Abstract

Hydrogen bonding principles are at the core of supramolecular design. This overview features a discussion relating molecular structure to hydrogen bond strengths, highlighting the following electronic effects on hydrogen bonding: electronegativity, steric effects, electrostatic effects, π-conjugation, and network cooperativity. Historical developments, along with experimental and computational efforts, leading up to the birth of the hydrogen bond concept, the discovery of nonclassical hydrogen bonds (C—H…O, O—H…π, dihydrogen bonding), and the proposal of hydrogen bond design principles (e.g., secondary electrostatic interactions, resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding, and aromaticity effects) are outlined. Applications of hydrogen bond design principles are presented.

Keywords: aromaticity, hydrogen bonding, resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding, secondary electrostatic interactions

1 |. INTRODUCTION

“Water…shows tendencies both to add and give up hydrogen, which are nearly balanced. […] a free pair of electrons on one water molecule might be able to exert sufficient force on a hydrogen held by a pair of electrons on another water molecule to bind the two molecules together. […] Such an explanation amounts to saying that the hydrogen nucleus held between two octets constitutes a weak ‘bond’.” (Latimer WM and Rodebush WH, 1920)1.

Hydrogen bonding interactions stand at the crossroad between weak noncovalent bonding and strong covalent bonding. They can be as weak as less than a kilocalorie per mole, they can be as strong as half the association of a single C—C bond (e.g., the [F…H…F]− interaction is about 40 kcal/mol), and the directionality of hydrogen bonds gives a clue to how molecules and molecular fragments might arrange in space.2 From the varying strengths and the directionality of hydrogen bonds, emerges the opportunity for chemical design. Since the 1920 report of Latimer and Rodebush,1 regularity in hydrogen bonding patterns were recognized, hydrogen bond design principles were developed, and it became possible to explain and imagine the structures and functions of many hydrogen bonding systems.

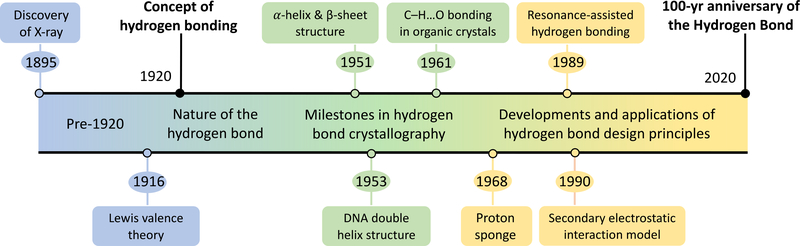

Leading up to the magnum opus of Latimer and Rodebush’s proposal of hydrogen bonding, two events in the early 1900’s steered the direction of hydrogen bond research during the first half of the 20th century: (a) G. N. Lewis’ theory3 of valence and chemical structures (1916)—so that the idea of a hydrogen bond could be conceived, and (b) the discovery of X-ray (1895)—so that a hydrogen bond, that is, close contact between proton-sharing atoms, could be observed. Recognizing that a hydrogen nucleus shared between two atoms could largely influence the three dimensional structure of molecules and molecular fragments initiated a contentious race among multiple groups toward unveiling the double helix DNA structure (1953, Watson–Crick),4 the α-helix structure (1951, Pauling–Corey–Branson)5 and the β-sheet structure (1950, Pauling–Corey)6 of proteins, along with surveys and developments of hydrogen bonding patterns in organic crystals (1950’s–1960’s). These events happened at the height of early applications of crystallography in chemistry and set the stage for the discovery of many hydrogen bond design principles (1990’s–2000’s), which are now routinely applied to areas of recognition, catalysis, and assembly in organic and supramolecular chemistry.

This review presents an overview of hydrogen bond design principles, based on five structural features: electronegativity effects (Section 2), steric effects (Section 3), electrostatic effects (Section 4), π-conjugation effects (Section 5), and cooperativity effects (Section 6). Debates touched on but not discussed in detail include the physical origins of hydrogen bonds and the physical explanations of each design principle. Discussion focuses on how molecular structure affects hydrogen bond strength, and on showcasing selected applications of hydrogen bond design principles.

2 |. ELECTRONEGATIVITY EFFECTS

2.1 |. The classical hydrogen bond

In 1920, Latimer and Rodebush1 (along with the unpublished works of Huggins a year earlier, Box 1) first related the idea of electronegativity and bond polarity to the sharing of a hydrogen atom between two atoms. They noted that ammonia readily adds a hydrogen, hydrogen chloride readily loses one, but water could add or lose a hydrogen, and therefore a hydrogen could be shared between two water molecules and bind two molecules together (Figure 2a). They recognized that ammonium hydroxide (Figure 2b) is another example in which the “union is fairly strong,” explaining that “…the hydrogen nucleus held between two octets constitutes a weak bond.” Huggins proposed the term “hydrogen bridges” to describe the sharing of an H atom between two molecules.7 These early depictions of hydrogen bonds were developed from Lewis’ theory6 for valence and bonding and hinted at the covalent character (i.e., orbital interaction) of hydrogen bonds. A hydrogen bond X—H…Y may be viewed as a donor–acceptor orbital interaction, in which a set of lone pairs on Y donate into the antibonding orbital of X—H.8 The covalent character of hydrogen bonding also has been described by Coulson as “covalent-ionic resonance”9 and by several others, as well as from a valence bond perspective, as “three-center-four-electron” interactions.10–14 An alternative view emerged when Pauling developed a scale of electronegativity,15 proposing an electrostatic explanation (i.e., dipole–dipole interaction) of hydrogen bonding instead, and commenting that, “the hydrogen bond is largely ionic in character […] formed only between the most electronegative atoms.”

BOX 1. HYDROGEN BONDING—A HARD-TO-SWALLOW IDEA.

As contemporaries with Latimer and Rodebush in the lab of G. N. Lewis at Berkeley, Huggins first suggested a crude idea of hydrogen bonding in a class term paper in 1919. His idea was met with dismissal from Bray, who taught the course at the time and who commented that, “Huggins, there are several interesting ideas in the paper, but there is one you’ll never get chemists to believe: the idea that a hydrogen atom can be bonded to two other atoms at the same time.” Even though Latimer and Rodebush described the idea of hydrogen bonding in their 1920 publication, the phrase “hydrogen bond” only appeared for the first time in Lewis’ Valence and the Structure of Atoms and Molecules, in 1923, and the idea remained largely ignored until the mid-1930’s.

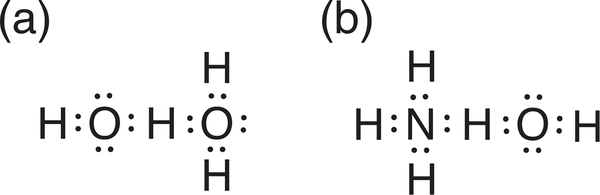

FIGURE 2.

