Abstract

Social learning represents a high-level complex process to acquire information about the environment, which is increasingly reported in invertebrates. The animal–robot interaction paradigm turned out to be an encouraging strategy to unveil social learning in vertebrates, but it has not been fully exploited in invertebrates. In this study, Lucilia sericata adults were induced to observe bio-robotic conspecific and predator demonstrators to reproduce different flower foraging choices. Can a fly manage two flows of social information with opposite valence? Herein, we attempt a reply. The selection process of L. sericata was affected by social information provided through different bio-robotic demonstrators, by avoiding coloured discs previously visited by a bio-robotic predator and preferring coloured discs previously visited by a bio-robotic conspecific. When both bio-robotic demonstrators visited the same disc, the latency duration increased and the flies significantly tended to avoid this disc. This indicates the complex risk–benefit evaluation process carried out by L. sericata during the acquisition of such social information. Overall, this article provides a unique perspective on the behavioural ecology of social learning in non-social insects; it also highlights the high potential of the animal–robot interaction approach for unveiling the full spectrum of invertebrates' abilities in using social information.

Keywords: animal–robot interaction, biohybrid systems, cognition, ethorobotics, insect, social learning

1. Introduction

The insect nervous system includes a low number of neurons forming neural circuits that exhibit sophisticated architectures [1–3]. These neural circuits, although simple in appearance, enable complex and effective capabilities previously associated with a restricted number of vertebrate species [4–7]. It has been suggested that, similar to computing machines, where the technology inside and not the size of the device is important, also for brains the crucial factor is represented by neural circuit architectures, and not just by the number of neurons [2,8]. This makes insects valuable models for investigating higher order information processes, as well as for formulating bioinspired mathematical models of interest for developing autonomous systems.

Social learning (i.e. obtaining information by observing other animals and/or their products) represents a high-level complex process [9–13], which has recently been described in several insect species [9,14]. Acquiring information about the environment through individual exploration is costly, requiring time and energy. It also leads to some risks, such as dangerous encounters with predators. In this scenario, social learning allows animals to acquire adaptive information by avoiding the drawbacks of individual exploration [15].

Eusocial Hymenoptera have been largely selected in social learning research, as their social features are characterized by prolonged conspecific interaction and overlapping generations, promoting social learning evolutionary processes [9,15–18]. However, recent findings have reported social learning even in solitary insect species, such as the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster Meigen (Diptera: Drosophilidae) [19–22] and the wood cricket Nemobius sylvestris Bosc (Orthoptera: Trigonidiidae) [23]. Overall, how invertebrates can exploit social information to make decisions about foraging, predation and mate choice has been widely documented [19,23,24]. In addition, although research on social learning has been mainly focused on interactions between conspecifics, it should be noted that social information can be transferred across species [9,25]. In this framework, a challenging and fascinating question is: can an insect manage two flows of social information—one produced by conspecifics and one produced by heterospecifics—conflicting each other?

The green bottle fly Lucilia sericata (Meigen) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) is an insect species of significant medical and veterinary importance, causing myiasis in humans, livestock, pets and wildlife, and acting as a vector of various pathogens [26–28]. L. sericata represents a worthy model organism, since it occupies a rather wide array of environmental niches [29,30], carrying out its foraging and reproductive activities in different environmental scenarios shared with conspecifics and heterospecifics [31–33]. Interestingly, this fly is mass-reared and commercialized by several bio-factories for its excellent pollination activity on several plant species, with special reference to Apiaceae [30,34].

In the present research, observational conditioning produced by bio-robotic demonstrators enabled us to reproduce different flower foraging choices. This biohybrid approach, known as ethorobotics [35,36], represents a context of bio-robotics interfacing animal behavioural ecology and robotics to manipulate intraspecific and interspecific interactions through a standardized and adaptable engineered method, ensuring reproducibility and paving the way to unexplored scientific and technological opportunities [37–45]. It is noteworthy that moving dummies crucially affected observational conditioning in bumblebees, as they were more biomimetic, and moving demonstrators boosted detectability, helping to direct attention to a coloured disc [24]. Thus, more sophisticated bio-robotic agents may play a relevant role in this research field.

