Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is an aggressive disease with poor prognosis. Gemcitabine remains an effective option for the majority of PDAC patients. Unfortunately, currently no reliable prognostic and predictive biomarkers of therapeutic response are available for the patients with PDAC. Laminin γ2 (LAMC2) is overexpressed in several cancers, and its high expression facilitates cancer development and chemoresistance. However, its functional role in PDAC remains unclear, and a better understanding of this will likely help improve the prognosis of PDAC patients. This study aimed to elucidate the clinical and biological role of LAMC2 in PDAC. We first analyzed the expression levels of LAMC2 by real-time reverse transcription PCR in a cohort of 114 PDAC patients. Interestingly, higher expression of LAMC2 significantly correlated with poor survival in PDAC cohort. In addition, elevated LAMC2 expression served as a potential prognostic marker for survival. Subsequently, functional characterization for the role of LAMC2 in PDAC was performed by small interfering RNA knockdown in pancreatic cancer (PC) cell lines. Interestingly, inhibition of LAMC2 in PC cells enhanced the gemcitabine sensitivity and induction of apoptosis. Moreover, it inhibited colony formation ability, migration and invasion potential. Furthermore, LAMC2 regulated the expression of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype. In addition, LAMC2 significantly correlated with genes associated with the expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in PC cells and PDAC patients. In conclusion, these results suggest that LAMC2 regulates gemcitabine sensitivity through EMT and ABC transporters in PDAC and may be a novel therapeutic target in PDAC patients.

LAMC2 plays a significant role in pancreatic cancer cells through regulation of EMT and ABC transporters associated with cellular migration and invasion, resulting in poor prognosis and gemcitabine sensitivity in patients with pancreatic cancer.

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the most aggressive and lethal cancers, which is projected to become the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the USA by 2030 (1–3). Although the clinical outcomes from several other cancers have improved considerably in last decades, the 5-year survival rates for PDAC still remain less than 10%. In spite of the recent improvements in chemotherapeutic regimens, most patients experience relapse following surgery, which is one of the reasons for this increased morbidity and mortality (4–7). The median overall survival (OS) of patients with metastatic PDAC does not extend beyond 1 year (4,6).

Gemcitabine is a pyrimidine nucleoside analog that is commonly used in the treatment of solid cancers such as the breast, lung and pancreatic cancers (PCs). Systemic chemotherapy with gemcitabine has been the standard treatment for advanced PDAC (8). However, median survival in gemcitabine-treated PDAC patients is ~6 months (8). Consequently, other combination regimens that are gemcitabine based have been developed for improving survival; however, none of these strategies has resulted in significant improvements in the overall clinical outcomes because of the underlying intrinsic or acquired therapeutic resistance (4,9–11). The molecular mechanisms of gemcitabine resistance can be attributed to cell plasticity, tumor heterogeneity, altered metabolism, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and the regulation of drug influx and efflux (12–15).

The EMT is an important biological process that plays a seminal role in the cancer progression of metastasis. During this process, cancer cells downregulate the expression of cellular adhesion molecules and gain mesenchymal properties through acquisition of mesenchymal features (16). Several studies have now reported that EMT not only enhances the ability of tumor cells to metastasize, but also orchestrates chemoresistance (17–19). However, the precise mechanisms that govern EMT-mediated chemoresistance to gemcitabine-based treatment in PDAC remain poorly understood.

Accumulating evidence in recent years has revealed that ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are major players that contribute to chemoresistance in cancers, by virtue of their ability to increase the intracellular drug efflux and reduce the drug accumulation in cancer cells (12). However, their role in gemcitabine-based resistance in PC remains unclear. Any insights into this important, clinically relevant issue, would have a significant impact in improving therapeutic responses to gemcitabine-based therapies in cancer, including PDAC.

In the present study, we have identified a novel function for Laminin γ2 (LAMC2) in mediating PC prognosis and gemcitabine resistance via EMT, along with the upregulation of a family of ABC transporters. LAMC2 is a subunit of the heterotrimeric glycoprotein laminin-332 (LAM-332, formerly laminin-5), which consists of the α3, β3 and γ2 chains. LAM-332 is an essential component of this multimeric functional complex that regulates cell adhesion, differentiation and migration, as well as the invasion of epithelial cells in normal tissues (20,21). In addition, LAMC2 is overexpressed in various cancers (22–26). Moreover, recent studies have reported that LAMC2 is frequently overexpressed in cancer cells, particularly that have undergone EMT in different cancer types (25,27,28). In addition, the expression levels of LAMC2 are directly regulated by the EMT master regulator ZEB1 and activated β-catenin in invasive colorectal carcinoma cells (29,30). However, the role of LAMC2 in gemcitabine resistance in PDAC has not been systematically characterized. Herein, we for the first time provide evidence that high expression of LAMC2 is associated with not only poor survival but also gemcitabine resistance in PDAC patients, and that inhibition of LAMC2 in PC cells increased their sensitivity to gemcitabine, preferentially through suppression of EMT and ABC transporter signaling. We further demonstrate that LAMC2 promotes migration, invasion and inhibit apoptosis in human PC cells.

Materials and methods

Patient cohorts

In this study, we enrolled a total of 413 PDAC patients from multiple cohorts, including two public datasets [GSE71729 (n = 123) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; n = 176)] and an in-house clinical cohort (n = 114). The GSE71729 dataset was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Likewise, TCGA dataset was downloaded from the UCSC Xena Browser (https://xenabrowser.net).

In the clinical cohort, all patients underwent surgery for PC at the Saitama Cancer Center, Japan, between April 1997 and May 2013. None of the patients received preoperative cancer treatment, and all tumors were diagnosed as PDAC. Ninety-two patients were treated with the gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery. The PDAC tissues were obtained from resected specimens and were immediately frozen and stored at −80°C until use. All patients were followed until death or January 2019. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. A written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was approved by the institutional review boards of City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center and Saitama Cancer Center.