Depictions of hydrogen bonding, in (a) H2OH2O and (b) ammonium hydroxide, based on the early works of Latimer and Rodebush1

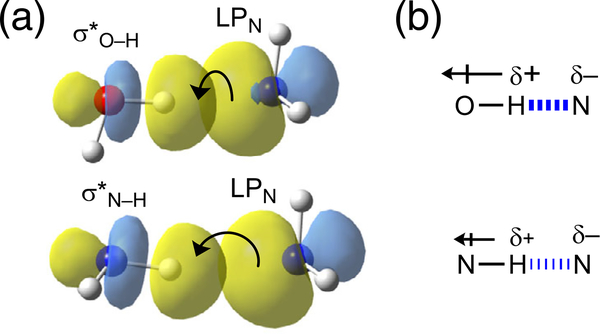

Debates regarding the nature of hydrogen bonding continued for the remainder of the 20th century, but the important effects of electronegativity on hydrogen bond strengths were commonly recognized. An illustrative example comparing the O—H…N vs. N—H…N hydrogen bond is shown in Figure 3. According to the electronegativities of O (3.5) and N (3.0), O—H…N is considered a stronger hydrogen bond than N—H….N, and this trend can be understood from both the orbital interaction and the dipole–dipole interaction model of hydrogen bonding: (a) Since O is more electronegative than N, the antibonding orbital of O—H will have a larger coefficient on the electropositive H, thereby increasing donor-acceptor orbital interaction (Figure 3a). (b) Since O is more electronegative than N, an H atom attached to O will be more positively charged, thereby increasing the dipole–dipole interaction (Figure 3b).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of electronegativity on O—H…N vs. N—H…N hydrogen bond strength. Explanations based on: (a) donor–acceptor orbital interactions (using water…ammonia and ammonia…ammonia as examples), and (b) dipole–dipole interactions

Electronegativity differences are the simplest ways of explaining hydrogen bond strengths, and these effects were used to rationalize hydrogen bonding patterns in the early days of crystallography. Based on surveys of hydrogen bonding patterns in organic crystals, Donohue observed that all acidic hydrogens available in a molecule will be used in hydrogen bonding in the crystal of that compound.16 This idea was significantly expanded in Etter’s works in the 1980’s–1990’s, where she applied graph sets to analyze organic crystals and proposed a set of rules, noting that: (a) All good proton donors and acceptors are used in hydrogen bonding, and that (b) the best hydrogen bond donor and the best hydrogen bond acceptor will preferentially form hydrogen bonds to one another.17,18

A closely related hydrogen bond design principle, considering the acidity and basicity of proton donors and acceptors, is the idea of pKa match.19–22 It was proposed that when a hydrogen bond is formed between an acid and its conjugate base, for example, HF…F− (i.e., [F…H…F]−),23 a matching pKa value can give rise to short, strong, low-barrier hydrogen bonds, in which a proton can readily exchange between two atoms. The low-barrier hydrogen bond hypothesis was originally proposed to explain how enzymes might stabilize charged centers in catalytic reactions and remains a controversial topic.24–26

2.2 |. Nonclassical hydrogen bonds

In their authoritative work, “The Hydrogen Bond (W. H. Freeman, San Francisco, 1960),”27 Pimentel and McClellan explained that X—H…Y can be considered to be a hydrogen bond if there is evidence of bond formation linking the two groups. Without restricting what atoms or groups X and Y had to be, this much broader definition of the hydrogen bond (progressive for its time!) opened imaginative possibilities to many types of “nonclassical” hydrogen bonds. The most common textbook depiction of a hydrogen bond (X—H…Y) is the attractive force of an H atom between two electronegative atoms (F, O, or N). A bonding interaction forms because a lone pair of the electron rich Y atom donates into the σ-antibonding orbital of X—H (Figure 3a), and also because of attractive electrostatic interactions between the interacting H and Y atoms (δ–X—Hδ+…Yδ–) (Figure 3b). Yet, it is increasingly recognized that X and Y do not have to be electronegative atoms. Three types of nonclassical hydrogen bonds are discussed here: C—H…Y interactions, X—H…π interactions, and X—H…H M dihydrogen bonding.

2.2.1 |. C—H…O hydrogen bonding

In her 1962 Nature paper, “The C—H…O Hydrogen Bond in Crystals,” Sutor first considered the possibility of attractive C—H…Y hydrogen bonding.28 She found the carbon–oxygen contacts in many crystals to be closer than the combined van der Waals radii for O and H, and suggested that these interactions might be considered as C—H…O hydrogen bonds (Figure 4a).28,29 She commented that, “The C—H group may be activated by other atoms or groups of atoms promoting ionization or partial ionization of the hydrogen atom. Under these conditions, it resembles the O—H and N—H groups, etc., and it may form hydrogen bonds.”28 Her hypothesis was initially met with strong criticism from Donohue, a prominent crystallographer at the time.30 But studies based on hundreds of neutron diffraction crystal structures 20 years later unveiled even more examples of attractive CH…O, CH…N, and CH…Cl interactions.31

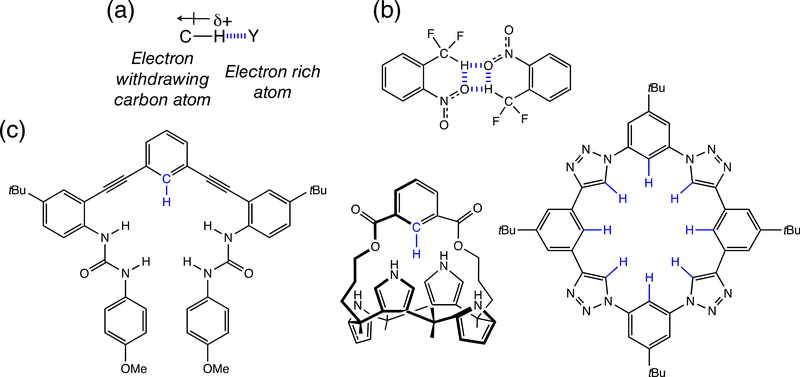

FIGURE 4.

(a) Schematic illustration of CH…Y interactions (Y = electronegative atom or anion). (b) F2C—H…O hydrogen bonding. (c) Examples of anion receptors based on C—H…anion interactions

Decades later following its initial discovery,28,29 the C—H…O hydrogen bond now finds many useful applications in structural chemistry and in supramolecular design.32–35 Lippard et al. demonstrated a remarkable F2C—H…O hydrogen bonding motif36 (Figure 4b), suggesting that C atoms with significant s character can form very strong C—H…O interactions, and proposing that F2C—H groups can be useful for replacing OH groups in medicinal applications of hydrogen bonding. Anion binding based on C—H…anion interactions have gained increasing popularity,37 and many receptors containing aryl C—H hydrogen bonding interactions have been developed (see Figure 4c for some examples).38–40

2.2.2 |. X—H…π hydrogen bonding

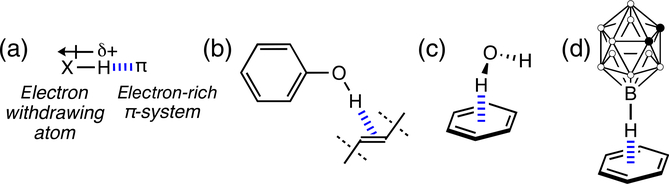

π-Bonds are electron rich and can replace F, O, or N atoms as hydrogen bond acceptors, giving rise to X—H…π hydrogen bonding interactions (Figure 5a). π-Hydrogen bonding interactions are weaker than classical hydrogen bonds, but they are prevalent in chemistry and biology, and it is increasingly recognized that these weak interactions are important for interpreting the interactions of aromatic rings, the conformations of organic compounds, chemical and biological recognition, crystallographic data, and the three dimensional structures of proteins.41

FIGURE 5.

