Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To estimate the proportion of accidental drug-related deaths and suicides classified as pregnancy-related from 2013 to 2014 (preimplementation of standardized criteria) and 2015 to 2016 (postimplementation).

METHODS:

Based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pregnancy-related death criteria, the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee developed a standardized evaluation tool to assess accidental drug-related death and suicide beginning in 2015. We performed a retrospective case review of all pregnancy-associated deaths (those occurring during pregnancy or 1 year postpartum for any reason) and pregnancy-related deaths (those directly attributable to the pregnancy or postpartum events) evaluated by Utah’s Perinatal Mortality Review Committee from 2013 to 2016. We compared the proportion of accidental drug-related deaths and suicides meeting pregnancy-related criteria preimplementation and postimplementation of a standardized criteria checklist tool using Fisher’s exact test. We assessed the change in pregnancy-related mortality ratio in Utah from 2013 to 2014 and 2015 to 2016 using test of trend.

RESULTS:

From 2013 to 2016, there were 80 pregnancy-associated deaths in Utah (2013–2014: n=40; 2015–2016: n=40), and 41 (51%) were pregnancy-related (2013–2014: n=15, 2015–2016: n=26). In 2013–2014 (preimplementation), 12 women died of drug-related deaths or suicides, and only two of these deaths were deemed pregnancy-related (17%). In 2015–2016 (postimplementation), 18 women died of drug-related deaths or suicide, and 94% (n=17/18) of these deaths met one or more of the pregnancy-related criteria on the checklist (P<.001). From 2013 to 2014 to 2015–2016, Utah’s overall pregnancy-related mortality ratio more than doubled, from 11.8 of 100,000 to 25.7 of 100,000 (P=.08).

CONCLUSION:

After application of standardized criteria, the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee determined that pregnancy itself was the inciting event leading to the majority of accidental drug-related deaths or suicides among pregnant and postpartum women. Other maternal mortality review committees may consider a standardized approach to assessing perinatal suicides and accidental drug-related deaths.

Unintentional injuries, including drug poisoning, and suicides are the leading causes of death among reproductive-aged women in the United States.1–3 From 2005 to 2014, accidental drug overdoses and suicides were the leading cause of pregnancy-associated death in Utah, defined as death of a woman during pregnancy or within 1 year of the end of pregnancy.4

Drug use and mental health conditions are increasingly recognized as significant contributors to pregnancy-associated mortality.5–9 Mounting evidence suggests that pregnancy complicated by mental health conditions or substance use may create a cascade of events leading to maternal death, suggesting that these deaths could be classified as pregnancy-related.10 However, this determination is often difficult for maternal mortality review committees, in part because of lack of details about the circumstances of a woman’s pregnancy and death and lack of a standard approach to classifying these deaths.11,12 Standardized criteria outlining circumstances relevant to accidental drug-related deaths and suicide may facilitate more objective and consistent classification of these deaths as pregnancy-related or pregnancy-associated.

The objectives of this study were to 1) assess whether implementation of standardized criteria for accidental drug-related deaths and suicides by the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee was associated with a change in the proportion of deaths deemed pregnancy-related as opposed to merely pregnancy-associated and 2) examine the association of implementation of these criteria with Utah’s pregnancy-related mortality ratio overall.