Total RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from fresh-frozen tissue specimens using the AllPrep DNA/RNA/miRNA Universal Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) was performed from 500 ng of total RNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse-Transcription Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). We performed quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR analysis (qRT–PCR) using the SensiFAST™ SYBR® Lo-ROX Kit (Bioline, London, UK) and the QuantStudio 6 Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and expression levels were evaluated using the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 6 Flex Real Time PCR System Software. The relative abundance of target transcripts was evaluated and normalized to the expression levels of β-actin as an internal control by employing the 2-ΔCt method; ΔCt means the difference of Ct values between the mRNAs of interest and the normalizer. Normalized values were further log2 transformed (31–33). The PCR primers used in the current study are described in Supplementary Table S1, available at Carcinogenesis Online.

Cell lines

The human PC cell lines, PANC-1, MIAPaCa-2, BxPC-3 and CAPAN-2 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). All cell lines were cultured in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium or Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium from the Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, and were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cells were maintained at 37°C in a humid atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All cell lines were tested and authenticated using a panel of genetic and epigenetic markers every 4–6 months.

Small interfering RNA induced inhibition of LAMC2

Specific double-stranded LAMC2 small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (Silencer Select® s534191; Ambion, Austin, TX) were transfected into PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cells (1.0 × 105) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Silencer Negative Control #1 siRNA (Ambion) was used as a negative control. Cells were incubated in culture media for 48 h after transfection prior to harvesting for analyses. All experiments were conducted in triplicates, and at least three independent experiments were performed.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed by WST-8 assay using Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo, Japan) as described previously (34). After the incubation of siRNA or negative control siRNA for 24 h, cell growth was assayed in 96-well plates after 72 h with the treatment of gemcitabine (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The absorbance at 450 nm was recorded with a 96-well plate reader (TECAN, infinite 200Pro, i-control software).

Colony formation assay

A total of 1000 cells transfected with siLAMC2 or negative control were seeded into 6-well plates and cultured for 10 days in a humidified CO2 incubator at 37°C. Cells were incubated for a total of 10 days and thereafter stained with crystal violet as described previously (35). The number of colonies with more than 50 cells was counted using the Image J program, ver. 1.51 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Cell invasion, migration and wound-healing assays

Two days following transfection with LAMC2 or negative control siRNA, invasion and migration assays were performed with a BD BioCoat Matrigel Invasion Chamber (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) that had 8 µm pore size membranes with Matrigel (for the invasion assay) or without Matrigel (for the migration assay) as described previously (36). For wound-healing assays, cell monolayers transfected with LAMC2 or control siRNA were scratched with a sterile 200 µl pipette tip, and cell migration was observed for up to 24 h. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Western blot analysis

Total cellular protein was extracted and western immunoblotting was performed as described previously (35,37). Briefly, proteins were extracted from cells using a RIPA lysis and extraction buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Total protein concentration in the lysates was determined using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking using 5% low-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature, the membranes were probed with a mouse anti-LAMC2 (E-6, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti-poly ADP-ribose polymerase-1 (PARP-1) (sc-7150, 1:300, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-caspase 3 (sc-7148, 1:300, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-E-cadherin (H-108, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-vimentin (H-84, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), goat anti-ZEB1 (C-20, 1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-ZEB2 (E-11, 1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse anti-β-actin (A5441, 1:5000, Sigma–Aldrich). Membranes were thereafter incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG (Sigma–Aldrich). All protein bands on the membranes were visualized using the ChemiDoc™ MP Imaging System and Image Lab™ Software version 5.2.1 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA). Band intensity was quantified using the Image J program and expressed as a ratio to β-actin band intensity.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Medcalc statistical software V.19.1.0 (Medcalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium). Differences between groups were estimated by the Student’s t-test, the Chi-square test, Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate. Spearman’s correlation was used to evaluate the linear relationship between two variables. Patients divided into the high or low expression group of LAMC2 were classified by Youden’s index derived cutoff thresholds. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. All P values were calculated using a two-sided test. For time-to-event analyses, survival estimates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier analysis, and the survival differences between groups were compared using the log-rank test. Associations between OS and clinicopathologic features were evaluated by univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Parameters determined to be significant by univariate analysis were included in multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Error bars denote standard deviation for the columns in the figures. All P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

