Abstract

Mimicry is exhibited in multiple scales, ranging from molecular, to organismal, and then to human society. ‘Batesian’-type mimicry entails a conflict of interest between sender and receiver, reflected in a deceptive mimic signal. ‘Müllerian’-type mimicry occurs when there is perfect common interest between sender and receiver in a particular type of encounter, manifested by an honest co-mimic signal. Using a signalling games approach, simulations show that invasion by Batesian mimics will make Müllerian mimicry unstable, in a coevolutionary chase. We use these results to better understand the deceptive strategies of SARS-CoV-2 and their key role in the COVID-19 pandemic. At the biomolecular level, we explain how cellularization promotes Müllerian molecular mimicry, and discourages Batesian molecular mimicry. A wide range of processes analogous to cellularization are presented; these might represent a manner of reducing oscillatory instabilities. Lastly, we identify examples of mimicry in human society that might be addressed using a signalling game approach.

Keywords: Müllerian mimicry, Batesian mimicry, cue mimicry, mimicry ring, signalling game, COVID-19

Ognuno vede quel che tu pari, pochi sentono quel che tu sei.

(Everyone sees what you appear to be, few really know what you are.)

Niccolò Machiavelli, Il Principe

1. The imitation game: mimicry and signalling game theory

Niccolò Machiavelli has been much maligned among philosophers for emphasizing the utility of deception in his book Il Principe. However, deception—along with cheap and imitative signalling—turns out to be rather natural when rational agents strategically interact in information asymmetric contexts. In this paper, we formally study the utility of deception, from a signalling games perspective, focusing on mimicry and its universal occurrence, in natural and artificial worlds.

In situations of conflict, deception can occur because of information asymmetry, which refers to incomplete information regarding a situation or object and differential states of knowledge held by participants. We suggest that the existence of information asymmetry in nature has deeply affected fundamentals of the genome, organismal biology, and human society and its institutions. Molecular, organismal and cultural evolution are all profoundly influenced by information asymmetry. Here we attempt to unify its effects on all three evolutionary processes, via signalling game theory.

A common form of deception is that of deceptive mimicry. ‘Mimicry’ refers to imitation, and is expected to bring fitness benefits to the mimic. ‘Batesian’ mimicry was the first type of mimicry to be formally described. It involves a ‘mimic’ organism that imitates a ‘model’ organism in order to deceive a third organism, the ‘dupe’. Typically, a non-toxic species will mimic a toxic species, deceiving a potential predator into wrongly avoiding the non-toxic mimic [1]. Batesian mimicry implies a loss of fitness of the dupe, because it is deprived of a meal, and of the model, given that the value of the warning signal to potential predators is diluted.

One way of reducing Batesian-type mimicry and establishing the honesty of a signal is through the use of costly signals (in biology this is known as Zahavi’s handicap principle [2]). A significant price is involved in the creation of a costly signal, thus deterring mimicry and other forms of deception, as the signal is prohibitively expensive to imitate [2,3], thus the signal reveals the true type of the sender.

Mimicry may also be cooperative (mutualistic), when two organisms converge on a common signal that is sent to a third organism, to the benefit of all three; this signalling is termed ‘Müllerian’ mimicry [4]. This type of mimicry was originally characterized for toxic animals that share a common warning signal to potential predators. This is easier for a predator to learn, in turn benefiting the animals that send the warning signal. This type of mimicry is non-deceptive, given perfect common interest between the participants.

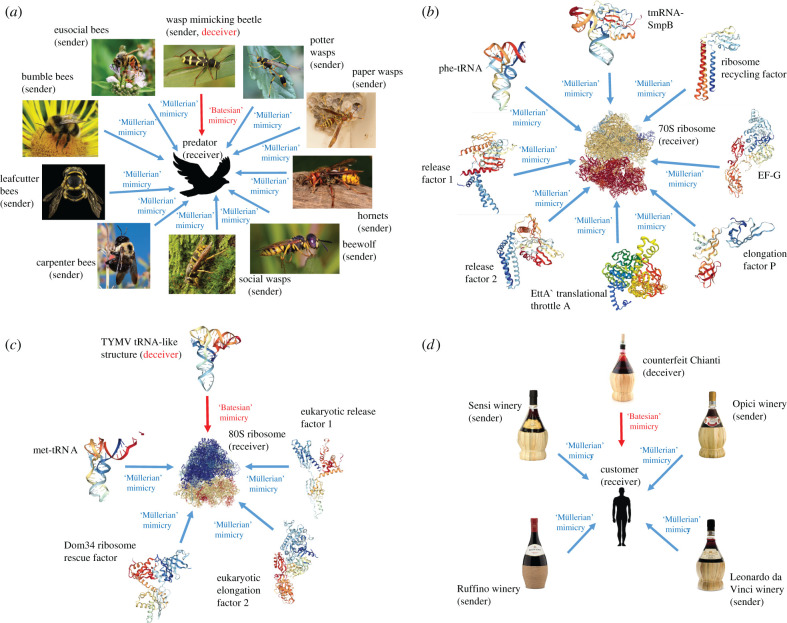

When more than two organisms share a common signal in a cooperative fashion, they may form a Müllerian mimicry ring. A well-known example of a mimicry ring is that of bees and wasps (figure 1a), which share black and yellow markings as a warning of toxicity. Further examples of mimicry rings are identified in this work.

Figure 1.

Müllerian mimicry rings at multiple levels. (a) An organismal Müllerian mimicry ring (adapted from [5]); (b) a bacterial Müllerian-type tRNA mimicry ring; (c) a eukaryotic Müllerian-type tRNA mimicry ring; (d) an economics Müllerian-type mimicry ring formed by Chianti wines. (a) A wide variety of bees and wasp species. These all possess a venomous sting and share a common warning signal, black and yellow markings, which defines them as Müllerian co-mimics. The Clytus arietis beetle is a Batesian mimic, as it shares the same black and yellow markings but is non-toxic. Two different molecular Müllerian tRNA mimicry rings exist in bacteria and eukaryotes, orientated around the 70S and 80S ribosome, respectively (b) and (c). Prokaryotic release factor 1 and 2 (b) and eukaryotic release factor 1 (c) have parallel roles in translation but are not homologous. tRNA mimicry evolved independently in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. This observation implies that the original model molecule was tRNA, as opposed to a tRNA-like protein being the model for tRNA molecules themselves. In (c), a Batesian-type tRNA mimic from turnip yellow mosaic virus (TYMV) is shown. The tRNA mimic is located 3’ of the virus genomic DNA and enhances viral replication [6], benefiting the virus sender gene but not the receiver (the host ribosome). In (d), the characteristic Chianti bottles containing wines from different Tuscan vineyards form a Müllerian mimicry ring, signalling to the consumer the type of wine. Fake Chianti mimics the bottle; this is Batesian-type mimicry. For more detail on Chianti bottle mimicry, see electronic supplementary material, §5. Sources for photos and three-dimensional structures are in the electronic supplementary material.

A third type of mimicry is termed ‘cue’ mimicry [7]. A cue is an observable feature that may be inanimate, or of biological origin, and is non-strategic, not being intended as a signal. A signal, in contrast, has a communication purpose, or meaning [8], and can be regarded as strategic. In cue mimicry, a cue is mimicked by an organism, typically to deceive another organism, which could be predator or prey. This can involve blending into the background (crypsis or camouflage). Table 1 gives examples of the different aspects of mimicry observed in biotic systems at the different levels of organization: molecular, organismal and societal.

Table 1.

Mimicry at multiple levels Mimicry operates at all levels of biological organization. Listed in the table are a number of illustrative examples of the major characteristics of mimicry.

| feature of mimicry | molecular level | organismal level | societal level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batesian mimicry | viral tRNA mimics imitate host tRNAs (figure 1c) | the beetle Clytus arietis is a Batesian mimic of bees and wasps (figure 1a) | asymptomatic patients who go undetected in contact tracing analysis, phishing attacks. Psychopaths display affective mimicry (mimicry of emotions) [9] |

| Müllerian mimicry | cellular tRNA isoacceptors are co-mimics, as are the common 5’ leaders and 3’ polyA tails of mRNAs for different genes (§3.4) | bees and wasps are Müllerian co-mimics, sharing a common signal of a black body with yellow stripes | the Anonymous hacktivist collective is a manifestation of cooperative mimicry, as are voluntary COVID-19 research teams |

| mimicry ring | tRNA molecular mimicry ring comprising tRNAs and tRNA-like mimics where the receiver is the ribosome (figure 1b,c) | multiple bee and wasp species form a mimicry ring, where the receiver is a potential predator (figure 1a) | the Silkroad vendor website, used to sell illegal products and services, has spawned offspring after it was shutdown that mimic the appearance and functionality of the original website, including the webmaster, Dread Pirate Roberts. Pirate flags themselves constitute a mimicry ring, discussed in electronic supplementary material, §1 |

| cue mimicry | cancers can blend into the host tissue by a variety of mechanisms such as surface antigen masking by sialic acids [10], downregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I expression [11] and truncation of oligosaccharides on cell surface proteins [12]. Devil facial tumour disease 1 (DFT1) is a contagious cancer in Tasmanian devils, which blends into the somatic background, facilitated by loss of MHC class I molecules [13] | spiders and chameleons can blend into their respective backgrounds | zero-day vulnerabilities are very difficult to detect as they blend into the source code. Some may occur accidentally; others may be deliberately introduced. A form of cue mimicry in cyberspace is protocol spoofing, which describes a means of concealing a communication within another type of communication so as to avoid its detection by a government or service provider that could potentially snoop. Additional examples include Tor’s anonymization routing, anti-censorship and free speech technologies. A recent example is found with protesters in Hong Kong, who, aware that officials and police use biometrics such as facial identification, have used face masks to protect their anonymity [14] |

| complexity and stability | simple, stable, close to optimal | moderately complex and stable, but requires costly mechanisms that might cause species extinctions [15] | highly complex, involving multiple institutions with complex checks and balances. Stability is poorly understood |

| costly (honest) signal | the tertiary structure of proteins represents a costly signal difficult to mimic [5] | animals display costly signals such as sexual ornamentation [2] | proof of work by bitcoin miners is a costly signal. Other examples of costly signalling include risk taking by health workers, conspicuous consumption [16], educational attainment [3] and potentially cognitive capacity [17] |

