth control method among Latina women living in Puerto Rico (Ramírez de Arellano & Seipp, 1983). The outcome of these policies made women of childbearing age in Puerto Rico more than 10 times more likely to be sterilized than were women from the United States. The Puerto Rican sterilization rate of more than 35% led to questions about systematic biases that influenced the practice of sterilization (Our Bodies, Ourselves, 2011). Accounts from hospital workers on the island and in New York raise the question as to whether these minority and disadvantaged women were given complete information or offered alternatives (Rodriguez-Trias, 1998). In an ethnographic case study of the widespread sterilization in Puerto Rico, Ramírez de Arellano and Seipp (1983) provided a deeper understanding of how the complex interrelated social, religious, and political factors of a stratified society submit Latina women to “reproductive control” and deny them personal agency (Ramírez de Arellano, & Seipp 1983, 1998). In another case, a 1968 oral contraceptive study sponsored by Planned Parenthood of San Antonio and the South Central Texas and Southwest Foundation for Research and Education, 70 poverty-stricken Mexican American women had consented to participate with the understanding that they would receive a full dosage of the contraceptive. However, without informed consent, the researchers gave half of the women the oral contraceptives and the other half a placebo. When the results of this study were released a few years later, it generated a tremendous controversy among Mexican Americans (Planned Parenthood of San Antonio, 1989). Although the records of the study reside at the University of Texas San Antonio library, the details of the study have not been investigated or published in peer-reviewed journals. Thus, it is difficult to know what led the researchers to deceive a vulnerable class of women. What were they thinking? Did the researchers assume that Latinas were so accustomed to reproducing that they were indifferent as to whether they got pregnant, or did they appear to lack the autonomy to make decisions regarding their own bodies?

More recently, the use of Latino and African American children as guinea pigs for an experimental vaccine raises the question of whether the medical research community, the private health sector, and U.S. government value brown babies. In 1990, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Kaiser Pharmaceuticals of Southern California injected 1,500 six-month-old Black and Hispanic babies in Los Angeles with an “experimental” measles vaccine that had never been licensed for use in the United States (Cimons, 1996). The inquiry into the measles research was conducted after a physician connected to a public-interest vaccine safety group raised questions. In a Los Angeles Times article (Cimons, 1996)

the CDC’s chief Dr. Satcher referred to the failure to tell the parents in L.A. that the EZ vaccine was experimental as a “little mistake” and not a deliberate attempt to deceive them. Kaiser Pharmaceuticals maintains that the failure to inform the parents was an administrative “oversight.” However, CDC grant announcements in 1989 clearly state that the vaccine trials are experimental, developmental, test and research work

(para. 2–4).

The study was halted in 1991 because similar clinical trials conducted in Africa and Haiti with the vaccine had raised questions about its relationship to an increased death rate among female infants who received the more potent of two dosages being studied (Cimons, 1996).

The U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, the Guatemala study, and these three cases provide a useful framework for examining the ethical issues that arise from exclusion and inclusion and the legacy of distrust of government and health research. Past atrocities require contemporary reflection on the application of the Belmont Report principles (beneficence, respect, and justice) in relation to the lack of access to effective treatment modalities and the persistence of social sources of vulnerability among Latino communities (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1978). In a society where rights are denied people based on race, citizenship, or language or where certain people are considered “subhuman,” the researcher has an obligation to evaluate and question the ethics of his or her own work and expand the potential harms or benefits of “science” on individuals to communities.