High LAMC2 expression is associated with poor survival outcomes in PDAC patients

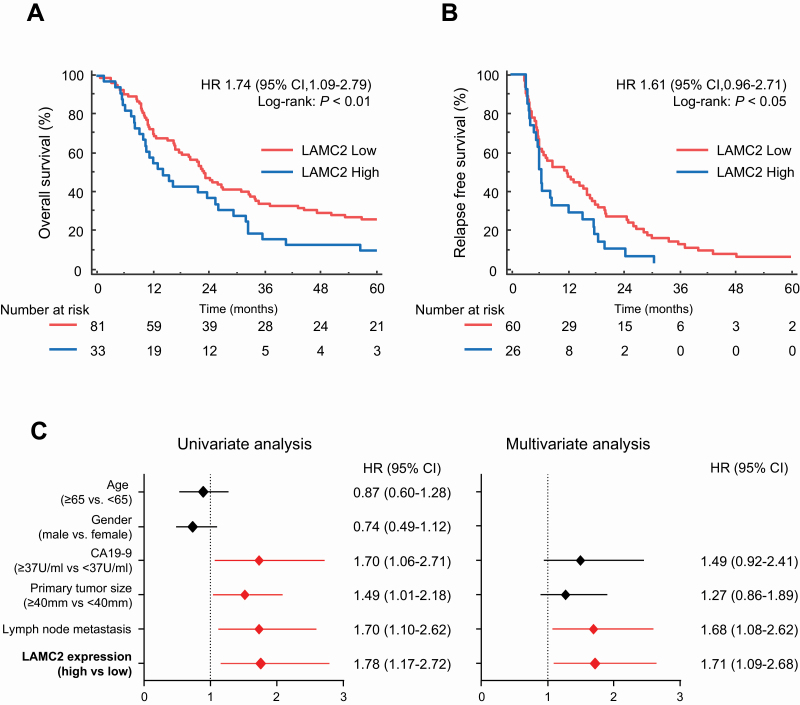

To assess the impact of LAMC2 on prognosis and survival, we initially performed the survival analysis in two public datasets (GSE71729 and TCGA). Interestingly, we observed a significant association of high LAMC2 levels with poor OS (Supplementary Figure S1A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). To determine the cutoff thresholds of LAMC2 expression for dichotomizing the high- and low-risk groups, we evaluated the LAMC2 expression by qRT–PCR in the in-house clinical cohort (Table 1). In this cohort of 114 patients, 81 patients exhibited low LAMC2 expression, and 33 had high LAMC2 expression, as determined by qRT–PCR. Next, Kaplan–Meier analysis for OS and relapse-free survival (RFS) was performed in order to evaluate the prognostic potential of LAMC2 expression. Interestingly, OS and RFS were significantly reduced in the group with high LAMC2 expression [OS: 23.0 versus 14.2 months, hazard ratio (HR) = 1.61; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.09–2.79, P < 0.01, RFS: 9.0 versus 6.2 months, HR = 1.61, 95% CI, 0.96–2.71, P < 0.05, Figure 1A and B]. The CA19-9 levels are the most commonly used biomarker for the management of patients with PDAC (38). Next, we performed the Kaplan–Meier analysis based on CA19-9 values in this cohort. As expected, high CA19-9 group was associated with poor OS (HR = 1.65; 95% CI, 1.10–2.48, P < 0.05, Supplementary Figure S2A, available at Carcinogenesis Online), while no significant differences were observed for RFS in this group (HR = 1.45; 95% CI, 0.90–2.35, P = 0.17, Supplementary Figure S2B, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics in PDAC patients

| Total | LAMC2 expression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n = 114 | Low (n = 81) | High (n = 33) | P valuea |

| Age, years | 0.745 | |||

| <65, n (%) | 56 | 39 | 17 | |

| ≥65, n (%) | 58 | 42 | 16 | |

| Gender | 0.576 | |||

| Male, n (%) | 75 | 52 | 23 | |

| Female, n (%) | 39 | 29 | 10 | |

| Tumor status | 0.277b | |||

| T1–2 | 10 | 9 | 1 | |

| T3–4 | 104 | 72 | 32 | |

| Nodal status | 0.349 | |||

| N0 | 31 | 20 | 11 | |

| N1 | 83 | 61 | 22 | |

| UICC stage (ver. 7) | 0.212 | |||

| IA, IB | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| IIA | 24 | 14 | 10 | |

| IIB | 73 | 55 | 18 | |

| III, IV | 13 | 8 | 5 | |

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | 0.192 | |||

| <37, n (%) | 27 | 21 | 6 | |

| ≥37, n (%) | 85 | 59 | 26 | |

| N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Tumor size (mm) | 0.037 | |||

| <40, n (%) | 59 | 47 | 12 | |

| ≥40, n (%) | 55 | 34 | 21 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.848 | |||

| Present | 92 | 65 | 27 | |

| Absent | 22 | 16 | 6 | |

UICC, International Union Against Cancer; N/A, not available. Bold values represents the values of P < 0.05.

aChi-square test.

bFisher’s exact test.

Figure 1.

Prognostic potential of LAMC2 for PDAC patients in the clinical cohort. Kaplan–Meier curves for (A) OS and (B) RFS in PDAC patients with high (blue) or low (red) LAMC2 expression in the clinical cohort. (C) Forest plot with HR of clinicopathological variables and LAMC2 expression in univariate and multivariate analysis by Cox regression model. The P values were obtained by the log-rank test for the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis.

To evaluate the clinical significance of LAMC2 levels, we performed univariate and multivariate analysis using the Cox’s proportional hazard model by considering other clinicopathological factors into the equation. Of interest, the multivariate analysis revealed that the patients with high LAMC2 expression were associated with poor OS (HR = 1.71; 95% CI, 1.09–2.68, P = 0.02, Figure 1C). These data suggest that LAMC2 expression was a potential prognostic marker in our in-house clinical cohort. To examine whether the expression of LAMC2 correlates with gemcitabine response, we next investigated LAMC2 mRNA expression of patients who were treated with gemcitabine therapy in adjuvant settings. Intriguingly, the patients with high LAMC2 demonstrated a significantly worse prognosis (OS: P < 0.05; RFS: P < 0.05, Supplementary Figure S2C and D, available at Carcinogenesis Online), highlighting that LAMC2 is not only a potential prognostic but also a potential predictive biomarker of therapeutic response to gemcitabine in patients with PDAC.