(a) Schematic illustration of XH…π interactions. (b) and (c) Examples of OH…π hydrogen bonding. (d) Example of B—H…π hydrogen bonding

West first observed, based on infrared studies, that addition of olefins to phenol and other alcohols led to the appearance of a broad O—H band at low frequencies, suggesting that O—H groups could interact favorably with olefinic π-bonds (Figure 5b).42 Benzene forms hydrogen bonds with water through O—H…π interactions (Figure 5c).43 Many drug–protein interactions feature N—H…π hydrogen bonding involving amine functional groups and aromatic rings.41 X—H…π interactions also can involve X atoms that are not especially electronegative. For example, C—H…π interactions are mostly the result of dispersion effects.44,45 Interestingly, Imamoto et al.46 found that loss of a single CH…π interaction, between an alkyl group and π-ring of residues, could significantly alter the stability and photocycle of the photoactive yellow protein. Cremer et al. reported examples of B—H…π interactions in a carborane…benzene complex (Figure 5d), a diborane (B2H6)…benzene complex, and an Ir-dimercapto-carborane complex.47

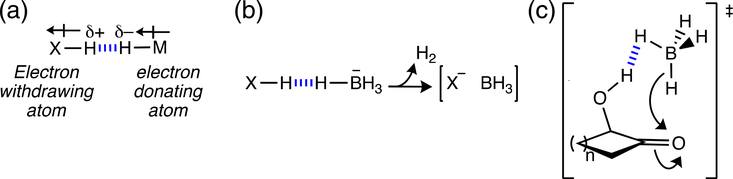

2.2.3 |. X—H…HM dihydrogen bonding

Hydrogen bonding interactions can form between two hydrogen atoms if one is partial negatively charged and the other is partial positively charged (δ–X—Hδ+…δ–H—Mδ+) (Figure 6a).48–50 This happens when one H atom is attached to an electronegative center (X), and the other H atom is attached to an electropositive center (M), such as boron, silicon, or transition metals. In essence, the dihydrogen bond can be seen as an attractive proton–hydride interaction. Jackson et al. found that dihydrogen bonds could be used to preorganize colavent organic frameworks and to control the stereoselectivity outcome of organic reactions.51,52 Dihydrogen bonds can transform into hydrogen–hydrogen covalent bonds, driving off H2 and leaving Lewis acidic and basic sites in close proximity, and ready to form strong covalent bonds (Figure 6b).51 Dihydrogen bonds also were shown to direct the diastereoselective outcomes of borohydride reduction reactions (Figure 6c).52 Based on computational and experimental NMR data, a favorable Si—H…H—O interaction was found between trihexylsilane and perfluoro-tert-butanol.53 Besides electrostatically-driven dihydrogen bonding, homopolar, dispersion-driven, dihydrogen bonding interactions, for example, C—H…H—C interactions between dimers of alkanes and polyhedranes,54 and X—H…H—X (X = B, Al, Ga) interactions,55 also have been reported.

FIGURE 6.

(a) Schematic illustration of dihydrogen bonding. Dihydrogen bonds were shown to direct the (b) preassembly of covalent materials, and (c) the diastereoselectivity of borohydride reduction

3 |. STERIC EFFECTS

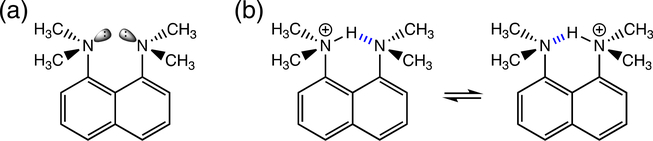

Steric effects were one of the earliest aspects to be considered in hydrogen bond design. Alder et al.’s 1968 work on the 1,8-bis(dimethylamino)naphthalene (DMAN, the original “proton sponge”) first demonstrated that molecular strain can affect the Brønsted basicity of diamines.56 In DMAN (pKa = 18.6 in MeCN), two dimethylamino groups are attached to a naphthalene backbone, and two N lone pairs are pointed toward each other, giving rise to repulsive interactions (Figure 7a). Protonation of the diamine relieves lone pair repulsion, forming a low-barrier [N…H…N]+ hydrogen bond (Figure 7b).57,58 Along with other medium-ring diamine and polyamine structures, DMAN shows remarkable proton accepting ability compared with the typical aliphatic amine.

FIGURE 7.

(a) The original “proton sponge,” DMAN. (b) Protonation of the diamine relieves lone pair repulsion, resulting in low-barrier [N…H…N]+ hydrogen bonding

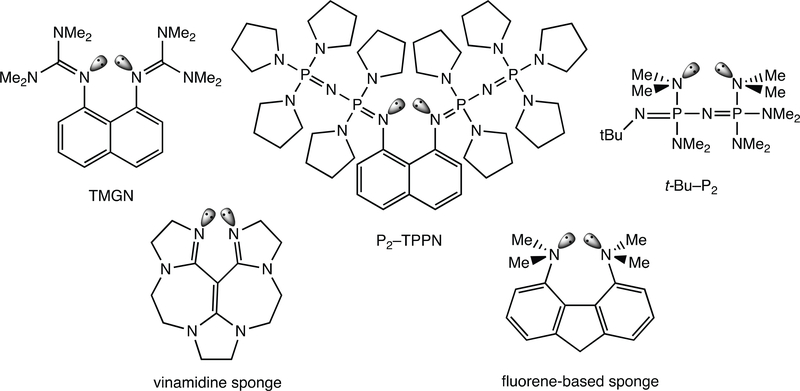

Following Alder’s classic example, many examples of proton sponges with increased molecular strain and enhanced basicities were developed (Figure 8). Two strategies for developing proton sponges include: (a) Adding bulky, electrondonating, substituents to the amino groups (i.e., a “buttressing” effect). For example, guanidinyl-substituted proton sponges such as 1,8-bis(tetramethyl-guanidinyl)naphthalene (TMGN) (pKa = 25.1 in MeCN)59 and phosphazene-substituted proton sponges like P2-TPPN (pKa = 42.1 in MeCN)60,61 show increased basicity compared to DMAN. (b) Modifying the aromatic backbone to push the N lone pairs even closer to each other (i.e., a “crowding” effect). Some examples include t-Bu–P2 (pKa = 33.4 in MeCN),62 vinamidine (pKa = 31.9 in MeCN),63 and a fluorene-based sponge which readily deprotonates DMAN and displays near linear N…H…N hydrogen bonding.64

FIGURE 8.

Examples of other diamine-based proton sponges: TMGN, P2-TPPN, t-Bu–P2, vinamidine, and a fluorene-based proton sponge

4 |. ELECTROSTATIC EFFECTS

4.1 |. Secondary electrostatic interactions

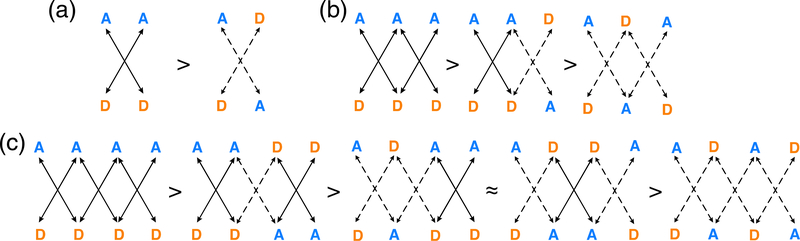

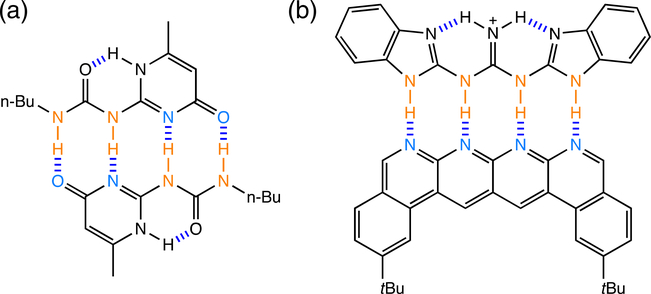

The secondary electrostatic interaction (SEI) model of Jorgensen and Pranata65,66 has long been regarded as a textbook guideline for designing multipoint hydrogen bonding arrays, that is, hydrogen bonded complexes with more than one set of hydrogen bonds. They suggested that both primary electrostatic interactions (between the proton donor and acceptor) and secondary electrostatic interactions (between a proton donor or acceptor group and the hydrogen bonding group diagonal to it) could affect the association strengths of arrays.