Signalling game theory provides an ideal framework for analysing the different types of mimicry, providing a better understanding of its evolution and purpose. Signalling games involve an incomplete information setting, which results in the transmittal of a strategically chosen signal between two players, from a sender to a receiver, resulting in an action by the receiver [18]. The strategically chosen action by the receiver results in an increase in utility (analogous to organismal fitness), which is distributed to the players. If the signal is honest, then utility accrues to both the sender and the receiver; here the signal is mutually beneficial. If the signal is deceptive, however, then the sender experiences an increase in utility, but the receiver experiences a shortfall in its expected utility [19].

The concept of ‘replicator’ dynamics introduces an evolutionary aspect to repeated games [20]. This refers to the propensity of a player with a strategy that produces a higher utility to preferentially replicate within a population. Owing to replicator dynamics, a sender with a signalling strategy that results in increased utility, or a receiver with an action strategy that produces a higher utility, will be more likely to become fixed in the population. Repeated games facilitate learning by the receiver to recognize the signal; this dynamic can occur in the lifetime of the organism or over generations.

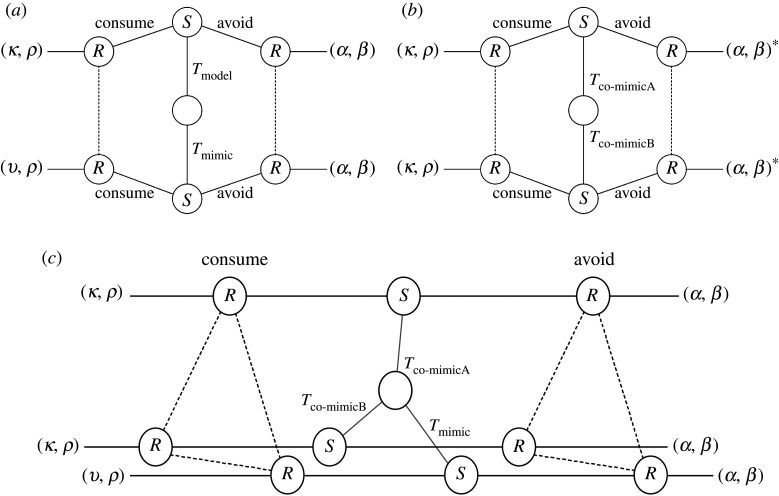

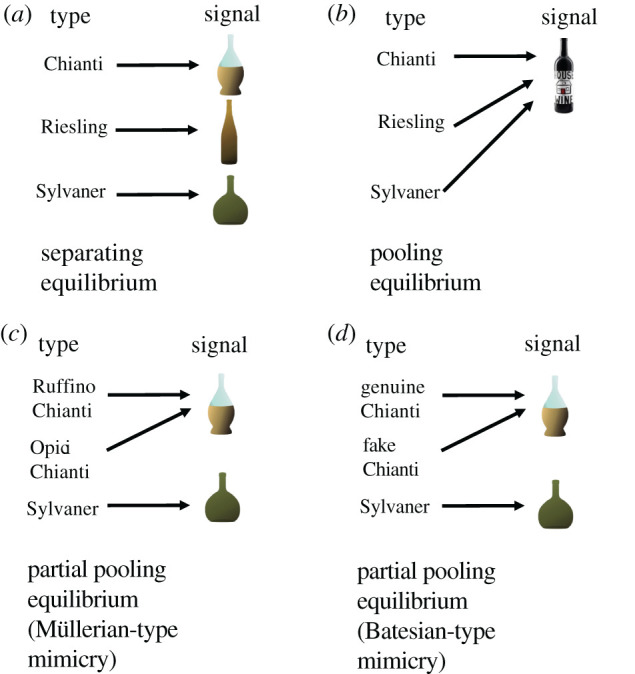

Different types of signalling equilibria are associated with different types of mimicry. A ‘separating’ equilibrium (also known as a signalling system or Lewis signalling game [21]) is where a specific signal from a sender results in a specific action by the receiver, to their mutual benefit. The signal is honest, providing an accurate indication of the true type of the sender (figure 2a). A ‘pooling’ (or babbling) equilibrium is where the signal has no meaning and does not result in a specific action by the receiver [23] (figure 2b). Pertinent to mimicry is the partial pooling equilibrium. Here, there are at least three senders, and two of them will send the same signal to the receiver, which results in the same action [24]. Both Müllerian and Batesian mimicry correspond to a partial pooling equilibrium (figure 2c,d, respectively).

Figure 2.

Separating, pooling and partial pooling equilibria. A separating equilibrium (a) occurs where senders of different types send distinct signals, each of which elicits a specific action by the receiver, to the benefit of both sender and receiver [22]. A pooling or babbling equilibrium (b) is where senders of different types send the same signal, and the resulting action of the receiver is always the same. Most relevant to the phenomenon of mimicry is the ‘partial pooling’ equilibrium. Here, two or more senders of different types may send the same signal to a receiver, eliciting the same action, while other senders send different signals. Both Müllerian-type (c) and Batesian-type (d) mimicry can be represented by a partial pooling equilibrium. The partial pooling equilibrium can represent a common signal that two or more senders have converged upon, to their mutual benefit (Müllerian). Alternatively, it can also describe deceptive signalling by one sender, which imitates or mimics a signal sent by one of the other senders (Batesian). Different types of wine (Chianti, Riesling and Sylvaner), which each possess distinctive wine bottles (the signal), are used to illustrate the different types of equilibria. In (a), the distinct bottles act as a separating equilibrium. In (b), all three types of wine use the same bottle; this is a pooling equilibrium. In (c), different Chianti wineries, Ruffino and Opici, use the same characteristic Chianti bottle; this is cooperative Müllerian-type mimicry. In (d), fake Chianti manufacturers use the typical Chianti bottle to deceive customers into buying the wine. This is Batesian-type mimicry. Aposematic mimicry represents a special case of partial pooling equilibrium with a pooled signal of toxicity, contrasting with organisms that lack the signal, the action of the receiver being ‘avoid’ and ‘consume’, respectively.

Müllerian mimicry rings may be viewed as assuming a star network structure. A Shapley value is generated among all the senders and the receiver that constitute the mimicry ring (the Shapley value quantifies how fair a distribution of the total gain is among the players in a coalitional game [25]). An important observation is that Batesian mimicry is frequency dependent: the higher the frequency of Batesian mimics in a population, the less their fitness advantage. This is because too many Batesian mimics will dilute the value of the signal [26], to the extent that selection processes view better discrimination mechanisms as advantageous over the continued use of the diluted signalling system [27]. Extensive form decision trees for Batesian and Müllerian mimicry are shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Extensive form decision trees for signalling strategies involving mimicry. These trees (solid edges) show the sequence of interactions between players in a game, and the respective pay-offs, depending on the strategies that they follow. Trees are shown for (a) Batesian-type mimicry, (b) Müllerian-type mimicry and (c) mixed type. Play starts in the centre circle with a decision taken by nature selecting the type of sender encountered by the predator. The organism’s signals of identity are modulated by the predator’s decision function to result in two effective signals: avoid or otherwise (consume). The dotted lines indicate information sets, marking the extent of receiver uncertainty of the sender’s type. In particular, at the stage of the game when the receiver selects an action, they know the signal but remain uncertain of the sender’s true type. This uncertainty is summarized with the information set: the receiver will know which set they are in, but not the particular state. The receiver has two potential options: avoid or consume. The utility pay-offs are in brackets (S, R), and the Nash equilibrium is indicated by an asterisk. In (a) there are two types of sender, Tmodel and Tmimic, corresponding to the model and Batesian mimic, respectively. In (b), the sender may be of type Tco-mimicA or Tco-mimicB, corresponding to two Müllerian co-mimics, A and B. In (c), we show how scenarios are composed to form a mixed type.

