Abstract

Novel piperidinyl-based sulfamide derivatives were designed and synthesized through various synthetic routes. Anticancer activities of these sulfamides were evaluated by phenotypic screening on National Cancer Institute’s 60 human tumor cell lines (NCI-60). Preliminary screening at 10 μM concentration showed that piperidinyl sulfamide aminoester 26 (NSC 749204) was sensitive to most of the cell lines in the panel. Further dose-response studies showed that 26 was highly selective for inhibition of colon cancer cell lines with minimum GI50 = 1.88 μM for COLO-205 and maximum GI50 = 11.1 μM for SW-620 cells. These newly synthesized sulfamides were also screening for their Tdp1 inhibition activity. Compound 18 (NSC 750706) showed significant inhibition of Tdp1 with IC50 = 23.7 μM. Molecular-docking studies showed that 18 bind to Tdp1 in its binding pocket similar to a known Tdp1 inhibitor.

Keywords: Piperidinyl sulfamides, Synthesis, Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (Tdp1), Anti-cancer, Biological activity

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, the sulfamide functionality has found extensive use in medicinal chemistry for the development of novel small molecule therapeutic agents and high affinity protein ligands (Winum et al., 2006a; Winum et al., 2006b; Barlier and Jaquet, 2006; Bolli et al., 2012; Chahine et al., 2010; Katz et al., 2011; Pan et al., 2010; Parrish et al., 2007; Reitz et al., 2009; Scozzafava et al., 2006; Temperini et al., 2007; Thiry et al., 2008). The utility of sulfamides can be attributed to the ability to introduce up to four different substituents on two nitrogen atoms, thereby offering diversity. Moreover, the sulfamide functional group can also act as a useful biosteric replacement for sulfonamide, sulfamate, urea, carbamate, ketoamide, ester, and amide functionalities when incorporated into putative pharmaceutical agents, as it has the potential to construct several electrostatic interactions with protein and other targets (Winum et al., 2006a; Winum et al., 2006b; Reitz et al., 2009). Herein, we report the design and synthetic route scouting to synthesize novel piperidyl-based sulfamide compounds and their anticancer activity evaluation using phenotypic screening on NCI-60 human tumor cell lines.

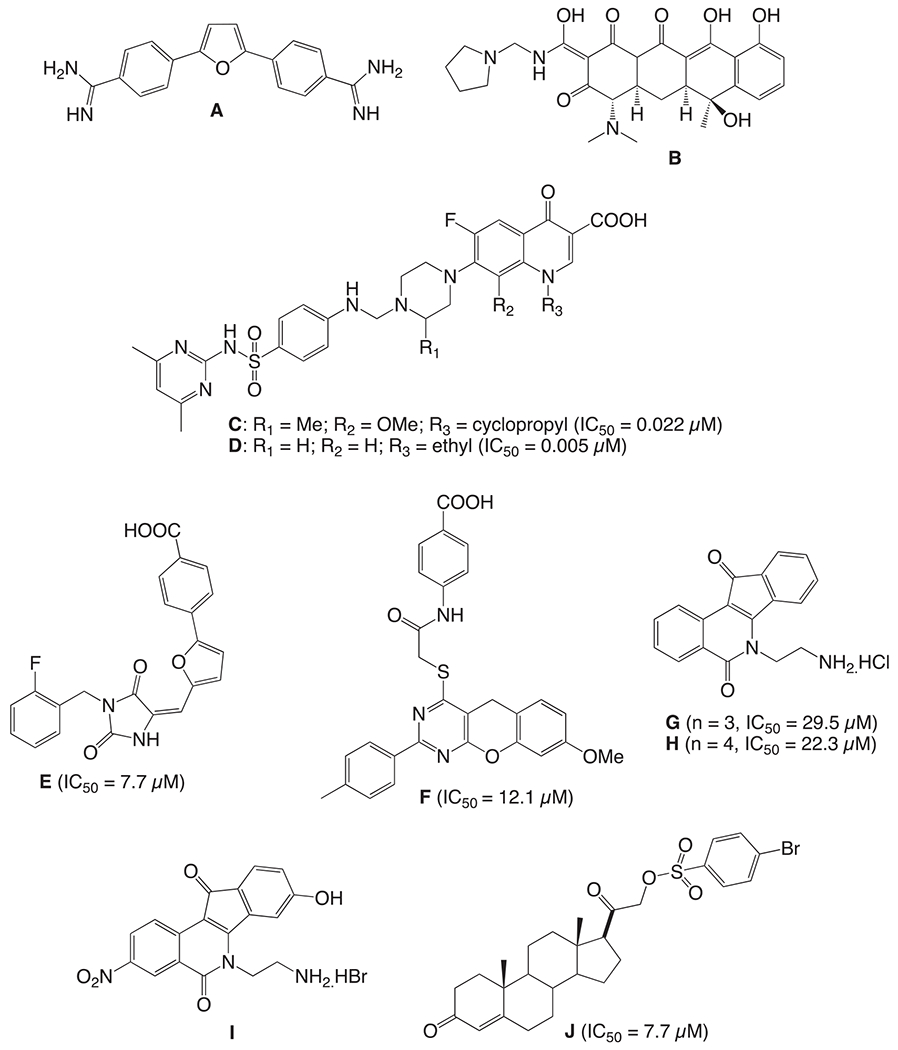

Topoisomerase 1 (Top1) inhibitors e.g. camptothecin and topotecan are well known anticancer agents that reversibly bind and trap Top1 DNA cleavage complex (Top1cc) to prevent the replication of single strand DNA molecules leading to DNA damage and cell death (Wang, 1996; Pommier and Topoisomerase, 2006; Champoux, 2001; Pommier et al., 2010). Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (Tdp1) is an enzyme that has been implicated in the repair of irreversible Top1cc and it counteracts the action of Top1 inhibitors to decrease their chemotherapeutic effect. Tdp1 has been regarded as a potential therapeutic co-target of Top1, and therefore, combination therapy of Top1-targeting drugs with Tdp1 inhibitors could lead to more effective cancer treatment (Huang et al., 2011; Conda-Sheridan et al., 2013; Sirivolu et al., 2012). Some of the known Tdp1 inhibitors are shown in Fig. 1. Transition metal oxoanions orthovanadate [VO4]3− and tung-state [WO4]2− were the first reported Tdp1 inhibitors, however, due to wide range of activity against phosphorylation reactions, they could not be used for pharmacological applications (Beretta et al., 2010). Furamidine (A), a bisbenzamide derivative, was identified as a TdP1 inhibitor through a high-throughput electrochemiluminescent assay. The furan linker of A was suggested to be important in Tdp1 inhibition by directly interacting with DNA or Tdp1 (Huang et al., 2011; Antony et al., 2007). Tetracyclins, including rolitetracycline (B), were also identified as Tdp1 inhibitors but lacked structural-activity relationship (Pommier et al., 2006). Fluoroquinolone derivatives C and D, both consisting of sulfonamide moiety showed potent Tdp1 inhibition activity. Interestingly, compounds containing sulfonamide moiety retained the activity, but not fluoroquinolone. This suggests that sulfonamide group could play an important role in modulator for Tdp1 inhibition (Pommier et al., 2012). Quantitative high throughput screen at NIH led to identification of compounds E and F. However, these compounds failed to show synergism in combination with camptothecin (Marchand et al., 2014). Indenoisoquinoline-derivatives have been developed as dual Top-1 – Tdp1 inhibitors. Compounds G and H were among the first in this class 98. Further structural modifications led to compound I, which is the most potent dual inhibitor in this series (Nguyen et al., 2015). In earlier study from our group, steroid-linked benzenesulfonate (J, Fig. 1) and its derivatives were reported as potential Tdp1 inhibitors (Dexheimer et al., 2009). Given that limited number of Tdp1 inhibitors have been reported to date and our ongoing interest in this field (Antony et al., 2007; Liao et al., 2006; Nguyen et al., 2012; Dean et al., 2014), we also tested our newly synthesized piperidinyl sulfonamides for their Tdp1 inhibitory activity.