According to the SEI model, arrays with all proton donors (D) on one fragment and all proton acceptors (A) on the other fragment (e.g., an “AA–DD” array) will exhibit stronger association strengths than arrays with alternating D and A arrangements (e.g., an “AD–DA” array), since the former arrangement maximizes the number of attractive electrostatic interactions. Note two attractive secondary interactions in the AA–DD array, but two repulsive secondary interactions in the AD–DA array (see Figure 9a). Based on the SEI model, the association strengths of triply hydrogen bonded arrays are expected to follow the order: AAA–DDD > AAD–DDA > ADA–DAD (Figure 9b), and those of quadruply hydrogen bonded arrays are expected to follow the order: AAAA–DDDD > ADDA–DAAD ≈ ADAA–DADD > ADAD–DADA (Figure 9c). Especially robust multipoint hydrogen bonding arrays have been prepared following the SEI model (Figure 10).67,68 Statistical analyses supporting the SEI model have shown that the association strengths of hydrogen bonded arrays could be reproduced by summing up empirical increments69,70 or by combining calculated electrostatic forces71 that take into account the primary and secondary electrostatic interactions in complexes. It was suggested that electrostatic interactions between remote atom pairs in a hydrogen-bonded complex also could affect array association.72

FIGURE 9.

Secondary electrostatic interactions (SEIs) between proton donors (“D,” in orange) and acceptors (“A,” in blue) in: (a) doubly, (b) triply, and (c) quadruply hydrogen bonded arrays. Solid lines indicate attractive interactions and dashed lines indicate repulsive interactions

FIGURE 10.

Examples of quadruply hydrogen bonded arrays prepared based on the secondary electrostatic interaction (SEI) model. (a) 2-Ureido-4-pyrimidone,67 and (b) Blight’s AAAA-DDDD array68

Nevertheless, the SEI model remains a matter of debate and its limitations continue to invite controversy. Lukin and Leszynski argued based on extensive quantum chemical calculations that some ADD–DAA arrays appear to have weaker associations than their analogous AAA–DDD arrays only because of a more solvated ADD and DAA monomer in wet polar solvent.73 Fonseca Guerra et al. emphasized the importance of donor–acceptor orbital interactions74,75 and the effects of Pauli repulsion76,77 on the association strengths of arrays. Wu et al. found that arrays with the same SEI patterns can have varying association strengths depending on the aromatic characters of the interacting fragments.78–80 Rocha-Rinza et al. suggested that the SEI model might be refined by considering the acid–base properties of the hydrogen bonding groups.81,82 Fonseca Guerra et al. examined the SEI model to understand why it predicts binding strengths that are in line with experimental results, even though it oversimplifies the description of hydrogen bonds as interacting point charges. They pointed out that charge accumulation on the hydrogen bonded fragments is the result of both electrostatic interactions and σ-orbital interactions.83

Despite a large body of experimental and theoretical work challenging the SEI model, it remains a useful principle for designing multipoint hydrogen bonding arrays. The SEI model is chemically intuitive and can be easily applied based on simple “back-of-the-envelope” illustrations of donor and acceptor patterns in compounds.

5 |. Π-CONJUGATION EFFECTS

5.1 |. Resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding

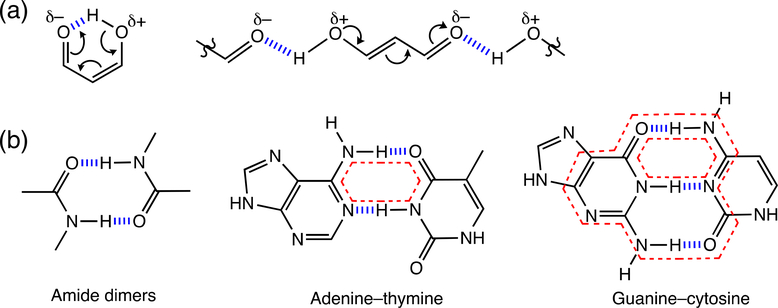

In the late 1980’s, Gilli et al. introduced the idea of “resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding” (RAHB)—a simple hydrogen bond concept relating π-electron delocalization to hydrogen bonding in compounds.84–87 They noted that β-diketones that formed either: (a) intramolecular hydrogen bonds, or (b) a linear array of intermolecular hydrogen bonds, displayed enhanced π-electron delocalization (Figure 11a).84 Resonance-assisted O—H…O=C hydrogen bonds were found to display short O…O distances, downfield shifted 1H NMR signals, and red-shifted O—H stretching frequencies. Gilli et al. reasoned that partial charges generated by resonance on the O atom of the carbonyl group makes it a better proton acceptor, and as a result, the proton donor and acceptor groups move closer to each other, giving rise to stronger hydrogen bonding. In this way, hydrogen bonding increases π-resonance, and π-resonance enhances hydrogen bond strength. As noted in the original paper, a reviewer of Gilli’s initial paper suggested an alternative explanation, based on synergy between the σ- and π-framework. When a hydrogen bonding C=O group is π-conjugated, π-resonance decreases the electronegativity of the O atom, and this raises the energy of the in-plane lone pair of O, making it a stronger hydrogen bond acceptor. Gilli’s work concluded by speculating on the many imaginable implications of RAHB in chemical and biological systems, including hydrogen-bonded dimers, the secondary structures of proteins,88 and DNA base pairs (Figure 11b).

FIGURE 11.

(a) Intramolecular and intermolecular resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding (RAHB) in β-diketone. (b) Possible RAHB effects in hydrogen-bonded dimers and base pairs

In the 30 years following Gilli’s proposal of the RAHB idea, opposing views either debating the importance of RAHB or the origin of the effect were put forth, based on a variety of theoretical approaches. Based on energy decomposition analyses of DNA base pairs, Fonseca Guerra et al. reported that even though π-polarization effects can enhance hydrogen bonding, electrostatic and donor-acceptor orbital interactions dominate the total interaction energy.74,75 Based on valence bond and atoms-in-molecules computations, Gora et al. attributed the effects of RAHB to charge delocalization—an idea captured in Gilli’s explanation of the RAHB effect, describing that partial charges generated by resonance can enhance hydrogen bonding.89 Evidence based on computed energy decomposition analyses,90 block-localized wavefunction analyses,91 and coupling constants,92 suggested that the effects of RAHB originated from geometric constraints of the σ-framework. In line with these ideas, later works from Fonseca Guerra et al.,90 while finding little evidence for σ- vs. π- synergy in RAHB systems, confirmed that RAHB happens because π-resonance moves the donor and acceptor groups closer in proximity—an idea also captured in Gilli’s account of the RAHB effect.

Most of the supposed arguments and works put forth to dispute or reexamine the RAHB idea, have reinforced rather than disproved Gilli’s original explanation and novel discovery of the RAHB effect. This simple and powerful concept, that is, the connection between π-conjugation and hydrogen bonding,93 has found significant use in synthetic transformations, in the design of chelating pockets for coordination, in molecular recognition, in the design of molecular switches, and in crystal engineering, among many other applications in organic chemistry.94