In this work, we use signalling game theory to define a generalized model of the three forms of mimicry, and indicate its application to mimicry at the molecular, organismal and societal levels. In particular, using simulations of our signalling game model of mimicry we focus on oscillatory effects in coevolutionary chases between mimic and model, the assembly of Müllerian mimicry rings and the stability of the rings to invasion by Batesian mimics.

2. Methods

We construct a mathematical model to study signal evolution in these informational asymmetric scenarios. We start by formalizing population structure as an ensemble of communicating types (species), with each type representing a population of agents. Next, we define the space of signalling strategies, the signalling game encounters and the differing rewards for encounters due to type and receiver action. We will assume a rudimentary decision function for the uninformed receiver that imposes a decision surface in signal space. Differing signalling strategies will yield differing rewards from encounters: to guide evolution we assume mechanisms that relate rewards to replication rates within type. Strategies that gain higher reward will spread at a quicker rate than their lower yielding peers. Additionally, we incorporate a stationary mutation process that generates new strategies periodically. We thus incorporate natural selection, replication and mutation for each type within an evolutionary game.

With the evolutionary game defined we set the stage for analysing mimicry forms and their dynamic consequences.

2.1. Population structure and predation rewards

Agents are organized into type groups. Aside from constraining replication, types will determine outcomes of certain receiver actions during encounters. For example, as predators encounter other organisms in the wild, predation decisions are made using markings (signal). Poor metabolic outcomes are possible and the organisms’ type will be the most important factor if predation occurs. The simplest interesting scenario is when two types have related markings but one is toxic while the other is nourishing.

We denote the population of agents that are type x as τx; the population size of type X will be denoted Nx = |τx|. The population structure will refer to the types (and population sizes) within a model. For example, if there are m types, all agents can be partitioned as .

The predator’s metabolic reward function for predation outcomes will depend on an agent’s type. Assuming a predator consumes agent a, the reward will be

| 2.1 |

In our simplest scenario, m = 2, the first type toxic and the second type nourishing is represented by values: r1 < 1 < r2. The metabolic reward of 1 can be thought of as neither loss nor gain.

2.2. Signalling strategy and predation decisions

The signalling space is a set of distinguishable features, within the receiver’s sensory and sender’s combined repertoire of expression. All relevant signals can be represented within a signal space, a vector space Γ = ℝN for sufficiently large N. The signal space may consist of morphological attributes, phenotypic attributes, markings, sounds, smells, coloration or other attributes sensed or communicated that factor into the receiver’s predation decision. For agent a, the signalling strategy will be denoted s(a) ∈ Γ.

Additionally, we will use the same space Γ (along with a scalar threshold) as a parameter space for the receiver’s decision function. In our simple scenario, we model the predator’s choice of action as: predation or avoidance by partitioning Γ into various regions which prescribe those actions.

The simplest decision model for the agent receiver will use a private reference point q ∈ Γ termed the avoidance feature; this will identify the centre of an avoidance region in Γ. Using the cosine distance, cosd(x,y) = 1 − (〈x,y〉/||x||||y||), the avoidance region is symmetric around the avoidance feature, with radius determined by the threshold parameter δ ∈ [0, 2]. This results in the decision function

| 2.2 |

Predators will use the decision function (2.2) and inherited private parameters q, δ to select actions during encounters. Equation (2.2) partitions the signal space into two geometric regions: the avoidance region and the predation region. If an encountered organism (no matter the type) signals within the avoidence region, the predator will avoid the organism.1 For example, if the encountered organism nearly matches the predator’s avoidance feature (having cosine distance less than δ), then the predator will avoid the organism. On the other hand, if the organism signal is dissimilar to the avoidance feature (having cosine distance greater than δ), the predator consumes the organism.

2.3. Signalling games and metabolic objectives

Signalling games start with nature, which selects the sender type. Nature provides agent encounters, assigning the type (identity) for the organism (sender) and receiver (predator). Next the sender transmits a message s ∈ Γ. The receiver, having received the sender’s message but uncertain of the sender’s type, must select an action to yield differing rewards depending on the combination of sender type, signal and action.

Abstractly this pay-off function is represented by

| 2.3 |

where the first two symbols represent the sender’s type and signal; the following two symbols are the receiver’s action and type (also selected by nature if there are multiple receiver types); finally the right-hand side represents the rewards for sender and receiver, in that order.

The signalling game in our scenario can be viewed most clearly during an encounter scenario, when a predator encounters an organism of uncertain type sending a certain signal (markings or coloration). The predator is the uninformed receiver who must select an action: predation or avoidance.

The repertoire of types (formalized as population structure) that nature presents to predators during encounters will play a significant role in signalling game outcomes. We illustrate how this affects the signalling game structure in figure 3, where we illustrate extensive forms for signalling games with a variety of population structures. We provide a general reward matrix (in table 2) for game outcomes; this table includes the types used within the population structures studied. We use these types to create various ensembles for analysis, and consider the types of mimicry they express. Our results suggest that the population structure and predation reward function are critical to understanding how mimicry is formed, maintained and destroyed in populations.

Table 2.

A game pay-off matrix describes outcomes between a predator and various types of organisms. Note that co-mimics are no different from the model and are considered Müllerian, while the mimic is Batesian. An example game parameterization used throughout the results section is: α = 0.4, β = 1.0, κ = 0.1, ρ = 0.1 and υ = 1.2.

| pay-off (predator, prey) encounter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| predator action | model | mimic | co-mimic-A | co-mimic-B |

| avoid | (α, β) | (α, β) | (α, β) | (α, β) |

| consume | (κ, ρ) | (υ, ρ) | (κ, ρ) | (κ, ρ) |

To keep our descriptions as simple as possible we will consider only one type of predator in the study. The outcome from signalling games is given by the reward function ; specifically

| 2.4 |

The preceding equation (equation (2.4)) may be further modified by the parameter ε, such that 0 < ε < 1 represents the reduction in fitness (reproductive likelihood) for a sender organism consumed during the encounter. Values of apply for predation; the small deduction η < 1 accounts for metabolic loss and deferred replenishment for avoidance.

2.4. Best receiver action

Within a population of replicating strategies guided by evolution, more successful strategies will have increased replication rates. To explore these dynamics further, we consider how the utility optimization implicitly depends on the statistical distribution of types. We consider the distribution μ, which measures the probability of type given a specific signal s.

Letting

| 2.5 |

with U2, the receiver’s utility, and μ(t|s), the probability of type t given signal s. The best response may be taken as an argument policy maximization which seeks the best action as yielding the highest reward averaged over all agents of all types,

| 2.6 |

By integrating over the signal space, calculation of the best response is revealed as a geometric problem

| 2.7 |

where λ(q,δ,t) is the proportion of t-type population with the signalling strategy (signal or markings) contained in the avoidance region (q, δ). Note the interesting case for mixed types, for example if r1 < 1 − η < 1 < r2 in our simplest scenario. The selection of parameters for the best response is a non-trivial instance of the geometric knapsack problem. The dynamic evolutionary games further place dependence on the frequency or distribution of signals. The geometric interpretation gives a sense of the type of distributed co-optimization as it occurs during evolutionary games, and provides an analogous geometric problem involving reinforcement and adversarial learning.

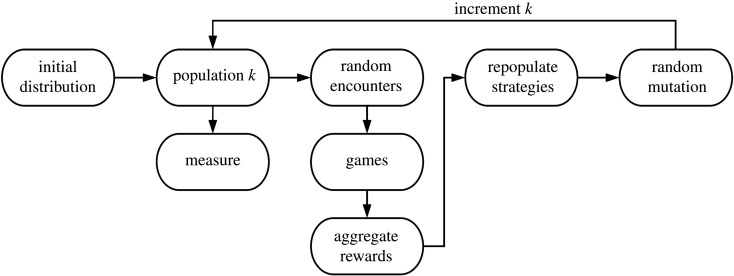

2.5. Evolutionary games

In evolutionary games the dynamic evolution of strategies within a population is considered. We illustrate the phases of the evolutionary game in figure 4 and summarize the three main steps as: meet, mate (and repopulate) and mutate. Each type in the population structure is a component in the evolution processes; the repopulate and mutation phases will be self-contained to the type component. The encounter phase intermingles the agent types, coupling the component processes with signalling games that define the evolving objectives and problem-solving requirements linking outcomes to replication rates.

Figure 4.

The evolutionary game defines evolving objectives for signalling strategies. The process measures signalling strategies by their metabolic/protection rewards. The process guides evolution by constructing a relation between strategic rewards and reproduction implemented with statistical boosting. The process architecture is simple, but worth noting that each type in the population structure forms a component in the evolution processes. During the encounter phase the type components intermingle with signalling games. Accordingly, the strategic objectives are dynamic, dependent on frequency (of strategies used by other types) and can behave in complex ways.