Fig. 1.

Known Tdp1 inhibitors.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

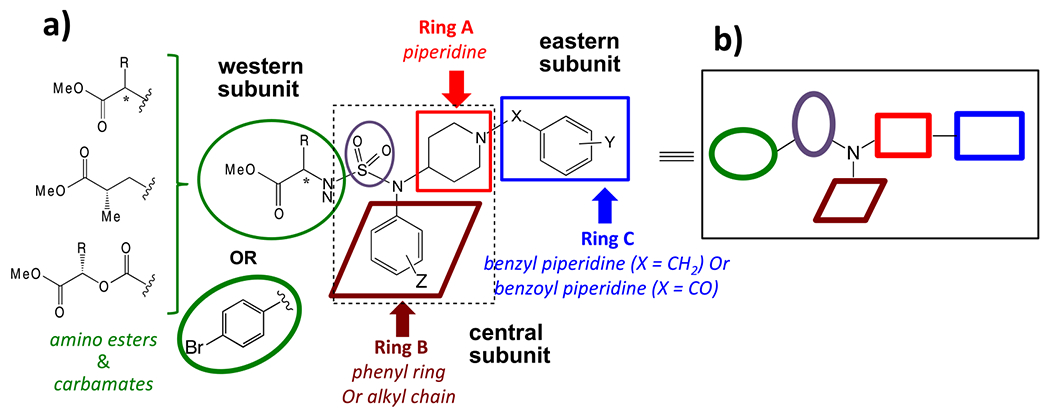

The new scaffold design proposed for our current studies is composed of three fragments: a) western subunit containing hydrophilic amino ester, carbamates or phenyl ring, b) central subunit consist of a sulfamide or sulfonamide group linked to piperidine (ring A) and phenyl (ring B); c) eastern subunit comprising benzyl or benzoyl ring (ring C) linked to piperidine (Fig. 2A). Structural modifications were focused around these three fragments to synthesize new piperidinyl sulfonamides. In general, the structure of these proposed compounds could be visualized as a network of five building blocks, as described in Fig. 3B. The desired scaffold can be synthesized by combining these five building blocks in different orders as described in subsequent section.

Fig. 2.

Scaffold design for novel piperidinyl sulfamides.

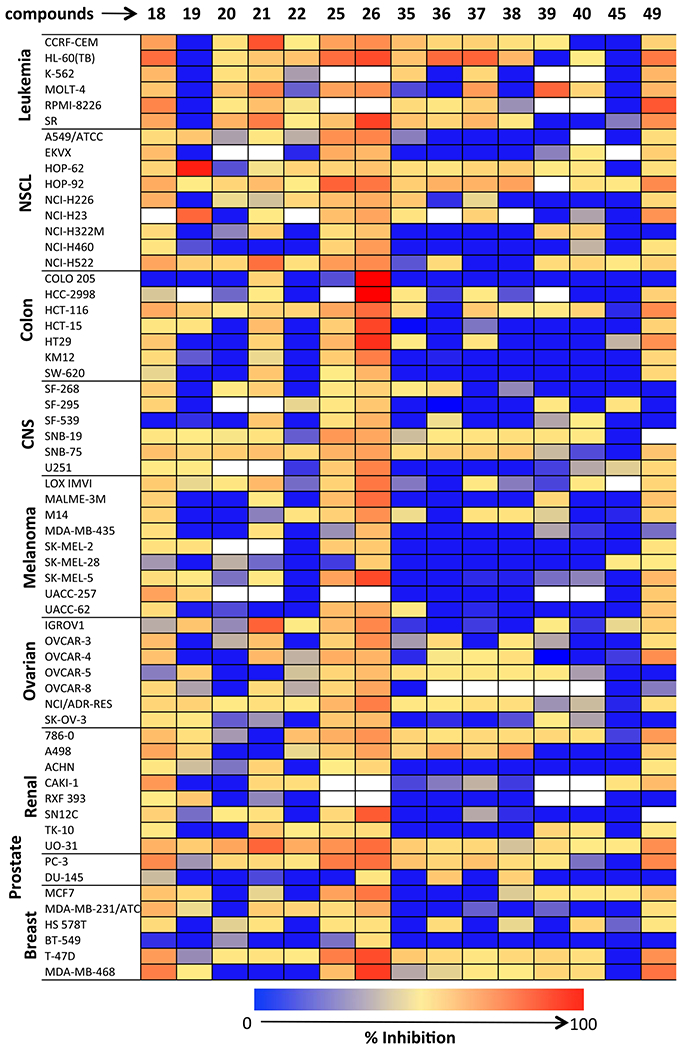

Fig. 3.

Heatmap diagram of NCI-60 cells Inhibition by piperidyl sulfamides at 10 μM (white boxes indicated no experiment was done on these cell lines).