METHODS

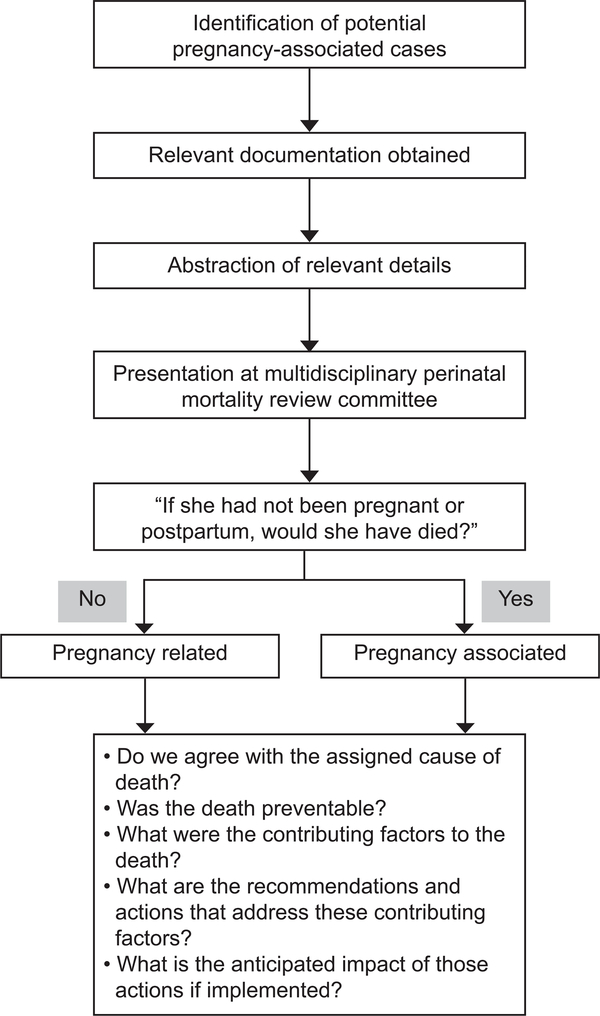

We conducted a retrospective case study of all pregnancy-associated and pregnancy-related deaths in Utah from 2013 to 2016 reviewed by the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee. The Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee is a multidisciplinary committee of obstetric and pediatric health care professionals, public health officials, medical examiners, substance use disorder and mental health experts, and epidemiologists that reviews all pregnancy-associated deaths of women residing in Utah (Fig. 1). The Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee uses the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System definitions for pregnancy-associated and pregnancy-related deaths.13,14 Pregnancy-associated deaths are those occurring during pregnancy or within 1 year of the termination of pregnancy, regardless of the cause. These deaths make up the universe of maternal mortality; within that universe are pregnancy-related deaths and pregnancy-associated, but not related, deaths.13 Pregnancy-related deaths are those occurring during pregnancy or within 1 year of the termination of pregnancy, from a pregnancy complication, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiologic effects of pregnancy.13 The Utah Department of Health identifies maternal deaths from death certificates using: 1) International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revision codes indicating that the death was related to or aggravated by pregnancy, childbirth, or puerperium; and 2) selection of a pregnancy checkbox on the death certificate, including “pregnant at time of death,” “not pregnant, but pregnant within 42 days of death,” or “not pregnant, but pregnant within 43 days to one year before death.” The pregnancy-related mortality ratio is the number of pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 live births. The Utah Department of Health reviews all potentially eligible deaths, confirms that they meet pregnancy-associated death criteria, abstracts medical records to create a de-identified case summary, and brings cases to the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee for further review. Utah law facilitates access to data sources, including medical records, mental health evaluation, death certificates, autopsy and toxicology reports, and law enforcement reports for all women with a pregnancy-associated death for epidemiologic reporting and quality improvement. Utah code grants the Utah Department of Health authority to investigate the causes of maternal mortality and authorizes facilities and health care professionals to provide data related to the condition and treatment of any person to the Department of Health.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of Utah’s Perinatal Mortality Review Committee process.

Smid. Drug-Related Death and Suicide Classification Criteria. Obstet Gynecol 2020.

Cause of death was initially determined by the certifier of the death certificate. The Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee reviews case information to deliberate if it agrees with cause of death on the death certificate. If the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee assigned an alternative cause of death, the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee cause of death was used during analysis of deaths of pregnant and postpartum women. Accidental drug-related deaths were defined as those deaths in which the underlying cause was accidental drug overdose or organ failure due to illicit, prescribed, or over-the-counter drugs, and for which there was no evidence that the death was intentional. For example, if the immediate cause of a woman’s death was myocardial infarction and cocaine was considered the underlying cause of the infarction, this death would be considered an accidental drug-related death. Suicides were defined by the medical examiner’s determination that the death was “intentional.” Intentionality was determined by the presence of evidence suggesting the person’s desire or plan to end her life either through written or verbal means (eg, suicide note, social media post, communication of active suicidal ideation or plan to another person before death). The method of suicide may have been classified as drug-related (eg, heroin overdose) or fatal injury by other means. In concordance with death certificates, early postpartum death was defined as death within 42 days from the end of the pregnancy and late postpartum death as occurring within 43 days to 1 year from the end of the pregnancy.15

Starting in 2015, the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee used the CDC’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee Decisions Form to consider each death for its pregnancy-relatedness, contributing factors and preventability.16 Data after 2015 were abstracted into the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application, a data system that allows maternal mortality review committees nationwide to abstract relevant data from a variety of sources in a standardized way to facilitate analysis of aggregated data.17 Before 2015, data were abstracted into a database housed at the Utah Department of Health. Per national maternal mortality review committees guidelines, the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee aims to answer six questions17: 1) Was the death pregnancy-related? 2) Do we agree with the assigned cause of death? 3) Was the death preventable? 4) What were the contributing factors to the death? 5) What are the recommendations and actions that address these contributing factors? 6) What is the anticipated effect of those actions if implemented?