Herein, L. sericata adults were allowed to observe bio-robotic conspecific demonstrators visiting flowers with a given colour, and ignoring an alternative colour. Furthermore, L. sericata flies were induced to observe bio-robotic predator demonstrators visiting the same colour of flowers selected by conspecific demonstrators. Finally, L. sericata flies had to solve the dilemma of choosing or avoiding the flower visited by the conspecific and at the same time by the predator, weighing potential risks and benefits observed during the social learning process.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethics statements

This research satisfies the guidelines provided by ASAB/ABS [46], as well as Italian laws (D.M. 116192) and EU regulations [47]. No particular permits are required in the country where the experiments were conducted, as they consist in behavioural observations on mass-reared green bottle flies.

2.2. Fly rearing and general information

L. sericata subjects at pupal stage were kindly supplied by Bioplanet® (Cesena, Italy). Pupae were stored in glass containers (diameter 150 mm, length 200 mm). The glass containers were placed individually in polyvinyl chloride cylindrical cages (diameter 400 mm, length 800 mm), waiting for adult emergence. One side of the cage was lined with transparent chiffon fabric (mesh size: 0.05 mm) to ensure aeration. Each cage contained about 100 individuals. Food consisted of a mixture of yeast extract and sucrose at a ratio of 1 : 10 (w/w). Water was provided separately on a cotton wick. During both the rearing phase and the experiments flies were maintained at 21 ± 1°C, 55 ± 5% RH and 16 : 8 (light : dark) photoperiod. During the experimental phase, the light intensity around the arena was about 1000 lux. An observer focally recorded the flies' behaviour during the experiments [28].

2.3. Bio-robotic demonstrators and robotic apparatus

The bio-robotic conspecific demonstrator has a biomimetic morphology inspired by L. sericata body shape and colours (figure 1a). It reproduces the head with two compound eyes, the thorax including three pairs of legs and one pair of wings, as well as the abdomen. The length between the distal end of the head and the abdomen is 9 mm. The bio-robotic predator demonstrator reproduces the head, including two eyes, and partially the neck of a lizard belonging to the family Lacertidae (i.e. Podarcis siculus Rafinesque), including natural predators of Diptera [48,49] (figure 1b). It has a total length of 25 mm and a total width of 11 mm.

Figure 1.

The bio-robotic conspecific demonstrator approached by two Lucilia sericata individuals (a), the bio-robotic predator demonstrator (b) and both the bio-robotic demonstrators visiting the same coloured disc (c).

Both of the bio-robotic demonstrators were designed using SolidWorks (Dassault Systemes, Vélizy Villacoublay, France) and fabricated in a rigid plastic (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene) by rapid prototyping. Subsequently, they were painted with nontoxic pigments to resemble as much as possible the livery of the real animals they represented.

The robotic apparatus consists of a vertical white panel in Plexiglas (400 × 300 mm), presenting blue (L:45.4; a:−26.7; b:−30.9) and yellow (L:82.3; a:−4.7; b:79.8) coloured discs (diameter 40 mm), with 90 mm distance between their circumference centres located on the same horizontal axis. The discs were made from coloured papers whose colour measurements were recorded using standard CIELab colour space coordinates determined using a colorimeter (Nix Pro 2 Color Sensor). The bio-robotic conspecific demonstrator clung to the vertical panel and moved on it by magnetic coupling with a servomotor (H.A.R.D. HS3004) fixed on the opposite face of the panel, to simulate a fly moving or landing on a flower (e.g. a coloured disc) (figure 1c), with a similar velocity (16 mm s−1) to that observed in L. sericata individuals in the rearing cages.

The bio-robotic predator demonstrator was connected through a transparent stick to a crank–rod system activated by a DC motor (Precision Microdrives 225–202). The crank–rod system was mounted below the coloured discs and enabled rectilinear up and down movements of the lizard head with a 50 mm stroke and a 16 mm s−1 velocity, to simulate a lizard exploring a flower [50] (figure 1c). Both bio-robotic demonstrators (i.e. conspecific and predator) were moved at the same velocity to avoid any effects related to different approach speeds to the coloured discs. An additional front white panel (170 × 300 mm) prevented flies from perceiving the crank–rod system and the lizard head during the down-stroke. An external microcontroller (Arduino, Mega 2560) activated and controlled the motion of both of the bio-robotic demonstrators.

2.4. Observational conditioning phase

Green bottle fly adults were isolated in Plexiglas vials (diameter 40 mm, length 7 mm) 24 h before the observational conditioning phase [51,52], without food. Subsequently, they were individually transferred to an observation chamber (50 × 50 × 50 mm) and placed 150 mm from the vertical white panel of the robotic apparatus [24], including the bio-robotic demonstrators and both the coloured discs. The observation chamber was opaque except for the side in front of the robotic apparatus, where a transparent and removable screen enabled the tested fly to observe the robotic stimuli (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Experimental apparatus used during the observational conditioning phase.