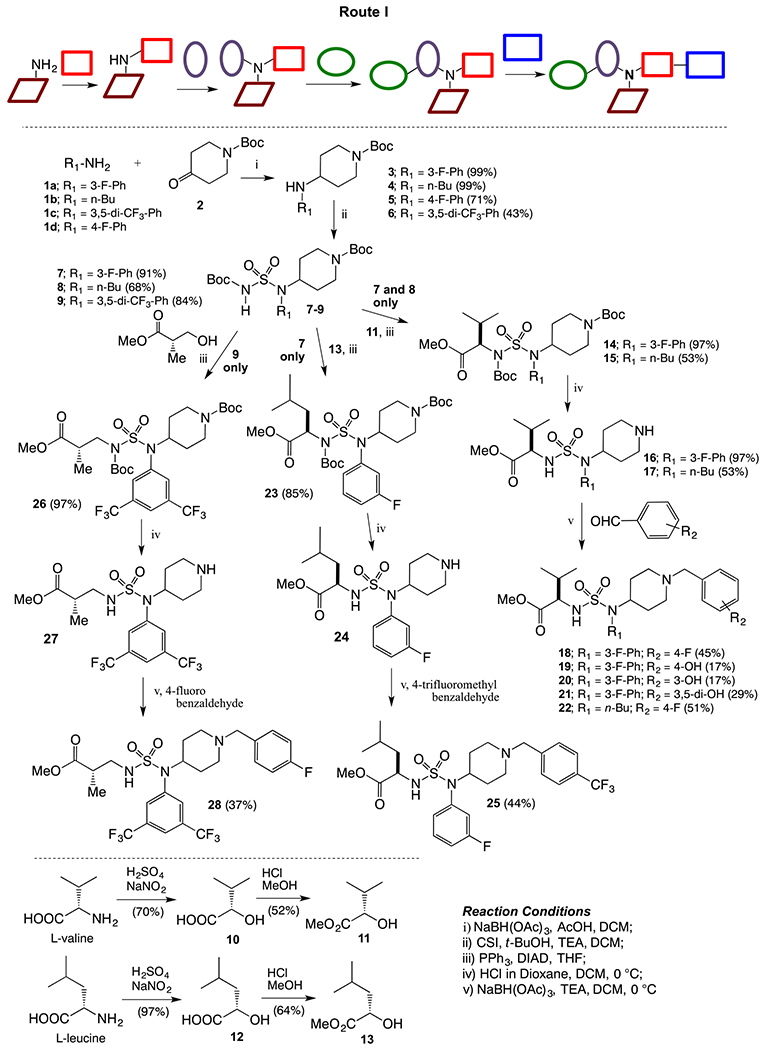

The first route (Route I) explored for the synthesis of desired sulfamide derivatives is outlines in Scheme 1. Reductive amination of different amines 1a–d and N-boc-4-piperidinone (2) was carried out to get secondary amines 3–6, which were coupled with chlorosulfonyl isocyanate (CSI) and t-butanol in the presence of triethylamine to the corresponding boc- protected sulfamides 7–9. α-Hydroxyesters 11 and 13 was obtained from esterification of acid 10 and 12, which were derived from amino acids l-valine and l-leucine, correspondingly, using the Van Slyke (Moumne et al., 2006) reaction maintaining the chiral integrity of amino acids. Mitsunobu reaction was carried out between α-hydroxyester 11 and sulfamides 7 and 8 to generate amino ester-linked sulfamides 14 and 15. Deprotection of the boc-group generated HCl salt of 16 and 17, which on reductive amination with different benzaldehydes afforded desired sulfamide aminoesters 18–22. Following similar protocols, Mitsunobu reaction of α-hydroxyester 13 with secondary amine 7 yielded corresponding intermediate 23, which after boc-deprotection and reductive amination with 4-trifluoromethyl benzaldehyde gave the desired sulfamide aminoester 25. To diversify the western subunit i.e. amino ester moiety of the compound, methyl (S)-(+)-3-hydroxy-2-methyl propionate was used for the Mitsunobu reaction with secondary aminie 9 to afford the corresponding boc-protected sulfamide intermediate 26. Deprotection of 26 followed by reductive amination with 4-fluorobenzaldehyde afforded the sulfamdie aminoester 28.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of piperidinyl sulfamides using Route I.

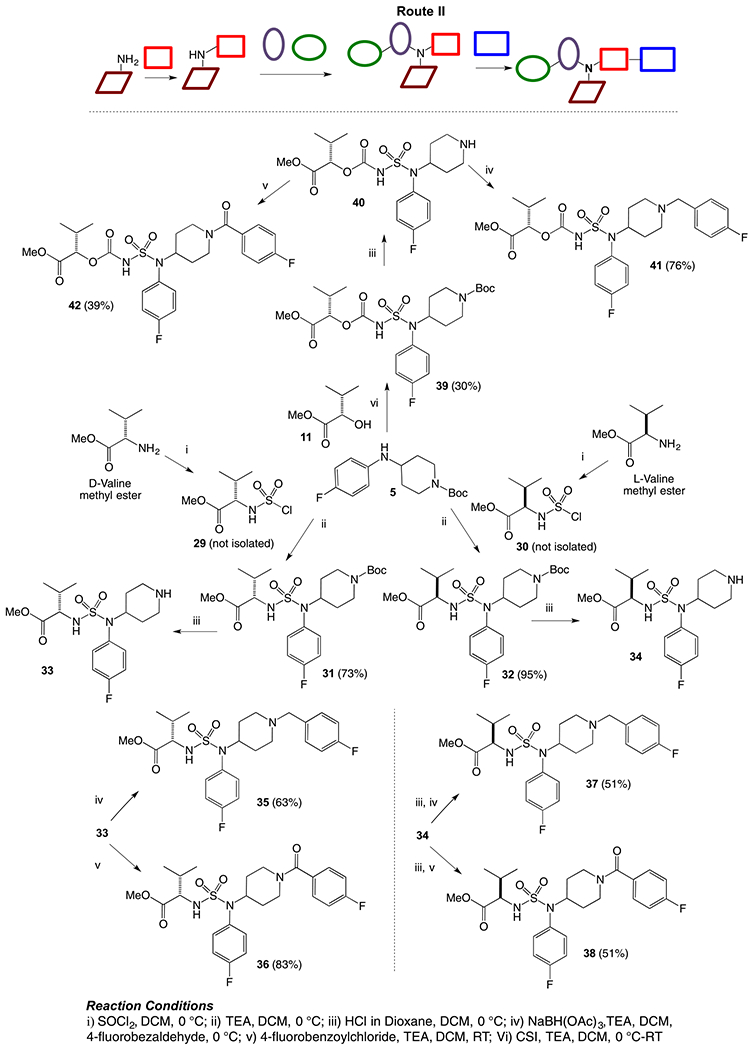

An alternative route to obtain piperidinyl sulfamide aminoester was explored (Route II, Scheme 2), where western subunit was introduced via corresponding sulfamoyl chlorides (generated in situ). d- or l-valine methyl ester hydrochlorides were couples with sulfuryl chloride to generate corresponding sulfamoyl chlorides 29 and 30 in situ at a low temperature, and were reacted with 4-fluorophenyl piperidinyl amine (5) to furnish sulfamides 31 and 32. Deprotection of boc-group was carried out under acidic conditions to get the HCl salts of 31 and 32. Reductive amination of 33 and 34 with p-fluorobenzaldehyde afforded sulfamides 35 and 37, respectively. Acylation of 33 and 34 was also carried out with p-fluorobenzoyl chloride to generate corresponding sulfamide aminoesters 36, and 38. Synthesis of sulfamide carbamates 34 and 35 was also carried out following similar reaction sequences. A solution of CSI and α-hydroxyl ester 11 (generated from l-valine via diazotization and esterification as shown in Scheme 1) was cannulated to a solution of secondary amine 5 in dichloromethane at 0 °C to obtain compound 33 in moderate yield. Finally, sulfamide carbamates 41 and 42 were obtained by boc-deprotection followed by reductive amination with 4-fluorobenzaldehyde and 4-fluorobenzoyl chloride, respectively.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of piperidinyl sulfamides using Route II.

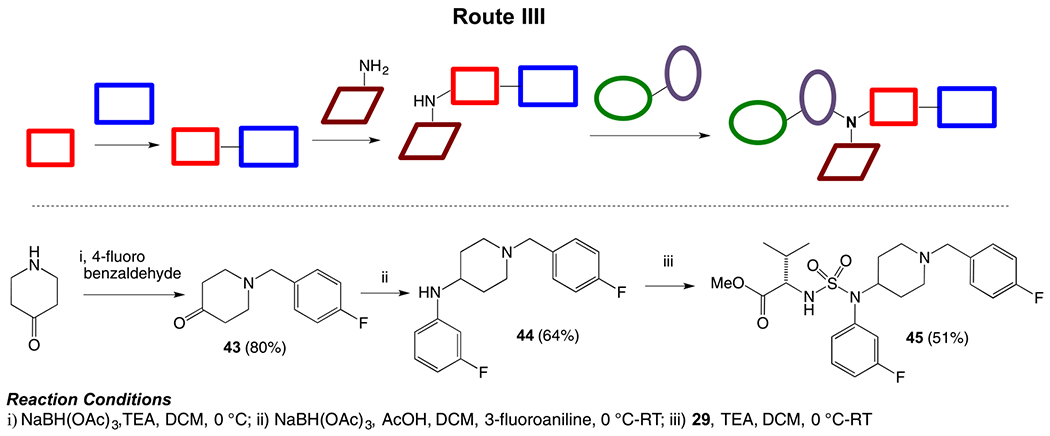

To determine the efficiency of different combinations of building blocks and obtain our desired scaffold, we explored another route by first combining ring A (piperidine) and ring C, followed by ring B and finally installing the western aminoester subunit (Route III, Scheme 3). Piperidone was reacted with 4-fluorobenzaldehyde under reductive amination condition to afford compound 43, which was again subjected to reductive amination with m-fluoroaniline to generate amine 44. Finally, compound 44 was coupled with sulfamoyl chloride 29 (generated in situ as described earlier) under basic condition to complete the synthesis of sulfamide aminoester 45.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of piperidinyl sulfamides using Route III.