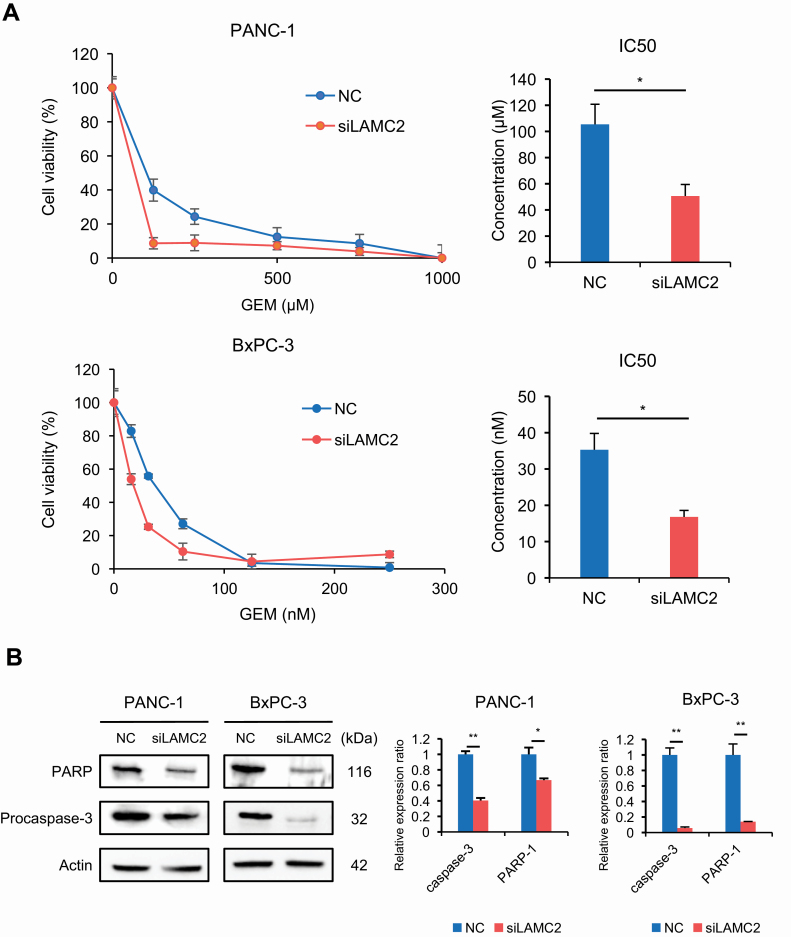

LAMC2 promotes gemcitabine resistance in PC cells

To determine the biological impact of LAMC2 in PDAC, we first examined the expression of LAMC2 in several PC cell lines to identify those with high endogenous LAMC2 expression (Supplementary Figure S3, available at Carcinogenesis Online). PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cell lines were subsequently chosen for siRNA transfection experiments since these cells demonstrated the highest levels of LAMC2 expression. Following siRNA-based experiments, suppression of LAMC2 was confirmed at both mRNA and protein expression levels (Supplementary Figure S4A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Considering that overexpression of LAMC2 is associated with gemcitabine resistance in our clinical cohort, we were curious to investigate the role of LAMC2 on the regulation of gemcitabine resistance in PC cells. Therefore, we examined the gemcitabine sensitivity of PC cells with or without LAMC2 siRNA. The IC50 values for gemcitabine in PANC-1 with or without LAMC2 siRNA were 105.42 ± 15.31 and 50.63 ± 8.85 µM, respectively; i.e. the IC50 of PANC-1 with LAMC2 siRNA was significantly lower compared with that of PANC-1 with negative control (P < 0.05; Figure 2A). Similarly, the IC50 value of gemcitabine in BxPC-3 cells with LAMC2 siRNA (16.78 ± 1.82 nM) was significantly lower than that of the negative control (35.29 ± 4.54 nM, P < 0.05). Furthermore, to investigate the underlying mechanism of the LAMC2 effect on PC cells, the degree of apoptosis was examined by performing western blotting assays for PARP-1 and procaspase-3 in PC cells treated with gemcitabine. Interestingly, these assays revealed that the expression of PARP-1 and procaspase-3 was significantly decreased in both cell lines transfected with LAMC2 siRNA at 72 h after treatment with gemcitabine in comparison with the control cells (Figure 2B). Taken together, these results suggest that the downregulation of LAMC2 may enhance the gemcitabine sensitivity in addition to apoptosis.

Figure 2.

LAMC2 facilitates gemcitabine resistance in PC cells. (A) The sensitivities of PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cells transfected with LAMC2 siRNA or negative control to gemcitabine were assessed by the WST-8 assay. The line graphs (left) are presented as the treated to control cell ratios, and the bar graphs (right) illustrate IC50 values. (B) Expression of PARP and procaspase-3 in PC cells transfected with LAMC2 siRNA or negative control. The siRNA transfected cells were treated with gemcitabine (PANC-1: 100 µM, BxPC-3: 30 nM) for 3 days, and western blotting for PARP and procaspase-3 were performed. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Error bars mean ± SD. GEM, gemcitabine; NC, negative control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

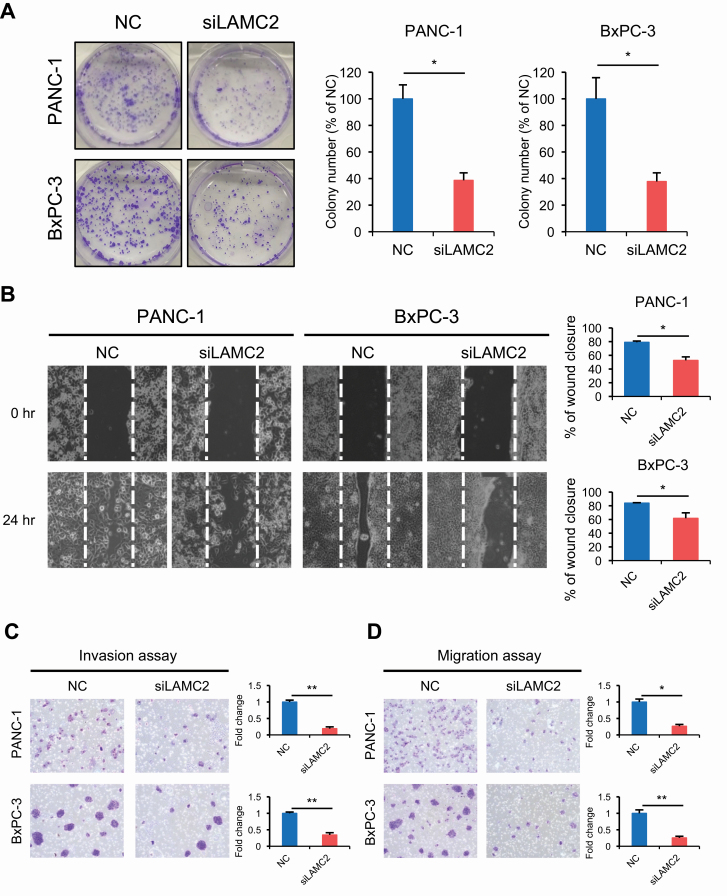

LAMC2 downregulation inhibits colony formation, as well as invasion and migration potential in PC cells