The bio-robotic contexts presented to the fly subjects included: (i) a bio-robotic conspecific visiting a coloured disc; (ii) a bio-robotic predator visiting a coloured disc; (iii) both a bio-robotic conspecific and a predator visiting the same coloured disc at the same time; (iv) a bio-robotic conspecific and a bio-robotic predator visiting different coloured discs at the same time; and (v) as control, we included a context where coloured discs were not visited by any bio-robotic demonstrator.

Each fly observed only one of the aforementioned bio-robotic contexts, and it was tested only once in the subsequent preference experiment. Observational conditioning lasted 10 min [24]. For each tested insect, both coloured discs were present and their positions as well as the location of the bio-robotic demonstrators were randomly shifted to avoid any colour-preference effect or directional bias. Both the robotic apparatus and the observation chamber were located in the centre of a white arena (600 × 600 × 600 mm), with a transparent top, to avoid external cues affecting the behaviour of the tested fly [41].

2.5. Preference trials

After the observational conditioning phase (10 min), an opaque partition was used to close the transparent screen of the observation chamber, avoiding visual cues to the trained fly. In the meantime, the bio-robotic demonstrators were removed from the arena, and the positions of the two coloured discs were inverted. Then, the observation chamber was gently opened, enabling the release of the L. sericata fly into the arena, and its choice between the two discs was focally recorded.

The time spent by the fly on coloured discs visited by different bio-robotic demonstrators (i.e. the time each fly spent on the first visited disc) was noted. The recording was stopped when the body of the fly was completely outside of the area of the disc. The latency duration (i.e. the time needed by the fly to move outside the observation chamber once the experiment started) was also recorded. Each adult fly was tested only once. Flies were tested individually. The overall number of flies tested in contexts (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) and (v) was 115, 126, 122, 119 and 116, respectively. Flies that remained in the observation chamber or that flew into the arena without making any choice were disregarded. For each bio-robotic context data from 100 flies were analysed.

2.6. Data analysis

The impact of bio-robotic contexts (i), (ii) and (iii) on the number of L. sericata adults landing on discs visited by different combinations of bio-robotic demonstrators was analysed using a generalized linear model with a binomial error structure and one fixed factor (the bio-robotic context): y = Xß + ɛ, where y is the vector of the observations (i.e. the fly's choice), X is the incidence matrix, ß is the vector of the fixed effect (i.e. the bio-robotic context) and ɛ is the vector of the random residual effects. A value of p = 0.05 was used as the threshold to detect significant differences among values.

A chi-squared test with Yates's correction (p = 0.05) [53] was used to analyse differences in the number of L. sericata flies landing on discs visited by the bio-robotic conspecific and the bio-robotic predator (context (iv)), as well as differences in the number of L. sericata flies landing on yellow and blue discs (colour control, context (v)).

Studying the impact of different bio-robotic contexts on L. sericata behaviour, it was noted that data about the parameters latency duration and time spent by flies on coloured discs were neither normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test, p < 0.05) nor homoscedastic (Levene's test, p < 0.05). Thus, data were analysed relying on non-parametric statistics. The Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test with Bonferroni correction, was used. All data were analysed by using JMP 9 (SAS).

3. Results

Social information provided by different bio-robotic contexts significantly affected the selection process of L. sericata (; p < 0.0001). The number of insects choosing the disc previously visited by the bio-robotic conspecific was higher than the number of flies that selected the disc visited by the bio-robotic predator (; p < 0.0001), showing the ability of L. sericata to exploit social information from both a conspecific and a heterospecific.

The number of insects landing on the disc previously visited by the bio-robotic conspecific was higher than the number of flies that landed on the disc visited by both bio-robotic demonstrators (; p < 0.0001). However, the number of insects that preferred the disc visited by both bio-robotic demonstrators was significantly higher than the number of flies that preferred the disc visited by the bio-robotic predator (; p < 0.0001).

When the bio-robotic conspecific and the bio-robotic predator visited different coloured discs at the same time, L. sericata individuals showed a significant preference for the disc visited by the bio-robotic conspecific, avoiding the disc previously visited by the bio-robotic predator (bio-robotic conspecific versus bio-robotic predator: 94 versus 6; ; p < 0.0001) (table 1). The control trial did not show a significant preference of the flies for a given disc's colour (e.g. yellow versus blue: 42 versus 58; ; p = 0.109) (table 2).

Table 1.