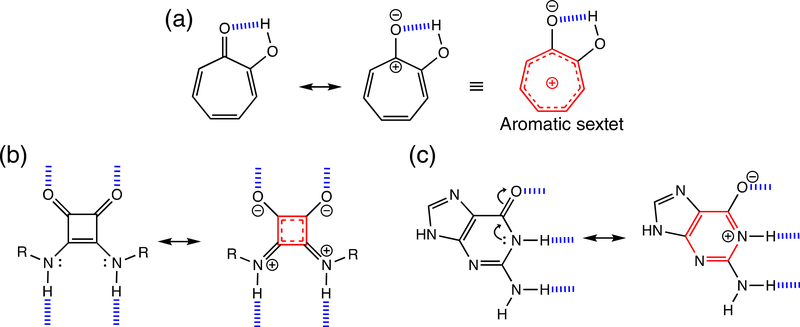

5.2 |. Aromaticity and antiaromaticity

Dewar first recognized a relationship between hydrogen bonding and aromaticity, when he proposed the structure of stipitatic acid, calling it a nonbenzenoid aromatic. He suggested that stipitatic acid and many tropolone derivatives might be considered to be “aromatic,” since intramolecular hydrogen bonding between C=O and OH groups at ortho positions could polarize the ring π-electrons to increase [4n + 2] π-aromaticity in the seven membered ring (Figure 12a).95 More examples relating the effects of aromaticity gain and hydrogen bonding appeared later on. Aromaticity gain was found to affect the tautomeric equilibria of hydrogen bonding compounds,96,97 to increase the basicity of organic superbases,98,99 and to enhance the hydrogen bonding ability of heterocycles.100–103 It was suggested that hydrogen bonding of squaramide, at the two carbonyl and two amine groups, increased cyclic two π-electron aromaticity in the four membered ring (Figure 12b).102,103 In essence, the effect of aromaticity gain and loss on hydrogen bonding can be considered as a manifestation of the RAHB concept. While π-conjugated hydrogen bonding compounds can all benefit from “resonance-assistance,” the energetic consequences of RAHB are especially pronounced when aromaticity gain happens. Interestingly, Gilli’s original depiction of the supposed effects of RAHB in the guanine-cytosine and adenine-thymine base pairs, considered only the six membered ring of guanine and not the ring moieties of other nucleobases (see Figure 11b, red dotted lines) to have special importance for resonance-assistance (note resonance form showing aromaticity gain in guanine, see Figure 12c).

FIGURE 12.

Resonance structures showing the effects of aromaticity gain in (a) tropolone, and in hydrogen-bonded (b) squaramide and C) guanine

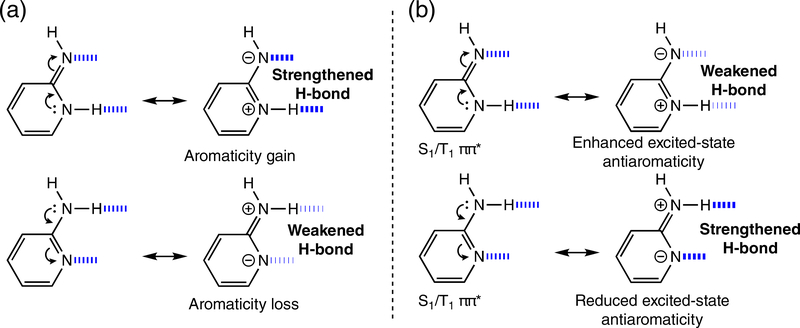

In 2014, a proof-of-concept paper by Wu et al. generalized the relationship between aromaticitiy gain and loss and hydrogen bonding, delineating its possible implications for hydrogen bond design.104 They reported that hydrogen bonds are stronger than expected when they increase [4n + 2] cyclic π-electron delocalization (aromaticity gain) in the hydrogen bonding compounds, and are weaker than expected when they decrease [4n + 2] cyclic π-electron delocalization (aromaticity loss) in compounds (Figure 13a). Later works from Wu and Jackson et al. 105,106 extended the original idea to show that the opposite happens for [4n] “antiaromatic” rings, and these reciprocal relationships were later applied to rationalize the trends of hydrogen bonding in self-assembling systems,80,107–109 in multipoint arrays,78,79 and may rationalize short, strong hydrogen bonds in enzymes.110

FIGURE 13.

(a) Aromaticity gain and loss in hydrogen-bonded heterocycles, and (b) a reversed effect in photoexcited states

Whether light irradiation strengthens or weakens a hydrogen bond also can be related to changes in (anti)aromaticity of hydrogen bonding compounds in the excited state.111 Just as the rules for orbital interactions in organic reactions reverse in the excited state, the electron-counting rules for aromaticity and antiaromaticity also reverse at the first singlet and triplet ππ* states. According to Baird’s rule: [4n] π-ring compounds are excited-state aromatic, and [4n + 2] π-ring compounds are excited-state antiaromatic.112,113 By connecting Baird’s rules to the effects of hydrogen bonding, Wu et al. deduced and demonstrated that,111 upon photoexcitation, hydrogen bonding interactions that polarize ring π-electrons to increase excited-state antiaromaticity in compounds are weakened (Figure 13b). Conversely, hydrogen bonds that decrease excited-state antiaromaticity in compounds are strengthen (Figure 13b), and in the extreme, relief of excited-state antiaromaticity can drive excited-state proton transfer reactions.111 Although not properly recognized in a large body of supporting examples,114–118 this relationship—between excited-state (anti) aromaticity and excited-state hydrogen bonds—explains why photoexcitation strengthens some hydrogen bonds but weakens others.

6 |. COOPERATIVE EFFECTS

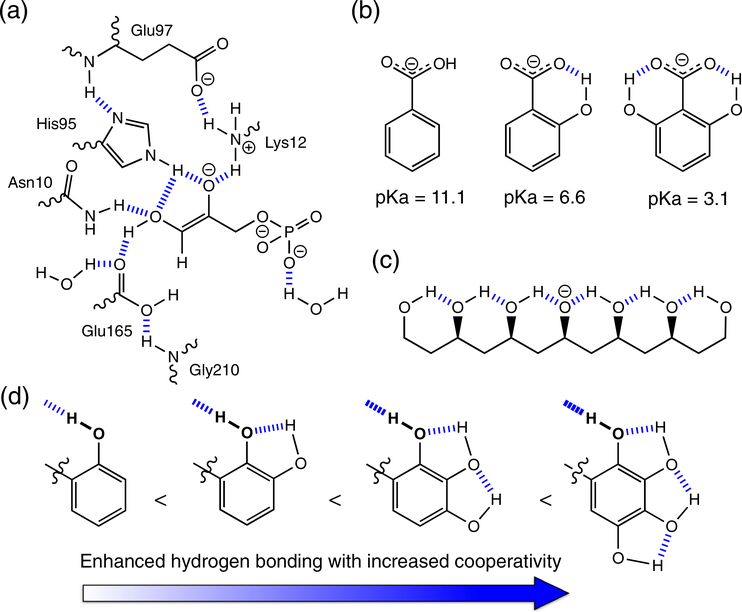

Networks of hydrogen bonds can give rise to strong hydrogen bonding interactions. Water clusters can form through networks of hydrogen bonds. Enzymes can engage multiple hydrogen bonding interactions to stabilize charges and facilitate catalysis (Figure 14a).119,120

FIGURE 14.

(a) Hydrogen bonding networks in the active site of triosephosphate isomerase. (b) Cooperative hydrogen bonds can stabilize the conjugate base of OH substituted benzoic acid (note pKa values for the acid). (c) Example of a covalent polyol system. (d) Enhanced hydrogen bonding resulting from neutral, short-range networks (see OH group in bold)

In an elegant experiment, Shan and Herschlag demonstrated that networks of intramolecular hydrogen bonds could significantly increase the acidity of benzoic acid in dimethylsulfoxide; the pKa of benzoic acid decreases by 4 units, when one hydrogen bonding OH group is placed ortho to the carboxylic acid group, and by an enormous 8 units, when two OH groups are placed ortho to the carboxylic acid group (Figure 14b).121 Based on a series of covalent polyol models (Figure 14c), Wang, Kass, and coworkers showed that hydrogen bonding networks can stabilize charged centers, and that the compounding effects of having multiple hydrogen bonds may explain how charges in enzyme active sites affect catalysis and conformational changes.122,123 Rather than attributing the stabilization of charges in enzymes to the possible existence of a single short, strong “low-barrier” hydrogen bond, these authors proposed that multiple hydrogen bonds stabilize charged centers in enzymes. Neutral systems also can display strong, short-range cooperativity. Based on a series of synthetic molecular balances, Cockroft et al. demonstrated that neutral hydrogen bonds (see OH in bold, Figure 14d) could be strengthened by increasing numbers of cooperative, intramolecular hydrogen bonding interactions.124 Networks of hydrogen bonds have been applied to the design of inhibitors, catalysts, and molecular receptors.125–128