To further evaluate the functional significance of LAMC2 in PDAC, we next examined colony formation assays. Both cells treated with LAMC2 siRNA resulted in significantly reduced number of colonies compared with the negative control siRNA cells (Figure 3A). In view of the previous evidence that LAMC2 might influence the in invasive and migratory potential (25,39), we next performed migration and invasion assays. As expected, a wound-healing assay confirmed that LAMC2 depletion significantly inhibited cellular motility (Figure 3B). Moreover, transwell chamber assays demonstrated that LAMC2 inhibited cell invasion and migration ability of both PC cells (Figure 3C and D); indicating that LAMC2 might be intimately involved in the malignant potential of PC by enhancing colonogenic survival as well as the invasive and migratory potential of PC cells.

Figure 3.

LAMC2 downregulation inhibit the colony forming ability, migration and invasion in vitro. (A) Colony forming ability of PC cell lines transfected with LAMC2 siRNA or negative control. Colony formation assay was performed after 10 days incubation. (B) Wound-healing assay in PC cell lines transfected with LAMC2 siRNA or negative control. The distance of wound healing was measured and calculated as a percentage of the distance at 0 h. Original magnification, ×100. (C and D) Invasion and migration assays for PC cell lines transfected with LAMC2 siRNA or negative control. All experiments were carried out three times. Error bars mean ± SD. NC, negative control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

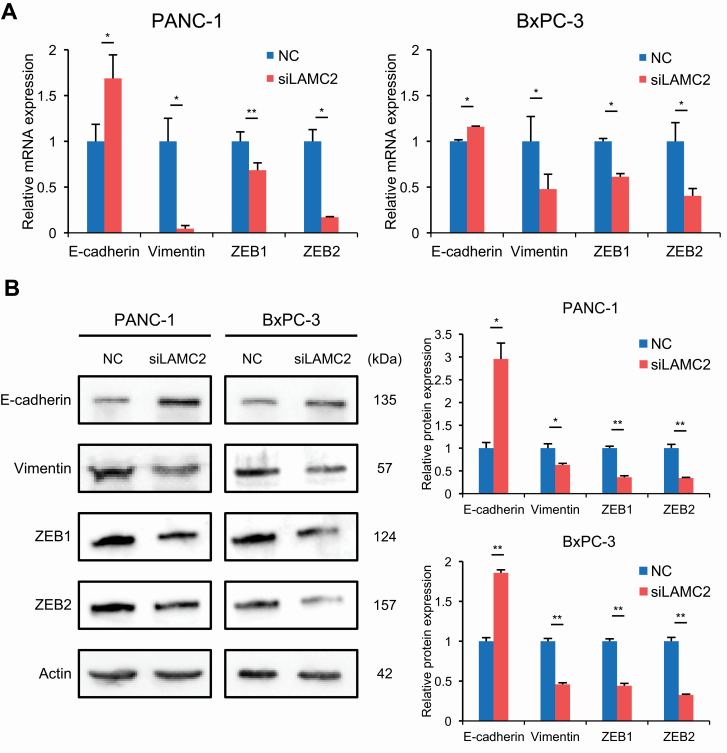

LAMC2 regulates chemoresistance through EMT in PC cells

Previous studies have shown that EMT plays an important role in mediating chemoresistance in various cancers (18,19). Moreover, EMT is known to be closely related to cancer invasion and migration (40). Therefore, we hypothesized that LAMC2 may mediate chemoresistance through regulation of EMT. To investigate this hypothesis further, we next examined the expression of EMT-related genes, E-cadherin, vimentin, ZEB1 and ZEB2 in PC cell lines treated with LAMC2 siRNA or negative controls. As expected, knockdown of LAMC2 in PC cell lines resulted in reduced vimentin, ZEB1 and ZEB2 expression, while E-cadherin expression was significantly upregulated compared with negative control transfected cells, at both mRNA (Figure 4A) and protein expression levels (Figure 4B). Thus, these results strongly suggest that LAMC2 may enhance the gemcitabine resistance through the induction of EMT.

Figure 4.

LAMC2 knockdown inhibits the EMT process in PC cells. EMT marker (E-cadherin, vimentin, ZEB1 and ZEB2) expression of PC cell lines transfected with LAMC2 siRNA or negative control by (A) quantitative RT–PCR and (B) western blotting. Western blot data were scanned by densitometry and analyzed using ImageJ software. Error bars mean ± SD. NC, negative control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