POLICY HARMS WITHOUT HEALTH BENEFITS: DISPARATE TREATMENT MODALITIES AMONG LATINOS

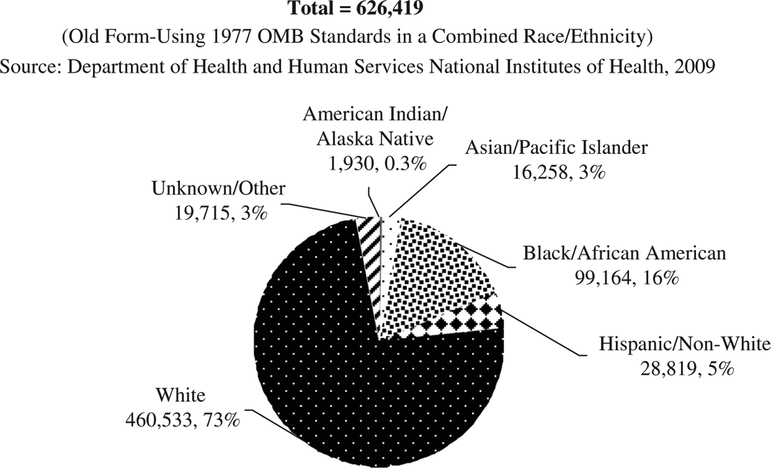

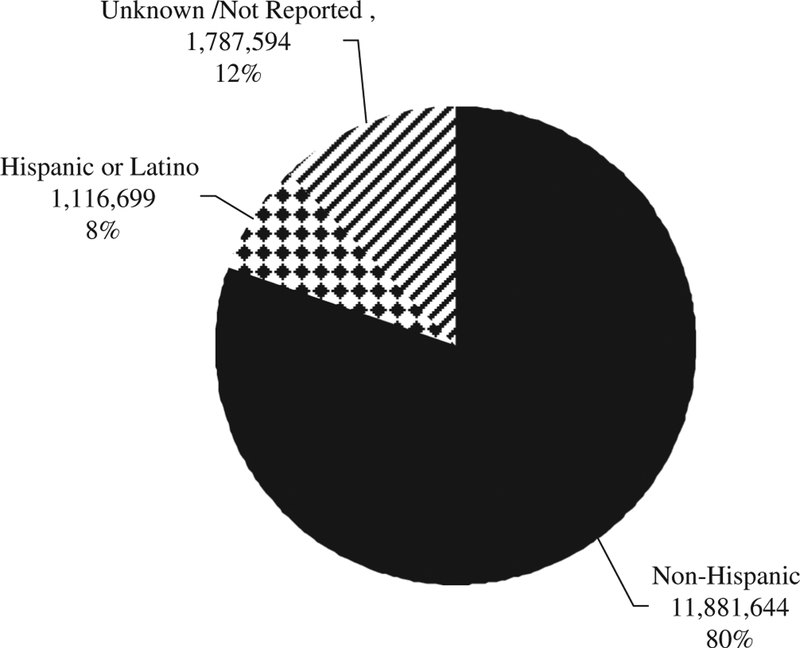

The social harms of policy exclusions (withholding of coverage and benefits from some members of society) and anti-immigrant sentiment are systematic and structural forces that undermine the potential benefits of research inclusion policies. Within a social context of exclusion, the impact of governmental policies aimed at including minority participation in research is minimal and results in limited effective treatment modalities for diverse Latino populations. The mistrust and fear of “research” across Latino communities undermine the scope and translation of culturally congruent treatment modalities. Despite the 1993 National Institutes of Health guidelines (National Institutes of Health, 2000) mandating the inclusion of women and racial and ethnic minorities in federally funded studies, the rate of participation in health studies by people of color has not reached racial equivalence (Beech & Goodman, 2004). Historically, the participation of Latinos and other racial and ethnic minorities in health studies has been disproportionately low relative to members of the majority population. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the low participation rates of Latinos compared to non-Latino Whites and other racial groups. In 2007, Latinos represented only 5% to 8% of total study enrollment for NIH-funded research; White non-Hispanics, by contrast, represented 73% (Center for Health Equity, 2009).

FIGURE 1.

National Institutes of Health enrollment for race/ethnicity 2007.

FIGURE 2.

National Institutes of Health, Hispanic enrollment 2007.

Low participation rates of Latinos in clinical studies have been attributed to various causes, including community mistrust of research and government health programs and prejudice and racism on the part of health providers and researchers. For instance, research examining barriers to recruitment and participation highlights several other interrelated factors that contribute to minimal Latino participation in health studies, including past atrocities in medical experimentation, cultural differences in health beliefs and practices, an imbalance of power, communication challenges, and issues related to health system organization (Beech & Goodman, 2004). Often, research institutions fail to implement innovative outreach and advertising efforts about clinical trials to members of racial and ethnic minority groups, which result in the underrepresentation of these groups in medical research (Brown & Moyer, 2010).