In establishing a pregnancy-related death, the committee ultimately tries to answer the question, “If she had not been pregnant or postpartum, would she have died?” 10 To answer this question for accidental drug-related deaths and suicides, a multidisciplinary group of the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee members developed standardized criteria to determine pregnancy-relatedness over a year. These criteria were used to construct a checklist tool which provided the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee with a method by which deaths from accidental drug overdose or suicide could be accurately classified as pregnancy-related.4 During development of the tool, each of the elements of the definition of pregnancy-relatedness were addressed, and criteria were developed for each: 1) death due to a pregnancy complication, 2) death due to a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or 3) death due to the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiologic effects of pregnancy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Standardized Criteria Applied to Accidental Drug-Related Deaths and Suicides

| Standardized Criteria for Accidental Drug-Related Deaths and Suicides | Case Examples | No. of Times Identified in Accidental Drug-Related Death | No. of Times Identified in Suicide |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pregnancy complication | 7 | 1 | |

| a. Increased pain directly attributable to pregnancy or postpartum events leading to self-harm or drug use that is implicated in suicide or accidental death | Back pain, pelvic pain, kidney stones, cesarean incision, or perineal tear pain | 0 | 0 |

| b. Traumatic event in pregnancy or postpartum with a temporal relationship between the event leading to self-harm or increased drug use and subsequent death | Stillbirth, preterm delivery, diagnosis of fetal anomaly, traumatic delivery experience, relationship destabilization due to pregnancy, removal of child(ren) from custody | 7 | 1 |

| c. Pregnancy-related complication likely exacerbated by drug use leading to subsequent death | Placental abruption or preeclampsia in setting of drug use | 0 | 0 |

| 2. Chain of events initiated by pregnancy | 9 | 3 | |

| a. Cessation or attempted taper of medications for pregnancy-related concerns (neonatal or fetal risk or fear of Child Protective Service involvement) leading to maternal destabilization or drug use and subsequent death | Substance use pharmacotherapy (methadone or buprenorphine), psychiatric medications, pain medications | 3 | 1 |

| b. Inability to access inpatient or outpatient drug or mental health treatment due to pregnancy | Health care professionals uncomfortable with treating pregnant women, facilities not available that accept pregnant women | 0 | 0 |

| c. Perinatal depression, anxiety, or psychosis resulting in maternal destabilization or drug use and subsequent death | Depression diagnosed in pregnancy or postpartum resulting in suicide | 1 | 2 |

| d. Recovery or stabilization of substance use disorder achieved during pregnancy or postpartum with clear statement in records that pregnancy was motivating factor with subsequent relapse and subsequent death | Relapse leading to overdose due to decreased tolerance or polysubstance use | 5 | 0 |

| 3. Aggravation of underlying condition by pregnancy | 1 | 5 | |

| a. Worsening of underlying depression, anxiety, or other psychiatric condition in pregnancy or the postpartum period with documentation that mental illness led to drug use or self-harm and subsequent death | Pre-existing depression exacerbated in the postpartum period leading to suicide | 1 | 5 |

| b. Exacerbation, undertreatment, or delayed treatment of pre-existing condition in pregnancy or postpartum leading to use of prescribed or illicit drugs resulting in death, or suicide | Undertreatment of chronic pain leading to misuse of medications or use of illicit drugs, resulting in death | 0 | 0 |

| c. Medical conditions secondary to drug use in setting of pregnancy or postpartum that may be attributable to pregnancy-related physiology and increased risk of complications leading to death | Stroke or cardiovascular arrest due to stimulant use | 0 | 0 |

Boldface indicates totals for each category.

Initial criteria for the tool were suggested based on several years of case reviews and refined using an iterative feedback process from the entire Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee until consensus was reached on each criterion. The pregnancy-related checklist tool was then implemented as part of the process to determine pregnancy relatedness starting with deaths occurring in 2015 (Table 1). Removal of custody was grouped under pregnancy complication related to trauma from the delivery or subsequent events. To evaluate whether women with drug-related death and suicides differed before and after implementation of our checklist tool, we compared maternal characteristics, substance use, and timing of death between 2013–2014 and 2015–2016. We compared the proportion of accidental drug-related deaths or overdoses during the time period using Fisher’s exact test. We assessed the change in pregnancy-related mortality ratio in Utah from 2013 to 2014 and 2015 to 2016 using test of trend.