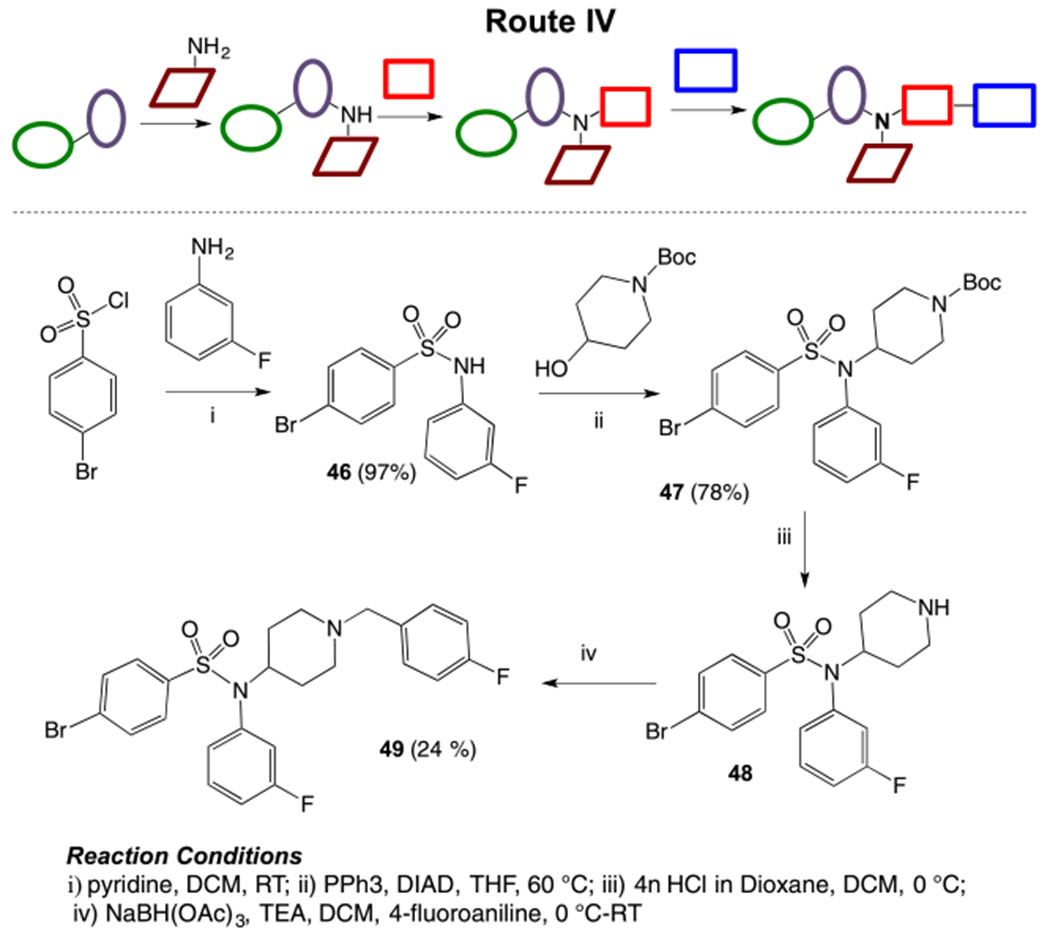

Another route was explored where arylsulfonyl chloride can serve as western subunit and can combine with ring B (aniline) followed by addition of ring A (piperidine) and then ring C. (Route IV, Scheme 4). Synthesis was started from the reaction of p-bromobenzenesulfonyl chloride with m-fluoroaniline under basic conditions to generate sulfonamide intermediate 46. Mistunobu reaction of 46 with boc-protected 4-hydroxypiperidine afforded compound 47 , which on boc-de-protection followed by reductive amination with 4-fluorobenzaldehyde gave the desired sulfonamide derivative 49.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of piperidinyl sulfamides using Route IV.

2.2. NCI 60 cell line screening

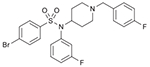

All the fifteen piperidinyl sulfamide derivatives synthesized in this study are listed in Table 1. The anticancer activities of these compounds were evaluated on NCI-60 panel, which comprised of 60 different human tumor cell lines representing various histology viz. leukemia, melanoma, and cancers of lung, colon, kidney, ovary, breast, prostate, and central nervous system. In a preliminary screen, all the piperidyl sulfamides were tested at 10 μM concentration to probe their inhibitory effect on these cell lines. The output from the single dose screen was reported as a mean of the percentage growth of the treated cells when compared with untreated control cells graph (given in the Supplementary data with general interpretation). Heatmap representation of inhibition caused by single dose (10 μM) treatment of piperidyl sulfamides with NCI-60 cells is given in Fig. 3. Preliminary screening showed that compounds 20, 22, 35, 39, 40 and 45 failed to show significant inhibition in any of the 60 cell lines. Compounds 18, 19, 21, 25, 36, 37, 39 and 49 showed moderate to significant activity, showing > 50% inhibition against one or more cell lines (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Interestingly, compounds 18, 36, 37 and 39 inhibited only one cell line viz. leukemia cell line HL-60-TB (entries 1, 5, 6 and 7, Table 2). Compound 19 very selectively and significantly inhibited NSCL cancer cell lines HOP-62 and NCI-H23 (entry 2, Table 2). Compounds 21, 25 and 49 showed good inhibitory activity against several cell lines (entry 3, 4 and 8, Table 2). Preliminary screening showed that sulfamide 26 was the most active compound in this series (data not shown in Table 2). It showed moderate inhibitory activity against most of the cell lines in the panel but it was highly selective for colon cancer cell lines (Fig. 3). Due to its high potency and selectivity, sulfamide 26 was selected to evaluate its dose-response using five different concentrations (0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 μM) against complete panel of NCI-60 cell lines. These studies provided three significant data points: i) GI50 value (growth inhibitory activity) corresponds to the concentration of the compound causing 50% decrease in net cell growth. ii) TGI value (cytostatic activity, the inhibition of cell growth and multiplication) is the concentration of the compound resulting in total growth inhibition. iii) LC50 value, signifies cytotoxic activity (lethal concentration), and is the concentration of the compound causing a net 50% loss of initial cells at the end of the incubation period. The results of dose response studies and their heatmap representation are given in Fig. 4. As seen in the one-dose screen, compound 26 was highly selective and potent against all the colon cancer cell lines (least for COLO-205 cell line, GI50 = 1.88 μM and maximum for SW-620 cell line, GI50 = 11.1 μM). The compound also showed partial selectivity toward leukemia (least for SR cell line, GI50 = 3.18 μM and maximum for CCRF-CEM cell line, GI50 = 12.8 μM) and the breast cancer subpanel (least for MDA-MB-468 cell line, GI50 = 3.25 μM and maximum for MDA-MB-231/ATCC cell line, GI50 = 12.7 μM). It also exhibited sensitivity toward some of cell lines of the melanoma cancer cell panel such as LOX IMVI (GI50 = 8.10 μM), MALME-3 M (GI50 = 6.89 μM), M14 (GI50 = 3.75 μM), and SK-MEL-5 (GI50 = 3.19 μM). All remaining subpanel cell lines showed maximum sensitive toward compound 26 with not >21 μM of GI50 concentrations. Moreover, it showed total growth inhibition of most of the cell lines at moderate concentrations, as indicated by TGI values. Importantly, compound 26 was not cytotoxic for most of the cell lines as indicated by higher LC50 values (Fig. 4), suggesting that it could provide a good therapeutic index for its further applications as chemotherapeutic agent.