Initialization: we will define a constant size population of agents for each type t as nt. We use an initial distribution to generate nt pure strategies and assign those to the agents of each type. We set the loop count k to be zero. Measure: for each time step k we record measures of the population to study empirically the evolving distribution of quantities. Meet/encounter: these are generated from an encounter distribution which generates random pairs with predator and prey agents. Games for every encounter: we use the sender type, sender signal and receiver (predator) avoidance region to calculate the rewards gained from the signalling game. Score: for each type, for each strategy i, , where gj is the total reward received by all agents who use strategy j during encounters. The vector ϕ forms a probability distribution over the set of strategies. Mate/repopulate: with details given in the electronic supplementary material, ϕ is slightly modified to derive Φ, which is used to re-select nt strategies (from Multinomial(nt, Φ)). These new strategies are assigned to the agents of type t. Note that this technique is nothing but a simple form of statistical boosting: the better the score the more likely to re-select. Said differently, this phase will prefer to replenish better performing strategies over poorly performing strategies. Mutation: next, a random mutation process is applied to agents whose strategies are mutated in place. Mutation acts to generate and probe novel strategies which the population can try. Increment: time step k is incremented and a next population is defined; processing continues from the Measure step.

Under natural selection a mimicry ring appears to be in a stable equilibrium because, although mutation allows out-of-equilibrium signalling, it presumably offers only less benefit and accordingly will not survive for long. Once established in a ring, we expect mimicry to endure and evolve. While a Müllerian ring appears stable in isolation, considerable advantages await Batesian mimics to invade the ring. Under natural selection, such invasions lead to loss of rewards by receivers. As such the question resurfaces as to how many Batesians it will take to destabilize the ring.

The methods outlined are analysed rigorously to evaluate the subjects of ring formation and robustness (to Batesian invasions) with simulation studies of evolving populations of agents under a variety of population structures. Further details of the methods and simulations can be found in electronic supplementary material, §§2 and 7.

3. Results and discussion

The evolutionary game, discussed earlier, expresses a range of mimicries. Here we will further illustrate and discuss the surprisingly diverse dynamics expressed for a variety of population structures. We will draw attention to three prominent behaviours: (i) the emergence of Müllerian rings and their stability, (ii) the adversarial behaviour introduced by Batesian mimics, and (iii) the behaviour of mixed-mode mimicry. We will illustrate how the mixed-mode expresses both the emergence of rings and the antagonistic dynamics of Batesian types, but further we study how the Batesian types interact with the ring and how they destabilize it and/or, eventually, cause its complete collapse. To investigate this phenomenon, we illustrate how the mixed-mode system evolves by transitions from one game equilibrium to another, and the conditions that trigger transitions within the model. We also draw connections to existing biological studies where our results bear close resemblance to natural phenomena.

3.1. Emergence of rings

In systems with potential common interest for coordinated behaviours, we observe the emergence of Müllerian rings. Once established we expect the ring to endure and evolve. This dynamic is observed most clearly in systems comprising only toxic types and predators, such as system (1, 0) and (2, 0), which have, respectively, one and two toxic types, one predator but zero non-toxic types. In these systems, we observe a signal locking phenomenon, where the predator and toxic types adapt and hold a purposeful signalling convention. Initialized in ‘babbling,’ where encounters between predator and toxic types invariably lead to predation, either a mutant predator (with advantageous avoidance behaviour) or a mutant toxic organism (which the predator instinctively avoids) will eventually occur. Once such an event occurs, both populations quickly replicate those strategies catalysed by the increased rewards they offer, as can be seen in electronic supplementary material, figures S7(b) and S11(b). Electronic supplementary material, figure S8 illustrates the transition and the rapid crossover the populations take. This transition will be driven by the new strategies being favoured and boosted in replication. Additionally, this will coincide with the abandonment and extinction of many inferior strategies for the singular new one; accordingly, as the population became more clonal, we observed a decreased variance in strategies. The temporal requirements for such a transition can be understood as the expected search time for ‘paths to cross’. Within a few generations a ‘separating equilibrium’, where the signal is used to distinguish type (e.g. the receiver’s basic problem of determining what to eat), takes over and a Müllerian ring is formed. Once established, we expect the ring to endure, its stability achieved by selective advantage, stumbled upon by mutants probing alternative strategies. Should a mutant strategy break the signalling convention their replication rates are attenuated by the less satisfying outcome. The stability of the ring can be observed in electronic supplementary material, figures S7 and S11; these plots show the cosine distance between the strategies of encountering organisms. Any encounter within the avoidance region will result in the predator avoiding the organism, while predating otherwise. Clearly, the avoidance region is an attractor and absorbing state. Additionally, the avoidance decision can be interpreted to delineate foreground from insignificant or abiotic background to address cue mimicry forms. We emphasize that signal locking need not imply a constant or frozen signal convention (indicated by the motion of centroids in electronic supplementary material, figures S9 and S12). Still, this possibility points to an interesting mathematical question; namely, of asymptotic behaviour as the ring grows in size.

As the ring endures, substantial advantages await Batesian mimics to invade. Since these invasions weaken the utility of the signalling convention, it raises a critical question: namely, how many Batesians does it take to destabilize the ring entirely?

3.2. Adversarial chase

Systems with conflicting reward structure will exhibit adversarial dynamics, as is observed most clearly in a system comprising non-toxic types and predators, such as systems (0, 1) and (0, 2), which have one and two non-toxic types, respectively, and one predator type but zero toxic types. In these systems, we observe an antagonistic chase: the non-toxic types attempt signal locking; however, the predator repels any such signal convention by rapidly mutating and moving its avoidance region in response (electronic supplementary material, figures S8 and S10).

Initialized in ‘babbling’, the non-toxic type seeks to mutate and rapidly adapt a strategy that predators instinctively avoid. Predators repel selective forces in this direction by attenuating replication of easily duped avoidance strategies. Should a non-toxic mutant dupe all predators into avoidance, predator mutation will eventually ensure a return to predation. Evolutionary events, which could offer a common signalling convention, are no longer sought by all types (as they are when a Müllerian ring forms), so they are no longer the flash-points for rapid adaptation in both the predator and prey class. Rather, in these cases what is good for one class is bad for the other; thus, setting the stage for the antagonistic chase.

Our simulations, as presented here, give the appearance that the predator has greater control, repelling the separating equilibrium (where non-toxic types would thrive) in favour of the Babbling equilibrium (where the predator minimizes loss); however, this notion of which type has greater control will depend on key model parameters. Note that the decision function has an important geometric aspect: when τ = 0.2 the avoidance region has far less volume than the predation region; when τ = 1.8 we observe that the non-toxic type controls the equilibrium by repelling babbling while maintaining the separating equilibrium.

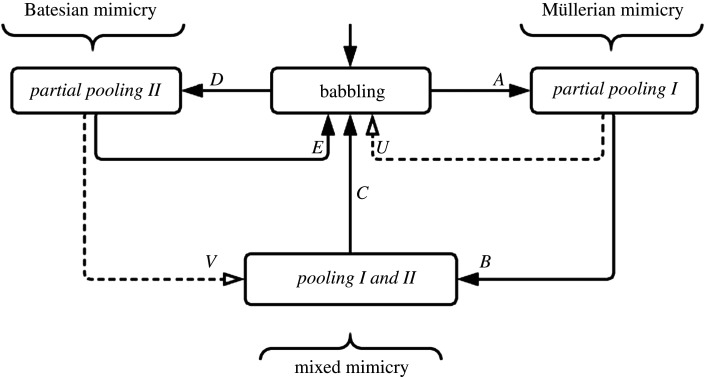

3.3. Mixed-mode behaviours

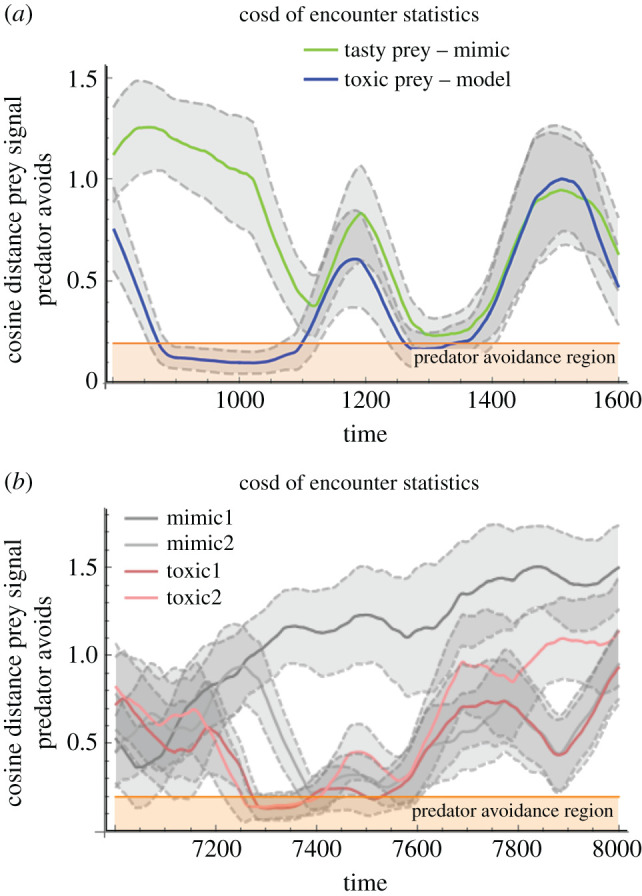

In mixed-mode systems with both mutualistic and conflicting reward structures (systems (n, m) are ensembles with n toxic, m non-toxic and one predator type) a novel and important behaviour arises. Epochs of familiar behaviours are observed, such as ring formation via signal locking between predator and toxic types (as before in (n, 0) systems), as well as adversarial chase between non-toxic type and predator (as before in (0,m) systems). But, critically, we observe a new dynamic behaviour: namely, the destabilizing effects of Batesian (non-toxic) invasions on previously formed rings. Since rings emerge from babbling (as in the (n, 0) component), and Batesian invasion collapses rings back to babbling, the system cycles and we observe an oscillator (figure 5) whose main cycle is succinctly understood as transitional, from one game equilibrium to another: ordered as babbling, partial pooling, pooling and back to babbling. We illustrate the equilibrium transition graph (in figure 6) for the simplest case (i.e. (1, 1) having one toxic, one non-toxic and one predator type2) exhibiting the novel cycle. We generalize the discussion to other more complex scenarios where mimicry rings form.