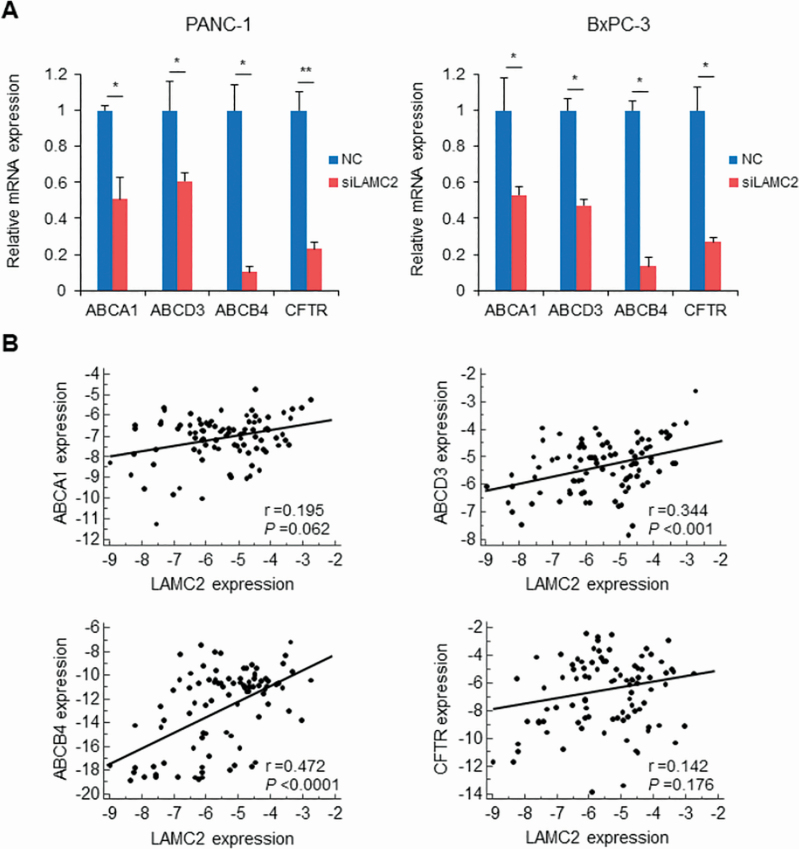

LAMC2 enhances gemcitabine sensitivity by regulating ABC transporters in PC cells

Emerging evidence indicates that ABC transporters are implicated in inducing chemoresistance in tumor cells (12,41). Therefore, we next evaluated whether the expression of ABC transporters mediate chemoresistance through the suppression of LAMC2. Interestingly, mRNA levels of ABCA1, ABCD3, ABCB4 and CFTR were significantly decreased in PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cell lines transfected with LAMC2 siRNA compared with negative control (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure S5, available at Carcinogenesis Online). To assess the clinical relevance of this finding, we investigated the association between LAMC2 and these four ABC transporter genes in cancer tissues from PDAC patients who received the gemcitabine therapy. While the expression of ABCA1 and CFTR was not correlated with LAMC expression, the expression of ABCD3 and ABCB4 positively correlated with LAMC2 expression (r = 0.344, P < 0.001 and r = 0.472, P < 0.0001, respectively; Figure 5B). Collectively, these data indicate that LAMC2 promote gemcitabine resistance through enhancement of ABCD3 and ABCB4 as well as EMT activation.

Figure 5.

LAMC2 regulates the expression of ABC transporter genes in PC cells. (A) Expression of ABC transporters (ABCA1, ABCD3, ABCB4 and CFTR) in PC cells transfected with LAMC2 siRNA or negative control. (B) Correlation between LAMC2 and ABC transporter mRNA expression in PDAC cancer specimens. Error bars mean ± SD. NC, negative control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is an essential component of tissues that constitute multicellular organisms (42). Accumulating evidence indicates that the ECM not only triggers cancer progression, but also plays a central role in mediating drug resistance in PDAC (43,44). Laminins are a family of large molecular weight glycoproteins that accumulate mainly in the ECM (20). In the present study, we have shown that high expression of LAMC2, which is one of the subunits of the protein laminin-332 (laminin-5), was associated with poor OS and RFS in PDAC patients in our clinical cohort. Moreover, we successfully identified that high expression of LAMC2 was predictive of therapeutic response to gemcitabine-based therapy. Furthermore, we demonstrated that downregulation of LAMC2 enhanced the sensitivity of gemcitabine in PC cells. We also showed that the inhibition of LAMC2 significantly induced apoptosis, as well as impaired invasion and migration capability. In addition, we identified that LAMC2 regulates EMT activation, and the expression of several ABC transporters, resulting in gemcitabine resistance in PC cells.

We first identified that PDAC patients with high expression of LAMC2 had significantly poorer prognosis. Moreover, the multivariate analysis for OS in our cohort revealed that LAMC2 expression is a prognostic biomarker for OS. Additionally, our data revealed that LAMC2 is an excellent marker for gemcitabine therapy in patients with PDAC. In this study, we performed the LAMC2 expression analysis by analyzing only one patient cohort. To overcome this limitation, future studies are required to confirm and support the validity of our findings.

To further understand the biological function of LAMC2 in PDAC prognosis, we investigated the ability of LAMC2 in PC cells through siRNA knockdown experiments. This result showed that silencing LAMC2 not only inhibited gemcitabine resistance through the induction of apoptosis but also the ability for colony formation, cell invasion and migration in PC cells. Consistent with our findings, other studies have suggested that LAMC2 might play a role in PDAC development (45,46). Although further investigations are required to fully understand the effects of LAMC2 inhibition, our results suggest that LAMC2 may serve as a promising prognostic biomarker and could play a pivotal role in malignant potential and gemcitabine resistance in PDAC.

Several previous studies have indicated that EMT is associated with gemcitabine drug resistance in PDAC. Moreover, the upregulation of LAMC2 facilitates EMT in several cancers (25,47). Herein, we hypothesized that LAMC2 may induce gemcitabine resistance through the induction of EMT in PDAC. As expected, our hypothesis was consistent with our results that silencing of LAMC2 significantly inhibited the EMT phenotype of PC cells, thereby resulting in an increased sensitivity to gemcitabine.