Data analysis for choices about conspecific/predator bio-robotic demonstrators (χ2 test with Yates's correction); the asterisk indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05).

| conspecific | predator | total | χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fly choices (no.) | 94 | 6 | 100 | 77.45 | <0.0001* |

Table 2.

Data analysis for fly choices about the colour control (χ2 test with Yates's correction); ns = not significant (p > 0.05).

| yellow | blue | total | χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fly choices (no.) | 42 | 58 | 100 | 2.57 | 0.109 ns |

The time spent by flies on a coloured disc was significantly longer if the bio-robotic conspecific previously visited it than if the disc was previously visited by the bio-robotic predator (Z = −5.408; p < 0.0001), and if both bio-robotic demonstrators visited the coloured disc (Z = 5.98459; p < 0.0001) (figure 3a). When the bio-robotic conspecific and the bio-robotic predator visited different coloured discs concurrently, the flies spent a significantly longer time on the disc previously visited by the bio-robotic conspecific (Z = −2.321; p = 0.020) (figure 3b). The context where no bio-robotic demonstrators visited the yellow and the blue disc failed to show that the flies spent more time on one of the two discs (Z = −0.246; p = 0.806) (figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Time spent by Lucilia sericata on discs post exposure to the bio-robotic contexts (i), (ii) and (iii) (a), to the bio-robotic context (iv) (b), and to the control context (c) ((a) Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's test with Bonferroni correction; (b,c) Kruskal–Wallis test, p < 0.05). Box plots include a red line indicating the median with its range of dispersion (lower and upper quartiles, as well as outliers), a green line indicating the mean, as well as blue T-bars showing the standard error values. Above each box plot, different letters indicate significant differences.

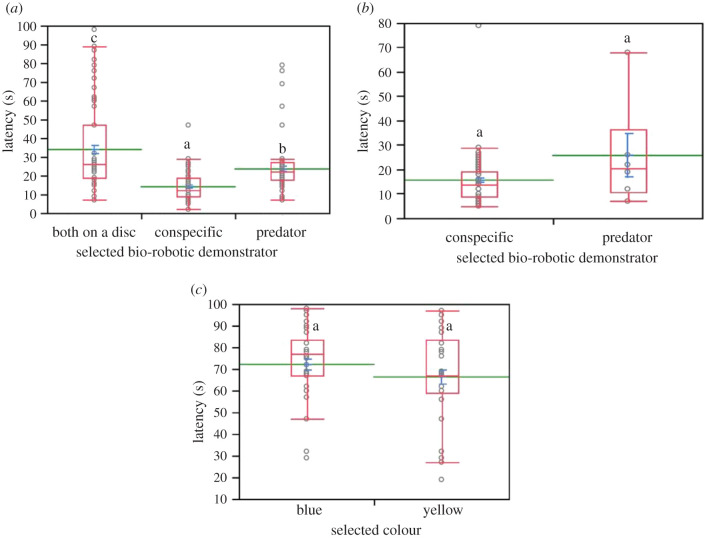

Latency duration was significantly longer when both the bio-robotic conspecific and predator previously visited the same coloured disc than when the bio-robotic conspecific (Z = −9.104; p < 0.0001) and the bio-robotic predator (Z = −2.464; p = 0.041) were exposed (figure 4a). When the bio-robotic predator was exposed, the latency was significantly longer than when the bio-robotic conspecific was present (Z = 6.639; p < 0.0001) (figure 4a). Latency was not influenced when the bio-robotic conspecific and the bio-robotic predator visited different coloured discs concurrently (Z = 1.238; p = 0.216) (figure 4b). Latency duration did not differ between flies selecting the yellow and the blue disc when bio-robotic demonstrators did not visit them (Z = −1.482; p = 0.138) (figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Latency duration in Lucilia sericata post exposure to the bio-robotic contexts (i), (ii) and (iii) (a), to the bio-robotic context (iv) (b), and to the control context (c) ((a) Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's test with Bonferroni correction; (b,c) Kruskal–Wallis test, p < 0.05). Box plots include a red line indicating the median with its range of dispersion (lower and upper quartiles, as well as outliers), a green line indicating the mean, as well as blue T-bars showing the standard error values. Above each box plot, different letters indicate significant differences.

4. Discussion

Social learning research is increasingly orienting towards invertebrate model organisms, owing to the growing amount of evidence of social learning capabilities in these species [9,12,54]. The animal–robot interaction experimental paradigm, located at the interface of animal behaviour and robotics, is providing an encouraging avenue to unveil social learning in vertebrates [44,55].