The unintended consequence of inadequate participation of Latinos in research and clinical trials can be attributed in part to unequal access to effective treatment modalities as well as treatment that is not inclusive of the specific needs of Latinos in this era of more personalized medicine. The benefit of clinical trials involving human subjects comes with the translation, dissemination, and implementation of those findings into effective medical treatment modalities for patients suffering from diseases and the myriad of conditions that result from any one set of circumstances and diagnosis. Although recent efforts have been made to recruit human subjects to participate in clinical trials, too often only a small number of “participants” are from Latino populations. As a result, most Latinos do not benefit from the translation of research findings into effective medical treatment modalities. Further exclusion of Latinos from comprehensive or quality medical treatment plans is often attributed to structural factors in the health system such as lack of linguistically appropriate care, inadequate provider training and experience in culturally competent care, and provider bias (Carrillo, Trevino, Betancourt, & Coustasse, 2001; Cooper-Patrick, 2002; Ku & Waidman, 2003; Perez, Sribney, & Rodríguez, 2009; Saha, Komaromy, Koepsell, & Bindman, 1999; Sorkin, Ngo-Metzger, & De Alba, 2010). These consequences result not only from a lack of structural inclusion of Latinos into health research and health systems but also from monoethnic approaches to studying disease etiology and the “one size fits all” approach to clinical treatments.

Latinos are a diverse population with a wide range of ethnic, migration, language, and sociocultural experiences. For example, people of Mexican origin comprise 67% of the Latino population in the Unites States, Central and South Americans 14%, Puerto Ricans 9%, and Cubans 4%, and among them 40% are foreign born (Pew Hispanic Center, 2011). Although Latinos are a heterogeneous population, the medical research community has failed to consider subpopulation differences in the etiology and treatment of diseases. Studies have demonstrated the lack of understanding of disease susceptibility and treatment modalities for diverse racial and ethnic minorities across diseases such as diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and HIV (Ayanian, Zaslavsky, Weissman, Schneider, & Ginsburg, 2003; Castellanos, Normand, Ayanian & Epstein, 2009; Elmore et al., 2005; Russell et al., 2010; Sequiest et al., 2010; Sequist et al., 2008). Using HIV infection as a case example, Mays et al. (2001) emphasized that “failure to consider these differences while attempting to develop new methods of treatment, or possibly even a cure, could have significant public health implications, for African Americans, Latinos and other minorities” (p. 802).

Investigators also argue that the structural biases of health research are the result of a poor trust relationship between medical practitioners and researchers and racial and ethnic communities (Goodwin & Richardson, 2009). Medicine has never been an entirely value-free discipline, and unless measures are taken to address structural racism and establish a new sense of trust between the medical professions and racial and ethnic minorities, these injustices will continue to deepen and expand, and more lives will be placed in jeopardy, as Clark (2009) noted in “Prejudice and the Medical Profession: A Five-Year Update.” “Medicine,” Clark stated, “has inevitably reflected and reinforced the beliefs, values and power dynamics of the society at large” (p. 120). Medicine as such has been influenced by race and racism directly and in subtle ways (Gamble, 1993). Underrepresentation of minorities in medical research leads to a body of evidence that does not account for a host of factors (e.g., genetic, cultural, racial, linguistic, gender) affecting health and effective treatment modalities for diverse populations (Mertz & Finocchio, 2008).

In addition to the lack of trust between providers and researchers and Latino communities, there is a gap between evidence-based medicine and “community-based” knowledge also defined as local cultural knowledge and practices of a particular network of lay practitioners, healers, and other promoters of health. Although these practices are innovative and produce positive outcomes and benefits for the community, they have not been sufficiently recognized by medical researchers. The medical scientific discourse that defines best practice in clinical trials and other evidence-based research omits the inclusion of community-based knowledge, mostly because it is outside their research purview. This unilateral discourse ignores the research needs of Latinos and their communities (Quesada, Hart, & Bourgois, 2011). As a result, health researchers who understand the value of bridging evidence-based medicine with community-defined evidence are seeking new ways to engage with racial ethnic communities, ways that promote trust and foster bidirectional benefits for both Latino communities and biomedical researchers.

MOVING BEYOND INDIVIDUAL RISKS TO COMMUNITY VULNERABILITIES: A MORAL IMPERATIVE

The social context of exclusion and discrimination and disparate treatment modalities require researchers to devise a new approach to conducting research with diverse Latino populations. The fundamental ethical question is to what extent researchers have a moral imperative to look beyond the individual protection of vulnerable human subjects and to address the social conditions leading to poor health, given that social and economic conditions play a fundamental role in determining health (Woolf & Braveman, 2011). As Latino researchers ourselves, we posit a research challenge, namely, to move beyond the “business-as-usual” research modality that neglects or minimizes the social conditions in which the research is being conducted and adopt an action-oriented approach to working with communities for advancing social equity.