Furthermore, we showed that overexpression of LAMC2 significantly increased the mRNA levels of ABCA1, ABCD3, ABCB4 and CFTR in PC cell lines. Interestingly, ABCD3 and ABCB4 are significantly correlated with LAMC2 expression in PDAC patients. ABCD3 and ABCB4 function as an efflux pumps to limit the intracellular accumulation of cytotoxic drugs, including taxanes, anthracyclines and vinca alkaloids (48). However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have interrogated whether LAMC2 regulates ABC transporter expression in PC cells. We first carried out the downstream regulation of ABC transporters through knockdown of LAMC2 in PC.

Considering our findings, LAMC2 may be a potential therapeutic target in PDAC. A characteristic feature of PDAC is the presence of an abundant desmoplastic stroma (49). Moreover, PC cells induce a desmoplastic response within the tumor stroma including ECM (50). One limitation of our study is that we assessed LAMC2 expression only in PC cells. Therefore, co-culture with cancer associated with fibroblast or in vivo experiments will be needed for a more detailed analysis.

In conclusion, we have shown that LAMC2 promotes PC development and resistance to gemcitabine therapy by upregulating EMT-related markers and downregulating ABC transporters, ABCD3 and ABCB4. In addition, our clinical data support that high expression levels of LAMC2 correlated with poor prognosis and gemcitabine resistance in PDAC patients. Collectively, this is the first demonstration for the biological and clinical significance of LAMC2, as a result, it may be an effective therapeutic strategy for PC.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data are available at Carcinogenesis online.

Supplementary Figure S1. LAMC2 expression is associated with prognosis in PDAC patients in the publicly available datasets. Kaplan–Meier curves for OS in PDAC patients with high (blue) or low (red) LAMC2 expression in (A) GSE71729 and (B) TCGA datasets. The P values were obtained by the log-rank test for the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis.

Supplementary Figure S2. Survival analysis in the in-house clinical cohort. Kaplan–Meier curves for (A) OS and (B) RFS in PDAC patients with high (blue) or low (red) CA19-9 values in the clinical cohort. Kaplan–Meier curves for (C) OS and (D) RFS in PDAC patients who received gemcitabine-based adjuvant treatment with high (blue) or low (red) LAMC2 expression in the clinical cohort. The P values were obtained by the log-rank test for the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis.

Supplementary Figure S3. Expression status of LAMC2 in PC cell lines. mRNA levels of LAMC2 were measured by quantitative RT–PCR. Error bars mean ± SD.

Supplementary Figure S4. Knockdown of LAMC2 in PC cell lines. LAMC2 expression of PC cell lines transfected with LAMC2 siRNA or negative control by (A) quantitative RT–PCR and (B) western blotting. Error bars mean ± SD. NC, negative control. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Figure S5. The expression of ABC transporter genes which are not significant in pancreatic cancer cells lines transfected with LAMC2 siRNA or negative control. Expression of ABC transporters in pancreatic cancer cells transfected with LAMC2 siRNA or negative control (A: PANC-1, B: BxPC-3). Error bars mean ± SD.

Supplementary Table S1. Primer for RT–PCR.

Acknowledgements

We thank Satoshi Nishiwada, Geeta Sharma, Tatsuhiko Kakisaka, Yuma Wada, In Seob Lee, Divya Sahu, Xiaoe Zhang, Yinghui Zhao and Yuetong Chen for helping with performing the experiments and analysis.

Abbreviations

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- CI

confidence interval

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EMT

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- GEO

The Gene Expression Omnibus

- HR

hazard ratio

- LAMC2

laminin γ2

- OS

overall survival

- PC

pancreatic cancer

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- RFS

relapse-free survival

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

Funding

The present work was supported by the CA72851, CA187956, CA202797 and CA214254 grants from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. In addition, this work was also supported by a pilot research award from the City of Hope Ludwig Cancer Research-Hilton Foundation Partnership award.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Authors’ contribution

Study concept and design: Y.O. and A.G.; specimen providers: N.T.; acquisition of clinical data: N.T.; analysis and interpretation of data and statistical analysis: Y.O., S.N. and A.G.; drafting of the manuscript: Y.O., S.N., T.T. and A.G.