Figure 5.

Mixed-mimicry modes are shown to oscillate. A ring is established frequently but invaded by the non-toxic type which destabilizes the ring and precipitates the abandonment of the partial pooling in favour of babbling. When the ring is invaded the partial pooling equilibrium transitions to a pooling equilibrium, rendering the receiver’s discerning strategy into one that is too timid. In (a), a population of one toxic, one non-toxic and one predatory type evolve signalling strategies over time. In (b), a more complex scenario with a population of two toxic types, two non-toxic types and one predator is shown. For every generation, a set of encounters results in a cosine distance measure between the predator’s avoidance feature and the signalling organism. Plotted on the vertical axis is the average (and variation band) of cosine distance measures between predator and toxic type (blue) and between predator and nourishing type (green). The horizontal shaded region (orange) represents the avoidance region, where encounters will lead to avoidance rather than predation. Since avoidance is mutually beneficial to toxic type and predator we observe epochs (measured in hundreds of generations) where the partial pooling equilibrium is stable and separates toxic from non-toxic types. The stability of the signalling system appears to be disrupted and destabilized when non-toxic types signal within the avoidance region.

Figure 6.

Oscillation in mimicry modes as described by transitions in evolutionary game equilibria. Using the game outlined in figure 3 with predator, toxic type and non-toxic type initialized in a babbling equilibrium. Each type leverages mutant and diverse strategies to search signal space. When toxic type and predator are first to lock signals, transition A is compelled by the utility-seeking behaviour of both, causing a transition to partial pooling I; this is where predator and toxic type establish a signalling convention that is mutually beneficial and increases their utility. We observe that, from partial pooling I, organisms from non-toxic type will eventually invade, leading to transition B, which yields a higher utility for a mimic at the expense of the receiver (predator). This transition leads to a mixed mode where cooperative and Batesian mimicry strategies are simultaneously expressed and the signalling system is in pooling equilibrium. Note that the predator has lost average utility from its prior state in partial pooling I and could exploit diverse or mutant strategies to return to a babbling state (transition C) if the first of such mutants stands to gain utility, as would clearly be the case when the benefits of consuming a non-toxic type outweigh the risk of consuming a toxic type. It is also possible that from the babbling state the non-toxic type first coalesces to the predator’s avoidance feature, as identified by transition D, leading to partial pooling II. This outcome is purely deceptive Batesian and will lead to gains for nourishing type and a loss for the predator. Since the predator can leverage diverse or mutant strategies which forget the avoidance feature, transition E is clearly possible and is preferred as a unitary move by the predator species.

Initialized to babbling, toxic and predator types (attracted by common interest) seek signal locking and the formation of a ring (Müllerian mode mimicry); a non-toxic type seeks to exploit any avoidance cues which a predator instinctively employs (Batesian mode). Once a ring forms, enlistment of additional toxic types strengthens the ring by reinforcing the predator’s reward for its avoidance behaviour. As non-toxic (Batesian invaders) types invade the ring, the predator’s reward is reduced. The predator’s utility is thus the critical ballast for the ring’s stability: while it may tolerate a certain number of Batesian invaders, there may be a threshold at which the babbling equilibrium is preferred. The transition occurs when a mutant predator modifies avoidance and breaks out of the existing partial pooling equilibrium (or forgets the inherited avoidance habit), thus putting non-toxic mimics back in play for predation. Because this approach increases metabolic rewards above that of the fully timid strategy held by the majority, the mutant strategy will quickly replicate among the predators.

Our result with mixed-mode mimicry is consistent with other available evidence: namely, that models will diverge from mimics in a process of antagonistic coevolution [28]. Theoretical considerations have indicated a ‘coevolutionary chase’ with a continual process of model divergence and mimic catch-up [29,30]. Studies that monitor changes over time are scarce, and difficult experimentally—given the time scales necessary to observe multiple cycles of divergence and catch-up. More readily available examples might be found in human society; for example, currency counterfeiting has to be countered by the periodic introduction of new markings into banknotes. Our simulation study is simple and restricted to understanding the basic dynamics of one ring (anchored by a predator with limited avoidance parameters); however, it connects in informative ways to studies that employ frequency dependence or consider multiple rings. For example, frequency-dependent selection means that the effectiveness of the mimicry signal is reduced at high frequency, which could break the oscillation. While simulations have shown that invasion by Batesian mimics promotes convergence between rings owing to the promotion of signal divergence, which means that one ring might become similar to a second ring [31], generally their effects have been little studied. Still, the criticality of the predator's reward for ring stability indicates from within larger networks the type of mean-field game which arises from the types of games described here. In the larger networks organisms join as many rings as possible for protection, while predators dealing with rings cluttered with various levels of deception make critical ring-breaking decisions (figures 5 and 6).

3.4. Molecular mimicry, the origin of life and cellularization

Molecular mimicry can be more fully understood within a signalling games framework [5]. The gene for an RNA or a protein macro-molecule can be considered as the sender, while the signal consists of the three-dimensional conformation of the expressed gene product. The receiver is the macro-molecule, which specifically interacts with the signal macro-molecule, typically a protein, but could also be an RNA or DNA molecule. An action results from the binding of the receiver macro-molecule with the signal macro-molecule, which results in an increase in utility (fitness) for both sender and receiver, if there is perfect common interest between the two. The action might be an enzymatic reaction or conformational change by the receiver macro-molecule. The binding (substrate) specificity of the receiver macro-molecule is analogous to organismal receiver discrimination [32].

This model of a bio-molecular signalling game implies that the first signalling games were played between bio-molecules in the earliest life forms, once the bio-molecules were large enough to exert specificity [5,33,34]. This in turn implies that meaning first arose from the primordial soup, as the first signal was strategically sent between a pair of replicating macro-molecules. However, immediately ‘meaning’ first arose, it then became susceptible to deception, effectively the original sin. mRNAs and tRNAs may be regarded as Müllerian co-mimics, given that they typically have perfect common interest with each other. All mRNA 5’ leaders and 3’ polyA tails may be regarded as signal co-mimics of each other, the receiver being the translation initiation apparatus. In this sense, the protein-coding portion of the genome may be regarded as an instantiation of Müllerian mimicry.

Likewise, all cellular tRNAs are signal co-mimics of each other, with the receiver the A-site of the ribosome. There are numerous additional tRNA-like co-mimics that are normal parts of the cell These include the yeast aspartyl-tRNA synthetase mRNA, Escherichia coli threonyl-tRNA synthetase mRNA, E.coli methionyl-tRNA synthetase mRNA (which all possess tRNA mimics on the mRNA leader [35–37]), the Salmonella typhimurium his operon [38], the mitochondrial group I intron catalytic core [39] and ribosomal tRNA mimics (which are tRNA-like proteins that interact with the ribosome [40]). Several tRNA-like proteins interact with the ribosome in the A-site. These molecules display Müllerian-type mimicry, involving a cooperative relationship between the different tRNA-shaped proteins and the ribosome, in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes (figure 1b,c). These comprise molecular Müllerian mimicry rings, conferring a direct reward to the receiver, as opposed to the avoidance of harm in classical aposematic mimicry rings [41] (aposematism might be a special case of mimicry, with a pooled signal contrasting with the absence of a signal. In rewarding mimicry one might see a pooled signal contrasting with other signals (as in the wine bottles).

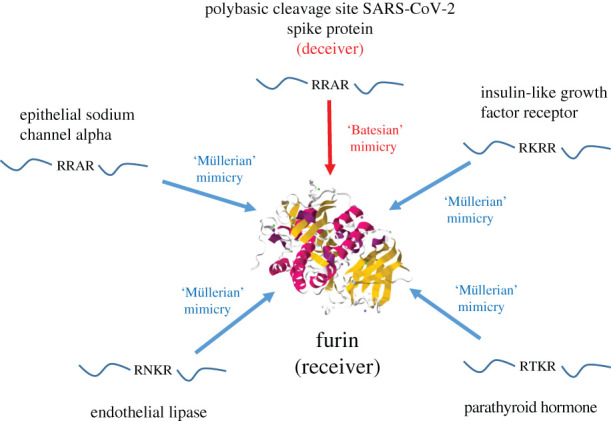

By contrast, Batesian molecular mimicry involves a conflict of interest between sender and receiver genes. Batesian molecular mimics of mRNAs and tRNAs may be termed ‘deceiver’ mRNAs [33] and ‘deceiver’ tRNAs [5], respectively. Virus mRNAs are all effectively deceiver mRNAs, tricking the host translational apparatus into translating them regardless. Viruses also harbour a variety of ‘deceiver’ tRNAs, which trick the host translational apparatus by mimicking normal cellular tRNAs [5,41,42]. The fitness of the virus is enhanced, but at a cost to the host (an example is provided in figure 1c). Numerous further parallels between molecular and organismal mimicry are discussed in electronic supplementary material, §§3 and 4. The relevance of the signalling games' perspective of molecular mimicry to the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, and the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic, has not escaped the authors. A key example is illustrated in figure 7.