Although we recognize that our experience may not be representative of all Latino populations, we have learned many lessons in the course of conducting our own research, which includes two community-based research projects funded by the National Institutes of Health: South Valley Partners for Environmental Justice Research and CORAZÓN por LA VIDA (Heart for Life). In both instances, we needed to modify our research approach to address the difficult social conditions that impact the daily lives of our study participants.

South Valley Partners for Environmental Justice research (NIEHS, NIH 5 R25 ES014347–04, 2005–10) is focused on developing an inclusive, participatory process for land-use decision making that facilitates the integration of public health principles and community participation in smart-growth urban development and policy making and the creation of a communication model to enable community policy engagement. The study took place in a community with the highest concentration of industrial pollution in the Albuquerque metropolitan area, a community in which 75% of the population is of Mexican descent. There are 33 Environmental Protection Agency– regulated facilities located in this southwest sector of the city, the majority of which are situated in low-income and minority neighborhoods. During this ongoing research with these communities we realized that we needed to respond to and address pressing power inequities and social sources of vulnerabilities and the voiced needs of the community members. So we invested in the training of community health workers, or promotoras de salud, who were already trusted leaders in their communities. This training provided the promotoras with environmental health and policy information and with media advocacy skills and technical research tools for gathering local data (e.g., informational technology, geomapping).

CORAZÓN por LA VIDA (Heart for Life) is a community-based primary care intervention for reducing risks of cardiovascular disease among Latinos living in the New Mexico–Mexico border region (NIMHHS, NIH 3P20MD004996-01S1). The intervention builds on both science-and community-defined evidence by combining clinical standards of care and an evidence-based 9-week health education curriculum led by promotoras de salud and by providing patient navigation and family/community support to Latinos living with hypertension in two border counties. In the process of conducting focus groups for program evaluation, the research team found that the participants’ ability to protect their health is severely constrained by many social factors. Many are a 2-hr drive from healthy, affordable food, and some live without electricity or hot water. Even though they live in an area experiencing one of the worst shortages of health professionals and that has high uninsurance rates, access to care is secondary to ongoing under- and unemployment caused by the instability of the mining industries. Acknowledging that real-life challenges were significant factors placing participants at high risk for hypertension and undermining their ability to manage their chronic disease, the research team worked with the health council and other community partners to implement a community engagement tool for assessing upstream socio-determinants of health, including factors such as equitable job and educational opportunities and the availability of parks and healthy food. The local health consortium (providers, services agencies, law enforcement, schools, religious leaders) incorporated these findings into existing countywide strategic planning and primary care delivery.

Both of these communities require dedication and work beyond the scope of a funded study and called on our commitment and expertise to recognize the social vulnerabilities that the study participants and their communities experience as an integral aspect to developing health interventions that would be valued by them. Other scholars have similarly grappled with how to incorporate a critical social action lens into their research agenda that goes beyond the institutional aims of gathering data for the purpose of expanding the scientific corpus of knowledge. For instance, Baumann, Rodriguez, and Parra-Cardona (2011) argued that it is necessary to address contextual challenges and advocate for better conditions for participants in order to implement a social-justice approach to research. In fact, researchers should question how “business-as-usual” research contributes to structural inequities and seek input from communities they are doing research with so as to develop mutually beneficial approaches to research that extend the basic principles of respect, autonomy, and benefice from the individual to the entire community. To what extent are “individual protections” in research guaranteed if Latino people are struggling for basic human rights, including access to health care, respect, and dignity in a hierarchical racial order of belonging and for other economic resources necessary to fully participate in society as autonomous beings? The disenfranchised position of subgroups of Latinos undermines the principle of collective respect and human dignity for all. The principle surrounding respect and the protection of human subjects is deeply flawed if the right of individuals and communities to act autonomously and freely regarding their own health and well-being is socially constrained. Critical action research works in partnership with communities and seeks to uphold the right of individuals and communities to freely determine the most effective medical and health-based interventions. It recognizes that communities possess the expertise to build on the most strategic aspects of their infrastructure and cultural base and achieve effective and sustainable health and social outcomes. Autonomy is fundamental to a just society, as it fosters equitable life opportunities and access to social benefits (e.g., political, economic, educational) that are necessary for attaining health and well-being (Powers & Faden, 2006). These structural risks require health researchers to rethink the terms and conditions of research and consider opportunities for gaining trust, promoting human dignity, minimizing collective vulnerabilities, and creating meaningful social benefits for Latino populations.