Preventability of all pregnancy-related deaths was determined by the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee by reviewing all available documents. A death is considered preventable if the committee determines that there was “at least some chance of the death being averted by one or more reasonable changes to patient/family, provider, facility, community and/or system of care factors.” 13 For example, a death of woman with peripartum cardiomyopathy who did not receive timely diagnostic testing and appropriate treatment would be considered preventable. Similarly, a death of a woman from an opioid overdose who was not screened appropriately or offered pharmacotherapy (methadone, buprenorphine) would be considered preventable. We reviewed the change in assessment of preventability before and after implementation. After 2015, recommendations from the committee were recorded in Maternal Mortality Review Information Application for each pregnancy-related death. Contributing factors are paired with a recommendation for action to promote prevention of these deaths. We describe the contributing factors of drug-related deaths and suicides from 2015 to 2016 when the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application data-tracking system was used.

The institutional review boards of the University of Utah and the Utah Department of Health reviewed and approved this study.

RESULTS

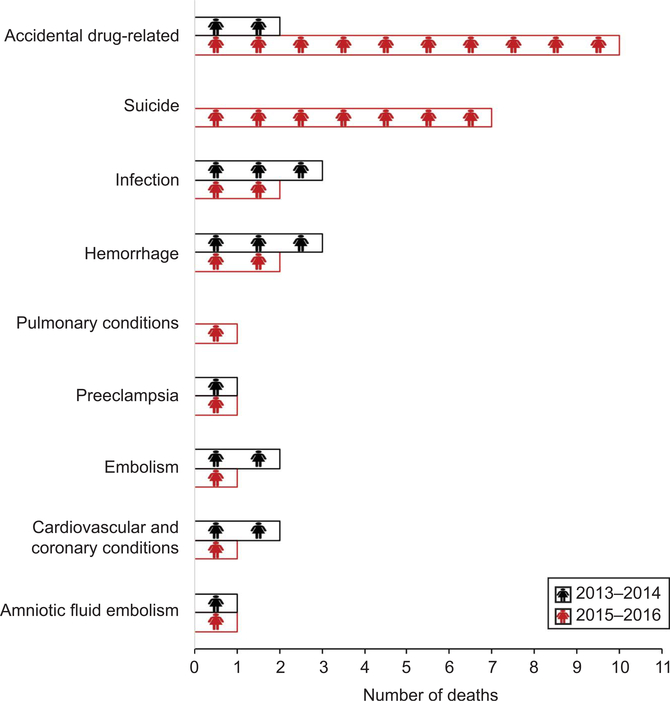

From 2013 to 2016, there were 203,339 live births, 80 pregnancy-associated deaths and 41 pregnancy-related deaths in Utah. In 2013–2014, there were 40 pregnancy-associated deaths, of which 15 were pregnancy-related deaths, compared with 40 pregnancy-associated deaths and 26 pregnancy-related deaths in 2015–2016 (Fig. 2). In 2013–2014, before implementation of the checklist, there were 12 accidental drug-related deaths and suicides, and two cases were considered pregnancy-related deaths by the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee (17%), nine cases were pregnancy-associated (75%), and in one case, the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee was unable to determine pregnancy-relatedness (8%). Because of the details available in the case, the committee was unable to determine pregnancy-relatedness and therefore, the committee deemed the case pregnancy-associated and pregnancy-relatedness unable to be determined. In 2015–2016, after implementation, there were 18 accidental drug-related deaths and suicides, and 17 (94%) cases met one or more criteria on the pregnancy-related standardized criteria. One death due to suicide was deemed pregnancy-associated, because there was evidence that the suicide was triggered by an unrelated medical condition as opposed to the pregnancy or postpartum events. The change in proportion of cases deemed pregnancy-related from before to after standardized criteria implementation was statistically significant (P<.001). Among women with accidental drug-related deaths, the most common pregnancy-related criteria that led to death were 1) pregnancy complications, most frequently destabilization after removal of custody of an infant (n=7); and 2) recovery or stabilization of substance use disorder achieved during pregnancy or postpartum with clear statement in records that pregnancy was motivating factor with subsequent relapse and subsequent death (n=5) (Table 1). Among women who died by suicide, the most common pregnancy-related criterion was aggravation of underlying mental condition (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder) during pregnancy, followed by cessation of psychiatric medications leading to destabilization. Five criteria were not relevant to any death during this time period, specifically 1a, 1c, 2b, 3b, and 3c (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Causes of pregnancy-related deaths, 2013–2014 and 2015–2016.