Figure 7.

Invasion of a Müllerian molecular mimicry ring by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein PCS. PCSs are found in an array of host proteins and are cleaved by endogenous proteases, including furin [43]. The PCSs act as cooperative Müllerian co-mimics, forming a molecular mimicry ring; four examples are displayed [44–47]. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein also contains a PCS, which leads to cleavage of the spike protein by endogenous proteases including furin, increasing the infectivity of the virus, and has directly contributed to the devastating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic [43]. The viral PCS deceives furin into cleaving it, constituting a Batesian mimic, which has invaded the PCS Müllerian molecular mimicry ring. This deceptive strategy is difficult to counteract pharmaceutically because drugs that inhibit proteases from cleaving the viral PCS will also inhibit the cleavage of endogenous PCSs that comprise the mimicry ring. The endogenous PCS signal is composed of a short sequence, which is a cheap signal, meaning that it is easy to mimic. The large size of the mimicry ring means that the endogenous PCS signal is difficult to change, given the number of individual PCSs in the endogenous proteins, and so an adversarial chase between endogenous and viral PCS signals is perhaps unlikely. These features may explain why the PCS is so commonly used by a wide range of microbial pathogens [48]. The ease of mimicry may also explain why it can arise in cancers [48], which, despite using a range of deceptive strategies, do not appear to make much use of Batesian mimicry, which can be costly to evolve. The structure of furin was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (5JXG).

In early life, cellularization would have led to synchronization of sender and receiver gene replication, thus inducing common interest, and resulting in the alignment of their respective utilities. This process would have acted to promote cooperation, including Müllerian-type molecular mimicry. By contrast, Batesian-type molecular mimicry would have been disincentivized by the promotion of common interest. Conflicts of interest may still arise within the cell from selfish elements (i.e. insider threats in an intelligence organization such as MI5 or NSA), from other forms of genetic conflict and from external pathogens: this predicts the occurrence of molecular deception [5], which includes Batesian-type molecular mimicry.

3.5. The role of molecular mimicry in COVID-19

The SARS-CoV-2 virus makes multiple uses of molecular mimicry in its efforts to exploit its human host, beginning from its emergence via a zoonotic event from an earlier host, bat, which tolerates the virus in a quasi-Batesian mimicry ring. The events between the zoonosis from bat to the present human host, and its emergence as a pandemic, although unclear, were probably influenced by the virus’s mimicry strategies. There follows a sample of some of the mimicry strategies that SARS-CoV-2 uses. (i) Replication organelles, inside which the virus replicates [49], are a form of camouflage. (ii) The addition of a cap-like structure onto the 5’ end of viral mRNA by SARS-CoV-2 nsp16 [50] produces virus deceiver mRNAs, as discussed in §3.4. These are Batesian mimics of normal cellular mRNAs, which constitute a Müllerian mimicry ring, and are invaded by the viral deceiver mRNAs.

Furthermore, (iii) glycosylation of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein shields it from immune system surveillance [51]. Host glycans are acquired in the endoplasmic reticulum by several RNA viruses, and so glycosylated viral proteins are regarded as self by the immune system [52], while shielding the protein epitopes from recognition; this deceptive strategy constitutes a mix of Batesian and cue mimicry. (iv) An elevated Ka/Ks in exposed regions of the spike protein is an indication of ancient adversarial chases between the virus and the immune system of the mammalian host(s). This may be understood as an oscillation between recognition—evasion—recognition—evasion and so on, equivalent to the adversarial chase (0,1) simulation presented earlier in the Results section. Finally, (v) the polybasic cleavage site (PCS) present in the spike protein represents a Batesian molecular mimic, and plays a crucial role in the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic; this is described in more detail in figure 7.

The most potent weapon in the human biotechnology armamentarium against the Batesian deception of the virus is even cheaper molecular mimicry of the pathogen by vaccines. Vaccines may mimic different parts of a virus: its surface proteins, DNA or RNA. After administration of a vaccine, it deceives the human immune system into sensing that it is being attacked by a viable virus. This deception is costly to the vaccinated subject in the short term, as the vaccine itself does not bear any threat. However, the immune system retains a memory and so is pre-prepared for a (likely) future encounter with the real virus.

A virus may circumvent vaccination via antigenic drift, whereby virus epitopes mutate over time leading to novel immunogenic properties. This process will reduce the effectiveness of the vaccine and is commonly encountered with influenza vaccines, which must be generated on a yearly basis [53]. The response by the biomedical community to this is to develop a new vaccine, which is a more accurate mimic of the newly evolved virus. Thus, a coevolutionary chase is joined, between vaccine and virus, that bears similarity to the oscillatory effect displayed in figure 5.

Better knowledge of the deceptive strategies of SARS-CoV-2 will help to inform vaccine design. Particularly, a better understanding of decoy (non-neutralizing) epitopes will help in the rational design of vaccines using peptides. Decoy epitopes result in the production of non-neutralizing antibodies by the immune system, and can lead to antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). This phenomenon occurs when decoy epitopes bind to non-neutralizing antibodies which facilitate the entry of the virus into the host cell [54]. Decoy epitopes result in a reduction of efficiency of vaccines by diverting immune resources away from the recognition of neutralizing epitopes [55], and by potentially causing ADE [54].

The prediction of decoy epitopes from virus protein sequences has been little studied. Understanding the evolutionary dynamics of decoy epitopes may allow their more precise identification. A key question to be answered is whether they are adaptive; if so then they may be better understood as Batesian mimics of neutralizing epitopes. In this scenario, the decoy epitope is deliberately exposed to the immune system, rather than being shielded by glycans, in order to divert antibodies from the neutralizing epitopes. Identification of decoy epitopes will allow the design of vaccines that circumvent such epitopes, thus sharpening the immune response to the vaccine.

Anti-viral drugs are also typically molecular mimics. For example, remdesivir is a molecular mimic of ribonucleotides. The drug represents a deceptive molecular signal, luring the virus replicase into binding to it. The response of the virus over time is to develop drug resistance, by ceasing to bind the drug; it has ‘learned’ that the drug is deceptive.

The virus may develop resistance more slowly to some drugs than to others. We take as our inspiration the model of PCS mimicry displayed in figure 7, where the Müllerian molecular mimicry ring of PCS signals present in endogenous proteins constrains the signal sequence from diverging, in response to PCS mimicry by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Likewise, if an anti-viral drug invades a molecular mimicry ring formed by the viral protein and its canonical substrates, then the viral protein may not easily change its specificity and develop drug resistance. This stability sustains because it is constrained by the need to bind several canonical substrates, which are similar in structure.

3.6. Cellularization-like processes and the evolution of cooperation

Analogous processes to cellularization, which involve the alignment of utilities, thus promoting cooperation, abound at higher levels of biological organization (table 2); elegant generalizations to self-assembled Nash networks that capture similar intuitions appear in [56]. In human society, religious denominations, tribalism and the formation of trading blocs may also be considered forms of cellularization (table 3). The reader may note the subtle differences in the mimicry structures at different scales and the variability in mechanisms, evolution and stability exhibited in one scale but not others; see tables 1 and 2. We wish to address these finer distinctions and related epistemological issues in future work—with a particular focus on artificial intelligence (AI) and social media.

While such cellularizations are relatively stable, nonetheless, they can be sporadically destabilized by environmental changes that alter relationships among players (e.g. trust as measured by correlation of encounters), such as social distancing to mitigate a viral pandemic spread. The resulting cascade of disruptions among employer–employee relationships gives rise to a Shumpeter’s gale, a creative destruction dynamic analogous to a coevolutionary chase, resulting in recellularizations that may have to be coordinated carefully with artificial and temporary shifts in the utility functions (e.g. unemployment benefits, bail-outs, basic incomes, etc.) but may also lead to extensive mimicry. The dynamics of recellularization in the presence of Batesian mimicry may lead to L-, U-, V- or W-shaped economic recoveries and warrant further investigations in the macro-economic contexts.

To break the cycle of constant invasion (W-shaped recovery), we speculate that nature and games must have a mechanism for stabilizing cellularization. This procedure strongly solidifies a tighter alignment bond between utilities of cooperative components and preserves the signalling system while also offering security recourse or a means for its protection, often by costly signalling or increasing the price for mimicry and thus disadvantaging invasive Batesian types.