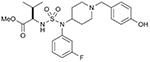

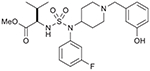

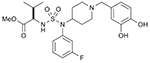

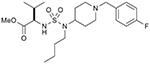

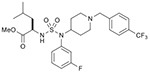

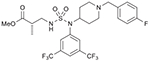

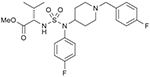

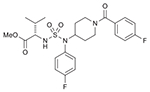

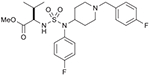

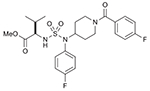

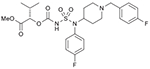

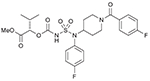

Table 1.

List of compounds synthesized in this study (NSC# are designated by NCI for their record keeping).

| Compd. (NSC #) | Structure | NSC no. | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

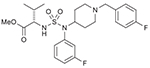

| 18 (750706) |  |

19 (747166) |  |

| 20 (767523) |  |

21 (767524) |  |

| 22 (750707) |  |

25 (749205) |  |

| 26 (749204) |  |

35 (750715) |  |

| 36 (750714) |  |

37 (750713) |  |

| 38 (750712) |  |

39 (749203) |  |

| 40 (749202) |  |

45 (764209) |  |

| 49 (750772) |  |

Table 2.

Cell lines sensitive (> 50% inhibition) to active piperidyl sulfamides at 10 μM conc.

| Entry | Compd. (NSC#) | Inhibition of sensitive tumor cell lines at 10 μM conc. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 (750706) | Leukemia: HL-60-TB (56%) |

| 2 | 19 (747166) | NSCL: HOP-62 (88%); NCI-H23 (58%) |

| 3 | 21 (767524) | Leukemia: CCRF-CEM (67%); NSCL: NCI-H22 (55%); Ovarian: IGROV-1 (60%); Renal: UO-31 (59%) |

| 4 | 25 (749205) | Leukemia: MOLT-4 (56%); NSCL: HOP-92 (60%); Prostate: PC-3 (50%) |

| 5 | 36 (740714) | Leukemia: HL-60-TB (57%) |

| 6 | 37 (750713) | Leukemia: HL-60-TB (60%) |

| 7 | 39 (749203) | Leukemia: MOLT-4 (59%) |

| 8 | 49 (750772) | Leukemia: CCRF-CEM (51%); RPMI-8226 (65%); Breast: MDA-MB-468 (53%) |

Bold and italics represents the types of cell lines used in the cytotoxicity experiments.

Fig. 4.

(A) GI50, TGI and LC50 (μM) of 26 (NSC 749204) on NCI-60 cell lines. (B) Heatmap representation of GI50, TGI and LC50 values of 26.

2.3. Tdp1 inhibition studies

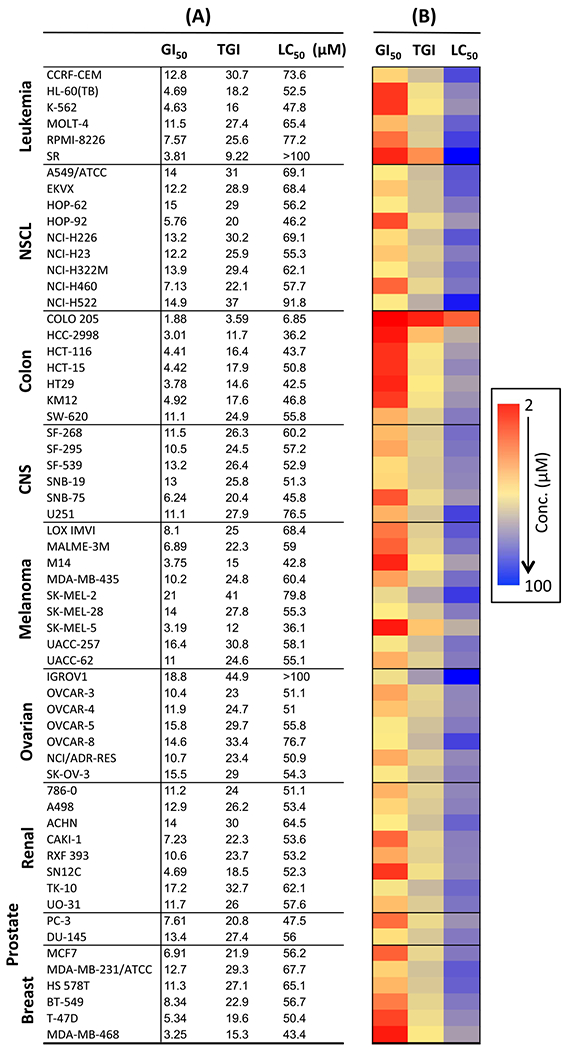

All fifteen piperidinyl sulfamides were screened for Tdp1 inhibition activity. The biochemical assay used for these studies involved single-stranded 14Y (14-mer strand) as substrates and 32P-Radiolabeling (*) at the 5′ terminus of the strand (Fig. 5A). Tdp1 catalyzes the hydrolysis of the 3′-phosphotyrosine bond using water molecule and converts 14Y to an oligonucleotide with 3′-phosphate 14P. 5′-32P-labeled DNA substrate was incubated with recombinant Tdp1 in the absence or presence of sulfonamides at five different concentrations i.e. 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10, and 100 μM. Gel scans of these studies are shown in Fig. 5B. 3′-Phosphate oligonucleotide product (14P) was developed faster than the corresponding tyrosyl oligonucleotide substrate (14Y). Results showed that sulfonamide aminoester 18 inhibits Tdp1 activity significantly with IC50 23.7 μM. Interestingly, compound 45 (S-configuration), which is a stereoisomer of 18 (R-configuration) was completely inactive. This indicates that chirality of the compound contributes to the affinity of inhibitor for the active site of the Tdp1 enzyme.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of Tdp1 activity by piperidinyl sulfamides.