7 |. CONCLUSION

Chemistry is largely a science of molecular design, and hydrogen bonding interactions are the workhorse for linking molecules and molecular fragments in a chemically intuitive way. Since the 1920 paper of Latimer and Rodebush, a hundred years has passed, and discussions surrounding “The Hydrogen Bond” has evolved from debates concerning the nature of the interaction, to milestones in crystallography, to explosive developments in the concept and application of hydrogen bond design principles (Figure 1). A potential area of growth is to rationalize the effects of external stimuli (e.g., light, pressure) on hydrogen bonding. We close our overview of the topic by emphasizing the value of simple hydrogen bonding principles, like the secondary electrostatic interaction model and the resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding concept, and their imperative roles in pushing the realms of molecular design in many areas of chemistry (e.g., in supramolecular catalysis, recognition, and assembly). Concepts like these are powerful, not because of theoretical rigor but because of conceptual simplicity—any chemist can pick up a pen and a piece of paper and sketch out the next ideas for an experiment. Whether or not the next experiments “work” is a separate issue, what matters more is that these principles influence the evolution of molecular design in chemistry.

FIGURE 1.

Timeline for the development of hydrogen bond design principles

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J. I. W. thanks the National Science Foundation (NSF) (CHE-1751370) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institute of Health (R35GM133548) for grant support.

Funding information

National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Grant/Award Number: R35GM133548; National Science Foundation, Grant/Award Number: CHE-1751370