CREATING A NEW LEGACY: HEALTH RESEARCH ETHICS AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

We posit in this article that ethical standards and government oversight may be ineffective in preventing reprehensible behaviors if researchers and policymakers fail to address the social conditions that create health inequities or do not confront racial discrimination and the devaluation of human beings. Addressing these issues among health researchers is particularly urgent since racial and ethnic minorities accounted for 91.7% of the nation’s growth over the first decade of the 21st century (Taylor, Hugo-Lopez, Velasco, & Motel, 2011). Part of this “browning of America” or of America becoming a country that is majority–minority (Blackwell, Kwoh, & Pastor, 2011) owes to fast growth of the Latino population, which comprises 16.3% of the total population, about 50.5 million, a growth of 43% over the last decade (Passel, Cohn, & Hugo-Lopez, 2011). To accommodate these demographic changes we need to make substantive changes not just in our political system but in the fabric of our government-funded and private-sector institutions such as education, banking, and health industries. Inequitable distribution of resources must be reinvested in programs to improve everyone’s standard of living and well-being. Creating a new legacy calls for collective attention and dedicated action on part of the health research and medical community.

To effectively promote population health, researchers must step out of their comfort zone of a protected and privileged class within the academy and in turn evolve into researchers that are willing to act on and address the vulnerable cross-fires of social change. It is time to move beyond a formal apology and take action. It is this action that will serve as the catalyst to medical and health services reform and spark the critical dialogue that creates societal change by demanding accountability. Medical and public health researchers have the opportunity to stop the kind of abuse carried out in the Tuskegee Study, syphilis experiments in Guatemala, and the three previously noted cases of medical experiments involving Latino communities that continue to this day. Gaining trust and promoting human respect requires researchers to take an active role in changing the social norms of discrimination and exclusion, to address the social sources of vulnerabilities among Latinos, and to protect not just individuals but communities. Because medical abuse and exploitation remain a contemporary reality for Latinos, incorporating social justice principles into health research is a moral imperative. This moral imperative requires that we rethink our health research ethics. Drawing from a social justice approach, we outline strategies at the interpersonal, community, and structural policy levels.

Interpersonal

Overcoming trust-related barriers between researchers and Latino communities is a challenge given the legacy of mistrust from Tuskegee and other Latino-specific abuses. However, studies on the effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants have offered several tactics: minimize the “outsider–insider” gap by increasing the cultural and racial concordance between investigators and the community (Yancey, Ortega, & Kumanyika, 2006); start with the use of small pilots to help establish relationships based on mutual respect and trust (Brugge & Kole, 2003); offer communities more intensive support and contact even before recruitment and go beyond the scope of the study through the use of promotores de salud or lay outreach and health workers (Yancey et al., 2006); help individual researchers, community partners, and participants interpret research findings and help them learn how to use those findings to further benefit the community.

Community

Community-engaged strategies are imperative for developing long-lasting and sustainable research partnerships with Latinos and in reducing their disparate outcomes and preventing any inherent policy harms. For instance, the emergence and recognition of community-engaged research raises ethnical considerations that go beyond individual-level protections to include those at the community level. Community-based processes for research ethics review are being developed to reduce risks, maximize benefits, and extend the consent process to the community as a whole. In a survey of U.S.-based community-institutional partnerships, Shore et al. (2011) found that the primary benefits of “community ethics review processes” is that it gives communities of color a voice in determining the research agenda and ensuring that studies are relevant and feasible and enables the sharing power of and resources among partners involved in the research. A community-engaged review strategy changes the terms and conditions of conducting research with communities and the benefits are more likely to be mutually advantageous at many levels.