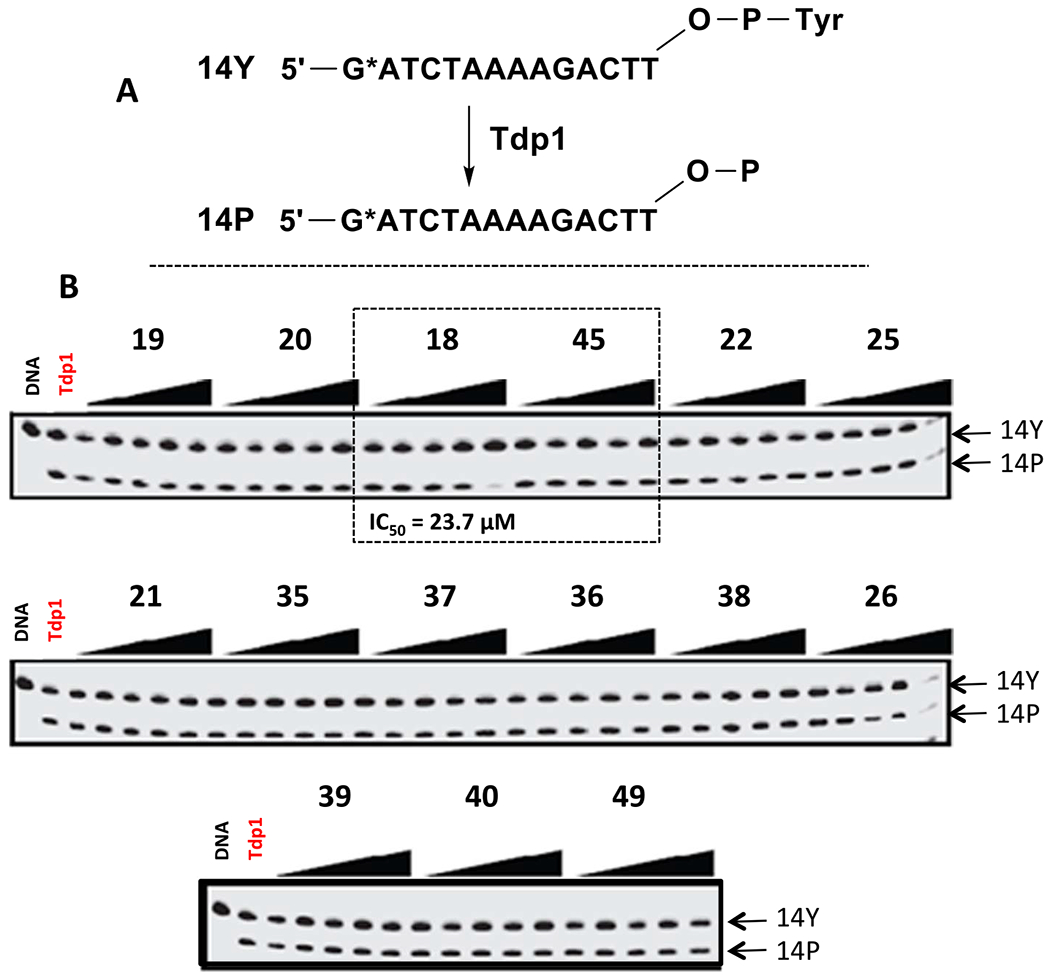

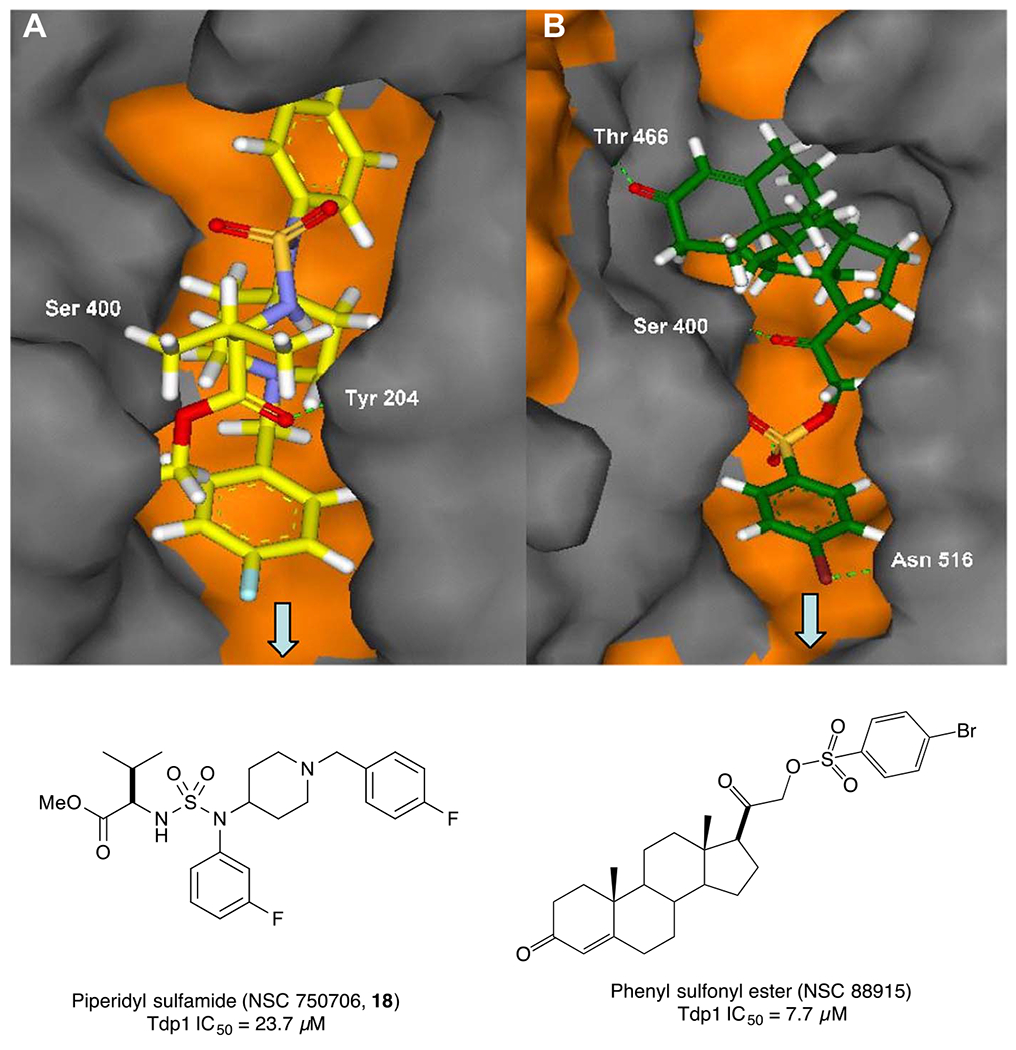

2.4. Protein docking study

To investigate the binding mode of the piperidinyl sulfamide derivative 18 to Tdp1 at the molecular level, we performed docking analysis using the high-resolution structure of Tdp1, co-crystallized with a peptide-vanadate-DNA substrate mimic (PDB accession code 1NOP) (Fig. 6). An active Tdp1 inhibitor NSC 88915 was also used for comparison. The arrow indicates the direction to the Tdp1 active site. Hydrophobic and hydrophilic surface areas of the protein are colored in grey and orange, respectively. The coloring of atoms is as follows: carbon – yellow (A), green (B); nitrogen – blue; oxygen – red; sulfur - orange. Ligands are displayed in stick representations, while all hydrogen atoms have been shown. Hydrogen bonds are represented by green dotted lines. Results suggest that both inhibitors bind in the same binding pocket and form hydrogen bond with Serine 400. In case of synthesized compound 18, the benzyl piperidine moiety is oriented toward Tdp1 active site and the hydrophobic amino ester moiety forms a hydrogen bond with Tyrosine 204.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the best docking poses of active compound 18 (A) and reported earlier phenyl sulfonyl ester derivative (NSC 88915, B) (Weidlich et al., 2010) docked into the active site of Tdp1 (H263, K265, H493, and K495).

3. Conclusion

In summary, we proposed a novel scaffold consist of piperidyl-sulfamide-based core structure. We successfully explored different methods to synthesize these compounds. To probe their anticancer chemotherapeutic effects, a phenotypic screening was conducted on NCI-60 human cancer cell lines. Primary screening done at single dose of 10 μM showed that some of these compounds were moderate to highly sensitive against multiple cell lines. Dose-response studies of the ‘hit’ sulfamide 26 showed it to be highly potent against multiple cell lines with GI50 ranging from 1.88 μM to 21 μM. Compound 26 was highly selective against colon cancer cell lines and partially selective for leukemia, melanoma and breast cancer cell lines. Its higher LC50 values also indicated that compound 26 was not cytotoxic for most of the cell lines, which makes it a potential candidate for further developments as chemotherapeutic agent. Tdp1 inhibition studies carried out on these sulfamides showed compound 18 to be a potential Tdp1 inhibitor with IC50 = 23.7 μM. Further efforts to make more analogues of similar scaffold for SAR evaluation and their development for therapeutic applications are underway in our laboratory.