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Latimer WM, Rodebush WH. Polarity and ionization from the standpoint of the Lewis theory of valence. J Am Chem Soc. 1920;42(7): 1419–1433. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeffrey GA. An introduction to hydrogen bonding. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis GN. Valence and the structure of atoms and molecules. New York, NY: Chemical Catalog Co., 1923. p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson JD, Crick FHC. Molecular structure of nucleic acids: A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature. 1953;171:737–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pauling L, Corey RB, Branson HR. The structure of proteins: Two hydrogen bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1951;37(4):205–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pauling L, Corey RB. The pleated sheet, a new layer configuration of polypeptide chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1951;37(5):251–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huggins ML. Hydrogen bridges in organic compounds. J Org Chem. 1936;1(5):407–456. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinhold F, Landis CR. Valency and bonding: A natural bond orbital donor–acceptor perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulson CA. The hydrogen bond–a review of the present position. Research. 1957;10:149–159. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pimentel GC. The bonding of trihalide and bifluoride ions by the molecular orbital method. J Chem Phys. 1951;19(4):446–448. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rundle RE. Coordination number and valence in modern structural chemistry. Rec Prog Chem. 1962;23(1962):195–221. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coulson CA. The nature of the bonding in xenon fluorides and related molecules. J Chem Soc. 1964;1442–1454. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munzarová ML, Hoffman R. Electron-rich three-center bonding: Role of s, p interactions across the p-block. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124 (17):4785–4795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nemes CT, Laconsay CJ, Galbraith JM. Hydrogen bonding from a valence bond theory perspective: The role of covalency. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2018;20(32):20963–20969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pauling L The nature of the chemical bond. 3rd ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donohue J The hydrogen bond in organic crystals. . 1952;56(4):502–510. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etter MC. A new role for the hydrogen-bond acceptors in influencing packing patterns of carboxylic acids and amids. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104(4):1095–1096. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Etter MC. Encoding and decoding hydrogen-bond patterns of organic compounds. Acc Chem Res. 1990;23(4):120–126. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerlt JA, Gassman PG. An explanation for rapid enzyme-catalyzed proton abstraction from carbon acids: Importance of late transition states in concerted mechanisms. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115(24):11552–11568. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerlt JA, Gassman PG. Understanding the rates of certain enzyme-catalyzed reactions: Proton abstraction from carbon acids, acyl transfer reactions, and displacement reactions of phosphodiesters. Biochemistry. 1993;32(45):11934–11952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cleland WW, Kreevoy MM. Low-barrier hydrogen bonds and enzyme catalysis. Science. 1994;264(5167):1887–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frey PA, Witt SA, Tobin JB. A low-barrier hydrogen bond in the catalytic triad of serine protease. Science. 1994;264(5167):1927–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham JD, Buytendyk AM, Wang D, Bowen KH, Collins KD. Strong, low-barrier hydrogen bonds may be available to enzymes. Biochemistry. 2014;53(2):344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perrin CL. Are short, low-barrier hydrogen bonds unusually strong? Acc Chem Res. 2010;43(12):1550–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guthrie JP. Short strong hydrogen bonds: Can they explain enzyme catalysis? Chem Biol. 1996;3(3):163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrin CL, Nielson JB. Strong hydrogen bonds in chemistry and biology. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1997;48:511–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pimentel GC, McClellan AL. The hydrogen bond. Freeman, San Francisco and London: W. H, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutor DJ. The C–H… O hydrogen bond in crystals. Nature. 1962;195:68–69. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutor DJ. Evidence for the existence of C–H· · ·O hydrogen bonds in crystals. J Chem Soc. 1963;0:1105–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Structural DJ. Chemistry and molecular biology. San Francisco, CA: A. Rich and N. Davidson, W. H. Freeman, 1968;p. 443–465. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor R, Kennard O. Crystallographic evidence for the existence of C–H· · ·O, C–H· · ·N, and C–H· · ·cl hydrogen bonds. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104(19):5063–5070. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu Y, Kar T, Scheiner S. Fundamental properties of the CH· · ·O interaction: Is it a true hydrogen bond? J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121(40): 9411–9422. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheiner S Weak H-bonds. Comparisons of CH· · ·O to NH· · ·O in proteins and PH· · ·N to direct P· · ·N interactions. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13(31):13860–13872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desiraju GR, Steiner T. The weak hydrogen bond: In structural chemistry and biology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desiraju GR. The C−H· · ·O hydrogen bond: Structural implications and supramolecular design. Acc Chem Res. 1996;29(9):441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sessler CD, Rahm M, Becker S, Goldberg JM, Wang F, Lippard SJ. CF2H, a hydrogen bond donor. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139(27): 9325–9332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eytel LM, Fargher HA, Haley MM, Johnson DW. The road to aryl C–H…anion binding was paved with good intentions: Fundamental studies, host design, and historical perspectives in CH hydrogen bonding. Chem Commun. 2019;55(36):5159–5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoon D-W, Gross DE, Lynch VM, Sessler JL, Hay BP, Lee C-H. Phenyl-, pyrrole-, and furan-containing diametrically strapped calix[4] pyrroles. An experimental and theoretical study of hydrogen bonding effects in chloride anion recognition. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008; 47(27):5038–5042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Flood AH. Strong, size-selective, and electronically tunable C–H…halide binding with steric control over aggregation from synthetically modular, shape-persistent [34]Trazolophanes. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(36):12111–12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Treseca BW, Zakharov LN, Carroll CN, Johnson DW, Haley MM. Aryl C–H…cl− hydrogen bonding in a fluorescent anion sensor. Chem Commun. 2013;49(65):7240–7242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyer EA, Castellano RK, Diederich F. Interactions with aromatic rings in chemical and biological recognition. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42(11):1210–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.West R Hydrogen bonding of phenols to olefins. J Am Chem Soc. 1959;81(7):1614–1617. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suziki S, Green PG, Bumgarner RR, Dasgupta S, Goddard WA III, Blake GA. Benzene forms hydrogen bonds with water. Science. 1992; 257(5072):942–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishio M CH/π hydrogen bonds in crystals. CrstEngComm. 2004;6(27):130–158. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nishio M The CH/π hydrogen bond in chemistry. Conformation, supramolecules, optical resolution and interactions involving carbohydrates. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13(31):13873–13900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harigai M, Kataoka M, Imamoto Y. A single CH/π weak hydrogen bond governs stability and the photocycle of the photoactive yellow protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(33):10646–10647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, Dai H, Yan H, Zou W, Cremer D. B–H· · ·π interaction: A new type of nonclassical hydrogen bonding. J Am Chem Soc. 2016; 138(13):4334–4337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crabtree RH. A new type of hydrogen bond. Science. 1998;282(5396):2000–2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crabtree RH, Siegbahn PE, Eisenstein O, Rheingold AL, Koetzle TF. A new intermolecular interaction: Unconventional hydrogen bonds with element−hydride bonds as proton acceptor. Acc Chem Res. 1996;29(7):348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Custelcean R, Jackson JE. Dihydrogen bonding: Structures, energetics, and dynamics. Chem Rev. 2001;101(7):1963–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Custelcean R, Jackson JE. Topochemical control of covalent bond formation by dihydrogen bonding. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120(49): 12935–12941. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gatling SC, Jackson JE. Reactivity control via dihydrogen bonding: Diastereoselection in borohydride reductions of α-hydroxyketones. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121(37):8655–8656. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang L, Hubbard TA, Cockroft SL. Can non-polar hydrogen atoms accept hydrogen bonds? Chem Commun. 2014;50(40):5212–5214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Echeverría J, Aullón G, Danovich D, Shaik S, Alvarez S. Dihydrogen contacts in alkanes are subtle but not faint. Nat Chem. 2011;3(4): 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Echeverría J, Aullón G, Alvarez S. Dihydrogen intermolecular contacts in group 13 compounds: H…H or E…H (E = B, Al, Ga) interactions? Dalton Trans. 2017;46(9):2844–2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alder RW, Bowman PS, Steele WRS, Winterman DR. The remarkable basicity of 1,8-bis(dimethylamino)naphthalene. Chem Comm. 1968;13:723–724. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Staab HA, Saupe T. “Proton sponges” and the geometry of hydrogen bonds: Aromatic nitrogen bases with exceptional basicities. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1988;27(7):865–879. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alder RW. Strain effects on amine basicities. Chem Rev. 1989;89(5):1215–1223. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raab V, Kipke J, Gschwind RM, Sundermeyer J. 1,8-Bis(tetramethylguanidino)naphthalene (tmgn): A new, superbasic and kinetically active “proton sponge”. Chem A Eur J. 2002;8(7):1682–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raab V, Gauchenova E, Merkoulov A, et al. 1,8-Bis(hexamethyltriaminophosphazenyl)naphthalene, HMPN: A superbasic bisphosphazene “proton sponge”. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(45):15738–15743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kögel JF, Oelkers B, Kovačevic B, Sundermeyer J. A new synthetic pathway to the second and third generation of superbasic bisphosphazene proton sponges: The run for the best chelating ligand for a proton. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(47):17768–17774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schwesinger R, Schlemper H, Hasenfratz C, et al. Extremely strong, uncharged auxiliary bases; monomeric and polymer-supported polyaminophosphazenes (P2–P5). Liebigs Ann. 1996;1996(7):1055–1081. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwesinger R, Mibfeldt DCM, Peter K, Schnering HGV. Novel, very strongly basic, pentacyclic “proton sponges“ with vinamidine structure. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1987;26(11):1165–1167. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Staab HA, Saupe T, Krieger C. 4,5-Bis(demethylamino)fluorene, a new “proton sponge”. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1983;22(9):731–732. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jorgensen WL, Pranata J. Importance of secondary interactions in triply hydrogen bonded complexes: Guanine–cytosine vs. uracil-2,−6-diaminopyridine. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112(5):2008–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pranata J, Wierschke SG, Jorgensen WL. OPLS potential functions for nucleotide bases. Relative association constants of hydrogen-bonded base pairs in chloroform. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113(8):2810–2819. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sijbesma RP, Beijer FH, Brunsveld L, et al. Reversible polymers formed from self-complementary monomers using quadruple hydrogen bonding. Science. 1997;278(5343):1601–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blight BA, Hunter CA, Leigh DA, McNab H, Thomson PI. An AAAA–DDDD quadruple hydrogen-bond array. Nat Chem. 2011;3(3): 244–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sartorius J, Schneider HJ. A general scheme based on empirical increments for the prediction of hydrogen-bond associations of nucleobases and of synthetic host–guest complexes. Chem A Eur J. 1996;2(11):1446–1452. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Corbin PS, Zimmerman SC. Self-association without regard to prototropy. A heterocycle that forms extremely stable quadruply hydrogen-bonded dimers. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120(37):9710–9711. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tiwari MK, Vanka K. Exploiting directional long-range secondary forces for regulating electrostatics-dominated noncovalent interactions. Chem Sci. 2017;8(2):1378–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Popelier PLA, Joubert L. The elusive atomic rationale for DNA base pair stability. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124(29):8725–8729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lukin O, Leszczynski J. Rationalizing the strength of hydrogen-bonded complexes. Ab initio HF and DFT studies. J Phys Chem A. 2002;106(29):6775–6782. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fonseca Guerra C, Bickelhaupt FM, Snijders JG, Baerends EJ. The nature of the hydrogen bond in DNA base pairs: The role of charge transfer and resonance assistance. Chem A Eur J. 1999;5(12):3581–3594. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guillaumes L, Simon S, Fonseca GC. The role of aromaticity, hybridization, electrostatics, and covalency in resonance-assisted hydrogen bonds of adenine–thymine (AT) base pairs and their mimics. ChemistryOpen. 2015;4(3):318–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van der Lubbe SCC, Fonseca GC. Hydrogen-bond strength of CC and GG pairs determined by steric repulsion: Electrostatics and charge transfer overruled. Chem A Eur J. 2017;23(43):10249–10253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zarycz M, Natalia C, Fonseca GC. NMR 1H-shielding constants of hydrogen-bond donor reflect manifestation of the Pauli principle. J Phys Chem Lett. 2018;9(13):3720–3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu CH, Zhang Y, van Rickley K, Wu JI. Aromaticity gain increases the inherent association strengths of multipoint hydrogen-bonded arrays. Chem Comm. 2018;54(28):3512–3515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang Y, Wu CH, Wu JI. Why do AT and GC self-sort? Hückel aromaticity as a driving force for electronic complementarity in base pairing. Org Biomol Chem. 2019;17(7):1881–1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Paudel H, Das R, Wu CH, Wu JI. Self-assembling quartets: How do π-conjugation patterns affect resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding? Org Biomol Chem. 2020;18(6):1078–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Narváez WEV, Jiménez EI, Romero-Montalvo E, et al. Acidity and basicity interplay in amide and imide self-association. Chem Sci. 2018;9(19):4402–4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Narváez WEV, Jiménez EI, Cantú-Reyes M, Yatsimirsky AK, Hernández-Rodríguez M, Rocha-Rinza T. Stability of doubly and triply H-bonded complexes governed by acidity–basicity relationships. Chem Comm. 2019;55(11):1556–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van der Lubbe SCC, Zaccaria F, Sun X, Fonseca GC. Secondary electrostatic interaction model revised: Prediction comes mainly from measuring charge accumulation in hydrogen-bonded monomers. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141(12):4878–4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gilli G, Bullucci F, Ferretti V, Bertolasi V. Evidence for resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding from crystal-structure correlations on the enol form of the β-diketone fragment. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111(3):1023–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gilli P, Bertolasi V, Ferretti V, Gilli G. Covalent nature of the strong homonuclear hydrogen-bond-study of the O-H—O system by crystal-structure correlation methods. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116(3):909–915. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bertolasi V, Gilli P, Ferretti V, Gilli G. Evidence for resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding. 2. Intercorrelation between crystal structure and spectroscopic parameters in eight intramolecularly hydrogen bonded 1,3-diaryl-1,3-propanedione enols. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113 (13):4917–4925. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bertolasi V, Gilli P, Ferretti V, Gilli G. Resonance-assisted O-H…O hydrogen bonding: Its role in the crystalline self-recognition of β-diketone enols and its structural and IR characterization. Chem A Eur J. 1996;2(8):925–934. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhou Y, Deng G, Zheng YZ, Xu J, Ashraf H, Yu ZW. Evidences for cooperative resonance-assisted hydrogen bonds in protein secondary structure analogs. Scient Rep 2016;6:36932(1–8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gora RW, Maj M, Grabowski SJ. Resonance-assisted hydrogen bonds revisited. Resonance stabilization vs. charge delocalization. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2013;15(7):2514–2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Grosch AA, van der Lubbe SCC, Fonseca GC. Nature of intramolecular resonance assisted hydrogen bonding in malonaldehyde and its saturated analogue. J Phys Chem A. 2018;122(6):1813–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alkorta I, Elguero J, Mo O, Yanez M, Bene JED. Are resonance-assisted hydrogen bonds ‘resonance assisted’? A theoretical NMR study. Chem Phys Lett. 2005;411(4–6):411–415. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jiang X, Zhang H, Wu W, Mo Y. A critical check for the role of resonance in intramolecular hydrogen bonding. Chem A Eur J. 2017;23 (66):16885–16891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sobczyk L, Grabowski SJ, Krygowski TM. Interrelation between H-bond and π-electron delocalization. Chem Rev. 2005;105(10): 3513–3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mahmudov KT, Pombeiro AJL. Resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding as a driving force in synthesis and a synthon in the design of materials. Chem A Eur J. 2016;22(46):16356–16398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dewar MJS. Structure of stipitatic acid. Nature. 1945;155(3924):50–51. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stasyuk OA, Szatyłowicz H, Krygowski TM. Effect of H-bonding and complexation with metal ions on the π-electron structure of adenine tautomers. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12(3):456–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cyranśki MK, Gilski M, Jaskoĺski M, Krygowski TM. On the aromatic character of the heterocyclic bases of DNA and RNA. J Org Chem. 2003;68(22):8607–8613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maksić ZB, Glasovac Z, Despotović I. Predicted high proton affinity of poly-2, 5-dihydropyrrolimines—The aromatic domino effect. J Phys Org Chem. 2002;15(8):499–508. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maksić ZB, Kovacěvić B. Spatial and electronic structure of highly basic organic molecules: Cyclopropeneimines and some related systems. J Phys Chem A. 1999;103(33):6678–6684. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Krygowski TM, Szatyłowicz H, Zachara JE. How H-bonding modifies molecular structure and π-electron delocalization in the ring of pyridine/pyridinium derivatives involved in H-bond complexation. J Org Chem. 2005;70(22):8859–8865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Szatyłowicz H, Krygowski TM, Zachara JE. Long-distance structural consequences of H-bonding. How H-bonding affects aromaticity of the ring in variously substituted aniline/anilinium/anilide complexes with bases and acids. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47(3):875–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Quiñonero D, Prohens R, Garau C, et al. A theoretical study of aromaticity in squaramide complexes with anions. Chem Phys Lett. 2002;351(1–2):115–120. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Quiñonero D, Frontera A, Ballester P, Deyà PM. A theoretical study of aromaticity in squaramide and oxocarbons. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41(12):2001–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wu JI, Jackson JE, Schleyer PR. Reciprocal hydrogen bonding–aromaticity relationships. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(39):13526–13529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kakeshpour T, Wu JI, Jackson JE. AMHB:(anti) aromaticity-modulated hydrogen bonding. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(10):3427–3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kakeshpour T, Bailey JP, Jenner MR, et al. High-field NMR spectroscopy reveals aromaticity-modulated hydrogen bonding in heterocycles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56(33):9842–9846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Talens VS, Englebienne P, Trinh TT, Noteborn WEM, Voets IK, Kieltyka RE. Aromatic gain in a supramolecular polymer. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54(36):10502–10506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Anand M, Fernandez I, Schaefer HF, Wu JI. Hydrogen bond–aromaticity cooperativity in self-assembling 4-pyridone chains. J Comput Chem. 2016;37(1):59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wen Z, Wu JI. Antiaromaticity gain increases the potential for n-type charge transport in hydrogen-bonded π-conjugated cores. Chem Comm. 2020;56(13):2008–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wu CH, Ito K, Buytendyk AM, Bowen KH, Wu JI. Enormous hydrogen bond strength enhancement through π-conjugation gain: Implications for enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry. 2017;56(33):4318–4322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wu CH, Karas LJ, Ottosson H, Wu JI. Excited-state proton transfer relieves antiaromaticity in molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(41):20303–20308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Baird NC. Quantum organic photochemistry. II. Resonance and aromaticity in the lowest 3ππ* state of cyclic hydrocarbons. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94(14):4941–4948. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rosenberg M, Dahlstrand C, Kilså H, Ottosson H. Excited state aromaticity and antiaromaticity: Opportunities for photophysical and photochemical rationalizations. Chem Rev. 2014;114(10):5379–5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sobolewski AL, Domcke W. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding in the S1(ππ*) excited state of anthranilic acid and salicylic acid: TDDFT calculation of excited-state geometries and infrared spectra. J Phys Chem A. 2004;108(49):10917–10922. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhao GJ, Han KL. Early time hydrogen-bonding dynamics of photoexcited coumarin 102 in hydrogen-donating solvents: Theoretical study. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111(13):2469–2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhao GJ, Han KL. Ultrafast hydrogen bond strengthening of the photoexcited fluorenone in alcohols for facilitating the fluorescence quenching. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111(38):9218–9223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhao GJ, Han KL. Effects of hydrogen bonding on tuning photochemistry: Concerted hydrogen-bond strengthening and weakening. ChemPhysChem. 2008;9(13):1842–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhao GJ, Han KL. Hydrogen bonding in the electronic excited state. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45(3):404–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jencks WP. Binding energy, specificity, and enzymic catalysis: The circe effect. Ad Enzymol. 1975;43:219–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Fierke CA, Jencks WP. Two functional domains of coenzyme a activate catalysis by coenzyme a transferase. Pantetheine and adenosine 3′-phosphate 5′-diphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(11):7603–7606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shan SO, Loh S, Herschlag D. Energetic effects of multiple hydrogen bonds. Implications for enzyme catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 1996; 118(24):5515–5518. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Shokri A, Schmidt J, Wang XB, Kass SR. Hydrogen bonded arrays: The power of multiple hydrogen bonds. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134 (4):2094–2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Shokri A, Wang Y, O’Doherty GA, Wang XB, Kass SR. Hydrogen-bond networks: Strengths of different types of hydrogen bonds and an alternative to the low barrier hydrogen-bond proposal. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(47):17919–17924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dominelli-Whiteley N, Brown JJ, Muchowska KB, et al. Short-range cooperativity in hydrogen-bond chains. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017; 56(26):7658–7662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kato Y, Conn MM, Rebek J Jr. Hydrogen bonding in water using synthetic receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(4):1208–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Jeong KS, Rebek J Jr. Molecular recognition: Hydrogen bonding and aromatic stacking converge to bind cytosine derivatives. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110(10):3327–3328. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Huang C-Y, Cabell LA, Anslyn EV. Molecular recognition of cyclitols by neutral polyaza-hydrogen-bonding receptors: The strength and influence of intramolecular hydrogen bonds between vicinal alcohols. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116(7):2778–2792. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zimmerman SC, VanZyl CM, Hamilton GS. Rigid molecular tweezers: Preorganized hosts for electron donor-acceptor complexation in organic solvents. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111(4):1373–1381. [Google Scholar]