Institutional/Policy

Universities, other research institutions, and partners can play a key role in earning the public trust of racial and ethnic minorities by listening to community concerns, developing an open dialogue around the real fears and mistrust of clinical research, and improving communication between researchers and subject communities as well as recruitment efforts. For instance, from 2008 to 2009, the Eliminating Disparities in Clinical Trials Project, a collaboration between the Intercultural Cancer Council and Baylor College of Medicine (2008–2009) conducted regional meetings in more than eight communities that addressed many concerns communities have concerning clinical research trials (Intercultural Cancer Council & and Baylor College of Medicine, 2009). The EDICT project developed a one-page checklist for reviewers that grew out of its determination that the inclusion/exclusion of communities and persons from clinical trials is a function of both recruitment and retention of communities of color into research. EDICT’s work and that of the Enhancing Minority Participation in Clinical Trials Study, a collaboration of five institutions (the University of Minnesota; the University of Alabama; Johns Hopkins; MD Anderson; and the University of California, Davis) to develop, implement, and evaluate programs to promote participation in research studies across sites and minority populations have initiated critical dialogue with Latino and other racial/ethnic communities (Center for Health Equity, 2009). This critical dialogue with minority communities has resulted in major advancements toward meeting the challenges discussed in this article. Although projects such as those identified have laid the necessary groundwork for more successful engagement, a continued constellation of efforts involving transparent partnerships is needed to eliminate policies that harm and accrue no benefits. More effective and successful engagement includes capacity building with Latino communities, whose trust and participation in clinical trials is necessary to producing high-quality scientific evidence that results in better health and medical interventions.

Finally, researchers should actively promote positive public discourse regarding Latinos (both immigrants and U.S. born) and generate “research agendas” that ameliorate social vulnerabilities and promote social equity. A social justice–driven approach that is rooted in participatory research ethics guided by scientific integrity and grounded in the moral imperative should look beyond the “protection of vulnerable Latinos” to addressing the inequities leading to social vulnerabilities. Clinical research should incorporate the upstream factors causing ill health and develop interventions that can be tested in real-life settings and take community-based knowledge and expertise into account. In these ways, researchers can develop long and sustainable partnerships with minority communities.

We hope that these strategies will help researchers to initiate trust, strengthen human dignity, and ensure mutual benefits for both the researcher and Latino communities. These strategies require researchers to hold themselves accountable and to reframe their role, transforming themselves from researchers who reside in the ivory tower to researchers who work alongside communities. A research legacy like the Tuskegee Study is unforgettable and obligates researchers to work with communities to prevent disease and illness and improve health. The history of suffering that is medically well documented and that continues requires the best of our intellectual, collaborative, medical, and health research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Robert O. Valdez, Dr. Nina Wallerstein, and Lauro Silva, JD, for their reviews and comments. Also, we appreciate the research assistance of Lance C. Brown and the support of the Robert Wood Johnson Center for Health Policy at the University of New Mexico. We are grateful for the dedicated leadership of Dr. Vickie Mays for this special issue.

Contributor Information

Lisa Cacari-Stone, Department of Family & Community Medicine Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy U.S.-Mexico Border Center of Excellence Consortium University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center.

Magdalena Avila, Health Education Program University of New Mexico.

REFERENCES

- Alliance for Human Research Protection. (2012). Human experiments: A chronology of human research. Washington, DC: V.H. Sharav. Retrieved from http://www.ahrp.org/history/chronology.php [Google Scholar]

- Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S (2012).

- Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, & Ginsburg JA (2003). Undiagnosed hypertension and hypercholesterolemia among uninsured and insured adults in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). American Journal of Public Health, 93, 2051–2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann A, Rodriguez M, & Parra-Cardona J (2011). Community-based applied research with Latino immigrant families: Informing practice and research according to ethical and social justice principles. Family Process, 50, 132–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech BM, & Goodman M (2004). Race and research: Perspectives on minority participation in health studies.Washington, DC: American Public Health Association. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell AG, Kwoh S, & Pastor M (2010). Uncommon common ground: Race and America’s future. New York, NY: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, & Moyer A (2010). Predictors of awareness of clinical trials and feelings about the use of medical information for research in a nationally representative US sample. Ethnicity & Health, 15, 223–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugge D, & Kole A (2003). A case study of community-based participatory research ethics: The healthy public housing initiative. Science and Engineering Ethics, 9, 485–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett J (2006, January 28). The bath riots: Indignity along the Mexican border. In National Public Radio Weekend edition Saturday. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId5176177 [Google Scholar]

- Cacari-Stone L (2012). Caught between policy and practice: The role of public health workers in bridging population health with immigrant restrictions on public benefits. Unpublished manuscript, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo JE, Trevino FM, Betancourt JR, & Coustasse A (2001). Latino access tohealthcare: the role of insurance, managed care, and institutional barriers. In Aguirre-Molina M, Molina CW, & Zambrana RE (Eds.), Health issues in the Latino community (pp. 55–73). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos LR, Normand SL, Ayanian JZ, & Epstein AM (2009). Racial and ethnic disparities in access to higher and lower quality cardiac surgeons for coronary artery bypass grafting. American Journal of Cardiology, 103, 1682–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Health Equity. (2009). Enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT). Minneapolis, MN: National Institutes of Health, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. [Google Scholar]