Also we speculate that the mixed-mode cycle completed by transition A, B, C in figure 6 may afford evolution with a duty cycle. The return to a babbling state can allow retrial of various cooperative mimicry component combinations.

A particularly interesting socio-technological question comes up in the context of social-distancing aspects of pandemic measures and their effects on economic relations—frequently mischaracterized in terms of lives-versus-livelihood trade-offs. Social distancing has led to novel applications of digital communications, automation, artificial intelligence and in silico simulations and poses interesting questions about restructuring dynamics for our macro-socio-economic worlds (e.g. guitar-string model and whether the recovery would be V- or W-shaped). An important question posed in the context is the role likely to be played by the currently available (unexplainable) AI technologies and the ‘pandemonia of imitations’ they may give rise to. Here, a mass of imitations may be used to increase the probability of a successful invasion of a Müllerian mimicry ring.

Especially with the advent of AI and its increasing role in social media, mimicry of intelligent behaviour (e.g. imitation game) in a social context will need to be studied rigorously in the near future (table 3).

Table 3.

Cellularization-like processes at multiple levels. Cellularization-like processes promote cooperation and involve the alignment of utilities. This can occur at different levels of biotic complexity, ranging from biomolecules to whole organisms and then to human society, and ultimately supra-national organizations.

| level | type of cellularization | examples | type of deceptive mimicry it is susceptible to |

|---|---|---|---|

| biomolecular | between the first genetic units of inheritance | the first genes are unknown but interactions between their expression products would have constituted the first biomolecular signalling games. Deceptive signalling would be minimized by common interest, induced by synchronized replication resulting from cellularization | the first genes would have been susceptible to deceptive molecular mimicry |

| protein translation | between mRNAs and the ribosome | ‘deceiver’ tRNAs (’Batesian’ tRNA mimics) and ‘deceiver’ mRNAs (such as virus mRNAs; §3.4) | |

| genomic | between the genes within the genome | synchronized replication of all genes in a genome | selfish elements may replicate at the expense of the host genome; there is evidence that they engage in Batesian molecular mimicry [5] |

| cellular | endosymbiosis | eukaryosis involved the acquisition of a mitochondrion within the proto-eukaryotic cell [57] | intracellular pathogens persist by a variety of evasive mechanisms, including molecular mimicry [58] |

| organismal | eusociality | ant colonies | ant social parasitism often involves deceptive cuticular hydrocarbon signals [59] |

| flocking, herding and swarming | bird flocks | in a mixed species flock, fork-tailed drongos will emit false alarms, causing other species to drop their prey [60] | |

| societal | tribalism | tribal groupings are found all over the world, and appear to be an ancient human behaviour [61] | cooperation between non-kin in tribal societies is susceptible to freeriders, which may be controlled by sanctioning [62] |

| religions | religions, and their sects, down to local groupings such as churches, synagogues and temples | false prophets and some forms of virtue signalling | |

| states | these may be statelets, autonomous regions, nations or federal states | freeloading behaviour via avoidance of paying tax, which often involves deceptive mimicry (tax represents the fiscal contract between citizen and state [63]) | |

| trading blocs | examples include the European Union and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations | counterfeiting (Batesian mimicry) and smuggling (cue mimicry) |

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following for valuable discussion: Inavamsi Enaganti (Department of Computer Science, Courant Institute, NYU), Charles Cantor (College of Engineering, Boston University), Ashley Duits (Red Cross Blood Bank Foundation Curaçao, Willemstad, Curaçao and Curaçao Biomedical & Health Research Institute, Willemstad, Curaçao), J. Kelly Ganjei (Cognate BioServices Inc.), Larry Rudolph (Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab, MIT), Lex van der Ploeg (Yao The Bard LLC) and the RxCovea framework.

Endnotes

Note that for δ < 1 the avoidance region is a cone whose tip is at the origin and centre of rotation at q; if δ = 1 the avoidance region is a half-space whose boundary passes through the origin and is orthogonal to q. The decision function can operate in a symmetric way for both purposes, as the alternative decision function, to target a specific region of signal space for predation, is equivalently represented with δ > 1, which defines the predation region as a cone rotated about −q. The important modelling aspect is that the decision function will determine an action for any organism (of any type) and facilitate evolutionary learning for the inherited parameters; this constraint is intended to represent realistic trade-offs between adaptability, quality and cost in evolving complex decision-making mechanisms.

This population structure closely resembles the classical mimicry scenario with the toxic type as model, non-toxic type as mimic and predator as dupe.

4. Conclusion

Signalling game theory provides an ideal framework for analysing the different kinds of mimicry signalling, while keeping the true sender types private—often unfairly improving the deceivers’ selection advantages. More precisely, signalling games involve an incomplete information setting that results in the transmittal of a strategically chosen signal between two players, from an informed sender to an uninformed receiver, resulting in an action by the receiver. The strategically chosen action by the receiver—based solely on the signal—results in an increase in utility (analogous to organismal fitness), which is distributed to the players. Note that, since the signals need not be honest, the resulting intertwining of players and games should be expected to set up a complex and dynamic evolution of the topology of the signalling network itself. In this paper, we provide the detailed signalling game models and illustrate results showing: how Müllerian rings might emerge and exhibit stability, the effect of Batesian mimics in the population and the behaviour of mixed-mode mimicry. It is hoped that these models make the point that signalling games can be extremely helpful in studying mimicry at all levels of organization—molecules to societies. A timely, albeit strange, example of mimicry illustrates how SARS-CoV-2 spike protein mimics the PCS. PCSs are found in an array of host (humans, bats) proteins and are cleaved by endogenous proteases, including furin. The PCSs act as cooperative co-mimics, forming a molecular mimicry ring; SARS-CoV-2 spike protein also contains a PCS, which leads to cleavage of the spike protein by endogenous proteases including furin, increasing the infectivity of the virus. The viral PCS deceives furin into cleaving it, constituting a Batesian mimic, which has invaded the PCS Müllerian molecular mimicry ring. Such a deceptive strategy may prove difficult to counteract pharmaceutically because drugs that inhibit proteases from cleaving the viral PCS will also inhibit the cleavage of endogenous PCSs that comprise the mimicry ring.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

W.C., S.E.M. and B.M. participated equally in the conception and design of the work as well as in the hypothesis testing using computational models. All authors participated in data analysis and interpretation as well as drafting the article and critical revision of the article. Finally, all authors approve the version to be published.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by an Office of Naval Research grant N0001420WX01716 (to W.C.), a National Cancer Institute Physical Sciences-Oncology Center grant no. U54 CA193313-01 (to B.M.) and a US Army grant W911NF1810427 (to W.C. and B.M.).

References

- 1.Bates HW. 1861. Contributions to an insect fauna of the Amazon valley (Lepidoptera: Heliconidae). Trans. Linnean Soc. 23, 495-566. ( 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1860.tb00146.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zahavi A. 1975. Mate selection—a selection for a handicap. J. Theor. Biol. 53, 205-214. ( 10.1016/0022-5193(75)90111-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spence M. 1973. Job market signaling. Quart. J. Econ. 87, 355-374. ( 10.2307/1882010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller F. 1879. Ituna and Thyridia; a remarkable case of mimicry in butterflies. Trans. Entomol. Soc. Lond. 20, 29. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massey SE, Mishra B. 2018. Origin of biomolecular games: deception and molecular evolution. J. R. Soc. Interface 15, 20180329. ( 10.1098/rsif.2018.0429) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colussi TM, Costantino DA, Hammond JA, Ruehle GM, Nix JC, Kieft JS. 2014. The structural basis of transfer RNA mimicry and conformational plasticity by a viral RNA. Nature 311, 366-369. ( 10.1038/nature13378) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamie GA. 2017. Signals, cues and the nature of mimicry. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20162080. ( 10.1098/rspb.2016.2080) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skyrms B. 1996. Evolution of the social contract. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Book A, Methot T, Gauthier N, Hosker-Field A, Forth A, Quinsey V, Molnar D. 2015. The mask of sanity revisited: psychopathic traits and affective mimicry. Evol. Psych. Sci. 1, 91-102. ( 10.1007/s40806-015-0012-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bull C, den Brok M, Adema G. 2014. Sweet escape: sialic acids in tumor immune evasion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1846, 238-246. ( 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.07.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrido F, Aptsiauri N, Doorduijn E, Lora A, van Hall T. 2016. The urgent need to recover MHC class I in cancers for effective immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 39, 44-51. ( 10.1016/j.coi.2015.12.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornelissen L, Van Vliet S. 2016. A bitter sweet symphony: immune responses to altered O-glycan epitopes in cancer. Biomolecules 6, E26. ( 10.3390/biom6020026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caldwell A, Siddle H. 2017. The role of MHC genes in contagious cancer: the story of Tasmanian devils. Immunogenetics 69, 537-545. ( 10.1007/s00251-017-0991-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mozur P. 2019. In Hong Kong protests, faces become weapons. The New York Times, 26 July 2019. See https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/26/technology/hong-kong-protests-facial-recognition-surveillance.html.