In this study, we first interfaced an insect species with bio-robotic demonstrators to investigate social learning in relatively simpler organisms. L. sericata flies were able to exploit social information from both conspecifics and heterospecific individuals, preferentially selecting the disc earlier visited by the bio-robotic conspecific and avoiding the disc associated with the bio-robotic predator. It has been reported that eusocial bee pollinators can learn cues related to food sources by observing other conspecific pollinators [56,57]. Although L. sericata adults are excellent pollinators of several plant species [30,34], they are solitary flies, and only their larvae, feeding on decaying meat, display gregarious behaviour as an efficient mechanism to increase temperature and reduce development time [33]. However, L. sericata occupies several environmental niches [29,30], often sharing its habitats with conspecifics and heterospecifics [31–33]. These prolonged interactions may have promoted the evolution of social learning ability in L. sericata. Indeed, social learning also occurs in other Diptera species, which exploit public information to choose mates [19,58], although our results highlight a more sophisticated level of social learning.

A remarkable decision-making process in L. sericata subjects emerged when individuals were exposed to an opposite valence of social information, represented by the disc previously visited by both bio-robotic demonstrators. Herein, the tendency of flies was to avoid this disc, although it was visited by a conspecific in addition to their potential predator. However, the disc visited by only the bio-robotic predator had a major aversion effect. Social information may not always indicate the best option, and often the best pay-off can result from personal information which has been previously acquired [59], such as the recognition of a threat. Furthermore, latency was longer when both bio-robotic demonstrators were moved onto a disc, indicating the complex risk–benefit evaluation process carried out by L. sericata during the acquisition of this social information. A general assumption considers social information to be relatively advantageous, owing to the limited exposure to adverse biotic and abiotic factors as well as to time and energy cost reductions [60,61]. However, outcomes deriving from personal and social information are extremely variable and context-specific [9,62], thus social learning would represent a strategy by which animals evaluate a context and produce adaptive responses.

From a physiological point of view, a predominant role in social learning can be played by the mushroom bodies in the insects' brains [63,64]. First observed in honeybees [65], mushroom bodies consist in lobed neuropils, including long approximately parallel axons that originate from groups of small basophilic cells that are located dorsally in the neuromere in the most anterior section of the central nervous system of insects [66]. Mushroom bodies have long been considered the cellular plinth for associative memory in honeybees [67] and fruit flies [68]. Evidence from Diptera and Hymenoptera demonstrates the involvement of mushroom bodies in olfactory memory [69]. However, it has been reported that the visual experience also has structural effects on mushroom bodies in fruit flies [70]. Considering these facts, we hypothesize that mushroom bodies may also be involved in the social learning process observed in L. sericata during its hybrid interaction with the bio-robotic demonstrators, disclosing an additional potential function of these neural structures. Further studies are urgently needed to verify this hypothesis.

Overall, this study provides a unique perspective on the behavioural ecology of social learning in non-social insects, adding basic information on how fitness can be enhanced through different sources of social information. Furthermore, the animal–robot interaction approach, enabling the manipulation of social information in different ecological contexts, represents a promising examination and control strategy to unveil the full spectrum of invertebrate abilities in using social information.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Francesco Inglese and Dr Marco Miraglia for their kind assistance during the experiments.

Data accessibility

Data are available as electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contribution