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2000, October 10). Health coverage for legal immigrant children: New census data highlight importance of restoring Medicaid and SCHIP coverage. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?faview&id1348 [Google Scholar]

- Chavez L (2008). The Latino threat: Construction immigrants, citizens, and the nation. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez L (2012). Undocumented immigrants and their use of medical services in Orange County, California. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 887–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimons M (1996, June 17). CDC says it erred in measles study. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/1996-06-17/news/mn-15871_1_measles-vaccine [Google Scholar]

- Clark PA (2009). Prejudice and the medical profession: A five-year update. Journal of Law, Medicine, & Ethics, 37, 118–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Patrick L (2002). Patient–provider communication: The effect of race and ethnicity on process and outcomes of healthcare. In Smedley B, Stith A, & Nelsen A (Eds.), Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare (pp. 552–593). Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. (2009). Monitoring Adherence to the NIH policy on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research (Biennial report of the director, NIH, FY 2007 & 2008). Washington, DC. Retrieved from the NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools: http://report.nih.gov/biennialreport/ [Google Scholar]

- Elmore JG, Nakano CY, Linden HM, Reisch LM, Ayanian JZ, & Larson EB (2005). Racial inequities in the timing of breast cancer detection, diagnosis, and initiation of treatment. Medical Care, 43, 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair Immigration Reform Movement. (2007). Database of recent local ordinances on immigration. Retrieved from http://standing-firm.com/share/

- Fix M, & Laglagaron L (2002). Social rights and citizenship: An international comparison. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Fix M, & Passel JS (1999). Trends in noncitizens’ use of public benefits following welfare reform: 1994–97 (Report). Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Frammolino R (1997, November 2). Harvest of corneas at morgue questioned. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/1997/nov/02/news/mn-49420 [Google Scholar]

- Gamble V (1993). A legacy of distrust: African Americans and medical research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 9(6 Suppl.), 35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin M, & Richardson LS (2009). Patient negligence (Law School Legal Studies Research Paper Series No. 10–53). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Heitman E, & Wells AL (2004). Ethical issues and unethical conduct: Race, racism and the abuse of human subjects in research. In Beech BM & Goodman M (Eds.), Race and research: Perspectives on minority participation in health studies (pp. 35–60). Washington, DC: American Public Health Association. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera GA, Zhao Z, & Klevens RM (2001). Variation in vaccination coverage among children of Hispanic ancestry. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 20(4S), 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SS (2008, July 17). Ariz. sheriff accused of racial profiling. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Intercultural Cancer Council & Baylor College of Medicine. (2009). Eliminating disparities in clinical trials (EDICT) project: Eliminating disparities in clinical trials executive summary report from eight community dialogue meetings. Houston, TX: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2009). Focus on health reform: Immigrants’ health coverage and health reform. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/7982.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ku L, & Waidman T (2003). How race/ethnicity, immigration status and language affect health insurance coverage, access to health care and quality of care among the low-income population. Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. [Google Scholar]

- Markel H, & Stern AM (2002). The foreignness of germs: The persistent association of immigrants and disease in American society. The Milbank Quarterly, 80, 757–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, So BT, Cochran SD, Detels R, Benjamin R, Allen EM, & Kwon S (2001). HIV disease in ethnic minorities: Implications of racial/ethnic differences in disease susceptibility and drug dosage response for HIV infection and treatment. In Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, Baum A, Revenson TA, & Singer JE (Eds.), Handbook of health psychology (pp. 801–816). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- McKanders KM (2010). Sustaining tiered personhood: Jim Crow and anti-immigrant laws (University of Tennessee Legal Studies Research Paper No. 111). Knoxville: University of Tennessee School of Law. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract1648810 [Google Scholar]

- Mertz EA, & Finocchio L (2010). Improving oral healthcare delivery systems through workforce innovations: An introduction. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 70(s1), s1–s5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina N (2011). Borders, laborers, and racialized medicalization. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 1024–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. (1978, September). The Belmont Report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research (Publication No. OS 78–0012). Washington, DC. Retrieved from NIH Center for Information Technology: http://videocast.nih.gov/pdf/ohrp_belmont_report.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Conference of State Legislatures. (2006). Overview of state legislation related to immigrants introduced Jan-Feb 2006 (p. 3). Washington, DC: National Center on State Legislation. [Google Scholar]