- 15.Martins M, Puckett T, Lockwood R, Swaddle J, Hunt G. 2018. High male sexual investment as a driver of extinction in fossil ostracods. Nature 556, 366-369. ( 10.1038/s41586-018-0020-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veblen T. 1899. The theory of the leisure class: an economic study in the evolution of institutions. New York, NY: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klasios J. 2013. Cognitive traits as sexually selected fitness indicators. Rev. General Pscychol. 17, 428-442. ( 10.1037/a0034391) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huttegger S, Skyrms B, Tarres P, Wagner E. 2014. Some dynamics of signaling games. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10873-10880. ( 10.1073/pnas.1400838111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokkonen M, Lindstedt C. 2016. The evolutionary ecology of deception. Biol. Rev. 91, 1020-1035. ( 10.1111/brv.12208) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor P, Jonker L. 1978. Evolutionary stable strategies and game dynamics. Math. Biosci. 40, 145-156. ( 10.1016/0025-5564(78)90077-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis D. 1969. Convention: a philosophical study. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergstrom CT, Szamado S, Lachmann M. 2002. Separating equilibria in continuous signalling games. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 357, 1595-1606. ( 10.1098/rstb.2002.1068) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrell J, Rabin M. 1996. Cheap talk. J. Econ. Perspect. 10, 103-118. ( 10.1257/jep.10.3.103) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huttegger S, Skyrms B, Smead R, Zollman K. 2010. Evolutionary dynamics of Lewis signaling games: signaling systems vs. partial pooling. Synthese 172, 177-191. ( 10.1007/s11229-009-9477-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shapley LS. 1969. A value for n-person games. In The Shapley value. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- 26.Pfennig D, Harcombe W, Pfennig K. 2001. Frequency-dependent Batesian mimicry. Nature 410, 323. ( 10.1038/35066628) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finkbeiner S, Salazar P, Nogales S, Rush C, Briscoe A, Hill R, Kronforst M, Willmott K, Mullen S. 2018. Frequency dependence shapes the adaptive landscape of imperfect Batesian mimicry. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 1876. ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.2786) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilner R, Langmore N. 2011. Cuckoos versus hosts in insects and birds: adaptations, counter-adaptations and outcomes. Biol. Rev. 86, 836-852. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00173.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gavrilets S, Hastings A. 1998. Coevolutionary chase in two-species systems with applications to mimicry. J. Theor. Biol. 191, 415-427. ( 10.1006/jtbi.1997.0615) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joron M, Mallet J. 1998. Diversity in mimicry: paradox or paradigm? Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 461-466. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01483-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franks D, Noble J. 2004. Batesian mimics influence mimicry ring evolution. Proc. Biol. Sci. 271, 191-196. ( 10.1098/rspb.2003.2582) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guilford T, Dawkins MS. 1991. Receiver psychology and the evolution of animal signals. Anim. Behav. 42, 1-14. ( 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80600-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jee J, Sundstrom A, Massey SE, Mishra B. 2013. What can information-asymmetric games tell us about the context of Crick’s ’frozen accident’?. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20130614. ( 10.1098/rsif.2013.0614) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janwa H, Massey S, Velev J, Mishra B. 2019. On the origin of biomolecular networks. Front. Genet. 10, 240. ( 10.3389/fgene.2019.00240) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryckelynck M, Giege R, Frugier M. 2005. tRNAs and tRNA mimics as cornerstones of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase regulations. Biochimie 87, 835-845. ( 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.02.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romby P, Brunel C, Caillet J, Springer M, Grunberg-Manago M, Westhof E, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B. 1992. Molecular mimicry in translational control of E. coli threonyl-tRNA synthetase gene. Competitive inhibition in tRNA aminoacylation and operator-repressor recognition switch using tRNA identity rules. Nucl. Acids Res. 20, 5633-5640. ( 10.1093/nar/20.21.5633) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dardel F, Panvert M, Fayat G. 1990. Transcription and regulation of expression of the Escherichia coli methionyl-tRNA synthetase gene. Mol. Gen. Genet. 223, 121-133. ( 10.1007/BF00315804) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ames BN, Tsang TH, Buck M, Christman MF. 1983. The leader mRNA of the histidine attenuator region resembles tRNAHis: possible general regulatory implications. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 80, 5240-5242. ( 10.1073/pnas.80.17.5240) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carprara MG, Lehnert V, Lambowitz A, Westhof E. 1996. A tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase recognizes a conserved tRNA-like structural motif in the group I intron catalytic core. Cell 87, 1135-1145. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81807-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katz A, Elgamal S, Rajkovij A, Ibba M. 2016. Non-canonical roles of tRNAs and tRNA mimics in bacterial cell biology. Mol. Microbiol. 101, 545-558. ( 10.1111/mmi.13419) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherratt TN. 2008. The evolution of Müllerian mimicry. Naturwissenschaften 95, 681-695. ( 10.1007/s00114-008-0403-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butcher SE, Jan E. 2016. tRNA-mimicry in IRES-mediated translation and recoding. RNA Biol. 13, 1068-1074. ( 10.1080/15476286.2016.1219833) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shang J, Wan Y, Luo C, Ye G, Geng Q, Auerbach A, Li F. 2020. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 11 727-11 734. ( 10.1073/pnas.2003138117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anand P, Puranik A, Aravamudan M, Venkatakrishnan A, Soundararajan V. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 selectively mimics a cleavable peptide of human ENaC in a strategic hijack of host proteolytic machinery. eLife 9, e58603. ( 10.7554/eLife.58603) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gauster M, Hrzenjak A, Schick K, Frank S. 2005. Endothelial lipase is inactivated upon cleavage by the members of the proprotein convertase family. J. Lipid Res. 46, 977-987. ( 10.1194/jlr.M400500-JLR200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hendy G, Bennett H, Gibbs B, Lazure C, Day R, Seidah N. 1995. Proparathyroid hormone is preferentially cleaved to parathyroid hormone by the prohormone convertase furin. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 9517-9525. ( 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9517) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lehmann M, Andre F, Bellan C, Remacle-Bonnet M, Garrouste F, Parat F, Lissitsky J-C, Marvaldi J, Pommier G. 1998. Deficient processing and activity of type I insulin-like growth factor receptor in the furin-deficient LoVo-C5 cells. Endocrinology 139, 3763-3771. ( 10.1210/endo.139.9.6184) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Braun E, Sauter D. 2019. Furin-mediated protein processing in infectious diseases and cancer. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 8, e1073. ( 10.1002/cti2.1073) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snijder E, Limpens R, de Wilde A, de Jong A, Zevenhoven-Dobbe J, Maier H, Faas F, Koster A, Barcena M. 2020. A unifying structural and functional model of the coronavirus replication organelle: tracking down RNA synthesis. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000715. ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000715) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viswanathan T, Arya S, Chan S-H, Qi S, Dai N, Hromas R, Park OF, Martinez-Sobrido J-GL, Gupta Y. 2020. Structural basis of RNA cap modification by SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. Nat. Commun. 11, 3718. ( 10.1038/s41467-020-17496-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watanabe Y, Allen J, Wrapp D, McLellan J, Crispin M. 2020. Site-specific glycan analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Science 369, 330-333. ( 10.1101/2020.03.26.010322) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raman R, Tharakaraman K, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. 2016. Glycan-protein interactions in viral pathogenesis. Curr. Opin Struct. Biol. 40, 153-162. ( 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.10.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boni M. 2009. Vaccination and antigenic drift in influenza. Vaccine 26(Suppl. 3), C8-C14. ( 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iwasaki A, Yang Y. 2020. The potential danger of suboptimal antibody responses in COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 339-341. ( 10.1038/s41577-020-0321-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jin J, Park C, Cho S-H, Chung J. 2018. The level of decoy epitope in PCV2 vaccine affects the neutralizing activity of sera in the immunized animals. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 469, 846-851. ( 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.01.141) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barrett J, Skyrms B. 2017. Self-assembling games. Br. J. Phil. Sci. 68, 328-353. ( 10.1093/bjps/axv043) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martin WF, Garg S, Zimorski V. 2015. Endosymbiotic theories for eukaryote origin. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20140330. ( 10.1098/rstb.2014.0330) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Unterholzner L, Almine J. 2019. Camouflage and interception: how pathogens evade detection by intracellular nucleic acid sensors. Immunology 156, 217-227. ( 10.1111/imm.13030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buschinger A. 2009. Social parasitism among ants: a review (Hymenoptera: Formidicae). Myrmecol. News 12, 219-235. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Flower T. 2011. Fork-tailed drongos use deceptive mimicked alarm calls to steal food. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 1548-1555. ( 10.1098/rspb.2010.1932) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brooks A et al. 2018. Long-distance stone transport and pigment use in the earliest Middle Stone Age. Science 360, 90-94. ( 10.1126/science.aao2646) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boyd R, Gintis H, Bowles S. 2010. Coordinated punishment of defectors sustains cooperation and can proliferate when rare. Science 328, 617-620. ( 10.1126/science.1183665) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Timmons J. 2005. The fiscal contract: states, taxes and public services. World Politics 57, 530-567. ( 10.1353/wp.2006.0015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data