Conceptualization was done by D.R.; methodology was done by D.R. and C.S.; formal analysis was done by D.R. and G.B.; investigation was done by D.R. and G.B.; resources were done by C.S.; data curation was done by D.R., G.B. and C.S.; original draft was written by D.R.; review and editing was done by D.R., G.B. and C.S.; supervision was done by D.R. and C.S.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the EU H2020 FETOPEN Project ‘Robocoenosis - ROBOts in cooperation with a bioCOENOSIS' [899520]. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Greenspan RJ, Van Swinderen B. 2004. Cognitive consonance: complex brain functions in the fruit fly and its relatives. Trends Neurosci. 27, 707-711. ( 10.1016/j.tins.2004.10.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chittka L, Niven J. 2009. Are bigger brains better? Curr. Biol. 19, R995-R1008. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avarguès-Weber A, Deisig N, Giurfa M. 2011. Visual cognition in social insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 56, 423-443. ( 10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144855) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoedjes KM, Kruidhof HM, Huigens ME, Dicke M, Vet LE, Smid HM. 2010. Natural variation in learning rate and memory dynamics in parasitoid wasps: opportunities for converging ecology and neuroscience. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 889-897. ( 10.1098/rspb.2010.2199) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinauger C, Buratti L, Lazzari CR. 2011. Learning the way to blood: first evidence of dual olfactory conditioning in a blood-sucking insect, Rhodnius prolixus. I. Appetitive learning. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 3032-3038. ( 10.1242/jeb.056697) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giurfa M. 2013. Cognition with few neurons: higher-order learning in insects. Trends Neurosci. 36, 285-294. ( 10.1016/j.tins.2012.12.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry CJ, Barron AB, Chittka L. 2017. The frontiers of insect cognition. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 16, 111-118. ( 10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.05.011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rojas R. 2006. The Zuse computers. Comput. Res. 37, 8-13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leadbeater E, Chittka L. 2007. Social learning in insects—from miniature brains to consensus building. Curr. Biol. 17, R703-R713. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galef BG Jr, Giraldeau LA. 2001. Social influences on foraging in vertebrates: causal mechanisms and adaptive functions. Anim. Behav. 61, 3-15. ( 10.1006/anbe.2000.1557) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen M, Subiaul F, Galef B, Zentall T, Whiten A. 2012. Social learning in humans and nonhuman animals: theoretical and empirical dissections. J. Comp. Psychol. 126, 109. ( 10.1037/a0027758) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoppitt W, Laland KN. 2013. Social learning: an introduction to mechanisms, methods, and models. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayama S, Krasner E, Zino L, Porfiri M. 2019. Social information and spontaneous emergence of leaders in human groups. J. R. Soc. Interface 16, 20180938. ( 10.1098/rsif.2018.0938) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasenjager MJ, Leadbeater E. 2019. Insect social learning. In Encyclopedia of animal behaviour, pp. 356-364. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grueter C, Leadbeater E. 2014. Insights from insects about adaptive social information use. Trends Ecol. Evol. 29, 177-184. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2014.01.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Frisch K. 1967. The dance language and orientation of bees. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coussi-Korbel S, Fragaszy DM. 1995. On the relation between social dynamics and social learning. Anim. Behav. 50, 1441-1453. ( 10.1016/0003-3472(95)80001-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nowak MA, Tarnita CE, Wilson EO. 2010. The evolution of eusociality. Nature 466, 1057. ( 10.1038/nature09205) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mery F, Varela SA, Danchin É, Blanchet S, Parejo D, Coolen I, Wagner RH. 2009. Public versus personal information for mate copying in an invertebrate. Curr. Biol. 19, 730-734. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.064) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarin S, Dukas R. 2009. Social learning about egg-laying substrates in fruitflies. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 4323-4328. ( 10.1098/rspb.2009.1294) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Battesti M, Moreno C, Joly D, Mery F. 2012. Spread of social information and dynamics of social transmission within Drosophila groups. Curr. Biol. 22, 309-313. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.050) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foucaud J, Philippe AS, Moreno C, Mery F. 2013. A genetic polymorphism affecting reliance on personal versus public information in a spatial learning task in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20130588. ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.0588) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coolen I, Dangles O, Casas J. 2005. Social learning in noncolonial insects? Curr. Biol. 15, 1931-1935. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avarguès-Weber A, Chittka L. 2014. Observational conditioning in flower choice copying by bumblebees (Bombus terrestris): influence of observer distance and demonstrator movement. PLoS ONE 9, e88415. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0088415) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avarguès-Weber A, Dawson EH, Chittka L. 2013. Mechanisms of social learning across species boundaries. J. Zool. 290, 1-11. ( 10.1111/jzo.12015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura T, Cazander G, Rooijakkers SH, Trouw LA, Nibbering PH. 2017. Excretions/secretions from medicinal larvae (Lucilia sericata) inhibit complement activation by two mechanisms. Wound Repair Regen. 