- The National Immigration Law Center. (2011, October). Overview of immigrant eligibility for federal programs. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.nilc.org/overview-immeligfedprograms.html [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. (2000, August 2). NIH guidelines mandating the inclusion of women and racial and ethnic minorities in federally funded studies. Bethesda, MD: Author. Retrieved from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-00-048.html [Google Scholar]

- Our Bodies, Ourselves. (2011). Birth control: Other recommended resources. Retrieved from http://www.ourbodiesourselves.org/book/resources.asp?id=18

- Passel J, Cohn DV, & Hugo Lopez M (2011, March 24). Hispanics account for more than half of nation’s growth in past decade. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2011/03/24/hispanics-account-for-more-than-half-of-nations-growth-in-past-decade/

- Perez D, Sribney WM, & Rodríguez MA (2009). Perceived discrimination and self reportedquality of care among Latinos in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine 24(Suppl. 3), 548–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, P.L. 104–193, 110 Stat. 2105, August 22, 1996.

- Pew Hispanic Center. (2011, March 24). Hispanics account for more than half of nation’s growth in past decade. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2011/03/24/hispanics-account-for-more-than-half-of-nations-growth-in-past-decade/ [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act §, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 (2010).

- Planned Parenthood of San Antonio. (1989, May 2). Fiftieth anniversary luncheon pamphlet. Retrieved from http://www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utsa/00024/utsa-00024.html

- Powers M, & Faden RR (2006). Social justice: The moral foundations of public health and health policy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada J, Hart LK, & Bourgois P (2011). Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Medical Anthropology, 30, 339–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez de Arellano AB, & Seipp C (1983). Colonialism, Catholicism, and contraception: A history of birth control in Puerto Rico. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reverby S (2011). “Normal exposure” and inoculation syphilis: A PHS “Tuskegee” doctor in Guatemala, 1946–1948. The Journal of Policy History, 23(1), 6–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Trias H (1998). Sterilization and sterilization abuse. In Mankiller W, Mink G, Navarro M, Smith B, & Steinem G (Eds.), Reader’s companion to U.S. women’s history (pp. 572–573). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Russell BE, Gurrola E, Ndumele CD, Landon BE, O’Malley AJ, Keegan T, … Hicks LS (2010). Perspectives of non-Hispanic Black and Latinos patients in Boston’s urban community health centers on their experiences with diabetes and hypertension. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 152, 40–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, & Bindman AB (1999). Patient–physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Archives of Internal Medicine 159, 997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequist TD, Fitzmaurice GM, Marshall R, Shaykevich S, Marston A, Safran DG, & Ayanian JZ (2010). Cultural Competency training and performance reports to improve diabetes care for Black patients: A cluster randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 152, 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequist TD, Fitzmaurice GM, Marshall R, Shaykevich S, Safran DG, & Ayanian JZ (2008). Physician performance and racial disparities in diabetes mellitus care. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168, 1145–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore N, Brazauskas R, Drew E, Wong KA, Moy L, Baden AC, … Seifer SD (2011). Understanding community-based processes for research ethics review: A national study. American Journal of Public Health, 101(Suppl. 1), S359–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin DH, Ngo-Metzger Q, & De Alba I (2010). Racial/ethnic discrimination in health care: impact on perceived quality of care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 25, 390–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P, Hugo Lopez M, Velasco G, & Motel S (2012, January 26). Hispanics say they have the worst of a bad economy. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2012/01/26/hispanics-say-they-have-the-worst-of-a-bad-economy/

- Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel. (1973). Final report. Washington, DC: U.S. Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- United States National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567, U.S (2012).

- Viladrich A (2012). Beyond welfare reform: Reframing undocumented immigrants’ entitlement to health care in the United States, a critical review. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman M, Bender D, Lee S, Morrissey J, Mouw T, & Norton E (2006). Social support among latina immigrant women: Bridge persons as mediators of cervical cancer. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 8, 67–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf S, & Braveman P (2011). Where health disparities begin: The role of social and economic determinants: And why current policies may make matters worse. Health Affairs, 30, 1852–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey A, Ortega A, & Kumanyika S (2006). Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annual Review of Public Health, 27, 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]