References

- 1. Siegel, R.L., et al. (2020) Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin., 70, 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Groot, V.P., et al. (2018) Patterns, timing, and predictors of recurrence following pancreatectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg., 267, 936–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rahib, L., et al. (2014) Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res., 74, 2913–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Von Hoff, D.D., et al. (2011) Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is an active regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II trial. J. Clin. Oncol., 29, 4548–4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neoptolemos, J.P., et al. ; European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer (2017) Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet, 389, 1011–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Conroy, T., et al. ; Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer; PRODIGE Intergroup (2011) FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med., 364, 1817–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Conroy, T., et al. ; Canadian Cancer Trials Group and the Unicancer-GI–PRODIGE Group (2018) FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med., 379, 2395–2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burris, H.A.III, et al. (1997) Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol., 15, 2403–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moore, M.J., et al. ; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (2007) Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J. Clin. Oncol., 25, 1960–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ueno, H., et al. (2013) Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine plus S-1, S-1 alone, or gemcitabine alone in patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer in Japan and Taiwan: GEST study. J. Clin. Oncol., 31, 1640–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Binenbaum, Y., et al. (2015) Gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Drug Resist. Updat., 23, 55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu, Y., et al. (2019) HNF1A inhibition induces the resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine by targeting ABCB1. EBioMedicine, 44, 403–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okazaki, J., et al. (2019) MicroRNA-296-5p promotes cell invasion and drug resistance by targeting Bcl2-related ovarian killer, leading to a poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Digestion, 101, 794–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yu, M., et al. (2012) Targeting tumor architecture to favor drug penetration: a new weapon to combat chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer? Cancer Cell, 21, 327–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shukla, S.K., et al. (2017) MUC1 and HIF-1alpha signaling crosstalk induces anabolic glucose metabolism to impart gemcitabine resistance to pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell, 32, 71–87.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Meng, Q., et al. (2018) Abrogation of glutathione peroxidase-1 drives EMT and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer by activating ROS-mediated Akt/GSK3β/Snail signaling. Oncogene, 37, 5843–5857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang, Z., et al. (2011) Pancreatic cancer: understanding and overcoming chemoresistance. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 8, 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zheng, X., et al. (2015) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is dispensable for metastasis but induces chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Nature, 527, 525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fischer, K.R., et al. (2015) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is not required for lung metastasis but contributes to chemoresistance. Nature, 527, 472–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Colognato, H., et al. (2000) Form and function: the laminin family of heterotrimers. Dev. Dyn., 218, 213–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miyazaki, K. (2006) Laminin-5 (laminin-332): unique biological activity and role in tumor growth and invasion. Cancer Sci., 97, 91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nguyen, C.T., et al. (2017) LAMC2 is a predictive marker for the malignant progression of leukoplakia. J. Oral Pathol. Med., 46, 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koshikawa, N., et al. (1999) Overexpression of laminin gamma2 chain monomer in invading gastric carcinoma cells. Cancer Res., 59, 5596–5601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liang, Y., et al. (2018) LncRNA CASC9 promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma metastasis through upregulating LAMC2 expression by interacting with the CREB-binding protein. Cell Death Differ., 25, 1980–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moon, Y.W., et al. (2015) LAMC2 enhances the metastatic potential of lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Differ., 22, 1341–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang, D., et al. (2019) LAMC2 regulated by microRNA-125a-5p accelerates the progression of ovarian cancer via activating p38 MAPK signalling. Life Sci., 232, 116648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ke, A.W., et al. (2011) CD151 amplifies signaling by integrin α6β1 to PI3K and induces the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in HCC cells. Gastroenterology, 140, 1629–1641.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aokage, K., et al. (2011) Dynamic molecular changes associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and subsequent mesenchymal-epithelial transition in the early phase of metastatic tumor formation. Int. J. Cancer, 128, 1585–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sánchez-Tilló, E., et al. (2011) β-Catenin/TCF4 complex induces the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-activator ZEB1 to regulate tumor invasiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 19204–19209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hlubek, F., et al. (2001) Expression of the invasion factor laminin gamma2 in colorectal carcinomas is regulated by beta-catenin. Cancer Res., 61, 8089–8093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kandimalla, R., et al. ; T1 Colorectal Cancer Study Group (2019) Gene expression signature in surgical tissues and endoscopic biopsies identifies high-risk T1 colorectal cancers. Gastroenterology, 156, 2338–2341.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Izumi, D., et al. (2019) A genomewide transcriptomic approach identifies a novel gene expression signature for the detection of lymph node metastasis in patients with early stage gastric cancer. EBioMedicine, 41, 268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nishiwada, S., et al. (2020) A microRNA signature identifies pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients at risk for lymph node metastases. Gastroenterology, 159, 562–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakagawa, T., et al. (2020) JMJD2A sensitizes gastric cancer to chemotherapy by cooperating with CCDC8. Gastric Cancer, 23, 426–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sakatani, A., et al. (2019) Melatonin-mediated downregulation of thymidylate synthase as a novel mechanism for overcoming 5-fluorouracil associated chemoresistance in colorectal cancer cells. Carcinogenesis, 40, 422–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Okugawa, Y., et al. (2014) Metastasis-associated long non-coding RNA drives gastric cancer development and promotes peritoneal metastasis. Carcinogenesis, 35, 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yoshida, K., et al. (2017) Curcumin sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine by attenuating PRC2 subunit EZH2, and the lncRNA PVT1 expression. Carcinogenesis, 38, 1036–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chan, A., et al. (2014) Validation of biomarkers that complement CA19.9 in detecting early pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res., 20, 5787–5795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huang, D., et al. (2017) Overexpression of LAMC2 predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients and promotes cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Tumour Biol., 39, 1010428317705849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Takehara, M., et al. (2020) Cancer-associated adipocytes promote pancreatic cancer progression through SAA1 expression. Cancer Sci., 111, 2883–2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ravindranathan, P., et al. (2019) Oligomeric proanthocyanidins (OPCs) from grape seed extract suppress the activity of ABC transporters in overcoming chemoresistance in colorectal cancer cells. Carcinogenesis, 40, 412–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hynes, R.O. (2009) The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science, 326, 1216–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tian, C., et al. (2019) Proteomic analyses of ECM during pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression reveal different contributions by tumor and stromal cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 19609–19618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Amrutkar, M., et al. (2019) Secretion of fibronectin by human pancreatic stellate cells promotes chemoresistance to gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer cells. BMC Cancer, 19, 596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kosanam, H., et al. (2013) Laminin, gamma 2 (LAMC2): a promising new putative pancreatic cancer biomarker identified by proteomic analysis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma tissues. Mol. Cell. Proteomics, 12, 2820–2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mitsunaga, S., et al. (2010) Nerve invasion distance is dependent on laminin gamma2 in tumors of pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Cancer, 127, 805–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pei, Y.F., et al. (2019) Silencing of LAMC2 reverses epithelial-mesenchymal transition and inhibits angiogenesis in cholangiocarcinoma via inactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway. Am. J. Pathol., 189, 1637–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wen, C., et al. (2019) Curcumin reverses doxorubicin resistance via inhibition the efflux function of ABCB4 in doxorubicin-resistant breast cancer cells. Mol. Med. Rep., 19, 5162–5168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Olson, P., et al. (2009) Cancer. Breaching the cancer fortress. Science, 324, 1400–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hosein, A.N., et al. (2020) Pancreatic cancer stroma: an update on therapeutic targeting strategies. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 17, 487–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.