25, 41-50. ( 10.1111/wrr.12504) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khater HF, Ali AM, Abouelella GA, Marawan MA, Govindarajan M, Murugan K, Abbas RZ, Vaz NP, Benelli G. 2018. Toxicity and growth inhibition potential of vetiver, cinnamon, and lavender essential oils and their blends against larvae of the sheep blowfly, Lucilia sericata. Int. J. Dermatol. 57, 449-457. ( 10.1111/ijd.13828) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benelli G, Romano D. 2019. Looking for the right mate—what do we really know on the courtship and mating of Lucilia sericata (Meigen)? Acta Trop. 189, 145-153. ( 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.08.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans AC. 1935. Some notes on the biology and physiology of the sheep blowfly, Lucilia sericata, Meig. Bull. Entomol. Res. 26, 115-122. ( 10.1017/S0007485300024949) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Memmott J, Waser NM. 2002. Integration of alien plants into a native flower–pollinator visitation web. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 2395-2399. ( 10.1098/rspb.2002.2174) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brodie BS, Wong WH, VanLaerhoven S, Gries G. 2015. Is aggregated oviposition by the blow flies Lucilia sericata and Phormia regina (Diptera: Calliphoridae) really pheromone-mediated? Insect Sci. 22, 651-660. ( 10.1111/1744-7917.12160) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prinkkilá ML, Hanski I. 1995. Complex competitive interactions in four species of Lucilia blowflies. Ecol. Entomol. 20, 261-272. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2311.1995.tb00456.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boulay J, Devigne C, Gosset D, Charabidze D. 2013. Evidence of active aggregation behaviour in Lucilia sericata larvae and possible implication of a conspecific mark. Anim. Behav. 85, 1191-1197. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.03.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Currah L, Ockendon DJ. 1984. Pollination activity by blowflies and honeybees on onions in breeders' cages. Ann. Appl. Biol. 105, 167-176. ( 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1984.tb02812.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krause J, Winfield AF, Deneubourg JL. 2011. Interactive robots in experimental biology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26, 369-375. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2011.03.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romano D, Donati E, Benelli G, Stefanini C. 2019. A review on animal–robot interaction: from bio-hybrid organisms to mixed societies. Biol. Cybern 113, 201-225. ( 10.1007/s00422-018-0787-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cianca V, Bartolini T, Porfiri M, Macrì S. 2013. A robotics-based behavioural paradigm to measure anxiety-related responses in zebrafish. PLoS ONE 8, e69661. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0069661) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim C, Ruberto T, Phamduy P, Porfiri M. 2018. Closed-loop control of zebrafish behaviour in three dimensions using a robotic stimulus. Sci. Rep. 8, 657. ( 10.1038/s41598-017-19083-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romano D, Stefanini C. 2021. Individual neon tetras (Paracheirodon innesi, Myers) optimise their position in the group depending on external selective contexts: lesson learned from a fish-robot hybrid school. Biosystems Eng. 204, 170-180. ( 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2021.01.021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romano D, Benelli G, Stefanini C. 2017. Escape and surveillance asymmetries in locusts exposed to a Guinea fowl-mimicking robot predator. Sci. Rep. 7, 12825. ( 10.1038/s41598-017-12941-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romano D, Benelli G, Stefanini C. 2019. Encoding lateralization of jump kinematics and eye use in a locust via bio-robotic artifacts. J. Exp. Biol. 222, jeb187427. ( 10.1242/jeb.187427) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romano D, Benelli G, Hwang JS, Stefanini C. 2019. Fighting fish love robots: mate discrimination in males of a highly territorial fish by using female-mimicking robotic cues. Hydrobiologia 833, 185-196. ( 10.1007/s10750-019-3899-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonnet F, Mills R, Szopek M, Schönwetter-Fuchs S, Halloy J, Bogdan S, Correia L, Mondada F, Schmickl T. 2019. Robots mediating interactions between animals for interspecies collective behaviours. Sci. Robotics 4, eaau7897. ( 10.1126/scirobotics.aau7897) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Y, LeMay B, El Khoury R, Clément RJ, Ghirlanda S, Porfiri M. 2019. Can robotic fish help zebrafish learn to open doors? In Bioinspiration, biomimetics, and bioreplication IX, vol. 10965, p. 109650B. Denver, CO: International Society for Optics and Photonics. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polverino G, Karakaya M, Spinello C, Soman VR, Porfiri M. 2019. Behavioural and life-history responses of mosquitofish to biologically inspired and interactive robotic predators. J. R. Soc. Interface 16, 20190359. ( 10.1098/rsif.2019.0359) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.ASAB/ABS. 2014. Guidelines for the treatment of animals in behavioural research and teaching. Anim. Behav. 99, 1-9. ( 10.1016/S0003-3472(14)00451-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.European Commission. 2007. Commission recommendations of 18 June 2007 on guidelines for the accommodation and care of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes. Annex II to European Council Directive 86/609. Document 2007/526/ EC. See http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2007:197:0001:0089:EN:PDF.