4. Experimental

4.1. General methods

All air and moisture sensitive reactions were carried out in flame- or oven dried glassware under argon or nitrogen. Methylene chloride (CH2Cl2), tetrahydrofuran (THF), diethyl ether (Et2O), and toluene were purified by passage through a Solv-Tek solvent purification system employing activated Al2O3, or used them immediately after purchasing from Sigma-Aldrich as anhydrous solvent grade. All the reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without any purification. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on precoated Merck silica gel 60F254 plates and observed under UV light (254 nm) and KMnO4 stain. Flash column chromatography was performed with Teledyne ISCO Rf flash chromatography system using various sizes of Teledyne columns or Grace® Flash Cartridges. The 1H (400 MHz) and 13C (101 MHz) NMR spectra were taken on a Varian 400-MR spectrophotometer using TMS as internal standard. Chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in ppm. Coupling constants (J) are expressed in Hz and splitting patterns are described as follows: s = singlet; d = doublet; t = triplet; q = quartet; m = multiplet; dd = doublet of doublets; dt = doublet of triplets; td = triplet of doublets; ddd = doublet of doublet of doublets. HRMS was taken on Agilent 1200 series system with an Agilent 6210 time-of-flight (TOF) mass detector. Synthetic procedures of all the compounds presented in this article are explained in the supplementary information.

4.2. NCI-60 screening protocol

Details of the methodology for NCI 60 cell line screening are described at https://dtp.cancer.gov/discovery_development/nci-60/methodology.htm (Boyd and Pauli, 1995; Alley et al., 1988; Shoemaker, 2006). Briefly, the panel is organized into nine sub panels representing diverse histologies: Leukemia, melanoma, and cancers of lung, colon, kidney, ovary, breast, prostate, and central nervous system. The cells are grown in supplemented RPM1 1640 medium for 24 h. The test compounds were dissolved in DMSO and incubated with cells at desired concentration (for one-dose study at 10 μM concentration and for dose-response studies at 0.01, 0.1, 1.0 10 and 100 μM concentrations). The assay is terminated by addition of cold trichloroacetic acid, and the cells are fixed and stained with sulforhodamine B. Bound stain is solubilized, and the absorbance is read on an automated plate reader.

4.3. Tdp1 inhibition studies

4.3.1. Expression and purification of Tdp1

Wild-type and mutant (H493R) human Tdp1 enzymes were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells and purified as described earlier (Antony et al., 2007). Human Tdp1 expressing plasmid pHN1910 (a gift from Dr. Howard Nash, Laboratory of Molecular Biology, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health) was constructed using vector pET-15b (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) with full-length human Tdp1 and an additional His-tag sequence of MGSSHHHHHHSSGLVPRGSHMLEDP in its N terminus. The His-tagged human Tdp1 was purified from Novagen BL21 cells using chelating sepharose™ fast flow column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) according to the company’s protocol. The collected fractions were assayed immediately for Tdp1 activity. Fractions that showed Tdp1 activity were pooled and dialyzed in 20% glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 2 mM EDTA. Dialyzed samples were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. Tdp1 concentration was determined using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Tdp1 purity was determined as a single ~70 kDa band representing over 95% of the detectable proteins stained by Coomassie after SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

4.3.2. Tdp1 biochemical assay

A 1 nM 5′-32P-labeled DNA substrate was incubated with 0.1 nM recombinant Tdp1 in the absence or presence of inhibitor for 20 min at 25 °C in a reaction buffer containing 50 μM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 80 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 40 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA). Reactions were terminated by the addition of two volumes of gel loading buffer (96% (v/v) formamide, 10 μM EDTA, 1% (w/v) xylene cyanol, and 1% (w/v) bromphenol blue). The samples were subsequently heated to 95 °C for 5 min and subjected to 18% sequencing gel electrophoresis. A concentration of 100 nM was used when employing the SCAN1 mutant H493R. In addition, H493R reactions were divided in half. One-half of the reaction was run on a sequencing gel, while the other half was analyzed by 4–20% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. Imaging and quantification were performed using the Typhoon 8600 and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics), respectively.

4.4. Molecular modeling

4.4.1. Preparation of ligand structures

The piperidinyl sulfamide derivatives were drawn in ChemBioDraw Ultra 12.0 program. Additional molecular construction and modeling of the derivatives were performed using the building tools available in MACROMODEL 2011 (Schrödinger Inc. New York, NY). The ligands were minimized using the OPLS-2005 force field. The preparation procedure in GLIDE requires the preparation of the structures in the appropriate ionization state. We used 2D to 3D conversion program LigPrep (Schrödinger Inc. New York, NY) to generate accurate energy minimized molecular structures, expands tautomeric and ionization states, ring conformations, and stereoisomers to produce broad chemical and structural diversity of ligand libraries for further computational analyses.

4.4.2. Molecular docking

Molecular docking analysis was performed using the high-resolution structure of Tdp1, co-crystallized with a peptide-vanadate-DNA substrate mimic (PDB accession code 1NOP). After construction of a molecular model from 1NOP (published earlier) (Weidlich et al., 2010) the prepared ligands were docked into the substrate-binding pocket of Tdp1 using the program GLIDE (Schrödinger Inc. New York, NY) in Extra Precision mode. A set of Grid files was generated with residues H263, K265, H493 and K495 at the center of the binding box defining the space through which the center of the docked ligand is allowed to move. The size of the cube box was set to 16 Å edge in length in order to explore a large region of the protein. To conduct a more precise analysis of docked poses of the ligands, we mapped the output docking poses to the pharmacophores of the lead compounds using absolute positioning in program MOE (Chemical Computing Group’s Molecular Operating Environment, version 2011).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to thank the Development Therapeutics Branch of the National Cancer institute (NCI) for evaluating the anticancer activity of our compounds on the NCI60 screen. This work was partially funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that the content of this article has no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Synthetic procedures and characterization of all the compounds made and their characterization data i.e. IR, 1H and 13C NMR and HRMS spectra are given in detail in the supplementary information. Protocols for NCI-60 screening, mean graphs of one-dose screening and dose response curves with their general interpretation, protocols for Tdp1 biochemical assay and molecular docking studies are also described in supplementary information. Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2017.10.017.