Smid. Drug-Related Death and Suicide Classification Criteria. Obstet Gynecol 2020.

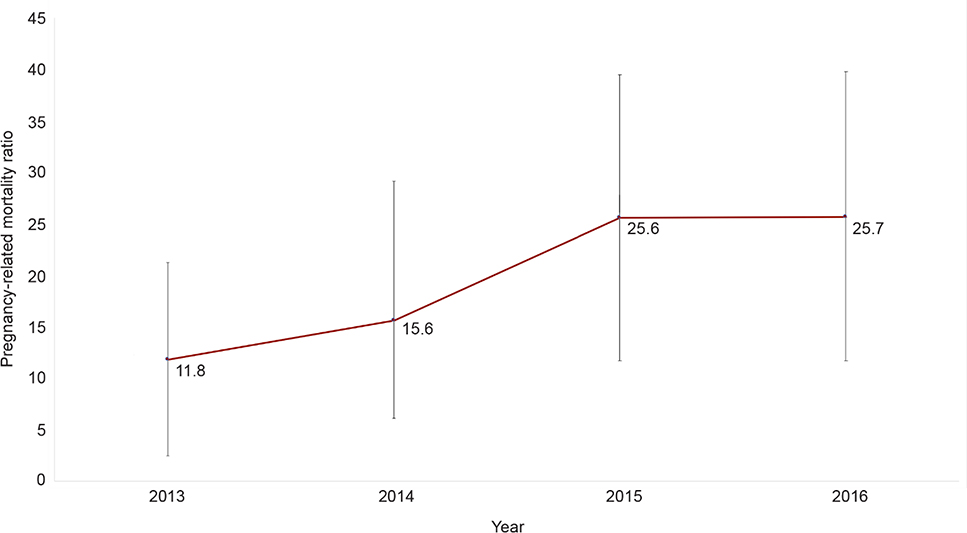

From 2013 to 2016, the pregnancy-related mortality ratio rose more than two-fold from 11.8 per 100,000 in 2013–2014 (preimplementation), to 25.7 per 100,000 live births in 2015–2016 (postimplementation). The change over time was not statistically significant (P=.08) (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/B979). There were no differences between time periods for maternal age, race–ethnicity, education, parity, Medicaid coverage at delivery, initiation of prenatal care, or number of prenatal visits in accidental drug-related deaths or suicides (Table 2). In both time periods, the majority of deaths occurred in the postpartum period. When assessing only deaths in which drugs were a factor (2013–2014: n=7; 2015:2016: n=14), the majority of deaths in both time periods were attributable to opioids (77% vs 83%) and polysubstance use (89% vs 100%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Women With Perinatal Drug-Related Deaths and Suicides

| Characteristic | 2013–2014 Deaths (n=12) | 2015–2016 Deaths (n=18) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||

| 15–19 | 0 | 1 (5.6) |

| 20–34 | 11 (91.7) | 12 (66.7) |

| 35 or older | 1 (8.3) | 5 (27.8) |

| Race–ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 10 (83.3) | 16 (88.9) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 1 (8.3) | 1 (5.6) |

| Hispanic | 1 (8.3) | 1 (5.6) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 1 (8.3) | 1 (5.6) |

| High school graduate | 5 (41.7) | 5 (27.8) |

| More than high school | 6 (50.0) | 8 (44.4) |

| Unknown | 4 (22.2) | |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 3 (25.0) | 5 (27.8) |

| 1 or more | 9 (75.0) | 12 (66.7) |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (5.6) |