- 48.Burke RL, Mercurio RJ. 2002. Food habits of a New York population of Italian wall lizards, Podarcis sicula (Reptilia, Lacertidae). Am. Midland Naturalist 147, 368-376. ( 10.1674/0003-0031(2002)147[0368:FHOANY]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pérez-Cembranos A, León A, Pérez-Mellado V. 2016. Omnivory of an insular lizard: sources of variation in the diet of Podarcis lilfordi (Squamata, Lacertidae). PLoS ONE 11, e0148947. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0148947) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper WE Jr, Pérez-Mellado V, Hawlena D. 2014. Foraging by the omnivorous lizard Podarcis lilfordi: effects of nectivory in an ancestrally insectivorous active forager. J. Herpetol. 48, 203-209. ( 10.1670/11-321) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benelli G, Romano D, Desneux N, Messing RH, Canale A. 2015. Sex differences in fighting-induced hyperaggression in a fly. Anim. Behav. 104, 165-174. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.02.026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romano D, Benelli G, Stefanini C, Desneux N, Ramirez-Romero R, Canale A, Lucchi A. 2018. Behavioural asymmetries in the mealybug parasitoid Anagyrus sp. near pseudococci: does lateralized antennal tapping predict male mating success? J. Pest Sci. 91, 341-349. ( 10.1007/s10340-017-0903-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sokal RK, Rohlf FJ. 1981. Biometry. New York, NY: Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kacsoh BZ, Bozler J, Hodge S, Bosco G. 2019. Neural circuitry of social learning in Drosophila requires multiple inputs to facilitate inter-species communication. Commun. Biol. 2, 1-14. ( 10.1038/s42003-019-0557-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Porfiri M, Yang Y, Clement RJ, Ghirlanda S. 2019. A comparison of individual learning and social learning in zebrafish through an ethorobotics approach. Front. Robotics AI 6, 71. ( 10.3389/frobt.2019.00071) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Worden BD, Papaj DR. 2005. Flower choice copying in bumblebees. Biol. Lett. 1, 504-507. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2005.0368) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leadbeater E, Chittka L. 2007. The dynamics of social learning in an insect model, the bumblebee (Bombus terrestris). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 61, 1789-1796. ( 10.1007/s00265-007-0412-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Loyau A, Blanchet S, Van Laere P, Clobert J, Danchin E. 2012. When not to copy: female fruit flies use sophisticated public information to avoid mated males. Sci. Rep. 2, 768. ( 10.1038/srep00768) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rendell L, et al. 2010. Why copy others? Insights from the social learning strategies tournament. Science 328, 208-213. ( 10.1126/science.1184719) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kameda T, Nakanishi D. 2003. Does social/cultural learning increase human adaptability? Rogers's question revisited. Evol. Hum. Behav. 24, 242-260. ( 10.1016/S1090-5138(03)00015-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Laland KN. 2004. Social learning strategies. Anim. Learn. Behav. 32, 4-14. ( 10.3758/BF03196002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kendal RL, Coolen I. 2009. Adaptive trade-offs in the use of social and personal information. In Cognitive ecology II (eds Dukas R, Ratcliffe JM), pp. 249-271, 2nd edn. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zars T, Fischer M, Schulz R, Heisenberg M. 2000. Localization of a short-term memory in Drosophila. Science 288, 672-675. ( 10.1126/science.288.5466.672) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pascual A, Préat T. 2001. Localization of long-term memory within the Drosophila mushroom body. Science 294, 1115-1117. ( 10.1126/science.1064200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dujardin F. 1850. Mémoire sur le système nerveux des insectes. Ann. Sci. Nat. Zool. 14, 195-206. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Strausfeld NJ, Hansen L, Li Y, Gomez RS, Ito K. 1998. Evolution, discovery, and interpretations of arthropod mushroom bodies. Learn. Mem. 5, 11-37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Menzel R, Erber J, Masuhr TH. 1974. Learning and memory in the honeybee. In Experimental analysis of insect behaviour, pp. 195-217. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heisenberg M, Borst A, Wagner S, Byers D. 1985. Drosophila mushroom body mutants are deficient in olfactory learning. J. Neurogenet. 2, 1-30. ( 10.3109/01677068509100140) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ikeda K, Numata H, Shiga S. 2005. Roles of the mushroom bodies in olfactory learning and photoperiodism in the blow fly Protophormia terraenovae. J. Insect. Physiol. 51, 669-680. ( 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2005.05.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barth M, Heisenberg M. 1997. Vision affects mushroom bodies and central complex in Drosophila melanogaster. Learn. Mem. 4, 219-229. ( 10.1101/lm.4.2.219) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available as electronic supplementary material.