References

- Alley MC, Scudiero DA, Monks A, Hursey ML, Czerwinski MJ, Fine DL, Abbott BJ, Mayo JG, Shoemaker RH, Boyd MR, 1988. Feasibility of drug screening with panels of human-tumor cell-lines using a microculture tetrazolium assay. Cancer Res. 48 (3), 589–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony S, Marchand C, Stephen AG, Thibaut L, Agama KK, Fisher RJ, Pommier Y, 2007. Novel high-throughput electrochemiluminescent assay for identification of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase (Tdp1) inhibitors and characterization of furamidine (NSC 305831) as an inhibitor of Tdp1. Nucleic Acids Res. 35 (13), 4474–4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlier A, Jaquet P, 2006. Quinagolide - a valuable treatment option for hyperprolactinaemia. Eur. J. Endocrinol 154 (2), 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta GL, Cossa G, Gatti L, Zunino F, Perego P, 2010. Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 targeting for modulation of camptothecin-based treatment. Curr. Med. Chem 17 (15), 1500–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolli MH, Boss C, Binkert C, Buchmann S, Bur D, Hess P, Iglarz M, Meyer S, Rein J, Rey M, Treiber A, Clozel M, Fischli W, Weller T, 2012. The discovery of N-5-(4-Bromophenyl)-6-2-(5-bromo-2-pyrimidinyl)oxy ethoxy-4-pyrimidi nyl-N’-propylsulfamide (Macitentan), an orally active, potent dual endothelin receptor antagonist. J. Med. Chem 55 (17), 7849–7861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd MR, Pauli KD, 1995. Some practical considerations and applications of the National-Cancer-Institute in-vitro anticancer drug discovery screen. Drug Dev. Res 34 (2), 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chahine EB, Ferrill MJ, Poulakos MN, 2010. Doripenem: A new carbapenem antibiotic. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm 67 (23), 2015–2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champoux JJ, 2001. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem 70, 369–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conda-Sheridan M, Reddy PVN, Morrell A, Cobb BT, Marchand C, Agama K, Chergui A, Renaud A, Stephen AG, Bindu LK, Pommier Y, Cushman M, 2013. Synthesis and biological evaluation of Indenoisoquinolines that inhibit both Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I (Tdp1) and topoisomerase I (Top1). J. Med. Chem 56 (1), 182–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean RA, Fam HK, An JH, Choi KH, Shimizu Y, Jones SJM, Boerkoel CF, Interthal H, Pfeifer TA, 2014. Identification of a putative Tdp1 inhibitor (CD00509) by in vitro and cell-based assays. J. Biomol. Screen 19 (10), 1372–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexheimer TS, Gediya LK, Stephen AG, Weidlich I, Antony S, Marchand C, Interthal H, Nicklaus M, Fisher RJ, Njar VC, Pommier Y, 2009. 4-Pregnen-21-ol-3,20-dione-21-(4-bromobenzenesulfonate) (NSC 88915) and related novel steroid derivatives as tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase (Tdp1) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 52 (22), 7122–7131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SYN, Pommier Y, Marchand C, 2011. Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (Tdp1) inhibitors. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat 21 (9), 1285–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JD, Jewell JP, Guerin DJ, Lim J, Dinsmore CJ, Deshmukh SV, Pan BS, Marshall CG, Lu W, Altman MD, Dahlberg WK, Davis L, Falcone D, Gabarda AE, Hang GZ, Hatch H, Holmes R, Kunii K, Lumb KJ, Lutterbach B, Mathvink R, Nazef N, Patel SB, Qu XL, Reilly JF, Rickert KW, Rosenstein C, Soisson SM, Spencer KB, Szewczak AA, Walker D, Wang WX, Young J, Zeng QW, 2011. Discovery of a 5H-benzo 4,5 cyclohepta 1,2-b pyridin-5-one (MK-2461) inhibitor of c-met kinase for the treatment of cancer. J. Med. Chem 54 (12), 4092–4108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao ZY, Thibaut L, Jobson A, Pommier Y, 2006. Inhibition of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase by aminoglycoside antibiotics and ribosome inhibitors. Mol. Pharmacol 70 (1), 366–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand C, Huang SYN, Dexheimer TS, Lea WA, Mott BT, Chergui A, Naumova A, Stephen AG, Rosenthal AS, Rai G, Murai J, Gao R, Maloney DJ, Jadhav A, Jorgensen WL, Simeonov A, Pommier Y, 2014. Biochemical assays for the discovery of TDP1 inhibitors. Mol. Cancer Ther 13 (8), 2116–2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moumne R, Lavielle S, Karoyan P, 2006. Efficient synthesis of beta(2)-amino acid by homologation of alpha-amino acids involving the Reformatsky reaction and Mannich-type imminium electrophile. J. Org. Chem 71 (8), 3332–3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TX, Morrell A, Conda-Sheridan M, Marchand C, Agama K, Bermingam A, Stephen AG, Chergui A, Naumova A, Fisher R, O’Keefe BR, Pommier Y, Cushman M, 2012. Synthesis and biological evaluation of the first dual tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I (Tdp1)-topoisomerase I (Top1) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 55 (9), 4457–4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TX, Abdelmalak M, Marchand C, Agama K, Pommier Y, Cushman M, 2015. Synthesis and biological evaluation of nitrated 7-, 8-, 9-, and 10-hydro-xyindenoisoquinolines as potential dual topoisomerase I (Top1)-tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I (TDP1) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 58 (7), 3188–3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan BS, Chan GKY, Chenard M, Chi A, Davis LJ, Deshmukh SV, Gibbs JB, Gil S, Hang GZ, Hatch H, Jewell JP, Kariv I, Katz JD, Kunii K, Lu W, Lutterbach BA, Paweletz CP, Qu XL, Reilly JF, Szewczak AA, Zeng QW, Kohl NE, Dinsmore CJ, 2010. MK-2461, a novel multitargeted kinase inhibitor, preferentially inhibits the activated c-met receptor. Cancer Res. 70 (4), 1524–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish CA, Adams ND, Auger KR, Burgess JL, Carson JD, Chaudhari AM, Copeland RA, Diamond MA, Donatelli CA, Duffy KJ, Faucette LF, Finer JT, Huffman WF, Hugger ED, Jackson JR, Knight SD, Luo L, Moore ML, Newlander KA, Ridgers LH, Sakowicz R, Shaw AN, Sung CMM, Sutton D, Wood KW, Zhang SY, Zimmerman MN, Dhanak D, 2007. Novel ATP-competitive kinesin spindle protein inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 50 (20), 4939–4952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommier Y, Topoisomerase I, 2006. Inhibitors: camptothecins and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6 (10), 789–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommier Y, Marchand C, Thibaut L, 2006. Tetracyclines and Derivatives as Inhibitors of Human Tyrosyl-DNAphosphodiesterase (Tdp1). US60786746.

- Pommier Y, Leo E, Zhang HL, Marchand C, Topoisomerases DNA, 2010. Their poisoning by anticancer and antibacterial drugs. Chem. Biol 17 (5), 421–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommier Y, Marchand C, Selvam P, Dexheimer T, Maddali K, 2012. Fluoroquinolone Derivatives or Sulfonamide Moiety-containing Compounds as Inhibitors of Tyrosyl-Dnaphosphodiesterase (tdp1). US 2012/0172371A1.

- Reitz AB, Smith GR, Parker MH, 2009. The role of sulfamide derivatives in medicinal chemistry: a patent review (2006–2008). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat 19 (10), 1449–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scozzafava A, Mastrolorenzo A, Supuran CT, 2006. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and activators and their use in therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat 16 (12), 1627–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker RH, 2006. The NCI60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6 (10), 813–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirivolu VR, Vernekar SKV, Marchand C, Naumova A, Chergui A, Renaud A, Stephen AG, Chen F, Sham YY, Pommier Y, Wang ZQ, 2012. 5-Arylidenethioxothiazolidinones as inhibitors of tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I. J. Med. Chem 55 (20), 8671–8684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temperini C, Winum JY, Montero JL, Scozzafava A, Supuran CT, 2007. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: the X-ray crystal structure of the adduct of N-hydroxysulfamide with isozyme II explains why this new zinc binding function is effective in the design of potent inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 17 (10), 2795–2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiry A, Dogne JM, Supuran CT, Masereel B, 2008. Anticonvulsant sulfonamides/sulfamates/sulfamides with carbonic anhydrase inhibitory activity: drug design and mechanism of action. Curr. Pharm. Des 14 (7), 661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JC, 1996. DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem 65, 635–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidlich IE, Dexheimer T, Marchand C, Antony S, Pommier Y, Nicklaus MC, 2010. Inhibitors of human tyrosyl-DNA phospodiesterase (hTdp1) developed by virtual screening using ligand-based pharmacophores (vol 18, pg 182, 2010). Bioorg. Med. Chem 18 (6), 2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winum JY, Scozzafava A, Montero JL, Supuran CT, 2006a. Therapeutic potential of sulfamides as enzyme inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev 26 (6), 767–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winum JY, Scozzafava A, Montero JL, Supuran CT, 2006b. The sulfamide motif in the design of enzyme inhibitors. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat 16 (1), 27–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.