| Medicaid at delivery | ||

| Prenatal care initiation (trimester) | ||

| 1st (less than 13 wk) | 7 (58.3) | 10 (55.6) |

| 2nd (13–27 wk) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (22.2) |

| 3rd (28 wk or more) | 1 (8.3) | 0 |

| Unknown | 2 (16.7) | 4 (22.2) |

| No. of prenatal visits (median, IQR) | 10.5, 5.5 | 10, 5 |

| Geographical region of death (residence) | ||

| Urban | 8 (66.7) | 13 (72.2) |

| Rural | 4 (33.3) | 5 (27.8) |

| Frontier | 0 | 0 |

| Location of death | ||

| Home | 4 (33.3) | 8 (44.4) |

| Hospital | 4 (33.3) | 4 (22.2) |

| Outpatient clinic | 0 | 1 (5.6) |

| Other | 0 | 4 (22.2) |

| Unknown | 4 (33.3) | 1 (5.6) |

| Timing of death | ||

| During pregnancy | 0 | 4 (22.0) |

| Day of delivery | 0 | 1 (5.6) |

| 1–6 d after end of pregnancy | 0 | 1 (5.6) |

| 7–42 d after end of pregnancy | 1 (8.3) | 0 |

| 43–365 d after end of pregnancy | 9 (75.0) | 12 (66.7) |

| Unknown | 2 (16.7) | 0 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

To assess geographic distribution of drug-related pregnancy-associated death, we assessed the county of death and classified the location as urban, rural or frontier. As defined by the Utah Office of Primary Care and Rural Health, urban counties are defined as those with 100 or more persons/square mile, rural counties 6–99 persons/square mile, and frontier counties fewer than six persons/square mile.27

In 2013–2014, 33% of accidental drug-related deaths and suicides (n=7/11) were considered preventable compared with 100% of these deaths in 2015–2016 (n=18/18). Using the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application data system for deaths in 2015–2016, a total of 89 contributing factors were identified for accidental drug-related deaths and suicides. Recommendations for prevention are reported by level (Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/B979). Patient- or family-level contributing factors including mental health and substance use may have resulted in recommendations at the health care professional (universal screening), systems of care (expanded mental health and substance use services), community (naloxone availability and public education on gun safety), and facility (expansion of referral networks for mental health and substance use treatment facilities) levels.

DISCUSSION

Accidental drug-related deaths and suicides are the most common identifiable cause of pregnancy-related death in Utah between 2013 and 2016. After the application of a standardized criteria checklist to review maternal deaths from accidental drug-related causes and suicide, Utah’s pregnancy-related mortality ratio rose, as more than 90% of these deaths were considered pregnancy-related. Our data suggest that a substantial majority of deaths due to suicides and accidental drug-related causes can be directly linked to pregnancy and the postpartum period and are, therefore, pregnancy-related. All of these deaths were considered preventable.

Nationwide, accidental drug overdose and suicides are increasingly recognized as a leading cause of maternal death.7,9,18–20 Maternal mortality review committees have focused on identifying areas of prevention for pregnancy-related deaths, which have typically excluded accidental drug-related deaths and suicides.21–26 We propose that a standardized checklist tool for determining pregnancy-relatedness for accidental drug-related deaths and suicides will allow for a more objective way of classifying these deaths as pregnancy-associated or pregnancy-related. The California Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review Committee has proposed pregnancy-related criteria for suicides but does not include accidental drug-related deaths.12 We suggest that our standardized criteria checklist, and those proposed by California, form the basis for a national conversation on a cohesive public health approach to assess whether certain deaths of mothers from drugs and suicide are, in fact, due to pregnancy.

The major strength of this study is the detailed information available to the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee. We are able to access a variety of sources to reconstruct the timeline leading to a woman’s death. Frequently, information gleaned from the nonmedical records, including police records, postmortem interviews with family and friends, and social media posts, provides the key that allows us to link the pregnancy and postpartum period and a woman’s death as directly related. Because many deaths occur outside of the hospital, particularly for accidental overdose and suicides, the medical chart is incomplete and limited. Our committee is also made up of a multidisciplinary group as described in the methods. At this time, patients, family members, and patient advocates are not part of the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee; however, this is under consideration.

Our study has inherent limitations. Although the change in pregnancy-related mortality ratio was not statistically significant during the two time periods, we may simply be underpowered because we have only 2 years of available data after implementation of standardized criteria for analysis. We acknowledge that these data represent one review committee reviewing deaths in one state. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that in 2019, Utah’s population was 78% White (alone, no Hispanic or Latino) and 92% of adults older than age 25 years had a high school diploma.28 Utah also has the youngest population and second highest birth rate in the country. The checklist may require further iterations to be generalizable to states with more racial, ethnic and educational diversity. In addition, the evaluation is over a relatively short period of time; more reviews may add greater robustness and nuance to the data and to the use of the checklist. For instance, some criteria in our checklist were not reflected in any maternal deaths, which could indicate these criteria need to be refined or removed. We suggest that national data should be used to create a national checklist tool to standardize the classification of deaths as pregnancy-related or pregnancy-associated. Standardization nationally of these deaths would also help to track changes in maternal deaths over time.

Our study highlights that when these deaths are classified as pregnancy-related, we are able to identify contributing factors according to CDC guidelines. Our recommendations to address the prevention of these deaths are primarily focused on improving health care professional knowledge and ability to care for women with perinatal mental health concerns and increasing the facility, community, and systems of care responsiveness to caring for this vulnerable group of women. For example, a patient or family factor commonly identified in accidental drug-related death and suicide was frequently missed appointments. In examining the cases holistically, the Utah Perinatal Mortality Review Committee recognized that women with complex mental health issues tend to have lower socioeconomic status than women who died of other causes, suggesting that it may be structural factors such as unreliable transportation and other competing economic priorities such as housing and childcare. Recommendations to address these issues focus less on identifying factors of the “noncompliant patient” and more on addressing the “noncompliant” system of care. Suggestions for systems improvements include increasing resources to aid health care professionals in care coordination, additional support to track and assist women when missed appointments do occur, and lowering economic barriers by co-locating services and increasing access to public transportation.

We found that the majority of deaths due to drug overdose and suicide were directly linked to the woman’s pregnancy and met pregnancy-related criteria. Our standardized criteria provide a framework for other maternal mortality review committees to assess a woman who died of a drug-related cause or suicide would have died had she not been pregnant. We hope that these results will aid in the national discussion of these deaths and serve as the beginning of nationally accepted pregnancy-related criteria for accidental drug-related deaths and suicides.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure

Marcela C. Smid is supported by Women’s Reproductive Health Research (WRHR K12, 1K12 HD085816) Career Development Program and serves as a medical consultant for Gilead Science Inc. Torri D. Metz reports receiving UpToDate royalties for two topics on VBAC, and money paid to her institution from Pfizer for being a site PI for an RSV vaccine trial (received institutional start up, but trial stopped prior to enrolling any patients). Funds were paid to her institution from Gestvision (site PI for preeclampsia POC test). In addition, she received funds from Novartis and GSK (site PI for GBS vaccination trial, institution received money to conduct study) and Novavax (site PI for RSV vaccination trial, institution received money to conduct study). The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Appendix 1. Change in pregnancy-related mortality ratio in Utah from 2013 to 2016.

Appendix 2. Recommendations to Prevent Maternal Deaths by Critical Factors

| Factors cited (n) | Recommendations | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient/family | Mental health (14) Substance use (13) Childhood trauma (5) Chronic disease (4) Delay in seeking care (4) unstable housing (3) Adherence to treatment plan or medications (2) social support/isolation (1) |

None – recommendations at other levels support patients and families. |

| Health care professional | Quality of care (8) |

Primary prevention • Establish standards of care for prescribers including: check controlled substance database, co-prescribe naloxone with opioids, limit number of pills prescribed Secondary prevention • Naloxone kits to women and their families for individuals with substance use disorder, risky substance use, history of overdose or chronic opioid prescriptions Perinatal mental health and addiction health care professional education • Implement use of standardized and validated prenatal and postpartum screening for both mental health and substance use • Include firearm access in mental health and substance use risk assessment • Education about risks of maternal destabilization, relapse and maternal death in setting of tapering pharmacotherapy (methadone, buprenorphine) or psychotropic medications in pregnancy or postpartum • Increase obstetrical, pediatric and emergency room health care professionals’ understanding and use of SBIRT framework including resources for mental health and drug treatment referrals, crisis team and suicide risk response • Increase health care professional awareness and skills in trauma informed care • Educate out of hospital health care professionals (i.e. direct entry midwives, birth center midwives) on mental health and substance use screening and treatment |

| Facility | Lack of standardized policy and procedures (4) |

Inpatient and outpatient obstetrical and mental health facilities • Improved coordination of case among health care professionals, access to records and follow-up for missed appointments for women with mental health and substance use concerns • Clear referral networks for mental health and substance use specialists • Facility protocols to reduce opioids prescribing after routine vaginal delivery • Improved coordination between obstetrical and pediatric health care professionals Prison/jail • Continuation of pharmacotherapy and psychiatric medication during incarceration and upon release • More frequent monitoring of isolated inmates, standardize monitoring policies across jails re: reasons for isolation, monitoring of isolated inmates, inmates on suicide watch • Improved cultural competency training regarding LGBTQ issues in jail/prison • Naloxone provision upon release |

| Community | Cultural (3) Environmental (2) Legal (1) |

• Expansion of inpatient substance use treatment in rural and frontier locations • Provide support for family victims of suicide (similar to support provided for victims of crime) • Increase use of peer support and recovery coaches • Improve availability of naloxone (like availability of automated external defibrillator) • Medical license boards address stigma regarding individuals with substance use among healthcare health care professionals • Educate public on disposal of excess medications including narcotics • Educate public on removing access to firearms from people with mental health issues |

| Systems of care | Coordination of care (11) Barriers to care (3) communication (2) Referral (1) Outreach (1) |

• Department of Child and Family Services coordinate maternal follow up for 1 year postpartum, particularly if child(ren) are removed from custody • Expand case management and care coordination for women with substance use and mental health conditions • Provide in-home services for women with mental health and substance use • increased awareness and resources for healthcare health care professionals with SUD • Extend pregnancy Medicaid coverage for one year postpartum • Fund and establish perinatal psychiatric unit • Fund and establish maternal mental health hotline |

REFERENCES

- 1.Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, Curtin SC, Arias E. Deaths: final data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2017;66:1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. annual surveillance report of drug-related risks and outcomes—United States. Surveillance special report. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2018-cdc-drug-surveillance-report.pdf. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- 3.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Arias E. Deaths: final data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2019;68:1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smid MC, Stone NM, Baksh L, Debbink MP, Einerson BD, Varner MW, et al. Pregnancy-associated death in Utah: contribution of drug-induced deaths. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133: 1131–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gold KJ, Singh V, Marcus SM, Palladino CL. Mental health, substance use and intimate partner problems among pregnant and postpartum suicide victims in the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2012;34:139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austin AE, Vladutiu CJ, Jones-Vessey KA, Norwood TS, Proescholdbell SK, Menard MK. Improved ascertainment of pregnancy-associated suicides and homicides in North Carolina. Am J Prev Med 2016;51(5 suppl 3):S234–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metz TD, Rovner P, Hoffman MC, Allshouse AA, Beckwith KM, Binswanger IA. Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose in Colorado, 2004–2012. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128: 1233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehta PK, Bachhuber MA, Hoffman R, Srinivas SK. Deaths from unintentional injury, homicide, and suicide during or within 1 year of pregnancy in Philadelphia. Am J Public Health 2016;106:2208–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gemmill A, Kiang MV, Alexander MJ. Trends in pregnancy-associated mortality involving opioids in the United States, 2007–2016. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;220:115–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Building UC capacity to review and prevent maternal deaths: report from nine maternal mortality review committees. 2018. Available at: http://reviewtoaction.org/Report_from_Nine_MMRCs. Retrieved January 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis NL, Smoots AN, Goodman DA. Pregnancy-related deaths: data from 14 U.S. maternal mortality review committees, 2008–2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The California pregnancy-associated mortality review report: pregnancy-associated suicide, 2002–2012. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Public Health, Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Division; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reviewtoaction.org. Definitions. Available at: http://www.reviewtoaction.org/learn/definitions. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- 15.Utah Vital Statistics. Death certificate. Available at: https://vitalrecords.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/Births-and-Deaths-2016-Utah-Vital-Statistics.pdf. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Foundation. Report from maternal mortality review committees: a view into their critical roles. Available at: https://www.cdcfoundation.org/sites/default/files/upload/pdf/MMRIAReport.pdf. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- 17.Zaharatos J, St Pierre A, Cornell A, Pasalic E, Goodman D. Building US capacity to review and prevent maternal deaths. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman-Mellor S, Margerison CE. Maternal drug-related death and suicide are leading causes of post-partum death in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:489.e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangla K, Hoffman MC, Trumpff C, O’Grady S, Monk C. Maternal self-harm deaths: an unrecognized and preventable outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ecker J, Abuhamad A, Hill W, Bailit J, Bateman BT, Berghella V, et al. Substance use disorders in pregnancy: clinical, ethical, and research imperatives of the opioid epidemic: a report of a joint workshop of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and American Society of Addiction Medicine. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:B5–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacob S, Bloebaum L, Varner MW. Maternal mortality in Utah. Obstet Gynecol 1998;91:187–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:366–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006–2010. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Main EK, McCain CL, Morton CH, Holtby S, Lawton ES. Pregnancy-related mortality in California: causes, characteristics, and improvement opportunities. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 125:938–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berg CJ, Chang J, Elam-Evans L, Flowers L, Herndon J, Seed KA, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance–United States, 1991–1999. MMWR Surveill Summ 2003;52:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1998 to 2005. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1302–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Utah Office of Primary Care & Rural Health. Shortage area designations. 2018. Available at: https://ruralhealth.health.utah.gov/workforce-development/primary-care-office-pco/shortage-designations/. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- 28.United States Census Bureau. Utah: quick facts. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/UT. Retrieved February 13, 2020.